RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old French calendar cover (1900)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old French calendar cover (1900)

Cassell's, December 1923, with "The Entry of Dragour"

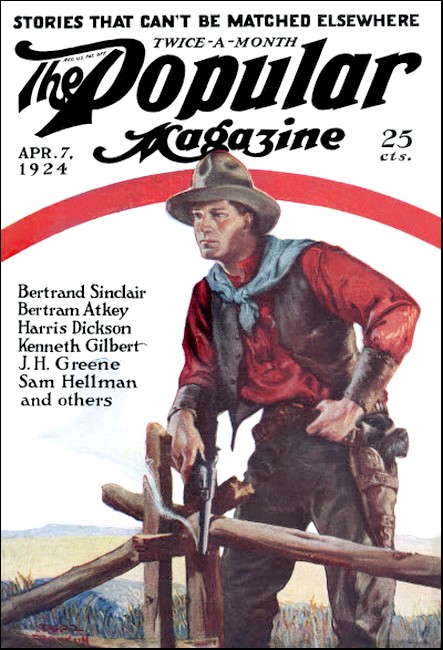

The Popular Magazine, 7 April 1924, with "The Entry of Dragour"

THE big police officer who was slowly making his sunny, afternoon perambulation of Green Square halted for a moment outside the small, retired house in the southwest corner of that quietest of central London squares, glanced up at the open window of the second floor and listened intently.

But it was not in his professional capacity that he listened, though it was an uncommon sound which had brought him to a leisurely standstill—the clear, wild note of a piping bullfinch which was issuing from that upper window like a moving thread of silver wire.

The policeman knitted his brow as he listened, for there was something vaguely familiar about the song of the bird. He was recruited from the countryside and knew the note of a bullfinch—but he had never known a bullfinch sing that air or any air resembling it before.

He waited a few seconds. Then suddenly his square, heavy face cleared and he smiled.

"It's a song—can't remember the name, but I can remember the tune. Mr. Chayne's done well with that bird since I was on this beat last."

He nodded, smiled and moved on, absently whistling, very softly, the first few bars of a song that once was tremendously popular—"Oh, Promise Me!"

That was what the bullfinch had been piping—perhaps the first ten bars—as truly as and more sweetly than any instrument.

The exquisite notes followed the big policeman as, reaching the corner he hesitated a moment, then left the curb and moved to make his way diagonally across the small, tree-planted, railed space in the middle of the square.

This "garden" was empty save for one person, an enormous man, very largely built as well as very fat, who was sitting on a lonely seat set by some discouraged-looking shrubs.

The policeman paused by this man who, sitting perfectly still, was staring straight ahead of him with dull eyes, very black and seeming very small, set in that vast expanse of smooth-shaven face. His complexion was so extremely dark that although one would have hesitated to call him a man of color, few would have confidently described him as a white man.

The policeman moved his hand in a nicely discriminated semisalute.

"Good afternoon, Mr. Dass," he said affably. "Mr. Chayne seems to be doing well with the bullfinch."

The dark, elephantine man turned his lack-luster eyes on the constable. For a moment they were totally devoid of expression—remaining blank with the utter blankness of those of one long habituated to the study of abstruse, remote and intricately complicated problems.

The policeman's smile widened, for the deep trances of Mr. Kotman Dass were no novelty to him. He spoke a little more loudly.

"I say that Mr. Chayne's bullfinch is improving, sir!"

The dark man started violently, staring dully about him like one just reviving from the effects of an anesthetic.

"Eh! Yess—yess! Thee bird, you say. Oh, certainlee, officer—veree perettee!"

He steadied himself, controlled the small fluster into which the sudden appearance and speech of the policeman and his own abrupt return to consciousness of his immediate surroundings had thrown him, and spoke again. This time his English was devoid of that curious, sharply clipped accent with which he had first spoken.

"Ah! Good afternoon, officer. It is some weeks since you patrolled this beat. I was meditating and your sudden appearance startled me. How do you do! It is singularly perfect weather. Yes, Mr. Chayne has worked wonders with the bullfinch. Its note is very sweet."

He raised a huge, shapeless hand.

Across the square, soaring above the hoarse, rough chirpings of the London sparrows gossiping all about them, came the thin, silver note of the bird singing in that top-floor room of No. 10.

"Very pretty, Mr. Dass," said the policeman. "It wants a lot of patience to do that."

Kotman Dass nodded a ponderous head.

"With some of the little wild ones, yes. With others, no. Mr. Salaman Chayne is a man of infinite patience—with bullfinches!"

"I'll be bound he is," said the policeman, and nodded, moving on in the leisurely, measured, irresistible-seeming walk of the police officer the world over.

For a few seconds the dark eyes of the fat man followed the blue-clad figure. If they held any expression at all it was of apprehension.

Mr. Dass took out a blinding orange and emerald silk handkerchief and wiped his immense forehead.

"Jollee good fellows, these London police, yess," he muttered uneasily, "but veree devoid of tact. To approach a gentleman obviouslee lost in thought—engaged in profound reflection—and to address him soa veree abruptlee is not the act off a tactful policeman."

He sighed cavernously, rose and, still holding his brilliant handkerchief, went toward the house of the bullfinch—the house which was the home of Mr. Kotman Dass and his friend and informal partner, Mr. Salaman Slaymore Chayne. He went with slow ponderously dragging steps that grew slower and slower yet, until halfway across the road they ceased, and Mr. Dass stood still, staring blankly ahead—an enormous and unshapely figure, black-clad, with an alpaca coat and a worn black-and-white straw hat, vaguely clerical looking, the blinding handkerchief still dangling from his hand.

Standing in the exact center of the road, he was quite obviously lost in thought.

But this time he muttered to himself, as one recapitulating a matter in his mind might do. He spoke in the odd, clipped, chi-chi which he invariably used when not speaking with a conscious guard on his tongue.

"It iss undoubtedlee logical conclusion thatt there is master mind att work—in supreme control off thee vast bulk off illicit drug traffic. Where there are little veins, there are arteries, where there are arteries there iss a heart. Oah, yess. Twenty-six perfectlee sound deductions prove thatt, I think. I shall convince Mister Chayne—"

A taxicab bustled into the small square—a rare visitor at that hour of the day—and bore down upon the gigantic dreamer.

He did not appear to notice it—staring straight ahead, his lips moving.

The taxi horn hooted like an angry duck.

Mr. Kotman Dass, utterly oblivious, continued to dream.

It is a tacitly accepted rule of the road that both parties to a passing do their share of any swerving necessary. Only thus are accidents avoided. The huge Mr. Dass, fathoms deep in thought, left it to the taxi driver to do both his own and Mr. Dass' share of the swerving. Which that motor bandit did with a violent and raucous spate of very evil talk—just as Mr. Salaman Chayne chanced to put his neat head out of the window, his hot, gray-green eyes instantly photographing the situation.

He leaned out almost dangerously.

"Damn you, Dass, you are obstructing the traffic. Get out of the light, can't you!"

The voice of Mr. Salaman Chayne was acrid, distinct and penetrating. It cleaved through the reveries of Kotman Dass like an arrowhead dipped in acid—and the ponderous one woke up. He moved weightily to the pavement with something in his motion akin to that of a large bullock endeavoring to rise hastily from a recumbent position.

The taxi driver laughed sourly and rattled round the bend.

Mr. Dass glanced up apologetically, made several deprecatory gestures and let himself into the house.

"Oah, yess—a man of infinite patience—with bullfinches only. With me, Mister Chayne is soa hasty always," he muttered. "But he will be veree highlee delighted with thee twenty-six deductions!"

And so laboriously he began to climb the stairs.

THE room to which Kotman Dass successfully transported his astonishing weight was, like many other things in No. 10 Green Square, unexpected.

It was tenanted by birds—uncaged.

There were perhaps as many as fifty, of various species, about the room, which was lined with neat little nesting boxes. There was not a cage in the room. Every bird was free—really free for the big window was widely open. The place was busy with the pretty traffic of the little winged folk, going out or coming in—finches, linnets, sparrows. Robins flickered there and some brilliant blue-tits—busy, peering, inquisitive mites. There were a number of foreign small birds, very ornate, and a pair of wrens had a "desirable detached residence" in a tiny box in a high corner. A number were playing about in a big basin of water sunk in the floor.

For some years Salaman Chayne and Kotman Dass had lived together—upon their wits, or, rather, upon the wits of Mr. Dass and the physical activities of Mr. Chayne—indissolubly partners, in spite of the fact that they were diametrically opposed in almost every conceivable way that matters. But upon one point they were wholly at unity—they loved birds and birds loved them. At least, no bird ever feared either. They were bird men—bird masters, bird slaves.

It was the one gift the two men possessed in common and in like proportion—this wonderful, enviable charm over the little feathered folk, and the passion to exert it.

Out of their general, catholic love for birds developed more particular passions—resolving themselves in the case of Salaman into an intense interest in, and an uncanny mastery of, the art of training the wild bullfinch to pipe man-made airs; and in the case of Kotman Dass into an illimitably patient and eerily successful effort to teach that incorrigible ventriloquist, the starling, something of the English vocabulary. There was rivalry, if not jealousy.

Kotman Dass had a friend—an elderly starling long a permanent boarder of his own free will, who could say "Good morning, Dass," as clearly as any parrot.

But against this Salaman Chayne could now set another practically permanent guest—a bullfinch with a twisted claw whose achievements had so interested the police officer.

To the sanctuary of the upper floor of No. 10 birds came and went or stayed as they listed.

It was to this room that the mountainous Kotman Dass ascended.

Salaman Chayne had just finished the bullfinch's lesson for that day and met his partner on the landing outside the door.

He was lighting a very large and very good cigar, and paused in this operation to state a simple home truth to Dass.

"Some day they will bring your remains home on several lorries, Dass," he said. "What were you dreaming about out in the square? But we will have it downstairs, I think."

"Oah, yess—downstairs assuredlee!" agreed Mr. Dass, turning unwieldily and retreating down the creaking stairs, followed by his partner—and that was as if a squirrel followed a bear.

For Salaman was little and slim and darting like an arrow or a wasp or a lance. Five feet three and steely as a sword blade.

He was probably the neatest, jauntiest, cleanest, most fastidious little man in London and if he had been several sizes larger he might have claimed to be in his clean-cut way one of the best looking, for he was completely and perfectly symmetrical and his thin, hawkish, brown face was well, if boldly, modeled, and illumined by a pair of queer, hot, compelling gray-green eyes with a hint of yellow in them. They were never free from a curious smoldering ferocity. All his movements were neat, quick—except when with the birds—dainty and cat silent. His hair was corn-colored, and he wore a thin, narrow, dagger-shaped beard of the same yellow hue. He carried himself with the fierce easy cockiness of a man conscious of his diminutive size and even more so of the fact that in spite of his size he was far more than averagely competent to take care of himself.

Salaman, among his fellow men, was rather like one of those trim, businesslike, game bantam cocks, in a barnyard full of fat and flustering hens. His cockiness was in his air and carriage more than in his manner which, save when irritated by adverse circumstances or his partner, was that of a near-enough gentleman. It had on occasion come as a surprise to certain of the misguided to learn that the little man carried in each hand a punch which could fan into fairyland most men half as big again as Mr. Chayne; and though his brains were on about the same scale as his body, nevertheless there was room in them for a formidable knowledge of Japanese wrestling. He could cling to a fighting horse as that agile monkey known as the gibbon can cling with one finger to the topmost bough of the old home tree—and, he was a dead shot with most weapons, including his mouth and the dainty sword cane he invariably carried.

He was devoid of illusions concerning his partner whom he treated much as the small precocious son of a mahout may treat a gigantic but humble-minded elephant—or a little quick wife a large slow husband.

To Salaman, Mr. Dass was ever ready to admit that, though English, he indubitably numbered among his ancestors certain "highlee" placed inhabitants of far-off India.

Salaman would agree.

"Yes, Dass. I guessed that on the first occasion I heard you suddenly slip from decent English into a sort of chi-chi. Anybody who ever heard you speak in a moment of haste or excitement would know that. Even your starling says 'Yess' instead of 'Yes.'"

Meekly the colossal Dass would agree.

"I know. I know that it is so, Mister Chayne."'

"Personally I have no objection to your admittedly mysterious and complicated parentage and ancestry, Dass," the hot-eyed Salaman would continue. "Your amazing brains annul and cancel all that. It's not your ancestry that irks me—it's your—"

Kotman would nod his vast head, heavily and slowly.

"Yess, yess, it is my appalling lack off physical courage that discommodes you, Mister Chayne. J know. Thee heart of a fat sheep upon the hillsides—yess. A highlee disgusting coward. Yess, I see thatt, certainlee"—sighing gustily.

It was true. While Kotman Dass possessed a brain which Salaman Chayne sincerely believed practically unparalleled, his personal courage was precisely nil, his habits were untidy and his customs slovenly.

The partnership flourished only because the cold-blooded courage of Salaman was added to the astonishing brain of Kotman Dass. They were to each other what the lock is to the key, the hammer to the anvil, the knife to the fork. There certainly was in Kotman Dass much that Salaman Chayne despised—and said so; and there may have been in Salaman Chayne much that Kotman Dass despised—and carefully did not say so; but both believed that united they might stand and, divided, fall.

Kotman Dass began speaking hastily and propitiatingly before they had reached their favorite sitting room.

"It was veree foolish to linger in thee path of taxicabs, Mister Chayne, I confess thatt. But my mind was busilee occupied with small problem off thee Lady Argrath which you brought to my notice thiss morning."

His tone was changing curiously. He had begun on a nervous apologetic note, but as he proceeded he appeared to gain confidence.

"I have considered thee matters of Lady Argrath; her attitude to her husband, your cousin; and Sir James Argrath's peculiar fluctuations between extremely high spirits and bouts of profound gloom."

Kotman Dass leaned back in his chair and raised a huge hand as though to tick off certain points on his fingers.

"The material which you gave me to consider was as follows," he said. "You advised me that, firstly—"

Salaman Chayne stirred restlessly.

"All right, all right—I know what I told you, Dass. Don't waste time repeating all that over again. What I want from you is not a long account of the way you've churned your brains over the information I gave you. I want your conclusions briefly not a lecture on the art of arriving at conclusions."

Kotman Dass looked reproachfully at his acrid little partner.

"It was veree interesting speculation," he said.

"No doubt—to you. But I am only interested in results."

Kotman Dass nodded resignedly.

"Very well, Mister Chayne. I have arrived by infallible chain of reasoning at thee following conclusions. Lady Argrath is a drug addict, a traitress to her husband, and I think thatt she is trying to lure you into a condition which will render you useful to her for some purpose at present obscure to me—for lack of data."

He was staring absently before him—like a man whose eyes are really looking inward to read his own brain, as clear as a printed sheet inside his skull.

"It is theoretically incontrovertible that she is false as she is beautiful; that she is utterly heartless, completely selfish, unquestionably dangerous. A fierce, cold, and formidable vampire. I shall demonstrate irrefutably to you—from the material you gave me—that she is a liar, that she betrays her husband in many ways, that she will inevitably ruin him and probably you; that she is possessed of a mentality compared with which yours and that of your cousin are the mentalities of two wax dolls; and that logically she must be in league with an evil Force of which I have repeatedly suspected the existence. Of this mysterious and deadly Force I will speak presently, but first I will finish acquainting you with the true nature—as made perfectly apparent by the evidence—of this beautiful vampire in whom you are interesting yourself—"

Mr. Dass broke off suddenly as Salaman leaped to his feet, glaring.

"I have a good mind to give you the damnedest hiding you've ever had in your life, you libelous scoundrel!" he snarled. "You dare to sit there like a—a—an overfed whale and roll out a string of low slanderous untruths like that! Why, I simply can't keep my hands off you!"

Mr. Dass collapsed like a child's air ball touched—in a spirit of curiosity—by her big brother's cigarette end.

He moved his hands hastily, aimlessly; he began to show the yellowish whites of his eyes; his face took on a greenish pallor; he trembled very much and he began to gabble almost meaningless apologies. He was a very frightened man. His English was shattered to fragments.

"Oah, my dear Mister Chayne, but please noticing thatt I speak purelee abstract fashion. That was impersonal intended certainlee—same fashion as professor speaks off microbes."

"Microbes!" roared Salaman Chayne, glaring. "Lady Argrath—"

"Iff you please, noa, noa. She iss not microbes, assuredlee not—it was onlee hurree to explain manner off reference to her I used thatt expression. I—meditated upon lady and reported on same lady in spirit of professor meditating and reporting on veree difficult problem. Personallee she is undoubted veree charming ladee, oah, yess, I readilee agree and apologize thousands times."

He brightened up a little as the glare died out of Salaman's fierce eyes.

"Ten thousand apologies, my dear fellow, Mister Chayne," he gabbled, propitiatingly.

Salaman ignored this offer of apology in bulk, and stared at Mr. Dass over his cigar with something very like uneasiness replacing the fading anger in his eyes.

He had had too many proofs of Kotman Dass' mental abilities to be able to shake off lightly any unpleasing deductions made by that large person from data relating to any one.

Though by no means in love with the beautiful wife of his cousin Sir James Argrath, a well-known company promoter and financier, the wasplike Mr. Chayne undoubtedly was interested in her—so interested indeed that he had seen enough of her and her household to have been puzzled by a number of small matters he had noticed there. These he had carried to the scalpel-minded Mr. Dass—and now Mr. Dass had reported upon them—in the annoying fashion related.

"Of course, you're as wrong about Lady Argrath as it's possible for a man to be. But just what did you mean by an evil Force? Did you mean a man, a ghost, or a devil?" said Salaman, with acid irony after a few moments reflection.

"Oah, a man—but a man with much devil in him also," replied Dass, still eying his partner apprehensively.

"You see, Mister Chayne, I have formed thee conclusion from various facts—they have nothing whatever to do with Lady Argrath, certainlee not—that somewhere concealed behind all thee traffic off the illicit drug trade, secret like cobra in his hole, iss an Intelligence. A man, I have decided. It iss veree plainlee manifested to me in number off recent drug affairs thatt there iss a master mind—off its class—moving behind—secretlee—in thee dark—like spider sitting in center off her web—onlee much more active than spider!"

His eyes were growing veiled and absent again.

"Much more active, yess. I trace his hand—thee same hand—in many affairs."

"What affairs? Get to facts, will you, Dass?"

"Oah, readilee, my dear fellow. Such affairs as thee collapse off Harlow's Bank and arrest off directors; thee scandal off Countess off Barford's Jockey and thee Barford heirlooms; thee recent matter off thee defalcations off four cashiers at the London & Southern Bank; the accidental death off Clyde Hamer off thee Airplane Postal Service; thee fifty-per-cent drop in value off thee shares off Burma Ruby Company; thee murder of Colonel Carrel on Salisbury Plain; and many other recent affairs!"

Salaman stared.

"You mean to tell me that you can trace the hand of this mysterious Master Mind in all those affairs, Dass?"

"Oah, yess, by all means," said Kotman Dass, with an ingratiating smile.

"How?" said Salaman, stiffening.

"Oah, veree simple matter. My reflections have brought me to conclusion thatt this Master Mind whom I call in my mind by thee letter X is in control off great bulk off smuggled drugs and also director off distribution off same to drug addicts."

"Hum! He'd make a big profit—if there were such a man," said Salaman.

Kotman Dass shook his head gently.

"Itt does not seem to me—if you are agreeable, Mister Chayne—that X cares veree much about thee profits off drugs. He would do better than thatt!"

"How d'ye mean, Dass?"

"It iss complicated matter. I have formed conclusion that thee man X—that is to say the Drugmaster—first ensnares with drug habit people—women—highlee placed ladies—"

Salaman scowled.

"Be careful, damn you, Dass!"

"Oah yess, assuredlee," said the fat man, hurriedly, and continued: "X ensnares people who know valuable secrets, who have valuable information confided in them—such as financier may confide in his wife—and presentlee, depriving victim off drug, he reduces victim to condition in which poor soul will exchange important secrets for fresh supply off drug. Then X uses secrets for his own benefit."

Salaman stared.

"You believe that, Dass?"

"Oah, I can mathematically demonstrate that itt iss true,"' said the fat man.

"And you say Lady Argrath is one of his victims, do you?" persisted little Mr. Chayne.

Kotman Dass glanced swiftly at the menacing green eyes, and hastily looked away again.

"Oah, noa, decidedlee I do not say thatt!" he answered. "But itt iss very conceivable thatt she may be!"

"Bah! Heart of a white mouse!" sneered Salaman, turned on his heel and left the room.

Kotman Dass listened for a moment, grinned nervously, then leaned heavily back and submerged himself in that deep sea of thought in which he spent half his life.

SALAMAN CHAYNE was far more disturbed by the "conclusions" of Mr. Dass than he had allowed that curiously gifted individual to see.

He had many times disputed the correctness of his partner's views on matters which he had considered—but he had never yet found the fat man wrong in the long run.

And the "cowardly" denial that Lady Argrath had anything to do with the mysterious X was too belated and too obviously inspired by the physical terrors of Mr. Dass to be taken seriously.

Salaman, out of his experience, knew that a woman was almost certain to be what Kotman Dass said she was. For the fat man was uncannily gifted, and had long ago proved it.

Still, even the cleverest man makes a mistake sooner or later, and Salaman Chayne presently left the house in Green Square with the hope though not the conviction that possibly the time had come when Kotman Dass was making his first error.

"I think the cowardly hound is wrong—I'm sure he's wrong," mused Salaman as he stepped briskly along. "But, in any case, I shall form my own judgment. If there is anything in her manner this afternoon to suggest that he is right I shall not fail to observe it."

He was going to call on Lady Argrath, and he intended to study her more closely, and from a different angle, than he had ever done before.

But she was "not at home," and he sought his club where, for tea, he took two whiskies and sodas—absorbing these with an air of ferocious gloom which very effectively procured for him the solitude he desired. But even the stimulants were contrary. They seemed to depress him rather than raise his spirits.

Small, bristling and sulky he sat long over his second drink, pondering the statements—as many of them as he could remember—of Kotman Dass. His confidence that the fat man was wrong had long dwindled.

He endeavored to recollect some of the affairs which Dass said had resulted from the infamous activities of X, the drugmaster, but except for the mysterious murder of Colonel Carrel, a quite recent sensation, and the drop in Burma Ruby shares, they had slipped his mind.

"How the half-bred rascal contrives to put two and two together in the way he does puzzles me—would puzzle any normal-minded man," muttered Salaman to himself, "and I don't see that he had the slightest ground for connecting Lady Argrath with this—this drugmaster," he added, comfortably ignoring or forgetting that he had refused to listen to an account of the obscure and intricate mental processes which had brought Kotman Dass to his "conclusions."

"I don't see it—I don't see it at all. Damn it, I decline to see it," snarled Salaman at half past seven, finished his whisky, was conscious of hunger, and went sullenly forth to dine at Gaspard's, a small, quiet but well-managed and rather expensive restaurant in a side street off the Haymarket.

Still pondering his problem he secured his favorite corner, rather brusquely desired the head waiter to help choose him his dinner, and continued to ponder.

"She's altogether too fine and sweet and beautiful to have to do with this X man. What signs has she ever shown that she uses, drugs? Occasionally she's depressed, yes—and occasionally she brightens up rather quickly—but so do many people."

Dimly it came to him that whenever that sudden change had happened while he was with her she had left him for a few moments. That is—she had left the room languid and melancholy, and a little later she had returned a different woman. A little thing, of course—but did it mean anything?

"But drugs eat away a woman's beauty—and a blind man could see that Creuse Argrath is one of the most beautiful women in London! And she has told me herself that she does not get on with James Argrath. Certainly that's not hard to believe. James is a money maniac—always abstracted, always brooding, his mind obviously always hovering over the gold tide in the City—like a fish hawk or a gull over the water. No, Dass is wrong; he—"

Salaman's train of thought was suddenly dislocated, for a woman sitting several tables away with her back to a pillar which had helped conceal her from his quiet corner, moved her chair slightly and so became more plainly visible to him.

The eyes of the little man suddenly glowed.

It was Lady Argrath dining with a man whom Salaman had never seen before.

He had been right when he spoke of her as a beautiful woman. It was impossible that she could be under forty years old but she looked nearer twenty—even to-night when, as Mr. Chayne instantly decided, she was not at her best. He frowned a little as he noted several points which to-night she had needlessly stressed. Her mouth, a trifle wide but exquisitely shaped, was redder than usual, and her wonderful skin was whiter—almost dead white. Her eyes shone feverishly out of shadows which owed something to the art of a capable maid, and her wonderful mass of coppery hair was dressed in a style wholly new to Salaman Chayne, and quite unlike her usual style. And it seemed darker to-night. Her evening frock was much more daring than those in which she usually appeared—and these were never illiberal—and she wore big pearl earrings, a form of jewelry she usually claimed to dislike.

The meticulous Mr. Chayne frowned as he watched her.

"She's changed herself to-night," he told himself. "One would say that she desired to look less like Lady Argrath, more like some star of the half-world. And she's succeeded."

He ran a cold eye, jealously disapproving, over her companion, but found in him nothing to hold his attention long. He was a thinnish, fair youth, probably under twenty-five, with a high, rather bulbous forehead, dim-looking bluish eyes, a little fair mustache, and a receding chin. There was something vaguely foreign in his appearance.

Salaman decided that he looked like a young German lieutenant in unfamiliar mufti, and turned again to Lady Argrath.

She was talking a good deal, very low and rather hurriedly, and her manner was touched with a certain vague and uneasy urgency—quite unlike her normal easy selfpossessed poise. She never looked away from their table.

"She's—altogether different to-night," said Salaman. "Why?"

He did not know and hardly attempted to guess.

"If that boneless scoundrel Dass were here no doubt he could explain it—to his own satisfaction if not to mine," said Salaman. "But I'm glad he's not here."

Mr. Chayne nodded a little to emphasize that.

He turned away, looking up as a man paused by his table. He had come so silently that Mr. Chayne was a little startled, though he gave no sign of that.

"Can you put up with me at your table, Mr. Chayne?" asked the newcomer. "Gaspard must be making a fortune—the place is crowded."

"Very glad to see you, Kiss. You happen to be the one man I'd have chosen to share a table with to-night."

"Ah, is that so?"

The colorless, blank, lidless-looking eyes of Mr. Gregory Kiss lingered on those of Salaman Chayne for a few seconds. Except for a certain melancholy they were totally expressionless. The eyes of Mr. Kiss always were those of a sleepwalker—in appearance only.

"Is that so?" he repeated and began to stare blankly, listlessly about the restaurant.

Mr. Kiss and Salaman were old acquaintances, although Kiss was about the best private detective in town whereas Mr. Chayne's occupation, normally, was perilously akin to that of the company of free lances upon whose existence and varied activity the detective's livelihood largely depended.

In appearance Mr. Kiss was precisely and exactly like a lean, weather-worn head coachman temporarily and rather unexpectedly in evening dress. The only thing lacking in the dark, middle-aged, rather deeply lined face was a straw between the tight, thin lips.

"Why?" asked Mr. Kiss.

Salaman had seemed to hesitate. But now, his eyes on Lady Argrath, he spoke.

"I've been listening to the crazy theory of a friend of mine," he said.

Mr. Kiss nodded, his eyes on the menu.

"Crazy theory—there's a lot of those about, Mr. Chayne. How crazy was this one?"

"Oh, hopeless, hopeless," snapped Salaman. "My friend was saying that he believed the illicit drug traffic in this country was controlled by a mysterious master mind who did not look for his profits to the sale of the drug so much as to using the confidential information which his drug-taking customers gave him. It was wild, of course. All right for a novel—or a cinema film. But not in real life, eh, Kiss?"

Mr. Kiss appeared to reflect.

"Hum!" he said. "A master mind, you say, Mr. Chayne? What put that idea into your friend's head?"

But Salaman had no time for details—and less inclination. Kiss was all right—a very quiet, decent chap in his way—but he was a detective and the way of the detective was not the way of Mr. Salaman Chayne.

"Oh, Lord knows, Kiss. This chap—a man I met in the club—don't know his name—had a string of reasons, I gather. But I've forgotten 'em."

"That's a pity, Mr. Chayne," said Kiss. "For I should say that your friend is right."

"Right!"

Mr. Kiss nodded.

"Oh, yes. It's pretty well known—guessed at, anyway."

"Known? D'you mean to say that it's true—and that the man is known? Why don't they arrest him?"

"For two reasons. One is that they don't know him. They know of him. And another reason is that even if he were known he is unarrestable. They say that no ten men could arrest him. They could stop his traffic, but they could not arrest him."

Mr. Chayne bristled pugnaciously.

"Couldn't arrest him! Why the devil couldn't they arrest him?"

Mr. Kiss sighed.

"They would be dead before they could get within a yard of him. He would be dead himself, of course. He is said—rumored—to carry always a couple of bombs—flat, specially constructed bombs—and they are set with hair triggers."

"You mean he'd blow himself up and everybody near him before he would allow himself to be arrested?"

Mr. Kiss nodded thoughtfully.

"Yes, that is what I mean," he said in a voice of settled melancholy.

"But sooner or later—when they know who he is—they will get him?" asked Salaman.

Mr. Kiss shrugged and began to eat his soup.

Salaman looked at him curiously. He wondered if Mr. Kiss were after the drugmaster himself. Kiss was just the sort of queer, quiet customer to pin him, he thought—in spite of his bombs.

But he had no more time for speculation on that matter just then, for Lady Argrath had again caught his keen attention. She was leaning toward her companion, speaking very earnestly. She seemed to be making some request to which the fair-haired youth, frowning, would only respond with little shakes of the head and tiny shruggings of the shoulder.

Mr. Chayne watched intently. And the melancholy Mr. Kiss watched him, as well as Lady Argrath.

Presently Kiss spoke again.

"A sad thing about Sir James Argrath."

"Sad? What do you mean?"

"Argrath failed for a quarter of a million this afternoon. It's in the last editions of the papers."

Salaman's eyes narrowed.

"Argrath failed!" He scowled ferociously. "Why, they said he was a millionaire—and a pretty careful one at that."

"Him! Well, it hasn't helped him much. He failed—awkwardly, too. There are suggestions of—um—mistakes. Shouldn't be surprised to hear that he's been arrested!" Mr. Chayne's scowl deepened as he watched Argrath's wife.

What was she doing out—almost in gala attire—to-night? The evening of a day on which one's husband fails "awkwardly" for a quarter of a million is not usually selected by a normal wife as an evening for being out.

But even as the well-marked brows of the little man knitted over the problem, Lady Argrath and her companion rose to leave.

Salaman Chayne made up his mind quickly. He would follow them. It might be quite simple. If the fair youth put her in a taxi and ordered the driver to her home he, Salaman, would join her and look in for a few moments to commiserate with his cousin. If she did not go home it might be as well to know where she was going and why.

Without flurry he paid his bill, said "Au revoir" to the melancholy Mr. Kiss, and leaving that gentleman rapt in intent study of the menu, he went, with his peculiar, jaunty, cocky walk, out of Gaspard's.

Lady Argrath and her escort had not taken a taxi. It was a glorious summer evening, just cool enough to be refreshing, and wherever the couple were bound they clearly intended walking. It was at once evident that Lady Argrath was not yet returning to her home.

Salaman followed them—behind one of his biggest cigars. Behind the unconscious Salaman followed a lean, tall, soft-footed man exactly like a slightly dyspeptic head coachman lacking a straw for his mouth—the melancholy Mr. Kiss.

Ten minutes later Salaman was bending over the lock of a door in a small, rather secluded block of flats somewhere between the south end of Charing Cross Road and St. Martin's Lane.

Lady Argrath and her escort had disappeared into the flat guarded by the lock of that door.

There was a queer, secret, rather ugly atmosphere about that house and Salaman had been quick to feel it. A place dimly lit, secretive, and though well-fitted and clean, boding and suggestive of dark and ill-omened things. It was oddly silent there, also, and the roll of traffic west and south reached him only as a far-off murmur. It was well chosen for one needing a secret rendezvous, thought Salaman Chayne, and with the thought he was instantly aware that this was the note of the place.

A place of rendezvous—mysterious, furtive, a dark corner—needing no hall porter because none ever came here who was not perfectly well acquainted with it. The sweet scent used by Creuse Argrath still lingered on the warm close air.

A man's voice was suddenly raised inside the flat.

Salaman listened for a second.

"Why—it's James Argrath! What are they doing here?"

His face was set in a look of sheer amazement.

Argrath was almost shouting—it sounded as if he, this quiet, reserved, excessively controlled man, was indulging in a furious burst of reproach, of upbraiding.

Salaman's slender, steely fingers hovered about the lock with gentle, delicate, groping, tentative movements and a small, shining instrument of metal showed for an instant. Then the door opened a little, absolutely without sound. Mr. Chayne understood locks of all descriptions, though few guessed it.

He stepped inside, soundless as a cat.

In a room on his right two people were quarreling furiously—Sir James Argrath and his wife. Salaman Chayne listened, craning close to the door.

Argrath was shouting, but, from where he now stood, the listener could glean that the predominant note in his cousin's voice was less of anger than despair.

"If you had been my worst enemy instead of my wife you could not have done me a greater injury or contrived a more infamous treachery!" he was saying in a high, shrill voice that was not free from a vibration of anguish. "Why did you do it?"

The voice of Lady Argrath cut in chill, composed, very clear.

"I don't understand. Put that pistol away. I will not listen or talk to you an instant longer if you threaten violence. Put it away—point it away—"

Mr. Chayne judged it time to interfere. He turned the handle of the door and entered swiftly, neatly.

It was a well-furnished apartment of considerable size and the Argraths were standing in the middle of it, facing each other. The man had an automatic pistol in his hand—drawn back as though he had snatched it back from an attempt to knock it from his hand.

"Good God! What are you two trying to do?" snapped Salaman.

They turned swiftly—the woman was the quickest—looking down at him, startled.

Argrath spoke first, letting his pistol hand fall to his side.

"Ah, you, is it, Chayne?"

"You—what are you doing here? How did you get in here?" broke in Lady Argrath eying him keenly, her beautiful face suddenly sharp and, for a moment, cruel with suspicion.

Salaman shrugged, but before he could speak Argrath went on heavily. His normally pleasant face was intensely pale save for two feverishly flaring red patches high up above his cheek bones; he was unshaven, still in his City clothes, and his eyes were shockingly bloodshot. His mouth seemed oddly twisted.

"Listen to me, Salaman, and I'll tell you what I'm trying to tell this woman—this wife of mine—this drug slave and traitress—the result of the crime—the crimes—she has committed against me. It seems that she hates me—has hated me for a long time—because she believes I have been ungenerous to her in money matters. She says that—but it is not true. She hates me, yes, but she hates every one else who does not administer to her insane craving for the drugs that have destroyed her—the drugs she came here to-night to get!"

He laughed, hysterically.

"God, what I have been through—what I have suffered—how I have worked and overworked—wrung my brains for twenty hours of the day for months. A circus horse, Salaman, that's what I've been—going round and round in a circle—never getting anywhere. Oh, I'll explain. Keep quiet, Creuse, damn you!" He menaced the woman with the pistol.

"No—stand back, will you, Chayne? It's not for her, this little toy—it's for me presently. Look at her, Salaman—she doesn't believe it. We'll see about that. She's cool enough about it—eh? Keyed up with her infernal drugs. That's it, keyed up—"

Salaman Chayne stepped nearer, intending to try to quiet him, but he saw that. Argrath was quick now and perceptive with the darting uncanny perception of the fey.

"Listen, I say—be still, you leopardess, your turn will come! I'm speaking now. Listen—listen and leave me alone or I'll go down to Trafalgar Square and yell the truth to the crowd there. I'm ruined, Salaman—I've failed to-day for a quarter of a million cold—eh, a quarter of a million! I! James Argrath who used to keep big companies spinning in the air like a juggler—only easier. A year ago I was caught in a bit of a squeeze—nothing but a squeeze—a temporary thing. Every business man gets that. It's nothing—if one is not surrounded by traitors—hasn't a traitress on his own hearth, in his own home. It was necessary to economize for a little—only for a little while. She wouldn't help. You see, she'd only married me for the money I had and when that was gone there was nothing to keep her loyal. And she was already a drug slave—even then. I begged her to be patient, but these drug eaters don't understand what patience is. She continued to waste money like water—what she did with it God knows—it went. She kept coming for more and I had to refuse. I hadn't the money and I needed all my credit in the City—every ounce of it. I begged her to wait patiently and I confided in her my great coup; there was a big concession going on the west coast of Africa—no, not oil, but gold country—gold and a great chance of radium. It was a fortune—and it was mine—should have been mine. At the eleventh hour I was forestalled, Salaman. Why? Because that woman had sold me out to—some one. Probably some sly, stealthy, unseen brute that supplied her with drugs—eh? Something special in the way of drugs. She had told him—or somebody. They stepped in and forestalled me on that concession. Eh? What do you think of that—a man's own wife—the very woman he was toiling for? Of course I never guessed. I hung on—working like an insane thing—and made, forced, another chance—a patent, this time; a big wireless improvement—a fortune. You'll hear of it yet. I told her of it one night—to help out, to help her to wait—as men do tell their wives things. I was forestalled again. My inventor man was bought away from me. She had betrayed me again. Why? What for? Good God, it was mainly for her I was struggling! Three times that happened. It was like pouring water—no, blood—my own blood—into a bottomless vessel. I fought for chances, half killed myself for chances, won them, shared my relief with my own wife—and lost my chance. Sold out! And I took risks, bad risks, and the police are—will soon be—after me. Oh, I understand things now. I know now. It came to me one night like an inspiration. I had her watched—my man tracked her here to this flat. It's here—but there's one—the big one—that my man hasn't been able to get sight of—as silent, and swift and cunning as a snake. Dragour! That's his name. I've learned that, Chayne. Dragour—eh, what a name for the reptile such a man must be! I've come here to kill him—but he's slipped me. Dragour—"

"Kill him! You kill him! You would find it easier and more profitable to kill yourself!" said the beautiful drug slave, facing him, her brilliant eyes as cold as her voice was cruel.

It was clear that she hated him—as clear as it was that she had injured him irreparably.

Argrath stared stupidly, pierced by something in her tone.

"Creuse, you meant that—you would like that?" he said in a strange, almost wailing voice.

She stared at him levelly, her eyes merciless.

"Very few ruined gamblers have the courage to do that, and you are not one of them. It would chime admirably with my mood if you were!" she said—and even as she spoke Salaman Chayne was conscious of the set deliberation of her tone. She, too, was possessed—she knew that Argrath would take up her icy challenge. And, magically, eerily, Chayne knew it also. Argrath had loved her—and he had reached or been driven to a point, where it needed only this from her. He was at the very brink of the abyss—she could have pulled him back with a word, a gesture. But she had thrust him down.

"Ah—you say that, do you?" shouted Argrath in a terrible voice, hoarse and broken—swung the pistol to his head and fired.

A sudden red stain, a splash, a flower of blood, appeared like magic on the shimmering silk of her dress, just above her heart.

Sir James Argrath collapsed in a queer, limp crumbling heap—a dreadful sight.

Salaman Chayne, glaring, sick, stabbed a lean finger at the soulless creature facing him.

"You—you knew he would do that! You knew! You have murdered him. But for you—for what you said he would not have done that."

Her eyes, blazing with an infamous excitement, looked suddenly beyond him, dilating widely, and she stepped back.

"I will bear witness to the truth of that," said a voice gravely over Salaman's shoulder. The little man glanced round.

It was Mr. Gregory Kiss who spoke, mysteriously, soundlessly appearing from nowhere.

The woman moved back toward a curtain at the other side of the room.

"That man killed himself," she said. "Don't dare to accuse me."

Mr. Chayne stepped toward her.

"You goaded him to the deed, and it can be proved."

She laughed wickedly, as cold-blooded as she was fair.

"Proof! Proof! Do you imagine I am without a witness of this mad suicide?" she said.

"You will be detained—" began Kiss quietly.

She tore aside the curtain, laughing acidly.

"Hold these men, Dragour," she said, swaying back.

The black muzzle of a big pistol seemed to shoot over her bare shoulder like the head of some huge viper, and behind the weapon was the face of Dragour, the Drugmaster—a dark and bitter face, stamped with the unholy hall mark of a thousand evil deeds and appalling thoughts—a face malign and cold and frightful, like a dark mask, set with two black eyes that stared with a fixed, bitter and unchanging stare at the two startled men by the body of Sir James Argrath.

For a full second all three stood perfectly still, like wax figures—almost as though they would never move.

Then the full, rich voice of the woman broke on the silence—slow, musical, but intolerably insolent.

"You see, do you not? The devil takes care of his own!"

She laughed.

A black void seemed to yawn behind Dragour and the woman, they moved swiftly and even as Salaman Chayne leaped toward them the secret door crashed to.

Mr. Chayne tore down the curtain, but there was neither key nor handle visible on that door. If it opened from the inside at all it was evidently by the manipulation of some concealed device.

Pallid with fury Salaman turned on Mr. Kiss.

But that one, already at the telephone, shook his head.

"It was a bolt hole," he said quietly. "They are away. Dragour has a thousand exits. Nobody can expect to catch him in a cul-de-sac at the first attempt. All in good time, Chayne—all in good time."

He began to call up the police.

Mr. Chayne dropped on his knees to examine the dead man.

But that was quite useless. Sir James Argrath had made no mistake in the carrying out of his final coup.

Salaman rose, staring about the room. As yet he was conscious of no sense of loss or pity, only of a cold and inexorable anger. He scowled in his effort to memorize everything in that room perfectly. He needed to remember as much as he could—for he had long since learned that everything, every little microscopic detail seemed ever to serve as valuable data to the prehensile brain of his remarkable partner Kotman Dass.

He wished he could telephone to that mountainous man to come and see the place for himself—but there was no hope of that.

Nothing on earth would induce Kotman Dass to enter that room until every sign of the tragedy was removed.

All that Mr. Salaman Chayne could do was to incise his memory with details for Dass, and painfully retail these to his partner when presently the police should have finished questioning him and Mr. Kiss.

And so, swearing to himself that he would never rest, never cease his search for, nor abandon the trail of the drugmaster until that living pest was taken—alive or dead—Salaman settled down to await the arrival of the police.

"They'll be here any minute," said Mr.

Kiss quietly, and began softly to prowl about the apartment, peering, it seemed to Salaman, at everything, but touching nothing.

Mr. Chayne watched him in silence.

"He may be—I think he is—a good man, but Dass and I will prove the better bloodhounds," said Salaman, and shrugged, eying the still figure on the floor. "We shall see."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.