RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

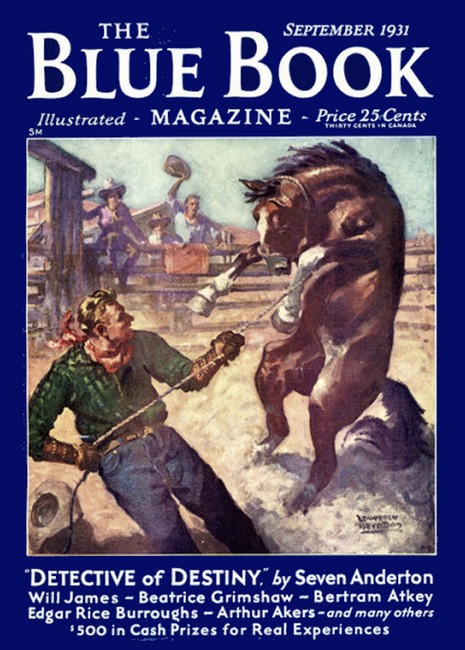

The Blue Book Magazine, September 1931, with "The Outlawed Centaur"

Author's Foreword

IN announcing to all old friends and fellow Blue Book fans that I claim to be the only honest nature-faker in the world, I wish to state that the idea was not in the first place my own. It was Uncle's—my Uncle George. Uncle George does not personally swing a very powerful pen, but he imagines things easily, frequently and profusely. And it was on the evening that he imagined that he saw two purple rabbits, a pink stinging-lizard with yellow stripes, and a carrot-colored vampire bat, all playing together around our radio set, that he suggested it might be interesting to write of the habits of these highly-colored hallucinations in their natural haunts. "These nature writers have done some very pretty work and they are all right—up to a point," said my Uncle George, carelessly brushing the vision of a gold- and apple-green climbing catfish off his sleeve. "But why don't one of these here writers write a story about an interestin' little creature like that green and crimson monkey that's sitting up there on top of the book-case? That's what I want to know. Pass the Scotch—and almighty quick about it!"

I know nothing about green and crimson monkeys—at least nothing to their credit; but I confess that Uncle's slightly frantic observations started a train of serious thought in my mind. The result I now wish upon you—in the following series of pretty-nearly-true narratives.

—Bertram Atkey.

THERE is no doubt that the late Mr. Shakespeare hit the plug fairly on the head with his mental mallet when he let fall the remark that there were more things in heaven and hell than are dreamed of in your philosophy, Horatio—or words to that effect. Shakespeare was, apparently, an authority on hell and the contents thereof. The present writer is not. But nevertheless I may say that Shakespeare could easily have added Asia to the places he specified as likely to contain things not dreamed of in Horace's philosophy. For example—

Had any skeptical person happened quite recently to have fallen out of a long-distance airplane at a certain spot not far from the heart of Asia, and survived, he would have met with company which would have caused him to search his philosophy with a fine-tooth comb, and still be left guessing.

For, leaning against a fig-tree, eating an oatmeal scone, a small bale of hay, some beans and a piece of cold pork, was no less amazing a child of nature than a big roan centaur.

That he was in an extremely bad temper was evident from the deep scowl upon his face, the angry flush on his cheeks, the irritated switching of his tail, and the occasional vicious pawing of one of his fore-hoofs.

At times he would pause in his meal in order to swear at the flies, and to stare intently down the valley up which, as the hoof-marks on the spongy turf beside a winding stream plainly showed, he had recently traveled.

He was not by any means a bad-looking centaur, though he was sorely in need of a shave and a currycombing. There were not lacking in his general appearance certain signs that he had been traveling fast for a long time, and a considerable distance. And this was indeed the case.

For he was in trouble—both of the heart and the pocket. He was in love, disgrace, a hurry and Queer Street. One of his shoes was loose, and he was miles from the nearest blacksmith; he had left his razors—and indeed practically all his portable property—in the hands of his creditors; he had not the remotest idea as to whither he was going; he was running short of tobacco, and he was an outlaw.

He lashed out viciously with both hind legs as he thought it all over.

"What sort of treatment do they call this to give a centaur who won the Midsummer Handicap carrying twelve stone two?" he said furiously. "And at a hundred to eight against! Because a centaur wins one race for that set of greedy, grasping hounds down there, has he got to win every race he enters for, or be accused of pulling himself if he happens to lose...."

A faint clatter of hoofs sounded from far down the valley, and he broke off his angry soliloquy abruptly, staring and listening to that distant warning. Then, with an ejaculation of surprise, he bolted the last bit of oatmeal scone, cantered down to the stream, took one little drink of water, wheeled, and left that place at full gallop.

It would have been extremely unwise to stay—and none knew that better than the fugitive; for, rightly or wrongly, he had been accused of the most serious crime a centaur can commit, and there was hot upon his trail a little party of those who proposed to point out to him the error of his ways.

But it was quite evident that they would have to get a very much crisper move on if they hoped to catch the furious roan. He had been gone at least five minutes before the pursuing party trotted into view.

It was a very second-rate-looking crowd which presently came up to the place where the outlawed centaur had rested. Their faces were the sort of faces which one encounters in the cheaper betting rings at one of the fifth-rate race meetings.

Regarded as men, they were obviously of no more serious consequence than any other band of toughs or hooligans. Considered as horses, they were of a quality from which even an Irish horse-dealer would have shrunk. There wasn't a centaur amongst them which could have been warranted sound.

Without inflicting upon the reader a detailed list of the various ills which characterized this curby, cow-hocked, broken-kneed crowd, it may be said that if these were fair samples of the population of the place from which Wo-Thair—for such was the name of the outlaw—came, then it must have been a pleasure to have had sentence of permanent outlawry passed upon him. But they were not representative—as will be seen. They loafed about round the fig-tree for a few moments, arguing and swearing. Then they decided to abandon the chase, and so began to struggle back.

And Wo-Thair, seeing but unseen, watched them from behind a crag up on the mountain-side.

"For a couple of oats, I'd go down there and kick the clockwork out of the whole bunch!" he said to himself.

But he thought better of it. Perceiving that his pursuers had given up the idea of following him any farther, he selected a warm, sunny spot, settled down comfortably on the mossy turf, and was soon lost in thought.... It was the old, old story over again with Wo-Thair—or almost the same old story. Wine, woman, and cards—that is to say, wine, centauresses, oats and racing. The only son of a wealthy widower, whose allotted span had been cut short by a grave misunderstanding with a Siberian tiger which had wandered very far south and sent Wo-Thair's father "west," Wo-Thair had started life before he had come to years of discretion. At the age of twenty-one he had found himself his own master, and one of the richest citizens in Centaurville.

Nothing was lacking in the equipment of the young centaur—except common sense. He was rich, good-looking, and was recognized as being one of the speediest five-furlong sprinters in the city. And moreover he was believed to be able to carry twelve stone over a three-mile course with the best centaur in the country.

But in spite of all these natural advantages, Wo-Thair had been a failure. Extravagance, late hours, the contents of his father's cellar, too many wild oats and boon companions, had ruined the lad in less than five years.

So, a fortnight before his flight, Wo-Thair, calling one morning on his solicitor—a wise, solemn-faced old pinto—for a further bale of bank-notes, had been the astounded recipient of information to the effect that he had no more money left, that his estate was mortgaged up to the limit, and that quite a large number of writs were about to be issued against him by certain of his teeming creditors.

Not till then did the young centaur begin to suspect that he was not quite so bright as he had always considered himself to be. A brief but frenzied conversation with the solicitor had shown him remorselessly just where he stood, and whom he had to thank for it, and he had cantered out into the street a beggar. What had added real pain to the interview was the fact that Wo-Thair, during the past month, had fallen deeply, genuinely and permanently in love—so deeply that no longer did the fair centauresses of the Centaurville Hippodrome charm him. Indeed, he had not once dropped in at the Hippodrome since he realized that henceforward there was only one centauress in the world for him—namely, Soho Mylass, daughter of the Mayor of Centaurville.

And indeed, the lad showed good taste. Soho was quite the daintiest and most graceful centauress in the city. Her features were of a perfection rarely witnessed in any country, and the bright auburn curls which clung tightly round her charmingly poised little head set off most exquisitely the pale gold-and-black rosettes of the leopard skin without which she rarely issued forth from her home. For the rest, she was a bright bay, of a very high-class type, obviously thoroughbred, rather Arab in appearance, and with beautifully, clean, cool, slender legs. Yes, Wo-Thair was right—she was the most perfect little thing that had ever cantered down High Street or playfully shied at a piece of paper at the corner. Withal, she was high-spirited. One would never need to take a whip to her.

And she returned Wo-Thair's love with all her heart—though without hope, for her father had always gravely disapproved of Wo-Thair. It was the hopelessness of ever winning the consent of Soho's parents that had made Wo-Thair's situation so painful.

WITHIN an hour of leaving the solicitor, he had thought

things out. He perceived that the future presented an aspect

of profound blackness, relieved only by one little ray of

light—and that ray was his chance of winning the Autumn

Cup, the three-mile handicap race which was always considered

the star event of the Centaurville autumn meeting. By a

lucky chance Wo-Thair had entered for that race some weeks

before. It was not his best distance—he was more of a

five-furlong specialist—and there were some other very

good centaurs in the race. He had never seriously intended to

race at all, for he was badly out of training. Everyone had

known it, and the result was that he stood in the betting at

66 to 1 offered, and few takers. True, Soho Mylass had quietly

accepted the equivalent of six thousand six hundred dollars

to one hundred about him, but few knew about that—or

cared.

Wo-Thair thought hard for a few moments, then decided. He would win the Autumn Cup if it were possible. He would back himself with every cent that he could get; he would train like mad in the limited time left to him; and if it came off, he would marry Soho and settle down to a quiet country life. If he failed, he would release Soho from her vows and emigrate.

That his efforts were not without fruit will be realized when it is said that on the morning of the race, some weeks later, the price of Wo-Thair in the betting was five to one—taken and wanted. Not only had a good many of the shrewder judges backed him, but there were signs that he promised to become a raging, red-hot public favorite—which, by twelve o'clock of the day of the race, he was.

No one worked on a race day in Centaurville. It would not be reasonable to expect it, any more than one would dream of expecting any centaur to work on a hunting day. Neither was it considered a sin to back one's fancy in a community where one's dustman might quite easily prove to be winner of next year's Derby (or its equivalent), or his wife the Oaks winner.

But there was rarely such betting seen or known as that on Wo-Thair for the Autumn Cup.

By noon be was quoted at six to four on. Pretty Mylass had mortgaged three-quarters of a year's allowance to put upon him, and stood to win a sum equal to fifteen thousand dollars. Even her grave and reverend parent, the mayor, a steady-going, rather cobby old brown, with splints, had taken a modest flyer on the lad. And the public was on him to a centaur.

At the post the price was three to one on—an unheard-of figure.

And Wo-Thair was a happy centaur. He knew his capacity to an ounce—and the only part of the race he might be afraid of was the last furlong. Had it been three miles less one furlong he would have considered the race a gift, for he had tried himself out most searchingly. And be usually found himself wilting away like a wax candle at midsummer about halfway through that last fatal furlong—just when he needed a reserve of speed on which to draw.

So he had hedged quietly. Most of his early bets upon himself had been made at very long odds, so that it was not difficult to put himself on velvet. His great friend Kumm Hup, had arranged it all for him.

He had five hundred dollars on himself at 100 to 1. He had, however, laid off about thirty thousand at an average price of two to one, so that if he lost the race, he would still win fourteen thousand five hundred, and if he won the race, he would win twenty thousand—on the whole, a tolerably cheerful position for a totally stone-broke centaur, he reflected as be waited calmly at the post.

It was soon over. Wo-Thair did his best, but the last furlong was too much for him. He was well to the fore throughout the race until that last short stretch, when he faded—and faded—and faded away. He reeled groggily into ninth place, and then some fool raised a cry that he had deliberately and of set purpose lost the race.

The public, agonized by the loss of their money on what looked like the biggest "cert" of the century, took up the cry; and Wo-Thair, on coming out of the runners' marquee about ten minutes later, perceived suddenly that his racing for that day was not yet over. Things were looking ugly.

"Clear out, laddie," said the old superintendent of police. "The sight of you maddens 'em. My lads can't hold them much longer!"

It was good advice. Wo-Thair saw that at a glance, and so he took it. As he started back through the marquee, he met Kumm Hup, looking worried.

"This is a devil of a business, old thing," said Kumm Hup. "The stewards have had an inquiry, and unanimously agreed that you've swung it on everybody. You`re warned off—and you know what that means!"

Wo-Thair did. It meant that he was not only warned off the turf, but that he was an outlaw.

Anyone who cared to could kick his ribs in at sight, without punishment or reproach. He was outside the protection of the law, and his only hope was in speedy flight.

He made it speedy, very speedy. Out of the tail of his eye as he galloped away, he saw Soho Mylass with a scrap of handkerchief pressed to her eyes—and so he set out on the flight the conclusion of which has been described.

FOR a long time the unfortunate young centaur lay in the

sun, pondering ways and means. Had it not been for the loss of

Soho and his winnings, Wo-Thair would not have greatly minded,

for he was, or believed he was, heartily sick of Centaurville

and had intended to leave it anyway.

"A bigger set of swindling, gambling, swearing horse-copers than that Centaurville crowd it would be impossible to find," he told himself. "The meanest, most unsportsmanlike lot of low hounds I ever heard of. I'm thundering glad to be out of the place—if only I had Soho and my winnings! There's one thing, though—I can trust old Kumm Hup. He'll find some means of getting the money to me. By Chiron! It was lucky we laid off the money to cash. Yes, the money's safe enough—but how about dear little Soho? If I know anything about her miserable old hack of a father, he'll lock her in her loose box at the least suspicion that she's still in love with me. Poor little soul!"

He got up, and stamped impatiently round.

"I must rescue her somehow!" he mused. "Outlaw or no bally outlaw! And so I will!"

He rubbed his bristly chin and glanced over his shoulder at his sweat-stained, dusty and ruffled coat.

"And I'll rescue a razor, a currycomb and a dandy-brush while I'm at it," he added.

Then he stiffened suddenly, listening.

From far away down the valley he heard again the clatter of hoofs. His face cleared as he listened. "If that's not old Kumm Hup, you can call me no judge of a centaur's hoof-sounds!" he ejaculated, straining his eyes through the distant haze.

He was right. Kumm Hup was apparently no mere fair-weather friend—as will be realized when it is explained that he was hitched to a tilted two-wheeled van heavily laden, which he had brought thirty miles. "Well, you're a brick, old thing—a genuine brick!" said Wo-Thair, hastening to help the panting Kumm Hup unhitch himself.

He rummaged in the van and found at once what he was looking for—a box of cigarettes.

"Yes, one of nature's noblemen, old son—that's what you are!" continued the warned-off centaur enthusiastically, and lighted the first cigarette he had dared smoke for weeks.

"Not at all, Wo, not at all," said Kumm Hup, a dark-complexioned hawk-faced brainy-looking chestnut. "You'd have done the same for me, old top, any day. Besides, bar these few things and the cart, I've only brought you bad news."

"What is it?" asked Wo-Thair.

"Well, I'm shockin' sorry, old lad, but—er—the fact is, you've positively done yourself in with Soho Mylass. She's furious. I went to her and said I was coming out to see you, and asked if there was any message, and she was curt. Quite brusque, what?"

"What did she say?"

Kumm Hup hesitated a little, then took the plunge.

"Well, you know, she seemed to believe that rot about your pulling yourself. She stood to rake in about fifteen thousand on you, you know. She was rather—er—wroth."

"Did she send any message?"

"Well, no—not exactly a message. She was just talking at random, old thing, quite at random." But Wo-Thair knew better.

"Come on, old top, out with it!" he insisted. "What did she say?"

"Well, the fact is, she said that I was to say that any centaur that would let his fiancée lose three-quarters' allowance without giving her a tip to hedge was not the kind of centaur that need ever hope for the privilege of furnishing a loose-box for her! She—er—rather dwelt on it, but I don't remember her exact words."

WO-THAIR perceived that his friend was determined to spare

his feelings as much as possible, and so he pressed him no

more.

"Right-o!" he said with an effort to speak lightly. "If she believes I tried to welsh her, let her. She may be pretty, but a centauress who pretends to love me—love me, forsooth!—and can believe a thing like that, isn't a centauress who is going to cause me any loss of slumber. All right, Kumm, let her go. I dare say I can battle along without her."

With admirably feigned indifference he lighted another cigarette, thus failing to observe the sudden gleam which brightened the rather gloomy eyes of his chestnut pal.

Then, with a shrug of the shoulders and a jaunty flourish of the heels, he began to run through the contents of the cart. Kumm Hup had chosen well. Everything was there which he could possibly require for the next six months, including the money he had won.

"Great work, Kumm, and much obliged."

"Not at all," said Kumm, and shook himself. "Must be trottin' along, I suppose," he said. "If there's ever anything I can do for you, old thing, let me know."

Wo-Thair nodded. Then they shook hands and parted.

SO from these causes and in this fashion began Wo-Thair's

experience of outlaw life. Thoughtfully he hitched himself to

the cart, and trotted at an easy pace into the wilds, musing

rather dejectedly as he went. And his musings were all of Soho

Mylass. Nobody, be he man, horse or half-man and half-horse,

likes being jilted or can ever really understand how anything

feminine can bring herself to lose him.

"I'm surprised at her," Wo-Thair told himself. "The mercenary little vampire! To turn a centaur down for anything serious, I could understand, but to hand him the mitten for losing a race which he nearly strangled himself to win is the limit. It gets my goat. Yes, it certainly gets my chamois! The little lobster!"

Thus musing, he covered some ten miles or so, when, arriving at the edge of a big, fertile plain, he decided to camp for the night. He found a moderately comfortable cave in the foothills of the mountains through a pass of which he had just come and lighting a fire, prepared himself supper, cut a thick bed of dried grass and settled down.

When at dawn the following morning he cantered forth from his cave feeling twice the centaur he had been overnight, his plans were clear. He intended to utilize his period of outlawry in travel—a long walking tour, so to speak. He did not anticipate having to spend more than six months in outlawry, for he had very little doubt that he could win the next Outlaws' Plate in a walk.

The Outlaws' Plate was the outcome of one of the more merciful laws of Centaurville. It was a race held twice yearly in which only outlaws could compete. The winner was granted a free pardon; the second was granted a pardon if he cared to pay the legal expenses of preparing same; the third was granted a pardon upon payment of costs and a year's labor for the State, and the also-rans were given twenty minutes in which to leave town. It was a wise law, and produced some first-rate racing, for the runners were invariably tryers. It was a five-furlong sprint, and Wo-Thair had every reason to be optimistic.

He had bathed, breakfasted, lit a cigarette, and had written a farewell note to Soho. It was brief and to the point:

Mr. Monty Wo-Thair presents his compliments to Miss Soho Mylass, and begs to say that he regrets his failure to win the Autumn Cup should have caused Miss Mylass any financial inconvenience. Had it not been for the fact that Mr. Wo-Thair is unable to work miracles, he would have won the race with great pleasure. He regrets that the alleged love which Miss Mylass used to assure him was ever his was not sufficiently strong to bear the temporary hack at her financial resources which Mr. Wo-Thair's unfortunate failure caused; and he assures Miss Mylass that if she wishes to recoup herself, she will be well advised to put her leopard-skin on him, Monty Wo-Thair, for the Outlaws' Plate next April. Mr. Wo-Thair would have liked to feel that during the rigors of the winter he must spend as an outlaw he could warm his frozen self at the fire of love; but as that is to be denied him, he must plow his furrow alone—except for such comfort as he may extract from the few friends he is likely to meet. He wishes Miss Mylass well, and hopes that she will never know the misery and pain of a heart so shattered as that of Mr. Wo-Thair.

"And if that doesn't make the mercenary little lobster squirm, I don't know what will," mused Wo-Thair as he read the letter with some little pride.

He folded the missive, hitched it and trotted cheerfully away toward the trade route from the deeper interior of Asia to Centaurville, where he hoped to encounter some traveler who would deliver the note for him.

Almost at once he met a peddler, an aged piebald (i.e., part of his hide bald, and the remainder the color of pie) who was dragging a cartful of imports for centauresses—such as ivory-backed dandy-brushes, tortoise-shell currycombs, silk tunics, "tails," whalebones, carved ivory hayracks, baby saddles, face-powder, niter, manicure sets and hoof-polishing outfits, and similar bric-à-brac.

The peddler willingly agreed to take the note on learning that it was for the daughter of the Mayor of Centaurville. The shape of his nose—outward scimitar bend—and a slight lisp was a sufficient guarantee that if there was business to be done with Miss Mylass, he would find her.

"I von't charge you anything for taking dis note, yes?" he said. "But if you will give me an interoduction and a reference, it will be better, aint it?"

So Wo-Thair scribbled him a line:

Dear Miss Mylass: Some years ago I used one of Mr. Spavinsky's currycombs; since when I have used no other.

Yours truly,

M. Wo-Thair.

And as the subtle jest was new to Spavinsky, he was more than satisfied.

So, mutually pleased, each went his way....

To accompany Wo-Thair through the next three months would be merely to share in an uncommonly chilly, lonely and uncomfortable time.

As the cold weather set in, he saw that his first airy idea of a walking tour was impracticable. So he found himself a dry cave, and spent a good deal of his time therein, sulking. On several occasions he was visited by other outlaws, but they were usually centaurs of no account—without breeding, manners or scruples.

He entertained the first one well, inspired by some vague "companions in misfortune" idea; but when he woke up the morning, he discovered that his companion in misfortune had rather alleviated his own misfortune and increased that of Wo-Thair, by the simple process of pinching several useful things which Wo-Thair had foolishly left lying about, and disappearing forthwith.

There was a time when he had trouble with wolves, but fortunately Kumm Hup had put a good bow and plenty of arrows in the cart, so that such of the wolves as were not pinned to the ground decided to move on. His cigarettes ran out, and about February his food supplies grew low. He found it necessary to eat a larger proportion of grass and oats than he cared about. But this was good, for he was training fairly hard.

But it was dull work at best. An Asian rhinoceros, seeking a good cave in which to lay up and nurse a wound which evidently irritated it, enlivened the dullness for a week, but eventually Wo-Thair, using fire, drove the intellectless brute definitely away.

Once, too, he had a palpitatingly narrow escape from a big party of Tartar wild-horse hunters—who appeared to think that he, Wo-Thair, was admirably adapted for work on a farm. They chased him in a huge circle a hundred miles in circumference, and he was only saved by hiding in a boggy swamp so sticky and tenacious that it took him a day and a half to get out. And when he was twenty miles away from the swamp, he was seen by a herd of the savage wild bulls which, from time immemorial, the centaurs had hunted, and was chased by these back into the swamp.

"I said I'd make a walking tour of it," he groaned when, many hours later, he stiffly entered his cave, "and I certainly am keeping my word."

Something moved in the darkness of the cave, and he shied violently.

But he need not have been so startled—as he perceived for himself when, a moment later, his eyes had become more accustomed to the gloom. For that which had moved was nothing more dangerous than a pretty little bay centauress about thirteen and one-half hands high at the withers.

She was smiling rather shyly at him. He recognized her at once.

It was Jeejee, Soho Mylass' maid. "Why, Jeejee, my dear girl, however did you get here?" he asked.

"I came for the sake of poor Miss Soho, sir," she said. "She has been trying for months to get into communication with you; but she had an enemy who has always prevented it."

Wo-Thair snorted in astonishment.

"Get into communication with me, Jeejee? But she—er—turned me down when I lost the Autumn Cup."

Jeejee smiled oddly.

"How did you know that, Mr. Wo-Thair?" she asked, watching him intently.

"Why, my friend Mr. Kumm Hup brought me the news!"

The little maid clapped her hands and kicked out with her trim heels delightedly.

"Ah! That is just what Mistress thought," she said, and added; "Well, that's not true. Mistress has nearly broken her heart and has gone completely off her feed since you left. Mr. Kumm Hup is always proposing to her—pestering her, I call it. She has sent several messengers to try to find you, but some accident has always happened to them. It has been terrible for Miss Soho. She has got so thin that you can count her very ribs as she walks down the street. And her coat is so rough that you would never believe she was a thoroughbred with three ostlaurs specially retained to groom her. And she is going over at the knees, sir. She seems to have lost all interest in life. She is always having nightmares, and although you can lead her to her meals, you can't make her eat. Oh, sir, it's terrible. I could not bear to see her like that, so I slipped out one night without Mr. Kumm Hup or his spies having the least suspicion and—here I am."

"Well, you're a little brick, Jeejee—a regular little brick. You must have had a rough time of it."

"Well, sir, I wasn't quite alone," said Jeejee, blushing.

Wo-Thair laughed.

"Ha! Who was the lucky centaur that you permitted to escort you, Jeejee?"

"Jentli Boi—the dapple gray, sir."

Wo-Thair thought.

"Jentli Boi? I don't remember him."

"He's the off-wheeler on the fire engine, sir," said Jeejee proudly.

"I remember. And a topping good centaur he is. Great amateur trotter, isn't he?" Jeejee flushed with pleasure.

"Yes sir. He was—until he got the situation at the fire station. The galloping there has spoiled his trotting. But the money is good, and then there's the pension."

"Where is he now?"

"He hurried back to duty, sir, after finding your cave for me," said Jeejee.

Wo-Thair thought hard for a few moments. "And so Miss Soho still loves me, Jeejee?" he asked.

"Oh, yes sir—she adores you."

Wo-Thair looked embarrassed, but Jeejee hurried on, "She wants you to meet her at Ten-Mile Gap on Thursday evening, at nine o'clock—to explain everything. Could you be there?"

"Wild horses wouldn't keep me away, Jeejee, my dear."

The little bay smiled and shook herself.

"And now I must go, sir. I took some of your things for breakfast, and I am quite rested. Is there any message for Mistress, sir?"

"Tell her I shall be at Ten-Mile Gap without fail, that I love her more than ever, that I intend to win the Outlaws' Plate in a common canter next month, and that—I will tell her the rest myself.—Oh, Jeejee!" Wo-Thair glanced at his muddy forelegs and felt his unshaven chin. "Tell her how well I looked—and—er—handsome—and say I've had a tophole time—er—camping out."

"Yes sir. Good-by, sir," said Jeejee demurely.

Wo-Thair took the bright little face between his hands, and implanted upon her lips just one little one.

"Oh, Mr. Monty!" said Jeejee, and caracoled away.

"Just for luck, my dear. You needn't mention that, though!" called Wo-Thair after her, and stood watching her until she disappeared into the mountain pass....

From then onward life was practically a song to the outlawed centaur.

If he had trained hard before, he trained desperately now. He was twice the centaur he had been—as hard as steel wire and as tough as pre-war motor tires. There was nothing in the whole country now that could hope to extend him over a five-furlong course. He tried himself out on a gray wolf that came prowling around one morning.

There was nothing in the whole solar system about swift and strategical retaining which that wolf did not know. He had the ability, the experience and—when he saw Wo-Thair come prancing out—the zest, for a great retreat. He felt in the mood, as it were.

He gave a nervous start, and forthwith began to drill a hole through the atmosphere in the direction of home at a pace which an eighteen-pounder shell might have envied.

But it was a mere joy-ride to Wo-Thair—who lifted that gray criminal into the Beyond with his heels in a chase of less than a quarter of a mile.

Everything went well. Wo-Thair picked up on the trade-route a broken-winded, outcast centaur—and from an abject tramp, transformed him, with a little discipline, into a tolerably good valet. That was a great stroke of luck, for when on the great Thursday he arrived at Ten-Mile Gap, he looked in extraordinarily fine fettle. His coat shone like silk.

It was just as well, for Soho, who came up at a rousing gallop a few minutes later, looked splendid. Evidently Jeejee's news had cured her.

Wo-Thair, after one quick, furtive glance, realized that she was not in the least over at the knees, and her ribs were no longer visible.

"Oh, Monty darling, I have been so unhappy. After that cruel, sarcastic letter! And to think of you all alone out in the wilds with the wolves and outlaws and wild bulls and horse-hunters!" She sighed.

Wo-Thair reached out for her.

"Ah, dearest, forget it," he whinnied tenderly. "Forget it."

And over a rocky crest the moon arose—and in the distance a wolf howled as though his heart would break. But the lovers were oblivious to moons and wolves....

IT was the day of the Centaurville meeting, at which the

Outlaws' Plate was run, and the bookmakers were as busy

as bees—though with less beneficial results to the

public.

There were eight runners for the Outlaws' event, and public opinion was strongly in favor of a great slashing, well-built gray, one Gidup, who had been outlawed for assault and battery upon the Hay Tax Collector. The betting was six to four on Gidup. Wo-Thair the public resolutely declined to support—a centaur once bitten usually shied twice. Consequently Wo-Thair stood at twenty to one—at which figure Soho helped herself freely both of her own account and on behalf of her lover....

To say that Wo-Thair won the race would be to cramp things overmuch. It would be more fitting to say he ate it alive. He made the other runners look like hippopotami. He did not merely seem to leave them standing still—he gave them the appearance of traveling backwards. And this in spite of the fact that he stopped at four furlongs to light a cigarette, and then canter home.

The mortified Gidup appealed for disqualification on the grounds that (1) as Wo-Thair whizzed past him just after the start, he handed him, Gidup, a ringing smack on the haunch, and cried insultingly "Come on, slow-coach, get a move on! Why, you're too slow to catch a Cabinet Minister!" and (2) smoking during the race.

He, Gidup, objected strongly to smoking during a race, and he pointed out that if the stewards permitted that sort of thing, the next they knew runners would be carrying flasks and taking a drink during the race.

But the stewards had lost too much good money on Gidup to feel that his objection possessed much weight. They promptly overruled the objection, and gave Gidup, who had finished fourth, the usual twenty minutes in which to make himself invisible.

So Wo-Thair came again into his own, and a good deal of the bookmakers' as well—far more than enough to settle down with Soho, with the cordial approval of her papa the mayor. And the example in matrimony they set was shortly followed by Jeejee and Jentli Boi—both of whom had collected a parcel over Wo-Thair.

And what of Kumm Hup? Did Wo-Thair punch his head, kick his ribs in or otherwise show him the error of his ways? He did not. For Kumm Hup, inspired by jealousy more than good judgment, had gone what was popularly known in Centaurville as a "buster" on Gidup. He was only saved from having to draw a dust-cart or something of that sort, for a living, by marrying an elderly centauress with considerable means, but even more considerable temper.

"And that, I think, will be punishment enough for poor Kumm Hup, dear, don't you," said Wo-Thair to Soho, as they set out for a quiet gallop in the moonlight one evening, and he was right.

Three mornings later Soho and Wo-Thair might have been observed trotting side by side across the plain toward the cave which had sheltered Wo-Thair during his outlawry. They were hitched to a very smart new pair-horse wagon packed with luggage, which they whirled along behind them like a feather. Soho's head was resting on Wo-Thair's shoulder and Wo-Thair's near arm was round Soho's waist.

They were on their honeymoon, which they proposed to spend camping out upon the spot where romance—thanks to Jeejee—had reentered their lives. A pretty idea and, as it proved, successful beyond description. Yes, indeed.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.