RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"THUNDER WEATHER"

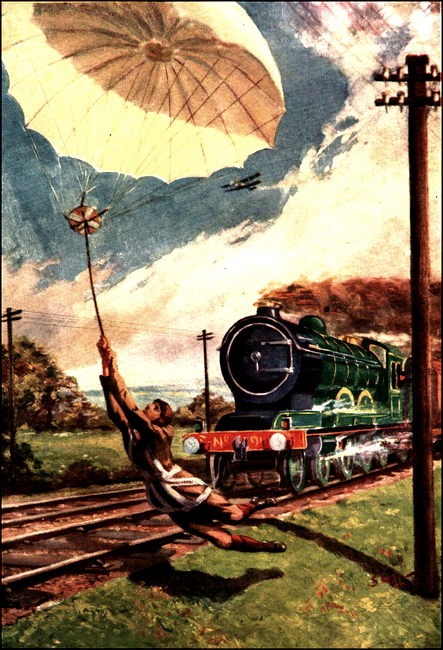

A strong gust caught the parachute and the next instant

Roger was

between the lines and right in the path of the approaching train.

IN spite of the heavy storm overnight, the air was still hot and sultry as Roger Selby started for the bank. He always walked. It was the only exercise be could get, for he was now working twelve and sometimes fourteen hours out of the twenty-four.

The bank, a small private one which belonged to his father, had suffered badly during the war, and the staff had been cut to only five, including his father and himself. And now that Mr. Selby was laid up with a bad nervous breakdown, Roger had to do his father's work as well as his own. Indeed, he and Whipple, the cashier, were practically running the whole business.

The Glen House, where the Selbys lived, was two miles by road out of the little town of Braxton, but Roger always took a short cut, a path leading down by the brook which divided the Merton Hall land from that of Melbourne Farm.

Going down the high-hedged lane leading to the brook Roger suddenly beard a voice.

"Drop her, man. Drop her. Let her go, I tell you!"

"Drop her, indeed! I think I see myself, now I got the poaching young wretch," came the answer. This voice Roger knew. It was that of Couley, who was keeper to Squire Stourton, of Merton Hall. It was hard to say whether keeper or master had the worse name in the neighbourhood. Both were pretty thoroughly hated.

"Poacher! Don't be a fool," said the first speaker again. "Can't you see she's only a puppy?"

There came the pitiful scream of a dog ill-handled and a cry of distress from its owner. "You brute! You rotter! If I could only get at you!"

Roger broke into a run. As he rounded the corner, the first thing he saw was the heavy set figure of Couley. In one great fist he cruelly grasped the limp little shape of a small rough-haired fox terrier puppy. The little thing was not more than six months old. In the other hand the fellow had a heavy dog whip with which he had cut the puppy so brutally that blood stained its white coat.

Opposite, on the other side of the brook, was the dog's owner, a young fellow of no more than twenty-three or four. One glance was enough to show Roger the reason why he could not interfere. He was on crutches. One leg was missing, cut off above the knee.

Like all decent men, Roger loved dogs, and the sight of Couley's brutality made every drop of blood in his body boil. One jump, and he was across the brook, and charging straight at the keeper. Couley had barely time to drop the puppy before Roger reached him.

"What are you a-doing of?" bellowed Couley, and struck at Roger with the whip. Roger caught the blow on his light forearm, and his left fist, driven with every ounce of strength he possessed, took Couley fair and square between the eyes.

Couley staggered buck, caught his heel on a mole-hill, and went down. As it happened, just behind him the brook bank curved inwards, and had been deeply undercut by a strong eddy. Couley's weight proved too much for the overhang, which broke away, and down the man went, with a tremendous souse, into the muddy current of the swollen brook.

"Topping! Oh. topping!" cried the man opposite in an ecstasy of delight. But next instant he had pulled himself together. "Pick up the puppy, sir, and come over this side," he said quite quietly.

Roger did so, and as he handed the poor, shivering little creature to her owner, Couley heaved himself, dripping, out of the tail of the pool. His nose was bleeding freely, and his hat was gone.

"I'll 'ave the law of you for this!" he roared, shaking his great fist at Roger. "I'll ruin you for this, Roger Selby. I'll see you in prison, you and that popinjay Palliser."

Roger did not answer. He was beginning to feel rather unhappy. Couley's master, the squire, was a power in the neighbourhood. But Palliser, if that was his name, faced the keeper.

"You brute!" he said with bitter emphasis. "If you dare to say another word I'll show you something about prison. I'll get Martin House down. He's a friend of mine, and you know what happens when he starts on a case of cruelty to animals. And it isn't the first time either. I could collect evidence which would send you up for two years' hard. You dirty bully, you've got exactly what you've been needing for a long time past, and if you or your precious master ever dare to interfere with my friend here or myself, I know who will be ruined."

Palliser never raised his voice in the slightest, but he spoke with such intensity that Couley collapsed like a pricked bladder, He clambered out of the brook, and without another word went dripping away across the field.

Palliser stretched a hand to Roger. "I'll never forget this so long as I live," he said. "Will you come up to the house with me? I've taken Melbourne Farm."

Roger had to explain that this was impossible but promised to visit Palliser one evening. Then he hurried on to the bank.

Naturally he was a bit late, and he was the more surprised to find that Whipple, the cashier, had not yet arrived. "Seen anything of Whipple, Peale?" he asked of the closer of the two young clerks.

"No, Mr. Roger," was the answer, "and no message from him, either."

"I only hope he isn't ill," said Roger. "With my father away, we've got more than we can do as it is."

As Roger spoke, he look the key of the big safe from the locked drawer where it was kept, and going down into the strong-room, unlocked the safe.

The moment he opened it, he saw that something was wrong, and his fingers shook as he hastily took out piles of papers and ran through them. It was not a minute before he discovered that the most important and valuable parcel of all was gone. It was a bundle of securities which had been deposited on the previous day by Mr. Beeman, a large farmer in the neighbourhood, and the bank's best client.

Their value was over seven thousand pounds, and they were "Bonds to Bearer"—that is to say. they could be cashed as easily as bank notes.

Cold chills ran down Roger's spine. The loss meant absolute ruin, both to himself, his father and the bank.

For a moment, the dark little place swam before his eyes. Then with a great effort he pulled himself together, and closing the safe, came out of the strong-room, locking it behind him.

"Peale, will you and Curzon carry on?" he said. "I'll just run down the street and see if Mr. Whipple is ill."

Before he rang the bell at Whipple's lodgings, Roger felt that he knew what he would hear. He was right.

"Mr. Whipple left early, sir," said the old Judy, with an air of surprise. "He told me that he had orders from the bank to go to London."

"I'd forgotten," said Roger with a quietness which surprised himself. "Of course. Sorry to have troubled you, Mrs. Whislow."

It was to the polite station that he hurried next. There was only one policeman, and of course he was away on his rounds.

Sick with anxiety, Roger made for the railway station.

"Mr. Whipple?" said Walcot, the station, master. "No, he didn't take the London train, sir. He left by the 8.40 for Hull."

Roger could not suppress a groan.

"Anything wrong, sir?" asked Walcot.

"Yes, very seriously wrong," replied Roger. "I will tell you if you will give me your word not to repeat it."

Walcot, a steady going north-countryman, gave the required promise, and Roger told him his suspicions.

Walcot shook his grizzled head. "A bad job, sir. He's got a long start. That's a fast train, and is due in Hull soon after twelve."

"Not till twelve," said Roger quickly. "Then we can wire to have the police meet him at the terminus."

Walcot shook his head. "That's just what you can't do, sir. Last night's storm has brought down the wires. We can't get through either way."

Roger gave a gasp of despair. "Then we're done for," he said.

"What's the matter?" came a voice from behind him, and wheeling quickly, there was Palliser standing, supported by his crutches.

"Forgive my butting in," he said quickly. "I came to the office to fetch a parcel. It was quite by chance I stumbled in on you like this"

Roger stared at him blankly.

"I'm awfully sorry," said the other, and was turning to hobble away when Roger slopped him.

"You may just as well know," he said harshly, "Everyone in the place will know in the course of the day. Our cashier has bolted with seven thousand pounds' worth of securities, and we are ruined."

"Where has he gone?" Palliser's thin face was suddenly alive.

"Taken the 8.40 train to Hull. The wires are down. There is no means of stopping him. Probably he knew that when he started."

"Hull! Where's a map?" snapped Palliser.

Walcot slapped a map down on the table and Palliser read it like one well accustomed to the job.

Then he looked at his wrist watch. "Not ten yet," he said. "I believe we can do it. Come on, Selby. My car's outside."

"Your car. We can't catch the express with a car, especially when the train has an hour's start," returned Roger in amazement.

Palliser stared. "Car! I wasn't thinking of a car. Oh, I forgot that I hadn't told you. I'm an old R.F.C. man, and if I can't walk I can still fly. I've got my old bus up at the place, and, thanks be, she's in good order."

"You mean you are going to fly after the train?" exclaimed Roger.

"Yes, and you, too. It's the only way to catch her, so far us I know."

Living in this remote country town, Roger had never seen a plane except in flight. As in a dream, he found himself hastily donning a suit of Palliser's flying kit.

Then he was in the seat of the biplane, and Mostyn, Palliser's man, was spinning the tractor. With a deafening roar, the engine broke into life, and the machine went trundling away across the broad meadow. The ground was wet with last night's rain, and she was slow in taking off. But Palliser got her neatly up over the tall hedge, and Roger, sitting very still, saw the earth dropping away beneath them.

THE first thing Roger was conscious of was the roar of wind past his ears and the welcome coolness. The heat on the ground had been intense, and the change was simply startling. Very soon he was grateful for the heavy belted coat and the close-fitting pilot's cap.

Palliser got his height, and wheeled. He pointed with one hand, and looking down, Roger saw the town. like a collection of toys far below, and the railway, a glistening strip running straight eastwards.

At first he felt half dared, but. presently the sense of speed seized him, and for the first time since his discovery of the robbery a gleam of hope touched his despairing soul.

The machine herself was rather old fashioned, but there was nothing the matter with her engine. Presently Palliser pointed to a dial in front, a sort of speedometer. "Seventy-three," he shouted in Roger's ear. "Not so dusty!"

Silence for a while. Roger had got over his first natural nervousness, and but for his intense anxiety could have actually enjoyed his first flight. He looked out over the enormous stretch of country beneath, then glanced up at the sky above.

Palliser, too, was looking at the sky, and presently he pointed again. To the north the intense blue was blotched with a mass of blackness.

Roger nodded. "Another thunderstorm," he muttered to himself. He noticed a rather anxious expression on Palliser's lean, brown face and wondered at it. Then he ceased to think of anything except the possibility of capturing Whipple.

Palliser was speaking again. "Did Mr. Whipple book for Hull?"

"Yes."

"Then take it from me, that's not where he's gone."

Roger gasped. Now that Palliser had said it, he felt sure that he was right.

What's that junction down there?" inquired Palliser.

"Wroxeter."

"Does the 9.50 stop there?"

"Yes, it waits for the Liverpool express."

"I'll bet he changed into that."

"We can't be sure," said Roger in dreadful perplexity.

"Well, he didn't go to Hull, I'll vow! and Liverpool would be the very place for him. Lots of ships. Make up your mind," said Palliser a little impatiently. "There's no time to waste."

"I'll be guided by you," replied Roger.

"Right! Then we chivy the Liverpool train. If we miss him we can always wire to Hull and send his description."

The plane made a half turn. Instead of south-east they were flying south-west. Roger, glancing at the sky again, realized that the cloud was bigger and nearer.

The minutes passed, and suddenly Palliser shouted and pointed.

Roger looked, and saw, miles ahead, a train which seemed to crawl across the little squares that were fields. His heart beat hard.

"Yes, that must be our train," he said in answer to Palliser's unspoken question. And almost as the words left his lips, the sun vanished. The edge of the great cloud had been drawn over it like a curtain.

Palliser leaned back. "We're in for trouble," he said curtly.

"What the goodness do yon mean?" asked Roger. "I thought a plane could run away from a storm, or rise above it,"

"Yes, but what about the train, meanwhile? We should lose it completely."

Roger looked at the train. From the great height at which they were flying he could easily see the Mersey, and the sea beyond it.

"The storm is not on us," he said. "Can't you get ahead of the train, and drop somewhere in front of it?"

"No time, my dear fellow," answered Palliser. "It's true I could probably beat the storm to the train, but the storm is bound to get us before I can plane down, and to attempt to land in the sort of buster that's coming would certainly mean a crash. You see, I don't even know the ground, and when the rain strikes us I shan't be able to see it."

Roger almost wrung his hands. He was in despair. "Is there no way out of it?" he asked.

Palliser looked at him. "If you could handle the plane there would be—but you can't, it's no use talking of it."

"What do you mean?" demanded Roger.

"I'd use a parachute. I've got one aboard."

"You mean you'd drop from the plane?"

"Yes."

Roger's lips tightened. "Let me," he said. "I'll do it."

"You, Selby! You don't know what you're talking about."

"Perhaps I don't, but I'm game to try it. Man, I'd give my life to catch that scoundrel."

Palliser gave him one sharp glance. "Well, I've warned you," he said.

"You have. I take all responsibility from now on. And whatever happens, I shall always be grateful to you. Where's the parachute?"

Palliser showed him, and told him how to put the belt around him. By the time he had done this they had nearly caught the train. But the storm, coming up on the beam, was right on top of them. Already the low hills to the left were hidden by a grey veil of driving rain.

"There's a small station just ahead," said Palliser. "When we get over that, drop. I calculate you ought to reach the ground about a mile ahead of the train. Then make the station-master stop her."

"And see here," he added, "you'll drop like a bullet for the first hundred feet or so, but don't be scared. The parachute will open out all right. Look out for the wind taking you into a tree or building, and when you touch ground keep your legs well bent."

Roger nodded. Again he looked over. The plane had now passed the train. She was travelling twice as fast.

"Now!" snapped out Palliser, and Roger, with an inward prayer, leaped out into the void.

The first rush and plunge nearly took his breath, then came a slight jerk, and he saw the parachute opening above him like a huge umbrella. He found himself swaying downwards in a most delightful fashion. "Why, it's nothing!" he said to himself. "It's as easy as anything."

Away overhead he heard the roar of the aeroplane engine, but could not see it. He looked down. There was the train coming up at a tremendous pace. She was much closer than he had thought, then suddenly he saw that it was he, or rather the parachute, that was going back towards the train. Caught in the under draught of the storm, he was being carried eastwards again.

Another few seconds, and his heart was in his mouth for as he neared the earth he realized that he was dropping straight on to the permanent way, and that, unless some miracle occurred, he would fall either on the train, or on the line in front of it. He realized, too. that he was perfectly helpless, actually at the mercy of the wind.

The roar of the train grow louder. She was only a hundred yards away. Almost immediately below him were the black threads of the telegraph wires. If the wind would only drop him across there, it might still be all right.

A strong gust caught the parachute and sent Roger swaying like a pendulum. Next instant Roger was between the wires and right in the path of the approaching train.

A drop of rain, cold as ice, struck his face. In a flash the wind had changed right round, and the parachute was driving up the line instead of down. "What happened during the next few seconds Roger hardly knew. He was only conscious that he swung in a great arc of a circle, missing a telegraph post by a matter of a yard or two only. The train was almost on him. Her roar was deafening.

His feet struck gravel, and he found himself sprawling on hands and knees, while the parachute, swinging round in the gust, caught in the telegraph wires. He flung himself sideways just in time to avoid the rush of the thundering engine.

A blast of air struck him, he heard the grinding of wheels close to his ears, and was conscious that the train was rushing past.

Somehow he struggled to his feet, and unbuckling the belt around his waist, clambered to his feet. But the train was already past. He was too late!

Filled with a dreadful despair, he started to run. But now the storm was on him in earnest. The wind roared, the rain heat in torrents. He had lost sight of the train and of everything else beyond a radius of a few yards. A blinding blaze of lightning lit the gloom, there was a deafening crack of thunder, the earth seemed to spring up and strike him, and for the moment he knew no more.

"HE'S not touched. A little cut on his face, that's all."

The words roused Roger from his momentary insensibility, and he looked up to see a guard bending over him, and with him a quiet looking, middle-aged man in a dark overcoat. He looked like a doctor and it was he who had spoken.

"The train!" cried Roger, sitting up suddenly.

"What's the matter?" demanded the guard gruffly. "What made you do such an idiotic trick us to drop in front of us like that? We thought you were killed."

"Do you belong to the train? And has it stopped?" asked Roger, on his feet again.

"Yes. She's in Garth station this minute. Nice and late we shall be, too," growled the guard, evidently much upset.

"Thanks be!" cried Roger in intense relief. "Then perhaps I'm not too late after all," and standing there in the beating rain he quickly told the others his story.

"What was the man like?" demanded the doctor—"the defaulting cashier, I mean."

"Tall, thin, crooked nose, pale eyes, ginger hair," answered Roger sharply.

"There was a man of that description in my compartment, only his hair was black," said the doctor.

"A wig, most like," put in the guard. "Let's go and see. The young gent can identify him."

But when they reached the train the doctor's carriage was empty.

Roger rushed across to the station master. "Has anyone got out?" he demanded.

"Not that I've seen," was the answer.

"He may have slipped along into another compartment," said the guard.

"Here's his bag," announced the doctor suddenly. "It's still in the rack."

The news was all up and down the train. Heads were sticking out of carriages. The excitement was tremendous. The guard and other officials were searching every compartment for the train was a corridor one.

There was no result. Whipple seemed to have vanished completely.

"We can't hold up the train any longer," said the guard uneasily. "Young gent, you'd best come with us to Liverpool, and the station-master here will wire the police to meet the train."

There was nothing else for it, and Roger, with a heart like lead, got into the train with the doctor.

The train moved on.

"I'd best look in the bag, and make sure that it is Whipple's," he said.

The doctor agreed, and with a little trouble they forced the lock.

"It's Whipple's all right," said Roger. "Here's his initials H. L. W. on a collar."

"Then where the mischief could he have gone?" said the doctor, frowning.

At that moment the whistle screeched and the brakes were flung on so sharply that Roger was almost jerked from his seat. He dropped the bag, and some of its contents rolled on the floor.

"It's all right," said the doctor, with his head out of the window. "Only the junction. We were rather too close to another train. Comes of being late. Hallo—dropped the bag?"

He stooped to help pick up the things.

Next moment he and Roger both gave a shout, for both at the same moment had seen a long lanky figure concealed under the seat.

"Whipple!" cried Roger, and catching hold of the man, dragged him roughly out.

"You blackguard," he said, "give up the money."

Whipple, shivering like a beaten dog, took a packet out of his inner pocket, and handed it over.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.