RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

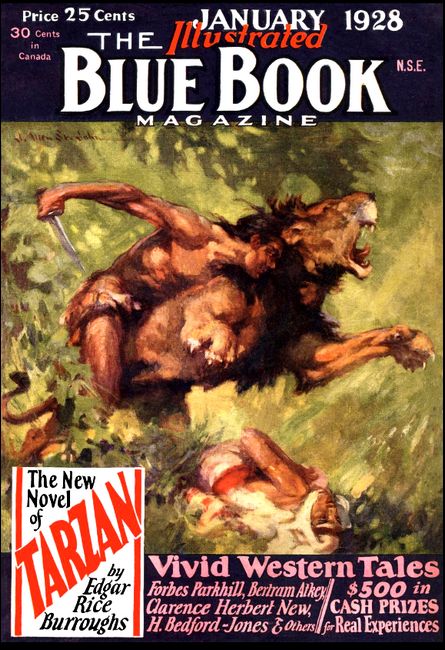

The Blue Book Magazine, January 1928, with "A Flutter in Wives"

There was an eastbound train just pulling out, when a

second and a half later I reached the railway-station.

AMONG the more engaging customs of that afflicted man, Captain Lester Cormorant, late of the Bolivian Light Horse, was one which showed him—totally without morals good or bad though he was, Heaven help him (as he would say)—not wholly impervious to those impulses which do so much to make the good husband. He was accustomed to spend at least two evenings a week at home, amidst the extremely comfortable circumstances of domesticity, in the control and arrangement of which his wife—that placid lady to whom he had proposed in the dark—was so skilled that a superficial observer might easily have rated the Cormorant ménage at five thousand a year instead of the three thousand which was the true sum of Mrs. Cormorant's income.

It was on such an evening that the adventurer—somewhat battered, but with his six feet four inches of height, his colossal Wellingtonian nose, and his great drooping red mustache, still distinguished-looking—and his adoring partner discussed the case of their friend, Sopley-Smyth.

"I see that poor Sopley-Smyth has filed his petition at last," said the Captain, over a glass of port.

"Yes, Lester," replied Mrs. Cormorant quietly. "It was bound to come."

The Captain sighed.

"It is a very tragic thing for a man's wife to run away from him—if she has a couple of thousand a year," he said. "I feel for poor Sopley-Smyth. I am sorry for the man."

"You would not like me to leave you, would you, Lester?" said Mrs. Cormorant playfully—even coquettishly.

The Captain looked very serious.

"Louise, my heart, don't say such things, even in jest! It hurts me—non-moral though the gods have seen fit to make me. I find life sufficiently arid as it is,"—he poured himself another glass of port wherewith, no doubt, to render it less arid—"but were you to leave me, taking your three thousand a year with you, I feel I should never be the same man again. No—never, my heart. You see—ever since that fortunate hour when, struggling in vain against my incurable moral infirmity, I stole your motorcar, with you in it, I have leaned upon you and—Heaven forgive me!—upon your income. Have I not, my dear child?"

"Yes," said the dear child truthfully, "you have, Lester."

"For every word of love I have desired, darling, to whom have I looked?"

"To me, Lester."

"Yes. And for every tenner—every fiver—nay, every modest half-quid—to whom have I looked, Lord help me?"

"To me, Lester."

"Yes, my own. And have you ever failed me? You have not. But Sopley-Smyth's wife failed him—with the result that he is now bankrupt. She, poor soul, has not the noble nature which you possess. She never really loved him."

"Never loved him?"

"No, my pearl. He told me so himself. Why, last summer she refused him the paltry sum of fifteen pounds for the worthy and patriotic purpose of running down to Epsom to see that noble horse, Lemon, make its gallant but unsuccessful effort to win the Derby."

"How dreadful, Lester!"

"Yes, you are right, Louise—it was dreadful! Let me give you a little more of this port. It is a better wine than the last."

"Yes, Lester. I took your advice and gave more money for it," explained Louise.

Captain Cormorant leaned across and patted the pretty hand of his wife.

"That's my good girl," he said. "Now, Mrs. Sopley-Smyth would never have done that. Poor George did once venture to complain of the sherry. What do you think she did, Louise? Remember, that in some respects Sopley-Smyth was a fine fellow—not, like myself, a man foredoomed to drag his way through life suffering from a total lack of morals, good or bad."

"What did she do, Lester?"

"She put him on cooking sherry for a month!"

"How cruel!" said his adoring lady.

"Cruel and mean—yes, mean! You would never put me on cooking port, would you, Louise?"

"Indeed I wouldn't."

She poured him a little more port to prove it, and fondly chose him another cigar.

"Do you think he married her for her money, Lester?" inquired the lady, after a peaceful pause.

The Captain blew a fragrant cloud. "I fear so, my heart, I fear so," he replied.

Mrs. Cormorant shook her head sadly.

"Yes—it was a mistake. It always is a mistake," agreed her husband.

"You didn't marry me for my money, did you, darling?"

"As it happened, no. Fortunately, when I proposed—in the dark—I did not know you were well-to-do. I loved you, Louise. I think it was your voice that attracted me first of all, then the mystery of you, as you sat half-invisible inside your car—and the moonlight—the romance of it all."

"Ah!" sighed Louise.

"Had I known of your money, no doubt I should have married you for it—being what I am, Heaven help me! But I did not know. Ours, my dear, was an ideal union—a success. Usually a marriage where one party thereto is rich and the other poor is a dismal failure—such as poor Sopley-Smyth's. Almost invariably avarice intervenes!"

Captain Cormorant took a long sip of wine and repeated the last phrase, not without a certain fruity pride: "Avarice intervenes almost invariably."

"You wouldn't let me become avaricious, dear, would you?"

"Never!" said Captain Cormorant reassuringly. "I have seen it break up too many homes ever to permit it to raise its venomous head upon our hearth, darling Louise. It was the only thing I invariably used to advise my clients to guard against, when I was a matrimonial agent."

"Were you a matrimonial agent once, Lester?" inquired Mrs. Cormorant, who was much too well aware of her husband's picturesque and picaresque past to be surprised at this new facet thereof.

The Captain nodded.

"During a period of financial stringency which overtook me through no fault of my own," he replied, "while once residing within the confines of that great republic the United States of America, dearest, I worked up quite an attractively remunerative business as a matrimonial agent. Indeed, I might still be prospering at it had I not been compelled to leave the town somewhat abruptly on account of a misunderstanding with the captain of the local police who had been landed—through me, though entirely by reason of his unbounded avarice—in a position of some considerable difficulty."

The Captain stared into the fire, pulling fiercely at his mustache, his great Roman nose jutting out like a rock.

"He was a most avaricious man—a man who had never shown mercy to a dollar in his life, the hard-hearted hound!" he added. "They used to say he never carried a wallet or a purse."

"But where did he keep his banknotes, Lester?"

"In his soul! That was a joke, of course, dearest—it was what the bootblack said to Mark Twain."

"What happened to make him turn on you so savagely?"

"I will tell you, my jewel," said the captain. "It is an interesting story."

He smiled reminiscently, settled his cozily-slippered feet on a soft hassock by the fender, and launched leisurely into the following narrative:

TO a lady so sagacious as yourself, heart of mine (he began)

it will be obvious that a man who, like myself, is condemned by

the gods to go through life unequipped with morals of any

description, must have his ups and downs. As you know, there was

a period in my career when my family felt itself called upon to

make a determined and united effort to get me out of the country,

and keep me out. At the time I felt hurt about it, but looking

back at it from the peaceful haven which you have created for me,

dear Louise, I feel that it was for the best. I had been forging

my good old father's name to checks rather extensively, Lord help

me! And he realized that we had come to the parting of the ways.

Even that noble woman, my mother, who, with the sole exception of

yourself, was the only woman who ever really understood the curse

under which I am fated to drag out my existence, was compelled to

acknowledge that the time had come when the family must choose

between themselves and me. They chose for themselves.

I landed in America scantily equipped with funds, and, being younger and less experienced at that time, it was not long before my sole worldly wealth consisted of an empty suitcase, the clothes I was wearing, and a manicure set presented to me as a farewell present by my elder sister, who had been given a better one.

I will not conceal from you the fact that I went through a very bad time; so bad that I think only a strictly non-moral man could have survived it. But at length a time came when I found myself fairly established, thanks to my own efforts, as a matrimonial agent in one of the larger towns.

There are those—with you, Louise, at their head, I am glad to say—who consider me at least a gentleman. In my time I have been accused of many peccadilloes, ranging from barratry to arson, but I think I may claim ever to have remembered that I am a gentleman—in manners. Now, manner is essential to a matrimonial agent; without manner no man can succeed in the profession. I succeeded. By the simple device of advertising in one-half of the newspapers that I desired to find a husband for a broad-minded, generous-natured blonde heiress, loving, pleasant, and fond of music,—and in the remaining newspapers that I was seeking a wife for a retired millionaire, young, handsome, dark, fond of home life, and of a surprisingly affectionate nature,—I filled eight large ledgers with applicants, all of whom enclosed the stipulated dollar for a photograph, with the sole exception of a gentleman from Missouri, who explained that he would gladly forward his dollar after he had been afforded an opportunity of satisfying himself visually that the lady actually existed. I had, in short, to show him an available heiress before he detached himself from the dollar for her portrait.

I then paired my applicants off as neatly as possible. I am afraid there were disappointments—particularly among those who could not control their avarice. And there were slight misunderstandings, of course. What sort of misunderstandings, you ask me, my heart? Well, for instance, as when I brought a full-blooded Chippehaha Indian squaw, of mature age, said to be a princess, and to possess a store of precious stones—which turned out to be a collection of Birmingham beads, old glass eyes, and a graduated set of blood alleys—into contact with a high-spirited gentleman from Carolina, one Major Bellew, whose great fortune was locked up in land, the key of the lock being in possession of the mortgagee. I still have the mark of the major's bullet in my arm, but the nails of the Indian princess, I am glad to say, left no permanent scars, deeply though she dug them. But that type of occasional misfire is to be looked for in the matrimonial agency profession—and is one of the reasons why among the privileges which an agent must be content to forgo may be reckoned the privilege of life insurance. No really careful company will entertain a proposal from one of these agents on his own life.

ONE day, while sitting in my office thinking over the problem

of reconciling a literary lady of Boston to the terms of the

contract into which, rather precipitately, she had entered by

mail with an extremely self-made gentleman from Seattle, the

captain of the local police entered the office.

"You're pulled, Montmorency," he said briefly. I was at the time calling myself Montmorency de Fleury, and he meant that I was arrested.

"Why?" I demanded.

"Well, think it out, Mont," he said. "Put yourself in my place for a moment. Here I am, me, Sim M'Gryde, police captain in this town, and a bachelor. And here you are, with a continual stream of heiresses flowing through this office. But, have you ever had the heart to invite me to chip in and collar one of the heftiest ones for myself? Have you? I'm asking you, Mont. Have you acted white to me? Did you ever think whether I was starved for a little love up at home? No, Mont, you never did. You never cared about me setting back there, lonely and poor, in that cold police office. I noticed it and it hurt me, Mont; but I am a proud man, and I set quiet and suffered. Have I ever lifted a finger against you? Have I ever allowed a cop to set' his hoof inside this here Court of Hymen of yourn, Mont? I haven't, and you know it. What about that buck nigger from New Orleans that you offered as a 'brunette gentleman, very cheerful, fond of music, interested in melon-growing and chicken-raising, ample means,' to that prim New England school madam from Gloucester, Massachusetts? I tell you no lie, Mont, when I say that that dame came into my office like a harpoon. She wanted yow pulled then. But did I pull you? No, sir! I said to myself, 'There's old Mont down there settin' down watching 'em file past, with a special eye open for me. First thing I know will be a hurry call from him offering a sweet little dame with, perhaps, half a million good United States dollars to lonely old M'Gryde.' Well, you didn't. And so you're arrested—for fraud! We'd better be getting along to the office."

I thought swiftly, Louise. It is necessary for a matrimonial agent to be a swift thinker. I confess that it seemed to me that M'Gryde's complaint was not without justification. He had been neglected—foolishly. In his place I should have felt much as he did—hurt and resentful. I should have pulled him and had him run out of the town.

I saw it in that light, and I said so.

"Captain," I said, "everything you say is true. I apologize. In the rush of business I have been guilty of a grave faux pas—"

"White conversation," he said. "That goes—it's good enough, and it's enough. Now let's get down to business. How are the heiresses lining up? Have you got plenty? Is there a selection? How are you off for blondes? Do they run large? I like 'em large. Photos, now—let's have a look at their tintypes. Where's the gallery, Mont? Show me round."

It was clear to me that M'Gryde was not at all acquainted with the difficulties of the matrimonial business. Large blonde heiresses do not grow on bushes by the wayside, Louise, and I had nothing whatever resembling one on my books at the time. I was, of course, advertising a pair, but they were quite—er—fictional.

I REFLECTED for a moment, then decided upon a course of

action.

"If you think, Captain, that I am the sort of man who would be satisfied to plant any ordinary blonde item on my books upon you, you misjudge me," I said. "I am going to provide you with something sensational in the way of a wife. She will take some finding—but she's going to be found! All I say is, 'Give me time.'"

He seemed a little disappointed.

"But haven't you got nothing likely in stock, Mont? I want to get married right now—I'm in the mood. And there's a little note of mine falling due next week that's got to be arranged for. How about that amiable heiress with a copper mine, fond of music, auburn-haired, and of a bright, merry, cheerful disposition, that you're advertising? I got no kick against a dame of that kind."

I explained gently that she was not available—that she was, as it were, a shop-window model—a fixture—that there was no such person. That she was, in short, advertising.

M'Gryde was immensely intrigued.

"Huh! I get you," he said. "And every poor fool who would like to hear more of this merry, amiable redhead sends along a dollar for her photo. Say, Mont, it's time I pulled you! But we'll decide what to do about those dollars later. Have you got anything in the heiress way to offer? A small brunette would do, failing a large blonde—but she must have the requisite mazuma."

By "mazuma" he meant money, Louise.

I ran through my ledger. There was nothing available with more than a thousand dollars, and the Captain was rather cold about these. He said so.

"I am not sure that I like this business of yours, Mont," he said. "It's paltry, and it's piking. You'll have to dig up something better than a thousand-dollar heiress for mine—and it calls for quick action. I'll give you a week to find her—the future Mrs. M'Gryde," he said, "and if she aint here sharp on schedule time, you are due for a year or two in the cooler!" He then left.

You'll have to dig up something better than a thousand-

dollar heiress for mine—I'll give you a week to find her.

I do not disguise from you, dear Louise, that for the next hour I sat in my office a prey to deep dejection. I was well aware that I was face to face with a problem so complex and difficult that it would have put a less non-moral man out of business, and almost immediately thereafter out of the town. Quite the last person an eligible blonde American heiress needs assistance from is a matrimonial agent. She is competent to find her own husband, and the lads over there are amply competent to find her—yes, indeed!

Yet here I was, practically bound to produce an extremely wealthy one for the police captain within a week, if I desired to keep on the comfortable side of the local jail.

My thoughts were slowly beginning to flow towards a consideration of that portion of the railway time-table which dealt with departures from the town, when a very remarkable coincidence occurred.

A lady entered the office, and was promptly shown in by my clerk.

She was, I perceived at a glance, a large blonde, and although past the first flush (and, indeed, the second flush) of youth, she was what one might quite reasonably term a well-preserved and comparatively handsome woman. She was dressed well, in expensive though not exuberant clothes, and her manner was extraordinarily self-possessed. An interview with a matrimonial agent is an uncommonly good test of self-possession, Louise.

She settled herself comfortably in the chair which I placed for her at my desk, and for a few seconds surveyed me in silence.

I saw anew that she had once been an extremely beautiful woman, though the considerable remnants of her once dazzling loveliness were marred slightly by a certain austerity or severity—I may even say, hardness—of the eyes and mouth, and a small, peculiarly-shaped scar on her left cheekbone. It was almost a perfect crescent. I became aware of a feeling that she was wealthier than the usual run of my lady clients. Upon the whole, she made an excellent impression upon me—excellent. She would make—in spite of that faintly chilling severity, that hint of fierceness—an admirable wife for a high-spirited man.

HER impression of me must have been favorable, for her

peculiar, rather mysterious and vaguely alluring almond-shaped

eyes brightened a little as she looked at me. She smiled

faintly.

"You are Mr. de Fleury?" she inquired.

"Entirely at your service, mademoiselle," I said, with a certain courtliness. I felt that a degree of courtliness would not be wholly out of place—and, of course, dear Louise, a matrimonial agent would never dream of using any mode of address but "mademoiselle" to a lady client at first glance—even though she were obviously most excessively married.

"I am Eleanora Colone," she said, in a carelessly impressive way. She placed a gold net handbag of obvious worth on my desk, and looked at me attentively. I had never heard of her in my life, but I confess that I felt that I should have done so. That she was a stranger to the town, I knew, of course.

"No doubt you will think it singular that I should avail myself of the service of a matrimonial agent in the matter of selecting another husband—for I am a widow, as probably you are very well aware—and I desire it to be clearly understood that, whatever my reasons, I do not propose to reveal or discuss them," she said.

I murmured an appreciation of what I believe I spoke of as "a very natural inclination" and she nodded.

"I desire to marry again," she said imperiously, "and, because of the reasons to which I have alluded, I am not disposed to be too critical. I prefer a man of tall, distinguished appearance, with good manners, and some knowledge of the usages of polite society. He need not be strictly handsome, and I do not wish a man who is popular, and who possesses shoals of friends. Money is of no consequence whatever. He may be poor, but that will be of no importance—though, as a guarantee of his integrity and honesty of purpose, I shall require that he insures his life to an extent compatible with his position as my husband. And he must be prepared to change his name, should he possess one which grates on my ear or jars my sense of harmony. That, I think, is all."

She paused, and surveyed me keenly.

"Are you married?" she asked calmly.

I reflected swiftly. It was quite clear that I could, with. perfect propriety, regard the inquiry as a proposal—but, for some indefinable reason, I hesitated. Was it some strange, sweet presentiment of you, dear Louise, that rose to the surface of my mind? I have often wondered. But my hesitation saved me.

It was not complimentary, I fear—certainly it was not very courtly—and a momentary expression of intense anger, so fierce, so hard and even terrible, flashed across her face, that, mentally shaking hands with myself, I made haste to answer. I rose and bowed with that courtly, old-world grace which, as you have often been so kind as to say, Louise, is one of my more attractive attributes.

"Alas, dear lady, I grieve to say that my personal matrimonial affairs are in a state of such intricate and incredibly involved complication that he would be a bold man who could say offhand whether I am married, half-married, divorced, semi-divorced, a widower, or single. A curious position of affairs, you will say, for a matrimonial agent, and indeed you will be right. But you are no doubt familiar with the classic phrase of the great clown Garabimaldi (I fear I came a cropper over the name), 'I can make other people laugh, but I cannot laugh myself!' So, madame, it is with me. I can dispense matrimony from this office with a lavish hand—I can even control (to a limited extent, and for a limited time) the marriages and matrimonial affairs of others—but my own matrimonial affair I cannot control, for she is uncontrollable."

I bowed even lower.

"Madame," I said, not without a careful, rather touching tremor of the voice, "your proposal falls upon the wounded spirit of a man who dares not in business hours wear his heart upon his' sleeve; like the gentle dew from above, your generous pity and compassion bathes in the Lethean waters of Love, as in an anodyne—nay, a very nepenthe—"

"Yes, yes, I understand," she said briskly. "You may forget it, Mr. Fleury. It was the merest passing inquiry, and the matter is devoid of the slightest importance. Let us proceed with business. What available clients have you?"

I TOOK my heart off my sleeve, put it in my pocket, so to

speak, Louise, and we proceeded to business.

I ventured to inquire as to the lady's means. She responded with a list of investments—mining stock, mostly, which convinced me that even if they were all untamable "wildcats" the mere paper on which her share certificates were printed was worth a considerable sum to any paper-maker for re-pulping—and in my mind's eye I married her at once to Captain M'Gryde.

You see, in some respects, he answered rather uncannily well to specifications. True, he was not tall. Indeed he was one of the squat, oblate ones. Nor was he distinguished—except for the astonishing liberality of his feet. But, on the other hand, I have seldom met a man who struggled along with less popularity—his nickname, which was "Blight" M'Gryde, conveys that to you—and he had shoals of the kind of friends who would cheerfully lead him over the cliff if he were blind, but none of the other kind.

He was poor, and always would be in any place where he could spend money on himself. And I did not doubt that he would willingly insure his life. If the policy lapsed because a rich wife failed to keep it paid up, Captain M'Gryde was not the kind of man to worry himself into chronic insomnia on that account.

Yes, I saw it with a thrill. They were made for each other—and both for me! I proceeded to describe the police captain.

Mrs. Colone was immensely interested. She 'even went so far as to say that if her unalterable decision that her husband should be insured for at least a hundred thousand dollars pressed too hardly upon the Captain's resources, she would be prepared occasionally to pay his premiums for him—if he were otherwise tractable.

I arranged, then, as to the extent of my own personal rake-off—er—fees, you understand, Louise, and, leaving her for a moment, went to fetch the Captain. I did not use the telephone, though there was one on my desk. I told Mrs. Colone—and she agreed—that to my mind the introduction of machinery into such delicate matters was apt to render the negotiations sordid, if not positively base. Besides, there was the question of my rake-off, small though it would be (if any at all) from M'Gryde. Of this I did not speak.

Hastily driving from his presence a minor malefactor who had been explaining an infringement of the by-laws relating to the peddling of monkey-nuts, and thrusting the explanation into his pocket without troubling to count it, M'Gryde came with me to my office.

I need not say that by the time I had recited half the list of the lady's investments and her other charms, he was willing to swallow all her very reasonable stipulations whole, and even to ask for more to show his good faith.

The thing went with a swing from the start. M'Gryde, perhaps more accustomed to a certain severity of look than was I,—though, as a matrimonial agent, I, too, did not lack experience of the glassy gaze, nay, the crystalline stare of some of my less happy endings—appeared to notice nothing but a gentle and tender beauty upon the countenance of the gracious Eleanora, and, neither being inclined to display a niggling fastidiousness, the preliminaries were speedily settled.

The thing went with a swing from the start.

The preliminaries were speedily settled.

Both parties scrupulously carried out their obligations—I achieved a very sweet little rake-off on the first premium of the large life-insurance policy—and a few days later the marriage took place, very quietly, at the request of the bride.

Owing to a sudden rather important arrest, M'Gryde was not able to leave the town at once for his honeymoon trip.

IN the evening following the marriage I worked late at my

office thinking out the particulars of a new and rather promising

type of heiress I had been building up in my mind for some time

past, and writing a new and brilliant advertisement offering her.

I remember to this day the glowing though hopelessly unmoral

thrill of joy sent coursing through my mind by the reflection

that she would stand at least a two-dollar photograph fee.

I completed my work and, locking up the office, strolled down to the newspaper office with the advertisement.

The last edition was published just as I arrived—and I admit to you, Louise, that my vertebrae changed gear and froze in the reverse when my eyes fell on the "star" story of that last edition. I wont harrow your gentle heart, Louise, with the details. Let it suffice to say that the rag had devoted half its entire space to a detailed account, not of the police captain's wedding—but of his bride.

I had guessed her to be distinguished—and she was—notorious, in fact.

She was the famous Belle Tone—the only woman on earth who had been twice tried for her life on the capital charge of murdering her husband—the motive in each case being the heavy life-insurance of the husband.

The first trial—on account of the first husband—had taken place in Scotland, The verdict had been "not proven." The second trial had been in Paris, and four juries had disagreed. Her first husband had been a Scotch inspector of police, her second husband had been a lieutenant of the French police. Both had been insured for a sum equivalent to about one hundred thousand dollars, and both had died very suddenly.

The deciding factor which had saved her was the allegation that shortly prior to the fate of both husbands, a mysterious person, a man of "pronounced Oriental appearance," had inquired the way to the house of the lady; but this person had never been discovered.

The newspaper reporter claimed to have recognized her by the scar on her cheek.

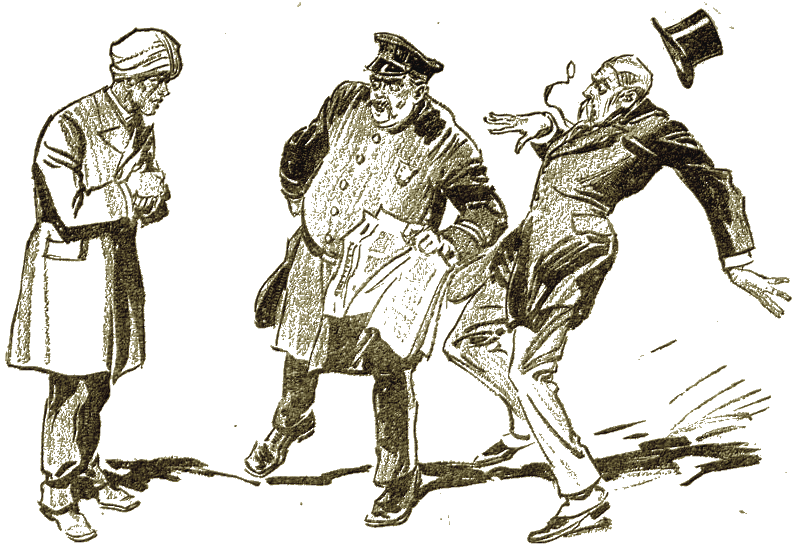

You can well believe, Louise, that I devoured the extraordinary news. Suddenly, as I stood at the door reading avidly, the paper was snatched from my hand and I looked up with a start.

It was M'Gryde, from the police office almost opposite, and it was evident that he had read the news.

He glared at me, blue-black with either passion or fear, I never quite knew which. He opened his mouth, but whatever he was about to say was never spoken. For at that moment a passer-by stopped.

"Pardon me," he said, in a curious lisping voice. "I should be grateful if one of you gentlemen could direct me to the house of Mrs. M'Gryde."

"I should be grateful if one of you gentlemen

could direct me to the house of Mrs. M'Gryde."

M'Gryde gasped, staring. Then without a word he turned and dashed, comet-like, across the street toward his office.

Not till he disappeared inside did I look at the passer-by.

"Go right along, and ask again," I said; and simultaneously I left him and went out of the matrimonial agency business for good.

There was an eastbound train just pulling out, when a second and a half later I reached the railway-station.

I connected with that train, thus beginning my non-stop run to New York, en route for England. Why, do you ask, Louise?

Well, heart of mine, the person who had wished to be told the way to Mrs. M'Gryde's was a person of most extraordinarily pronounced Oriental appearance, and his arrival conveyed to me what the cry of the banshee is said to convey to those who hear it.

M'Gryde, dearest? I have never seen him since; but, long after, I learned that he, too, tried for the train which bore me away.

He missed it by half a second, but a second later he was aboard a fast freight which was heading westwards, and which he did not leave until he was on the other side of the Rocky Mountains! He, too, was a man of quick decisions.

THE CAPTAIN glanced at the clock, finished his port, and

rose.

"Ah, Lester, what a romantic career you have had!" sighed Louise, gazing up at him admiringly.

"Yes, my heart, very romantic, and crowned at the end of it with that priceless boon, a perfect wife, with a disposition of pure gold. That is the bright, particular star which illumines the profound gloom which, owing to my affliction, would otherwise enshroud the sunset, so to speak, of my life!"

He sighed.

"Ah, well, I suppose the boys will take it as unkind if I do not look in on them at the club for a half-hour. Go to bed, dear heart, and rest. I would not rob you of one instant's necessary slumber."

He kissed her affectionately, then drew out a little loose silver and looked at it with an air of chagrined discovery.

"By Jove, Louise, I am short—very, short! Heaven forgive me, but have you a fiver handy, darling?"

Mrs. Cormorant almost ran to her desk,

"Nobody shall ever say that I am like that Mrs. Sopley-Smyth," she declared.

"Not in my hearing!" said the Captain fiercely, putting the fiver in his pocket. He kissed her again, lighted her candle, and gallantly escorting her to the foot of the stairs, bade her a tender "au revoir."

"A good little soul!" he mused as he let himself out. "She must always be kept happy. Probably the only person in the world who believes in me, God bless her! Yes, she has faith in her husband—poor wretch that I am," he continued, smiling cheerfully, as he felt for his cigar-case. "And that is the great essential to all wifely happiness, devil a doubt of it: Faith in one's husband—and plenty of ready money to back faith up! Yes, indeed!" And, striking a match, the Captain sauntered comfortably clubward.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.