RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

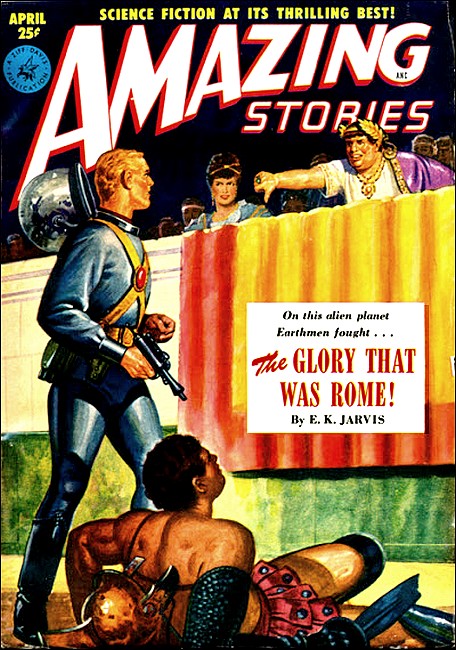

Amazing Stories, April 1951, with "Let's Give Away Mars!"

Headpiece from Amazing Stories, April 1951

Don't worry about the men from Mars. We've

already conquered

them—and with something far worse

than the atom bomb!

ABOUT months after I'd become the end name on the firm of Beaton, Batten, Burton & O'Leary, advertising counselors, we landed the Spy Soap account.

At first, we thought we had the world by the tail and the strength to swing it. Fifteen percent—the customary agency fee—of the Spy advertising appropriation each year alone was enough to keep even larger agencies knee-deep in paneled offices and shapely secretaries.

And then we personally met Jeremiah Spy, the Soap King, who believed in his product with all the frenzied zeal of a missionary selling Heaven and buckram-bound Bibles....

He sat behind his battered roll-top desk, a thin cadaverous man with a habitual expression of morose dignity on his face. There were no pleasant preliminaries as we came into the dingy cubbyhole he used as his office, no highballs in crystal glasses, no dollar cigars handed around.

"Gentlemen," he snarled, "I'm interested in selling soap. Other men may be interested in sex or food or shooting eighteen holes of golf in the low seventies. But I have no such distractions in my life. I want people to buy my soap—and it's up to you to plan a campaign that will sell it. Let me hear how you're going to do it."

We had three suggestions to make then and there. He rejected every one of them.

Back in our own office, the four of us had a conference. We tossed Ideas around fruitlessly for the better part of an hour. And then this thing hit me in one dazzling flash of pure genius!

"I got it!" I bellowed. "The perfect gimmick!"

"Glory to God!" Johnny Beaton cried. "I knew we could count on you, Mike!"

Oscar Burton, the practical member of the firm, looked at me doubtfully. "Tell us about it, Mr. O'Leary."

"A give-away show," I said—and cut off their groans by raising both hands. "Listen: I know give-away shows are old stuff now. But why? It's because the sponsors ran out of ideas on what to give away."

"And you got something new to give away?" Burton asked skeptically.

"Right! I suggest a show which, as the main prizes, will give the lucky winners an all-expense trip to Mars!"

The silence that followed was deep and unflattering. The three partners looked at one another, then pointedly raised their eyes toward the ceiling.

"What's wrong with you?" I yelled.

"Don't you get it? Of course we won't send people to the planet Mars, you literal-minded asses. We'll find a little town somewhere in, say, Colorado, or Wyoming, to go along with our gag and change its name to Mars. But first we'll whip up bales of publicity and get everybody guessing on what we're going to do."

The plan was shaping up beautifully even while I was talking. "For the payoff," I went on, "we'll have a phony space ship set up at Mitchell Field and load in the winners with a grand flourish. Then we'll fire off a bunch of rockets, lay down a smoke screen, take the winners off the space ship, put them on a plane and fly them to Mars, Wyoming, where they'll be the guests of Spy Soap for two thrill-packed weeks!"

By this time It was beginning to get across to the others.

"Hey, I like it!" Johnny cried. "The columns will love a gag like that."

"Let's see Spy," Oscar said.

Jeremiah Spy heard our idea with his usual expression of bitter displeasure. But when I finished, he said, "I won't go so far as to say I like it but it's worth trying. Get on with it."

THEN there was the business of getting a dummy space ship. I

knew what I wanted, of course. Something like the standard-brand

of science-fiction ship, with shining hull, flaring fins and so

forth.

I remembered a professor I'd known in college who was hipped on interplanetary communication. His name was Hinesmuller, and his accent was so thick that I don't believe anyone had fully understood him since he left his native Austria thirty years before.

I looked him up and made a date to see him that same night. The rest of the day I spent with officials at Mitchell Field. They weren't too happy about the project at first, until someone suggested they could charge admission to people who wanted to inspect the space ship. After that the atmosphere became good-humored and cooperative.

At seven-thirty that night, I knocked on the professor's door, which was at the top of three rickety flights of stairs in a neighborhood crawling with brats, vegetable carts and sidewalk artists.

The door opened and there the professor was, hardly changed at all in the six years since I'd last seen him. "Come in, come in," he said heartily, and led me into a cluttered study and sitting room. He brought out a bottle of schnapps, offered me pipe tobacco and then beamed down at me like a jolly, Christmas card figure. His hair was totally white now, but as abundant as ever; his eyes, behind thick bifocals, still merry and youthful.

"Vass iss oop?" he said, cocking his head.

"What?"

"Vass iss oop?" he repeated, chuckling. He slapped my knee triumphantly. "Iss slang!"

"Oh." I got it then. Vass iss oop? equalled "what's up?" after undergoing the scrambling action of the professor's dialect.

"Just this," I said, speaking very distinctly. "I want you to build me a space ship. Do you understand?"

He chuckled. "Yah!"

"Can you do it?"

"Yah!"

"Now here's the point: this ship will be a dummy. Do you understand? Dummy."

He looked injured. "Vy you call names, eh?"

"No, you're not a dummy. But the space ship is. Now how much money will you need?"

That got him excited. "You got money? Money for space ship?"

"Yes. How much will you need?"

"I 'ave been already vorking on space ship. But I must 'ave five t'ousand more dollars."

We settled that detail, and I told him where the ship was to be constructed. Then I said goodby. Down in the street I paused, vaguely troubled. I had the feeling that the professor hadn't quite got the pitch. He seemed to think he was a building a real space ship.

I laughed then, because that idea was so ridiculous, and walked on to my car....

AFTER that we whipped the show into shape, and the publicity

built up with the force of a tidal wave. Everyone began talking

about the all-expense trip to Mars!

Reactions were mixed and violent. Crowds flocked out to Mitchell Field to look at the ship. Senators talked about it in Washington, and one waggish solon made the point that Mars would want a loan from the United States if we ever did reach there. Spy Soap got the benefit of the discussion.

Meanwhile I found a one-horse town in Oklahoma that was willing to go along with the gag. They agreed to change the name of their hamlet from Broken Elbow to Mars the night our show went on the air.

I took a trip out to the field one afternoon to check on the professor. There was a crowd watching the construction of the ship, standing outside the roped-off enclosure and talking knowingly of ergs, gravity fields and the Heaviside Layer, whatever the hell they were. It all proved how easily people can be fooled in this strange and wondrous land of ours. I showed my special pass to the guard and walked in to find the professor. He was with a couple of earnest young men checking some figures on a chart. They were talking about booster rockets.

I glanced at the ship while the professor rambled on in a jargon made up of equal parts of algebra, physics, and Ellis Island English. He had done beautifully so far, I decided. The hull of the ship was about eighty feet long, a tube of slender shining grace. Curving fins flared dramatically from the tapered nose, and at the rear were graceful blisters which presumably housed the "rockets". It looked mighty realistic resting there in the scaffolding.

The professor came over to me, beaming. "Ve go in a veek. Whoosh!" He puffed his cheeks and emitted air in an explosive blast. "Like dot!"

"Fine," I said...

On the way back to the office, I again had the disquieting feeling that the professor and I were seeing somewhat less than eye-to-eye on this deal. But reason reasserted itself and I smiled. I glanced up at the towering, prosaic buildings above me, and at the reassuring, dull people surging along the sidewalks. Space ships! The idea was really funny...

THE show, as Variety put it, was a boff! Went on at

eight o'clock with twenty-five million people hanging onto every

word, and the entire nation waiting for its phone to ring.

There were three first-prize winners. They were interviewed by the wire services the next morning and told how they felt about going to Mars. It was wonderful.

They arrived at our office the next morning where I met them formally. There was Miss Murdock, a plump graying spinster with a speculative gleam in her eyes; Master Percy Wilkins, an unlikable lad of about fourteen, with horn-rimmed glasses, an Eton collar, and an air of lordly superiority; and Valerie Jones, a slim and pretty red-head.

"Well, well, the lucky winners," I said.

Master Percy regarded me suspiciously. "The adjective 'lucky' is not at all apt."

Miss Murdock simpered. "Do you know anything about the male population of Mars?" she inquired archly.

Valerie Jones said nothing, which was probably just as well. I was already of the opinion that Master Percy was a prize little stinker, and that Miss Murdock was going to be a ghastly bore. I preferred to keep my present good opinion of Valerie, and that would probably be easier if she kept quiet.

However, after escorting them around town that day I wasn't so sure of myself. Valerie said very little; but there was an alertness about her that made me suspicious. She was no dumb little gal going along for the ride. Finally, while Miss Murdock was ogling a waiter and Percy was chattering in a nauseatingly manly fashion with the bartender, I got in a few words with Valerie.

"You seem bored," I said. "Did we miss your favorite spot?"

"No."

"This your first trip to New York?"

"Yes."

"Excited?"

"Clinically, yes."

I squinted at her. "What does that mean?"

She turned to me gravely. "I'm writing a thesis for my masters degree in Sociology. This trip is giving me a fine opportunity to study the neurotic fringes of our society."

"Who are they?" I said blankly.

"You, for one," she said. "You and the rest of your breed in radio, public relations, and so forth. This stunt of yours, for instance. Can you imagine a sane normal person dreaming up a thing like that?"

"You don't like it, eh?" I said, nettled.

"Oh, it will sell soap, I suppose, but in essence it's phony and deplorable."

"Oh, is that so!" I said, which was hardly a stopper.

"Yes, that's so," she said, picking up her gloves. "I'm going back to my room to make some notes. You'll excuse me, I'm sure."

I got up and watched her leave, thinking that it was a pity that such an alluring specimen should have to be inflicted with an intellect. She had a slender, erect figure, and slim handsome legs, and I watched it all until it disappeared through the doorway. Then I sat down and met Miss Murdock's leering gaze. It was quite a shock.

"We're all alone," she said, tittering.

"We'll have to fix that," I said hastily, and waved for the check.

THE next day the prize winners were interviewed on a few radio

spots; and Master Percy, by some chicanery, got himself on the

Arthur Godfrey show. Then the night for the take-off arrived, and

shortly before we left for the field I told the prize winners

where we were actually going, so they could notify their

families. None of them seemed disappointed.

"I regard this," Percy was saying, "as a

golden opportunity to study and alien race."

We drew up to Mitchell Field in a limousine, preceded by a motorcycle escort of police. The newsreels and papers were there waiting for us, along with thousands of curious spectators, A spot-light shone on the space ship. A band played dance music. And Spy Soap banners floated everywhere.

We trudged up the ramp to a door in the hull of the ship and a great roar from the crowd went with us. The professor greeted us warmly, if incoherently, and pulled us inside. He closed the door and twisted a wheel that locked it very tightly. We were led to foam-rubber seats, equipped with head-straps that held our noggins firmly against the backs of the seats.

The professor smiled at all of us then and trotted up the aisle to a forward compartment. A moment later a gentle throbbing made the ship tremble.

The professor appeared and waved to us. "All right, ve go now! Whoosh!" He expelled air between his lips. "Like dot!"

He ducked out of sight again and the noise increased. The palms of my hands were suddenly damp. I had a horrible feeling that all was not right.

"Professor!" I yelled.

The noise grew a hundred-fold, a report sounded like the crack of a mighty rifle, and I was pinned flat against the seat under tremendous pressure. There was a hissing, splitting sound, like a cyclone blowing across a beach, then a feeling of pulsing, driving motion.

The professor appeared again, smiling with drunken ecstasy.

"It vorks, it vorks!" he cried.

I knew then, in that portion of the mind that harbors all ghastly knowledge, that we were heading for Mars—and not Mars, Oklahoma!

"IT was supposed to be a gag!" I yelled for the umpteenth time.

Percy, Miss Murdock and Valerie regarded me with varying expressions of distrust. We had been skimming through space for about ten hours now and tempers were far from jolly.

"I intend to sue," Percy said with exasperating relish. He squared his puny shoulders. "I shan't be able to matriculate with my class because of this so-called gag of yours."

"Well, that's a break for your class," I said sourly.

Miss Murdock poked me in the chest with a bony forefinger. "We thought we were going to Mars, Oklahoma!"

"So did I, for God's sake," I yelled.

The professor came down the aisle beaming good-naturedly, and Percy and Miss Murdock began gabbing their complaints at him in high shrill voices. When they paused for breath, he said: "Don't mention it. Vas glad to do it for you."

"When do we get to Mars?" I asked. The question had a nightmarish sound. I had waited hopefully to wake up; but nothing happened. We continued to speed through the void.

"Soon—maybe eight, ten hours."

"That proves you're crazy," Percy sneered, in his attractive fashion.

"Zo?" The professor peered down at Percy with something less than affection. "Come wit' me, pliz."

He herded us to the rear of the ship where there was an observation platform facing a clear glass window. Through the window there was nothing but blackness.

The professor reached for a lever. "Now vatch!" He depressed the lever, and instantly a streak of light flashed across the window and disappeared.

"It went out!" Percy said.

"No, ze light is still burning. Und ve left it behind us." The professor laughed merrily. "Ve go like hell, eh?" He puffed out his cheeks but I beat him to it this time.

"Whoosh!" I said. "Like dot, eh?"

He looked dejected. "Yah. We go much faster dan light. Dot's vy ve can't see Ert' and the stars behind us. Dere beams can't catch oop mit us."

His good-humor restored, the professor smiled and hurried back to the control room.

Valerie had sat down, crossed her pretty legs, and was making notes.

"You're taking all this pretty calmly," I said.

"I try not to get involved with life," she said. "It's more interesting to study it from a distance, I've found."

"Some day life is going to step up and kick you right in the teeth," I told her, with very little grace. Her aloofness affected me in a curious way. I admired her for it; yet I wanted to see her composure shattered if only for a moment.

"I doubt it," she said, and went on with her notes; and I had the uneasy feeling that she was recording our immediate conversation....

EIGHT hours went by. Then the professor gave us vitamin pills,

and nose clips attached to oxygen cylinders, and a little later

we landed on the planet Mars with the ease of a gull settling on

water. The door was unlocked and opened and we piled outside

eagerly.

Obviously the professor hadn't chosen the garden spot of the planet. The area was rocky, dismal, uninspiring; and a gray murky fog added to the impression of dank gloom.

But the professor was ecstatic. "Ve haf' made it!" he cried.

"Okay, let's get started back," I said, and waved to the forbidding horizon. "Hail and farewell, old red planet. I'll be back when you get interior plumbing."

"Hardly seems right to rush right off," Miss Murdock said. "Maybe there are men—I mean people—here."

"I don't like it," Percy announced flatly; and Mars rose suddenly in my estimation.

"You probably never had it so good," I told him.

"I didn't live on a rock heap," he snapped.

"You probably lived under one." Valerie glanced at me coolly. "What needs do you satisfy by shouting at this child?"

"He's no child," I fumed. "He's an animated section of gangrene."

Our discussion, if that's the word for it, was cut short by a shrill cry from Miss Murdock. She was pointing off to the horizon, her face looking like a vivacious prune.

"Oh, look!" she cried.

Eight or ten round flat objects were skimming toward us through the fog, not twenty feet above the ground. They circled the ship, then settled around us in a tight circle.

Creatures began climbing from the saucer-like conveyances.

"Hey, Mars is inhabited," I yelled, in a flash of deductive genius.

"Oh, I knew dot," the professor said.

The creatures were bandy-legged, plump, and about four feet high. They were salmon-colored, with round hairless heads, and features—while hardly handsome by my standards—that seemed amiable and good-humored. All of them were dressed alike in short skirts and jackets made of some metallic cloth.

They hurried toward us from their little planes, and from their rapidly opening and closing mouths came noises that sounded pretty much like intense static from a crystal set. Stopping about five yards from us, and making sounds like a giant bowl of Wheaties, they bowed from the waist.

One of them stepped forward and bowed until his forehead grazed the ground.

"Crackle, snap, pop!" he seemed to be saying. Then he said something that brought the hairs up on my neck. It was a single word.

"God!"

VALERIE gasped and Miss Murdock sank to her knees and cried

out in a powerful, revival-tent voice: "Glory to be Him! They're

Christians!"

The professor cocked his head as the Martian continued chattering; and gradually the light of understanding broke over his face. He began talking then, slowly, haltingly, and he sounded just like a bowl of cereal. When he finished, all the Martians began clattering along like runaway typewriters, interspersing their remarks with repetitions of that awesome word, God.

Obviously, the professor could communicate with them, and that didn't surprise me as much as it might have. Hell, he couldn't talk English, so it figured he knew some language. It might as well be Martian.

He turned to us, then, and said, "Zey vish us to come and see God."

"God?" I said.

"Zey worship God," he said simply, "Well, that's one thing in common," I said. "Maybe they've got some gin players here, too."

Valerie frowned at my levity. Percy patted her arm and said, "Consider the source, my dear."

Miss Murdock was taking things in stride. She winked at the Martian who had acted as spokesman for the group. The Martian stared at her and let out a stream of crackling sounds, and Miss Murdock blushed, and said, "Naughty! Naughty little man."

I wondered how she knew.

Two of the other Martians began chattering at the professor; he turned to us when they finished. "Zey vant us to come mit dem now." He frowned. "Zey also vant to know vich of us is zick, and vich is going blind, and who is—how you say—cheating on best friend."

"I don't get it," I said blankly.

"Iss strange," the professor said, which struck me as putting it mildly.

Anyway, we climbed into the flat round ships—they were like large saucers—and soon were soaring into the air. I sat next to Miss Murdock, who was trembling with maidenly excitement at the proximity of so many creatures who had a fifty-fifty chance of turning out to be males.

"Remember that milkman," I told her sternly.

"Oh, Mr. O'Leary, you are the one," she said, giggling.

Within half an hour we approached a city that was laid out with about the same skill as a village of blocks built by a seriously retarded child. Minarets, cones and spires popped up unexpectedly, some unconnected with anything, others extending parallel to the ground and serving no purpose I could see but to block traffic. They were of various colors, but deep blues and reds predominated, and in the weak sunlight that filtered through the fog, the city glowed resplendently.

We unloaded in a cleared area between two high red buildings. I quickly got to the professor's side. He seemed to know what was going on. And that was more than could be said for anybody else, including the Martians.

WE were herded amiably along a passageway leading between two

buildings. More Martians had joined us now and the chattering

noise they made was about what you'd expect at a cricket

convention.

The passageway ended before high double doors. I nudged the professor. "What's going on?"

"Iss strange. Our radio—"

"Radio? What's radio got to do with it?"

He sighed and shrugged. "I dun' know."

This enlightening conversation was ended as the great door swung open. We surged into a large hall, with green walls and seats arranged in tiers. The wall at the far end of the hall was blank and on it a white light danced and flickered.

Soon the hall was crowded and the doors swung shut again, cutting off the light. We sat in darkness staring at the flickering light on the far wall....

The pattern of light began to flicker and change, reshaping itself into various herringbone designs.

Then the Martians began chanting in unison, and soon the walls were throbbing with their metallic voices. They paused briefly, and in a great burst of sound, cried: "God!"

They did this three times.

Frankly I had goose-pimples all over by then.

Suddenly a musical fanfare sounded. Then a tremendous voice boomed through the hall. The words were indistinct, but I heard one that sounded like "strike."

The illuminated section of the wall came to life.

Flashing lights raced across its surface and a giant head appeared. The head smiled a good-humored greeting at us, and a hand waved casually.

I felt my mind tug at its moorings.

"God!" cried the Martians in a hysteria of piety.

I clutched onto my seat and decided not to think about anything—not anything!

And for the next half hour we watched an amiable, red-haired man go through his act against an illuminated wall in a Martian temple.

An amiable, red-haired man named Arthur Godfrey!

"HE iss their God, dots all!" The professor said this as if it were no more difficult to grasp than the multiplication tables.

We were alone in a spacious but sparsely furnished room to which we'd been taken after the Godfrey show. Valerie, Miss Murdock, and Percy were across the hall from us in a similar set-up.

I was trying with total lack of success to remain calm.

"So Godfrey's their God, eh?" My voice broke in the middle of the sentence and finished on a squealing high C. "Just like that!" I punched the professor in the chest with my finger. "These are Martians, remember? How does Godfrey's show get here? Is there a Martian network that nobody ever told me about?"

"Iss strange," he said. "Zey hear our radio somehow. And our television."

I had a moment of sympathy for the Martians. "A tough break for them," I said. "So that's how they know about us. Through radio."

"Dot's right. Remember, zey ask us which of us iss zick, and which is going blind, and—"

"They're soap opera addicts," I said.

"Zoap opera?"

The professor could speak Martian, could build space ships, could unravel scientific mysteries without wrinkling his forehead, but his ignorance on some matters was literally cosmic.

I started to explain, but the door opened and I was saved the trouble. Valerie, Miss Murdock and Percy entered, and with them was the little Martian who had met our space ship. His name was something like Krikki-Krik and he greeted the professor warmly. They began chattering to each other like club members meeting unexpectedly in some distant corner of the earth.

I was surprised at how glad I was to see Valerie; but her reaction was hardly similar. She was still icily reserved.

"Why don't you relax a bit?" I asked. "After all, we don't seem to be in any danger, and the chances of getting back to Earth are reasonably good."

"I'm not frightened," she said. "I'm bored."

"Goodness me, I'm not," Miss Murdock said, wriggling her shoulders. "This place is just crawling with men!"

"They're not men; they're Martians," Percy said in his usual nasty manner.

"Dear me, 'what's in a name?' as Shakespeare said," Miss Murdock squealed, and her laugh skittered up the scale suggestively.

Valerie sat down and took out her note book. Uninvited, I sat beside her and studied her clean and classic profile.

"So you're bored, eh?"

"That's right. The novelty value of this absurd trip has worn pretty thin."

"Spoken like a typical sociologist," I said, and I was genuinely angry. "You think you can find out about life in the library stacks, or by reading the agate footnotes of some other cloistered cutie who also never got out and found out what people really thought and cared about. Here you're on the planet Mars, one of the first human beings ever to travel through space, to visit another culture, to fulfill a dream that man has had ever since he first looked at the stars. And you act as if you're stuck in Philadelphia for a summer weekend."

"I didn't ask you to analyze me," she said.

"I'm doing it anyway," I told her grimly. "I think you're afraid of life. That attitude of cool scorn you affect is a transparent defense. You don't know anything about life, but you're secretly afraid you couldn't handle it problems. So you hide from it between the covers of books."

There were spots of angry color in her cheeks. "That's not fair," she said hotly. "You've got no right to call me names, and to—" She stopped abruptly and got to her feet, and I saw that her lips were trembling.

This battle was interrupted by the professor. He came over and touched my arm. "Krikki-Krik vants us to go to hall again."

"Why? What's up?"

"I haf' idea, but iss hard to explain."

"Well, try it nice and slow."

"Ve—all of us—are going on giveaway show." He studied me anxiously. "Iss dot right?"

"It's your story," I said; but my voice was a bit unsteady.

"Veil, dot's dot."

"Wait. What are we going to do on this show?"

"Zat is puzzle me. Ve are going to be, how you say, ze—"

"Yes, go on!"

The professor beamed. "I haf' it. Ve are going to be ze prizes."

THE great hall was once again packed with Martians, but now

they were in the mood of a crowd at a Sunday double-header. We

faced them from a platform with lights beating into our

faces.

My mind was churning—to put it mildly.

Valerie was beside me and for the first time she looked uncertain.

"Do—do you know what's going on?" she asked.

"Yes. We're going to be given away. We're the main prizes on a Martian give-away show."

"Oh, but that's idiotic! I don't want to be given away."

"There seems to be no alternative for you,"

She looked at me in panic. "Are you going to let them?"

I crossed my arms and assumed a lofty expression. "I prefer to view reality from a safe distance. I am a calm spectator on the shores of life's river. Let the stream break and roil! What care I? I'm also a Taoist, you'll notice."

She turned away angrily. "You're mocking me. You're throwing my own words back at me."

"Well you thought they were pretty cute words, remember?"

Krikki-Krik raised his arms then and silence settled over the hall. He led the professor forward and there was a low, seemingly good-natured buzzing from the audience. Percy was led forward and was met with total silence. I was next and got a moderately lively greeting. If volume meant approval, I was leading Percy by a comfortable margin, I glanced at him and sneered.

Miss Murdock got quite a hand. The irritating buzzings and chatterings shot up to a mild roar, but when Valerie came forward the roof fell in. The crowd got to its feet and chattered like a thousand erratic radios. Obviously, they knew a good dish when they saw it.

Valerie shot me an appealing glance.

I shook my hands over my head. "Congratulations, champ," I called out.

"Very funny," she said coldly.

We were taken back to our chambers then and the professor attempted to question Krikki-Krik about what had happened; but it was either too simple or too complicated because he finally gave up with a bewildered shrug.

"Iss crazy!" he said, wagging his head.

Finally the door opened and two Martians strode in. They were larger than Krikki-Krik and looked assured and capable. I had the impression they were the sort who would know how elections were going to turn out and what was in the bag at Hialeah—on Earth, that is.

One of them, a dish-faced smiler, made a bee-line for Miss Murdock. The other, smiling even more widely, headed for Valerie.

Krikki-Krik said something and the professor put both hands to his head and rocked it gently.

"Ze winners," he said in a hollow voice.

"Well, I swan," Miss Murdock said, patting her Martian on the head. "I always knew I'd get me some kind of man."

"Oh!" Valerie wailed and covered her face with her hands.

Krikki-Krik sputtered something and the professor looked to the two women and smiled weakly.

"Zey are very wealthy Martians. Zey own big farms. Krikki-Krik says you are both lucky."

"A big farm?" Miss Murdock said contentedly. "Well, isn't that nice?"

"Zey will take you wit them tomorrow," the professor said. "Iss all set."

The two lucky Martians took a last delighted glance at their prizes, then marched out, pictures of happiness.

Valerie stamped her foot. There were tears in her eyes. "I won't go off to some Martian farm."

"Now, child," Miss Murdock said. "It's not as bad as all that."

Krikki-Krik said, "God!" suddenly and chattered at the professor.

"Ve mus' go vorship again," the professor said petulantly.

I remembered then that Godfrey is on the air just about as regularly as the system cue, and the prospect of worshipping him eighteen hours a day was rather bleak.

BUT there was no alternative. We went back to the great hall

where thousands of Martians were waiting in a frenzy for their

Supreme Being. Godfrey came on after the commercial, and I sat up

straighter and nudged my neighbor who turned out to be a Praying

Martian. He regarded me with wounded eyes and returned to his

meditations—and I nudged the other way and caught Valerie

in the ribs. It was a nice place to catch her.

"Ouch!" she said.

"Watch!" I whispered in her ear.

It was a pointless injunction since there was nothing else to do but watch; but she sat up straighter too.

Then, next to Godfrey's homey, good-humored face, appeared the thin and petulant features of Master Percy. This was the show he'd made while we were in New York, and now, after getting through the Heaviside layer and across space, it was being re-telecast here on Mars.

There was an astonished crackle from the Martians.

"Hey, that's me!" Percy cried out, with the instinct of a true ham.

The show went on, and except for Percy's brief appearance, it was as pleasant as always. But afterward, when the wall went dark and the great doors were opened, there was a rustle of confusion among the Martians.

They milled about us, crackling excitedly, and those nearest Percy, began bowing and bumping their foreheads on the ground.

Percy stood up, practically purring with contentment at all the attention he was getting. He stared about in surprise for a moment. Then, as more and more of the Martians began prostrating themselves before him, he got the pitch.

"They're adoring me," he cried happily. "They think I'm a God!"

"God!" I muttered.

The Martians stepped up the volume of their vocal homage until the hall was humming, and I saw with some alarm a rather pleased but stern expression flitting across young Percy's face.

BACK in our chambers I found myself alone with Valerie. Percy was outside in the corridor being worshipped by a group of radio-happy Martians, while the professor and Krikki-Krik were communing in another room. I hadn't the faintest idea where Miss Murdock was, and I couldn't have cared less.

Valerie paced the floor, wringing her hands. She looked very desolate. I was touched.

I went to her and caught hold of her shoulders.

"Look," I said. "I'm not going to let any Martian yokel carry you off to be a milk-maid."

"N-no?" she said hesitantly.

"Certainly not! I'm going to take you back to Earth. And I'm going to teach you more about life than you'll learn in two dozen libraries."

"Y-you are?"

"Yes!"

I kissed her then, thoroughly, effectively. For a moment her body stiffened and her hands pushed against my shoulders; then her arms went slowly about my neck.

Later—much later—we came up for air.

"Lesson number one," I said.

"I'm beginning to understand," she said dreamily. "Perhaps with a few more lessons—"

I began lesson number two.

The door opened during this beautiful teacher-pupil relationship and Percy entered. He let out a shrill shocked yelp.

"I have never seen anything so disgusting," he cried. "You must be out of your mind, Miss Jones."

Valerie moved away from me reluctantly. She glanced at Percy, and sighed. "It isn't every girl who has a chance to spank a Martian God."

"You'll probably never get a better opportunity," I said.

"Now just a minute," Percy cried, backing cautiously toward the door.

Valerie moved very swiftly and with great determination. She caught Master Percy by the scruff of his pants as he bolted for the door, and in a split-second he was over her knee and she was spanking him with tremendous enthusiasm.

I listened with pleasure to his outraged squawks.

When Valerie released him, much too soon, I felt, he dashed to the door and shook a fist at us.

"I'm a God, and you can't do this to me! I'll fix you!"

With that he ran out...

The professor and Krikki-Krik came in. I had my arm about Valerie's waist and was getting ideas—and not quite the ones you'd expect. I had a way to get us back to Earth, and to release Miss Murdock and Valerie from their commitments to the farmers.

"Professor," I said. "Tell Krikki-Krik this: that give-away shows depend on the prize. And that I've got a prize that will electrify and startle everybody on Mars. Go ahead, tell him!"

With a bewildered shrug, the professor repeated my message to Krikki-Krik, who reacted to it with definite interest.

"Okay," I said. "Give him the rest of it with all your eloquence, Prof. The main prize will be a free trip to Earth."

As the professor repeated my words, I felt that the circle had been completed. Starting with a free trip to Mars we were back, inevitably, to a free trip to Earth.

Krikki-Krik just about blew his top with satisfaction at the news. But before he could get away, I yelled: "One more thing, Prof. Tell him the first give-away has to be cancelled. Tell him that the girls are essential to the operation of the space ship."

"Oh!" Valerie cried happily.

The professor did as I told him and Krikki-Krik made no objections. He seemed eager to get started on the new show, and hurried out grinning....

EVERYTHING went smoothly. The show was a great success,

winners were determined, and the professor got started readying

the ship for the return trip to Earth.

There was only one hitch. Miss Murdock vanished along with her farmer-winner. I presume she figured a Martian in the hand was worth two milkmen in the bush. At any rate the time for the take- off found her missing at roll call.

"It's probably just as well," Valerie said. "She'll be happy here."

"She'd be happy anywhere with a man," I said.

Then as we were assembled and ready to leave for the ship a king-sized monkey wrench came hurtling into the gears. The door opened and Percy swaggered in, followed by dozens of stern Martians who carried nasty-looking spears.

Percy opened his mouth and cracked out something in Martian, and his spear-carriers ringed us in, the points of their weapons glittering under our noses.

"The plans have been changed," Percy said calmly. "I'm God around here, and I changed them. The professor can go back to Earth, but Valerie is going to stay with me. Eventually I'll need—er—a Goddess."

"Great jumping catfish!" I yelled. "And she turned down a Martian."

"You, O'Leary," Percy said sternly, "are going to stay here too. And be my body servant."

The professor took a big silver watch from his pocket with a curiously deliberate gesture. He held it by the chain and let it revolve slowly. Light bounced and glittered on its polished surfaces.

"Percy," he said in a gentle voice. "Vatch ze vatch."

"Huh?" Percy glanced at the watch, and his eyes moved back and forth with its motion. "I don't see what—" His voice trailed off slowly.

"Dot's better," the professor said, smiling. "You're tired, eh, Percy?"

"Well, as a matter of fact, I seem to be," Percy said in a hushed voice.

"You must rest. Take your royal guard wit' you and go to ze bedroom. Sleep like a God."

"Yes, I must do that," Percy murmured. He said something in Martian to his followers and then, moving like a sleepwalker, he turned and walked from the room. His guards followed him, crackling bewilderedly among themselves.

"Let's go!" Professor Hinesmuller said, with a sly grin....

WE waved farewell to Mars with happy hearts. I stood with my

arm about Valerie as the Professor locked us into the ship and

led the two Martian prize-winners to their seats.

"I feel happy about Miss Murdock," Valerie said softly.

"So do I."

"But I feel sorry for poor Percy."

"Where Percy's concerned," I said, "I feel sorry for the poor Martians."