RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

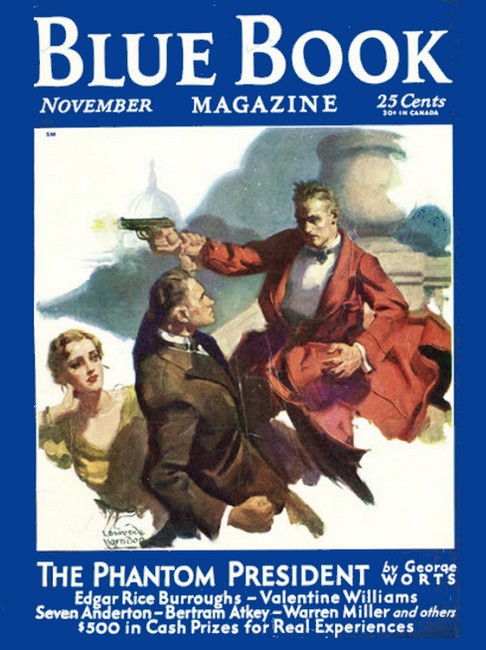

The Blue Book Magazine, November 1931, with "The Nose of Napoo"

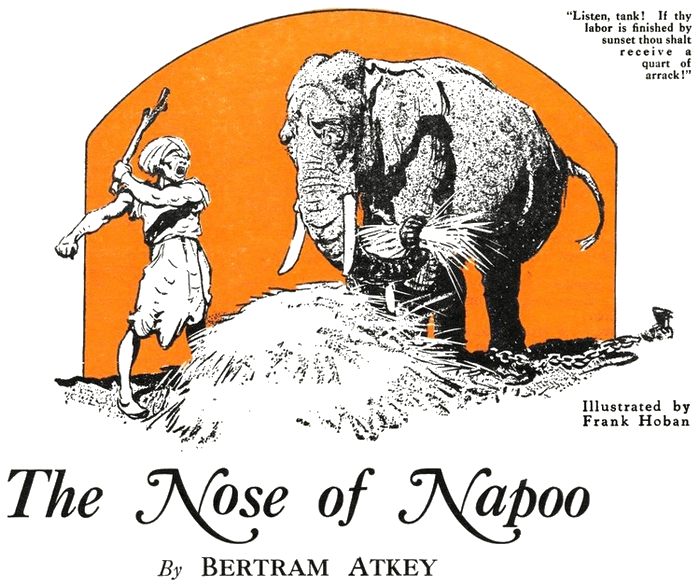

The moving story of a strong-willed elephant who

packed a vicious grudge, went on the warpath across all

India and camped on his enemy's trail for seventy years.

"O, THERE, my prince of elephants—hurry up and finish your hay! Get a move on, my pearl of great price! Wake yourself up, lord of the jungles!" shouted Ashkat the mahout to Napoo—his gigantic beast of burden—as he came out of the office of the manager of the big timber-camp in which, with some hundreds of others, they were employed.

The big tusker, busy with a bale of hay almost as large as a taxicab, stopped eating in amazement and stared at his owner, with a gleam of pained surprise in his little eyes.

What was this? Hurry up! In his dinner-hour? And the dinner-hour only about three-quarters over! This was indeed news to Napoo. The thing was foolishness. Obviously, Ashkat was joking. The great elephant flapped his ears contemptuously, and continued to perform upon the hay-bale adagio, as before.

But the mahout soon undeceived him.

"Ha, obese hog of hogs, dost thou believe I lie, then? Listen, tank! When these remaining timber-baulks be stacked, each in its proper position, I receive payment and I finish my labor in this place. Dost thou understand this, large pig? Hasten, then—and if thy labor is finished by sunset, thou shalt receive a measure of sugar, a bundle of sugar-cane and a quart of arrack!"

He banged the old elephant hard upon the skull with a teakwood club, in order to clear his brain and make him understand. But he need not have troubled. Napoo understood.

A measure of sugar, a bundle of sugar-cane and a quart of arrack—if they finished hauling the logs by sunset!

Napoo was too fond of raw sugar, sugar-cane, and especially that highly alcoholic beverage arrack, not to understand when these were promised to him—and he did not get them so often that he could afford to refuse any offer without full consideration.

He cast his eye across at the log-strewn area which Ashkat wished him to clear by sunset.

It was a strenuous afternoon's work; he saw that. If his gigantic tusks did not ache severely by the time they had finished, he would be very much surprised—yes, indeed!

Still, a quart of arrack—good, strong, rough arrack with almost enough alcohol in it to pickle his interior—made it tempting.

Napoo was not a teetotaler, and he loved the pleasant glow which a rousing stimulant, after a hard day's work, a bath, and a feed, gave him.

Ashkat was watching him.

"Well, my rajah, my beautiful one," wheedled the mahout, "wilt thou hasten?"

Napoo speeded up with the hay-bale, and Ashkat said that he was the king of all elephants, and that he, Ashkat, was his father and mother.

"I will return for thee in five minutes, Napoo. Eat quickly!" he added, and hurried away....

The way in which Napoo worked that afternoon positively scandalized the other elephants at the camp. The spectacle was so unusual that it seriously interfered with the labors of the others. They could hardly work for watching him.

Although he did not actually haul the logs at a canter, he came near it. It was well that there was no union of elephant workers, or the shop steward would have wanted to know something about it. There would have been a strike against overproduction in that timber-yard, as sure as tusks aren't teeth.

And all for the sake of a quart of arrack and some sugar!

"Ohe, Ashkat, that is a devil-possessed elephant of thine! Bang him hard upon the head, lest we others be called lazy and slow," shouted Mango, the chief elephant-driver.

Mango was growing old and idle, and his elephant and he liked to work at their own pace—which was some laps per hour less than that at which Napoo was storming along.

But Ashkat, perched comfortably on the back of Napoo's neck, only grinned and thought of the holiday coming to him.

Even the manager spared a moment from his labor to notice it. Leaning against his office door with a cheroot, he stared.

"I was wrong to promise to pay off that low-browed crook, Ashkat," he said. "That elephant of his is worth any three of the others here."

He reflected for a moment, then beckoned Ashkat across. The mahout slid down, and directing the attention of the perspiring Napoo to a log almost of the proportions of a small submarine, instructed him to carry on with that log, and went across to the manager.

"Your elephant is going musth (mad), Ashkat," he said.

"Nay, sahib. He is working well, that is all. He is a good elephant, and he shames all these fat slugs that haul but one log while he hauls three," replied Ashkat.

"I don't know so much about that," said the manager. "There's a funny look about him, I think. I shouldn't be surprised if he were to die suddenly. He looks very queer indeed. Er—how much do you want for him?"

Ashkat brightened up considerably. This was very convenient. The sahib wished to buy his elephant, eh? The offer could not have come at a better moment, for Ashkat was on the point of giving up work entirely. He had recently had several little windfalls—at least, he called them windfalls, though the police might have named them differently—and he was not, strictly, one of the hereditary elephant-drivers. He had, as it were, barged into the business on the strength of much tall talk and the possession of old Napoo—the devious means by which he had obtained him is another story—and he had had many irons in the fire.

Enough of them had heated to render him comparatively well-to-do, and he now proposed going back to where he belonged, namely, Nagpur in the Central Provinces, where he had a number of ordinary friends, some enemies, and one or two very special friends—ladies, these last.

If to his accumulation he could add a thumping good price for Napoo, he would be able to cut a pretty wide swath in certain Nagpur circles—and that was tempting.

So he mentioned a price; the manager mentioned another—half of Ashkat's. They worried it out for an hour, and finally completed the deal.

"Ah, sahib, you have bought the best elephant in Bengal for the price of the worst," said Ashkat. "Yes, sahib, assuredly I will tell him to obey Mango Chut, who is to be appointed his mahout. He will work well for Mango, who is the best mahout in the whole of India—next to me."

"Next to you!" The manager laughed. "You are a rotten mahout, Ashkat—with a good elephant you don't appreciate!"

Ashkat protested—more as a matter of form than because he really cared. The manager was right, and he knew it. He only valued Napoo for what the elephant could produce. He never took more trouble about the big beast than he could avoid, and than was absolutely necessary to keep Napoo in health.

Still he protested; a protest never does much harm, and may do good.

Then he went back to finish the day's work, his mind on the pretty things he would now be able to lavish on Lalji, his chief lady-friend in Nagpur—Lalji the Lovely, queen, so to speak, of the tight-packed quarter from which Ashkat originally came.

NAPOO finished the timber-hauling and swung contentedly away

to his pickets. Now, in a little while, for the arrack and

the sugar! It was not such a bad old world after all, thought

Napoo, as he ambled away. And even if one did have a tough for a

mahout, things might be worse.

At the pickets were the manager and Mango, and Ashkat held a little conversation with the big tusker—a conversation of which the elephant understood every word.

"Behold, my pearl, I go upon a journey. But thou dost not accompany me. Thou wilt remain here and haul timber for Mango. In all things obey Mango, who will be as kind to thee as possible. Bear that in mind, great one, for the ankus of Mango is heavy and sharp, and if thou art slothful assuredly will Mango batter out thy brains."

He turned away without emotion.

"And now, sahib, concerning the price," he said, and followed the manager to his office.

Napoo smiled to himself and got ready for the arrack and the sugar—and the sugar-cane.

Time passed. For an hour Napoo rocked to and fro, and for an hour after that. For he was a patient elephant. But he was getting impatient.

"That low blackguard Ashkat has either forgotten my supper, or else it's harder to get hold of a little drop of arrack than it was in my young days," mused the great elephant. "And out of those two reasons it aint the last one that's holding up my supper."

He brooded sulkily.

"Other elephants in this camp get their little drop of arrack now and then," he reflected. "Because they've got decent mahouts. But me—how often do I get any—even when it's promised? Never! Why? Because I'm unlucky in my mahout. Because I got a half-breed, up-country son of a rat-catcher for a mahout, instead of a true-bred elephant-man. And I'm gettin' about fed up with it. Thats what!"

He trumpeted angrily for Ashkat. But all the answer he got was a dour promise from Mango Chut that he would come across and cut his liver out if he didn't make less noise.

For a moment Napoo subsided, for Mango Chut was a genuine elephant-man.

But, then, Mango did not know that when Ashkat had left camp, two hours before, he had completely forgotten his promise to Napoo. It never occurred to Mango that any mahout could possibly forget to feed his elephant after a day's work. That was a crime unheard-of in Mango's philosophy. The old mahout probably attributed Napoo's uneasiness to indigestion, or some such matter.

But trouble was brewing—and brewing fast. The more Napoo thought over the treacherously broken promise of Ashkat, the more furious he became.

"I've stood enough and more'n enough from that low hound Ashkat!" he told himself finally, boiling with fury. "And now I'll square up with him—once and for all!"

It was quite dark now, and with a slight wrench Napoo tore himself free from his pickets, and rolled forward—looking for Ashkat.

But, fortunately for Ashkat, he was well on his way to Nagpur. Had Napoo come across him just then, his life might have been worth an anna—but by no means more.

And, even as it was, Ashkat was far from being out of the wood, for Napoo possessed something of which not only Ashkat, but almost everyone else, was aware—and that was a nose like a bloodhound.

From where he had inherited this extraordinary gift it was impossible to say. The only thing certain about it was the fact that he possessed it. Never yet, in the whole of his life, had the tracking power of the old elephant been thoroughly tried out. But now it was going to be.

The first thing Napoo did when he was free was to steer himself unobtrusively across to the big forage dump, where he took on board supplies enough to last him for quite a time.

Then he cast about the sleeping-camp until he picked up Ashkat's trail, which he settled down to follow—if necessary to the edge of the earth. For Napoo's mind was made up—and when his mind was made up dynamite would have been needed to persuade him to change it. Ashkat, as has been explained, was not a genuine elephant-man. But had he only known that Napoo had his trunk to the ground on his—Ashkat's—trail, he was quite wise enough about elephants to know that the best thing he could do would be to buy a barrel of arrack and hurriedly cart it back to the camp to placate the exasperated pachyderm.

But, sitting in a bullock-cart of a friendly stranger, lost in hazy dreams of the moon-eyed Lalji of the Alji (for so the street in which she lived was called), Ashkat had forgotten all about Napoo. Nor had he any wish to remember. The price was right—and it was safely secreted on Ashkat's person. That was all Ashkat cared about, then. Later, Napoo changed his opinion for him, as will be seen.

It was on the seventh of May, many years ago, that the events so far recorded in this true (roughly speaking) story took place.

Ashkat left the camp at six-thirty, en route for Nagpur. Napoo left the camp at nine-thirty en route for Ashkat. Ashkat's age was twenty-six. Napoo's was seventy-eight. Mark that, dear reader

It is no perversion of the truth to say that the distance from Dacca, in Bengal—near which town was the timber-camp—to Nagpur, in Central India, is seven hundred and fifty miles, as the crow flies.

Napoo, however, it is scarcely necessary to add, was not a crow. He was a big bull elephant, in a cold, sour, deadly temper.

But if Napoo was not a crow, neither was Ashkat; and Ashkat made one fatal error at the very start—two, in fact. One was that he decided to go on foot, when he could not "scrounge" a ride. The second mistake was that he rested his large hot hand for one instant on the rim of the wheel of the bullock-cart in which he wheedled his first ride.

Three days later Napoo, nosing diligently about the roads round the town, stopped suddenly, sniffing hard at a certain spot. Then he wagged his tail. He had hit the trail! He cast forward a little, found another Ashkat-flavored spot,—where the wheel completed another revolution, bringing the place where Ashkat had touched it in contact with the road again,—and from then onward followed the trail up.

The spotty nature of the scent puzzled the old tusker considerably.

"Is the man hopping home on one hand, or what?" he asked himself as he rolled along.

But, before he could answer, a native policeman, who had been watching him, stepped out into the road and commanded him to consider himself under arrest. Even in India they do not care to have loose elephants wandering all over the landscape.

But Napoo was not in any mood for argument. He raised his trunk from the trail, lapped it around the policeman, and gently deposited him on the side of the road.

"Hrumph-ah!" said Napoo warningly.

The native policeman very wisely hrumph-ah'd down the road as hard as he could gait it. Something seemed to tell him that it was better so.

Twenty miles on, Napoo lost the trail completely. This was annoying. Things had been going so swimmingly that already Napoo had begun to dream dreams about the quart of arrack which he intended having out of Ashkat; either that or his life-blood, one of the two—which one, Napoo was willing to leave to Ashkat's discretion.

But with the intelligence that even those great bloodhounds Chatley Blazer or old Uncle Tom, the famous Cuban slave-hound—now fortunately dead—might have been forgiven for not possessing, Napoo decided to stick to the main road.

The result was that he picked up the trail again at Chandernagore, followed it into Calcutta, lost and found it about eighty-three times in that great city and a week later, after being captured and recaptured until it became a perfect farce to try and hold him prisoner, he had the extraordinarily bad luck to strike the trail of a wandering fakir whose general flavor was precisely the same as that of Ashkat.

This trail was a week old, but Napoo was equal to it. He inhaled the scent with a thrill of joy, and pausing only to snatch a hasty snack from the stock of a frenzied but unlucky fruit-seller, he followed up the trail.

He followed it for twelve months, and ran into his man just outside Lahore—a thousand-odd miles from Calcutta.

Only then did he discover that the fakir was not Ashkat, nor resembled him in any degree, save flavor.

Napoo threw him into a reservoir, drowning him, and returned to Calcutta—for he was a patient elephant, and fond of arrack.

They captured him there again, and gave him a job of work in the suburbs connected with hauling masonry. This job Napoo left of his own accord ten minutes after he began, and headed westward, his trunk to the ground. He traveled a long way and for many months in this fashion, interfering with no one, and permitting no one to interfere with him.

"I'll get this guy Ashkat, or compensation in the shape of arrack, if it takes me a thousand years!" was the idea inspiring the old elephant—for, as will have been guessed, he was persistent as well as patient and thirsty.

It was, in a way, a great pity that he turned south at Raipur, for a little further perseverance would have brought him to Nagpur, where Ashkat, comfortably married to Lalji, had settled down to build up a good business as an all-round "sharp," making a specialty of receiving stolen goods.

Indeed, it is highly probable that Napoo would have nosed quietly on to Nagpur had he not got a whiff of a scent on the road leading out of Raipur which, though not pure Ashkat, nevertheless resembled it so very closely that Napoo decided, after some consideration, to gamble on it. He gambled on it for three years and a half.

It was a curious trail, this. Napoo lost it first at Hyderabad—some two thousand miles south of Raipur—a fortnight after he first connected with it. He was captured in Hyderabad, and worked unwillingly for the Nizam, carting water, for two years. Several times he crossed the trail, very stale, in the city, but one day he came plump on it, fresh and full. He broke away then and followed it at a racing pace down to the river, when he promptly lost it again.

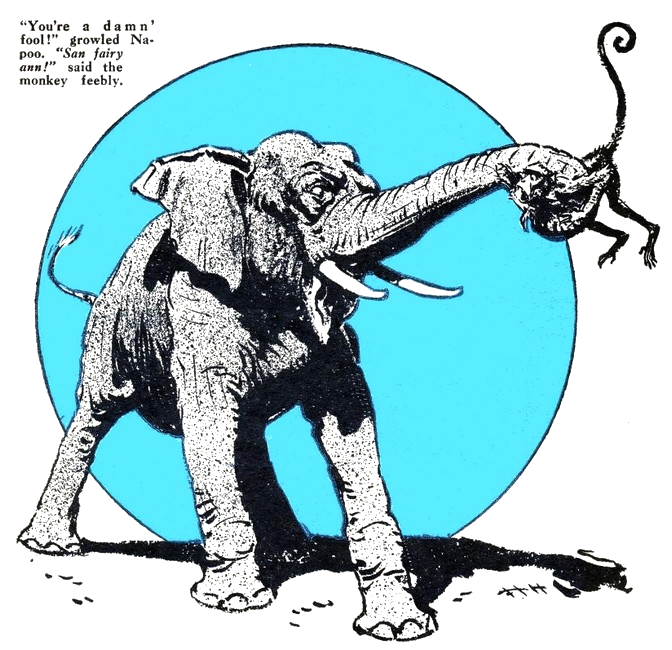

A tame monkey, afflicted with the insatiable curiosity of his kind, drew near to the excited Napoo and made a polite inquiry as to his trouble. "What's the matter, old man?" asked the monkey. Napoo ceased blowing his own trumpet for a moment, and regarded the ape superciliously.

"You been here long?" he demanded.

"About an hour and a half," the monkey replied.

"Well, did you see the man who made this footprint?" The monkey grinned. Like all monkeys, he could not keep up an interest in a thing for more than a few seconds, and this was somewhat of a tall order.

"About three hundred people have crossed the river this morning," he said, yawning. "Which footprint d'you mean?"

Napoo indicated one with his trunk.

The monkey came up and peered at the footprint.

"This one?" he asked.

"Yes—have you seen the man who made that footprint?"

"Have I seen the man who made it?"

"That's it."

"Yes, I've seen him," said the monkey.

"Did he cross over?"

"I expect so. He was one of the three hundred."

"Which one?"

"I don't know," said the monkey.

"But you said you'd seen him!"

"So I did. I've seen three hundred people cross over this morning. And he was one of them."

"Yes; but which one?"

"I don't know."

"D'you know what you are? You're a damn' fool!" growled Napoo; and forthwith he grabbed and flung the animal up against a tree, braining him.

"San fairy ann!" said the monkey feebly in pure A.E.F. French, and expired....

Napoo crossed the river and picked up the trail almost immediately. And at last he had a gleam of luck, for the trail, which was that of a silver-worker who had been lent to the Court jewelers of the Nizam by a firm at Benares, finished at Benares some months later, and the first thing that happened when Napoo trudged patiently into Benares was that he came right on the genuine trail of Ashkat himself, who, by sheer luck, had come up to Benares from Nagpur only two days before, to dispose of certain articles connected with his business.

MAD with excitement, his mind ablaze with visions of

arrack—arrack in jars, in pans, in pails, in tubs; arrack

to right of him, arrack to left of him—the elephant

charged along on Ashkat's trail.

But Ashkat, by now, was well used to having things on his trail—police generally—and he saw the elephant coming. He was standing near the entry to a dim, narrow, tortuously winding alleyway; one rarely saw Ashkat nowadays very far from some such convenient bolt-hole.

Napoo caught sight of him, and trumpeted a wild threat of what he meant to do to him. People were scattering, screaming that the big tusker was musth. But he ignored them, plunging along intent only on Ashkat.

Suddenly Ashkat recognized him. It was obvious to anyone who had any knowledge at all of elephants and their little ways that Napoo was out for Ashkat, and Ashkat alone. The ex-mahout had hardly begun to wonder why—when, in spite of the years which had elapsed, he remembered that he had, as it were, swindled Napoo out of a very hard afternoon's work with the promise of a supper which he had never given him. Ashkat needed nobody to tell him that elephants have long memories. And here he made his second mistake. Had he gone up to Napoo and soothed him with fair words until he could procure him a good "go" of arrack and sugar, he might have finished the feud right away. But he was not a true elephant-man, and his nerve failed him.

He hesitated a second, then popped into his bolt-hole like a rabbit, and was gone where Napoo could not, by reason of his bulk, follow him. He heard, far in the rear, the clamor which arose as the elephant butted and tore at the crazy sides of the lane, wrecking the jerry-built houses all around, and he decided forthwith to leave Benares while going was good.

So he worked his way around to the station.

Napoo, whose abnormal powers of scent had been extraordinarily developed during the last few years, winded him halfway across the city, and followed him, arriving at the station just in time to see Ashkat clamber into a train and disappear.

Late that night Napoo might have been seen tramping steadily down the line in the direction in which the train had vanished.

All went well until he reached Jabalpur, where a slight misunderstanding with a light shunting engine sent the engine into the repair-shop and Napoo into the hands of the veterinarian for the local authorities, who healed him and put him to more or less hard labor "on the land." He was so grateful for being healed that he worked all one afternoon on the land; but that night he proceeded on his way.

It was instinct now which was impelling him on to Nagpur, nothing else—but it was a good instinct, for it brought him first to a fresh trail of Ashkat, in Nagpur, some weeks later, and presently into full view of that gentleman, who was sitting behind a stall near his customary bolt-hole, working on a bracelet.

Napoo did not trumpet this time when he saw the ex-mahout. On the contrary, he came on with the silence and stealth of a cat.

But Ashkat, fortunately for himself, saw him—and forthwith disappeared, leaving Napoo to wreak his vengeance on the mat and such of Ashkat's wares as the man left behind.

He perceived that Napoo was after him, and probably proposed to spend the rest of his life in "getting" him. He thought it all over, and decided to lie very low indeed for such time as was necessary for him to dispose of his goods, and then to leave Nagpur.

The following day, having disposed of perhaps four-fifths of his property, at a serious loss, he was sitting indoors, arranging with Lalji—rather less lovely now—about following him, when a great trunk suddenly came snaking through the doorway, and the doorpost cracked under the pressure of a great head.

With a start of horror, Ashkat "snaked" in turn—out of the window, and over a few roofs, and then ran.

Napoo delayed too long over the pleasant task of reducing Ashkat's house to ruins, for by the time he gave up searching for him among the debris, Ashkat was well on his way to Amritsar, in the Punjab, with the intention of putting a thousand miles between him and his former property without delay.

THAT was the last that the two saw of each other for more

than twenty years, though Napoo was frequently in Ashkat's

thoughts, and Ashkat was permanently in Napoo's; for Napoo was a

tenacious elephant.

During that long period Napoo made the beginnings of a reputation which finally came to be known throughout India—for he searched that country for Ashkat as with a fine-tooth comb.

They got to know him well in Madras and Mysore, for he put in a lot of honest searching in Southern India. He was far from being regarded as a stranger in the Bombay province, and as for Hyderabad, they got to know him like an old friend. Because he had once nearly "snaffled" Ashkat in Nagpur, he had a weakness for the Central Provinces, and usually could be relied upon to turn up along about the autumn of every year. Bengal and Assam bore upon their faces many million of his footprints; at Dacca once they recognized him, and the manager of the timber-yard where the original promise of arrack had been made tried to detain him and give him a job. He claimed, and rightly, to be Napoo's owner. But he might as well have tried to detain a simoom. Napoo threw him into a water-tank, and left. The flavor of Ashkat had quite died out of the place, and Napoo was no longer interested. He ran through Nepal, but was unlucky—it was in Nepal he lost half a tusk, splintered on a rock during a misunderstanding with a brace of tigers. He worked his weary way through Agra and Oudh to Rajputana, without result.

"I'll take a quick run through the Punjab," he said, "and then nip down to Nagpur. It's time I had another look round down there." And this he did.

But he had not reached that stage without adventures enough to fill a thick volume and to empty a dictionary. He had been "pinched" a hundred times, but he no longer killed the light-fingered gentry who tried to steal him. That had become monotonous. He usually threw them into the nearest water and proceeded on his way. He became as familiar with jungles, deserts, and forests as with towns. He fell in love with wild and tame ladies of his species, but he never really settled down to permanent domestic bliss. He fought many battles with other elephants, and won most of them—for much exercise had rendered him very nippy on his feet. Tigers and similar interesting denizens of India he destroyed ad lib, if they interfered with him.

And his sense of smell became miraculous. His health was perfect, and except for a growing tendency toward corns on the feet, left nothing to be desired. His patience was monumental, and his passion for the arrack he was determined to get from Ashkat some day became unique.

Occasionally he had a drink of arrack given him, but it never tasted as arrack should—as for instance, the particular quart he was in search of would taste. That, by much dwelling and brooding upon it, he believed would be a species of nectar, when he got it, with which no other arrack would be comparable.

AS for Ashkat, he had settled down in Amritsar and prospered

exceedingly. He was one of the kind that prosper.

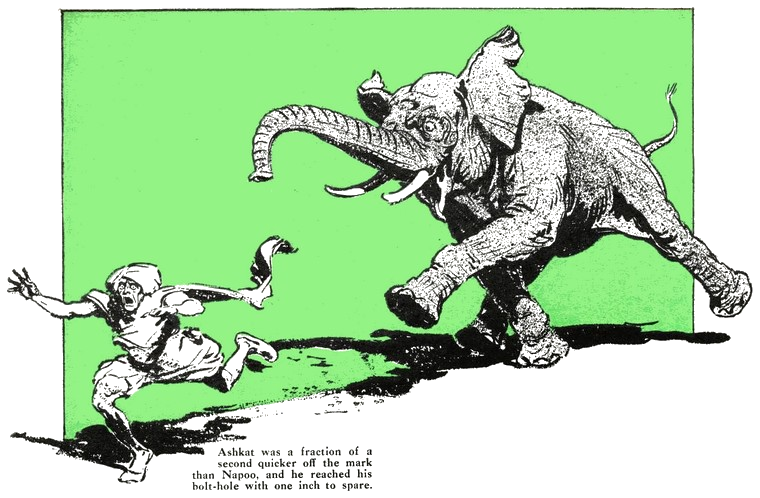

Then, as luck would have it, he and Napoo came face to face with each other one day in Lahore. Each recognized the other in a flash, though time had worked many changes with them. The meeting was so unexpected that they stared at each other for a second, rigid.

Then Ashkat started for a bolt-hole—an alley about thirty yards off. He ran as few men over sixty have ever run. He was a fraction of a second quicker off the mark than Napoo, and he reached the alley with one inch to spare.

Napoo followed him up the alley by sheer impetus until he was wedged in so tightly as to be immovable.

And by the time they had pulled down half the alley to release him, Ashkat had returned to Amritsar, settled his affairs, and, leaving the business in charge of his eldest son, had departed en route to Mandalay.

But he was only just in time. Even as he left the old home he heard a crash behind him, and, turning, he saw the indefatigable Napoo starting to search his house inch by inch—just as he had done at Nagpur more than twenty years before.

Save for the money he had on him, Ashkat was penniless, and he now did the worst thing possible. He decided that he would travel mainly by road to Mandalay—nearly fifteen hundred miles as the crow would fly, if any crow were sufficiently ill-advised to attempt the trip.

During the first thousand miles Ashkat had thirty-two narrow squeaks, seventeen close shaves, nine near things, four within-an-aces, two skins-of-his-teeth, and two hundred and nine false alarms—all from the attentions of Napoo.

Finally, at Patna, months later, Ashkat, in spite of his dwindling money reserve, took to a boat on the Ganges, and had the first night's rest he had had since leaving Amritsar.

"I was a fool to break my word about that arrack," he said as he curled up stiffly in the boat, leaving Napoo trumpeting his disgust on the bank after one of the "skin-of-his-teeth" escapes.

And then Napoo struck a streak of really bad luck.

He followed the river down to Bhagalpur, and there hit upon another "double" of Ashkat—a scent double, that is to say. Unless they have about three hundred million different kinds of scents, one for each person in India, a country with a population of three hundred millions—which is unlikely—it was inevitable that Napoo should suffer an occasional duplication of Ashkat's flavor, such as this one which he lighted upon in Bhagalpur. It was stale, perhaps a month old. But this was nothing to a tracker with Napoo's power of scent. He followed it.

Whoever the owner of it was, he was traveling fast. He was, indeed, a lama, hurrying home, traveling light, from a tour in India—and Napoo followed him to Thibet.

The lama fell over a precipice not far from Lhasa, and by a miracle of ingenuity Napoo climbed down after him —only to discover that he had been following a delusion and a snare. This body was that of a religious man.

Napoo laboriously climbed out of the chasm and went back to Patna. He thought it over as he went—his trunk-tip, as usual, half an inch from the ground—and he decided to give Nagpur another trial, and, failing that, run through all India once more. For he was a patient elephant. It was, he considered, a good idea. He was a hundred and thirteen years old when he first got this idea, and Ashkat was about sixty-one.

As he planned it, so Napoo performed it.

Thirty-four years later Napoo finally relinquished the idea that Ashkat would return to his old haunts, and further, came definitely to the conclusion that he was not in India proper at all.

He came to this conclusion one afternoon in a paddy-field down in Madras.

"There's no doubt about it," he mused. "The swine dodged me properly that time at Patna. He went south past Dacca—and stopped south. I'll give the south a trial—Burma. And I hope I touch lucky this trip, for I'm not so young as I used to be, and I'm getting fed up—in a way. Right, then! I'll give Burma a look-up."

He heaved himself out of the paddy-field, full of rice and optimism, trampled the owner of the rice into the mud as that individual unwisely came out to drive him off, and started for Burma—a seventeen-hundred-mile stroll, if it were an inch.

NAPOO was now a hundred and forty-seven years old, and

Ashkat, if living, would be about ninety-five. Time had told

on the elephant, particularly on his feet. His corns were very

troublesome, and his skin had lost the bloom of youth. His tusks

were not at all what they had been, and the few hairs he bore

upon his body were gray.

He was a familiar sight all over India now, and he rarely found it necessary to kill people. They left him pretty much to himself. In his younger days he had been short-tempered, but he had long grown out of that.

He was now, really, a philosophical and extremely expert long-distance tramp, who enjoyed himself far more than one might have imagined.

"I've seen life," he would muse. "And I've visited cities in my time. I've had a lot of good food and my share of bad. I guess I've got a keener sense of smell than anything else on legs in Asia." That was true. If Ashkat ever got within forty miles of Napoo the elephant's power of scent was now ample to pick him out at that range.

"And, bar my corns and rheumatics, I'm a young 'un yet. Still, I shall be glad of that drop of arrack."

Thus musing, he would loaf along, day after day, decade after decade.

He was Experience incarnate. What he did not know about India was not worth knowing. He had a friend in every town, a wife in every jungle where elephants lived. From Trivandrum to Kabul, from Tutticorn to Lhasa, from Gilghit to Cattack, from Manipur to Herat, Napoo had nosed his way, hither and yon, there and back.

Now he was going to have a glance at Burma. But he was aging fast, and it was not till five years later—for he had looked in at Baroda, where twenty years before he had smelled a track not unlike that of Ashkat, on the way —that he approached Mandalay.

He was not hurrying—just doddering along, taking it easy, for he was feeling rather tired. He was considerably over at the knees, too, and deaf, and his eyes were dim.

It is a long-lived elephant who lives over a hundred and fifty years—and Napoo was now a hundred and fifty-two. But he always had been a tenacious animal.

He slowly climbed a hill some thirty miles from Mandalay; arrived at the top, he paused to take a good comprehensive sniff of the surrounding country, then to assort the various and many odors.

But with the first inhalation he started and stiffened. There was a strong touch of pure Ashkat in the air—unmistakable, plentiful. It came from about twenty miles east.

"That's Ashkat!" said the old elephant. "Bismallah! How it takes my mind back!"

Slowly chuckling a senile chuckle, Napoo tottered away down the hillside.

Late that afternoon he found himself approaching a lonely hut, which stood all by itself in a clearing.

He halted on the edge of the clearing and peered out.

Sitting in the sunshine by the door was an old, old man, with a white beard and white hair, nodding and talking to himself. It was Ashkat.

Napoo stared at him. Yes, it was Ashkat. He could not see him plainly, but his nose could not deceive him.

The old elephant was worried. He wanted this old man badly—very badly. He had gone to a lot of trouble to find him. Now he had found him, but he had clean forgotten why he had wanted to find him! It was something about some timber somewhere, he fancied, or some timber-yard, or something or other; for the life of him Napoo could not remember. For he was well on into his second calf-hood—well on.... It was a pity—a great pity; but probably it didn't matter much.

Then a small boy came round the corner of the hut, carrying a two-quart vessel.

For, as it chanced, Ashkat was celebrating his hundredth birthday, and one of his little great-great-grandsons had brought him up a gift of arrack from the village.

"Here is the arrack, Grandfather," said the child, staring at the old man.

Then he asked: "Grandfather, why do you like to live up here all alone?"

"Hey, my boy?" asked Ashkat, who was very deaf. The boy repeated the question, and Ashkat pondered.

"Why, because— Let me see, now—why was it?"

He puzzled over it for a minute, then lost interest.

"I don't know, my boy," he said. "There was a reason in my young days; I think I used to be afraid of something down there—I dunno. I've forgotten what it was."

"They say you're afraid of elephants, Grandfather," said the little boy.

"No, my son—not at my time o' life. I never was."

"Good-by, Grandfather," said the boy—and went away.

Old Ashkat peered about, and took a pull of arrack. Napoo liked the smell of the arrack as it was wafted to his nostrils. It seemed to stir old memories; it did not awake them, but shook, as it were, their dry bones. He doddered across the clearing. The old man saw him, and it occurred to him that in his young days elephants would drink arrack. So he took a long pull at his pannikin, refilled it, and offered it to the elephant. Napoo drank it gratefully.

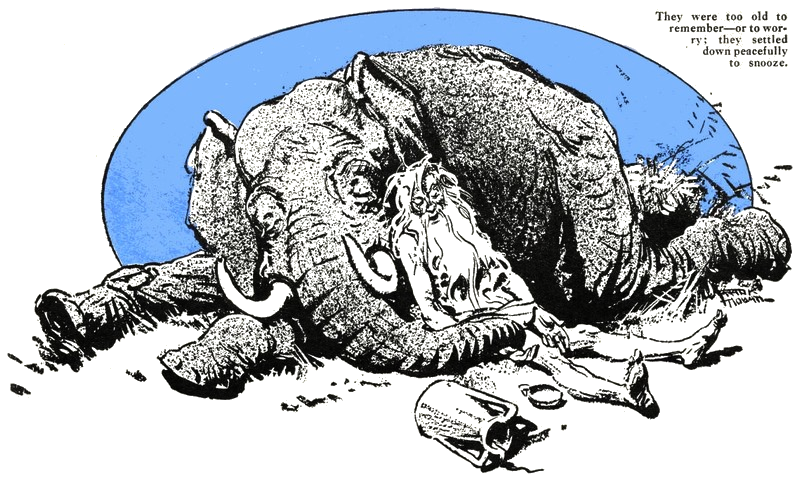

Between them they finished the two quarts. They were very old—too old to remember, or to worry if they had remembered.... Then they settled down peacefully in the sunshine to snooze.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.