RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, April 1932, with "The Last of the Dinosaurs"

This story was illustrated by Margery Stocking (1888-1993), whose

works are not in the public domain and cannot be reproduced here.

You may have faint misgivings

about the historical accuracy of this

little idyll of wilderness life, but we

think you will enjoy it none the less.

THE hero of this story was behind the times, old-fashioned and out of date, for he had stood still while the world went forging ahead. He was about forty million years behind—for he was a dinosaur, and he rightly belonged to that age which is known as the Mesozoic, when the world was largely populated by reptiles. Not necessarily squirmy reptiles, but reptiles of all shapes and sizes—out-sizes and unfits, for the greater part.

Steggy—for so during his brief Twentieth Century career the dinosaur came to be familiarly known by the press, chiefly no doubt because he belonged to that group of dinosaurs called Stegosaurus—was one of the out-sizes. He bore a close resemblance to an animated tank, except that he was much more warty, and that he had a spine rather like an overgrown crosscut saw—kind of notchy.

He was larger, too, than a tank, approximating more nearly to the size of a small chapel, or a police-station....

The awakening of Steggy from the long sleep which had put him so far behind the times was so very spectacular that it can never be sufficiently regretted that there was nobody present to witness it. It was the bursting of a glacier in which for so many millions of years he had peacefully slumbered, that awoke him.

In those far distant days before Steggy embarked upon his lengthy sleep, the haunt of the big dinosaur had been somewhere north of the region now known as Alaska. There he had lived a comparatively peaceful life, browsing harmlessly about the district on anything that came his way—trees, grass, leaves, smaller dinosaurs, and any other of his quaintly shaped neighbors that were sufficiently ill-advised to get within reach of him.

Then had come an unusually bitter winter—and one morning the dinosaur, after a particularly heavy supper (he had come upon a fat Triceratops cub when it wasn't looking) had overslept himself. True, he had half-awakened at his usual time. But he was very sleepy and felt heavy. This heavy feeling was probably due to the fact that he had been so severely snowed upon that he was buried under some thirty-five feet of snow weighing many tons. He was not hungry; the late Triceratops cub was lying rather weightily upon his chest, so to speak; and he had simply turned over and renewed his slumbers. The snowstorm continued for some six months on end, and the frost did not cease for some millions of years.

The result was that when Steggy next woke he felt heavier than ever. It was dark, too, and he seemed cramped for room. He decided to wait for daylight—entirely unaware that there was plenty of daylight some hundreds of yards above his head, and without the least notion that to burst his way up to it was a feat far beyond even his gigantic strength. So he slept again, and the ice continued to accumulate round him. Year by year it piled up over and around the entombed dinosaur. Colossal snowstorms swelled the accumulation, incredible frosts turned the snow to ice, and razor-edged prehistoric blizzards polished the mountainous pile. But Steggy neither knew nor cared. He was curled up down below, with a few million tons of ice on him, and he was out of the snow and the wind.

Years, centuries, epochs, ages passed over his weary head; polar seas formed about him, and were worn away, melted and disappeared. Geology took place, and carried on business for years all about him, failed, went out of business, lay dormant for a while, re-started and went through the same process over and over again. The Jurassic, the Cretaceous, the Eocene and Oligocene ages went flickering over Steg's head like bats. So did the Miocene, the Pliocene and the Pleistocene.

But they did not interfere with old Steg.

Earthquakes, erosions, upheavals and floods, tidal waves and catastrophes occurred in the neighborhood by thousands; but even if he could have heard them at all (which he could not), they would have seemed no more than the far-off gentle sigh and murmur of zephyrs. Volcanoes came into action not far away, worked hard for their allotted space, became extinct, crumbled away and trees grew over them into vast forests which ultimately became coalfields and in turn were washed away by new oceans. But it made no difference whatsoever to the slumbering dinosaur.

And so the world grew old and more reasonable. It settled down and gave up many of its wilder and more irresponsible practices. And ultimately the mighty coating of ice which had imprisoned (and protected) Steggy all these years began slowly to melt. It took a million years or so to do so, but eventually—in the Fifteenth Century—it melted down to a mere glacier not much larger than the Himalayas.

And presently, one Thursday afternoon in mid-September, Twentieth Century, it burst. It was a big business, that burst, and nobody witnessed it. The only important living thing within hundreds of miles was Steggy; and he was busily occupied in trying to call to mind the exact place in which he had left a haunch of that Triceratops cub for a snack before settling down to the serious matter of finding breakfast.

It puzzled the old dinosaur very much to find that he had forgotten where he had buried that haunch—puzzled and annoyed him, for he was hungry. He racked his brains in vain to think of the place. This did not take him very long, for he was very short of brains. Most of the dinosaurs were. Steggy, for instance, was between twelve and fourteen feet high, but he had about as many brains as a newt.

And his lapse of memory was excusable, for certainly forty and probably many more millions of years had passed since the unfortunate creature had buried the haunch-bone for which he now craved so passionately. He felt stiff, too, and a little chilly. After all, he had been preserved in ice for a long time. Also, he was feeling rather low in health, and his skin did not fit him very well. It felt baggy.

He stood in the hot sunshine listening to the water trickling off him as he thawed, and his digestive machinery shrieked for employment.

There came that way, mooning along in an absent-minded manner, a big grizzly bear, muttering to himself. He paid no attention whatever to Steggy. Probably he was laboring under the dangerous delusion that the dinosaur was a large chunk of rock. Indeed, there was no doubt that such was the case; for the big bear, either lazy or tired, and certainly unlucky, came up and lay down with a grunt of satisfaction between the two gigantic pillars which were the old dinosaur's forelegs.

Steg lifted a hind-leg and put it abruptly down upon the bear, which went pop under the terrific weight of the stroke, and was transformed into breakfast for the dinosaur before it realized what had struck it.

Steg swallowed the bear and felt momentarily stayed. He bit off a few trees and added them to the grizzly while he absently contemplated the scenery, wondering which way to go.

"Place seems to have changed, somehow, since last night," he grunted. "Funny. It's a lot warmer than it was, too."

He listened, and caught the sound of rushing water from somewhere not far ahead. All his arrears of thirst surged into his mind at the sound, and he lumbered forward at a slow clumsy gallop, creaking as he went, and shaking the earth like a howitzer.

He came almost at once upon a river where he drank himself three feet bigger round without once drawing breath.

Some minutes later, having taken aboard so many gallons of water that the writer, who has a reputation for adhering strictly to the truth, dares not mention the precise quantity, the dinosaur, feeling fairly fit again, headed south.

Steggy wanted warmth, and old-fashioned though his natural instinct was, it inspired him to go south. So in blind obedience to instinct he headed south, snapping up any odd trifles he came across—two bull moose, for instance, whom he found fighting, with their horns interlocked. The moose is an intelligent animal, courageous, swift and cunning. If either of the belligerents could have realized that Steg was a genuine dinosaur, it is quite possible that both moose might at this moment be roaming the wild free and happy. As it is, however, they went south with Steggy. So did a considerable number of young pine trees. The resinous flavor of these interested the poor out-of-date animal immensely, and he treated them much as we treat celery. A timber-merchant would have found him an expensive pet.

Bears pleased him, too, for they were fattening for their winter sleep. He developed a certain amount of skill in bear-catching. What none of the denizens of the Alaskan wilds ever seemed to understand was that the dinosaur, in spite of his mighty bulk, and his age—and it would be idle to deny that he was getting on in years—could spring like a hop-frog. This was due to the incredible strength of his unreasonably vast hind-legs. There was more than a touch of the kangaroo about Steg, as there had been about most of the Jurassic flocks and herds with which Steg had spent his youth.

It is undeniable that when Steg jumped, he came down heavily—rather like a locomotive falling into a chalk pit But he usually got what he jumped for, though he generally mashed it into a pulp.

But in spite of his science and his instinctive knowledge of how to use his weight, the dinosaur had his failures. One of these occurred shortly after he left Alaskan territory. For some days flesh-food had been scarce. The news of Steg's arrival had circulated rather completely throughout the animal inhabitants of that region, with the result that Steg was given plenty of room in which to travel. There was never any overcrowding in Steggy's neighborhood now. So the dinosaur had got out of the way of invariably selecting large meals. He did not disdain plenty of small ones.

He was lumbering along one morning when he perceived standing some ten yards away a pretty little striped animal with a bushy tail which it carried erect like a cat's. It was a particularly virile and healthy skunk.

"It's small—but maybe it's tasty," thought the dinosaur, and leaped like an elephant with a charge of dynamite behind it.

It was not often that Steg missed what he jumped for. Nevertheless he missed that skunk. Probably it was because his instinct told him that he was engaging in a singularly doubtful enterprise, and accordingly he endeavored to stop himself in midair—in vain.

He came thundering to the ground, his queer-shaped head and face about a foot short of the thoroughly irritated skunk—who at once made its irritation manifest.

They had some tolerably vivid odors in the Jurassic age, and they were no slouches at perfumes in the Mesozoic. Steg had been born in one or other of these, and it may be taken for granted that he was fairly well experienced in weird smells. But the little effort of this modern skunk would have made the best the Jurassic could furnish a pale, weak and colorless affair.

For one fleeting instant the dinosaur thought a mountain had fallen upon his head and face and flattened them; then he realized that it had not, but wished that it had. For he was the dead center—or at least the half-dead center—of a Cyclone of Smell.

He roared and moaned aloud; he whined like a wolf and barked like a dog; he neighed and snorted; he brayed like an ass and lowed plaintively like a cow. He gasped, crowed, blinked his eyes, shook his head, ground his teeth and wagged his tail. But it was all in vain. The smell clung to him closer than a brother.

He leaped into the air, and turned six back somersaults and two handsprings; he buried his face in the grass, and the grass stopped growing; but the smell did not cease smelling. He sat up on his haunches and pawed at the air, gasping for breath. Strange colors floated before his eyes. He saw stars, comets, asteroids, moons, planets and suns—complete constellations, in fact, but they were all overpoweringly flavored with North American skunk.

He lost his temper and tore up the earth, forgot his anger, lay down on his side, put his feet on his face and cried like a child. But it did not abate the general skunkiness of things. So the dinosaur shut his eyes and set off at a wild gallop through the forest.

He cut a swath through the wood like a hurricane. Trees snapped off like carrots before his onset. But he noticed them no more than grass-stalks. He won clear of the woods and fell over a cliff. But the smell fell with him, and he continued his flight across a narrow sandy beach, finally finishing in about fourteen feet of ice-cold water.

He had blundered into a river, and here he found a slight relief. He remained in the water, soaking his face, for the rest of the day, a cowed and humble dinosaur.

When, at sunset, he emerged, dripping, it was with the unalterable determination never in any circumstances whatever, to interfere with any animal that was striped and wore a bushy tail. He was just able to endure himself when after an uneasy and nightmare-haunted doze he resumed his journey. But he remembered that skunk for the rest of his life.

WEEKS passed before Steg regained his power of scent

sufficiently to distinguish anything from skunk—and by the

time he did so, he had covered a vast distance.

He had started originally for somewhere in the region of the Esquimaux Lake and his route had led him past the Great Bear Lake, south to the Great Slave Lake down to Athabasca. He was now in a country where any day he might blunder upon man.

Indeed, he had once attracted the attention of a couple of Indian trappers—two of the Frostiface tribe. But with a the intelligence for which these Indians are notorious, they did not interfere with him. He was too large a contract. Strictly speaking they did not take him seriously; for they encountered him on the morning after they had finished their last bottle of firewater in celebration of the birthday of one of them, and they attributed the appearance of Steg to the vagaries of the firewater.

Fortunately for those poor savages Steg did not notice them, and went lumbering away over a rise hot on the trail of a caribou bull which he had just struck.

The two Frostifaces had rather blearily watched him disappear. Then, glancing suspiciously at each other they said simultaneously, "Ugh! Heap bad medicine," and resumed their desultory vocations.

Neither believed that Steg was real—and so it befell that the honor of discovering the dinosaur fell to Mr. Angus M'Clump, of Icicle City, Saskatchewan. Icicle City was a collection of half a dozen log huts, five of which were uninhabited, their owners having evacuated them upon hearing from the railway company, in response to a petition signed by the whole population, that there was no immediate prospect of the company building a four-hundred-mile spur out to Icicle City for some time to come. So Mr. M'Clump had inherited the whole city. He dwelt in the largest of the cabins and used the others variously as store-sheds, fuel-supplies and so forth.

He was a grim old Scot of middle age, proof against all weathers and all whiskies. He was a very skillful trapper and was amassing a goodly pile of valuable furs. The appalling loneliness of his life did not disturb him, for he had a very good supply of whisky, a copy of the works of Robbie Burns, and an encyclopedia. He was a very level-headed man, and he was glad of this on the day that Steg, the dinosaur, came tottering feebly down the main street of Icicle City and collapsed with a deep groan on the very doorstep of Mr. M'Clump.

Angus was reading at the time. He had just come in from a three-day round of visiting a long line of traps, had eaten well, piled up a big fire, stimulated himself a little and had settled down to Robbie Burns when he heard the groan with which the suffering Steg announced his advent.

"Losh! But whut's wrang the noo?" said Mr. M'Clump in accents of surprise. He put down Robbie, slipped on his furs, for it was now December, took his rifle, for he was a methodical man, and stepped out of doors.

For a brief moment Mr. M'Clump thought he was seeing visions. Then, as Steg groaned feebly, he perceived that he had to deal with facts. "Ah, the puir wee beastie!" said Mr. M'Clump sympathetically.

For Steg was ill—obviously ill. Fresh from the Jurassic age, he had come up against difficulties and dangers which had not existed in the remote period in which he had been born.

Steg had courage and to spare. He did not fear any dinosaur that lived, though naturally there had been plenty he would not have gone out of his way to meet.

The colossal eighty-foot long Atlantosaurus could not strike terror into the heart of Steg; nor did he greatly fear the Brontosaurus in spite of that creature's sixty feet of solid bulk. The vast Cetiosaurus caused Steg no loss of slumber, and though he did not care much for a full-grown Triceratops (whose three-horned skull alone averaged eight feet long), nevertheless he did not abjectly fear one. The old dinosaur had a full knowledge of how to deal with these giants, had he encountered any; but strange though it may seem, he had no chance whatever with a modern complaint. The fact was that Steg was suffering from a bad touch of the colic, or in simpler, homelier words, he had the stomachache.

Forty millions years ago stomachache was practically unknown—so that when it struck the unfortunate dinosaur a few days before he reached Icicle City, it struck him with the full force of a complete novelty, and crumpled him up rather thoroughly.

His figure, too, was a great handicap. Had he been shaped like a greyhound, which graceful animal does not appear to possess any stomach worth writing about, it might have gone more easily with him. But he was equipped with rather unusual prodigality in the matter of tummy, and consequently the colic had room in which to work. Steg, in short, was suffering from about forty cubic yards of stomachache, which is a great deal of stomachache to contend with in a cold country.

He lowed feebly at Mr. M'Clump, as the old Scot strolled right round him, in search of a probable cause of the gigantic animal's trouble.

"I dinna ken what's wrang wi' ye, laddie," said Mr. M'Clump. "I am not verra well acquent wi' the pains and perplexities o' such beasties as ye are. But I will mix ye a little prescription of my ain devisin'!"

He retired to his cabin and took a jar of rye whisky, strong enough to start hair sprouting upon the totally bald. He added to a gallon of this a half-gallon of practically boiling water, a tin of mustard, a pound of cayenne pepper and a generous touch of everything else he had which possessed heating properties. Then he poured the steaming mixture into a large pan and bore it out to the shivering dinosaur.

Steg inhaled the steam, and his dull eyes brightened a little. He raised his head and feebly lapped at the terrible hell-broth. Then he lapped less feebly, and even less so, until finally he finished the pan with enthusiasm. He lay still for a moment, reveling in the generous glow which swiftly traveled down into his interior and chased away the colic as a forest fire chases away snakes. Then suddenly he staggered to his feet and stood for a moment, recovering visibly, his eyes fixed on the interested M'Clump.

"Eh, laddie, but ye came to the richt mon to doctor ye," said Mr. M'Clump, proudly surveying the sudden perspiration which broke out on the vast hide of the big beast. "Ye should be oot o' the cold, though."

He reflected for a moment, then moved away toward a big hollow surrounded by a dense, heavily timbered thicket, now covered with a deep drift of snow. Steg followed him, a faint sense of gratitude, and a vague hope that there might be some more of that warming invigorating broth, growing slowly in his heart. Under the guidance of the acute Scot the old dinosaur blundered deep into the big drift and there lay down and dozed off into a healthy sleep.

For some time Mr. M'Clump stood admiring him and ransacking his mind in an effort to classify him.

"Ye are no' a hippopotamus, and ye are no' a rhinoceros, baith o' which are wee timorous beasties compared with ye," he muttered. "Ye are no an elephant nor a mammoth, for ye would mak either o' them look like sma' heifers beside ye."

Dim recollections of long-forgotten picture-books came back into the old trapper's mind.

"Ye must be a—a deenosaurus. I will look ye up in the encyclopedia. Whatever ye are, ye are certainly a verra valuable piece o' property—and it would be canny to brand ye richt awa'."

Mr. M'Clump was a Scot, and that is tantamount to saying that he feared nothing on earth. He decided to brand Steggy without loss of time—while he was weak.

Among the few souvenirs he had brought away from Texas (where some years before he had gracefully failed as a rancher), was a "Triangle Dot Cross L" branding-iron. All property found with that weird symbol scarred in upon its hide might safely be regarded as the property of Mr. Angus M'Clump.

He hurried indoors and stuck the iron in the stove. It was weeks since he had seen a human being, but he was a cautious man, and being fully alive to the value of Steg, was in a frenzy of haste to get the poor colic-stricken survival of the Jurassic well and truly hall-marked before anyone else arrived.

A few minutes later he cantered across the snow to the sleeping monster, the white-hot iron at the ready.

He pressed it hard on the haunch which was nearest him. Instantly there arose a cloud of smoke and a very horrid odor of burning horn. But Steg took no notice. He had a skin at least eighteen inches thick, and long before the slight pain filtered down to his nerves, Mr. M'Clump had Triangle-Dot-Cross-L'd him in three more places, and was on the point of leaving him. He was just indulging in one last fond look at the mighty serrated back of his new acquisition when he heard a dry cough behind him. He turned like lightning, to gaze into the eye of a heavy repeating rifle which was held very steadily pointing at his heart by a short, fattish man dressed like a trapper, with a hard eye and a highly discontented expression.

"Put up your hands, you gol-derned cattle-rustler!" commanded the man with the rifle. "Up with them hooks, or I shore lets lead through you!"

Mr. M'Clump raised his heavy hands.

"Which you are took in the very act of the deed," observed the fat man. "And tharfore you have shore merited sudden destruction."

"What act? What deed?" demanded Mr. M'Clump furiously.

"The low-down ornery act of rustlin' that there maverick of mine," said the fat man.

"Yours!" said Mr. M'Clump incredulously.

"Stampeded off my location two months ago," said the fat man, "which I've been trailing the same ever since."

He was quite' obviously lying, and M'Clump knew it. But in those regions it is considered the height of stupidity to suggest that a man with a large rifle trained on one's breast-bone is a liar. So the Scot temporized.

"Where is your location?" he asked mildly.

"Up thar!" The man jerked his head toward the north.

"Do ye raise these beasties there, mon?"

"Thousands of 'em," said the man.

"Aye? An' what manner o' name have ye for sic beasties?" continued Mr. M'Clump.

The other hesitated—but only for a moment.

"Alaskan sawbacks," he said. "I raise 'em for export."

M'Clump shook his head sadly, forgetting his native caution.

"Losh, mon! But ye're a poor, daft liar!" he said. "Yon's a deenosaurus! I lookit him up in the encyclopedia while I was heatin' my brandin'-iron!"

"A what?" asked the other.

"A deenosaurus! He belongs to the Jurassic."

"Belongs to who?" asked the trapper, prepared to defend his quite unfounded claim.

"The Jurassic age. He is a survivor from the great Mesozoic epoch," explained Mr. M'Clump, quoting freely from his encyclopedia.

"Say, pard, who be them gents, anyway? Injuns?" inquired the stranger, looking a little dazed.

He lowered his rifle.

"I yields to superior education—and I throws in my hand, accordin' tharunto," he continued with a sigh. "I was minded to raise your bet on deenosaurus, stranger, and I thought you was jest plain bluffin' on Jewrasstic! But you got all the kyards in the pack. I resigns to you, and the chips is yourn!" He smiled sadly, his whole manner oddly softened. Then he burst out suddenly:

"But say, friend, what in hell is this yere beast, anyway? I run against his tracks in the snow two days ago, and I thought I was seeing hallubrications! I've spent most of my life down on the plains, and this is my fust year up yere sence I was a ornery little runt two foot high. He looked valuable, and I jest naturally claimed him, which same claim I now hastens to withdraw."

Mr. M'Clump warmed to the man for his frank confession, and became hospitable at once. The stranger's reference to him as a man of superior education had pleased him immensely.

"Mon," he said, "it's a black and profound mystery to me how yon beastie arrived in the Twentieth Century. He's no less than forty millions of years old an' maybe more! Deenosaurs have been extinctit these millions o' years. I tell ye, I found him lyin' on my threshold—like a foundling, mon—sore stricken wi' the bellyache. An' he's mine."

"Which same is shorely true, pard," commented the other, who had said his name was Lariat Smith. "And now yeh've roped and branded him, what is your next idees?"

"I'll advertise him for sale. There's many a millionaire would pay a fair price for him, d'ye ken?" Lariat Smith stared admiringly at Mr. M'Clump.

"I said yeh was a man o' superior education, which same I am free to maintain with hot lead against all comers," he said with a sigh, and reached for the whisky.

STEG awoke next morning feeling like a three-year-old.

Gone was that strange colossal pain, and in its place was a

voluptuous warmth. Small-brained though the big dinosaur was,

he nevertheless recognized Mr. M'Clump as his preserver and

benefactor, and when, not without caution, the Scot approached

him next morning, he fawned upon the old man like a dog. M'Clump

fondled his head a little, and when the dinosaur reached out to

gather in Lariat Smith, as he had been wont to gather in bears,

a sharp word and a quick pat on the head with a rifle-butt from

M'Clump conveyed to the gigantic beast the knowledge that Lariat

was to be exempt from his appetite.

So he quietly began to browse on the pine trees, which were plentiful enough in that neighborhood to keep half a dozen dinosaurs for a week. That afternoon Lariat Smith left Icicle City en route for civilization. He and Mr. M'Clump had come to a mutually satisfactory arrangement, and he was now bound for a place where he could issue an announcement to the world in general and millionaires in particular. Mr. M'Clump was to follow quietly on with the dinosaur.

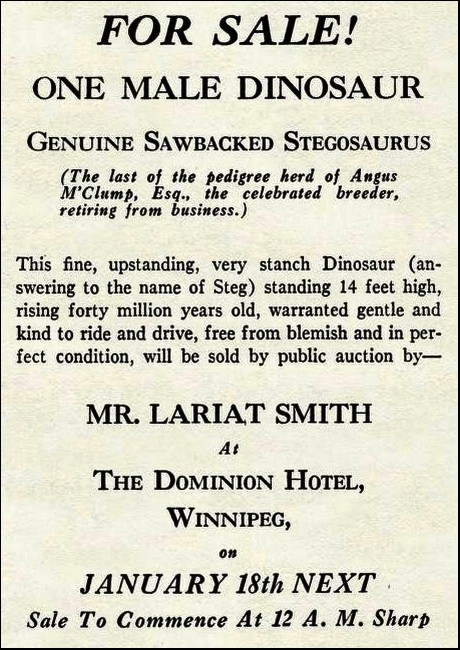

LONG before the approach of the Scot and Steg to the

nearest town was signaled, so to speak, the world had read

and grasped the significance of the announcement, reproduced

above, which was displayed strikingly in every newspaper in the

hemisphere.

This incredible announcement was accompanied by a picture made from an enlargement of a snapshot taken with M'Clump's pocket camera.

After the first gasp of amazement the scientists, museums, wild-beast emporiums, zoos, fairs, menageries and private speculators throughout the world settled down to compete. Mr. Lariat Smith took an office in Winnipeg and attended to his correspondence, having hired a temporarily stranded fiction-writer to supply the numerous reporters with facts.

Offers poured in.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars were offered, rapidly rising to millions; and francs, marks, rubles and yens were offered in amazing quantities. A famous comedian offered a half-million pounds sterling; the Umpteenth Battalion of the Welsh Fusiliers volunteered to accept Steg as a mascot. It was rumored that the British museum was contemplating making a firm offer of thirty pounds cash, but this was subsequently denied.

Long before the sale, however, the matter had risen into a region whither few could follow it—namely the region of American millionairedom.

For a time the figure danced upwards from one million dollars to ten million—but as all the world knew, that figure was meaningless. The whole thing now resolved itself into a very simple problem—viz: which of four people wanted to be the owner of the only thing of its kind in the world, for there were only four people rich enough to buy it. These were Mr. Johan D. Rockcellar, Mr. Henri Fourd, a certain celebrated meat-packer, and a skillfully unknown English coal-owner. The meat-packer stopped at twenty million. Mr. Fourd's last offer was thirty million. It lay between Johan and the English coal-owner.

Not till the day before the sale did Johan make any movement. Then he made the telegraph wires white-hot with a curt offer of fifty million dollars F.O.B.

Lariat Smith opened and read the message and turned to the representative of the British coal-owner, a gentleman named Isidor Moss-Gordon, and said briefly:

"Johan says fifty million. What about it?"

Mr. Moss-Gordon turned pale.

"Sixty million dollars is my last word," he replied.

Lariat nodded, and picked up the telephone, into which he uttered a few cryptic words.

"I'm getting through to Mr. Rockcellar," he said.

Swiftly came Johan's last word—seventy million dollars for the dinosaur.

Mr. Moss-Gordon waved his hands feebly.

"Let him have the brute," he said. "But if it hadn't been for the Excess Profits Tax—" he began darkly, broke off, took his hat and went away.

With a sigh of content, Lariat Smith settled down to await the arrival of Mr. M'Clump and Steg.

Late that night Lariat Smith was sitting in his office dreamily working out schemes for best investing his share of the profits, when the door opened and Mr. Angus M'Clump strode in.

"Hello, pard!" said Lariat delightedly.

Mr. M'Clump's only reply was to utter a most unmelodious groan and several dry sobs.

"Say, what's the matter, pard?" asked Lariat Smith.

"Aye, mon, it's a disastrous story," moaned Mr. M'Clump. "And I tell it to ye in few wairds! Mon, yon wee dinosaur is no more."

Lariat Smith leaped up. "D'ye mean he's dead?"

"Oh, aye!" said Angus. "He's turned into a fossil."

"Helendamnation!" was Mr. Smith's sole comment. "And I've just sold him to Johan Rockcellar for seventy million dollars!" He lost consciousness. Mr. M'Clump had already fainted....

EXACTLY how or why it had happened, nobody knew—but it

had come about quite simply: Mr. M'Clump had been at the very

point of starting away from Icicle City with Steg, who, still a

willing slave to his own gratitude, seemed as fit as a fiddle

and fresh as a kitten. Mr. M'Clump had just turned to lock the

door of his cabin when he heard a very peculiar sound behind

him.

He turned sharply, only to discover that the dinosaur had stopped, apparently frozen into a strange immobility.

Mr. M'Clump proceeded to examine the dinosaur closely, first with his hands, then with a hammer, and finally with an ax. But his investigations worked out exactly the same every time: Steg had turned to stone.

What strange freak of nature had caused this, it is impossible to say. But though the cause was and ever will be obscure, the effect was obvious—in solid stone.

There he was out there in the Saskatchewan snow—a perfect and complete fossil of a genuine Stegosaurus, looking as though he might have been dead forty million years —exactly as he should have been. And all around him in the snow were the tracks he himself had made in getting to the position in which he was now a fixture. Dark and inscrutable are the ways of fate in even the simplest of her operations....

Messrs. M'Clump and Smith came to their senses simultaneously, and staring at each other, they whizzed their hands around to their hip pockets—each withdrawing a big pocket flask, in search of moral support. Mournfully they drank a long farewell to the millions they would never have; and then, after a brief and hurried conversation, they arose and faded silently out of Winnipeg, en route to Icicle City, there to build a high fence round the stony Steg until such time as they could sell him to a museum or a collector of statuary.

Two months later they got a hundred thousand dollars for him from Mr. Rockstone Shelley-Chalk, the famous fossil-sharp of Wyoming—which, as Lariat Smith very truly said, was "shore some clean-up, anyhow."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.