RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

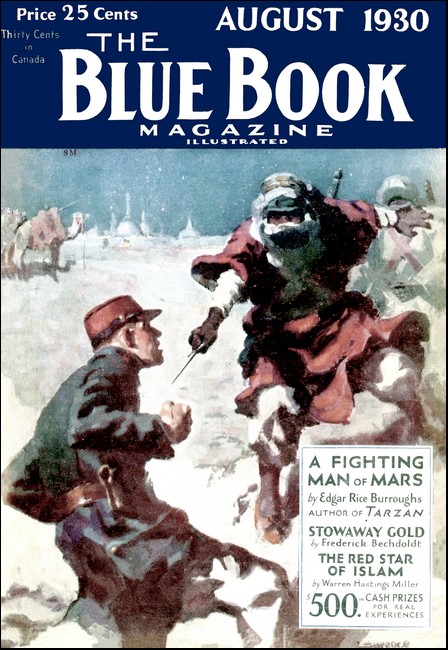

The Blue Book Magazine, August 1930,

with "Wild Work with William the Conqueror"

"'Twas the click of a spear-shaft upon this!" snarled Unna,

guiding her hand to a lump on the side of his head.

An amazing chain of circumstances gave Mr. Honey the ability to leap back across the centuries to a former incarnation. But it was a great gamble—he never could tell whether he'd become (for a time) a king or a slave—or a fly in a spider's web. On this occasion he deals with a great king.

WHILE traveling in India Mr. Hobart Honey of London happened to be walking behind a most reverend Tibetan lama along a Benares street when a vicious dog rushed at the lama. Mr. Honey promptly flung his camera at the dog. Immensely to the surprise of both Mr. Honey and the target, the camera landed fairly upon the dog's skull, flooring it abruptly, and so completely and instantaneously dissolving its ferocity that within a second and a half it had vanished round a corner, complaining bitterly of the English.

The old gentleman in front—who proved to be one of the most distinguished and competent lamas ever exported from Tibet—was almost embarrassingly grateful to Mr. Honey, and bestowed upon him a remarkable gift—namely, a bottle, itself a rare and most valuable example of Chinese glassware, containing certain pellets possessing the singular power of temporarily reinstating the swallower of any one of them in one of his previous existences.

Mr. Honey—unmarried, middle-aged—had taken some months to screw himself up to the point of an experiment. Nothing but an insatiable curiosity and a very good opinion of himself would have driven him to it. If he could swallow a pill and be certain of finding himself back in the days when he was, possibly, King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the First, or some such notable man, that would be quite satisfactory. But there seemed to be a certain risk that he might select a pill which would land him back on some prehistoric prairie in the form of a two-toed jackass, or on the keel of an ancient galley in the form of a barnacle, or something wet and uncomfortable of that kind.

It was undoubtedly a risk. He wished the lama had been a little less sketchy and haphazard about things; at least, he might have dated and labeled the pills. It would have been quite simple—"King; B.C. 992," for instance; or "Centurion; Early Roman." Or, if clammy incarnations had to be introduced: "Eel; 1181 A.D." or "Squid; Stone Age." Then he would know which pills to take himself, and which to set aside for editors and publishers.

At length Mr. Honey made the experiment—and found himself the court chiropodist to Queen Semiramis! He had a hard time in Babylon, and rejoiced when it was over; but curiosity drove him to further ventures—in which he found himself, successively, a singularly miserable cave-man, an unsuccessful and sorely bedeviled pirate, and an anthropoid ape condemned to fight a lion in a Roman amphitheater.

ON the evening which he had set aside for the swallowing of

the fifth of his pills, it is worthy of note that Mr. Hobart

Honey, for a considerable time before proceeding with the

matter, sat in profound and somewhat melancholy reflection.

To deny that he was bitterly disappointed with the results produced by the first four pills would be to deny the truth. He had that day vaguely discussed the question of reincarnation with a Fleet Street friend, who had cheerfully presented Mr. Honey with his somewhat flippant views upon the subject.

"If there is anything in this reincarnation business at all, Honey, old man," that individual had said, "and mind you, it is a pretty useful notion,—cheery idea,—my view is that it is like going up a ladder or a staircase. Every succeeding incarnation is a bit of a lift—promotion, you may say. Take me, for instance. Millions of years ago, say, I started life as a bingosaurus, or whatever they were called.[*] I was on the bottom rung of the ladder of life. After a bit, I got killed and eaten by a dandaloorus, or something of that kind. Right. I am not done for. A bingosaurus is done for, true; but I—me—have passed out into another incarnation—say, for the sake of argument, a woolly rhinoceros, which is a much brainier and better-class animal than any bingosaurus—which was only a reptile, anyway—ever knew how to be. Second rung, see? Promotion! One up on the bingo, so to speak.

"Presently the woolly rhinoceros has a mammoth fall on him and render him extinct. Very well—don't matter to me! Rotten for the rhino, of course—but as for me, why, I'm going as strong as mustard. I'm reborn as a large ape. See, Honey? Getting brainier—on third rung. Getting on in the world—see what I mean? Great idea, reincarnation! And so on—up and up and up—until finally, after millions of years, I become—well, what I am. A Fleet Street reporter—top of the ladder, practically speaking. Surprise the bingosaurus a bit if he only knew how he'd got on in the world, eh? Well, that's my idea of this reincarnation business, see? Moving up."

[* The Fleet Street man clearly meant "dinosaurus." There was never a bingosaurus. —Author.

It was upon the words of this inspired young gentleman that Mr. Honey meditated before consuming Pill Five, and considering that all his pills were designed to take him down the ladder,—back towards the bingosaurus era,—it is not difficult to understand that the author was not in an altogether outrageous hurry to swallow the pass that would send him sliding back to those doubtful ages of which he bad already had such jarring experiences. But as usual his curiosity presently overcame his disinclination to risk the discomforts of possibly yet another violent death; and so, abandoning unprofitable speculations, he darkened the room slightly, abruptly swallowed the pill and—left it to Luck.

AS usual his luck, good or bad, was not long in arriving. Almost before he had settled comfortably back in his chair, Mr. Honey perceived that there seemed to be something wrong with his left hand, which was resting upon the arm of the chair. Mr. Honey had very good hands—white, well-shaped and well-kept. But the hand he was now gazing at was neither white nor well-shaped nor well-kept. It was, indeed, a desperately dirty, grievously gnarled and calloused, very big and shockingly badly kept hand—the sort of hand, indeed, that might belong to a charcoal-burner in the days of the Norman Conquest.

But Mr. Honey was not surprised at the appearance of his hand, for if that had changed, so too had the author's entire physical make-up, his environment, and a good deal of his psychological equipment.

He was, in short, precisely what the look of his hand suggested—a charcoal-burner in the days of William the Conqueror. The transformation from a Twentieth Century author had been so smooth and swift that Mr. Honey had not even noticed the "clock" of whatever invisible mechanism—if any—the pill had set in motion.

With a somewhat melancholy attempt at self-congratulation upon the fact that at any rate he had not become anything more unpleasant—-for instance, a badger fuming silently in his burrow, or a lugworm upon a prehistoric fisherman's flint hook, or a medieval gudgeon dodging a medieval pike—Mr. Honey began to take stock of his present situation.

It was, he speedily decided, not too enviable. Although his prospects were tolerably good, food was extremely scarce; clothes, save the ragged leatherish raiment he wore, were non-existent; and the rain came through the roof of his hut.

He brushed the matted hair from his forehead, and pulled rather aimlessly at his well-smoked whiskers as he glared dully up at the hole in the thatch.

"It lets the smoke out," he muttered in the uncouth Saxon that was fashionable among the New Forest charcoal-burners at that period. "But it lets the rain in."

HAVING thus set the credit of the hole against the

debit, he sat worrying out, in a thick-headed, wooden-witted

way, whether there was a balance on either side, and if so,

which.

He decided that, although personally he preferred to be smoked rather than soaked, he would leave the hole, as probably his wife—and his wedding was to take place on the following day—would prefer the extra ventilation. Being a field-hand upon the land of the local abbot,[*] she was less accustomed to smoke and more used to the open air than he—Unna, the charcoal-burner.

[* In those days abbots were as plentiful as rabbits nowadays. —Author.<]/p>

This settled, he began to brighten up a little. After all, he was one of the lucky ones. The abbot was favorable to him, or if not favorable, at any rate the abbot knew of his existence. He began to eat a queer-looking lump of breadlike stuff and an onion, and to turn over in his mind his prospects. For although at the moment things were not very flourishing with him, his prospects were good. He had recently enjoyed a great stroke of luck.

Passing through the wood by a deep, high-banked brook, he had seen an ass fall into the water—owing to the collapse of that part of the bank upon which the ass—like an ass—was standing. Recognizing the donkey as the property of the abbot, Unna had promptly jumped in and rescued the animal. He had pushed the creature up the slippery bank, and as luck would have it, the couple gained the firm soil again just as the abbot, and a dozen attendants, had passed that way. The abbot had been pleased. He proved it by ordering that the groom in charge of the ass department of the abbey should be whipped daily for a few weeks—until, in fact he learned to be careful.

As regards Unna, the abbot, being in a good temper, asked him to name the reward he wished.

Unna had humbly begged permission to marry Hild the haymaker. The abbot put a few inquiries to the steward, bailiff and other agricultural hirelings accompanying him, discovered who Hild was, and graciously agreed.

"So thou shall, charcoal-burner, so thou shalt. I look favorably upon thee, my son. Marry the wench, by all means!" He turned to the steward. "Let the good charcoal-burner be given a couple of pounds of bacon for his wedding feast, and an iron halfpenny wherewith to buy him ale," he added generously, threw in a blessing gratis, and expressed a hope that Unna's married life would be happy and—the abbey lands being short of hands—crowned by the inestimable boon of a great family of sons.

No wonder Unna, eating his supper in his hut in the year 1070, reflected that, on the whole, things were going well with him. The all-powerful abbot not only knew of his existence—a rare stroke of luck in those days—but had given him a ha'penny! True, he had not got it yet; but if the steward did not forget it, that would be all right. If he went on like this, he would die worth a shilling, at least; and who knew but what, with luck, he might even rise in the world to be a horse-cleaner in the abbot's stablest It was a tall order, true; but Unna was an ambitious man.

As he sat thinking, some one entered the hut. He turned on. his stool, and beheld Hild the haymaker.

In the year 1070 they had ideas about beauty which varied considerably from those which were in vogue during the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. Hild, therefore, did not resemble to any extent the oftentimes charming young ladies who may occasionally be observed nowadays haymaking in the meadows. She wore her hair differently, for instance. It hung upon her head like ivy upon a wall. She was a large girl, with bare feet and arms. She had muscles like a strong man. The chiseling of her heavy features was crude. Her clothes were about eight hundred and forty-six years behind the fashion. But she had a good heart, and adored Unna with an adoration which he returned.

Unna put down his bread and half-finished onion, and rising, kissed her long and warmly.

"Hild, thou art pale and overcome!" he said presently, releasing her.

She leaned against the wall, panting, gasping for breath.

"I have run all the way from the huts of the field-workers, Unna," she said.

"Sit down and rest," replied Unna. "Have some bread and onion."

"Nay, there is no time for pleasure," said the girl. She came close, whispering: "Unna, there is foul work afoot."

"Where?" asked Unna, naturally enough.

"Here—in the forest!"

"Hah!" said Unna. "Go on, Hild."

"There is a plot to take the life of the King!"

Mr. Honey—Unna, that is—guffawed.

He had not brains enough to accommodate an idea of that size. As well tell him that some one was proposing to switch off the light of the sun, or to renew the silver plating of the moon. He was a plain man—a singularly plain man, indeed; and there were four things which he always took for granted—the sun, the moon, the weather and the King. Anyone who talked of killing the King was, in Unna's opinion, simply talking through the base of his or her skull. The idea, in short, was too big for Unna—it was a balloon-sized idea, and he only wore a bean-sized head. So he laughed.

"When thou laughest like that, Unna, thou art like unto a human goat," said Hild sharply. "Listen to what I say."

Not wishing to offend her, Mr. Honey listened. And what she told him nearly rendered him deaf with shock.

IT appeared that on the previous evening she had been

working in a newly broken field some distance from the abbey,

and was returning home through the twilight, taking a shortcut

through the woods, when she saw two strangers riding slowly

toward her. Concealing herself in a hollow tree, for fear that

they were robbers or outlaws, she waited for them to pass.

They did not pass, however; but oddly enough, came to a halt

at the very tree which sheltered her, and there proceeded, in

low voices, to discuss certain plans to kill the King. The

proposed mode of procedure was simple. The Conqueror was to

hunt the stag in the woods close by, on the following day; and

the conspirators, if an opportunity occurred, were to aim an

arrow ostensibly at a stag, but in reality at the Norman King.[*] Hild had not learned the names of the knights, but on peering through a knothole, she had gleaned a very fair idea of their appearance. She would know them again.

[* Some years later the same infamous plan was carried out against the successor of the great Norman, with what result is known. —Author.]

Her idea was that Unna should go to the abbot and inform him of the plot. He would thus gain even greater favor and, it might easily be, promotion.

Unna thought it over. It seemed to be an excellent idea. The abbot could warn the King, who doubtless would reward him immensely, and subsequently the abbot would reward Unna and his wife. Undoubtedly it looked good—very good.

Mr. Honey said so, and rose.

"Come, Hild, let us go to the abbot," he said. "It may be that he will give us a little farm."

Hild was more than ready to accompany him, and they hastened toward the abbey.

HALFWAY thither a gleam of caution penetrated through the

matted hair of the charcoal-burner.

"Thou art sure of the words overheard, Hild?" he asked.

Hild was, and said so emphatically. Satisfied, Mr. Honey—we mean Unna—pushed on until the great building of the abbey loomed before them. They worked their way round to the gate, which in those strenuous and still unsettled days was guarded by a covey of men-at-arms.

Unna approached them deferentially. One of them demanded his business—briefly and somewhat profanely.

"What dost thou need, sooty pole-cat?" he inquired, with verbiage.

"Word with His Grace the Lord Abbot," said Unna ambitiously. "I have news for his ear alone."

The guard simply clouted him across the ear with the butt of his spear.

"Ass!" he replied. "Dost think His Grace the Lord Abbot hath nought better to do than converse with the likes of thee? Get thee gone to thy sty, pig, and swiftly, lest I take my battle-ax unto thee!"

The guard clouted him across the ear. "Get thee gone to

thy sty, pig," he replied, "lest I take my battle-ax to thee!"

Mr. Honey perceived that as far as the guard was concerned, he was "declined without thanks." He gulped, and slunk back into the darkness, where Hild, too well aware of the character of the men-at-arms to venture near them, was waiting.

"Unna," she said in surprise, "I heard a clash as of wood upon wood, and I thought it was the closing of the postern gate as they conducted thee to His Grace."

"Nay," snarled Unna. "Twas the click of a spear-shaft upon this."

And he guided her hand to a lump upon the side of his head that was already the size of a medium tomato, and still growing.

Hild comforted him, and thought hard for some minutes.

"It is clear that thou wilt never gain the ear of His Lordship save by stealth," she said at last, thoughtfully gazing at the lighted windows of the great dining-hall of the abbey. Then her face lighted up, and she swiftly whispered a plan. It was desperately bold—being, indeed, none other than a suggestion that the wooden-witted charcoal-burner should climb up to the window nearest the end of the table at which the abbot sat, smash it with a stone, thrust his head in, and shout his startling news to the reverend gentleman before the servants or guards had time to perforate the messenger with arrows.

At first Unna abruptly refused, but the girl drew such a tempting—though sketchy—picture of the imaginary farm which would probably result, that she speedily convinced the charcoal-burning clown of the wisdom of the plan.

"But they will be certain to kill me, Hild?" he demurred feebly.

"Not they, Unna. Hast thou in all thy life ever heard of a charcoal-burner being killed at the window of an abbey?"

Unna was forced to confess he had not.

"Very well, then. What is there to fear?" said Hild.

Vaguely conscious that there seemed to be something decidedly rocky about Hild's logic, but being quite unable to discover what it was, Unna moved forward, grumbling a little, but fortified by the vision of that farm.

He found a pole, placed it against the wall, and after some desperate work, managed to scramble up to the base of the window. Once there, he discovered that, very intelligently, he had omitted to supply himself with a stone, an omission which he laboriously clambered down to rectify. Presently, provided with an enormous flint, he struggled again to his perilous perch.

He rested a little, regaining his breath; then, taking a firm grip on the shank of the stone, he announced his presence to the abbot and his associates by the simple process of totally and noisily destroying the window.

The glass fell in showers, and Unna thrust his liberally besooted face through, calling humbly upon the abbot.

To describe the crowd of monks assembled in the refectory as being "confused" would be to commit the fault of inadequacy. They were completely and utterly be-buffaloed en masse. The sooty face, the white-rimmed eyes, the black matted hair, the gleaming teeth, the scrambled whiskers of Unna, as he glared in upon them with a curious expression of anxiety and fear upon his very "early English" face, froze their blood.

The abbot dropped his glass with a yell, and one of the more pessimistic of the monks announced in a howl that the end of the world had arrived, and that they were being fetched—presumably by the only being who, at the end of the world, could possibly have any animus against men of their profession—Satan, to wit.

Then the window gave way and, accompanied by a shower of glass, Unna fell among them.

Then the window gave way and Unna fell among them.

The abbot was bawling to the servants and guards in a thin, frightened voice, and Unna hastened to reassure him.

"It is only Unna the charcoal-burner, Holy Father," he said anxiously over and over again, grinning doubtfully as he spoke. "I bring grave tidings—of a plot against the life of our lord the King. They would not admit me at the main gate—"

WITH an effort the abbot recovered himself.

"Silence, rash prater!" he growled, and took a little stimulant. "Thou hast utterly spoiled my evening meal!"

"The tidings I bring are grave," mumbled Unna. "A plot against our lord the King."

The abbot looked uneasy. "A what?"

"A plot, my lord!"

"Describe it!"

Unna did his best to describe it, but he became grievously entangled. The only part of the mumbled and confused story which seemed clear was the fact that King William was to hunt in the neighborhood on the following day, and the abbot knew that already.

Acutely conscious of the meal which was still awaiting his attention, and easily dismissing the remainder of the unfortunate Unna's story as an absurd invention, quite possibly due to the fact that the charcoal-burner was weak in the head, the abbot dismissed the matter abruptly.

"Take him away, and let him be generously flogged by the men-at-arms.. Also let the bounty which was to be bestowed upon him for the rescue of the ass be forfeited! Clear him away," said the abbot curtly, and turned to his goblet and platter.

Stunned by the loss, not only of the visionary farm but of the bacon for his wedding feast and the iron halfpenny, the wretched Unna was on the point of being led away and turned over to the men-at-arms when a sudden clamor rose just outside the entrance to the refectory. Before the abbot and his monks quite realized what was happening, a black-haired man of enormous build, of extraordinarily commanding presence, with a hard, righting face, shrewd eyes and an arrogant manner, strode into the hall.

"Per la resplendar Dé!" he said loudly, indicating the well-spread table to a press of knights crowding behind him. "But we have arrived at an auspicious hour. How sayest thou, good abbot?"

It was none other than William the Conqueror. The house at which he purposed spending the night had taken fire late in the afternoon, and he had ridden on to the abbey.

His keen gaze took in the broken window, and settled on Unna.

"What is this?" he said dourly.

"Only a poor charcoal-burner, my lord King," muttered Unna.

"Ha! What dost thou here,-charcoal-burner?" barked the Conqueror.

The abbot, very deferentially, ventured to say that the man was not right in his head, and had entered—by the window—with a rigmarole which no one could understand. He had already ordered the creature to be well flogged—presumably to sharpen up his wits.

But the King was a shrewder man than the abbot. He had need to be.

"Rigmarole, sayest thou, Abbot? Let us hear it. Nay, not thou, but the charcoal-burner. Speak, man, lest I have thine hand lopped, pardieu!"

Unna spoke.

IT seemed as though the frightful danger in which he stood

had stropped his wits. And without daring to look at the

terrible presence towering before him, he most marvelously

managed to blurt out quite a creditable account of Hild's

story.

The Conqueror listened to the end in absolute silence. Only his hard, shrewd face changed. His lips set in a thin, bitter line; his black brows bunched together in a gnarled frown; and his eyes gleamed like pike-points.

He ground out a few of his favorite Norman oaths as Unna finished, and whirled on the abbot.

"Callest thou that a rigmarole, Belly?" he snarled. "I will learn thee somewhat soon, Fat-wit! Thinkest thou I bestowed this good abbey upon thee for naught? I looked to thee to keep thine eyes and ears open, so that thou shouldst be aware of the plotting of those in the neighborhood who are evilly disposed toward us. But thou hast no eyes save for thy dish, and no ears save for the gurgle of wine. Thou art an oaf and an ass, and but for this good charcoal-burner I should doubtless have come by a perforated mazzard ere the setting of tomorrow's sun."

The furious monarch turned to Unna.

"Knowest thou the knights who conspired against our well-being, charcoal-burner?"

"Knowest thou the knights who conspired

against our well-being, charcoal-burner?"

Unna scratched his head so diligently that he might have been trying to excavate a recollection of Hild's description of the men—as indeed he was. And he succeeded.

"I know not their names, my lord King, but the hair of one of them was of a glowing and fiery red, and his face was bespotted of moles."

"Hah! That is Sir Uther Jogon Bavenpile!" exclaimed a young monk with crafty eyes. "As disloyal a hound as went unhanged!"

William nodded approval, and ticked off three of his knights—grim-looking sportsmen in armor.

"String me Sir Uther up to the stoutest tree in the merry greenwood," said he.

"The other, my lord King, stammered in his speech a little, and upon his upper lip was a large wart," said Unna.

The King looked inquiringly toward the crafty-eyed monk.

"Sir Uther's uncle," said that one.

"That is worth a bishopric to thee, monk," said William, and ticked off three more knights.

"Cure us the stammer of Sir Uther's uncle—with rope—upon the same tree," he ordered.

The knights rode forth, and the Conqueror turned again to Unna, whom he commanded to strip.

Greatly wondering, Unna did so.

Then addressing the abbot, William said:

"Thou wert abbot, and thou sawest nothing nor didst thou hear anything. Thou art therefore a species of abbot which is valueless to me." He turned to Unna.

"Thou wert an humble charcoal-burner, but natheless, thou and thy wench wert keen to scent danger to thy king, and swift to incur grave risk to warn those who could save us, but yet were too slothful to bestir themselves. Thou art an altogether superior charcoal-burner. And if at any time hereafter there shall arise any man in all this fair land to question my judgment in this matter,"—the Conqueror glared round at the shrinking crowd,—"then, per la resplendar Dé, I will so deal with him that ever thereafter he shall fail to distinguish the front of his face from the back of his head! Now, dress—and quickly; for thou, Abbot, art somewhat sooty and in sore need of ablution—while thy gross habit is offensive to mine eyes, charcoal-burner."

And so saying, the Conqueror swaggered to the head of the table. The ex-abbot slunk out—presumably to occupy Unna's hut; and Unna, feeling dazed, donned the monkish costume awaiting him.

"Sit thou here at our right, good Abbot," said William graciously.

MR. HONEY, so dazzled with his good fortune that he saw

things but dimly, moved forward, and suddenly was aware of a

stream of perfectly frantic language issuing from under his

feet.

He started and looked down, to discover that he seemed to be treading upon the tail of Peter, his white-eared black cat. He moved his foot and glared round, sick with disappointment. He was back in his London fiat again. The power of the pill had waned once more, but this time at a highly inconvenient moment.

It is regrettable to have to record here that for a second or so the language of Mr. Honey rivaled that which the disgusted Peter, who had retired under the settee, had used.

"Just as I was beginning to mix in decent society," he snarled. "To be switched off like this! Too bad—it's too dashed bad!"

And so, reluctantly resigning himself to the situation, he settled down to sulk for the remainder of the evening.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.