RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Falsivir's Travels, 1886

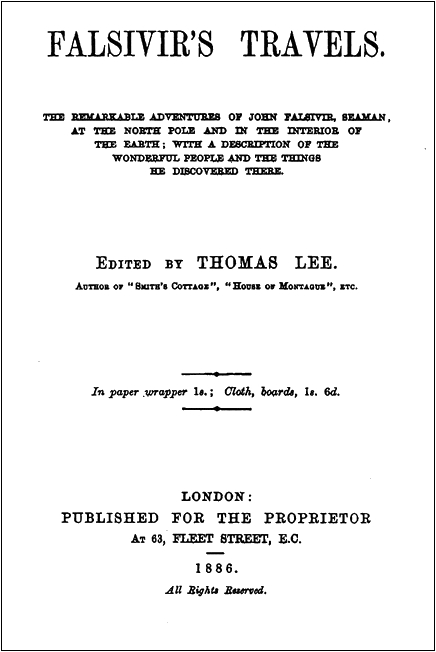

The Remarkable Adventures Of John Falsivir, Seaman,

At The North Pole And In The Interior Of The Earth;

With A Description Of The Wonderful People And The

Things He Discovered There. Edited By Thomas Lee.

Falsivir's Travels, Title Page

IT is many years since I returned from my last voyage, full particulars whereof I have mentioned in my book of travels, written soon after my return from the centre of the earth. I arrived in London, July 18, 1851, and went directly to my family who were residing at No. 18, Little Randolph Street, Camden Town, near the "Old Eagle" public house, where the busses used to stop. By my wife I was warmly welcomed home, the more so as it was supposed I was dead; but to all their eager inquiries respecting what had befallen me in my voyage I refused to give any account. My reason for this was the hope of receiving a substantial reward from the Government, and so I thought it best to tell my story straight to the proper person rather than allow outsiders to get the particulars.

Mr. Gladstone, to whom I first applied, readily granted me an interview, and listened patiently to all I had to say, frequently taking notes during our conversation. At length, after I had done speaking, he—with a smiling yet half-serious countenance—exclaimed "Do you seriously mean to say, Mr. Falsivir, that this strange narrative you have just related is strictly true?" I assured him that it was, and suggested that it could be easily proved that there was such a ship as the "Arctic Whale," with many other things relating to this vessel. His answer to this was: "I will have some inquiries made, and you may call upon me in a week from to-day." I thanked him, and was shown out by a footman.

At the end of a week I called again, but was told that Mr. Gladstone was out of town. I had an interview with his private secretary, who treated the whole affair in a very different manner from what I expected. "Mr. Falsivir," he observed: "we have made inquiries in this matter, and we find that there was such a vessel as the 'Arctic Whale', and that she set sail on the day you mention; and, also, that there was amongst the crew a man of the name of John Falsivir; but we have further proof that the 'Arctic Whale' was wrecked and all hands drowned. That being so, we cannot entertain your discoveries, real or imaginary." I was very much surprised at this, and wanted to explain more about it, but I was cut short with the remark that it was too much like Bruce's Travels in Africa to go down. "Besides," he observed, "all the learned societies have proved the centre of the earth is a mass of molten lava; therefore it cannot be hollow."

When I left Mr. Gladstone's secretary, I was very down- hearted, though not despairing. I next visited the Archbishop of Canterbury; but by him my discoveries were treated with contempt, and, with a wave of his hand, he, in a somewhat excited voice, exclaimed, "It's all false, for if the earth was hollow and inhabited the Bible would have told us all about it." After this I applied to several of the learned societies, but to no purpose, for, in every instance, my discoveries ran foul of their theories.

At last I was compelled to give it up, for it was plain to me that, until another voyage was made and still further proof obtained, I was only being laughed at for my trouble. Every time I heard of a polar expedition about to start I volunteered, but from motives of jealousy was refused. All the captains of these intended polar expeditions would listen to me and take notes of all I informed them—and, I have no doubt, made use of them in their voyages—yet declined to take me as one of their crew. As may be supposed, all this was a sad drawback to me. I could not go to sea, for if I had done so I should have stood no chance at all, and I could not keep steady at bricklaying (my trade).

On the 10th of January, 1860, my wife died; and the year following I lost my youngest child—the girl born while I was at sea. In the spring of 1858 my two boys went to sea, and remained sailors till the summer of 1862, when they joined the American army, under General Grant, and were both killed at the storming of Fort Pillow. This, to me, was a sad blow. I fretted a great deal, and quite neglected to push my claims as a discoverer, but settled down in a quiet, dull sort of way to my trade.

For several years I lived at 15, Southampton Street, Strand, and in 1875 was at work at the Law Courts, where I met with an accident: the iron hook of the derrick-chain struck me on the head, and knocked me off the scaffold. I was so injured that I was six months in the hospital. Upon leaving that institution I discovered I was no longer fit for my trade, and was thus compelled to seek the shelter of the work-house, being sent by the Guardians of the Strand Union to the poor-house at Silver Street, Edmonton. At the present time of writing, I have been an inmate about ten years, as Mr. Jackson, the gatekeeper, will inform anyone who may make inquiries.

I have but little to add. Some gentlemen, hearing of me and my extraordinary adventures, called upon me; and, being convinced of the truth of my statements, resolved to lay them before the public, and so allow them to form their own opinions.

—JOHN FALSIVIR.

IT is not everyone who has seen as much of the world as I have, or visited the parts I am about to describe; therefore, if I have the boldness to write a book of travels, I trust it will be admitted that I have good reason, since I am able to describe countries and people no other traveller has seen. At the same time, I admit there is but little to boast of beyond the journey there and back, for I must say, in all my journeyings, I have never been among savages, or in danger of being devoured either alive or dead—in fact, I have been treated with the greatest kindness and consideration. Therefore, I suppose, my account will not be considered so interesting as it would have been had I marvellous stories to relate of dangers by flood and field, of narrow escapes from death by savage beasts, or of cruel tortures by savage men. Not one of these dangers can I boast of; mine is but a plain, simple account of the parts of the earth I have visited, together with the inhabitants, their manners, laws, and customs. But, let me add, I am not an educated man, as I shall doubtless show; therefore I trust some latitude will be allowed me, and, in return, I will use my best endeavors to make my account as plain as possible, and to speak only of such things as I have seen or become convinced of.

I was born near Battle Bridge, on Thursday the 20th October, 1808. My father and mother were rope and twine spinners, and worked for a party of the name of Buckingham, near the Small-pox Hospital at Battle Bridge, as it was then called. Of my father I can remember but one thing, and that was drowning a white cat in the canal at Maiden Lane Bridge. My mother says I was not three years old at this time. After the death of my father, my mother put me out to nurse, and continued to get her living at twine spinning—that is, during the summer months; but, as she was now getting advanced in years and unable to stand the winters, she used to go into St. Pancras Workhouse during the cold weather, and take me with her.

Of my early days in the workhouse I can remember many little things, and I think I must have spent five winters there in all. I was, of course, separated from my mother, and well do I remember the scheme I used to adopt to see her. There was but one hour out of the twenty-four that it was possible for me to do so, viz., while Mr. Lee, the master, was cutting up the bread. I used to crawl on my hands and knees up to the open door, and then spring to my feet and run as fast as I was able. Of course he came out, knife in hand, and shouted to me to come back, but I heeded him not: I was round the corner in a moment, raised the large latch of the women's ward, and, panting, bounded to my mother's side; and I must say it was always a good half-hour before ever I was inquired after. Although I was very frequently threatened, I never was subjected to punishment.

At last, my mother's eye-eight getting so bad, she remained in the house altogether; and, at nine years old, I was put by the parish authorities to work at a cotton mill of some sort, but where I cannot say; I know we were taken every morning, and brought back at night, in charge of some man. My schooling had been but very little; in fact, I could scarcely read a word.

Work at the mill was not long for me. My brother Phil, who was many years older than myself, seeing I was getting useful, took me to work with him at Leeds Castle, in Kent, he being in the building line.

I might relate many stories of my boyhood days, but, as they were only such as happen to all boys, I shall refrain from doing so, simply saying that I worked for my brother several years, mostly in the neighborhood of Battle Bridge. It was about this time that my mother quite lost her eyesight. She lived, as a permanent inmate of St. Pancras Workhouse, to the age of 83, and died about 1842.

When I was twenty-one years of age, my brother Phil went out of his mind, and was soon afterwards taken to Hanwell Asylum, where he died. Not very long after, I, having a wish to go to sea, did so, and followed it, on and off, for many years.

When at sea, I think I must have been a great favorite with the captain, who was a north countryman, where they say all the pedlars come from, for I remember once being aloft longer than the captain thought necessary, upon which he shouted, "Now then, Falsivir, look sharp: remember you have not a hod of bricks playing with up there," (this was an allusion to my trade); and I made answer, "No, sir, nor a pedlar's pack."

"Come down, sir," he roared; this I did and was put under arrest, but was soon after let off and nothing more was said about it. After this, I and another committed ourselves in a far more serious manner. The ship was in harbor at the time, and we attempted, during the night, to desert, and stole the ship's boat for the purpose, but were detected by the marine on sentry, and ordered to come back, or be fired on. I did not want to go back, supposing we should be hung for deserting, and thinking we might as well be shot as hung; but, as my companion wished to return, we did so, and were placed under arrest.

The next morning I tried to make myself as comfortable as possible—for I expected no mercy—and, to pass away the time, borrowed a novel of the sentry to read. While so engaged, the captain passed the guns, between which I was a prisoner. Stopping short, and looking hard at me, he exclaimed, "Upon my soul, but you take matters coolly, Falsivir. Do you know you will be hanged?"

"I expect it, sir," was my answer.

"Oh! you do, do you? Well, perhaps I shall disappoint you;" and he walked on.

An hour after, to our surprise, We were released and ordered to go to our duty. A short time after this, a sailor was ordered up to be flogged. After he was stripped and tied up, he turned his head towards the captain, and said, "You don't do me justice, sir."

"How so?" demanded the captain.

"Falsivir deserted, and was not punished, while I am to receive two dozen for only drinking a little too much."

"Silence!" roared the captain: "do you compare yourself to Falsivir? Boatswain, do your duty, sir!"

From this it will be quite plain that I must have been a favorite with the captain.

Not long afterwards our ship was paid off and I got my discharge. I then got married and worked at my trade a year or two, but falling out of work I again went to sea, leaving my wife and two boys to receive my half-pay. Upon my return I found the children had increased to three, by the addition of a little girl, then about three months old. I, of course, demanded an explanation, and for my answer got a flood of tears, and a wish to know if I was without sin. Well, in the end I forgave her; but I went to sea again, and I am not sorry I did forgive her: it is one of the actions of my life I do not regret, for a sailor's wife is sadly neglected.

I shall pass over the remaining years, and come to the time when I joined the ill-fated expedition that was to give me a knowledge of the interior of the earth, and add another empire to the possessions of England—for of course she will claim it by right of discovery.

IT was in the early spring of 1848 that I shipped on board the "Arctic Whale," commanded by Captain H. Vernon, a north countryman. The vessel was a three-masted ship, of about 700 tons, bound on a whaling cruise. I did not like this sort of life, but my knowing the captain—he having been lieutenant in the Royal Navy and served on board the same ship as I had—induced me to go out with him.

During the summer of 1848 we had bad luck, the winter before in the Arctic seas having been unusually severe. However, the ship being well provisioned, our captain determined to winter upon the north-eastern side of the Island of Spitzbergen, and somewhat nearer the pole than the eighty-third degree of north latitude. During the last of the daylight, we made things as comfortable as we possibly could, and, strange to say, had the good fortune to catch a large number of seals—over 2,000 in one day—and, in the course of seven days, as many as four big whales; in short, had the season permitted, we could have loaded our casks with oil, to say nothing of the bone and sealskins. But while we were busy loading our ship the ice was setting fast around us, so that by the time we really had a cargo worth returning with there was no getting out. It was no use lamenting. One thing was certain: if all went well the next summer, we should be able to return with a valuable cargo; so we made up our minds to be as cheerful as we possibly could.

Among the articles which our captain had on board was a small balloon, and plenty of coals and chemicals. His object in bringing the balloon was to take observations by it from as high a position as possible, in case we were surrounded by ice—his intention being to secure the balloon to the deck of the ship by ropes and let it rise to as great a height as his tackle would permit, and, after seeing all he could, draw it down. During the winter, we had no opportunity of using it, but we did in the spring.

I have spoken nothing as yet of the scenery of the part of the world we were then in as it appears during the long winter months, because I believe others have done it much better than I am able. But it did appear something wonderful! After coming on deck, and so on to the forecastle—the only part of the ship we had not wrapped up with sail-cloth—at midday, to see the stars shining as bright as if it were midnight; to look at the snow-covered ropes and rigging of the ship, their white outline contrasting so strangely with the dark blue star-lit heavens, where not a breath of wind stirred; your lips and eyelids, if you closed them, seeming fairly glued together with the intensity of the frost; all around as still as the grave, save, now and then, for the pitiful howl of the dogs, who seemed to feel the fearfully long hours of darkness as much as man did! Nor was the prospect better on either hand, for nothing but one apparently boundless field of rugged ice and snow met the gaze, its pure whiteness causing the blue of the heavens to appear still more dark, and us to wonder if the sun would ever return, and, with its warm rays, release us from our ice-bound prison.

Below deck everything had been done that could be done to exclude the cold: all round the sides sail-cloth was hung up, behind which we had stuffed plenty of moss; and the smallest possible opening was left for a door.

Every day we went through a routine of business, whether necessary or not, such as beating the snow from the sail that covered the upper deck, sweeping, and cleaning; then reading, drilling, singing songs, and play-acting—in short, everything that could be thought of to keep our energies from going to sleep. The captain amused himself in studying the heavens, and would point out the pole star nearly over our heads, while we would sit for hours and listen to his description of the stars, comets, and the great Northern Light so often visible.

It was during these long, hours of study that the captain formed the resolution of proceeding still farther north during the next summer, and, if he possibly could, reach the pole. He would say "I really believe we are farther north now than any ship has ever been. Another 600 miles would bring us to the pole, over which I will if possible hoist the flag of old England." I cannot say that many of us shared his enthusiasm. The truth was we were anxious to return home; not so our captain, as we shall see.

I believe it was the last day of January that we got the first positive streak of daylight, at about half-past eleven o'clock, and it continued from then until the 10th of March slowly, but steadily, to increase. On this day we, for the first time in nearly six months, saw the sun from the masthead, and, to say the least, we worshipped it. And who could wonder? Let anyone be in our condition, and I think he would have done the same. There was one thing I thought remarkable, and that was, for the first five or six days after the sun rose, the weather was colder than at any time during the winter, and it froze harder! Our captain said it was what he expected, and tried to make us understand the reason for this; but we paid little attention to him, thinking more about getting out of our present condition than aught else. But if we were anxious to escape, not so the ice to let us; for day after day passed without any sign of its breaking up.

Weeks and months passed in this fashion. It was now the latter end of June, and still we were icebound, though melting fast. On the land the ice and snow had disappeared, and the moss had grown several inches. All this month we had seen swarms of geese and ducks flying towards the pole; a something that set our captain thinking. We had been several miles inland, but discovered nothing worth notice, except some traces of iron and copper, leaving the captain to suppose both of these might be found in abundance if searched for.

On the last day of June, the balloon, with the captain in it, went up for the first time. When we drew him down again, he informed us that in a few days we should be free, for he had discovered open water to the eastward about twenty miles distant; and, it was his opinion, the ice was breaking up rapidly and flowing southward. "If so," said he, "we must follow it at the end of the summer. If we did so now we should soon be in the midst of it, and crushed. So, my men, our best course is, to either stay here till the ice has passed us and so left the sea open, or, if we can see a chance, push our way through northward, till we are fairly behind it, where we shall find open water; for I believe, as the ice flows south, it takes the cold with it, leaving the pole free, and therefore warm; and I think the ducks and geese know it. At any rate, I shall act upon this supposition."

During the next few days we were busy preparing to set sail, but the ice was in no hurry to let us out, and thus all July passed away. Each day we could see that the distance between us and open water was getting less; but it was not till the 1st of August that the ice about our ship gave way, and swung round to float off with the crushing grinding masses that were everywhere visible, pressing southward. Had we not been protected by a rocky neck of land we too should have been swept away with it, and our doom quickly sealed. But it went, and we were safe; and the weather became much warmer immediately.

On the 4th of August, the wind being favorable, we set sail, bearing N E by E. Even now, great care was necessary to steer clear of the floating ice. For the next fourteen days the winds were so light and contrary that we made but little progress; but after this we saw no more ice, and a breeze springing up we made better headway.

On the 24th of August the man on the look-out called "Land on the starboard bow!", and immediately there was a rush to look at it. I shall never forget how agitated our captain was, when he saw land: he fairly trembled with excitement; and, as I passed, I heard him mutter "By heavens, there's a polar continent; and I have discovered it!" As we neared the shore, the captain ordered the lead to be hove, to try our depth. While this was being done, he was busy examining the land through the glass. After we had got somewhat nearer, the captain informed us he could see trees of some sort, and either grass or green moss, but no sign of snow; and added, "There is far more sign of vegetation here than further south." After some little searching, we found a good harbour and cast anchor, after which the captain went on shore, taking me and some others with him. On landing, we were greatly surprised to find a country quite capable, so far as soil and climate were concerned, of being cultivated—that is, to a certain extent. It was the captain's opinion that the winters here were no worse than in Iceland, fifty miles from the coast. After making several short excursions inland in different directions, and taking some observations from a good altitude by the aid of the balloon, he came to the conclusion there was land all the way to the pole; and it was, he said, not more than 150 miles in a straight line. He resolved to undertake the journey on foot. For this purpose he chose ten of the ship's company, out of fifteen volunteers, to accompany him; the remainder to stay and take charge of the ship.

On the 29th of August we started on our journey towards the pole, taking several dogs with us, our guns and ammunition, and our balloon, folded up, with certain chemicals for the purpose of making gas, in case we wished to use it. All these things were carried in a light truck, made like a boat with wheels, which was drawn by our dogs, with a little assistance from ourselves. The sun was by this time more than two-thirds towards the horizon, and every day visibly sinking; but the weather was mild and no sign of frost. As we journeyed on, we were surprised at the level appearance of the land, and the abundance of game, such as deer, foxes, hares, ducks, and geese, besides a number of small birds. There was likewise traces of bears, but we saw none. In the first twenty-four hours we made about thirty miles, leaving us about 120 to the pole. During our first day's journey we crossed two rivers flowing southeast, and when we camped it was by the side of a stream which flowed south and evidently emptied itself into one of the rivers we had crossed. As we journeyed we found the trees increase in size, and grass very abundant. We saw some wild fruit like blackberries, and along the wet borders of the stream a great quantity of huckleberries, of which we eat a good many. During the next twenty-four hours we made another thirty miles, our journey being interrupted much by small streams: we saw no large rivers. On the 31st of August and the 1st of September we were compelled to lay up, owing to the heavy rains; but on the 2nd we made about ten miles, the country appearing much the same, though evidently improving both as regards climate and vegetation. On the 3rd we saw some mountains; the land, being generally more hilly, caused us to make slow progress, and again we did not do more than ten miles, which rather disheartened us, and the captain feared we should have to give it up, for we felt certain we could never climb the mountains that were before us.

On the 4th of September we discovered a pass by which we got to the other side of the mountains without much trouble. Here water appeared very scarce: no rivers or streams of any sort; the ground, too, seemed parched as if for want of rain. From this we concluded no rain had fallen here, although it had delayed us on the other side of the mountains. We had made about ten miles here when our progress was suddenly stopped, for we found ourselves upon what appeared to have been the bank of a vast dried-up lake, or inland sea, but of such a depth that none of us could discover the least trace of bottom. The sides, as far down as we could see, were smooth and regular, and nearly perpendicular: far too steep for either man or beast to descend. As may be supposed, we gazed with amazement at the strange scenery before us. The question was:—Is this a dried-up lake, or the cone of some extinct volcano? for as far as we could discern by the aid of our glass it had such an appearance a good twenty miles on either hand. Again, what was the meaning of this strange circle of such mysterious depth?—for circle it certainly was if it continued in the same regular bent form it had on either hand of us; and if it did it could not be less than 250 or 300 miles in circumference. How deep is it? was a question we asked of each other, over and over again. We often directed our glasses downwards, but black darkness was all we could discover.

At length we resolved to camp for the—I was going to say night, but, of course, night or darkness had not set in, nor would it for some time, as the sun was still above the horizon—but as our watches told us it was night in old England, we so considered it, and prepared to rest accordingly. After we had made everything comfortable, and before we laid down to sleep, we had a long argument upon the nature of the strange circle by our side, for we were camped upon the very brink of it. In the captain's opinion, it was the cone of an extinct volcano. The mate said it was a dried-up lake. For myself I could not think it either; it was too large for the first, and too deep for the second. "Then what is it," asked several, "if neither one nor the other?" That, I said, I could not tell, unless there was some way or method of reaching the bottom.

"I will tell you a way," said the mate, "if any of you have the courage to make the attempt; and that is by the balloon, with ballast enough to sink you down; upon reaching the bottom, throw out the ballast, and you will rise again to the top."

"Yes!" exclaimed first one, then the other, "but suppose when we come up the wind does not bring us back again to this spot? or suppose, and suppose—"

They were going on in this way when I interrupted by saying: "It's no good supposing; there has been enough of that; give me the balloon, and I will descend and leave the rest to chance. We have come all the way from England, and now want to discover the north pole; and we find it, not a mountain of ice or polar sea or mass of iron, as some of us have thought, but, as far as we now see, a fathomless hole in the earth. If we return without making some effort to unfathom the mystery, we shall be laughed at, and if we reach the bottom, who can tell but we may be able to add much valuable information to science. And I do not believe it is more than one or two miles in depth. Look at the sun: it appears no more than the height of a man above the horizon, and is hourly becoming less. Now, if that valley was only half a mile deep I believe it would be dark at the bottom."

My argument appeared to carry some weight with it, for, after a short consultation with the captain, it was agreed to unpack the balloon, manufacture some gas, and allow me to make the attempt to reach the bottom of the valley.

During the hours allowed us to sleep, and of which most of my companions were availing themselves, I was restless, turning about and thinking of the task I had imposed upon myself. I naturally wondered what I should do, after my balloon arose from the bottom of the valley, if the wind should carry me across to the other side, for no arrangements had as yet been made. I felt certain it would do so, if it did not shift, and the breeze was coming straight from behind us. At length I fell asleep. After a few hours I was awoke by one of my companions, who informed me that breakfast was ready, and the balloon was being prepared. I arose, packed up my sleeping bag, washed, and had my breakfast, after which I received my instructions from the captain—or rather (I might say) we held a consultation respecting what was best to be done; and, first of all, as it would be at least three o'clock in the afternoon (that is, if there was such a part of the six months daylight as afternoon) before the balloon would be ready, it was decided to send out two exploring parties, one to the right hand, the other to the left; not only to render me assistance if I needed it, but to ascertain if the basin-like shape continued in the same manner as where we then stood, and to see if there was any way of descending into the valley.

If anyone had asked me what my thoughts were, as I continued to pace to and fro past my companions (who were busily employed in manufacturing gas for my balloon) I could not have told them. I only know I again and again directed my gaze across and down the sides of that dark mysterious pit, and that I often repeated "Wonderful, wonderful!" Sometimes the breeze seemed to die away, then suddenly spring up again, but always from the south, reminding me of the trade winds just before you fairly enter them; by the south I mean the quarter we had come from, for one thing is certain, if we were only one degree from the pole, it could hardly come from any other quarter. I own I should have felt much easier had I been sure the wind would blow from the other side of the valley when I wanted to return; but I would chance it.

Time was passing, and my balloon was nearly ready. My sleeping bag and provisions were put into the car, for, as the captain said: "When you come up you may be blown right across, and as we cannot probably get round before three times twenty-four hours, you will have to camp on the other side, and await our coming up. And as we shall divide, one party going one way, the rest the other, we are sure to fall in with you, after which we will make our way back here, and so to our ship as fast as possible, while daylight lasts."

He likewise gave me some information respecting the route he should take, but, occupied as my mind was with the undertaking I was about to enter upon, I paid but little heed to what he said, and now I don't remember one word of it. Had I studied the countenances of my companions and their silence as I moved among them, I should have read in their faces the opinion they had of my mad undertaking; but I did not. The captain appeared cheerful and talkative enough, but not so the men; but then he, I believe, was a man who thought no more of my life than he did of the Eider Ducks he shot: he wished me to ascertain the depth of the valley—he getting the credit of any discovery I might make—and so encouraged me to make the attempt; but I now often think how strangely he was out in his calculation, for I alone am the survivor of that ill-fated expedition.

Strange and incredible as it may appear, I trust none will be presumptuous enough to doubt my word until they have visited either the north or south poles. It is an easy thing for some people to sit by their firesides and read the accounts of travellers, then, casting the book aside, exclaim: "It's a lie! I don't believe a word of it!" To all such I can only say, "Be it so. I expect neither honor nor profit from what I now write, so care nothing for your opinion. I have no great name to lose or wealth to sacrifice, so do your worst."

But to my narrative.

THE balloon was ready; a dozen strong hands held it as I stepped into the little car and closed the netting; after which my companions, still holding the car with one hand, shook mine with the other.

I must here describe what had been done for me: the balloon was heavily ballasted, I might say almost on an even balance; still there was some little rising power (at least it was so supposed). In the car, besides ballast, was my sleeping bag, some food, a revolver, with powder and ball, a telescope, a box of matches, an axe, and some other trifles, a compass—apparently in very bad working order, as were all of them—a kettle to boil water in, some writing paper, and black lead pencils; these last were for me to make a sketch of what I saw, if it were possible for me to do so. In my pocket I had a Bible and a small book on astronomy, and, last of all, Ben handed me a plug of tobacco. As I finished winding my watch,

"Now," said the captain, as soon as he saw I was nearly ready, "let the balloon drift a few miles across before, you descend, and don't waste your gas. Now, when you are ready, say so."

Standing up in the car I fastened my fur suit well on, for I expected I should find it very cold; then, taking a good bite off the plug of tobacco handed me by Ben, I let the rest drop into the car, for the captain at this moment handed me a drop of brandy in a tin cup, remarking as he did so, "there is a bottle in your provision basket." I nodded thanks as I drank the brandy, replaced my quid, and then, with a hearty "God bless you all" by way of signal, I was let go. Very slowly I arose, but drifted fast; had I not been close to the edge of the chasm, I should have dragged along the ground. I saw my companions gazing after me as I waved them a last farewell, and then I began to look after my balloon, which I found was increasing in speed in a surprising manner, the farther I got from our starting-place, and showing an inclination to descend. I think I must have been four or five miles from my companions, as I could not make them out fairly, even with my telescope, when suddenly—and apparently without cause—the balloon began to go down with fearful rapidity.

I can scarcely describe the state of alarm I was in. I quickly laid the telescope down, intending to throw out some of my ballast, but leaning over noticed the top of my balloon was pressed inwards, as if a great weight was upon it; at least, I concluded so by the manner in which the sides were bulged out, and it was all I had time to notice, for the next moment I shot into darkness as black as ink.

I now hesitated to throw out the ballast, lest the balloon should turn upside down. "Oh, heavens! what does, what can it mean?" I gasped, as I took the quid of tobacco out of my mouth and let it fall. Where was I going? Then a giddiness seized me, a tightness across my forehead and a gasping as if for want of air, but perhaps from the super-abundance of it. Be that as it may, my senses left me as I sank down in the car, which at this moment was descending at the rates of 100 miles per hour. [This calculation I made some time afterwards; and that likewise that from the time I left my companions until the time I became insensible was not more than fifteen minutes; and now that I have been the journey a second time, I feel certain that it was terror alone that caused me to lose my senses; nor need it to be wondered at. Let any number place themselves in the position I was, and not one in a hundred could have retained their reasoning faculties.] The reader will doubtless ask where I was going, and I am at a loss to tell. It is best to state things as they really are, or to speak of them as they appeared to me when I recovered my senses, which I did some five hours after I lost them.

When I awoke to reason I found myself in the midst of darkness, blacker than anything imagination can picture; but whether I was travelling up, down, right, or left, I could form no idea—in fact, for a long time I could not tell whether I was moving or not. But this I believe was caused by the slowness with which my senses returned; for at length I did comprehend that the balloon was travelling, although in what direction I could not conceive.

I remember I felt I was going to destruction; that death was my doom; and I wished I had died when I lost my senses, as all would have been over. But I tried, and did at last succeed, in resigning myself to the will of Providence; After this I fell into a better frame of mind, and began to reason with myself to see if it were possible for me to ascertain where I was journeying.

Then, feeling stiff and cramped in my uncomfortable position, I turned to ease my limbs, and in doing so I felt the different things in the car. Then I thought of the brandy in my basket; and it is not to be wondered at if I drank some, though only a little, for I am in no way partial to much drink; after this I felt better, and began to ask myself some questions. Among the rest, How long have I been travelling; and Am I still descending? As to the last, I felt it must be so.

I next wondered what time it was, and took out my watch to ascertain if it was going; placing it to my ear, I found it was ticking away quite regularly. By this I knew I had not been travelling for thirty hours—that being the time my watch would go, and I remembered winding it up just before I started. I had a mind to open it and try and feel the time; but fearing I might injure it, I did not do so.

I thought of lighting a match, but, knowing fire was dangerous in a balloon, refrained.

Then I drank some more brandy, and whether it was this, or a callous indifference as to what became of myself, or downright weariness I know not, but I fell asleep, and so continued for several hours—I should say quite ten.

When I awoke I was much refreshed, though somewhat stiff from laying so long in one position. Again taking out my watch and holding it to my ear I found it was still going. I next drank a little more brandy, and then fell to wondering as to where I was going, for going I was.

Presently I thought, and afterwards felt sure, that I heard noises, like the howling of the wind, and, as this—slowly, it is true, but plainly—increased, I felt certain I was nearing either the bottom of the pit I had entered or the earth somewhere. As the darkness was as black as ever, I began once more to feel alarm at the danger I was in. Then an idea entered my head to throw out my ballast, for I reasoned, "What is the use of my reaching ground? I could not live in such darkness as I am in, if I landed in safety" (a thing I very much doubted my ability to do without some light), so I considered I might as well float as long as fate would let me, and then perish, as to do so now; besides, we all have a feeling that so long as there is life there is hope.

As the noises were still increasing, I commenced to throw out my ballast, after which the sounds grew gradually fainter, and I heard no more of them. Well, I thought, I can do nothing more but wait, and ascertain what fate has in store for me. About this time two ideas entered my head. One was that I was going right through the earth, the other that I was only going round and round in the valley in circles; but I considered, if that were so, I ought to be able to see the stars. Then a terrible thought came into my head, that, perhaps, I was blind. I trembled at the dreadful idea. Again I took out my watch and listened; it was still going, but ticking rather fainter (which it always did when nearly run down), and this showed I had been in my present dangerous condition, for thirty hours. That the balloon should bear me up for so long a time I thought most wonderful, and concluded I could float but little longer; but if I were descending all the time of course there was nothing to wonder at.

I was again giving way to despair and lowness of spirits (caused as much, I think, by the want of food, for I had ate nothing since I started, as the danger I was in), when, for the I believe thousandth time, I strained my eyes to see if anything was discernible, and felt sure something like light was visible directly over head, but rather faint, as if thick clouds were between me and the light.

Pushing myself as far over as the net work would let me, I gazed with an eagerness scarcely imaginable, until I felt certain that not only there was light, and my eyesight still left to me, but that I was rising out of the valley as rapidly as I had entered it; my balloon I saw was not bulged out at the sides, but stretched out to its full length. I shall never forget the sigh of relief I gave as I became convinced I was once more returning to (as I then supposed) the surface of the earth; nor will it be thought unmanly in me when I confess I sat down and cried the sweetest tears I ever shed.

But my moments for this kind of relief were few, for daylight increased so rapidly I could scarcely comprehend the cause; fancying myself coming out of the same place I had entered. Once more leaning as far over as I could, I looked upward, and, to my great surprise, saw, right over my head, what appeared a large moon, obscured by fog and vapors. After gazing in amazement and wonder for a moment, I began to look about me right and left, the daylight increasing rapidly all the time.

At length, to my great astonishment, I could see it had become as light as day, also what appeared like a wall of cloud on one side of me, and rising apparently up to the heavens.

I strained my eyes until blinded by tears, caused by the glare of daylight, but could not be certain if it were clouds or mountains. I tried if I could better comprehend things by the aid of my telescope, but without success. After a few minutes spent in restless astonishment, first gazing up and down, then right and left, I began to understand that I was still in the same mysterious valley; and that what appeared clouds or mountains was merely the sides of it. But what to make of the strange sun in the heavens above me, shedding as it did both light and warmth, I knew not. I thought, when I entered this place, that the sun was only a few degrees above the horizon. Now this strange sight was directly over my head. Presently, turning about, I discovered that the cloud-like appearance I had seen on the right was now beneath me, and fast disappearing on the one hand, becoming more visible on the other. By this I thought I was nearly out of the pit, and fast drifting towards the open country. As may be supposed, all I could do was to gaze and wonder, as well I might. Suddenly I thought I would look at my compass, and did so, but could make nothing of it, for it would point only downwards. Laying it aside, I looked around me, and soon after found I was clear of the place I had been in.

Finding it very warm and being more at my ease, I took off my fur coat and ate some victuals; after which I saw I was fast drifting over a country not only inhabited but well timbered and watered, for I could see both rivers and forests, as well as houses and farms. I now began to wonder if I ought to descend, but did not like to do so, being terribly confused by the novelty of my situation. But I was not to be left long in doubt, for I found that my balloon, which had by this time left the pit I had come out of quite 100 miles behind me, was fast nearing the earth, so that I had no choice. I observed that the sun above me appeared slightly eclipsed, more so than when I first saw it. I again directed my glass downwards and could see people running about, apparently men, women and children (as I took them to be), dressed somewhat like the highland Scotch. I also saw what appeared to me as men pushing perambulators with children in them, but could comprehend nothing fairly. Half-an-hour after, I had descended to within 150 feet of the ground, and to my great terror and alarm saw running after me about fifty of the greatest monsters in the form of men that I could have dreamed of. After running a long distance, they suddenly paused and made a great shout, and then began to throw large round stones, some of which nearly hit my balloon. Seeing this, and fearing I should be killed, I commenced to throw everything out of the car that was at all weighty. This lightened the balloon somewhat, and I got away, the huge monsters pausing to pick up what I had thrown out.

For some distance after this, my course lay parallel with a good, straight road, down which there was coming after me about a dozen gigantic men, pushing large perambulators (as I supposed them to be), in which were either men and women of my own size, or children of the giants. Once more my balloon was fast descending, but, to my relief, I found I was rapidly nearing a city. This gave me confidence, and made me think I was safe; for I have always found that, although people in country parts will more readily relieve a beggar in distress than people in cities, yet, should either their fears, prejudice, or superstition be aroused, they will more readily maltreat him, the which has made me think that country people are more ignorant as a rule than city people. But I was still in great terror and alarm, so much so that I could not look after my balloon. At last it got stopped by two large trees, the car being at this time not more than ten feet from the ground, and in a good-sized field, alongside of the road. Throwing open the gate, my pursuers entered and ran up close to me, the giants still pushing their perambulator-like carriages. Making sure I should be killed, and being determined not to fall without a fight, I cut my netting and tumbled out of the car as nimbly as I was able, drew my revolver, and, placing my back against one of the trees, shouted that I would shoot the first one who molested me. Whether it was the tone of my voice, or my gestures, I know not, but certain it was that all the monsters who were not pushing carriages kept a respectable distance, and those who were pushing the carriages appeared to be controlled by the people of my own size who were seated in them.

The whole scene was a strange one, and I shall never forget it. My balloon was over my head, wedged in the trees, and I with my back against one of them, revolver in hand, my hair blown about by the wind; and before me, in a half-circle, the strangest people I had ever seen. Their numbers were increasing every minute. There were giants of all heights up to thirty-five feet; and many men and women of my own size. The giants were all of a copper color, but those of my own size were, apparently, painted in all the colors of the rainbow, though, if possible, more brilliantly. As I stood at bay, I thought that the crowd surrounding me looked like a mob who had got a thief in their midst, whom no one cared to lay hands upon, but all determined that he shall not escape, they having sent for a policeman, who is on his way. One monster just before me, with a head of hair frightfully neglected, mouth and eyes wide open, had my tea- kettle on the end of his little finger; another held my provision basket in the same manner. Some five or six were closely examining my fur suit, and a group beside me were evidently watching an opportunity to tear down my balloon; but were either afraid or not allowed to touch it.

I was surrounded in this manner about half an hour. During this time I discovered that, no matter how much strength the giants might possess, they were entirely under the control of the beautifully-painted people of my own size. I saw several of the latter strike the giants about the legs, driving them back howling with pain. Just as I was beginning to wonder how much longer I was to be made a show of, I observed all of them to be somewhat moved, and to turn and look towards the gate. Presently there was an opening made, and up came one of the perambulator- like carriages, pushed by two giants dressed very showily, in clothes ornamented with a number of different metals, cut in various shapes and highly polished. Seated in this carriage was a man a few inches taller than myself, or about six feet three or four inches; his face was brilliantly painted in different colors; his forehead, neck, and ears were the finest and most glossy black I had ever seen; his cheek and lips were a splendid scarlet, as were his chin and eyelids close up to the eyebrows. The eyebrows and moustache were black, but the beard (a large one) was a golden color or amber; his eyes were likewise black. His hands were white and delicate, with the exception of one or two fingers which were a bright yellow and green; in short, all the colors were as bright and beautiful as those of a humming bird. As soon as the carriage stopped he got out, and I could see at once he was a person of some consequence, for all the giants went down upon their knees, the people of my own size standing quiet. Respectfully approaching to where I stood he said something unintelligible to me, and then made signs and pointed to the sun, but I did not understand him. He asked those of his own size about him some questions, and by their gestures I could see they were describing my flight and their chasing my balloon. As they were talking my balloon slipped from the trees and fell at my feet, hiding me for a moment or two from their sight, but I soon disentangled myself. The gas had all escaped owing to the balloon being so torn.

The new arrival again addressed me for a minute or two, and then, in a voice of authority, said something to those about him, whereupon the giant with my kettle crept up close on his knees and laid it down at my feet, as did all of them who had anything of mine. By this I saw I was not going to be hurt, so I put up my revolver. He then made me some signs to get into the carriage, which I thought it best to do; but first I took my brandy bottle from the car, it being fortunately unbroken, and drank from it. I likewise had something to eat out of my basket, the contents of which were not lost owing to a giant having caught it in its descent. After this, thinking it best to be on good terms with these people, especially the giants (of whom I stood in great dread), I resolved to divide what I had amongst them. My kettle I returned to the one I had it from and my provision basket to him who caught it. My plug of tobacco I offered to one of my own size, and I shall not forget his fashion of taking it. Picking the leaf of a plant, he wrapped it around finger and thumb, and then, gingerly taking the tobacco, bent his body so that it could not possibly come in contact with any part of his dress or person, and slowly brought it up to his nose. Nor can I easily forget the look of disgust he gave as he let it fall, plainly showing that he knew nothing about tobacco, at which I wondered, for at this time I still fancied I was upon the surface of the earth, but in some foreign land I had never heard of, yet how I got there I could not tell; and I fancied there was no part of the civilised world but knew all about tobacco. I did not laugh at the time, but have often done so since.

Meanwhile the personage who had addressed me stood coolly looking on with folded arms, betraying neither surprise nor emotion of any sort, although I could perceive he was in deep thought. As soon as I had made an end of giving and eating, he once more made signs for me to enter the carriage, which I did with much fear and astonishment. My head ached fearfully, and I scarcely knew whether I was awake or not, although I saw and remembered many things. I recollect the tone of voice with which he ordered the two giants (who I found out afterwards were his servants) to push the carriage. I remember that none of the crowd followed us. I made a calculation that the giants pushed us, along a most beautiful road, at the rate of twenty miles an hour, although the journey was short. On the way I saw some giants mending the roads, and others working on the fields. I saw a man standing on his head. I likewise noticed that everything I saw growing was planted in rings, one ring inside another.

We passed cart-like vehicles and trucks loaded with merchandise; but all worked by giants. Not a horse did I see anywhere. Soon we entered a city, the streets of which were in circles, and the houses, which were built of wood and most beautifully carved, standing singly, all of which were two stories only. But I saw no houses in the city such as the giants could live in. [I afterwards found that these people did not live in the towns or cities, but in the outskirts, a place set apart for them. And they were not allowed to walk in the streets of the town, unless engaged upon some business for their masters. But I shall tell more about this later.] I was amazed to see what a number of people there were painted [it was not paint, but the natural color of their skins, but this I did not know then]. The women I thought the most dazzling creatures imagination could picture; but the colors of the children, as I took them to be, appeared dull and somewhat faded. Here again I made a great mistake, for those I took to be children were really old men and women; but more of this by-and-bye.

After being pushed a mile or two into the city, and proportionately stared at, we arrived at a building large enough even for the giants to live in. Just before reaching this house, which was the palace and residence of the King and his prime minister, I saw a carriage pushed by two giants, in which were some six or seven men of my own size, all standing upon their heads, which, as one may suppose, I thought very hard to do, and every moment I expected to see them tumble out and break their necks. Pushing us up to the entrance, the giants stopped and wiped their faces—for it was very warm. As they did so, a man, handsomely dressed, and whose face and hands were of marvellous colors, came and let down the steps. He acted in a ceremonious manner towards him in whose company I was, and formed a circle by swinging his right arm slowly round; but he was evidently astonished at seeing me. Upon receiving some instructions from my conductor, he motioned me to follow, which I did. I was then led into a sort of hall, the walls and furniture of which were beautifully carved and inlaid with different metals, all highly polished. I had but little time to notice details, and less inclination, for my head was aching sadly. I was next directed to sit down upon a chair beside the table (in the hall), where, placing my arms upon the table, I laid my weary head upon them; nor did I look up, although I was sensible that many came and went, gazing at me, talking both to and about me, but I heeded them not.

At length one came and felt my pulse. By this I concluded he was a doctor, so raised my head and told him how I felt, but he understood nothing I had said. After a good deal of talking to those about him, I was beckoned to rise and follow one of them, which I did. When he had led me to a bedroom which I will describe later, he made motions for me to undress and go to bed; and I was quite willing to do so, for I felt very ill. My attendant left me for a short time, during which I looked about and into one or two other places and apartments. I was, however, able to notice little except that, so far as ease and comfort were concerned, there was nothing wanting.

I had barely laid down, when in came the same man that had brought me there, carrying in his hand a cup (which I afterwards found to be of polished iron) in which was a draught of some sort sent, probably, by him who had felt my pulse. I did not hesitate, but drank it at once, and then laid down again, for I felt quite sure, from what I had seen of these people, that they would not hurt me, or allow the giants to do so. After I had drunk the draught I fell into a quiet sleep; neither was I troubled with bad dreams, as I feared I should be, after the excitement I had undergone.

When I awoke I felt a little refreshed; but it was night. I well remember my first thought, on opening my eyes, was What is to-day? and next, Where am I? Then, as in a dream, all my adventures came to my recollection with a rush. I say like a dream, for I felt that I must have been, or was, dreaming. I remember I did not move hand or foot, only opened my eyes, and lay thinking, or trying to think.

There was no lamp burning in my room, but a mellow sort of light came in at the window, as if it were moonlight. At one moment, all I had gone through came upon my memory with a force that bewildered me; the next, I could remember nothing distinctly; then a confused heap of thought came into my head, in which giants, painted people, balloons, and pitch darkness seemed jumbled up together. This I afterwards thought surprising, because while I slept I had no disturbing thoughts. But I soon fell into a quiet state of repose again, and so continued till nearly morning.

Upon my waking a second time I started, then sat up, and commenced to rub my eyes. Yes, I was fairly awake now; but where was I? I slipped out of the bed and walked towards the window, which I examined carefully, my mind full of fear and wonder. Then I looked through the—yes, reader—glass upon the scene before me, then upwards, and saw what appeared to me like the Aurora Borealis, only instead of the bright pointed rays of light darting upwards, it was in this instance in the form of a rainbow reversed, and part (as I supposed) behind me, which I could not see because of the building, and so brilliant was its light no moon could surpass it. Nor was this all, for at a greater distance, right through this northern light appearance, and yet seemingly mixed up with it, was the most gorgeous golden light I ever saw, somewhat lined or shaded a little like the moon, but upon a scale many hundred times larger. "Wonderful, wonderful!" I exclaimed, "but wherever I be?" Then I thought I would look at the stars, and my eyes quickly travelled the whole expanse before me as far as I could see, but not a star could I discern. With a sigh, I turned to examine the window, thinking: "It's no use, I must be dreaming. And yet I can pinch myself and feel the pain; I can reason, and can see plainly this is a glass window (and strong glass too); I can see it opens like two doors, and that there is a garden, and that the breeze moves the trees; and I can hear what sounds like the neighing of a small pony (although, if it is a pony, it must be a very little one); so I cannot be dreaming." I thought I once more heard the distinct neigh of the pony, but in another part of the garden, as if it had broken loose and was running about.

Presently, observing there was a balcony, I tried to find the window-fastening, and succeeded. I opened it, and stepped out into the clear, cool night air, which I felt the more as I was only in my shirt and drawers. Then, as I again scanned the heavens, as far as the angles of the building would allow me, to my great surprise I saw that what I had supposed to be the Northern Light was a halo, which surrounded some large dark round object—less dark on the near edge—directly over my head; but no stars could I see. "Strange," I thought: "I have visited most parts of the world, but I have never seen a sight like this; and I have noted the stars a little. At any rate, I know Jack and his team. If I could only see that, I should have something to guide me; but no, not one;" and, with a sigh, I turned in and shut the window, the voice of the pony sounding closer under it. I then crept into bed, for I felt cold. At the same moment another sound met my ears, just outside my room door, which led me to think someone was standing sentry over me. I was not mistaken, as I afterwards found.

Covering myself up with the bed clothes, which were more like silk than anything else, I commenced to reason with myself. I could arrive at no settled conclusion as to my whereabouts; all was conjecture; yet one thing was certain, viz., that I had descended into the earth, and had travelled for over thirty hours in total darkness, but at what speed I was at a loss to tell. If my starting and exit were anything to go by it must have been fearfully rapid, and my journey many hundreds of miles. Whether I was through the earth or inside it I could not satisfactorily decide. I thought that I must be inside; yet I could hardly keep to the idea. There were so many things to confound it. "For," I argued, "if I am inside, where does the light come from? for light there is; and if on the outside, whereabouts, and what has become of the stars? Again, if I am on the outside, whence these singular people, and this strange light in the heavens both now and yesterday? and further, if I am on the outside of the earth, I am most certainly not in the cold climate in which I started, but in a warm country."

After a time I came to the conclusion that I was really in the middle of the earth, and not upon the surface; and, if so, what a discovery I had made! My reasons for thinking thus were as follows: When I started I descended rapidly, and when I came out of the hole it was equally swift; now, if I had travelled the number of hours I had at the same swift rate, I must have journeyed 3,000 miles at least; but, as I knew from what I had heard the captain say that the earth was 8,000 miles thick, I could not have gone half way, much less all the distance, through it. Then, again, I thought, how could that be possible? Our skipper says the world goes round; if it does the people on the inside, when they reach a certain point, would all tumble off, or be like flies on a ceiling; and yet I know they don't fall off on the outside, so why should they here?

As I so thought, I observed how much lighter it had got; and I again got out of bed to look round. Opening the window, I saw, right over my head, that the near side or edge of the dark ball looked like a new moon, only larger, and, so far as light was concerned, as brilliant as a like portion of the sun itself. I was astounded indeed, and could not take my eyes away, but stood and watched till they ached again with the glare of increasing light, and my neck felt as if I should never get it right, through holding my head so far back to have a good upward gaze. "Is it possible," I sighed, "that this is the dawn of day? Well, I see it, but I cannot understand it. I must not think too much, or my brain will become so muddled I shall not know what I am doing; and God knows I have need of all my reasoning faculties, so I had better submit to his will and leave things to explain themselves."

I NOW, as I lay, commenced to examine the furniture and general appearance of my apartment. It was but little different to what was to be seen every day in a nobleman's house in England, except that everything was most beautifully inlaid with metal of different colours. In some instances, wood was used with the metal, either for cheapness, as I then supposed, or for effect, there perhaps being no metal of the particular color required. The floor, ceiling, and walls were likewise most beautifully inlaid, and were really wonderfully done. Among other things, I noticed a circle of metals (apparently iron, brass, and copper), about three feet in diameter, let into the floor, just inside the door. Inside the circle there were some characters inserted of differently coloured metals, having much the appearance of shorthand. The ground colour of the floor was bright blue, the ceiling a pea green, and the walls a darker green. These colours I at first supposed to be paint, but afterwards discovered they were the natural colour of the wood. As I lay there looking about me, I supposed the building to be one of stone, lined with wood instead of plaster, but I afterwards discovered there was no stone used in its construction. It was built entirely of wood, as were all their houses, the timber being rendered fire-proof by being first soaked in some solution, but what I never found out.

Having taken a good survey of the room and furniture, I began to wonder how long I should lie there undisturbed. It was now broad daylight, and I could hear sounds as of people moving about; so, thinking I might be soon aroused, I once more got out of bed and began to dress myself.

Presently, and before I was quite dressed, there was a sound at my room door, and then it opened (not by hinges, but by sliding into the partition), and a man entered whose face and hands were of the same gorgeous colors as those I had seen the day before, and at whom (my mind being now more at ease) I took a long, searching gaze, though with some fear and wonder. His behavior I thought rather strange, for, upon entering, he stood fairly in the centre of the circle I have mentioned, and said something which I did not understand; then, swinging his arm round slowly in a circle, he stood very erect with his arms folded.

I answered him in this fashion: "Sir, I cannot understand your words, nor do I comprehend who or what you are, but if you can talk English, or can send someone to me who can, I have no doubt but we shall soon be able to understand each other."

At these words, he looked very straight into my eyes, and said something as unintelligible as before, finally making motions for me to follow him, which I did, after hastily finishing my dressing, feeling as one would feel if he were in doubt whether his conductor was a human being or a spectre. As I followed, I looked right and left, as well as at my conductor, but, with so hasty a glance, I could only see that the appearance of everything was grand and noble—everywhere inlaid with metals. We passed several men, like my conductor, in the halls and stairways, who looked very hard at me, and appeared as much surprised at me as I at them.

Presently, my guide pushed a door back, by sliding it into a partition, and, going just inside, spoke, making a circle in the air with his outstretched arm. I heard someone answer, but could not see who, because my conductor rather blocked up the doorway. After a few more words he stepped further into the room, and turning round, motioned me to enter. As I did so I heard a little pony give a loud neigh; and you can imagine my surprise to see a small horse, no larger than an Italian greyhound, seated in a lady's lap, its forefeet upon her knees, staring and neighing at me, just as a dog would stare and bark at a stranger. The lady looked at me with surprise and astonishment, and addressed some words to a gentleman of a very grave and dignified appearance, seated opposite her, and who was regarding me with looks that expressed both wonder and suspicion. These words he apparently answered; then motioned with his hands and spoke to my conductor, who thereupon placed a chair for me to sit upon in position about half way between the lady and gentleman. This I did without speaking, for I felt it was useless; but, if I could not speak, I could not help admiring the lady, although I scarcely liked to return their gaze, for I felt I was in the company of those who had a sort of a claim to scrutinise. Her remarkable beauty was, indeed, beyond comparison; and her face, neck, arms, and hands were of the most lovely and brilliant colours that can be imagined.

After a while the man whom I saw seated (and whom I afterwards found to be the King, or Sagerue as he is called) spoke to me, but of course I could not understand him, so I only shook my head. His Majesty, seeing it was useless to question me, forbore doing so, but spoke for some time with the lady—whom I found later to be the Queen—evidently about me, as I perceived by their glances. Presently, the door was again pushed back, and the same person—a servant, as I afterwards discovered—who conducted me into the King's presence entered and, standing in the centre of a circle such as I have before described, stretched out his right arm, with fingers all closed except the first, formed a circle by swinging his arm slowly round, then spoke some words, and stood erect with arms folded. I found that this was the manner of saluting in this country. The King arose, as did the Queen, who, taking the pony in her arms and advancing towards the door, motioned me to follow, which I did. I soon found myself in a dining-room, or, if you will, breakfast-room. [I may here explain that the highest mark of respect that could be shown a stranger was for the master of the house to go first, or lead the way.] In this room there was an excellent meal provided, but I could not distinguish any of the meat or drink: all was different from what I had been used to; yet it was delicious. While I was eating in silence and wonder, continually staring about me in a confused and stupid manner, bewildered with everything I saw, and above all with the surprising brilliancy of the colours upon the face, neck, and arms of the king and queen and the two servants in attendance, I noticed that his majesty often looked at me in the same stern and suspicious manner he did when I first saw him, which gave me great uneasiness, and added to my confusion, and I certainly should have felt very uncomfortable had it not been for the kindly looks I received from the queen, and my feeling that she was speaking to his majesty in my favour, though in what way I, of course, could not judge. After the meal was over, two more little ponies, about the size of English lap-dogs, came neighing and trotting into the room, started at seeing me, and then darted towards the queen, by whom they were in turn caressed. These, I learned, were the largest horses to be found in this country. They are only used as pets yet, strange to say, horse racing is a national sport—of course, these diminutive creatures run without riders.

While the Queen was petting these really beautiful little creatures, the King rose to leave the apartment. First approaching close to the Queen, he, in a pleasant, good tempered, yet meaning manner, drew the two first fingers of his right hand (which, by-the-bye, were of a beautiful crimson color) across the Queen's forehead. The Queen, rising, returned the salutation by drawing the two first fingers of her right hand across the Sagerue's brow. The latter thereupon advanced to the door, turned, and standing in the centre of the circle, stretched out his right arm, and with finger pointing, as I thought, at the Queen then at myself, said something, swung his arm around, and left the room. The Queen, I perceived, returned the last salute, but not in the same ceremonious manner. Of course, I did not understand the meaning of what they did, so only looked on with curiosity; but I felt certain at the time I ought to have taken some part in it, for I noticed that after the King was gone the Queen looked at me with contempt, and appeared to take no more notice of me, but to caress the ponies. While lost in reverie upon this subject, a servant entered the room, stood fair in the centre of the circle at the door, then slowly swung his arm around and motioned me to follow. This I did, first turning upon the circle on the floor towards the Queen, and moving my arm round as I had seen the king do. I omitted to draw my two fingers across her brow, for it had, by their looks, struck me that it was some sign of endearment; and I was most certainly right, for, although the forming of a circle with the right arm is a common salutation, not unmixed with religious ceremony, yet drawing the two fingers of the right hand across the brow is equivalent to kissing with us. [I afterwards discovered a still further action of expressing love, which was, to smooth the hair with the right hand; but this is only done when there is supposed to be no witnesses, and a pair of lovers caught so amusing themselves causes as much smiling and side-winks as it would in England if two lovers were caught with their arms around each others' neck and kissing.] The Queen returned my salute, looking both pleased and surprised, but not quite in the same manner as she did the king's, and yet I can hardly tell wherein lay the difference; but a difference there certainly was—much the same, I suppose, as there would be in England between warm friends and mere acquaintances bidding each other adieu: they may use the same words, yet there would be a difference in their expression.

I followed my guide, who motioned me to do so, passing through several apartments and up a grand staircase. We came to a closed door, where my conductor paused and listened. I looked about me: walls, ceilings, and, turn which way I would, everything seemed ornamented by metals let into the wood in thousands of different forms and figures. No matter whether it was flowers, birds, beasts, or landscape, all was done with different colored metals; and there appeared to be some of every color. [I discovered later that these ingenious people knew how to color white metal, such as silver or tin, any tint they may desire, so that really there were not so many different metals as there were different colors; but one thing must not be forgotten: they could not change the natural color of any metals; it was only white ones they could color.] My guide now made me some signs, by which I afterwards discovered, he was instructing me how to behave when in the presence of those I was about to see. I did not comprehend that I was about to be brought before the Sagerue's ministers, spiritual and temporal; nor was I aware of the state of excitement my arrival had thrown the whole government into. The truth is, I was too much astounded at all I saw, and the strangeness of my situation, to comprehend anything clearly. As the door slid back, a novel and strange eight met my gaze. I entered the room, it is true, but was so bewildered that I didn't know what I said or did. I forgot, or did not see, the circle at my feet. I remember seeing each person present describe with his arm a small circle and point his finger at me, but beyond that I could comprehend nothing. What confused me most was the smallness of the stature of those I now saw. I had seen giants at least thirty feet high, and men of my own size, but of those before me the tallest (except the Sagerue, who was present) was not more than four feet high, and the shortest scarcely three.

I should most certainly have taken them for children, if it had not been for the look of old age they had about them. The colours on their faces were dull, and very much faded. As soon as I was in the centre of the room, they drew their seats around me till I found myself in the centre of a circle, with a low stool placed for me to sit upon. After a short pause, the Sagerue spoke to one of the dignitaries, who replied, and then rising, I thought with difficulty, addressed me. Of course I could not understand him; nevertheless, seeing that he paused as if for me to reply, I arose, and, as near as I can remember, thus addressed them_:—_"My Lords, I cannot comprehend your language, who or what you are, or where I am. All I can say is, I am a poor sailor, brought here by accident or fate, but how I got here I don't know. I am an Englishman, and I don't think you understand me any more than I do you, so it's of no avail talking; but if you can tell me whether I am inside the world or outside, I should take it as a favour, for I am bothered if I can tell." I then sat down.

While I was speaking I noticed they paid the greatest attention to what I said, but they evidently could not make anything of it. They then talked for some time among themselves, and the result of their deliberations, as I learned later, was:—First: I was to be kept a prisoner, till such time as they could understand who and what I was. Second: Twelve young men should be brought into my presence daily to learn my language, and so discover all about me; and, as soon as that was done, another consultation should be held, and a decision arrived at as to my future treatment.

After this the assembly broke up, and my guide motioned me to follow him; but I must not forget to mention the ceremony observed by those present on leaving the room. It appeared to me at the time, although I was confused, that there was a peculiarity in their proceedings, of which I shall speak more fully presently: I am now only noting things as they appeared to me at the time, and the impression they then produced. I noticed that the tallest (except the Sagerue) arose first, and walked slowly up to the circle that was close to the door; standing in the centre of this, he turned and, looking at the Sagerue, stretched out his right arm, and, with his first finger pointing, swung it round in as large a circle as he conveniently could.

This action was repeated by the Sagerue, with a smaller circle, and without rising from his seat. The party at the door then looked at each one present in turn, and formed the circle, but, as I then thought and afterwards proved, in different sizes, and each returned the compliment; and so on, till all had gone except the Sagerue, who stood upon the circle at the door, and went through the same ceremony towards me, but with only a small circle. Now, not being a blockhead by nature, or very slow to learn, I comprehended something of what I saw, and did as the others did, and to the Sagerue swung my arm round in the largest circle I was able, which was larger than any of those preceding, by reason of my stature exceeding theirs, and, as a consequence, my arms being longer. I observed this pleased the king, not so much by any change in his countenance as by the expression in his eyes, for it really is a fact that these people express all emotion with the eyes. Love, anger, fear, revenge, or indifference, are expressed with the eyes only; this, I suppose, is caused by the brilliant colours of their skins not allowing their feelings to be visible as with us. Be that as it may, their eyes express everything.

Strange to say, after several months residence with them I could judge their thoughts less, by their eyes, at the end of that time than I could at first; nor was this all, for after a time their voices seemed to lose the musical ring they appeared to have when I first heard them speak. A dozen speaking together, each one in a different key, more resembled glee singing than aught else; but in time I got so used to it that I did not notice it half so much as at first.

In a few minutes after the assembly broke up I found myself in another part of the palace, confined to a suite of three rooms and one or two small offices. While being conducted to these rooms I passed an open door, through which I caught a glance of a lady standing on her head, or trying to do so, but the door was closed so quickly by another lady that I had scarcely time to make sure of what she was doing, but I saw my guide's eyes express contempt (if I understood them rightly) at the sight.

And now, as I am what may be called a state prisoner, let me describe my apartments. The walls were of blue wood, and inlaid with metals of crimson, gold, and white, as the principal colors. The ceiling of one room was white, inlaid with gold; of another gold and white. The floor of one room was black and white, like a checker board, and to the threshold of every door there was a circle of about three feet in diameter. In many respects the furniture differed but little from English household goods, in fact, some might have been taken for old fashioned English, others for a new style. The windows were of glass; there were several looking glasses, but I saw no china, all drinking cups being of metal or glass, except those used by the giants, of which anon.