RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

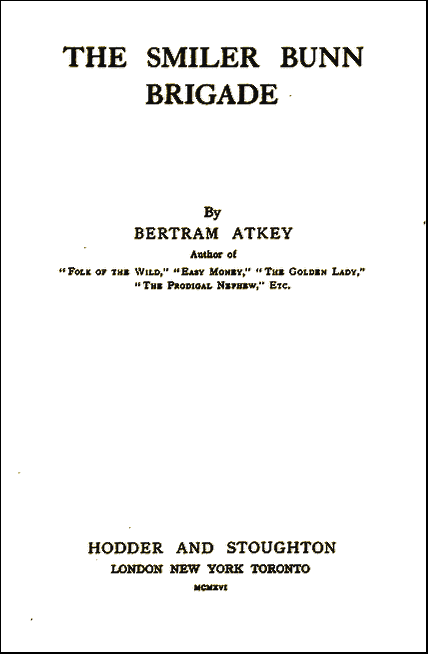

"The Smiler Bunn Brigade," Hodder & Stoughton, 1916"

"The Smiler Bunn Brigade," Hodder & Stoughton, 1916"

This account of the exploits of Smiler Bunn and his cronies behind German lines during the First World War is an episodic novelisation of 12 short stories published in The Grand Magazine from May 1915 to April 1916.

The stories were published under the titles:

1. The Man from Krupp's (May 1915)

2. The Academy for Traitors (Jun 1915)

3. A Circumstance of War (Jul 1915)

4. The Amazons of the Crypt (Aug 1915)

5. The Prey of the War Hawks (Sep 1915)

6. The Trial by Terror (Oct 1915)

7. The Nodding Man (Nov 1915)

8. "Howitzer No. 8" (Dec 1915)

9. The War-Hound Patrol (Jan 1916)

10. The Salamander (Feb 1916)

11. The Crucified Man (Mar 1916)

12. The Tunnel and the Well (Apr 1916)

The first eleven chapters of the novelisation bear the same titles as the stories in The Grand Magazine. The twelfth has been retitled "Germany All Over—Down and Out."

From a letter written by Mr. J. Raymond Carey, in London, to his friend and partner Mr. Kane Kilnoun, of Messrs. Carey & Kilnoun, Ivory and Produce Factors, at Livingstone, Rhodesia.

...it's put a year or two on to my age and a lock or two of white into my curls. However, we all broke about even except perhaps the little Dutch guide who was more than ready for a long rest when we left him. The other men were a couple of brace of very queer birds. One was a sort of Mahommedan, a secretary or something of that kind to the Rajah of Jolapore. As smooth as a porpoise and about the same size, with the morals of a crocodile, but a fighter all the time. He was calling himself Mirza Khan through this business, but I don't think names worry him much, anyway. He turned out to be an old friend of the others—I fancy they had been mixed up together in some pretty complex transactions in the past. The others were a pair of highly competent cocks called Wilton Flood and Henry Black, with Flood's valet, a Chink, and the most capable Chink I ever saw—and I've seen a few.[*]

[* "Wilton Flood" and "Henry Black," it will be remembered by those who remember such things, were the names adopted for good and sufficient reasons by Messrs. Smiler Bunn and Lord Fortworth at critical moments in their respective careers.]

Flood and Black were good chaps to have next to one in a bad country, but they aren't ordinary cards. Over here they live like millionaires and what they don't know about making themselves comfortable no man on earth can teach them. I've got no right to describe them as crooks, but my impression is that they are the two men who never let anything get past them. They're human Nets—rat-traps, so to speak. From what I can gather—and they give very little away—they make a speciality of hawking for hawks. They find a "crook" at work and they let him finish—but when he has finished he finds that the plunder has somehow or other got completely past him—into the Nets. They tell some queer stories. Personally I like the blackguards—all of 'em. They make me laugh. Flood and his pal talk of visiting us some time in Rhodesia. You will get on with them. They'll amuse you. But bury the cash-box before they arrive...

THE head waiter, a fat Bavarian with a hard eye, a large circular figure and an extraordinarily insincere manner, rather skilfully wrung his mouth into a smile and approached the table at which sat those middle-aged and experienced chevaliers d'industrie, Mr. "Smiler" Bunn and ex-Lord Fortworth, though these were by no means the names under which they circulated among humanity now. Mr. Bunn, for reasons which no doubt were entirely satisfactory to himself, was Mr. Wilton Flood, and ever since his gigantic financial failure, involving that of the many companies he had created, Lord Fortworth, that dour and self-made man, had abandoned his title in favour of the humbler and less noticeable name of Black—Mr. Henry Black, a gentleman of private means.

The head waiter gutturally expressed the hope that the lunch had been satisfactory.

"Yes—to you," replied Mr. Bunn, shortly, finishing his liqueur. He had never liked German hotels, and German waiters he liked even less.

The head waiter bowed a stiff, jerky little bow, like a man who has tried to climb over his own stomach but has slipped back, and said, in remarkably good English, that he did not understand. It seemed to Mr. Bunn that under the smooth deference acquired during a lifetime's looking out for tips, there was the suggestion of a sneer in the man's voice. Smiler flushed slightly, and fastened a pair of grey and flinty eyes upon the waiter.

"What I mean to say is that the price of the lunch is satisfactory to you, but that the food was garbage, practically speaking. It was the sort of stuff that only a man who has been starved at Homburg would have the heart to discourage his digestion with. The fish was the best of the lot—and it was the poorest fish I've ever tasted. Carp, wasn't it?" He consulted the menu again. "Yes—carp. Well, now, if I had my way, my lad, I would have carp blotted off the face of the earth, and rendered extinct. That's what, Squire. For it's a poor fish at the best of times—the poorest of fish, in fact. Very suitable for vultures or mud-hawks, I should say, but not suitable for human consumption—the way your chef turns it out. Ain't that right, Black?"

He turned to ex-Lord Fortworth for corroboration.

"They feed it to pelicans at Zoological Gardens in most countries," said that individual with sulky candour.

"Carp!" continued Mr. Bunn, evidently warming to his subject, and staring very intently at the apparently hypnotised head-waiter. "What is this carp, anyway? Man alive, even old Izaak Walton, a man who's forgotten more than you or your chef ever knew about cooking fish, and who had a good word to say for very nearly every fish that swims, always seems to me to have his doubts about these carp! Listen here! I know his recipe by heart. He says in his book—I'm telling you this for your own good, Squire, understand—he says, 'Take a carp, alive if possible, scour him and rub him clean with water and salt, but scale him not'—understand that, scale him not—'then open him and put him with his blood and liver into a small pot, then take'—listen to this, now, it's literature,—'then take sweet marjoram, thyme, and parsley, of each half a handful, a sprig of rosemary and another of savory, bind them into two or three small bundles, and put them to your carp, with four or five whole onions, twenty pickled oysters and three anchovies.' Don't overlook the anchovies, mind, for I've always said, and shall always maintain, that anchovies are Godsends to mankind."

Several immensely interested and extremely full-fed Germans, one of them an infantry officer, who had gathered round nodded solemnly.

"'Then,'" continued Mr. Bunn, affably, and not without pride, "'then pour upon your carp as much claret as will cover him and season your claret well with salt, cloves and mace, and the rinds of oranges and lemons: that done, cover your pot and set it on a quick fire, till it be sufficiently boiled; then take out the carp and lay it with the broth into the dish and pour upon it a quarter of a pound of the best fresh butter melted and beaten with half a dozen spoonfuls of the broth, the yolks of two or three eggs, and some of the herbs shred; garnish your dish with lemons and so serve it up, and much good do you!'... Now, that's the recipe—and what I want you to notice is the last few words 'much good do you!' He means that sarcastically, Walton does. Anybody can see that if they've got their lamps trimmed. The man gives you a recipe with half a dozen expensive things thrown in and a lot of work and careful cooking and yet at the end of it he says, 'and much good do you!' Practically speaking, it's the same as saying 'and be damned to you!' To my mind, that's a pretty sure sign of what he really thinks of carp. And I'll confess, gentlemen, that I think the same—it's a poor fish and has spoiled many a lunch—"

He broke off abruptly as the German officer, who had withdrawn a little from the group to read a telegram he had just received, gave a sudden, thick exclamation:

"Kriegsmobilmachung!"

In an instant he was surrounded and a hoarse clamour of questions burst out about him. He clutched the telegram in both hands, like a man holding a newspaper, and held it before the ring of flushed, excited faces that hemmed him in. There was only the one word upon it:

"Kriegsmobilmachung!"

Neither Mr. Bunn nor Lord Fortworth was a German scholar, nor did either possess the least desire to be, but both understood enough of the language to know the meaning of the word on the telegram. It was the order to mobilise for war—and all the wires in Germany were humming with it.

They shot a glance at each other. And it was no longer the tranquil, sleepy glance of two men of comfortable habits and generous ideas, gourmets, indeed, who have just lunched—badly, perhaps, but still sufficiently. Their expressions now were about as sleepy as those of a couple of wise and crafty old wolves who, basking in some sunny jungle fastness suddenly have scented, on the wind, the taint of some approaching danger.

Germany was mobilising for war!

They knew what that meant, without consulting encyclopedias.

Men such as Mr. Bunn and ex-Lord Fortworth do not look upon peoples, their customs and their environment, from quite the same angle as the average traveller. For, since it was to the weaknesses and lack of suspicion and preparedness of the wealthier units of humanity, that the two old tigers looked to provide them with the means of luxurious existence, naturally they were infinitely more observant than the ordinary tourist or Homburg water drinker.

When they travelled in Germany they were, by force of habit, on the look-out for a different kind of scenery from hills, valleys, and quaint buildings. The scenery they most appreciated, and, indeed, sought for, was what they described as "the yellow, round scenery which has a milled edge and looks best in a man's bank account." Nothing but the keenest observation will disclose this kind of scenery to men who seek, and years of perpetual searching had ingrained in the Bunn-Fortworth Combine powers of observation which let nothing escape. So that scores of things seen (and mechanically noted) during the previous month suddenly rose up before their minds' eyes and helped to hint to them what sort of a place Germany was likely to be from then onwards.

Smiler Bunn leaned over to Fortworth, speaking in a low, tense voice.

"Here she comes, Fortworth—in all her glory. I can hear her coming!" His eyes gleamed with excitement.

"She? Who's she?" growled Fortworth.

"European War, my lad. The world has flirted with her for so long that the lady's come to see whether we're in earnest. There'll be a million men on the French frontier within forty hours—and another million a day later—if they aren't there already—"

A burst of frenzied cheering interrupted him. They turned swiftly and saw that the cheers were for the officer who had left the hotel terrace upon which lunch had been served and was clambering into a small motor car, presumably going, as fast as he could travel, to join his regiment, probably quartered close by.

The partners listened for a few seconds, watching the crazy joy and excitement on the faces of the people.

"They mean having it this time, Fortworth," said Smiler, very seriously. "Look at 'em! They're like pigs round a trough! And now, what about us? It ain't going to be any smoking concert for the Englishman who gets left in this country when England waltzes in—take it from me, Fortworth! It's the frontier for us about as fast as Sing Song can shove the car along."

Fortworth gave a sullen sort of grin.

"The roads to the frontier are going to be jammed bung-full of men and supplies from now onwards," he said.

Mr. Bunn pondered.

"Well, the railways will already be under military control, and there won't be room for half the people that will want a ride to the frontier. How about it? It's either road or rail—we can't swim for it, nor fly."

He was staring at his partner with corrugated brows.

"And what about Wesel?" he asked. "Are we going to let that man-killing goat get past us, with his wonderful explosive, while we skate away to the frontier, or what?"

"Wesel? Oh, well, Wesel goes up in the air as far as we're concerned, Flood. This country is probably under martial law already, or will be in about a minute and a half. It's no place for a crook, old man, now."

"Perhaps not. But here's this man Wesel with a formula worth, so he says, millions. More, very likely, from the way he's been quietly bragging about it to us. Surely we can get hold of it before we get away? I'll own that the frontier looks good to me, just along now, Fortworth, and I'll eat a magnum alive the moment I cross it—but we've got to get that formula out of Mr. Wesel first, some way or—"

He broke off, as the herd of Germans surged back to their table. For an instant the partners misunderstood, and it was significant how, a sudden ugly light in their eyes, the hands of the two adventurers glided simultaneously under their coats. But they were withdrawn empty a second later, as the people, gasping with excitement, demanded the privileges of shaking hands with the "dear, good Americans," and of asking their opinions as to war in general and the probable attitude of the United States in particular.

It was only then that "the dear good Americans" remembered that they had been passing as New Yorkers, mainly, be it said, with a view to more easily dealing with one Mr. Auguste Wesel, a German-American inventor whom they had met at the hotel two days before, and of whom more will be heard later.

But the partners had hardly begun to explain their views upon the probable attitude of the United States, before the crowd left them abruptly in order to cheer a regiment of heavy cavalry that was marching by, en route to the frontier.

The partners remained where they were. Not till they had finished enjoying their cigars was anything short of a bomb likely to shift them, for they were too old and too wise to ruin a good cigar by prancing all over the place in order to see German soldiers on the march. They would see enough of them before they got back to London—more than enough, probably—and were perfectly well aware of the fact.

Presently, sitting like rocks amid the raucous crowd, they finished their cigars, and, leisurely enough, rose to go to their sitting room where they could discuss matters without any possibility of an audience.

But they had hardly arrived there before the person who described himself as their courier—a small, quick-eyed, homeless-looking individual who called himself a Dutchman, but looked like a little of everything, and who appeared to know every inch of Germany by heart—arrived also, declaring in a somewhat agitated manner that Germany was a good place to get out of without delay.

"If you do not go now quickly," he asserted, "perhaps you will not go until the end of the war, and God knows when that will be," he said.

"Why, my lad?" demanded Mr. Bunn. "If the United States doesn't go to war with Germany we shall be all right."

The courier—he said his name was Sweern, Carl Sweern—shook his head, in violent disagreement.

"No, sirs—that is badly wrong. You are not understanding. Germany will fight this war differently from all the wars. She will fight—" he dropped his voice—"like mad beasts. It is arranged for that manner. There are some who know that extremely—I know it. It may be right that America will not fight, but by thinking that Germany will be a comfortable country for two Americans—without passports, sirs—then you are perfectly wrong. There will be the spy huntings—and madnesses—what do you call it?—a mania, yes. And if there is only a little suspicion of you then you will be made prisoners. Even if enquiries of friends from America came about you, the Germans would not care nothing for that. They would lie. You don't believe that—but you will see it some day soon."

The partners looked at each other.

"How about it, Black?" demanded Mr. Bunn. "Do we skip for the frontier?"

"Moreover, sirs, you have not passports. Your cards have not American address. Your motor car is the English Rolls-Royce. You look to the eyes, and you talk by accent, like Englishmen, and this will be a wicked country for Englishmen when England declares war."

"What are you driving at, Carl, my lad? Are you trying to hint that we are not Americans?" asked Mr. Bunn, scowling.

"I know you are Englishmen—that is all right—though most of these German swine believe, as yet, that you are citizens of the United States," said Sweern, very softly.

They regarded him silently, for a moment.

"But you can perfectly trust me," continued the guide in a whisper. "I despise all Germans more bitterly as anyone of the world—and I hope this war to destroy their nickel-plate Empire. I know them and of their ways of the fighting they mean to use and I advise you, sirs, for safety, to get out before they seize your car."

Mr. Bunn looked a little flushed and his jaw was sticking out,—as was that of ex-Lord Fortworth.

"Well, you seem to have got us weighed up pretty thoroughly. I've always understood, though, that you Dutch were practical folk when it comes to standing clear of trouble—" began Smiler, but broke off as the door opened noiselessly, and a person in leathery raiment, with a face as yellow as a counterfeit guinea, and as plain as a pike's, slid in, absolutely without sound.

It was Sing Song (so christened by his master), the gentle Chinese valet, cook, chauffeur, pirate, and all-round baggage-dromedary of Mr. Bunn. His face was less expressive than the end of a brick, but there was a gleam in his beady eyes that Mr. Bunn knew of old.

"What d'you want, you orange?" enquired Smiler, abruptly.

"Plitty quick wal coming, mastel. You wantee cal plitty soon you telling me quick. Plentee soldiels bin lookee at cal, talkee allee same commandeeling cal, mastel. Plitty good job slippee away home!" said the saffron rascal, blandly.

The partners stared at him, in speechless disgust.

"Commandeer the car!"

"Oh, yes—military requisition, you know, sirs. The railways have already been taken over by the military—they will next seize all the cars," said Sweern, corroborating Sing Song.

"Oh, will they—blast 'em!" bawled Mr. Bunn, furiously. "Well, look here, Sweern, you hike away down to the garage, wherever it is, and warn 'em off as long as you can. Tell 'em it's American property—if that's any good. Paint the Stars and Stripes on the panels. Fix it up as well as you can, and come back here. We want a talk with you."

Sweern bowed politely, and removed himself abruptly from the room.

"Sing Song, you go and find Mr. Wesel. Give him our compliments, and ask him if he can spare us a few moments on urgent business."

Sing Song departed and Smiler turned to his sullen comrade.

"It's going to be quick work,—against time, you may say. If we pull it off at all. But I don't mind saying I want to get Mr. Thundering Wesel's formula—and his wad, if he's got one—about ten times as much as I ever wanted anything. This country has had a lot of good money out of us, Fortworth, and I want to snare some of theirs before we get out."

"Yes, you always were a hungry sort of a wolf, Flood," said Fortworth. "And it will about be the ruin of you—and all of us. We might get what we want, I know, but if you ask me for my own candid opinion I consider that we're far more likely to get a bayonet apiece in our bow-windows. You're grabbing for something that's out of your reach, Flood. But so be it. Have your own way."

Mr. Bunn looked pained.

"I am no wolf, Fortworth. And I can prove it, if necessary. There's nothing greedy or wolfy about getting away with Wesel's wad and his explosive formula. It ain't greediness—it's patriotic. You've got to remember that the wad we shall take or capture from an enemy we shall spend in England, and the formula, if it is any good, we shall sell to—"

"Pardon, monsieur,—to me, I trust!" chimed in a voice behind them—a musical, feminine voice.

The partners started violently, and turned towards the door like two fat acrobats.

A woman had come into the room so quietly that they had not heard or suspected her entrance—a very well-dressed and beautiful woman, who stood smiling faintly upon them.

They had never seen her before, but they were more than willing to waive that. Neither Mr. Bunn nor Lord Fortworth possessed any distaste for a pretty lady especially when, like this one, she had heard more than she ought. They rose, like one man.

She closed the door quietly, and advanced, smiling.

"Ah, monsieur, you talk so distinctly! With such boldness!" she said to Mr. Bunn.

Clearly, she was tactful as well as beautiful. Nine people out of ten would have described Mr. Bunn's voice as too loud, and so have offended him.

"I heard your plans, even with the door closed," she said, and in spite of the fact that her own voice was so low as to be little more than a whisper, there was a faint, far echo of warning in it that made the comrades look thoughtful.

"In such times as these," she said, "not only the walls, but the ceiling and the floor, even the furniture, of a German hotel have ears—and eyes."

"Well, mademoiselle—" began Smiler, but she shook her head quickly.

"Not 'mademoiselle.' I am a German. Remember that, above all things. I am not French. My name is Vogel, and my husband and I live in this town. And I have come to discuss with you the matter of the secret explosive, the formula of which Mr. Wesel has come to Germany to sell."

"Yes?" said Smiler, enquiringly.

"There is the danger of making a terrible mistake and losing everything—if we do not discuss it," said the lady.

The partners nodded slowly.

"If you say so, we don't doubt it—do we, Flood?" said Fortworth, politely.

"Certainly not," replied Smiler, airily, "so let's discuss it. What are you proposing to do about it, my dear Mrs. Vogel?"

She shot him the glance of a woman who knows men by heart, smiled slightly, and took a chair between them.

"I will explain to you—mes amis!" she said in her velvet whisper.

They knew her nationality then—as she had intended them to, after warning them that ostensibly she was German—and, a second later, were aware of her profession.

She was a French spy—and probably a brilliant one. Only an extremely brilliant or extremely foolish person would have dealt so openly with two strangers—and no Secret Service has any use for foolish agents.

"From the moment when he left New York, a month ago, this man Wesel has been watched," said the lady who wished to be known as Mrs. Vogel. "Perhaps you two English gentlemen adventurers—it is better for us to understand each other, is it not?—thought, until now, that you were the only ones interested in Mr. Wesel? That is not so. France is interested in him also—watches over him, very carefully, so carefully that she has detailed one of her best agents—c'est moi, mes amis—to watch over him, and, at the right time, to procure his secret."

She smiled at them charmingly, and, despite her frankness the partners warmed to her.

"Do you mean to say, my dear, that you're pulling this off alone?" demanded Smiler.

"Oh, yes—except for one who is coming to-night—to deal with Wesel."

Under the soft voice flickered, as it were, a gleam of cold steel. It did not escape the attention of the partners.

"Deal with him?" enquired Smiler, doubtfully.

She nodded.

"To become exclusively possessed of his secret," she said—very gently and softly, but under it was still that faint, sinister steely ring.

"Oh, I see. You mean to exclude us from sharing in this secret?"

"You, of course—and Wesel also—"

"Wesel? How can you? Suppose he knows his formula by heart?"

She did not answer—merely shrugged her shoulders.

But there was a significance in the gesture that startled them. Their faces hardened.

"But, my dear lady, you don't propose to murder this man after getting his secret, so that he shall not give it away to Germany?"

It was, as Mr. Bunn said afterwards, a plain question and one which demanded a plain answer, and they got it.

Her face, too, hardened suddenly, and went white. And there gleamed in her blue eyes a wild and brilliant light.

"Listen, gentlemen!" she said, quietly. They listened.

It seemed, for a moment, very silent in that room, but, as they listened, they heard a sound that bore down that artificial silence—a deep, dull, regular sound—a mighty sound—the tramping of many feet. The marching of an Army!

They were to grow familiar with that dull, and sullen sound before many days even as men during an unsettled summer may grow almost used to the growl and mutter of thunder—but now, hearing it for the first time, it troubled them.

"Kriegsmobilmachung!" said the woman, pale, but with ruthless eyes. "The Armies of the German Empire are en route! To France—by way of Belgium. There will be no more negotiations, now. That is past—done with. The diplomats of the nations can stand aside now—fold their hands—their work, good or bad, is finished. Gentlemen, it is the hour before the dawn of The Day—of Armageddon!"

She was leaning to them, speaking in a low, incisive whisper, white as marble, but vital as flame.

"There is no power on earth that could hold them back now—not even their mad Emperor! This is no such affair as Agadir. It is War! France is alert and seething—Russia is arming—already England has flung her great battle fleets, cleared for action, into the North Sea! And the German army is marching to make an altar to their own gods of Belgium. God pity the men of Liège—that will be the first rock upon which the tide will beat. Listen, I say! Those that you hear tramping are not a thousandth of the armed myriads that this insane country is hurling across her frontiers!"

A deeper rumbling was heard, and the hotel seemed to vibrate to its foundations.

"Do you feel that? It is one of their guns—their great guns—and the engines that drag them. Monsters of steel—they were built in secret, but we know—and we pin our faith to the good 'soixante-quinze'—as you British to your giant naval guns!"

She controlled herself with an effort, and the brilliance died down in her eyes.

"I am a Frenchwoman and emotional—sometimes," she whispered, with a sort of cold naïveté. "Forget that, if you please! They—" a scarcely perceptible gesture indicated the unseen marching men,—"go to their doom, I know that. You will see it if you live so long.... Yes, the man Wesel must die. War, the Germans say, is war. Good! We will make it so! Do you think then that we shall allow a German who himself has stolen a secret to remain in possession of his stolen knowledge after we have bought his formula? That cannot be, gentlemen. To-night Wesel sells his secret to one whom he believes to be a man from Essen—an expert from Krupp's! But that man will not be from Essen—he will be a French secret agent—the best of us all—ah! so brilliant!—and he will buy the formula for France—for the Allies! For your country—your England also, gentlemen! Remember that! If we buy the formula and let this man go, how long would it be before he learned that unwittingly he had sold it to a French agent instead of a man genuinely from Krupp's? A day? Two days? A little more, perhaps—but not long. And what then? Would he not sell it again—this time to Germany?... Yes. The question answers itself, my friends. You must leave Wesel to us."

She paused for a moment watching them keenly. Then she smiled slightly and continued.

"You will not give up your plan to take the secret for yourselves if you can?" she said. "It is a coup that you are resolved to make. Yes, I see that. And I can guess that you are capable and dangerous men—chevaliers d'industrie. And clever, for you are so rich and it is not easy to become rich by living upon one's wits. And I know that you are well-served."

This was a side-swing at Sing Song, the Chinaman.

"You seem to have kept a sharp lamp out on us!" said Mr. Bunn, rather curtly.

She waved a hand.

"Oh, a little watching and enquiry—no more. We have opportunities you do not guess at. One learns to judge men," she said, airily. "You two great big Englishmen are honest—in an unconventional way. Do you think I would have told you what I have told you if I had not been quite sure of that?"

The partners glanced at each other.

"But, after all, she's told us nothing but what she told us," said Fortworth bluntly. "We don't know that what she's told us is all she knows. Is what she has told us enough to call us off Wesel?"

Smiler Bunn turned to the lady.

"You hear what my partner says," he said. "I like you—I don't deny that you appeal to me—I don't mind saying you are just my style—but I think it's as he says. It's a good tale you've told us—and it hangs together. But if we were in the habit of allowing ourselves to be pushed off our fair game by an emotional short story every time, we should have starved a thousand years ago. That's not rudeness, though it sounds rude—it's the compressed truth, and that nearly always does sound rude."

They watched her carefully, but she only smiled.

"I understand," she said. "And I am prepared to make compensation. This matter is so delicate and so grave that we can tolerate no risk of failure. If you make an attempt upon Wesel that fails, then he may become suspicious and leave here and go to Essen or Berlin and negotiate there. It is for that reason we wish you to abandon your plan. He must not be alarmed. And, to prevent that, we are willing to pay."

The partners nodded gently.

"Let's get it right," said Mr. Bunn. "You are willing to pay us to leave Wesel's secret alone, not because you think we shall succeed, but because you are afraid we shall fail and frighten the man away. Is that correct?"

"Yes." She nodded.

"Well, it sounds good to me, Mrs. Vogel. Hey, Black!"

"Sure," replied the ex-Baron, without pausing to work it out on paper.

"So it comes to a simple little sum. How much?"

"Two hundred thousand marks, monsieur!" she said, quietly.

The lids of the two old wolves flickered.

"Cold cash?" enquired Fortworth, a little hoarsely.

"In cold cash, yes."

"Now?"

She shook her head.

"Not now. That would be too ingenuous, would it not? But when Wesel has handed his formula to 'the man from Krupp's' to-night the money will be paid. You will be there. The money will be given to you. Two hundred thousand marks for leaving Mr. Wesel alone just for one afternoon. That is not so bad!"

"You swear to that?" asked Mr. Bunn.

"I swear it."

"Well, I suppose we shall have to take it. But it's cheap at the price. I am a frank man and I say what I think."

"You agree, gentlemen?"

Fortworth nodded and Mr. Bunn answered for them.

"We do."

She rose.

"Thank you. As seven o'clock be at the entrance to the hotel. A grey motor driven by a man with a grey moustache and wearing a green livery, will stop outside at that hour exactly. Enter the motor and you will be brought to the house."

Smiler nodded.

"It's a pleasure to do business with you. We shall come. There will only be just the three of us,—armed, of course," he said, casually, watching her eyes.

"Naturally," she said with perfect tranquility, rose, and, with a smile to each, was gone before either of them could offer to escort her.

They stared at each other.

"We've butted up against a big thing," said Fortworth. Mr. Bunn nodded.

"I'm too husky to speak," he said, "but we certainly look like driving a deep claw into a big hunk of money to-night. I haven't whispered so much or so long for years. My throat's sore with it. Pass the whiskey."

Fortworth helped himself nobly and passed it just as Sing Song showed in Mr. Auguste Wesel...

Mr Wesel was a grater, complete and perfect. Probably there was not a single person on earth upon whose nerves he failed to grate. It was not necessary to know him to experience his unique gift for grating. He could—and very frequently did—grate upon people merely by occupying the same room as they did. In common with most graters he was serenely ignorant that he was universally regarded as anything but what, in a ghastly German accent, he described himself to be, viz., "a man of de vorlt, a schmart business man, and a shport!"

He was what he fondly believed to be an Americanised Prussian. But they would not have admitted it in the United States, nor had the man troubled to take out his naturalization papers. Indeed, he was merely a thoroughly Prussianised Prussian who had acquired a number of mannerisms in America—mannerisms of a kind that real Americans, no doubt, would be only too glad to see taken entirely out of the country. Mr. Wesel, certainly, had taken his share. He was a man of medium-size physique and under-size soul. The sort of man who, sober, is a thing to dodge, and half-sober, a thing to flee from. He was noisy, rather fat, ugly, and his eyes were mean and crafty. Not a nice man.

The partners detested him but they did not adjudge themselves sufficiently wealthy to permit their likes and dislikes to interfere with their business. And then—business, as they conceived it to be, was to make profit from this unpleasant person, pending their departure for England.

He blew in with a greeting that was meant to be breezy, though the insincerity of the breeziness was nerve-rackingly obvious.

"Vhal, you boys, say nhow, vhat's yhour bardig'ler worry, nhow, hey?"

He achieved the amazing feat of making it sound nasal and guttural at the same time. It cannot be printed as he pronounced it.

"I lhige you doo guys same vhay I lhige any Amurrigan cidizen and, zeeheer, nhow, I'm vhor you, un'stane muh?"

Mr. Bunn spoke blandly. It was not a sign that he was pleased and happy when he spoke blandly, for he was not naturally a bland man.

"Thank you, Wesel, old man," he said. "The fact is, we haven't got passports, and, not knowing Germany as well as we ought to—and should like to—we wanted to ask you about it. I suppose we could get them from the Consul here, but if you think it isn't necessary we don't want to bother. What do you advise?"

Mr. Wesel did not pause to reflect. Here was a chance to exhale, so to speak, many cubic feet of "hot air." He was a Prussian and if a Prussian cannot be an official Prussian then he likes above all things to prove that he had great influence with a Prussian official.

"Nhow, sdop right dere, you Black—" he began, and held forth at painful length.

It appeared that he was meeting that night to talk over a "deal" of immense magnitude, a man whose influence in the whole German Empire was colossal. A word to this mighty person from him, Mr. Wesel, would "vix" them "vor vair," so that they need not trouble about passports or anything else. He, Wesel, liked them (patronisingly), and would do a little thing like that for them,—and so forth for a space of many minutes, nasally and gutturally. He had not the least intention of doing anything for them. He expected to be in Berlin on the following day. But he could not resist the opportunity to boast over a bottle of champagne. The partners had no illusions about the man but it was necessary to talk of something, and as Mrs. Vogel had removed the original reason why they had wished to see him, anything would do.

Presently he went away, and the partners rested from him.

"That man may have the secret of a wonderful explosive—but he never invented it. He has as much modern science in his whole carcase as a Navaho," said Fortworth.

"Less, if anything," commented Mr. Bunn, seeking a cigar. "He stole it—Mrs. à la Vogel was right there. Match please!"

Fortworth nodded....

From outside still came that dull, deep sound of marching men, the growling rumble of gun-wheels, and the shoutings of the excited people, triumphant even before War was declared, for they dreamed that the grey-green legions they cheered were invincible.

Precisely at seven o clock, when the German population of the hotel were herding steadfastly toward the dining room, a grey car, driven by a grey-moustached man in green livery pulled up outside.

The indomitable Bunn-Fortworth Combine—who had attended to the matter of dinner an hour earlier—were ready and waiting.

"From Mrs. Vogel?" Fortworth asked the driver.

"Yes sir."

"Good! Get in, Flood!"

They conveyed their cigars and themselves into the luxurious interior of the big limousine and were borne away.

Whither they were being driven appeared to interest them no more than did the unmistakable signs that Germany was on the brink of war which were only too numerous in the streets through which they passed.

They were in a position to know that war was regarded as inevitable, and they had taken such steps as they could to deal with all impending inconveniences. Sing Song, the Chink, driving their own Rolls-Royce, was following the grey car in which they sat, with their luggage on board, and Sweern, their courier, who had achieved the rescue of the car, for the present at any rate, next to Sing Song.

Sing Song's instructions were to wait for them outside whatsoever house they entered. If they had not reappeared within half an hour Sing Song was to reconnoitre, leaving the well-paid (with promises of more) Sweern in charge of the car.

"How much did she say, Fortworth?" said Mr. Bunn, suddenly emerging from a cigarry reverie.

"Two hundred thousand marks!"

"H'm—as near ten thousand pounds as makes no matter. We're letting 'em off very light, Fortworth."

"Don't you get greedy, old man. It's easy money. Try to be satisfied for once. I don't doubt it's a strain, but try to stand it."

"Strain? What d'ye mean—huh! Here we are!"

The car stopped before the entrance to a very large and obviously "Wealthy" house on the outskirts of the town.

Behind them as they got out they saw their own great Rolls-Royce come, whispering, to a standstill. It looked homey to see Sing Song's expressionless face above the wheel.

"Now, my lad, lead on," said Smiler briskly, to the driver of the grey car—"we haven't got any time to waste."

Neither apparently had the people of the house for a minute later they were being introduced by the lady who called herself Mrs. Vogel to the man with whom she worked—"the man from Krupp's" who had come to do business with the blatant Mr. Wesel. His name—for purposes of introduction—was Bohm.

He was the sort of man they had expected to see—extremely German in appearance, tall, military, wire-haired, bien coiffé à la scrubbing brush, a grim mouth and blue eyes about as hard and penetrating as diamond drills.

He was, the partners knew, a Frenchman, but there was nothing French in his appearance or manner. He was the sort of person, Mr. Bunn remarked afterwards, of whom, passing him in the street, one would naturally say, "There goes another three-starred German!"

But he was capable—there was no mistaking that.

"Ah, yes," he said, smoothly, in English. "The two gentleman who are permitting themselves to be bought off—"

Mr. Bunn frowned and interrupted.

"I don't like the way you put it, Mr. Bohm," he said. "What we are doing is selling you the option on Wesel's formula. We may be sharpish business men—but we are not blackmailers. You want to get that right in your mind."

Mr. Bohm smiled—a hard, pinched-off fraction of a smile.

"Why, yes, of course. That is so. We are purchasing the option. You put it with all the skill of an old campaigner—as, of course, one would expect."

Mr. Bunn looked thoughtful and Lord Fortworth looked bleak. They glanced at each other.

"Thank you for the compliment," said Smiler. "It was a bit of a back-hander, wasn't it? I'll have to ask you, Mr. Bohm, to keep your compliments on the chain, if you don't mind. We'll struggle on without them."

"We ain't flappers," chimed in Fortworth. "And the only compliments we care about are the shiny, yellow ones that ring clear on wood!"

The secret agent ran a steely eye over them, reappraising them, and saw that he had under-rated them. He had expected that their nerves would be rather ragged. But they weren't.

"Good!" he said. "Mr. Wesel is in the room adjoining. I will now settle with him, and if you will wait here, I will have the money ready for you very soon-Here are the cigars—" he indicated a table—"and as for wine or coffee, here is the bell."

He bowed briefly and with the pretty "Mrs. Vogel" left the room.

"A hard nut, that," said Mr. Bunn, reaching to the bell. "He misjudged us."

Lord Fortworth was examining the cigars.

"If he mistook us for anything but a pair of nutcrackers, he certainly misjudged us," he replied. "These cigars look good."

"Do they? Well, pass them here, when you've finished with them. What will you have?" said Smiler, hospitably, as a man servant appeared. Then, without waiting for a reply from his partner, he continued to the servant, in a slightly sharper tone, "Never mind, never mind. You may go away, now, my lad. If we want anything later, we'll ring again."

"Very good, sir. Thank you, sir," said the man, deferentially,—his English, too, was admirable—and departed.

"Now, why was that? You made a fool of the man—and a fool of me—and a fool of yourself too!" complained Fortworth.

"Oh, no—listen!" said Smiler, softly. "We can hear what is going on next door—and I've got a kind of idea that Bohm wants us to!"

They listened.

In a moment Mr. Bunn tip-toed over and very silently opened the door, leaving it ajar. As he expected the door facing them was ajar also.

Obviously this was deliberately intended. Silent as two great cats they moved out of their room to the door of that in which Mr. Wesel was interviewing the gentleman whom he fondly believed was "from Krupp's." Indeed, as he did not know that his correspondence, for days past, had been most skilfully "tampered with," so he had no reason to suspect that far from being an emissary from the great murder-emporium at Essen, Mr. Bohm was probably the best secret agent in Europe—and worked, body and soul, for France.

But for a moment the partners might have saved themselves the trouble of moving. For Wesel, who, from the inflection of his voice, appeared to be explaining something, was explaining exclusively in German.

The partners could not have understood less of what he was explaining if he had lowed or whistled or bugled it. Menu French was the only foreign language they really understood.

"What's he saying, Fortworth?" whispered Smiler.

"You can search me, Flood! It sounds as though he has just swallowed an emetic. How do I know what he's saying?"

"Pardon, gentlemen!" came a smooth whisper behind them. They turned agilely. The manservant was at their elbows.

"He says that he will accept two hundred thousand marks for his formula—and a royalty per kilogram upon its manufacture!" explained the man.

Then they heard Bohm speak in a sharp, arrogant voice.

"Herr Bohm asks where he got the formula... yes...." came the low rapid whisper, again. "He answers that he invented it.... Herr Bohm calls him 'liar'... yes... He charges him with having murdered Professor Gale in New York.... broken a sealed bottle of gas that was poisonous to breathe, in the laboratory while the Professor had set aside his glass safety mask... yes... and stole the formula of the explosive.... on the day it was perfected... yes."

There was a sudden silence. It was rather weird, waiting for the keen whisper of the translator. Then Wesel muttered.

"He denies it... he says what does it matter if the explosive is good and Germany gets the benefit at so small a price.... Now Herr Bohm presses him close for the truth.... he admits there was an 'accident' of that kind... and that he seized the opportunity to serve Germany... yes.... He continues to repeat himself...."

The nasal whine of the murderer suddenly stopped on a note of relief—silenced by the harsh, curt voice of the secret agent.

"Herr Bohm says that he will buy the formula for Krupp's... yes.... He says they have tested the explosive, and it is good. He has invited Wesel to count the money..."

They heard Wesel laugh and say something in a low, obsequious voice.

"He says that he can trust Herr Bohm.... Ah!" The whisper grew tense as Bohm's subordinate leaned, crouching, nearer the door.

"Now Herr Bohm asks him if anyone else knows the formula.... He answers 'no.'"

They heard a chair slide softly over a carpet—as though one of the men inside the room had risen.

The translator was trembling with excitement.

"Herr Bohm asks if he knows the secret of making the explosive, now that he has parted with the written formula... yes..."

The listeners heard Wesel reply, laughing raucously, with some of the old raw boastfulness back in his voice.

"He answers that he is a smart business man—and that he knows the formula by heart.... he learned it in case he lost the papers."

The man looked round suddenly at Messrs. Bunn and Fortworth. They were startled for a moment at the marble rigidity of his face, the wild, flaring light in his eyes.

"He thinks that his smartness will earn him a compliment from Herr Bohm"... hissed the man... "but... it has earned him only his death!"

A low whistle came from the room, followed instantly by a light padding thud, and, immediately after, Wesel squealed low—like a startled rabbit.

The man who had translated to the partners darted into the room—Smiler Bunn and Fortworth on his heels.

They saw the man called Bohm with his arms round Wesel—but Wesel lay limp and loose, slipping down, sliding slowly to the floor.

Wesel was dead.

It had been as swift as thought—there was no weapon in view. Bohm must have killed the man literally with his hands, by some such secret and fatal trick, as is said to be known to only a few Japanese wrestlers.

Mrs. Vogel was standing against a desk which was heaped with bank notes and gold, staring with cold, bright merciless eyes at the limp body of Wesel.

"Il est mort?" said the manservant in a whisper.

Bohm nodded.

"Yes. Proceed—as arranged."

Another man—also dressed as a house servant—stole in, and between them the two carried the body out—swiftly, noiselessly, efficiently. Mrs. Vogel followed them.

It seemed to Mr. Bunn that he was witnessing a perfectly rehearsed and acted play. But it was not that. What he saw was a part of the grim, silent machine that is a Nation's Secret Service at work under War conditions—capable, ruthless, terrible.

It startled them—for they had not yet quite realized the sheer horror and terror of War. They could not realize, immediately, that, in its due proportion, the death of this one man was a little thing.

They had not liked Wesel—they had detested him, indeed—but they could not get over the shock of the thing instantly. Two minutes before, Wesel had been alive—laughing. Now he was dead and was already being—disposed of.

"My God! I'm not squeamish, but at the same time—" began Smiler, but the man called Bohm held up his hand.

"Listen," he said, low and incisive. "I have no time for explanation. Realize that there are already a million Germans streaming into Belgium to kill all who stand in their path. I lolled Wesel. I care nothing for that—nothing!" He snapped his thumb and finger contemptuously. "Remember also that he murdered that American scientist, who invented the explosive. That is why I wanted you Englishmen to overhear the conversation. But I killed him because he knew the secret of the explosive. How many French—Russian—English—lives have I saved by winning that secret exclusively for the nations that soon will be allied against Germany? I remind you of this because you are—squeamish. That is all. It is finished."

He pointed to the pile of money on the table.

"There is your money, gentlemen! It is two hundred thousand marks precisely!"

The partners looked at each other—understood each other.

"I must remind you that I am working against time at many grave tasks. Please take your money quickly and go!" said the secret agent, impatiently.

Mr. Bunn shook his head. His face was hard as iron.

"We like money as well as the next man," he said, slowly, leisurely. "But, Mr. Bohm, there is something about that money that makes it no good to us. Understand me, now. We don't pretend to criticise you or the way you do your duty. Perhaps we're a bit old-fashioned—or, perhaps, Dr aren't strung up to the War standard yet—I don't know which. We don't know whether that's French money, English money, or Russian money. But whatever the nationality of it is, it don't belong to us. Keep it—put it back where it came from—for if what you say, and act up to, is right, it looks to me as though every sovereign of it will help to beat back these German man-eaters somewhere or other. And good luck go with it—hey, Fortworth?"

"Sure!" said the saturnine Fortworth.

Bohm looked surprised.

"You won't take it?" he said.

"Not this time, we think!".

"A bargain is a bargain. It's yours, gentlemen!"

"Well," replied Smiler. "Return it to your Government as a war subscription from us."

Bohm nodded.

"So be it. It is for you to say. And now, gentlemen—I must proceed with my work. You are for the frontier?"

"We are. Have you any advice to spare?" asked Smiler.

"Travel your fastest for Holland. Adieu!"

"Good-bye!"

And so, leaving the gold gleaming where it lay, under the electric light, the Bunn-Fortworth Combine went out to their waiting car.

"You two!" snapped Smiler. Sing Song and Sweern the courier, leaned towards him.

"Let the next stop be Holland—or as near that as you can make it. Got that?"

"Yes, mastel."

"Slip into it, then."

The door shut with a click and the big car slid forward into the night.

For a time there was silence in the lavishly upholstered interior. Then Mr. Bunn roused himself from reflection.

"It was a lot of money, that, Squire," he said, wistfully.

"It was," grunted Fortworth. "No use to me, though."

"Nor me, worse luck.... Hard case, that chap Bohm," said Smiler. "He looked as though he thought there might be trouble ahead for us. Wonder if there is?"

But Mr. Bunn was not to wonder long. For they were travelling towards it at the rate of about thirty-five miles an hour—rather more than that, if anything.

THE events of the next twenty-four hours convinced them that they were not in the least likely to get out of Germany across Belgium and into Holland as quickly or easily as they imagined. Evidently the telegram to the infantry officer in the hotel was one of the last telegrams of the kind sent out.

Germany had begun mobilising long before. So that the partners found most of the roads choked with troops and supply columns, and, their claim to be American citizens not being substantiated by passports, the danger of having their car requisitioned and finding themselves imprisoned compelled them to effect their retreat as much as possible by side roads, lanes, forest paths, and, on more than one occasion, across country. They made slow work of it, therefore—slow and by no means sure.

Sweern, their guide, proved himself a past-master of the art of dodging trouble—but he was doing it very slowly.

In conditions such as these, and to which may be added the severe avoidance of towns, hotels and all places at which passing troops are apt to halt, it is not wholly amazing that the question of victualling the quartette speedily became not so much a question as a conundrum—and one extremely difficult of solution—a fact brought poignantly home to Mr. Bunn as, some three mornings after leaving Homburg, he carefully put his head through a hole in the side of the cowshed in which he and his companions had passed the night, and stared anxiously about him.

It was not yet dawn and the world was whitish-grey with that quickly dissolving morning mist which often precedes a hot day.

For the space of a long minute Mr. Bunn's head remained still, his eyes glaring intently through the mist. Then, suddenly, his big face brightened and he gave a low laugh.

"Here he comes, Fortworth! He's a good lad, is Carlo," said Smiler, cheerily, withdrew his head, and a moment later came out through the ramshackle door, followed immediately by Fortworth.

"The thing is—has he got anything to eat," said Fortworth in a rather sullen voice.

"Well, he's been away long enough to steal a four course meal," began Mr Bunn, rather less confidently, peering through the mists at a figure which was approaching silently.

Of the two watchers it was Mr Bunn who possessed the keener eyes, and, suddenly, he gave an exclamation that seemed to contain an equal admixture of horror, despair and disgust.

"Why—why, the blackguard is carting back a snake, Fortworth!" said Mr. Bunn, turning pale. "A snake or an eel! Both the same, as far as I'm concerned. Snake for breakfast—gr-rr!" He shuddered till his teeth rattled.

"You're seeing things," snarled Fortworth, anxiously, himself touched on his tenderest spot. "The man's no fool. Besides, there ain't any snakes that size in Germany or Holland or Bulgaria or wherever we've landed ourselves. Sweern's too smart to insult hungry men with snake. You're losing your nerve, Flood!"

But, in spite of the somewhat rickety confidence he managed to instil into his voice, he seemed more than a little nervous himself. Mr. Bunn ignored him.

"What the three-stars is that dead thing you've got there, Sweern?" asked Smiler of the approaching figure.

"Ah, gentlemen—a great piece of good luck. For twenty marks only—look there!" answered the guide, and flourished about a yard of black, snaky-looking stuff at them.

"What is it, Carlo?" demanded Smiler.

"Blutwurst—yes, gentlemen. Good blood sausage—nearly fresh! Ha-ha!"

Evidently Mr. Sweern was extremely pleased with himself.

"Blood sausage!" gasped Mr. Bunn. "What's it made of?"

"Made of, sir? But of blood, certainly."

"Blood!"

"But of course, sir. It is good delicacy—it is made of hog's blood and excellent rich pieces of fat to it and few other things put in perhaps and seasonings, also!"

"Good God!" groaned Mr. Bunn, not with the least intention of profanity, but because he felt so tragic. The two partners, who were epicures, not to say gourmets, stared at the sausage with a sort of terror in their eyes.

"What do they use it for, Sweern?" asked Fortworth, with bitter sarcasm.

Sweern looked bewildered. He waved the sausage in the air. There were two feet of it at least.

"But it is all right, gentlemen, yes, certainly," he said. "There is some nutriment and a flavour also very delicate. You will appreciate this sausage so much."

His face cleared as he thought of something.

"Ah, you think it is wet blood in this sausage, gentlemen, is it not? Oh, no—it is nice and dried—congeal, I think you call that word—and quite prepared to be eaten now. It is ready at once—quite ready! All Germans appreciate this kind of a sausage to their dinners."

"That," said Mr. Bunn, heavily, "has completely put the lid on it! You mean well, Carlo, but what you haven't got into your head is that an English—or American, perhaps I ought to say—an Anglo-American stomach is a higher class proposition than a mere German stomach—if stomach it can be called—which it can't. No doubt most of the grey green toughs we've seen marching to the frontier would leap at that ungodly man-killing sausage (so-called) like hungry tigers—but, speaking for myself, Sweern, I ain't educated up to it, yet, and I hope I never shall be. I don't want to hurt your feelings, Carlo, old man, for I know you've done your best, but, as far as I'm concerned, go right ahead on the sausage. Go on! Start in, Squire—eat as much as you want of it. I hope you enjoy it. Only don't thrust it on us. We're hungry, true—but we ain't ravenous yet. Save about eighteen inches for Sing Song, though. That's just the kind of tit-bit that would appeal to him. He's Chinese and a delicacy that would give an English fox-hound paralysis of the diaphragm will make a Chink clap his hands with joy. So don't mind us—we'll just sit down and have a cigar and admire you two eating your breakfasts."

And, so saying, Mr. Bunn turned away, more in hysteria than in anger, and took out his cigar case—an example that was followed by ex-Lord Fortworth...

Clearly, if Sing Song, who, like Sweern, had left the camp in the cowshed before dawn, on a foraging expedition, failed to achieve any capture more attractive than Blutwurst, the unfortunate Messrs. Bunn and Fortworth were face to face with the unprecedented calamity of going without breakfast completely and entirely.

This was an event so unexpected that they felt a little dazed, as, sitting against the wall of the cow-shed, they smoked their cigars and, with slightly inflamed eyes, watched Mr. Sweern enthusiastically devour a generous share of the blood-curdling delicacy he had brought back so triumphantly.

"He eats it cold!" said Smiler, faintly, to Lord Fortworth.

"Yes—the man would eat anything," grunted Fortworth. "Anything—hot or cold!"

Then their faces brightened as Sing Song came gliding noiselessly round the cowshed, carrying a bundle, and smiling a smile of bland content.

The partners were on their feet in an instant.

"Well done, my lad!" gasped Mr. Bunn. "What have you got? Open it, Sing Song!"

The smiling Chink spread open the bundle.

It contained a cut ham, eggs, a cold fowl, two bottles of Rhine wine, a large chunk of butter, and a selection of cakes.

"No fish?" said Smiler, with a falling inflection.

Sing Song casually produced from his clothes a bottle of Bismarck herring.

"Well, I suppose that's the next best thing to fish," said Fortworth.

"Sing Song, you wolf, where did you steal this collection? Never mind—never mind now. There's no time for talk. You're a good lad—a very good lad. I shall see if we can't raise your salary when we get back to England. Meantime, start a fire, my lad, start a fire and hurry up with a ham omelette—a good one, now—one of your very best, my son. We're feeling a little, run down—"

Here Mr. Bunn abruptly discontinued his day dreams, as something fresh appeared on the scene—something made in Germany it looked and sounded like.

It splashed and spluttered guttural and excited German sounds all over the place, rolling its eyes, and waving its arms.

It was a man, of fat though hard-working appearance. Some kind of farmer or tiller of the soil. It pointed furiously at the collection of breakfast materials which Sing Song had gathered together, and proceeded to give what seemed to be a lecture upon ham, Bismarck herring and so forth.

Only Sweern understood him—and Sweern allowed him to splutter himself breathless before speaking. "He says these things have been stolen from his farmhouse—his wife saw a Japanese man creeping away with them. She was too late to catch him," explained Sweern presently to his employers. "He says also this shed for cows belongs to him and he wishes explanation from us for making use of it as sleeping apartment. He says he will make extremely serious matter of this. He hates the English and all Japanese thieves he says."

"Tell him, in whatever language he can understand, if any, that we're Americans—and that Sing Song is a Chinese Chink and a poor heathen that doesn't understand. Ask him how much he wants for the food?" said Smiler, impatiently.

Sweern made the necessary noises at the person. But he was not to be conciliated. He was a sullen-looking, shallow-browed lout, and appeared to have plenty of hate left over for Americans and Chinese also. He had been insulted, he said. They had interfered with his meals department and, as all the world knows, a person has only to interfere with any German's meals department to turn him into a howling maniac for the remainder of the month.

"He says it is no good—he is not shop-keeper—he will not be satisfied—" began Sweern, anxiously.

"Oh, all right. Break his jaw, Sing Song," snarled Fortworth, savage with hunger.

Sing Song was up like a cat. The order harmonised much too sweetly with his own inclinations to be dallied with.

"No, no—please wait—" began Sweern, anxiously. "This is a serious matter—"

He stopped, listening.

But what Sweern heard the agricultural oaf heard also, and apparently appreciated, for he began to shout at the top of his naturally noisy and unpleasant voice.

There was a thudding of horses' hoofs, a jingle of accoutrements, and a half-dozen lancers—Uhlans—cantered up.

They reined in and one of them—a non-commissioned officer—grunted at the party. The farmer lumbered up to his stirrup and, raising his voice, practically drowned the gruntings of the sergeant, with his frantic demands for revenge.

Now, it is not well to over-grunt a sergeant of Uhlans unless one is his superior officer. Certainly it is not wise to do so in war-time if one is merely an agriculturist in a smallish way. The partners saw that, when, annoyed at the bawling of the farmer, the sergeant looked down and viewed the wide-open mouth at his knee. He uttered an oath, and, it seemed, endeavoured to plug the mouth with a fist the size of a football. It was as though he wanted to drive it completely down the throat of the farmer. He would have succeeded, too, had not a number of teeth got in the way. As it was the man was knocked down, and did not arise. He stayed where he was put, howling dismally and spitting out teeth.

The sergeant turned to Sweern.

"Japanese and English, eh! You are arrested!" he said, as offensively as he could. "Come on—quick—line up!"

Precisely what would have happened is difficult to guess. None of the Bunn trio were at all in the mood for "lining up." They were much more in the mood to commit suicide by "starting something" with the weapons they were already feeling for. But, fortunately, another two persons appeared on the scene, one of them an officer of Uhlans, the other a yellowish-complexioned, Kaiser-moustached person in civilian dress.

"What is this?" asked the officer, curtly. The Uhlans saluted like one man, and the sergeant grunted briefly but enthusiastically:

"One Japanese and two English spies, sir! Also a Dutchman!" said the sergeant (they learned afterwards from Sweern), very much as though he were saying, "One toad and two cobra di capellos! Also a rat!"

The officer nodded, but before he could speak Sweern got into action.

"No, High Sir," he said. "These are two American gentlemen highly placed, of New York, and this is their valet, a Chinaman. That is quite true, Loftily-Placed and Well-Born Member of the Prussian Nobility" (or servilities to that effect). "As for me, I am their courier."

The officer, evidently satisfied that Sweern at least knew how to behave himself in the presence of a superior, looked at the partners, and bowed stiffly.

"Gentlemen, I must ask you to show me your papers," he said politely in quite good English.

Mr. Bunn decided, without difficulty, upon a lie.

"I am sorry, General," he said. "But the fact is, we gave them up yesterday, passports and everything, to an officer. He was not of such high rank as yourself, I should say, and—to put it bluntly—he never returned them!"

That was the explanation, carefully pre-arranged with Sweern, which they had decided upon. But none of them, not even the intelligent Sweern, had quite anticipated the kind of reception it would receive.

The Colonel—not "General," as Mr. Bunn had tactfully put it—actually appeared to believe it.

He hesitated.

Then the sallow person with the humorous moustache, who had been scrutinising the partners and Sing Song, spoke quietly to the Colonel, who listened, pondered, and finally nodded. Sallow-Face turned to the partners.

"Well, gentlemen, Colonel von Blichter very kindly agrees that I should offer you my hospitality—until enquiries have been made." He ran a quick eye over the food that was the root of all the evil, and smiled.

"I hope that you will breakfast with me. I should be charmed if you will do so. We may be able to arrange the matter of fresh passports, and it will be interesting to discuss—many things. My name is von Helling—and my house is close at hand. What do you say, gentlemen?"

They accepted—it was the only safe thing to do.

Then Colonel von Blichter hooted curtly at the Sergeant of the Uhlans, who saluted like a Jack-in-the box, and the sergeant grunted at the men, and the men promptly rode away followed by the sergeant.' Their exit was unostentatiously emulated by the farmer, who appeared to fear the Colonel as though he were the cholera.

Then the partners with their newly-found "friends" started for von Helling's hospitable roof.

Sing Song and Sweern were abruptly bidden to follow with the car.

So far so good—"too good to be true," as Mr. Bunn presently found an opportunity of muttering to Fortworth.

As they cleared the coppice, under the side of which the cow-shed was built, they came upon a dismounted Uhlan holding two horses. Evidently he was waiting for the Colonel, for, after a muttered colloquy with von Helling, and a nod to the "Americans," von Blichter mounted one of the horses and went his way. The partners were not sorry to see him go. He had been civil enough to them,—they did not know yet that it was the so-called "All-Highest's" Imperial command that Americans were to be treated with all consideration—and certainly he had arrived at a most appropriate moment, but, on the whole, they found him wearing, very wearing.

And long before Messrs. Bunn and Fortworth had finished breakfast with von Helling they had made the discovery that the Colonel was not the only thing in Germany that set their nerves on edge. The Colonel (and the Uhlans) had merely left their nerves bare and raw, von Helling applied salt to them.

It was a large and comfortable country house to which he took them, and it was a really fine Anglo-American breakfast which he shared with them, but, in spite of these things, the man gave them the "willies "—to quote Fortworth subsequently.

Nevertheless, they did not under-rate him. He had not asked a dozen questions or made a dozen remarks before they realised that, whatever else he was, he was distinctly no fool.

Presently, towards the close of the meal, Mr. Bunn, selecting a cigar, came to the point around which he had hovered for the past hour.

"Say, Mr. von Helling, if you hadn't told me you were a German, I should have put you down as an American with a German moustache," he said, bluffly.

For a long moment von Helling said nothing. He looked at them with a calculating, appraising stare as though weighing them up in his mind.

Then he smiled a thin, rather furtive smile.

"Yes?" he said. "And if I were indeed an American, what would be your opinion of me?"

He seemed rather to hang upon their reply.

But he had to do a pair as skilful as himself, a pair whose mode of dealing with competent people was to take all and give nothing—least of all to give themselves away.

"What would you say?" he repeated softly.

Mr. Bunn looked across at Fortworth and Fortworth looked across at Mr. Bunn. They understood each other, without words.

"Say?" said Smiler, thoughtfully. "Say?" He leisurely lit his cigar. "Why, I don't know. I suppose, things being as they are, I should say that, for an American, you seem to have a surprising pull with these Germans."

"Perhaps I have," replied von Helling, softly. He continued:

"Suppose an American said to you that he has lived so long in Germany as to become accustomed to the German people, an admirer of their ways and a firm believer in their ultimate destiny. That he had become a naturalized German, and had won to a position of such importance that he had access to knowledge which definitely convinced him—as a man of wide experience and knowledge—that nothing could prevent the German Empire from becoming the dominating Power of the world?"

His voice unconsciously rose a little, and his keen eyes were glowing—a change that Messrs. Bunn and Fortworth duly noted and mentally filed for reference. Already they had a faint, far-off premonition that this man needed them—wanted to use them.

It was, Mr. Bunn decided, not a moment for blatant, noisy, unthinking patriotism. He wanted to find out to what von Helling was working his serpentine way.

He pondered.

"Well, I suppose every man is entitled to his opinions, isn't he? If he honestly believes the German, or, for that matter, the Red Indian or Fiji or Eskimo, nation to be on the right track, I've never heard of any law, moral or otherwise, against his taking out his naturalisation papers," said Smiler, slowly. "I've never thought about it. Have you, Black?"

Mr. Black had not thought about it, either, it appeared.

"Mind you," continued Mr. Bunn, "I hold to one thing, first and last. A man, any man, whatever his nationality, is entitled to a living—and as good a living as he can get. If he's an American, and can't get a living in America, but can in Germany, then I won't go so far as to say he isn't entitled to become a naturalised German. That's how it goes!" He was watching von Helling narrowly—and he knew that he was handling the man rightly.

"Yes, that's how it goes—to my mind," he said. "A man has a right to live, first—and, secondly, he has a right to live the way he wants to, provided he keeps within the law. They're facts—you can't dodge them."

"But—how about patriotism—the flag!" said von Helling eagerly.

"Patriotism? Flag?" echoed Smiler. "Well, he owes his duty to the country he's a naturalised member of, and the flag he travels under, I take it."

And he knew as he spoke that he had von Helling hooked.

"Well, it is pleasant to meet an Englishman—I know, of course, that you, Mr. Flood, are an Englishman, though your friend is American—so open-minded and fair as you appear to be," he said. "You see, it makes it easier for me to tell you that I am exactly such an American as we have been discussing!"

He paused, evidently expecting them to be surprised.

But they did not appear to be.

"Oh!" said Smiler, casually. "Well, every one to his own taste."

"Sure!" said Fortworth. Von Helling nodded, smiling.

"Now, gentlemen, what about you? Are you trying to get back to England? You are anxious about your estates—businesses,—perhaps?"

He was asking them who and what they were.

It was Smiler Bunn, seized with an inspiration, answered.

"Estates? Businesses?" he echoed, and laughed. "D'ye hear that, Black? Why, my dear sir, we were practically broke before war was declared—now, except for an odd hundred or two, the furniture of our place in London, and the car, we are right up against it! Estates and businesses! Do we look like men with estates?"

A bitter joy flashed into the eyes of von Helling.

"Why, you looked—you have the manner of prosperous men," he said. "The war has ruined you? You were perhaps stockbrokers—speculators—racing men—something of that kind, perhaps." He watched them closely.

"Even, perhaps, adventurers? Professional gamblers?" he asked, smiling. "Oh, don't be annoyed—I am very much a man of the world."

Mr. Bunn leaned forward.

"Well, you can put us down as adventurers," he said, slowly. "What of it? Europe is stiff with them."

Von Helling spoke most earnestly.

"And not too—shall I say—scrupulous!"

"Men in our position can't afford to be scrupulous!" said Smiler. Von Helling rose.

"Ah, no, indeed! Gentlemen, I am delighted to have met you. You are men after my own heart."

They swallowed the insult, without present comment.

His eyes glittered, with a sort of triumph.

"We can be of service to each other," he said. "Of immense service. Let us be frank! You need money—and you are not in the least particular as to how you earn it—and you are not roped to the wheels of the British Juggernaut"—he poured himself a cognac with a hand that shook and thrust the decanter down the table towards them.

"Gentlemen, you have come to the right man!" he said, on a note of hoarse savagery.

The partners showed no enthusiasm. They had landed their fish, they knew that. He had made the sort of mistake that sooner or later every scoundrel makes—he had assumed that another man, two men, indeed, were the same kind of reptile as he was himself.

Adventurers—chevaliers d'industrie—men who lived on their wits, they were—but, nevertheless, England meant more to them than even they guessed. Von Helling had yet to learn that.

"I shall have a proposal to make to you a little later," said the man. "A proposal that will be worth thousands of pounds to you—yes, thousands—just because you don't happen to be pig-headed patriots."

"What do you think of that, Black?" said Mr. Bunn, with a sort of hard gaiety, which, to one who knew him, was a clear danger signal. "Mr. Von Helling's going to steer thousands our way."

"Yes,—so I heard, Flood," said Fortworth. "So I heard! Perhaps Mr. von Helling will state his proposal—and his price."

Of the two, Fortworth was ever the worst-tempered. There was a low and sullen note in his voice that would have warned anyone not a stranger to him to go cautiously.

A clock chimed ten and von Helling started.

"I must go now. It is an urgent military matter—unavoidable. I shall see you to-night at dinner. Meantime, regard this house as at your disposal—though it would be wiser not to leave the grounds. There are troops in the neighbourhood—and they are sometimes over-zealous. Don't misunderstand me. I merely advise it as a matter of commonsense—not, of course, as a threat. There are two other guests—one a Colonial, a South African, named Carey, a pleasant fellow—the other an Indian gentleman, secretary to the Rajah of Jolapore. He was on the way to Baden to arrange for the arrival of the Rajah on a visit, when the war broke out. You have no colour prejudices, I hope? His name is Mirza Khan—you will find him a quiet, scholarly kind of man, but very broad-minded. And now I must hurry away. To-night we will go into the matters at which I have hinted!"

And, so saying, von Helling left them.

They grinned a rather tight-lipped grin at each other.

"Better say nothing much in the house, old man," said Smiler, very softly. "Remember Mrs. Vogel's tip that German walls have eyes and ears in war time. We'll talk it all over in the garden. Queer, this blackguard should have got old Mirza Khan as well, though! Funny, too—in a way!" Mr. Bunn laughed abruptly. "What did he call him, Black? Quiet, scholarly man, but very broad-minded. Well, he's right about the broad-mindedness. Mirza's as broad-minded a crook as I ever met! Let's get into the garden."

The two partners strolled out on to a lawn, heading for a seat under a lonely tree near the middle, well out of earshot of any possible eavesdroppers...

They were pleased rather than surprised to learn that their very old friend Mirza Khan was in the hands of von Helling also. They had known, before going to Germany, that the Rajah of Jolapore, an old "patron" of Mr. Bunn's, and one from whom the partners had drawn much gold for services rendered at various times, was planning a visit to Baden, and it had been part of their programme to meet him by "accident" there.

The outbreak of war, obviously, had stopped the Rajah in time though not his vanguard, consisting of Mirza Khan, who was not his secretary as von Helling fondly dreamed, but his extremely confidential body-servant. Broadly speaking, what Sing Song the Chink was to Smiler Bunn, so Mirza Khan, in his more exalted style, was to the Rajah...

"Well, Flood, what sort of a proposal is this dog, von Helling, going to dope out to-night?" said Fortworth, sourly.

Mr. Bunn looked his partner steadily in his congested eyes.

"Oh, something pretty treacherous, old man. We shall see when the time comes. You want to keep your temper when he gives himself away, understand. Forget it till then—and here's Mirza!"

A black and glossy gentleman had come out of the house, and was strolling towards them. He wore—as though he were still in London—a silk hat and frock-coat. It was evident that he recognised them, for they could see his shining, toothful smile from where they sat. He came up with outstretched hand.

"Oah, thiss iss delightful and unexpected pleasure, sars—yess, indeed. It iss remarkable coincidence. How are you, sars—how do you do yourselves!" In his excitement his grammar was a little shaky, but they thought none the less of him for that.

"Why, Mirza, old man, it looks homely to see that smile of yours again. We expected to run into you at Baden, but I suppose the Rajah just missed it, hey?"

"Oah, yess, he escaped it by skin off hiss teeth. He wass following me in three days. Pretty close shave, thatt, my dear sars!"

"Sure!" said Fortworth. "How's His Highness?"