RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

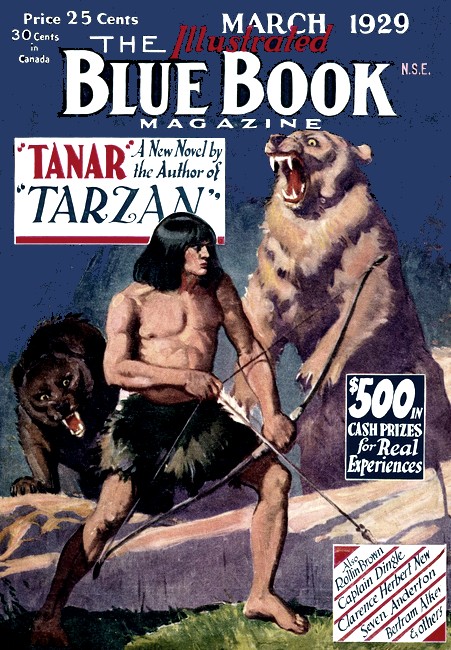

The Blue Book Magazine, March 1929, with "The Haunted Rajah"

THE HONORABLE John Brass leaned back in his chair at a dining-table in his favorite corner of the Medieval Hall of the Astoritz Hotel and surveyed the top half of his rather grim-looking partner, Colonel Clumber, with an expression of good-humored but critical reproach on his large, red, full-fed face.

"It is not for me to pull your clothes to pieces, Squire," he said. "But at the same time, I'm bound to admit that your dress suit is a pretty frightful sight to see. It's not so much that it's green with old age, or that it's about as fashionable as the cartwheel collars they used to wear in the days of Queen Elizabeth—anybody could overlook that in a gentleman; but the thing doesn't fit you, man. It never has and it never will—not while you go to those ungodly tailors of yours! No."

He sipped his wine—if one cared to call the solid pull he took at it sipping—and squared himself heavily back into his own new and undeniably well-cut coat.

"Cut!" he went on inexorably. "Cut's the thing. Like this suit of mine. That get-up you're wearing—speaking as one old friend to another, as old friends can—is doing my reputation no good. To tell you the honest truth, it's high time you spent a few pounds at a first-class tailor's—not that I care for my own sake so much as for yours—"

The Colonel drew in a glass of champagne like one inhaling it rather than drinking it. He set down the fragile glass like a man regardless of destruction, and, his face empurpled with what he evidently considered just anger, rather dangerously screwed his thick-pillared neck about in an effort to see how his coat fitted at the collar and shoulders.

"This suit—" he began. "Why, you insulting—hey, look here! I'll tell you something! Never mind about my clothes! Never mind. What you need to mind about is the insulting way you're getting into of criticizing your best friends—that's it! You're gradually getting to be so much in love with yourself that—"

HE broke off abruptly with the air of an infuriated grizzly sullenly retreating pro tem, as a very large, excessively black gentleman in extremely smart evening raiment came up and hung over their table like a total eclipse.

"How do you do yourselves att present period, I trust, sars—haha!" said this inky arrival, in the species of English which is used without mercy by many of the better educated denizens of India's coral strand.

The partners in picaresque adventure, their friendly if slightly snarlsome differences instantly forgotten, looked up with the keen and welcoming interest which they were ever ready to extend to one whom past experience had always proved the herald of one of those financially happy coups of which the two adventurers were highly skilled executants.

The somber-hued but toothsomely smiling newcomer was, of course, their old friend Mirza Khan, confidential body servant and highly trained go-there and comeback boomerang of His Highness the Rajah of Jolapore, that plutocratic potentate who long ago had made the highly pleasing discovery that by the simple process of spending nine months of each year in London and Paris, he could rule his teeming millions of dusky subjects far more satisfactorily than by baking for eleven months out of the twelve in one or other of his red-hot palaces , in Jolapore.

"Why, it's Mirza! Bless my soul—and his, if he's got one—it's Mirza Khan!" said Mr. Brass, and signed imperatively to the attentive tip-chaser in charge of their table to place a chair for the funereal-complexioned old-timer. "Well, well—Mirza Khan! D'ye notice him, Squire—it's Mirza!"

Even the dour Colonel Clumber beamed —a little morosely, maybe, but still with a sort of gloomy radiance, on the genial scoundrel now seating himself next to them.

"Very happy coincidence, meeting you here, Mirza," he muttered.

But the smooth Mirza, smiling with the genuine affection of the left jaw of a gintrap for the right jaw, denied that.

"Oah, noa, sars," he stated. "Noa coincidence, I assure you. Calling att your flatt thee person of saffron hue, Sing, told me thatt I should find you here eating and drinking."

He shrugged.

"Noa champagne, sar!" he replied to the Honorable John's hospitable gesture with the air of one who has bathed ad nauseam in that attractive if expensive fluid. "I will partake of plain wiskisoda in double quantity."

HIS poison duly set before him, and the greetings being complete, Mirza Khan proceeded to explain himself and to justify his sudden swoop on the partners.

It was in reply to a rather avid question from Mr. Brass that he told them, with every symptom of a man most anxiously uttering the stark-naked truth, that his master, the Rajah, had been in England staying at Shaveacre Castle—which he had rented for the shooting season—for the past month.

The Rajah had come on from Paris with all his suite except Mirza, who had been too unwell to accompany the Royal party.

"Fact of matter being trouble withinside, sars," explained Mirza. "Extremelee good chef in Paris. Yess. Soa veree good that I suffered from grave attack off disability digestive apparatus to accommodate visual estimate off victuals. Thatt is to say in good old Anglo-Saxon fashion 'eyes too big for belly!'—haha! Soa thee doctors operated on me same day as His Highness left for England, taking as bodyservant onlee thee creeping cobra off grass, crocodile off ghat, thee French vulture, Santoin!"

Mr. Brass laughed.

"You never liked Santoin, did you, Mirza?" he asked.

"Noa, sar!" Mirza was vehement.

"Well, what's he been doing this time?" continued the old wise-osopher, pushing his plate—his empty plate—away with the air of a man who has no further use for food.

"Ahaa! Thatt is precise reason off thiss visit upon you, sars!" exclaimed Mirza. "I will partake further wiskisoda and explain thatt!"

He partook, and having partaken, explained in such detail that by the time dinner was over, the pair of sharp-set old adventurers were looking so extremely businesslike and grim that the waiter hardly dared to present his truly formidable little bill—though, with an effort, he just managed to do it, as waiters, stout fellows, will.

IT appeared that His Highness, the Rajah of Jolapore, had started in life with the firmly fixed conviction that he was one of those mortals whom Nature had intended to be happy; one of those joyous souls who only wished to get the best out of life and to be left alone to enjoy the best of everything in his own way. He did not wish to interfere with anybody else, and he did not wish anybody to interfere with him or try to meddle and stop him from having precisely what he wanted exactly when he wanted it.

For some fifty years he had run himself through life according to these naively greedy notions—entirely to his own satisfaction. He had spent millions in pursuit of the things he felt he needed, and, on the whole, had not been swindled much more than could be reasonably expected. Moreover this simple child of nature would have been entirely content to continue—to go on as he had started, so to express it. But, explained the fat and smiling Mirza Khan, certain difficulties had arisen. A bad nervous breakdown from which he had not yet completely recovered, for example. And on the heels of this, an even more serious trouble. For some considerable time past, the Rajah's ancestors had been appearing unto him, at awkward midnight moments, in the somewhat disconcerting form of phantoms. And they had, moreover, developed a truly affrighting habit of talking to him out of the air, so that he never felt certain that the spirit voice of his grandfather would not huskily break in upon his slumbers or maybe his conversation with a friend.

"That's a thundering nasty thing to happen to any man, Mirza, let me tell you," exclaimed Mr. Brass with warm sympathy. "Seeing visions and hearing voices! You mean he's getting hallucinations after his nervous breakdown, hey? That's bad!"

Mirza's face was graver than a graven image's as he nodded over another partaking of wiskisoda.

"Yess, sars, by Jove! Veree bad!" he said. "Speaking as fellow who has studied question to hand, I beg to assure hearty concurrence. The matter off ancestors bobbing up att totally inconvenient moments is question off veree serious nature to Moslem gentleman of rank, fashion and bad nerves."

He explained with a certain grim earnestness how much more seriously than a white man an Oriental would take such unusual and intrusive manifestations.

"Thee educated white man veree naturally would feel entitled to say to spirit, 'Get out—damn' impudence—call again later!' or words off thatt character. But Oriental gentleman would take matter much more seriouslee—oah, yess indeed! There are great quantities superstition running freely to waste, don't you know, in my country," said Mirza. "And phantasms of ancestors who issue instructions to present surviving members off family are not to be ignored lightlee! Noa! We high-born Indian noblemen are ignorant chappies in some aspects, oah, decidedlee yess!"

He spoke sincerely, even if his English was rather crippled in both feet.

"Well, maybe, Mirza. But what is the trouble? What are these spirit grandfathers and folk commanding the Rajah to do?" demanded the Honorable John, not particularly caring, however.

MIRZA looked graver than ever.

"To abdicate his throne! To abandon forever thee luxuries of thee world, thee sins off thee flesh, thee vain things off life, to renounce, in peremptoree fashion, all thee vanities. Thatt iss to say, to throw all behind him, to take onlee begging-bowl and blanket and to goa forth from his palaces to live as simple holy man for the rest off his whole life. That iss sometimes done in India as matter of personal conviction," explained Mirza quickly. "Not soa often as formerly—but sometimes, oah, yess, by all means. A great man, rich, proud, mighty, decides to become poorest off poor. There is noa question off why and wherefore, sars. I cannot explain. It is done—sometimes. There is great story in English literature off such case—written, oah, jollee well, by great master, Mr. Kipling."

Mirza Khan drew breath and wiskisoda simultaneously, as he eyed the partners.

"Well, what of it?" said the Colonel heavily. "I don't suppose the Rajah's going to take any notice of these trunk-calls from the Never-never, is he? A man like him aint going to allow the phantom of his grandfather to upset the whole of his arrangements, is he?"

Mirza shrugged.

"Impossible to explain exact point off view, I see, sar," he said. "His Highness is gentleman of great courage—but owing to Oriental difference off code, off psychology and soa forth, he is in grave danger off reluctantly obeying behests of ancestral ghosts!"

"What's that, Mirza?" Mr. Brass, startled, broke in. "Are you trying to tell us that His Highness is liable to do as his spirits tell him—although he doesn't want to—and certainly isn't cut out for a mendicant holy man? D'ye expect us as men of the world to believe that the Rajah—one of the most dashing sportsmen, for his age, I ever came across—is liable to do such a thing as abdicate because his old grandfather revisits him to say so?"

Mirza Khan's glossy face was glum, and his voice agitated as he replied most urgently:

"I do, sars. It iss matter off absolute certaintee that within short period of few weeks His Highness will be phantasmally frightened into this act of supreme sacrifice unless successful intervention is executed promptly by competent gentlemen qualified to give entire satisfaction, yours faithfully, yess sar!"

The Honorable John thrust out a thickish, rather brilliantly red lower lip, then drew it tightly in again so that his mouth looked like a species of weasel trap.

"Um!" he said. "Umm! Shall have to see what can be done about this! We've got the Rajah out of difficulty before—no doubt it can be managed again! Must look into it, Mirza. Better come along to our flat and have a talk—discuss things—look into the matter—see what there is in it—um—so to put it."

They rose.

THREE days later Messrs. Brass and Clumber were installed as members of His Highness the Rajah of Jolapore's shooting party at Shaveacre Castle—the country seat of the Marquis of Muckhampton, who, advised in no uncertain terms by his advisers to regard himself as a certain starter for the Autumn Bankruptcy Stakes, had decided that he could not profitably continue to sit in his country-seat when a Rajah so rich as His Highness of Jolapore wished to sit in it instead.

It was a moderately motley houseful of guests that the smooth Mr. Brass and his partner encountered, and all seemed to be enjoying themselves except the Rajah, who in the three years which had flitted by since the partners had last seen him, had aged and fattened and dulled. He was pleased, he said, to see them again; and his tired eyes, over the heavy pouches left by half a century of the life luxurious as lived by a gayety-loving, novelty-seeking, enormously rich prince of sunny Ind, lighted up with a momentary flash of pleasure as he greeted them. There had been occasions in the past when they had really been of great service to him.

"Not the man he was, Colonel," said the Honorable John to his partner when they were alone. "No. His nerves have got into a very poor state. His health aint what it was. And he's uneasy—in fact, he looks scared to me. He never was a man easily scared, either. Mirza's right—there's something or somebody, ghosts or devils or just plain crooks, that are working hard on him some way or other. He begins to talk and look like a man who don't care much what happens, anyway. And that's not healthy. We shall have to keep our eyes open and our ears set like sails while we're here!"

TWO days of the eye and ear work advocated by the old expert produced quite a little crop of results—the said crop being greatly enriched by certain discoveries of the Honorable John's yellow valet the Chinaman Sing, who went gliding in his silent, ghostlike way about the castle at all hours of the day and night, making full use of a knowledge of locks so profound that ordinary keys had long since been superfluous to this saffron seeker after knowledge.

The fat and anxious Mirza Khan had helped considerably also, though he had had troubles of his own to deal with. He explained these one day after lunch.

"During my temporary absence from customary duty off personal attendance on His Highness due to recent grave illness withinside, sars, thee cadaverous snake off grass, creeping snipe off Paris gutters, thee man Santoin, had wormed his way into His Highness' good books and committed many. libels to royal master concerning self. But have now succeeded in re-establishing self in former exalted position in His Highness' regard and have pleasure in stating that thee situation is att finger-tips. Yess!"

The burly Mirza grinned.

"His Highness is great gentleman, sars. He suffers misunderstanding att periods, butt always in the end he relies on own bodyservant, self, that is to say, more than the French valet, the creeping creature Santoin, who is veree poor quality person!"

"Sure, sure," said Mr. Brass, who was well aware of the bitter jealousy, the almost bloodthirsty enmity, between Mirza and Santoin. "Now pass the whisky and tell me everything you've discovered. How're the ghosts getting on?"

Mirza looked glum.

"Ancestors have not visited personally for some days but have been extremelee vocal. He has heard at night urgent voices out off air belonging to his father's father, and to thee first ranee—who was adored wife of His Highness twenty years ago—and who died one year after marriage. He has never forgotten her—never loved subsequent wives in same degree. Noa! I wish in strongest fashion to say to you, sars, thatt it has been shock of veree desperate nature to royal master when he lies sleepless at hour off midnight, with self silent as mouse at post in alcove, to hear most lovely voice off long-dead queen issue from air saying, 'Arise now, beloved, cast off panoply of king, shake dust of palaces from feet, turn back on vain things, take begging-bowl, staff and beggar's robe, go forth to spend declining years in meditation, in search for thee true knowledge, wisdom and Perfect Way. For thee dear soul's sake!' Oah, yess, misters, I tell you it is jollee disconcerting to hear dead beloved's voice at midnight imploring such remarkable performance," insisted Mirza uneasily, and dropped his voice.

"It is difficult mystery. There is private detective in castle specially engaged figuring as guest—he is Captain Clanister—but he seems unable to solve puzzle—"

MR. BRASS nodded his heavy head, scowling at his glass.

"Yes, yes, we know about him. But get back to the voices, Mirza. This beloved—the ranee who died so long ago—have you heard her speak?"

Mirza Khan's hard eyes were uneasier than ever as he said that he had.

"Yess sar."

"Did you recognize the voice as that of the dead queen? How about the accent—the dialect—was it right? Was it correct in every detail? Would you swear this spirit voice is the voice of that dead queen? You knew her—back in the old days, I mean?"

Mirza understood.

"Yess sar, I knew her—I was in her high favor for personal devotion and service to Rajah!" he said. "And as she spoke in old days soa she speaks now—even to thee little personal peculiarities such as all persons have in speaking—I heard them again in thee air last night. Oah, it is undeniablee her voice!"

"Humph!" grunted Mr. Brass. "You evidently believe it is."

He sat thinking for a long time, scowling absently at Mirza and the Colonel. He was evidently coming to an important, even vital conclusion.

"Pass the whisky," he said finally. "I see we shall need clear heads for this affair."

He took a stiffish head-clearer and began to ask Mirza a string of questions about Jolapore, continuing the cross-examination so long that Colonel Clumber, without troubling to stifle a dark and cavernous yawn, was moved to protest. "Well, I like music," he said with heavy sarcasm. "And there's no doubt that you've got a very pretty voice—of its kind. But now I'll be leaving Mirza to do the rest of the listening. I've got an appointment to play golf with that attractive niece of old Colonel Standrishe this afternoon."

Mr. Brass stared.

"So do," he said stiffly. "I hardly expected you'd be able to catch the drift of my questions, Colonel. But later on I'll put the thing in simple words and get in a blackboard and a bit of chalk so that I can draw a few diagrams to help you understand."

He laughed, quite restored to good humor by this crushing, if ancient, repartee.

"Ha ha, sar—that is flea in ear in witty fashion," laughed Mirza, who was always charmed with the partners' frequent exchange of heavy-handed badinage.

"Wit!" echoed the Colonel. "That's not wit—it's jealousy because Beryl Standrishe prefers me as a golf partner!" he explained curtly, and left.

It was perhaps half an hour later when the door opened on the haze of smoke in the Honorable John's room to admit Sing, the lemon-tinted lad from far Cathay.

It appeared Sing had discovered something which he desired to show his owner. True, it was in the bedroom of the well-paid private detective, Captain Clanister, but the Captain was out. So they went to investigate Sing's discoveries.

IT was late on the following evening that the Honorable John was quietly introduced into the large and elaborate suite of the Rajah by Mirza Khan for an interview which was to be both private and delicate.

Mr. Brass and the Rajah had met several times before during the day, but by no means in circumstances which rendered a heart-to-heart talk a matter of facile arrangement. They had, for example, exchanged smiles at a corner of the Four-hundred-acre Wood, where the house-party was assembled, heavily armed, with the fixed intention of dealing fairly and squarely with every one of the highly expensive pheasants inhabiting said wood which inadvisedly came within reach. And they had, as it were, recognized each other distantly at dinner—again an occasion when Mr. Brass felt he could not tactfully bawl his most private convictions half the length of a gorgeous table to the host at its head.

The Rajah, whose confidence in the avid loyalty of Mirza Khan had evidently been completely restored, was awaiting Mr. Brass, together with a bottle or two of those matters which history proves to be highly effective lubricants of difficult discussions. It was in his big dressing-room—and his dressing-gown—that he received the genial old adventurer....

"Mirza Khan insists most turbulently that you have information of grave importance to impart to me, my dear Mr. Brass," said His Highness in the suave, pleasant, civilized manner that characterized him when he was in a good temper. "Wonít you sit down and—have a chat with me?"

He turned to Mirza.

"Lock the door and pour wine," he advised that dusky vulture peremptorily.

The Honorable John smiled.

"That's a sound idea—locking the door, I mean—nine times out of ten, Your Highness. But this is one of the tenth times. What we're dealing with goes through locked doors as easily as unlocked, wide open ones."

The Rajah's eyes glowed faintly. "You think so, Mr. Brass?"

"No, Your Highness; I know it." He took the foaming glass which the hovering Mirza proffered him and encountered the Rajah's friendly eyes over the pair of rims.

THE RAJAH set down his glass; Mirza refilled it and vanished.

"They tell me you have something of vital interest to say to me," he said, his deep, dark eyes burning. "I do not know whether that is true; for by God, Brass, I never know whether my servants tell me truth or lies."

The Honorable John waved a large, pacifying hand.

"Well, Your Highness can judge—though Iíll admit that I can't call to mind anybody who was willing to pay me enough to make it worth my while to tell more lies than necessary. Hard work, lying, Your Highness. Still—"

He took from a gold casket, and carefully lit, a cigar. He thought for a few moments,

"Yes," he said presently, "this is a magnificent cigar, Your Highness."

Then, rather abruptly, he went on: "Speaking as a man who has a genuine anxiety to see you continue to enjoy health, happiness and prosperity, I'll say frankly that I don't see how Your Highness can very well expect to gain much by entering on a style of living from which wine and horses and congenial feminine companionship and—er—so on—are all cut out. Cut completely out. You've been used to these things all your life—they're second nature to you. To me, personally the thing's unthinkable," he added, warming up, as usual, at the sound of his own cheery voice. "I'd do it for no man, Rajah! And I've known what it is to rough it in my time, whereas you—"

He broke off. "You'd prefer me to be frank, Your Highness?"

"Oh, certainly—speak as one man to another."

"I was going to," said Mr. Brass comfortably. "Well, now, suppose you do this desperate thing you've been egged on to do. Last night I read up that story by Rudyard Kipling about the Indian Prime Minister, Purun Dass. And a damned good story it is, and the part of holy man fitted Mr. Dass like a fork fits a knife. But I don't see you in the part of a wandering holy man whose only property consists of a skin or a blanket, a staff, and a begging bowl, which peasants will fill—maybe—for your dinner. What will you get, anyway—a little rice, a few little cakes, a bit of ghi or native butter, maybe a touch of rancid fish occasionally, and now and then a bit of sweet preserve—not so sweet at that—and for the rest, fruit and nuts. Fruit and nuts, begad, Rajah! Good enough things in their way, fruits and nuts, as accessories to a real meal, but no more than that, Rajah! No sir—no, Your Highness, the food question alone has got your idea beaten from the start. Lack of proper food, good wine and real tobacco would undermine your physical system in a month —and lack of good clean clothes, of real exciting sport, of riding, and of the tender influence of the ladies, would give you another breakdown in a week—and your good spirits would be—"

"Good spirits! Bah!" growled the Rajah. "Man, I have not been in good spirits for months!"

MR. BRASS smiled. "I know. That's why I'm here. I'm going to make it my business to get you smiling again."

The Rajah's eyes glowed.

"If you can do that, Brass, I will make you a rich man —but you cannot. Unless," he added, with a species of nervous fury, "you can deal with the supernatural!"

The Honorable John chuckled.

"That will be all right," he promised.

"You are confident," said the Rajah, "with the confidence of ignorance."

He brooded for a moment. Then he said:

"Listen!"

In the low, urgent voice of one who is badly nerve-ridden, he told Mr. Brass the story of the ancestral apparitions and voices. Mr. Brass had heard it all before—but it sounded much more convincing from the Rajah than from Mirza Khan. The old adventurer was a little shocked at the evident sincerity of the Rajah's belief in the manifestations of his long dead but still enterprising grandfather—and his first wife.

He smoked quietly and let the Rajah run down.

"—so you see, Brass, that while I dread the notion of becoming a wandering holy man—I dread even more to continue disobeying these—behests. What am I to do?"

He drained a glass of champagne.

"Do? I'll tell you, Rajah, presently. Meantime, tell me something. Who is your heir—the formal, official heir, recognized by the British Government?"

"My eldest son, born of my second wife, the Prince Bahadur Bhil, hah!"

RATHER intently the Honorable John sat watching the Rajah.

"Um! His Highness the Prince Bahadur Bill! Do you get on pretty well together?" he pursued.

The Rajah snapped a thumb and finger.

"When I abdicate, Brass, Bahadur Bhil will step into my shoes smiling," he said. "And if I proffered him my empty mendicant's bowl on the next day, he would probably decline to fill it. My son—by my second chief wife! Doubtless he means well—but he was the son of the wrong wife! Bah!"

"I see," said Mr. Brass musingly. "It's a pity that you feel that you have to hand him a ready-made throne—still warm, so to put it. However—" He shrugged and took a little champagne. Not more than the glass would hold, of course.

He resumed his quiet questions for the next half-hour, at the end of which time the Rajah wearied. The Honorable John sensed that before the Rajah showed it, and rose.

"Well, so it goes, Your Highness. We shall see." He moved through into the next room and indicated a bell-push lying on a table by the Rajah's bedside.

"I took the liberty of having this installed today," he said. "It probably won't be needed, but if you hear any voices or see any ghosts tonight, Rajah, will you do me the favor of pressing this bell the instant they begin to utter or to appear? Don't worry—just ring, Rajah, just touch the button. The old man is on the lookout tonight and his brains were never brighter!"

The Rajah promised.

IT was just as the clocks about the place were striking two that the French valet of the Rajah, Monsieur Santoin, issued forth from the apartment occupied by that ancient Colonel who called himself, probably without any right to do so, "Sir George Standrishe," and smilingly catfooted his way down the corridor in the direction of the Rajah's suite.

After a long day of hard shooting, eating and drinking, the house-party had retired comparatively early, and the castle was silent as a deserted church. M. Santoin glanced about him as he went, but his glances were perfunctory and careless, like those of a man absolutely confident that no eye followed him on his nocturnal perambulations.

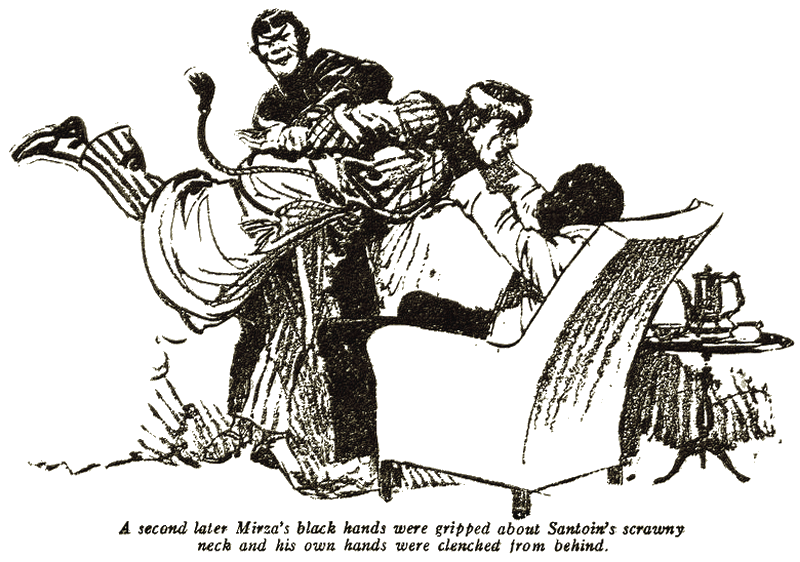

He came to an alcove just outside the door of the Rajah's bedroom and looked in with some interest and no admiration upon the figure of the faithful servant of His Highness, Mirza Khan, as usual on guard while his master slumbered.

He was, of course, sound asleep in his comfortable chair. His mouth was unprettily open and his big arms were lying loosely along the arms of the chair, the great hands dangling over the ends. On a table near the chair was a coffee-set, with the cup empty.

Mirza Khan was extraordinarily still—so still that he did not seem to be breathing at all.

The pallid smile of Monsieur Santoin faded suddenly and a certain sharp anxiety appeared in his eyes. He stepped forward and bent low, sniffing at the empty coffee cup. A fraction of a second later Mirza's two black hands were gripped about his scrawny neck, and even as he gasped at the shock, his own hands were clenched from behind by another pair, small, cool, but disconcertingly sinewy and powerful.

"Silence, snake off grass," said Mirza very softly, and rose, keeping his hands closely associated with M. Santoin's neck. "Come with us, if you please."

SANTOIN perceived that the person in charge of his hands was Sing, and he found no more comfort in the face of the yellow man than in that of the black Mirza.

So he went with them—to the apartment of Mr. Brass, where, comfortably occupying big easy-chairs, the partners were awaiting them. Upon the refreshment table between them, there lay, in addition to refreshment, a couple of the biggest and ugliest revolvers Santoin had ever seen in his life. They were so big that one might have hammered horseshoes out of cold iron with them. And though Santoin did not know it, that was about all they were fit for. Messrs. Brass and Clumber were not in the habit of using arms except for their moral influence, and these bulging bits of artillery had been borrowed temporarily out of the castle gun-room.

The look of sheer ferocity with which the Honorable John received his unwilling visitor would have been worth quite a few dollars to any film-producer.

"So you've brought him, you boys! That's good," he said. "Hold him, Sing, but don't break his arm with any ju-jitsu tricks—at least, not till I say so. I'll let you know presently."

M. Santoin paled noticeably at the implacable ferocity which tinged the Honorable John's voice.

Then the old rascal rose, seemed to inflate himself and looming over Santoin like an impending avalanche, held converse with him in this manner:

"Now, you traitorous fox, 'm going to ask you some questions. You'll answer 'em or I'll put you through not the third degree but the thirty-third! Try to trick me and it were better for you that you hung a millstone round your neck, passed through the eye of a needle and ran down a steep place into the sea—like that fellow in 'The Pilgrim's Process' or some such title. Mark you that, my lad!"

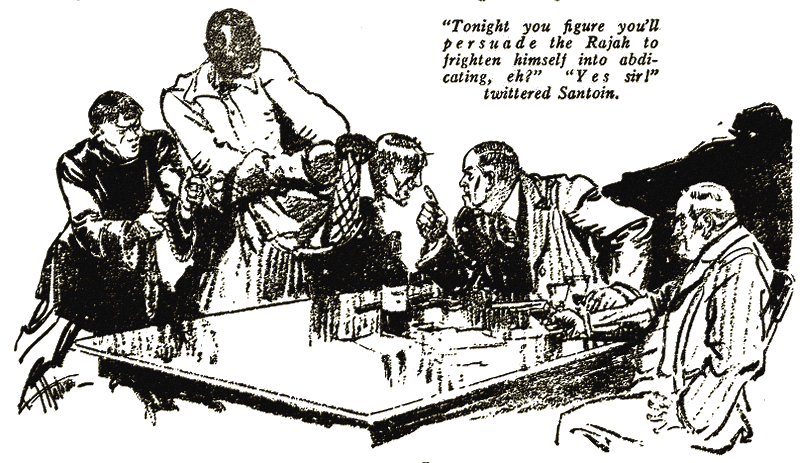

EVIDENTLY Santoin marked it, for he proceeded to betray his associates with a fluent and easy technique in the art of betrayal that could only have been the result of very much practice.

"Tonight you and your friends figure that you'll supernaturally persuade the Rajah finally to frighten himself into abdicating, hey?"

"Yes sir!" twittered Santoin.

"Then you'd cable Bill—Prince Bahadur Bill—to send on your money, and you'll split it and hook it in various directions, hey?"

"Yes sir."

"What was the job going to be worth to you all?"

Santoin hesitated.

"Come on, the truth, you hyena!" said Mr. Brass tensely.

Still Santoin hesitated.

"Break his arm, Sing," said Mr. Brass coolly.

"No, no—pas du tout!" observed Santoin hastily. "The recompense was to be two hundred thousand pounds!"

"Hey!" Mr. Brass was startled at the amount—for a moment only. Then he smiled blandly—like a large bear that has just found a bee's nest overflowing with honey.

"Write it off as a total loss, Santoin," he said. "And tell me—Clanister is one of you, aint he?"

"But certainly," said Monsieur Santoin.

The Honorable John glanced at the clock. "When do they start?"

"At half-past two."

Mr. Brass asked one or two more questions, then said, "Good! That's all for the present." He beamed. "Tie him up, Sing. Legs, hands, arms and mouth. Pass the whisky, Squire. Your good health, Mirza."

TEN minutes later a very silent but extremely formidable procession of four persons of various hues, including well-fed red, dark black and pale egg-yolk yellow, issued forth from the Honorable John's bedroom and headed, in complete silence, down the corridor—Mr. Brass, Colonel Clumber, Mirza Khan and Sing, all armed to the point of hideousness.

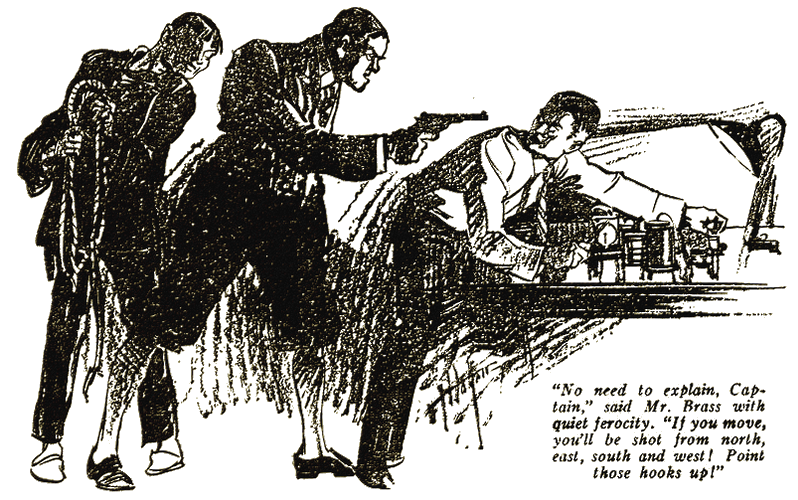

They stopped first at the room occupied by M. Santoin's notion of a private detective, Captain Clanister. The Honorable John tapped lightly on the door. Somebody inside coughed hackingly but briefly. Mr. Brass opened the well-oiled door and entered.

Captain Clanister, in his shirt-sleeves raised his sleek head from an instrument of highly electrical appearance on a table before him—and his jaw fell at sight of the gaping muzzles of the personal artillery of his callers.

"No need to explain, Captain," said Mr. Brass with quiet ferocity. "If you move, you'll be shot from north, south, east and west! Point those clever hooks up to the second floor—quick!"

The Captain conceded the point with considerable speed.

"Good. Tie him up, Sing, my lad! Arms, hands, legs and mouth—as the fashion is tonight."

Five minutes later, leaving a plain bundle where they had found a smart young fellow, they were tapping discreetly at the door of that aristocratic old gentleman Colonel Sir George Standrishe.

But it was a vastly different-seeming old gentleman who faced them as they entered in response to his low cough. Colonel Standrishe, save for a certain snakishness in his ancient eyes, was an admirable specimen of the old soldier who has spent most of his life in India—quite a handsome old fellow, in fact.

BUT the person who faced the Brass battery now was very unlike old Colonel Standrishe. Indeed, he looked much more like an old, old Moslem rajah—so much more, that Mirza Khan uttered an exclamation of amazement tinged with superstitious terror.

"Don't start anything rough, Colonel Standrishe," suggested Mr. Brass. "Bones at your age are brittle, you old scoundrel."

The man was so staggered that he made no resistance at all to the attentions of Sing. Carefully, and not too roughly, the Chinaman corded him up.

Mr. Brass looked at him curiously.

"Yes. He's done it well. He certainly looks like something that has escaped from a thirty years' occupation of a vault. He's got a gray kind of look. I suppose a ghost would have that. Is he really like the Rajah's father, Mirza?"

There was no mistaking the sincerity in Mirza Khan's voice as he replied:

"Sar, it is appalling resemblance. At first glance, heart stood still in mouth! I am brave man,—in favorable circumstances,—but confess hair erected self on head att sight off gentleman in question. Own personal eyes advised brain, 'Here iss spirit of old Rajah arisen again!' Common-sense stated otherwise—haha! Iff Colonel appeared in present fashion to me at middle off night, I confess should state privately to self, 'Here is perfectly genuine phantom of old master,' and should crawl! under bed. Oah, yess... Veree nasty cunning old gentleman, thiss man, sars."

"Humph! Well, he's safe enough now, at any rate," said Mr. Brass. "And now for the lady."

Because, like the others, she was expecting Santoin's signal, she proved no more difficult to capture than her confederates.

She was standing at her dressing-table, and she no longer looked like the smart, up-to-date little Miss Beryl Standrishe who was so popular among the shooting-party at the Castle. Instead, she looked exactly like the young and lovely little Queen of Jolapore she was about to impersonate—that never-forgotten little ranee who had been the Rajah's first wife and the only woman he had really loved.

"Oah!" said Mirza Khan, as the passionless Sing tied her up like the others. "Oah, there is something moast painful in this matter. She iss soa exactlee like little royal lady I served in past years!"

He stared at the woman.

"Oah, I am what you call veree sentimental—but she brings back to me all my youth, and thee brave old days in Jolapore!" he cried. "My little royal mistress whom I served veree faithfully—dead so many years ago and thee gallant youth of His Highness and thee honorable youth off Mirza Khan dead with her. Oah, I am ashamed man—"

A harsh voice cut into Mirza's dream like a hot knife into cold butter.

"Well, what are you going to do about it, Mirza?" demanded Mr. Brass. "The past was fine—devil a doubt of it—it always was. But we're dealing with the present—hey? It's time to go to the Rajah and explain."

And that is what he and Mirza did—leaving Colonel Clumber and Sing to collect the prisoners into one bunch ready to parade before the Rajah.

THIS adventure, the Honorable John always maintained, had probably the oddest finish of any one of his many adventures. For he and Mirza, hastening to the Rajah's bedroom, found him wide awake, yet strangely unable to move hand or foot. Santoin had contrived to see to it that he should be drugged by some subtle, evil and obscure drug that, for a little space, could rigidly enlock his muscular system into a paralysis so deadly that it deprived him of the power to move but yet did not affect his mentality.

A superstitious, nerve-ridden man under the influence of such a drug could gaze upon apparitions in the dim light of his bedroom, believe them to be real, and finding himself unable to move, consider himself the victim of their influence while they were present.

He could lie there and hear their voices when they were not present—but, even if he were in a condition to suspect trickery, he could not rise to prove it.

That, thanks to the sinister talents of Monsieur Santoin, of the man Clanister, and of Beryl and Colonel Standrishe, was what had happened. Heavily bribed by that far-off prince Bahadur Bhil, the quartet had almost succeeded in scaring the most superstitious ruler in India off the throne which Bahadur Bhil would occupy. The immense revenues of Jolapore would have made it almost ludicrously cheap at two hundred thousand pounds.

MR. BRASS paraded his captives before the motionless man on the royal bed.

For a long time, a very long time, his hot eyes surveyed them in silence, clinging chiefly to the impersonation of the dead queen.

Presently he spoke: "The voices I heard in the darkness were yours. The figures I have seen appear in the night were yours. If your speech had been incorrect,—your vernacular faulty,—I should have known. If your dress had been wrong in any particular, I should have seen that. Yet, I saw nothing. How does it happen that you, Colonel Standrishe, are so familiar with the speech and dress of my dead grandfather—and you, Miss Standrishe, with the voice and little gestures, mannerisms, and favorite dresses of—my wife?"

He could not move as he asked his questions. Neither Colonel Standrishe nor his niece would speak. Clever and dangerous crooks, they clung to the refuge of stubborn silence.

It was Mirza Khan who explained—or rather, began to explain, for the Rajah guessed an instant after Mirza began.

"In the old days, Your Highness, this man Standrishe was given post as master of horse under His Highness your father's father. His name then was Cartrall. I was young then but I remember veree well—"

"Enough, Mirza Khan. Now I too remember." The Rajah's eyes glowed.

"He could speak our tongue like one of us. And he knew us. He had trained the woman, as he only of all the English could train her, to be like my wife and to appear to me as the spirit of the ranee! Bahadur Bhil has bribed them to play upon my—superstition. Very good. There is no more to say. The other man—Clanister—is—"

"Oh, just a superior mechanic to arrange the voices by means of some telephonic device from his room to yours, Rajah!" explained Mr. Brass.

"And Santoin—"

"Iss merelee ordinary traitor—snake off thee grass, Highness," put in Mirza Khan.

"Exactly," said the motionless prince, and thought for five long, rather tense seconds.

Then he spoke:

"It is well for you—ghouls, soulless were-wolves that you are—that you do not stand before me in my palace at Jolapore, for I would have my elephants tear you to red rags, stamp you into the dust under their feet till you were less than the dust they trod!"

His eyes gleamed like jewels, on the woman—then dimmed.

"Or, it may be, because in spite of your evil intent, you have enabled me to recapture for a few moments an echo of the past —to hug a mirage to my heart—I might have spared you, vultures as you are!"

His eyes turned to Mr. Brass—and his head moved. The strength of the drug was dying. "Hai!" said the Rajah. "Mirza Khan! Send by the cable to the man of whom we speak in this land as Oyoub—this message —'The jewel is false and wholly without value.'"

Mirza started, stared.

"Your Highness—" he stammered.

"Send it, Mirza Khan!"

The Rajah writhed—sat up.

"And these! What am I to do with these canaille, Mr. Brass?"

The Honorable John's genial laugh came like the sound of a roller breaking on the beach—steady, balanced, sane, unchanging.

"Why, Rajah, in this country we usually throw them out. But as one's a lady and the other is an old man, we shouldn't be out-of-the-way rough about it!"

"No?" said the Rajah. "Very well. Let them go back to their rooms. In the morning let them be fed, then taken to the railway station and left there to do as they desire."

"Including thee man Santoin, Your Highness?" demanded Mirza.

"Naturally, Mirza Khan," said the Rajah. So they cleared the room.

BUT Mr. Brass, his partner and Mirza Khan returned by request—for the Rajah had something to say. He made it short. "All my life, my friends," he said to the partners, "I have roweled myself with the spur of superstition. That spur was of base metal and it has now rusted away."

He drew from a gold box before him a great carved diamond—a colossal thing that blazed and burned with a hundred darting, prismatic fires under the electric light.

"This is the thing we have called the Fortunate Eye of the Kingdom through centuries of superstition, Brass. I am no longer superstitious, and therefore I have no longer any desire to keep a symbol, an emblem of superstition. Intrinsically—in spite of the carving—it must be worth fifty thousand pounds! Take it!"

"Thank you," said Mr. Brass, taking it.

IT was later that the old adventurer observed to Mirza Khan: "I hope this good-looking stone is not the jewel the Rajah spoke of in that cable as worthless, Hey?"

Mirza shook his head, but for once he did not smile.

"No sar," he whispered. "This jewel is worth to each of us partakers possible twentee thousand pounds each, gentleman. But jewel mentioned in cable was subtle method of referring to the Prince Bahadur Bhil!"

"Bill!" echoed Mr. Brass.

"Yess sars. Result of that cable will be serious for that royal gentleman. Within space of four days he will be victim of fatal accident. Matter off politics and secret treachery. Also well-deserved fate!"

But the Honorable John and his partner only smiled, evidently believing Mirza Khan to be quite wrong about that.

In a way they were right about Mirza being wrong.

It was five days later—not four, as Mirza had prophesied—that the newspapers announced briefly that the Prince Bahadur Bhil of Jolapore had been killed in the course of a tiger-hunt on foot—a practice against which he had frequently been warned by his best friends, including his father the Rajah.

It was startling news—but not startling enough to interrupt certain successful negotiations which Mr. Brass was then conducting with a famous diamond-buyer. For the Honorable John was ever a man of balance—one, so to put it, who would always be able to look Justice square in the eyes without quailing.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.