RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

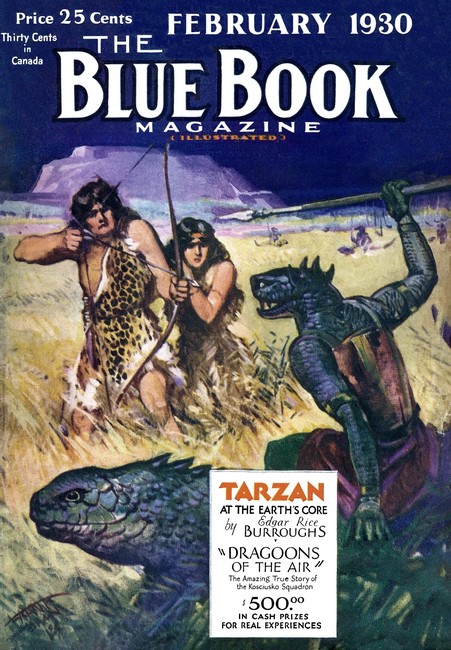

The Blue Book Magazine, February 1930, with "The Indestructible Lady"

"NEVER, as long as you live to encumber this green earth, can you hope to be a golfer!" said the Honorable John Brass heavily to his partner, Colonel Clumber. "No—never! The way you hit at that ball was a disgrace to the League of Nations! They ought to have Total Prohibition, for a golfer like you! Ha-ha! Here, let me show you how you heaved your great carcass at that ball! No wonder you hit it off the map—in the totally wrong direction! Buffaloes could do no more—camels could do no less; but a human being should act a trifle superior to the brute creation."

Mr. Brass leaned smilingly against his brassie and let his lower jaw swing thus with its accustomed facility.

"You're four down now, Squire," he resumed, "and four down you will always be unless you pull yourself together and clear your ideas up a little. This is a game of knack and skill, not a trial of brute force. You're not hammering spikes in the road—you're playing a game—"

Colonel Clumber completed the process of inhaling an amount of air equivalent to that which he had lost in the explosion to which he had given terrific utterance on making the rotten shot which Mr. Brass was so freely criticizing.

"Listen," he then said. "I want no more of your valuable advice—no more of it! You play your game, and I'll play my game. When I feel I've got something to learn from you about golf I'll let you know. I'll stop the game and request you to deliver a small lecture on golf, you poor old twenty-four handicap, grave-digging, mole-frightening, grass-cutting, bunker-wrecking specialist! Four up! You are four up, are you? I don't know of a single thing that strikes me as being of less consequence than you being four up on me—"

"There's no need," interrupted Mr. Brass stiffly, "to be rude over a game of golf that you're losing! If you are the sort of player that doesn't care to take advantage of the friendly interest of a player like myself in your game—why, you aren't. That's all. But you're wrong, Squire. Some time you'll see it for yourself. There's no need to be rude and hot and angry with a good friend who asks nothing better than to be allowed to put you right about the science of the thing. I'm not a professional—I don't charge you anything for my advice—it's free—"

"I pay you what it's worth—nothing!" shouted the Colonel, apparently maddened at his partner's cool assumption of such colossal superiority.

"Well, well, don't holler about it—you are getting folks looking at you. Here's one old lady already tearing over to see what's wrong!"

The Colonel glanced over to see an old lady hurrying toward them, evincing every conceivable symptom of joining in the conversation. He suggested his present notion of an ideal health resort for all interfering old ladies, sullenly dropped a ball and resumed the battle with singular ferocity.

Then the partners strode with true golfing gloom down the course.

WHEN he reached his ball, Mr. Brass paused before addressing it to glance back at the old lady.

She had not followed them far, and now was just disappearing along the trees bordering the links with her arm in that of a tall girl in a brown-and-orange jumper.

His caddie followed his look.

"That's only the old lady who lives in the red house you can just see at the twelfth, sir," he volunteered. "She's childish, sir."

"Ah, is she so, my lad? Humph! There are times when I wish I was childish myself. Just give me that mashie," he said, one keen eye on Colonel Clumber not far distant.

He lost that hole in spite of his partner's lack of science, knack and skill—as he did the next—and the next.

Consequently, he was in but a dourish and fumesome mood when a little later, at the twelfth hole, he was approached by the girl who had led the old lady away.

"I am so sorry that my mother interrupted your game," she said, smiling upon the Honorable John. "Did she bother you —talking? She is very fond of talking to people—strangers—she meets on the golf links."

The Honorable John's quick, rather hard eyes played over her—without much interest at first, for he was absorbed in his game. But, quickly enough, a new interest appeared in his expression, for he realized at once that she was an extremely handsome woman in a tall, athletic sort of way. She was obviously no longer a chicken (as Mr. Brass mentally expressed it) and she looked to be a woman of no little experience, worldly wisdom, and understanding. "Too much, in fact!" thought the Honorable John as he beamed on her, and began to explain that the old lady had not bothered them at all. A far less astute adventurer than Mr. Brass would have noticed the look of undisguised relief which gleamed for a moment in the bold dark eyes of the woman.

Then she smiled, said that she was glad, wished them a pleasant game and turned away, taking out a cigarette-case as she strolled toward the little red house just visible among the trees.

The Colonel looked after her approvingly.

"A fine woman, that," he asserted. "Big, strong, healthy specimen of womanhood—just about my style."

But Mr. Brass, for once, did not set out to prove that she was really much more his "style" than the Colonel's. On the contrary, his gaze was thoughtful as he stood watching her go.

"Maybe, maybe she's your style, Squire," he said. "But something tells me that if you picked her out for a wife, she'd liven up your ideas before you'd been married long! She's hard, that young lady is—iron could be no harder, if I am any judge. There's something about her I don't much fancy. I admit it was very polite of her to come over ready to apologize for her ma, and so on, but—was it necessary?"

But the Colonel only laughed.

"I guess when a girl like her sees a man like me on these quiet country links playing a fine bold overhauling game of golf like I am, now I've run into my true form —you're only one up now—she's got a right to come over and try to scrape an acquaintance with me on any excuse!"

He chuckled, charmed with the idea and even more with the look on his partner's face.

"I've got an idea I shall see more of that young lady before this little holiday is over," he declared, vaingloriously. "Stand back—it's my honor."

Mr. Brass stood back in an unusually submissive, almost absent-minded way. They drove in silence, and trudged on down the course—the Honorable John to the rough on the right, Colonel Clumber to the rough on the left.

"Did you say that old lady was childish, boy?" Mr. Brass demanded of his caddie.

"Yessir. So folks say," replied the youth, "Hum! What's their name?"

"Duxtable, sir. The old lady is the young lady's ma-in-law, sir."

"Oh, that's it, is it, my lad? They all live together in that red house, do they? What sort of a man is Mr. Duxtable? Good golfer, I suppose?"

The small caddie shook his head.

"I don't know, sir. He aint living at home. He lives in some foreign part, so they says about here. The only gentleman young Mrs. Duxtable plays golf with is Mr. Huntingdale, a gentleman who paints pictures about here, sir."

"Oh, is that it? Well, well—just give me that niblick, my boy, and break off that bit of bush growing over my ball."

MR. BRASS was thoughtful throughout the remainder of the game—so thoughtful that it must have interfered with his "knack and skill," for the Colonel beat him by four up.

But Mr. Brass was oddly and most unusually unperturbed about this. He only smiled a little wryly as, walking back to the hotel, the Colonel began to give him some unasked-for advice about his mashie shots.

"You used your mashie as if you thought you were holding a Dutch hoe, man," said the Colonel in his uncharming way.

"Yes, I know," agreed Mr. Brass. "I was thinking. I've got Mrs. Duxtable on my mind."

"Mrs. Duxtable! And who the dickens might Mrs. Duxtable be?"

"That young married woman you think is so much your particular style," explained Mr. Brass. "I am none too well satisfied about her and her mother!"

"That will worry them an awful lot," said the Colonel satirically. "What have they done except be polite to you? As a matter of fact, the girl was out-of-the-way nice."

"Yes, I know," admitted Mr. Brass. "That's what I'm wondering about! I'm not much of a man for the girls—but at the same time I never knew a girl to be out-of-the-way nice except for some out-of-the-way reason."

He glanced at his watch as they stepped onto the veranda of the comfortable little hotel near the links—a quiet, tranquil little course in the heart of the New Forest, known only to the comparatively few golfers who are willing to take a good deal of trouble to find a place where good golf can be obtained with good cookery.

"Lunch in fifteen minutes," said Mr. Brass. "Meantime, we'd better have something to tide us over till then. Personally, I'm all parched up."

When, a minute or so later, the unparching process was in full swing, the observant old rascal returned to the question of young Mrs. Duxtable.

"It's a very small, delicate point, Squire, and few men would notice it—if I hadn't the eye of a hawk and a very quick brain behind it I don't mind admitting it would have escaped even my notice—but there was no real reason for that young woman to come over to us in that way. Her ma hadn't interfered—she never came within range. We were well away and well on with our game when the daughter came up to the old lady. Well, now, she said with her mouth that she hoped her ma hadn't bothered us—but with her eyes she said something else. She was anxious—worried—and when we said the old lady hadn't butted in at all, she was relieved. Why? She was afraid her mother had said something—told us something—she shouldn't have done. And that was why she came over—to find out if that was so!"

Mr. Brass beamed on his partner.

"See, Colonel?"

But the Colonel snorted derisively.

"No, I don't," he said. "I don't see that at all. I think you're fancying things. That young woman was a very considerate, ladylike, attractive party. I liked her and I'm going to ask her to dine here with me one of these evenings. I think you've got hold of a mare's tail—a mare's nest—and if you don't look out, you'll find it'll turn on you and fasten its teeth in the slack of your plus-fours in no half-hearted fashion!"

But Mr. Brass only smiled blandly.

"I knew a bit of fine reasoning like that would get past you, Squire," he said composedly, finishing his aperitif. And he led the way to lunch.

UNLIKE the Colonel, Mr. Brass cut his after-lunch siesta short. It was midway between two and three o'clock when he woke with a start that made the big basket-chair on the veranda groan. He waited a few seconds, then lit a cigar, gazed at his sleeping partner, and strolled away, round to the garage at the back of the hotel.

He found Sing, his Chinese valet, cook, chauffeur and general all-round working machine, concentrating with three other chauffeurs on what appeared to be a form of bitter self-torture performed with ordinary playing-cards, and called fan-tan.

The old adventurer grinned genially from behind his cigar at the quartet.

"So, while your bosses are breaking their hearts out on the links you lads sit here wringing out your souls this way, hey? Well, well, vive le sport, as they say in France," he said. "But I'll have to rob the company of one of its decorations for an hour or two. Just play out this hand, however. I'll watch."

He meandered round the players, glancing at each hand, and halted finally behind an elderly grizzled chauffeur.

"I have got a half-crown which says my friend here will wipe up the floor with all present, bar myself, this deal."

Sing looked up showing his teeth in a parsimonious Chinese smile.

"You bettee half-clown, Master, please? Velly well—I bettee half-clown, please, me winning, Master!"

"You're on, Sing—but you'll win yourself about as much as an old maid's mistletoe wins her!"

Grimly the hand was played.

Mr. Brass was really an observant man, but he failed rather signally to observe just exactly how his yellow retainer won that hand. Yet win he did, apparently without effort.

MR. BRASS stared fixedly at him, then at the cards, then back at Sing.

"You've won!" he said, with a touch of incredulity in his fruity voice.

"Yes, Master, please," agreed Sing.

"But, damme, man, that was impossible!" roared the Honorable John.

"That's what I'm always a-telling him, sir,' said the grizzled chauffeur, sourly. "I ought to have won that lot, sir, as you seen for yourself. He's always scraping out like that, sir. I'm glad he's got to go on duty, sir—he's injurious!"

"He is that," agreed Mr. Brass heartily; and he paid Sing his half-crown and led him kindly but firmly away.

"You want to remember that those chaps have probably got wives and families to support, my lad! I didn't like the way you cleared up that hand. I'll have to take you on that fan-tan game myself one of these days," he threatened.

Half an hour later, the Chink was lost in a very different game from garage fantan. To be exact, he was rather deftly prying open a small window at the back of the lonely little cottage—not far from the red house—rented by Mr. Huntingdale the artist, who, according to the Honorable John's caddie, was such good friends with young Mrs. Duxtable.

Acting on his employer's instructions, Sing had waited under cover of the trees until he had seen Mr. Huntingdale come out from his cottage with a golf-bag slung over his shoulder, carefully lock the cottage door, and stroll off toward the red house.

A few minutes later Mr. Brass carefully concealing his portly figure behind a huge beech not far from the front door of the red house, saw young Mrs. Duxtable emerge therefrom and seat herself on a deck chair. He noticed that she locked the door behind her.

AS she sat smoking, evidently waiting for some one, another person came round, evidently from the back of the house. If the Honorable John Brass had been a party easily thrilled it is possible that he would have encountered quite a thrillsome little jar at sight of this newcomer—for he was unprepossessing to a degree. Short and shambling, squat and square, with legs so bowed that he could have ridden beerbarrels in absolute comfort, and with arms so extravagantly long that he could almost have scratched his ankles without stooping, the creature was a startling contrast to the attractive lady. He was lean and dark and leathery about the features and face; his eyes were small and set extraordinarily deep under craggy brows, and his jaw protruded about twice as far as any normal jaw. And it needed shaving—just as the man's hair needed cutting.

This he-being shambled up to Mrs. Duxtable's chair and spoke so softly that Mr. Brass could not hear his voice. But he heard quite clearly the sharp, clear reply of the woman.

"No, certainly not. Wait till we come back from golf. Then you can go for an hour or two. Meanwhile, get the car ready; Mr. Huntingdale and I will be leaving for London after tea. And this time don't forget to fill up with petrol."

The shambling man, evidently a sort of general handy-man, touched his beetling brow and shuffled round to the back of the house, just as a tall, powerfully built young man in plus-fours sauntered up—a good-looking person in a hardish sort of way.

"Mr. Huntingdale, for a dollar!" said Mr. Brass to himself, shamelessly watching the couple embrace with the air of people to whom an embrace was no novelty, though still a pleasure.

"Ha! Now what would young Mr. Duxtable have to say about that, I wonder?" mused the old eavesdropper. "'Absence makes the heart grow fonder'—of some one present! Hey?"

He watched the couple pick up their golf-bags and stroll off toward the links.

"Allow nothing to interfere with their golf, evidently," said the Honorable John. He waited a few moments, then moved forward to the front of the house.

HE went very silently, for he had no desire to disturb the un-pretty gentleman at the back. Mr. Brass was distinctly a good judge of men—even abnormal men —and he was tolerably sure that the long ape-like arms hanging from that big barrel-like chest were about as strong as those of a medium he-gorilla in good health and excellent training.

It was instinct—developed by a good deal, of dangerous experience—rather than knowledge which convinced the smooth old rascal that there was something queer about this place.

It was not that the old lady was said to be a little "childish"—for many quite charming old ladies are that; it was not that the retainer or serving-man looked like a cross between a chimpanzee and a plain-faced prize-fighter—lots of retainers look very little more attractive; it was not that young Mrs. Duxtable kissed Artist Huntingdale with a finish that hinted at previous practice, for any broad-minded person before condemning her would naturally wish to know something more about the lady's husband.

It was merely the Honorable John's hunting-sense which hinted to him that there was something wrong at this place; it had sprung from his first realization that the relief he had noted in the eyes of the younger woman on the links that morning was greater than the occasion called for.

He was anxious to know something more about the household generally, particularly the old lady.

He had a dim sort of notion that, out of the tail of his eye, he had seen that she was running —apparently to join in the friendly little discussion about the Colonel's poor golf—but he was not certain about that.

"Wish I was," he muttered as he moved forward. "If that old lady had been running hard and the young woman running hard after her, then I should certainly catch just a whiff of rat somewhere... Still, we'll see. Pity the Colonel's got such a habit of distracting my attention from important details. Must mention it to him."

He peered into all the windows at the front of the house—a small, double-fronted red-brick villa without any pretension to picturesqueness—the sort of place a small country builder, enriched by the war, might solemnly erect for his own habitation under the impression that he was achieving a monument to his own greatness.

Everything behind the panes looked normal enough. The rooms were furnished rather sparsely in the normal way—neither well nor ill.

He moved on round the house—rather like a leisurely but inquisitive old bear taking a look around.

There were no signs of the old lady, through any window at either of the sides or the front of the house.

He paused at one of the corners to watch the manservant busy attending to a large car just outside a garage at the back. The man was pouring petrol into the tank. He had a lighted cigarette-end in his mouth. Mr. Brass felt that Sherlock Holmes would instantly have produced one of his lightning deductions about him. Indeed, the Honorable John produced one himself.

"Just a plain damn' fool!" he said.

Then a peculiar thing happened.

A pane of glass smashed itself, or was smashed, in the house, in one of the rooms overlooking the garage.

Mr. Brass drew back just in time to avoid the eyes of the reckless fool pouring petrol into the car under the very nose of a lighted cigarette. A second later the man had dumped down the petrol-can and was running to the back door of the house. The Honorable John got a one-eyed glimpse of him as he went lumbering along rather like a fast land-crab.

The back door opened and shut with a little slam.

"Gone indoors to see what's wrong," said Mr. Brass. "I don't blame the lad."

He edged round the corner, took a sudden decision, and hurried to the back door.

It was ajar. He was by no means inexpert about back doors—so he looked at the inner side of it, saw the key, withdrew it, and closed and locked the door from the outside.

Then he stepped back and looked up at the back of the house. The shattered pane was in the window of a room immediately over the back porch.

Mr. Brass looked wistfully at that rather frail-appearing porch.

"It's not the sort of place for a man of my figure to go scrambling about on!" he muttered, and somewhat reluctantly, began to test the strength of a water-pipe and some Virginia creeper which covered the porch.

"Don't like it," he said to himself. "A man might get a couple of broken limbs playing the fool climbing about a thing like this! Sing's the lad for this—ought to be round about here by this time too —the lazy hound! —Ah!"

He started slightly as a figure appeared silently round the corner of the house. It was 'the lazy hound' Sing, who, acting on instructions, had come on to scout around the red house until he could discreetly join forces with his dearly beloved "boss."

He grinned and offered a package about the size of a brick to Mr. Brass who took it without inquiry, and in a harsh whisper issued his further instructions to the agile tough from far Cathay.

"Get up on this porch quick and quiet, my lad. Just take a peep through that broken pane, make a note of what you see —if anything—then slither down like cats falling and be ready to bolt with me!"

He watched with a touch of envy as the hardy perennial who had worked for him so long and faithfully went up that porch like an alley-cat.

"The lad's got the figure for it. He can climb like a canary creeper," he mused.

Sing took one cautious glance into the room, withdrew his head instantly out of view of those inside, and came down like a sack of potatoes, though more silently.

Mr. Brass darted onto the porch, turned the key of the door, leaving it unlocked, hissed "Follow me!" to Sing and led the way at a portly sort of trot to the cover of the trees.

"Well, what did you see?" he demanded, though already he could guess roughly what Sing's reply would be.

It was about as he surmised: Sing had seen the old lady, sitting gagged and bound in a chair in the middle of the room. One arm was free—clearly the arm with which she had managed to throw a water-bottle through the window. The ugly man from the garage was engaged in retying the loose arm of the old lady to the arm of the chair.

"Huh! I see," said Mr. Brass. He thought for a moment, then glanced at his watch. "Better be getting back to the hotel," he said.

SING stared; it was evident that the saffron-hued scalawag was expecting to join his master in rescuing the old lady forthwith.

But the Honorable John thought otherwise.

"Don't fret, my lad; we shall be back before very long. Haven't you got the brains to understand that we've got to catch the Duxtable-Huntingdale combination red-handed? No, of course you haven't—why should you?"

And he led the way back to the hotel—carefully avoiding the golf-links

In the privacy of his room Mr. Brass took out the brick-shaped package which Sing had handed him.

"Now, what's all this?" he said, and cut the string.

It was money—quite a quantity of it, all in the highly convenient form of one-pound notes.

Mr. Brass looked at his yellow retainer, then at the bale of notes, then back at Sing.

"Humph!" he repeated, "what's all this?" —and turned the lump of money gingerly over with his fingers.

"Have to count it, I suppose, hey?" he observed. "Dry work counting money on a day like this, Sing, my son! We'd better have something. Go and get a small bottle of the champagne we brought with us. That's for me. And while you're downstairs, look in at the bar and buy a bottle of stout. That's for you—you've been a good lad, and I'm one of those who believe in rewarding a good man."

Possibly he was—but evidently he did not believe in spoiling him. However, Sing departed grinning happily, so probably he felt sufficiently rewarded

By the time the leisurely Mr. Brass had counted the thousand pounds' worth of notes —exactly —and gleaned from the stout-imbibing Chink the story of how he had found them hidden in a grandfather's clock which was one of the chief articles of furniture in the almost unfurnished cottage occupied by Mr. Huntingdale, the afternoon was waning, and the Honorable John's champagne had waned entirely.

"I see what you mean, Sing," pronounced the old adventurer at last. "And on the whole, in a way, you might have done worse. I'm not altogether displeased with you, my lad; though, another time, just be a bit more careful. There might have been another thousand in the coalbox. Never rush things. You're getting into a queer, awkward sort of habit of rushing things. Don't do it. However—" he detached one single forlorn-looking humble note from the mass and passed it to Sing.

"There you are—that's for you," he said genially. "Don't fool it away playing fantan with those chauffeurs down in the garage. Keep it—save it up. Men like you with your opportunities, working for a man like me, ought to be worth a lot o' money when the time comes to retire! Hook it now, but keep handy. I shall probably be wanting you in half an hour or so."

DELIGHTED at these few words of what he regarded as praise, Sing withdrew. He was rather like a well-trained retriever. Anything he found in any place to which he was sent by his owner he carried gladly back to Mr. Brass intact, though he would probably have bitten the hand off anybody else who had reached for whatever he was carrying. But it was Mr. Brass who many years before had bought him, unconscious, for a sum which is popularly known as "five bob" from a tired policeman who, on returning home, had found him in the gutter into which certain of Sing's compatriots had tidily deposited him after drugging and robbing him. That had been in the days of Sing's youth and inexperience. He had grown out of youth and inexperience—but not out of gratitude to his possessor...

Mr. Brass, like a giant refreshed, strolled through the sunny peace of the declining afternoon toward the eighteenth green, where he took a seat and a cigar. He had not long to wait. Mrs. Duxtable and Mr. Huntingdale were driving from the last tee as he arrived.

The Honorable John chuckled as he noted that the dour Clumber, evidently having scraped some sort of acquaintance, was carrying the lady's bag, with every symptom of enjoying the job.

Mr. Brass did not await their arrival on the green, as they came on. Like a careful general, he withdrew, "according to plan." From a well-judged distance the Honorable John saw them hole out, noted the lady take her bag, shake off the Colonel —who looked as if he were hanging around for an invitation to tea—and with the man Huntingdale, depart in peace towards the red house.

MR. BRASS awaited his partner, who came glooming morosely along like a man with a wasted afternoon to look back upon.

"Come on, man, come on! Stir your stumps—we've only got a few minutes before us," said the senior partner, as he turned to the hotel and beckoned the distant Sing.

Mr. Brass was watching the dwindling figures of the golfers.

"We'll follow just as soon as they get to the edge of the trees," he said.

The Colonel stared at him.

"I suppose you could give some sort of a guess at what you're driving at—if pressed by a smart lawyer—but I can't!" he said.

"No, I know—I know you can't," agreed Mr. Brass. "I'll tell you as we go. And before we even start I can tell you that you've spent most of your afternoon carting round the golf-clubs of a very dangerous she-crook."

"What d'ye mean—Beryl Duxtable a she-crook?" demanded the Colonel.

"Every inch of her," insisted the Honorable John. "You'll see! Huntingdale's another. There they go—out of sight. Here's Sing. —Follow us, my lad. Come on, Colonel. Liven yourself up a little—for we're on serious business!" Mr. Brass rapped out his orders. so imperiously that even his obstinate partner went along with no more emphatic demur than a demand to be told what was what, then and there.

SO Mr. Brass told him as much as he thought was good for him.

"You mean to say that they got the old lady roped and gagged in that house?" echoed the Colonel. "Why?"

"That's what we're going to find out if we can. And we shall. Trust the wise old thinker of this little firm!" said the Honorable John. "They're leaving for London after tea—and I have a notion that 'tea' means to them a couple of large, brown Scotch whiskies and sodas apiece! I may be wrong (though I'm probably right) but I fancy those two are getting away for good today."

They hurried into the shadow of the belt of trees separating the red house from the links. There Mr. Brass gave his last instructions. All went well.

From the tree they saw the car standing at the front of the house facing toward the main road.

The plain-featured person who acted as handy-man was leaning over the engine with an oil-can.

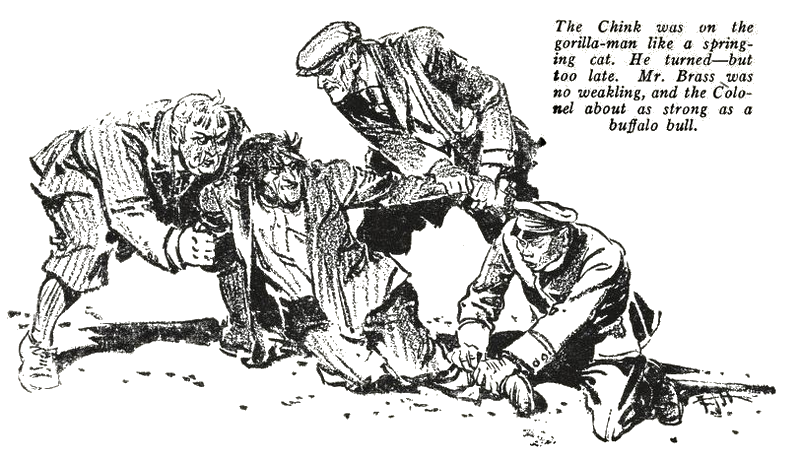

"Couldn't be more convenient," whispered Mr. Brass and signed to Sing. The Chink glided out, and was on the gorrilla-man like a springing cat. He turned with a sort of growl—but he was too late. He was immensely powerful—but so was Sing; Mr. Brass was distinctly no weakling and the Colonel was about as feeble as a buffalo bull.

So they pacified the man without much difficulty or noise, tied his hands, gave him a notion of what a gag, similar to that of the old lady's, felt like, and dumped him down in the car—"to rest," said Mr. Brass.

Then the two moved into the house through the half-open front door. This was evidently one of the occasions upon which Mr. Brass deemed it discreet to depart from his rule of going about his business unarmed, for each of them held now a pistol big enough to blow large holes through a rhinoceros. The Honorable John had thoughtfully brought one for Colonel Clumber.

IN the narrow hall they paused to listen.

Just as he expected, Mr. Brass heard voices—not too loud—in that back room through the window of which the old lady had managed to hurl a water-bottle.

He signaled and they went up the stairs like large and silent grizzly bears.

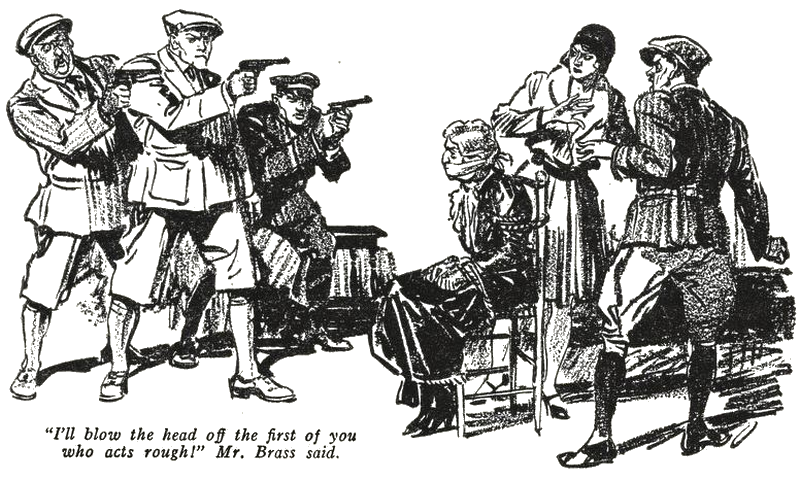

Mr. Brass threw open the door with his left hand, and introduced the battery in his right, following it personally immediately after.

"I'll blow the head off the first of you who acts rough!" he said.

Mrs. Duxtable and Mr. Huntingdale whirled like startled tigers.

But they steadied as they saw the three black pistol muzzles, and the grim, hard, menacing eyes behind those muzzles.

Mr. Brass—engaged as he was on his business —was no longer bland: Colonel Clumber never had known how to be bland, and Sing was about as much like the proverbial bland Chinese as a bear-cat in a hornet's nest.

The "artist" spoke first—and he addressed the attractive Mrs. Duxtable in tones of some ferocity.

"There you are!" he snarled; "there you are! I tipped you off at the eleventh that the cheap old skate was a detective, didn't I? But no, no—you amateur vamp, that wasn't good enough for you, was it? He was just another poor old adorer that wanted to singe his wings in your beautiful illumination, wasn't he? That was what you said—"

Here the Colonel moved forward.

"One more small syllable of that sort out of you, Hubert, and Iíll knock your block out of true!" he growled.

Hubert held back the remaining syllables. The woman did likewise.

Mr. Brass moved up, looking quite deadly behind his awesome firearm.

"Stand back—get back—you two!" he said savagely.

They looked once at his pale jade eyes —and stood back, clear of the mute old lady over whose chair they had been bending. "Keep them so," said the Honorable John to his partner; and Sing bent over the old lady, gently removing the gag.

She was a tough-looking and stringy old lady. "Now tell us, my dear," said Mr. Brass, "Just what it's all about. What your name is, and how much you're worth, and why they did this to you. Don't be afraid—don't—"

"I am not afraid —don't be foolish!" snapped the indomitable old dame. "I am Lady Jane Dumbartington. I live in hotels, mainly, for I will not be pestered by my relatives who are all after my money!"

Her jaws clamped like crabs' claws at the mention of her money.

"These appalling creatures kidnaped me —at least, she did. She claims to be the wife of my only son Gervase—a thoroughly bad lot whom I cut off with a shilling years ago. She says that she is an actress whom Gervase married for her money in Paris some years ago. She says Gervase spent all her money, then deserted her and has never been heard of since. So she, and her friend —bah! —kidnaped me, brought me here and tried to frighten me into repaying the money she says Gervase spent. I gave them some—but they weren't satisfied. They didn't play fair—they kept me here—a woman of my means and standing! When you came they were threatening to kill me if I did not write them a check for five thousand pounds, and a letter to the bank instructing them to honor it. So release me; my man, and lock 'em up—lock 'em up! I don't believe she ever met Gervase in her life. He's a young blackguard, certainly, but he always had good taste!"

"Certainly, Lady Jane. Just as soon as we can manage," said Mr. Brass vaguely, and turned to the two crooks.

"It was pretty barefaced," he said. "Anything you want to say?"

Mr. Huntingdale said nothing; Mrs. Duxtable made a noise like an angry cat.

MR. BRASS thought for a moment.

"But what about this morning, Lady Jane?" he asked. "What were you doing on the golf-links?"

"Why, you stupid fellow, I had managed to get loose and I was running to ask for the protection of two fat golfers—one was rather like you—but she caught me just in time and brought me back. She's a very strong woman."

"I see," said Mr. Brass.

He addressed his partner.

"Just release Lady Jane," he said, "while I get these criminals downstairs into safety."

"Very well."

He jerked his big head at the door, indicating his desires with a gesture of his pistol-filled hand.

Obediently Mr. Huntingdale and Mrs. Duxtable moved to the door and out, followed by the grim Mr. Brass.

"Get into the room on the right," he said savagely, as they went downstairs.

They did so.

"Stay here!" said the Honorable John, looking in on them. "Try any funny business and you will be all stodged up with lead before you can guess what's which!"

He shut the door and locked it loudly.

Then he tramped heavily back up the stairs. But he did not return immediately to witness the release of the Lady Jane, and the heaviness of his steps vanished oddly when he reached the top of the stairs. In spite of his portliness he moved as lightly as a ballet-dancer—lighter, indeed, than some of the "Dying Swans" of recent years—and he moved fast. The second bedroom he entered was the one he sought—that of Mrs. Duxtable.

Mr. Brass already had her fellow-crook's careful accumulation. All that remained to do now was to get the full-blown Beryl's.

It took him just three minutes and a half to find it—the little twin brother to Huntingdale's packet of notes, quietly stowed away in two portions, in the feet of a pair of old riding-boots in a cupboard. Mr. Brass knew he had found it, the moment he set eyes on the boots—they were far too big and shabby for Mrs. Duxtable and the trees in them were sticking out much too far.

"Still, it wasn't a bad hiding-place—for stuff which she thought would never be searched for, anyway," he said blandly; then he put the money where it would do no harm, and returned to Lady Jane and her rescuers.

The indomitable old lady was striding about, talking like one a long way behind with her conversation. She was autocratic, imperious, despotic and inclined to be tyrannical. She demanded that the Duxtable Huntingdale pair be locked up forthwith for all eternity, and she looked as if she felt privately that it wouldn't matter much if Mr. Brass and his friends were locked up with them!

But the Honorable John spoke to her gently, mentioned the close proximity of the comfortable hotel, and was generally soothing.

"I suggest that you allow my friend and me to escort you to the hotel while my servant guards these two people till the police can be sent for them. I have them safely under lock and key downstairs!" he asserted.

She stared.

"Where, man, where? In the cellar?"

"No, Lady Jane—in the front room!"

She wheeled on him.

"Anybody guarding them, man?"

Mr. Brass smiled.

"No—but I've got them locked in!" And he showed the key.

"Why, you stupid fellow, what about the window? Good gracious, can't any of you men ever use your intelligence?"

The Honorable John's jaw fell most realistically.

"Eh? Never thought of that!"

The fierce old lady dashed past him and down the stairs. But she dashed in vain; even as she had so cleverly explained, the two crooks had thought of the window and used it—their car was already fast receding down the drive.

"There—you see, idiot? There they go with nearly three thousand pounds of mine in that car! Oh, I've no patience! Come along, come along, take me to the hotel, and send for the police!"

SO they took her there, and handed her over to the manager—who, oddly enough, proved to be an old acquaintance of hers. He had once managed a hotel she had harassed at Bournemouth.

She was, as the manager subsequently informed Mr. Brass and partner, worth about twenty thousand a year, though she required as much attention as if she had twenty million—and, he added, she wanted to pay for it as if she had about twenty pounds a year.

"A queer, savage old bird," said the manager. "But what can you do? Turn 'em away? Not with the hotel business in its present state! And there are thousands like her—thousands! Drifting about, nagging around from home to hotel, from hotel to hydro, from hydro to—well, you know how it is. These old ladies have got no real vice in 'em, but they're rum 'uns, most of 'em. They outlive the poor mutts that sweated 'emselves into an early grave making the money—and in a year or two they honestly think they made the money themselves. They're fair game for every crook in Christendom—if the crook can get away with it. Mostly, he can't. They're tough. Tough! They're pretty near indestructible, these old hotel-dwellers! I'd hate to be the next crook that tries to wish something onto Lady Jane—Hey, what's that?" He turned to a hovering waiter. "Lady Jane insists on seeing the manager at once! Oh, certainly! Any little thing like that—huh!"

The man made a grimace at the partners and hurried away.

Mr. Brass and the Colonel half-grinned at each other, and went to the Honorable John's room.

"Queer affair!" said the Colonel, over a bottle. "Nice, smart girl, too."

"Who? Lady Jane?" said Mr. Brass satirically. "The other was neither smart nor nice."

"Huh! She was smart enough to get away with her plunder, anyway! One would have thought that such a sharp set of brains as yours might have seen a way for us to make a trifle out of all our trouble."

A WAITER knocked, and entered bearing a box of cigars on a tray.

"With Lady Jane Dumbartington's compliments; gentlemen," he said, and left.

Mr. Brass opened the box, sniffed at the contents, then offered the box to the Colonel.

"Have a cigar, Squire," he said genially. "You see, we have got something out of the affair, after all."

"What?" said the Colonel, smelling at the cigars. "You don't call this box of herbage anything, do you?"

"I wasn't speaking of the material in that box," said the Honorable John mildly, as he drew forth two brick-shaped wads. "I was speaking of this particular herbage! There you are—one for you, one for me, a thousand apiece. I dropped over there and collected it while you were sleeping your lunch off. I'll tell you all about it in a minute. Not bad for the old man, hey? A thousand apiece for us—and a box of something or other to smoke, for Sing!"

"The poor hound!" said the Colonel pityingly.

"Not he, Squire; he'll enjoy 'em—he and his pals in the garage. Pass the whisky, and listen; there's just time to tell you before dinner. The whisky, man—pass it here! Thanks!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.