RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

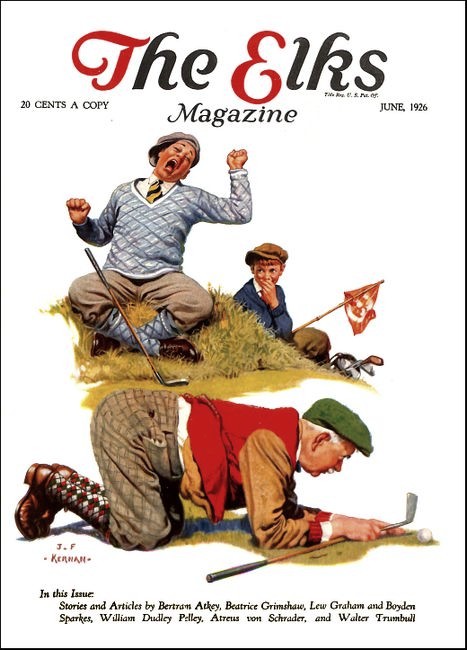

The Elks Magazine, June 1926,

with "The Pale Lady"

C. Leroy Baldridge's illustrations for this story are not in the

public domain and have been omitted from the RGL edition.

SITTING comfortably upon the lumpy area which comprised the upper crust of Stolid Joe's skull, Mr. Prosper Fair gazed thoughtfully over the hedge at a big, reed-fringed lake, which, silver-grey and beautiful, like a great sheet of stretched silk, had attracted his attention from the road along which he and his little band of pilgrims were progressing.

"Methinks, my littles, that in the silent deeps of yonder lake abideth many a mighty jack-fish!" he said lightly, dangling his legs down over Stolid Joe's great left ear.

"And I am quite sure, Patience, that if only you were tall enough to see over the hedge, you would agree with me. For the luce, pike or jack loveth his comforts, and that is assuredly a most comfortable-looking lake. It is early, and I doubt greatly whether the lord and owner of this fair lake is yet abroad. And when the master lieth late abed, my children, who shall dare to say that the game-keeper ariseth early? Not Prosper—by no means Prosper."

Still surveying the tranquil water, he thumped gaily with his fist upon the iron skull of the elephant.

"So if you will excuse him for a little while. Prosper thinks he will take out his rod and spin a spoon across the lake for a few moments. Perhaps he will catch a fat and merry little jack-fish for his dinner tonight...."

He had not the remotest idea as to whom the lake belonged nor, it is sad to relate, did he greatly care. As he slid down from his lofty seat, he saw or feigned to see a look of disapproval in the deep, affectionate eyes of the little donkey, who warmly wrapped up in her fleecy coat, stood in the road beside the elephant, he put his arm round her neck and looked at her.

"Miss Prim!" he said. "Who takes apples out of Prosper's orchard without telling Prosper? Aha! Then why shouldn't Prosper capture Mr. Lie-abed's jack-fish without telling Mr. Lie-abed? We've caught her, there, haven't we, Stolid Joe?"

The elephant gurgled. Patience wiggled her cars, and Prosper laughed. Plutus revolved rapidly on his own three-legged axis, four times in swift succession, barking like something wound up by machinery. It was, of course, merely Plutus's way of remarking that he was so dashed happy and satisfied that he positively did not care if it snowed.

Prosper disappeared into the big caravan. Presently he emerged again with a light spinning-rod, which he quickly put together. To the end of the line he attached a glittering spoon tackle, and then, taking up a neat telescopic gaff, he moved round to Stolid Joe's head.

"Follow me, young fellow!" he said, and they all moved along to a place where the caravan could be drawn off the road.

"I think you had all better wait here for me." he said. "If I took Plutus he would bark when he gets excited, and if Patience came she would only get her legs wet and cold in the mud by the lake. And I can't possibly take Stolid Joe. There really won't be room in the punt. So you can all have a little rest here and if you are good—apples, when I come back! And a Garabaldi biscuit for Plutus!"

(He had many weaknesses, had Plutus, but it was for Garabaldi biscuits that the semi-terrier would have sold his skin.)

Then Prosper disappeared over the low hedge like a man accustomed to hedges, and rapidly made his way across the park towards a boat-house at the end of the lake....

"And it is you, conscienceless stealer of pike that you are, to whom your gamekeepers come suggesting that you should consign the poachers they capture to the salad basket—to the prison dark and drear," he said cheerfully to himself, as he proceeded lakewards. "Never, by these ten finger-bones, as the Great Brazenhead was wont to put it, never will I commit any poacher on my lands to the local dungeon. Do you hear that, bird?"—he appealed to an early robin who hopped close up to have a good look at him. "Never, Robin, my boy! In years to come, when I am older and greedier—perhaps. But never while I am so practiced and, I may say (since nobody can hear), skilful a poacher myself. Mark that, bobby." The "bobby" marked it presumably, for he put an impudent head on one side and surveyed Prosper with what appeared to be enhanced interest.

So—shadowed by the elastically-skipping redbreast—Prosper approached the boat-house.

Yards before he reached it he perceived that he would have to do his poaching from the bank. The boat-house was falling to pieces—it gaped in many places and was crumbling. There were holes in the roof.

"CLEARLY there will be neither boat nor punt worthy of the

name," said Prosper, and peered round the corner-post. An

early-rising adder went squirming away across the rotten little

board platform along the side of the boat-house, and disappeared

into the gaping hole left by a vanished plank; a large water-rat

dived hastily into the shallow water and swam rapidly into the

tangle of reeds choking the mouth of the boat-house; and a wild

duck rose with a frantic quack and raced out across the lake,

passing so close that Prosper's face was fanned by its wings.

There were no boats there, not even a punt. The place was rank with decay, and little more than an inch or so of weed-choked water covered the mud which had silted in.

"Ruined!" said Prosper, thinking of the trim boat-house on the big lake at Derehurst Castle, and headed toward the wreck of a landing-stage he had marked some hundred yards farther along.

He found deeper water here and a big space free of weeds; the cranky piles, he thought, would just bear his weight if he exercised caution and judgment. So he balanced there and cast skilfully out over the dark water, reeling the spoon home to him with the deftness of a past master of the difficult art of spinning.

Almost immediately, a fish struck like a tiger. Prosper tightened and prepared to play him. But after one slight flurry, the fish gave in and permitted himself to be towed in like a log. Prosper backed to the bank and beached him in order to avoid using the gaff upon a fish which, evidently, was not worth killing. He whistled slightly as he saw what he had taken.

It was a perch—a very big perch that, normally, should have weighed something in the neighborhood of five pounds. But in its present condition probably it would not have turned the scale at two and a half, for it was quite obviously starved. It was the ghost of a perch—an extraordinarily dark hued, skinny phantom of a fish, completely lacking the glowing skin, the broad black stripes, the bright blood-red fins and the bold, dashing, swashbuckling air of a healthy perch. This poor beast with its dim, staring eyes, its dark and leaden-hued skin, its dull and dirty fins was a caricature of a perch.

Prosper removed the triangle of hooks at the end of the spoon as gently as possible.

"Well, my dear perch, you are in the nature of an eye-opener to me!" he said. "What is the matter? No food? Where are the worms? A perch of your build can not live by worms alone, no doubt, but you really are uncommonly near the limit, you know.... I can do nothing for you out here. I wish I could, perch. So back you go. Life, once gone, can not be recovered, but with a waist it is otherwise. Adieu, Perch—let us hope for better times!"

He put the fish into the water and gave him a friendly shove off.

"CAST again, Prosper," he said, lightly, and again sent the

spoon out to work. "Food stock depleted," he murmured. "A man who

does not care to see that his fish are fed doesn't deserve to

have fish. Ah, there you are, jack, my boy!" He tightened sharply

to a furious swirl in the waler, and, again, after another

spiritless flurry, towed home another log. At first, he thought

it was an eel as it lay, long and black and lank in the water.

Then as the giant head and glaring eyes grew clearer, he

perceived that it was a mighty pike—a ten-pounder that

possessed the frame of a twenty-pounder—in far worse

condition than the big perch. Prosper saw that not only was this

fish starved but that it had been starved for a long time.

"Why, jack, this is simply tragic! Cruelty to fish! Haven't you any friends? Really, I should have thought you could have kept up a better appearance than this on water-rats and frogs and wild ducklings. Evidently times are desperately hard in this lake. I must see about it. You know, jack, you have the misfortune to possess rather a swine—yes, jack, inelegant though it may sound. I say it very deliberately—I repeat it—a swine for an owner. If a man wants jack in his lake, well and good. Very natural. But, in the name of Izaak Walton, let him have the decency to support them—eh, jack? Let him turn in some small fry every now and then and see that there are the right water weeds for them...."

He pondered a second, easing out the triangle. Then he spoke decisively.

"Look here, jack, old man, I will see about it. And at once. I will interview your landlord and speak clearly. Clearly. That's a promise—in you go!"

The big-headed, fleshless pike slid back into his element and slowly sank, while Mr. Fair hastily took his rod apart and returned to his friends in the road.

"This way, comrades! We are going to pay a call upon Mr. Lie-abed Fish-Starver.... I have seen horrid sights, Patience—not fit for a little donkey to see," he said, and so they started to find a road leading into the park....

They reached it a hundred yards farther along.

There was a lodge by the great gate, but it was untenanted and in grievous repair. And the gates, sorely in need of paint, squealed on rusty hinges as Prosper swung them open, admitting Stolid Joe to the long, weedy road that wound deep into a wilderness of untended trees.

"This place, my children, is falling to ruin," said Prosper sorrowfully. "We must look into the matter."

PROSPER had spoken very truly when he said that this estate

was falling to ruin. Every yard of that moss-grown drive

exhibited its own testimony of neglect—the rank, dying

weeds that bordered it, the dead twigs, fallen boughs and rotting

bark that bestrewed it, the thick carpet of dead, decaying leaves

that the wind had piled along its edges—all these things

bore dumb witness to the length of time which had elapsed since

any gardener's tools had been used there.

And it was oddly silent in the laurel and rhododendron thickets that rioted untended at each side of the road, and walled it in. A brown thrush or two, slinking into the bloom of the undergrowth; once, a weasel running, deadly silent and absorbed, no doubt upon the trail of some unlucky rabbit; and a pair of busy golden-crested wrens, made up the whole of the life he saw in that drive.

"I MISLIKE it, Patience," he said. "It has an air of

desolation—an odor of dissolution. Do roadways die?

Certainly this one is moribund.... And, by the bread I eat, so is

the house!"

They had turned a curve and the high walls of undergrowth had fallen away, revealing the mansion—a big, square-fronted Georgian building, that could never have been very beautiful and was now literally smothered with ivy—rank, dark-green, big-leaved, poisonous-looking stuff. It cowled the house like the hood of a monk.

"Mr. Fish-Starver has a gloomy soul, my littles," said Prosper, staring at the place. "If this house is not haunted then no house ever was haunted. It is not untenanted, for smoke is rising from one—two—chimneys. Still, let the adventure go forward. But the prospect does not charm me.... Do you tarry here, while I advance upon the foe."

He went forward, and the dark, uncurtained, unkempt windows, half masked with ivy, seemed to stare down at him like rows of sombre, sullen eyes.

He shook his head at the place.

"Forbidding—very!" he said, cheerfully, and, ignoring the broken bell, used the heavy knocker. The echoes went rolling hollowly back through the house, and Prosper waited long for an answer. Presently the big door swung back, and an old, old man peered out. He was completely bald, clad in rusty black clothes and wore heavy-rimmed spectacles—most obviously an ancient butler almost at the end of his span. He was very deaf and shaky and Prosper realized that in spite of the great spectacles, his sight was dim. Like the rest of the estate and "the appurtenances thereof" he was falling to ruin.

"Is your master at home?" asked Prosper loudly. "I have news of a serious character for him."

The ancient shook his head slowly, blinking at Prosper. There was something porpoise-like about him. He cupped his ear with a thin and veiny hand, and Prosper repeated his question.

As he did so the butler was joined by a little old woman.

"What is it, Peter?" she said. She was only a shade brisker than the butler—her husband, Prosper guessed without difficulty. The old people looked at each other rather anxiously, and Prosper laughed a little.

"My dear old people, please don't let yourselves be worried. I am quite harmless," he said. "Just let your master know that I wish to speak to him. It will be all right."

"Yes, sir," said the little old woman. "Please to come in."

She stood aside, and the old man, who had been watching her lips, opened the door wider.

"Please come in, sir." he said, mechanically.

Prosper stepped into a bleak and depressing hall. As the two old people moved away a lady appeared through a door at the other end.

She was old and white haired, but she held herself erect, though, as she came nearer. Prosper decided that it was an effort of will which kept her from stooping. There was that about her which brought to Prosper's mind Shelley's lines to the waning moon:

...a dying lady, lean and pale,

Who loiters forth wrapt in a gauzy veil...

FOR she, too, was thin and strangely pallid.

Once, many years before, she must have been very beautiful. Even now she lacked nothing of that air of delicate fineness which, at any age and in any circumstances, rarely, if ever, completely leaves one who is "born." There was a look of race about this fading lady—Prosper had it, too—and blood called to blood. He bowed like a courtier.

She acknowledged it and waited, looking at him with rather absent eyes.

"It has been my misfortune to call at an inopportune moment. Urgent though my affair is, I shall not readily pardon myself," said Prosper deferentially.

The pale lady smiled faintly, and in a high, musical but faded voice, reassured him.

"My name is Prosper Fair and I am a wanderer," he continued. "And as I came through the dawn the beauty of your lake charmed me. Unwilling to pass it with no more than a glance, and, I am ashamed to say, not being sufficiently strong of will to bridle the savage, primeval instinct of the chase, latent in me, as in every man, I committed trespass. I invaded your park, with the desire to feast my eyes upon the beauty of the lake—a wholesome desire, marred only by the intent to capture, if I could, one or more of the finny denizens of its deeps. It was inexcusable. I plead guilty of poaching and throw myself upon your mercy.... But, if you will permit me to continue, I made a discovery. I caught a pike and a perch, and, madam, they were starved. There is a lack of natural food in the lake and the pike and perch—preying fish, both, are starving. They weigh one-half the weight they should. To restore them to the normal, it is necessary to have the lake restocked with little fish, such as roach and rudd and other species which thrive in still waters. Realising that I had come upon a misfortune which doubtless has not yet been discovered by your servants, I ventured to bring you the news forthwith. If I—"

He stopped abruptly, for, gently, whimsically, with a little smile, though he had spoken, he saw that the eyes of the pale lady had filled with tears.

"But I beg you, madam, do not permit my news to distress you—" he began quickly—"a misfortune so easily reparable—" She held up her hand.

"It is not only the ruin which has extended to the lake that breaks my heart," she said, in a most sorrowful voice. "It is because you bring back the past years when there was only prosperity and happiness here. Now I know, none better, that Ruin holds my house, my birds, my woods, my servants, myself—in a grip as hard and ruthless, cold and bitter as black frost.... Oh, I have been drained of all!" she cried. A pale flush stole to her white cheeks. "Do I not see it? The cottage falling to ruin, the flaking paint, the ragged hedges, the rocking trees! The thousand things that decay and die and are not replaced! Is there one stone of this house, one tree of this estate, that I do not know, that I do not love, that fails to speak to me of past happiness? They cry out against me!" She was trembling with a strange excitement. Prosper, amazed and shocked at this quite unexpected outburst, would have spoken to soothe her, but she went on.

"And you? Who are you? You tell me that your name is Prosper Fair, a wanderer, but you look at me with the eyes of a friend, dead, long dead, but dearest of all, except one, to me. As though you were his grandson. Why do you come to torment me with old recollections—?"

Prosper, extraordinarily moved, broke in regardless of courtesy, for he feared that this terrible fit of excitement would be ill for her.

"Madam, it well may be that the Duke of Devizes, my grandfather, was your friend—" he began, but stopped, startled, as after a quick, wild stare at hint she relapsed feebly into the great oak chair against which she had stood. For an instant he thought she had fainted. But even as he went lo her she revived.

"Forgive me," she said. "I am not well. But I implore you to remain. I wish to talk with you. Presently—in a little while—I will return. Please ring for my woman," she said faintly.

Prosper touched a hell on the table and the little old wife of the butler came in quickly, hurrying to her mistress. Together they left the great, chilly hall, and a moment later the old butler came in to attend to Prosper.

The deaf man mumbled something about breakfast being served in the south room soon, but Prosper looked at him with puzzled ryes.

"There is something about this house, my friend, that I do not understand. Something awry—that sets my teeth on edge. Let me attend, first of all, to my comrades, and then I will return and put straight again whatever it is which is awry."

Then he remembered the butler was stone deaf and perceived that he had not heard a word which he had said.

So he spelt it out swiftly upon his fingers in the deaf and dumb alphabet, assured himself that the butler understood, and went out to explain the position to the little company of adventurers awaiting him.

DURING that day Proper talked long, and very earnestly, with

the pale lady.

She was the widow of one Sir Gregory Haggar and the last of that ancient house. In a day long past Sir Gregory had been boon companion to the seventh Duke of Devizes, Prosper's grandfather, whom Prosper, physically, resembled to a remarkable degree. Though they been rivals for the lady, when her choice had favoured Haggar, the friendship had continued, if not to the profit, in those riotous days, of either, certainly to their complete satisfaction.

Lady Haggar's outburst had been impelled, it seemed, by the suddenness and vividness with which Prosper's unexpected arrival, and his startling resemblance to the dead Duke, had brought back those long past but never-to-be-forgotten days to her mind.... All this she explained at breakfast to Prosper, and with such a beginning it was not amazing that the conversation turned, by imperceptible degrees, to matters less remote and more and yet more intimate and confidential.

To record, in detail, that day's talk would not be profitable. Let the story move forward to Prosper's soliloquized recapitulation of it late that night.

He sat alone in the gun-room, before a blazing fire, with Plutus extravagantly at case on the rug, at his feet. Patience, too, who had made a decided hit with Lady Haggar, lay, nodding drowsily at the fire, next to Plutus. Stolid Joe, unfortunately debarred from this domestic tableau by his size, but by no means uncared-for, chewed as it were the cud of solitude, patience and a rousing good dinner in a stable which Prosper had made comfortable for him. Lady Haggar had long gone to bed, whither Prosper had gaily consigned also the old butler and his wife.

HE was thinking—telling his thoughts, as was his way, to

Patience, who was really too lazy-drowsy to pay much attention.

Indeed, every now and then she nearly dropped off to sleep,

recovering herself with a little start. On these occasions she

would glance round, just to make sure that Prosper was there, and

let him see that she was listening... more or less....

"Yes, my dear, there is something wrong in this house, and the finger, the finger of Fate, Patience—points inexorably to Mr. Rafael Glyde," said Prosper quietly. "Let us roll ourselves another cigarette and recapitulate. Then we will consider Mr. Rafael Glyde, his methods, manners and means.... Ten years ago, good Sir Gregory died, and was laid with his forefathers. For three years he rested in peace, and Lady Haggar waited quietly for the time to come when she should join him. Because he loved this house and the lands about it so well, and because she, too, loved them no less than he had, this pale lady tended them and cared for them as though they were eventually to pass to her own son instead of to a person she never knew, never met, a relative so distantly connected with the house of Haggar as to be scarcely a relative at all. I mean the explorer man, believed to be somewhere in the region of the head-waters of the Amazon—a sportsman, I trust, and, let us believe, a gentleman. But he is very far away, Patience. There was then, as there is now, three thousand a year apart from the rent roll, which, I fear, is now painfully small. All was well—or at any rate, my little donkey, all was normal. In due course Lady Haggar would die. That was to be expected, and she was willing.... But who is this that comes upon the scene, Patience? Who is this urbane, smooth-mannered, kindly, widely-traveled, well-read and charitable gentleman? It is Mr. Rafael Glyde. Mark the name, Patience. Mr. Rafael Glyde. He calls upon Lady Haggar to invite her interest in the philanthropic institutions which he maintains because his heart is so full of compassion for the unfortunate. He tells Lady Haggar of his institutions, his words are fair and they glide smoothly from his lips. He opens the book and the pamphlet, Patience, wherein are printed more fair words and pictures of his institutions—he reads them to the pale lady, his plump, fair forefinger glides over the pages, for he is smooth and soft—his name is Glyde and he is completely and perfectly glideful. And so this pale lady, ever kind, ever charitable, helps him. She subscribes heavily. All very good and beautiful, Patience. Mark how smoothly the affair glides along. So begins an acquaintance with Mr. Rafael Glyde, and an interest in Mr. Glyde's philanthropies. Do you like Mr. Glyde, so far, Patience? I don't!"

Prospers face looked oddly hard and set in the firelight. He continued.

"Time passes, and Mr. Glyde comes again and again he glides away. But not empty-handed. And again and again. Until at last poor Lady Haggar wearies a little of the eternal Mr. Glyde and he goes away with nothing. He understands and is as kind and grateful as if he had received a cheque instead of a check. Is that the end of Mr. Glyde? By no means, Patience. But, for the moment, we must turn from him to contemplate a strange phenomenon. For four years Sir Gregory Haggar has lain in peace, in the vaults of his forefathers. For four years, nothing has come to disturb his rest. Silently, tranquilly, that company of dead Haggars, generation after generation, lie in their appointed places, sleeping.... But now, it would appear that the slumbers of Sir Gregory are disturbed and broken. On a certain night, Lady Haggar is awakened by a slight noise in her bedroom. She is aware of a pale glow near the door, turns in that direction, and she sees—what does she see, Patience? An apparition—a vision—the spirit of her husband. They gaze at each other for a terrible moment in silence. She sees him distinctly—he is dressed as she remembers he was accustomed to dress—he is lean and deathly white but otherwise he is the same as he was wont to be. She is not afraid. On the other hand, she is strangely, wonderfully calm. Why should she be afraid? She is old, and soon, she knows, will go—and go gladly—to join this pale spirit of the man she loved and whose memory she still adores. She waits and the spirit speaks. Yes, Patience—speaks. And what does it say—this dread, nocturnal visitant? Something tender? Something kind? A word of regret or perhaps some gentle reminder that they soon would be together again? Something she might expect the spirit of a man to say to the woman he loved in life, and has not forgotten even in death?"

Prosper's voice was hard and keen and cold, like the edge of a blade.

"Not at all, Patience, my dear. The spirit of Sir Gregory Haggar, it would appear, is a businesslike spirit and confines itself strictly to business. It says in a low voice, low but very distinct, Patience—

"Give freely of that which thou hast to the poor!"

"And so disappeared, Patience, and so disappeared. And Lady Haggar found herself alone, sitting up in her bed and looking and listening. Only there was no sound to be heard, nor anything to be seen....

"NOW, Patience, this poor lady is old, very old, and easily

convinced. And she is convinced that she saw the spirit of her

husband that night, and she obeyed his injunction. She gave

freely—she sacrificed everything except only those two poor

old people who attend her. To whom, Patience? Mainly, my little

donkey, it would seem to Mr. Rafael Glyde, who is so experienced

in wise philanthropy—in the well-managed and effective

disposal of charity. Since then this lady has given—given

with both hands. Her houses are falling to pieces about her, her

estate is neglected, and she has diminished her personal comforts

to a minimum. And still she gives. Sometimes, she feels a spasm

of regret when she realizes, what it is costing her, and confides

as much to Mr. Rafael Glyde, even as she did to me. Kind Mr.

Glyde agrees with her, sympathizes, even advises her to moderate

her charity and spend a little upon the estate. But on these

occasions the spirit of Sir Gregory invariably reappears again

and repeats its solemn adjuration. So that there is no end to the

giving!"

Prosper rolled himself another cigarette, pondering,

"To-morrow, Mr. Rafael Glyde is visiting our hostess," he said pensively. "And, do you know, Patience mine, I have an odd fancy that to-morrow night the spirit of Sir Gregory will again appear unto Lady Haggar. An odd fancy, my little one? Why, little one? Something seems to tell me so—some instinct, Patience. We shall see! Yes, indeed, we shall see!"

He rose briskly.

"And now, my littles, good night. Pleasant dreams. If any spirits visit you, call Prosper."

He patted Plutus, fondled Patience, bade them take great care of each other, and went out to bid good-night to Stolid Joe, and seek the comfortable caravan bunk which awaited him.

But his clean-cut, good-looking face was very grim when, presently, he switched off the tiny electric light with which the caravan was furnished.

ON the following afternoon Prosper met Mr. Rafael

Glyde—a sleek, rather pale, clean-shaven, young-old man who

looked thirty but whose eyes suggested forty-five. He was well

and very quietly dressed, wore his hair rather long and gave one

a vague, general impression that he was an actor about to become

a priest, or a priest who has just become an actor. He was very

smooth-mannered, extremely self-possessed, and full of a quiet

but glowing enthusiasm for the charitable institutions in which

he was interested.

He arrived in a two-seater motor, which Prosper instantly recognized as one of the most luxurious and expensive Italian models.

He noticed—for he appeared lo possess a very quick eye—that Prosper recognized the make; and smiled a little when Mr. Fair commented on the magnificent quality of the make of the car.

"Yes," he said, frankly, "do you know, I often feel I ought not to have bought such an expensive make, although, really, I did so deliberately. I have to travel immense distances—one of my little institutions, for instance, is in Cornwall, and another in the North of Scotland—with others in between—so that only a very well-made car could do the continuous work. Journeying from one to the other...."

He carefully lifted out of the car a wonderful bouquet, made up of many flowers, and took it across to the pale lady who was standing in the doorway.

"Dear Lady Haggar," he said, "this is a little gift which the girls in the Blind Home in Connaught have made for you. It will be a great joy to them if you will accept it."

The flowers were artificial, most exquisitely made. Lady Haggar took them with a little exclamation of pleasure.

Prosper perceived that Mr. Rafael Glyde was quite as able as he had expected him—rather more so, indeed. He winked swiftly to Plutus, to that effect. Plutus had not taken very cordially to Mr. Glyde.

"Let him spread his nets, Plutus mine," murmured Mr. Fair, as he followed the pale lady and the philanthropist into the house. "And gaily dig his pitfalls. We, ourselves, have prepared a little pitfall, good Plutus—a small one, but, let us trust, effective. Nevertheless, we will make haste slowly, and pass an hour or so in the study of this glideful but very efficient spellbinder from nowhere."

They went in to prosecute their studies.

Lady Haggar had introduced Prosper as the Duke of Devizes, and it was not long before Prosper perceived that Mr. Glyde was advancing a cautious feeler or so in his direction also. Prosper was glad of this, for it convinced him that Mr. Glyde was accepting him for what he was diligently striving to appear—namely, a wealthy, good-natured, rather eccentric and, under a superficial veneer of worldly wisdom, practically brainless young nobleman, by no means the sort of person to speculate upon the destination of any monies from which he might be skilfully separated.

So that by the time dinner was nearly finished, Mr. Rafael Glyde felt justified in uttering a few smooth, well.turned phrases, designed to convey to Prosper's understanding the need of funds for the building of the new wing at the John o'Groats Cripples' Haven—another of Mr. Glyde's efforts in the cause of charity.

"You mean that you think I ought to subscribe?" asked Prosper.

"My dear Duke—" Rafael waved a while band—"I should hardly say 'ought.' Let us put it that I am very ready to be grateful for any funds that may fall from the rich man's table!"

"I see," said Prosper. "Well, you may put me down for a thousa—no, wait a moment—how many homes have you altogether?"

"Seven, Duke. Presently I will give you copies of the pamphlets and photographs of them."

"Oh, that is all right! What Lady Haggar approves is satisfactory to me. You can put me down for two hundred to each." Mr. Glyde's eyes glittered. He was profuse in his thanks. The pale lady congratulated Prosper. (Plutus, by great favor, lying on the hearth-rug, snorted disgustfully in his dreams.)

Then Mr. Glyde told them stories of the cripples, the orphans, the blind and others to whose welfare he devoted his life. Sad little stories, most of them, though here and there was a pleasant gleam of humor.

"On the whole, they are happy," said Mr. Glyde, softly. "Yes. I think I may say that. There are moments of mute rebellion against their fate—naturally.... Moods, you know. It is very hard for them. But one keeps on.... Does one's best. There is a reward, you know, a great reward. In a sense, one feels that one creates—happiness. I—we—make them happy, if we do no more. Really, we are much more successful—we teach them crafts, all sorts of things. Those flowers, for example.... Yes, undoubtedly, it is work worth doing—worth a certain sacrifice of leisure and inclination.... Your donation will not be money wasted, Duke!"

"No," said Prosper. "Not wasted. I see that—now you have explained...."

The pale lady retired early.

So did Prosper. He and Glyde chatted for an hour or so after dinner but it was Prosper who did the listening.

Before he went lo bed, however, he congratulated Mr. Glyde upon his work.

"You oughtn't to overdo it, Mr. Glyde." he said. "Think a little of yourself, or you will knock yourself up, you know. We haven't many men like you (I'm rather an ass myself), and those we have we must take care of."

Mr. Glyde thought Proper too hard on himself, and said so heartily.

"To every laborer in life's vineyard his appointed task, Duke," he said.

"Yes, I suppose so," replied Prosper, vaguely. "That is the way of it, evidently. Good night, my dear Glyde."

IF the hushed silence which, some three hours later,

enshrouded the interior of Haggar House can be taken as any

indication of the depth of the slumbers of those in that bleak

mansion, then they were sleeping soundly indeed. And if silence

and darkness in the home that he loved in his lifetime are

conditions likely to allure from its rest in order to revisit old

scenes, the spirit of a dead man, then these conditions were at

their most perfect this night.

So, the earlier of the hours of the night had passed, broken only by the sudden strident clamor of the clock over the stables as it beat out its iron chimes. But with the dying out of the solitary stroke at one o'clock the silence of the house was broken, infinitesimally—just as a fugitive air passing across the surface of a becalmed lake might disturb its smoothness for an instant. A door creaked, faintly, almost imperceptibly.

It was the door of the big, bleak bedroom which Lady Haggar had occupied ever since the death of her husband, and it had opened slowly. A form passed soundlessly over the threshold of the unlighted room, and paused, discernible in the grayish glimmer from the windows as a shadow, the very ghost of a shadow, no more.

It hovered there, quite still.

If it were listening, there was little enough to hear. From the bed, invisible save as a pale smear against the blackness, came only the faint sound of light breathing—not quite regular, not very strong, the breathing of one old and feeble.

The shadow moved a little nearer the bed.

There was a slight rustle as of silk, and against the black background of the open door, the shadow suddenly stood out in a pale, silvery glow, very dim, but yet not so dim that it could not be distinguished as a figure in human shape—that of a man, strangely unsubstantial, deathly pale, with an odd and ghostly effect of misty translucency. It stood for an instant, then in a low voice it spoke.

"Give!" it said, and seemed to wait, gazing toward the bed and pointing with a silvery-luminous hand.

There was a rustle from the bed, a faint gasp, and a slight creak as of one sitting up suddenly.

Then the solitary figure spoke again, in a low and mournful voice, extraordinarily earnest and completely vivid without being in the least theatrical.

"Give freely of that which thou hast to the poor!"

The figure stood for a second, pointing, then vanished. Even as it vanished the bedroom door shut with a little crash.

Something or someone in that room gave an odd, hissing sound of surprise, and the handle of the door was rattled violently, savagely.

Another voice spoke—gay, ringing, clear, and incisive as a dagger point—the voice of Prosper Fair—

"Give freely? Right willingly, and full measure! Full measure and overflowing, Mr. Glyde!"

A blaze of white electric light drenched the room, revealing pitilessly the two men—Prosper sitting on the edge of the bed, fully dressed, one hand in his pocket, and Mr. Rafael Glyde, crouching over the handle of the closed door, glaring over his shoulder toward the bed.

"Give freely!" Prosper laughed a little. "There is something oddly—even objectionably—rat-like in your present pose, good ghost," he said, but without any mirth in his voice or his eyes.

"Yes—repulsively rat-like!... You are trapped, my man! The door is held on the outside—you waste your energy in trying to open it. To fumble any more with the handle is—merely ludicrous!"

Mr. Glyde withdrew his hand from the handle as if it were white hot. He turned to Prosper, hung undecided a second, then poised swiftly, as though to rush him.

Prosper was up, light and quick as a cat.

"Ha! You'll take it fighting!" he said with a sharp delight. "Come, then!"

But Mr. Glyde thought not. He changed his mind, and relaxed his body.

Prosper sat down again.

"The game—" said Mr. Glyde, with the air of one who quotes, "is up! What do you propose to do?"

"There are no charitable institutions, of course? You are just an ordinary beast of prey, I take it?" asked Prosper.

Glyde grinned—a wry, savage grin.

"First, then, I purpose dealing with the loot of the past few years." said Prosper. "How much have you had from Lady Haggar?"

MR. GLYDE hesitated a moment, looking narrowly at Prosper.

Presently he named a sum.

"Roughly, six thousand pounds," he said, slowly, his eyes fixed very intently upon Mr. Fair, who smiled.

"No, no, Glyde," he said, in an oddly quiet voice, "I'm serious. The truth, please. You misunderstand. Be yourself, my good vampire—you are too clever to wish to waste your chance—a bare chance of keeping out of Dartmoor. Don't trifle with it."

Mr. Glyde's eyes narrowed to two black slits in his artificially whitened face. Then he gulped suddenly.

"Very well," he said, unsteadily. "It's about eighteen thousand all told. Five of it is spent."

"Leaving thirteen unspent?"

Glyde nodded.

"An unlucky number!" said Prosper. "Where is it? Current, on deposit or invested?"

"Invested!"

"Think, Glyde. Criminals are cautious investors."

"Well—there are five thousand current, five thousand deposited and three thousand invested!" muttered Glyde.

"I see. That must come back to Lady Haggar at once—you understand."

Glyde nodded and Prosper rose.

"And now we will go down to the gun-room," said Prosper. "Go first." He tapped sharply with his knuckles against the bed-post and the door opened silently. The corridor outside was lighted now, and a thin man of soldierly appearance, standing on the threshold, looked inquiringly at Prosper.

"All in perfect order, Dale." said Prosper. "We are going down to the gun-room."

The soldierly man nodded—he was Captain Dale, Prosper's agent at Derehurst.

"Good," he said and led the way....

Beside the gun-room fire stood Prosper's head chauffeur who had brought Dale down, a dark visaged and leathery man, an ex-boxer, staring solemnly at Patience, whom he had awakened, and who seemed a little put out about something.

"Have you enough petrol to get to London, Barker?" asked Prosper.

"Yes, Your Grace." Mr. Barker was all attention, saluted deftly, and turned to go out to his car.

"And—Barker!"

"Your Grace?"

"Captain Dale will be taking this man to town when you leave here. If he is troublesome. Barker, and if necessary, assist Captain Dale to attend to him without compunction. Without compunction, you understand me, Barker. He is quite hopelessly poisonous!"

Mr. Barker ran a pair of electric blue eyes calculatingly over Glyde, smiled slightly, and saluted again.

"Very good, Y'r Grace!" he said, without emotion but with absolute decision in his voice, and went.

"It is rather rough on you, my dear Dale," said Prosper. "This nocturnal voyage...."

"Not at all," said the Captain, "a day's ratting now and again makes a pleasant change!"

Prosper turned to the silent Glyde.

"YOU disgorge to the last plum, you understand. Pay it to

Captain Dale. And do not allow yourself to fall into the absurd

error of thinking that you are allowed to go free for any reason

but that a public trial would be so painful to Lady Haggar. Those

who are interested in the operations of such artists as yourself

will be informed and, on the whole, Glyde, I think you will do

wisely to leave the country—while yet you may,

Glyde—while yet you may!"

The leathery Mr. Barker reappeared.

"The car is ready, Y'r Grace!'

"Thank you, good Barker."

Prosper shook hands with the silent, capable.looking Dale, and saw them off.

Then he returned to the gun-room, and sat dawn to a thoughtful cigarette.

"A greedy and heartless reptile goes there, Patience," he said reflectively. "Much too clever to murder, but not in the least loath to kill. A vulture—he would have picked this place to a skeleton—and then have put the skeleton up to auction. A leech, a body-snatcher, a—very unpleasant person, indeed, Patience.... I know you are a little annoyed with me because I have been too busy to see much of you to-day. But it was not easy to persuade Lady Haggar to give up her bedroom for to-night—it took me quite a long time. She would not credit my suspicions of the glideful one. Then I had to fix up the electric light, telegraph to Captain Dale, arrange with him about closing the door at the right time, and—lots of things. So be a kind little Patience and make friends—and not be a jealous or cross little Patience with Prosper any more."

He leaned over and patted her neck. She rubbed her head against his leg.

"Friends again?" he said. "That's all right, then."

The door opened and Lady Haggar, fully dressed, came in. She was paler than ever and trembling a little.

Prosper arranged a chair and cushions for her close to the fire.

"You were right?" she asked, quietly. "And Mr. Glyde was—dishonest?"

Her lips quivered.

Prosper slipped his arm affectionately, protectively round her thin shoulders.

"Yes," he said very gently. "Glyde was a swindler. You must try to forget him. As long as money can buy things there will always be wolf-men.... You must forget him and all his works. He is gone and you will never be troubled by him again.... There were no charitable homes except in his imagination. The pamphlets... any printer could supply. We have compelled him to disgorge most of the money—thirteen thousand pounds. Dale will bring it to-morrow, and you will be able to renew the estate, your own comforts—everything. Dale will stay a little while to help you, if you like. He has a genius for management."

She looked up at Prosper with tired eyes.

"And the—the apparition?"

"It was Glyde himself. He had treated a suit of clothes, such as Sir Gregory used to wear, with a luminous preparation. Outside he wore a black silk cloak, so arranged with cords that he could slip it on or off as be wished to get the disappearing effect. And now, really, we must forget it all."

She sat silent for a little but Prosper felt her hand, thin and frail and tiny, close upon his tightly. Her eyes were full of tears.

"Thank you—thank you, Prosper," she said softly, adding, almost in a whisper, "Ah! if only I had had a son like you!"

"You have," said Prosper gaily. "Every sonless woman is my mother."

She smiled a little through her tears.

"But—some day—-you will have a wife—"

"Well—she shall be their daughter," laughed Prosper. "So that, really, you will be my mother-in-law... And now I am going to make some chocolate for you before you go back to bed."

And that is what he did.

TWO days later Lady Haggar and Captain Dale stood at the door

watching a procession go down the drive.

First walked Plutus, alert and, as usual, on wires.

Then came Patience, sober, sedate, stepping daintily.

Then Stolid Joe, gray and mighty, swung past, his little eyes twinkling, the caravan wheeling silently along behind him. Upon his brow sat Prosper.

They were going forth to renew what Prosper called their "study of humanity."

"You won't forget the pike and the perch in the lake? I gave them my word of honor!" he called. The pale lady nodded, smiling.

Then the procession rounded a corner of the drive and with a wave of the hand Prosper was gone.

"He is wonderful," said Dale, suddenly enthusiastic. "Wonderful. At thirty he has the intuition of a woman, the courage of a veteran, the wisdom of a philosopher, the experience of an old, old man—"

"And," said Lady Haggar gently, "the heart of a child."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.