RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

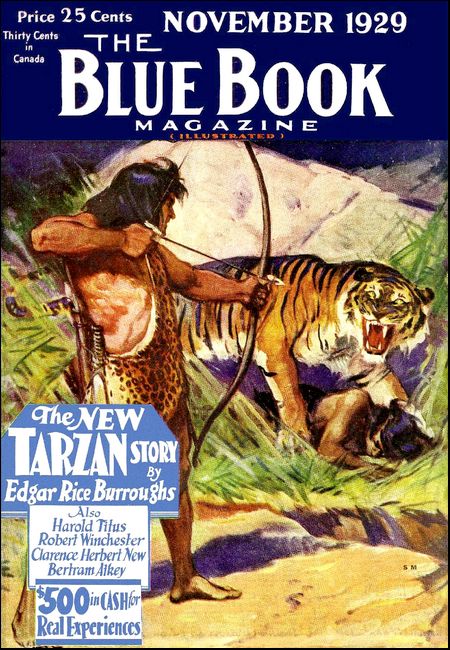

The Blue Book Magazine, November 1929, with "Hercules, the Horse Rustler"

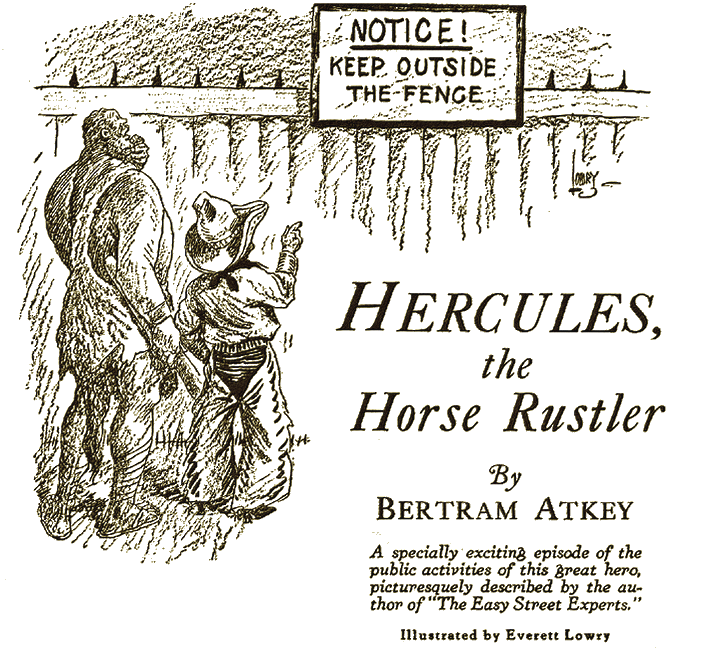

"Certainly he gives you fair warning, what?" said Hercules.

A specially exciting episode of the public activities of this great hero,

picturesquely described by the author of "The Easy Street Experts."

MORE nonsense has been written about Hercules than about any other character in history (observes Mr. Atkey). The person mainly responsible is Homer. But Homer has been dead for well over a couple of thousand years and it would ill beseem the present writer to say one word against a man who cannot answer for himself. Nevertheless, some one must defend the reputation of Hercules, and from no one can such defense come more gracefully than from a relative of this fine old Greek—viz., the present writer.

For the Atkeys are descended in a more or less direct line from Hercules, and thanks to the recent discovery of certain ancient documents in the family archives, Bertram of the clan is able to throw new light upon the life of the great Greek hero.

The facts in the case of Hercules, it now appears, are as follows: His godfather, a very influential party named Zeus, apparently being under some obligation to the father of King Eurystheus of Mycena, entered into a contract that the boy Hercules, when he grew up, should enter Eurystheus' service for a period of twelve years.

Herc was straight. When he grew up, and was some eight feet tall, he went to King Eurystheus and placed himself at the King's disposal. The services which Hercules rendered the King are fully described in these stories. You have read of how he killed the Nemean lion, of how he descended into Hades and came back with the three-headed dog Cerberus, of how he cleaned up the Augean stables, of how he captured the mad bull of Crete and of how he fetched the girdle of the Amazonian queen as a gift for the spouse of King Eurystheus. Here follows the first really authentic account of how Hercules, with the assistance of a cowboy, Red Bill, captured the man-eating horses of Diomedes.

TRIUMPHANT though the return of Hercules with the girdle

proved to be,—for the Queen was quite charming about it,

—nevertheless he found that it was high time he

returned.

For things at the country-house had not prospered during his absence. Within ten minutes of arriving there with King Eurystheus, Hercules perceived that his labors were by no means finished. Almost in tears, Eurystheus described how the stables had been devastated by a curious epidemic resembling glanders, which had quietly but swiftly killed off all the hunters, including Hercules' favorite weight-carrier, Pegasus.

"You've got everything right with the Queen, old man—that girdle will keep her quiet for weeks; but what we're going to do for a bit of huntin', I don't know. I'd give a lot for a good run, and you must be crazy for a gallop. It's getting serious!" grumbled Eurystheus. "Here's me, King of Mycenae—and I haven't got so much as a jackass in my stables or a chalcus in my privy purse. I'm not going to stand it. Look here, am I His Majesty the King of Mycenae, or am I not? If I'm king, then why haven't I got a few decent hunters for myself and some for a friend?"

And he shouted for the keeper of the privy purse.

"Back me up, Hercules, old man," he said hurriedly, as Stefanopoulos entered.

"Your Majesty desired my attendance?"

"I did," said the King coldly. "I desire you to go with the Master of the Royal Horse and buy twelve of the best hunters you can find. Let it be seen to at once." And he waved his hand in a royal gesture of dismissal.

THE jaw of the keeper of the privy purse fell with an almost

audible click. His eyes protruded considerably, also.

"But Your Majesty," he said, "the privy purse is empty."

Eurystheus whirled on him.

"Well, whose fault is that?" he shouted. "Yours or mine? Am I keeper of the privy purse, or you? Always the same cry—'Your Majesty, the privy purse is empty!'—to everything I say. By Zeus! I'll order one of the mariners to bring back a parrot from foreign lands, and make it keeper of the purse. It could answer me as well as you can—for less money. Do you think I pay you a salary of—of—Dr—how much do I pay you a year? I've forgotten."

"Nothing, Your Majesty," said Stefanopoulos apologetically.

"What's that? How much do I pay the keeper of the privy purse a year out of my civil list?"

"Nothing, Your Majesty," repeated Stefanopoulos mildly.

Eurystheus looked a little staggered.

"Well, how much ought I to pay?"

"Five thousand drachmae per annum, Your Majesty."

"Well, you'd better charge it in the account," said the King rather feebly.

"Thank you, Your Majesty. That is what I have been doing for the last five years," sadly replied Stefanopoulos.

EURYSTHEUS, a good-hearted man, melted. "Poor Steve! It's

awful, isn't it?" he said. "What do you live on, Steve?"

"Credit," said Steve.

"Too bad—yes, it's too bad. I'm sorry, Steve. Still, I do the same. I'll give you a medal, Steve, as soon as I can get a new case in. Do you think you could get a horse or two on credit?"

"Am I to answer frankly,—as a sportsman,—Your Majesty?"

"Certainly, Steve. I waive ceremony. We are three sportsmen together—without one hunter between us."

"Well, Your Majesty, I don't believe there's a horse-dealer within twenty miles that would let us know he owned a horse, much less sell us one on credit. And that, Y'r Majesty, is the stone-cold truth," said Steve flatly. "We owe for such a lot of horses already."

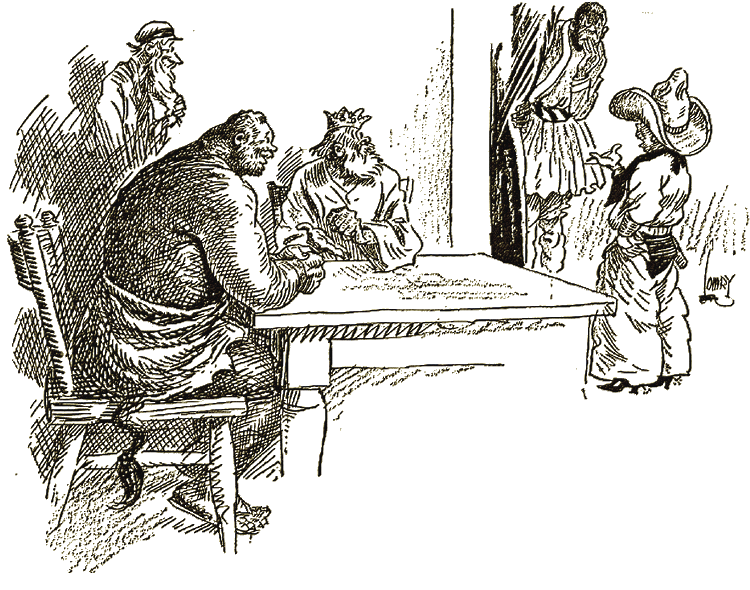

Eurystheus looked helplessly at Hercules, but before he could find an answer to this remarkably crisp presentation of the facts, a little disturbance was heard outside, the door of the apartment was suddenly opened, and there entered no less a person than Red Bill, who was still arguing over his shoulder with some one outside.

"Persona grata, as Lord Hercules puts it, bo'. That's me. You want to get wised up on your Latin, old man, before you start in trying to freeze a he-wolf from back of the ranges, like me, out of the King's apartment. You're too fresh, son!" And so saying, the cowboy turned to greet Hercules and Eurystheus.

Red Bill was arguing with some one outside. "You

want to get wised up before you start trying to

freeze a he-wolf like me out of the King's apartment."

"Why, hello, King—hello, Herc—howdy! I'm plumb glad to set eyes on you again," he said breezily, shaking hands violently.

"I've quit Augeas. I was shore weary of that old rattler. I've stood for his gold bricks right along, but when it come to settin' the cow-hands on to diggin' foundations for a new dam to take the place of that one you broke up on him, Herc, I shore kicked. 'No sir,' I says, 'I aint no mud-hoppin' granger. I'm foreman of the cow-hands. Me for Mycenae and my pal Herc, and a king that is some king!' So I draws down a fistful of back money, calls up my little paint-horse, and hits the trail away from that ranch pronto. And hyar I be. Say, you aint looking none too gay yourselves. What's bitin' you?"

They told him, briefly. He listened to the end in silence, his clear gray eyes twinkling. Then he laughed.

"Well, that all is shore most evil luck for two caballeros like you," he decided. "Can't you rustle a cayuse nohow? No? Then, say, what's the matter with Herc and me attendin' to it? Aint you never heard of them broncos of King Diomedes, up in the Thrace country? I guess you'd have to go a long journey to find better broncos, once they was broke to this hyar fox-huntin'. I aint never saw them myself, but there was an hombre working on the Elis ranch had; and say, that feller was plumb loco about them animiles! You'd better let Herc and me get away up to Diomedes' range, King, and stampede a few of them bronc's over here!"

He thrust his lean, brown, weather-bitten face close to that of Eurystheus.

"Is it a go, King?" he demanded.

"By Zeus, he's right, what?" said Hercules, throwing off his languor at the prospect of excitement.

Eurystheus hesitated.

"But those horses of Diomedes are the most notorious man-eaters," he protested weakly. "They are fed on human flesh!"

Red Bill grinned. "You give me and Herc orders to cut you out a few dozen out of the herd, King, and we'll get 'em to where they'll eat chicken-feed outer your hand in three or four days. That goes, Herc, don't it?"

"Certainly," said Hercules. "I wonder we never thought of it before, what? If only we had your brains, Red, we shouldn't have to go short of a bit of hunting. By Zeus, but those horses will be grand weight-carriers—grand!"

Eurystheus' face brightened.

"Very well, have your own way, you boys. Grab as many of them as you can. It's one of the scandals of Europe, the number of horses that man Diomedes keeps. Take a goblet off the sideboard, Red Bill, and you too, Steve, and we'll wish them luck. You'll be able to raise a trifle for their traveling-expenses while in Thrace, eh, Steve? The navy will supply the necessary ships to get them there and back."

"I'll do my utmost, Your Majesty," said Steve, and hung fire, hesitating.

"What is it?" asked Eurystheus.

"Well, Your Majesty, I was wondering if there was a possibility of Mr. Red Bill or Lord Hercules being able to get a couple of—Dr—nags for me. My old screw died this morning."

"Why, shore, Steve—shore," chimed in Red Bill. "We'll cut you out a pair of good 'uns, hey, Herc?"

"Stout fellows! Steve, make a note that I have appointed Red Bill to be Chief Cow-puncher to the King!" said Eurystheus; and he headed the procession to the wine-tank.

PRECISELY one month later, Hercules and Red Bill were to be

seen approaching a notice-board erected just inside a tall fence

running an enormous distance to the right and left of them, and

which marked the boundary of what Red Bill referred to as King

Diomedes' "range."

NOTICE

Keep Outside the Fence

Any Person Found Inside

The Fence or Doing Damage

To the Range Will Be

Prosecuted With the Utmost

Rigour of the Law, Should

They Escape Being Eaten

By the Horses on the Range,

Which Is Unlikely.

By Order,

Hy Jno. Smithopoulos,

Master of the Royal Herd.

Both men were mounted—Hercules upon a huge, powerful, upstanding roan horse which he had won as the result of a wrestling match with a local amateur wrestler at the port, who probably possessed more horses than skill; and Red Bill, as usual, was on his piebald cow-pony—his "little paint-hoss," as he was wont to term it.

They dismounted and drew nearer to the sign-board, studying it with interest.

"Say, Herc, Hy. Jno. is shore candid in his conversation, aint he?" commented Red Bill dryly.

Hercules laughed.

"Certainly he gives you fair warning, what?" he said. "There's another signboard farther down the line. Let's move along and see what else the good Smithopoulos has to talk about."

Mounting again, they cantered down to the second board.

If the Master of the Royal Herd had been frank in his warning to the public generally on the first board, the composer of the second was franker still. He was, indeed, deliberately insulting.

Hercules read it aloud—as follows:

"'Reward: One thousand drachmae will be paid to any person giving information which leads to the arrest or capture, alive, dead or half-dead, of the following two outlaws:

"'One. Alcides, alias Alcaeus, alias Heracles, alias Hercules, an Apache, highway-robber, jewel-thief, cattle- rustler, and horse-stealer from Mycenas. Height about eight feet, breadth about four feet. Features, fierce. Probably dressed in lion-skin. He is usually accompanied by a three-headed, barb-tail dog, answering to name of Cerberus, Cerb or Cerby.

"'Two. A party passing under the name of Red Bill, recently of the State of Elis. Was once a cowboy in employment of King Augeas, but being discharged for petty theft, became a noted horse-thief. Usually mounted on piebald pony, and carries a lariat, which he terms his "rope." Unprepossessing in appearance. A dangerous character. Probably will be found in company of aforesaid Hercules.

"'Whereas information has been received that these two outlaws have landed in the country of the Bistones for the purpose of stealing horses from the Royal Herd, know all ye and forget it not that all loyal citizens are called upon to detain, arrest, destroy, or slay at first sight either or both of the hereinbefore described depredators. No further authority is needed, and the production of the heads of the outlaws will be accepted as proofs, after a short police investigation, of their demise.

"'By Order of the King.

"'Jos. Ed. Joppemopoulos,

"'Chief of Police.'"

THE partners in adventure looked grimly at each other. To say

that they were annoyed would be feebleness—they were, for a

few moments, "plumb, hopping, crazy-mad," to borrow Red Bill's

somewhat redundant phrase.

"'Apache—highway-robber—jewel-thief— cattle-rustler and horse-stealer!'" Hercules said savagely. "I shall want an explanation of this, Red, before I start back to Mycenae!"

"Me too, Herc—me likewise."

Hercules calmed himself with a very violent effort, and stared at the board.

"Just a moment, Red," he said, and measuring the distance, planted a neat overhead swing in the middle of the board, utterly and eternally wrecking it. "And that's—"

He stopped short as a sudden thunder of hoofs broke in the silence.

"Something's stampeded some of the bronc's," said Red Bill quickly. "Mebbe you battering up the sign-board done it."

They hoisted themselves on to the fence and looked over.

Red Bill was right. Some fifty or so of the man-eating horses were thundering toward them. Red watched the brutes with a critical and approving eye.

"Some bronc's, Herc, believe me—some bronc's, though there aint a paint-hoss among 'em!"

The beasts halted sharply at the edge of a wide, deep stream which ran along on the inside of the fence, and throwing up their heads so that their red, flaring nostrils seemed enormous, neighed at Hercules and Red Bill—a dreadful neighing that was more akin to shrieking. There was in that terrible noise something uncanny. Every horse was black as ebony, and though heavier and much more powerfully built than any Arab, was distinctly Arab in type. A better description, perhaps, would be to write that they appeared to possess the bone and sheer strength of a very high-class weight-carrying English hunter, with the look of breed and the promise of speed of a first-rate Arab. But there any resemblance ended.

This herd of glaring, white-eyed, snapping, flat-eared, shrieking wild beasts—not one of which but could show half a dozen scars of old bites and plenty of new ones—was like a herd of runaway horses in an evil nightmare.

"Some bronc's, Herc," repeated Red Bill seriously. "There's shore goin' to be some rough work before any saddle is cinched up on them black wildcats!"

But Hercules' eyes were eager.

"Look at them, Red. Did you ever see horses more suitable for a man of my build? I've seen a lot of nags in my time, but never such a lot as this. Look at the bone there—and as much alike as peas in a bally pod, what? I tell you frankly, Red, that I don't leave this country without a cargo of these chaps on board!"

"What you say goes with me, Herc—it always did," replied Red Bill. "Do we sail in now?"

"No, no," said Hercules hastily. "We've got to find a quiet camp and proceed strategically. We shall have to tame these brutes as we catch them. And when we've got them on to a vegetarian diet, and a trifle tamer than they are now, we shall have to arrange about getting them aboard. It is going to be a long business, this, Red—but worth while, nevertheless."

Then the leader of the troop—a huge, raging, foaming demon, half-wheeled, rearing and snuffing. In an instant the whole herd were doing the same. Then, suddenly, like a pack of wolves, they plunged forward, and galloping furiously across the range, disappeared, evidently on the track of something of which the wind had brought them the scent.

The partners watched them until they vanished, and then, leaving their seats on the fence, mounted their own horses and proceeded toward a series of wooded hills in the distance, where they hoped to find a suitable site for headquarters.

"Apart from hunting, with those horses practically every race at every race meeting in Greece is ours, Red," said Hercules.

"Shore!" replied the cowboy. "If they don't eat their jockeys!"

BEFORE the partners had sojourned in the country of the

Bistones a fortnight, they knew practically everything worth

knowing about the herd of man-eaters which they were planning to

deplete. They had discovered, well inside the mountains bordering

the west side of the range, an abandoned hut, in an extremely

secluded spot. Probably it had been built many years before by

some hermit, or possibly a wandering prospector. This they had

joyfully taken over, mended the holes in the roof, chased out the

rats and snakes, cleaned it up and made it habitable. This done,

they spent a few days in cautiously reconnoitering the district,

selecting the best and quickest route to the coast, establishing

communication with the Mycenaean ships that were cruising about

awaiting them, and most important of all, in getting into touch

with the horsemen on the range.

They discovered a saloon down in a village between the range and the mountains, much favored by the range-riders, the proprietor of which, a Greek of a singularly cutthroat appearance, was himself an ex-boundary-rider for Diomedes, only resigning his position when one of the black demons had snapped off his ear.

The saloon was, not inappropriately, named "The Black Horse Hotel," and the adventurers lost no time in visiting it, slightly disguised.

Hercules decided to go in the character of a detective, specially imported from Athens, for the purpose of tracking down the desperadoes referred to on Jos. Ed's sign-board; while Red Bill's very sound notion was to pass himself off as a traveling dentist, for which purpose he procured, one night, from the doctor of the flagship, a few quarts of ether and chloral and a set of very terrifying tools, the mere sight of which was likely to convince anybody that the cowboy was indeed what he purposed claiming to be.

THEY paid their first visit to the saloon one evening

at about seven o'clock. Red Bill was to arrive first,

about half an hour before Hercules. They intended posing

as strangers to each other.

As they planned them, so things befell. Hercules, arriving promptly on time, found Red Bill surrounded by a profoundly interested ring of slightly inebriated horsemen, who were watching the cowboy making his simple preparations to extract the aching tooth of one of their comrades. He was, indeed, on the point of wedging open the horseman's jaws wider than the man desired—much to the hilarity of the company—as Hercules entered.

Nobody except the one-eared proprietor at the bar noticed Hercules, which was precisely what Hercules desired. He crossed to the bar and dashed down a gold-piece.

"Wine for the crowd," he said tersely. "Let me know when that's knocked down. Set 'em up!"

The burly saloon-keeper grinned, and biting the coin, bowed with true Grecian grace.

"Assuredly, sir," said he, and proceeded to "set 'em up."

Hercules leaned across the counter.

"And look here, What's-Your-Name—"

"Karkovokoulageorgeopoulos," murmured the Greek.

"All right, I'll call you 'Kark,' for short. Do you know what this is?" He opened his palm, and showed the little silver model of a polecat, which was the badge of the Athens Detective Corps.

Evidently Kark did, for he paled slightly, and his hand dropped to the knife at his belt.

"All right, all right, Kark, old man. I'm not after you—this time. I just wanted you to know who I am. I'm here for that great Mycenaean stiff Hercules, and his horse-stealing friend, and later on I want a quiet talk with you."

Kark, quite reassured, was intimating that he could give quite a lot of valuable information, when a long, inexpressibly anguished howl from behind, drew Hercules' attention to the fact that Red Bill was evidently on the point of concluding his dental operations. He turned abruptly as the cowboy staggered back toward the bar holding an immense molar in his forceps, while the patient, a huge person with an extensive vocabulary, expressed his opinion of the art of dentistry in a loud and penetrating voice.

Then the whole company surged to the bar. Noting their surprise at the sight of Hercules, Kark hastened to introduce him.

"Boys, shake hands with my cousin, Mr. Peloponnesus MacImbros, straight from Athens—where he runs one of the slickest little gamblin' halls, with a free-lunch buffet, just back of the Theater of Dionysus, as you'd meet with between here and Hades! He's been promising to visit me this five years—now he's here. And say, you boys, he brought along some of that there Athens dough,"—here Kark rang the gold coin on the counter—"and his first words was: 'Set 'em up for the crowd.' He's white all through, is Pel MacImbros—he always was. Pass him your lists, and shake!"

It was a rough-and-ready introduction, no doubt, but it served its turn. Hercules was certainly the most popular man in the bar from then onward. Nor did the subsequent extravagant squandering of much of the money scraped together by the harassed Steve diminish the good impression.

RED BILL, playing up like a little man, entered into a

friendly competition in the dispensation of hospitality, vastly

to the approval of the recipients. As is usual at these

functions, it gradually accelerated itself into a truly wild and

woolly evening—reminiscent, as Red Bill said later, of the

evenings they used to have back in the Elis cow-country before

Augeas "put every dollar in the country into the refrigerator."

Just before midnight Red Bill and Hercules seized an opportunity to consult each other.

The cowboy, it appeared, had an idea.

"Say, Herc, these range-riding guys is shore easy. I don't see no reason why we kain't get busy with their flocks and herds right now. What's the matter with having old Kark brew up a bowl o' punch, me dropping in a ladle or two of chloral. Then, when they're poundin' their ears, includin' Kark, you and me steals forth and cuts out a few of the herd. There's a shiny old moon, and we ought to get some haul—as many as we can manage. Mebbe we can stampede all we want right away down to the coast."

Hercules hesitated.

"But supposing the chloral finishes these toughs off entirely, what?" he demurred.

"Well, that wouldn't be such a bad finish, either," said Red Bill calmly. "For a crowd of vultures that earn their living in feeding them man-eaters with men, they would be shore merciful disposed of, Herc. Aint that right?"

Hercules saw the force of the cowboy's logic without difficulty, and agreed without hesitation.

"Very well, Red—carry on!" he said, and shouted an order to Kark to produce the materials for the punch which, as an acknowledged expert from Athens, he proposed to mix himself.

The thing worked like a charm, without a hitch, and though Red Bill was more merciful with his knock-out drops than his original dire proposal had suggested, nevertheless, within the next fifteen minutes, the range-riders and Kark, very sound asleep, were arranged in neat rows on the saloon floor, and left to their dreams, while Hercules and Red Bill fared forth into the moonlight to deal with the man-eaters.

But neither had noticed a man who, earlier in the evening, after one close scrutiny of them both, had quietly slipped out —and had not returned.

THE adventurers had not far to go to find their herd. Having

recovered their weapons, they merely went along the big fence

until they came to a gate and a narrow bridge leading across the

inner stream. They had already settled their plan of campaign

against the "broncos."

Breaking the lock off the gate, Red Bill entered the range, and standing on the bridge, proceeded to utter a series of singularly discordant wailings.

"Those black beasts will think it's some victims being delivered by the keepers," he explained. And he was right. Hardly had the last wail died away before the thunder of flying hoofs grew far across the range. Within two minutes they could see, in that brilliant moonlight, a big drove of the man-eaters galloping toward them.

"Ready with the bat, Herc? Right! Herc they come," said Red Bill, and stepped to the safe side of the gate, which he wedged open just far enough to allow of the exit of one horse at a time. Then, seizing a short, strong strip of rawhide from a bundle of similar strips, he stood back and waited, while Hercules fell into position just outside the gate, his club at "the ready."

The mob of man-eaters swept up, shrieking, crowding together to cross the footbridge. There was room only for one at a time, so that dozens were jostled into the water, and the banks being too high to climb, were swept downstream.

A big black stallion, which appeared to be the troop leader, was first across, and seeing the gap through the gate, with Hercules standing just beyond it, tore through with a maniacal scream. He leaped straight into a claymore swing from Hercules' club that spread him as senseless and safe as a feather-bed at Red Bill's feet. In an instant the cowboy bridled him with a rawhide, and muzzled him by the simple process of taking a few turns round the beast's nose and lower jaw. Then he passed the rawhide twice round the neck and knotted the end to the drawn-up foreleg at the fetlock. He worked with extraordinary speed, but he could not keep pace with Hercules. They had, however, arranged for this, and every second man-eater received a shot which put him out of action for ever.

They came streaming through the gap toward Hercules, who was working rhythmically, counting as he worked.

"One for Bill," he crooned, and bing came his club from right to left, spread-eagling a man-eater unconscious, at Red Bill's feet.

"One for the birds!" and wallop would come the gigantic club, swinging back from left to right, batting a second man-eater, stone-dead, to the right, out of the way.

As an exhibition of club-work it was magnificent—Hercules never missed, never killed the horse he meant to stun, never merely stunned the horse he meant to kill. Even for the admitted club champion of Greece, it was wonderful work.

As an exhibition of club-work it was magnificent—

Hercules never missed, never killed the horse he meant

to stun, never merely stunned the horse he meant to kill.

"One for Bill!" Thud!

"One for the birds!" Bat!

"One for Bill!" Wop!

"One for the birds!" Brump!

He sang it steadily, quietly, calmly putting the emphasis in the right place and keeping astonishingly good time.

Not until the last rawhide was used did Red Bill pause. Then he shouted, "Done!"

Hercules, with a yell, charged through the gate at the few remaining man-eaters.

It was all over in two minutes. Only four of the drove recrossed the bridge—and they recrossed it at full speed, with Hercules well after them. The remainder were sprawling about in various quaint attitudes of unconsciousness.

Hercules stopped and slowly returned. He closed the gate and rejoined Red Bill.

"How many did we get, Red?"

"Twenty-four, Herc—just the couple dozen. There they are—on the left. And twenty-four plumb dead!—on the right."

He faced Hercules, his eyes gleaming in the moonlight.

"And Herc, I got to say right here that you shore are the star batter in the team. Yes sir. You done right thar, Herc—what I should have shore swore was jest naturally impossible. Shake, pardner! The finest little old bung-starter expert in the world—that's you, Herc!"

And there in the moonlight these two simple children of nature shook hands.

Hercules was wild with delight.

"Twenty-four, eh? By Bacchus! Reddy, that's not half-bad business, what? Eight for the King, seven for me, six for you and, say, three for Steve. How does that strike you, Red?"

"What you says shore goes with me, Herc," replied the cowboy.

THEN their undivided attention was called for by the horses,

who were beginning to return to consciousness. After a moment the

first gained its feet, with some difficulty, and without pausing

to take stock of the situation in which it found itself, lunged

savagely at Red Bill. It merely succeeded in wrenching its lower

face sharply, half-choking itself, and bringing its fore-hoof

sharply against its jaw.

Two more attempts, with precisely similar results, convinced it that it was getting no adequate return for its labor, and so it desisted. Each of the others went through the same process, and arrived at the same conclusion, within the next twenty minutes.

And then Hercules and Red Bill started them off on their slow behobbled march to the coast.

All went well. The Admiral was on the look-out for them; the tide was right; and the men were willing; so that by dawn all but one of the horses were aboard.

It was at this moment that Red Bill, who was struggling with the last horse—none other than the big black savage stallion which had been troop leader—in four feet of water, perceived a crowd of troopers galloping along the beach toward them. One man, mounted on a magnificent animal, was well ahead of the others. Though they knew it not, this was the work of the person who had slipped out of the saloon to warn the King.

For a moment Hercules, who was in a smallboat near Red Bill, stared at the advancing horsemen.

Then he said: "Reddy, here comes King Diomedes and some of his troops. Cut this brute loose, and see what happens!"

Red Bill grinned, and swiftly cut away the rawhides from the neck and jaws of the big stallion. Hercules turned the beast to the shore with a horny-handed clip between the eyes, and as the big killer plunged for the land, he and Red Bill steadied the boat and watched.

The crazy brute shook itself once as it left the water, and then, screaming, charged the solitary horseman who had outridden the squadron—King Diomedes.

The tamed charger never had a chance with the raging devil just out of the sea. The stallion raced to it, checked it, and rearing, struck out its fore-legs like flying bars of iron. The charger went down with a shriek; and the man-eater, seizing the King, raised him, shook him as a terrier does a rat, and then galloped inland, carrying with it the dangling body of Diomedes. For a moment they all stared in silence.

The charger went down with a shriek;

and the man-eater, seizing the King,

shook him as a terrier does a rat.

Then Red Bill spoke.

"Finish of an hombre who is being handed what he has shore handed to a good many others. Aint that right, Herc?"

"Plumb right, Reddy," said Hercules absently.

And so they rowed back to the ships, en route for what Red Bill, later, was often heard to describe as "a spell of the roughest rough-riding he ever rode."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.