RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

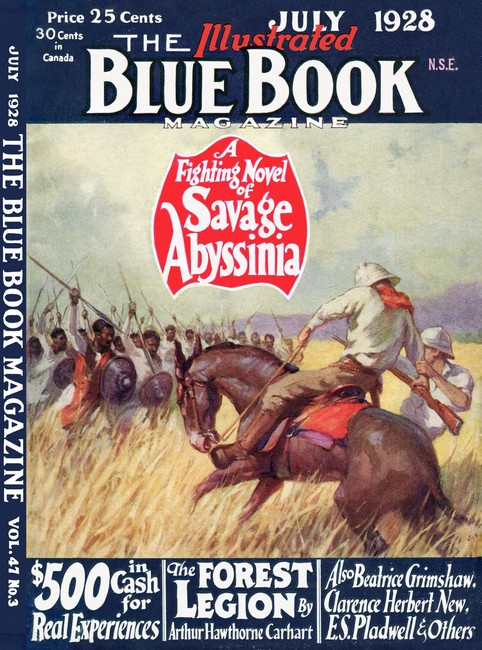

The Blue Book Magazine, July 1928,

with "The Madness of William Bull"

A blithe adventure of the moon-mad young gilded youth, Merlin O'Moore, his best girl, Blackberry Brown, his valet and his demon dog.

MR. MERLIN O'MOORE was in high spirits. He had been in such a really charming mood all day that even his glum, big-headed valet Fin MacBatt had no serious complaints to make about him at the moment, and indeed had gone so far as to say so to his especial crony Henri, the head-waiter at the Astoritz Hotel—when Henri had chanced to look in upon Mr. MacBatt for a chat, a cigarette and a little stimulant prior to girding himself up for his evening rush of business.

"He's been as sweet as a nut all day, Honroy," said the gloomy MacBatt. "And it's full-moon time, too, when he goes completely off his burner, as a rule. I suppose it's because him and little Blackberry Brown are off on a moonlight motor mouch tonight. Going down to our hat factory I think. We own a big hat factory down Reading way. And there's some sort of trouble going on there—strike or something."

"It is extremely oil-right to hear you expressing your satisfaction with him," said Henri pleasantly.

"Oh, don't you get any idea that I'm satisfied with him," the dour MacBatt hastened to say. "I'll own he's been as good as a doll today—but it's only a flash in the pan—if that. Let any little thing sting him, and he'll be on me like a leopard on a lamb. Still—it makes a nice change get a civil word now and then," concluded the blue-jawed valet, holding a glass of his master's remarkable Burgundy to the light. Henri nodded.

"That is a pretty one—the little Blackberry. H'm?" he said, referring to Merlin's delightful friend Miss Blackberry Brown, the famous white-black comedienne, whose coon flapper representatives at the Paliseum and the Colladium theaters of variety were said by critics to be the talk of the town that year.

"Yes—pretty enough. Not bad," said MacBatt. "But streaky-tempered—very streaky. Give you a quid at two o'clock and give you the bird at two-twenty.... Still, she aint bad, in some respects. Have you seen her turn?"

"Oh, but yes," said Henri enthusiastically. "It is very chic—very ravishing. She is like drinking champagne, is she not?"

"Not bad," agreed MacBatt. "I've known worse."

"Yes indeed," said Henri, emptying his glass in that deft French way of his, and rising. "I go now to execute my duties."

THE door-bell of the suite of rooms which Mr. O'Moore tenanted whirred as Henri rose, and MacBatt accompanied him. One of the hotel servants was occupying the mat, with a telegram in his hand, trying to look as though he deserved a tip.

"For Mr. O'Moore," he said.

"All right," replied MacBatt, and conveyed the telegram to his master.

Merlin, who was enjoying a half-hour with Swinburne and tobacco, prior to dinner, looked up at the blood-curdling growl with which it was the custom of his fearsome dogue de Bordeaux, Molossus, to greet every entry of MacBatt.

"Well, Fin, what's this?" inquired the millionaire affably.

"Wire, sir." MacBatt passed it on a salver, waiting while Merlin opened and read it. It was very short, but decidedly to the point:

"MEN VERY MUCH OUT OF HAND. GLAD HEAR YOU COMING. DELAY IN SETTLEMENT MAY BE SERIOUS."

It was signed by Forsythe, the general manager of the hat factory. Merlin put down Swinburne with a jolt, and rose. His affability went suddenly.

"Now, MacBatt, my man, get interested. Don't dawdle! Do something besides smoking my cigars and drinking my drinks. Send a telegram to Forsythe saying 'Coming at once;' see Henri and countermand dinner, and tell him to conspire swiftly with the chef to put up a traveling dinner-basket fit to invite a lady to share; ring up the garage and tell them to have the car—the fast two-seater—ready in twenty minutes; ring up Miss Brown—and let me know when you are through; give Molossus something to eat; fill my cigar-case; lay out a tweed suit, soft shirt and collar for me! Hurry up, my dear good man! Don't stand staring there! Don't you realize that a strike is a serious matter?"

With a muffled snarl the valet plunged heavily to the door, while Merlin, slipping off his dinner-jacket as he went, turned into his dressing-room.

FOR the ensuing twenty minutes activities of Mr. MacBatt, boiling with badly-suppressed fury, were reminiscent of an extremely spirited encounter between a youngish Irish terrier and an old, tough and worldly-wise London tomcat. He whirled; he dashed; he swore. Once Molossus chanced to get in his way, and he did what not one man in a thousand would have dared to do—that is, he hoofed the awe-inspiring dogue de Bordeaux halfway across the room before Molo quite realized what was what. It was like kicking a surly tiger; and if the flustered and fuming MacBatt had not instantly and bravely defended himself with a piano stool, until Merlin came out in his underclothing to quell the dogue, there would assuredly have been serious bloodshed.

Molossus chanced to get in the way, and MacBatt hoofed the

awe-inspiring dogue de Bordeaux halfway across the room.

"He deliberately got in my way, sir—did it a-purpose, sir, as I was hurrying across to tell you Miss Brown was at the phone waiting, sir!" lied the perspiring MacBatt, indicating the hanging telephone receiver, and hastening out to get the hamper from Henri, and put it in the already waiting car.

But all good things come to an end, and within five minutes of the specified time Merlin, duly arrayed for motoring, was leaving the suite, with Molossus slouching at his heels.

Merlin was pleased hastily to express his satisfaction with the valet's energetic handling of the mobilization; and MacBatt, shedding for a moment his sullenness, mentioned that he had a small favor to ask.

"Quickly, then—what is it?" said Merlin.

"Beg pardon, sir—I should like to ask you to let off one of the forewomen fairly light if she's mixed up in this—young woman named Wimple, sir. She's a well-meaning young woman, sir."

Merlin smiled.

"Ah, another of your numerous and everlasting amours, I suppose, Fin? Is she engaged to you? Man, you ought to be called Don Juan MacBatt! How do you do it? You wouldn't appeal to me if I were a lady!"

MacBatt blushed bluely.

"Oh, not engaged, sir. But we happened to go for a stroll when you were staying a few days near the works last month. She's a very nice girl—in some respects—and I thought I'd put in a word for her. She's engaged to one of the engine men there." Merlin nodded.

"All right—I will deal with her as she deserves."

Henri appeared at the head of the stairs, a bottle of wine in each hand.

"Pardon, sir—I overlooked the Moselle for Miss Brown."

"All right, Henri. Take it down, MacBatt."

"The dinner for tonight is countermanded, sir?" inquired Henri. "The chef wishes me to express his regret. He had excelled himself—even has he created for this evening two magnificent inspirations, the caneton à la Merlin O'Moore, and yet again, sir, the superb Pêches a la Coon—in honor of the charming Mademoiselle Blackberry!"

"I am very sorry, Henri, very. Please convey my compliments and thanks—and regrets—to Monsieur Casserole—" began Merlin hurriedly.

"Not at all, my dear boy, not at all!" broke in a refined voice close by.

THEY looked round to behold, advancing down the corridor, an old gentleman with a fine head of silvery hair, wearing an extremely racy silk hat with a broad well-curled brim, and a black, deep-caped Inverness overcoat—none other, indeed, than Merlin's good friend and financial protégé, Mr. Fitz-Percy, that evergreen and totally indestructible doyen of all the deadheads in London. He had evidently overheard Henri's plaint, and he advanced with outstretched hand.

"You issue forth once again to your moonlight revels, I perceive, Merlin mine— and doubtless you are impatient to be gone. Go then, with the blessing of one to whom your happiness and welfare is as important as his own. Leave the creations of the highly gifted Monsieur Casserole to one who will appreciate them not less than yourself and your little friend, my ward, Miss Blackberry Brown—I refer, needless to say, to myself, dear laddie. With your generous approval, I will attend to the dinner. Come then, dear boy, I will speed you with good wishes."

Gracefully he linked his arm in that of Mr. O'Moore and descended the wide stairs with him, merely pausing to remark over his shoulder to Henri that he would return to the dining-hall shortly.

A few moments later Merlin had gone— planning to pick up Miss Brown en route—and the Deadhead and MacBatt turned into the hotel again, the one to enjoy the dinner he had so fortunately inherited, the other to return to Merlin's suite and rest for a while from his labors.

It was perhaps an hour and a half later when the Deadhead, having steered himself with great skill through the dinner which Merlin, Henri and M. Casserole had so scientifically thought out in honor of Miss Brown, and now waiting for Henri to make his Turkish coffee and pour out his liqueur, perceived, making his way across the crowded dining-room, Mr. Fin MacBatt, bearing a telegram in his hand and quite obviously looking for him—Mr. Fitz-Percy.

Gracefully removing one of the best cigars that the Astoritz could provide him with, the ancient Deadhead smiled.

"Ah, MacBatt, my good fellow, what have we here?" he asked.

"A telegram for Mr. O'Moore, sir," replied the valet with a bleak grin. "He said nothing about opening any wires; and I don't know that I care for the responsibility of opening it. He's in a funny mood— streaky-tempered —full-moon time, Mr. Fitz-Percy."

The Deadhead nodded.

"Very right, Fin, my man—very proper," he said, reaching up for the telegram. "I will accept the responsibility of opening the wire on behalf of my young friend Mr. O'Moore. In these matters of delicacy one must always trust to one's instincts—and the experience gained during an extremely checkered career has taught me that my instincts are rarely, if ever, at fault in these matters."

He slipped a silver dessert knife under the flap, opened the envelope and withdrew the telegram. His refined, handsome old face grew grave as he read it. Then he looked up at MacBatt.

"I am very glad indeed that my instincts led me to open this wire," he said. "For it is a warning. Listen!" And he proceeded quietly to read aloud:

"ONE OF STRIKERS NAMED BIG BILL BULL LEFT HERE BY SIX-THIRTY TRAIN FOR LONDON STATING HIS INTENTION OF ASSAULTING YOU. STUPID MAN BUT TOOL OF DANGEROUS CHARACTERS. URGE YOU TAKE PRECAUTIONS. FORSYTHE."

"When—and what—is Forsythe, MacBatt?" inquired the Fitz-Percy.

"Manager at our hat factory," said the valet.

"Ah, yes." Fitz-Percy nodded thoughtfully. "Well, I think that we must arrange without delay to receive Mr. Bull. Do you, therefore, my good MacBatt, return to the citadel and await my coming. Do not worry, and do not be nervous—for I shall be with you almost immediately."

The dour MacBatt moved off.

"Worry?" he snarled under his breath. "Me worry about a half-witted ham from the hat factory that thinks he's only got to threaten with his mouth to frighten us!"

The old Deadhead, meantime, with that complete savoir-faire which invariably characterized his every action, whether it was "raising" a half-crown from a reluctant "parter" or eating a multi-millionaire's dinner, sent for M. Casserole, and in felicitous terms, complimented him upon the duckling à la Merlin O'Moore, expressed his admiration of the peaches à la Coon, insisted upon the gratified chef having a liqueur with him ("on" Merlin), and then, bestowing upon Henri a very worn shilling with the air of one who passes at least a sovereign, finished his coffee and accomplished a distinguished-looking exit, en route to Merlin's suite.

Handing his hat, stick and coat to MacBatt, he entered Merlin's den, inviting the valet to follow him in there to hold a council of war re the imminent advent of the ferocious Mr. Bull.

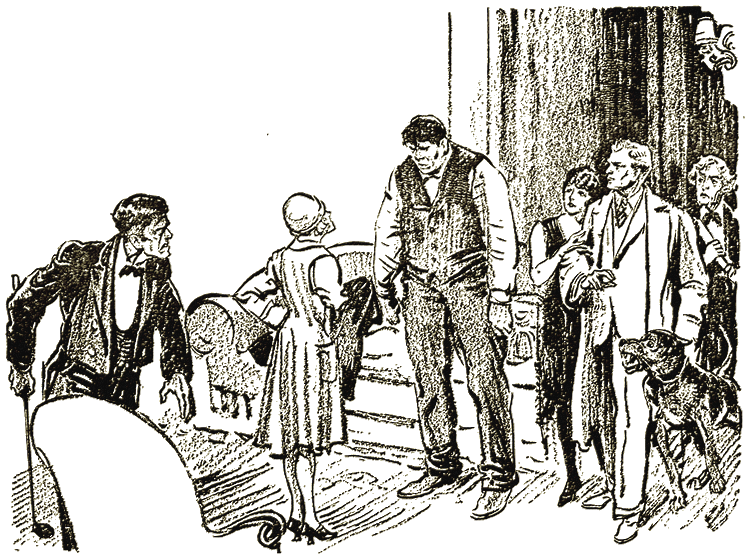

HARDLY had the Deadhead settled down in the most comfortable of the many comfortable chairs before a ring at the door invited MacBatt's attention.

He went out and opened the door rather skillfully with his left hand. In his right hand, which he kept a little behind him, he held ready for immediate use a lead-headed baffy—a "crank" invention long discarded by Merlin as being about twice as heavy as any golfer could ever need, but put aside by the far-sighted MacBatt in view of just such a contingency as this. A very large man, indeed, was standing at the door—a giant of a man, with a singularly small head, and a dull, heavy face, which was totally devoid of any signs of intelligence.

"Yes, what?" said MacBatt curtly.

"Does Mr. O'Moore live here?" asked the visitor heavily.

"Yes—why?" snapped the valet, his jaw protruding.

"And a man name of MacBatt?" continued the giant.

"That's me! What for?" answered MacBatt crisply and contemptuously. He saw that he had to do with a strong man, no doubt, but slow, he thought—painfully slow.

The man surveyed him a moment in silence; and then, without the least sign or warning, and with unexpected quickness, he slung an upper-cut to the valet's jaw. It was short but so remarkably stiff that it made MacBatt's teeth grate quite noisily, and lifted him clean off his feet to a sitting position upon the floor.

The man surveyed him a moment in silence; then with unex-

pected quickness, he slung an upper-cut to the valet's jaw.

The giant stared down at him dully, without the slightest change of expression.

"Take that, MacBatt, see?" he said slowly. "And the next time you try to cut me out with Bessie Wimple, I'll knock your neck off. Where's your boss? I'm Big Bill Bull, I am, and I want a word or two with him. I'll learn him to cheat the engine-men that works for him. Go on—get up and fetch him."

The temporary dizziness had departed from the badly-rattled MacBatt's brain now, and he got up, even as the engine-man requested him. But he did not go for Mr. O'Moore—instead he went for Mr. Bull, with the speed of an infuriated lynx and the howl of a semi-maniac in the rage of his life. The shaft of the baffy caught Mr. Bull on the iron-muscled arm which he had raised to protect his head, and snapped like a carrot, so that the lead head of the club flicked down fairly upon the beetling brow of the revengeful Bull. It did not fracture his skull, but it felled him like a buffalo struck by lightning.

The Fitz-Percy, roused by the sound of the combat, emerged just in time to prevent the maddened MacBatt from doing as the bull-moose is said to do, namely, jumping heavily upon the prostrate carcass of his fallen foe.

"Let us not totally obliterate the ruffian from off the face of the earth, MacBatt," said the Fitz-Percy. "Now that you have so deftly rendered him practically unconscious, it may be that, when he recovers, he will be in a milder mood, and more open to reason."

With a certain appearance of weariness, Mr. Bull rose to his feet, staggering slightly.

"Those who appeal to physical battle, my good man, must be prepared to abide by the result," said the Deadhead.

"Yes," said the giant dully, and suddenly swung a knotty fist to the near-by MacBatt's ear, refelling him.

The valet bounded to his feet again with a howl, but by this time many of the hotel servants had arrived, and they intervened.

The Fitz-Percy, thinking rapidly, decided that it would be well to lure Mr. Bull out of the hotel. He thought—rightly—that Merlin O'Moore would prefer that rather than the man's arrest, with subsequent police-court proceedings and the inevitable newspaper publicity.

"Come. Let us go forth and have some beer," he suggested cooingly, with his unerring instinct. "Beer—I know a grot where the beer is glorious. Come, then, Mr. Bull. Why fight—against heavy odds—when good British beer, nut-brown, comforting, zestful, served by deft-fingered houris in large cool cans or gleaming tankards, awaits us. Beer, Mr. Bull! Over it we can discuss matters, talk over your grievances against my young friend Mr. O'Moore, and await at our leisure his return. Forward to the beer!"

And thus crooning, the Deadhead skillfully led the bewildered Mr. Bull downstairs and beerward. He was a wonderful judge of men, the Deadhead.

The crowd dispersed, and save only for one stealthy figure which followed them— that of the vengeful MacBatt—the couple departed, alone, for a near-by hostelry.

LEAVING the diplomatic Fitz-Percy busily engaged in his noble endeavor to drown the ire of Mr. Bull in unlimited quantities of beer, and leaving the dour MacBatt watching for his chance to rebatter the engine-man, let us glance briefly at the activities of Merlin O'Moore and Miss Blackberry Brown.

Something like two hours after leaving London the couple reached their destination, after what, moon-slaves as they were, they decided was a very pleasant run, broken about midway by what they sincerely believed to be a delightful moonlight picnic, which clearly was entirely their own affair and need not be described in detail.

Late in the evening though it was, Merlin found that the hat factory, a big place on the outskirts of the town, was by no means deserted. On the contrary, it presented a pronouncedly busy aspect—some three hundred or so of the more dissatisfied workmen having decided, after grave and profound deliberation, that quite the simplest way to extract from their employer the increase of wages they desired would be to smash up about seventy-five per cent of the machinery in the place. Armed with the necessary tools for this operation, they advanced upon the factory in a body, reaching it a few moments before Merlin and Miss Brown drove up.

The manager, Forsythe, a shrewd, capable Scot, with an auger-shaped brain, a steel-lined will and rubber-reinforced soul, had collected many police beforehand and formed them as it were into a reception committee for the strikers.

He was haranguing them from a lofty place upon a pile of crates, as Merlin's car came into sight.

"Here," he said, "comes the boss. And if ye'll have the sense to be patient for ten minutes, ye'll discover that he'll settle it one way or the ither within ten minutes. If ye take my advice, ye'll wait. Ye have no fool to deal wi' now, d'ye ken! He'll treat ye fair, and if ye aren't all out of yer minds, ye'll abide by his decision."

The crowd stared with interest at the fair-haired, thin-featured young man, at his pretty lady friend, and especially at the glaring, furrow-faced, pale-eyed, growling beast that stood on the big dicky seat behind—Molossus, who was surveying the multitude with every symptom of displeasure. His teeth gleamed in the gaslight like steel.

Merlin leaned out, talking to Forsythe. He already knew the main points of the strike—for instance, that this was not a unanimous strike, but was largely confined to a section of men comprising perhaps a third of the hands. All the women-workers were well paid and satisfied, as well as many of the men—indeed it was well known that all O'Moore's workers, everywhere, were reasonably paid and well-housed. But a section of them had lost their heads a little, thanks to the activities of certain discontented individuals, and these comprised the strikers. Mostly they were engine-men, stokers, and what were lucidly described as "craters, twisters, catchers and tankers."

Briefly, then, all that Merlin had to deal with were the engine-men, the stokers, and their quaintly-named comrades.

"The bulk of the crowd, sir, are here for curiosity," said Forsythe. "I think ye should be firm. These men should be fired out—" He handed a list. "The rest of the strikers are too well paid as it is."

"I see. How much too much?" asked Merlin quietly. The Scot scribbled some figures upon a sheet from his notebook; and Merlin, who rightly had implicit faith in the judgment of his manager, stood up on the seat of the car and faced the crowd.

Doubtless, judging from the gentle appearance of Mr. O'Moore, they expected a soothing speech, in which he would yield to their demands.

They were disappointed—very.

"Men!" said Mr. O'Moore in a voice that, clear and distinct and with an odd ring if not of gayety, certainly of exhilaration in it, reached every person, striker and non-striker, there. "I understand that about a third of you are dissatisfied—mostly the engine-men, stokers, craters, twisters, catchers and tankers—I don't know what the last four are, but no doubt they are very interesting—and demand a raise."

"Yass! Yuss! Yes! That's it, boss—a good raise!" they bawled.

"And the remaining two-thirds are satisfied!"

"Yah! The dirty blacklegs!" howled the strikers.

"Very well," continued Merlin. "I have made inquiries of Mr. Forsythe—in whom I have perfect trust—and I am satisfied with the result of my inquiries. Now I want, my dear friends, to break an item of news t® you. This—I am not interested in hat factories—I don't care for hat factories—I don*t require any hat factories. I have so much money that I have never noticed whether this hat factory makes a profit or a loss. I don't know; and, my friends, I don't care. Personally I think this is an ugly hat factory—ugly and smelly—and I assure you that I would far rather see it leveled to the ground and turned into a really pretty golf-links. After all, what is the good of hats? Things that people put on heads which have already been provided by nature with a very reasonable thatch. Personally, I don't believe in hats or hat factories, and if there are a proportion of you who don't want to work in an ugly hat factory, I am sure I don't blame you. I wouldn't myself—should not think of it. Most uncomfortable notion. Still, we'll put that aside..... About this money. Let me say at once that the wages of the non-strikers remain as they are—they are satisfied, and I am sure I am. The wages of the strikers will be reduced ten per cent all round. Do you get that, my friends? Ten per cent, all round—and you will still be the best paid hat-factory artists in the world! Those who don't care about staying on can leave. It makes no difference at all to me. If they want to wreck the factory, they can—some other evening. It will not agitate me. I shall never miss it —in fact, I shall be glad to be rid of it."

HE smiled benignly upon the rather puzzled crowd. The police, Forsythe, and a few of the sub-managers and so forth were looking uneasy, but Merlin did not appear to notice it.

"Ten per cent cut until you behave yourselves better," he said, rubbing it in. "And you have my sympathy; but you will never get more of my money than I want to give you, until you learn to ask for it a little more civilly than you have on this occasion. And now, what are you going to do about it? Wreck the factory, or accept what I have offered you—namely, ten per cent cut all round? Turn it over in your minds."

He lifted a small bag from the seat and opened it.

"I ought, perhaps, to say that it is not entirely convenient to have the factory wrecked this evening." He began passing things from the bag to Forsythe and his supporters. "And I am not prepared to allow my friends or myself to be attacked to any extent. Consequently I have taken the precaution of arming us all for purposes of self-defense. These little instruments which you perceive in our hands are specimens of the unique talent of a fertile-minded gentleman named Browning—Mr. Browning. They are known as automatic pistols, and they fire much more swiftly and effectively than revolvers. They are very pretty little things, and with the best intentions in the world, I assure you, my good friends, that the first dozen or so of you who lead the assault will inevitably sample them."

He smiled again, as they muttered sourly among themselves, still a little puzzled.

Then with a sharpness that startled them, the millionaire's voice and whole manner changed extraordinarily.

"Why, you greedy blackguards," he said, with a cold and stabbing contempt. "Haven't you brains enough to understand that you are too well paid already, and that if I were a poor man, the factory would have been shut down years ago? If not, go to the women and learn from them how to be satisfied, and how to get out of the way of thinking that the law's right when it backs you up and wrong when it doesn't. And now, clear out, or I'll cut your wages ten per cent per minute from now onward!"

"You greedy blackguards," he said; "you

are too well paid already. Now, clear out!"

The police braced themselves for what they thought was coming. But nothing came.

The strikers knew, in their hearts, that they were in a big minority, and that their strike had been inspired not by honest need but by a desire to take advantage of an employer they fancied was "soft."

They had discovered now that he was unsoft. Oaths, yells and mutterings there were in plenty—but some one set the fashion of "clearing out," and it speedily became a craze. Everybody was doing it almost immediately. It was within a space of minutes, quite the thing to edge out of the range of vision of Mr. O'Moore and the needle-eyed Scot standing close by him.

The strike was settled, and within half an hour Merlin, Miss Brown and Molossus were speeding at a leisurely pace homeward, to where Messrs. MacBatt, Fitz-Percy and Bull were waiting to receive them.

MR. FITZ-PERCY, meantime, had made quite a number of mortifying discoveries, mostly relating to the quaint giant who called himself, with perfect truth, Big Bill Bull. And since it had been the Deadhead's praiseworthy plan to drug Mr. Bull into at least friendliness and forgetfulness of his mission with practically unlimited quantities of beer, not the least mortifying of his discoveries was the knowledge that William could absorb all that was set before him, apparently without the least effect upon his physical or his mental—if any— equilibrium. Further, after tankards terribly innumerable, it was borne in upon the Fitz-Percy that the lapping of many waves of beer upon the shore of Mr. Bull's consciousness, so far from soothing his anger and weakening his intent well-nigh to slaughter Mr. O'Moore, merely intensified and steeled it.

Not that Mr. Bull became quarrelsome—not at all. He became merely anatomical. Between beers he favored the Deadhead, himself laboring gallantly with a terrifical cargo of inferior beer blended with the magnificent wines he had taken at dinner, with a detailed account of how he purposed practically to tear Mr. O'Moore limb from limb. It was all very grisly indeed, and was not rendered less so by the occasional descents upon the pair of Mr. Fin MacBatt, who came into the place at regular intervals, a little more "lit up" each time, presumably to see that his gigantic prey did not escape him. The valet carried a large brassy with a dreadnought head.

Not one of the Fitz-Percy's many attempts to soften the fell determination of Big Bill had the least effect, and at about ten o'clock the Deadhead rather dizzily realized that Mr. Bull had not sufficient brain-power to accommodate his suggestions. Ideas, tact, persuasion, veiled threats, all slid off Mr. Bull's brain-case like water off a slab-roof. It was impenetrable by any art of even such an artist as Mr. Fitz-Percy.

So, recognizing that he had done his best, and failed, the Deadhead, still dimly conscious that Merlin would regard the calling in of the police as a sign of weakness, presently fell in with the suggestion of the still quiet but now perfectly cannibalistic Bull that they should have one final tankard and return to the hotel in the hope of finding that Mr. O'Moore was now at home.

"You are doubtless aware, my good friend, apart from Mr. O'Moore himself, MacBatt, his completely iron-clad valet, and Molossus his man-eater, you will have to deal with large numbers of huge porters, commissionaires,—er—bouncers and so forth, if you start anything at a place like the Astoritz!" he said.

Big Bill Bull grinned a slow grin, which, oddly enough, had something remotely winning about it.

"The more the merrier, mate," said he cheerfully. "I'll half kill them all."

"Very well," said the Deadhead, seeing that the man must be humored until he was rendered completely unconscious. "Let it be as you wish!"

They went up to Merlin's suite.

MACBATT met them at the door with the grin of an enraged death's-head.

"Come in," said the valet, keeping at comfortable brassy-length. "Mr. O'Moore has returned and is expecting you."

Big Bill Bull took off his coat and waistcoat and put them on a hall chair near him. Also he spat upon his hands.

"This way," said MacBatt, and steered them toward Merlin's favorite room.

"Mr. William Bull," he announced, and entered behind them.

Merlin, who was alone, and still in his motoring things, turned to them.

"Well, Mr. Bull, what can I do for you?" he asked. Molossus, standing near and, to judge by his exhibition of teeth, giving an admirable representation of a dogue in an ivory mask, seemed to be asking the same question.

"Do, mate!" said Mr. Bull. "You got to raise all wages down at the hat-factory by half, being as how you're a blood-sucking capitalist an' human shark!" he added, with a parrot-like mechanical simplicity that made it abundantly evident that he was merely repeating a lesson. "Or else I shall smash you and your house and furniture and everything else," he concluded, knotting his fists.

Molossus gaped imploringly at Merlin for permission to devour the big dunderhead.

But Merlin looked curiously at the man.

"Do you honestly believe you can do anything my man?" he asked. "You are big, but that is all, and I have no doubt that by touching this bell I can have half a dozen men as big as—or bigger than—you, here, in a few seconds." (The Astoritz is noted for its huge retainers.) "You have come to the wrong place—and—"

"And your name is Daniel in the lion's den, see?" hissed MacBatt bloodthirstily, entirely incapable of restraining himself.

Big Bill Bull scratched his head, remoistened his palms, and knotted his fists again.

"If you was earthquakes and lightning, and your little dog was lions and tigers, it wouldn't matter to me. I should put you through it, just the same," he said simply, and quite obviously meaning it.

Mr. Bull was plainly one of those men who honestly does not know what fear is—one of those unimaginative gents that, staring into a loaded revolver, cannot for the life of them believe there are bullets inside.

"Well, mates, look out!" he grunted, on the verge of attack. Merlin, who did not desire a scene, reached to the bell; MacBatt got a comfortable grip on his brassy; the Deadhead picked a solid, club-like slab of heavy carved ivory from the wall; and Molossus, instinctively realizing danger, began to foam at the jaws.

But none of these symptoms seemed to affect Mr. Bull in the least. He glanced round, marking the lay of the land—looking like a grizzly. But on the very edge of his rush he suddenly stiffened as the door opened and Blackberry Brown, who had been to her flat to change prior to supper with Merlin, entered, followed by a pale, rather pretty, bright-eyed diminutive girl.

"I met this child inquiring for you, Merlin, on my way up!" said Miss Brown. "Her name is Miss Bessie Wimple, and I think she is hunting for a gentleman named William Bull!"

"This is Mr. Bull," said Merlin politely.

AND then an amazing—or, so it seemed—thing befell.

Miss Wimple's sharp, bright eyes flickered round the room, at the men, at Molossus, who was still dribbling and rumbling within himself, and finally at Big Bill Bull. A quick, angry flush spread over her pale cheeks; her lips seemed to go thinner, and her eyes sparkled. She was still pretty, but there was a faint, far-off hint of the nagger and the shrew about her.

She moved swiftly to the mountainous Mr. Bull and stared at him. She seemed about as high as his lowest rib.

"William Bull," she said, with a crisp snap, "you have been misbehaving yourself again! Look at you! In this hotel in a gentleman's room without your coat on! Where's your manners? Just look at you! Glaring and staring there like a great ignorant ninny! Look at your great red hands! Aint you heartily ashamed of yourself, William Bull? The ignorance! Why don't you bow to the lady? Haven't you got any manners? Look at your great, dirty lumpering boots—on the gentleman's carpet and all!" She sniffed at him keenly.

"William Bull," she said, with a snap, "where's

your manners? Glaring like a great ignorant ninny."

"And you've been drinking beer! After your promise! What do you think people will think of you! Why didn't you shave yourself before you came to London? Ugh! Look at you. In your working shirt, too!" She drew breath. Evidently this was merely the preface.

But it had worked a miracle in that room, preface or not. Five seconds before, Mr. Bull had closely resembled a musth elephant. Now he resembled a punctured push-ball. He stared open-mouthed, goggle-eyed, at the little hornet buzzing about him. He looked dazedly at his "great red hands," at his "great lumpering boots;" he bobbed awkwardly to Blackberry Brown all as ordered. He blushed to the roots of his hair; he was utterly crestfallen.

Miss Wimple was tugging at a ring on her finger. Horror and desperation were made plain upon his face as he realized what she was doing.

"I can't bear bad-mannered men," she said angrily, "and I'll never lower myself to marry one!"

Mr. Bull gazed imploringly at Merlin, at the Deadhead, at MacBatt, even at Molossus. Evidently he loved the girl, and was in agony lest she meant what she said. All the fight was gone out of him.

The unfortunate man opened his mouth to speak and failed. Either his beer or his emotion choked him. He only succeeded in hiccoughing most alarmingly—and that, as Mr. MacBatt afterward said to "Honroy," put the lid on it. Like a tiny cyclone the girl whirled upon her gigantical fiancé and bitterly and contemptuously hustled him out of the room—as a twittering tomtit might (if it could) hustle a barnyard rooster off his favorite rubbish heap.

And the giant went like a lamb. They heard her voice, shrill and penetrating and extraordinarily copious, hounding the man into his coat, across the hall, through the door, down the stairway, and finally die away.

THE men stared at each other, with an odd, comradely look in their eyes.

"And that is the man who five minutes ago would have fought the entire male population of this hotel—and reveled in it!" said Merlin in a quiet, almost awed voice. The Fitz-Percy shook his head slowly and a little sadly.

"And that's the girl I took for a walk last month!" said MacBatt raptly.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.