RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

EARLY in 1897 the ecclesiastical authorities of Amalfi removed the painted stucco wherewith the eighteenth-century baroque taste had covered some fine columns in their Cathedral nave. Those columns were part of the debris of ancient Paestum transported there in the eleventh century by Robert Guiscard, and with them was brought much building material—cornices, lintels, pediments, and tombstones to be used in the decoration of the new city. A general removal of stucco bared several such fragments in the Cathedral walls, and in the hope of finding something noteworthy among these uncovered stones, I went to Amalfi at the beginning of October. Nothing rewarded my search beyond a few half-legible words, until the sacristan brought me a marble tablet that had fallen from a pilaster. It was the front of a cinerary box, an inch thick and a foot square. In its angles I observed the emblem of sun or fire worship. It bore a mutilated inscription, of which I took a rubbing; and after an hour's study, made the following translation of its fifth-century Latin:

Aristodicides of Syracuse (the son of) Mele(ager) Beloved of the Ilian Ath(ena) Who in the (year of the) desolation of Gen(seric) Removed the sacred flame of Poseidon (to the) Crypt called the thinking (place of) Po(seidon).

The year of the "desolation of Genseric" was A.D. 455. What the sacred flame had been, or whether the crypt to which it had been removed still existed, aroused my deepest interest.

I at once resolved to pass a few days at Paestum, with whose temples I was familiar, and where in recent years I had twice spent a night at the Villa Salati with Danilo Macagni, their official custodian. The thought grew strong that Aristodicides had been an inhabitant of Paestum, and that when Pagan Rome crumbled, he had withdrawn a votive lamp from the shrine of Poseidon to some hiding-place of safety. Such votive flames were frequent in ancient Greece and Rome, the fire kept alight by Vestal Virgins being an example. Such a flame could not well have been carried very far, and would probably be hidden in some adjacent sanctuary unknown to early Christians. Might not this thinking-place have been a subterranean cell connected with the Temple—perhaps to this day as perfect as the chambers discovered in the Pyramids?

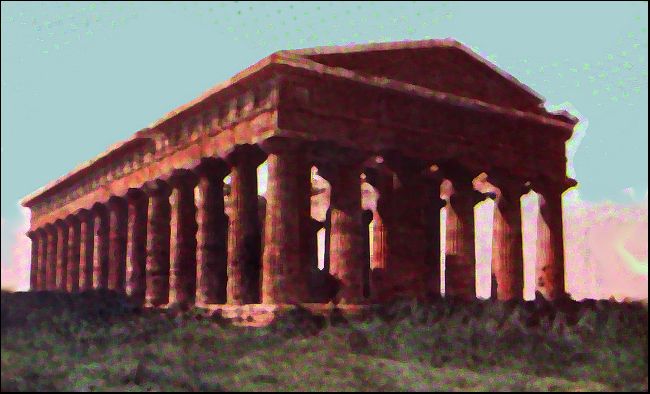

The Temple of Poseidon

In the eleventh century the demolition was so thorough that ancient Paestum passed piecemeal by sea to Amalfi, only the blocks whereof the temples are built being too heavy to move. It was thus the mortuary tablet of Aristodicides found its way to the sunny town of Cathedral steps. Where once were streets and walls is now waste land, and the House of Poseidon stands in a plain of spectral silence. Behind it rise lean rock-shadowed hills, and westward the sea is a-glitter—the same sea that chafed and surged and babbled on these rocks of old The twice-blooming roses of Paestum mentioned by Ovid and Virgil survive, still breathing the perfume wherewith Poseidon blessed them. This temple is the finest surviving specimen of classic architecture, and is born from the immortal heart of Greece. An instinct of artistic creation animates its colonnades, wherein we read the thought of men who achieved their ideal. To-day the lizard glides furtively across its pavement in the noonday's glamour. Amid this sun-browned calm the voice of soft-spoken Italy bids us take note how beautifully the gods set the stage for the mortals they loved; and a shaggy mongrel—a democratic mix of dog dregs limps by—baring his yellow fangs, and recalling to-day.

At the centre of Paestum's ruined walls stands a large farmhouse—a house of "many mansions," to quote St. John—that with its score of rooms might lodge a dozen. It shelters occasional visitors who linger more than a day, and artists. Against its ancient stucco and wine-coloured timbers, the tamarisks lift their riotous bloom. On that day the dim poetry of autumnal pathos touched its garden with mauve and green and amber tints. At the door hung a grey parrot addicted to conversation. Above a dilapidated pergola, the sunlight, striking through reddening vines, transformed their leaves to a supernatural brilliance—as though some curious whims of fancy had been made real and sky-swung in opalescent light.

Danilo Macagni, curator of the ruins, with whom I had often spoken during previous visits, received me with that charming courtesy for which only Italians have leisure.

"Come with me upstairs, Signore... guest of my house, you shall have the best room.... It is not much: cosa vuole, what would you more than our best? Dinner will be ready at once... subito, subito!" he added, his white teeth gleaming. "You are always punctual, and that is right... we should eat when the farina is ready... the thread at the needle's eye. You like our spaghetti? You are a man of taste—it is best as Diana orders it, unspoiled by sauce."

"Parlate d'oro!" screamed the parrot as its master shuffled away.

I had seen Diana Macagni twice when I had supped and spent the night under her father's roof. But the important purpose which took me to the Villa Salati in 1897, and the tragic circumstances which resulted, have identified my remembrance of her with that October meeting. On the first occasion I had spoken to her only in the garden, once finding her busy with pruning-knife, lifting the bared arms of Helen to an espaliered vine, and again in the arbour, when pouring for me a draught of Falerno, I said, half jesting, "I tremble, Signorina, lest you lead me across the Bridge of Sighs."

Now I found her in the upper hall, near a wide fireless chimney, seated upon a tabouret before an embroidery frame, across which her fingers were weaving some web remote as fairyland. I wondered whether in these graceless days we shall ever again know the charm of hand-made things. And when she turned and bade me a smiling good-day, I thought of her namesake—that white-bosomed Diana whom the Ephesians loved.

My frugal dinner ended, I went to the Temple of Poseidon, where for the first time I was to dig in Vaini's phantom domain without his guidance. I knew the ruin well, but scanned it now with an interest wholly new. I traversed the central enclosure, examining the fallen fragments and the sides of its parallelogram. For centuries nothing has changed in the aspect of its colonnades, nor have the masters of Italian archaeology found about its site any clue to hidden things. I observed in the fields a black-coated man busy with a surveyor's instrument. In the distance lay the brooding beauty of Italy, and seaward, a veiled metallic shimmer, like the steely blue of a Toledo blade, rested on the water. The eager October wind was strewing the Court of Poseidon with yellowing leaves, and bore a sense of harp-strings faintly smitten before forgotten gods.

I had brought with me an instrument at whose mention the reader will smile, its power being almost unknown. It is before me now—a crystal sphere the size of a tennis-ball, within whose glowing heart I doubted not I should presently evoke, amid faint colour and fretted outline, a semblance of Aristodicides, the beloved of Athena. I raised it in the sunlight—the work of a lifetime in the making—and older perhaps than the ruin wherein I stood. What weird thoughts must have been woven about that small circle... how lurid a semblance of life's chaotic drama have moved within it—signalling, beckoning, and fading away!

Standing that noonday where once had been the Altar, and concentrating my attention upon the crystal, I heard a light footfall, and turning beheld Diana Macagni, alert as her namesake, the huntress of classic days, and like her startled at sight of an intruder. For this modern Diana instantly connected the uplifted crystal with an uncanny purpose, and her grey eyes turned pale yellow with excitement—like brilliant catseyes in the sunshine. The thought flashed upon me that what I was in search of might be no secret to this keen girl who had been so quick to follow and observe. A colour of pink roses fell all about her, and where she moved there trembled a thought of music I looked deep in the grey of her eyes and remembered the silver sea Poseidon loved. The fine white brow under the coiled hair was troubled, and the smile with which she greeted me faded instantly.

"Signorina," I said, "it is fortunate that you have come to direct me, for I am not a little puzzled. I have reason to believe that beneath this ruin is a chamber wherein is hidden a curious vestige of antiquity."

The anemone flush faded, and the girl's lips whitened with anger. "Signore," she replied impetuously, "there are things to be spoken only when one is about to die."

"That will be late for you and not soon enough for me," I answered. "This crystal, which contains the elements of pure intellectual force, may presently reveal more than either of us know. Come, stand beside me—you shall see faces, and this temple as it was, and ancient Posidonia, a fairy city thick-painted with vivid sunshine and deep shade."

The girl listened in tragic silence, then suddenly, to my amusement, exclaimed, "There is but one proper thing for you to do, Signore, and that is to go away."

"You put the truth exquisitely," I assented; "but what if my heart bid me stay?"

"You forestieri," cried Diana, in a torrent of displeasure, "are enough to drive one mad. You patronise us, laugh at us, write stories about us, burrow under our temples, uncover our graves, and strip our country of the things we love. It is true that we are poor—but have we no feelings?"

"Very well said," interposed the grave, quiet voice I knew so well, as into the temple stepped the black-coated man I had noticed surveying, and in whom, at that distance, I had not recognised Professor Vaini.

He was evidently surprised, and not altogether pleased at finding me in possession, and stood glancing alternately at me and at Signorina Macagni. He looked, as ever, a type of the fine-handed artist, deliberate, admitting no failure, self-centred, and masterful as one who has tourneyed with forces we call unknown. "Whilst I am deep in toil," he at length said, eyeing me severely, "living laborious days, I find you, my junior associate, foot-loose as usual, and provoking this young woman to anger."

"This young woman," I answered, "is well able to take care of herself. As to my being here foot-loose, I have come on a quest that perhaps brings you also. For years I have conjectured the presence of some buried mystery, and an instinct, strong as the whisper of scientific intuition, pointed the way. This young lady is present as my assistant, and was about to put me on the line of discovery when you appeared."

"So much the better," exclaimed my former tutor, addressing Diana Macagni with a quizzical smile. "Doubtless, Signorina, you and your father know that a subterranean passage leads from the Villa Salati to a point beneath us. This implement," he added, showing us a small gold blade, "which I call my underground master-key, has revealed its course with precision, and you will now guide me to its entrance. There is no joy, philosophers say, in mere possession, and you are too sensible to oblige me to invoke the authorities. Our purpose is to recover whatever lies buried here and place it beyond peradventure. As you were saying when I arrived, a freak collector—a mercenary dealer—a meddling savant—who can estimate the desecration of these modern days?"

Diana listened aghast before this menace. Yet, glancing at her dauntless face, the odd fancy came to me that beyond Vaini's spoken word some inspiration, unheard by our grosser sense, had reached her, and while filling her soul with a purpose, had laid the finger of silence on her lips.

At this moment a nasal drawl sounded outside the Temple. "That unchewn grass," remarked a man's voice, "is not worth a hundred dollars."

I beheld a middle-aged man and a young woman—evidently tourists from Chicago. "Say, Poppa," asked the girl, "what place did you tell me this is?"

"In I-talian," replied her father, spelling the name from a guide-book, "it's P E S T O.... Look out, Hefty, you've catched your dress."

"Poppa," replied the girl severely, clearing her skirt, "don't say catched—say cort."

"I guess we'll stop here overnight," said her father to Danilo Macagni, who followed. "Our baggage has gone somewhere down the line, and we'll wait till we find it—and I will find it, I bet you a dollar and a quarter. You can fix us up a lunch, just a four-egg omelette—no fresh-water chickens, as we call your frogs.—What did you say is your name—Devil Macaroni?"

"I don't want but a cracker heavily stuccoed with jam," interposed the daughter.

Her father turned to me with a thoughtful smile. "I've written to my friend the Bishop of Naples to come out and work up a gospel point about this country. Naples! It smells like to kill flies. Ruins, beggars, hotel sharks—and, Great day in the morning! no more morals than a backyard cat!"

I HAD seen these people at the hotel at Amalfi and had heard them addressed as Mr. Gallagher and his daughter. The father was a man of distinctively American type, of slender figure, and having a face that bore the stamp of meditative power and the habit of control. His iron-grey hair rose straight from a square forehead, and in moments of abstraction the lines about his mouth seemed to harden to iron. He had begun life as a country lad, had found employment on the nearest railway, and in twenty years had made his way into the phalanx of millionaires. He spoke the Western nasal vernacular, and smiled so sourly at his own jokes, that in mirthful sallies his lips reminded me of a nutcracker.

His daughter was habited in a Parisian silk gown, and wore a little felt wide awake hat perched upon a mass of yellow coils. Her features reflected her father's earnest self-dependence. She had fine teeth, red lips, and a beaming facial irradiation. Her voice was shrill, and she spoke in a leisurely drawl. She possessed a considerable stock of mixed information, inclined to an extreme of nervous restlessness, and adored her native belongings. "There are many cities," she said, "but only one Chicago." She habitually adorned her phrases with the split infinitive, was familiar with chance travelling folk, and shook hands with the hotel head waiter. By way of religion, both father and daughter cherished a sentiment of absolute human equality, and their ardour ran towards such mechanisms as submarines, motors, and pianolas. This physical and mental similarity Miss Gallagher expressed by the Americanism that she "favoured her Poppa."

During that afternoon and on the following morning Vaini laboured fruitlessly to induce Danilo Macagni to permit us to enter the passage we no longer doubted led to the crypt referred to on the fragment I had found. Several times he and I walked together in the fields, away from listeners, considering the possibilities of our situation. I have often recalled Vaini as I beheld him in the calm of those brilliant October days, for he too felt the charm of such hours. He spoke with an insight which illumined the Italian suavity of his phrase, and reflected from within himself those elements which made the antique type.

"More than once," he said, glancing back at the Villa Salati, "I have told you that in this modern Italy there are not wanting a few in every walk of life, often the humblest, who, after all these centuries, still hold the curtains of their past wide open. They boast themselves descended from blood that was patrician when ours...? They study the enchanted fields that we call myths, and Rome for them still wears its crown. As one that wakes to music, they return to Egeria and the Sibylline books. For them, all good things follow where once Diana trod. More than this, they claim a faculty that brings Time back with vividness. Things that with us have faded into remote perspective stand in their foreground. With us history is a makeshift; to these people, several of whom I have known, it is something they remember."

"Is it possible," I interrupted, "that Danilo and his daughter are of that pagan world?"

"It goes without saying," answered the professor, "though how they became possessed of a secret that has descended through perhaps seventy generations is useless to speculate upon. It suffices to know that to these people the thoughts that filled the classic mind are as real as to the orthodox are the pearly gates. Their life is spent in a haunted chamber—a camera infestata, as we say—wherein they move through bygone ages, and meet men and women who like themselves lived ages ago. Our line of action is clear. After luncheon you will oblige me by finding the Signorina whilst I talk with her father. We will propose the same offer to both. If they will allow us to enter the crypt and make half an hour's examination we will leave Paestum, engaging to take with us the two itinerants and their luggage—lost or found."

Lunch, the Italian noonday dinner, was served in the upstairs hall at a long table. Danilo and his daughter did the honours at one end, Mr. and Miss Gallagher being seated at the other, and Vaini and I side by side. It was a repast that could not have pleased the transatlantics, and the lady remarked that she "despised" it. Mr. Gallagher was disposed to conversation, and perforce addressed himself to me, Vaini not understanding English. I listened with amusement, having known many of his type—men whose lives have been spent building a pyramid of dollars, whose minds worked like highspeed machinery, of a generous and insouciant nature, joking with servants, offering cigars to the waiters at his club, addressing bank presidents, barkeepers, and housemaids all by their first name.

To that indescribable broth that goes so well with grated parmiggiano, followed fish from the hill-streams, and slender savoury sausages on a bed of saffron-tinted rizotto. The table was ornamented with wild flowers and with fiaschi of white wine—"the vino d'amore of Petronius," remarked Diana.

"I'm as dry as a mummy," said Mr. Gallagher, with a good-natured laugh: "a horse's neck, with a streak of Blue-grass whisky through it, would be just about the drink for yours truly. Say, Devil Macaroni, can't you get some fatted calf fixed up for to morrow?"

"Poppa," interposed his daughter, with a furtive glance toward Diana, "I just hate that girl. Say, let's put our raincoats and some sandwiches in a gripsack and start for home!"

Her father gave no heed. "We are ourselves descended from a Roman family," he observed; "antic blood is a choice thing, and ours is antic as old Manongahela. Our first ancestor was an elegant gentleman named Caligula—pronounced Gallagher out in the States."

"Professor Vaini," I answered, translating, "is deeply interested."

"My uncle," resumed Mr. Gallagher, reverting to family associations, "was a captain of in-dustery. He was the Cracker-king of Ohio, and the luckiest man in the State. He took out a half-million-dollar accident policy, and was killed in a smash next month. He liked old things too—went to see the Sphinx and Pyramids in our Chicago cyclorama, and it gave him buck fever—it did so."

"I am delighted," I replied, "to find that you have the tastes of an antiquary."

"If that cat looks at me again," muttered Miss Hefty, "seems like I'd have to jerk her endwise."

"When I told the Bishop of Nebraska," continued Mr. Gallagher, "I was going to Rome to overhaul the antics, he says: 'They were a cruel race, always killing. Look at Julius Caesar—killed everybody—even Brutus, the only friend he ever had. "You too, Brutus," he said, as he drew his knife. But I says to him, 'Bish! wasn't killing the job he was hired for, and do you suppose any man named Julius Caesar wouldn't act white!' You don't know the Bishop, eh? If ever you hear him preach I bet a dollar and a quarter you'll say he's the champion uplifter."

THAT evening, leaning at my open casement, the slow wind

seemed heavy with undertones whereof the Day asks no question. A

capricious breeze fluttered the tree-tops, and about me all was

shadowy and sweet. In the silver marvel of moonlight the temple

stood clean-cut and luminous. How beautiful seemed the repose of

that ancient world whereof it is an eloquent fragment I Afar a

nightingale whispered its long-drawn passion. Oh, troubadour of

the night, what inspiration was there in your wooing! That

thrilling bird song was measuring the deeps of memory and

love—the love whose eyes, ages ago, beheld these same stars

shining. Was it not in such hours the Greek girls went to dance

with their gods, their white bodies flitting through the darkness

till, at the approach of day, they vanished, leaving the phantasy

of dryads changed to pale fir and tremulous aspen?

Closing the window, I seated myself before the fire and thought of Diana Macagni. Two days had passed, and whenever I met her, whether in the old hall or on the broad staircase or in the garden, I perceived new grace. I found myself growing absorbed in this meditative, grey-eyed girl—her words, her moods,—and the charm of her presence had suddenly become the corner-stone of my thought At each chance meeting the animation of her eyes seemed deeper, her smile more tender, as one whose soul is musing. So many things she said that sounded familiar, so many traits I seemed to recognise!

NEXT morning I found Diana Macagni in the leafy silence of her

garden. How handsome she looked, simply habited in a gown of

peacock-blue, lifting to the tendrils hands so fine and deft I

remember thinking that what they did could never be wholly

undone. About her was the aura that surrounds every beautiful

girl who walks in the rapture of youth. I read in her face that

she lived beneath lofty skies—in her voice were love and a

song.

"Signorina," I said, "in those pagan days whose memory delights us both, you would have been taken for some flower a god had breathed upon."

"Yonder, at least, is the house of the god," she answered, with a mischievous laugh, pointing to the temple. "Who shall say," she added with finesse, "that among yonder columns rustles no phantom breathing over and over the sospiro d'amore of some sweet-songed love!"

"You do not like our modern times," I observed, "when Caliban is master and Cerberus sits at the feast."

"And do you never long," she asked, turning upon me an intent look from beneath that fine straight brow, "to taste those brilliant days again ... to leave this staleness and go back to the wonder-world?"

"What is this waking nightmare," I ejaculated, "this walking and talking with things for ever vanished? To me the thought of your twilight is like stepping from terra-firma into space."

"Do you never," queried the girl after a moment's thought, "hear something calling you away? Have you never listened at dawn to the voices of fishermen—so far and faint that they come only as a murmur? Out of a greater darkness and from an infinity of time comes the whisper we all hear and few understand."

"Yours is a mind of ideals on fire," I exclaimed. "Were they a trifle more pronounced, we should call them madness. As it is, they are but fugitive fancies none take seriously. Let us come nearer the things of to-day. My companion and I have discovered the existence of a chamber under Poseidon's Temple, and we feel sure you are familiar with a secret passage leading to it. We wish to stand for a few moments within that sanctuary. If you will lead us there, you shall have the only reward you would care for. Professor Vaini and I will leave Paestum without delay, taking with us those Gallaghers I am sure you regard with little favour."

The girl cast disdainfully aside the flowers she had gathered, and facing me with blazing eyes and hot blood mantling, was about to launch a refusal as tremendous as the stroke wherewith her classic namesake smote an intruder.

My attention was diverted from this menace by the appearance of Professor Vaini, who, emerging from the villa, beckoned with that peculiar wave of the hand which to the chosen few meant urgentissimo. Then, with a stiff little familiar gesture, he buttoned his frock-coat as a duellist who makes ready. Behind him stood Danilo Macagni, with intent dog-like gaze fixed upon me, and I divined that the custode had yielded to the suggestion I had presented to his daughter without effect. I was quick to suspect that the Maestro, conjecturing Macagni's affiliation to the Chosen Few, had whispered one of those tone-words of occult cabala which in classic days swayed the wisest, and in the nineteenth century survived to influence their less-learned inheritors.

As I joined him he muttered—"Let us to the crypt," and at the words the custode motioned us downstairs into a broad cellar. Unlocking a door, he gave us each a lantern, and we entered an arched brick passage, so crumbling that in places it seemed ready to fall. My pocket compass showed that we were heading for the temple. We presently found ourselves in a granite chamber twenty feet long, in the centre of which was a marble altar whereon rested a meteoric stone. Beside it lay an onyx tablet covered with an engraved Greek inscription, of which I instantly took a rubbing. Between the two burned a flame in a bronze Etruscan lamp, whose ever replenished wick and oil kept alive the "sacred flame" in this "thinking-place" of Poseidon. In the wall was the indication of a staircase long since closed. The plaster with which this filling-in had been covered bore a Greek graffito roughly scratched while it was still wet:

"THE USELESSNESS AND FUTILITY OF EVERYTHING."

How ominous sounded these words, transmitted across fourteen centuries, the message of the old world to the new!

Our discovery was so tremendous that Vaini and I were overwhelmed by it and thrown off our guard. We both forgot the open door where the passage led from the Salati cellar.

There was a quick footfall, and Mr. and Miss Gallagher stood in our midst. "I guess, sir," he remarked to me with a genial smile, "that this is the surprise of your life. I was watching you out of the tail of my eye; and when you disappeared down the cellar, I says to Hefty, 'You may bet a dollar and a quarter he's put on his forty horsepower. The Professor's right down to business, and there'll be no cloves on his breath to day.' I call this a cu-rio-sity. Makes me feel like I must learn to eye-search these old places."

As he spoke, his daughter stepped forward, and saying, "Idolatry is a thing I despise," blew out the sacred flame. And at the instant that frail spark expired, I heard in the air a strange little sound like the snap of a breaking wire.

"Sporcaccione!" whispered Vaini, his eyes red with passion.

"I guess I'm the top bubble now," cried Miss Gallagher, with a shrill laugh.

A moment of deathly hush followed. We were silenced by an act of such refined savagery.

Miss Gallagher resented, without understanding, Vaini's exclamation. "Tell your friend not to get superheated," she sneered.

"Tell him to come off the grass and talk sense," added her father, who likewise attributed no gracious meaning to the Italian word. "Come, brothers, let us back track into the open."

As moved by some common instinct we hastily returned to the sunshine, where stood Diana, her colour faded, her eyes wet. Could she have anticipated what had happened?

And at sight of us the grey parrot extended its wings and screamed "È una Porcheria."

HOW often I regret not having brought from the crypt for an hour's inspection the tablet which in that brief glance seemed of onyx graven with an archaic Greek inscription of four stanzas. It still rests on that altar of sculptured sirens and sea-plants whereon Poseidon's flame no longer burns. The authorities have caused the entire passage to be filled, and who can say how many centuries may pass before human eyes again behold that labourer's scrawl.

"The Uselessness and Futility of Everything."

The translation of the rubbing I had made presented no difficulty to my former tutor. In his opinion the onyx scarab had been executed at Syracuse, since it shows the emblems of that city as borne on its tetradrachms of B.C. 270. When Baal-Kareth sailed, Stonehenge had been standing eighteen hundred years. The "deathless sun" perhaps refers to the midnight sun. The "undiscovered sea" may have been the Mare Germanicus of the Romans. The phenomenon of the cloud is frequently seen in Norway in midsummer, and it is probable that the voyagers spent an early spring navigating Norwegian fiords. Here I have rendered Vaini's Italian into English.

I, Baal-Kareth, priest of the Sun-god,

Sailed to the north in search of the deathless sun.

With me were Imlico the navigator,

Hiero the Phenician, Timoleon son of Lysimachus,

And Cisco the singer. Mariners also were there

Knowing the meaning of wind when it whispers,

And diviners to interpret stillness when there is no

sound.

We, readers of the Book of the Dead,

Sought to behold the eye of the timeless god.

Our ship cut the waves like a thing of life,

Our canvas was a sun-browned pyramid.

The oars rose and fell through spacious hours,

The undiscovered sea we sailed was a turbulent waste.

There were rocks like a mouthful of ravenous fangs,

Strange birds soared between sea and sky.

A year passed, and one by one we crushed the long days.

We saw the shadows rise and wander on the mountains,

We beheld the snows on the white roof of the world,

And a cloud held the light of the setting sun

Till the light of sunrise kindled upon it.

The harper sang: "Such is the fair of face, rising in gold,

Day dawns, night recedes, a new soul is born."

In remembrance whereof and in homage to Poseidon,

Who cherished our strength and heightened our skill,

This flame is lighted to continue deathless and unextinguished,

A spark of the Sun-god, imperishable as the wind on the

sea.

May peace be the Sun-god's portion and Poseidon's

So long as the wine of eternal youth flows in their

veins—

So long as this flame burns through uncounted ages.

THAT evening when we gathered at supper I shared the indignant

mood of the Italians. If the Gallaghers were conscious of having

chilled their welcome, they did not betray it, the daughter

dividing her attention between a dish of spaghetti and a Chicago

newspaper, while her father, after renewed complaints at the loss

of his luggage, engaged me in conversation.

"It's hunger gives a man his razor-edge," he remarked, helping himself to that delicious minestra only Italian cooks can prepare, "and while the food in this country is curious, it is not so curious as the people themselves. Did you ever notice an I-talian crowd. Most remarkable live-stock since Noah's collection. Not got business sense enough to lead a donkey to water. Slow in all things but one. A lady friend who lives in Rome said her landlady had three sets of twins in four years, and the doctor laughed when my friend said, 'Doc, you will have to fix a speed limit.' Coming down in the train I rather surprised a priest explaining my fertiliser. Said I, 'It will make the flower-pattern on your carpet grow a foot high—scent, dewdrops, and all so natural the bees will fly in for honey.' I wasn't all joking, however," he added, handing me a tiny bottle. "Here's a vial you may have for experiments—it will burn a hole in cast iron, and make an alligator turn pink.

"There's my friend the Bishop of Nebraska, he's different—just loves a joke. We met five years ago on the Denver Railway, and I was surprised at his addressing me by name. 'I wonder how you know me,' I says.

"'Well, sir,' he answered, 'I saw by the papers you were expected, and notice that you have just had an Omaha hair-cut, that you are smoking the cheroots sold at Council Bluffs, and that your umbrella still bears a stain of red Chicago mud.'

"'Do you mean to say,' I exclaimed, 'that's all the evidence you had?'

"'Well, no,' says Bish. 'Fact is, I saw your name on the gripsack you gave to a porter.'"

IN the garden Miss Gallagher advanced to meet me, whistling

I'm afraid to go home in the dark.

I remember pausing to observe the soulless mechanism she had caught from her father and reflected in herself.

"I guess I riled these folks some yesterday," she began, "and perhaps what I did was not white. What I saw of these Italians out in Illinois learned me they are like their own heathen gods. They hate as long as they remember, and they never forget. At home I like to have the housemaids come and sit in my bedroom and do their sewing, but these people ain't human. Poppa wants to have me marry a nobleman, but I says I'm enough sight better off the way I am. I don't want any bought or hired husband. I guess our luggage is bound to turn up to-morrow—I telegraphed a gentleman friend in Naples to give the American Consul rough on rats if it's not found. Before we leave I want to square Devil Macaroni and his daughter. You see, I have a forgiving nature, as a hard-shell Baptist should, and if a thousand francs—"

"Miss Gallagher," I interrupted, "this is not a case for money."

"Well, don't you get snappy," replied the lady. "You remind me of a man I met in a street-car a couple of years ago. I handed him our best tract, Abide with Me, but he looked at it stiff, same as you, and gave it back. 'Thank you,' he says, 'I'm a married man.' 'Well,' I says, 'polite manners are getting scarce as hen's teeth.'"

I HAD begged Signorina Macagni to meet me by the sea, whither

I now walked with Vaini's interpretation of Baal-Kareth's scarab

in my hand, reading, as I went, his quaint picture of days when

galleys, creaming at their bows, came and went—

storm-tossed, weather-bound, coasting these shores.

Presently I beheld her, and, approaching, said, "This inscription cannot be new to you: pray come and explain it."

We seated ourselves on the edge of a crumbling wall by the sea, and taking my words very seriously, she glanced at Vaini's translation and said, "Can you write down in black and white a whisper of the gods? Such things are made to dream of and love, not to be cheapened by overmuch talk! Rather listen than speak. There is in it a sound like the drowsy oars of Charon, or the muffled beat of a heart that throbbed with your own before your present human semblance was born. 'Strange fancies those,' I hear you say—yet to me no more extraordinary than homing birds."

"Such vague and elusive impressions," I answered, "are common to all—more lasting with some than with others."

"Can you speak thus?" interrupted the girl—"can you have forgotten?"

"What," I asked, startled into gravity, "do you expect me to remember?"

"I might expect you to remember me."

"My dear signorina," I murmured, taking her hand caressingly, "you brood upon things that keep the nerves high strung till the cords break and the harp no longer speaks."

At the word my eyes rested upon the ring she wore, an uncut ruby... and at the sight came to me words as though I once had spoken them... I give you this drop of my heart's blood. It seemed as though, across the distance of ages, I had heard a door open and shut.

"Since you remember the ring," cried Diana, "you will not have forgotten a name?"

"We called him the Greek—il Greco," I said, the word springing to my mind. "I verily believe it was none other than Poseidon!"

"Yonder," assented the girl, "in the street whose pavement still passes the temple, I stood. It was the festival of the sun-god—the day when each year the town made sacrifice of a maiden. The choice had fallen upon me, and, amid augurs and musicians and dancers and laughing soldiers, I was urged towards that retreat the merry priests called 'The Meeting of the Lips.' In those days you said you loved me. Had you approached the sanctuary by another way? I saw you speaking with the god—he looked a man like yourself. What followed? I heard Poseidon scream, you caught me by the wrist, and along an alley we fled. A shower of sparks blinded me. I wonder—did we marry and were we happy at the last?"

I had risen to my feet in excitement, and now, as though called into being by these words, a moaning floated from the mountains behind me, seeming the reverberance of some gruesome story. Black clouds had suddenly gathered unnoticed.

"We must instantly return to shelter," I cried, cutting short her wild phrase—"a tornado approaches."

As we hurried on, the gale burst, the rain pouring in our faces and the wind shrieking a frantic warning. I laid my hand upon the door of the Villa Salati, when, to my amazement, it fell away with a crash, and I perceived my hand to be resting upon a marble balustrade in a narrow street whose houses raised their roofs so high that the sun's rays never touched its pavement. There were latticed windows, and doors adorned with uncouth locks that opened into tiny courts. Fresh painted upon one were the words:

HOSPES PULSANTI TIBI SE MIA JANUA PANDET.

(Guest, to you when you knock, this my portal will open.)

At a cook's shop hung a cauldron whose savoury contents a

scullion stirred. Within, amid the rattle of dice, some one was

telling a story, the climax whereof was received with tipsy

laughter and stamping of feet. Above the door hung a stone

fashioned like a purse, with the legend—

"Give me what is under your mantle," cried the starving beggar.

"It is only a stone to throw at a dog," answered the rich man;

and as he spoke, the purse changed to a stone.

I MOVED to a broader street, where an odd mixture of types

came and went—Roman, Greek, Phoenician, Etruscan rustics,

and a single black man, who glanced at me as though stranger than

himself. A tawny woman, a veritable Juno, vendor of sweetened

wine from a pigskin slung over her shoulder, came by, nude to the

waist, her splendid breasts swaying as she walked. A clamour of

beggars shrilled from the steps of the temple, whose appearance

was completely transfigured, its surface being covered with white

marble-dust stucco, whereon were painted heroic figures. Traced

on its polished walls was an epitome of kings, priests, soldiers,

and sages. Here was indeed the house of a sea-god, and the light

of its Doric beauty a consecration to the divine spirit of

adventure and discovery. Hither came the homage of those who

beheld upon Poseidon's altar a flame lighting the way toward

things that in all ages men have given life to reach.

Behind me I still heard the rattle of dice. It was the publican who had followed, dice-box in hand, and who, prefacing with a careless "Salutem," remarked, "Here comes the duumvir Aulus Veius," as a spare, vigorous man passed, holding a gold-headed cane. "Yonder," he added, "is Speratus of Tarentum, who, when he condescends to dine out, takes his own cook. Those soldiers have marched far—see the drops oozing from their buskins! Hither walks Cynxthos, a Corinthian sculptor, and with him Orchomenus the poet. That lame man is Vanustus the tax-gatherer, wearing in his ears his grandmother's imitation gold loops. He commends himself to Suedius Clemens the magistrate. That pretty woman, beneath whose mantle the sandals glitter, is Alleia Sabina, who last year eloped with Tintirius, trainer of athletes."

I was conscious, as I listened, of having touched the top notch of Vaini's dangerous experiments, and of having strayed into a domain of strange gods. I remembered my former tutor's theory that, as there are threads of the morning's opalescence still lingering in the twilight, so the inhabitants of an extinct world may awaken, after a thousand years, a fugitive resonance of days once lived and for ever after loved.

At my side stood Diana, statuesquely at ease in classic garments and amid surroundings that to her were familiar. Instinctively our hands met, and her touch brought the fanciful thought that within me was rekindled the flame I had seen extinguished a day before on Poseidon's altar.

On came the music—near and nearer—till the air thrilled with exultant melody in honour of Poseidon's annual wedding. Pipes, flutes, forest horns, and the rhythm of many voices touched the hour with joy—a love-song mingled with the sunshine—a score of cymbals beating the clash of Eleusinian mysteries. That fine acclaim swept skyward to the stars and martial glory.

Beneath it pierced a note of human triumph, as though the life of the world trembled in passionate emotion. The men's deep voices caught the strain from girlish lips and swelled it to thunder. I was half conscious of some superb illusion, yet the day was real: I could smell the incense, and see the white dust rise beneath the dancers' feet.

Then Diana raised her wistful face to mine, with a tremulous whisper: "Save me!"

It was for her the amorous touch of Poseidon burned and waited, and I remembered the narratives of pagan days—of the jests of merry priests of Osiris and Zeus resounding down the mirthful centuries, of women beguiled with offers of the love of a god. It was easy to imagine the bargain with some opulent votary.

I left Diana with the eyes of the hushed and halted procession upon her, and entered the temple unobserved. From behind a curtain came the sound of laughter, and a sonorous voice said in Greek, "Calventius, the philtre... my lips are dry with waiting."

It was my opportunity. Springing to the door of a cubiculum, where amid cushioned lounges and wicker chairs and steel mirrors was a table spread with cakes, fruit, and a flagon, I emptied into the wine Mr. Gallagher's elixir that was warranted to burn a hole in cast iron and make the flowers in a carpet pattern grow.

The next instant the god, in whom I beheld the typical young patrician, came into view, clad in crimson tunic, bare-headed and bare-armed. As he filled and emptied a goblet, an amorous sun-flush glowed beneath his olive skin. His movements were those of an athlete—graceful and quick. I doubted not it was some youthful Roman, lusty, persuasive and rich, personating "II Greco," the Greek Poseidon.

Then suddenly he beheld me watching him, and at the instant Diana appeared urged on by the priests. The sea god fixed his mute astonished gaze upon me, and within a moment of swallowing the love philtre his eyes became bloodshot, his jaw fell, and he clutched convulsively at something he could no longer see.

I caught Diana by the hand, led her lightly past the priests, and with her fled away toward the nearest city gate. There was an outcry from the people like the roar of animals robbed of food. But high and clear above all imprecation rose the shriek of "Il Greco" as Mr. Gallagher's elixir devoured him.

Before us stood a patrol of crimson tunic-ed soldiers—the laughter-loving—a-glitter with brass and steel, poising their javelins as in our despair we halted. How distinct in those faces was the intellectual cruelty of Rome! At the sight Diana placed herself dauntless and superb between me and the lance-head.

"Tear her away and smite!" vociferated the priest. "Hath he not slain Poseidon?"

I knew that the moment of death had come—a death to be envied, instantaneous, front to the enemy, with Diana beside me. A centurion leaped to the soldiers and snatched a spear.

"Only the love-stories told in myths are happy," sobbed Diana. "How tragic is their reality!"

As the javelin flew I gazed deep into those fathomless grey eyes, and bent passionately toward those upturned lips. And we both whispered—"FOREVER."

THERE was a violent crash overhead, followed by a shower of

broken tiles—then darkness. The Villa Salati trembled,

lightning-struck, and its closed door swung open. Before me stood

Danilo Macagni, Vaini, and the Gallaghers, flying from the

smitten house.

"At which of us was that bolt aimed?" ejaculated the Professor, glancing up at the shattered chimney.

"I guess, sir," drawled Miss Gallagher, addressing me, quite unperturbed, "that long-distance message was meant for your lady friend."

"If your life is not insured," interrupted her father, "let me recommend the Spread Eagle of Chicago."

"The vengeance of Poseidon!" muttered Macagni, baring his head to the storm.

MR. GALLAGHER at first explained my hallucination as the effect of a violent thunderstorm upon an excited nervous system. But yielding to conviction, he twisted his mouth into corkscrew curves at the narrative of my meeting with Poseidon, and examined the empty elixir bottle with a long guffaw.

"It was a close call, sir, but, by ginger blue, you gave him a nut-cracker squeeze," he exclaimed, "and I guess the sea-god must have thought something had dropped on him when he got back to his ranche. When I think of his swallowing that medicine I feel like I'd put the leg of my chair on his foot and ground it good and plenty. It must have been a happy life," he added, reflectively stroking his chin, "to be a tinsel-junk god in Roman days. Same as a Trust-buster now out West—the cream of fighting and love-making, and gather in your cheques as regular as servants' dinner. Your friend Poseidon had all the birth-marks of Olympus, just as a chicken raised in an incubator always tastes of the machine. I bet a dollar and a quarter, had Poseidon lived to-day the boys would skin him clean and tattoo the stars and stripes on his bare back."

In the excitement of that memorable noonday the luncheon-dinner was forgotten and the Ave Maria rang at sundown as we seated ourselves before a cold supper. Miss Gallagher had delayed it by asking to change rooms with Diana Macagni, a pane of glass having been broken in the spare bedchamber.

"This adventure of yours will make a sensation in the papers," pursued Mr. Gallagher, swearing softly to himself as one that breathes a prayer. "Out in Chicago we like a story that's razor-blades in front and barbed wire behind. I had a warm experience myself when I was a cowboy out in Wyoming and saved our cattle by driving them across the front of an advancing prairie fire. I must have looked like a scare-head column in a newspaper. There was no time to figure my chances. Had I tried to drive from it, I'd have been roasted quick as a once-over shave."

Supper ended, Miss Gallagher rose to prepare for to-morrow's departure, the stray luggage having been found.

"She's a fine girl," remarked the Trust-buster admiringly. "Looks pretty well fixed in parrots," he added, alluding to the plumage in her hat, "and her smile doesn't wash off. I guess it frosted you some when she blew out that light. What's a light for anyway, if you can't blow it out and light it again? That's the way I seem to sense it. Yessir, she's the image of her mother thirty years ago. I was a railway manager in those days, and Colonel Revere, my father-in-law that was to be, kept the finest hotel west of the Mississippi. One evening the young people were eating philopenas. You know that means dividing a double almond, and whichever first says philopena! to the other next morning gets a prize. I asked Miss Revere to eat a philopena with me, and as we opened a dish of almonds without finding a double, at last she says—'Bite off the half!' and held the almond between her little white teeth while the crowd laughed fit to crack the paint. I felt skittish before so many, but as I bit I whispered, 'Wilt thou?' And her lips trembled as she answered, 'I wilt.'"

"Now, sir, how was that for neatness and despatch?" and the Trust-buster leaned back and laughed hilariously as the Olympian Jove remembering Leda.

THE day had taken on for me a subtle meaning—its

homespun shot with gold and spangled. A vine which covered the

pergola of Diana's garden reddened in the crimsoning October, and

seemed a semblance of the morning's vision. I beheld with

amazement the marble basin which was that I had seen in the

alcove of ancient Paestum mirthfully called "The Meeting of the

Lips," the water still splashing into it, basin and musical

cadence unchanged. Faintly came the resonant humming of Diana's

lute, rich and sweet as the lyrics she remembered. Had some

strange sense been preserved to her—some soliloquy of

whispered sound—as about the Gothic aisle floats and

lingers the Cathedral-sung AMEN? Amid the melody of those accords

sounded the delicate carillon of a clock, as though Elfland

chimed in the harmony of Earth.

I found Diana in the familiar hall, sitting with the hushed lute in her hands before a crackling log fire. The sunset, sifting through leafless branches, touched its black panels with amorous fancy that bade me speak.

"I cannot take my thoughts from that marvellous Pageant Masque," I said, seating myself near her. "Was that hour only an instant, and did some strange telepathy make the illusion identical for us both?"

"It was an expression of the Sixth Sense," she gravely answered. "Were another octave added to our hearing, one more range of cells developed in our brain, our perceptions slightly more attuned to Nature, we should lie strung and keyed to receive the touch of a phantom hand. Our eyes would be opened, and we should eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge and be as gods."

"Do you mean," I jestingly asked, "that your heart and mine were beating two thousand years ago, and that this morning I poisoned a Roman ghost with American elixir?"

"Have you never walked again in after years with vanished loves and lovers?" cried the girl, with smiling temptress lips. "Has love never entered to you unbidden, with footsteps of divine surprise? The bandage which is upon your eyes has been lifted from mine, and I know that it is not the Past that is dead, but To-day that is cold."

She had laid aside the lute, and risen to meet me, her face flushed with the light of youth, her brown hair touched with a shimmer of silk. I felt, as never before, that love often leaps into being in the pang of a tragical hour.

"So far from cold," I answered, "we may find to-day unpleasantly warm if we have to reckon with Poseidon's hate. Among us we have blown out his candle, given him a poisonous dose, and stolen the girl he awaited. The teeth of the gods bite deep. Your father declares that in remaining here both you and he are braving an unseen but certain death."

"Ages ago you saved me from Poseidon: will you save me from him again?"

Something in my heart answered Yes, and I am sure that Diana heard.

"Here in this Hylas-haunted shade," I exclaimed, "your heart will break! It is for me to place you beyond the Demon's malice. Join me at Vaini's villa in a day or two... we shall be married after the longest-known engagement, and I will take you far from this fear of dying, far from this incubus of malignant phantoms, to the gentle heart of Nature."

We had drawn close together, so close that a wisp of silky hair brushed my face, and I breathed the ineffable fragrance of her lips. Could a kiss, I wondered, be blown across the centuries?—and thus musing, a hush fell on us like the magnetic silence that follows when sweet and passionate music ends.

I HURRIED next day to Vaini's villa, where this characteristic letter from my former tutor flashed across my preparations:—

Translation.

Pesto, November 1897.

Friend of My Soul,

What are we but playthings of a reckless fate! Was it a viper, or did I indeed hear in my sleep the laughter of Homeric gods? She whom our harvest knew not sleeps with the rose. You remember that the Signorina Gallagher (cagna d'inferno) insisted upon exchanging rooms, and I shall always believe the shaft intended for the one smote the other. Why might not Poseidon make a bull's-eye on the wrong target?

Carissimo, I noticed all yesterday the tragedy that lay in her eyes. Perhaps better than we, she knew. This solitude, with its sense of oblivion, put thoughts in her mind and brought the dead to life. Was this poetic riches, or only dust? Now she lies calm, untroubled, marble-white—a Victory superbly statuesque in death. Povero Macagni! He talks of the sorrows of Mary, of tears and the kissing of feet. I tell him he must look beyond the stars.

Devotissimo,

Vaini.

IN the light of the twentieth century, Poseidon's shattered temple attests that man's master-thoughts are deathless. Far from the eddies of our little bustle it marks the intellectual supremacy of Greece. About it birds sing all the day and roses bloom all the year. Its immortal garland thrills with the Old World's delight in colour. Quaint fancies drowse and nestle in its shade. Its solitude is reverberant with music and laughter and the tread of many feet. And I marvel if the heart of Poseidon still warms to the murmur of the sea-shells he loved?

The mountains keep the secret of their ancient days, as enchanters kept their mysteries and listened to the heart-beat of perennial youth. The rim of the bending sky rests on these shores of lyric fame. A sense of dominion thrills and inspires the air. A falcon—silver gleaming in the sun—circles with bladed wing above the memories of that silent plain. There is a soft clash of great sunflower leaves. And I meditate upon the Nemesis that underlay Greek tragedy, and that to this day shatters our purpose and stabs us to the heart. Absit omen, muttered the Caesars, and mankind still trembles at the shaft sped by a force that is blind and irresistible.

Each year I return to walk in the places whose horizon Diana Macagni knew. I stand an enchanted hour in her garden, and gaze on the sun-washed sea. I pluck the rose of joy—Toujours—that blooms and fades, while its fine clustering leaves of grief—Jamais—are ever green. And sometimes, in the twilight, I fancy again the wings of that extraordinary vision, and catch an accent of vanished things.

I write this in the soft-shod quiet of Vaini's study, amid its books and tapestries and classic fragments. These walls can never lose the note of brilliance of his phrase. I dip into the box wherein he kept the record of his psychic asterisms whose yellowing pacquets are resonant of marvellous success and failure. Before me are his amber chessmen—a tiny corps d'elite—wherein he read a semblance of that intellectual force which achieves results, and bends to the master's will, and solves extraordinary problems. He applied the devotion of a lifetime to the weaving of curious arabesques, and his touch was like this Italian sunshine, tipping with splendid light.

As the song is the joy of the singer, so work lives in the life of the worker. It was thus that, searching for the fulcrum Archimedes imagined, Vaini traversed illimitable paths. The aura of his studies drew to the conclusion that even an hour's meditation upon known things points inevitably toward the unknown. He conceived the subtlest theorem of life to be a reflex of the deathless mystery of the stars, and beyond all our experiments lay a groping after the secret of immortality.

Through midwinter evenings I muse upon those happy days and watch the firelight's tracery that leaps and fades and kindles. About me is the phantom consciousness of an outstretched hand... Diana's faint caress, or the lurking menace of "Il Greco"? Amid those vague and visionary happenings we call "real life," many have seemed less real than those brief instants I spent in Roman Paestum.

In Vaini's garden the Toujours ou Jamais roses run riot on the cloister wall, and I know that never again shall I stand within the velvet dark they cover. Up and down the flowering walks I stroll between orange-trees and marbles and faint, far memories. There is about these ingle-nooks a harmony akin to the divine hush of silence. Far down the pergola, beyond silver grass and jewelled leaf, the blackbird sings his ecstasy. Across my sundial the shadow pencil moves, and that Roman stone speaks eloquently of the world Diana loved. A shadow lengthens, a grape-vine bends, a bird-song thrills—and behind them moves a presence. It is like the glimpse of a white statue in the perspective of some dim corridor, whose outstretched arm beckons and allures.

It is Diana, and I know that we are hand in hand for ever. I speculate upon our phantom past and grope to find its least, dear trifle, thinking of her with the anguish wherewith we remember unattainable dreams. Each sweet, delicious day reveals her, with approach as subtle as Autumn coming to the wood. I dare not speak, lest that faint silhouette should fade. When firstling buds awake and mating birds return to fill the air with heartbreak, I know that she is near. In the soft calando of the breeze I hear her whisper, as though something were trying not to cry. Can I doubt that she is teaching me love and hope, things that children and beautiful women know? I see before me the fine lines of her graceful figure—her face of power and charm, radiant and immortal. My thought flies to that darling memory when, superb and undaunted, she placed herself between me and the Roman javelins. And more profoundly than ever in life I gaze into her eyes—those wistful eyes that saw so far beyond the things of earth!

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.