RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage English beer advertisement

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage English beer advertisement

The Idler, July 1908, with the first part of "Easy Money"

"Easy Money," Grant Richards & Co., London, 1908

"Easy Money," Grant Richards & Co., London, 1908

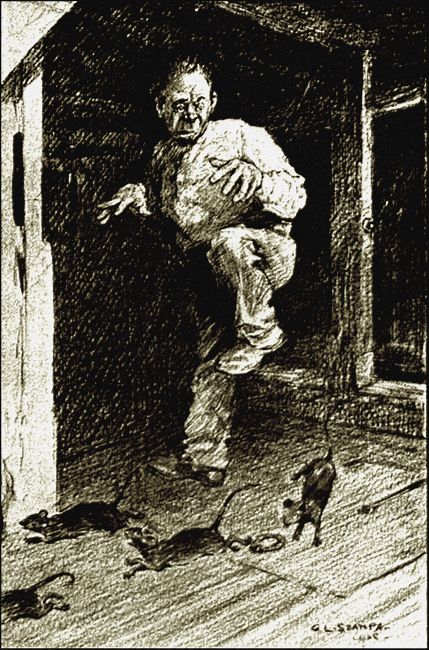

Headpiece from the serial in "The Idler"

MR. HENRY MITCH stopped on the wharf and gave one last, lingering look at the dirty little coaster that had been his home for the past three months. He had looked at her often enough before, from many points of view and in varying degrees of sobriety, but never before had he felt inclined to smile haughtily at her as he did now. He was leaving her for a permanency—discharged, and with no sort of testimonial. He despised her, the people on board her, the life they led, the sea she floated upon, and everything connected with her and with her element.

So he stood for a moment, a parrot cage dangling from his hand, and put his whole soul into his contemptuous smile. He was successful beyond his expectations, for the mate, a hard-looking, middle-aged man with a pale, cold eye, who was leaning over the side of the Gratitude smoking, suddenly stiffened and ceased to puff. He stared luridly at Mr. Mitch.

"You makin' that face at me?" he demanded so suddenly and harshly that Mr. Mitch jumped from sheer force of habit, jerking the bird cage.

"Chase yerself!" remarked the disturbed parrot surlily.

"Wot?" screamed the mate.

Mr. Mitch still stood and smiled, swinging the cage a trifle nervously.

"Lay aft the watch!" yelled the bird furiously, clinging to her perch for dear life, and straightway shot off such a volley of nautical insults, that a loafer who sat dozing on a bollard close by woke with a jump that nearly landed him over the edge. The mate crammed his pipe into his pocket and started for Mr. Mitch. And Mr. Mitch started for the town.

"Go and die and bury yourself!" shrieked the rocking parrot, as her owner vanished round a corner.

A few hundred yards up the street Mr. Mitch was stopped by a constable.

"Look 'ere, my lad, you must cover that bird up," he commanded.

"Oh, she's all right—only 'er fun. She's been disturbed and excited, that's all," said Mr. Mitch jauntily.

"She'll be disturbed and excited a good bit more in a minit if she don't use better language. Put a cloth over 'er."

"Talk sense," said Mr. Mitch. "'Ow can I cover 'er up if I ain't got no cloth?"

The official became offensive. "Look 'ere," he said, "I'm a-warnin' you for your own good. You cover 'er up and be quick about it, or else you'll come along with me."

A crowd began to gather, and the shabby-looking parrot seemed to get interested in them.

"'Ow can I cover 'er up when I ain't got nothin'?" expostulated Mr. Mitch, in a tense, angry whisper. The policeman took him by the arm professionally.

"Use your coat, mate," said a seedy-looking man with a fair, ragged moustache, and a remote suggestion of the army about him.

Mr. Mitch divested himself of that garment, baring to the public gaze a distinctly shady and thrice-patched shirt, and tied it round the cage by the sleeves.

"Eight bells, and a dam' dark night!" croaked the parrot dismally, and was silent.

"Now sling your 'ook," said the ruffled policeman, and Mr. Mitch obligingly slung it, muttering something about putting "an overcoat and a pair of britches on the bird!" The seedy man who had spoken kept him company.

"Nice bird," said the latter affably.

"Glad you think so," replied Mr. Mitch shortly.

"Good talker. Lucky I thought of the coat. But she overdo's it a bit, don't she? We shall 'ave to sell 'er, I s'pose." Mr. Mitch gasped.

"We shall 'ave to sell 'er, I s'pose."

"We! 'Oo're you?"

"Me? I'm Boler Mitey," said the stranger, with an explanatory air. Mr. Mitch grinned sourly.

"Well, Mr. Boler-bloomin'-Mitey, we ain't goin' to sell this 'ere parrot of mine."

Boler airily waved his hand.

"Oh, all right, I'm agreeable. Let's 'ave a drink." Mr. Mitch softened a little.

"'Oo with?" he said. "You?"

Boler smiled patiently.

"Do I look like a man who could ask another gentleman to 'ave a drink with me?" he demanded.

Mr. Mitch stared dully at him, noting, in a mechanical kind of way, his hopeless raiment, his sandal-like boots, his patches, but, above all, his extraordinary self-possession, and he wagged his head feebly.

"This beats all," he said. "This beats the lot. Come on."

They dived down an alley, seeking refreshment....

"It beats the lot—easy!" soliloquised the staggered Mitch as he entered a bar, Mr. Boler Mitey shambling after him.

"Mine's stout," said Boler, without any further invitation. "Very good stout you get 'ere—very good indeed. Let it be Guinness—I s'pose."

"Well, I don't s'pose—"

"S'pose beer," snapped Mr. Mitch, setting down the parrot cage with a thud. A muffled drowsy sort of snarl came from the bird, and Boler, avoiding any further discussion or supposition concerning his forthcoming refreshment, began to talk of the parrot.

"Fond of birds?" he inquired, with a jerk of his head at the cage.

"No!" said Mr. Mitch, "I ain't."

"For a friend, I s'pose?"

"No—it's for my missis."

Boler raised a brow over his tankard, a world of inquiry in his bland, blue eye. Mr. Mitch looked at his new acquaintance fixedly for some sixty seconds. He seemed like a man trying to make up his mind. From Boler he transferred his scrutiny to the barman, but that perspiring individual afforded him no inspiration. Presently he sighed, finished his beer, and grinned suddenly, all friendliness and cordiality.

"You'll do," he said, and patted Boler on the arm. "Come and set down in the sun in Queen's Park, and you and me'll 'ave a talk along with one another."

"All right," agreed Mr. Mitey, with the air of a man to whom time was no object. "But 'adn't we better make hay while the sun shines?" His thumb faintly indicated the tankards.

"Well, I don't mind."

They fortified themselves anew and strolled towards the park.

When they were comfortably seated in the sun, on a well-polished bench, Mr. Henry Mitch explained himself.

"I'll take it as I ain't far out when I ses that you're fair on your uppers," he began, and without waiting for Boler's languid assent, proceeded, with amazing freedom, to describe his own position.

"The fact is, I'm in a unforchnit dilemmer, Mitey, and that's the truth. Look 'ere—look at me. Don't anything strike you about me?"

Boler looked carefully, but could find nothing more striking about his companion than that he was the possessor of a cheerful eye.

"You got cheerful eyes," he said at last, "remarkable pleasant eyes. And you look poor but 'appy—more poorness than 'appiness. Why?"

Mr. Mitch leaned forward impressively.

"Well, appearances is agin me, then—that's all," he cried explosively. "W'y, I'm all twisted up in me inside with nervousness and doubt. You listen a minit. I don't mind tellin' you, because I've took a fancy to you, and I seen, back in the bar there, that you was the sort of man I was kind of hopin' would come along. You don't know what nervousness is—you ain't nervous of nobody, man or woman! You don't look like it—you don't seem like it—you—ain't! Are you?"

Boler shook his head. "I've 'ad very 'ard times," he said, "and I've kind of got out of being nervous. Why?"

"Well, it's like this 'ere. I'm a married man. It was a misonderstandin' more'n a marriadge—as I soon seen. I don't want to say nothin' agin my wife, but she was a bit too thick, Boler, old pal, and that's a fact. Talk was no word for it when she started. I could 'ave stood 'er talkin', but when it come to hittin' me about, well, I thought it over and give 'er best. I ain't the sort of man to hit a woman back, and, as a matter of fact, old man, I really believe that if I was that sort and I 'ad hit 'er back, she'd 'ave set about me and beat me, fair and square and no bloomin' favour. She's a great, strong woman with a onpleasant tongue. And I seen that, and five years ago I collected all the portable things of mine I could and slung me 'ook outer the villidge, and I ain't regretted it from that day to this. I've often been sorry I niver thought of it afore. There's always a job of some sort for a man on the road to turn his 'and to—and it's a easy life 'ceptin' for the rain and, mebbe, the dogs. Well, I've jest 'ad a few months workin' on a coastin' ship, and somehow, when we come into Southampton, I kind of felt as though I wouldn't mind callin' in at the old villidge once more for a day or two. She might 'ave calmed down in 'er ways a bit since I left, and if she 'ad, it seemed to me it would be sort of peaceful to settle down agin for a while.

"Then it struck me that she'd want some sort of compensation, and so I bought this bird with the intention of givin' it to 'er as a present. 'Might keep 'er quiet,' I ses to meself, and blued most of me money buyin' the bird off the cook. It was a dearish parrot. The cook 'as 'ad 'er for years. 'E said it reminded 'im of his wife, and 'e was very fond of the bird. 'E is a widower, the cook is. And 'ere I am, and I tell you, Boler, old man, I don't 'alf like it. I was oncertain from the moment I set foot on the wharf, and if I 'adn't seen you I expect I should 'ave sold the bird and not gone near the villidge agin. But back in the bar, it come to me like a flash that you was the man for me. 'He ain't afraid o' no nagger, he ain't!' thinks I. 'He's got a eye onto him that kinder makes a nagger feel small when she starts 'er jaw. Now, if I could get 'im to come along with me as my guest and friend she couldn't say much afore 'im, and she'd 'ave—well—he'd be sort of company like.'"...

There was a pause, during which Mr. Mitch eyed his companion with a flattering anxiety.

"Well, what d'ye say, old man? Why don't you come along? You ain't tied to no partickler spot any more'n me, I s'pose?"

Boler grinned. "Well, no, there ain't any more reason why I should be in this town any more than any other town. How far is it to this 'ere village?"

Mr. Mitch leaned forward with an oath expressive of delight.

"Only about twenty miles from 'ere—easy walkin'. We kin get there in two or three days, comf'rable. If we make it three days, that'll land us in Salisbury jest in time for the races. We might make a few shillin's there and stroll on quiet to Ringford." A doubtful look flitted over his face as he mentioned the village where his wife awaited him—where she had awaited him for the last five years.

"All right," said Boler, "I'll come. One way is as good as any other way as far as I'm concerned. But you won't need that parrot if I'm with you. Was she fond of parrots?"

Mr. Mitch thought for a moment or two.

"Well, not that I know of," he said finally. "She used to keep fowls."

Boler yawned and stood up.

"Oh, fowls is different. Fowls is business, parrots is pleasure. Two different things. Let's sell the parrot and 'ave a good blow-out. I know a place where they'd buy 'er, and a place where you can get the best blow-out in Southampton as well."

Mr. Mitch hesitated a moment. Then "All right," he said. "I could do with a steak and onions meself. Come on."

They solemnly shook hands, and stepped briskly out for the park exit.

The nearest bird-fancier offered them three shillings for the parrot. Mr. Mitch, distressed at the price, shook the cage violently and swore earnestly that he would wring the neck of, pluck the feathers from, clean, cook, and finally devour, the unfortunate bird before he insulted her, the cook from whom he purchased her, and himself, by accepting such a price.

Already wound up to a pitch of frantic hysteria by the events of the afternoon, the parrot waited until Mitch had replaced the cage on the counter, and then drew breath for the culminating protest. A hush fell upon that bird-shop, broken only by the lurid and sanguinary complaints of the parrot.

An elderly man of nautical appearance came softly from the back of the shop and hung upon the words of the bird. Now and again he nodded profoundly—as a man nods on hearing the name of an old acquaintance. A policeman, passing the door, halted on the pavement, and came in to arrest and generally restore the law and order. He remained to admire and to envy. Gradually the parrot slackened. She was panting a little about the breast. Once or twice she repeated herself. The elderly mariner whispered to himself a salt oath of the sea that she had forgotten. So she ran down and was silent, sliding two white shutters over her eyes. Then the elderly mariner turned to Mitch and, in an awestricken voice, said—

"Did you ever ship with Cap'n Bart Bennett on the Merrymaid?"

Mitch shook his head.

"Did you ever know the Cap'n?"

"Heard tell of 'im," said Mitch untruthfully.

"Well, his spirit is in that bird," said the elderly one, in a reverent whisper. "That was his own voice and his own words. I sailed with him as mate for ten years, and it's done my old heart good to kind of 'ear 'im once more. I'll give two pounds for that bird—I'd give two 'undred, only I ain't got it."

Mitch reached out a dingy hand, with the fingers bent upwards like fish-hooks.

"She's your'n!" he said, with repressed eagerness—"your'n!"

IT is necessary now to consider for a few moments the masterly but somewhat unfortunate burglar of whom an occasional glimpse will be caught during the progress of this story—Mr. Canary Wing. Some three days after the meeting of Messrs. Mitch and Mitey, Mr. Wing was sitting sullenly in the very best cell that the Salisbury police could accommodate him with. He considered himself an extremely ill-used man. And yet it was a thoroughly well-built cell. The walls were of good, expensive stone; the door was so constructed that it did not slam aimlessly to and fro; the apartment was not littered with an untidy collection of photographs, vases, and antimacassars, but was quite simply and healthily furnished, and contained nothing that could harbour dirt or dust; and there were practically no draughts. But, nevertheless, Canary Wing, who had slept in a hayloft the night before, considered that his luck was beyond any adequate condemnation.

"I'm 'ere," he said to himself thoughtfully; "I'm 'ere at last—and that's a fact. There's no gettin' out of it." He glanced dismally about him.

"They ain't played straight, these 'ere cops ain't.... Why, they niver do play straight!" he muttered, with a scornful stare at the cell door. "Shorely there wos enough sharps up on the race plain to satisfy 'em without comin' down on me. And yet they seemed absolutely glad to come in contact with me. Glad!" He snorted with disgust. "You'd have thought that that little job I done at 'Ampstead would 'ave been forgot by this time. Wot's the sense of bringin' up old things like that? Besides, 'alf the stuff wos jest common plated stuff.... 'Owever, I'm 'ere, and I'm a certain starter for the five year 'andicap, and that's another fact."

He thrust out his hands and looked them over, for lack of something better to do. His inspection afforded him no satisfaction nor comfort nor even interest. They were just ordinary large beef-coloured hands, in urgent need of very hot water. Canary sighed, and put them into his pockets out of sight.

"The world's agin me," he grumbled, watching a fly that was skating about the ceiling. "Even that blank little bluebottle's 'appier than wot I am. I ain't 'ad no chance—niver 'ave 'ad no chance. And I shall get five years certain. The world's agin me and, blimey, I'm agin the world. Why should I go to jail for a lot of lousy plated salt-cellars? Why should—Ello!"

That finely-constructed door swung open suddenly and a small, shabby man, without a collar and wearing a nautical nondescript of a hat a size too large for him, was slung into the cell, protesting violently. Then the door slammed to as suddenly as it was opened, and the shabby man knelt down and tried to look through the keyhole.

"For two pins—" he muttered. "For two pins, I'd—"

"Wot's the sense of lookin' through the keyhole?" growled Mr. Wing from his corner. "You ain't goin' to creep through it, I s'pose. And wot's the bloomin' good of arskin' for two pins. You can't do nothin'. You're 'ere—that's where you are—'ere, and that settles it."

The little man turned round and inspected Canary. The burglar saw that he looked hungry and like a man who had known hard times and yet kept his spirit through it. A man with a cheerful eye. He grinned, as he answered—

"No, I don't s'pose I can do anything much. Lumme! It's built, this 'ere cell is. Dunno as a man could want a better built cell than this one. It's the police I'm grumblin' about. Measly, time-servin', herrin'-gutted lot. Bleary-eyed, pimply lot these 'ere Salisbury police are."

"Wot they run you in for?" asked Mr. Wing.

"Oh, jest nothin'. Nothin' at all. They said I was a sharp. I 'appened to find two or three cards on the racecourse and was practisin' a kind of trick with a friend or two I'd made, and they come along and said I was a sharp. And run me in. 'Ow about you?"

"Burglary," said Mr. Wing, in an offhand way.

The little man looked thoughtful.

"What?" he asked respectfully.

"Little job up 'Ampstead way. Small job. Nothin' in it worth 'awn'," explained Canary loftily. "'Appened to crop up agin. Five year for me. Seven days for you. That's the difference. Eighteen hundred odd days for me—seven for you. Seems silly, don't it?"

"Funny 'ow things crops up," said the collar-less one, "when you least expects 'em." Mr. Wing looked sharply at the other, as though he suspected some hidden sarcasm.

"Yes," he said at last, "screamin' funny—I don't think. Wot's yer name?"

The little man straightened himself.

"Mitch—Henry Mitch," he said. "Pleased to meet you, Mister—Mister—Mister—" he paused.

"Mister Canary—bloomin'—Wing," said the burglar impressively. "Canary Wing of the 'Ammersmith jool case."

"Reely," said Mr. Mitch, looking with renewed interest at the burglar. "I thought the name wos familiar somehow. You 'ad five years for that. And now another five comin' on, you ses. W'y, it'll break up yer 'ealth. It's a long time, five year."

"Reely," said Mr. Mitch, looking with renewed interest at the burglar.

"Soon slips by," said Canary shortly. "Mebbe you done five year yerself a time or two."

The little man grinned.

"Well, no—niver more'n three months. I've only been in jail once, not countin' now. And that wos all a mistake. Fool of a policeman got all mixed up in 'is evidence, and said it all wrong, and the judge 'e give me three months and no chance of explainin'. You know."

Mr. Wing nodded cheerlessly.

"Soon shall," he said briefly, "if I didn't afore."

There was a dreary little silence, and Canary closed his eyes. A sparrow alighted on the window-sill outside, looked in, seemed to find the pair uninteresting, and flew away. Mitch shook his head.

"The bloomin' birds of the air," he said vaguely, with some idea that he was quoting something from somewhere. Mr. Wing opened his eyes.

"Wot birds?" he inquired.

"Oh, nothin', Only a sparrer."

"'Ow d'yer mean—only a sparrer?" asked the burglar, mystified.

"'E looked in 'ere and flew off, that's all."

"Well, so would you, wouldn't yer—if yer darn well could," said Canary sourly. He put his hand to his waistcoat reaching for his watch, and muttered to himself as he remembered that it was being taken care of for him. Mr. Mitch, who looked as though he was not in the habit of wearing a watch, or jewellery of any description, noted the involuntary movement. It seemed to give him an idea.

"You must 'ave earned a lot of money in yer time, Mr. Wing?" he suggested.

"Thousands," lied Canary.

"And, mebbe, you got a nice little lot put by for yer old age. Wish I 'ad," sighed Mitch. The burglar did not answer for a few minutes. But presently he said—

"I 'ad two shillings and a iron watch when I arrived, and that's all I got between me and the street. You'd 'ardly believe it. Quick come and quick go's the word with me. That's it— quick come and thunderin' quick go!"

Mr. Mitch grew thoughtful, and his face took a queer, wistful look. He was like a man pondering some secret pleasure.

"Wish I could save," he said at last. "I know how to save—but I niver gits anythin' to save. Money's saved by sendin' a bob now and then to a post-office savin's compartment and swearin' you won't touch it. Then when you gits old you lives on it—sets in the sun outside a public-'ouse and that."

"That's it," threw in the burglar sarcastically. "And 'aves a carridge and pair and a moto-car and servants—all through savin' odd bobs."

"Well, it's better than the 'Ouse, ain't it?"

Mr. Wing pondered.

"Oh, well, come to that, I got plenty saved up—in a sort of way. Can't get at it yet, but all the same it's there."

"Where?" demanded Mitch.

"There," returned Mr. Wing pointedly.

"What? Money?"

"As good as," said the burglar. "It's silver bars—dozens of 'em. A fortune. They wos hid very careful by a man wot dealt in silver orniments with me and some gentlemen friends of mine. He hid 'em jest in time, too, as you might say. For they copped 'im soon after, and I niver seen 'im but once afterwards. 'E wos exercisin' at Wormwood Scrubbs in my squad—'e wos very bad, coughin' and that, 'e said. Kep' 'im awake at nights. And 'e said 'e wos not likely to iver live to git out, and 'e told me that I could have 'alf the stuff wot 'e'd hid if I'd give 'alf to 'is mother w'en I found it. And 'e told me outer the corner of 'is mouth where it wos 'id. Next day I wos shifted to Portland, but within a week I 'eard from another convict that 'e wos dead. 'Is cough done for 'im. And only me knows where 'is silver is 'id, and—Gorlumme! 'ere I am with five years certain and mebbe more, waitin' all hot and ready." Canary brought his hand down on his thigh with an oath.

"S'welp me, that's gospel true—and I'm 'ere! And the silver's there!"

"Where?" asked Mr. Mitch excitedly.

"There! Same place. Where it wos a-fore!"

Mitch grinned lopsidedly. "Course. No offence—I forgot I asked afore," he muttered.

"Oh, all right," said Canary. "No 'arm done. I should 'ave arsked jest the same as wot you did."

Henry shuffled across to a bench.

"Remarkable nice to 'ave all that nice and 'andy and ready, so to say," he commented. Mr. Wing looked at him suspiciously.

"Wos yer a-tryin' to make fun o' me?" he demanded, lowering savagely. "Wos yer? If I thought yer wos a-makin' fun of me I'd wring yer neck out like a hen's," growled the burglar..

Mr. Mitch spread out his hands.

"Why you know I wasn't. S'posin' I wos your size and you wos my size, would you make fun of me? Be friendly, is what I ses. Honest and straight with your pals and friendly." Canary shut his eyes again, drowsily, and apparently soothed.

But after a while he stood up suddenly.

"Look 'ere, mate," he said. "I bin thinkin' about wot yer said about savin' and 'avin' somethin', so as to sit about outside a public-'ouse when yer past workin' and that, and it seems sensible. Now, s'posin' I puts it to yer—s'posin' I ses, 'Mate, I'm goin' to where the cows can't hook me for five years certain, and meantime I wants a partner to find out some silver bars wot is 'idden where nobody but me knows.' See? And s'posin' I ses, 'I'll tell yer pretty nigh where them silver bars is hid, and you go and git 'em and 'ave 'em ready when I comes out, and I'll give yer a quarter of 'em when you delivers 'em up,' wot'd yer say?"

"Halves," said Henry promptly.

"Ho! Would yer? Y' greedy little pig! Halves! W'y don't yer say the lot? W'y, it's fair givin' yer the money, and I'm surprised at meself for a-offerin' it to yer—and bloomin' well ashamed of meself, wot's more. A quarter, I said. Now?"

They argued and bargained in whispers for half-an-hour, and then Henry gracefully gave in.

"All right, then, Mr. Wing—quarter. Where shall I find the silver bars?"

"Don't yer 'urry on so fast. I want to warn yer a minit or two fust. And when I comes out, if I find you've slung yer 'ook with the lot, I shan't ever do nothin' else but hunt for yer. See? And I shall find yer—don't you make any error, Mitch. It's me, Canary Wing, a-givin' you the office; and old Canary he ain't no liar, neither. There's them as knows me wot'll tell yer that when I makes a plan, I'm a feller wot acts accordin'. And if you bunks, and if I finds yer—why, you say 'Good-bye, you pore fellow wot Canary caught!' to yerself. Mind that—and don't you fergit it. See wot I mean?"

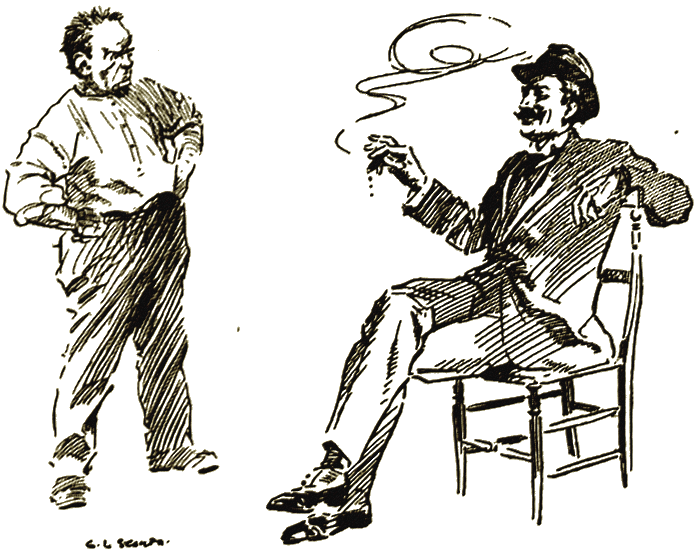

"It's me, Canary Wing, a-givin' you the office."

Mr. Mitch was no fool, and he saw what the burglar meant, without the assistance of any diagram but his face.

"All right, Mr. Wing, I onderstand—course I onderstand."

Canary made him swear strenuously that he would "deal square," and then, sinking his voice even lower, began to explain.

"Them silver bars is hid somewhere in a vil-lidge up Andover way in Ham'shire. It's a little quiet, old-fashioned place with only about three pubs, and this gentleman—'is name wos William Buckroyd—'id the silver—'avin' melted it down o' course. It don't matter much wot 'e wos there for—but wot 'e done there and where 'e done it. See wot I mean? I think 'e meant to take a little 'ouse there, but I dunno, and I don't care. Now, I'm goin' to give you 'is very words that day w'en we wos exercisn' in the Scrubbs yard, and where you 'ave to whisper outer the corner of yer mouth, 'cos of the warders. 'E ses.... 'And I knowed the cops wos after me like ferrets, and so I 'id the stuff.'

"'E sinks 'is voice 'ere, and wot 'e said wos either the Westley Inn or else the Wesleyan—chapel, I s'pose—e' wos rather clever at doin' the religious dodge, so I 'eard. Any'ow, you must decide for yerself, mate. You wants to keep a eye on a biggish 'ouse there wots called Westlynn, owned by a millionaire, a toughish customer, so I've 'eard—self-made man, same as me. Mebbe Buckroyd knowed this millionaire and stopped at 'is 'ouse—'e wos toffish w'en 'e liked. I dunno. But there it is—it's as clear as bloomin' crystial. Them bars is 'id under the floor of the 'Westley Inn,' or the Wesleyan' chapel, or the millionaire's 'ouse, 'Westlynn,' in the villidge of Ringford, near Andover, Ham'shire. I've made inquiries, Mitch, and it's one of them three places. Your job is to find it and wait in Ringford ontil I comes along. Now, are yer game?" Mr. Mitch's eyes shone.

"'Ow much is it—about?" he whispered fervently.

"Mebbe ten thousan' pounds worth!" said Canary Wing impressively. Mr. Mitch shoved out his hand.

"I'm your man!" he said. "Leave it to me. I knows Ringford—I been there. I got a wi—a cousin—livin' there."

The burglar scowled.

"Mind!" he said. "On the square, mate."

"On the square it is, Mister."

Canary nodded gloomily, and they thoughtfully awaited their respective fates at the hands of the law.

EARLY on the following afternoon the unaesthetic figure of Mr. Henry Mitch was to be observed toiling at a steady two miles an hour, up the dusty hill which led to Salisbury Workhouse. It was a very hot day, and Henry was bitterly wondering how many more dust-raising motors were likely to pass him and increase the midsummer thirst that thrived in his throat, when he saw a thin wreath of pale-blue smoke float tranquilly out of the hedge some few yards ahead of him.

He quickened his pace.

"Somebody's got a nice quiet place in outer the sun," he said to himself, and halted with a shuffle before a small opening that appeared in the hedge. The inmate had evidently been at some pains to screen this hawthorn bower from the public gaze, for he had carefully rearranged the long grass and twigs which his entry had disturbed—so that the only means of ingress apparent was a hole about a foot square. Through this Mr. Mitch inquiringly thrust his head. And there, comfortably curled up in the cool green cavern that he had diligently hacked and hollowed out, reposed Mr. Boler Mitey, studying a three day old copy of the Morning Post over a quiet pipe.

"Come in, old man," he said hospitably, "and shut the door behind you. You got off with a caution, I s'pose?"

"Without a stain on me character," announced Mitch sarcastically, as he crawled into the verdant apartment. "But this ain't the workhouse, you know, Boler," he continued reproachfully. "The arrangement we made if we got parted was to meet as soon as we could at the nearest workhouse. I might 'ave passed this 'ere little bury forty times."

"Oh, that wouldn't matter—I should 'ave called in at the 'ouse again to-night," grinned Boler.

Mr. Mitch nodded, recognising the wisdom of his companion's explanation. He filled his pipe and smoked for a time in silence.

At last he yawned, stretched, scratched himself, and "Listen to me," he said. "We're goin' to make our forchins, Boler. I've 'ad somethin' 'appen to me. It sounds too good to be true—but you never knows. What do you think of this?"

He told, with elaborate detail, the story of his arrangement with Canary Wing, and Boler Mitey listened in silence from the beginning to the final "And that's 'ow it stands at this minit."

But as Mitch finished he became aware that

Boler was white-faced and tense-eyed, and as near excitement as he had yet known him.

The excitement was infectious, it seemed, for Henry suddenly felt a queer thrill at his own heart. He leaned forward a little, peering at his fellow-tramp.

"W'y—w'y—" he stammered, "w'y, Boler, you don't mean as 'ow you thinks there's any-thin' in it. W'y—lumme! what do you know about it?"

Boler spoke in a fierce whisper.

"I've 'eard of Buckroyd—read about 'im in some paper somew'ere. He wos what they call a 'receiver,' and a bloomin' good receiver too. But they copped 'im at last, and give 'im five years. They got 'im all right"—Boler's hand closed over Mitch's knee—"but, be Gawd! they niver got anything what 'e'd 'received.' See? Oh, I kin remember it as clear as crystial. I read it in a paper same as I might 'ave read it's afternoon. They niver found it! For why? Becos' 'e buried it! That's why! And Buckroyd's dead and gone, and nobody but a convict and you and me knows w'ere the things is buried! And we'll go, Mitchy—you an' me—we'll go an' get—

"Come out of that!" interrupted a harsh voice. "Come on—out of it. You ought to be sentenced to death, you scoundrels! What do you mean by destroying hedges in that fashion? Confounded loafers!"

The treasure-seekers crawled dejectedly out of their arbour into the white-hot presence of a grey-moustached furious old man on horseback, obviously a retired officer, and probably a magistrate. Mr. Mitch wilted like a withered flower as he looked at him.

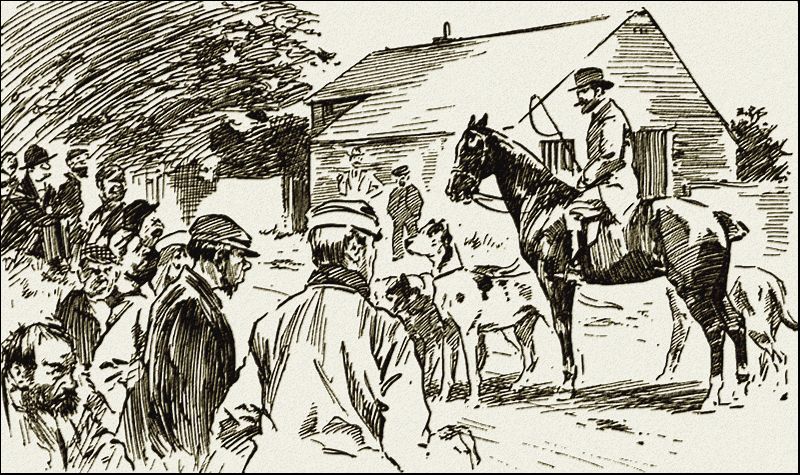

The treasure-seekers crawled dejectedly out

"Why, you're the vagabond I turned out of the town this morning! It was a mistake—I knew it was a mistake, as I watched you shamble out of the court. I should have sent you to jail. I should have given you six months hard labour, at least. A shocking miscarriage of justice! Something told me that I—what! You'd run away while I'm speaking! 'Tenshun!"

Something hard and imperious and compelling in the old man's voice anchored them where they stood, and the rider smiled a complacent, pleased little smile as he saw how strongly the old power of command remained with him.

A policeman was coming slowly along the road with a blue envelope in his hand—probably he was on an errand to the workhouse—and Messrs. Mitch and Mitey furtively divided their attention between the constable and the old officer who was holding them up. The latter may have been in a good temper, or the owner of the hedge may have been other than a friend of his, for he suddenly touched his horse and moved on.

"All right, men. Clear out. And congratulate each other on a stroke of luck!"

The policeman stopped as he came up.

"Wot's all this?" he said to the pardoned pair.

"What's all this? What's all this?" snapped Mr. Mitch irritably. "Can't a man 'ave a little chat with a friend without you shovin' your nose in? 'E was simply tellin' us the way to Andover."

"Oh, was he?" said the constable aggressively. "Did he tell you?"

"Course 'e told us—only ordinary politeness, ain't it?"

"You knows your way, then?" pursued the policeman.

"W'y, yes; 'aven't I jest told you we do?"

"Then move along on your way, or else I'll move ye!"

They moved along, as requested....

Not till twilight was upon them and the moon was rising huge as a silver barn; not till the nocturnal cockchafers were droning past the wayfarers, and an owl was hooting huskily from an adjoining wood; not till old landmarks rose thick and fast at every yard informing them that Ringford was close at hand, did the spirit of Henry Mitch fail and die out. Boler had been aware of an increasing nervousness about his comrade for some time past, but he had absently attributed it to excitement at ihe prospect of wealth in the immediate future. So that when Mr. Mitch suddenly uttered a curious sound, which might have been a groan or an oath, or probably both, Boler was sympathetic.

"Got a flyin' beedle in yer eye?" he said. "They do 'it 'ard, and no mistake."

Mr. Mitch looked up.

"Tain't a beedle, mate," he said. "It's a decision I've come to. It ain't no selfishness on behalf of the bloomin' silver you and me's after. She can 'ave 'er share and welcome, but she cant 'ave me." He stood, gesticulating.

"Boler, she was a terror to me, and don't you imadgine nothin' otherwise. She treated me bad, Boler. She 'ad a temper I didn't know of when I married 'er, and she never showed 'er teeth nor laid 'er ears back, so to say, ontil she 'ad me safe and sound. She sort of suddenly despised me, and, in them days, I wasn't sich a bad sort."

His voice rose, half hysterical. "And I've bin thinkin', and I ain't goin' back to 'er. She used to hit me about—knowin' I wouldn't hit 'er back. D'y' 'ear, Boler? I ain't goin' back. I knows what it is to be free, and—I—ain't —goin—back."

Boler patted him on the shoulder.

"Lumme, what you gittin' excited for, Mitchy? 'Oo's askin' you to go back? There ain't no call to go back. All our job is, is to git this 'ere silver and sling out of Ringford. This ain't no theatre with no long-lost 'usbands in it, and it ain't no penny novel, neither. It's business." He paused and thought. Mitchy watched him, as the castaway of the raft may watch the main truck of a steamer, and her smoke, on the horizon.

"Was you clean-shaved when you slipped it from Ringford?" Boler asked. Henry nodded.

"And you was pretty prosperous-lookin', mebbe? And decently dressed? And looked like a farmer sort of man?"

Again Mr. Mitch nodded, and the first faint gleam of a dawn of comprehension lit up his somewhat plain face.

"Yes, that's about right," he said.

"Well, you certainly ain't nothin' like what you must 'ave been in them days," cried Boler, with unflattering decision. "Nobody'll know you agin if you don't get shaved and pretends you're a absolute stranger to the place. 'Oo'll be thinkin' of Henry Mitch—

"Arthur 'Opley was my name in them days," said Mitch. "Nobody in the village knows anybody name of Mitch."

Boler shrugged his shoulders, with the air of a man who has settled a great controversy.

"All right, then—there y'are. Go as Mitch —be Mitch. 'Oo'll know? Nobody. We can find this silver and clear out one night and nobody the wiser and nobody the worse off, exceptin' 'ooever it is owns the place where we digs up the treasure. And 'e'll be better off, you might say—'e'll 'ave a nice hole dug for 'im for nothin', all nice and ready in case 'e wants to put somethin' into it."

He boisterously slapped Mr. Mitch on the shoulder, and doubtless, with the idea of paying his friend the compliment of addressing him in his own jargon, cried, "So heave ahead, my hearty, and the silver's as good as ready money. Come on."

Mr. Mitch, relieved and light-hearted again, stepped out buoyantly.

"It's a go, Boler," he declared enthusiastically. "When we gits our 'ands on the silver I'll leave a little share of my share be'ind for 'er and call it square."

A few lights twinkled yellowly ahead, and Henry pointed.

"There you be, Boler—there's Ringford!" he said, almost dramatically; and they ambled steadily on.

NEITHER of the loot hunters being professional criminals, they entered Ringford with a slightly furtive air and undecided gait. Mr. Mitch's progress indeed might have been called, in per-feet truth, an undisguised slink.

They passed down the long, straggling main—and only—street of the village in silence until there shouldered out of the shadows before them the square bulk of the Wesleyan chapel. Instinctively they stopped, staring at it. Their eyes moved simultaneously as the same thought struck them.

"Funny sort of place to bury silver in," they whispered to each other, and grinned in the dark.

"'Owever—" added Boler with a meaning sigh as they moved along.

"There ain't much silver—nor copper neither—goes in there as iver comes out, leastways, to the people what puts it in the dish on Sundays. She used to make me go there twice a Sunday—lumme!" said Mr. Mitch wanly.

Boler deftly humped his shoulders without taking his hands from his pockets.

"I kin mention some silver what's comin' out of it thunderin' soon—if it was ever there," he said in a hard voice.

Down the street a fan of cheerful yellow light stretched across the road from an open doorway, and a sound of laughter came up to the wayfarers.

"That's the Westley Inn," drooled Mr. Mitch, swallowing. Boler rattled a few coppers in his pocket.

"Good," said he. "Come on. We'll 'ave a look at it. Seems a nicesh place from 'ere."

They entered the inn, Mr. Mitch with an unnecessarily defiant air, and ordered beer and bread and cheese. The landlord—he was new to Henry—served them, favoured them with a searching look, tested the shilling Mr. Mitch put down, and, apparently only half-satisfied, thanked them perfunctorily and went on with the conversation with the other customers where he had left off.

The comrades bore their food to a corner and ate in silence, listening. Evidently the company was discussing some one of the village. .

"Yes," said a wizened man in the corner (the reader will be spared the real Hampshire dialect), "she's a terror! You can say one thing or you can say t'other thing, but when all's said, she's a 'oly terror!"

Every man in that stolid company nodded solemnly.

"I don't care 'oo 'ears me say so!" said the wizened man aggressively.

Mr. Mitch had pricked up his ears when he heard the tense summing-up of some woman unknown to which the shrunken one had given utterance.

A burly man, in a corner that was much too small for him, spoke with a remote resemblance to an ox chewing the cud.

"But she's worth two thousand pound! And two thousand pound is a lot o' money!"

"A powerful lot!" the murmur ran round the circle, led by the landlord—a strong-faced man, with the appearance of a prize-fighter.

"Hee! hee!" went an old, a very old, man who sat in a high-backed chair holding his hands out to the fireless grate from sheer force of habit. "I dangled of 'er on me knee! Forty-five year ago I dangled of 'er on me knee! Well, well, to think of Sarah 'Opley bein' left two thousand pound of money!"

Boler Mitey turned instinctively to Mr. Mitch. But he was too late. Judging by the manner in which he was choking and strangling, that individual had swallowed a newly-bitten mouthful very much "the wrong way." His "remarkable cheerful" eyes were bulging out of his head, and his face was of a deep terra-cotta tint.

"'Ear that?" breathed Boler, like a drowning man clutching at wet sand.

Mitch nodded lamentably.

"Gorlumme!" he said faintly, and coughed, and coughed, and coughed.

Boler hastily ordered another pot of ale, to distract as much as lay in his power the attention that the breathless Mitch was drawing upon them. Gradually the coughing subsided, and the comrades went silently on with their feeding, their ears spread, as it were like mainsails, to catch the littlest remark concerning the amazing inheritance of Sarah Hopley. For Sarah was Arthur Hopley's, that is, Mr. Henry Mitch's, wife.

"W'y, she wos once a liddle bit of a thing "—this from the very old man, in accents of the utmost surprise—"a liddle bit of a slip of a thing. And now she's worth two thousan' poun'—a liddle bit of a thing like she wos."

"Wonder wot pore Arthur would say if 'e knowed about it," said the burly man.

"Arthur 'Opley wot deserted 'er? Oh,'e'd be 'ome agin as quick as the next train 'ud carry 'im from wherever 'e wos when 'e 'eard the news!" said the wizened one sourly—he who had spoken first after the silver-seekers' entry.

"No, 'e wouldn't, neither!"

"No, 'e wouldn't, neither!"

Even Boler found it difficult to recognise the angry voice that lashed out across the bar. Everybody turned and stared helplessly at Mr. Mitch, who had spoken.

"No, 'e wouldn't 'ave took no train back fer no lousy two thousand pound! 'E was not that sort of man, not Arthur 'Opley wasn't," said Henry savagely.

Nobody seemed inclined to answer. They only stared more helplessly than ever, until at last the hard-faced landlord said drily, "Why not?"

Henry hesitated for a second only.

"Why not! 'Cos 'e's dead! There ain't no Arthur 'Opley now—'e's dead! That's why not! 'E's drowned and under water, that's where 'e is. 'E was a mate of mine, and 'e went overboard in S'int George's Channel, and there 'e lies to this day. 'Im! 'E! 'E wouldn't come back spongin' on no woman, 'e wouldn't, not if 'e was alive—" Here the rocket-like flight of fancy failed him, and he ended haltingly, "'E was content with wot 'e earned, and 'e was all right!"

The burly man in the corner growled in a friendly fashion.

"Right—that's right. 'Opley wos all right if she 'ad let 'im alone. I can't seem to see 'im spongin' on no woman, some'ow. And so 'e's drowned is 'e, Mister? 'Ow wos 'e drowned?"

"Fell overboard," said Mr. Mitch, suddenly cautious. "We flung 'im a life-belt, but we was too late. 'E'd sunk for the last time. We was all very much surprised at 'im. It was rainin' at the time, I kin mind." Henry was growing warm and nervous, and something in his eye warned Boler that the little man was getting out of his depth. So the self-possessed and blasť Mitey rose, with a vague apology to the company.

"Sorry, gentlemen—me and my mate must be movin'. 'Ope to see you some other time." He slouched to the door, Mr. Mitch at his heels.

"Good-night, gentlemen!"

Before the company had time to protest or to offer bribes in the shape of further refreshment, another customer arrived. This was a keen-eyed, lean-faced youngish man, wearing breeches and gaiters. He looked intently at Mr. Mitch as he entered—or was it Mitch's imagination? He seemed to be popular, to judge by the chorus of "'D evenin's" which greeted him, and under cover of which the silver-seekers vanished unostentatiously round the door-post.

"That's one of the sharpest chaps in Ring-ford," whispered Mitch feebly, as they moved off down the street. He passed the end of his coat-sleeve across his perspiring brow. "Name o' Riley—Perry Riley—kind of a hoss-dealer. Lumme, Boler, I thought 'e knew me!"

"Well, as long as 'e don't know what we're after, it don't much matter," said Mr. Mitey. "You're dead! I don't s'pose 'e did, though. Where we goin' to sleep to-night? You ought to know a good barn somewhere."

Henry grinned, cheerful enough now that he was relieved of the necessity of swiftly inventing facts concerning his own recent unfortunate death.

"I know the very place," he replied gaily. "Come along with me."

They turned off into a dark lane, half-avenued with big, rocking elms, and stepped out briskly, neither noticing a figure that followed them on tiptoe some distance behind. They proceeded in silence for about five hundred yards, and then, as they turned slightly to the right, clearing the corner of a plantation of young firs, there swung into sight a huge house that was built upon a little hill a furlong away from the road. It blazed with lights, and might have been a hydropathic establishment or a big golfing hotel at the hour when people are dressing for dinner.

"That's Westlynn!" said Mr. Mitch, at Boler's elbow. "What an 'ouse!" with an awed chuckle. "If it is buried there—"

A hound began to bay deeply somewhere at the back of the big house, and he was joined by others. It came down to the ragged pair as they stood watching, and it sounded ominous and menacing, and hinted of peril and dangerous things.

"Thems 'is 'ounds. Great Dane—'arlequin Great Danes, they calls 'em. I'd almost forgot 'em. 'E keeps a lot of 'ounds.... 'Ark to 'em—Lorlumme, Boler, 'ark to 'em!" twittered Mitch. "If it is buried there—"

Boler looked over his shoulder, his hands in his pockets, as ever.

"If it was buried in blazes, I'd 'ave a cut at it," he said roughly, for the deep notes of the hounds had vibrated his heart-strings. And, indeed, the man must not be troubled with any sort of nerves who can stand with an ill conscience in eerie moonlight under ghostly whispering trees, and listen unthrilled to a chorus of great, powerful, deep-chested dogs. Particularly if those same dogs are guarding a place upon which he has designs.

Mitch thought of the man who had hinted that Arthur Hopley would have sponged upon his wife, and his hand closed upon Boler's arm.

"Me, too!" he said, in a starved whisper, his face showing white. "Me, too!"

They moved on again, and presently they came to a coach drive, shut in on both sides by thick, dark rhododendron hedges, and barred by a huge iron gate, expensively wrought in a curious pattern. Here they stopped again, staring up the gravelled moonlit drive, the clamour of the disturbed hounds in their ears.

"S'posin' we go up it a liddle way," suggested Boler, "and 'ave a look round!"

Mr. Mitch did not hesitate.

"If it'll do any good. Seems to me—"

He stopped swiftly, for a man came leisurely round a corner of the drive smoking a cigar. At his heels padded two huge, loose-limbed dogs. Mitch made as though to move on down the lane, but his comrade stopped him with a whisper.

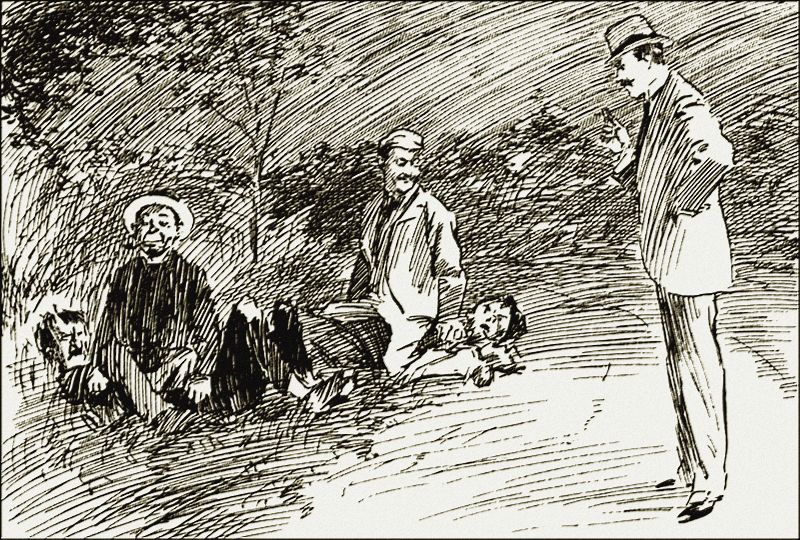

A man came leisurely round a corner of the drive.

"Don't 'urry," he said, "or the dogs'll start for us, mebbe!"

They waited while the man approached.

He touched a button in one of the big gate pillars and the gates swung silently back, evidently electrically manipulated.

He looked keenly at the two white-faced, ill-fed watchers and stopped, rolling his cigar into a corner of his mouth, and his dappled attendants came softly up to the two, sniffing at them.

"What are you doing here, eh?" said the man sharply. His voice was harsh and brutal, and went badly with the superbly cut dress suit and the hot flame of a magnificent diamond in his shirt front.

Mr. Mitch spread out his hands in a nervous, deprecatory gesture.

"Nothin', sir," he said hastily.

Boler's eyes glittered a little.

"We was wonderin' whether it was any good our goin' up to the 'ouse and askin' for some-thin' worth 'avin'," he said deliberately. "Not tuppence—but five shillin's. Somethin' a man can feel it's worth while takin' out of 'is pocket and lookin' at."

The man—he was ruggedly handsome, in the bearded style, and looked tremendously powerful—laughed drily.

"You've got a devil of a cheek," he said. "You'd be afraid of the dogs."

Boler shook his head stubbornly.

"A 'ungry man is more afraid of 'is own 'unger than any other man's dogs," said he. The man laughed again, and spoke to one of the dogs.

"Look at him, Jane."

Jane, a wonderful harlequin Great Dane bitch, stiffened before Boler, and looked steadily up into his eyes. But Boler stared back not less steadily. The haggard beast growled in her throat—it vibrated queerly through the moonlight—and Boler whitened a little. But he stood his ground, and Mr. Mitch looked on nervously. Then the man—he was Burton Crail, the millionaire of whom Canary Wing had spoken—laughed for the third time.

"You've got nerve, tramp," he said, "or else you're crazy. Man, she would tear you if I whispered one word! Hungry, are you? Here, then. Give your pal what you reckon he's worth. And, say, don't let me catch you hanging round here again. Understand what I mean?"

He handed a half-sovereign, with no grace nor kindliness nor sympathy, and strolled away. The silver-seekers looked after him.

"That's the 'ardest man I've iver seen in me life," said Boler. "That's the sort of man that niver dies a natural death. Mitchy, he's dangerous—even 'is play is dangerous, and 'Eaven help any man 'e wants to 'arm. Mate, I'm afraid of 'im, and that's the truth, and I ain't ashamed of it. Any man might be afraid of 'im and not be ashamed. I done that becos I thought 'e might send us along to the servants' 'all and 'ave some grub. I thought we might 'ave a glimpse roun'. But 'e ain't that sort—'e don't think for people. 'E's the sort that ses, ''Ere's 'alf-a-quid; go and perish for all I care!'"

"But s'posin' the silver's buried in 'is 'ouse?" said Mitch joylessly. "What then?"

"Oh, then we've got to get it out," answered Boler, and they shambled on down the lane.

A quarter of an hour later they were sprawling comfortably in the straw which half-filled the barn of one George Collins, farmer, who probably would have fainted could he have seen the airy carelessness with which they puffed steadily at their pipes.

"And now," said Boler, yawning comfortably, "and now let's map things out."

Then a figure—slimly built, wearing riding-breeches—spoke drily from where he stood in the doorway, black against the moonlight in the empty cattle yard outside.

"Good evening, Arthur—Arthur Hopley! How are you? Glad to see you're back again—safe and sound. You haven't forgotten me, surely; you haven't forgotten Perry Riley!"

"What did I say?" groaned Mr. Mitch. "What did I tell you?"

PERRY advanced easily into the barn, extending his hand to Mr. Mitch with the utmost friendliness. The long-lost one glanced furtively at their visitor and suffered his own nerveless hand to be shaken at some length.

"Well, this is a very pleasant surprise, Arthur!" said Perry, in a pleased voice. "Why, they told me back at the Westley Inn that you were dead, been drowned or something or other. I'd hardly got inside before they began to tell me about it. But I thought to myself, 'Arthur Hopley drowned in St. George's Channel! Not he. If that wasn't Arthur himself that I saw going out with a friend of his, you can call me no judge of a horse I' And so I followed you, and here you are. Well, how are you, old man? Only the other day I was talking to your poor wife about you."

Mitch moved his hands feebly.

"'Ow is she?" he said, without interest.

"Oh, pretty well, pretty well. She pined a little bit when you went away, but she bore up all right otherwise. She seemed as much annoyed about you going as anything else. But she'll settle down now, all right. You'll come as a sort of surprise-packet to her, I expect."

There was a strained silence for a few moments. Then Mr. Mitch pulled himself together.

"Well, Perry," he said, "I don't know as I want to surprise 'er, to tell the truth. She wasn't never very fond of bein' surprised."

"Oh, I'll break it gently to her, old man," volunteered Mr. Riley, taking a seat on a bundle of straw. "You leave it to me; I'll see that it doesn't come to her as a shock."

Mitch grinned wryly.

"It's kind of you, Perry, to be so thoughtful for me, and I ain't the man to fergit it. But this is a delekit family sort of matter, and I'd sooner 'tend to it in me own fashion."

"You don't want me to tell her, then?" Mr. Riley seemed surprised.

"No, I don't, and that's a fact!"

"Oh, all right. As you like, Arthur." There was another silence.

Perry it was who broke it this time.

"She's just come into two thousand pound!" he said, casually. But Mr. Mitch was prepared for it, and exhibited no astonishment.

"Oh, 'as she?" he commented indifferently. "Lot o' money."

"What!" Perry was astonished now.

"Lot o' money." Mitchy actually yawned. The horse-dealer looked at Mitch and then at Boler—who was apparently too uninterested to make a comment—then at the moonlit yard outside, and finally turned his amazed stare back to Mitch.

"Well, this takes it!" he said, almost reverently. "I tell you she—your missis—has had two thousand pound left her—quids—jimmy o' goblins—thick 'uns! Two thousand!"

He waited for it to soak in.

"Oh," said Mr. Mitch, with superb carelessness; "got a match?" Perry Riley handed over his matches dully.

"Haven't you got anything better to say than 'Oh, got a match?' It's a fortune," he cried.

"She's welcome to it, for all I care. Made much difference to 'er? Swelled 'er 'ead up at all?"

"Swelled her head up!" said Mr. Riley, with sudden bitterness. "Well, if it goes on swelling much more, it'll want two parishes the size of Ringford to hold it And she was bad enough before."

Mr. Mitch looked curiously at Perry.

"Well, if she's got a position to keep up," he said vaguely. Then he grinned with heart-winning frankness.

"Lumme, Perry, she must be a terror. And you wants to tell 'er I'm come back. Well, look 'ere, I don't want 'er to know. She thinks I'm dead—or she soon will—and she's very well provided for. Let me be dead. On'y you knows I ain't, and I never done you no 'arm. I don't want 'er two thousand—none of it—not a ha'p'ny. I shall only be in the villidge a liddle while and then I shall sling off out of it, and nobody'll be any the wiser. There's no call to tell 'er; it wouldn't be no favour to 'er to go and say, 'Lorlumme, wot d'yer think's 'appened. Arthur's come back with a man name o' Mitey, and there they be, the pair of 'em, a-roostin' in the straw up in old Collins's barn!' It wouldn't do you no good, and it'd do me 'arm."

"I don't know, though," demurred Mr. Riley. "I don't know so much about that. I've got special reasons for doing Mrs. Hopley a good turn. Special and private." He glanced at Boler.

"Oh, he's my partner. Don't mind about 'im," said Mitch feverishly. "What's yer reasons? I thought you wos after somethin' when you come in 'ere. What you after, now?"

"Your niece—Katie," said Perry coolly. Mr. Mitch opened his eyes.

"What! a liddle, long-legged bit of a girl like 'er—'air down 'er back?"

The horse-dealer frowned.

"You've been away from home for a few years, old man, and it hasn't improved your way of speaking. Katie is a good bit older than when you saw her last, and, you take it from me, she's grown into the smartest and best-looking girl in Ringford! Yes, your niece.

"Arthur," went on Mr. Riley with slightly fatuous solemnity, "you mark my words—the man who gets her gets the best girl in the world bar none. As dainty and neat and haughty—where on earth she got her ways and manners I can't think."

"She got 'em from them as 'ad charge of 'er bringin' up, I s'pose," said Mitch stiffly.

"Well, wherever she got 'em, I want to marry her."

"Why don't you, then?" asked Mitch.

"Why? Your missus won't let her, that's why!" said Perry impatiently. "And it seems to me that if I could restore her husband to her she might come round." Mitchy jumped up and put his hand on Perry's arm.

"Don't you go and do nothin' of the sort, Perry. You'll ruin your chances if you do that!" he said earnestly.

"How?" queried the puzzled Perry.

"I dunno jest exactly how. It's a kind of instinct I've got," explained Mitch weakly. "I'm sure of it."

His love must have dulled his natural sharpness, for Mr. Riley allowed the explanation to pass. A man in love you may lead on a cobweb, if you make him nervous about his chances.

"Why do Sarah object to ye, Perry?" continued Mitch.

"Oh, I don't know. Because I was fool enough to stick up for you a year or two ago when she was running you down. I got in an answer or two that made her look small. She'd been coming it rather strong about you, and it didn't seem quite square to you somehow. It was at a party. And she hates the sight of me."

"'Ow about Katie?"

"Oh, well, she doesn't," said Mr. Riley, a shade self-consciously.

"Well, I dunno. What'd you do, Boler?"

Boler desisted from picking his teeth with a straw, and applied one word to the situation—one word only.

"Slope!" said Boler, and selected another straw.

"Yes, that's it. The very idea!" Mr. Mitch already saw his only danger of being reclaimed safely out of the way. "Slope with 'er!" But Mr. Riley had other views.

"Slope with 'er!"

"Not me," he declared. "If I'm going to marry her, I'll marry her in the face of all Ringford and forty Sarah Hopleys. However, it's late. I'm off. I'll keep quiet about you until I see you again, Arthur—

"'Enery, please—'Enery Mitch."

"Henry, then. Well, good-night!"

At the barn door he paused.

"What the dickens made you come back again if you didn't want to be recognised?" he asked, puzzled.

"Oh, I dunno; sort of cravin' to see the old place agin," said Mr. Mitch carelessly, from out of the shadows.

Ten minutes later there was no sound in the barn but the strenuous sound of the loot hunters' slumbers.

THE early dawn discovered Mr. Mitch laboriously cutting his corns.

"Lor, 'ow the road brings 'em out!" he said to Boler Mitey, who was rummaging through a bundle. "It's a beautiful mornin'. We'd better be eatin' whatever there is to eat and 'avin' a look round. I 'ope young Perry Riley's to be trusted."

Boler produced a greyish slab of bread, the butt end of a pound of cheese, and a brace of Spanish onions from the sack-like carry-all—their only baggage—and they breakfasted. Then they evacuated the barn, and sat on a bank close by airing themselves in the sun and seeking further nourishment from their pipes.

"Well," said Boler, after a dreamy pause, "'ere's w'ere we begins, I s'pose. Now, fust of all, what's the arrangement—'alves, I s'pose?"

"Thirds! A third for you, a third for me, and a third for Canary Wing. Darn me, it sounds like poetry!" said Mr. Mitch gaily. "It's safer. 'E's a terror, reely. 'E's next door to committin' murder. 'E's served so long in jail it don't much matter to 'im whether 'e's 'ung or not unless 'e can make sure of a good and easy time when 'e comes out."

Boler nodded. "All right, thirds. We'll have a agreement to it bimeby. We'll draw it up down at the inn later on. Now, this silver's buried in one out of three places, them bein' the Westley Inn, the Wesleyan chapel, and that 'ard man Crail's place, Westlynn. Wot's your idee, Mitchy? I got mine, but let's 'ear yours fust, as you knows the villidge."

Mitch screwed up his eyes.

"Well, I reckon we oughter work 'em one be one, keepin' a eye on t'others at the same time," he said lucidly. "And it seems to me the best place to start on is the pub."

"That sounds all right, but 'ow are we goin' to live while we're doin' it?" asked Boler. "Now, my idee's this. One of us ought to 'ang about the pub 'elpin' sort of casual in the stable-yard and that—lendin' a 'and with the 'arness-cleanin' and muckin' out the hoss boxes. You gits into their confidence be doin' that, and if you're 'andy, sooner or later you gets a job reglar. Y'see, nine times out of ten they wants 'elp when the brewer comes round for empties—gettin' 'em out of the cellar and that, and that'll give one of us a rare chance of 'avin' a good look round every now and then. If the silver's buried in that pub it's pretty sure to be buried down in the cellar. Well, one of us got to do that ontil somethin' better crops up. And it seems to me that about the best thing for t'other to do, is to try and get a job up at Westlynn, 'elpin' in the kennels or anywhere for a start. Then the dogs'll git used to 'im and 'e might be able to 'ave a look 'ow the land lays up there too. That leaves us the chapel to 'tend to and that's the job I don't much fancy. Why not, thinks you? Well, one of us got to be converted—be religious and temp'rance and all that. I ain't a narrer-minded man, but lumme, life's too short to be a Nonconformist very long. But onless you or me is one for a time, we ain't goin' to git much chance of 'angin' round the vestry and seein' wot things looks like. It didn't ought to take long to jest about sum up that chapel and then we shall see. Them's my plans, old man, and onless you got better ones we'd better see about it."

Mr. Mitch considered the scheme and saw that it was beautiful. He could already picture himself helping in the cellar work at the Westley Inn.

"A wonderful good plan, Boler—wonderful good. You got a 'eadpiece onto you. It couldn't be bettered. And now, 'ow do we divide it?" he asked delicately.

Boler coughed, looking worried.

"Well, I knows what we ought to do," he said. "I ought to git the job at Westlynn—because I can. Y'see, I ain't afraid of dogs—niver was—and I reckon I can convince Crail of it pretty easy too. 'E'd be likelier to take me on than 'e would you, meanin' no offence, Mitchy, of course. But the one '00 works at Westlynn 'as got to be the religious one likewise, for t'other can't make out Vs religious if 'e's 'angin' round a pub all the week."

Against his will Mr. Mitch's face brightened. "Yes, it's your job really, Boler. It's onlucky for yer, but you're a better actor than what I am! You could do the gospel grinder lovely —lovely, old man. And it'd be dangerous for me, as my missis goes to chapel reglar."

Boler looked gloomier than ever.

"Yes, but it might lead to bad feelin' between us, old man. One with a job all 'oliday and t'other with a job all work. I've thought of that, too. The fairest way's the best way, and it seems to me that we ought to play for it." He produced a bethumbed pack of cards from the carry-all and mournfully watched all the radiance die out of Mitch's face.

"It's only fair!" he said.

"Fair and square," agreed Mr. Mitch with an effort.

Boler shuffled the cards.

"What shall it be, old man?" he said genially, and a ray of hope illumined Mr. Mitch's eye.

"Nap. Three games. Best out of three games." Mitchy was good at Nap, and usually lucky.

"Nap it is. Cut for deal, Mitchy. Lowest deals."

Mr. Mitch cut the cards with exceeding care. He got the three of spades. Boler did better with the Jack of diamonds, and Henry dealt.

"Your call, Boler."

"Try three!"

"Go on, then," breathed Mitch, turning white.

Boler played the nine of clubs, Mitchy downed it with the king, and took the trick, leading an ace of hearts. Boler trumped with the deuce of clubs, and led a queen of spades. She stood by him, for his opponent played a ten of the same suit. Two to Boler, who led again with the nine of spades. Mitchy put the Jack on it with a thud. Two all! Henry whacked down the queen of trumps, with a yell, but Boler dropped the ace on it and threw a faint grin into the bargain.

"Brast!" went Mr. Mitch.

One game to Boler and his own deal. This was a tame game. Mitch called three and got every trick.

One game each. Mitchy was trembling as he dealt for the third and deciding game.

Boler got excited as he looked at his hand. He hesitated a second, then "Four!" he said.

"Nap! I'll go the bloomin' lot," cried Mr. Mitch.

He played the ace of hearts.

Boler softly put down the deuce. Mitch led the king of trumps. Boler played the nine.

Mitch looked nervous and quietly put down the queen of hearts.

Boler muttered and cast out the Jack.

Mitch dashed down the eight of trumps.

Boler replied with the king of diamonds.

Mitch shuddered and desperately put down the queen of diamonds, his eyes bulging.

Boler tried to smile and let the useless ace of spades fall upon the diamond queen.

Mitchy had won.

"'Ard luck, old man!" said Henry, totally unable to disguise his joy.

"Can't be 'elped," grunted Boler. Then after a forlorn pause—

"Bloomin' nice Nonconformist I shall look—I don't think!" he said hysterically, and gathered up the cards—"'owever—'ere's luck, partner."

"Luck it is, old man!" cried Henry, with enthusiasm.

They shook hands.

"A third for you, a third for me,

And a third for Can-aaa-ry Wing!"

hummed Mr. Mitch buoyantly, as they stepped out for the Westley Inn, where they looked to get hot coffee.

Halfway there they came upon a very pretty girl who was picking flowers. Her bicycle leaned against a gate. She was trim and dainty, and seemed pleased with the world in general, for she sang softly to herself as she fixed the flowers in her belt. She looked carelessly at the two adventurers as they passed, but almost instantly turned her gaze down the lane again from which direction came a sound of cantering hoofs.

She looked carelessly at the two adventurers.

Perry Riley, evidently exercising a young horse, turned the corner, passed them with a nod, and pulled up at the gate.

"What! is she my niece? Lumme, she's come on wonderful!' exclaimed Mr. Mitch, staring round. Even Boler seemed surprised.

"Well, if your missis is in line with 'er, old man, I'm blowed if I'd give much for your taste," said he ambiguously.

Mitch grinned.

"You 'aven't seen my missis yet," he replied meaningly. "And you 'aven't 'eard 'er talk yet. 'Elio, 'ere's another early bird."

It was that hard man, Crail, enjoying a stroll before breakfast. He was attended by the mighty Jane, and a big, slate-coloured, prick-eared beast that looked too large and truculent to be anywhere but behind bars. But Crail evidently had the pair of them well in hand, for they watched him always out of the corner of their eyes as they trotted alongside. The millionaire seemed to be in a good temper, for he stopped at sight of the silver-seekers.

"You two slinkums, again!" he said, in his loud, harsh American voice. "You're thunderin' near where I told you not to be. Seems to me you aren't slouching about here for your health only. Where you aiming for—the pub, eh? Going to melt your half sovereign mighty quick, eh?"

They stood, and the dogs walked round them.

"Goin' to git some coffee and work, sir, if there is any work in this show," said Boler, and Mr. Mitch nodded vigorously until the gaunt Jane looked up into his eyes, and he ceased as suddenly as though he had been electrically switched off.

Mr. Crail seemed amused.

"Don't much cotton to her?" he asked. He seemed inordinately proud of the animals. But he was prouder of his control over them, and he promptly proceeded to give them an exhibition of it.

"Don't move," he said to Mr. Mitch, and then, "Hold him, Jane—gently, girl."

The Great Dane quietly closed her jaws upon the pale Mr. Mitch's coat.

"Bring him here!" The dog pulled a little upon the coat and Mitch made haste to take the hint.

Then it was Boler's turn. The slate-coloured brute went to him at a word and took him by his rags.

"Bring him here!" said the millionaire. The dog gave the hintful tug, but Boler did not move, save only to brace himself up. The big beast rumbled in his throat and rolled his eyes back, looking up.

"Get wise and come along," said Crail. "Why do you look white?"

"Will 'e bite me if I don't?" asked Boler, very pale, his eyes glittering.

"I'll leave it to you," laughed the millionaire. "Better come."

Boler drew in his breath slowly, and looked steadily at his tormentor.

"I'm afraid of you, but by Gawd! I ain't afraid of your dog. I'll stay an' chance it."

"Don't you be a fool, Boler," cried Mitch, and his pied guard hushed him to silence with a snarl.

"You're a 'ard man, but you don't commit murder on the 'igh road! I'll stay!" said Boler, and resisted the dog.

The millionaire's mouth set and his eyes became hard.

"Bring him here, Slake," he said, quietly brutal.

"Slake" pulled, growling horribly, but Boler leaned back, his eyes on the dog. The threadbare coat ripped and his fangs came away. But he seized the coat again swiftly.

Boler noticed that the big hound avoided even pinching his flesh, and he was almost comfortable. "This is a trick," he said to himself, and stood his ground.

The hound, as he pulled, kept glancing at his master like a bravo awaiting the word.

But Crail gave in.

"Drop it," he said, and the beast went to his heels. A kind of contemptuous admiration showed for a second in his cold eyes.

"Your bluff goes!" he said. "But don't ever hope to do it again. I'll give you work—and your partner too, for your sake. You shall help in the kennels and Til fix him up chasing the snails out of the cabbage bed. Be around to-day."

He went away, apparently without noticing their thanks.

"Oh, 'ow I hate that man," whispered Boler, vengefully. "But I'll take 'is work, and I'll teach Mister Slake the feel of a whip if 'e ever catches 'old of me again."

Mr. Mitch stopped dead.

"You kin do as you like, old man, I wouldn't work fer 'im fer all the money I could add up in a month."

Boler grinned. "Nuther'd I if I 'appened to be afraid of dogs. But that's one of the things I ain't, and it's a chance—and a bloomin' good chance too. All you got to do is to tend to the Westley Inn part of the business. And 'ere 'tis too. And we'll 'ave eggs and bacon on the strength of the job."

They sat in the bar until their repast should be ready. Once the hard-faced landlord came into the bar, looked them over, and went away again.

"Looks a wrong 'un to me somehow," said Mr. Mitch, and Boler nodded.

"Seems to me it'd be a good idea to draw up our partnership agreement while we're waitin'," he said.

And so they borrowed paper and pen and ink and applied themselves to the task. It entertained them all through breakfast and the pipeful hour that followed the meal, but they finished it at last and signed it—thus, respelt.

Agreement between Boler Mitey and Henry Mitch, both of Ringford, Hants. Whereas there is silver hid in a spot in Ringford by some person or persons unknown to the parties of this agreement. And whereas Boler Mitey and Henry Mitch are undertaking to find such silver they agree to the following manner. One third to be took by Boler Mitey, one third to be took by Henry Mitch, and one third to be saved and reserved and put in a safe place for Canary Wing when he comes out of jail. Such Boler Mitey and Henry Mitch to leave no stone unturned in finding such silver and to help one another at all times hereto upon the request of the other and this we swear to and agree upon so help us God!

Boler Mitey. Henry Mitch.

"And that's done!" said Boler, putting the document in his pocket. "Now about where we kin live. I s'pose there's a room to be got somewhere."

But Mitch had a finer notion.

"We'd better 'ave a cottage to ourselves. 'Oo knows but what we sha'n't want to be out at curious times of night. If we lived in lodgin's, everybody in the villidge'd know all about our doin's and hours and 'abits next day. No, I knows this place, and what's more, I knows the very cottage, too. It's a quiet, liddle, damp place—jest at the corner of the plantation we passed jest now. If it ain't let we'll take it be the week. What d'you think?"

Boler nodded.

"Well, we'll go and 'ave a look and see if it's bein' lived in."

They went, lightheartedly.

ON the outskirts of Ringford village, in an angular red-bricked house, lived a Mrs. Gritty, an independent lady of no education, an indifferent presence, and very few manners. She was a middle-aged widow. Her husband, Ring-ford understood, had died abroad, and among other things she owned the cottage in Sandy Lane, of which Mr. Mitch had spoken.

Mrs. Gritty had just finished a substantial breakfast when she observed, coming up the path, those hitherto small-change adventurers, Messrs. Mitch and Mitey.

"More of them tramps," she said, wiping her mouth rather cleverly with the back of her hand, and leaned out of the window.

"What want?" she enquired, ungraciously.

The taller of the two—Boler Mitey—motioned to his companion to step forward, which Henry, nothing loth, did.

"We was wishin' to take your cottage, mum, in Sandy Lane, if it ain't already let to no party." He grinned amiably as he spoke, and the widow must have found something pleasing in his countenance, for she jerked her thumb in a ladylike way at the door.

"Come in," she said, and the partners entered, removing their hats.

"The rent's three shillings a week," announced Mrs. Gritty.

"Three shillin's a lot of money," said Boler, gravely, to the ceiling.

Mrs. Gritty surveyed him grimly.

"I don't care whether it's a lot o' money or a little o' money. It's the rent of that 'ouse—paid in advance too. Paid weekly, as well."

"S'posin' we says 'alf a crownd now," suggested Mr. Mitch softly. "We're goin' to live in the villidge and work 'ere, what's more! And as we don't s'pose our wages will be very 'igh at fust"—Boler regarded him with an air of surprise and pain—"we can't afford to pay more'n 'alf a crownd to start with. Later on, of course"—he waved his hand, vaguely suggesting rents running into three figures in the immediate future.

To the amazement of the pair the somewhat masculine looking Mrs. Gritty smiled upon Mitch.

"Oh, all right then," she said graciously, addressing herself wholly to Henry. "You'll find as 'ow it's a liddle damp, but that won't 'urt such a pleasant-faced, 'earty gentleman as you."

Mitch began to finger his cap nervously. Twice he glanced at Boler, who, however, was looking rather pointedly at a cut glass decanter.

"'Alf a crownd a week, then," said Mr. Mitch. "To you," replied Mrs. Gritty meaningly.

"To you," replied Mrs. Gritty meaningly.

"Thank 'ee," said Mitch. "When kin we move in?"

"That's as it soots you, Mr.—" The widow paused.

"Mitch, me—Mitey, 'im!"

"'Ave you got your furnicher 'ere, might I ast?" enquired the lady, and Henry stiffened.

"Well, no—on the way, on the way," he answered hastily. "Van—a pantantikon van—comin' along—very slow things—take a very long time comin' along, them vans!"

Mrs. Gritty became even more gracious.

"Well, any 'elp I can give to your disposal I shall be very glad, I'm sure," she said, in her best manner. "Any little temp'ry loan—I'm sure."

Mitch was on the point of declining and clearing out when Boler broke in—

"A sorsepan—a liddle sorsepan would be uncommon useful, madam," he said, "and a few plates and knives and forks. A old armchair or two—any odd things like that. A few bottles to keep our water in "—his eye sought the decanter again—"and a old kettle—they would all be a great 'elp to my friend Mr. Mitch an me."

Mitch nodded.

"All right, 'appy to 'elp, I'm sure. I'll 'ave 'em wheeled round this mornin'. You can let me 'ave 'em back w'en your own furnicher comes."

At this point Boler succeeded in leading Mitch's eye to the decanter, and, with it, that of Mrs. Gritty.

She took the hint this time.

"It's a hot, dusty mornin'," she said, and the silver-seekers made haste to agree.

"What'll you 'ave?" she continued, with startling and uncompromising directness. "Beer or cider?"

They did not get over the shock of it until they learned afterwards that she had once kept a small inn.

"W'y—thank'ee," said the surprised Mitch, "I'll 'ave a taste of cider—jest a taste."

"Beer fer me, please," said Boler, "jest 'alf a glass," modestly.

Mrs. Gritty was no fool—and instantly proceeded to prove it. She went to the door and shouted to an invisible servant girl.

"L'weeser, bring a quart of beer an' a jugful of cider."

"L'weeser," a small, miraculously unbuttoned-up village girl, bore in the refreshment, and Mrs. Gritty watched, with considerable interest and some admiration, what appeared to be a race between her new tenants to finish their liquor first. It was a dead-heat.

"Well," said Henry, briskly replacing his glass on the table by the vacant cider jug, "we must be seein' about it, I s'pose!"

"I'll send the things round bimeby," smiled Mrs. Gritty, and accompanied them to the door. She watched them go down the path, smiling thoughtfully.

"What a nice man that Mr. Mitch is," she said to herself. "I wonder where 'e comes from. They must 'ave 'ad a long journey—bein' so thirsty. Me an' Sarah'll call roun' at the cottage and 'elp settle 'em presently. That Mitey's jest th' sort o' man she'd take a fancy to, I do believe. W'y, 'ere she comes!"

A rather loudly dressed woman with a thin, bitter mouth and hard eyes was entering the gate as the adventurers were going out. And by the extraordinary, muffled sound that his partner made in his throat, Boler knew that they were face to face with Mitch's wife.

There was a queer, lopsided, apologetic grin on Henry's lips. But he need not have feared. The lady favoured each of them with a keen stare, so searching as to be hopelessly rude and—passed on!

The gate closed behind them with a little click.

"Lorlumme!" breathed Mitch as they went. Strictly speaking it was profanity. But it sounded more like prayer.

THE partners were busy moving in. That is to say they were comfortably leaning over the fence in front of the cottage smoking, and waiting until the furniture and domestic articles promised by Mrs. Gritty should materialise. Their coats were off and the gate was open.