RGL e-Book Cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

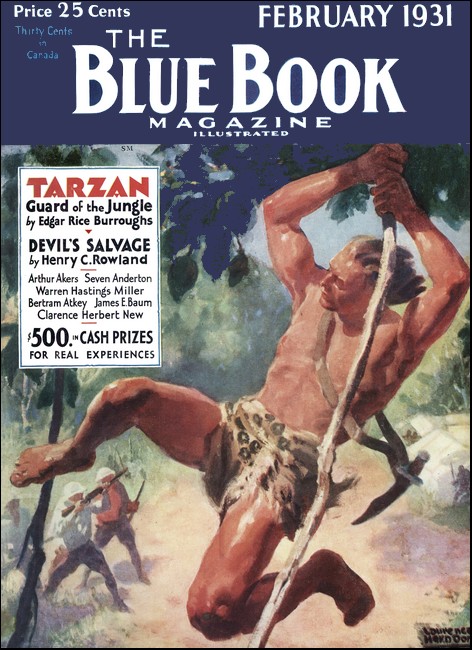

The Blue Book Magazine, February 1931, with "The Vulture of the Hills"

PLUMP little Mrs. Cormorant beamed up at her husband, that gaunt, six-foot-six, red-mustached person, Captain Lester Cormorant—late of the Bolivian Light Horse, he invariably maintained—as, having sent the butler out he filled her port glass with his own hands.

"Thank you, Lester dear. I love to have you do a thing like that for me!"

Captain Cormorant pulled at his great drooping mustache, and refilled his own glass.

"When, dear heart, I sink so low that so trifling an attention, so truly trivial an indication of my love and gratitude to you becomes an effort, or anything but a keen joy, then I trust that I may be dealt with as the dastard hound that I shall have become!" he said warmly—and in his warmth, cracked a walnut into a quite uneatable pulp of nutmeat and shell.

"It is true, darling," he continued, "that since birth I have been wholly nonmoral—yes. In their infinite and inscrutable wisdom the gods saw fit to usher me into this world devoid of one single moral, good or bad. And so, Heaven help me, I have forever been afflicted. No fault of mine, asthore, God knows. I am—I have always been —as Providence made me." He sighed deeply.

"And I shall never deny—when, as now, I am in converse with one whose sympathy is boundless—that I was one of the poorest jobs Providence ever turned out! My heart, I drink to your dear eyes! To you, the one sweet soul in all the world who understands me—nay, loves me —and whom I adore! I drink to you!"

He did so, and—refilling his glass—lapsed into a despondent mood, staring at his wine with absent eyes.

"Never, Louise, never shall I cease to marvel within my secret, nonmoral soul that you—you, of all women in the world—should deign to lean down from the height of— ah—your naturally lofty plane, to gather me in under the soft dove-wing of your personal love, and the steel-true, gilt-edged security of your income—me, a man who has been battered and rebattered, buffeted and rebuffeted about the world like an empty can on a lee-shore—a man, dearest of all, who, through no fault of his own, has been anything from a slave-raider to a brigand—"

"A brigand! A brigand, Lester?"

The bright eyes of Louise opened expectantly. She loved to hear the stories of his completely piratical and unashamedly nonmoral past, which Captain Cormorant was capable of pulling up on an instant's notice.

It is even probable that she believed them. People believe more improbable lies than those of the afflicted Cormorant. But whether she believed them or not, they certainly amused and interested her—one of the few women in the world who has been married for her money by accident and has never regretted it.

When Captain Cormorant endeavored to acquire illegally her car, which, some years before, he had found standing unattended on a foggy night, he had not known that Louise—not beautiful, but with a heart of gold—was in it, and the delightful matrimonial climax at which they arrived when halfway to Brighton, he discovered her in the stolen car, would always remain in their minds as a wonderful, even miraculous example of what the gods of good luck can do when they try....

"Yes, alannah, a brigand, God forgive me! I have been a brigand," admitted the Captain.

"Tell me about it, Lester—please, darling!"

"Why, dear soul, of course—if it is possible that you can be interested in the account of what, I imagine, must be as futile an enterprise as any poor, nonmoral doomed soul, like myself, Heaven help me, ever embarked on!" He selected an expensive cigar.

"By your good leave, dearest," he said, and lighted it....

Yes, [he resumed] a brigand! All untrained, improperly equipped,—totally lacking that nice, that hairtrigger technique without which no brigand can ever hope for success,—I took, many years ago, to the mountains in a far country!

If I seem to imply to you, my one woman, that I "took to the mountains," as the saying goes, willingly or with any real zest for a career of brigandage, then I imply that which is incorrect. I left the silver-mining town of Salto de Novo Diamantina for the neighboring mountains in the haste and confusion and total lack of sympathetic understanding on the part of the general public which usually characterizes the exit of a nonmoral man from any town. It was—from our point of view, Louise mine—an ignorant, greedy, passionate, hasty and bloodthirsty populace at Salto de Novo Diamantina in those days. I believe I may say—to you, at any rate, darling —that in spite of the lifelong affliction from which I suffer, I am not a man wholly devoid of personal charm!

No man could have been more popular than I was during the first fortnight of my sojourn in that benighted city of get-rich-quicker-than-ever fans and fantastics. I was popular! I was invited everywhere! And why, do you ask? Was it because of my looks?—my personal charm?—the aristocratic manner natural to me as a scion of a moderately noble old English family?

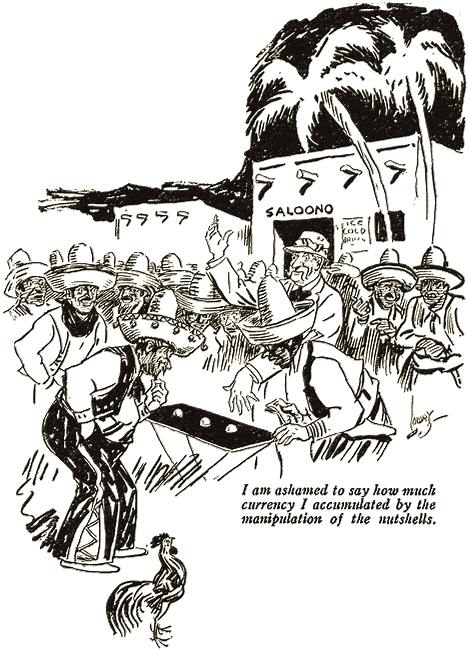

No, dear heart. I had come among them with a novelty. I was at that period a master, an expert, of a small trick designed originally for simple fun and innocent entertainment at the dinner-table. One takes three walnut shells, slightly prepared, and a pea (made, of course of gray rubber) and, placing the pea under, let us say the middle shell, pushes the three shells neatly into line and invites the populace to bet on which shell covers the pea. An amusing little thing. The pea, of course, is not under any shell—it is between the finger-tips of the operator of the shells, and when the bets are completed he merely has to drop it blissfully under the shell which has not been bet on. A pleasant joke— to a strictly unmoral man. But those barbarians proved to be uninterested in the trifling sleight as a joke. It was my money that they were after, life-mate of mine! They came at me so eagerly, so avidly that I resolved to teach them a severe lesson. I am ashamed to say, dear heart, how much of the general-purpose currency of that rich but nasty town I accumulated by the simple manipulation of the merry little nutshells within ten days. Most of it, I know.

But then a hitch arose—alas, these hitches! A Mexican came into the town who understood such matters. He took a dislike to me for some obscure reason—and, to cut a long story short, dear heart, I left the town (and my accumulation) so narrowly ahead of the leading member of the posse that his bullet struck the first big rock in the foothills of the great mountain range no more than the fraction of a second after I slid behind the rock! A second's delay, an instant's sluggishness, Louise, and I should have been shot like a mad slug—dog—like a mad dog!

Can you then wonder that, having gained the inmost recesses of the mountain, I resolved on a bitter revenge?

I know well that you cannot! Bitterly mortified and hurt, I resolved then and there, Heaven forgive me, Louise, to become a brigand—a vulture of the rocks, a terror of the district, a being without mercy—specializing in the spoliation and punishment of those ungrateful hounds, the denizens of Diamantina!

As I have said, star of my soul, I was but ill-equipped. A revolver, a few cartridges, and the clothes I stood up in—no more! Ah, dear heart, what a capital on which to inaugurate what I hoped to make one of the most profitable concerns in the country!...

I slept in a cave with some bats, an owl or two and a few serpents who, by their goings and comings keep me wide awake half the night; the bitter cold at that altitude kept me awake for the remainder.

So you will readily realize, darling, that the man who reeled forth from the cavern into the eye of the rising sun next morning was hardly Lester Cormorant at his best!

Ravenous with hunger, parched from bitter thirst, racked with mortification, yet steely with determination, I made my way, revolver in hand, toward the main track which led to the pass through the mountains. Only the vultures—the great, bone-breaking vultures of those parts—saw me as, an outlaw, an outcast, I prowled to my post. I had not eaten for many hours. I quenched my thirst at a spring, and looked out sharply for game as I went. Nothing moved there but stinging lizards. I shot one—tried to eat it. Fresh stinging lizard is not likely ever to become a popular dish. Dried or smoked maybe—but not fresh.... I kept grimly on to the point of vantage at which I was aiming, Louise, reached it, and proceeded to lie in wait—in ambush—for the first comer.

Nonmoral as I freely acknowledge myself to be, hurt and embittered as I unhesitatingly admit I was at that time, nevertheless it was not my intention to include among my forthcoming clientele members of the gentler sex. I have, thank God, always been automatically chivalrous, and I believe I shall always remain so.

Yet so curious are the workings of Fate, my love, that when an hour later, I heard the ring of hoofs on the track and leaped forth out of my rocky ambush, the riders of the mule proved to be a mother and her child!

Had the woman been a stranger to me I have very little doubt that I should have lowered my weapon, swept off my hat with a bow, waved them on with, possibly, a smiling observation to the effect that I, the Vulture of the Hills, did not prey upon women or small families. But this woman I knew. She was a Mexican; none other indeed than the wife of that self-same greaser—er—Mexican—who had started the propaganda which had undermined my popularity and had headed the posse which had, so to speak, pitched me out of Diamantina on my ear!

Our eyes met. We recognized each other in a flash. She was beautiful in a hard sort of way—but I was in no mood for beauty just then. I held her up, informed her that she was my prisoner, and that the amount of her ransom would be ten thousand dollars.

She objected that the figure was excessive, and we retreated to my cavern to discuss the matter.

Beautiful in her way though she was, she was a haggler from head to foot. But finally we agreed on a figure, namely five thousand dollars in cash and a ninety-day note for twenty-five hundred.

"It's a bare-faced robbery at that," she said. "But I am in your power! I'll get the money now!"

She rose from the rock on which she had been sitting and reached for the bridle of the mule.

In my turn I reached for the child—the hostage.

"Pass the baby," I said—God forgive me.

She stared.

"Pass you my baby?" she shrieked.

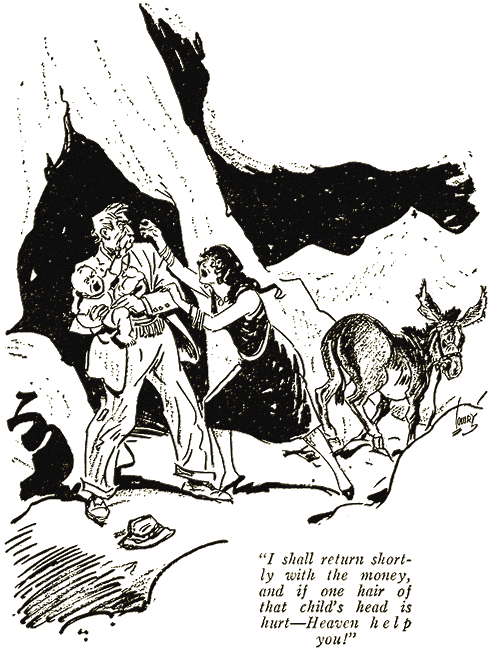

"Certainly, madame," I said. "Even a brigand," I added satirically, "is entitled to some sort of security or collateral. Is it possible that you figure to yourself that I—I, the Vulture of the Hills—am the species of brigand who releases his prisoners without taking the simple precaution of holding a hostage? No, no—pass me that baby!"

There was, of course, a truly terrific scene. But I beg you, do not hasten to judge me, my dear Louise, until you have heard my story to the end! At first glance, nonmoral through no fault of my own, though I was created, I agree that no man, be he brigand or anything else, should separate mother and child—no, not even for seventy-five hundred in cash and a note for the balance. That I admit. But I was desperate—and I was goaded to the act by hunger and humiliation.

The baby took it well—better far than the woman. It looked charming and tranquil as she finally transferred it, still sleeping, to my arms.

"There is condensed milk in plenty in the saddle-bags, man-eater," she said insultingly, and dumped the cans out, together with a loaf of bread and a bundle of infantile accessories.

The child awoke and began to cry.

"I shall return shortly with the money and if one hair of that child's head is hurt—nay, even out of curl—Heaven help you, vulture or no vulture!"

I merely smiled at the threat and with the infant still wailing in my arms, I watched her ride away. She looked back every now and then to shake her fist at me.

I sat down to rest and nurse my little hostage. I glanced at the instructions on one of the tins of milk and noted the feeding hours recommended for children of its age—somewhere about a year old, I figured. For, come what may, dear heart, babes must be fed. I did not feel hurt about that, though the thought did flash into my head that even brigands need to be fed too. Where mine was coming from until the Mexican woman returned I confess I could not imagine!

I was pondering this problem with the crying child in my arms, when suddenly it emitted a yell so piercing that it made me jump. I tried to soothe it. But these Mexican children do not seem to me, my love, to soothe easily. I did all that a man—moral or nonmoral—could do, for the next half hour. But there was no sense of fair play, nor of ordinary gratitude, nor give-and-take, live-and-let-live, about that child. It just fixed its eyes on me in a stare of disgust, hatred, anger and contempt and did its utmost to shout me into a nervous breakdown.

I fed it. I took the most scrupulous care to measure out its milk exactly right as instructed on the tin. I could not have taken more trouble about warming the milk to just the right temperature if I had been a totally moral chef, cooking it for a king! Yes, I worked very hard on that first meal for that child. I broke its bread small.

It understood; it knew; if it could have spoken it must have admitted that it had never eaten a better-prepared meal than that which I, Cormorant, the Vulture of the Rocks, prepared it that day. But it probably would have lied about it—it was that kind of child.

It ate its food with every symptom of sheer, guzzling relish, finished it, grinned sourly at me and began to bawl for more. But I refreshed my memory with a glance at the instructions and was resolute.

"Not for another two and three-quarter hours do you eat again," I said firmly. "Rules are rules. Be quiet! What would your mother say if she were here, you ungrateful little hound! Quiet!" Me starving, you understand, heart of hearts! Starving, but of too proud, too aristocratic a temperament to take a bit of bread for myself. As far as the moral side of the thing mattered to me I would gladly have had a taste or two of the food—but my pride sternly forbade it.

If the creature, having guzzled its ration, had left a little, I would have felt that I had a right to it. But it never left anything—not that locust, Louise.

I kept myself well under control.

I picked it up as gently as ever any mother in the world picked up her offspring, speaking kindly to it. It cruelly stuck its finger in my eye—and to this day, in rainy weather, I sometimes see blue Catherine wheels with that eye. Hurt? Ah, Louise, my life, I know of few more exquisite agonies than that which the little pinky-olive finger of a Mexican baby deftly poked into a man's eye can inflict! Then as I attempted to pass that off with a grimace, the young demon clenched on to my mustache and tore out large quantities of it by the roots.

If its parent had returned at that moment I would gladly have given her back her note for the twenty-five hundred to take the child away.

It would yell till it went a deep pink—a rather dangerous-looking pink.

"There, there—rock-a-bye, rock-a-cock-horse and lullaby!" I would say anxiously.

But it took no notice of nursery rhymes—didn't know any, I imagine. It would keep on screaming and gradually turn dark red! With my blood running cold in my veins I would shout out, "Hush-a-bye, hush-a-bye, little Jack Horner on the tree-top!" To no avail, Louise. The child would keep on till it was fairly purple.... It scared me, I assure you.

At about that stage I tried firmness.

"Silence, there! No talking in the ranks!" I'd shout.

But the child would merely speed up till it was practically black.

The first time that happened I saw that all was over—at least I thought so.

But no! Not at all. That child knew its limits to a millimeter. Every time it was on the point of turning a deeper shade than black it paused for a few seconds, opened its eyes, drew breath, became its ordinary pinky color, tugged at my mustache, or dragged at my nose or my lip or tore at my ear, and looked at me in a cold, sardonic kind of way. Then it would grin an acid sort of grin and do it all over again. If it had been any other kind of human being it would have been hoarse in the first half-hour. But this child was not capable of hoarseness.

I put it down when its feeding-time came again. I got up to prepare its bread and milk and, Louise, it was silent instantly, watching me from behind.

I got the feeling that it was counting every crumb, noting every drop of milk; evidently it didn't trust me. I wouldn't have touched a morsel of its food though I was tottering with hunger. Frankly, dear heart, I would have been afraid to. You see, it had a sort of low cunning of its own. It was getting the ascendancy—and it knew it. It was a bully at heart, and devoid of mercy.

Yes, Louise, there was indeed a Vulture of the Hills in that cave—but it was not I. No, it was that baby! It was young in years but it had the wisdom of centuries under its curls. It ate heartily of its second meal and tried to bite me when I took its spoon away. Then, refreshed, it settled down to howl some more.

I took it in my trembling arms, and it kicked me in the throat.

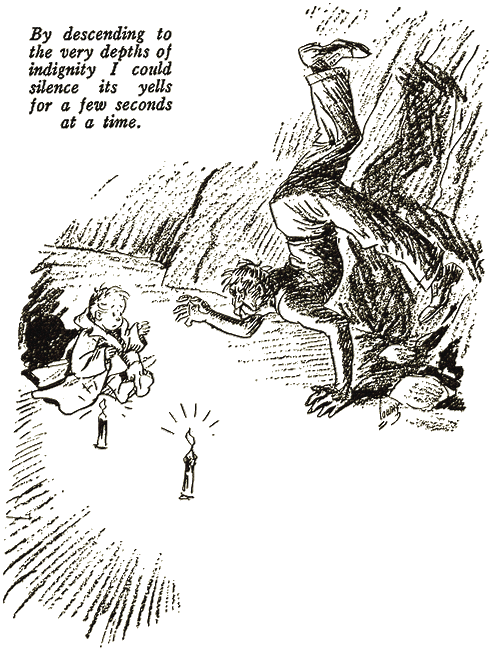

That night, Louise, resolved itself into a battle of wills between the baby and myself.... I lost. I tried everything. Nothing succeeded. Even at this moment, sitting here at my ease, basking in your radiance, I cannot bring myself to describe to you the depths of indignity to which I descended in my efforts to distract for even a few seconds that child from howling and hooting. There were a few candles in that woman's bundle and I lit them all for company. At least I lit all I could hit with the flame of the matches I struck with my quivering hand.

I discovered—in the intervals of feeding it—that by descending to the very depths of indignity I could allay its fury and silence its yells—for a few seconds at a time. If I stood—half naked, for it had most of my clothes to keep it warm—on one ear so to speak, with my feet in the air and the toes turned in, supporting myself with one hand while I waggled the other in the air, the child would pause for as much as a minute and a half and watch me.

But why dwell on what has long become no more than the most important of all my nightmares? Permit me, dear heart, to push forward my story to the hour of dawn. I shall never forget that dawn for it was then that the child having eaten practically all there was left fit to eat, fell into a light and apparently enjoyable slumber.

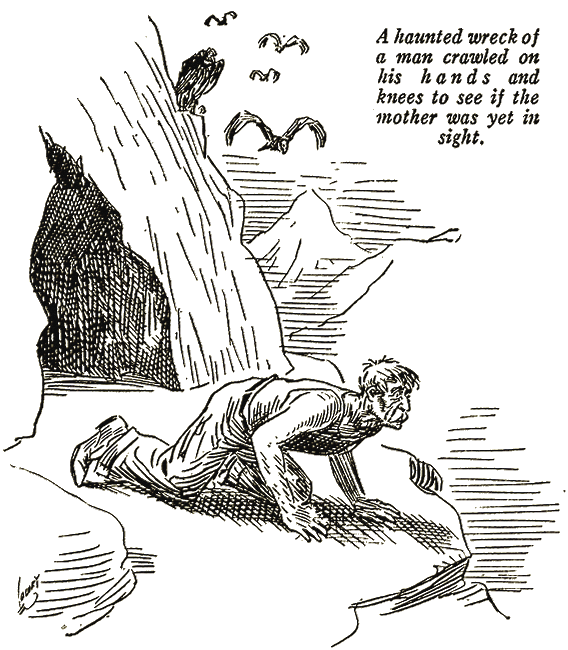

You can, I am well assured, picture to yourself the haunted wreck of a man which crawled silently on his hands and knees out of the cavern in order to peer down the trail to see whether the mother was yet in sight. So weary I was that sleep, regarded as a cure for such weariness, seemed merely farcical—so nerve-wracked that the least whimper from the child in the cavern would have sent me flying down into the first hole in the ground capable of accommodating me—so cold that I could, in a way, have warmed myself by sitting on the frost-tinged rocks around me! So hungry that had I found a tin of beef or salmon at that moment I certainly should not have stopped to peel it before starting on it!

And it was at this moment I heard the ring of a mule's hoof on the track.

I crept back to the cavern, took my revolver, re-issued and watched, listening. It was not the mother—for I heard a man cough in the raw dawn.

He came abreast of the rock that masked me and I leaped out with my last strength and held him up.

He must have seen that I was in no mood for dalliance, for he put up his hands instantly.

"Throw your weapons to the left of the trail—swiftly, for my finger is uncertain and shaky on the trigger!" I said.

He must have believed that formidable truth, for I have never seen weapons thrown away quicker.

"Pitch what food you are carrying at my feet—and let it be quicker than you pitched those guns!" I commanded. "For I am the Vulture of the Rocks, Junior—and my word goes—at any rate while Senior is asleep!" You can guess my condition from my words, sweetheart.

He pitched the food as swiftly as could a conjuror.

"You are my prisoner!" I said.

"I acknowledge it," he replied. His face was white. I must have looked desperate, my darling. "What are your terms? How much is the ransom?"

"Bah!" I said. "Money? You speak of money?"

Fear settled in his eyes. I think he thought me mad.

"I am Don José di Almazan y Marzipan D'Alcoy," he said. "I am willing to pay a worthy ransom!"

"Very well, Don José," I said. "You shall be accommodated!" I picked up a loaf and a bit of dried meat and took a bite or two.

"I have within the cavern a child, for which I have no further use," I stated, gathering fresh courage and determination from each bite of the good bread, the marvelous meat. "It is not what I personally should describe as a charming child, but nevertheless it deserves its chance! You shall take it away from me—for I have had enough of it recently."

His swarthy face changed oddly. It went white. Evidently, I thought, he knows something about children of the type I had been nourishing. But he said nothing.

"You shall swear to me here and now an oath that you will forever protect and guard and watch over and succor this infant—and having done that you shall take it away with you just about as quick as you can do it! And that," I said, between mouthfuls, "is your ransom!"

"So be it!" he said. "I swear that I will ever be as a father to the child."

"Good!" I said. I picked up his weapons, and fetched the baby. It whooped with fury the instant I picked it up. But I, Louise, I laughed in its teeth—its tooth or two. No more, no longer would it have its way with me; I was wishing it on a person better adapted to handle the problem it presented—a rich man, a titled man, a man of his word, above all a moral man!...

Louise, my soul, would you credit it? The instant I handed the child up to the swarthy swell on the richly caparisoned mule it ceased its clamor—even though it was about its feeding-time. He took it, this lean, dark don with arms that seemed most oddly, most singularly adapted to receive it. And it relaxed itself. And—warmly clad in my shirt, though I retrieved the rest of the garments in which I had wrapped it—it seemed to ooze into that don person's arms like warm wax oozing into its mold!

"Yes, señor," said Don José, smiling in a queerish way. "I swear—I affirm to you that I will abide by the oath that is my ransom for the whole of my life's span! Have I, Senor Bandolero, your leave to depart?"

I reached for another piece of dried meat.

"You have it, señor," I said.

He pulled round his mule and left.

Breakfasting happily in the increasing sunlight, dearest Louise, I found myself wondering what the mother would say to it all when she returned.

Well, I was soon to discover, for even as I devoured the last crumb of bread, the final fiber of meat, she came galloping up the trail.

"Scoundrel," she said, thrusting a bundle of notes on me. "Here's your money! Where's my baby?"

I rejected the proffered notes—a mistake, as it proved.

"No, no—no money, señora!" I said. "I have parted with the child!"

"Parted!" she shrieked.

"Yes," I said brutally. "It half killed me. I was glad to let it go—for it had become a question of it or me! It is now in charge of a local grandee—one Don José di Almazan y Marzipan D'Alcoy, to whom any application for its return should be made!"

She stared at me like a person thunderstruck. Her lips moved, her jaw moved, her entire face moved, but even so it was some seconds before she uttered a sound. Then she said: "You parted with that kid to Don José? You actually did that? You mean it?"

"I did," I said. "I do!"

"You fool!" she said. "You imbecile! You—" Well, never mind the things she said I was, dear heart. I'm not—at least not all of them....

"Why so?" I asked, when she stopped for breath.

"Why, that child was Don José's son!" she shrieked. "It was worth a hundred thousand Spanish dollars' ransom to the D'Alcoys. It took me a year's planning to kidnap it! And you, you fool, you give it back for nothing!"

She glared round.

"Man, the hills are crawling with armed searchers after the child! It was lucky for you that Don José chose this trail! But that's how it always goes!" She dragged her mule round. "Luck for the lunatics!"

She drove the spurs into the mule and clattered away.

But I, comfortable and quiet and warm, reclined in the rays of the rising sun, and listened to the sweet silence of the hills, dear heart. And I was content....

CAPTAIN CORMORANT ceased, finished his port, crushed

his cigarette-end in an ash-tray, and pulling his long

mustache, smiled across at his wife. The keen eyes deep-set

in his rather ravaged face caught an unaccustomed sparkle

in her eyes, even though she was smiling.

"My dear," he said very softly, "that was perhaps a trifle exaggerated—a fault to which I rarely give way—just to make you smile." Then he pressed his finger firmly on the bell. "In the course of a singularly varied career, dearest of all, I have noticed that ever after laughter comes a touch, a tinge of that reaction which approaches tears. But I have also discovered that the finest antidote to that reaction is a bottle of the best champagne in the house—"

"Very good, sir," murmured the soft-footed butler from the doorway—and went to fetch it.

"Ah, Lester," sighed the happy wife, "you may be non-moral, but you do understand about things!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.