RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

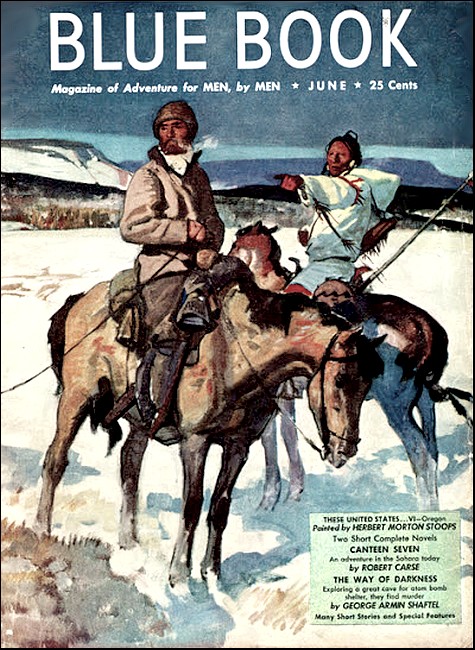

The Blue Book Magazine, June 1943,

with "Stowaway Aboard Noah's Ark"

TO pretend that Mr. Hobart Honey, in any of the incarnations rendered accessible to him by the Lama's remarkable pills,[*] ever proved to be a person of any high principles would be to pretend wrongly. He never returned to any incarnation whatsoever in which he was not full of principles—surfeited, in fact; but they were not Twentieth Century principles.

[* Presented to Mr. Hobart Honey, a middle-aged author of the present day, by a very aged and wise Lama from Tibet, these pills each had the power of returning Mr. Honey for a time to one of the innumerable lives or incarnations he had lived before. Although the pills had landed him in many strange situations he had become a pill-addict. This for the benefit of new readers. Bertram.]

Take, for example, his experience aboard the Ark, way back sometime. If he—But it is better, perhaps, to begin at the beginning. It was several evenings after his experience with Catherine the Great that he swallowed another of the Lama's pills, cascading it down with a double snifter of port wine that made perfectly sure of its transit past his glottis. He emerged from the familiar and temporary unconsciousness which followed, to discover him to be doing a little riding. If he had still been Hobart Honey of these days, he would have reined in a little; but he was no longer a fairly respectable author of modern times. He had been projected back to an incarnation in which he was Hunezzar, a horse artist—of a kind—in Assyria, or as they called it in those remote days, Akkadja.[*]

[* Formerly Sumeria. They were always altering the name of the country in those days. Half the people did not know where they lived. —Bertram.]

As his mind cleared, he realized that this was no time for reining in. On the contrary! For he was riding what was notoriously the best Arab mare in all of Arabic Asia. Against time!

Her name was Melek: and she was scheduled—in Hunezzar's mind—for delivery to an enormously wealthy old gentleman who had a vast estate on the banks of the Euphrates—a man named Noah.[*] Hunezzar, who lived a very long way south of Noah's place, had heard from an itinerant horse-dealer that the old gentleman was getting together a bit of a collection of animals, and with this end in view, was paying unheard-oŁ prices for specimens.

[* Noah was the name by which be became known later. His name, among the Assyrians, was Khasisadra or Xisuthros. Most well-informed historians agree with me about this. Probably changed it to Noah for easier pronunciation. Not at all sure but what I should have done the same in his place. —Bertram.]

"But hearken well unto me, Hunezzar," this itinerant party had said: "They have got to be good animals—in pairs—he's and she's. Half-bred or mongrel stock his Lordship hath no use for. He turneth it down like a flash. Tried to sell him a specimen couple of dogs I had by me. The old gentleman took one look at 'em—nice dogs, in a way—kind of setter-gazelle-hounds with a mite of terrier blood in 'em, maybe. 'What are these?' he said. 'Cat-hounds? Take them out of my sight! They are raising my blood pressure!' I took 'em away quick. Very austere old party—eyes like double-frozen ice. But money, Hunezzar! Sold him a beautiful pair of Bactrian camels I had. Hundred gold shekels—weighed out on the spot. Tried him with a brace of horned vipers I found—these cerastes, thou knowest: they coil up under the desert sand—but His Lordship was well stocked up on pizenous serpents, he said fairly unto me.

"Friend of mine sold him a brace of skunks—five shekels apiece. Dear skunks, I thought. Never thought of them as valuable, thou understandest. Knowest thou anybody got a brace of well-bred white rhinoceroses for sale? Or a pair of African blue gnus? Wildbeestes, methinks he called them. Or I'll trade in a good quiet old cross-bred bear-cat for a brace of pedigree stinging lizards if peradventure thou hast any. Hast any rattlesnakes? No. I forgot—no rattlesnakes. Serpents is out. Well, I must be getting along, Hunezzar. Keep the sand out of thine eyes!"[*]

[* A form of "Au revoir" much in use among the Assyrians. Practical, in a way. —Bertram.]

The man had moved on then; but Hunezzar, who had recently gone broke, had not forgotten his words. Indeed, he had remembered them so well that at sunset he had promptly stolen the magnificent Arab mare Melek and started for the Lord Noah's place up the Euphrates. Not a man of high principle, in that or any other incarnation. Horse-stealers have never ranked high in the social scale in any age.

But Melek was a hummer. Worth five hundred gold shekels to a wealthy lord like Noah, figured Hunezzar, and he was burning up the plain of Shinar to prove it. It was of course a one-way trip. There was no returning possible. If Melek, at a full gallop that was like a dream of flying, failed to please the old gentleman up the Euphrates, Hunezzar would be in the vermilion. For he had to go on, any way. If he turned back, there was only one party waiting for him—and that was a serious-minded old fellow who was wholly composed of bones, a toothy smile, eyeless sockets, and no hair, who carried a reaping hook in his fleshless hand. No, on the whole, Hunezzar had to keep going.

No man has ever ridden a first-class Arab mare without loving and admiring her for her courage and beauty; by the time the horse-stealer was hear the end of his long journey, Melek was the apple of his eye.

He watered her and rested her at an oasis some distance south of the Lord Noah's place, gave her what food she had carried so gallantly for herself, and settled down to enjoy the victuals she had carried for him.

He watched her nibbling about the oasis pool as he finished his meal.

"Beautiful! If the Lord Noah rejecteth her, verily I believe I shall not grieve—"

He broke off to leap to his feet with a yell. A lioness had launched herself from cover that was much too close to the lovely Arab to give her even the slightest chance. Almost before she had thrown up her beautiful highbred head, the charging death had leaped and delivered its terrible stroke.

Melek dropped with a broken neck, and the half-starved lioness clenched close to her.

Hunezzar snatched up his bow, and notched one of those frightful Assyrian arrows, almost as thick as a modern broom-handle, to avenge the mare. But this was no matter for revenge. The lioness was not alone. He saw out of a corner of his eye another like her, charging him. She was coming like a raging thunderbolt. There is on this jolly old earth no more menacing, living thing to face than a charging lion. At the last three yards she opened her mouth—and Hunezzar gave it to her full in the armed red cavern she displayed, leaping aside-as the arrow sped.

IT was lucky for him that this was a pair of lionesses,

ravenous for food. Another of those great arrows through

the heart sent his lioness into another and, one hopes,

less violent incarnation. The beast on the body of the

mare turned only to snarl at him. If it had been the

lion—the mate—of the dead lioness, things might

have worked out differently. As it was, the first lioness

turned savagely back to the dead mare.

Hunezzar notched another arrow and went to her. There was not much in the lion line they feared, these Assyrians. She turned reluctantly from the blood of the lovely thing she had killed.

And Hunezzar filled her and fulfilled her with his huge arrows....

But two dead lionesses are of no value to a gentleman in the business of supplying livestock to a livestock buyer.

It was very awkward.

HUNEZZAR sat down in the shade of a palm and thought

things over. And the more he thought over, the less he

liked them.

He could not go back to the old home town. He owed too much there—and he had "borrowed" Melek too long to make it anything but a plain case of horse-stealing.

And what was the good of going on? He had nothing to sell to the wealthy old eccentric Noah. Not even a pair of jerboas, or desert rats. He might have found a brace of vipers somewhere in the sand—but Noah was not in the viper market.

He looked up at a couple of vultures which were circling around, looking at him and the dead lionesses. They were about twenty thousand feet out of his natural reach, and in any case, Noah almost certainly was stocked up on vultures.

He looked at the dates on the nearest date-palm. They ripe enough to eat for a month to come. He looked at the lionesses—but he did not care for lion-meat. Did not suit his palate—too rich for his blood....

He looked at the still carcass of the beautiful Arab mare. No, he could not see himself eating Melek.

And that settled it.

He could not go back to be hanged; he could not stay where he was to be starved. He could only go one way—forward.

He laughed, for he was a reckless, agile-witted rogue.

"Forward, Hunezzar," he said, as if he had the choice of every point of the compass.

"I and my sense of humor can conquer anything—I hope!" he said, and moved out into the desert.

As he went, he thought hard, striving to recall everything he had heard about Noah, it wasn't much. And it had been pure gossip. The Assyrians were a great people in their way, but they lacked telephones, telegraphs, newspapers and radio. But they had camels, and most of the news came by camel or camel-riders. It was battered up a little by these camel-sharps by the time it arrived, but it was better than no news.

HUNEZZAR concentrated on it as he strode across the

sand, traveling north, but edging a good deal toward the

west, where the Euphrates River ran.

He recalled hearing that Noah had prophesied that very shortly there would be occurring a flood and a deluge that would make all previous calamities of the kind look like a minor overflow of the village creek, and that he intended building himself a sort of ship with which to meet the emergency when it arose.

Yes, Hunezzar remembered hearing that. And the animal-agent and dealer in wild beasts had told him something about this Noah planning to take aboard seeds and animals to restock the earth when it had dried up a little.

Well, that was reasonable enough—call for a fairishly sizable ship, but he was said to be a rich man, and probably could afford himself a yacht like many rich men before him. That, at any rate, had been the opinion of the wild-beast broker; and although there had only been about an inch of forehead between his hair and his eyebrows, probably the man was not far from an intelligent guess at the truth.

Hunezzar's spirits rose a little. He was pretty good with animals himself—fond of them, always had been, he reflected, and maybe there might be a vacancy on the beast staff for him. Would see, at all events....

TWO days later Hunezzar stepped out of the desert into

a huge fruit orchard by the riverside that marked the

beginning of the Lord Noah's great estate.

Hunezzar helped himself pretty freely to what was ripe, and took a rest. He noticed as he ate that the river was running pretty full and high, but even so, nothing desperately out of the ordinary. Not for the time of year.

He assembled himself about a bushel of assorted fruit, oranges, watermelons, and so forth, ready for when he awoke; and then he dozed off....

It was late afternoon when he opened his eyes again.

They fell on a girl who was standing watching him—an extremely attractive dark brunette, in a tattered leopard-skin which entirely failed to conceal a lovely, lissome figure that many a haughty Assyrian lady would have envied.

He sat up quickly, automatically smoothing his complicated plaited beard.

"Good evening," he said.

She smiled dazzlingly.

"And who art thou—and whence comest thou, maiden?" he asked gently smiling in his turn.

"Ah's no maiden, sah!" she said in a casual, matter-of-fact kind of way. "An' Ah's from Ethiopy!"

"Glad to make thy acquaintance," said Hunezzar politely. "Take a watermelon!"

She took one and sat down close beside him to eat the same. She was like a bit of high-class sculpture in dark marble.

They got to know each other better as time went on. Her name was Kandy. She was—or had been—the favorite wife of an Ethopian ras, or prince, who had led his tribe in an ill-timed and ineffective rebellion against the King of Ethiopia. He had been afflicted with the idea that he would be a better king himself. Of all the duly obliterated tribe, Kandy, an intelligent girl, had been the only one to escape; and for months past she had been engaged in the task of putting as many miles between Ethiopia and herself as she could manage.

But it had been a long journey-as all journeys of which the traveler does not envisage the end must be; and she was tired. Well, not tired in herself, she said, wiping watermelon juice off her charming little chin, but in her legs. All that walking!

IT had been Hunezzar's intention to go to Noah, and

having told of the misfortune with Melek, to ask the old

lord outright for a job—if only as a deck-hand or

menagerie attendant.

But in the course of conversation with Kandy, he discovered that he might as well alter this plan. The girl had learned a good deal about approaching total strangers with requests for help during her pedestrian effort from Ethiopia, and had spent the last few days scouting around and watching things from under cover.

Of the Lord Noah she did not appear to be a great admirer. She seemed half-afraid oŁ him, and conveyed to the Assyrian an impression that the old man was a tall, profusely bearded, overbearing, gloomy, sour and bilious person, very authoritative to strangers, practically tyrannical to his sons, sharp with his employees and definitely firm with animals.

He had one most grievous weakness—he was fond of prophesying. Had a passion for it, in fact, and if given his head and allowed to go his own gait, he would prophesy till he was black in the face. He had won a prophesying competition somewhere up the river a few years before, and never forgot it. Not a man of much blandishment, urbanity or charm. He consistently refused all requests for passages on the Ark he had built, though he persisted in prophesying the coming of such a flood that only the fish would be safe—and even they only just. He accompanied every refusal with an adjuration to the denied to take an ax and hie them to the woods and start shipbuilding on their own accounts:

"Or it were better for ye now to make rafts. There is not time to build ships. For the flood is at hand, and the outlook for the people caught out in it is but dismal!" Kandy, in hiding, heard him roaring at a party of tourists from Nineveh one day. But they had ignored his warning.

"And how beseemeth the Lady Noah, Kandy?" asked Hunezzar. "Is she too stern and, as they say in Babylon, stand-offish?"

Kandy said that Lady Noah was quite different. Kind and gentle and motherly, but at the same time, accustomed to having her own way. She had a quick temper, but it was soon over. Just before she met Hunezzar, Kandy said she was thinking of applying to the Lady Noah for a post in the kitchen, in spite of Noah's regulation that no strangers were to be admitted on any account on to the Ark, which he figured was already a shade overloaded.

"Is there any family, Kandy?" asked Hunezzar.

"They's three, honey—Marse Shem. Marse Ham an' Marse Japheth," said Kandy. "Marse Shem and Marse Japheth is married, but dat Marse Ham, he's a single gemmun. Dey workin' all de time, tendin' dem ol' animals. Ain't no chance for us folks abohd dis Ark! Guess we gotta keep on walkin', Hunezzar."

But Hunezzar was not so sure that walking was going to be the correct technique much longer. He had again stepped across to look at the river with Kandy, and it had seemed to him the stream was running discolored, a little fuller, lipping sulkily at the banks as if it would overflow if any careless person added as much as a gallon to it.

Kandy had noticed nothing out of the way. Hand in hand with him, she had stared out across the water for a while, then turned to Hunezzar, smiling.

"It jes' keeps rollin' along, honey," Kandy observed dreamily. "Lak me!"

"Yes, I know, Kandy. Hope the river contriveth to roll in the right direction, though."

But it did not.

By evening it was out of its banks here and there; and as they wandered from tree to tree picking their supper, a blob of rain the size of a large grape splashed on Hunezzar's face.

He looked up, and between the trees saw that the skies were filling with vast black clouds racing down from the north. Even as he looked, they blotted out the swiftly sinking sun.

"By the sacred beard of Ea, Lord Noah was right!" said Hunezzar. "Come, Kandy! There remaineth but one refuge: The Ark! Let us hasten!"

They certainly did hasten, Kandy leading unerringly toward the Ark, which she had reconnoitered so frequently in the past few days.

By this time they were out of the fruit orchard, on the edge of which began the great shipyard. In the center of this yard stood the huge completed vessel, resting on the ground like a kind of house or hotel or chapel, waiting for the arrival of the water to float her.

She would not have long to wait. There was plenty of material on its way to test her displacement. And it was not mere rain. A dull distant roar drew Hunezzar's head round. He had for a moment a view of the Euphrates through the flying rain-blobs, and he saw quite plainly what was on its way upstream—a towering tidal wave like the side of a mountain, swinging toward them at a fearful speed. It was still miles away, and extended far beyond each bank of the river.

Hunezzar caught one glimpse before the clouds opened up and the rain came down solid, bringing with it gigantic bayonets of lightning—so much of it, and in such a frantic hurry, that it seemed as if it were hunting for them, and every second getting more irritated at missing them. Mighty reverberations of thunder overhead seemed to be expressing hearty approval of the lightning's darting efforts. Hunezzar grabbed Kandy's shoulder and shouted:

"Run, Kandy—run like a gazelle! For the Ark!"

Then a fortunate thing happened, A medium-sized example of the rare spotted high-behinded hippopotamus broke away from three men who had just driven it aboard, and lurched back down the gangway. The men leaped after it, spurred on by the furious gesticulations of a big, bearded old fellow who rushed across the deck to the gangway. This left one complete side of the Ark untended. Hunezzar and Kandy reached it and went up the side like scalded cats.

"Down those steps. Kandy!" cried Hunezzar.

They went down the companion-way.

It was pretty dark downstairs. For a moment the fugitives paused, listening to the astonishing observations of Noah to his sons as they toiled to get the high-behinded hippopotamus aboard again. Then, not wishing Kandy to be shocked, Hunezzar led the way deeper into the dimly-lit bowels of the Ark. They were evidently on the cat deck—not much of a place. It was lit by a few rush candles, and the atmosphere was a little sharpish—or seemed so to people accustomed to the fragrant perfume of the fruit orchard. A child could have guessed that it was not the lily department.

The place was all cluttered up with barred-in lions and tigers, leopards, panthers, catamounts, cheetahs, jaguars, Tasmanian devils, ocelots, ounces and their brethren.

They went down to another deck, just as gloomy.

"What a hooraw's nest! Hooraw! Blast my eyes, what's it coming to! Hooraw! The binnacle's burst and the grog's run out! Who's this? Get the hell off my bridge!" said somebody suddenly, in a low sour voice. They stopped, startled.

But it was only a shabby old rusty-looking parrot, sitting by himself on the railing round a couple of quaggas, next to the zebras.

He surveyed Kandy with lackluster, bilious eyes, and imitated the sound of kissing.

Kandy laughed, and the uncanny fowl perked up, shifted itself into a more comfortable position, evidently settling down for a cozy chat. But Hunezzar, not liking the look of the bars round a mountainous and vicious-looking old bison bull nearby, hurried her on.

The parrot shouted after them—something about their being a couple of wharf-rats thinking only about their own skins, and leaving him there to drown.

"Go it, shipmates! Take to the blasted boats! You're all right, Jack-damn about me!" he yelled.

They heard him grumbling and muttering and swearing long after they had passed him.

SOMETHING came down out of the gloom to nuzzle at Kandy.

It was the head of a gigantic giraffe—perfectly

gentle, with great soft eyes, luminous in the dim

candlelight.

"Po' pretty ol' Miss Giraffe!" said Kandy, fondling it. Giraffes were no novelty to her. "How yoh lak dis ol' Awk, den? Yoh lak me, yoh po' ol' giraffe—yoh wanna go home, way, way back to Ethiopy!"

Then the foaming foothills, so to express it, of the tidal wave struck the Ark.

If heaved her nearly on end, so swiftly that most of the few candles went out instantly. Big and heavily-laden though she was, for a moment she pitched and wallowed, swung and rolled as if she must capsize, then settled, quivering. They could hear the vast waters roaring past the sides of the sturdy craft so loudly that it all but drowned the noise of the startled animals.

THEN a gigantic creature came shambling fast along the

dark gangway, muttering and gibbering hoarsely to itself.

It lurched between the stowaways, brushing them aside like

straws, then halted a second, picked up Kandy like a doll

and vanished.

It was a colossal she-gorilla.

Hunezzar turned to follow, but was snatched back like a feather and flung along the gangway by an enormous hand at his shoulder. It was the male of the mighty pair. He padded past Hunezzar, uttering a queer sound like a muffled roar, beating his huge chest with one fist. His enormous fangs were like the tusks of a wild boar.

For a few seconds Hunezzar lay half-stunned. He thought he heard a faint far-off cry from Kandy, and struggled to his feet. But a sudden roll of the Ark flung him off his balance, his head crashed against the stout bars of a rhinoceros pen near that of the bison, and he pitched to the floor, his skull all but fractured....

When Hunezzar regained his senses the rolling of the Ark had settled down a good deal. He was still lying on the floor of the gangway or passage. He had no notion of how long he had lain there. He felt sick and giddy. The sound of the waves had died down considerably: but all about him, and in every direction, was the sound of the lowing, grunting, or bellowing animals with which this deck was packed. They were hungry. Now and then the wild neigh of a zebra would rise shrilly above the tumult, and once the Assyrian heard the trumpeting of an elephant. It was now almost entirely dark.

"Oh—Kandy—Kandy—" whimpered the dazed stowaway. Then with a wild-effort he pulled himself together and groped his way along the gangway. He had lost all sense of direction, and guided himself by the feel of the bars on each side of him.

He staggered to a place where the bars were very thick and as far apart as the width of a doorway. He leaned against one of these great bars to rest. Then suddenly a huge thing—it might, have been a colossal python—reached out of the dark, encircled his waist, and drew him in past the bars. For a moment he felt himself as if he were dangling in the dark within this silent, mysterious loop. But there was no constriction, no terrible contraction of the mighty muscular coil above him; and almost immediately he found himself put down quite gently on what felt like a pile of hay.

Something went tapping, feeling, touching lightly over his face and limbs; he heard a great sighing sound like a vast expiration of breath overhead, and he knew then that he had been lifted carefully into an elephant's stall.

He was quite unafraid, sensing that his enormous host had no intention or desire to hurt him. He was quite right, though it was not until later that he learned that he was, so to put it, the guest of one of the gentlest, kindliest old elephants that ever came out of India—

He settled down in the hay, and in spite of the stabbing pain in his skull, slowly faded into the unconsciousness of sleep. He felt now and then the light touch of the trunk-tip, but that seemed more and more to merge into the stuff of a dream. At first it startled him a little, but a fugitive thought which went weaving through his mind that perhaps the great sighing creature towering over him was also lonely and glad of a little human company, somehow reassured him, and in the end he dropped off without a qualm for himself and only a vague fading dreamlike distress about Kandy.

IT was some hours later when Hunezzar woke, or was

wakened. It was still very dark in that vast hold or deck;

but above the murmur and movement of the patient beasts all

about him, he thought he heard a distant voice calling his

name. "Hunezzar!"'

He listened, half awake, half dazed. A bull penned far up the aisle began to bellow, starting a chorus which drowned everything. No, there it was again—very faint above the uproar of the animals—"Hunezzar!"

It was the voice of Kandy—gay, happy Kandy, who had been swept away into the darkness in the grip of the monstrous gorilla. He had dreamed of her—but he had dreamed that she was forever lost.

Yet here—not too far away—she was calling him. It sounded like the song of a bird at dawn.

"Hunezzar! Ah's a-comin'; so don' yoh hide no moah!"

He scrambled along the side of his huge companion of the night, unhindered, found the great bars and stepped between them. Far down the aisle was a gleam of light from a lantern.

Behind the lantern-bearer followed what looked like a load of hay.

But the carrier of the lantern was Kandy.

"Hunezzar!" She saw him and raced down the aisle.

Long before her excited greetings were over, the person with the hay had distributed his load into the pens and had come up to them.

"Oh, Hunezzar, honey, Ah thought you was daid or drefful hurt. I done come ez soon ez Ah could," cried Kandy. "Dis gemmun is de young Lohd Ham."

HUNEZZAR and Ham exchanged scrutinies. Hunezzar saw a

nobly-proportioned young man, inches taller and broader

than himself, who greeted him writh the friendliest of

smiles, and in the deep, rolling, musical voice of a

Robeson at his rollingest best to express it—bade

him welcome to the Ark. He laughed at the relief in the

stowaway's voice as he expressed his thanks.

"But the gorilla—that fearful apparition—I thought thou wert in their grip, Kandy."

Ham laughed his deep laugh.

"Nay, Hunezzar, they were affrighted at the tossing of the Ark. The gorillas are gentle—as all the beasts aboard are gentle.[*] In her fear and bewilderment she snatched up Kandy as she might have snatched up a child. My father saith it is but an expression of the mother instinct. I know not. Maybe it is as he saith. Kandy is safe and unharmed—art thou not, Kandy? But thou, Hunezzar, are bruised and hungry. Come with us, eat and rest!"

[* True. Hunezzar saw that later and secretly attributed it to some queer hypnotic influence over them exercised unconsciously by Ham. He could exercise it over people, too, as Hunezzar discovered later —Bertram.]

He turned to lead the way. An uneasy murmur and rustle arose from the animals—even the old elephant registered a low protest.

"Dey love Ham—all dese ol' animals. Dey don' wan' him to go," said Kandy.

"Why, Kandy, how dost thou know that so soon?" asked the Assyrian.

"De Lady Noah done tol' me," said Kandy. "Everybody loves Ham, she tol' me."

Hunezzar wondered dimly if that went for Kandy too; but before he could speak, Ham turned his bead, speaking over his shoulder.

"Distress thyself not, Hunezzar, if it should seem unto thee that my father maketh thee but little welcome. It is but his manner, and it will pass. He hath, had many vexations. But his anger doth not abide. It will abate."

No doubt Ham knew his father pretty well, but it did not look quite like that as Hunezzar's polite obeisance was acknowledged by the big, bearded, fiery-eyed Captain of the Ark—the Lord Noah.

Something seemed to have worked the old man up already, and Hunezzar's appearance came as the last straw.

He started on the subject of stowaways the instant he saw Hunezzar, and he kept on the subject for ten full minutes without a break or a repetition.

Hunezzar took it without a word. He only had to glance over the side to see what the Ark had saved him from. He felt that he could take it as long as the old autocrat cared to dish it out. Moreover, he had noticed a nice-looking, motherly, oldish lady sitting just behind Noah unobtrusively press her finger to her lips as he caught her eye—she was evidently the Lady Noah.

"Half the riffraff in Asia swarming aboard to overload the Ark!" Noah stormed. "I prophesy that grievous ill shall befall all them that come like thieves in the night—that—p'shaw—who art thou? Whence comest thou?"

"I am Hunezzar the Prophet—from Babylon!" said the quick-witted Assyrian.

"Hunezzar! I have never heard of thee! Thou a prophet! Thou! Bah! An amateur!"

"Nay, Lord—a professional!" declared Hunezzar. "A city prophet! Famed throughout the metropolis and far beyond. President-to-Be, my Lord, of the newly planned College of Prophecy soon to be established in Babylon!"

"Should it survive the Flood!" said Noah with almost a sneer. But there was a hint of uneasiness about the sneer. He was, after all a provincial, almost a rural, or rustic prophet. Nothing could alter that. He had not even visited Babylon for ten years. Locally, for miles and miles around, there had been nobody in his class as a prophet—but this stranger, this professional from the Big City, might it not even be that he was a little more advanced—up to date?

He moderated his tone a little.

"Prophet, hey?" he bellowed. "What dost thou prophesy when the mood is upon thee?"

"All kinds," said Hunezzar airily, "I prophesy anything from doom to triumphs—the Near Future, the Middle Future, the Far Future—anything!"

"Is that so?" said Noah. He hesitated, then came out with it.

"I challenge thee to a bout," he said. His folk were gathering round, and Hunezzar perceived that he must be tactful. Whatever form Noah had as a prophet, he certainly was Captain of the Ark—and there was plenty of room overboard for a spare stowaway.

"My Lord Noah." he said, "I will do my best, but think not that I esteem mine humble self to be of a quality which is more than slightly worthy of the honor of a match with thee!"

"Very well spoken," conceded Noah, relaxing a little. "How wilt thou have it? Alternating current or direct?"[*]

[* These ancient prophesying contests were either A.C. or D.C.—that is, fought out in alternating sentences uttered by each prophet in turn, or in one long, single chunk by each contestant. Audiences usually preferred the A.C. contest—snappier, not so gloomy, and more easily understood. —Bertram.]

"Alternating, if it pleaseth Your Lordship!"

"Very well," said Noah. He took off a nautical-looking kind of a hat he was wearing and handed it to his wife. Also his outer raiment. He looked as if he would have rolled up his sleeves and spat on his hands, if he had not been quite such an important person.

"Shem, thou shalt referee, if Hunezzar is willing."

"Willing, my lord."

"Ready?" snapped Noah, as he pointed to Noah. "Your lead, sir!"

NOAH raked his fingers through his beard, his eyes fixed

on Hunezzar, the Babylon outcast.

Then, suddenly, he led like lightning.

"The outcasts of the great cities are an abomination, and they shall be utterly destroyed!" he barked.

"The haughty of the land who comforteth not the outcasts and the humble shall perish and come to naught!" countered Hunezzar.

Noah came back like a flash.

"They that come up like fish from the deep waters shall be violently returned into the waters! Yea, in the weight of the waters shall they be flattened like the flounders of the deep!"

That was a nasty one. Hunezzar took it full on the chin. It rocked him a little, but he fought back.

"They that abide like fish in waters shall flourish like flounders! They shall comfort themselves like as the crabs of the crevices and wax exceeding fat!"

"For how shall it avail the outcast of the city if the city be crumbled in the waters? Whither shall he turn his steps if he be cast forth from his refuge? He shall strike out, but his stroke shall not save him. Though he turneth upon his back, yet shall the sun go down upon him and calamity shall descend upon him!" shouted Noah.

"How shall calamity injure him who hath slumbered in the protection of the elephant! He shall stride upon the dry land, and he shall restore and build in the shade of the vine and the olive and the fig!" bawled Hunezzar.

"The trees of the land shall be washed out, and the fruits thereof. Hyenas shall frolic in the groves of the orange and the shaddock and the pomegranate! The wild dog and his mate shall gnaw their bones under the shadow of the barren fig trees!" boomed Noah.

"The horned owls shall witness the safe departure of the pestered outcast ere even the hyenas arrive!" countered Hunezzar, who seemed to be weakening a little.[*]

[* Here Shem stopped the contest to warn Hunezzar that logically he was straying from the point—in the direction of a foul—for which he could be instantly disqualified. Like a modern boxer, for example, who suddenly bites his opponent's ear off. —Bertram.]

BUT Noah was only just warming up, and all of a sudden

he tore into Hunezzar like a giant refreshed.

"He shall be desolate upon the face of the desert! The gazelle shall flee from him, and the fruits of the palms shall be sour within him. The wild ass shall not stay within his range. He shall totter about! The vipers shall hiss at his coming, and the toad shall inflate and mutter in his throat at the sound of his footfall. When he cometh unto the river, the behemoth shall bellow and open up upon him! The crocodile shall issue forth, and the alligator-gars shall snap at his knees!"

Hunezzar reeled.

"Yet shall he not be utterly outcast. He shall rely upon—upon—that—that—he shall verily rely—he shall not be utterly—utterly—" he fought back feebly.

Noah balanced for the K.O. Hunezzar—everyone present—saw it coming as it were, right up from Noah's ankle. But he could do nothing about it. His lower jaw was aching and stiff.

"The outcast shall be as if he were never within. He shall be as a feather that floateth up from a scratching of fowls! He shall crawl into holes, and the denizens thereof shall expel him therefrom! He shall climb trees, and the branches shall break under his weight! The earthquake shall pursue him. When he avoideth the earthquake, his path shall be strewn with volcanoes. He shall lament, but his lamentations shall be no more than the stridulations of the bony grasshoppers! He shall be as an ant in an ocean! He shall not proceed forward, and backward he shall not go. If he goeth upward, it shall be as if he went downwards. Nor shall he revolve upon his own axis. And he shall then begin to enter upon trouble—"

Hunezzar threw in at this point. There was no use in taking punishment like this. As the figurative "outcast" he was washed up.

"He who beardeth the Old Man may expect that which verily shall be his—ha-ha! Hooraw!" said a new voice, rather like that of a radio commentator of a future age. They all turned.

It was a rusty-looking parrot sitting on the roof. Tired of the quaggas and zebras, probably.

Noah was pleased with his victory and did not mind letting people see it.

"My Lord Noah," said the astute Hunezzar. "Pardon the presumption which inspired the acceptance of thy challenge. It was as if a dumb man set forth to command the tornado to lie down and be still!"

Noah, however, was not a bad old sportsman.

"Nay, lad," he said benignly, "Thou didst not do so badly. Thou hast the makings of a prophet. Art in need of experience—practice—training! Thou wilt be aboard the Ark for many days—I wall give thee a few lesser bouts! Thou art not a good prophet—but thou art better than some I know!"

He looked around at his sons, but they happened to be looking another way.

"Thou shalt not be outcast, lad! And it is in my mind that thou mayest be hungry! And athirst. There is no more thirsty work than a prophesying bout. Come below!"

He led the way, bland with triumph.

AND so it went for forty days and forty nights. But

in the end there came a day when Hunezzar stood on dry

land with Ham and the charming Kandy, engaged in earnest

conversation.

"Thou broughtest her to the Ark, Hunezzar—and thine is the right to take her away. This I deny not. It is the prophecy and decree of my father that I go south to populate the land with my descendants. Do I go alone?"

Both men looked at Kandy. There was, after all, only one in it. She looked with wide serious eyes at the Assyrian; then her mouth quivered, and she moved to the Herculean Ham's side. She was, of course, right. They all knew that.

"Come thou with us, Hunezzar," invited Ham generously.

But the Assyrian shook his head. For a moment they all hung fire Then Kandy gave a long sigh. "Well, honey—is yoh comin' or is you ain't comin'?" she said with an effort.

Hunezzar smiled.

"I go north, Kandy dear!" he said. She looked at Ham, then ran to Hunezzar.

"Good-by, honey! Good luck go with yoh!"

She put up her face for a last kiss.

"Dear Hunezzar!" she whispered. "We jes' keep rollin' along!"

She tried to make it no more than a last little joke, but there were tears in her eyes. For it was sad—sadder than anything the prophets had ever pulled. It was a real prophecy.

Then she went back to Ham, and Hunezzar resolutely turned his face to the north....

It was not until he came to a green island in the far north that the power of the Lama's pill faded out.

"Here I abide," he said, "and here my descendants shall increase and multiply—a race fond of fine horses, and of charming women, generous, fiery, courageous in battle, lovable in peace!"[*]

[* Ireland, obviously. —Bertram.]

He stepped off the curious-looking ship which had brought him there—eager to fulfill his destiny. But it was not to the shore that he stepped; on the contrary. For it was at that moment that the power of the pill faded, and he stepped back into the Twentieth Century flat of Mr. Hobart Honey.

His eyes were absent as he reached for the port decanter, for he was taking a last look at a charming little figurine standing beside the magnificent, statuesque figure of Ham, son of Noah.

Then they faded out. He sighed, smiled and transferred his gaze to his wineglass.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.