RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image generated with Microsoft Bing

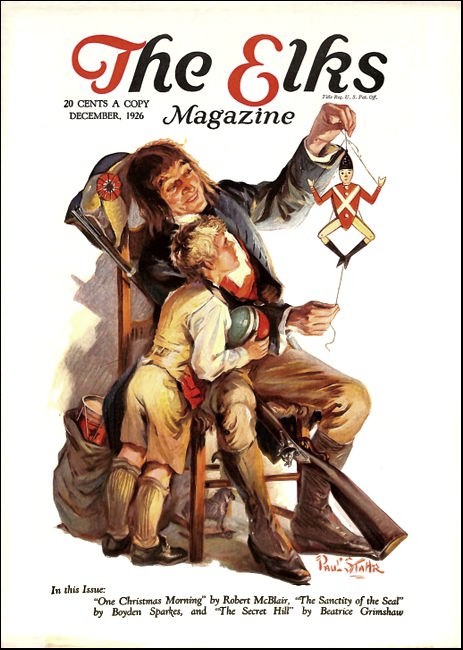

The Elks Magazine, December 1926,

with "The Crusade of Mr. H. Busher"

C. Leroy Baldridge's illustrations for this story are not in the

public domain and have been omitted from the RGL edition.

"AND now, my littles, we really must go home. Life, my dear Plutus, is not all holes and hedgerows; absurd though it may seem, there are duties. All sorts of duties. Rats, for instance. There are rats at Derehurst as well as everywhere else—and I imagine that they must have been enjoying a comparatively easy time since you have been away. I have no doubt that they have become fat and lazy and self-centred—which is bad for a rat. I believe you will agree with me, Plutus, that we must inquire into this—stir them up a little—enliven them, in fact," said Prosper, as, on a sunny but rather cold morning, he finished his after-breakfast cigarette.

He rose, throwing away the cigarette-end, and inspanned.

This was two days after the little matter of the Hardaway-Lucas misunderstanding. Prosper had parted with Flight-Commander Bay-Rigby with the intention of seeking out forthwith the ingenious and daring young scoundrel whom Bay-Rigby had met in Paris, posing as the Duke of Devizes, but, on reflection, he abandoned the idea for the time being.

"Why should I rush feverishly to Paris in order to run that individual to earth?" he had asked Patience. "He can do me but little harm, if any, and I have no doubt that a few telegrams will serve my purpose equally well. It is practically certain that he will impersonate me too long—for I would have you mark, Patience, that the essence of the art of successful impersonation is brevity—and then he will find himself accommodated with a period of comparative leisure during which he will be able, poor fellow, to tabulate and study the mistakes he made."

And so, having sent his telegrams, he had airily dismissed the matter from his mind, and had set his face toward Derehurst.

The first day of the three which Prosper proposed to occupy upon the journey home passed pleasantly but uneventfully—save for a brief though enthusiastic flurry between Plutus and a yellowish dog twice the semi-terrier's size, who very rudely tried to steal a most alluring hole from Plutus. It was the abode of a bank vole, and certainly belonged to Plutus, for Plutus found it and was carefully investigating its aroma before the yellow dog came round the corner. But the newcomer had coolly gone up and pushed Plutus away from that valuable hole in the most deliberate and insolent way. Plutus, naturally, did not take that sort of thing lying down, and promptly had engaged the yellow one in mortal combat. Before Prosper could separate them they rolled right under Stolid Joe's feet, much to the elephant's irritation—for if there was one thing which Stolid Joe disliked it was having strange dogs rolling about under his feet. So he had picked up the yellow thief in his trunk and carefully flung him into a convenient pond. Plutus, who happened at the moment to be hanging on to the hole-stealer's ear, accompanied him. They went in semi-detached, but they came out completely detached, and remained so, for the instant the yellow mongrel reached dry land again he departed at a really remarkable speed, uttering what appeared to be sounds of frantic encouragement to his own legs to move faster.

But beyond that nothing exciting or even deeply interesting occurred.

It was not until lunch-time on the following day that they made the acquaintance of Mr. Herbert Busher.

They had definitely emerged from the more heavily-wooded district now and had come again to the region of rolling downs, chalk-hills and sparse, wind-stunted bushes. They had stepped aside, as it were, from the road and halted for the meal under a few gaunt firs—they always chose firs whenever possible because the noise of wind blowing through firs is so pleasant and sea-sounding, especially when you close your eyes for a few moments, lying flat on your back—and Prosper was about to embark upon a voyage of discovery into the interior of a large pie obtained overnight at Salisbury, when Mr. Busher, white to the knees with the chalky dust of the roadsides of that region, bore down upon them, with a blunt request for a drink of water.

"A drink of water," said Prosper, regarding Mr. Busher. "Of course. If you prefer water. But coffee will be ready in a few minutes. It is not bad coffee. Wouldn't you prefer coffee? Coffee and pie, now. What do you say to coffee and pie?"

MR. BUSHER said that he took the offer of coffee and pie very kindly, and withdrawing his first proposal, accepted the offer in the blunt, honest, downright fashion which was characteristic of him. He was a large young man, evidently accustomed to manual labor connected with iron and oil and things of that kind. Prosper saw that from his hands. Not that Mr. Busher was dirty—by no means. He merely had a blacksmith's hands. He was rather weighty in his manner, and simple, direct, blunt and terse of speech. He might have been twenty-five years old, and the deep, permanent frown which he wore between black eyebrows looked a little premature and out of place upon his youthful, rather square face.

The pie was quite in order, as was the coffee. They finished both between them, without undue difficulty. Then Mr. Busher accepted a cigarette and they chatted, There was never a more skilful "drawer-out" of untalkative people than Prosper, and though Mr. Busher was obviously not given to idle chatter, he was so plainly burdened with a grievance that Prosper had no difficulty with him at all.

He had come from Weymouth, he said, where he worked in a blacksmith's shop and he was going to see a man (rather grimly, this) somewhere up near Basingstoke way. Things being slack at the shop, a holiday being due to him, and having recently suffered the loss of a sum of money, he had economically decided to make the journey on foot rather than by rail.

Prosper, perceiving that Mr. Busher was probably quite an ordinary, honest, hardworking everyday person, not encumbered with a superfluity of ideas, wished him all possible success and relapsed into dreamy study of his cigarette smoke. The silence that followed was broken by Mr. Busher.

"HAVE you ever seen one of these Dukes, sir?" inquired Mr. Busher presently.

"Dukes, my dear Mr. Busher? Why, yes, I have seen several. Indeed, I may even say that I know one or two personally!"

"Ah!" said Mr. Busher. "And what sort of men are they, sir? Not up to much, I s'pose. Leastways, some of 'em, I mean."

Prosper reflected

"There are some black sheep among them, of course, as in every walk of life," he said, presently. "But on the whole, Mr. Busher, on the whole, I think we can call the average Duke a moderately decent sort of man. Average, you know. Not very intellectual, of course, but not very foolish either. Just medium. Live and let live sort of men, you know—I am speaking of the average Duke. Most of them seem to expect a little deference from the mass of people, of course—but since the mass of people appears heartily to approve of the system which produces and maintains Dukes, and so forth, I think they are justified in expecting that deference. It is the way of the world, isn't it? And even Dukes usually have to defer to some one else—Duchesses, as a rule. But to sum up, my dear Mr. Busher, you may safely assume that the average Duke is a well-meaning, easygoing, harmless enough sort of man. Why do you ask?"

The blacksmith flushed a little, and his frown deepened.

"Well, sir. the fact is I've got a grudge against one of 'em. A big grudge, 'tis, and to tell the truth, it's what I'm going up to near Basingstoke to pay off."

Prosper was interested now.

"Indeed! I am sorry to hear that, very sorry. Has this Duke, done you an injury in some way, Mr. Busher?"

"Yes, sir. In a very artful Way. He got mother to change him a cheque for ten pounds. It was my money—savings—she let him have, quite willing, him being a Duke. He was staying at Weymouth on a visit, and he had apartments, next door to our house, Mother lets apartments, too, and when her neighbor, not happening to have any change, brought her the Duke's cheque, she changed it for money out of my box. I don't blame Mother—but 'twas a pity. She usually gets the butcher to change cheques she gets sometimes for her rooms into his account and give her the money when the bank has passed the cheques. But the bunk wouldn't pass the Duke's cheque. They told the butcher it was a bad 'un, forged, most likely. So Mother lost the money—or leastways I did. Now I call that a low trick for a Duke to do. And I'm going to find him out and—" Mr. Busher flushed more deeply, and clenched a great horny fist, "and knock his head pretty near off, if I goes to gaol for it!"

PROSPER nodded. "I can understand your indignation, Mr. Busher," he said. "But I confess I can not call to mind at the moment any Duke of my acquaintance who is in the habit of passing off—er—'stumer' cheques upon landladies. Not one. Do you feel free to tell me the name of the Duke who was guilty of such an unpardonable—er—vulgarity?"

Mr. Busher nodded.

"It was the Duke o' Devizes—the mean thief!" he said feelingly.

"Who?"

Prosper was startled.

"The Duke o' Devizes!"

"The Duke of Devizes! My dear man, what are you talking about—" began Prosper, but stopped abruptly. He must see this thing through—get the facts, obviously. When he had done that, there would be time to explain how absurd the suggestion was.

Mr. Busher grinned a hard little grin.

"It sounds silly, I know. Mother wouldn't believe the butcher for a long time. But, well—look for yourself."

He fumbled in his pocket and presently produced an envelope from which he took a slip of paper—a cheque, which, without relinquishing, he held before Prosper.

It was quite clear.

The cheque was made out (in writing exactly similar to Prosper's) to Mrs. Busher for Ten Pounds and was sighed "Devizes." Also it bore the banker's serpentine scrawl canceling it and the three saddest words in the English language —"Refer to Drawer."

"That's a Duke's cheque," said Mr. Busher. "And it ain't worth tuppence. But I'm going to knock the man's head off, gaol or no gaoL Don't you consider I'm in the right, sir?"

"Indeed I do," said Prosper warmly, "unless this Duke of Devizes can prove that there has been a mistake he deserves it."

"Do you happen to know what sort of a man he is, sir?" inquired Mr. Busher.

"I understand," said Prosper, rising to prepare for the road again, "I understand that he is a well-meaning sort of man—but a bit of an ass. They say he can box fairly well."

Mr Busher grinned again—a slow, tenacious, ominous grin. "I hope he can, sir—for his own sake. I ain't what you might call a scientific boxer, but I can hit like a horse kicking.... Let me lend you a hand with the things, sir!"

WHAT had happened in the matter of the passing of the "Refer to Drawer" cheque was, of course, quite clear. Prosper had realized immediately that for this extremely uncomfortable slur upon his name he was indebted to the financial activities of the gentleman who was impersonating him. Long before the simple-minded blacksmith and he had got upon the road again he had completely reversed his views regarding the soi-disant Duke. He perceived that his original careless idea that the impersonator would not be able to do him much harm was not a correct idea, and he saw that the man must be nipped in the bud with promptness and accuracy, if he, Prosper, was to retain any sort of reputation himself.

"The person is not doing me justice," he mused as they went, at a comfortable walking pace, down the chalky road. "He is neither original nor artistic. He appears to be what is termed a 'bilker'—and bilking is not an art which I admire. We must pounce upon him, Patience—like Plutus pouncing upon a rat-hole. Meantime—what shall we do with Mr, Busher, who appears to be quite a reasonable, honest, hard-working young person? We must consider."

He glanced ahead at Mr. Busher, who was striding along next to Stolid Joe, and lapsed into thought.

Evidently he arrived at some satisfactory decision as to his plan of campaign, for he sent long telegrams to various people from each of the two post-offices they passed during that day.

Mr. Busher was invited to dine with them and stay the night at their camp, and he accepted the invitation gladly. He seemed to have taken a great fancy to Stolid Joe—he was ordinarily of a rather stolid disposition himself—and the elephant, though not enthusiastic, appeared to view the blacksmith with rather less indifference than he did the majority of strangers with whom his master got in touch. Mr. Busher, indeed, made the discovery that there was a dew-pond quite close to their camp, and he volunteered to wash Joseph, whom, it may be said, the chalky dust had transformed into a very passable imitation of a white elephant. Prosper graciously gave permission and between them Stolid Joe and Mr. Busher put in a somewhat damp but enjoyable hour at the dew-pond. Whether the blacksmith washed the elephant or whether the elephant washed the blacksmith it would be difficult to say....

AT the first post-office they passed on the following morning a telegram was waiting for Prosper. It was from Captain Dale, Prosper's agent at Derehurst, and announced that the impersonator had been arrested on the previous afternoon, in a West-End lounge, by the private detectives whom he had engaged in accordance with Prosper's earlier wires, and that the captive was being brought to Derehurst Castle before being handed over to the police, in order that Prosper might have a few words with him.

This was entirely satisfactory. Prosper called the blacksmith unto him. "You are in search of the Duke of Devizes, I understand, my dear Mr. Busher," he said. "I think that I may as well confess to you that I am he."

"You are a Duke, Mr. Fair?"

Prosper nodded.

"I plead guilty," he said.

The blacksmith's bewilderment deepened into acute and palpable discomfort. He scowled, clenched his hairy hands, then grinned feebly, flushed, scowled again, unclenched his hands and finally scratched his head vigorously.

"Well, I'm blowed!" he said.

Prosper waited. He wanted to see how the blacksmith handled the situation. Evidently he was extremely perplexed—"knocked," as he expressed it later, "all of a heap!"

He pondered heavily. Finally he gave a gulp and spoke.

"WELL, I dunno," he said. "I dunno. I shouldn't have took you for the sort of man to do a trick like that. I should have thought you was too classy a chap to steal a working man's ten pound.... You have been a very good friend to me—for a stranger. I can't quite figure it out in my mind that I ought to fight you after the way you've made me welcome.... It's a awkward job. I reckon I shall have to turn it over in my mind a bit.... You and me, we been getting on very well together. It don't seem natural to turn on you, somehow. I'll go so far as to say that I been feeling very friendly to you—and your elephant and all...." He shook his head, heavily, doubtfully. "I should feel sort of ashamed to want to fight you, after eating your victuals, and all that.... I shall have to turn it over in my mind."

Prosper warmed to the man. He was decent—a good sort. A little heavy, a little simple and slow-witted, perhaps, but none the worse for that. His instincts were right. Prosper realized that he was feeling how impossible if was to "knock the head off" a man whose hospitality he had enjoyed. And none knew better than Mr. Fair that the majority of men in the blacksmith's position would promptly have forgotten the hospitality, and would have turned on him like dragons unleashed.

So he explained at once

"Yes, my dear Busher, I am the Duke of Devizes—but not the man who swindled you. He was a fraud—he had taken my name and was impersonating me. No doubt he knew I was touring and a little out of touch with things. The cheque was dishonored, probably because my signature was not imitated well enough. You will be glad to hear that the man who did it has been caught, and is awaiting my—our I should say—arrival at Derehurst, which we shall probably reach late this afternoon. Then we can settle matters with him."

Mr. Busher's face lighted up, and he stepped to Prosper, offering his hand.

"Well, I'm glad to hear that," he said friendlily, "real glad. For I'll own to it that I should have hated to have a row with you, after the way we gets on together."

Prosper shook hands cordially.

"I am in complete agreement with you, my dear Busher," he said.

So that was all right, and chatting amiably and undoubtedly the best of friends, the Duke, the blacksmith and Co. set out on the long tramp to Derehurst....

IT was dusk before they arrived, but Mr. Mullet, the director-in-chief of the Duke's herd of elephants, namely, Stolid Joe—was waiting for them, far down the road. Prosper and Patience were very much surprised to observe how, when still about five miles from home the mighty Joseph suddenly quickened his pace. But their astonishment only lasted for the time it look them to travel the next quarter of a mile, at the end of which distance, Mr. Mullet loomed up through the dusk, yelling uncouth greeting to his old friend the "bull."

"There you be, then, you durned old one-toothed old kinky-tailed old bull! Here's old Harry Mullet awaiting for ye, dam yer old scaly old wrinkled old hide, you old varmint. How are ye—how are ye? Durn yer old hide; old Harry Mullet's glad to see ye again. And he ain't got half a tub full o' hot bran mash—with a touch of whisky in it—waiting for ye! Come on!"

GURGLING, the elephant caressed the old man affectionately with his trunk, wagging his "kinky" tail in the most extraordinary fashion while Mr. Mullet, resting one hand lightly on the solitary tusk of the "bull" strode alongside like a two-year old, talking the most amazing nonsense, asking the most intimate questions, to all of which the elephant seemed in some mysterious way to reply satisfactorily.

"Who's that then, sir?" asked the blacksmith, immensely interested. "Not much manners about him! Anybody'd think 'twas his elephant!"

Prosper laughed quietly.

"My dear Busher, Joseph is his elephant in every sense of the word but the strictly legal sense. He owned him for nearly forty years before he parted with him—technically—to me. Joseph and I are good friends, admirable friends, and he lets me go about with him. But I do not deceive myself—Prosper Fair is simply not on the elephant's horizon when Mr. Mullet is anywhere near. Why, good friends as we are, I have not the slightest doubt that if I as much as raised my voice—offensively—to 'old Harry' in Joseph's presence, the elephant would fling me over the nearest hedge. And rightly so, I would have you observe, Mr. Busher—rightly so. For it would, indeed, be an evil thing if the rich man who buys a poor man's animal friend in a time of stress, were able to buy the animal's love at the same time.... No, the elephant and I respect each other, but Mr. Mullet is the only sun in Joseph's firmament. I am merely the moon. Besides—I am not friendless—not altogether without a little friend on four legs, am I, Patience?" he patted the neck of the little donkey who was, as usual, walking close by his side, and she thrust her velvet muzzle into his hand with a little friendly snuffle.

"Patience is my little friend—and Plutus is ours—isn't he. Patience? And we grudge no man his elephant!... I could not love the 'bull' so much, loved I not Patience more, Mr. Busher!"

Then Mr. Mullet fell back, to pay his respects to Prosper—who, after all, undoubtedly was an easy second in the respective affections of the battered old man and his equally battered "bull."... And there we may leave Stolid Joe—with a good, honest day's work behind him, and the certainty of a hot bran mash, a rest and a lengthy gossip with his best friend in front of him. What could be more satisfactory?

Leaving Patience and Plutus also to the ministrations of Mr. Mullet and Gregory, the Czar of the Derehurst stables who, too, was on the look-out to welcome the Duke. Prosper and the blacksmith made their way to the great house.

They were received at the main door by no less a personage than Mr. Binns, the butler in person.

"Ah, my dear Busher, here is Mr. Binns waiting to welcome us," said Prosper gaily. "How are you, Binns? Well, I hope, and happy. Are you happy, Binns?"

Mr. Binns smiled deferentially, but obviously pleased. For the life of him Mr. Binns could not help liking his master. He was, of course, much too familiar with the servants—really, Mr. Binns doubted whether Prosper would ever learn to "keep his place"—but, well, after all, it was pleasant to know that His Grace realized that servants were human beings and not machines.

"Thank you. Your Grace, quite well and happy." said Mr. Binns, deeply.

"Excellent! How has the gout been?"

"Thank you, Your Grace, much better. Except for an occasional sharp twinge I have been feeling nothing of it, Your Grace."

"Capital, my Binns, capital. Is any one waiting for me?"

"Captain Dale is here, Your Grace, with a young man, and two official gentlemen from London," answered Mr. Binns. diplomatically. "The 'official gentlemen' are having something to eat in my room, Your Grace!"

"Quite so, Binns. I think I will see them first, if you don't mind, Mr. Busher. Meantime, you might see that Mr. Busher is entertained, Binns."

THEY moved away, and Prosper went lo his study. Awaiting him there were two men—one being Captain Dale, the other a stranger—the bogus Duke. He was extraordinarily like Prosper in appearance, but younger. He was sitting before the fire, smoking a cigarette with every appearance of enjoyment, He did not look like a captured felon in immediate danger of lengthy incarceration—nor was he behaving like it. Indeed, as Mr. Prosper and Mr. Busher entered, this cool and self-possessed young man was playfully upbraiding Captain Dale for his lack of hospitality in refusing him a whisky and soda.

"How are you, Dale?" Prosper shook hands with the agent. "So you have captured our playful plagiarist?"

He turned to the "plagiarist."

"Did you have a tolerably good time as Duke of Devizes?" he inquired mildly.

The young man. who had stood up, removed his cigarette with a perfectly tremorless hand and smiled, shaking hid will-kept head slowly.

"Frankly—no," he said, carefully knocking the ash from his cigarette into an ash-tray. "It was wearing, very wearing. You appear to be an extremely popular man, Duke. So many strangers hailed me with every symptom of extreme pleasure, that immensely to my regret on more than one occasion I was compelled to feign insobriety. It was very painful, and I regret it more than I can say. It looks so bad. Money was a difficulty too—a grave difficulty. You see. it is easy to take a man's good name but horribly difficult to acquire his good income at the same time. But please do not misunderstand me. I bear no malice."

He smiled kindly at Prosper.

"To be quite honest with you. Duke," he resumed, "I should not embark upon the adventure again. I do not regret the experience—but, on the whole, I do not propose to repeat it. It was so wearing. It imposed such a strain on all my faculties."

Prosper nodded. "I see. Yes. I imagine that must have been so. I quite see that one would find the number of people one would be supposed to know a serious difficulty," he said thoughtfully.

The impostor smiled.

"But I overcame it, you know," he reminded Prosper gently. "It was the exchequer difficulty which was insuperable."

"You might have forged my name, though!" suggested Prosper.

"I did—once," said the other easily. "But it was a mistake—a moment of sheer desperation. It is the one thing I sincerely regret. It was a pity—a great pity, but while we are on the subject"—his smile vanished and he looked serious—"I may say that I have done my best to put that matter right." He drew from a pocket an envelope containing two bank notes "The cheque was for ten pounds. Here are ten pounds which I have borrowed from a friend. I should be very grateful if you will send them to a Mrs. Busher at 8 Southby Street, Weymouth. She changed the cheque for me. I do not wish her to lose the money.... you see,. my idea was to be a Duke for a little while—not a forger. It was a pity—a pity. I did not anticipate that the cheque would ever be presented. But it will be pleasant to think, when I am comfortably in gaol, that Mrs. Busher did not lose anything."

Prosper took the notes.

"I am very glad you have done that," he said. "Was that the only cheque?"

The impostor laughed again. He seemed to be a person of unusual mercurial temperament.

"Oh, quite, I assure you. Your bank will corroborate me."

Prospers face cleared extraordinarily,

"You must have had a very interesting and exciting time," he said thoughtfully, and—was it possible?—with almost a touch of envy in his voice.

"Who are you?"

"Oh, nobody. 'He was the son of poor but honest and industrious parents and raised himself to his present position entirely by his own efforts.' quoted the impostor lightly. "As a matter of fact, Duke, I was, for a time, valet to Sir James Flair. After that, I became an unsuccessful actor, and, subsequently, a Duke."

"But how did you know about me—why did you select me?"

"Ah!" said the impostor, cryptically, and shook his head.

"You won't say?"

"By no means," returned the other.

There was a pause.

"What are you going to do with me, Duke?" asked the ex-Duke presently.

"Why, on the whole, I think, nothing," said Prosper. "You are an adventurer—so am I. But you have not the means to be an honest adventurer. I have, If I hadn't I should probably be an outlaw. It is all a matter of luck, isn't it? But the question of the cheque does not rest with me. I must leave that to Mr. Busher."

"To whom?" The impostor was startled at last.

"To my friend, Mr. Herbert Busher. He proposes to knock your head off! He is here to do so!"

The impostor laughed.

"Herbert here?" he said. "To knock my head off! Please let him be told that I am wholly at his disposal!"

"You know him?" asked Prosper.

"He is my brother!"

"You amaze me, Mr. Busher!" said Prosper. "I should not have suspected it. '

The young man nodded affably.

"Quite so," he said, "But T have spent a great deal of time and labor upon the processes of self-improvement and self-education and—"

"And Self-Help—or Help yourself.-"'

"Exactly, Duke."

Prosper touched a bell. It was answered by Rosalie—the pretty, blond parlor-maid, whom, it may be remembered, with Marian, the dainty brunette, Prosper preferred to menservants.

"Ah, it is Rosalie," said Prosper, smiling to her. "How is Rosalie?"

But Rosalie did not smile. Her charming face was pale and her blue eyes were troubled and pink-rimmed, and her pretty nose, alas, was red.

Prosper was grieved.

"Why, Rosalie—you are not happy!" said Prosper with genuine concern in his voice. "What is the matter?"

But Rosalie, after one piteous glance at the impostor, suddenly covered her face with her hands and wept as though her heart would break. Prosper would have tried to comfort her but he was too late.

The impostor was at her side in a stride, and the next instant she was in his arms. They heard him whispering to her.

"OH, don't cry, my pretty one—Rosalie—my little one—there's nothing to cry for. It will he all right—yes, all right, my dear, my dear—" he whispered, desperately striving to comfort her.

Prosper and Captain Dale exchanged glances. It was clear enough now where the impostor had gleaned his information as to Prosper's personal characteristics. Rosalie had told her lover—innocently, Prosper never doubled. He, too, moved across to help comfort the little parlor-maid.

"Why, Rosalie, did you think I was going to be harsh and revengeful and merciless? Of course I was not. Listen, Rosalie! I am going to try to help your sweetheart—just because he is an adventurer, like I am—just because I am afraid that, without any money, I should certainly land myself into just such a scrape as he has. Then, when everything is in order, you are going to marry him and be quite happy," said Prosper, in a voice so gentle that it would have amazed some of the folk he had recently met.

Between them the Duke and the Deceiver made short work of Rosalie's sorrow. In a moment, she looked up, drying her eyes and trying to smile.

"There, there, that's much better," said Prosper. "And so you are in love with Mr. Busher, Rosalie? "

"Yes, Your Grace," faltered Rosalie, hesitated a moment, and then with a sudden burst of confidence probably inspired by the rush of relief and gratitude, "because he is so much like you, Your Grace!"

Prosper blushed slightly.

"That is the nicest thing any one has ever said to me, Rosalie,'" he said. "How could I possibly be unkind after that? "

Mr. Busher stepped forward impulsively.

"Your Grace is a brick," he said frankly, "I was not in the least sorry when I came here—but now T am ashamed."

"I have never refused to accept an apology that is sincere," said Prosper, "so, as far as reprisals are concerned, the matter is quite finished. But there is your brother waiting, Mr. Busher. You have still to settle with him. I am sure Rosalie won't mind fetching him for us."

Rosalie did not.

The blacksmith came in alone—blunt, heavy honest scowling slightly.

"This is the gentleman who had the ten pounds," said Prosper. "He had brought me the money for repayment." He handed over the notes which the blunt one took and pocketed.

"Thank you, sir," he said, and turned to his brother.

"Why, it's Jim!" he exclaimed heavily.

"Correct, Herbert," said the impostor smiling.

"Was it you pretended to be the Duke of Devizes and got mother to change the cheque?" asked the blacksmith grimly,

"Unaided and alone I did it," said the other. "Let me explain. I was pressed at Weymouth—I fancied a detective was close on me. I went to mother, told her the truth, and she gave me ten pounds—your money, I know, Herbert. Now, you are a good, bard-working chap... much better and more useful than I am—but if you have a fault, Herbert mine, you are a trifle prone to stinginess. Aren't you? You always were, if you remember.... One moment—let me finish, please. Then you shall knock my head off. Mother knew there would be trouble—gnashings of teeth—when you discovered the ten pounds gone, and I suggested that she should hold the cheque to show you and satisfy you until I returned the money. It was not intended to be paid into the bank at alL It was merely to keep you quiet until I repaid the money. I was a little late in doing so—my selection was an 'also-ran'... Now, Herbert, I defy you to deny that it was you who had the cheque paid in, not mother, who, I know, would have stood by me. You—being, as I say, a little—er—near, could not endure the idea of a mere piece of paper in your box instead of ten pretty notes, and, so, possibly unknown to mother, you tried to change the cheque with the result that you were referred to the Drawer by the bank—and rightly so!"

THE dull flush which spread over the blacksmith's face proved the truth of what the gay, impudent rascal had said. Prosper turned his bead to hide a smile.

"Let it be a warning to you, brother," continued Jim, "to check the habit of avarice. You work hard for your money, I know—none better. And I understand how hard it must be to part with it—and so I bear you no malice.... but don't let it happen again!"

The blacksmith opened his mouth, shut it, opened it again, and, finally, looked mutely to Prosper for help. Prosper understood.

"I am afraid that we are all in the wrong except your brother, my friend. At any rate, he will speedily convince us that we are, if we allow him to continue explaining. Are you satisfied?"

"No, sir," said the blacksmith bluntly. "He ought lo have a good leathering—"

"Ah, yes, the leathering—" jerked the irrepressible James. "I had forgotten that. If His Grace will permit it, I suggest that we adjourn to the gymnasium, where you can administer it, and bring the affair to a righteous conclusion."

Prosper, curious to see the end and scenting a surprise, graciously permitted it, and they adjourned forthwith....

It was all wrong—unjust—unreasonable. The blacksmith was bigger and heavier and stronger, and entirely in the right. "Jim," on the other hand, was entirely in the wrong, and deserved the "leathering" if any man ever did. But—like Prosper—the impostor was something of a past master in the art of taking care of himself.

The blacksmith, poor fellow, lasted exactly one round and a half. He could, as he had said, hit like a horse kicking, but James could dodge like a gnat. And since even a blacksmith possesses a solar plexus, which, lacking a long course of special training, is almost as vulnerable as any other man's, it was only necessary for the ingenious James to visit that fatal spot twice, with two tolerably severe half-arm shots, to put the honest Herbert hors de combat.... much to his amazement.

Then they shook hands and, to be brief, subsequently departed for Weymouth, quite amicably. Rosalie was given leave of absence to accompany them, and so, assured that, providing he kept straight, the Duke's interest would be duly exerted on his behalf, the extremely fortunate Mr. James Busher, his little bride-to-be, and his somewhat heavy brother, Herbert, pass out of the story—en route to the mother who loved them both, but, mother-like, possessed perhaps a special soft spot in her heart for the black sheep....

Prosper turned to Dale, as the Bushers left the study.

"All well?"

"Quite," said the Captain.

Prosper nodded, raptly.

It seemed to him then, for a little moment of illusion, that surely all the world must be happy. It was a mood that did not come so often to him as he liked to pretend it did.

"You know, Dale, I am an extremely fortunate man. Do you think I deserve to he? "

Captain Dale, being military in his habits, was a terse man.

"I am damned well sure that you do!" said he emphatically.

Somebody launched a furious attack upon the door and Dale opened it, to admit Plutus, newly washed and fed, and Patience, clean and gentle and sedate as ever.

"Enter, my littles, and take your ease," said Prosper gaily. "For a while now, my wandering days are done and (for a time at any rate) we must be domestic."

They were, as usual, in complete accord with their comrade, and having said so, with ears and tails, they straightway selected each a comfortable spot on the hearthrug and proceeded to be domestic....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.