RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

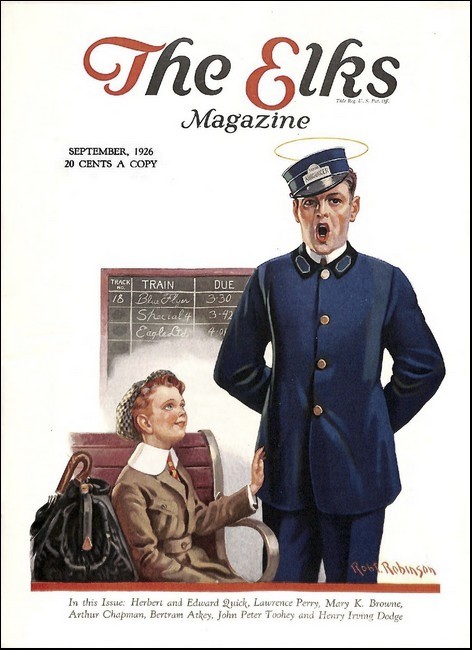

The Elks Magazine, September 1926,

with "The Hardaway-Lucas Case"

C. Leroy Baldridge's illustrations for this story are not in the

public domain and have been omitted from the RGL edition.

"FOR what I think I may fairly describe as the very first time during this trip, mes enfants, we are definitely and indisputably benighted en route," said Prosper to his "children."

"Definitely benighted," he repeated, and switched on the big headlights of the caravan. The powerful rays cut through the hanging veils of the night like white hot bars, lighting up the road ahead perfectly, but only serving to accentuate the darkness on each side.

"But it's nobody's fault. Accidents will happen and who could have foreseen that Plutus was going to fall into the well? Nobody. It will always be an entirely inexplicable mystery to me that he did not beat his brains out against the side of the well as he descended, for it was the crookedest well I have ever seen—even in my dreams where all wells are 'crookit.' However, as our young companion has escaped with nothing worse than a swollen lump upon his head (which, I observe, does not appear seriously to handicap his activities) we may forget the time and trouble it took to fish him out, and merely remarking—perhaps cold-bloodedly—that 'all's well that ends swell,' we will proceed to find a night's lodging without further delay! How say you, my merry men all? Good! Forward, Joseph—through the darkness!"

And, lighting a cigarette and remounting the elephant, Prosper proceeded to get his expedition into motion again.

He had wasted—as may have been gathered—some two hours in rescuing Plutus from a well in an untenanted cottage garden that afternoon. Plutus had fallen a victim to the science of a wise and ancient gray rat inhabiting that garden who, pursued by the ever energetic semi-terrier, had sought refuge under a dead cabbage leaf which the wind had blown to the exact center of the completely rotten boarding covering the mouth of the well. Plutus had aimed carefully at the cabbage leaf and with a mighty stiff-legged bound had reached it. The rotten wood had crumbled beneath him, and his white hairs had gone down in sorrow to the bottom of the well—while the rat, chuckling no doubt, had proceeded homewards to what he probably considered a well-earned rest.

The rescue had been a matter of some difficulty for several reasons which need not he detailed, but Prosper had achieved it. The result of the delay was that night had caught them on the road instead of cosily encamped—no suitable site having yet appeared unto them.

They did not greatly care. It was a miscalculation which happened so infrequently that there was, indeed, a sensation of novelty about it. Besides, they all knew that Prosper was as capable in the dark as in the daylight.

But perhaps ten minutes or so after Mr. Fair had switched on his electric lights, a fat blob of rain came swinging out of the dark and spread itself wetly about Prosper's face.

"Ha!" said Prosper. "There is moisture abroad—or, at any rate, the menace thereof! Forward, Joseph mine! Through the darkness, as before, but I venture to suggest with an increase of speed."

THE rain blobs came thicker, faster, and blobbier

than ever. They splattered on Stolid Joe's broad and

leathery back quite noisily, much to the elephant's

apparent enjoyment. But Prosper kept him at it. His

hide may have been constructed of fabric resembling

triply-water-proofed, and quadruply-mackintoshcd horn

or guttapercha, but he was the only one of the party

who wore that particular quality of hide, and—as

Prosper pointed out—what was merely like

refreshment to him was apt to be extreme discomfort

for one, or possibly two of the others—to

wit, Patience and her owner. Plutus, of course, was

amphibious.

There bore down upon them from behind a thing that hooted long and stridently through the darkness, and Prosper gingerly steered the elephant well in to the left side of the road. A light motor car went whirling by, and Prosper noted that the face of the driver seemed very pale in the glare of the caravan lights, as the man turned to stare for an instant at the gigantic bulk of Stolid Joe. The next instant the motor seemed to leap high in the air, coming down with a rattling crash that must have put its teeth permanently on edge—the teeth of its gear-wheels. Something cracked noisily, the car skidded across the road and, oddly, clean back again, gave a curious, seasick sort of swirl, and came to an abrupt standstill, having turned completely round, so that its nose now faced Stolid Joe instead of its back. Skidding cars do this sort of thing on moderately rare occasions, especially when the driver, traveling a little too fast, turns his head to study elephants at night and quite unwittingly drives over a milestone—even as this one had done.

"Dear me," said Prosper mildly. "How very complicated. The gentleman must be an extraordinarily skillful and ingenious driver! I should never dare to attempt such an intricate reel or figure as that—unless, of course, I had previously fitted my car with roller skates! No, indeed!"

Stolid Joe approached the car till his trunk, thrust out inquiringly, almost touched the radiator, and then stopped abruptly.

The white-faced man in the car must have imagined that he was at least the plaything of evil spirits, for in his gaze as he stared at the mighty blackly-shadowed bulk of the elephant looming over his little car was a species of dazed terror and awe.

Prosper observed it and, gazing down at the completely bemazzled and bothered motorist from his perch upon the elephant's neck, reassured him.

"Compose yourself, my dear sir," he said, not loudly, but clearly and distinctly. "It is merely a slight, unrehearsed effect. Life is full of them. Your car hit a milestone and it put her rather out of her stride. It has bent the car a little—in places—but parts of it are still excellent, I feel sure.... It is an elephant which is gazing at you—not a dragon. He is quite tame and of a mild and friendly disposition. Do you sit quietly there and recover yourself, my good friend, while I dismount and examine the car."

He slid down and went to the man in the car, who appeared to recover his power of speech as Prosper approached him.

"Might of broke my neck, easy!" he said over and over again, rather shakily. "Might easily of broke my neck! Wish it had! Lord, I wish it had! Wouldn't of cared if it had broke my neck!"

Prosper stooped over something which lay in the road.

"Really, you know, that is rather morbid," he said soothingly. "Try to take a cheerier view. Try to forget it. Concentrate all your will-power upon forgetting it. Think of something else—why, my dear sir, the very thing—this milestone! Throw off your gloom and come and help me lift this milestone and throw it into the ditch.... Ha! 'London seventy-nine-miles'!" he quoted, from the milestone, and laughed. "You have traveled over seventy-nine miles in half a second, my friend! Not bad going, that, I think you will agree. Probably a record, I venture to suggest."

And with such light and airy badinage Prosper aided the man to recover his nerve to the extent of leaving his car and helping him heave the milestone off the road, whither the impact of the car had knocked it.

"I think we may congratulate ourselves upon the stone being so loosely rooted in the ground, don't you?" said Prosper. "Even as it was, your car leaped it like a stag!"

The man stared at him dully.

"I wouldn't of cared if it had broke my neck," he said again. "I been done."

"Been done?" repeated Prosper, puzzled for a moment.

"'ad," continued the man, blinking owlishly in the glare of the caravan lights.

"'ad—?"

"'ad—properly 'ad. 'ad on, mind you—'ad properly on a bit o' string. If I'd of 'ad my heart cut out it wouldn't of made more difference to me," said the man, and turned to look at his car.

"'ad uphill and down dale that's what I been," he muttered, "'ad my heart cut out and very near broke my neck and done for my car! And there's folk what call me 'Lucky' Lucas! Lord!"

Prosper let him ran on for a little, while he personally assured himself that the car was not irretrievably ruined. Ten minutes quick examination revealed the pleasing fact that beyond a torn-off wheel-cap, a tire stripped completely from the off, front wheel, and a slight loosening of some of the spokes of the same wheel, nothing was seriously wrong with the car.

"WHY, my dear sir, there is nothing

wrong—using the term in its most generous sense.

If you have a spare tire, produce it, and we will

fall to with a will and repair and build up again the

wreckage. Build up and restore. Even as the humble

ants diligently fall to without comment, upon the task

of building up their hills when they are devastated by

the hoof of the galloping hunter!"

The person who claimed to be known as "Lucky" Lucas, stared at Mr. Fair, opened his mouth, then closed it abruptly, and began to grope in the tool box for the jack while Prosper began to unstrap the spare wheel from its place.

It was not long before the car of Mr. Lucas was made ready for the road again. Prosper worked well and wisely, and Mr. Lucas realized it.

"You've done that in a quarter of the time it would of took me," he said. "And I'm very much obliged to you. I hope," he continued, "that you won't put me down as a fool, but I've 'ad trouble. In fact. I been done—been 'ad. That's why I been sort of flustered, what with the milestone coming on top of it. But I'm much obliged to you, anyhow!"

He made as though to step into his car, but hesitated. He drew a big card from his pocket and offered it to Prosper, who read it, and discovered that the gentleman was Mr. Landseer Lucas, Dealer in Antiques, of Bournemouth and Southampton. Also he was a buyer of old gold, old silver, old brass, old teeth, old false hair, and similar old bric-à-brac. He observed that Mr. Fair would always be welcome at either of his little places. He expressed a rather vague hope that Prosper would let him know if he ever wished to sell Stolid Joe or buy a nice little bit of genuine Chippendale.

Prosper readily promised to do so, and Mr. Lucas finally tore himself away.

"A queer person, my littles," said Prosper as the red tail-light died out down the road. "And one possessing a remarkable degree of vitality, I should say, if we are to believe that he really has had his heart cut out. Personally I take the view that the gentleman was exaggerating his anatomical shortage. But, after all, who knows? Let us abandon these profitless speculations and go forward, comrades! En avant, Joseph! Stop at the first barn you come to; Patience, my pretty one, come walk with Prosper." And once again they faced the rain-blobbed darkness.

BUT in less than a quarter of an hour the rain

had increased to such an extent that it rendered

the immediate discovery of a shelter, or, at least,

a well-sheltered site, imperative. So that when,

rounding a slight bend in that lonely road. Prosper

and his friends saw not far ahead of them the glow of

light from several windows and, as they came nearer,

the looming hulk of a barn behind the house of lighted

windows, their spirits rose, and Mr. Fair girded up

his loins with a will, preparatory to achieving the

permission of the proprietor to bed down Joseph and

Patience in the said barn.

It was a good-sized house, rather too big, Prosper thought, to be considered a farmhouse, yet not quite big enough to be classed as a mansion.

He brought the elephant to a standstill outside the gates of the drive and bidding them tarry there and put their trust in Providence, he proceeded to the house.

Groping among wet ivy he discovered a bell which he rang diplomatically—not too loud and long, nor too imperatively, but firmly and with dignity.

The door was opened by a neat, pleasant-looking maid, revealing beyond the curtained archway a comfortable, oak-panelled hall, well lighted and warmed.

"Is Mr. (cough) at home this evening?" inquired Prosper.

"Mr. Hardaway? Yes, sir. Will you please come in?" said the maid.

Prosper smiled.

"Thank you," he said, and entered. "Perhaps you will tell him that Mr. Prosper Fair would feel very greatly indebted to him if he will spare him a few moments."

"Yes, sir."

The maid vanished beyond the curtain, and Prosper heard her voice in the hall beyond.

"Who? Prosper Fair? Never heard of the man. What's he want? Go and ask him what he wants?" said a voice, rather harsh, and faintly metallic, from the other side of the curtain.

Prosper nodded, smiling.

The maid reappeared.

"Mr. Hardaway wishes me to ask you what is it you wish to see him about, sir," she reported, rather shyly. Prosper sympathized with her, as he did with most (though not all) servants charged with discourteous messages.

"WHY, with pleasure." he said. "I have called to

ask Mr. Hardaway if he will extend to a caravaning

tourist, on this most inclement night, the hospitality

of his barn."

"Yes, sir." The maid retired again. She seemed a little confused.

"Well?" snapped the metallic voice.

"The gentleman wishes to know if you would extend a caravan in a tourist on this inclement hospital and a barn, sir?" faltered the maid, evidently a little out of touch with the situation. Prosper understood that she was nervous and afraid of her employer.

"Eh? What are you talking about?" snapped the metallic voice.

"Gentleman wishes you to extend the caravan and the tourist in the inclement hospital and the barn, sir," said the maid, still more confusedly, but sticking to her guns.

"Girl, you're a stupid fool—" snarled Mr. Hardaway, and to Prospers immense delight the pretty little worm turned.

"And you're a beast and bad-mannered, bad-tempered common bully!" replied the girl, swiftly. "I've never liked you nor your house and I won't put up with your vile temper and bullying ways any longer. I shall leave to-morrow. So—there!"

There was an excited sob from the girl, a muffled oath from the invisible Hardaway, and Prosper, his blue eyes sparkling, stepped into the hall.

"Right well and gallantly said, pretty one," he observed gaily. "But I think it is only a little misunderstanding?"

Mr. Hardaway, a biggish, dark-visaged, thick-jawed gentleman, of perhaps forty, with a morose mouth and scowling brow, clad in riding clothes, rose from a deep easy-chair by a big fire, and put his cigar on an ash tray.

"LET me explain," said Prosper. "I am engaged in

touring the countryside with a caravan. The night

is dark and the elements are unfavorable. I called

to ask your good leave to stable my animals in your

barn this night. The maid misunderstood. It was

my fault. I should have explained more clearly.

Let me say frankly that I am grieved and sorry, it

was—again—my fault entirely."

But the pretty maid would not have it. Evidently there were old grudges to pay.

"No, sir. It wasn't your fault. It was his bullying, glaring, snappy, overbearing way! You are a gentleman, anyone can see that—but he isn't and never will be. Everybody hates him and everybody despises him."

And so saying she disappeared.

Mr. Hardaway looked Prosper up and down. Then he jerked his head to the door.

"Get out of it, you damned tramp! What d'ye mean by it? Clear out!" said Mr. Hardaway, as offensively as he could.

Prosper laughed—a whole-hearted, healthy laugh of sheer enjoyment.

"You ass," he said, friendlily. "You overdo things, altogether. It isn't necessary.... Look here, my dear chap, lend me your barn, and be reasonable. Make it up with that pretty little parlor maid. What will your wife say at losing her? The servant question is—"

"At losing whom?" interrupted an icy, glass-edged voice from Prospers side. He turned and bowed deeply to the lady who had entered, a thinnish lady, rather passée but still good-looking in a somewhat acrid, slightly bitter way. Evidently Mrs. Hardaway.

"At losing your really very capable little parlor-maid, madam," said Prosper. "There has been a rather complex misunderstanding all round. The parlormaid, not quite catching my meaning when I, a belated tourist, begged permission to take shelter for the night in Mr. Hardaway's barn, misunderstood his reproof and became a little confused and hysterical. She has decided to leave, I think—"

The thin lady fastened a glare upon Hardaway, so sourly venomous and bitterly disdainful, that Prosper almost felt sorry for the man.

"Ah," she said, calmly, "your disgusting temper again. When will you acquire sufficient intelligence to learn to address the servants properly?" She favored Prosper with a sour-sweet smile.

"Forgive him," she said, stabbingly, "he is so completely without self-control as to be practically half-witted. It is very pitiful."

"Look here, don't make me out such a fool, d'ye see? I won't stand it—" choked Mr. Hardaway, black-faced with rage. But the slender lady turned on him like a razor:

"Hold your idiotic tongue, you great lout!" she snapped, viciously.

"I shall do as I like," growled Hardaway.

"I will have you thrown out of the house if you cannot behave yourself," replied the loving wife. "Ah! I thought that would silence you. Understand clearly we want none of your pot-house manners here!" She turned to Prosper.

"There is no reason at all why you should not use my barn." she said. "Please take care to set nothing on fire."

Prosper bowed.

"I am immensely indebted," he said. "Thank you a thousand times."

And withdrew—vaguely conscious as he went, that the acid and, evidently, utterly fearless lady, was turning hungrily upon her silenced husband, presumably to tell him what she really thought of him.

"A charming pair," mused Prosper. "On the whole I should be inclined—were I a betting man—to lay long odds on the lady!"

He carefully steered his expedition down the farm road to the barn, halted them outside for a moment and went forward to explore. The doors of the barn were open and as he stepped in, he was aware of lights in the big building and of a familiar voice which, in a tone of soliloquy, was muttering:

"Might of broke my neck! Wouldn't of cared if it 'ad. After cutting a man's heart out pretty near—"

"WHY, it is Mr. Lucas! My dear sir, again we meet!"

said Prosper, and stepped forward to greet the dealer

in antiques, who appeared to be looking over his

car.

Mr. Lucas seemed surprised but pleased to see Prosper. They had quite a little chat together. Mr. Lucas, it appeared, was dining with the Hardaways that night—over a matter of business. Prosper, introducing himself as "Fair, the Arbitrator." taking a rest from business, explained the circumstances of his arrival there.

Mr. Lucas pricked up his cars as Prosper mentioned his "profession."

"Arbitrator, eh? Shouldn't have thought it—though, come to think of it, I dunno why—"

Here he was interrupted by a maid who announced that dinner would be served almost immediately, and Prosper was left to his own devices—greatly to his satisfaction. He fell blithely to work, preparing the evening meal, chatting to his companions, as was his wont.

"If I, my littles, were a painter man, do you know what I would do?" he said, absently. "I would paint the proprietress of this good barn and her husband, discussing the servant question. And I should call it 'Snapdragons at Home.' ... Patience, my dear, if I were to address you, Joseph and Plutus in the way our hostess addresses our host, your hair would turn white in a single night. Joseph's tusk would fall from its socket, and Plutus would bite himself badly. Yes, indeed. But do not look so anxious, Patience mine—that will never happen—never! You shall have sugar-coconut to prove it—so shall little Joe—and Plutus shall have bestowed upon him the two chop bones that I have kept for a rainy night...."

The time passed very pleasantly—Plutus making an occasional round of the more obscure parts of the barn to warn the denizens of the holes in those places to stay carefully at home. They chatted over their tour, and unanimously agreed (according to Prosper) that it was all very jolly, and further passed a resolution that they would often go touring this way. In short they were getting on beautifully, us usual, when, suddenly Mr. Lucky Lucas arrived in a somewhat heated condition, excitedly demanding that Prosper should 'be a gentleman and a friend,' To accomplish this, it appeared, all that was necessary was that Prosper should accompany Mr. Lucas back to the house and—being an arbitrator—settle a knotty point for them.

"After all, there's something in folks calling me 'Lucky' Lucas, ain't there? We want an arbitrator—a good 'un—and here's you, the very man, out in the barn. That's what I call a hit of luck," burbled Mr. Lucas, "luck for us—we get the thing settled—and luck for you, you getting your fees."

Prosper did not dispute it, and so they went off to the house together, leaving the others to continue the chat interrupted by the dealer in antiques.

"IT ain't what you might call a large matter, but

it's an awkward one," said Mr. Lucas, as he piloted

Prosper into a well-furnished sitting-room, wherein

the Hardaways were awaiting him.

"Ha! Bring on your arbitrator—and much good may he do you," said Hardaway with heavy and unpleasant sarcasm as they entered.

The lady was at him like a whip snake.

"Will you hold your tongue, idiot?" she lashed across at the man. "Keep your disgusting wit for your rag-tag guttersnipe friends who appreciate it. We despise it."

Hardaway grunted heavily and was silent.

Prosper, in response to a lemon saccharine smile and a gesture from madam, took his seat at the head of the big dining table, which had been cleared of everything but Mr. Hardaway's enormous Sheffield-plate beer tankard, and an inkstand, paper and pens presumably for Prosper.

"You arc an arbitrator by profession. I understand, Mr. Fair?" inquired the lady.

"And, I may add, by inclination." replied Prosper, ingeniously evading the direct affirmative.

"And you are prepared to settle a dispute between myself and my husband and Mr. Lucas?"

"Undoubtedly."

"The matter must be regarded as wholly confidential," continued the lady.

"An arbitrator is accustomed to keep confidences absolutely. Naturally I shall do so."

"And your fee?"

"My fee, usually, depends upon the amount involved—if an amount is in question. But, in this case, unless the matter is involved, let us lay one guinea."

"Easy earned!" muttered Hardaway.

"Be silent, you great, hulking stable boy!" hissed his wife, with a dagger-like side glance. "The fee will be satisfactory. Do you agree. Mr. Lucas?"

Mr. Lucas, who seemed half afraid of her (not unreasonably) agreed.

"Very well. Then I will state my case. And kindly do not interrupt until I have finished." she said.

"Proceed, madam," said Prosper, and composed himself to listen. So did Mr. Lucas.

"The facts are as foll—" Here Mr. Hardaway gulped noisily at his tankard, and his wife whirled at him:

"If you cannot swill your horrible brewage without making those unpleasant noises you had better go out to the stable and finish it there," she recommended.

Mr. Hardaway stared steadily at the wall, and after a moment, the sweet lady turned to Prosper.

"I WILL put the case quite fairly," she began

again with a steely glance at Mr. Lucas, who looked

both doubtful and uneasy. "Some time ago Mr. Lucas

fell in love with my step-daughter—who is now

at school completing her education. Very properly

Mr. Lucas approached myself and my husband, who is

co-trustee with me of the estate of my first husband,

the late Mr. St. John Singleton, the girl's father.

We approved of Mr. Lucas's proposal but stipulated

that Sybil should complete her education before she

was—er—formally informed of our plans for

her. To this Mr. Lucas agreed and then expressed his

desire to show his gratitude to us in some tangible

form. Curiously enough, there happened at that time

to be some little delay in the arrival of certain

dividends due to me, and naturally you will understand

that Mr. Lucas's offer was very opportune. I must

explain that under the terms of my late husband's

will the income of the residuary trust fund, and also

several valuable articles of jewelry, become the

absolute properly of Sybil when she reaches the age

of twenty-one. That was in the event of my marrying

again—as I have done—pitiful fool that I

have been!"

She favored Mr. Hardaway with a glance like a poisoned assegai, and continued—"The form in which we decided to avail ourselves of Mr. Lucas's offer was to accept from him a loan of five hundred pounds, paying no interest, but depositing a diamond necklace with him as security, this necklace to be returned on the day that Sybil marries Mr. Lucas, which we had expected to arrange to be the day she becomes twenty-one, On that day Mr. Lucas had agreed also to give us a receipt for the money. This was satisfactory to everyone—but suddenly a hitch has occurred. Mr. Lucas pretends to have made two discoveries—one being that Sybil is secretly engaged to a gentleman of whom we know nothing, and the other being that the diamonds in the necklace are paste."

"Not paste—glass!" said Mr. Lucas.

She struck like a viper—

"Be so kind, Mr. Lucas," she said with her curious sour-sweet smile, "as to refrain from interrupting until it is your turn to speak."

"He claims that the diamonds are false. In reply to these statements both I and my husband say flatly, that we know nothing of Sybil's secret lover and that when the necklace was handed to Mr. Lucas the diamonds were diamonds. Mr. Lucas, it seems, wishes to have something done about the matter. What he wishes, and why, I do not understand. But what we require is that the false diamonds are replaced instantly by real ones as good as those we handed to Mr. Lucas, and at once, as Sybil was twenty one years old yesterday. It is upon that point we wish you to arbitrate."

She ceased; "Lucky" Lucas groaned slightly, and Mr. Hardaway took a long pull at his tankard—a comparatively silent pull.

Prosper turned mutely to Mr. Lucas.

"'ad," said that unlucky person, feebly, "up'ill and down dale. Properly...."

The lady's lips curled in icy disdain, but she said nothing. She merely sat there, looking as pleasant and sweet as a tarantula.

"Please state your case, Mr. Lucas," said Prosper.

Mr Lucas who was plump, bald, a man nearing middle age, wiped his brow with a bright silk handkerchief.

"Mrs. Hardaway told me that the young lady wasn't engaged to nobody and that it would be easy to arrange the marriage." he said, "And she said the necklace was worth a thousand pounds. I made a mistake in not examining the necklace when I got it home. I'll own that the necklace I saw here in this very room when we settled it and I parted with the five hundred looked like di'monds—I could have swore they was di'monds--but well, they ain't. They're glass. When I found out—from a friend o' mine at Bournemouth that Miss Sybil was a-carryin' on with her gent over the school wall, sort of, I takes out the necklace out o' my safe—and in a flash I sees tain't di'monds at all. Why, look here, it ain't fair!" Mr. Lucas began to get excited. "Have I gotta lose every think damme! Have I gotta lose the girl—God bless her pretty little face. I don't blame her for it—but have I gotta lose her, and the five hundred I lent, and, on top of it all, buy a thousand pounds' worth of di'monds to replace the di'monds I never had! Lord lumme, some people haven't got half a neck on 'em!" concluded Mr. Lucas, in his emotion throwing restraint to the winds. "I'm willing to give back the necklace I was give. And maybe knock a few pounds off the five hundred I want back, but I'll do no more!" And so concluded the speech for the defense. Prosper looked at Mr. Hardaway. But that gentleman had nothing to say. He was engaged—still silently—with his tankard.

"I see," said Prosper, very truly. He saw everything, and though no sign of it appeared on his unruffled countenance, all his sympathy went out—not to the razor-edged Mrs. Hardaway, nor to the enamoured Mr. Lucas, but to the daughter of the late Mr. St. John Singleton. What was she doing at school at the age of twenty-one? Obviously she was kept there by her stepmother and her stepmother's second husband to be out of the way. They were trustees of her fortune, and presumably her guardians—but she would have been better off with a brace of wolves for trustees and a pair of vultures for guardians, reflected Prosper.

Mr. Lucas was all very well in his way but it was not a way which would appeal to any decently educated and even moderately well-bred girl. The man was a rough diamond, possibly well-to-do, but the modern girl of twenty one, when money is not an object, has very little use for rough diamonds.

Prosper rapidly turned it all over in his mind. The fact that the Hardaways and Lucas were willing to submit their case, presumably with the intention of abiding by his decision, to a stranger, was overwhelming proof that none of them were sufficiently clear of conscience to submit the difficulty to the right person—namely, a judge in a court of law. And people who are chary of the law usually have their reasons therefor. Prosper wondered how deeply the worthy "trustees" had eaten into the girl's fortune. Unless there was some shrewd old solicitor watching her interests he feared that now she was of age Miss Sybil would discover that very few interests worth watching were left to her.

But that meant the Hardaways were criminals! Prosper realized that perfectly. He decided to be frank.

"I am sure that you will not misunderstand me when I say that the whole business seems to have been seriously improper," he said, quietly. "To raise money upon articles of jewelry held in trust...."

"I disagree," snapped Mrs. Hardaway. Prosper nodded.

"You are entitled to do so," he said. "What says Mr. Lucas? Do you disagree, too?"

Mr. Lucas looked anxious. "Well, I dunno," he said. "I shouldn't want to mix little Miss Sybil up in anything that wasn't straight. I'd sooner lose the money—damme if I wouldn't. Five hundred won't break Landseer Lucas, come what may." Prosper warmed to him.

"That is very graceful and chivalrous of you, Mr. Lucas."

"You are not asked to arbitrate upon grace and chivalry," said Mrs. Hardaway, chillingly; "will you be so good as to confine yourself to the plain facts."

Prosper bowed, smiling.

"Again, dear lady, you are right." he replied. "Come then, to facts. I may take it—to be perfectly frank, that Mr. Lucas suggests that the false necklace was substituted for the real one after he had seen it and paid the five hundred pounds but before he left this house with a necklace in his possession. Is that it, Mr. Lucas?"

The lady stiffened.

"Yes!" said Mr. Lucas simply.

"Contemptible, detestable, unspeakable liar!" observed the lady-like Mrs. Hardaway viciously, and Hardaway, upon whom his diligence with the tankard and probably many previous ones like it appeared to be having its inevitable effect, leaned across the table and fixed a serious but somewhat glassy stare upon Mr. Lucas.

"Mus'n gosfar as saying thing li' tha' Lucas ol' pal. Ver' grave sta'ment—mus'n gosfar as say such grave sta'ment—'quivlen' to 'cusin' me and Missisarraway bein' thieves. Prally speakin'—tha's 'ri', ain't it, 'vangeline?"

"Evangeline," however, did not appear grateful for her husband's well-meant if somewhat blurred intervention. She stood up sharply, ignoring Mr. Hardaway for once.

"I understood that you were an arbitrator in search of employment," she snapped. "Will you kindly arbitrate instead of gossiping with these—these pot-house loungers."

Unruffled as ever, Prosper bowed.

"I will," he said.

But he did not—for at that critical moment the door opened and a girl, exquisitely pretty, and sumptuously befurred, came in hurriedly. Behind this flushed vision hovered a young man.

"Sybil!" said Mrs. Hardaway, in a voice like the Northeast wind straight "off the ice." "What are you doing here?"

"Miss Singleton," muttered Lucky Lucas, rising.

"No, no—not Miss Singleton any more," cried the girl, laughing. Mrs. Hardaway gripped at her chair, paling.

"WHAT d'you mean? You ought to be at school.

Have you permission to leave the school to-night?"

she demanded, in the voice of one who fights a lost

cause.

"Why—don't you guess, mother?" The girl half turned, and the hovering young man stepped alertly to her side—a trim, clean-cut, good-looking person, carefully clad.

"Miss Singleton is now Mrs. Bay-Rigby—my wife!" he said, simply. "I hope there are no objections. I am respectable—if a flight-commander in the Air Force is respectable. I have not heard anyone deny it."

He advanced to Mrs. Hardaway smiling, offering his hand.

"We were so much in love with each other that we could not wait for all the formalities, and we were married in Bournemouth this morning," he said. "We have motored over to tell you. Please be pleased, dear Mrs. Hardaway."

But the lady was far from pleased. On the other hand she was staring like one who sees an unpleasant vision. Prosper thought she was trembling a little—and he observed that Hardaway had suddenly become completely sober.

It was Lucky Lucas who spoke. He was staring at the girl as a poor man stares down a grating through which he has let fall his last half sovereign. Then he reached out a fat, red hand and shook cordially that of Mrs. Bay-Rigby.

"I hope you'll be happy, Miss Sybil," he said, with an effort, but sincerely. "Though, mind you, it's hard work to say it ... But there, I ought to of had the sense to know the likes of you wasn't for me.... Lucky Lucas, eh?... no chance—not so much as a look in agin 'im!" He waved a hand at the extremely presentable Flight-Commander, and proceeded, muttering, half to himself. "Must of been mad—as mad as a hatter to think of it! Couldn't be done, not no-how—not by no manner o' means. A dealer in antiques, rose from an errand boy—an old furniture-sale sharp—competin' against a—a—heagle of the hair!... That ain't competition, Miss—Mrs.—Briggsby —It's asking for it! ... Well. I've got it. All right—no 'arm! Shake hands, sir. You was wise to fly away with her when you had the chance!"

The flying man seemed to understand, for he shook hands readily. At any rate, he was a sportsman.

"I agree," he said.

"And," persisted Mr. Lucas—who also was a sportsman, "if you two young couple happen to fancy a nice little bit of Chippendale for a wedding present—Chippendale, mind you—jest call at Lucky Lucas's shop to-morrow. Here's my card, Mr. Briggsbury ...!" He turned to the staring Mrs. Hardaway. "We'll settle up our business another time, Mrs. Hardaway." he said. "Good-night, all!" and so lumbered out of the room. Prosper never quite forgot the curious expression on his big, flushed face as he went. The eyes were like those of a dog in pain, and the mouth was drawn down, ludicrously but pathetically like that of a child on the point of tears. It was quite absurd that a man like Mr. Lucas should dream that such a girl as Sybil Singleton could ever have been for him—quite absurd, but it hurt him just as cruelly as if he had been Apollo, and it was apparent that the sweet Mrs. Hardaway had led him to believe that he had a chance.

Prosper thrilled with a sudden anger against this woman. He stood up, smiling.

"How are you, Bay-Rigby?" he said.

The flying man glanced keenly at him. They were old friends.

"Why—Devizes!" he stepped nearer. "You are the Duke of Devises, aren't you?" He hesitated a second, then offered his hand. "How are you. Duke? What are you doing here? I saw you in Paris a week ago!"

Prosper shook his head.

"An optical illusion, my dear fellow."

But Bay-Rigby was not convinced.

"Very well. But there was a chap dining at the next table who had helped himself to your name, and appearance!" he insisted.

Prosper looked thoughtful.

"Well, we will discuss that ingenious gentleman presently," he said. "Meantime—" he turned to Mrs. Hardaway. "I will complete my arbitration, if your wife will forgive me for one moment, Bay-Rigby."

But Mrs. Hardaway turned on him with a gasp.

"For God's sake, no!" she cried.

Prosper looked at her steadily.

"You leave me to infer that everything is not in order," he said, slowly.

She knew that this was a veiled allusion to her stepdaughter's little fortune.

"It can be arranged," she gasped. "Yes—arranged." She saw that his eyes were implacable—that he meant to expose her to the girl she had robbed.

"It you inflict that humiliation upon me," she said hoarsely. "I will kill myself. You don t know the difficulties I have had—the sacrifices I have made."

The girl, startled, caught her husband's arm. He was looking at Prosper's face and he knew Prosper of old. Perhaps, also he guessed many things. But at the touch of his wife's hand he spoke.

"I am sure the Duke of Devizes is too kind to spoil the homecoming of a happy wife—and of an old friend," he said slowly. They were all looking at Prosper—so that Prosper was the only one of them who saw the left eyelid of the flying man close for an instant.

Prosper softened at once. After all, Bay-Rigby was a very wealthy man—he could settle upon his wife far more than she had lost, and be happy in doing so.

So he smiled at Mrs. Hardaway, immensely to that lady's surprise.

"All's well, madame," he said, "let it be forgotten."

She stared at him a moment, amazed.

Then, in a softer tone than he dreamed she could use, she said. "Thank you. Perhaps I don't deserve it.... But I am not so much to blame as, perhaps, you think."

She tried to smile pleasantly—and nearly succeeded. There was only the merest soupçon of the lemon in it. Prosper realized that she had done her best, and—let it go at that. He bowed to her, and turned to the girl.

"Dear Mrs. Bay-Rigby, try to forgive a man who, from birth, has been afflicted with a tendency to be—theatrical. He means well.... Please accept the sincere good wishes and congratulations of an old friend of your husband."

She did so, very prettily—and Prosper moved to the door.

"When you are at liberty, Bay-Rigby, try to spare me a minute. I would like to hear more of the gentleman in Paris.... You will find me in the barn!"

Mrs. Hardaway stepped forward, horrified. What! A Duke consigned to the barn! The barn! A Duke!

"Oh. but—Your Grace—" she began.

But His Grace was gone....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.