RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

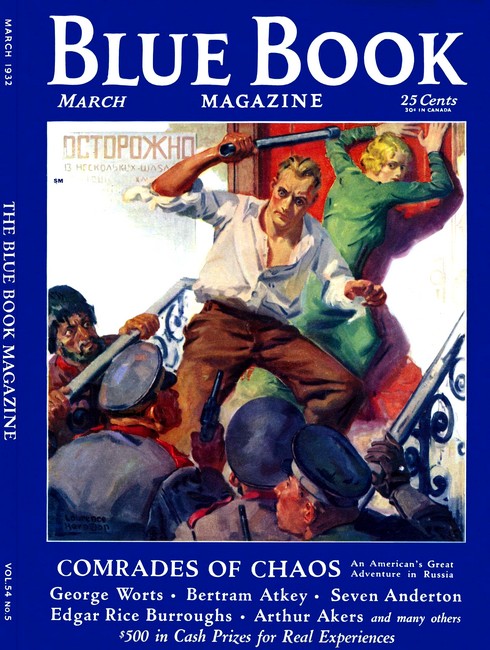

The Blue Book Magazine, March 1932, with "The Call of the Wildwater"

THE waters of the lagoon encircled the island like a garter of pale green silk round the—er—that is to say, the waters of the lagoon stretched like a sheet of pale green silk. Round the island, naturally.

In that vast expanse of sea there was nothing visible to the naked eye except millions of tons of water and coral, myriads of leaping fishes that flashed in the brilliant sun-fire like jewels falling in silver spray, hosts of tropical birds, their offspring and relatives, thousands of albatrosses, a quantity of frigate birds, a few coveys of Mother Carey's chickens, the remains of a wrecked schooner on the reef, and the coral island itself, some five miles by twelve in extent. Beyond these things nothing was visible.

Nor was there an echo of sound to be heard in that lonely and bitterly desolate spot except the everlasting thunder of the surf on the outer reef, the organ-like drone of the trade-wind, the loud dry rustling of the foliage of the palm trees, the deafening din of the birds and the splashing of the leaping fishes. Save for these sounds the place was numbly silent.

And then he came—silently, as was his way. At one moment he was not there. One could have sworn to it with absolute certainty—he was definitely and decidedly not there. Next moment he was there. Thus: he wasn't—then he was. It was like that. He always moved like that. First in one place—then in another. How he did it is more than I can tell you; it is one of the secrets of the wild.

But, sure enough he was there—staring out to sea with an expression which can only be described as wistfulness upon what, for lack of a better word, might be termed his face. There was in his greenish-gray eyes something of the look which a famished jackass bestows upon a bed of thistles growing halfway up a perfectly perpendicular cliff—a yearning.

For fully ten minutes he stared, motionless, at the mighty expanse of sea beyond the outer reef—so motionless that he might have been carved out of granite by a sculptor, a lunatic sculptor with a cheap chisel.

Then, turning abruptly, he went prowling along the lagoon, his gaze ever turned to the sea. Thus tigers prowl, though in a somewhat more abbreviated manner, along the bars of their cages.

The smaller denizens of the lagoons fell fearfully back from him as he approached them, for they knew him of old in these moods.

In this they exhibited a singular degree of common sense. It does not appear to be conclusively proved whether fishes actually think or whether we only think they think. I will now settle this matter. They think. This statement requires proof. I will provide it. The fishes of the lagoon fell back from the green-eyed prowler because he was what he was. And what he was, was a forty-five-foot spotted sea-serpent, in a villainous temper and at war with all the world—except one man, his master.

He was traveling slowly, with perhaps twenty feet of him out of water. His utmost speed, with only twenty-five feet in the water to propel him, was not more than, say, forty miles an hour.

Occasionally he stopped, stretched his head out over the reef and whined piteously, pawing the sharp coral with some of his foremost fins—gingerly, because he was soft-skinned and the coral edges were like saws.

As he came to the place from which he had started his circuit he laid his gigantic flat head down upon the surface of the water, and gave vent to a howl that was like the howling of a pack of wolves.

But the howling stopped swiftly as a man issued from a palmetto shack built under a clump of coconut palms and, clothed only in a ragged shirt and trousers, came racing down the beach, shouting, and shaking a dog-whip at the mighty beast.

Evidently he was furiously angry.

"Shut up—shut up!" he bawled, as he cracked the whip with the report of a pistol-shot. "How many more times have I got to tell you about—"

Here he broke off abruptly, turning to stare seaward where, suddenly, on the outer side of the reef, the head of another gigantic sea-serpent rose dripping from the sea—that of a female.

She lifted at least twenty feet of herself out of the sea, and staring toward the lagoon, began to moo plaintively.

Instantly the head of the big male in the lagoon towered aloft and he softly returned the love-note of the new arrival.

For some time the man on the beach watched them with sympathetic eyes. He was quite an ordinary person,—obviously a shipwrecked sailor, very ragged, and profusely hairy. His whiskers and hair and beard were like a red cascade falling over his head, face and shoulders.

His anger died out as he watched the two sea-serpents, and he shook his head slowly.

"You can howl, Spot, old man, howl till you're black in the face—and your lady friend can moo till her tonsils are swollen—but, as far as I can see, you're a prisoner in this lagoon for life—same as me. The only way you'll ever get to the open sea is by crawling across the coral, and you'll cut yourself to ribbons if you try it—you being so soft-skinned, son!"

He was right. The facts in the case of "Spot," as the man had named the huge beast, were briefly as follows:

SOME ten years before, when Spot had been practically a baby

sea-serpent, no more than perhaps twenty feet long and no bigger

round anywhere than a nine-gallon cask, he had swum through the

narrow channel through the reef dividing the lagoon from the

outer sea. He had found huge masses of his favorite seaweed

there, and he had lived luxuriously in the lagoon for nearly

eighteen months before he felt the call of the wildwater. Then he

had headed for the channel with the intention of going out to

sea—and it was then that he had received the shock of his

life.

The channel was too small!

While the young sea-serpent, feeding heavily upon the succulent and nourishing seaweed, had been steadily growing huger, the industrious coral insects had been working with extraordinary diligence. They had reduced the size of the channel by half, while Spot had increased his bulk by fully a quarter.

Had he been a thick-skinned sea-serpent this would not have mattered—it would have been merely a matter of a minute or so to come out of the lagoon, writhe across the belt of coral and so into the sea. But, like the sperm whale, his skin was astonishingly thin and tender, and, unlike the whale, he did not possess an armor plating of protective blubber under the skin. The soft-skinned sea-serpent loathes and dreads contact with rock or coral or anything sharp; thus, since his every instinct revolted against the inevitable dozens of wounds and bleeding to death which any attempt to crawl across the reef would bring him, the unhappy reptile was, indeed, as his master told him, condemned to live his life out in the lagoon—or, at any rate, until such time as the channel became wider or the tide rose sufficiently high on the reef to enable him to swim for it. Neither was a very probable contingency.

And what made this little tragedy of the wild more painful for the unfortunate serpent to endure, and more distressing for his owner—for so the shipwrecked mariner chose to describe himself—to witness, was the fact that recently a feminine sea-serpent had appeared off the reef, and, the two creatures clearly possessing an affinity, she came daily to call plaintively for the imprisoned Spot. The mating time for sea-serpents was long past, but so strong was the mutual attraction of the two that now never a day passed without the interchange of, so to speak, vows and protestations of everlasting fidelity.

"It's tough—it's very tough!" said Abner Clarke, as he pushed the hair out of his eyes and watched the movements of the two sea-serpents. "For it ain't as if sea-serpents was anyways plentiful. There they are, only a few yards apart, but they might as well be miles. They're fair crazy for each other. But she's free and he ain't. She's got all the seas of the world afore her and he's only got this measly lagoon. Why, damme, it's jest like me and Mrs. Lilygreen. There she is, back in Cardiff, free to roam the whole earth and the waters thereof, and here's me locked up in this everlasting island!"

He thought hard.

"Of course, the difference is that Spot ain't got much to fear from no competitors. Sea-serpents is undeniable scarce, and mebbe old Spot is the only gentleman serpent of her own class and size she's ever met. More'n likely he's the only one in the world. Whereas in my case, there's no doubt thousands of sharps always scrounging into Mrs. Lilygreen's homey little pub, for her to pick and choose from. It's easy enough for her,"—he jerked his tousled head seaward—"to be true to Spot—the only one of his kind in the world. But how about me? After all, all he needs is a drop of deep water over the reef and he'll be free. Or else the tide might tear down a slab of coral in the channel. It's only a question of time, with him! But how about me? That's what I want to know!"

He was gradually working himself up.

"What I want is a ship at least to take me off. And it might be a million years before any ship comes near here! But I don't go mooing and bawling about the place day in and day out, waking folk up and making a reg'lar damn' nuisance of myself. There's no sense in it. It's ridic'lous and selfish. And it's ungrateful, coming from Spot—what I brought up, you might say, by hand, from the time he was no more than a mite twenty foot long! It's ridic'lous and selfish, and I'm damned if I'll stand any more of it!"

He concluded his soliloquy with a shout that startled the sea-serpent.

"Shut that row, you Spot, d'ye hear?" shouted Mr. Clarke, and Spot obediently fell silent. Receiving no further reply to her callings, the female sea-serpent presently relapsed yard by yard into the sea, and with a final bellow of love disappeared, while Spot turned and swam slowly back to his master.

There was nothing novel or unusual in this—it was merely the regular program enacted at every dawn for the past six months.

The well-trained, and in many respects, affectionate creature knew that what Mr. Clarke wanted was a fish for breakfast, and a lobster for lunch. Long ago Spot had been trained to select meals from among the denizens of the lagoon for the sustenance of his master.

This he proceeded to do at once, and having speedily placed a fine fat fish and a vast lobster on the beach at his master's feet, and received an affectionate pat upon his huge, ham-shaped head, he turned away to attend to the matter of his own breakfast.

Mr. Clarke watched him go.

"That there animal ain't by any means the animal he was," said Mr. Clarke, shaking his head sadly. "Not by no means whatever he ain't so. He's fretting ... There was a time when that there little snake was quite willin' and content to play about in the lagoon, as merry and innocent as a little eel, in a manner of speakin', but now he's dull and changed. He's a good serpent, and a honest, hard-workin' serpent—dunno as anybody could want a better sea-snake than what old Spot is—but he's losing flesh, and his heart ain't in his work. He's pining and his heart is breaking."

Then with one of those swift changes of feeling to which ten years of loneliness on the desert island had rendered him so liable, Mr. Clarke switched round again.

"But, blast him, he ain't the only one! Why can't he bear up—the same as me? Aint I pining, and ain't my heart breakin'? Milly Lilygreen never comes off the reef and calls out to me and paws at the coral with her fins, do she? Well, then—I reckon that there three-starred old selfish water-worm's got the laugh on me, ain't he?" muttered the mariner as he strode up to his hut of wreckage and palm leaves.

"Parading up and down the reef, bawling as though he was the only one with troubles in the world! There's others, I s'pose," he concluded, administering a back-handed clip to an aged monkey (salved from the wreck) in the hut, whom he caught with its hand groping in a chest (also salved from the wreck), a slap which convinced the ape that there were indeed others with troubles to bear in the world.

BUT this is not, strictly, the story of Mr. Clarke and his

other friend and companion, Cesar, the ship's monkey, and the

only other survivor from the wreck. It is instead the story of

the call of the wildwater—for so, in an unnatural nature

story naturally the sea should be called—to the captive

sea-serpent; the story of how this inhabitant of the wildwater

instinctively went back to its own place, deserting in that great

call all its man-taught habits and customs, returning again to

its grand heritage the sea, to roam in company with its mighty

mate the lady sea-serpent those huge jungles of seaweed, and

those trackless, illimitable deserts of slimy ooze deep down upon

the ocean floors....

Let us return to him where, having fed, he lies on the bed of the lagoon, watching with the expressionless, patient eyes of a captive beast, the all-too-narrow passage or channel between the sharp coral rocks, which, were it only three or four times as large, would be large enough to permit of his escape from the lagoon-prison.

He was restless. At times he would be lying perfectly still, staring at the gap; then he would start into convulsive motion so that the green water boiled under the lashing of his great tail; then he would go nosing feverishly at the coral barrier, only to relapse again into quietude and his eternal watching. The serpentess had gone away for a space ...

There had been a time when he was forever trying to squeeze through the gap—the sides of his head were covered with old scars of the wounds which were all he had gained from those efforts, and both his ears were permanently thickened. But he had never tried to get through since the day when, endeavoring to squirm out tail first, he had practically invited a prowling shark outside to help himself, which that intelligent brute had promptly proceeded to do. It had treated several feet of the sea-serpent's tail precisely as most humans treat a stick of celery—and it had not gone empty away. Indeed, it had abbreviated Spot by at least four feet, and was hanging about just outside the gap on the following day hoping for a further selection of the sea-serpent, when it had fallen a prey to the she who happened to arrive off the island that day.

But even in the slackwater of lagoons, not to mention the wildwater of the sea, the law of Nature is as inexorable as it is in cities. Sea-serpents must eat, as must humans from millionaires down to actors or artists—or even, incredible though it may seem, short-story writers.

And presently Spot abandoned for a space his vigil and instead opened his cavernous mouth across the gap. For an hour fish, under the mistaken impression that they were swimming into the lagoon, swam steadily into the sea-serpent's mouth.

IT was during this hour that a ship appeared on the horizon

and driving steadily before the trade-wind, presently cast anchor

off the island.

Observing from the well-nigh maniacal gyrations and signalings of Mr. Clarke that the island was not wholly deserted, those on board put out a boat.

Driven across the water by its crew of muscular Kanakas the boat presently touched the reef, and its passenger, warned by Mr. Clarke that there was practically no passage through to the lagoon, stepped out on the reef.

He was a tall European, very thin and wiry, with a red mustache and a scarlet nose. Otherwise he was colorless. He seemed very shaky.

"How do?" he said, and explained his shakiness and the bottle of gin in his hand by the brief remark: "Fever, what?"

"Same here," said Mr. Clarke enthusiastically—and they took one each for the fever. Mr. Clarke briefly explained his position and the newcomer readily agreed to take him off the island and deliver him safely at Honolulu.

They took one each to seal the bargain.

"I've been ten years on this lump of coral and I'll be glad to leave it!"

"Sure," said the newcomer, who said his name was Reed and his business that of a collector for the world-famous firm of naturalists, Messrs. Horne, Hyde & Head, Ltd., of London.

"I'd like to drink to their health," said the happy Mr. Clarke.

"Would you? So would I!"

They had one each to Horne, Hyde & Head, Ltd.

Then they had one to Mr. Clarke, followed by one to Mr. Reed.

And then, just as Mr. Reed threw the empty bottle into the lagoon, Spot emerged foot by foot, fathom by fathom, from the water.

Mr. Reed turned white, and his trembling hand closed upon the arm of Mr. Clarke.

"It serves me right!" he groaned. "I knew how it would be with this gin. I ought to have stuck to good honest whisky!"

But the sailor reassured him. It was no dream-serpent that the collector was gazing upon, said Mr. Clarke, but a genuine, thin-skinned, spotted sea-serpent—and to prove it, he called Spot to him.

Obediently the great creature paddled across, to be fondled by his master. For a moment the collector was speechless; then he pulled himself together.

"Is—is he yours?"

Mr. Clarke nodded.

"Is he for sale?" inquired Mr. Reed excitedly.

Mr. Clarke pondered. He did not particularly wish to sell the companion of his solitude, but he reflected that in any case he could not take him away and even if he could have taken him away he could not get him out of the lagoon. He would land in Honolulu penniless, if he refused to sell.

"Well, I dunno—he's a good faithful old sea-serpent. And he's been a good friend to me," he said.

"Will you take five thousand pounds for him as he stands and accept the job of keeper to him at ten pounds a week until he gets used to me?" said Mr. Reed hoarsely, his eyes bulging with excitement.

"Yes," shouted Mr. Clarke in furious haste, "I will!" He had not expected even five thousand pence.

"Shake hands on that!"

Both equally pleased, they shook hands.

"You'll have to enlarge the channel to get him out," said Mr. Clarke.

"Bah! A stick of dynamite will do that. Man, I'd enlarge Hades to get him out!" cried Reed, stroking the huge spotted head.

"But can you get him home?"

"I've got a tank on board with twenty thousand pounds worth of specimens in it. It's big enough to hold him, too! And d'ye know what I'm going to do? I'm going to chuck that twenty-thousand-pounds'-worth of specimens overboard to make room for this chap, Clarke. For he's priceless. He's settled you for life already, and if he don't settle me—and a few others—for life too, you can call me Temperance Joe! Where is this channel—let's have a look at it!"

And they lapsed into technicalities relating to tides and explosives and so forth.

FOUR days later there was observable an unusual stir at the

mouth of the gap.

Mr. Reed was there in a small boat, together with Mr. Clarke, keeping close to the channel, on the seaward side. Spot was there, but he, of course, was in the lagoon. A thick length of whale-line was fastened round his neck and passed to Mr. Clarke, who held the rope. Farther out to sea was the big whaleboat, manned with a heavy crew of Kanakas, and it was to this boat that the end of the whale-line, passing through Mr. Clarke's hand, led. In a tub in the bow of the whaleboat were many fathoms of brand new line. Mr. Reed's idea was to use kindness, if possible, to lure Spot to the tank floating by the ship in readiness for him, and it was Mr. Clarke who, by gentle persuasion on the line, was to do the luring.

But if Mr. Clarke failed, the line was to be flung clear of the small boat and the big whaleboat's crew was to come into action, treating Spot precisely as a whale—until he was tired out and half-choked and ready, even anxious, to give in.

A naked Kanaka was waiting at the narrowest part of the channel ready to dive and place the explosive in the gap upon receiving the word of command.

And though there was no sign of the she sea-serpent, Mr. Reed had not overlooked her. He had little hope of capturing her alive, but he was prepared to accept her dead, if necessary. A second fully equipped whaleboat was hovering close in, with the harpooner waiting in the bows, ready to harpoon her the instant she appeared.

All was in readiness.

Mr. Reed glanced round at his preparations and nodded. He took a little stimulant, passed the bottle to Mr. Clarke, and shouted to the Kanaka at the end of the channel to "carry on."

Nothing loath, the lad grinned, and dived.

Spot was watching the operations with an interest so intent that one might almost have believed that the intelligent reptile knew the object of the work. The rope round his neck seemed to fret him a little, but not more than was to be expected in so soft-skinned a creature.

The head of the Kanaka bobbed to the surface and leaving the water, the sagacious native rapidly caused fifty yards to intervene between himself and the gap.

Almost immediately there was a muffled roar at the gap, a sudden spurting geyser, and a number of big lumps of coral were flung up with the spout of water.

"Look out, now!" shouted Mr. Reed.

The water subsided, and Mr. Clarke pulled gently on the line attached to the neck of the sea-serpent. Recovering from the momentary shock of the explosion, Spot obediently yielded to the slight strain and swam gingerly through the widened channel.

"Here he comes—great work!" said Mr. Reed enthusiastically and seized a long pole with a large bale of fresh sea-weed tied to the end. This ingenious device he pushed out over the stern of the boat, waggling it to attract the attention of the sea-serpent.

"Here he comes—row, you black divils!" said Mr. Reed to the two men resting on their oars. The boat began to edge quietly toward the ship and the fateful tank, attended at a cautious distance by the big whaleboat.

Mr. Clarke, to make assurance doubly sure, set up a croon, intended to soothe and fascinate the big sea-serpent.

"Come along then, Spot! Come along! Come along! Poor old feller, then! Good old Spot!"

Blindly trusting to the good faith of the man for whom he had caught so many fish and who had been his fellow-prisoner so long, and utterly unsuspicious of any contemplated treachery, the great sea-serpent innocently followed the boat, his huge soup-plate-size eyes fixed on the bale of seaweed.

And then, just at the moment when the success of the enterprise seemed to be assured, when another two minutes would have seen the deluded Spot safely immured in the semi-submerged tank, with a big grating clamped down above him, the she sea-serpent appeared.

Her gigantic head shot up through a boiling circle of water and towered, streaming, twenty clear feet above the boat.

With a bellow of delight she hurled herself at the excited Spot, and the two huge heads rubbed together.

"Look out, Clarke! The rope!" yelled Reed, for it was evident that the seaweed had gone completely out of what may somewhat flatteringly be described as Spot's mind.

But, realizing this, Mr. Clarke had already released his grip of the rope, leaving it to the crew of the first whaleboat, and was leaning over, vainly endeavoring to coax the sea-serpent into ignoring the new arrival.

By this time the second whaleboat had rowed up. The harpooner, interested only in the she sea-serpent, cast his weapon.

It passed through her ear—and with a grunt of pain and rage, she shot her head down and seized Mr. Clarke, whom she had never liked and to whose agency she had always appeared to attribute the captivity of Spot.

The last manifestation of life shown by Mr. Clarke in this world was in the form of a large bulge sliding down the throat of the she sea-serpent. With a savage swirl of her tail she upset the whaleboat to splinters, very completely putting the harpooner and his sable colleagues out of action.

Evidently inspired by her example, and intensely excited by his unaccustomed freedom, Spot himself suddenly lost the veneer of tameness which hitherto had always characterized him, and reverted to the wild—to the wildwater.

With a blood-curdling bellow he reached for Mr. Reed and hastily bolted him. Then the great beasts gazed for a brief moment into each other's eyes, exulting in the prospect of freedom which now lay before them.

For a moment they remained so. Then, with a final bellow, they dived together en route for the very floors of the sea and the attractions of the wildwater which, with no more serious mishap than a slight indigestion attributable to Messrs. Reed and Clarke, they were destined to enjoy for many a long year.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.