RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, September 1930,

with "The Private Assassin"

Wherein a modern Londoner finds himself ap-

pointed personal bravo to an Egyptian queen.

"I like thy looks, murderer," said Antony.

Take this as a symbol of my approval.

WHILE traveling in India it so happened that Mr. Hobart Honey saved the life of an important Tibetan lama; and in return the lama presented Mr. Honey with a bottle of marvelous pills, any one of which possessed the singular power of temporarily reinstating the swallower of any one of them in one of his previous existences.

Mr, Honey—unmarried, middle-aged—had taken some months to screw himself up to the point of an experiment. Nothing but an insatiable curiosity and a very good opinion of himself would have driven him to it. If he could swallow a pill and be certain of finding himself back in the days when he was, possibly, King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the First, or some such notable man, that would be quite satisfactory. But there seemed to be a certain risk that he might select a pill which would land him back on some prehistoric prairie in the form of a two-toed jackass, or on the keel of an ancient galley in the form of a barnacle, or something wet and uncomfortable of that kind.

It was undoubtedly a risk. He might find himself the Great Mogul or T'Chaka, Jonah, Shakespeare, Jack Sheppard, Adam, Oliver Cromwell, a dromedary, a polecat, a starving wolf, a skunk, or merely a house-fly in a spider's web.

And a risk it proved; for his first venture took him back to that difficult time when he was court chiropodist to Queen Semiramis. Mr. Honey didn't enjoy being court chiropodist; nor did he, indeed, especially enjoy his experiences—as a cave-man, as a pirate, as a gladiator in the Roman arena, and as a charcoal-burner who had strange dealings with William the Conqueror—which, in due succession, followed.

YET it is not to be denied that Mr. Honey's adventure

with and sudden rise in the favor of William the Conqueror

considerably stimulated the somewhat flagging enthusiasm

of the author. He said so—to Peter, the white-eared

black cat who, since the author had not a wife, was Mr.

Honey's favorite confidante.

"It was a great rise in the world, Peter," he said, finishing an after-dinner cigarette in his study on the evening he purposed taking the sixth pill; "yes, a great rise in the world, and it will always be a matter of regret to me that I had not more opportunity of cultivating the acquaintance of William. He was a fine-looking man, and also he was very highly intelligent. A little abrupt in his manner, perhaps, but we must remember, Peter, that those were abrupt times. I was a charcoal-burner when I met the abbot, and I venture to assume, Peter, that I made a very excellent abbot indeed. It was a pity that the power of the pill waned so soon—a great pity. But let us try again.'He threw his cigarette-end into an ashtray, reached for Hie bottle of pills, and trickled out a large one.

"Let us see where this one leads us, Peter," he said as he swallowed it, aiding it on its journey with the customary glass of sherry.

THIS time it led him straight to Egypt in the days of

Queen Cleopatra, as he speedily discovered when he woke, or

rather recovered consciousness, in the existence back to

which the power of the pill had impelled him.

The position in which he discovered himself perplexed him considerably for the first few confused seconds after his arrival at his destination. He found himself on all fours, kneeling on the marble floor in the corner of a huge apartment, gazing attentively at a small crevice between a floor block and the first block of the wall.

Then abruptly the Twentieth Century and all appertaining thereto receded from his mind until it was no more substantial than the airy fabric of a dimly remembered—though by no means completely forgotten—dream, and he realized whom and what he was—namely, Assistant Royal Rat-catcher to the Queen, busily engaged upon his duties. For a fleeting moment he brooded sullenly, still staring at the hole, but he was given little time for brooding. A three-thonged whip curled shrewdly about his extremely lightly clad form, and a sharp voice harshly bade him get on with his work. It was the voice—and the whip— of the Rat-catcher-in-Chief.

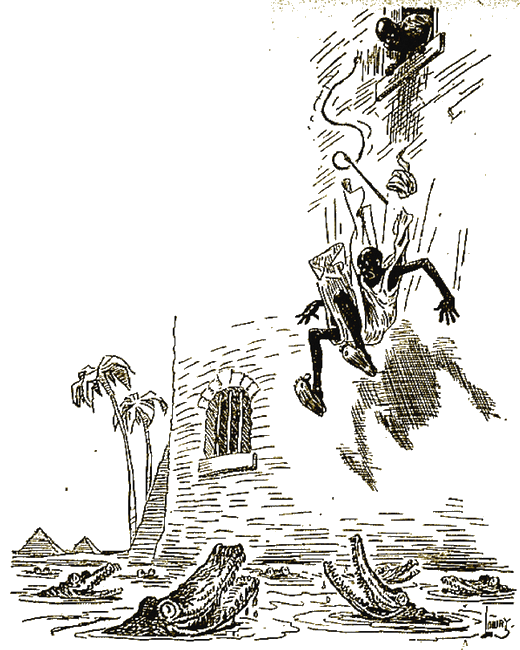

Mr. Honey, acutely conscious of many wrongs and innumerable lashings received from this gentleman—a long lean lanky person with sly eyes and a rather ratty face —suddenly lost his temper. He sprang to his feet with a bound, a queer thrill of savagery vibrating all through him—and boiling with anger, he seized the Chief Rat-catcher by one leg and the back of his neck, and, plunging toward the side of the room which opened out upon a lake, promptly pitched him into the water. A number of things resembling logs, which were floating upon the surface, suddenly became remarkably active. They were crocodiles.

The Chief Rat-catcher did not reappear.

Boiling with anger, Mr. Honey seized the Chief Rat-catcher

and pitched him into the water. He did not reappear.

"It may be that that will teach thee to tyrannize over me!" said Mr. Honey satirically, glancing round to see whether he had been observed.

Apparently no one had witnessed the passing of the Chief Rat-catcher and Mr. Honey, smiling contentedly, and seeming quite undisturbed at the deed, quietly resumed his work. Life, in those days, and in that place, was held very cheaply. In the opinion of anyone who was anyone, it would be merely a rat-catcher that was gone; not a human being—merely a machine that caught rats. It would only be considered rather a nuisance in the event of the rats increasing. If they did not, nobody in Cleopatra's palace was in the least likely to inquire as to what had become of the Chief Rat-catcher.

Nevertheless, Mr. Honey—or Hu Neh, as he was generally known—was conscious presently of a faint sensation of uneasiness. For the man he had just thrown into the lake had been a notoriously brilliant practitioner—famous, indeed, in rat-catching circles. And Hu Neh felt decidedly uncertain as to whether he personally could keep the rats down sufficiently to satisfy the occupants of the palace, in which case prompt inquiry would be made as to the reason.

Stilling his uneasiness, however, Hu Neh drew a long, thin, greenish snake from a bag[*], inserted it into the rat-hole, and hurried round to what he imagined might be the exit of the doomed rodent inhabiting that particular hole.

[* In those days they used snakes instead of ferrets. They could bend better. —Author.]

This, however, is not a romance of rat-catching, and the reader may be spared the more grisly details of the subsequent swift decease of the rat which Hu Neh was pursuing. He had hardly killed it, indeed, and re-bagged his serpent preparatory to moving along to pastures new, when a gigantic Nubian slave approached, demanding the whereabouts of the Chief Rat-catcher, as his presence was required instantly by no less a personage than Queen Cleopatra herself, whose guest the Lord Antony had been rather sharply bitten in the night by a rat.

The Queen was furious, added the Nubian, and, speaking for himself, he did not particularly envy the royal rat-catching staff, Certainly, he said furtively behind his huge black hand, he felt extremely glad that he did not stand in the Chief Rat-catcher's sandals,

Hu Neh, with great presence of mind, informed the Nubian that he had seen his chief entering a wineshop close to the palace an hour ago.

"And doubt ye not, Nubian," he added, "doubt ye not that there wilt thou still find him; and, unless I am mistaken, he will be well upon the way to seeing more rats than he can catch in all his life."

The Nubian guffawed, and innocently went in search of the Chief Rat-catcher. Hu Neh watched him go, and proceeded with his duties, gradually working his way round to the royal kitchens, which he had craftily discovered was a good locality to be in at meal-times.

IT was perhaps an hour later when Hu Neh, busily engaged

with half a boar's head and a skin of wine skillfully

acquired from a friendly cook, looked up to see once again

the Nubian slave towering over him,

"The Rat-catcher-in-Chief hath vanished —wisely," said the black giant. "Thou thyself art bidden before the Lord Antony. And, Hu Neh, beware, for she is there, and she tappeth her foot upon the floor in that way she hath!"

Hu Neh understood. He knew that when Cleopatra was "tapping her foot on the floor" it was by no means intelligent or witty to keep her waiting.

"I come, Nubian," he said promptly; and followed the slave.

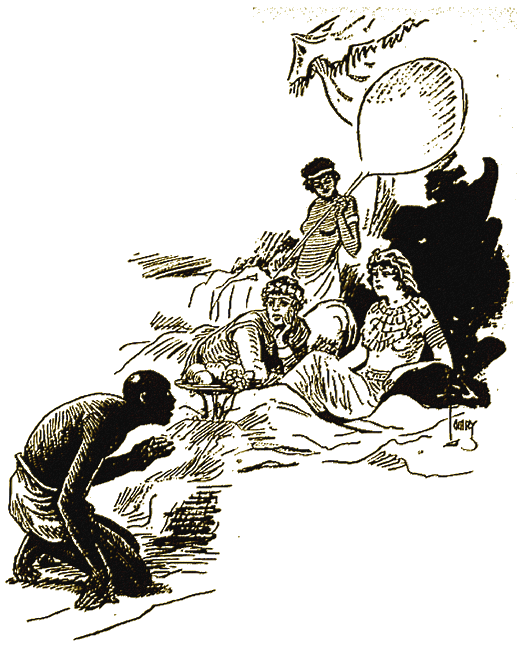

The Queen and Antony evidently had breakfasted together in private. They were in a beautiful little Egyptian-style room opening out onto gardens. Hu Neh entered, bowing so low that, practically speaking, he was crawling. Nevertheless, he was able to note that Antony, despite his bite, looked cheerful enough. He was lolling upon a couch, eating fruit.

Cleopatra, on the other hand, was not looking so cheerful. She was beautiful, but she looked about as safe as cholera. Her brows were black and frowning, and her eyes were not assuring to gaze at.

The Nubian, who had crawlingly preceded Hu Neh, looked at her humbly.

"What is this, black animal?" she inquired, her voice seeming rather more reminiscent of broken glass than of silver.

"The Assistant Rat-catcher, Glory of Egypt," said the Nubian.

"Hah!" said Cleopatra, in a voice that made the men, including Antony, jump slightly. "Why not the Rat-catcher-in-Chief? And where is the executioner? By the beard of Ptolemy, am I to be ignored, disdained, and despised by my own cattle in my own palace? Convey thine unsightly bulk from the range of my vision, slave!"

Gladly the Nubian made his exit. The Queen whirled upon Hu Neh, "Where is thy chief, rat-man?" she demanded.

Hu Neh perceived that desperate measures were necessary; an inspiration came to him, and he looked as truculent as he dared.

"I slew him this morning, Most Illustrious!" he said bluntly. "For many moons past he hath neglected his work, and I could not endure the thought that, unless we became more urgent in our labors, the rats would overrun the palace. So I slew him and cast him to the crocodiles!"

He bowed meekly, and waited.

"Thou daredst murder our Rat-catcher-in-Chief?" ejaculated Cleopatra.

"Even so, Moon of Alexandria!" said Hu Neh.

The deadly Queen seemed puzzled. Either this was insolence too great to be punished by mere death, or it was genius too great to be rewarded by any ordinary reward. Peering up under his brows, Hu Neh saw the beautiful but bad-tempered Moon of Alexandria turn to Antony.

"What sayest thou, guest of my heart? Hath this creature earned life or death— shall he be minced or medaled? By the Pyramid of Cheops, I know not."

The Roman smiled.

"Hostess of my soul," said he, "we of Rome have a saying: 'Waste not a good murderer.'"

Cleopatra nodded. She was always very quick on the uptake.

"True, my lord," she murmured.

Then, frowning thoughtfully, she turned to Hu Neh.

"Thou hast done well. I appoint thee private Assassin-in-Chief. Now, get thee gone to an armorer's and arm thee; to the doctor's and equip thee with poisons. Then report again."

Cleopatra turned to Hu Neh. "I appoint thee private Assassin-in-Chief.

Get thee to the doctor's and equip thee with poisons; then report again."

Dazed a little by his good fortune, though not in the least perturbed by the sanguinary career opened up for him, Hu Neh vanished in search of his "equipment." He lost no time, for he had an idea that it would not be long before Cleopatra would require his services, and he intended to begin well and go on as he began. None knew better than Hu Neh that it was a great rise in the world for him; it was a great honor—and he intended to prove worthy of it.

He was therefore not in the least surprised when a little later he was sent for again by the Queen, who this time received him alone, save for her favorite personal attendant, in a chamber the entrance to which was heavily guarded by armed men.

As the newly appointed Chief Assassin entered, Cleopatra favored him with a glance so searching that for an instant he had a queer sensation of being composed entirely of extremely transparent glass, easily seen through. That this was not entirely the case, however, was proved by the first words of the fatal Queen.

"Thou hast done well, Hu Neh," she observed, her glance playing about his weapons and businesslike attire,

The erstwhile Hu Neh emitted servile sounds.

THERE was a short pause, as the Queen reflected. Then

she said abruptly: "Art thou conversant with current

gossip, murderer? Dost thou keep thyself acquainted

with the lying rumors that daily flutter, like birds of

ill-omen, in and out of this palace and this town? Hast

thou any knowledge of high politics?"

"As much, great Queen, as is good for a man," said Hu Neh cautiously. "But I do not believe it," he added darkly,

"Hah! Thou hast wit that would be wasted in a rat-catcher. Perchance, then, thou art aware that the Lady Octavia, the alleged wife—in Roman law—of the Lord Antony, is at Athens?"

"I have heard rumors thereof, Pearl of Egypt," murmured Hu Neh.

"And, since thou art not completely brainless, thou art aware that the Lord Antony, by Egyptian law, which is altogether superior to that of Rome, is our husband?"

The Assassin-in-Chief bowed to the ground.

"And, further, it may he that rumor hath informed thee that while the lady will remain in Athens until the noble Antony giveth her permission to proceed hither, or which is the more probable, to return to Rome and her brother Caesar, she hath, nevertheless, sent from Athens a company bearing many rare and costly gifts, and great promises from Caesar to the Lord Antony, in the hope that he will return to Rome and his Roman wife?"

"It is even so, Diamond of Africa."

"Then go forth, good murderer, and meet this company. If ye need men, take from among our troops as many as ye shall require. Mingle with the cohort from the Lady Octavia, gain their confidence, discover the whereabouts of the treasures, and then kill them all, and bring the treasure hither unto me. Dost thou understand?"

Hu Neh signified that he did.

"That is good," said the sinister beauty graciously. "Go, then, and be sure that if thou acquittest thyself well in this little matter, I shall have affairs of greater import for thy handling when thou returnest—and great advancement for thee also."

And, so saying, dismissed him.

Hu Neh, his brain whirling at what his moral-less mind conceived to be his great good luck, backed out.

A little way down the corridor he was met by a young soldier, a member of Antony's staff, who, speaking in Egyptian with a strong Roman accent, informed him that the Lord Antony desired his presence and requested him to follow.

Ever ready to oblige, Hu Neh followed, and duly was shown into the presence of Antony,

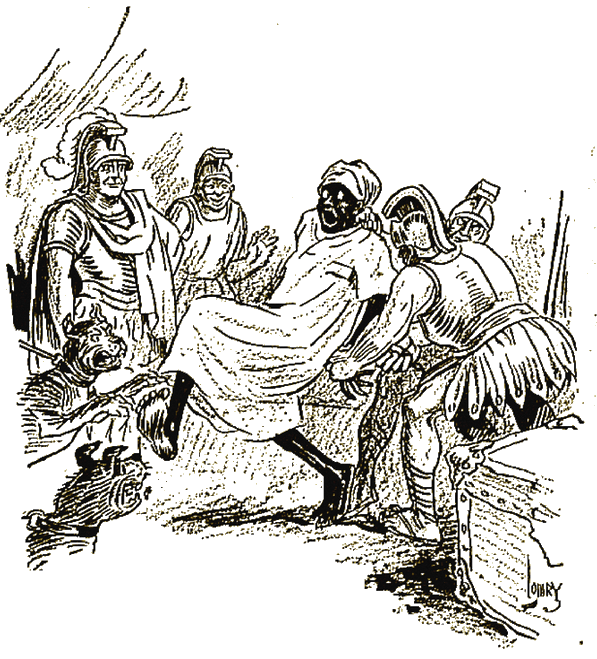

For some moments that intricately wedded nobleman surveyed the chief murderer in silence. Then, having apparently summed him up to his satisfaction, he took a large fistful of gold from a bag close by,

"I like thy looks, murderer," said he. "Take this as a symbol of my approval."

Hu Neh took it, murmuring his thanks.

Then, ordering his attendants to leave the room, Antony desired the Assassin-in-Chief to help himself freely to wine, which Hu Neh did without unnecessary delay.

"Tell me, assassin, whither goest thou?" inquired the nobleman.

Hu Neh perceived that he was being "pumped."

"I know not, Lord," he said.

"Thou art a liar, I see!" observed Antony calmly. "Have a care, Egyptian, lest I express to thy Queen a slight curiosity to see how thou wouldst look if thou wert embalmed."

HU NEH felt a chilly sensation in the region of his

spine. None knew better than he that Antony's every wish

was granted gladly by Cleopatra. He was perfectly well

aware that if Antony chanced to say in the Queen's hearing

that he had an odd fancy to see how Hu Neh would look if he

were embalmed, perhaps five minutes might elapse before the

embalmers were working on him, but not more. Decidedly not

more, and possibly even less.

"Pardon, Lord," he muttered humbly.

"Thou art forgiven," Antony granted. "Whither goest thou, and why?

This time Hu Neh told the truth,

"Hah!" said Antony, and began to stride to and fro. "Indeed! I see!" He strode for some time, thinking deeply. Once he looked at Hu Neh absently.

"Art a married man, murderer?" he said.

"Nay, my lord."

"Wise man," said Antony vaguely, and continued his striding. He was, indeed, in a somewhat tricksome position. He did not wish to offend the Emperor Octavian, and he certainly did not wish to offend Cleopatra. But if he sent his wife Octavia, sister to the Emperor, back to Rome from Athens, he knew that his "number was up" (to quote one of the sages of the period[*] with the Emperor.

[* Marcus T. Cicero, a literary person who had made a stir in Rome some little time before. Curiously enough, Mr. C. had a very poor opinion of Antony, and was in the habit of saying so loudly and frequently, until one day—December 7, 43 B.C.—he fell in with some soldiers of Antony near Formiae.—Author.]

If, on the other he permitted his Roman wife to come to Alexandria, he knew that there would he peculiarly deadly trouble with his Egyptian bride Cleopatra.

Clearly the ladies must not meet.

At the same time, he did not wish Octavia to lose the gifts which she was sending nor did he want the bearers of the gifts to lose their lives. They did not deserve it. He personally did not want the gifts, but— doubtful character though he was—he could not fail to realize that it would be decidedly "tough" to allow the gift-bearers to come innocently on to their doom at the hands of an entirely conscienceless recently promoted rat-catcher and his band of hooligans.

Then abruptly the solution struck him.

He turned to Hu Neh, and directed his attention to the bulging bag of gold,

"Seest thou that, Egyptian?" he asked.

"Yea, my lord."

"Desirest thou it?"

The assassin looked giddy, A sack of gold! Desire it? He gulped,

"Do my will, good murderer, and it shall be thine, said Antony, watching him.

"Will the noble Antony state his desire? It shall be done." stammered Hu Neh, his eyes glittering.

"It is this: Go forth as thou hast been ordered, but take few men. Kill these before thou reachest the camp of the gift-bearers. Hand a letter which I will give thee to the Lord Tullius Superbus, who is chief of the convoy. When he hath perused the letter, he will reward thee, and will return safely again to Athens with the gifts with which the most noble Lady Octavia hath entrusted him. Then return hither. Long ere thou returnest I shall have made thy peace with the Glory of Egypt, Queen Cleopatra. Dost thou understand?"

"Yea, my lord."

"Thou art not to harm even the least of the gift-bearers, nor to capture the least of the gifts! Mark ye that!"

"It is marked, my lord," babbled the assassin.

Antony nodded.

"It is good. I will see to thy great advancement when thou returnest. Meantime, tarry without while I prepare the letter."

Hu Neh left the room and tarried without, while Antony sent for his secretaries.

Evidently it was an extremely brief letter which Antony wrote, for within a few minutes Hu Neh was summoned to receive it.

"Be swift, be careful, and be faithful, assassin,§ said Antony. "Now, take thy gold and begone."

Hu Neh, thrilling, departed.

Leaving the palace, he deposited his gains at a place where they would be safe until his return, and then proceeded to select the two men he purposed taking with him—the two least capable-looking soldiers he could find. Bidding them prepare for a journey, he went to the royal kitchens for lunch.

During the meal he thought things over very carefully. Now that the gold was his own, and consequently the glamour of it had lessened somewhat, he was able to reflect more coolly. He could not disguise from himself the fact that he was playing a very risky game. If he did for Antony that which he had contracted to do, it was obvious that he was failing in his duty to Cleopatra. On the other hand, if he obeyed the Queen's orders, then it was equally obvious that he was "double-crossing" Antony. Either was an extremely dangerous proceeding.

Fortunately, the problem was simplified by the fact that the Assassin-in-Chief was not hampered by any morals. He was, in short, a blackguard complete and perfect. Consequently, it was almost immediately clear to him that the only course he could safely adopt was to carry out the instructions of neither Cleopatra nor Antony, but simply to leave Alexandria with his newly acquired fortune and never again return.

There was only one flaw in this scheme. He had not drawn any reward from the Queen. To one so greedy, so avaricious and crocodile-spirited as Hu Neh, this was little short of tragic; but there was no help for it. The only way he could see to squeezing any greater gain out of the transaction was to obey, partly, both the Queen and Antony. He thought it out with care.

"I will meet the convoy and turn them back," he muttered. "That wilt be obeying the Lord Antony. I will accompany them a little while, until I have gained their confidence; then I will kill them all"—he fingered his wallet of poisons absently—"and take their treasures, or as many as I and a good camel can carry. That will be obeying the Queen. But I will by no means bring the treasure back to the Queen; that would be foolish. I will keep it for my trouble, and I will settle down in Greece for the rest of my life. Good! It is settled!"

He paid his bill, and set out in search of the best and swiftest camel on the market. He was completely happy and full of hope. He saw his way clear to double-crossing everybody, except himself, and consequently all was well. He considered that he had arranged matters very cleverly indeed.

He set out upon his journey that evening accompanied by the two soldiers he had selected.

After supper he murdered, quietly and without fuss, both of the men. Then he slept peacefully for a few hours, dreaming pleasant dreams.

TWO days later, he rode into the camp of the

gift-bearers. He was in high spirits, and they went

still higher when he perceived, from the small size of

the encampment, that the company of messengers from the

Lady Octavia was but few in number. This was extremely

satisfactory—indicating, as the quick-witted ruffian

instantly realized, that the gifts, though probably very

costly, were easily portable, and also that it would

simplify the task of extermination which remained to be

carried out.

Challenged by two guards, the assassin halted and explained his business.

He was taken at once to the tent of the Lord Tullius Superbus, the chief of the gift-bearers, to whom he handed Antony's letter. Without dismissing the guards, Tullius Superbus, a keen-eyed, experienced-looking military person, read the letter. (Hu Neh long ago had endeavored to do the same, but it was written in a language he did not understand.)

Tullius Superbus nodded thoughtfully as he finished reading, and gazed at Hu Neh with rather an odd expression in his eyes.

"The Lord Antony's desire is that we return to Athens forthwith, Egyptian?" he said.

"Yea, my lord. And that I should accompany thee for a day and a night, lest thou shouldst fall in with Egyptian raiders."

Tullius Superbus beckoned one of the guards, spoke briefly to him, and the man left the tent. Hu Neh did not overhear what was said. Probably it was to do with the alteration of the route.

"Be seated," continued Tullius Superbus. "The Lord Antony writeth that thou art chief assassin to Queen Cleopatra,"

"It is even so, my lord," said Hu Neh complacently.

"And that thou hadst orders from thy royal mistress to slay us by stealth, and take the treasures?"

"Yea, Lord," agreed Hu Neh, "those were the orders—until they were countermanded by the Lord Antony."

The gaze of Tullius Superbus grew bleak.

"Thou art a bold man," he said. "Knowest thou that the Lord Antony is grieved because of the danger and treachery planned against us who come with gifts?"

"Alas," said Hu Neh, "I am but a servant, and I must obey mine orders—not question them."

"True," said Tullius Superbus; "that is true. A good and dutiful servant must obey his orders and refrain from questioning them."

"Yea, my lord, assuredly!" replied Hu Neh enthusiastically,

Tullius Superbus tapped the papyrus in his hand as the guard to whom he had spoken returned.

"There is a post script, Egyptian, concerning the bearer of this letter," he said. "I will read it unto thee."

Then, with a sudden shock, the assassin felt four brawny hands close upon his arms from behind. Then his arms were twisted behind his back, and corded together with a swiftness that stunned him. In two seconds he was helpless.

"Yea, I will read it unto thee," said Tullius Superbus, smiling gently. "Hearken:

"The bearer of this is a traitorous fellow, but the best to my hand. He hath betrayed the designs of the Queen unto me for gold. I do not doubt that he would betray my designs for silver, and 1 am well assured that he would betray thee for bronze. He is altogether a scurvy rogue, and totally deserving impalement. Impale him, therefore, ere thou returnest unto Athens.'"

HU NEH'S jaw fell. He stared into the eyes of the men he

had come to kill and rob, but there was no comfort there.

He was trapped—trapped—and he knew it. He had

been far too clever,

"A good servant doth not question his orders—he obeys them," said Tullius Superbus mildly, to the guards. "Take him out, therefore, and impale him!"

Hu Neh fell himself gripped and urged forward. He was literally stunned into speechlessness, It was incredible that he, Assassin-in-Chief to Cleopatra, should himself be assassinated in this heartless way; it was—

Hu Neh was stunned—it was incredible that he

should himself be assassinated in this heartless way.

His eyes fell upon a stake set up in the sands, and he started violently, seemed to stumble, and then fell forward on his face, shutting his eyes tightly. He made no effort to rise, and the momentarily expected grip of the guards seemed long in coming.

What had happened? Had Tullius Superbus relented—had the noble Roman been playing with him? Cautiously he opened one eye. He was lying face down, but the appearance of the sand outside had altered oddly. It no longer looked like sand but like wool,—colored wool,—red, with odd little veins and mottlings of blue and fawn running through it. Close by his head was a gleam of polished metal, like a brass sword. Something was hissing viciously close by.

HE opened the other eye—to discover that he was on

all fours on the hearthrug in his flat in Twentieth-Century

London, staring at the pattern of the rug with one eye and

the brass fender with the other,

The power of the pill had waned just as he had fallen out of his chair—upon Peter, his white-eared black cat, who was raving about it under the sofa close by.

But Mr. Honey had no sympathy to spare for Peter just then; all the sympathy he possessed he needed for himself. Trembling a little, he poured himself a stiff whisky, which he devoured without going through the formality of adding soda.

Feeling a little better, he lit a cigarette and wiped his brow, which was covered with beads of cold perspiration.

Then he spoke to the still-sizzling Peter.

"Awful!" he said. "Terrible! Begad, but I'm well out of that! Impalement, you know! Antony too, of all people! I always considered him rather a sportsman, but—well, it only shows one. Another half-second, and I should have—It's a good thing for me that the power of the pill waned when it did! And what a ruffian—what a scoundrel! I deserved it—yes, certainly I deserved it."

He took a further pull at his whisky,

"Chief murderer to Cleopatra! Fearful! What an appointment! And I was glad to get it, you know, glad! Oh, unspeakable! It is quite clear that, whatever I may be in this life, I have been, in practically all my previous existences, either a born knave or a born fool—and frequently both!"

Inspired by a sudden resolution, he rose and, with a hand that still trembled slightly, took the quaint Chinese bottle of pills, and going to a safe in a corner, buried it in the deepest depths thereof, and swiftly closed the door.

"There—at any rate, for the time being —you may rest," he said rather vindictively, "Tomorrow I go to Rye for a month's golf, It will take me at least that time even partially to blur the memories of what is quite clearly one of the most criminal pasts on record!"

And, so saying, he sadly bestowed upon the long-suffering Peter his blessing, and began to look up his clubs.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.