RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a detail from a public domain walpaper

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a detail from a public domain walpaper

Tom tried to leap aside, but the other was too quick for him.

THE dingy old jaunting-car pulled up suddenly, and Tom Dane stared in amazement at the huge pile of grey, weather-beaten masonry which towered above him.

"Is this your place, Myles?" he asked in a startled voice.

"Yes, Tom, it is our show," replied Myles O'Hara, with a smile on his thin, brown face.

"But it's a castle!" exclaimed Tom, still gazing up at the vast square tower which rose high against the windy evening sky.

"It was once," said Myles, rather sadly. "Out you get, Tom, and collar your things. Here's Moriarty. He'll take the horse."

An elderly Irishman, with a long upper lip and a pair of deep-set and rather cunning eyes, came out as he spoke.

"Father in, Moriarty?" asked Myles.

"He is within, sorr," replied the man briefly, as he went to the horse's head.

The boys took Tom Dane's things, and Myles led the way into a huge, bare, echoing hall, where Mr. O'Hara met them and greeted Tom kindly.

"I'm glad to see my boy's friend," he said to Tom as he shook hands. "Slayne House is not what it used to be, Dane, and it's little in the way of comforts we can offer you. But we'll do what we can, and hope you'll stay as long as possible. It's not much company we have these days, and it's dull for Myles.

"Take Dane up to his room, Myles," he said. "Supper will be ready by the time he's down."

"I told you we were hard up, Tom," said Myles, as he led his friend into an immense bedroom on the first floor; "but I'm afraid you didn't realise that we were absolute paupers. We haven't a servant except Moriarty. We can't afford it; and even if we could it's—it's doubtful if they'd stay in a place like this."

"Don't worry, old chap," replied Tom. "I love it, and I'm going to have a topping time."

All the same, when bedtime came Tom did not feel quite so sure. There was an air of gloom about the huge, bare old place which depressed him badly. Mr. O'Hara, though as kind as he could be, was dreadfully silent. Myles said very little, and as for Moriarty, he seemed to be always listening.

He was quite glad to get to bed, but even then he lay awake in his huge old four-poster, listening to the waves which boomed at the foot of the cliffs below Slayne House, and half wishing that he had not come.

Mr. O'Hara, so Myles had told him, was a nephew of the late owner of Slayne, and when he had inherited the place had found the property in a shocking state. Old Terence O'Hara had neglected it for years, and seemed to have spent all the family money. The great lonely house was in such bad repair that it was impossible to let it. The O'Haras could not afford to do it up. There was nothing for it but to go and live there and do their best to nurse it slowly back. A hopeless task, so Tom thought.

At last Tom managed to get off to sleep; but it seemed to him that he had hardly closed his eyes before he found himself sitting straight up in bed.

It was a scream that had roused him—a scream so weird, piercing and terrible that it chilled the blood in his veins and made his very skin crawl.

In a flash he was out and had darted across into Myles's room.

"What is it, Myles? Who has been murdered?"

Myles was sitting up.

"Don't worry, Tom," he said. "It's only the banshee."

"The banshee!"

"Yes. I ought to have told you, only I hoped perhaps you wouldn't hear it. Just the family ghost, you know."

Tom could hardly believe his ears.

"A ghost make that awful sound?"

"Yes," said Myles quietly. "If you'd lived here as long as I, Tom, you'd be accustomed to it. Now, don't worry. The thing, whatever it is, doesn't hurt us. So just go quietly back to bed and to sleep."

Tom went back to bed, but not to sleep. He would dearly like to have cleared out at once. But when the morning dawned, with a glorious sun and a cloudless sky, he felt better; and when Myles appeared with bathing towels and took him down to bathe on a strip of white sand below the tall cliffs, he forgot his scare.

After breakfast they took a boat and went fishing. They anchored off some rocks a little way out, and began to pull up whacking great pollack of ten or twelve pounds apiece.

It was nearly four when they started to pull in. Tom was looking up at the gigantic mass of granite cliffs which faced the sea, when Myles heard him give a quick exclamation.

"See that?"

"No. What?"

"There was a man looking at us out of the face of the cliff."

"Nonsense, Tom!"

"There was. I swear there was. I saw his head as plainly as I can see you. An ugly-looking chap, with a long, thin face and hair as white as snow."

"But no one can climb those cliffs," Myles argued.

"Can't help that," said Tom. "I saw him. There was the place, just where that ledge sticks out, directly below the house."

Myles looked troubled.

"Don't say anything to dad. We'll have a look round later," he said.

After tea they both went to the cliff edge and hunted round. But except the path leading down to the cove, there was not a spot where any human being could have got down without ropes.

"You must have imagined it, Tom," said Myles at last.

But Tom shook his head doggedly. He was convinced that he was right, and he vowed that he would get to the bottom of the mystery some way or another.

That night he went up to bed as usual, but he did not undress. He put out his candle and waited. The tall grandfather clock in the hall below struck eleven, and twelve. Tom was getting desperately sleepy, when all of a sudden there came echoing through the great bare house the same terrible scream that he had heard on the previous night.

It was a dreadful sound, keeping on and on like the hoot of a siren. He ran to the open window and heard it echoing along the lonely cliffs. The whole air was full of it, and, in spite of what Myles had said, he found himself shivering with sheer fright.

But there was sterling stuff in Tom Dane, and he had vowed to himself to probe the mystery. He picked up his little electric torch from the dressing-table and went straight downstairs.

The darkness was intense, and the silence, after the hideous sounds he had just heard, was like that of a vault. The air struck chill and damp. It was all that Tom could do to keep moving forward. He had a wild desire to bolt back to his room and lock himself in there until daylight.

He reached the hall and stood quite still, listening. Not a sound, except the faint roar of the waves at the base of the tall cliff on which the house was built.

His courage began to ooze away, and he was on the point of clearing out and scuttling upstairs again when he distinctly heard a door open and close.

Now, ghosts may scream, but they do not open and shut doors. Tom's fears vanished, and he went quickly forward across the hall. He moved on tiptoe, silent as a cat, and reached the big green baize door which led to the back regions.

He opened it softly and listened again.

Ah! someone was moving.

Tom switched off his light, slipped through the door, then set himself to follow the sounds. There was a window facing the sea in the passage wall, and light enough came through it for Tom to find his way. The steps were dying out in the distance as he started, but next moment another door opened. The hinges creaked, and the sound gave Tom a chance to dart forward unheard.

He was in time to hear the door close again, and next moment was standing close by it, his ear against it, listening for all he was worth.

Yes, there were the steps again. He could hear them clinking away steadily. He waited a moment, then very cautiously turned the handle. He opened the door just enough to slip through, but not enough to allow the hinges to creak, and found himself standing in a gulf of blackness, faintly illuminated by the light of a tallow candle which glimmered faintly in the depths below. He realised that he was standing at the head of a flight of stone stairs which led down into a deep cellar lying beneath Slayne House.

There was no time to wonder who the man was or what he was after. Tom hurried after him as quickly as he dared.

He reached the bottom of the steps just in time to see the light vanish at some distance to the left, and as he could now see nothing he was forced to switch on his own light.

This showed him that he was in a cellar with a rock floor, and not a thing in it but the remains of some broken wine bins. It showed, too, a passage leading out on the left. The midnight prowler had passed that way, and it was up to Tom to follow.

Before he reached the doorway he turned his light off again. There was no need to use it, for there in the centre of a second cellar stood Moriarty. His candle he had laid on the floor, and he was busy heaving up a heavy stone trap-door.

Tom's heart began to beat fast. What was up he had no idea; but every treasure story he had ever read seemed to come rushing back into his mind. The ghost, too, the banshee, as Myles had called it, and also the face on the cliff, all these things flashed through his brain like cinema pictures.

The big flag, once started, rose easily enough. There must have been some hidden machinery which did the trick. Then Moriarty picked up his candle, and also a small parcel which lay beside it, and turning round, began to go backwards into the opening.

Tom waited a few moments, then hurried cautiously across. Moriarty's light was still visible in the depths below. It flickered in the cool salt draught which blew up from some unseen source.

It was a heavy wooden ladder which Moriarty was descending. Tom waited till the man had reached the bottom, and saw him stand listening for a few moments, then move off cautiously.

Giving him just enough law to be safe, Tom went pattering in pursuit like a lamp-lighter, but by the time he had reached the bottom Moriarty was out of sight again.

Tom ventured to flash his light. He stared around. This time it was a huge cave in which he found himself, a cave with a vaulted rock roof, but a floor which must have been levelled by hand. All around were casks and puncheons, little and big. They were black with age, and some of them had burst open, and from their ruins sprouted great ghostly white fungi. There was a curious smell in the place which mounted to Tom's head and made him feel half stupid.

He looked all round, wondering where Moriarty had gone. There was no sign of the man, and for the life of him Tom could not imagine what he was after or where he had gone. He waited a little, then began to walk slowly down between the great tiers of casks.

He had not gone ten steps before he heard the scream again. If it had been bad up above, here it was twenty times worse. The thick air vibrated with the hideous sound. It shrilled through his head, almost deafening him with its horrible clamour. The very blood seemed to freeze in his veins, and he stood with his knees shaking, unable even to fly.

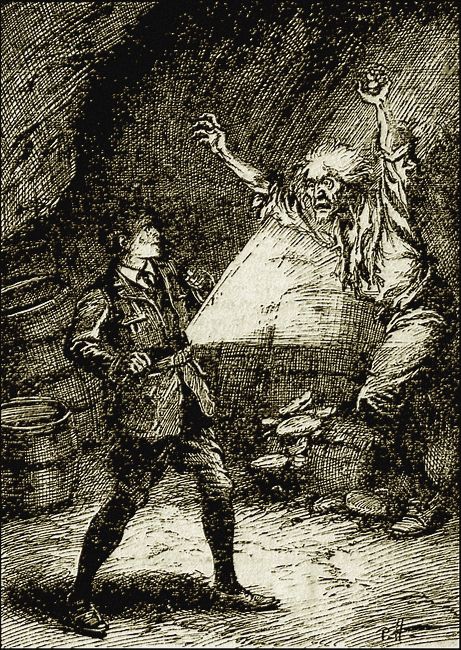

The sound died, but the last echoes were still quivering in the hollow depths of the great cave when something else happened. With a growl like that of a wild beast, a man rose from some hidden place among the casks and came rushing upon Tom.

Tom's torch showed a long, lean, ragged frame, a dead white face with gleaming eyes, and a shock of hair white as fleece. He tried to leap aside, but the other was too quick for him, and next moment two claw-like hands seized him and flung him to the floor. His torch flew out of his hand, but by a curious chance fell upon a broken cask, and was not broken or extinguished.

"Moriarty!" shrieked Tom. "Help!"

Then he was flat on the hard rock, with the other on top of him, tearing at him and making a hideous, panting, growling sound, just as a cat does when worrying a mouse.

To Tom it was like a nightmare, too horrible to be real. He fought for all he was worth, but knew all the time that it was useless.

The man kept clutching at his throat, but Tom, by kicking and hitting out desperately, managed to prevent his getting a hold. The creature's nails were like talons. Tom's clothes were ripped from him as though by the claws of a gorilla.

"Help!" he shouted again, but only echoes answered. The man himself never said a word. He only kept up that detestable growling, worrying sound. The smell of him, too, was sickening. It was like that of an uncleaned kennel.

Tom's strength began to fail. He kicked out once more with all his force, and felt his toe grate against the other's shin. The pain, roused the creature to a paroxysm of fury. He gave a thin shriek, and forcing Tom back, clutched him with his right hand by the throat, while the other he raised above him, clearly meaning to strike him full in the face.

There was a rapid thud of bare feet, the sound of quick breathing. Then a small white figure came flying through the air, to land all in a heap on the madman's shoulders.

Tom felt a great weight across his body but at the same time the grip on his throat relaxed.

"Hurrah for you, Myles!" he gasped feebly. Then everything spun before his eyes and all grew suddenly dark.

Cold water trickling down his face was the next thing Tom was conscious of, and opening his eyes, he saw Myles bending over him with a very anxious expression. He had a big bath sponge in his hand. He himself was on a sofa in the hall.

"All right, old chap," he said hoarsely. "You needn't drown me."

Myles gave a sigh of relief.

"I thought you were done for, Tom," he said.

"I jolly well should have been if you hadn't turned up. The beggar was choking the soul out of me. I say, Myles, I was right, after all. That was the chap I saw looking down from the cliff when we were pulling in.

"I suppose it was. It's a queer business, Tom."

"Queer! I should think it was. Who is the chap?"

"Who was he, you should say, Tom," replied Myles gravely.

"Do you mean he's dead?"

"Yes. He burst a blood vessel and was dead in five minutes."

Tom was silent for some moments.

"Poor brute!" he muttered. "But you haven't told me who he was, Myles. Have you found out?"

"Yes. Moriarty has owned up. He was Terence O'Hara, my old uncle's younger brother. He'd been off his head for years, and living down in those caves all the time. No wonder he'd gone white. We thought he had died years ago."

Myles paused a moment.

"Moriarty has owned up," he went on. "It was he and another chap who kept him down there. The other man's name is O'Flaherty. He and Moriarty ran a moon-shining business, and did it down in the caves. They were smuggling in spirits, too. They kept him there to act as a sort of guardian of the caves. Everyone round here thought he was a ghost—the banshee, you know."

"By Jove! What a scheme!" exclaimed Tom.

"It was pretty smart. And they had all my uncle's wines and liquors down there too. Father has been looking round. He says there must be five or six thousands pounds' worth of old brandy and wine alone."

Tom gave a feeble cheer.

"Topping! That'll do you a bit of good, Myles."

"It's a perfect godsend," agreed Myles.

Again there was silence for a moment or two. Then Tom spoke again.

"But the scream, Myles. How did they manage that?"

"Quite simple. It was nothing but a siren which they'd got off an old motor-car. They worked it by an air pump."

Tom laughed outright.

"Well, I'm hanged! It sounded awful."

"It did. That was the echoes, I fancy. I say, Tom, are you fit to come up to bed?"

"Rather, and to sleep, too. And to-morrow we'll jolly well explore the caves, won't we?"

"We will," agreed Myles.

They did; and it was not five thousand pounds' worth of stuff they found, but nearly double that value. There was brandy there a hundred years old, which fetched, when sold, three and four pounds a bottle.

As for Moriarty, they never saw him again. After his confession he slipped away, and, it is believed, went to America.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.