RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on the painting "The Death of Hercules"

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on the painting "The Death of Hercules"

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664)

Robert Duncan Milne (1844-1899)

THE Scottish-born author Robert Duncan Milne, who lived and worked in San Fransisco, may be considered as one of the founding-fathers of modern science-fiction. He wrote 60-odd stories in this genre before his untimely death in a street accident in 1899, publishing them, for the most part, in The Argonaut and San Francisco Examiner.

In its report on Milne's demise (he was struck by a cable-car while in a state of inebriation) The San Fransico Call of 17 December 1899 summarised his life as follows:

"Mr. Milne was the son of the late Rev. George Gordon Milne, M.A., F.R.S.A., for forty years incumbent of St. James Episcopal Church, Cupar-Fife. and nephew of Duncan James Kay, Esq., of Drumpark, J.P. and D.L. of the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright, through which side of the house, and by maternal ancestry (through the Breadalbane family), he was lineally descended from King Robert the Bruce.

"He received his primary education at Trinity College, Glenalmond, where he distinguished himself by gaining first the Skinner scholarship, which he held for a period of three years; second, the Knox prize for Latin verse, the competition for which is open to a number of public echools in England and Ireland, and thirdly, the Buccleuch gold medal as senior and captain of the school, of the eleven of which he was also captain.

"From Glenalmond Mr. Milne proceeded to Oxford, where he further distinguished himself by taking honors, also rowing in his college eight and playing in its eleven.

"After leaving the university he decided to visit California, a country then beginning to be more talked about than ever, and he afterward made the Pacific Coast his residence. In 1874 Mr. Milne invented and exhibited in the Mechanics' Fair at San Francisco a working model of a new type of rotary steam engine, which was pronounced to be the wonder of the fair.

"While in California Mr. Milne for a long time gained distinction as a writer of short stories and verse which appeared in current periodicals. The character of his work was well defined by Mrs. Gertrude Atherton, who said:

"'He has an extravagant imagination, but under it is a reassuring and scientific mind. He takes such a premise as a comet falling into the sun, and works out a terribly realistic series of results: or he will invent a drama for Saturn which might well have grown out of that planet's conditions. His style is so good and so convincing that one is apt to lay down such a story as the former, with an anticipation of nightmare, if comets are hanging about. His sense of humor and literary taste will always stop him the right side of the grotesque.'"

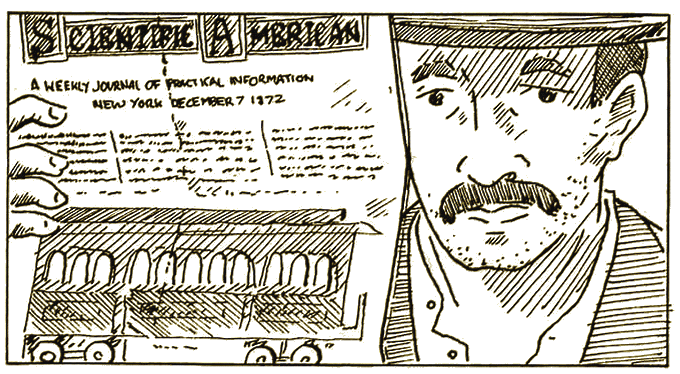

A caricature showing Robert Duncan Milne and a San Francisco cable-car.

In Greek mythology, Nessus was a centaur killed by Hercules. While dying, Nessus told Deianira, Hercules' wife, that if she ever had cause to doubt her husband's love, she should wrap him in a shirt soaked in Nessus' blood as this would ensure his constancy. Deianira followed this instruction, but the centaur's blood was a powerful poison that killed Hercules by corroding his body. In literature the term "Robe (or Shirt) of Nessus" denotes that which causes inexorable destruction, ruin, or misfortune.

"I COULD tell you," said the Basque shepherd, as he lit his pipe after supper, and drew his stool closer to the fire, at the same time filling a pitcher with red wine from a keg in the corner, and handing me a cup, "I could tell you a story of the great world of society—a story of which I am now the only depositary; and it can be no harm to tell it, for all those to whom it relates, including my own Lisette, are dead. Ah, me!" continued he, passing his hand reflectively over his forehead, "the curse of that night's work fell upon her, too."

I had been traveling all day in the foot-hills of the Sierra Nevada of Mariposa County, and at night found myself partaking of the hospitality of a shepherd's cabin. My host, despite his rough garb, had the appearance of a man of experience and meditation; and his bearing betokened that though not "to the manner born," he had yet acquired something of that which characterizes the social intercourse of gentlemen by contact or attrition. He took a deep draught of wine, looked thoughtfully in the fire a moment or two, and began:

"You have been in Paris? Twelve years ago? Ah! then you could not have had personal knowledge of the events I am going to tell you about, for they occurred two years earlier, in '64. Nevertheless, you may remember reading in the papers of the day about the burning of the mansion of the Marquis de B., during a bal masqué, and the elopement on the same night of Madame la Marquise with a certain Abbé, at that time well known in Paris. Ah! you remember hearing something about it? Well, whatever you may have heard or read was not true. I alone of living men—for even the Doctor, who is now in the galleys, can only suspect what happened—can give you the true story of this affair, for I was a principal actor in it. To tell it will relieve the burden of my mind—that is, if you care to hear it?" politely queried the shepherd. Being assured that nothing could be more seasonable and welcome than a story at such a time, after throwing another log upon the fire, the Basque shepherd began:

I WAS not always as you see me now, but ill-luck has followed me since I left France. It is true that I am one of the people, but my condition was once much better than it is now.

At the time I speak of I held the position of valet de chambre to the Marquis de B., and Lisette was what you call lady's maid to Madame la Marquise. I was then younger than I am now—not more than thirty years old; and Lisette was twenty-five. We had saved our earnings for several years past, and intended to leave service in the autumn and marry, and go back to Béarn, where we had decided to open a hotel—but it was never to be.

Monsieur the Marquis was tall, and proud, and rich; Madame la Marquise was tall, and proud, and beautiful, but not nearly so pretty to my taste as Lisette. Monsieur was fifty years old, and Madame was (Lisette told me she found it out from the back of a miniature) thirty-five. Monsieur was fond of gayety, and so was Madame; and to outsiders it must certainly have appeared that they were a very happy, well-matched couple. But we of the household had, of course, opportunities of observing every little thing that went on, and Lisette and I would often compare notes and draw conclusions from what we saw and heard.

About three months previous to the time of which I write, Madame la Marquise had fallen out with her father confessor, and taken a new one in his stead. The Abbé R. was as fine looking a man as I have ever seen. He was as tall as the Marquis, but much younger; his carriage erect, his bearing stately, his eye keen, his nose aquiline, with a good-humored smile always playing round the corners of his month. He was very kind and pleasant to Lisette and me, always speaking to us when he called, and generally bestowing a five-franc piece on one or other of us, and on one or two occasions even a Napoleon. He used to call very frequently upon Madame la Marquise, who received him in her boudoir, which opened by one door into the grand salon, and by another into the conservatory. Lisette used to say that she thought Madame must have been committing more sins than usual of late, since it took so much longer time to confess them; but this was only to me, for we were much too discreet to let our thoughts be known at large. The Abbé generally came in the forenoon, when Monsieur had gone down to his club or was amusing himself in the billiard room, for Monsieur troubled himself very little about the religious exercises of Madame.

About two months after the Abbé began to pay his visits, Lisette came running into my room one morning very much excited and flustered, saying that there had occurred a grand émeute between Monsieur and Madame in the grand salon; that Monsieur was walking up and down with folded arms, and stamping with his feet, and looking as black as night; while Madame was reclining on a sofa in tears, her face buried in her hands. Lisette had seen them through the keyhole; and something very unusual and extraordinary must evidently have happened, though we never knew what it was. We, however, connected it somehow with the Abbé, for we noticed that from that day he came no more.

For a week after this Madame was very sorrowful and triste, while Monsieur remained sombre and terrible. Then Madame brightened up all of a sudden, and began to approach and coax Monsieur so assiduously, and in such a pretty, winning way, that Monsieur relaxed his gloomy mood, and soon the whole household knew that preparations were on the tapis for a grand masquerade ball, which was to eclipse anything of the kind ever seen in Paris since the golden days of Louis Quatorze; for Monsieur the Marquis was very rich, and not at all afraid of spending his money.

This was in March, and the ball was to take place just before the holy season of Lent, in order, as Lisette said, that the great folks might have pleasant memories to carry them through those dull weeks when they were debarred from the actual pleasures themselves. Our house was one of the finest in the Faubourg St. Germain, and stood alone within its grounds. The grand salons were au premier, comprising five apartments stretching through the entire wing, Madame's boudoir being at the end of the two salons which ran along the side wing, opening on to the conservatories. Everything was being turned topsy-turvy. The polished oak floors were waxed in three of the salons for dancing, while the two next the conservatories, furnished with the richest carpets and decorated with a profusion of mural hangings, were reserved for conversation and lounging. I remember all the particulars as well as if it were yesterday. Parterres of flowers and groves of trees were borne in from the gardens. Water-pipes were laid cunningly along the walls and in corners to distribute perfumed spray, and aid in cooling the air. It was the day of the ball, and I happened to be engaged in performing some little offices in the conservatory salons, near Madame's boudoir, when fortunately, or unfortunately, I became the participant of a conversation which was going on therein, and which struck me from its peculiarity at once. The dialogue was being carried on by Madame on the one hand, and a male visitor on the other. It was Madame who spoke:

"Then Monsieur is sure there is no risk of detection?"

"None whatever, Madame," answered the visitor. "In order to prove to yon with what caution and discretion I have executed your commission, I will tell you that I, with my own hands, prepared the fibres; that I then sent the silk to a loom at Lyons, whence the piece was shipped to a costumier in this city and made up by his workmen. I have carefully concealed every trace of these several steps, so that in the event of any unforseen occurrence the chance of collecting the links of evidence in a connected chain are reduced to a mathematical minimum."

"Will Monsieur the Doctor please to explain again the nature and operation of this dress, so that I may be certain to commit no inadvertence?" continued Madame.

"With pleasure," responded the visitor. "The substances with which the fibres of the silk are impregnated are well known to chemists, though not in the combination in which I have used them. The effect of the warmth and moisture of the skin upon these substances is such as to draw out their properties very gradually. Their action, imperceptible at first, manifests itself primarily in a delicious langour, which, in its turn, gives place to aphasia and paralysis of the nerves and muscles. In this condition the subject may be kept utterly helpless, but in full possession of his senses, for about half an hour. The dress must then be removed—be pleased to particularly remember this—or spasms will supervene, actual paralysis ensue, and finally death."

"But surely Monsieur does not suppose that I should allow the last contingency to happen?"

"Certainly not. Your object, as you confided to me, is to keep your friend in a condition of helpless consciousness, or conscious helplessness, while you carry out the object you have in view. So far as I am concerned it is a feature of the masquerade. Nevertheless if the contingency I have referred to should happen, Madame la Marquise may rest assured that the cause of it would ever remain a secret, even to the most experienced physiologist."

"Proceed, Monsieur le Doctor."

"I have so accurately gauged the quantity and strength of the substances which permeate the silk, that death will result only as a consequence of their complete absorption by the pores. Their action being directly on those myriads of nerves the extremities of which underlie the entire surface of the skin, with a counter action on the muscular system, no trace will be left of their presence in the tissues, or any of the secretions. The most skillful and suspicious chemist would be baffled in detecting the least soupçon of the substances, either in the silk or in the person, and his verdict would be, 'death from paralysis.'"

"God forbid that it should ever be put to the test," piously ejaculated the Marquise. "Long before then my object will have been accomplished, and orders left with the servant to undress my friend, and to destroy the dress."

"Yes, in that case the dress had better be destroyed. Permit me to thank Madame for the ten thousand francs, which I have had the pleasure of drawing from her bankers. May success and pleasure await her in her little experiment with her friend. Adieu."

I stood motionless with surprise on hearing these words, the singularity of which caused them to be so deeply engraved on my memory that I remember them distinctly, even at this distance of time. I could comprehend that they threatened evil to some one who was an object of aversion to the Marquise. But what evil? And to whom? I retreated behind a large porcelain vase in the conservatory, and awaited developments. The door of the boudoir opened, and a man whose appearance betokened his business to be that of a costumier, with a large bundle of goods under his arm, emerged from the boudoir and passed through the salons on his way out.

In spite of his disguise, and the way in which his cap concealed his face, I recognized a well-known physician of the Quartier Latin, whose character for honesty was as low as his reputation for skill in his profession was preeminent. I was just making up my mind what to do, when a groom of the chambers approached the boudoir, intimating to Madame that another costumier was in waiting. I determined to remain where I was and await the event. The door of the boudoir closed behind a tall figure enveloped in a cloak, the face closely ensconced beneath a slouched hat of exaggerated proportions, but whose tout ensemble seemed familiar to me. The lace curtains which veiled the windows of the boudoir looking into the conservatory were so carefully drawn that it was impossible to see anything through them, but I could hear the sound of the quick rustling of a dress; and then a sound as of sighs, alternating with another sound which I conceived to be that of kissing; and then the whispered words:

"François!"

"Mathilde!"

I recognized the voice. There could be no doubt about it. It was the Abbé. "Ha, ha! Monsieur l'Abbé," I thought, "you are a bold man to dare the vengeance of my master in this manner; but, ma foi! in spite of your five-franc pieces and Napoleons he shall know it, and then "—[Here the Basque shepherd replenished his tin pannikin with wine from the pitcher, and, taking a deep draught, resumed:]

"The Marquise came to the window, drew aside the lace curtains, and looked cautiously out up and down the conservatory. I crouched more closely behind my vase, and remained unnoticed. She drew the curtains again, satisfied, and retired. A conversation ensued between the Abbé and the Marquise, which has, like the former one, been indelibly impressed on my mind by succeeding events.

"At last," murmured the Marquise.

"At last," responded the Abbé.

"Is everything arranged?"

"Staterooms are secured on La Belgique, from Havre, at eight to-morrow morning. We leave Paris at midnight. A carriage will be in waiting at the north door to convey us to the terminus. Once on board we are safe from pursuit. In America our new life begins. Our name is Dubois."

"You have had the money transferred?"'

"Yes. Here are the vouchers; and the robe—?"

"Is that of Mephistopheles. It is our friend's selection."

"Nothing could be more appropriate—Mephistopheles outwitted," laughed the Abbé.

"You like the idea of the medicated dress?"

"Admirable I It is a stroke of genius."

"For which we must thank the Doctor. He considered it much more suitable to the purpose than anaesthetics."

"Yes, I see. Mere stupor or insensibility would have taken away the point of the coup and robbed your departure of its éclat. It would have been a story without a moral."

"I can fancy him lying there upon the sofa, impotent in his fury, incapable of speech or motion, yet appreciating all, while we stand before him leisurely holding our last confidential talk before leaving. N'est-ce pas drôle, mon ami?"

"And waving him a last adieu as we go out."

"I must at least kiss him once before saying good-bye," plaintively remarked the Marquise.

"And leave orders for his nurse to undress le pauvre enfant, and put him to bed," laughed the Abbé.

I was now all attention, but the voices were lowered, apparently discussing some more confidential matters. I had, however, heard enough to convince me that the dress referred to in the two conversations I had overheard was destined to be worn by the Marquis, for I was already aware that he had decided to appear in the rôle of Mephistopheles. Further than this, I could gather that the Marquise and the Abbé were plotting in concert; that they were evidently on the most intimate terms, and that the Marquis was the object of this conspiracy. The conversation was presently resumed in a louder key.

"And this is your dress, François—a Mephistopheles, like our friend. When he retires to repose here, on my invitation, at eleven o'clock, you will take his place in the salons. Your ensemble is similar and the personation will be perfect. Besides, it will heighten the effect of our farewell when he sees his place occupied by so flattering a representation of himself," laughed the Marquise.

"If—suppose—ha! ha!—you have, of course, provided against it—some mistake should occur, and the dresses get changed. The notion is not a comfortable one."

"Impossible. Voila! Our friend's suit is adorned with two little crosses of white ribbon, one here on the back of the collar, the other on the left ankle of the hose. Yours is free from such embellishment."

"Your providence is delightful."

"An apartment au troisième has been assigned you as costumier. I will carry your dress thither with my own hands. You will appear on the floor at eleven. If I have occasion to communicate with you our password is 'croix blanc.' Now go."

"Till eleven, then. Au revoir!" and the cloaked costumier passed out, presently followed by the Marquise, attired for her daily drive in the Bois.

During the latter part of this conversation my feelings had undergone a revulsion. Disgust and loathing had taken the place of curiosity. Could it be possible, I asked myself, that France—that the world—could produce such embodiments of baseness and malignity? Was it possible that a crime such as was contemplated could be committed for the attainment of any object whatsoever? Was it possible that this could be Madame la Marquise, whom I had known for so many years, without knowing her true character; or had her character become horribly and suddenly perverted and changed? I passed my hands over my forehead to wipe away the drops of perspiration which had gathered on it like dew.

I tried vainly to persuade myself that it was some horrible nightmare. I tried to move, to crawl away, but some deadly fascination that I could not resist nullified the power of my will, and arrested motion. Gradually the contemplation of the enormity of the deed yielded to the desire to counteract and thwart it. This in its turn produced excitement. I rose from the shadow of the vase. I flew to Lisette, whom I found in her room, and she started on seeing me as if I had been a ghost.

"Run!—fly!" I cried; "quick! change the ribbons on the dresses, or we are ruined—lost!"

The poor girl burst into tears, and fell on her knees, invoking the saints for protection. She thought I had gone mad. But I caught her in my arms, and almost carried her along to the boudoir of Madame. There lay the two red silken suits of tunics and trunk-hose—both identical costumes of Mephistopheles, except that on the collar and ankle of one suit there appeared little crosses of white ribbon.

"Now, Lisette," I cried, "as you value my love—as you value your own life—as you value your hopes of heaven, take a needle and thread, and—quick!—detach these crosses of ribbon from this suit, and sew them in exactly the same positions on the other."

The poor girl trembled and looked at me with a frightened expression, saying not a word, through fear, for she was now thoroughly convinced I was mad; but obeyed me mechanically as speedily as her fright would allow her, and at length the ribbons had changed places on the garments. I then laid the suits back carefully in the same relative positions in which I had found them, led Lisette back to her room, and implored her to calm herself and that I would tell her all in time.

I had hitherto acted without thinking, and purely on the impulse of the moment. Now, the blood rushed through my head like a torrent, as I at last took time to consider. What had I done? Had I not rendered myself a party, in some manner, to this horrible machination? I had introduced a new combination into the event, the consequences of which appalled me. Was I not responsible for something? But what? My brain reeled. I could not collect my thoughts. I rushed into the boudoir determined to destroy the horrible garments, fraught with I knew not what deadly peril to the household. I resolved to destroy the dress instantly. I approached the ottoman on which they lay. My cowardice got the better of me, and I feared to touch them. If I did take them, how shall I account for their disappearance? Madame would miss them instantly on her return. Lisette, who alone had the privilege of entering the boudoir, would be questioned, and she, poor, simple girl, would confess the whole. How should I account for my possession of the terrible secret? My fear of the personal consequences to myself and her was too great to permit of my taking action. I heard a step outside, which caused me to retreat in precipitate alarm to the conservatory. It was merely one of the workmen coming to complete the adjustment of the hangings in the salon. Once out of the boudoir I dared not return, and, by that action, or want of action, the event was sealed. Then I determined to go at once to the Marquis and tell him all that I had seen and heard. I hastened to his study. It was empty. To the billiard-room. He was not there. I questioned the concierge. He informed me that the Marquis had gone to his club. I jumped into a carriage and drove thither, but to find that he had gone with a party to Versailles. I returned to the house, and again sought Lisette and confided all to her. It was with difficulty I could make her understand the situation. When she did so, the effect was different from what I had anticipated. She laughed at my fears, and tried to persuade me that all I had heard merely related to some ingenious tableau—some mechanical surprise—which Madame was going to inaugurate for the pleasure of her guests. But the Abbé? I urged. Lisette laughed. Why should not the Abbé come to the masqué? He was a very pleasant, courtly gentleman, and she could see nothing wrong if he did admire the Madame. I was in despair at her stupidity.

"Let us fly, Lisette!" I cried; "let us go back to Béarn at once, where we can live happily and away from these distracting scenes."

"What?" she exclaimed, "and forfeit our wages? Ma foi, Philippe, but you are mad. Besides, if the terrible denouement you apprehend should really occur, would not our flight be construed into an acknowledgment of guilt, and should we not be arrested and brought back to answer for anything which might happen?"

My reason told me that this was only too true, and was, in fact, an unanswerable argument. I therefore determined to trust to circumstances, and await the event, telling all to the Marquis at the earliest possible moment.

At four the Marquise returned from her drive, and summoned Lisette to the boudoir. I made pretense of doing something in the salon, and observed them come out and retire to the apartments of the Marquise, Lisette carrying in her hands the two dresses. The guests would not begin to arrive before ten, and the long hours seemed ages as they passed slowly by, while I awaited the return of the Marquis. Seven—the dinner hour—arrived without the Marquis, and Madame dined alone. My excitement increased as the evening wore on, till I was absolutely in a fever. How should I approach the Marquis when he did arrive? How break to him the terrible news, the possession of which was so important, yet so sinister? I tormented myself as to the manner in which I should begin, and the way in which he was likely to receive my communication. I knew well the ungovernable nature of his passion when it was once fairly aroused—which, to do him justice, seldom happened. He was usually débonnaire and familiar with me, and I flattered myself that I could even broach an unpleasant topic with a certain degree of security and confidence. But this—I trembled to think of what might happen. It was then with feelings of trepidation akin to guilt that I at last saw the carriage draw up before the portico, and the Marquis alight and retire to his apartments. I was summoned to attend him almost immediately. The private suite of the Marquis consisted of three chambers: the first, or outermost, being an antechamber; the second, a lounging room; and the third, a bed-chamber. The Marquis usually occupied the second of these, and was there when I entered. He seemed in capital spirits and good humor.

"Well, Philippe," said he, "is everything ready? Paris expects me to play the fool for an hour or two, and I suppose I must get in trim to do it. You have got the Mephistopheles, eh?" and he yawned, stretching himself on a sofa, and puffing a cigarette.

"If Monsieur the Marquis will permit me to say," I began, and then hesitated, nervously arranging things about the room, and unable to proceed.

Monsieur took no notice of my words, but puffed away abstractedly at his cigarette.

"Something has happened which Monsieur—that is the Marquise," stammered I in a manner utterly bête and unlike myself, which attracted the wandering attention of the Marquis.

"Eh, Philippe? You have a message from Madame!"

"Pardon, Monsieur. I was about to relate a matter of great importance. I was in the conservatory at the time. The Abbé—"

"What!" thundered the Marquis, springing up from the lounge. "What did you say? The Abbé R. in my house—in the conservatory? Villain," advancing and seizing me violently by the collar, "quick! explain yourself; or by—"

"Do but hear me, Monsieur," entreated I, struggling in his grasp, "it was not my fault. If Monsieur will but listen to me I will explain—"

"You lie!" he shouted; "the concierge and the servants had strict orders not to admit that person. If I find you deceived me, or are practicing on my credulity, to serve your own ends—whatever they may be—by God, I will"—and he tightened his grasp on my collar.

He was physically much more powerful than myself, and I shuddered at the thought of a hand to hand contest. I thought the best thing I could do was to keep silence. In a few seconds he released his grip on my collar. He was evidently collecting himself. Curiosity and interest were getting the better of passion. Presently he let me go, and commenced striding up and down the room. I had succeeded so badly in my attempt to introduce my story that, come what would, I determined to let him lead the conversation this time.

"You say the Abbé R. was in my house to-day," he said at length—"be careful how you answer—how did he get in?"

"In the disguise of a costumier, if it please Monsieur."

"Where did you see him?"

"In the boudoir of Madame."

He stopped short in his walk, faced round, looked at me with an expression fierce as that of a wild beast, his frame shuddering violently. He made a move toward me; then restrained himself; I meanwhile standing still near the dressing table. He essayed to speak, but failed. He resumed his mechanical walk. In a minute he stopped again.

"Philippe," he hissed out, "whatever you may have heard or witnessed, I charge you to tell me everything, without fear or reserve; but beware of concealing or garbling the facts. Proceed."

He remained standing, and I began to tell him the interview of the Marquise and the doctor, as I have told you; and as I proceeded I could see his face harden, his teeth set, and a ghastly pallor spread itself over his whole features. Sometimes he would walk up and down during my narration, sometimes pause—but his actions were mechanical. I went on to tell him of the interview between Madame and the Abbé, expecting another ebullition of passion every moment; but none came. Instead, there was a coldness and rigidity of countenance, expressive of some unalterable determination. After thinking a little he spoke.

"Philippe," he said calmly, "you have rendered me a great service; I shall not be forgetful of it. There is yet another service which you must do me—the last one. You love Lisette. You are engaged to be married. You have been in my service a long time. To-night that service ends. Between you I owe you about eight thousand francs. I will make it fifty thousand on condition that you start off for America to-night."

"But, Monsieur," I began, taken quite aback, "consider the time—besides we are not married."

The Marquis pulled out his watch, and rang a bell. "It is already nine o'clock." Then to the servant who answered the summons: "Take a carriage and bring M. Lavoisier, the Notary, here immediately. Make haste." The servant bowed and retired.

"Go," continued the Marquis, "and present my compliments to Madame the Marquise, and say that I should like to see Lisette for a few moments, if she can spare her. I presume you accept my conditions? Events may occur tonight of such a character as to necessitate your arrest and detention as witnesses. It is for your interest as well as for mine that you should leave France. You must be aware of this."

I was completely bewildered. All my plans of life scattered to the winds in a moment! No going back to Béarn now! The superior will of the Marquis mastered me. Had I reflected, I might have hesitated. As it was—America? I had heard a great deal of that country. And fifty thousand francs! It was a fortune I had never dreamed of.

I went to the apartments of Madame la Marquise, and, by one of the attendants in the ante-chamber, sent in the message of the Marquis. Lisette came out.

"Lisette," whispered I, "come with me at once to the apartments of the Marquis. We are to be married and go to America with fifty thousand francs to-night."

Lisette looked at me as she had done when I made her change the ribbons on the dresses, as if she suspected my sanity. She made a movement to escape back into the chambers of Madame, but I was too quick for her. I caught her by the wrist; and, while conducting her to the apartments of the Marquis, tried to get her to understand what was required of her. The suddenness and strangeness of late events had been too much for her, and she obeyed mechanically. I told her to remain in the ante-chamber while I went in. The Marquis was seated at a table writing. He had become cool—preternaturally cool; not a trace remained of his late excitement. He did not look up as I entered, but continued writing. I stood waiting in silence.

Presently a knock was heard at the door, which I hastened to answer. It was the Notary, whom I at once ushered into the presence of the Marquis.

"Good evening, Monsieur Lavoisier," said the Marquis, "pray be seated. Is Lisette here?" addressing me.

"She waits, if it please Monsieur," replied I.

"Call her."

I brought her in, and we stood before the Marquis and the Notary, who were seated at opposite sides of the centre table.

"These young people wish to be married, Monsieur Lavoisier. Please draw up the necessary papers at once, as we have no time to lose."

The Notary did as he was bid; and, the questions and formalities having been gone through, I and Lisette were man and wife; and the Notary, pocketing his fee, retired.

"I have instructed my bankers," resumed the Marquis, tapping with his hand the letter he had written, "to place to your credit at New York the sum I have mentioned. You will leave Havre by the Belgique to-morrow. A carriage will be in waiting to-night at the north door to convey you to the terminus," he added, looking significantly at me. "Lisette is now at liberty to return to her duties until then, but must not breathe to anyone the slightest hint of what has passed. Make her comprehend this, Philippe, and then return immediately."

I accompanied Lisette back to the apartments of Madame, impressing upon her the necessity of preserving absolute secrecy on what had passed, and told her to be ready to leave at any moment. I then kissed her and returned to the Marquis.

The noise of carriages in the court, and the subdued hum of voices in the salons below, were sufficient evidence that the guests were arriving in force, for it was already past ten o'clock. It did not take long to attire the Marquis in the red silken tunic and trunk hose which Madame had intended for the Abbé; and, with the addition of the short cloak, sword, and feathered hat, together with the mask (counterparts of all of which had been furnished to the Abbé), it must be confessed he bore a very striking resemblance to the conventional Mephistopheles of the stage. While dressing he gave me commands as to what I should do in respect to Madame and the Abbé, the purport and effect of which the sequel will show. He then descended to the salons, leaving me alone.

The excitement I had gone through, so unusual to my mode of life, had acted as a powerful stimulus to my brain and nerves; and I now felt like a man under the influence of strong intoxicants, having all my energies strung up to do or dare whatever acts circumstances might lead to, but without that blunting of the mental faculties which liquor usually imparts. My perceptions were strangely acute, but I would not allow myself to reflect. I saw clearly into what perilous complications I had suffered myself to be drawn, but I consoled myself with the idea that I was serving my master faithfully, and that a few short hours would put Lisette and myself beyond the reach of danger.

My first command had been to put myself as much as possible in the way of Madame, so that she might employ me as the bearer of any message she wished to send. With this object I descended to the salons and mixed with the revelers. Everything was as brilliant and attractive as unlimited expense and faultless taste could make it. The beau monde of France was there enjoying itself as only the beau monde of France can. The bluest blood of the ancien régime was disporting itself with an abandon which can only be arrived at in the masqué. It was rumored that the Emperor himself would grace the fête with his presence; and, indeed, from what I know of the foibles of royal personages—for I have attended the Marquis at all the courts of Europe—he may have been at that very moment on the floor, as merry as the maddest of them all.

I pushed through the dazzling and ever changing throng of knights flirting with shepherdesses, and Greek goddesses languishing with blackamoors, and espied the Marquise, attired as an odalisque, in the conservatory salon, next the boudoir, where I had expected to find her. She seemed preoccupied until her eyes lighted on me, when she instantly beckoned me to her.

"Philippe," said she, "go at once and find the Marquis, and tell him that I have something important to say to him if he will meet me in the boudoir. After you have accompanied him thither, go to the blue room au troisième and say that Madame la Marquise wishes to see Monsieur Croix-Blanc, the costumier, for a few moments in the north corridor."

I bowed and hastened to find the Marquis by appointment in the furthest end of the five salons, and acquainted him with the message of Madame. He accompanied me to the north corridor, where at his request I detached with my pocketknife the little white crosses of ribbon from his dress, and leaving him proceeded to the room of the Abbé au troisième.

I knocked at the door, and was answered from within in a disguised voice requesting to know what I wanted; but the door was not opened, from which I inferred that the Abbé had not yet completed his toilet.

"Madame la Marquise," said I, "desires to see Monsieur Croix-Blanc immediately in her boudoir."

"In her boudoir, did you say?" queried the voice.

"Assuredly, Monsieur," replied I. "Madame told me to say that an unforeseen occurrence necessitates the presence of Monsieur Croix-Blanc in her boudoir immediately."

"Tell Madame that I hasten to obey her commands," returned the voice. "The way is known to me; I shall not trouble you to conduct me thither."

I felt perfectly confident on this point, but was well aware that the Abbé did not wish to appear to me in the exact costume of the Marquis, as such a step would be likely to arouse my suspicions, so I ostentatiously withdrew in order to give him an opportunity to gain the salons without risk of detection. Once there he had nothing to fear, except a personal rencontre with the Marquis, which he, of course, trusted to the Madame to guard against.

It was now my role to time my return to the Marquise with such nicety as to draw her away from the vicinity of the boudoir before the approach of the Abbé, but yet not incur the chance of her seeing him as he descended the stairs. A gesture of recognition from him would have ruined all, should he chance to see her, while on the other hand a glimpse of Mephistopheles on the stair-case would have equally revealed the identity which it was now the object of the Marquis to obscure. I accordingly loitered near the bottom of the stair-case until I heard footsteps in the story above, and then speedily presenting myself to Madame, informed her that the Marquis was then approaching the boudoir, and that Monsieur Croix-Blanc was waiting in the north corridor.

["Reflecting upon my conduct of that night," here interposed the Basque shepherd, addressing me, "even at this interval of time, I feel deep shame for my duplicity, however well meant. I was carried away by the feelings and interests of the moment, and truly, bitterly have I paid for it!" He resumed the narrative.]

It was the object of Madame not to meet the Marquis, but to entice him into her boudoir there to wait. She, therefore, avoided the nearer salons and passed into the conservatories. I presently followed her, having been instructed by the Marquis to take up my position behind the vase, and give him notice by a preconcerted sign when the influence of the medicated dress should have reduced the Abbé to helplessness.

The night was warm, and one of the windows of the boudoir had been left with a leaf partially open, through which, from the position I was in, the interior was visible. In a few moments the door from the salon opened, and there entered a Mephistopheles, whom by height, figure, carriage, and dress I could not have distinguished from the Marquis had I not known it was the Abbé, so well had art assisted nature in effecting the resemblance.

He stood as if in thought for a moment or two, and then began pacing the floor in a restless manner. The bijou clock of the boudoir tinkled out eleven. The Abbé paused, turned, looked irresolute, and finally with a gesture of impatience threw himself at full length upon a sofa, his cheek resting on his hand. I watched him intently. The clock ticked on for five minutes, for ten, but the figure never altered its position. Nothing could be gathered from the features, which were masked, but the pose of the limbs indicated complete repose. It seemed that the dress was evidently doing its work; the only question was whether the moment had arrived to apprise the Marquis. After five minutes more of watching I determined to ascertain the condition of the Abbé, and accordingly coughed and made a rustling noise where I was. The figure did not move. Emboldened, I approached the open window, and called in low, distinct tones: "Monsieur Croix-Blanc! Monsieur Croix-Blanc!" The head made no effort to raise itself, the body moved slightly, but no response came. The time had evidently arrived. The prostrate figure before me had apparently reached the second, or speechless and helpless stage which the doctor had described to Madame, so it was clearly my duty to apprise the Marquis.

I regained the salons, and was not long in discovering a Mephistopheles promenading arm in arm with an odalisque. I passed in front of the pair without seeming to notice them—the sign previously agreed upon with the Marquis. On turning I perceived that they were moving in the direction of the boudoir, and, as soon as I could do so without attracting notice, I reentered the conservatories and resumed my old position behind the vase, the Marquis having bidden me to do so in order that I might be within call if wanted. On looking through the half-open window a strange scene met my gaze. There in the boudoir upon the sofa, just as I had left him, lay the masked Mephistopheles whom I knew to be the Abbé, and in front of him stood the odalisque—otherwise Madame la Marquise—leaning on the arm of another Mephistopheles whom she thought to be the Abbé, but who was in reality the Marquis.

"François," said the odalisque, looking up at her partner, "you can at least speak without reserve. You have not opened your lips to-night. Pray do not be so discourteous to Monsieur le Marquis as not even to bid him adieu. I am sure he would never forgive us if we were so far lacking in politeness."

The standing Mephistopheles remained immovable, betraying by neither speech nor action that he had heard the odalisque. Through the frame of the recumbent Mephistopheles there ran a shiver, which showed that he heard and appreciated the words of Madame. His hand was partially raised, but fell back powerless by his side, while a movement of the mask seemed to indicate an attempt at speech proved abortive.

"What can possibly be the matter with Monsieur le Marquis," continued the odalisque, banteringly, "that he does not rise to receive us? Perhaps a little too much wine—who knows? I think we had better loosen his mask and admit the air. It may help to revive him," and she made a movement toward the couch. Her Mephistopheles restrained her by compressing her engaged arm tightly with his own. She seemed surprised, but for a moment or two said nothing.

"Well, François," she at length remarked, "it seems useless to prolong this interview. If neither of you will say anything, what can I do? I will ring for Lisette, who will-summon Philippe. He will undress him and put him to bed, while we take our little drive; is it not so, mon cher?" and she made a step toward the bell.

Still the standing Mephistopheles, impassable and speechless as before, held her close bound by his side, and again did the recumbent Mephistopheles writhe impotently upon the couch. Now, for the first time, did the odalisque show signs of uneasiness.

"François," murmured she, "François, let us end this scene. A strange apprehension fills me. It may be carried too far. Let us desist before it is too late. Let us summon Philippe, and depart at once."

Still the rigid and sinister figure by her side said nothing and held her fast, and still did his masked counterpart quiver on the couch. I crouched, horror-stricken and breathless, trembling with unknown fear of what might happen.

All of a sudden, with the speed of light, the odalisque disengaged herself from the arm of her partner, and darting to the couch snatched the mask from the recumbent figure, disclosing the well-known features of the Abbé, which were passing through the most hideous contortions, and seemingly in the throes of death.

With a wild and prolonged shriek the odalisque threw up her arms and fell back motionless into the arms of the Mephistopheles. By this action she upset a wax candle from the candelabrum pendant from the ceiling, which falling against one of the light hangings of the boudoir instantly enveloped the whole chamber in a blaze. I sprang through the open window and assisted the Marquis to pull Madame through a side door into the corridor, in time to save her from the flames. As I leapt back toward the boudoir to rescue the Abbé I was intercepted by the Marquis, who pushed me forcibly back, saying:

"Fly at once. I will attend to that. Get Lisette and go."

I needed no second command, but flew up the staircase only to meet Lisette running down. She had on her traveling dress, and carried a small bag.

After this I have no distinct recollection of events. All is confused. I remember the shoutings of "Fire! Fire!" The frantic hurrying of a motley crowd through corridors and down staircases. Two carriages standing at a portico, into one of which four cloaked and hooded men bore the motionless form of an odalisque, and in the other of which Lisette and I were whirled away. I remember, as we drove off, the gallop of the fire-engines, the swish of water, the crackling of the flames, the falling of timbers, and the lurid glare of a burning building. I remember, confusedly, a trip by rail, the bustle of a departing steamship and having a stateroom assigned, and being addressed as Monsieur Dubois; but it was not till we were three days out from Havre that I regained the equilibrium of my senses.

When we reached New York I eagerly sought the Parisian papers. They recounted the burning of the mansion of the Marquis de B—during a bal masqué, and as Madame le Marquise was never seen or heard of again, and as the Abbé R. had mysteriously disappeared on the same night, and as the engagement of staterooms on board the Belgique was traced to him by an employee of the steamship company, and as these staterooms were proved to have been occupied by a lady and gentleman on the passage to America, popular opinion naturally decided that the Abbé had eloped with the Marquise. A single charred and unrecognizable corpse had been discovered in the ruins, supposed to be one of the servants. Whose corpse that was I leave you to judge for yourself. As regards the Marquise, my impression is that the Marquis had laid his plans to have her privately conveyed away and immured in a nunnery or madhouse, and that the carriage into which I saw borne the body of the odalisque was there for this purpose. I remember seeing the death of the Marquis recorded three years later.

As for myself, the money of the Marquis did me no good. I entered into business two or three times in New York and failed. Lisette died two years ago. I then came to California, and here I am. I see you are dozing, so you had better spread your blanket in that corner by the fire and turn in.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.