RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

IN May 1875, while reading law in New York, I received a letter from Professor Vaini urging me to meet him in London during the following month for an experiment of extreme importance. He called it "A Glimpse behind the Veil," and I was surprised to infer that he was bent upon a hunt for buried treasure. He mentioned a Roman Votive Spring, and avowed the purpose of penetrating a field mapped only by conjecture. "Come at once," he added, "do not hesitate or delay, and together we will hear the rustle of unloosing wings."

I had been in correspondence with Vaini ever since my Roman studies five years previously, and today, turning over his memoranda written during those intervening years, I note with interest that his multitudinous activities had brought him to the verge of discovering the origin of the ordinary elements at whose threshold scientific research is now trembling. I need not say that I was flattered at being invited to share a purpose of Vaini's vivid and illuminating life. I longed to renew with him my investigation of psychical phenomena, and immediately arranged to take my two months' holiday in England. Before me lie Vaini's jottings upon our adventure, and I shall use them to supplement my recollection of that enchanted garden which thirty years ago was Yesterday. It is my aim to write a restrained narrative of our experience, as to which it has always been my belief that Vaini and I grazed the confines of a world beyond our own. If I seem to presume upon my readers' indulgence, it should be remembered that the truth is sometimes evolved from facts in themselves incredible.

When we met in London, he explained the scope and aim of our quest. Like a true artist he loved his leisure, and I listened for an hour while lie painted his scheme as only one can do who realises the atmosphere of thought. It was always a delight to follow his method, for his phrases were of the diamond edition. He believed that from Moses and the prophets the greatest things have been accomplished by self-illuminating light, and now drew the outline of his project boldly, leaving it to Time, his fellow-worker, to fill in accessories. Prom youth alone against the world, Vaini had entered the arena as it were with no weightier battalion than a set of intellectual chessmen—a tiny corps d'élite—yet at his touch so animated with supernatural prowess, that when marshalled against earthly forces, the array seemed not unequal. His inductions were reflected by many mental mirrors; and of all men I have known, none possessed in an equal degree the art of captivating imagination. His finest inferences rested upon an anticipation of that belief in universal symmetry which in our own time Science is demonstrating to be the fundamental truth.

He began by reminding me of the half-dozen Votive Springs thus far discovered in Italy. Students of Roman archaeology are familiar with the custom which prevailed from remote antiquity of casting offerings into such lakes or springs as were held sacred, and especially into those whose hygienic properties attracted invalids. Whoever wished to propitiate the deity, or give thanks for a cure, threw into the water according to his means. The discovery of a Votive Spring, which is usually the result of accident, is an event of great numismatic importance. At the top will be found the opulent offerings of Imperial days in a layer of gold coins of the Caesars. Beneath lie silver vessels and moneys of the Republic. Under this rests a mass of copper and brass—coin, graven figures and kitchen utensils. Lastly is uncovered a bed of flints and arrowheads, the offerings of the prehistoric elect.

"It is well known," continued Vaini, "that a Votive Spring of immense antiquity existed at Aquae Sulis, the modern Bath. When Titus founded there the colony which by reason of its warm mineral waters he named Aquas Calidae, the settlers found a local deity whom they seem to have accepted as the genius of the place. I spent a week at Bath last summer, comparing the references of ancient writers with its topography, and in the Museum I observed a tablet engraved:

FLAVIAE EPICHA(RIDI). SACER(DOTIAE).

DEAE. VIRGINIS. CELESTI(S).

(To Flavia Epicharis, A Priestess of the Celestial Virgin.)

"Observe that this Virgo Celestis can be no other than the Carthaginian Astarte whose worship was introduced by Phoenician traders at a time when Britain was unknown to Rome."

"Have you any knowledge as to the whereabouts of this spring?" I asked.

"I have placed it within the surface of an acre," answered Vaini. "Curiously, it is at a mathematical point on the hillside where the shadows of yesterday's sunset and to-day's sunrise meet."

"Were this treasure found," I objected, "the Government would snatch it from you."

"The Government," he answered with feverish intensity, "cannot snatch the credit of the most remarkable archaeological discovery of the century in England."

"But you are not even sure there was a Votive Spring."

"Its existence," said the Professor, "is established by the writing of Sulpicius Arens, a Roman priest who perished in the destruction of Aqua; Sulis, and who some years previously addressed a letter to the Flamens of the Celestial Virgin in other lands. He tells his colleagues that, upon the rising of the Britons, the Spring will be buried. He defines its position with reference to the river, the city wall, and the Vicus Sacri Pontis."

"Dear Master, you seem very familiar with Aquae Sulis?"

"Yes, for I possess one of the three existing copies of the writing of Sulpicius—the work of a monkish hand, which in 1499 Ormès discovered in a mutilated condition, pasted in the leaves of a great Psalter."

I knew that Vaini's mind was an instrument so keen and adaptable, so expert in opening intellectual paths, as to be adequate even to a fantastic achievement. The next day found us established at a little inn beside the Avon, on the outskirts of Bath, which for more than a century had borne the name of Castle Joyous. My companion had hired it for a month, knowing that we should find there greater freedom and privacy than at the fashionable "Pump." The first I saw of Castle Joyous was its peaked roof splashed with emerald moss. Its walls were two feet thick and its roof-beams black as ebony. Beside the house was a little old garden—a tangle of crystal roses that even in their abandonment amid great edgings of box would have pleased the most learned rosarian. Looking thence into the sparkling Avon, one might behold disused stepping-stones beneath the water and fancy on them the noiseless footfalls treading to and fro. Who could say they might not lead half-way to our imagined goal!

Mrs. Oldcorn served for me a supper of grilled bones and a bottle of the Espiritu Santo sherry I had brought from London, and a "Hamlet of eggs" for Vaini. His diet was limited to fish, eggs and vegetables, and I had so far brought myself to conform to his abstemiousness that, after finishing my steak or chop, I usually shared his brain-building food. Our landlady was one of the listless-eyed and tired cattle of her class, and a liberal consumer of the boiled mutton which thirty years ago figured upon English tables. "Brave and 'artsome, that's what I am," and might have added close-hauled on week-days, till on Sunday afternoons she acquired what sailors call a list to port.

The next morning, breakfasting upon Stargazer pie, which is fish pasty, with the heads of the fish peeping through the crust, Vaini and I addressed ourselves to the serious features of our undertaking. "It is true," he began, "that if touched by a calculation of absolute nicety, the hiding-place may disclose itself, as a heart wrung by intense emotion reveals its secret. The doors of knowledge are sometimes opened by the simplest key. On the other hand, our search for this ton of gold, which I have come to regard as my reversionary heritage, may be dangerous. Your real artist," he added, producing a curious mechanical appliance, "does not work with borrowed tools; and after prolonged experiment, I have constructed this revolving drill of the finest steel, with a receptacle behind the point. Its boring power into the earth is only six feet, but in my belief the upper crust of the treasure must be nearer the surface, and my apparatus has the advantage of being so compressible that it can be carried under the arm like a telescope. But what is of first importance is that we guard against that same agency which has played havoc with so many searchers."

"We are not the first, then, in this bed of nettles?"

"No. Sulpicius Arens tells his colleagues that attempts were made during the reigns of Constantine, of Julian, and of Valentinian—all violently frustrated by the Virgo Celestis in the semblance of a swarthy girl. In 1212 an Italian prelate named Marsilio Sarpi, visiting the Norman Cathedral of Bath, explored the fragments of the Roman Aquae Sulis. He was fascinated and debauched by a beautiful dark girl, and being seized with remorse, became smitten with madness. In 1505 Ormès, the renowned soothsayer of the Borgias, invited his Venetian rival Almodoro to go with him into Britain, and the latter tells the story of what befell. Measuring and digging amid crumbling vestiges, the daughter of their hostess, a sombre-visaged young woman, confided to Ormès that at a particular locality then still called Vicus Sacri Pontis, the water oozed from the ground. Thither one night she conducted them, with the result that Almodoro was violently stabbed, he knew not by whom, and Ormès left dead by the roadside smitten as with the club of Hercules. The Bishop of Bath caused Almodoro to be cared for; and the dusky maiden having disappeared, her mother's tongue was torn out and her arms and limbs crushed—after which it was discovered that she was not the girl's mother."

My companion had given me material for reflection, and I strayed away for an hour's thought in the garden. There was an orchard beyond, its blossoms still sparkling with dew, and on the hill-slopes stretched billowy masses of chestnut bloom. At my feet were feathergrass and cornmaidens and Turk's-cap tulips. It was a brilliant day, and across the meadows and against the forest the advancing sunlight was spreading its eager fingers. I remember thinking it is on such a morning we are made to feel that Nature alone has never lost the strength and beauty of its childhood. There was the swift and rippling music of bird-notes in the air, and I knew that so long as birds shall make music the heart will be glad. Were they too filling the tree-tops with some delightful message, some consciousness of an unseen yet thrilling possession such as the ancients comprehended in dedicating their groves and springs? Suddenly the bird music ceased, and in that instant's hush I seemed to hear the eloquent silence speak, and became vividly aware of a presence behind me. I turned with a strange heart-spasm,—and there, in the open doorway through which I had passed, stood a dark girl, a splendid flash of sunlight in her eyes. At the sight something within me caught fire. To this day I can see the statuesque poise of her body and the black coils of her braided hair and the silken threat of her haunted eyes, unafraid and unflinching.

There, in the open doorway through

which I had passed, stood a dark girl.

Yet what had caused me this emotion was but a tawny young woman, with great twists of soft hair, habited in a flamingo-red bodice, a striped green skirt, and here and there a fringe of white. She was leaning forward, watching me with the mystery of a sleeping passion. The wild thought flashed upon me that here was a repetition of the fateful force whereby, through centuries, every comer had been smitten and baffled. Was hers a face I had seen before, or only dreamt of? It was a sad face, as though weird memories crouched in its twilight. And musing upon the danger thus suddenly sprung into being, I wondered how one thus strangely summoned from remote and half fabulous regions would fare in a tragical collision with Vaini.

I walked towards her, looking beyond her face and the shining gold coin that hung at its side—seeking to reach the mind of eager devices and desires. And instinctively the cry sprang to my lips: "You here... already!"

At the words she startled with a flush of amorous colour, like some strange being that for the first time hears the human voice. Then, in a murmur wherein it seemed familiar accents lingered, she answered:

"Yes, it is I. Did you not hear me calling?"

I LOST no time in seeking Vaini in his room, where he sat before a map of Bath marked 1690. Between his fingers was the familiar green pencil with which in a jesting moment he once told me he did his mental indexing. I knew he was busy weighing the evidence of an unseen and half-forgotten world, and remember wondering at the moment whether within an Archimedes of purely intellectual force there must yet linger something earthly—the flying eagle's shadow skimming the ground.

I lost no time in seeking Vaini in his room,

where he sat before a map of Bath marked 1690.

"Professor," I abruptly ejaculated, seeing that he anticipated my ill news, "I have beheld our traditional and inexorable enemy. I verily believe." I added, sinking into a chair, her words still ringing in my ears, "that we have before us no mere human potency."

"It is true," he replied, with his invariable suavity, "that this Pandora Miduvel is the historic dusky girl."

"You already know her name!" I exclaimed.

"I saw her yesterday, when I too divined the meaning that looks from that face. I sent for Mrs. Oldcorn, and with my imperfect English learned something of this strange niece of hers—if relative indeed she be. For all her gipsy ways, she is a young woman of education. But, caro mio, you seem troubled. You would not falter when already we stand within the enemy's lines. It cannot be doubled that a fantastic treasure lies at our feet. My effort for its recovery shall be a symphony in colour, a sonnet in porcelain, a classic of its kind. On this map I have traced the lost course of the Vicus Sacri Fontis. Sulpicius gives ingeniously the point of meeting of two lines, one a prolongation of the western city wall, the other drawn from a point on the river. From that intersection to the Votive Spring in Roman paces is, he says, a lily, a cabbage, and an apple added together. You follow the meaning?"

"Alas, dear Master, I follow neither his meaning nor yours."

"For the first time in our studies," replied Vaini, "I am disappointed in you. The most superficial observer of Nature knows that plants, flowers and fruits are constructively formed upon numbers. Thus the botanical key of a lily is 6; in most grasses it is 3; in apples, pears and roses, 5; while all cruciferous vegetables, such as turnips and cabbages, are formed on the ground plan of 2's and 4's. Hence the lily, the cabbage and the apple of Arens give the Roman numerals VI., IV., V., which added together make fifteen Roman paces; and this distance agrees with a point at which a line drawn from the river crosses a prolongation of the western city wall half way up the slope of Lansdowne Hill."

"To me, Professor, it all sounds like unravelling the crimson heart of a rose, or like polishing running water."

"Water!" eagerly echoed the wise man: "how many philosophers have caught golden fish in that same water! Think how often Science has kindled its flame at an alchemist's sparkling vision. But enough... success means a wreath of immortal renown."

"It may mean a bullet through the brain," I added.

"What matter that we stumble, if we climb!" retorted my tutor, with a cheerful nod. "Would you not rather pace the deck than be a stowaway? Yours," he added, softening his Italian utterance to a whisper—"shall be the condensed cream of this adventure. You shall have a summerful of love. You have asked more than once why I sought your co-operation. Your part shall be to excite a sentimental interest in the brown girl, and lure her from the compass of my operations. I must have time and elbow-room."

"Shy as I am, and maladroit with the sex...."

"It is only a bad workman," he interrupted, "that finds fault with his tools. You have long been on easy terms with the deeper emotions, and now you will attack at once, remembering that in life, as in chess, the prize is with him who seizes and keeps the move. Do not let your initiative lack powder: strike once—through the heart. Above all, watch the under-current of this dangerous girl's thoughts, for hereupon, very possibly, your life will depend."

"Professor," I asked, "what am I to get for all this?"

"Friend of my soul, you shall have the sprig of bay that Ladas died to reach!"

"Maestro," I murmured, after a pause, "would it displease you if I took the next train back to London?"

Vaini's face clouded at the words. "I should not have supposed it possible," he answered, in a voice of pained surprise, "that my favourite pupil could thus chagrin me twice within an hour. How can you tremble thus before fly-blown fears, when a fixed belief in oneself may touch even mediocrity like yours with that spark which to this day fires the intellectual Tenth Legion—the indomitable few?"

Accustomed as Vaini was to win men and bend them to his purpose, he would not believe that his pupil might not sway this wild girl's will. He declared that, schooled as I had been by him to scientific illusion, and habituated to calculations as subtle as the witchery that breaks or mends a human heart, I would have over Pandora the same advantage intellectually that a chess-player would possess who employed an original opening of superior force. He urged me to look at the situation historically, analysing the mainspring of accomplished fact and putting wholly away that muttering in our sleep we call philosophy.

"In my own experience," he added, gazing retrospectively out of the open window, "I have made it a point on occasions such as this to grasp the thrill of conscious strength which illumines the drama of life. It is the Italian manner, and results in action as pure and fine as the draped figure of romantic Music. The apples of knowledge are sour, yet I require of you but a single warm-hearted moment, believing as I do that anything can be done in a world where crooked grows faster than straight."

IN the days that followed I never saw Pandora Miduvel without

speculating upon the attributes our fancy had lent her, and

asking myself whether an impress of some remote century might

linger in the mind, as the murmur of long-silent waves clings to

the ocean shell. Could it be that ripples set in motion by the

Ark still send a tremulous impulse across the expanse of things

we muse upon? May the consciousness be so supernaturally

quickened that a transmitted whisper is distinguishable across

the soundless dark of ages?

Once—fallen thus into sun-dreams—I loitered an hour amid the crystal roses, listening to the immortal talking of the river as the moving vision of its fluid panorama splashed and eddied over the water-worn stones.

"I divine your thought," cried Pandora, coming towards me with a smile of magnetic fascination. "You are thinking that the babble of a stream is a changeless voice, speaking for ever with the same meaning." Then absently she added, "When I listen, a fancy brings before me that which I have never seen—a place of breaking waves."

"And have you always lived," I inquired, "in this old-world atmosphere of peace called Bath?"

"Yes, since my uncle died, five years come Twelfth Night. In his prime he was the best wormeater in England."

"Wormeater!...." I repeated.

"One that bores worm-marks in new-made furniture to sell for old. It is an artist's trade—though he loved life as well as art. Look," she continued, leading me to the dining-room, where, on the reverse of a framed cardboard, ornamented with the familiar invocation of a "blessing on our home," the departed wormeater had traced the legend:

IRISH WHISKEY, ENGLISH BEEF,

A WELSH RABBIT AND A SCOTCH GIRL.

"My aunt is not Scotch," added the dark maiden, with ripples of mirth.

AT the end of a week Vaini and I had sufficiently reconnoitred

our ground, and the next night was appointed when we should sink

the treasure-shaft of his invention. Once at the locality on

Lansdowne hillside which he identified with the vanished Spring,

I had watched him drawing a web of lines and curves and dotted

figures so carefully based upon the sun's rays, as to be

evidently an astronomical calculation. We were to take our valets

with us and station them out of sight of our operations, yet near

enough to protect us against surprise. Vaini was unarmed, but I

carried a pocket five-chambered Colt, throwing an eight-ounce

ball thirty paces.

As the night was to be one of fatigue, I resolved to spend the morning strolling at the edge of a forest called Withering Leaves, where in those days grew handfuls of wild flowers. In the early hours, gazing from my window upon the vaporous cloud of pink and yellow blossoms that made the day seem cut in pearl, I had heard Pandora singing with marvellous finesse a popular refrain, a song of rare pathos, and sweet as the melody of waking birds,—and now, as the sunshine broadened, what could I do save let my thoughts drift with the song? As I walked it seemed to me the world was filled with such faint sounds as minstrelsy is made of. Once, across the luminous green, a cloud-shadow flitted, as though some boding presence, cleaving the sunlight, sped upon vanishing wings. I had readied the crest, and turned to look across grey manor garths upon the Avon, gliding down its smooth pavement towards the city's stair of climbing roofs, when amid the tufts of meadowsweet and feather hyacinths I observed three twigs laid together in a triangle.

I was scrutinising this familiar gipsy signal, when the sound of voices hurtling through the forest reached me—the shrill defiance of a woman, the angry scolding of a man. Before I could catch more than a few words they issued from the trees.

"I speak for our people; my word is the voice of all," cried the man.

"Hideling," answered the girl, "speak again and I will leave my mark on you broad and deep!"

Then, at sight of me, both were silent. The woman was Pandora Miduvel, and from his face of bronze I took the man to be an English gipsy. He was roughly habited in what his vernacular would have styled "Kersemere kickseys" or breeches, a waistcoat of faded tomato red, a rusty velveteen jacket and cap, and about his neck a "blue billy" kerchief—an ornament in vogue amongst those who devote their leisure to the technique of the poacher's art. In appearance he was a bulldog of the human breed, and I divined that he was one of the Celestial's underlings. He glanced doubtfully towards her, while she stood intently watching me, with lips pursed in a silent whistle. Was she considering whether to set her bulldog upon me? If so, the thought passed, for, motioning him back, she advanced with a salutation of suppressed amusement. She walked as light of foot as a fawn, and carried her sun-browned head like a flower. In her face was the exuberance of country life, and in place of the sweet-apple bloom of an English girl her dusky skin glowed with the fire of Egypt. About her hung a fascination not of the visible world, an impression heightened by the gold coin which dangled and sparkled beside her face. As she approached she laughed with semblance of good-humour, yet that little laugh sounded weird as a song-thrush singing in December.

"I wonder at finding you followed by so unsavoury a companion," I said.

"Only buying mushrooms," she answered, showing me a basketful of creamy fungi.

"Perhaps you will tell me, as before, that you were waiting for me and calling my name?"

"I was telling my cousin Kushto Macromengro I will not marry him. When the same thing has been asked and refused a dozen times, what wonder if the voice be raised?"

"Very true. I might have known that those harsh cries could be none other than the accents of a love fed upon bitter herbs. Poor Kushto, he already tastes his cup filled with the lees of other men's revelling."

"Other men's revelling!" she repeated: "that means another man's love." And as we walked she paused with wistful face, wherein some amorous thought gathered, as may hover a fancy of incomparable music about the silent harp, that waits—its strings unsmitten.

"Do you think you would ever grow to care for me?" she asked, with the heedless curiosity of a child.

The oddity of her question recalled the Hebrew declaration, Man loveth the woman that is a stranger—a judgment so true that, possessed as I was by a gruesome dread of my new acquaintance, I nevertheless felt within me the power of her charm.

"I have but to look in your face," I answered, "to know that you would prefer me to a hideaway poacher. Something tells me you have a purpose in life—dangerous it may be—who can say!"

"How do you know that?" she asked, with fixed attention.

"I have seen heads like yours on canvas," I replied, "wherein lay a passionate romance with interwoven ambitions and jealousies. Heads of famous people, whereon is the haunted look of unspeakable memories, whose thought is trained to scrutiny of every hour, not knowing what danger the next may bring."

But she scarcely listened, and interrupted me, saying: "Why were you following me, and how did you know I was here?"

"I was looking," I answered, amused at this characteristic inquiry, "for something else than a lovers' quarrel. My companion seeks a spot on the hillside where in ancient days, when people very different from us lived here, a young girl like you was put to death. There were splendid Roman soldiers in those days, as beautiful as the archer-gods of open air. You may still see them, I am told, on moonlight nights, mere shadows in the hedgerows now, and catch the faint command, the bugle echo, the tread of muffled feet; till when they pass the place we seek they turn to jeer upon the girl I spoke of—stripped, whipped, crucified... naked and ashamed."

"Why was she stripped and whipped?" asked Pandora.

"Because, though her lips breathed love, her heart was filled with hate. But here we are at Castle Joyous. Come, let us drink a glass of wine together and speak no more of such sad things."

A moment later, we stood in the garden, with a bottle of my Espiritu Santo on the rustic table. "Taste with me," I said: "it is the wine of gold distilled from yellow ingots and double ducats—the enkindling wine that treasure-seekers drink."

Raising her glass, Pandora, with a twitch of the wrist, spilled a few drops, in this quaint usage of modern country folk unconsciously offering a libation to Olympus. Then she tossed the wine off—not in sips, as well-bred women wet their lips, but at a voluptuous swallow.

A FEW hours later, soon after finishing our midday meal, Professor Vaini became violently ill. When he had been put to bed by his servant, Pandora was unremitting in her inquiries and offers of service. He would have no doctor, being himself an accomplished herbalist, and wrote his own prescription for an antidote. Reflecting upon our simple diet that day, which Mrs. Oldcorn had prepared, I could think of nothing doubtful except the mushrooms Pandora had obtained from Kushto Macromengro. I had not tasted these, and fortunately Vaini had eaten of them sparingly. Upon mentioning to him the hands through which they had passed, he nodded and said, "The touch of those brown hands changed them to toadstools."

The next morning he was better, and I left him in charge of his valet, after shocking Mrs. Oldcorn by telling her of our suspicions. I resolved to seek Kushto Macromengro, and picture to him some of the disagreeable possibilities of life. I had not spent one summer fishing with gipsy guides without learning their ways; and now, in observing at the fringe of the forest a tree marked XX, I knew it for a token of twisted-tail cipher, and doubted not the poacher was near—possibly watching me. I pursued my walk listening intently. It was a theory with Vaini that cultivation of the senses refines the mental perception; and by way of sharpening my wits during our residence together in Italy, he had so exercised my hearing, that now across the stillness of Withering Leaves I could perceive the barking of dogs upon the far horizon and hear the tinkle of Bristol church-bells nine miles distant, could catch above me the murmur of unfledged rooks talking in their sleep, and on the Broadwater road, a mile away, distinguish a man's measured tread, a woman's lighter step, and a child's pitapat following after. I soon became conscious of a stealthy footfall, and knew that Pandora's bulldog was at my heels.

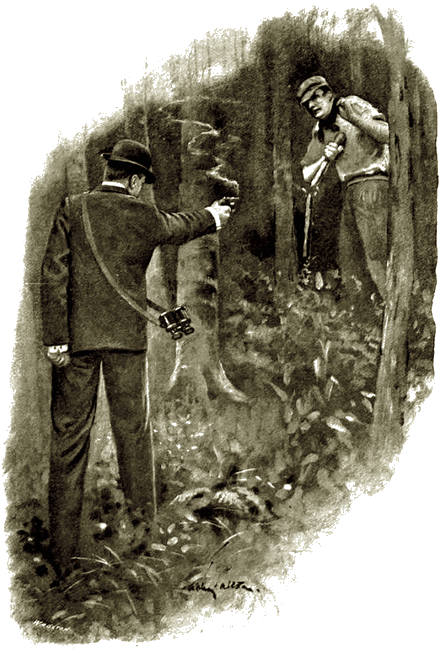

Crossing an open glade, I paused at its fringe, and raising a small field-glass which hung at my side, looked over the country. Everyone knows that by holding a field-glass reversed, with the large lens an inch from the eye, and looking not through but upon it, a minute and powerful reflector is obtained. I stood thus a minute, seemingly absorbed in the landscape. Suddenly in the glass I beheld Kushto peeping from the bushes twenty yards behind me. A single instant he stood, gathering himself together, then dashed forward, his short stick ready.

Letting fall the glass, I drew the five-shooter from my pocket and faced about. In those days I was quick as a whip-lash with a revolver, and as the gipsy came on, I fired two shots in instant succession, with the first slicing away the lobe of his right ear, with the second splitting the cudgel in his hand.

As the gipsy came on, I fired two shots in instant

succession...

with the second splitting the cudgel in his hand.

"Now open your mouth," I said, as he halted, "and you shall have the other three down your throat."

The ancients deemed the danger and despair of a fighting man the supreme poetic morsel, and might have given a moment to gaze at even the roughest human animal at bay. Kushto stood confronting me, laughing with bravado at what he took to be my poor shooting.

"Fairly takes the cake, sir," he said, producing a cotton handkerchief which he held to his ear. "Lucky for me you are such a bad shot!"

"Mr. Macromengro," I said, "you are coming with me to the Police, where you will answer to a charge of conspiracy to poison, and of attempting a murderous attack."

He stood irresolute, deliberating whether to take the chances of a rush upon me, or to make terms. He chose the latter alternative, and instantly appealed to me to let him go upon easy conditions. "They be so rough at the Pollis," he added, with a grin, "and in all my life I have never been struck with a whip, never been sorry or sick."

"I wish you to answer a few questions," I said. "If I get the truth, you may run for the woods. First, who is Pandora Miduvel?"

"Perhaps one of us; maybe an orphan; says she knows neither father nor mother."

"Where did she come from?"

"Swam ashore. Like all young gentlemen, you think the Rahnee's taken a fancy your way, but she's not: in the end she'll marry me."

"She would marry you if I and my Italian friend were done for?"

"You don't want me to peach on the kid, sir: ask yourself if that would be fair. But she hates the seedy swell that's with you, and she'll wear widow's weeds for no one but me."

"Where did you gather the toadstools she got from you yesterday?"

His mouth quivered, and he stood watching me nervously.

"She has refused to marry you unless, if a good chance offered, such as this just now, you knocked me on the head."

He cast his eyes down and began drawing circles in the dust with the point of his foot.

"Silence pleads guilty. You have given me as good answers as I expected, and now you may go. But the next time we meet in this wood I shall take better aim, and my word for it .... I'll marry Pandora Miduvel."

MIDDAY drew near when I returned to Castle Joyous, to find

Vaini better, Pandora at his bedside reading aloud, and Mrs.

Oldcorn bringing up a tray furnished with an invalid's repast,

"old man's diet" she called it, which I recognised as a goulash

of minced beef, with stewed potatoes and onions, and scraps of

buttered pork. I persuaded him to drink a little mulled wine,

which I heated and spiced myself.

As the hours wore on, I strolled into the garden, meditating my project of a surprise for Vaini—which was to go that night, attended by his servant and mine, to Lansdowne Hill and sink the treasure-drill at the point he had marked with a white pebble. If beneath all this speculation there rested a golden corner-stone, I meant to reach it.

It was a tranquil day, one of the rare and splendid days that are remembered when in the brooding silence of October we walk amid the summer's wreckage. It is then we recall the baby leaves unfolding, the perfect boughs uplifted, the long afternoons—soundless, save for redstart chirpings. Such days, and our loves, will seem, at the end, the only things worth cherishing.

To this garden Pandora often came, preening her little plumage, idle and carefree as those proverbial beings that in springtime smile at the winter's frost. In the brilliant sunshine her plain gown seemed spun about with films such as the fairies wear—a witchery of amber light and violet shade. Prom what far bourne had she been severed and brought back into the picture of earthly scenes? At what hidden springs had she tasted the instinct which teaches such strange folk their wisdom? Would she go through life as young as yesterday, yet older than the grey of weather-beaten rocks? I could but feel that to her reasoning Vaini and I were attempting a desecration of the girl-goddess, whose shrine she lived to defend.

There before me, at the end of the rose-walk, where a tiny fountain bubbled into an antique basin which might have seen the hyacinths bloom in Aqua; Sulis, stood Pandora, trellising a vine.

"This garden is like you, Pandora," I said—"sun-kissed and wild."

"The fine gentleman who made it," she answered gravely, "might not thank you. Years ago I heard say he was some wise man, like the seedy swell upstairs. His garden was to be no mere patchwork of walks and borders, but should speak a meaning. In the sunlight he set clusters of brilliant roses, and under this trellis great banks of violets which seek the shade, ... so in the two, placed thus, he read the sunshine and shadow of life... and of love."

"Love!" I whispered: "to think that you should speak that word to ma."

The day was ending, its crimson fading to sapphire in the dark. The Cathedral vesper filled the air, and a lurid sunset, gleaming through the pines, Lathed the yellow elders in luminous sheen. Behind us, great lilac bushes were heaped with tints of Tyrian purple; and listening to the trickling fountain, I knew the hour held its way in music. If ever I were to act upon Vaini's wish and seek to lure the brown girl from his circle, now was the time!

"It is true, then," I said, "that every garden fountain has its nymph, and that I have found her under this evening's sky."

She listened with a look of fixed aversion, and answered, "It is Kushto Macromengro that you found to-day."

"Yes," I assented unconcernedly; "better so than that he found me.... unprepared. So he has been for fresh orders?"

"He has not been here," she replied. "If I know what happens, it is for the same reason that the lightest vapour casts its tell-tale shadow. Shoes marked with the clay of Withering Leaves, and on your table a revolver with two empty chambers Have you killed him?"

"Far worse. I told him I shall marry you."

An angry flush suffused her face, and I could scarce suppress a smile at thus rousing the devil. "I sometimes think," I added, hoping to pique her to an unguarded word, "that you gaze on many shapes I cannot see. It would not surprise me that you behold the forgotten things of my life, or that you should tell me they are best worth my remembering. Now, if it be true that fate lies in the hollow of a hand, put both your hands in mine and I will tell you what dwells in the mind of the gods—and of a woman."

"Now, if it be true that fate lies in the hollow

of a hand, put both your hands in mine."

"Nay, tell it to yourself," she answered—"you that spend a summer blowing upon dead coals. You are not the first that has been here measuring and digging and setting odd marks in the ground." Then, with sudden exaltation, she added, "If you would know where springs the oozing from the earth so many have sought, come with me the first dark night, and I will show you that treasure of your life you grope after alone in vain!" Beneath the sunset her eyes were deep as her ominous words. I remembered with a shudder how Ormès and Almodoro were taken to find the treasure of their lives and left for dead. But after a moment's seeming reflection, I answered, "To-night I dare not leave my friend, but to-morrow night at eleven you and I will meet where we now stand, and we will wander away so far together that all the rest of life may not suffice to bring us back."

THAT same night, when eleven struck, Vaini was asleep, Mrs.

Oldcorn and Pandora had retired to their rooms; and carrying my

shoes in one hand and the treasure-drill in the other, I went

softly downstairs in my slippers. The two valets awaited me, and

we were soon well on our way to Lansdowne Hill. I laughed aloud

to think I had stolen a march upon the girl-goddess. Bathonians

keep early hours, and we met no one, nor were lights visible in

the houses. Once only, in the distance, a gleam flashed, as

though an eye opened upon the horizon. There was no sound, save

the thin whisper of the night. A mile away spread the black shape

of Withering Leaves, and overhead were the stars and rising

crescent the Flamens and sentinels of Aquae Sulis knew.

I had resolved to remain the shortest possible time exposed to accident, and my dispositions were instantly made. I stationed one of the men at the roadside, and the second forty yards in the other direction, facing the only house in that neighbourhood. They were to stand with their backs to me, to be keenly on the alert, and to give warning of the approach of man or woman. After his discomfiture of the morning, I did not anticipate that Kushto Macromengro would be very enterprising, and with Pandora Miduvel asleep, there seemed small likelihood of interruption.

I had thoroughly tested Vaini's invention beforehand. At each fifteen inches insertion into the ground, it was to be withdrawn, and emptied of the handfuls of earth thus extracted. I fell to work vigorously, plunging the tube into the gravel by means of its revolving handle, emptying it and beginning anew. My excitement may be conceived, when at a depth of five feet I felt its drill grinding against a hard substance. Upon carefully withdrawing it and running the earth through my fingers I found three coins, at the cold touch of which I could have shouted for joy—for the secret so long and tragically guarded was revealed, and the Celestial Virgin's treasure was ours! I pocketed them, strapped the treasure-drill over my shoulder and was refilling the opening I had made with loose earth at my feet, when my servant came running back from the roadside in a tremble.

I drew my revolver, and we stood side by side. He was too frightened to mutter more than that something had run noiselessly past him, flickering in the starlight. I advanced a few steps, peering into the darkness; but although the moon was rising, discovered no more than that the velvet-footed mist gathered its phantom shadows.

Suddenly from behind came a cry, and the sound of a falling body. We hastened back to Vaini's servant, whom we lifted half unconscious, his face streaming with blood. Between us, we helped him to the roadside, where I gave both men some brandy from my flask. Not more than twenty minutes had elapsed since we came—yet to me it seemed longer than the night. As soon as the injured man had bound up his wound with my handkerchief, and could walk, we made our retreat down the hill. He was obliged to halt several times to stanch the flow of blood, and in one of these intervals told me with some difficulty—for his hurt had included the breaking of his front teeth—that he had seen nothing, but that from the darkness a stone, the size of a man's fist, had been hurled with the force of a catapult, and had felled him to the ground.

I was in a state of nervous tension when, unlocking the front door of Castle Joyous with a passkey, I perceived from the lights and tread of feet that something unusual to the repose of the house had happened. Not till afterwards did I learn that an alarming noise had awakened the maids who slept above Pandora, and that Vaini and Mrs. Oldcorn in their rooms were startled by the frantic cries of one struggling with a nightmare... "Keep him away—drive him back—don't let him dig in the ground!"

Now she had issued forth to the head of the stair I was ascending, and I beheld her, a silvery figure in the half-light, gazing upon me with the tumult of a meteoric passion. For a breathless instant it seemed that, through her disarray, I beheld Pandora transfigured to a being statuesque and heroic, whose shrine I had profaned. The moonlight became clearer, and I paused motionless, listening to the harping of the breeze. In that weird instant I knew that an unknown presence had come with the virgin feet of the day, motioning me back from the precincts of a vanished world.

I beheld her, a silvery figure in the half-light,

gazing upon me with the tumult of a meteoric passion.

Then the supernatural faded, and the human Pandora fell upon a chair and burst into a paroxysm of tears.

AT an early hour on the following morning I made a full report to Vaini, still resting on what had been his bed of pain, and placed in his eager hands the three coins that had come to light. Two are gold, one bearing the effigy of the deified Julius Caesar, perhaps struck in the first year of Octavian, the second showing a head of Agrippina. The third, when freed of dirt and polished, proved to be a piece of great rarity, imprint with artistic grace—a silver Tetradrachm of Metapontum.

At midday I was sitting in the little parlour adjoining the dining-room, when, to my astonishment, Pandora entered with outstretched hands and a radiant smile revealing a flash of white teeth.

"Forgive me," she said, "my mannerless folly last night. It was a bad dream that drugged me, and you, who have the habit of sun-dreams, will bear with mine!"

I observed intently this play of oddity and emotion, remembering my tutor's caution that life might depend upon detecting the undercurrent of this strange creature's thought. Was it her nature to pass thus from day to night, from night to day, without either dawn or twilight? Stamped upon her face, beyond all weeping and wailing, was indeed the footprint of a violent grief. The bloom of her youthful beauty had faded in an hour, as a woman's face changes amid sudden sorrow and anxiety. Behind this outburst of good-will was that composed self-mastery with which the great felines regard an imminent danger. In her eyes lay the mystery of a cloud-covered sea. Was it that I but saw in them my own reflected misgiving, or did I discern behind their lustre a cold and deathless hate?

I took her hands and playfully caressed them.

"We will leave our dreams," I said, with half-conscious irony: "you your nightmare and I my wasted reveries. Some day let us seek together a beautiful far country where the only dream will be that Love is for ever."

As she listened, her eyes were raised towards the leaded window-panes glinting in the summer sunlight, and I saw that they were moistened with tears, and marvelled that my careless word had struck so deep. She left me abruptly, and presently I heard her singing in the adjoining dining-room. I heard, too, the uncorking of a bottle—a sound that excited my curiosity, for Pandora never deigned concern herself with household matters. Then her step traversed the hall, and I went into the dining-room to find that, of three or four bottles standing on the dresser, she had drawn the cork of one and placed it invitingly on the table at my chair. The luncheon hour drew near, and before my plate was a dish of yesterday's capon, a favourite refreshment with Mrs. Oldcorn, the broken meat being stripped from the bone and with fragments of a neat's tongue, buried in brown jelly. It was flanked by a plate of dandelion salad with its red splash of tomato. The Professor's luncheon was to be served him in bed. I felt a strong repugnance to drinking the wine Pandora had made ready. There are nervous instants when we yield to the weakness of thinking that to do a certain thing will be unlucky, and to such an impulse I yielded in replacing that bottle, recorked, on the sideboard.

In the act of doing so I heard the muffled footstep of a man in my bedroom overhead. My servant had gone into town, and I opened the hall door slightly and waited. Noiselessly down the stair came a furtive tread, till, stepping forth, I confronted Kushto Macromengro. Without evincing surprise at his presence, I drew him into the dining-room, and said it had been my intention to visit Withering Leaves again some day to show I bore no grudge. I inquired after his damaged ear, and reminding him that the following day was Sunday, declared I would give him five shillings to buy beer and tobacco. Affecting to find no money in my pockets, I vowed with a chuckle he should taste sherry from my private stock, and placed in his hands the bottle of Pandora's choice.

"You shall drink deep as brandy-Nan!" I said, slapping him on the shoulder; "but meanwhile hide this wine in some capacious pocket and make for the woods by the garden gate."

It struck me the rascal was in haste to be gone, as, with merely a nod, he strode past and was out of sight.

I immediately went to my room, and there made a discovery which caused me an emotion. On the floor, resting against the wooden partition which divided Vaini's room from mine, and against which stood his bed, was a box filled with gunpowder and bullets. A lighted fuse trailed on the floor, of such length that an hour must have elapsed—the hour when I would have been regaling myself with yesterday's capon and sherry—before the explosion. My companion, in his bed, would have been riddled with bullets, or, as Almodoro phrased it of Ormès, "smitten with the club of Hercules." I summoned Vaini to come and see for himself to what his scheming led. For once he betrayed strong excitement, and I heard his quivering lips mutter, "Razza di Cane!"

I seized the moment to inform him that, in view of the gravity our adventure had assumed, it must cease at once, adding my intention to take that evening's train for London, and that our mutual safety required that he also relinquish the search and come with me. My reasons for letting fall again that thick veil our efforts had so nearly lifted were expressed with no little pungency, and I summed them in a favourite dictum of my former fellow-student Mr. Orion Marblehead:

"It is not safe to spend too much time monkeying with Hell."

My instructor in the curious arts yielded with a bad grace, and, still trembling to his knees, gave way before his inability to proceed alone. In the course of that evening's journey he assured me seventeen times that the miscarriage of his hopes was wholly due to my maladroitness, and repeatedly declared that in failing to entice Pandora's affections, I had missed the opportunity of my life.

"Only to think," he ejaculated, "that I was on the point of scaling the unclimbable mountains!... And now what have I to show except a set of false teeth for Pasquale?" Once or twice before, in other matters, he had Censured my imperfect range of vision when scanning the perspective of bygone centuries; but now, for the only time in our long acquaintance, he displayed an extreme irritability, and for nearly a year our friendly relations suffered a chill.

Having extinguished the fuse, I rushed downstairs in pursuit of Pandora, but, needless to say, she was not to be found. Mrs. Oldcorn returned from the girl's room declaring that she had taken her bonnet and shawl and gone over the bend of the world, adding that young women now-a-days are "not good for any think," and that this particular specimen was "only black rubbage."

"But she is your niece," I cried, a new light breaking.

The hasty explanation was made that Pandora Miduvel was nowise her relative, but a waif rescued and educated by the late wormeater, for reasons best known to himself.

IN London a week later I received a letter from Mrs. Oldcorn,

saying that Pandora had returned to her wild life. Doubtless the

dark beauty had merely withdrawn to another coign of vantage. She

added that in a glen at withering leaves where Kushto had a

shelter, his body had been found before the ashes of a camp-fire,

over which still hung a kettle containing a bit of bacon and a

couple of duck's eggs. He had lain thus for several days, bent

backward in the distortion of strychnine poisoning, and near him

rested an empty bottle labelled Espiritu Santa.

TEN years later, in May 1885, passing a month in London, I was

invited by a medical acquaintance to visit with him Bethlehem

Hospital, popularly called Bedlam, where was his professional

service. At the end of an hour's inspection of various wards,

each having its grade of insanity, we passed into a garden,

within high walls, where in pleasant weather the more tractable

madcaps were allowed to walk. It being their dinner-hour, the

place was deserted, save by a little old swarthy woman, who

turned her wrinkled visage and passionate eyes towards me in a

careless glance.

My guide, noticing the intentness with which I observed her, murmured, "One of our oddest patients: I know not her name, nor her story, nor whence she comes. She speaks of herself as Pandy, and is usually quiet, as you see her. Only at intervals, once in two or three months, she bursts into a paroxysm of tremendous fury. We always know when to prepare for these fits. An hour before the spasm, she begins a hoarse muttering, ever more rapid, and ending in demoniac yells: '... Keep him away... Drive him back... Don't let him dig in the ground!'"

IN 1900 I returned, weather-beaten and frost-crumbled, to

Bath, to drink its waters. I go there now each November, and

often pass the places Vaini and I knew together. Castle Joyous

has disappeared, and amid new furrows and turnip fields I can

only conjecture the forest fringe which Kushto Macromengro

frequented.

The drifted leaves lie heaped above that buried Summer, and to my eyes the familiar poplars cast a longer and sadder shade. The walk through Withering Leaves still keeps its fragrant charm, and in the turquoise dusk of distance the hills gleam with poetic beauty. I look upon the Avon and listen to its song of myriad meaning, and beneath its calm behold the prism wherein my youthful gaze divined such marvels. Upon its surface at night I see the Milky Way reflected and know that this starlight tracery upon the water is the Celestial Virgin's dustless path.

In the hush of these my twilight days I remember Pandora, and think how our brief meeting burnt a mark in my life. Whence came this fierce girl who "swam ashore" and whose prescience demolished our endeavour? Was the legend of the goddess of Aqua: Suits known to her, and was she filled with the fire of a powerful purpose which, when accomplished, left her life empty? Was no frail germ of feminine tenderness enfolded within the harsh discords whereby alone I knew her? How fantastic in the retrospect is this ill-omened example of Vaini's art—the gate of another world half-opened, our goal no further than Yesterday from To-morrow. Within, we see the crystal roses and hear the rippling river, with its whisper whereof music is made. We gaze upon Aqua; Sulis, and hear the deathless bugles of a Roman Legion. Above their faint reverberation rises an ever-deepening note of tragedy. Then, as though the Fates played with loaded dice, the maiden-dawn changes to flame. And, remembering these things, I linger before the insoluble question—within the folds and windings of that Shadow-land we ponder, may it be that the survival of some bygone age still whispers the living Present?

Occasionally my field-path rambles lead across Lansdowne Hill. I pause to look upon the spot where in the stillness of a summer midnight I sank Vaini's treasure drill into the ground. The antique coins then recovered are before me, witnesses to the accuracy with which he calculated the position of the ton of gold there buried. But I never feel the wish to probe for it again. Better than any one now living I understand that in defence of her own the Celestial Virgin is a tigress at bay. I have no desire to evoke afresh that demon of tears and hate. For well I know that at the slightest menace a spectral arm would be outstretched as before. At the first step I should recoil before the consciousness of an arresting presence, sprung suddenly into being behind me, and turning, should behold again a tawny girl of rare beauty regarding me in silent menace with the sweet and implacable smile I remember.

— William Waldorf Astor.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.