RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

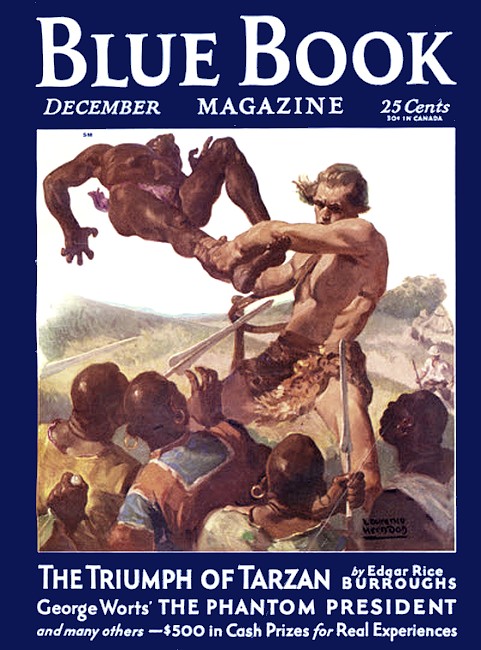

Blue Book Magazine, December 1931, with "The Golden Goat"

THAT poet, whose name and well-deserved fate has for the moment escaped the memory of the writer, was indeed possessed of the true vision when he indited these lines:

Consider the customs of the goat.

He toils not, neither does he spin,

He eats all day from morn till dewy eve—

And yet he's never more than bone and skin!^

He probably kept goats, and had studied them in their natural haunts. But however that may have been, it is certain that it was the custom so plaintively referred to in the foregoing verse which was the cause of Bill, the so-called Toggenburg goat belonging to Mr. Dennis Keohan, of Clay Lane, Grimeley, being turned out into a cold and unsympathetic world to earn his own living.

He had been procured by Mr. Keohan during the war period when meat coupons were more plentiful than meat, Mr. Keohan's naive idea being to fatten Bill until he was juicy, and then to knock him upon the head and construct from his valuable carcass a series of pies—pies being a species of nutriment of which Mr. Keohan was inordinately fond.

By the time Bill had been in the Keohans' back yard three months Dennis had learned the lesson which comes to most goat proprietors sooner or later. He was compelled to admit that his goat was unfattenable. And this in spite of the fact that Bill had eaten everything that had been put before him and much that had not. He had broken Bridget Keohan of the habit of hanging clothes on the line, for in one short day he had reduced the stock of spare underclothing of the family to so narrow a margin, that only with the greatest perturbation could they look forward to the coming cold weather— more especially as he had eaten half the coal-supply so carefully stored in the woodshed.

It would be depressing in the extreme to conduct the reader down a list of the various and more or less valuable articles laboriously acquired during their career by the Keohans and devoured by that appetite incarnate, Bill. Let it suffice to state that a time came when it was obvious to Dennis Keohan that he could no longer support a wife and family, and a goat. He had to choose between them. He decided on the day Bill ate the best feather-bed, which Mrs. Keohan had most unwisely put out in the sun to air during one of her great house-cleanings.

Lying upon an extraordinarily lumpy flock mattress that night, Mr. Keohan turned the matter over in his mind. He was a furnace man in one of the big Grimeley ironworks, and was not a person of ultra-refined character. He had come home tired, and after a colossal supper, had retired to bed at nine. In spite of a sneaking fondness for the goat, the flock mattress so worked upon Dennis,—lying wakeful upon the hard lumps,—that by ten o'clock he had decided to sell the creature.

Bridget Keohan occupied the next hour by reciting in an Irish monotone a precise specification of the devastation worked by Bill. She pointed out that he had eaten the wicker cradle, and she demanded to know whether Dennis was satisfied that his latest baby should sleep in a box; she reminded him of the price of woolen goods and requested him to inform her how he proposed to get through the next winter with one and a half pairs of pants which, thanks to that hungry spalpeen down in the yard, were all he had left; she spoke of similar complications to be faced by the children and herself—and of many other things.

By eleven o'clock Dennis had decided to kill the "cratur" himself—and not to hurry over it, either. Bridget then slept, but the flock lumps worried the weary Dennis so fearfully that at midnight he arose with an all-Irish exclamation and went murderously downstairs to the woodshed for the ax. Things looked black for Bill, very black indeed.

The old ruffian saw Dennis come forth from the woodshed with the hatchet gleaming in the moonlight, but it did not disturb him, for he liked the furnace man.

He looked up into the face of the Irishman and said "Baa!" in a friendly fashion, as one would say, "Well, old man, they're all against us, but we can bear up all right. Huh?

The Irishman's rage suddenly evaporated; dropped the hatchet.

"Ye blarneying soft-sawdherin' old baste!" he muttered, and hesitated "Oi'll cut the liver out yez, ye omadhoun!" he said, and released Bill from the tether rope he had often gnawed through. "Ye have the pants ate off me ye black-hearted divil, an' Oi'll skin yez alive!"

But instead of carrying out these gory proposals he opened the back gate, shoved the old goat through it, and started him on his travels with a very mild kick.

"Good luck go wid yez, ye spalpeen!' said that good-hearted mass of Irish contradictions, Mr. Keohan. He banged the gate to, and returned to the lumpy bed.

Bill stood for a moment in the moonlight, smiled cynically, and then moved off. In a way he was reluctant to go, but he felt it was for the best. He liked Dennis Keohan and did not seriously object to any of the family—but the food had been poor, on the whole.

He went thoughtfully through the silent town, seeking what he might devour.

At the corner a dog—a stranger to those parts—sought amusement in chasing the goat. He failed to find it, for Bill butted him dizzy before he knew what had fallen on him,

Then the old goat strolled leisurely on.

At about ten o'clock the following morning he might have been seen in the strawberry-bed at the charming suburban residence of Mr. Darnitt-Hall, a local magnate. It was rather too late in the season to find many strawberries, but what there were tasted good. Some people were playing tennis on the lawn adjoining, screened from the strawberry-bed by espalier pear- and apple-trees.

Collecting a few extremely useful apples en route, Bill the goat strolled across to watch the game. He came out onto the lawn to discover a very charming young lady playing tennis with a beautiful young man, so very spruce in white flannel and so very tender and affectionate in manner that he could only be the fiancÚ of the young lady.

Bill watched the game for a moment It was pretty poor tennis, and Bill did not understand it, anyway. So he turned his attention to certain articles lying on a seat close to him. These were a garden hat, a pair of soft gloves and, lying on the gloves, sparkling in the sunshine, was a ring—a diamond-and-ruby ring.

It looked very luscious to Bill, whose previous experience with these flashing gems had been extremely limited. But obviously anything that looked so pretty was bound to taste good—so be reached out for it.

He bolted it just as the players simultaneously caught sight of him.

A shriek went up that startled even the iron-nerved Bill.

"Oh! He's eaten my ring, George!" screamed the girl.

George, who had had the bliss of paying for that ring, hurled his racket at the goat and followed it up with long, springy bounds.

The handle of the racket took Bill by the side of the ear and jarred his brains quite considerably. He decided to leave. So he left.

George was six inches behind him as he leaped the hedge, and landed on the pavement almost at the same instant as the goat.

But it finished there. The young man was a good runner—fast and painstaking and with a good action. Bill, on the other hand, had no action nor style, but he could travel. And he did travel.

There was quite a number of people about and George raised a thrilling hue-and-cry which followed the old goat clean through the town. But by dint of some very skillful dodging he won clear at last—though he did not shake off the more tenacious of them until he was two miles out of the town, heading down the road—little used except by the city's garbage-carts—leading to the rubbish-dump, a place of excessive dreariness down among the marshlands adjoining the river.

Vastly surprised at all this fuss over a mere speck of sparkling stuff—tasteless and hard as it had been—the goat pushed on until he was lost to view among the hillocks and undulations of the big rubbish-dump.

He found a dry spot in the sun and settled down to rest for a little after his spasm of activity.

THAT long, determined and bitter chase had startled and

upset the animal. He had been chased many times before in

the course of his extremely checkered career, but never

more than perhaps a few hundred yards and that only by

children. Those pursuits had been very different indeed

from this.

Hundreds of people had chased him this time—and they had meant business, too. Bill, stretching out like a hare, had realized that clearly enough. They had thrown things—large, hard, heavy things. One man in a big motor had tried to run over him; only by shooting up an alley had Bill dodged the car.

Lying safely hidden in the rubbish-dump, the goat puzzled things out.

"They meant getting me this time," he mused. "They don't seem to care about me in that town. I don't reckon my life's over-and-above safe back there! Gone mad, most of 'em, I reckon, I guess it'll be a long time before they see me back in that town! They're crazy up there, that's what's wrong with them. I'll camp here for a bit. It's quiet and it looks as if there ought to be some useful meals knocking about somewhere. And now I'll take a bit of a snooze."

He proceeded to do so, blissfully unconscious that he had, lodged in his internal mechanism, an engagement-ring worth at least fifty pounds; that the printers were already working on an advertisement relating to him and the ring for insertion in the local evening paper; and that he was about to embark upon a highly exciting period of his career.

At ten o'clock that morning Bill had been worth perhaps four shillings—now he was worth fifty pounds and four shillings. His figure had risen, though he did not know it. Also his number was up—at least it looked uncommonly like it.

Bill spent the early part of the afternoon exploring the rubbish-dump. He liked the look of the place. It appealed to him; it was like the Keohans' back yard, multiplied a few thousand times. From Bill's point of view it was a fine place—though from the view of anything but a goat, and kindred spirits, it was a Hades of a place.

What had once been a riverside stretch of dull, dank marsh,—sparsely covered with a species of hairy vegetation which it would be flattery to describe as grass,—had now by the operation of time and the labor of garbage-collectors become a wide acreage of muddy waste, street-scrapings and refuse, beaten hard by many rains and much extremely indifferent weather. But this great accumulation had not been leveled. On the contrary, it was a place of hillocks and little valleys, a dreariness of fantastic mounds and odd, unexpected little gulches. No trees grew there, though it did not lack for bird life. Cats, too, came there, and occasionally there were dogs.

It was this grisly region which Bill explored when he awoke, some hours after becoming valuable.

He liked the place—he liked it immensely. He could not call to mind any place he had ever liked so well. It was retired, and though perhaps it would not have seemed tempting to a goat accustomed to meadows, it was a species of Paradise to a goat accustomed to back yards. It was indeed a huge and excessively untidy back yard, and as such could be depended on to afford an ample though possibly varying dietary which was extremely satisfactory—for there were two requirements the Golden Goat looked for in his food; variety and tastiness.

He discovered that the hillocks were bounded on the south by the black and heavy river which flowed through Grimeley, passing the hillocks and so through a desolation of swampy ground to the sea which was the boundary of the salt marshes that surrounded the hillocks on the east, north, and all of the west save for the hard road down which the city garbage-men brought their accumulations.

Yes, it looked good to the goat, and he decided to settle down in this highly-flavored fastness for life.

He was serenely unaware that that hard cold lump which seemed to be permanently fixed in his interior was potent with possibilities—especially so as none came to disturb him or molest his solitary reign over the hillocks that afternoon; when eventually he settled down for the night he was an extremely contented goat.

But had it been possible for him to peep into a tumbledown inn called the "Wild-fowler's Arms" that huddled down on the riverside just outside Grimeley, at eight o'clock that evening, and to have understood the conversation of the host of that inn and a large, gnarled old man who had called in for a little stimulant, the Golden Goat might have rearranged his plans with some considerable care.

For the landlord had just read an advertisement from the evening paper to the customer—one Mr. Henry Diggs, a wild-fowler who dwelt alone in a species of rabbit-hutch on the riverside not far from the hillocks. It was many years since wild-fowl in any quantity had come to the estuary, but the ancient Mr. Diggs was open to offers—eels, rabbits, wreckage, and so forth.

"Read it again, Guv'nor," said Mr. Diggs, "—that bit about the goat."

And obligingly the landlord read—as follows:

TEN POUNDS REWARD

Will be paid to any person recovering the

DIAMOND AND RUBY RING

Grimeley, on the 20th August by A LARGE BLACK-AND-GRAY GOAT with one horn missing. The animal is believed to be ownerless and when last seen running in the direction of the corporation rubbish-dump. The goat does not appear to be of any value and Mr. Darnitt-Hall is prepared to pay cost of extraction of the jewelry, and burial of the goat.

Mr. Diggs listened in silence, his face brightening.

"Thank-ee," he said as the landlord finished. "That's a queer set-out, to be sure."

"It certainly is that, Henry," admitted the landlord.

Thereupon Mr. Diggs took his departure—heading for his shack and his weapons,

"If that there one-horned animal is anywheres around the mud-heaps at daybreak tomorrow, I'll lay I'm ten pun' better off afore breakfast," he muttered as he went.

THE Golden Goat rose punctually at the first peep of

day. He was desirous of investigating a certain El Dorado

of cabbage-stalks he had come upon late the previous

afternoon.

It was a dank and foggy day and he looked almost as big as a jackass as he loomed through the dense fog. But Bill was not worrying. He wore a hide that was waterproof, and he felt like a boy who has found an orchard full of fruit, miles from the nearest house.

He immediately had one slight shock. There came a muffled roar from somewhere out to sea, faint at first but increasing. Bill climbed a pinnacle the better to see what caused this roar, and before be got his balance a Thing swooped down out of the fog like a thunderbolt, Startled and horrified, Bill quit that pinnacle before be was ready and landed in a pool of mud that half choked him, He crawled out looking rather like a mud-crab, and blinked after the sea-plane.

"Well, if that's a hawk," he told himself, "—a hawk I ain't no judge of eagles!"

The airplane vanished, and Bill pulled himself together.

"That bird could eat a goat for breakfast and then have room for a couple of cows," he said, his beard quivering. "I—"

Bang!

A hail of lead hissed into the mud as the goat leaped frantically into the air—a vertical bound that nearly broke his back. He had caught the flash of the gun just in the nick of time. He landed and vanished.

The stealthy Mr. Diggs, swearing unwholesomely, arose from his ambush and reloaded. Then, through the thinning fog he began in earnest his quest of the Golden Goat.

Some fairy-godmother-goat must have watched over Bill that day—at any rate for the first hour or so, Mr. Diggs loosed off at him no less than three times, missing him by no more than a hairsbreadth on either occasion, thanks mainly to the frenzied excitement which the chance of bagging ten pounds in a single shot aroused in the murderous-minded old man. Then it dawned on the animal that Mr. Diggs seriously designed to slaughter him.

So, reluctantly, the Golden Goat left the hillocks by the main road. He had not traveled more than a hundred yards along that road before he met a convoy of garbage-carts making their first trip out.

The men recognized him in a flash.

"Hoy!" bawled the first one, hastily dismounting, a brick in each hand, "Here's that blankety goat what et the jewelry!"

They charged, to a man, behind a perfect hail of missiles.

But Bill was "getting wise" to the game. He dodged and made a wide detour across the saltings, easily shaking off his pursuers.

"I seem to have got myself kind of disliked since Keohan slung me out," he mused. "Wonder why?"

Pondering, he edged round again to the road, stared down it—and edged back, for there were quite a number of people straggling down toward the hillocks—and most of them carried guns.

"Must be a shooting-match going on somewhere," said the Golden Goat to himself uneasily—for he had a shrewd idea as to who was expected to provide the body.

He decided not to use the road, after all; he thought on the whole that he preferred the ditch. It was softer to the feet, for instance.

So he quietly dropped off the road and disappeared into the dyke at the roadside. He wormed his way across this, an unwholesome object of mud and weed—which, uncomfortable though it was, camouflaged him excellently.

He crept out of the dyke and scrounged himself into a tangle of reeds until he was wholly invisible.

There he waited until the shooting party had straggled past, talking excitedly. All the riffraff of Grimeley seemed to be taking a morning off—at least everyone who could get hold of a lethal weapon that was or had once been a firearm. And, though Bill could not follow much of what they said, he heard the words "goat" and "blank goat" and "dash-blank goat" repeated so many times and in such a menacing manner that his suspicion as to the patty they were in search of grew into a certainty.

"They're after me, sure," mused the Golden Goat, lying low in the reeds. "I guess I must've offended somebody!"

He heard the voice of Mr. Dennis Keohan raised in threatening accents.

"The goat is mine," Dennis was announcing. "An' there'll be throuble for thim thot slaughters me little Bill widout me permission. An' all jool'ry found in the goat is my property! Anywan found stealin' joolry out av my goat will be handed over to the polis!"

The voice of Mr. Keohan went trailing away down the road to the mud-heaps—and the Golden Goat lay low, excessively low. It would be incorrect to state that he had understood every word he had overheard said about him—but he had understood enough to realize that the Wild was calling him and in no uncertain voice. He understood that and was prepared to obey the call if only folk would let him,

SO he hung on in his retreat until the traffic had

dwindled a little. Then when a cheerful silence from the

roadway seemed to indicate that the coast was temporarily

clear, he peered out.

Well away to the left he saw a swarm of little black figures systematically searching the rubbish-dump, but the roadway appeared deserted.

"I guess it's up to me!" said the Golden Goat, and forthwith swam across the dyke, skipped up the bank and onto and over the road. He shot swiftly across toward the river and without hesitation plunged in and swam across.

A bargee, reclining on his vessel with a pipe, heard a splashing and looked over the side.

His eyes fell upon Bill and he started.

"Well, strike me beautiful!" he ejaculated, apparently forgetting that the age of miracles was past. He rubbed his eyes—and the Golden Goat spurted.

"Why, it's that unprintable goat!" he shouted, and darted into his den, appearing a second or so later with a gun. Bill dived like a trout. He had never dived before in his life, but something seemed to tell him that now was a good time to start.

He came up almost out of range and by the time the bargee had spotted him he had gulped a few cubic feet of air and dived again.

When he scrambled out on the far bank he was out of range,—though the bargee wasted a charge on him,— and half-an-hour later he was walking at leisure and alone in the green lanes of the countryside well to the south of Grimeley.

The chances of Miss Darnitt-Hall for the recovery of her engagement-ring were growing remote and slender.

ALL that afternoon the Golden Goat reveled in the sunny

lanes, eating what he considered real food—such as

cow-parsley, docks, brambles, moss, ivy, and occasionally

grass.

He spent the night in the lanes and next day moved on southward, keeping instinctively to the byways.

It was at midday that be made the acquaintance of Mr. Henry Slocum.

The Golden Goat came upon Mr. Slocum unexpectedly as he rounded a bend in the lane, and with that instinct for which a goat of real experience is remarkable, he realized at once that here was a kindred spirit. Mr. Slocum was reclining upon a bank in the sunshine. He had removed his boots and he was engaged in slumber. He wore one red sock, darned at the toe with green wool and not darned at the heel at all, and one black sock with white rings round it.

The Golden Goat sat down and surveyed Mr. Slocum. He did not know that the gentleman was a tramp, but was instinctively aware that he was not one who is shackled by convention.

It is impossible to say just what it was about Mr. Slocum which charmed the Golden Goat. He was not an attractive man; but then Bill was not an attractive goat—which may account for it. However that may have been, when Mr. Slocum awoke with a violent start an hour later the first thing his eyes fell on was the face of the Golden Goat.

"Hullo, mate!" said Mr. Slocum in a friendly way. "How's things?"

It may be that Mr, Slocum was feeling the need of a friend, or it may be that he considered Bill worth a few shillings.

He certainly met him in a spirit of welcome. At least he did not throw anything at him and he seemed not disinclined to talk to him. Indeed, he carried on a long, though entirely one-sided conversation with the goat throughout the whole of the decidedly scratch meal which he produced from his bundle immediately he woke.

The result of which, briefly, was that when presently Mr. Slocum, having replaced his hat upon his extremely close-cropped head, his boots upon his brightly socked feet, and generally tuned himself up for a move, he began, as he expressed it to the Golden Goat, to "throw his feet" along the lane, Bill, by pressing invitation, followed him.

It was a perfect example of friendship at first sight and probably would have resulted in a long companionship had the Golden Goat been less valuable.

But it was not to be. George, the fiancÚ of the unfortunate Miss Darnitt-Hall, did not lack talent or initiative. Also he was the proprietor of a high-powered two-seater, and, within a few minutes of hearing that Bill had been seen crossing the river George, was raising large quantities of dust on all the local roads south of the river.

So just as Mr. Slocum and the Golden Goat settled down to tea on the bank of a byroad a few yards from its junction with the main road, they were interrupted by the intrusion of a big gray two-seater which idled quietly in from the road and pulled up.

"Can you tell me the way to Arbury Common, my man?" asked George casually.

Mr. Slocum arose with a bow. He was not without talent in his own way.

"Arbury Common, My Lord?" he said. "Certainly!" He had about as much idea as to where Arbury Common was as had Whang Poo, the joss-stick seller down Ming Street, Canton.

The Golden Goat looked on uneasily. Why he was uneasy he did not know. He did not like the look of George and he wished that Mr. Slocum was not so prone to gossip with any passing stranger.

Mr. Slocum gave a detailed and elaborate account of the best and quickest way to Arbury Common and accepted a half-crown gracefully.

"That's not a bad goat you've got there," said George, apparently noticing the Golden One by accident as he turned to his steering-wheel.

"No, My Lord. He's a thoroughbred Nubian," said Mr. Slocum.

"Thoroughbred, eh?"

"I bred him myself," said Mr. Slocum calmly. "I took a prize with him as a yearling at the Redruth Goat Exhibition, My Lord. That was before I was ruined," he added sadly.

"You wouldn't care to sell him, I suppose?" said the diplomatic George.

A sudden light appeared in Mr. Slocum's eye.

"It would break my heart to part with that little goat, My Lord," he said, adding hoarsely as George turned to his wheel, "—for anything under twelve pun—or say ten."

George looked hard at Mr. Slocum.

"Now, look here," he said crisply. "I'll give you ten shillings for the goat. Will you take it or leave it?"

"I'll take it, My Lord," said the tramp hurriedly.

But as he reached for the money a sudden sense of danger thrilled the Golden Goat. He no longer liked Mr. Slocum; he had been mistaken in him. He turned to jump the hedge—but he was too late. Mr. Slocum hurled himself bodily on the old goat. George leaped out of his car and joined forces with the treacherous Slocum.

It was soon over. Two determined men are a great handicap to a goat and it was only a few seconds before Bill was prone in the dust with Mr. Slocum, grimly determined not to lose the ten-shilling note already safely secreted in an inner pocket, clutching his legs.

"Have you got a bit of cord on you?" asked George. "Thick string will do—just enough to hold him until I can get him to the butcher's."

Then, even as Mr. Slocum fumbled in his ragged garments, a newcomer appeared with a singularly penetrating Irish yell. None other, in short, than Mr. Dennis Keohan—who, mounted on a rusty bicycle, also had been scouring the roads for the Golden Goat. It was a hot day, and Mr. Keohan had clearly been struggling manfully against a painful thirst.

"Ah, ye have found me little goat, sor," he said. "I thank ye—an' I'll be after takin' him home."

George stared. "What? I've just bought the goat from this gentleman. It's my goat now, my man!"

The ordinarily peaceful countenance of Mr. Keohan suddenly underwent a strange and terrifying change.

"Phwat!" he shouted. "Are ye tellin' me I don't know me own little goat?"

His face flushed, and his great hairy fists balled up. Mr. Slocum rose abruptly and soared over the hedge like a bird. Dennis Keohan evidently meant to fight—and Slocum did not care for fighting. He ran.

"Ye black-hearted thafe!" yelled Dennis—and turned to recover his goat. But the Golden Goat was gone too. They had an admirable view of his hind feet as he zoomed upward over the other hedge—also like a bird.

There was a copse about sixty yards away—and Bill was in that copse before either George or Mr, Keohan were over the hedge. He stopped for one fleeting instant on the edge of the cover to glance back,

Mr. Keohan and George were not even pursuing him. They were quarreling furiously.

"You damn' fool of a crazy Irish biddy!" George was shouting madly. "I'd have given you a tenner for the one-horned brute—"

With a sardonic grin, Bill disappeared into the thicket.

If ever you chance to be in the New Forest—and are very lucky—you may one day catch a glimpse of a large, one-horned black-and-white goat, feeding some distance away, in company with a little herd of lady goats. It will not be worth your while to try to get close to this unicorn—for no man has ever been known to get nearer than a hundred yards to him, since he came to the Forest.

And, though the New Forest folk don't know it, he is the only animal in the Forest that wears jewelry. It is a diamond-and-ruby ring which he wears, and he wears it tucked away in a little nook which it has worn for itself somewhere down by the base of his windpipe.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.