RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated by Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated by Microsoft Bing

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

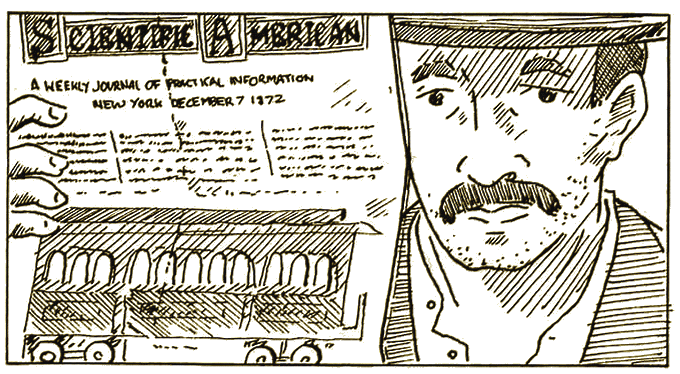

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

I WILL premise by saying that my narrative deals with the correlation of forces and the production of ghosts.

My narrative will have the effect of removing all doubt about the reality of that class of spectral manifestations which has ever been a subject for jest to professors of positive science, who, where they admit their existence at all, refer them to a diseased or abnormal condition of the brain. This question, however, will now happily be set at rest, as the distinguished scientists referred to will have an opportunity of producing these spectral manifestations almost at will, and have the pleasure of knowing that the spectres they produce are the result of an invariable and ordinary natural law and merely constitute another example of the universality and harmony of the great law of cause and effect which pervades nature, acting alike upon the atom and the nebula. Many ghost stories, which now appear to be the maunderings of superstitious or half-witted idiots, will henceforth be known to have originated not in a series of diseased imaginations, but in the workings of an obscure but unerring natural law. It must not be supposed, however, that the class of spectral manifestations which can thus be produced are of the same nature, or have the same origin, as the phantasmagoria of the mediaeval necromancer or modern charlatan. The spectres which these invoke are independent of time and place, while those to which I allude are purely local in their character and depend for their very being upon surrounding conditions.

What old residence in any of the old countries of Europe, England, Scotland, Ireland, or Germany, or even in the older States of America itself, does not boast of some particular ghostly legend connected with its grey old walls, antiquated galleries, and dilapidated chambers? Not to possess some family spectre associated with such a residence, would be evidence against its claim to the honours of antiquity or romance. What would the old castles of Germany be without the spectres of their mail-clad barons, their clanking chains, and their pale ladies in white? What the old halls or abbeys of the British Isles without the nocturnal visitations of the ghostly Sir Marmaduke or the gliding figure of the stately Lady Clare? Have not the spectral apparitions of these renowned personages been attested to and vouched for from time immemorial by grey-bearded seneschals and grave waiting-men and women, whose very gravity and sincerity proclaim them as innocent as they would be incapable of deception on so serious a subject?

To what then are we to attribute the faith and veneration with which these visions and legends are received on the one side, and the scepticism and ridicule with which they are met upon the other? Is it possible that traditions so exact in their character regarding the appearance of particular spectres in particular places should be absolutely baseless, and if not absolutely baseless, whence came the substratum of truth which developed into the substantial entity in which most of them are found? These and similar speculations must frequently have arisen in thinking minds when discussing this curious psychical problem, and it is with the object of affording some assistance toward its rational solution that I now, for the first time, make public the following experience.

LAST summer, while visiting the Paris Exposition, I chanced to

meet, in that portion of the building devoted to the science and

applied mechanics of electricity, a gentleman with whom I had

become acquainted in the city of San Francisco a few months

before. He had been then introduced to me as a man of science and

an inventor of some note, though his inventions, I had been told,

were of a tentatory and theoretical rather than of a practical

nature; in other words, though his ideas were valuable and often

grand in their character, to the ordinary mind he would have

seemed to be aiming at too much, and, while endeavouring to grasp

the unattainable, he would miss the practical results which he

might, with less imagination, have secured. For instance, in the

domain of electrical science, to which he had lately been

applying himself, he had sketched out the theory of several novel

applications of that wonderful medium. One was telegraphy without

wires, by means of an electric diaphragm or envelope, which he

conceived encircled the globe at a certain height, and being

tapped at any locality by a small captive balloon, up whose

anchoring cord ran a conducting wire terminating in a recording

instrument, would furnish a suitable medium of communication with

any other instrument similarly connected with the diaphragm and

keyed to the same electric pitch. Another was the transmutation

of metals by means of the transmission of a powerful electric

current through their masses, thus changing their densities and

consequently their volumes and their colours, by merely altering

the collocation of their atoms through this mysterious and

all-potent agency.

These instances will serve to give some idea of the brilliant though visionary character of my friend, and it was accordingly without the least surprise that I found him ensconced in the electrical department of the exposition, still less that he had had only the modest space of some six feet square allotted to him, while his more practical, though not more ingenious, collaborators in the same sphere of discovery had ten or more times the area.

It was while I was sauntering leisurely down one of the aisles that my eye fell upon the familiar figure of Mr. Espy, of whose presence in Paris I had not previously been aware. He was seated at a little table, upon which were set some instruments, or models, connected with his art, and upon one of which his attention seemed to be particularly concentrated. This was a highly polished globe, or sphere, either of metal or silvered glass, I could not tell which, about six inches in diameter and raised upon a slender pedestal to about the same height above the table.

Presently Mr. Espy awoke from the fit of abstraction with which he had been regarding this sphere, and turned his eyes critically upon a curious piece of mechanism which stood on the table beside it. This bore no resemblance to anything I had ever seen before, and I can only describe what it looked like by a simile. Imagine for yourself two hollow hemispheres, hinged together at a point upon their peripheries, and set flat upon the table so that they stood side by side. From the surfaces of these hemispheres radiated, in every direction, from a point which would have been their common centre had they been shut close together so as to form a perfect globe, a series of slender rods like the bristles on a porcupine, each terminating in a little bulb at a distance of some ten or twelve inches from the surface of the globe.

Preoccupied as he was Mr. Espy took no notice of my presence, but seemed to be revolving some problem in his mind, with one hand on the curious appliance I have just described, his long black hair hanging down so as almost to conceal his sallow face. After a moment or two, he raised the bristling hemispheres from the table till they were over the polished globe, round which he clasped them together like a cover, the outer hollow sphere, as I could see, fitting very closely to the inner one. This was evident for the reason that the outer sphere, or envelope, was, I could now see, composed of some extremely diaphanous substance, so transparent as only to intercept with a gauze-like film the reflection from the spherical mirror within. Neither did the slender rods that radiated from the centre materially affect the field of vision, as they were only about one-sixteenth of an inch in thickness, and closely serried as they seemed when viewed laterally, they formed scarcely any visual obstruction when pointing directly toward the eye.

When Mr. Espy had effected this arrangement, he looked up.

"Glad to see you," he said, rising and shaking me by the hand; "I did not know you were in Paris."

I told him that I was equally unconscious of his own presence, and made a remark regarding the queer instrument upon the table.

"Yes," he said, "that is the practical embodiment of an idea I have lately evolved, and though it is, in some respects, crude as yet, I see great possibilities in it for the future. My friend Edison over there," with a gesture in the direction of that distinguished inventor's department, "or if not Edison, Bell, or whoever else may lay claim to the original discovery, ascertained that sound vibrations could be conveyed along a wire by an electrical current and reproduced at the other end in precisely the same manner—pitch, tone, and expression—as they had been originally delivered. Edison has since gone a step further, and by a very simple mechanical means has caused these sound vibrations to transcribe their own equivalents upon a wax cylinder, which, by an inverse process, can be made to give forth the same identical vibrations when required. The phonograph is simply an adaptation of the principle of the telephone, storing up for future reference, just as in a book, the sounds—be they words, harmonies, or discords, simple or composite—which have been committed to its keeping."

"I understand the principle perfectly," I assented, as Mr. Espy mused for an instant in abstraction.

"Now," he continued, "this little instrument here is also a receiver and transmitter of vibrations, not on the principle of the phonograph, for it has no means of storing what it receives, but reproduces the vibrations instantly after the manner of the telephone. It is, in one respect, less serviceable than the telephone, as it is not susceptible to ordinary sound-vibrations in the accepted sense of the term; in another respect, it is infinitely more delicate and more potent. What would you say," he went on, earnestly, and looking me keenly in the eye, "if I were to tell you that that little, simple, and insignificant instrument is capable of recording and reproducing luminous pulsations, or light-vibrations, call them what you will, so delicate in their nature that it would fill you and the scientific world at large with incredulity and amazement were I at present to even hint at or suggest what they are competent to reveal?"

I replied that scarcely any new discovery in the mysterious domain of electric science would surprise me, after the results we had witnessed during the past few years.

"I do not know," went on Mr. Espy, "whether I can make myself intelligible, without ocular demonstration, on the scope of my discovery. Briefly and simply stated, this little instrument, which I have christened the eidoloscope, is capable of becoming susceptible to the action of the luminous waves emanating from objects exposed to the impact of similar waves at some period of the past."

"I confess I do not quite catch your meaning," I remarked, somewhat mystified by the generality of the description.

"I perfectly appreciate your position," returned Mr. Espy, smiling; "the results I obtained were astounding and inexplicable to myself the first time I realised their true purport, and it was only after much hard and careful thought that I succeeded at last in reducing them to the very simple and beautiful law under which they are produced. Let us see whether I can not explain the matter by a specific illustration. You see this polished globular mirror here. It is made of glass, backed with quicksilver, and does not differ in any respect from hundreds of others of the same fashion, save, perhaps, in a more accurate sphericity. The hollow diaphanous envelope which surrounds it is made of an elastic preparation, into the composition of which I will say that celluloid largely enters. This is blown into spherical shape, on the principle of an ordinary soap-bubble or glass-bulb, while in a fluid or viscous state, and subsequently hardens into the transparent sphere you see before you. This spherical envelope, or diaphragm, is of such extreme elasticity and tenuity that the most infinitesimal pulsations of sound or light, even those of the violet rays of the spectrum—the number of distinct pulsations of which have been estimated at many millions to the inch—exert the most marked effect upon it, as I have proved to my complete satisfaction. The vibrations of this elastic diaphragm are, of course, transmitted to the sphere within, which is distant only about one-sixteenth of an inch. Here you see you have at once the principle of the telephone, have you not?"

I assented, and Mr. Espy went on:

"Very good. Now, how do we excite this sensitive diaphragm? Any vibrations, whether of light, or sound, or heat, will, of course, do so. The sound of our voices do so violently at this moment, but the receiver will not transmit the faintest echo of a response in answer. Why? Because such vibrations are too coarse for the delicately sensitive instrument before us. It might, it is true, reproduce sounds, but they would be of such exquisite tone as to be imperceptible to our gross auricular organisation. To what, then, is this instrument sensitive? Only to light-waves, to luminous pulsations conveyed to it under certain conditions, and, moreover, not in the ordinary manner by direct light-rays, but by their electric correlatives. It is to effect this end that these tiny rods radiate from and impinge upon the elastic diaphragm. Now do you comprehend the scope and purpose of the eidoloscope?" concluded Mr. Espy, in a triumphant manner.

"Partially so," I replied, hesitatingly; "but you have not yet explained whence these rays emanate."

"They emanate," returned Mr. Espy, "from surrounding objects within a certain distance, and this distance must not be great enough to preclude free electric transmission from the object to the receiver. An inclosed space of moderate size—a room, or apartment, of say twenty or thirty feet square—affords the best conditions for the successful operation of the process."

"And then what happens?" I queried.

"Scenes and occurrences of any and every nature that have ever transpired within a room in which the eidoloscope is placed, are vividly reproduced and acted over again upon the spherical mirror."

"You say 'any and every scene' is thus reproduced. Then why should any one particular scene enacted in the past be thus reproduced in preference to any other scene?" I asked.

"That also follows the subtle law which governs the manifestation," replied Mr. Espy; "heat is, as we know, a mechanical equivalent of light, light of electricity, electricity of both. Either force can be converted into any other, and this is the solution of the question you ask. It is temperature that governs the electrical emanations which cause the elastic sphere to vibrate, and thus reproduce the scenes enacted in a certain place in the past."

"But," I objected, "take the instance of a room which has been inhabited for centuries, as many rooms in old mansions have been, in what order or sequence would these scenes be reproduced?"

"They would appear upon the mirror," returned Mr. Espy, "in a reversed order of sequence—the last first, and so on to the earliest in point of time. Scenes would begin to appear upon the mirror as soon as the temperature of the room was sufficiently high to liberate the electrical energy stored away in the walls, ceiling, and furniture of the room, and cause that electrical energy to become charged with the light-rays which had once conveyed a message from every object within that room to every other object, and made each object the involuntary but silent repository of the history of every other object."

"But, my dear sir," said I, "this is a most startling theory which you suggest. How can you, as a reasonable man, account rationally for such an absurdity as that which you now advance?"

"Very simply," responded Mr. Espy, gravely, but without any sign of offence at my somewhat intemperate language; "you are enough of a man of science to admit these two propositions: First, that no force is ever lost in nature; and, second, that every form of force or energy is convertible into every other form. My eidoloscope simply reduces this formula to practice. The circles caused by the dropping of a pebble into a limpid pool, and which widen every moment as they recede, are not lost when they reach the shore; their splash may wash down a certain quantity of sand, or it may be thrown back as a reflux wave to meet a successor, but its initial force is not lost—it has merely changed its mode of action. The atmospheric vibrations caused by the sound of the words we now speak will continue to roll for limitless aeons through the limitless ether— light-rays in the same manner. What then happens when light-rays are stayed from their onward course—intercepted by the walls and furniture of a room, for instance? Are they therefore lost? I say no. The energy expended upon the material obstacles they encountered has effected a change in the collocation of the atoms of these objects, a change, it is true, imperceptible to any of our ordinary organs of sense, or ideas of measurement; but yet a change as real as that which would have been produced by the impact of a ball from a hundred-ton gun, the difference being not one of kind, but of degree. Yes, sir; the walls, ceilings, and furniture of a room represent the wax cylinder of the phonograph, and under proper treatment may be made to yield the electrical correlative of the light-rays which were once intercepted by them. I have discovered that proper treatment—and have I deserved badly of the scientific world, and must I be held up to ridicule because I am the first who has succeeded in doing so?" Mr. Espy concluded, with a certain degree of asperity and heat.

"And you have really ascertained, in a manner to convince yourself, that this appliance here is capable of reproducing the past as you have stated?" I asked.

"Yes," returned Mr. Espy, "my eidoloscope has passed the experimental stage and may now be classed with the scientific novelties of the age. Time alone will demonstrate to what uses it may be put. It may take the form merely of a scientific toy and become a source of amusement in households, while demonstrating a new law of optics, or it may be of benefit to the police authorities in locating crime and securing evidence against criminals. There are many uses to which the eidoloscope can be advantageously put. I may, hereafter, make adaptations and improvements in its structure, as has been done in the case of the telegraph, phonograph, and most other scientific inventions. But the principle is there, my dear sir; the principle is there. What you see here is only a model. I am here to explain its mechanism, just as I have now done to you, and to take orders from parties who would like to be supplied with it. There is one great advantage about it, too, and that is its simplicity. It does not require an expert to handle it. There is a small but very powerful battery concealed in the pedestal, and by simply pressing this button the circuit is completed and electrical connection established through these metallic rods, which, as you see, radiate in every direction, with all parts of a room. I am sorry it is so near the end of the season, or I am sure I should have received numerous orders for the eidoloscope. This is the first time, indeed, that I have been able to put even the model on exhibition, and you are the first person who has had the curiosity to put questions to me about it."

"You say you are prepared to supply orders for the instrument," I remarked; "is it expensive, may I ask?"

"Intrinsically, no," returned Mr. Espy; "the mechanism, as you see, is simplicity itself, and the first cost of the materials is not great. The adjustment of the elastic diaphragm to the spherical mirror at the proper distance is, however, a matter of much nicety. The packing of the instrument, too, for transport requires great care and entails considerable expense. Good results can not be secured with anything less than a three-foot globe, and when that is made of hollow glass, you can readily see the difficulty of packing it securely."

"I should very much like to see the instrument work," I said.

Mr. Espy told me he would let me know when he had one completed, and after leaving my address I departed.

The foregoing incident occurred about a week before the exposition closed, and the next and only subsequent time I saw Mr. Espy there, he told me he had received several orders for his instrument from English people, and purposed going to the great glass-blowing works of Newcastle-on-Tyne to execute them.

AFTER leaving Paris, I went to London, where I ran across an

old college friend, who invited me to spend a week or two at his

country-seat in one of the northern counties during the Christmas

season. Branthwaite Castle, my friend's place, was one of those

typical old English homes which have existed, been repaired, and

added to for the past two or three hundred years. Romantically

situated upon the banks of the upper Tyne, its old ivy-covered

walls and rambling wings were suggestive of legend as well as

comfort. There are few, indeed, of the ancient mansions of that

"borderland of old romance" which have not some weird, mysterious

story associated with their walls and halls. Branthwaite Castle

was not behindhand in this particular, and could boast of a

goodly assortment of stories, more or less ghostly and mythical,

associated with the family name of Haldane, which had figured in

the old border wars for centuries back.

The winter season at an English country-house, when there is snow upon the ground and outdoor amusements are necessarily curtailed, can not fail to be somewhat dull. The billiard-room for the gentlemen and the drawing-room for the ladies do not afford so many resources as to cause almost any new mode of recreation to be despised. Even private theatricals and dancing will pall upon the appetite if unrelieved by anything else, and so it was with something of the feeling of the mediaeval discoverer of unknown lands that I bethought me one morning of my friend, Mr. Espy, and the curious instrument he was exhibiting at the Paris Exposition.

Here were possibilities, indeed! Though I confess I did not repose much confidence in Mr. Espy's discovery, to the extent, at any rate, of the extravagant claims he made for it, I thought that, in any case, the mystery surrounding it and the occult problems with which it dealt, would serve to excite the imagination of the guests and provide a divertissement which might, for a time at least, banish ennui. Besides, could anything be handier? Mr. Espy was engaged in getting his glass globes manufactured at Newcastle-on-Tyne, and Newcastle was not forty miles distant from Branthwaite. I immediately communicated my plan, together with my Paris experience, to my host, who was delighted with the suggestion. Accordingly, the very same afternoon, I was driven to Cholorton Station, on the North British line, and two hours afterward found me in close consultation with Mr. Espy at his workshop in Newcastle.

After explaining the object of my visit, that gentleman gladly agreed to furnish me with an eidoloscope of even larger proportions than it had been his original intention to construct.

"For," he said, "I foresee the business benefit which will result from a successful introduction of the instrument at such a gathering as there is now at your friend's house. I will not only take especial pains upon its construction, but I will make a point of accompanying it to its destination, when completed, in person, and will personally superintend everything connected with its first exhibition, so as to leave no room for imperfect results. You can leave the matter in my hands, and meet me in a week at your station with the easiest wagon you can get."

DURING the week, it became noised about at the castle that

some peculiar surprise had been planned by our host and myself

for the gratification of his guests, and that its production had

been reserved for Christmas eve. Meantime, I received a letter

from Mr. Espy, in accordance with which I met him on the morning

of the day before Christmas at Cholorton Station, where the

north-bound train deposited him with a number of gigantic boxes,

the largest of which was a cube of some six feet in diameter.

These we conveyed with all possible care to the castle, where

their appearance created quite a sensation among such of the

visitors as had chanced to see them carried in at one of the back

entrances, and proportionately increased the expectation of

all.

Now came the important point of all to settle. In what particular apartment or chamber of the castle should the eidoloscope be set up and the test of its powers made? A committee of three ladies were let into the secret and selected by our host to decide this important question, in conjunction with Mr. Espy, Haldane, and myself. The ladies were all, more or less, connected with the family, and it was decided to give the matter the benefit of the quick, feminine intuition in the selection of a suitable place.

"Is there no room in the castle," asked Mr. Espy, when the committee had met, "which is associated above all others with some stirring incident, or series of incidents, which it would be interesting for your company to see reproduced as in actual life?"

"The difficulty is the other way," rejoined our host; "there are far too many such—quite an embarras de richesses, I assure you, in that respect."

"There is the state banqueting-chamber, where Queen Elizabeth dined," volunteered Miss Chantrey, a cousin of Haldane's, a lady apparently about sixty years of age, whose expression struck me as sinister and furtive in the extreme, despite the conventional smile and liberal application of cosmetics with which she strove to conceal it.

"Oh! yes," exclaimed another member of the committee, one of Haldane's sisters, gleefully; "how nice it would be to see Queen Bess sitting prim and stuck up, with all her starched ruffles, at the head of the mahogany table, and Leicester on one knee before her holding a cup of wine."

"The best place of all," said Mr. Espy, "would be a room in which the furniture has not been moved of late. The best results are, of course, secured where there are the most surrounding objects to gather the light-waves from."

"There is the blue room in the east wing where poor Aunt Margaret died," remarked Miss Jennie, another of Haldane's sisters; "I don't think a thing has been moved from its original place of forty years ago, except for an occasional dusting. Nobody seems to like to enter that room. There is a superstition connected with it, too. The old servants say—"

"Bravo, Jennie!" exclaimed Haldane; "I never thought of that. That is just the very kind of room Mr. Espy wants—isn't it, Mr. Espy?"

Here my eye happened to fall upon Miss Chantrey. Her face had become absolutely livid, her features drawn and pinched, and it was with a very forced attempt at calmness that she spoke:

"I am surprised at you, girls!" she said in a set voice; "the idea of selecting a place like that for such an exhibition! I am sure the banqueting-chamber would be infinitely more interesting."

"I am afraid," said Mr. Espy, "we should have to view hundreds of scenes before getting back to those of three hundred years ago. I am in favour of the blue room this lady spoke about. Forty years is not so long a time to be bridged over as three hundred. Besides the furniture, if I understand aright, has not been moved much during that time. That is a very favourable condition of things. By the way, did you not say there was some superstition connected with it?"

"The servants say they have seen a ghost—" began Miss Jennie.

"It all amounts to this," put in Haldane, laughingly; "my aunt Margaret, who I believe was a most beautiful girl—I was a child then and can not remember her—died there. There was some love affair—I don't know what it was—about it, and she got jilted or died of a broken heart or something. You ought to know all about it, Cousin Gertrude. You were about her age and staying here at that time, weren't you?"

"Yes," returned Miss Chantrey, with what I thought strained solemnity. "Poor Margaret! Hugh Wilmot is accused of playing with her affections and—"

"It is false!" cried Miss Jennie, her eyes blazing with indignation; "I have heard all about it, and I happen to know that Mr. Wilmot grew tired of life after poor Aunt Margaret's untimely death, and that was the reason of his going to California, where he died. It was you who were responsible for Aunt Margaret's death, if any one was, Cousin Gertrude. Old Jane Selby has told me how jealous you were of Aunt Margaret, and how you tried to catch Mr. Wilmot, and how he would have nothing to say to you," went on the girl, carried away by the heat of her emotions. "Old Jane was Aunt Margaret's nurse when she died, and she told me how careless you were whether she died or not, never even going near the sick room once during her illness."

If Miss Chantrey's face was livid and sardonic in expression before, it was now ashy pale, and there was a vindictive gleam in her little black eyes, as she listened to the impassioned tirade of her cousin, which boded no good to that young lady if it ever was in her power to do her an ill turn.

"Come, come, ladies!" said Haldane; "let by-gones be by-gones. I'm ashamed of you, Jennie! Mr. Espy, I think we had better select the blue room for your exhibition. It will be out of the way, and won't interfere so much with existing domestic arrangements. You'll help him, won't you, Robert?" he added, turning to me as he went out.

I ACCOMPANIED Mr. Espy to the room in question, whither the

boxes had preceded us, and stood open on the floor ready to be

unpacked. The room was lofty and spacious, even for the

Elizabethan period, to which that part of the castle belonged. It

plainly showed the marks of disuse, the high-backed chairs,

settees, tables, escritoires, and book-cases, all of antique

pattern, having evidently made the acquaintance of the

house-maid's duster only shortly before our arrival. Three

mullioned windows opened on the lawn—it was on the second

storey—and there was a large antique four-poster bed in one

corner on the side nearest the fire.

"Just the place!" murmured Mr. Espy approvingly, as he glanced at the surroundings. "Stop!" he added, addressing the servant, who was just about to set light to the fire. "That would spoil everything," he explained, turning to me. "Temperature, you will remember, is the one necessary factor in securing our results. Heat is the one and only element which causes the atoms of these walls and articles of furniture to change their collocation and to disgorge the electrical equivalent of the light-waves which impinged upon them in the past. That heat must not be applied till we are ready to begin."

We then began the work of preparation. A pedestal about four feet high, the top of which Mr. Espy said was insulated, and in the interior of which was a battery, was placed in the centre of the apartment. On this was set the polished globular mirror, five feet in diameter, and around this again was set the diaphanous elastic envelope, studded with the radiating rods. This took up a space some twelve feet in diameter, but as the area of the chamber was about double that, there was still room for thirty or forty persons to stand comfortably around—a number greater than that of the entire company at the castle.

ABOUT nine o'clock in the evening, when the gentlemen had

joined the ladies in the drawing-room, our host made a brief

address, explaining the nature of the surprise in store for them,

and ending by inviting them to accompany him upstairs to witness

the mysterious exhibition. As the company filed into the room,

Mr. Espy ranged them round the walls and proceeded to light the

fire, which, independently of its scientific value, was also a

physical necessity, as the night was bitterly cold. This done, he

placed a metal screen, which he had prepared for the purpose,

before the fire, excluding as much as possible the light from the

blazing coals, remarking that artificial light was detrimental to

the success of the exhibition. The few rays that struggled round

the edges of the screen only made the darkness visible. None of

the guests could distinguish the features of his nearest

neighbour.

All was silent, even whispering having been, at Mr. Espy's request, forbidden. Gradually the chill began to disappear and something like warmth to pervade the air, and at the same time a faint, bluish, phosphorescent light seemed to emanate from the central globe. In a minute after, its outline became defined, and then, as the room became warmer, the light from the globe became clearer, but more tremulous, changing in rapid gradations from grey to violet, from violet to pink, from pink to orange, and finally from orange to clear white. It reminded me exactly of dawn breaking, on a clear morning, in the east. But all this time it was not a clear white surface which the polished globe presented to our gaze. Just in proportion as its surface became bright, did the scene depicted upon it become more clear and vivid. It was an exact representation of the room in which we stood, and, had it been reflected from the globe by outside light, it could not, in some respects, have been mirrored more faithfully.

But there was no outside light to produce such a reflection. The light evidently proceeded from the globe, and by it we could now easily distinguish the faces and figures of the assembled company. There was another circumstance in the picture which at once precluded the idea of its being a reflection from the outside; had it been so, our own figures would have formed a prominent feature of the foreground, but they did not appear. Neither was the position of the different articles of furniture precisely the same as that which they now occupied. They were, indeed, all there. The mullioned windows, the book-cases, the bed, all the fixtures were just as we saw them then. But there was no sign of life. No human figure lent interest to the silent surroundings.

But while we gazed, the door, as seen upon the globe, opened, and a woman, evidently a servant, entered with a broom, backward. Swiftly and noiselessly this figure went through the motions of dusting furniture. Never did house-maid work with one-hundredth part the celerity as did this phantom then. In a few seconds she was gone, again moving backward through the door.

Mr. Espy now explained, in a low voice, that the scenes were reproduced in backward sequence, and that consequently the figures must appear to do backward all that they had done in the past.

Again did that and other figures appear and retire at intervals, all acting similarly in the matter of retrogression. The spectators became spell-bound. It seemed as if time were forgotten in the absorption with which they viewed the passing spectacle. It seemed also as if every one there nursed an indefinable expectation of something about to happen, they knew not what.

At length, a bevy of servants entered and busied themselves about the bed. They were followed swiftly by two men who entered backward, bearing a coffin, which they set beside the bed. From it they lifted the corpse of a young lady, which they proceeded to set upon the bed. Then they left the room, backwards, and were succeeded by some men and women, who knelt beside the bed. Presently the corpse of the young lady opened its eyes. There was now a table beside the bed and on the table some medicine-phials and glasses. Next, a young lady entered backwards and backed up to the bed.

"Gertrude Chantrey, by God!" was the suppressed exclamation I heard issue from the lips of an old gentleman standing by my side. "Gertrude Chantrey, as I knew her forty years ago when her cousin Margaret died!"

This young lady swiftly and noiselessly changed some medicine-phials upon the table.

Just then I thought I heard a faint sound, as of a stifled groan, proceeding from an obscure quarter of the room, but so intent was every one upon what was transpiring, that it failed to attract any notice. Countless other scenes were depicted upon the spherical mirror, but so swiftly and in such incongruous order that the mind failed to grasp their relevancy, as there was no sequence, their sequence itself being inverted, and cause, so to speak, following effect.

The last scene that I remember was the figure of a beautiful young lady seated at one of the mullioned windows. A young gentleman entered and approached her backward, fell on his knees before her, rose up, and acted generally as lovers do.

"My God!" whispered heavily the same old gentleman; "Hugh Wilmot and Margaret Haldane to the life! Just as they were forty years ago."

How long this strange exhibition might have lasted I know not. Every one, as I have said, seemed spell-bound by the extraordinary scenes there witnessed. Suddenly the deep tones of the tower clock struck twelve. Was it possible, I asked myself, that we had been there three hours? We had entered the apartment at nine; but a few minutes seemed to have passed; now it was twelve!

The thought seemed to recall the company to itself. Another incident likewise helped to do so. From a settee, in the embrasure of a window, the figure of a female slipped noiselessly forward and fell prone upon the floor. I instantly recollected that this was the quarter from which had proceeded the low moan I had thought I heard some time before. A general rush was made to the spot, and tender arms raised the flaccid figure of the lady. I pressed forward among the number. It was the figure of Miss Gertrude Chantrey. The features were rigid and the body was fast assuming the chill of death.

Robert Duncan Milne,

San Francisco, January, 1890.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.