RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

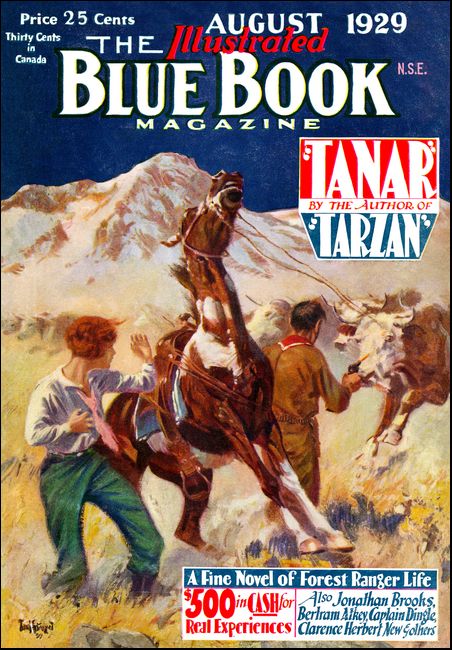

The Blue Book Magazine, August 1929, with "Hercules Cleans Up"

By tea-time Hercules had crossed the frontier and

was urging the leg-weary Pegasus across the park.

Further revelations of the private life and public achievements

of a great hero by the author of the Easy Street Experts stories.

THE Atkeys (explains the author) are descended in a more or less direct line from Hercules, and thanks to the recent discovery of certain ancient documents in the family archives, Bertram of the clan is able to throw a good deal of new light upon the life and labors of the great Greek hero.

The facts in the case of Hercules, it now appears, are as follows: His godfather, a very influential party named Zeus, apparently being under some obligation—of which no record is left—to the father of King Eurystheus of Mycenae, entered into a contract that the boy Hercules, when he grew up, should enter Eurystheus' service for a period of twelve years.

Herc was straight. When he grew up, and was some eight feet tall, he went of his own free will to King Eurystheus and placed himself at the King's disposal. The various little services which Hercules rendered the King are fully described in these stories. We have read of how he killed the ferocious Nemean lion, and of how he descended into Hades and came back with the three-headed dog Cerberus. Here follows, for the first time, the accurate account of how Hercules cleaned up the Augean stables.

KING EURYSTHEUS was worried—worried and annoyed. So

completely did he appear to have lost his usual habit of placid

good temper and calm that he was taking practically no

lunch—except perhaps a little more than his usual generous

allowance of wine.

The butler had rather nervously asked if the dishes were not to his liking, and had been given the cryptic reply:

"The lunch is all right. I only wish the other departments of my domestic affairs were up to anything like the form of the culinary department. Fill my goblet, and take all this food and yourself away!"

The butler had hastened to fill the goblet, and had then silently and wisely withdrawn.

Left to himself, Eurystheus took out a letter, already well-thumbed, and grumbling to himself, as a man will, reread it. Like most of the letters delivered at the king's country place, it was addressed from Tiryns, and was from the Queen.

"'I presume,'" he read aloud from the letter, "I presume that you and your gentlemanly companion Hercules imagined that you were playing a pleasant little practical joke when you sent me that triple-headed monstrosity (stolen from Hades) Cerberus, in response to my request for a good dog to exhibit at the recent dog-show. At least, I cannot bring myself to believe that it was your intention to insult your wife—but the great brute you sent has come near to making me the laughingstock of Tiryns.'"

Eurystheus pulled nervously at his beard.

"Why?" he demanded. "What for? I never saw a better sort of dog in my life! Hang it all, it was three dogs—and well-bred 'uns in one! She said she wanted something special. I suppose she thinks old Hercules went to Hades for a joke—that's it, a practical joke—to fetch the dog!"

He controlled himself and read on.

"'Had I but seen the monster,'" he continued, "'before arriving at the show, it would not have been so serious. At least, the insult would have been private, and I and our daughters are inured to your private slights. But Hercules, with his usual intelligence, took the beast straight to the show-bench reserved for it, and having chained it and removed its muzzles, carelessly left the building.

"'It should be hardly necessary to say that the awesome brute promptly broke its chain and, the attendants naturally being afraid of it, killed most of the beautiful little dogs on show and devoured many of them! It is not the expense of replacing these dogs, large though it will be, which annoys me so much, as the thought of what the populace will say. Straws show which way the wind blows, and perhaps you will realize that your clownish practical joke will do little to increase your already waning popularity when I tell you that the Princess Admete, when riding this morning, was actually hooted by an inebriated weaver, whom, naturally, I have had decapitated, limbed and flayed. I shall have more to say about this matter when you return to the city. The brutal monstrosity Cerberus completely fiascoed the dog-show, and I shall insist upon an explanation.

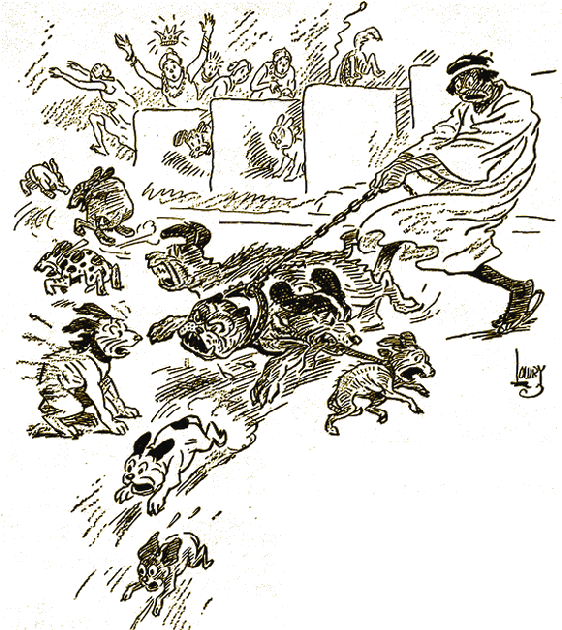

The awesome brute promptly broke its chain, killed most of

the beautiful little dogs on show and devoured many of them!

"'Meantime, there is another matter: There was a very pointed letter this morning from Augeas of Elis, in which he complains that you have taken no steps to carry out your promise to have his stables and stockyards cleaned out. Even you, absorbed as you are in your hunting, cannot have forgotten your contract to do this as part payment of his last year's bill for oxen supplied the Mycenaean army. This should be done at once. Augeas has been most patient; and let me remind you that recently his boy, Prince Phyleus, has shown a quite noticeable liking for Admete. It would be a very good match for Admete, who is no longer a child, and I assume that you have your own daughter's interests sufficiently at heart to keep friendly with Augeas. If you haven't, I have.

"'You are never tired of boasting of the great strength of Hercules. Very well, then: let him clean the stables. It would save great expense, and might teach him not to presume on the favor which you—most unwisely—have shown him. I have already sent word to King Augeas that you are willing to do this. Kindly, therefore, see that it is done.'"

EURYSTHEUS put down the letter with a good old-fashioned Greek

oath.

"There's a wildcat for you!" he spluttered, clawing at his beard. "What d'you think of that? There's a bit of pure Greek gratitude for you, if you like. Hercules goes down into Hades—Hades, mind you!—to get a dog just to satisfy a mere whim of hers; and because the dog isn't the right breed, nothing will satisfy them but that he should become a stable-cleaner—just to humiliate as willing a lad and as straight a rider to hounds as ever I took wine with! If she wasn't my own wife, I'm damned if I shouldn't call it low! Anyway, it's catty. I—I'm dashed if I know how to put it to the poor old chap!"

He flung the letter on the floor and began to pace up and down, muttering, periodically pausing to drain and replenish his wine goblet.

Whether he did this absently, or whether he was endeavoring to screw his courage up to breaking the unpleasant news to Hercules (when that individual returned from a visit to the kennels) it is impossible to say, but it is certain that when, an hour and a half later, Hercules strolled in, with Cerberus at his heels, King Eurystheus was, regrettably, in a condition which made the breaking of the news a matter of no difficulty whatever.

He greeted Hercules demonstratively.

"'Lo, Hercules," he said, "There's ba' news—sorry say—'stremely ba' news!"

He pointed to the letter.

"No doin's mine—nothing 'tall do with me, Hercules! Don't run away with tha' idea! No 'fair mine—not 'tall. Read tha' le'r. Read tha'—an' tell me wha' you think of sush wildca' trick. Queer wife o' mine. Nothing say agains' her. Bes' li'l wife all the world. Nashly. But read tha' le'r. Wildca' trick to play on frien' o' mine!"

Hercules read the letter.

HIS face hardened a little as he finished it. Then he looked

at Eurystheus. He perceived at once that the King was really

upset and distressed about it, and like the sportsman he was, he

permitted his face to resume its normal sunny expression, as he

flipped the letter down on the table.

"My dear old chap, you don't mean to tell me that you're going to allow a silly little feminine pin-prick like that to upset you—what?" he said.

The sheer surprise of it steadied Eurystheus considerably. He had quite decided that Hercules would be furiously angry.

"But dash it, old boy, there's thousands of stable-cleaners!" he stammered. "I could send a fatigue party of the troops over there—anything. Why should she insist on you, Hic-ules?" he concluded, rather cleverly disguising the slight hiccup, and adding "ules" thereto.

Hercules laughed.

"Temper, old man," he suggested.

"But—what will people say—what—"

Hercules suddenly smote the table with a fist like an anvil.

"I've got it, Eurystheus! Make a bet of it. Tell people I've backed myself to clean out those bally stables in one day, and that you've taken me. See? Sound scheme, that. What? It's a wager. When I've done it, send for some of those Tiryns poets, and tell them to commemorate it in verse!"

"I've got it! Tell people I've backed myself to clean out

those bally stables in one day, and that you've taken me. See?"

Eurystheus stared at him, his face slowly brightening.

"Old top," he said, solemnly, "you've hit it!"

"Absolute, bally bull's-eye. What?" And so saying, Hercules touched the bell, and ordering a large goblet to be brought, sank down upon a couch with the air of a man who has done a good day's work.

Eurystheus joined him.

AS usual, Hercules lost but little time in making his

arrangements. He started for Elis next day, riding Pegasus, the

old weight-carrying hunter which he had won from Eurystheus, with

the awesome Cerberus, who seemed to have become devoted to him,

accompanying him.

It says much for the genuinely sporting disposition of our hero that he had quite got over his temporary irritation at the deliberately intended insult of the Queen. He was no longer annoyed—and neither was Eurystheus. Beyond a pair of somewhat severe headaches, neither of them had brought to the breakfast-table anything remotely related to the darker side of the previous evening's trials.

Indeed, they had contrived, between them, to hit upon a scheme which, neither being a very brilliant business man, struck them as being extremely well thought up. Like many a king before him,—and since,—Eurystheus was not wealthy. He only seemed wealthy. Probably this was largely due to the fact that he left the conduct of his kingdom's finances to those whom, in his merrier moments, he was wont to describe as "the statistical coves" he paid to "add up the takings." When he required money, he commanded some to be given him. When there was none, he carried on "on credit." When he could not get any credit, he went without. It was very simple, but it had its disadvantages, and Eurystheus generally was distinctly hard up. Among other accounts outstanding, he owed King Augeas (one of the most successful and popular cattle-breeders in Greece), a very heavy bill for beef supplied to the army the year before, and as the Queen had reminded him, he had agreed that part payment, owing to great shortage of labor and several agricultural strikes in Elis, should consist of a thorough clean-out of Augeas' sheds and stockyards. Eurystheus so far had neither paid any money off the bill nor had he supplied the promised labor. Hence the Queen's opportunity to stir Hercules up against a distinctly cheerless "task."

But it had occurred to Hercules that he might, without much difficulty, come to a little arrangement with Augeas which should not be altogether unprofitable to himself, and he had said as much to Eurystheus.

"After all, old man, those stables haven't been cleaned out for thirty years, and it should be worth a good deal to Augeas to get them right. Why, half his cattle must be ruined every year with thrush, greasy heels and one thing and another. What? Well, now, suppose I can come to some sort of arrangement to charge Augeas for what I do—he's a bally business man—what? Charge him, say, ten per cent of his oxen, for instance. We could sell these to one of our army contractors, and that would give us a little ready money—enough to pay off some of the Hunt Club expenses, and get a few more good horses. What!"

Eurystheus had looked at him with an admiration that was almost reverent.

"By Zeus, Hercules, what a head for business you've got!" he had exclaimed. "Should never have thought of that myself in a thousand years!"

So they had planned it—and now Hercules was en route to carry out the ingenious little scheme.

STEADILY he kept on his way, ignoring, for once, all the

various opportunities and excuses for lingering which, in those

days, invariably presented themselves to the enterprising

wayfarer.

Even Cerberus, the three-head, was sharply and sternly called to heel from every rabbit-chase he designed, so that by tea-time Hercules crossed the frontier, and an hour or so later was urging the somewhat jaded and leg-weary Pegasus across the park which surrounded the palace of the agriculturally inclined Augeas.

About halfway across the park he pulled up sharply as an elderly gentleman of rather bucolic appearance, carrying a spud, stepped out from under some trees.

"Good evening," said Hercules civilly. "Do you happen to know if the King is in residence?"

"He is," replied the man in a bluff, hearty way. "I'm King Augeas; and if you aren't Hercules, you can call me no judge of a bullock!"

"Good man," said Hercules, and dismounted. "I've come to make some arrangement about these cow-sheds of yours."

Augeas nodded, chewing thoughtfully at a straw. "Ah, yes. King Eurystheus sent you, I suppose."

Hercules paused a moment before answering. Then, significantly, he said:

"Do I look like a man who can be sent anywhere—by anybody? What?"

Augeas cast his eyes over the gigantic stature of his visitor, taking in the size of his club and the appearance of his dog.

"No," he said frankly, "you don't. I suppose you've come of your own accord. But what for? Nobody would take on the work of cleaning out my stables for fun—or friendship. Is it another of your feats? They tell me you're going about doing these feats all over Greece—and if you want to do a feat in my stables, I'm sure I shall be very much obliged to you."

"I am afraid it will cost you a little more than that," said Hercules. "I shall want ten per cent commission. It would be more, but I've made a bet with a friend that I can do it in one day!"

AUGEAS stared.

"Clean out those stables in one day!" he echoed. "I wish you could. Man, it is impossible! I should like to share your friend's bet. Why, those stables haven't been cleaned out for thirty years!"

"If you want to have a bet about it," said Hercules, "I can accommodate you, and I haven't seen even the stables."

A gleam of bucolic cunning crept into the eyes of Augeas.

"You mean to tell me seriously that you will back yourself to clean out those stables in a day?" he said.

"In rather less, I should say; but call it a day—a fair eight-hour day."

King Augeas nodded. He felt that this was altogether too good a proposal to allow it to get past him.

"Well, Hercules," he said, "you know your own strength best, I suppose, but I am willing to lay you ten to one in anything you name that you don't do it!"

Hercules pondered. "How many head of stock, have you?" he asked.

"Oh, perhaps five thousand along now," replied Augeas.

"Very well; I'll take you in steers," said Hercules. "You lay me five hundred fat steers to fifty. Will that do?"

"It's a bet!" said Augeas quickly, and turning to a young man who had strolled up with a bow on his shoulder, a javelin or two in his belt, and a brace of rabbits in his hand, he added:

"You witness that, Phil!"

"Yes, Father," responded the newcomer, who was none other than Prince Phyleus, the son of Augeas whom the Queen of Mycenae had said she believed to be attracted by the Princess Admete.

"Good! It's a bet!"

They shook hands on it, and at Augeas' suggestion they moved along to the palace.

"After dinner, if you like, Hercules, you can have a look round the stables—I'll throw that in," said Augeas, generously.

"Good scheme! I will," replied Hercules.

And so, each very well content, they sent Cerberus and Pegasus round to the back, with strict orders that the horse was to have a well-deserved hot bran-mash, and the barb-tail a sheep or so, and went in.

"We are plain folks here," said Augeas, as he put his spud in a corner of the entrance-hall, "but if good country fare and plenty of it is of any use to you, you have come to the right place. There's some good wine too—but no damned kickshaws!"

"You are a king after my own heart, sir! You and King Eurystheus would get on well together."

"Um—ah—yes! Should get on better if he would pay his bills, though. Always pay cash myself, and expect cash. Only way to get your proper discount!"

"Yes, there is that—never thought of that!" agreed Hercules, wondering what "discount" was; He and Eurystheus never bothered about discount.

KING AUGEAS, it appeared, did not dine until eight o'clock,

devoting the time between five and eight to riding round his

farms, and as, shortly after tea, Prince Phyleus had his horse

brought round, to enable him to keep an "important appointment,"

Hercules found himself free to look at the scene of his next

day's labor. Most of Augeas' family were at the capital.

Reflecting that he might be comfortably in time for the evening

rise, Hercules took his trout-rod and book of flies—without

which he rarely traveled—with him, and fetching Cerberus,

strolled out to the cattle-sheds.

Arriving there, he perceived, without straining his mental faculties in the slightest, that he had considerably underestimated the amount of work which a thorough cleansing of the formidable array of sheds called for. There was an enormous number of them. They were cheaply runup, badly dilapidated erections of dried mud and thatch—huge rows of them, enough to stable twenty thousand oxen. They were built like a narrow street along the bottom of a shallow valley some miles long. The gangway between the sheds was choked with the accumulations of years.

Hercules surveyed it all with a growing feeling of depression.

"Augeas may pose as being a bit of a yokel," he said to himself rather ruefully, "but he seems to have the mind of an urban secondhand clothes merchant. What! That was a neat touch of his to convey the impression that he only had five thousand head of cattle. It may be all he has now, but at least a million cattle have roosted here during the last thirty years!" He turned away.

"I can see where I lose fifty fat steers within the next twenty-four hours," he confided to Cerberus, who was trotting soberly along by his master, with one pair of eyes watching a flock of sheep on the upper slope of the valley, one pair—the hound's—roving about, presumably looking for a fox, and the third pair tightly shut—for the bulldog head was fast asleep.

Hercules walked to the upper end of the valley, putting his rod together as he went. He had learned that the rivers Alpheus and Peneus joined a quarter of a mile past the head of the valley, and he had always heard very good reports of the trouting below the junction. It was a marvelous evening, and though few fish were rising when he arrived, it was quite obviously, in Hercules' opinion, the only way to spend the two or three hours remaining before dinner.

He perceived, some distance upstream, a rather attractive little cottage, and decided to work his way at leisure up to that cottage, and there enjoy a pitcher of the rough but stimulating wine of the country.

Hardly had he decided upon this when— plop—a trout rose like a wolf some thirty yards upstream.

"Ha!" said Hercules, and crouching low, stole up toward the broadening ring left by the fish.

He tried him with a "Charioteer,"—a fly of his own invention,—and the trout rose at it without hesitation. Then ensued ten minutes of pure joy and five of abject misery as Hercules realized that he had foolishly forgotten to bring a landing net.

The fish, a good four-pounder, swam sulkily round in small circles, while Hercules pondered the problem of landing it. Then, just as he was at the point of sending Cerberus in to fetch it, rather than risk trying to lift it across the reeds, a musical voice behind him said:

"I have a net. Shall I land it for you?"

"Oh, I say, thanks—thanks awfully!" said Hercules. "It's fearfully kind of you."

The lady who had spoken—an unusually attractive girl of perhaps nineteen—deftly slid the net into the water. Hercules as deftly steered the fish over the net, which the girl raised skillfully at exactly the right moment; and so the trout came ashore correctly.

Then Hercules turned to thank her. Some five minutes' playful badinage revealed the facts that her name was Phlori, that she was the daughter of Augeas' general manager, that she lived in the cottage upstream, and seeing Hercules' plight with the trout, had hastened to his rescue with her papa's landing net.

She was very pretty, bright and graceful, and Hercules was charmed. With the capture of the big one, the very brief rise finished, and Hercules was at liberty to stroll with Phlori as far as the cottage, there to make the acquaintance of her papa and his wife. They walked along, chatting.

"It seems quite unreal to me that I should be walking along the river with the famous Hercules," said Phlori, with a sidewise glance at him. "I suppose you are the most famous man in Greece!"

"Oh, come, Miss Phlori, you're chaffing me, what?" said Hercules.

"Oh, but you are, you know. Your feats! The way you captured Cerberus—what a funny-looking creature he is!—was simply too priceless!" continued the girl.

"It's awfully kind of you to say so," said Hercules gratefully. "Do you like me, Phlori?"

"I think you are just too sweet—but here's Papa!"

Hercules looked up, to see that they had arrived at the gate. Sitting at a table in the garden was a grizzled, elderly Greek, apparently gazing into the heavens through the bottom of a glass jug.

"Papa," said Phlori, not without a very natural excitement, "here is a visitor—Mr. Hercules! He is wondering if you can spare a cup of wine!"

"Ay, lass, that I can, and nobody in this parish more welcome to it than Mr. Hercules," replied the old Greek, springing up. "Come in, Mr. Hercules. Come right in, sir, and set down. Set down in that chair, Mr. Hercules, sir, and make yourself right to home. Phlori, my dear, tell the maid to bring Mr. Hercules and me up a half-dozen o' that wine I bought at the sale. It's a very fine drop of wine, Mr. Hercules, and I'd be proud to have your opinion 'pon it, sir. Dear me, dear me, I'm right glad to meet you, Mr. Hercules!" And thus prattling, the hospitable old sportsman saw Hercules comfortably seated, and bawled for fresh goblets to be brought.

"I suppose, Mr. Hercules, you will be dining with His Majesty tonight, or, perhaps, mebbe you'd care to stop and peck a bit with us. We just cut a beautiful ham, a beautiful bit o' home-cured ham—a better bit of ham than what you'll be getting up at the palace."

"There's nothing I should like better," said Hercules, watching Phlori as she deftly set out the large two-handled glasses. "But I'm afraid it can't be managed. Augeas rather expects me, I fancy."

THE old Greek looked at him keenly as he filled Hercules the

goblet.

"Well, Mr. Hercules, I'm a blunt man, yes sir, and I hope that you'll look out that they don't steer you into no dice-games up at the palace tonight. Nor no betting, either. For I'm bound to say that His Majesty and Prince Phyleus are very sharp-witted." He raised his goblet. "Well, Mr. Hercules, here's your very good health. Phlori, my dear, get yourself a little goblet and drink Mr. Hercules' good health, there's a good little gal!"

Phlori did so, she and Hercules clinking glasses. As they sat them down, a newcomer appeared—a young, sunburnt, good-looking man, very picturesquely arrayed, and carrying a lariat over his arm.

As he came up toward the table, Cerberus issued forth from behind Hercules' chair with a blood-freezing growl.

"Gee!" went the man with the lariat, staring. "Some pup! Whose is it?"

Laughing, Phlori introduced him to Hercules. His name, it appeared, was Red Bill, and he was the foreman of the cowboys engaged on the Augean ranch. He had come, he explained, to ask Phlori's father about a rumor "the boys back at the bunkhouse" were discussing. Was it right, he demanded, that Mr. Hercules had bet fifty steers that he could clean out the sheds in one day, and was going to try it next morning? Because, if it were true, continued Red Bill emphatically, he was sorry to say that he guessed Mr. Hercules had been rather badly "skinned" by the King, and might certainly regard his fifty steers as being "up the flume for fair."

"Well, so be it!" said Hercules, rather ruefully. "I'm afraid you are right. It was a foolish bet to make—though, as a matter of fact, I had rather got the impression from Augeas that only about five thousand head of cattle had been kept here."

RED BILL and Phlori's papa and Phlori herself exchanged

meaning glances. Then, sadly, the cowboy reached out a horny hand

to Hercules.

"Shake, Here, old man! They've got their fangs into you, too. Well, well,-you're sure in good company. They've skinned me too—skinned everybody! Why, say, Here, there aint nothin' going on two laigs on this ranch that they aint skinned— mebbe so for a half-dollar off their pay, or mebbe for their pile. Some sharps, them two royal gents, Here, believe me! They sure are! Why, say, they aint never had less than thirty thousand head on this ranch as long as I been riding here!"

"It's a shame," said Phlori indignantly.

"Sure, Miss Phlori," agreed Red Bill.

Then up spake the general manager of that ranch—Phlori's papa, who had been sitting in glum and thoughtful silence.

"There's no manner of sense in getting all het up about this, boys," he said calmly. "Mr. Hercules here has been bit by them two rattlesnakes—providing he don't cleanse the stables tomorrow. But if so be he can cleanse 'em, then he wins out. Now, don't get all het up about it, but jest fill up your glass, Mr. Hercules, and you too, Red Bill, and listen to me.

"There's been too much of this sharp work going on. Why, no man's salary is safe till he's spent it, the way the boss and his boy carries on. I've never knowed either of them men lose a bet or a game, Mr. Hercules, sir! And if we can manage to hand 'em a lemon over this here bet, so as you can tear them steers away from the old man, it would hurt him so much that the old galoot would never bet again. It's the winnin' what keeps him hungry for more—and it's the losin' what will cure him. Now, Mr. Hercules, while I been setting down here I been thinking it over, and to my mind there's but the one way that little range o' sheds can be cleansed in one day. The river runs round by the head of the valley, don't it? And about a hundred yards back there's the dam what was put up years ago by Augeas' father, time o' the floods! Now, s'posin' Red Bill and a couple dozen of the boys in from the ranges got to work quietly on the dam wall tonight—there'll be a moon—and work through it jest far enough for it to hold till mornin', plastering up the holes with mud. Then, when Mr. Hercules here comes along tomorrow, to do his contract, he'll only need to put in a few good bats with his club—"

"I got that—I got it! Gee!" said Red Bill, rising excitedly. "Them sheds is going to be sure cleaned tomorrow!" He drained his goblet.

"You jest got to excuse me, Here, right now. I'm hittin' the trail for the bunk-house as fast as I can beat it, to rope in the boys," he said. "This is where we got their skin game beat—yes sir!" And with an elaborate bow to Phlori, he left on his mission forthwith.

"Well, Mr. Hercules, sir, what's your idees about it?" asked the old Greek.

HERCULES leaned across and solemnly shook hands.

"If I had your head on my shoulders, I shouldn't have to work miracles to get the price of a decent hunter," he said simply, but with an admiration in his voice that was as sincere as it was pleasant to hear. "I always was a bit of an ass at ideas—what!—and it's a pleasure to meet a man with his own share of brains and mine too!"

Then, from the direction of the palace, came the boom of the dinner gong, and with a hasty "A revoir," Hercules hastened back to dine with a sharp-set Augeas and his family.

In spite of an extraordinarily poor dinner overnight, Hercules rose and donned his lion-skin next morning in the highest of high spirits. He had something to be cheerful about—for King Augeas, ably assisted by Prince Phyleus, had managed to persuade him to treble the bet, so that Hercules now stood to win no fewer than fifteen hundred steers, or lose a hundred and fifty.

It had been agreed that the "day" should begin at eight sharp, and consequently, shortly before that hour, Augeas, his son and Hercules arrived at the vast collection of sheds in the valley.

Save for a number of the cowboys who were lounging about, chatting with a sort of repressed excitement, and the old general manager, there were no spectators, except Phlori, who was standing at the head of the valley, some distance from the sheds, at a place where she commanded a view of both the sheds and the dam.

The rustic-looking but sharp-souled Augeas seemed to be in a most generous mood, as he no doubt imagined he could well afford to be, and breaking the silence with which Hercules was surveying the work which lay before him, very kindly offered to provide him with any implements or tools he felt he required.

"There are plenty of stable forks and things, Hercules," he said, "and everything you require you are welcome to."

Hercules smiled and patted his club.

"Thanks very much," he said. "It is very kind of you—but I think I will pin my faith to my old friend here—what! The little club!"

They stared.

"Your club! But—how do you think you are going to cleanse those sheds with a club?"

"Why," said Hercules blandly, "I'll show you. It's quite simple, when one has the trick of it! I suppose all the cattle are out?"

Augeas nodded.

"Yes—I gave orders that the cattle and the men should be kept clear of the sheds today. I wanted everything fair and above board."

"Good," said Hercules. "I may as well get the work done. If you will keep your present positions, you will have a ripping view!"

He moved away in the direction of the dam, Cerberus at his heels, as usual.

"He's mad," said Phyleus. "He's going away from the sheds!"

"Mad as a hatter, I should say, my boy. But that's his affair," replied Augeas. "He's probably gone up there to fetch some patent shovel!"

THEY watched until Hercules disappeared round the head of the

valley, then settled themselves down to wait until he

returned.

The little group of cowboys on the opposite side of the valley were very quiet for the next half hour—and then, just as King Augeas and his son were beginning to think that Hercules had quietly bolted, and was now well on his way back to Mycenae, a wild shout from Red Bill, who was prominent among the cowboys, startled them.

"Hyar she comes, boys!" he yelled, pointing up the valley.

Augeas and his son, staring in the direction in which Red Bill was pointing, heard a low and faint but gradually increasing roar, and they saw suddenly sweep into the valley a creeping brown wave which grew in speed, in height and in breadth with extraordinary swiftness. There had been a heavy rain in the night, and the rivers Alpheus and Peneus had swollen greatly.

Then, even as they wondered quite what was happening, a heavy crash sounded from the direction of the dam, and the roar of water redoubled.

The wave, rushing down the valley, suddenly grew into a wall of muddy water—and it was heading straight for the sheds.

King Augeas seized his beard with both hands. "The maniac has broken the dam!" he yelled.

Prince Phyleus grinned wryly. He had realized it a moment sooner than his father.

"We lose, Governor," he hissed. "Not only the steers, but the bally sheds and all!"

He was right.

Ten seconds after he spoke, the wave reached the first shed, foamed round it a little, and passed on. The shed went with it. The water, pouring down the slope, gained speed, and swept mud hovels down and away like straws.

Augeas ground his teeth; and at that moment Hercules, laughing uproariously and streaming with water, reappeared, hastening down to them.

"How's that?" he shouted. "Water! The finest cleanser, next to fire, in the world, what! By the end of the day you wont have a straw left in the valley!"

"No, you blackguard, nor anything else either," screamed Augeas. "Why, you maniac, you've done more damage in half an hour than I shall repair in six months."

Hercules stiffened.

"I will trouble you for less abuse, sir," he said coldly. "Nothing was said about damage. The bet was that I should cleanse the stables in a day. And if they aren't cleansed in half a day, why, you can call me no bally engineer. What!"

"Nothing was said about damage. The bet was

that I should cleanse the stables in a day."

Phyleus was staring across the valley at the crowd of deliriously delighted cow-punchers, with a puzzled frown.

"What, in the name of Zeus, are they so delighted about?" he snarled.

"Why—look at the work I've saved them!" said Hercules. He pointed to the swirling flood. The hovels were collapsing like card houses.

"I think we can safely consider that I—Dr—win, I think," he continued politely.

His face mottled a curious purplish-gray, Augeas whirled on him.

"Win!" he ground out. "D'you call that winning? I wonder you didn't start a volcano or two in the valley just to make sure! You don't imagine that I intend to pay out a single steer on a deal like this, do you. I—I wouldn't do it!"

Hercules' face hardened.

"You wont pay!"

"Not a hoof—not a horn!" said Augeas flatly.

"Very well—I shall take the steers!"

"If you touch a steer on this ranch, I'll put your friend Eurystheus into court within the next twenty-four hours for the meat bill, and if he doesn't pay I'll sell him up, lock, stock and barrel!" said Augeas venomously.

Hercules reflected. He saw that the man meant it, and quite the last thing in the world he wished to happen was to see Eurystheus sold out. He and Eurystheus were very comfortable; the hunting was first rate; the shooting was not bad if a man was pretty nippy with his bow; there was some good jack-fishing, though trout were scarce; the cellar was well-stocked; and it was a thousand times better than the city palace at Tiryns.

Hercules thought of these things, and decided.

"Very well," he said. "We will let it go at that. I won't collect my steers until you collect your bill. But mark me—both of you: if I hear of any trickery, any attempt at breaking this arrangement, I'll come back here and collect those steers with compound interest. Understand?"

They nodded sulkily, and without wasting more time on them, Hercules waved a friendly farewell to Phlori and Red Bill, and started forthwith to take the glad news to Eurystheus. He had lost his steers—but on the whole, as he told Cerberus, he had nothing to grumble about.

BUT in spite of the success which had attended all Hercules'

efforts on behalf of his royal friend, affairs—financial

variety—were not wholly satisfactory in the household. For

the two friends, shortly after Hercules' return from Elis, found

themselves face to face with one of those runs of thoroughly bad

luck which seem invariably to come at the wrong moment. The

outlook was black.

To begin with, Hercules' dog Cerberus, the barb-tail, had not only acquired the distemper for himself, but had communicated it, with all the liberality which usually distinguishes those with contagious misfortunes, to many of the hounds, several of which had already perished. Further, a few days before, the pack had run into—not the fox which Eurystheus and Hercules had fondly believed they were hunting, but a particularly agile and healthy hydra or nine-headed snake, each head possessing two very poisonous fangs. The hounds had torn the beast to pieces, but not before it had utilized its fangs with results truly lamentable. Also old Pegasus, Hercules' weight-carrier, had gone lame on two feet. In addition, Eurystheus had invited the King of Corinthia for a sporting week-end, and the visitor, spending the evenings in a quiet, gentlemanly way with the dice, had won from Eurystheus and Hercules, also in the most quiet and gentlemanly way, practically all the cash they possessed, including the sum which Eurystheus had kept by him for the Queen's birthday present.

The two friends were discussing these and other calamities one evening over their wine.

"No; we can't disguise it, Hercules," said Eurystheus. "Things are just about as bad as they can be—worse, if anything. It is absolutely important that we raise some money somewhere—absolutely. Why, the Keeper of the Privy Purse, damn his impudence, was actually complaining because the servants are grumbling that they haven't been paid for three months!"

Hercules stiffened.

"The insolent hound!" he said. "How in the name of Zeus can you pay them if you haven't got the money?"

"Why, that's exactly what I said, Hercules—practically my very words. But he just shrugged his fat shoulders. It annoyed me abominably. I boiled over completely at the rank injustice of it. 'Look here,' I said, 'you're the keeper of my privy purse! Not me. And I assure you that if you find the position too hard for you, no doubt it can easily be arranged for you to be superseded! What's the matter? Hang it,' I said, 'you can't be overworked at the task of keeping my privy purse. Why, there's hardly ever anything in it!' And that disposed of him, my boy—for a time, at least."

SLOWLY Hercules nodded.

"Can't you do anything with the Chancellor of the Exchequer?" he asked, without much enthusiasm.

King Eurystheus laughed bitterly.

"My dear man, what are you talking about? Everything I say to that miserly thief goes straight to the Queen—and instantly out comes a demand from Tiryns for an explanation. Explanation! That's it! 'Kindly explain why you need this money!'" he quoted sourly from letters of the Queen which evidently rankled still. "If I were to say that I was short of hounds or had lost money entertaining a royal pal, he'd simply say that all spare cash was earmarked for new sling-strings for the army slingers, or needed for this year's feather-crop for the archers' arrows or something of that sort. No, I shall get no more money from the exchequer until the next quarter is due."

"Can't you mortgage this place, then?"

Eurystheus smiled indulgently.

"Dear old priceless old Hercules!" he said. "It was mortgaged up to the ridge-tiles years ago. That chap in rusty black you often see hanging about the grounds is the mortgagee. He's been doing that for years—comes here after his interest. I usually refer him to the Keeper of the Privy Purse!" And so saying, Eurystheus refilled his goblet and roared with laughter.

"I saw some of those acrobats in the street the other day at Tiryns," said Hercules suddenly. "They were doing all sorts of ridiculous little tricks—but by Zeus, they were simply raking in money from the populace! Almost everybody who passed threw them a coin!"

Eurystheus looked interested.

"Really! That's rather interesting!"

Then his face clouded again.

"Well, but we couldn't do that in the streets. After all, I'm the king of the bally country, even if I haven't got any ready money!"

"Quite so," said Hercules. "But couldn't we think out some new scheme to show the populace something unusual? They'd pay to see something novel. The wrestling business is pretty well played out—what! How about some real fighting? A man and a lion! Great Zeus! I've got it—a man and a bull! Myself, say! I'll get that mad bull that King Minos of Crete has offered a reward for, 'dead or alive, but preferably dead.' You remember! Then we'll have a ring built in Tiryns—a fatigue party of troops can do that—and I'll fight the bull in the ring—what! That will bring the coins of the populace simply whizzing out of their pockets—what! Of course, you needn't appear as one of the organizers—only as a patron. Besides, we don't know enough about business to organize such a thing. But I know who does!"

"Who?" asked Eurystheus, eagerly but ungrammatically.

"Why, that fat impostor, the Keeper of your Privy Purse—what?" cried Hercules.

"Magnificent, Hercules! How on earth do you think of these ideas? Nothing could be better! What a pity it is that the Queen didn't take a fancy to you. I'd have had you Chancellor of the Exchequer in twenty-four hours!"

He drained his goblet, and glowing with enthusiasm, shouted for his attendant.

"Ho, there! Send my purse-bearer to me!" he commanded, and forthwith the same was done. A fat individual with a faintly humorous gleam in his eye entered so quickly that he might have been waiting outside.

"Your Majesty desired—" he began, but Eurystheus stopped him.

"It's all right, Stefanopoulos; I waive ceremony pro tem. You have my permission to regard this as friendly little talk just as one man to another. It's business, you understand, Stefan. Get yourself a goblet off the sideboard, lock the door, and sit down."

Stefanopoulos did so, with astonishing alacrity.

"There's no need for a lot of ceremony between three sportsmen," said the King, "and I will say for Steve, here, that he's a grand rider to hounds, though everybody knows what a fat fraud he is really. However—to business. How's the purse, Steve? Honestly, now—no beating about the bush: it's business."

Steve put out his hands in a gesture of despair.

"What! Nothing at all!" exclaimed the King.

"Not an obolus—not even a brass chalcus!" said the Bearer of the Purse. "I turned it inside out not ten minutes ago to show the Tailor of the Privy Robes a worn place that needed patching!"

"Worn place! Ha-ha! That's good! Worn, forsooth!" And King Eurystheus laughed immoderately. "What wore it? Money? D'you hear that, Hercules? The Privy Purse has got—a worn place in it! Ha-ha! Bah! The mice must have been at it! I've never yet had enough money to wear out a papyrus bag, much less a royal purse! And they're going to mend it. What for? Do you think you're going to get something to put in it, Stefan?" he demanded sarcastically.

Hercules smiled. "Of course he is—you've forgotten," he said.

Eurystheus calmed down.

"By Zeus, so I had! Tell him, Hercules. Listen attentively, now, Stefan." And refilling his goblet, he settled back to listen again to the scheme which Hercules proceeded to expound in detail to Stefan.

The harassed Keeper of the Privy Purse leaped at the proposal like Cerberus leaping at a fat sheep, and so the trio went into the figures then and there. And when presently Steve was dismissed, he was a full man—full of figures, wine, joy and hope.

"HOW'S that?" demanded Hercules, triumphantly, as the

Purse-bearer left the room.

"First-rate!" replied Eurystheus.

"Yes, it's topping," agreed Hercules, rising. "And now I must be getting to bed. I'll go to Crete to fetch the bull, via Elis."

"Why?" inquired Eurystheus. "I thought things were a little strained between Augeas and ourselves?"

"So they are. But I sha'n't see Augeas. There's a man there I want to join us—a cowboy called Red Bill. I told you about him, didn't I? He was foreman of the cow-persons on the ranch—a fine fellow. He will be just the man to help us in the bullfighting business."

"Good," said Eurystheus. "Carry on!"

And with that each deviously made his way to bed.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.