RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, July 1947, with "The Message on the Hearth"

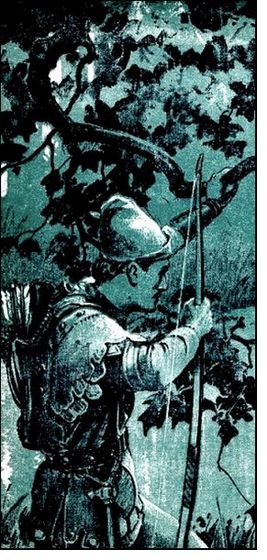

Slowly, soundlessly, he brought round his big bow.

This remarkable adventure in transmigration takes Mr Honey back to his exciting career as scout for King Alfred the Great and explains for the first time the legend of the burned cakes.

AMONG the various and subtle changes in the character and personality of the author whose pen-name was Hobart Honey—changes which his increasing familiarity with the effects of the Lama's remarkable pills[*] had brought about—was a diminishment of a certain innocence, ingenuousness or naiveté which he possessed when he embarked on the first few of his amazing adventures.

[* These pills were presented to Mr Honey by an immensely old and incredibly wise Tibetan Lama, to whom he had rendered a service. Each pill possessed the power, when taken, to return Mr Honey for a brief period to one of the innumerable lives he had lived before his present incarnation. —Bertrand.]

There had been a period when he sometimes hoped that he might have the good fortune to be returned for a second time to a previous incarnation in which he had been prosperous and happy.

For example, he would have been well pleased if a pill had returned him again to Rome to resume his career as the gladiator who was the great favorite of the patrician Lady Delyria; he would not have objected to going back to continue his career as Friar Tuck, close personal friend of Robin Hood and well-beloved acquaintance of King Richard; nothing would have delighted him more than to pick a pill which would again return him to his charming association with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden; or to many other of his happier incarnations.

But he had given up hoping for or expecting any such luck, for he had realized that the chances of such a coincidence were as billions to one. So vast, so measureless were the tracts of space and time behind him, so countless the number of incarnations he—like all other people—had lived through, that he knew the likelihood of returning for a second time to any particular incarnation was so slender that it could hardly be said to exist.

So, wisely, he substituted curiosity for hope, and nowadays when he took a pill it was much in the spirit of a man who gets on a train which is to take him for a holiday to a new place, hoping he will enjoy it, knowing he may not—but willing to take a chance, anyway. He was probably right.

It was in this spirit, at all events, that he took the pill which provided him with the solution of a simple-seeming historical mystery which has for over a thousand years puzzled many people throughout the world.

This was the mystery of the cakes which King Alfred the Great allowed to burn on the heath of the swineherd's wife who had given him shelter in her house during the stubborn defense of Britain in the year AD 878.

Like many people, Mr Honey had always casually attributed the mishap of the hungry king to his preoccupation with plans for beating back the invading Danes—a preoccupation perhaps intensified by too much old mead, a potent beverage in those days.

But this was not the case. King Alfred was as sober as a judge—more than many, indeed—at the time. There was a better reason than drink, for Alfred's preoccupation as he sat before the hearth, and a more serious one—as Mr Honey was to discover.

IT was on an evening shortly after that on which he returned

from the incarnation wherein he became the best-informed man in

the world about the circumstances attending the launching of the

Ark, that he downed his usual ration of good port and swallowed a

pill.

He emerged from the queer, tranced state into which the pill, as usual, threw him, to discover himself to be a Saxon party called Unwulf. He was standing on a long slope descending from a fortified place, or earthwork, known as Athelney, in Somerset, England.

He was looking back at a crowd of men standing by the great earthwork, waving a mixed assortment of weapons at him in gestures of farewell.

"Ah, the good lads!" he said; he flourished his own battle-ax in reply, then turned abruptly and strode away down the slope.

He was a tall, rangy, tough-looking, sinewy specimen, with grim, weather-worn features and a mouth like the edge of his ax. He was armed like a man who meant business—a big boar-spear in his brown hand, a bow and quiver at his back, a long sword at his side, and a battle-ax at his belt. Just for good measure he had a long deadly-looking and very heavy dagger in his boot.

Even so, he was not over-armed. He was carrying enough hardware to render him thoroughly dangerous; but he need it, for he was moving through perilous country.

For these were those highly-dangerous days, when the fierce and savage raiders and pirates from the continent, notably the Danes of that period, were specializing with no little success in raiding, harrying, burning and generally devastating England—a form of sport which they had more or less profitably carried on since the Romans had hurriedly evacuated themselves from Britain over four hundred years before.

Throughout that four centuries no Saxon man, woman or child had settled down to a night's rest with the certainty of getting it. At any hour of any night, or the day that followed, any Saxon was liable to wake—for a few brief moments—in a storm of steel and flame and blood. Their bedfellow, so to put it, was Deadly Apprehension, and their alarm-clock was Sudden Death. Gangs, bands, even armies of these invaders roamed at will over the countryside. No woman was safe; all men were in danger.

But the long nightmare had hardened them and in the end Alfred had come, shaking himself free from the accumulation of murdered kings, slaughtered bishops and nobles, and the myriads of massacred common folk. With a few other determined men he had set out grimly to cure the invaders of their red passion for invasion.

And like the wise individual he eventually proved himself to be, Alfred was not too choosy about the men he enlisted. He wanted them rough and he wanted them tough and he was not in the least interested in their school certificates or their social status. War-dogs, in fact, with a flair or passion for driving these murderous invaders to the beaches and there indulgently giving them the choice of dying on dry land or, if they preferred it, swimming to the bottom of the sea. And King Alfred had certainly picked a fine specimen of the professional war-dog when he entered Unwulf on his muster roll. Unwulf had been born on the outskirts of a bloody-minded war-maker's camp somewhere near the Rhine, and by a series of miracles had survived infancy. He had borne arms from the moment he could lift them.

"And much good they have done me!" he was never tired of saying loud and long to any listener in any land with the price of a keg or whatever was going. He had fought in many countries and had acquired a unique mastery of the tools of his trade. His vast experience had sharpened his wit till it had an edge like an adz. But an astonishingly long run of sheer bad luck plus a natural royal extravagance found him at forty about as rich as he had been at six months. Fortunately he had been endowed with a sense of humor which, though slightly more sour than it had been, had preserved him from going all brittle with cynicism. He had drifted into Britain years before on a rickety raft from a wrecked ship, and had lived on his wits—and his arms—most of the time between his arrival and his enrollment under Alfred's banner. A good useful, all-round adventurer, loyal to his friends, he knew how to get on with men and he was popular with the gentler sex—with whom his conversation and manners generally were characterized by an easy familiarity which made respectable people blink a little.

This, then, was Unwulf—bound on a special secret service mission connected with King Alfred, according to prearranged plan.

FOR the most of the hot summer day he swung along, covering

the miles with ease. He met few people—but that was because

he kept well away from the road, or what was considered a road in

those times. He favored the side-tracks and foot-ways, the

cattle-paths through thickets, or along the edges of woods. That

was sagacious, at least. For around any hill, or beyond any fold

of the downs land, or outside any wood, he was liable to run into

a band of marauding Danes, all of whom would be delighted to kill

any Saxon at sight.

It would have been worse than useless to throw his life away, for his mission was to make contact with the King. Alfred had gone out some days before, as was his way, to spy on the increasing numbers of separate Danish forces that were known to have poured into the country east, southeast and south of Athelney. No word had come from him, and at headquarters they were getting uneasy about him. Unwulf had therefore volunteered to see what he could do about getting news of the King. With the few people Unwulf met unavoidably—the swineherds, shepherds, hinds, beggars and homeless people—he usually got into a conversation which he quickly brought to a point where he could inquire if they had encountered or heard of a friend he was seeking—a wandering Welsh harper and minstrel who was more or less melodiously strolling through the south of England, en route for London. For this had been the disguise under which King Alfred had chosen to travel.

One only seemed to have heard of him—a lone wandering friar, unattached to any order known to Unwulf. He was a broken-nosed friar with the craftiest expression Unwulf had ever seen on the human face, and as lean as a wolf.

"A minstrel, sayest thou, friend?" said this person, eyeing Unwulf appraisingly. "A harper from the Welsh hills. Hm!"

He thought for a moment.

"Was he, perchance, a tall man of goodly countenance with a reddish-brown beard—and a generous heart? Such a man as might part with a groat to a starving friar? Blue-eyed, unsmiling and grave, like one who forever pondereth a difficult problem?"

Was he such a man as might part

with a groat to a starving friar?

"That is the man, Friar—cousin to me, and close friend!"

Unwulf took out a silver groat. The friar eyed it intently.

"Then, brother, we are well met. Such a man abode for a night and a day in the hovel of Walt the Swineherd, of Much Muckett Moor—ten fair miles ahead as thou walkest."

He turned, pointing.

"But two nights gone, was he there—a tall, muttering man! Ho, ho, thou wilt not find it hard to come up with him. He will not be forgotten for many a year in these parts!" said the friar. He chuckled, his beady eyes on the groat. "He hath made himself memorable indeed! I had the tale from Walt's wife's own red lips."

"And what did he, Friar, to make himself so memorable?" asked Unwulf softly.

"Forsooth, in times like these he did that the like of which not one man, nor woman, nor child would wittingly encompass—he neglected his supper, so that it was burned to a cinder and utterly destroyed! In times like these! He came unto Gurtha, the wife of Walt—"

But here the friar broke off abruptly, staring sharply at a distant wood. Something was glittering in the sun under the edge of that wood. Unwulf saw it also. The friar looked at him sideways.

"Steel? The Danes?" he muttered.

Unwulf nodded.

"I have no time to tell thee the story in all its richness," said the friar hurriedly. "I am westward bound, in haste! Go to the hovel of Walt of Much Muckett Moor and ask for the story from Gurtha."

He held out a filthy hand. Unwulf gave him the groat and was instantly alone; evidently the friar was not addicted to lingering in the vicinity of Danes.

UNWULF went on, carefully. But it was only a small party of

raiders. He watched them for a time, eating their midday

provision. Then they rode off to the west. Scouts, probably.

It was about midafternoon when Unwulf halted in the shade of a small woodland through which ran a stream marking off the wild waste on the north that was known as Much Muckett Moor.

He rested there for a few minutes, eating a crust from his wallet, after taking a drink from the stream.

It was just as he finished his bread that he heard a splash from behind a dense clump of holly on his left. He listened intently but heard nothing more.

"An otter? Nay, too loud—they take the water like eels! What, then?" he thought.

He edged soundlessly into the holly clump, and traversed it slowly till he could look out from it, unseen.

He was, in a way, expecting to see anything but what his eyes fell upon. It was none of the enemy he saw; on the contrary, he found himself staring with some interest at a woman who only too obviously had just stepped onto the bank from a refreshing dip in a little pool formed by a bend of the stream beyond the holly clump.

But it was not entirely the superb figure of the lady which held his attention. Indeed, he had only had about the same interest in ladies' figures as had the average soldier—no more, no less.

Nor was it the marked beauty of her face or the wonderful double plait of reddish-gold hair.

It was what she was doing that intrigued him.

There were two small heaps of clothes at her feet and she was staring thoughtfully at them. Then, like a person who has suddenly come to a decision, she stooped and picked up a plum-colored garment, shook it out and slipped it on over her head. It fell to her feet like a curtain unrolling. It looked like some kind of silk. Then she picked up a gold fillet and quickly bound it around her hair and moved to the pool, now bright in the sun and unruffled.

There she took a good look at herself—a long, lingering, admiring look while adjusting here and there the fit and hang of the dress.

Then she started a little, evidently fancying she had heard some sound. She turned, listening with strained intentness; then, evidently uneasy, she whipped of the head-band and the gown, and in violent haste drew on the ragged dirty dress of a peasant woman. Her fingers flew back to her hair and she clawed her thick plaits apart into a wildly untidy mass of neglected-looking gold. Then she hesitated, listening.

The bushes beyond her parted and a gigantic Dane stepped out. He was heavily armed and carried slung to his back a small bundle. The woman ran across to him, her air of caution gone.

Unwulf watched them embrace, scowling as her watched. For her saw how it was with them.[*] Slowly, soundlessly, he brought round his big bow.

[* Somewhat over a thousand years later this kind of woman came to be known as a "collaborator" —Bertram.]

She was chattering in a low, excited whisper, the man nodding as he listened. Presently he took the bundle, and dropped it on the ground, laughing. She was on it like a cat.

It was another dress, a brilliant frock of white velvet-like stuff, embroidered in a gold and blue design—a fine thing and a rare one, in those days.

The woman held it up against her body; she was flushed, excited and laughing.

And the hard eyes of Unwulf fell on a scarlet flower at the left breast of the dress.

A flower of blood—he knew it to be the blood of some Saxon lady, raided, despoiled and murdered not long before and not far away.

Unwulf ground his teeth as he watched. His hand went to his quiver hungrily, without sound, and an arrow glided out to his bowstring like a venomous snake.

Then the sudden squeal of a pig startled them all. The woman turned, swiftly rolling the dress, snatched a quick violent kiss, and was gone, running watchfully. She vanished in the thickets like a ghost.

The huge Dane looked after her, shaking with a silent laughter.

Then he faced round to the cover through which he had come. For a second he stood immobile before he moved ... And then it was not forward that he moved, but downward—stone dead before he hit the turf, face down. Unwulf's arrowhead had shattered his heart.

Again the pig squealed—nearer now. There was no sign of Unwulf; only the huge body of the Dane, face-down, occupied the little glade. A few moments passed. Then a wild-looking, fattish man, clad in a tattered leather-like skin, stepped into the glade. He was almost as broad as her was high, and looked like some kind of gorilla. Under one arm he carried a half-grown pig that struggled and snuffled, its jaws clenched together by the firm hand of its bearer.

The man saw the body of the Dane, went across and stared dully at it for a moment. Then he tied the legs of the pig, put it aside, and kneeling, began to rifle the Dane of everything on him.

Presently he too had finished and stolen away, a pig under one arm, a bundle under the other.

Unwulf came out of his covert, but he did not linger in that place. He looked briefly at the body of the Dane and retrieved the arrow which the man with the pig had ignored.

"A good shaft!" said Unwulf casually, and moved off. "A strange thing," he muttered as he went. "There was a naked woman in the glade when I came—a naked man when I left!"

Unwulf passed silently through the little woodland, halted in the shadows of trees on its northern edge, and looked about him with prolonged and extreme care before he moved into open country. Immediately before him were a few of the hovels which the peasants of those days had come to regard as homes. Beyond these rose a gradual slope leading upward to the moor which, dotted with small clumps of old oak trees, ran for miles east and west.

A man with a small pig under his arm was striding up the easy slope.

Unwulf nodded.

"That one will be Walt the swineherd," he said, without much interest. Evidently Walt had lost one of his herd, had come down to find it, had succeeded and was now on his way back to the hogs.

Far away to the east a great black cloud of smoke hung in the still air. Unwulf had seen that too often to need to think about it: Another town which had displeased the invaders! For a few moments the flinty eyes of the Saxon scout lingered on the smoke, his mouth grim. Somewhere up that way was King Alfred.

"Alone!" Unwulf reflected. "A lion among a pack of rabid wolves!"

He glanced at the westering sun and slowly moved across toward the hovel nearest the moor. It was slightly larger than the others, and he figured it would be that of Walt, for the swineherd of the village was in his way and after his fashion rather more important than the average tiller of the soil.[*] Even so, it was not much of a house.

[* The name of Howard, one of the proudest names in England, is said to derive from the ancient name of Hog- ward (Protector of the Pork) —Bertram.]

He hammered the lower half of the rough door with the butt of his boar-holer or spear.

At once the upper half of the door swung back to disclose a woman looking inquiringly at him—a youngish woman with a great mane of red-gold hair, a face beautiful with a hard and brazen beauty, greenish eyes and a notable figure. She was the woman of the glade.

"Give an old soldier leave to rest awhile and eat a crust in peace by thine hearth, mistress," said Unwulf.

She favored him with a piercing stare, then swung back the door.

"Shalt have better than a crust, soldier," she said. "Art going up against the invaders?" Her keen eyes played over him, and she smiled.

"Thy weapons are newly sharpened, I see. Thou hast come far afoot his day—the dust is thick upon thee." Her voice fell. "Never from Athelney? They say that good King Alfred hath strongly established himself in that place. Sit thee down; thou shalt have good faring here."

She sighed and her eyelids flickered.

"Walt's wife Gurtha hath ever a welcome for a good soldier," she said, busying herself about the dark untidy room. "What tidings hast thou?"

She set coarse hearth-baked bread and fat bacon before him, as he sat at a rough table on a stool. Her hand lingered on his shoulder as she reached over him to put a small wooden bowl of dark honey on the table.

"Honey from the moor," she said. "Thou shalt have mead anon; there is no better mead than that brewed from the moor honey. There is naught that I can find it in me to deny so goodly a soldier!" she whispered.

"Thou art the answer to a wanderer's dreams, mistress," said Unwulf stolidly.

He took out his dagger and totally reconstructed the shape—and size—of the bacon hunk.

"Didst thou say 'mead'?" he inquired. "Many a day and night hath flitted between Unwulf and his last horn of good mead."

She laughed and slipped through a rough doorway—little more than a hole in the wall.

Unwulf's deliberately dulled eyes followed her.

"She is like a beautiful venomous snake!" he said under his breath. "Swift to see—swift to allure—and swift as hell to strike! Ho, ho! What made the King of her, I wonder?"

She was at his shoulder again, reaching over with a horn of mead, that powerful drink.

"There is that which will restore what thou has spent on thy long tramp from Athelney," she said, leaning against him.

He slipped an arm over the over-inviting waist.

"Nay, mistress Gurtha, I have come from far beyond Athelney."

"Small wonder that thou art weary," she said. "Eat well—drink well—and presently thou shalt rest the night long. Never yet turned Gurtha a soldier from the door. Thou shalt tell the tale of thy wanderings, Unwulf!"

"When thy goodman Walt returneth at sunset, Gurtha —"

"He returneth not this night, Unwulf. I have but now said 'Good night' unto him. He driveth his herd to root in a new pasture at the farther side of the moor. Drink thy mead."

She took the horn and brought it back refilled, with a smaller one. She set both on the table, and brought another stool.

"Not often do the fates send to me for shelter and hospitality such a man as thou art, Unwulf. A soldier! There is that about a soldier which maketh me soft and pliant and melteth me! Many the wayfarer hath come to this small house, but they were not such as thou art!"

"But this is no road for wayfarers, Gurtha!"

"No road!" She laughed. "Yet within four days past these have halted here, to wit: a Welsh harper—a dreamer and a fool, that one!—some beggars, and a knavish friar!"

"A Welsh harper! Knowest thou his name? There is a cousin to me whom I seek—he is a harper. Came he from the west?"

"Nay, from the east, fleeing from the Danes," she said carelessly. "A goodly man, tall, bearded—but a fool. A serious man, with blank, unseeing eyes—not with such bold, such brazen, such inviting eyes as thine, Unwulf!"

"That is the man I seek. But thou hast misjudged him. He is no fool—never was a man less of a fool than my cousin! Didst learn his name?"

"Oswere of the Pool was his name among the Welsh, he said."

"That is my cousin."

"Yet he was a fool," insisted Gurtha, with a touch of contempt in her voice. "For, look you, he had not sense enough to save his own supper bread from burning under his own eyes! A hungry man!"

"A strange story, golden Gurtha," said Unwulf softly. "Tell me."

"He came weary and hungry—a goodly seeming man, but dull and cold in his manner. I gave him shelter and made him oatcakes for his evening meal. These I set on the hearthstone to cook, and because it was necessary for me to go out for an hour I bade him watch and turn the cakes and tend the fire. Mayhap I was longer absent than I thought—I know not—but when I returned to this Oswere, there he sat in the same place as if he had never moved, staring before him. At his feet were still the cakes—burnt to cinders. Under his very nose they had burned and smoked and fumed! Who but a fool could do this?"

"True, true! He hath changed greatly," said Unwulf. "Thou art right and I am wrong. Cinders, sayest thou, ha-ha! How is it possible?"

"Like stones—there they lie yet!" She pointed to a corner. "The neighbors come to see them, to laugh over them ... Let us have more mead. Walt doth not return this night. He is niggard of his mead, but I am not."

She took the horns to refill them.

Unwulf picked up one of the burned cakes or loaves, laughing loudly—almost too loudly.

"It is like unto a black brick!" he called. He glanced through the aperture in the wall beyond which she was busy at the keg, and turned to inspect the stones of the hearth. And sure enough, there he found scratched certain symbols in the quaint writing of the period. Only a man expecting some such sign would have noticed the figure 2—or rather its contemporary equivalent—with a hole next to it: 2 o.

Looking at the back of another, he could just discern among a network of little crisscross cracks and holes: 4 oo.

He brushed ashes off another, and found, scarcely perceptible: 2 ooo.

His eyes gleamed.

"Walt hath been here often than I dreamed," called the woman. "The mead runs slow—and low!"

"Have patience, O beautiful Gurtha!" Unwulf called, brushing off the next stone.

On it he saw: 2 ◊.

And on another: 3 X.

And on the last of the six black stones: 4 S.

He turned from the hearth, laughing, as she came back with the filled drinking-horns.

"A hungry man burning his supper, ho-ho! It is a tale that will live forever. A fool—assuredly a fool!"

She peered at him more closely. She was very quick.

"Thou art excited!" she declared.

He took a pull at his drinking horn.

"Aye! It is the mead," he said. "And thou. Enough to excite a stone image! Come, thou lovely thing!"

He pulled her to his knee.

She came willingly enough, her eyes glittering.

"Here I am. Here for a little let us linger so. Tell me tales, Unwulf, soldiers' tales. Tell me of the brave men that the good King hath gathered together at Athelney. Is it a great host? Great enough to assure victory over the invaders? Trained men and well armed? Oh, I am hungry for victory. Tell me—it is like music, my Unwulf—music!"

Her warm arms were at his neck; her treacherous lips sought his.

A knocking jarred the door. She sprang from him and opened it. A soldier standing in the twilight asked if one Unwulf had halted there for the night. He had been told at another hovel that a stranger had come to Walt's house.

Unwulf was at the door like a springing cat.

"Thou, Berthold!"

Unwulf's exclamation was convincingly surprised.

"It is an order, Unwulf. Thou art recalled."

"Why?"

"There are certain accountings—" murmured Berthold.

Unwulf laughed.

"Ho-ho! They think the old soldier hath dipped his fingers into the supplies!" he said. "So be it, Berthold. Tomorrow at dawn I return! Come, I will see thee away! Here!"

He passed his drinking-horn of mead to Berthold and turned to the listening woman.

"I return in a space of minutes. I go but to see my comrade on his journey."

She laughed.

"See that thou dost not linger, O my Unwulf," she said. She closed the door behind the men and darting to the place wherein she kept her loot, drew out her dress, comb and the gold fillet.

Out in the twilight the two men halted by a tethered horse.

"Well followed: timely as a miracle, comrade!" said Unwulf. "Listen—let each word be engraven on thy mind as on stone. There is word from the King! I am in contact with him! Listen—there are at Swanage four thousand Danes![*] On Cranborne Chase, encamped, two thousand, and at Sarum three thousand. At Shaftesbury two thousand; on the western edge of the forest, two thousand in reserve. At Heytesbury four thousand! Note that well, Berthold! Men, we have them! Seventeen thousand! By God, we shall wipe them out. It is from the King himself! The Welsh harper! The fool who burnt his own supper!"

[* 4 S—and so on. A simple prearranged code. Curious that for a thousand years it has been left to me to explain and the Blue Book Magazine to publish! —Bertram.]

He gave a low exultant laugh.

The scout repeated the message and mounted.

"Good, good! And timely, as thou hast said, Unwulf. For already the army is moving!"

He disappeared at a gallop.

Unwulf returned to the house—and to a surprise. He had not been away more than ten minutes, intent on conveying the cipher on the stones to the messenger scout following him up for any information he could glean, even as he—Unwulf—followed up that master-scout or spy, King Alfred.

But much had occurred there in ten minutes.

He swung through the door with a jest that died on his lips.

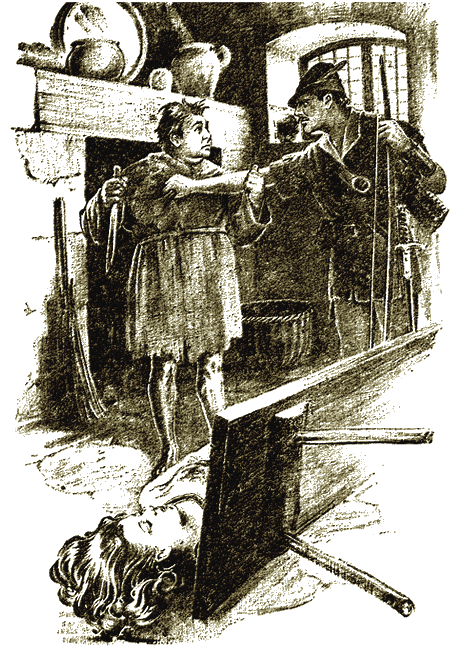

Walt the swineherd had come home. He was standing in the room—short, thick, powerful, shock-haired—staring down at the traitress.

There was a fillet about her wonderful hair—but it was a scarlet fillet. For Unwulf's eyes she had slipped on the white velvet gown with the red stain on the left breast—but the stain was larger now. She was quite dead.

Walt turned on Unwulf like a boar.

"Thou hast killed her!" said Unwulf.

"Hast thou killed her?" said Unwulf.

"Yea, I killed her," growled the swineherd. "For, wit ye well, I saw all that befell in the glade but a few hours gone. I saw her in the arms of the Dane. I saw her steal away at the squeal of my lost pig that I had found. I saw the dress the Dane gave her, stained with Saxon blood. I saw thee drive thine arrow through him. And I came away and went to the moor to think, for I am a slow-minded man. Up there on the silent moor I judged her and I found her guilty. So I came down from the moor unto her! Did I well, or ill?"

"Thou didst well! She was a traitress. Whence came she?"

"From an eastern shire, she said; they had driven her out as a witch. And she was glad to wed with me; I was as a shelter to her then. But always in her heart she despised me, though I kept myself washed and shaven as she demanded ... Yet I am blasted with sorrow."

"I say thou hast done well. Do not grieve! It will pass, comrade. How many lives would she have spared, of twenty thousand Saxons—had she had her way? Not one!"

They looked down at her.

"I would not have believed that one so beautiful could be so evil," said Walt simply.

Then a man came silently to the threshold. In the last light of dusk, they saw that he reeled with fatigue.

"Thou again, harper!" growled Walt. "No cakes for thee to burn this night!"

"Harper!" cried Unwulf. "By God, it is the King himself!" And he sprang to the salute.

Then he snatched forward a stool.

"Mead, Walt, quickly, and food! His Grace is far spent!"

The King sat down, his eyes on the dead woman.

"What is this?"

"A traitress, my Lord King! Doubly traitress—to the Saxon people, to her own man! Therefore, he killed her!"

Alfred rested his elbows on the table and put his chin to his palms.

"This is she who made me certain cakes that—became burned," he said. "Hast heard aught of that foolish thing? It was in my mind that the tale of such a folly might spread—and attract thy attention—to my discredit, thinkest thou, Unwulf?"

"Nay, My Lord, to thy glory! For I heard the tale and guessed thine intent. I read the message on the stones—and it is even now flying by Berthold back to those at Athelney, who will know how to profit from it!"

King Alfred drew in a great breath.

"Thou didst well, Unwulf; I shall not forget thee. We shall drive the Danes into the sea!"

He took the mead Walt brought, and was the better for the full horn of it before he spoke again.

"Let the swineherd travel fast through the night by the short ways he doubtless knows, to Athelney, and report that I am here, and here will plan my battle. They must come fast! Thou wilt remain with me, Unwulf. In an hour we will talk."

He pushed the food aside, too weary to eat.

"I have not slept these many days," he said, and laid his head down on his arms.

Walt snatched up the food which the King had left, turned to the door, then hesitated. He looked at the white form on the floor, then mutely turned his gaze on Unwulf.

The adventurer understood.

"Leave her to me, Walt," he said. "I will do that which is right for sinner as for saint."

Then with a low mutter of thanks, Walt was gone.

When the moon rose, Unwulf buried her.

Then he returned to the house, prepared a few things against the King's awakening, and put himself on guard at the door, looking out to the west.

He knew with a curious certainty that the star of the King was at last in the ascendant, that victory was assured.

He sat on his stool at the threshold, dreaming in the moonlight. The summer night was warm and drowsy about him. Behind him, the King slept the deep sleep of restoration, and Unwulf smiled a tight-lipped smile of complete and dreamy content.

He nodded—nodded ...

Then through the night he heard distant horns, drawing nearer and nearer till the din was deafening.

"They come!"

He woke with a violent start.

BUT it was not the horns of the marching Saxon host he

heard—it was only the low booming of a clock as it struck

the hour in Mr Honey's flat —as though to signal his

return once again to the century he believed to be the best of

them all.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.