RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, August 1922, with "The Beautiful Ostrich"

An engrossing little adventure in rascality, narrated by the talented author of "Winsome Winnie" and many other deservedly popular stories.

THE Honorable John Brass put down the letter from the income-tax expert whom the sharp-set attentions of the revenue representatives had driven him and his partner Colonel Clumber to employ, and gloomily poured himself another glass of liqueur brandy.

"This country is going to the garbage-hounds—if it hasn't already gone," he said. "This income-tax sharp says we can't get out of it with less, and hints that if it hadn't have been for him, it would have been a whole lot more. In fact, things have got into such a state in this country under this Government that even an expert can't get you out of having to pay your income tax. That's it, squire—we've got to pay up and look pleasant."

The Colonel hunched his shoulders, like a walrus imitating a Frenchman.

"I'll do my half of the paying—because I've got to," he growled. "But I'm damned if I try to look pleasant!"

"That's all right. I'll look pleasant for both of us," said John with a blood-freezing glance at the letter.

The Colonel eyed his partner with a species of morose interest.

"Well, all I can say is that if that's what you call looking pleasant, you are no Apollinaris—no Greek god, no, by Gad!" he stated with a rather surly chuckle. "You look about as pleasant as a pawnbroker at a bazaar, ha-ha!"

But the Honorable John had no intention of allowing his partner to work off his grouch upon him.

"That's all right, squire," he said. "It's what I expected. No man who takes a hand in this income-tax game can bank on drawing anything better than a busted flush—if that. Better men than us have had the hides scraped off 'em by these revenue operators once they got their skinning-knives geared up for business!"

He stared dourly at the fatal letter.

"I'm thinking whether we can't get this good money back some way or other."

HE strolled across to the window, staring out at the drizzle-veiled park in which the mansion was set. Viewed in sunlight the place would have been charming, but studied from a comfortable room, after lunch, it was not very inviting.

"The owner of this shooting was no bad judge when he drew down our good money and beat it to winter in California," grumbled the Honorable John. "We've been here two days, and it's rained all the time. A man wants to be some kind of frog or water-lizard to enjoy shooting in this climate. And—who might this be!"

"Hey?"

"Somebody coming up the drive. Goodish car. Visitors. Looks like a lady inside. Better see her, I suppose. Can't very well turn down a dame making a neighborly call, hey? On the young side, too—if my eyes don't tell me a lie."

"Hey, what's that? Young lady calling! Let me have a look. May be some friend of mine." The Colonel came to the window, as a very good-looking car ran to a standstill before the doorway.

"Good car—late model, six-cylinder Slyder four-seater," murmured John.

The eyes of the partners were on the door of the car. A dainty foot incased in patent»leather shoes, followed by an even daintier ankle, made itself apparent. The partners nodded approval.

"Very neat—very pretty," said John absently. "Now, that's my idea of an afternoon caller."

"Some queen, certainly," admitted the Colonel, smoothing his hand over his harsh, wiry and perfectly unsmoothable hair.

Duly announced by Parcher, the crimson-visaged butler rented with the establishment, she proved to be a very tall, shapely brunette, extremely well got up, still young (though much too old for boarding-school), very self-possessed, slightly worldly. Upon her card were engraved the words "Madame Undine de Nil"—her name, evidently, though the Honorable John blinked slightly at it.

"French name—meaning literally 'Undone by nothing'—whatever that means, if anything. Confident sort of name—'Defeated by nobody,' in English, eh? Well, who wants to defeat her. This is an afternoon call, not a war."

Certainly Madame de Nil did not belie John's extraordinarily free rendering of her name. She was confident—and charming, also English, in spite of her name.

"Oh no, this is not a neighborly afternoon call," she exclaimed smilingly, after the two old rascals had made her comfortable. "It would be so nice to be neighbors—but I have come all the way from Southampton to see you."

She caused her wonderful eyes to shine upon them, threw back her furs and favored them with a glimpse of a beautifully molded neck and throat. "It is a business call—though it seems almost wrong to introduce business after so charming a reception as you have given me." (Parcher was even then placing wine, fruit, sweets, liqueurs, cakes, everything that the Honorable John's far-flung experience and the resources of the establishment could produce to please and fortify a beautiful lady after a long motor run on a wet day.)

"Well, why bother to introduce it, Madame Undine?" said the Colonel, smiling like an old bear who had just found a nest of wild honey.

"Alas, I must," declared Madame anxiously, as she accepted a glass of green Chartreuse from John—to sustain her, he advised, until tea was ready. "For, you see, I have come to ask a very great favor."

The partners smiled noncommittally.

"Well, then, suppose we get the business part over," suggested the Honorable John in fatherly fashion. "It oughtn't to take us very long to make up our minds to do you a favor, my dear child."

The dear child's eyes danced.

"I hoped you would talk like that," she said. "I will explain."

The Honorable John stayed her just long enough to give butler Parcher instructions to Sing that Madame's chauffeur was to be given tea, and treated thoroughly well—even as though he were Sing's own favorite son. Then they settled down to listen to the striking Undine's tale.

IT was quite short, and the request she had come to make was extremely simple. Her husband desired to sublease Harrowall House and the shooting from the partners. Indeed, it was only because of a mistake in the addressing of an envelope that Monsieur de Nil had not taken the shooting before the partners had decided upon it and booked it. She explained that both she and her husband loved that part of the country and had looked forward all the year to coming there. It was not entirely for the shooting, that they wished to come. As proof of that, Madame offered to exchange the shooting they had actually taken—a much better one than the Harrowall shooting—and pay a fair sum in addition for the exchange.

The lady explained all this at some length and with considerable eloquence, even fervor. She excused the fervor by stating that her husband was ill, and being a highly strung man, would fret himself worse if he were disappointed.

"It is, I know, very much—too much—to ask," she declared, permitting a slight tremor to afflict her voice. "And I should not dream of asking you to give up your shooting if I were not able to offer you the Highdown—a very much better shooting—in exchange. You agree that the Highdown shoot is better than this, don't you? And the district is not so remote and lonely as this!"

The partners—who knew the Highdown shoot—agreed readily that it was like exchanging a bushel of decomposed Russian rubles for one good United States dollar or thereabouts, and this fact, coupled with the beautiful Undine's undeniable charm, seemed to settle the matter as far as the gallant Colonel was concerned—or so his expression seemed to say.

But oddly enough, there was apparent upon the Honorable John's good-humored visage no indication of any frantic haste to comply with the lovely lady's request. He was, like his partner, a very susceptible man where fair ladies were concerned—but he was also prone to blink at any offer of something for nothing. The lady was offering a very fine, even famous, shoot in exchange for a moderately good one. Why?

In his very varied experience few strangers had ever traveled a considerable distance on a wet day to offer him a handsome present. It was not a habit of strangers—or of friends. He didn't do that sort of thing himself—and he didn't expect other people to do it for him. No, pretty, worldly women like Undine de Nil did not need to give something for nothing—they were more accustomed to giving nothing for something, and John was well aware of the fact. He was not comfortable in his mind about this offer—he smelled (as he expressed himself later to his partner) a large and odoriferous rodent lurking somewhere; he felt that there was a string tied to this generous offer of the lovely Undine, that an Ethiopian was carefully concealing within the wood-pile.

So he broke it to her gently—taking a half-hour at least to do so—that he and his partner would think the matter over and write to her within the course of the next two days.

He did it so kindly that the gracious Undine apparently took it for granted that, when they had inspected the Highdown shooting, for which purpose she presumed they stipulated the two days' grace, her point was practically gained. So, diffusing much sweetness and speeding up her output of charm to really remarkable proportions, she thanked them, and leaving her address, departed.

"WELL, you didn't exactly hurl yourself at her with an acceptance, did you? We deserve to lose the Highdown shoot," grumbled the Colonel.

"We shall never have it, squire," said John.

"What d'you mean? D'you mean you're going to refuse the offer?"

"Unless I can find out within a couple of days why they want to live here for the next month or so, I do."

"Why, she told you, didn't she? Her husband's got a fancy for this place—and he aint well and he's worrying. That's plain enough, isn't it?" growled the Colonel.

But the Honorable John smiled dreamily.

"Did you ever know a pretty, dashing young lady like Undine have a husband who didn't worry—and mostly felt not quite well? I guess I'd worry if she was my wife, yes sir.... Besides, I've got a hunch that there's something smooth in this business. I'm going to worry it, like the dog did the cat in the house that little Jack Horner built."

"Oh, as you wish—as long as you don't worry me with it," said the Colonel who had learned to respect those queer sudden inspirations which his partner commonly referred to as hunches.

"Meantime," he continued, pressing the bell, "Parcher can clear all this ladies' stuff away—fancy eating sugar cakes at this hour of the day! Beautiful ostriches; that's what women are—beautiful ostriches. We'll have a couple to clear our heads. I've got some pretty solid thinking before me, thanks to that—beautiful ostrich. Besides, we haven't discussed dinner with Sing yet. Parcher, send Sing up, and we'll have an understanding about the partridges ŕ la Pompadour for dinner tonight. I can see this is going to be a busy afternoon for me, squire," he concluded; and taking a cigar, he poured himself a brimmer, and settled back in his armchair to work.

THE movements and methods of the Honorable John Brass, when under the influence of a hunch, were usually mysterious, apparently meaningless and extremely hard to follow. Indeed, during the rainy week which succeeded the visit of Madame de Nil, his partner the Colonel made no effort at all to follow the devious workings of the good-humored pirate's mind. They inspected the Highdown shoot, near Winchester, and saw that it was good, but there Colonel Clumber's interest ceased, and it was entirely without curiosity that be saw John send Sing the Chink, mounted upon a big motorcycle, to Southampton, and other places, and it was with no emotion except deep sullenness that he acquiesced in the sending of a letter to the fair Undine containing a polite but unmistakable refusal to sublet Harrowall House and its shooting.

Rather to the Colonel's surprise, the De Nils made no further attempt to persuade them to agree to the exchange. Neither the "beautiful ostrich" nor her husband answered the Honorable John's letter.

"Huh, they soon gave up," be said, over the breakfast-table a few days later.

Before replying, the Honorable John, his eyes solemnly fixed on his partner, carefully concluded the mastication of a generous mouthful of sole ŕ la Salisbury—a fascinating compound involving the use of lobster-shells, which same are filled with lobster and sole forcemeat and a rich velouté sauce, with a folded fillet of sole on each, the whole dressed on a border of rice and generously garnished with little mushrooms.

"That's all right, squire," he said. "They've given up nothing, believe me."

"No—it's us that have given up something—one of the best mixed shoots in the south," agreed the Colonel sardonically.

"Well, well, maybe we have. Maybe the old man has made a mistake this time," said John with an insincere humility, "—and maybe he hasn't."

The Colonel missed the insincerity, and placated a little by the humility, let his partner down lightly—for him.

"Oh, well—every man has got a right to make a damn fool of himself occasionally," he conceded. "I've come near doing it myself in my time—many years ago."

John chuckled, ignoring all the obvious repartees.

"You seem very well satisfied about it!" observed his partner rather stiffly.

"Squire," returned the Honorable John, "I am. Fill me that cup, Sing, my lad. Your sole Salisbury was fair to middling. Just let me have a look—only a glance, son—at that game-pie, will you?"

IT was not till some hours later when the partners were returning from a casual stroll with their guns, that the Honorable John asked his partner if he had heard the airplane buzzing about in the night.

"Airplane?" snorted the Colonel. "I heard no airplane—and I'm a light sleeper, too."

"There was one," said John.

The Colonel laughed.

"If there was, I should have heard it," he said. "What does it matter? What's an airplane, anyway?"

John beckoned a farmhand who, probably having been awakened by the sound of their voices, appeared to be doing something to a gate close by.

"Did you hear an airplane in the night, old man?" he asked.

The rustic had—and said so.

"Sounded to me as how he pitched somewhere handy. My missus heard um too, and tould me to get up and go and see if I could see um. But, 'No fear,' I says to her, 'I got summat better to do than to go sloppin' and dodgerin' about the fields huntin' for flyin' machines this time o' night,' I says. But there sartainly was one of um flyin' about—pitched on the ground somewhere nigh-abouts, seemingly."

The man was right.

A little farther on they met another laborer, actively employed in looking at a rabbit-hole, who informed them that an airplane had "pitched" in the long meadow down by the railway arch.

"We've got to pass the arch on our way back," said John. "We'll have a look at his tracks."

THIS they did. They found the tracks easily enough in the softish surface of a long, flat pasture bounded by the railway which cut through the estate.

"Hum! He chose the best landing-place on the estate," said John. "Had no trouble at all."

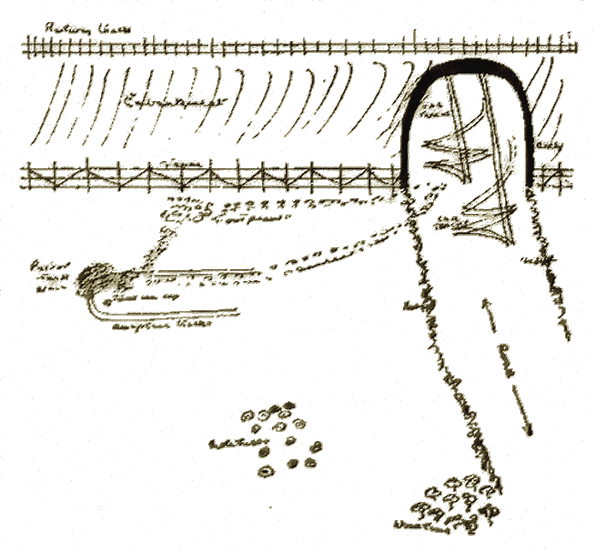

The Honorable John was studying the track of the wheels—a long track where the airman had landed, a short bend, and the track where he had taken off again—like a narrow staple or U.

Close by was the railway arch where the line crossed a farm road. John moved about studying the tracks of the airplane, certain foot-prints, and a petrol-soaked patch of turf. Following his studies, he moved farther and farther away from the impatient Colonel until he came to a stop under the arch, where he paused, staring at the ground thoughtfully.

"Yes, it's an ordinary everyday farm road—covered with ordinary everyday mud," said the Colonel. "Come on along to lunch."

"Certainly—certainly," agreed the Honorable John, but made no move.

"What are you staring at? It's only mud—ordinary mud."

John looked at his partner, his greenish-gray eyes blank with thought.

"What d'you make of those tracks—and footprints, squire?" he asked, pointing to certain motor-tire tracks under the arch.

"Nothing," said the Colonel promptly. "Nothing—before lunch. After lunch I could write you a novel about 'em—perhaps," be added jocularly. "For the Lord's sake, man, cut out this Sherlock stuff on an empty stomach and come to your victuals."

"AH right—you go on. I'll catch you up."

HE kept his word. The Colonel only beat him to the lunch-table by a second—for the Honorable John Brass was a man to whom greyhounds could give nothing away in a straight sprint to lunch. He put up a thoroughly good battle with what Sing had devised for the midday repast, but he was absent-minded throughout, and disappeared shortly afterward.

He turned up an hour later, with the greenish glint in his eyes rather intensified, and while the Colonel dozed, he spent the rest of the afternoon in drawing and studying the following rough map—together with the brass cap of a petrol can.

Next John conned a railway map, nodded with an increasing satisfaction on his face, studied the mail-boat announcements in that day's Times, chuckled, rose and put everything away, except the petrol-can cap.

He commanded refreshment to be set before him—old liqueur variety—and woke his partner.

"Rested after your lunch, squire?" he asked with gentle irony. "I mean, are you rested enough to give your brains a little exercise?"

The Colonel stared.

"I guess my brains can grapple with any problem you can set 'em, old man," he avowed. "What is it?"

John passed him the petrol-can cap.

"Well, what d'you make of that?" he inquired.

The Colonel glanced at him suspiciously.

"Where did you get it?"

"Picked it up in the meadow by the railway arch," said the Honorable John airily. "Does it convey anything to you?"

The Colonel pondered.

"Well, it's been dropped by somebody; that's clear," he said slowly, "—probably by that airman who landed last night. That's it. The chap ran short of petrol and landed to put in a can or two. In the bad light he dropped this. That's it."

"That all?" asked John blandly. "Putting two and two together and taking one thing with another is that all it tells you?"

"What the devil else is there for it to tell me?" snapped the Colonel with a certain irritation. "It's just an ordinary brass cap, isn't it—like forty-five hundred million more. It isn't a gramaphone. It can't tell you or anybody more than one thing, can it? You picked it up, didn't you? Well, the only real information anybody can get out of that is that somebody dropped it. What does it tell you?"

The Honorable John smiled.

"Nothing much, true," he replied dryly. "All it tells me is that tomorrow night at about one o'clock certain folk at Southampton are going to find themselves badly short in their accounts—thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of pounds short."

He stared at the dirty brass cap as though it were a crystal ball and he a crystal-sharp.

"It doesn't tell me much," he continued ironically. "But what it does tell me is that I'm going to do as 1 said about that income tax. I'm going to get it back from the Government, squire—and a double handful for luck."

THE Colonel gazed at his partner with a reluctant admiration in his eyes.

"Yes, you can admire me," said the Honorable John equably. "I've earned it—at least, my natural genius has. I'll admit freely that I've got a wonderful talent for building up on trifles and noticing things. As I've told you before! It's where I'm different from the ordinary damfool squire. Take you, for instance: you saw everything that I saw down by the railway arch yesterday—but it told you nothing. You stared at it, and your mind didn't move half an inch—your brains were kind of sluggish—heavy, like cold rice pudding. But mine—my brains were boiling up like—like—"

"Hot glue," suggested the Colonel.

"Well, it's a poor way of putting it," said the Honorable John, "a very poor way; but it'll do. I saw so much down there, owing to this great gift of mine for noticing details that don't draw a single spark out of any average brains, that I had to jot it down on paper to remember it."

He produced his rough plan. "Take a look at that," he said.

The Colonel did so—stared at it for a moment, turning it about. Then he returned it.

"Looks like a picture of the Crystal Palace going to be struck by lightning," he commented. "Does it mean anything?"

John settled down in his chair.

"It gives among a lot of other things the reason why Undine wanted to exchange shootings," he said. "Now, listen to me and I'll explain: There's a bit of guesswork about it—but it's a good idea to guess while the guessing's good. Pass the brandy; get your brains revolving; and listen to the old man!"

ANY person sufficiently foolish to leave a comfortable bed at about eleven o'clock of the following evening and take a little prowl through the misty, dimly moonlit night to the meadow and railway arch on the Harrowall estate might very possibly have observed that he was not the only prowler in that remote neighborhood.

As the Honorable John had very truly remarked, there had been quite a lot of guessing in the fabric which he had built up on the details he had observed on the previous day, but—the guessing had been good

At eleven o'clock the spot was apparently as deserted as any one of many similar spots in the countryside. Save for a barn-owl fanning himself about on silent wings, a few rabbits feeding, and a fox watching the rabbits from a clump of bushes, the place was deserted.

But at five minutes past eleven a little group of shadows made its appearance at the edge of the woodland on the side of the meadow farthest from the railway line. The four figures comprising this group moved very silently, and in the curious shifting light might have been no more than dense wisps of mist. But the fox watching the rabbits knew better. One swift glance over his shoulder as he left, assured him that the newcomers were one burly man of yellowish complexion (Sing the Chink), one burlier man (this was Bloom, the Colonel's valet) and two burliest men, namely the Honorable John and his partner.

They halted in the right angle formed where the woodland joined the hedge of the farm road, and John took a long and careful scrutiny of the meadow. It lay still and empty under the mist.

"Nobody here yet," said he, glancing at the illuminated dial of his wrist-watcb. "But we'd better get busy."

He turned to his partner.

"You and Bloom get down to the railway arch, old man. Keep well in the shadows. I expect a motor to come up there before long. You know what to do. Disable it temporarily—to take out the distributor-brush will do—then creep back up to us under the hedge. All clear? Good."

Two of the shadows moved swiftly down the farm road in the direction of the arch. They were lost to sight in the mist almost immediately.

The Honorable John scanned the meadow again.

"I think that patch of molehills out there will make good enough cover for us in this mist and this light, Sing. Come on. Curl up small—compress yourself a bit, in fact—when you get there, and then just lie quiet, wait for orders, and pray to Confuschia that an airplane doesn't land on you. Got your wire-cutters and things? Come on, then. And don't forget that one or two of these folk have got to be caught at all costs! And two or more must escape!"

They moved out to the meadow silently, toward a spot where a number of big molehills showed dimly. Here, among these, they curled up.

Silence settled down again. Five—ten—fifteen minutes passed. Then suddenly John, hunched up among the molehills, stirred slightly.

"Listen, Sing! Hear anything, hey?"

A very faint, low, remote humming had made itself apparent.

"Here he comes, Sing—quiet now. Don't crane up like that—you can't see him. Lie still and double up. Ha! Here are his pals!"

Sliding very silently, with its electric lamps dimmed, a motorcar came stealing along the lonely farm road. It stopped under the arch, and its lights went out. The Honorable John, straining his eyes, fancied he saw two figures enter the meadow by the arch and go gliding soundlessly along by the fence at the foot of the embankment.

The deep hum of the invisible airplane was very plain now. It seemed to be heading upon a course which would take it straight overhead.

The watchers waited silently.

Two ghostly rays appeared in the meadow somewhere near the old tracks of the airplane—a green and a red. These came from two powerful masked electric torches and were pointed straight up to the sky by the people who bad come in the car.

Then abruptly the engine note of the machine overhead died out, yielding to the dry whistle of the air through the wires—and the Honorable John stiffened as a huge shape, like some monstrous and formidable flying-beast of the night, loomed into view gliding down to the meadow. Beautifully driven, it took the ground almost without a jar, taxied along a little and came to rest some distance from the watchers. It looked huge in the curious shifting light.

LOW voices sounded for an instant through the mist, then died out toward the embankment. The Chinaman, crouching low, and his owner, crouching as low as his figure permitted him, crept forward toward the machine, peering through the mist, listening tensely at every step.

"All right—they're all at the embankment—get busy—quick, quick, you heathen!" whispered John as they stole under the wide wings of the machine.

Followed a series of very soft sounds—as it might be the noise of one who slowly, with infinite caution, cuts copper petrol-pipes and high-tension cables with a pair of wire-cutters.

Presently, within a space of minutes, the two figures stole back to the mole-heaps, and from thence to the angle of the hedge and the woodland.

The Colonel and Bloom were already there.

"All right," murmured the ex-peer. "Good, good! Now wait." The Honorable John peered at his watch.

"The mail is due through at eleven-fifty-two," he said. "She probably slows here for the section that's being repaired a quarter-mile on round the bend. She's due in a minute—and she's on time, too! Hark!"

The distant roar of an express came to them through the night as they listened, increasing swiftly. A dull glare swung into view, sweeping along the track—the mist-dimmed light of the many windows.

Even as the Honorable John had prophesied, the express slowed as she ran parallel with the meadow. But in less than two minutes she was past, and the noise of her was dying out southward.

The watchers craned forward like bloodhounds, but the Honorable John restrained them—mainly with whispered insults.

"Give 'em time—time!" was the burden of his low-voiced exhortations.

The minutes stole past—five—ten, then a little thud sounded from the direction of the arch—a soft padding of running footsteps—more thuds from the airplane—and a muttering of voices.

"Wait—I say—wait," hissed John.

Then, quite suddenly, a bitter imprecation shot through the mist.

"Shell never start—something's wrong—leaking badly—put the stuff all in the car—quick!" came a voice with a French accent.

More footsteps thudded softly, dying out toward the car under the arch. Almost immediately the rushing sound of a self-starter surged through the mist. But it was not followed by any engine sound.

"Now, my sons," said the Honorable John, and galloped furiously down toward the arch, followed by his band. "Mind, we must get one of 'em, more if we can."

They came upon four startled people by the motor like a quartet of thunderbolts.

"Here they are, my lads," shouted John, and hurled himself at the nearest. It proved to be none other than the fair Undine, dressed in breeches and riding-coat. Without an instant's hesitation she clawed the Honorable John down the plump cheeks like a wildcat. Startled, John loosened his grip for a second—and Undine squirmed eelishly away from him and vanished in the mist.

"The—long-clawed ostrich!" he ejaculated, turning to the others.

They had had better luck.

Bloom had lost his man, and had narrowly escaped a dislocated Adam's apple; but Sing and the Colonel had rushed their prisoners well away and out of sight of the car and were sitting comfortably astride of them.

"Got 'em? Good work! Tie their wrists and run 'em up to the house," commanded the Honorable John. "You and Bloom, Sing."

And this they did.

Even as the prisoners disappeared with their escort, the Honorable John was peering into the back of the car, what time the Colonel replaced the distributor brush, by the removal of which he had temporarily crippled the engine.

"Well, here they are, old man," he said softly. "It was a good big grab. Six boxes. Gold—their confederate in that train must have been as strong as a horse and as quick as a cat to have shot those boxes out in the time the train took to run past the meadow. Nip in! Good!"

The Honorable John started the engine and slung the car round with a jerk. He switched on his lamps, and they started—in the alleged pursuit of the two missing people.

But they did not find them.

IT was considerably more than an hour later when the partners returned to Harrowall House. And oddly enough, they came not in the Slyder car which they had captured, but in their own touring-car, with Sing at the wheel.

Even as nobody had seen or heard Sing go out to meet them, so nobody saw or heard them return, for with the exception of butler Parcher (very sleepy) and Mr. Bloom, guarding the prisoners, the rest of the servants were deeply asleep (thanks, no doubt, to the effects of what Sing, who had attended to that matter on the previous evening, naively called "dopee—make sleepee").

Nor did any save the partners and Sing ever know that with the trio there came into the house four heavy boxes of bullion—good gold, which was safely bestowed away before they had been in the house ten minutes.

Then, and not till then, did the Honorable John (being, he claimed, a law-abiding man) send for the police—who came from the nearest town, with great speed, for already the telephone had been busy.

A mail-train, carrying a very large consignment of gold for America, for shipping aboard the Adriania, had arrived at Southampton precisely six boxes of bullion short. These boxes, together with one of its guardians, had mysteriously disappeared en route from London.

He was a very quick, very shrewd and experienced man, the Inspector in charge of the bevy of police, and he complimented the Honorable John three times on his smartness in working out the planned robbery from such slender clues. He might have complimented him some more, but time was limited. He interviewed the prisoners, two capable-looking but hard-faced gentlemen of middle age who stated they could not speak a word of any language but French, and who, in that tongue, volubly swore that they knew nothing of any planned robbery, but were simply employed as chauffeur and mechanic by M. de Nil—an enthusiastic amateur aviator—and his wife, a keen motorist.

The Inspector forwarded them to Salisbury for safe custody while he set off to trail the De Nils.

He did not find them. But he found their car, half in, half out of the river, a mile or so from Harrowall House, and from its position he easily and fluently reconstructed what had happened.

"See?" he said to the Honorable John and Colonel Clumber. "The two De Nils made off from under the railway arch in their car, while you were tackling the other two—"

"Yes, that's right," nodded John.

"With the boxes of gold behind. They probably traveled very fast, overran the road at this bend and skidded into the river. They grabbed all the gold they could carry—or perhaps buried all they had time to—and disappeared, leaving what they couldn't take."

He was rummaging in the tilted back of the car.

"Yes," he said, "I'm right. There are two boxes here left in the car.... That's what happened."

"You make it as plain as print, Inspector," said the Honorable John.

"Well, that's my job," explained the Inspector. "Now we've got to catch these De Nils. When we get them, we get the rest of the gold."

"Yes, yes," said John, wagging his head, "surely so—surely so."

BUT neither the Inspector nor anyone else ever got the beautiful ostrich or her husband. And it follows that the gold was never discovered—at least not until some time later, when the shooting tenancy expired and the Brass-Clumber combine discovered it where they had hidden it, and carted it back to London, there to be judiciously disposed of.

But it was only with great difficulty that the Colonel could bring himself to believe that it was by anything but sheer luck that his partner had got wise to the De Nils' intended exploit.

And it was wholly in vain that the Honorable John, adopting the methods of Sherlock Holmes (of whom he was a great admirer) explained in detail how he had wormed it out—thus:

"The airplane tracks, the petrol stain, the petrol cap and the double track and double marks where the car had reversed twice told me that the car and airplane had been there at the same time and that the car had fetched petrol for the 'plane. I found out that De Nil had knocked 'em up at Smith's garage in the village at midnight and bought twenty gallons. Smith described them as a good-looking woman and a man with a pointed red beard. Sing had seen the De Nils at Southampton when I sent him there for that purpose, and recognized the description—and I recognized her. The footprints along the embankment fence told me that they were interested in some way in the railway line. I knew already they wanted the run of the place and were willing to give Highdown for it. I inspected Highdown and found it was bounded by the same line—but was not so lonely as this place. Also, the train does not slow down past Highdown. It was while I was wondering what they were driving at that I saw a paragraph in the paper saying that a big installment of gold off the American debt was being shipped by the Adriania—and that did the trick. I looked up a few timetables and things, and I wormed it out that their idea was to get the loot well away by airplane, probably across the Channel, by dawn, having the car in support—you may say, in case of accident. The visit to the meadow the first night was a sort of rehearsal—to see if the airplane could maneuver well enough in the meadow. That," concluded the Honorable John impressively, "was where they made their little error. They thought that the tracks would not be noticed—or if they were, that they would tell nothing. They weren't far wrong, either—if they had had to deal with ordinary people. But they had to deal with a man with a gift—me, in fact. Why, squire, I don't mind saying that I read those tracks like an open book of poetry. The De Nils reckoned the tracks were details—but they didn't know that I eat details alive. No, squire—you can take it from me that it was a bit of good work—by me, the old man. And don't forget that whenever you come across a detail, be sure to draw my attention to it—in case it's valuable. Pass the brandy."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.