RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

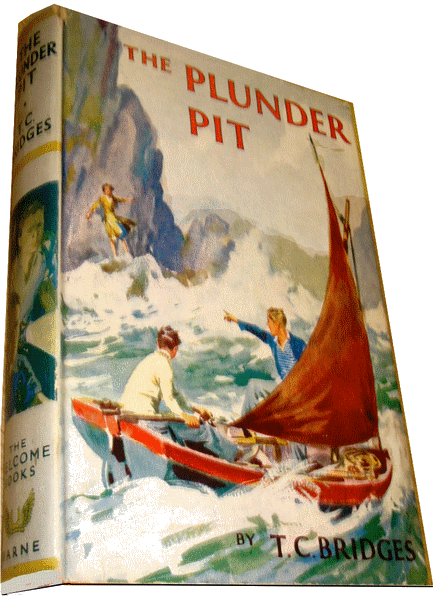

"The Plunder Pit," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1937

A FAINT rumble of sound boomed through the hot, sunny air. Out to the north-west, in the direction of the Welsh coast, a dark cloud shadowed the sea, end from time to time a pale flash blinked in its heart. Jim Coryton hastily knocked out his pipe on the gunwale of the boat, and began to haul in his line.

'Wake up, Pip,' he said. 'There's a storm coming.'

No reply. Peter Paget, his plump legs stretched straight out, his bead propped comfortably against a couple of cushions, slumbered peacefully. Jim picked up the boat hook and prodded him gently, and Pip opened round blue eyes and gazed at his friend.

'What's up?' he inquired sleepily.

Jim laughed. '"But it often appeared when the gale had cleared, that he'd been in the bunk below,"' he quoted.

Pip gave him a sorrowful look, mumbled something about letting 'a chap sleep, damn you!' and once more closed his eyes. But just then the thunder spoke again, and this time with no uncertain voice. Pip sat up with a start, and one glance at the ominous black cloud cleared every trace of sleep from his eyes.

'Gosh,' he said, 'it's going to be a buster. Get up the anchor, Jim. We've got to shift, and sharp about it.'

The little kedge was rather badly caught among the rocks at the bottom, and by the time Jim had freed it and got it up, the whole sky to the north-west was covered with a purple pall, and the thunder boomed incessantly.

'Not a breath of wind,' said Pip sharply. 'Jim, we'll have to pull for it.'

'Back home?' questioned Jim, doubtfully.

'Great Scott, no! We must get to land as quickly as ever we can. There's wind there, when it does come.'

'But, my good Pip, we cant land on those infernal cliffs,' remonstrated Jim, glancing at the grim granite rocks of the Cornish coast.

'There's a small cove just north of that point,' Pip told him. 'I've never been into it, but I know a stream runs out there. We can find some sort of shelter, and wait till this blows over. Pull, man! We haven't got much time.'

Jim merely nodded. He had complete faith in Pip, who, as he was aware, knew the whole of this coast, from Bude to Newquay, as well as any, professional fisherman. He set to pulling vigorously and the stout little dinghy went surging across the calm water towards the land. But it was not going to be calm very long, for already Jim could see a line of white foam along the surface. Pip saw it, too.

'I'll set the sail on her,' he said. 'Keep her moving.'

Short and stout as he was, Pip could handle a boat with any man, and the speed with which he got the sail up and tied down the reef points was worth watching. As he finished, the great arch of cloud swept over the sun, wiping, out its bright light. Then with a roar the wind was on them.

'Sit tight,' Pip cried, as he took the tiller, and the little boat heeled and went racing through the short steep waves. Jim was not at all worried, for he had complete confidence in Pip. He obeyed orders, and sat tight while Pip headed for tho point of rock.

A brilliant flash lit the gloom, followed by an ear-splitting crack, then down came the vain with tropical fury, drenching them both to the skin.

'Shan't be long at this rate,' bawled Pip, as the wind heeled them far over, and the water hissed whitely along the lee gunwale. 'I only hope the channel's clear.'

'I'll watch for rocks,' Jim answered, and after that neither spoke until they were almost level with the great crag which marked the south entrance to the cove. Then Pip sang out: 'All clear?'

'Seems all right,' Tim shouted back as the channel opened in front of them. He broke off short and stared suddenly. 'Great Scott!' he cried. 'Look at that fool of a woman.' He pointed to a figure which they could see dimly through the rush of rain, standing at the base of the cliff, about fifty yards to the right of the entrance to the cove.

'How the devil did she get there?' demanded Pip in dismay.

'Don't know, but she won't stay there long,' said Jim. 'The waves are breaking over that ledge already. She'll be drowned for a certainty if we don't get her off.'

His words were whipped away by a sudden gust of wind which roared down on them, and he had to yell to make himself heard. Pip did not waste breath. He saw at once that Jim was right, and that there was no time to lose.

'All right,' he answered. 'Get the oars out, Jim.'

Taking advantage of a momentary lull, he put the boat round with her head to wind, then while Jim steadied her with the oars, he swiftly got the sail down. The little craft bobbed wildly in the rapidly-rising sea, but Jim managed to keep her steady until Pip had finished stowing the sail.

'Let her drift in stern foremost,' he directed, as he picked up a coil of rope, 'but don't let her get too close, or she'll be smashed to bits. The only chance will be to chuck a rope to the woman and tow her off.'

As the boat drew closer to the cliff foot, Jim saw that the woman was a mere girl, and that she was standing on a fairly wide ledge, which was constantly hidden by spouts of foam from the breaking waves. He had not, however, much time to watch her, for it took all his strength to hold the boat against the furious drive of wind and sea, and prevent her from falling off into the trough.

Tho girl had seen them now. She had turned, and was facing them with her back against the cliff, which rose sheer behind her. Pip had scrambled past Jim, and stood in the stern with the rope in his hand. 'That'll do, Jim,' he cried. 'We daren't go in any further. Try and hold her now.'

The boat checked, and Jim wrought till his muscles cracked In the effort to keep her clear of the raging turmoil at the foot of the cliff. Pip steadied himself in the stern and waved the coil of rope.

'You must catch it,' he shouted to the girl above the roar of the surf. 'We can't land. We must tow you off.'

'I understand,' the girl answered in a high, clear voice. 'I shall be all right. I can swim.'

'She's a cool customer,' was Jim's thought, and just then came disaster. With a sharp crack one of the oars snapped off short, and in an instant the wind caught the boat and swung her round broadside into the surf.

'Jump!' roared Pip. A wave picked up the boat, tossed it high on the crest, and both men jumped for dear life. They sprawled on the ledge, just as a loud crash behind them announced the end of the boat. A small, but capable hand helped Jim to his feet, and he looked round to find Pip already scrambling up, apparently little the worse.

'Boat's done for,' he said. Jim turned round painfully, for his knees had suffered, and was just in time to see a mass of broken planks disappearing in a welter of foam.

'Oh, I am sorry!' cried the girl.

'So am I,' said Jim ruefully; then as he looked at the girl his face cleared a trifle, for even in that unpleasant moment he was quite sure he had never seen a prettier or more charming person. And the girl for her part was looking at him with an interest that' surprised him.

Pip cut in. 'Jim, the tide's rising. We shall be washed off this ledge inside ten minutes.'

'I can't help that,' said Jim. 'What are we going to do about it?'

Pip had no suggestion to make, and indeed their plight seemed, perfectly hopeless, for the cliff rose like a wall behind them, and the ledge was under water in the direction of the cove.

The girl came to the rescue. 'There is only one thing to do. Climb the cliff. No, I am not crazy.' she added with a quick smile. 'There is a way up and I had just found it when I was caught by the storm. Follow me and hold on tight.'

It was no joke working along the ledge, for every wave broke over them. Luckily the rocks were covered with tough sea-weed which gave them something to cling to. Presently the girl stopped and pointed to a narrow ledge some eight feet up.

'That is the way,' she explained, 'but it is out of my reach. If one of you would lift me?'

A wave breaking waist-high cut her short, and for a moment they all had to cling like limpets. When it passed Pip spoke. 'Give me a back, Jim. I'll go up first, then you can help Miss—?'

'Tremayne,' she put in. 'Nance Tremayne.' Pip was more active than he looked, and he scrambled rapidly on to Jim's shoulders, grabbed the ledge and hauled himself up.

'All right,' he sang out. 'Now you, Miss Tremayne.'

Miss Tremayne made no bones about it, she was on Jim's shoulders quicker than Pip, and Pip helped her to the ledge.

'Big wave coming,' he sang out. 'Here, catch this, Jim.' Ha dropped one end of the rope which, luckily, he had managed to bring ashore with him, and it was only this that saved Jim, for the wave washed him clean off his feet, and but for the rope would have carried hint back into the sea. He was thankful, indeed, when, very breathless and battered, he found himself alongside the other two.

'That's splendid,' said Nance Tremayne brightly. 'Now we can go straight ahead.'

Jim looked up at the towering rock wall. 'Are you not a bit optimistic, Miss Tremayne?'

'I do not think so,' she answered with a smile. 'I have studied all this cliff face with glasses from the sea and planned a way up. It may be a stiff climb, but I believe it is possible.'

'Is cliff climbing your hobby?' Jim asked, but she shook her head.

'Not cliff—caves,' she answered cryptically, and without further explanation started.

'Gosh, she's like a cat!' said Pip, staring open-eyed as he watched her scramble from ledge to ledge. Her soaked clung to her slim figure, the wind and rain beat upon her, yet she went on and up, with a steadiness end confidence which delighted Jim as well as Pip, yet gave them all they knew in follow. It was no joke breasting that cliff face, with the knowledge that one slip or miss-step would mean a particularly messy and unpleasant death, and more than once Jim's heart was in his mouth when a gust flattened Nance Tremayne against a crag and forced her to cling until it passed.

Rather more than half way up a narrow ledge gave a chance to take breath, but instead of resting Nance moved along it to the mouth of a cave and stood peering into the dark tunnel. Jim followed.

'Is this your cave?' he asked with a laugh.

There was no answering smile on her face as she turned. 'I don't know,' she said gravely. 'I wish I did.'

The rest of the way was easier, but, as they climbed, Jim puzzled over this odd remark, yet could find no solution.

'I SAY, how lovely!' exclaimed Jim as he stopped on the cliff top and gazed down at the valley which lay to the right, and the quaint, old, stone built house, standing on the slope immediately below them.

The quick summer storm had passed and the sun's rays gleamed on the wet grass, the tall beech trees which backed the ancient house, and the gay little river that tumbled through the bottom of the glen.

'You like it?' asked Nance with a smile.

'I do,' said Jim. 'I never saw anything I liked so well. That old house exactly fits its surroundings. Whose is it?'

'Mine,' replied Nance, with a touch of pride. 'And since you have lost your boat in helping me I hope you I will let me offer you luncheon.'

'Impossible in this kit,' growled Pip in a voice meant only for Jim's ear, but Nance heard and laughed.

'You need not trouble yourself on that score,' she assured him. 'There is only my uncle and one other person besides our two servants and we live very quietly. We cannot afford to do anything else,' she added frankly.

'Then thank you very much,' said Jim. 'And may I introduce myself. I am Jim Coryton, lord of a few barren acres of Cornish soil, and this is Peter Paget, better known as Pip. He is an artist and lives at Corse, where I have been staying with him, and I'm willing to bet that he is aching to paint your wonderful old house.'

'Jim's right,' said Pip, with unusual earnestness. 'It's the most wonderful old bit of masonry I've ever seen.'

'It is called Rabb's Roost.' Nance told them as they walked on. 'It was built by a privateer called Reuben Rabb in the 17th century. I fancy he must have done pretty well out of his pirating for he certainly spared no expense in building. The walls are four feet thick. His only daughter married a Tremayne, and so it has come down to me. My father died when I was quite small, and my mother five years ago. So, as I was left all alone, my uncle Robert Tremayne, came to look after me.'

'And what do you do with yourself?' Jim asked bluntly. Nance interested him immensely and he wondered how such a bright, vivid creature could live in this remote valley with no company but an uncle.

'I always find plenty to do,' Nance assured him. 'I have the house and my garden. I fish and sail. Of course, there is no society, but really I am never dull.'

While they talked they passed through the trees and came to the house by a gate leading into the garden It was a great square place that would have been grim only for the mellowed colouring of its weather-beaten walls, the masses of creepers, and the beauty of its wide windows.

As they went up the steps the great iron-studded oak door opened; and a stout, genial-looking man of about fifty, dressed in rather shabby grey tweeds, appeared.

'Why, Nance—' he began, and stopped, gazing in evident surprise, at the two young men.

'My uncle, Mr. Paget,' said Nance. 'And this is Mr. Coryton, Uncle Robert. They saved my life and lost their boat in doing it, so the least I could do was to ask them to luncheon.'

'Saved your life! exclaimed the other. 'Nance, what mad prank have you been up to?' Then, as his eyes fell on Jim Coryton's face, he started quite sharply, and stood gazing at him with a look of such amazement as badly puzzled Jim.

But Mr. Tremayne recovered himself quickly. 'Come in, gentlemen,' he begged. 'Come in and we will find you some dry things. Then at lunch I must hear all about it.'

He led them through a lofty, stone-paved hail up a broad oak staircase into a bedroom, hurried off and came back with a great bundle of clothes and clean towels.

'I hope you will be able to make out,' he said courteously. 'Please ring if there is anything you want.'

'Jolly old bird,' observed Pip, as the door closed behind their host. 'And the girl's not bad looking.'

Jim, pulling on a pair of grey flannel trousers, looked at him pityingly. 'You poor fish, she's lovely.'

Pip's grin was hidden by the shirt he was pulling over his head, and he wisely held his peace until they both had finished changing.

'You look a howling swell, Jim,' he observed, as they went down. 'Those clothes might have been made for you.'

'They really might,' admitted Jim. 'Nice stuff, too. I wonder whose they are.'

But his curiosity on this point remained unsatisfied, for their host appeared at the foot of the stairs and led them into the dining-room, where Nance, changed and dainty, was already waiting. As they entered the room Jim noticed that Nance gave him another quick, surprised look, but he had not time to wonder about it, for a plate of most excellent cold beef occupied all his attention.

Robert Tremayne courteously refrained from questioning his guests until they had finished their first course, but when the beef was succeeded by apple' pasty and Cornish cream he begged Jim to tell his story.

'We were fishing, sir, and got caught in the storm and ran for the cove. Then we saw your niece on the rock, and went to fetch her, and an oar broke, and the boat got smashed. So we landed, and Miss Tremayne showed us a way up the cliff; and—and that's all.'

'All,' repeated Nance with scorn. 'It's quite evident you are not an author, Mr. Coryton. I never heard such a lame story in my life. The fact is, Uncle Bob, that they both risked their lives to reach me and lost their boat.'

'But my dear Nance,' remonstrated her uncle, 'will you tell me what you were doing at all in such a place.'

'Looking for the cave,' replied Nance. 'I found it, too.'

'The cave?' repeated Robert Tremayne. 'You don't mean—?'

'I do,' cut in Nance. 'Of course I don't know if it really is the other entrance, but there is a hole running deep into the cliff face.'

She turned to her puzzled guests.

'I must explain,' she said. 'The story is that Reuben Rabb hid his treasure in some deep hole in the rock under the house and that there is a way into it from the cliff face. Of course, it's all nonsense.' she added, with a laugh, 'but Uncle Bob won't let me say so, for he thinks it a good bait to attract P.G.'s.'

'What's a P.G.?' Pip blurted out.

'A paying guest, Mr. Paget,' said Nance. 'Since the house is so big and our means so small, Uncle and I have gone into the hotel business. We have one guest already, and another coming in soon.'

'What a topping notion!' exclaimed Pip, 'and, I say, do you really allow your P.G.'s to go hunting?'

Mr. Tremayne spoke. 'We do,' he said quite seriously. 'Nance laughed but there is good evidence that one piratical ancestor die really hide his loot in some cave or cellar. He must have been a rich man or he could never have, built such a big house, and we know that he died only two years after it was built. There were no banks in those days, and a man like Rabb would never have trusted his gold in the hands of the Jews. Besides there is his will, leaving 'my treasure of Spanish plate to my beloved daughter, Miriam.'

Pip's eyes widened.

'I say, this is topping. I've always longed to go treasure hunting. May I come as a paying guest, Mr. Tremayne, and help in the search.'

'I hope you will stay as long a you like, Mr. Paget.' said Mr. Tremayne gravely. 'There can be no question of payment after what you and Mr Coryton have done for my niece.'

Pip looked rather confused. 'I didn't mean—' he began, but just then the door opened and a big, solemn-looking man came in. He was about 40 and good-looking in a heavy way, with china- blue eyes, pink skin, and a fair moustache.

'Just in time for lunch. Mr. Aylmer,' said Nance. 'Let me introduce you to Mr. Coryton and Mr. Paget.'

Aylmer bowed to the two men, and took his seat silently.

'Did you get any fish?' Mr. Tremayne asked him.

'Four, then the storm came and spoilt the rise,' said Aylmer briefly as he began on his beef. After that there was not much more talk, and presently Nance got up.

'You will excuse us, Mr. Aylmer.' she said. 'I want to show our friends the house.'

'Terribly silent person, is he not?' she said to Jim and Pip as they reached the hall. 'I call him Stately Edward,' she added with a twinkle of fun.

'Is he treasure hunting?' asked Pip.

'I don't think so. He spends most of his time fishing. Now would you like to see the house?'

'Rather!' said Pip keenly, and Nance took them all over the strange old place beginning with tho upper floors and ending with the huge stone paved kitchen. Here a bright-eyed little man, and a tidy-looking woman were busy.

'These are Mr. and Mrs. Ching,' said Nance.

'Ching,' replied Pip, and the little man turned quickly. 'You, Mr. Peter. Why, fancy you being here!'

'You know Ching, Mr. Paget?' exclaimed Nance in surprise. 'I used to anyhow,' said Pip as he shook hands with the little man. 'Ching was our footman at Corse when I was a kid.'

Ching fairly beamed with pleasure. 'Fifteen years ago, Mr. Peter, and I have been with Mr. Tremayne and Miss Nance going on six years. You staying here, Mr. Peter?'

'He is staying the night at least.' put in Nance, 'and I hope, longer. These two gentlemen saved my life this morning, Ching. The storm caught me on the Shag Rock, and if it had not been for them I shouldn't be here now.'

'You don't say, miss!' exclaimed Mr Ching, but the look in his eyes told Jim a good deal more than the mere words. He realised that Ching was devoted to Nance.

'Well, this is nice,' said Nance, as they left the kitchen. 'Fancy your knowing Ching, Mr. Paget!'

'I know him for a real good man,' said Pip.

'He is all of that,' said Nance! mm warmly. 'He and his wife run the whole house for us. They are perfectly wonderful. And now what would you two like to do?'

'We ought to think of going home,' said Jim.

'That is the one thing you are not to think of,' said Nance earnestly. 'Please stay, at any rate, for the night. It will be such a pleasure to my uncle—and to me. Mr. Aylmer is so very silent, and it is a long time since we have had any real visitors.'

'It's awfully kind of you,' said Jim. 'If you are sure it is not putting you out?'

'Quite—quite sure,' vowed Nance. 'There, that's settled, and now tell me what you will do.'

'I want to sketch the house,' said Pip promptly.

'You shall have drawing paper and pencils, even some colours.'

'And I would like to look at the brook.' said Jim. 'I haven't even seen a trout for ages.'

'Then you shall catch some,' declared Nance. 'Uncle Bob's rod is in the gun room.'

The rod, if old, was a beauty, Uncle Robert's fly-book was well stocked, and presently Jim found himself wandering along the bank of a most entrancing little river. The storm had coloured the water slightly, and the warm sun brought up a big hatch of fly. The pools were starred with rising fish, and, as his casting skill came back, one lusty little trout after another came to the net.

Of late Jim had been working in London, and it was years since he if had enjoyed such fishing. Entirely forgetful of time, he walked on and on until dusk found him far up the high moor, surrounded by great heather-clad hills, on which the only sign of civilisation was a bare road drawn like a grey riband across the waste.

He looked at his wrist-watch and whistled softly.

'I shall have to hurry to be back for dinner,' he remarked aloud. 'I'd best get to the road. It will be quicker than the river bank.'

He reeled up, fastened his fly into a ring, settled his heavy creel on his back, and started for the road. Before he reached it he saw a man on a bicycle top the rise to the east and come down the long hill at a tremendous pace.

'He's in a deuce of a hurry,' he said to himself.

Next moment the distant bark of a motor cycle's exhaust came to his ears, and grew rapidly louder. Then against the pale evening sky he saw a second man flash into sight on a powerful machine, and roar down the slope at something like a mile a minute. The man on the motor-cycle was near enough to see his face. He passed in a cloud of dust and rapidly overhauled the pedal cyclist.

As he came near the latter Jim saw the cyclist look round.

'Stop!' shouted the motor rider in a loud, harsh voice, but the other sprang from his machine, and letting it fall in the road dashed away across the moor. The motor cyclist also stopped and Jim saw him draw something from his belt. The sharp crack of a pistol echoed across the moor, and the running man flung up his arms and fell.

A passion of anger surged through Jim's veins. 'You damned murderer!' he roared and started running hard towards the man with the pistol. For a moment the latter paused and Jim, had a feeling he was going to fire. Perhaps it was Jim's fearless rush that alarmed him, perhaps he thought other help was at hand; at any rate instead of firing he swung his leg over the saddle of his bicycle and was away like a flash down the long white road.

Since pursuit was out of the question Jim hurried across to the fallen man, who lay face down in the heather. At first Jim feared he was dead he lay so still, but in a moment he saw he was still breathing. His face was buried in the thick soft heather, so Jim stooping, got his arms around the man's body and lifted him so as to lay him in a more comfortable position as he turned the man over Jim got the shock of his life, for he found himself looking down at his own double.

The same black hair, the same straight nose, firm chin, and clear brown skin. The eyes, it is true were closed, yet Jim had the faintest doubt they were the same dark blue that he himself had inherited from his Cornish mother.

THE wounded man's eyes opened, and, just at Jim had felt certain, they were blue—very dark blue. They completed the extraordinary resemblance between himself and this stranger, and for the moment Jim was too lost in astonishment to think of anything else. The other, the wounded man, also saw the likeness, for, as he stared up at Jim, a puzzled look spread across his face.

'Who are you?' he asked hoarsely, and there was something like fear in his voice.

'My name is Coryton,' Jim answered quietly.

'You're not one of them?' demanded the other anxiously. Jim saw that he was still suffering from shock, and answered gently. 'If you mean have I anything to do with that ruffian who shot at you, certainly not.'

The wounded man sighed with relief.

'I thought not. I felt you were all right. But where is that fellow on the motor-bike?'

'Gone. He cleared as I ran up. I'd been fishing,' Jim explained, 'and I saw the whole thing.'

'But my pic—my parcel?' exclaimed the other sharply.

'Is this what you mean?' said Jim picking up a small roll wrapped in waterproof, and very carefully tied up. A look of intense relief came into the wounded man's eyes.

'That's what he was after. Thanks be he didn't get it. You're sure he's gone?'

'At the rate he was travelling, he is a good five miles away this minute. And now, suppose you let me have a look at this hole he's made in you. You're bleeding rather badly.'

'It's frightfully good of you,' said the other gratefully, and Jim set to work. The blood was coming from the man's right side, and Jim, after getting his waistcoat and shirt open, found a small blue mark where the bullet had entered and a large hole behind where it had come out.

'You're in luck,' he said. 'I don't know much about gunshot wounds, but I'm pretty sure the bullet has glanced on a rib. Anyhow It's come out. If I can stop the bleeding you'll be all right.'

Jim knew just as much or as little about surgery as the average man gets from an ordinary ambulance course. At any rate his knowledge was sufficient to enable him to pad the two wounds and fasten a tight bandage made of ties and handkerchiefs round the young fellow's chest. Then he got some water from the brook and was pleased to see a little colour come back to the other's face.

'And now,' he said, 'I'd better take your bicycle and go for help. You're not fit to walk.'

'No!' exclaimed the other in a panic, then he pulled himself up. 'Forgive me,' he said, in a quieter tone. 'You see they've been chasing me for a week, and my nerves have gone all to pot. But indeed I can walk quite well, and I'd much sooner you didn't leave me alone.'

Chased for a week! Dick's surprise showed itself in his face.

'They were after this,' explained the other, indicating the parcel. 'I've had the deuce of a time; and now that I've got it so near home I naturally don't want to risk losing it.'

'You're none too fit to move,' said Jim. 'How far have you to go?'

'A couple of miles. A place called Rabb's Roost. Do you know it?'

'I ought to,' said Jim. 'I'm staying there.'

'You know my father?'

'If your father is Mr. Robert Tremayne, I do.'

'He is my father. I'm Maurice Tremayne.'

'I hadn't heard of you,' confessed Jim. 'My acquaintance with your father is only a few hours old. My friend, Paget, and I had the good luck to give Miss Tremayne a little help during the storm this morning, and since we lost our boat in doing so she asked us to stay the night.' He laughed. 'It's your father's rod I have been using all the afternoon.'

'This is great,' said Maurice, delighted, and he laughed, too. 'Now I really feel safe with you.'

'You ought to,' said Jim drily.

Maurice nodded. 'You mean the likeness. It's simply amazing. When I woke up just now and saw you I thought I was seeing myself in, a looking glass.' He gazed frankly at Jim. 'By gad, we might be twins, only I fancy I'm a year or two the younger. I don't wonder that blighter on the motor bike was scared when he saw the double of his victim coming after him.'

'That explains it,' said Jim. 'I was wondering why he cleared out in such a hurry. But see here, Tremayne, it'll be dark in another hour, ana we ought to be back. Do you think you could sit on your bicycle if I pushed it?'

'I can walk all right,' vowed Maurice.

'You wouldn't get far,' Jim assured him. 'You'd only start that wound bleeding again. I think my plan is the best.'

'It's uncommon good of you,' said Maurice gratefully. 'Luckily it's nearly all downhill, so we ought to manage without killing you.'

'It would take a lot to kill me,' laughed Jim, as he helped the other to his feet.

'You take the parcel. It's a picture,' said Maurice. 'And if we are attacked again I want you to promise not to think of me, but only of the picture.'

'That's rather a tall order,' said Jim, as he steered the other towards the road. 'May one ask why it means so much?'

'It's a Memling,' said Maurice simply. Jim shook his head.

'That doesn't mean anything to me, Tremayne. I've heard of Raphael and Velasquez, but there my knowledge of old masters ceases.'

'Memling was a Flemish painter of the fifteenth century,' Maurice explained, 'and even in those benighted days was known from England to Italy. His colours were so wonderful that they are as bright to-day as they were when he put them on canvas four hundred and fifty years ago. And his backgrounds—but you must see them to appreciate them. They're wonderful!'

'Must be if a man is ready to commit murder for one,' remarked Jim.

'Oh, there's more to it than that,' Maurice answered quickly, but Jim checked him.

'You've talked about enough for the present, Tremayne. I mean, you're going to need all your energies for this ride. You shall tell me the rest when we're safe at home.'

'I daresay you're right,' Maurice I admitted, as Jim helped him on to the bicycle and started.

With one of Maurice's arms over Jim's shoulder they got along pretty well, but all the same, it was a slow job. An anxious one, too, for Maurice evidently expected another attack. But all the way home they did not see a living soul, and they arrived at the Roost just as the lamps were being lit.

Peter was waiting on the bridge.

'You're a nice chap, Jim,' he began, and then he saw Jim's double, and stood, speechless.

'This is Maurice Tremayne, Pip,' Jim explained briefly. 'He's had an accident, but is not badly hurt. Cut up to the house and tell Ching to get a room ready, and explain things to his father and Miss Tremayne. Be sure to tell them he's not badly hurt.'

'Right,' said Pip, and went like a shot. It was not the first time that Jim had marvelled at the way the plump little man could move when there was occasion to do so.

By the time Jim and Maurice reached the door Mr. Tremayne and Nance were there to meet them.

'An accident, Mr. Coryton?' asked Tremayne anxiously. 'Not badly hurt, Mr. Paget says.'

'Nothing to make a song about, Dad,' said Maurice pluckily, but as he came into the light and his father saw how white he was, his own face went ghastly.

'I give you my word it is not serious,' said Jim quickly. 'He has lost some blood, but a few days in bed will put him right. Shall I go for a doctor?'

'No doctor,' said Maurice firmly. 'I mean it. Ching can fix me up.'

Nance had hurried into the dining room, and now came back with two fairly stiff-looking whiskies and soda, one of which she handed to Maurice and one to Jim.

'Best thing I ever drank,' vowed Maurice, as he finished his glass. 'Ah, here's Ching. Give me an arm to my room, Ching, and don't look so worried. I'm not going to die on you, yet.'

With Ching on one side and Pip on the other, Maurice went upstairs. At the top he looked round.

'Take care of the picture, Coryton,' he said.

'You bet,' Jim promised, and just then he caught sight of a face looking round the half-open dining-room door.

It was Edward Aylmer's, but so changed that Jim hardly recognised it. The sleepy eyes were wide and bright, the whole expression had a look of aliveness which was positively startling. It was only a glimpse, for, catching Jim's eye fixed upon him, Aylmer drew back at once.

'A queer bird that,' said Jim to himself as he went up to his room for a wash. 'Strikes me he'll bear watching.'

He locked the picture in a drawer before he came down and put the key in his pocket.

SUPPER was waiting when Jim came down. So was Nance, in a pale blue crêpe de chine which suited her fair skin admirably, and Jim thought she looked more delightful than ever.

'Maurice has been telling me,' she said eagerly. 'It was splendid of you, Mr. Coryton. That man might have shot you.'

'Not he!' laughed Jim. 'He was much too scared.'

Nance nodded. 'Yes, Maurice told me. But, of course, the likeness was the first tiling that struck me when you came to my help this morning. You must have thought it odd, the way I stared at you. Uncle Bob, too, got a shock. Now sit down and eat. You must be starved.'

'Not after that luncheon you gave me. All the same, I'm hungry.'

'Then sit still and I will help you. This is a home-grown chicken and the lettuces are from my garden.'

'It's the best chicken I ever ate,' Jim vowed, as he set to. 'Tell me, how is the patient?'

'Wonderfully well, considering all things,' Nance answered. 'Ching has dressed the wounds. Ching is almost as good as a doctor.'

'But ought you not have a doctor?' Jim asked.

'Maurice won't. He is desperately anxious to keep the whole thing quiet, until Mr. Vanneck come for his picture.' Then seeing Jim's blank look, 'Has he not told you?' she added.

'I wouldn't let him talk,' Jim said. 'All I know is that he has got hold of a wonderful old picture and that someone has been trying to steal if from him.'

'It is a Memling,' Nance explained. 'There are very few of his paintings in existence, and this is worth an enormous sum. Mr. Adrian Vanneck, the Boston collector, bought it in Italy six months ago, but as you know, Italian law is strict about letting old masters out of the country, and the only way is to smuggle them out. Maurice knows Italy well and speaks Italian like a native, and Mr. Vanneck offered him five hundred pounds to get the picture for him. As you see, Maurice has succeeded.'

'But good heavens!' broke in Jim, 'You don't mean to say that the Italians employ gunmen to chase smugglers!'

'No,' said Nance. 'I doubt if the Italian authorities are even aware that the picture is out of their country. That gunman was employed by Paul Sharland.'

'And who may he be?'

'It is a little difficult to say. He calls himself a collector, but Maurice calls him a crook. One, thing is certain. He has a bitter grudge against Vanneck, and will go to any lengths to spite him. In some way—Maurice does not know how—he got wind of this transaction, and planted two of his men at Genoa with directions to waylay Maurice and take the picture from him. He knew, of course, that Maurice could not go to the police, and reckoned to get hold of the picture, take it to America and sell it there for a large sum. Maurice was told of this plot, and with the help of an Italian friend named Rimi, trapped the two thieves and left them locked in a cellar while he got safely to the boat.'

Jim chuckled, 'That was smart.'

Nance went on.

'That was not the end of it. Sharland had another agent on the boat, who drugged Maurice and turned his cabin inside out, But Maurice had the picture in the ship's safe, so again they missed it. At Marseilles Sharland's people were still after him and they stole his suit-case, substituting another exactly like it. But the picture was in the lining of his coat so they failed for a third time. At Paris Maurice dodged them, took a car, drove to Cherbourg and came over on a White Star boat to Southampton. That seems to have thrown them off the scent, for they thought he was coming to Croydon by air. So Maurice reached Bude and, thinking himself quite safe, hired a bicycle to ride home. You know the rest.'

'I do,' said Jim, gravely. 'Has Maurice any notion who the fellow was who tried to murder him?'

'He is not certain, but he thinks it is a man named Midian. A year ago he caught Midian poaching our river. He was using dynamite which, as you know, kills every fish in the Pool. Midian turned nasty and attacked Maurice, but Maurice is quite a good boxer, and managed to knock the man down. Midian rolled into the river and was half drowned before Maurice got him out. He made the most fearful threats and is the sort to carry them out.'

'Did Maurice recognise him?'

'No, for Midian, as he remembers him has a beard, and this man was clean-shaven. Still, I think he is pretty sure about it.'

Jim nodded. 'And what happens now?' he asked.

'The next thing is to let Mr. Vanneck know we have the picture. Mr. Vanneck is in New York, but as soon as he hears be will come for the picture in his yacht.'

Jim pursed his lips. 'Which means at least a fortnight's delay,' he said; 'and meantime you have to keep the picture here. 'I don't want to alarm you Miss Tremayne, but doesn't it occur to you that the gentle Sharland may keep a pet burglar?'

'Exactly what Maurice said, but luckily we have a hiding place that would defy any burglar. It is a cellar with a secret door. If you will give me the picture I will put it then myself.'

'Good!' said Jim. 'And may I ask how many people know of this secret hiding place?'

'Just four—my uncle, myself, Maurice and Ching.'

'Not Aylmer?' Nance looked at him rather oddly.

'Why do you ask that. Mr. Coryton? You are not suspecting him of being Mr. Sharland in disguise?'

'I am not suspecting him of anything. It is only another case of Dr. Fell.'

'Dr. Fell,' said Nance puzzled. Then she laughed. 'Of course, and I have much the same feeling,' she added, confidently. Then she got up. 'I must go and see to Maurice. Mrs. Ching will bring you some coffee, Mr. Coryton.'

Jim opened the door for her, and she ran lightly upstairs, turned at the top and gave him a little friendly wave of the hand before disappearing Into her cousin's room.

'You're right, Jim,' came Pip's voice out of the dimness of the hall.

'What are you talking about, Pip?'

'She's more than nice-looking. She's a very nice girl.'

'I didn't need a whole day in find that out,' retorted Jim, and then Mrs. Ching came with coffee in delicate little Sèvres cups, and the two men lit cigarettes and sat down together.

'Jim,' said Pip, as he laid down his cup, 'this is a rum start.'

'I take it you've heard all about it?' said Jim.

'Yes; Mr. Tremayne told me.'

'I agree,' said Jim. 'It is a very rum start, and I think it's just as well that you and I are here for the night.'

'You mean that this Sharland per son might try something?'

'He's tried murder already,' said Jim, drily.

Pip nodded. 'But the picture is safe at present.'

'So Miss Tremayne tells me, and with four men in the house I don't fancy there'll be any attempt in night.'

'Five, you mean?' said Pip.

'I wasn't counting Aylmer.'

'Why not?' asked Pip. 'He's a pretty hefty chap.'

'Oh, he's all that; but—well, I don't quite cotton to him.'

'He's all right,' said Pip. 'He and I had a long yarn this afternoon while you were out. He's quite a good sort.'

'I'll take your word for it,' said Jim, smiling, as he pinched out his cigarette. 'I think I'll turn in, old chap. I'd pretty fagged.'

'I should rather think you were. Go ahead. I'll have another cigarette, and follow your example.'

Jim was asleep almost as soon as his head touched the pillow, but it was another hour before Pip went up, and even then a long time before he got to sleep. A breeze had sprung up, blowing in from the sea, and the wind moaned around the old house, making strange and eerie sounds.

At last Pip dropped off, only to be awakened by a knocking, repeated at regular intervals. It kept on and on with maddening reiteration, until at last Pip could stand it no longer. So he got up, lit a candle, and went to Investigate. The sound came from below, and Pip became convinced that it was one of the Venetian blinds in a window below, which had come loose from its fastening and was flapping in the breeze.

'I must stop that, of I shan't get a wink,' he said to himself, and taking the candle, opened the door and started for the head of the stairs. Pip's room was on the west side of the house, facing the sea, and he had to go along a passage and through a swing door to gain the head of the stairs.

As he opened the swing door the draught blew out his candle, and to his disgust he found he had left his match-box in his bedroom. As he hesitated, wondering whether to go back for it or chance finding his way in the dark, ha heard a slight sound. He spun round, but quick as he was, the other was quicker. A pair of arms caught Pip round the waist, he was tripped with neatness and despatch, and found himself flat on the floor with a man's weight on top of him.

'LIE still!' hissed a voice in Pip's ear. 'Lie still, by gum, or I'll let you have it.'

'What the deuce!' gasped Pip. 'What in blazes are you doing, Ching?'

'You, Mr. Peter!' The dismay in Ching's voice almost made Pip laugh. 'I thought it was that there Aylmer.' As he spoke he got up quickly and helped Pip to his feet.

'Aylmer?' questioned Pip. 'What made you think I was Aylmer?'

'Because he's always a-prowling round,' replied Ching viciously. 'And when I heard a door open I made sure it was him.'

'But what would he be after?' asked Pip, in amazement.

'The treasure, I reckon,' Ching answered.

Pip laughed softly. 'But why should be hunt that at night when He is at liberty to do so in daylight?'

'I don't know, Mr. Peter. But he's been round the house more nights than one.'

'That's odd,' said Pip thoughtfully. 'You don't think he'd be after the picture, do you?'

'That's more'n I can say, sir, but I don't trust the gent, and he ain't going to get away with anything in this house so long as I'm here to watch.'

'Funny you don't like him,' said Pip slowly, 'for Mr. Coryton feels the same way.'

'And so would you, Mr. Peter, if you knew him as well as I do. Well, I'm glad it wasn't him this time, and I only hope I didn't hurt you, sir.'

Pip chuckled. 'Take more than your weight to hurt me, Ching. And luckily we fell on the carpet, so we don't seem to have wakened anyone. Oh, by the bye, there's a blind rattling below, that's what brought me out of bed.'

'I know which it is. It's in the smoking-room. I'll fasten it, sir, and you go back to bed.'

Pip went back to bed, but not to sleep, for he was puzzling over what he had heard from Ching. Himself, he had rather liked Aylmer, with whom he had had quite a chat the previous afternoon. One thing very certain was that Aylmer knew a good deal about painting, while another impression Pip had got was that Aylmer was quite well off.

'Yet Ching hates him,' he mused, 'and Jim dislikes him on sight. Pretty funny nest of mystery we've tumbled into, but—I don't want to leave it.' And with that thought uppermost in his mind he fell asleep.

THE wind from the sea had brought up rain, soft summer stuff,

and next morning the high moors inland was hidden by a gently-

falling drizzle. Maurice was better, so Nancy told them at

breakfast, then, as Aylmer was present, she talked of general

things. Aylmer, as usual, spoke little, but when he did speak his

voice was quiet, and his manners were extremely good. Pip,

watching him covertly, wondered what the others could possibly

have against this reticent, well-bred, well-dressed man.

Breakfast over, Aylmer got up.

'I think it will clear later,' he said. 'And the water is almost perfect. I shall put on a macintosh and try for a few fish.'

'Tight lines,' said Pip genially, and with a nod of thanks Aylmer left the room.

'And Paget and I must be leaving,' said Jim, and was surprised, and at the same time delighted to see the look of dismay on Nance's mobile face.

'But you can't,' she exclaimed sharply. 'Not with Maurice—' She pulled herself up. 'Forgive me. I am forgetting that you may have business of your own.'

Pip laughed. 'Business! My dear Miss Tremayne, I never had any business in my life, except making vain attempts to sell my pictures. And as for Jim here. I'll swear he hasn't any for the next fortnight. If you really want us we are both very much at your service.'

'Pip is perfectly right, Miss Tremayne,' said Jim. 'Only if we do stay you might make use of us.'

His heart warmed at Nance's look of relief.

'You are the two kindest men I ever knew,' she vowed. 'And you make it easy for me to ask the favour I was going to ask. Will one of you go to Bude and send the cable to Mr. Vanneck?'

'Of course. I will,' Jim answered readily. 'Give it to me and I will be off this minute.'

'But we have no car,' Nance said, 'and it's a long way.'

'Your cousin's bicycle is here, and I'm quite a decent cyclist,' said Jim. 'I will be there and back before lunch.'

'Where do I come in?' asked Pip, with an injured air.

'You'll go and pick up the creel full of trout I jettisoned last night,' Jim told him. 'After that you can watch till I come back.'

Pip grinned. 'All right. After all, your long legs will do the journey quicker than my short ones. And bring some baccy when you come. I haven't a pouchful left.'

'I will write the cable,' said Nance. 'It will be in cypher, Mr. Coryton, so you need not be afraid of anyone else knowing what it is about.'

'Right,' replied Jim, 'and meantime I'll get the bicycle.'

The machine seemed none the worse for its tumble on the previous night, but Jim went over it and oiled it carefully. As he wheeled it round he found Nance waiting with the form.

'I wish it were not so wet,' she said regretfully. 'But here is Maurice's fishing coat which he hopes you will wear. And—' she hesitated—'What about taking Maurice's pistol, too?'

'You mean in case I meet the gentle Midian,' smiled Jim. 'Well, it might be a good idea.'

'I have it here,' said Nance, handing him a small but useful- looking automatic, 'He says that you must remember it goes on shooting as long as you keep your finger on the trigger.'

'All the worse for Midian,' laughed Jim. 'Tell your cousin that, if I do meet Master Midian I shan't take my finger off the trigger.'

He jumped on the machine and peddled away, and as he reached the road and turned to the left, he saw Nance still in the porch watching. He waved his hand, then the trees hid her, and he was riding slowly up the long, steep slope down which he had wheeled Maurice on the previous evening.

It was not a nice day, for the rain fell steadily, and though Maurice's coat kept Jim's body dry it failed to protect his knees, which were soaked until the water ran down his legs into his boots. As he reached higher ground he found himself in the clouds. The mist was so thick he could not see one telegraph post from the next. Little streams gurgled in the heather, puddles splashed under his tyres. There was only one consolation, which was that if Midian or any of his precious gang was watching they would have their work cut out to see him. But the road was deserted, and for the first three miles he did not meet a living soul.

Then he struck the main road and turned north, and after that met an occasional car or lorry. He plugged along steadily, and in little more than an hour later he found himself in the straggling town of Bude. No doubt there were holiday-makers about, but they were not visible. Streets and window panes streamed alike, and the usually bright little resort was in a state of complete eclipse.

Jim found the post office and sent his cable, then he visited the nearest hotel and sampled the favourite West Country drink, gin hot with sugar and lemon. After that he bought Pip a tobacco and a box of really good chocolates, which he had wrapped carefully against the rain. Inside twenty minutes he was ready for the road again.

There was no let-up in the rain; if anything, it was heavier than before. No wind, and it fell straight from the low-lying clouds. The water sloshed in Jim's shoes, and, as he turned at last into the branch road leading to Rabb's Roost, he thought with longing anticipation of dry things, luncheon and, perhaps, the company of Nance over a fire.

All down hill here, and he put on the pace. He was a mile from, the turn and on the steepest of the slope when he caught a suspicious gleam on tho wet road ahead and swerved quickly. He avoided a nasty, jagged piece of glass by a matter of inches only to hear a sharp pop and a quick hiss which told that he had hit a second. Braking, Jim hopped off in a hurry, but the front tyre was hopelessly crushed and completely flat.

'Damn!' said Jim, very loudly and distinctly, and paused to wonder whether it was worth while attempting a mend or whether it would be quicker to walk the rest of the way. He was not given time to decide, for a shadow that lurked behind a gorse bush leaped, and before Jim could straighten himself, let alone pull his pistol, something heavy as lead fell across the back of his head and stretched him senseless on the wet road.

WHEN Jim struggled back to life all he was conscious of was the worst headache he had ever known. His head felt as big as two, it throbbed in the most dreadful fashion and, when he tried to move, the pains that shot through it made him giddy and sick. He closed his eyes again and lay perfectly still.

By degrees he realised that he was lying on a pile of dry leaves or bracken in a place that was nearly dark, but how he had got there he could not remember, and any effort to do so brought the pain to an unbearable pitch. He was cold all over his body, but his head was burning. His mouth and throat were like parchment ana his tongue felt swollen and stiff.

Someone moved. He heard the soles of boots grate on stones, and be came vaguely conscious that a man was standing near him. but he dared not open his eyes.

'Ye dog-gone fool!' came a sharp voice. 'You coshed him too hard. You've done him in.'

'His head ain't that soft, Butch,' replied a second voice. 'And anyways, I owe him one fer near drowning me last fall.'

'You better remember the boss don't pay you to work off your own grudges,' said the man called Butch cuttingly. 'Another thing, this ain't Maurice. Not if what you told me yesterday about getting him with your rod was true.'

'If it ain't Maurice Tremayne it's his twin brother, so it's all in the family,' replied the other speaker, with a brutal laugh.

'You'll laugh the other side of your face if this bloke don't come round,' threatened Butch.

In spite of the pain in his head Jim was listening keenly, and had already realised that it was Midian who had 'coshed' him. Butch, by his voice, was American, and it was clear that these two ruffians had got him away to some hiding place and meant to hold him there for the purposes of their own.

'You leave him be and he'll come round all right,' said Midian, and Jim heard him turn on his heel and tramp away. The other man did not follow, and Jim, who was suffering agonies from thirst, decided to appeal to him.

He stirred slightly and opened his eyes. 'Water,' he gasped, and the sound of his own voice almost frightened him, for it was like the croak of a frog.

'Ain't dead, anyways,' remarked Butch, speaking rather to himself than to Jim. He turned away, and Jim saw him pass out through a doorway opposite.

Now that his eyes were open, Jim saw that he was lying in a bare, ruinous place, built of stone, with a slate roof and a roughly-paved floor. With his knowledge of the Cornish moors, he recognised it at once as an old mine building.

There are scores of deserted, disused mines scattered over the length and breadth of the Cornish moors; gaunt, dismal relics of long-past prosperity. No better hiding place could be imagined, for a gang of criminals, for these places remain unvisited from one year's end to another. Not even a tramp or a tourist comes near them. The risk is too great, for shafts of unknown depths drop down through the granite rock into pits full of cold, dark water.

Where he was, Jim could not even guess, for he had no idea how long he had been unconscious after Midian's brutal blow. He might be five miles from Rabb's Roost, or he might be twenty. He could not even tell what time it was, for the only opening high in the wall gave upon a grey sky from which the rain still poured down ceaselessly. As for his ears, all they could tell him was that water was running somewhere near, for he could distinctly hear the splash and tinkle of a runnel.

He wondered whether they had missed him at the Roost, and there drifted back to his mind a remembrance of the box of chocolates he had bought in Bude to give to Nance. A spasm of anger seized him at the thought of these falling into the filthy hands of Midian.

These vague thoughts were interrupted by the opening of a door, and the man, Butch, returning with a tin mug in his hand. Butch, Jim saw, was a very different type from Midian. He was middle-sized, squarely-built, and wore a rough, blue serge suit and square-toed boots. At first sight he might have passed for a good-class artisan or mechanic. But his mouth was oddly straight and thin-lipped, and his eyes were pale blue, with a cold bleak look in them, which told its own story.

'Drink this,' he said, as he gave Jim the mug. The effort of lifting his head made Jim groan with pain, but Butch did not offer to help him only looked at him in a cold, detached way, and remarked, 'I thought he'd done you in when I first seed you. But there—Midian always was a fool.'

The mug was full of hot tea, black, strong stuff, with no milk and a good deal of brown sugar. The sort of drink that Jim would ordinarily have refused to touch, but now—now it was exactly what he wanted. He drained it to the last drop and fell back with a sigh of relief. Butch looked at him critically.

'Aye, you'll do now. Better take a nap, then you'll be all right.'

'I'm too cold to sleep,' Jim told him, and now lie spoke in a more natural voice. Butch grunted. 'We ain't got no blankets, except what we uses ourselves, but I reckon there's a couple o' sacks. You can have them.'

He fetched them and flung them down and Jim managed to pull them across his soaked legs, and presently grew warmer and dropped into sleep.

IT was grey dawn when he woke again, and although his head

still ached, the pain was nothing like so bad as it had been. The

rain had ceased, and outside all was quiet, except for the tinkle

of the rill. A less pleasant sound was of heavy snoring, and

looking round Jim saw that Midian had made up a bed in the other

corner, and, rolled in an old army blanket, was sleeping soundly.

He could see nothing of Butch.

Jim's first idea was escape, and he felt for the pistol which

Nance had given him. He was, however, hardly surprised to find

that gone. His pocket-book, too, had vanished, and so had

everything of value, even to the packet of tobacco he had bought

for Pip. Midian, of course, for Butch, bad man as he undoubtedly

was, did not strike him as being a sneak thief.

Jim glanced again at the sleeping Midian and wondered whether he could tackle him. He sat up cautiously and was horrified to find how shaky he was, and how his head swam. Actually, he had only just escaped concussion, but that he did not know. Being, however, in possession of his full senses, lie realised clearly that in his present state his chances in a tussle with this long ruffian would be exactly nil. He was not even quite sure whether he could walk, but meant to try.

Giddiness seized rum again as he got softly to his feet, but this passed, and with one eye on Midian he made for the door. He had been so sure it was locked that it was a real shock when it opened easily, it was a worse shock when he found Butch outside, leaning against the bare wall of the building with a half-burnt cigarette between his thin lips.

'Better?' remarked Butch, without moving. 'And where was you going, mister?'

'For some water,' Jim answered calmly. Butch nodded in the direction of the little leat which brought water from the hill above, and Jim, kneeling beside it, drank, then washed. The water, clear as crystal and cold as ice, was extraordinarily refreshing, and Jim spent nearly five minutes splashing it over his bruised head.

He got up, dripping, to find Butch alongside.

'Know where you are?' asked that gentleman, in his faintly nasal voice.

Jim looked about, but the mine-house was in a deep basin, with high, heathery hills on all sides. A black swamp occupied the bottom of the valley, with a broad ring of white cotton grass around it. The old mine road, now grassgrown, skirted this and wound away up the far hill. There was not a single landmark of any kind in sight.

'No,' said Jim frankly. 'I haven't a notion.'

Butch chuckled softly. 'It wouldn't do you much good if you did know, mister, for you ain't going to leave here till we gets our price.'

'And what may that be?' asked Jim, with an air of innocence.

Butch chuckled again.

'You knows as well as I do. It's that there picture.'

It was Jim's turn to laugh.

'Then I'm afraid you'll have to keep me a long time. The picture is not mine and my name is not Tremayne.'

BUTCH was not at all dismayed when he learned that Jim was not Tremayne.

'I knows that. Your name's Coryton, and it was you as scared that silly fool, Midian, after he'd as good as got the picture. But I reckon them Tremaynes will trade all right at least when they hears what's going to happen to you if thew don't.'

'Something with boiling oil in it?' suggested Jim.

Butch took him quite literally.

'I did see a feller have his hand held in a frying pan full of hot bacon grease,' he told Jim in a calm, matter-of-fact voice, which made Jim shiver inwardly, 'but I don't hold with that sort o' thing, myself, unless o' course you gotter make a chap squeak. In your case—' he looked at Jim reflectively, 'we was going to tell them as you wouldn't get no grub until we got the picture.'

'But why pitch on me?' asked Jim lightly. 'I'm a mere outsider, and have nothing to do with the picture.'

'Then why did you take that there cable for Vanneck?' asked Butch directly.

'I was staying in the house,' said Jim, still fencing. 'They take paying guests.'

Butch nodded. 'I knows all about that. But you ain't no paying guest, and it ain't any use pretending you are.'

Jim's heart sank. This fellow knew everything. But he stuck to his guns.

'It's true I'm not a paying guest at present, but I never knew the Tremaynes or anything about them until the day before yesterday.'

'You knowed enough to run an' help young Maurie Tremayne when Midian were after him. You saved him and you saved the girl. You're in this up to the neck, Mister Coryton, and here you stays until you starves or until I gets the picture.'

He spoke with a horrible air of finality which made Jim's spirits sink lower than ever.

He tried another tack. 'There are police even in Cornwall,' he remarked, but Butch only smiled bleakly.

'I ain't losing any sleep over them Cornish flatties,' he answered. 'It 'ud take a regiment of 'em to find this here place, and you'd be dead before they'd got started.'

'You're full of pleasant thoughts, aren't you, Mr. Butch?' retorted Jim, but his sarcasm fell flat.

'It's the picture I wants,' said the other. 'I ain't got any special spite against you.'

'Well, I hope the spite doesn't begin just yet,' said Jim. 'Not till after breakfast, anyhow.'

'No,' said Butch. 'You gets your grub to-day. But if they turns you down, then God help you.'

With that he pointed to the door of the mine house. 'You'll stay inside arter this,' he ordered. 'And my advice to you is, don't try any games. I'm mighty useful with guns of all sorts, and I've killed a running deer at a hundred yards with a hand gun.'

He followed Jim into the building where Midian, an unpleasant sight with his unshaven face and blood-shot eyes, had arisen and was cooking breakfast over a small oil stove. He looked up at Jim.

'Trying to do a bunk?' he sneered.

'Trying to wash,' replied Jim. 'I suppose it's no use asking you for the loan of a piece of soap?'

'Gimme any back talk and you'll get soap all light,' snarled Midian ferociously.

Jim stepped up to him.

'See here, Midian, I didn't ask to be brought here, but now I am here I'll thank you to keep a civil tongue in your head. If you've any more remarks to make now's the time to make them. Mr. Butch will see fair play.'

Jim knew the risk he was taking, but he knew, or thought he knew, Midian's type. He was not mistaken, for after glaring at him for a few seconds the man's eyes fall.

'I don't want no trouble,' he said sulkily.

'And I'm sure I don't,' replied Jim cheerfully, as he took his seat on an old packing case.

The food, though rough, was plentiful. There was fried bacon, stale bread but good, butter in a tin and any amount of strong black tea. Jim, who had had nothing for nearly twenty-four hours, except the cup of tea overnight, which Butch had brought him, was desperately hungry and made a thoroughly good meal.

'Eat, hearty,' said Butch, with the first touch of humor he had yet betrayed.

'Just what I'm doing,' smiled Jim. 'I've got to stoke up to- day if I am to starve to-morrow.'

'I ain't reckoning you'll do a lot of starving,' said Butch drily.

'I'm not so optimistic,' Jim answered, as he cut another slice of bread. 'By the bye, how are you going to approach Mr. Tremayne?'

'We done that already,' Butch told him. 'They got the letter this morning and likely they're reading it this minute.'

'You certainly don't waste any time,' said Jim. But how do you get an answer? You can hardly expect the local postman to deliver to this address.'

'We got our postman all right,'; Butch answered. 'We'll hear to-night or tomorrow early.'

'And if you get the picture, I go?'

'Sure, you go. No one ever said as Butch Harvey failed to keep his end of a bargain.'

Jim fell silent. He was thinking hard. Knowing the Tremaynes as he did, he had very little doubt but that they would yield to Butch's blackmailing demand, and send the picture. Maurice was still in bed, and Nance and her uncle would be so horrified at the idea of their guest being a prisoner that all they would think of would be I his release.

His one hope lay in Pip. Pip for all his casual ways, had a backbone of good solid common sense, and could be trusted to do the sensible thing, and communicate with the police. For Jim did not believe that the police were as helpless as Butch made out. And they could enlist civilian help to beat the Moors.

The only other way of solving the problem was to make his escape, but that, for the present at least, was a pretty hopeless proposition. In the first place he was not fit for a hard run, in the second he had not the faintest idea which way to go, and there was the additional objection that Midian and Butch seemed never to let him out of their sight.

By the time breakfast was over the sun had broken through the clouds, and there was every prospect of a beautiful day. Midian took the dirty crockery out to the leat, to wash up, and Jim took advantage of his absence to tackle Butch.

'Will you take my parole, Mr. Harvey?'

'Parole—what's that?' asked Butch, puzzled.

'My word not to try to escape. You said I was to stay in here, but I'm hankering to be on the heather in the sun. After all,' he added with a smile, 'I couldn't do a bunk if I tried. I'm much too feeble.'

'And yet you was ready to fight Midian,' remarked Butch, with a sort of unwilling admiration.

'That was pure bluff,' admitted Jim.

A slow grin crossed Butch's hard face. 'I knowed that. Well, you're a gent, and I'll take your word. Only, if I whistles you come right in. You hear me?'

'I hear, and you have my word. I promise not to make any attempt to escape until after sunset.'

'And then you won't have a chance,' retorted Butch. 'You can go along out.'

Midian scowled at the sight of Jim outside, and he made no remark, and Jim was careful not to go far.

He lay down on his back in the nearest patch of heather and began thinking things over. But somehow the only thing on which his thoughts would concentrate was Nance's face, which rose as clearly before his mind's eye as if it's owner was standing in front of him.

'The sweetest girl I ever met, the sweetest I shall ever meet,' he murmured.

Bees hummed drowsily in the purple heather bloom, a curlew cried plaintively overhead, a soft breeze tempered the heat of the sun, and Jim drifted off into a land of dreams where for the time he forgot his troubles.

WHEN he woke the shadows showed that noon was long past. He

went to the leat and drank deeply of the ice-cold water and again

bathed his head. There was still an ugly lump where Midian's

brutal blow had fallen, but the dreadful ache had almost gone,

and he felt infinitely better. Jim was one of those Spartans

whose school-days had been in the time of the Great War. He had

learned as a small boy the art of keeping fit and had practised

it over since, with the result that he had practically recovered

within twenty-four hours from a blow which would have killed a

weaker man.

He went back to his nest in the heather and drowsed and lazed until about five o'clock, when a low, sharp whistle reached his ears, and remembering his promise he got up and came straight into the mine house.

'Someone coming,' Butch explained briefly. 'No, it ain't no flattie,' he added with a ghost of a smile. 'Most like it's one of our chaps, but I ain't taking no risks. You stay right here until I finds out.'

He called to Midian who was sleeping in the inner room, and gave him whispered directions, and the man went out. There was a long wait before Midian came back with an envelope, which Butch at once tore open. Jim's heart boat a little faster as he recognised Nance's writing.

Butch read it through slowly, then looking up saw Jim's eyes fixed on him.

'You don't need to worry,' he remarked. 'They ain't raising a mite of trouble. Soon as ever they're sure as we're the ones as really holds you, they're a going to give us the picture.'

Jim suppressed an angry exclamation. He was bitterly disappointed.

BUTCH was almost cheerful at supper that evening. He seemed to have taken, a liking to Jim, and began to tell him of certain adventures, rum-running across the Canadian border. He had acted as driver of powerful armoured cars which rushed straight through all barriers and a hail of bullets. His extraordinary disregard for human life horrified, yet at the same time fascinated Jim.

To do Butch justice, he seemed to, think as little of his own life as of those of others, and he mentioned quite casually that he carried the scars of five bullet wounds. 'But you can't go on with that sort of thing indefinitely,' said Jim. 'I thought boot- leggers saved their money and retired to houses with gold knobs on the doors and silver-fitted bathrooms.'

'I had a right nice packet saved two years ago,' Butch told him, 'but I got into a game one night and soaked the lot.'

He looked at Jim with a ghost of a smile. 'You don't need to worry. I don't reckon I'll starve.'

Jim did not think he would live to do so. It was much more likely that Butch's life would come to a sudden and violent end, and Jim found himself with an odd feeling of sympathy, almost with an odd feeling of sympathy, almost sorrow, for the outlaw. But this feeling did not interfere with his determination to escape if any chance to do so offered. He had no intention of the Memling Madonna falling into Sharland's hands if he could do anything to prevent it.

Butch sat smoking and talking until nearly midnight. He shared his tobacco with Jim, and even offered him a glass of whisky. At last he yawned and rose to his feet.

'Guess I'll turn in,' he said.

Jim's spirits rose, for Midian had been asleep for three hours past.

They fell again when Butch roused his confederate and ordered him to stand guard.

'Don't take no chances with him,' he ordered, with a nod in Jim's direction, and Midian, who was extremely sulky at being, waked from sound sleep observed that something unmentionable would happen to himself if he took any chances, while as to what would happen to Jim his language was still more luridly expressed.

Jim lay down and pretended to be asleep, but instead of sleeping covertly watched Midian. His one hope was that the man might drowse at his post. It was a vain hope, for Midian, seated on a packing case with his back against the door, filled and smoked pipe after pipe of coarse black tobacco. The worst of it was that Butch was sleeping in the same room, and Jim watched him look to the magazine of his pistol and place it in his pocket before lying down. Jim racked his brain for any plan for getting away, but could find none. He had no weapon of any kind, not even a stick, and even if there was any hope of successfully tackling Midian, the noise would certainly rouse Butch who, he knew, was a light sleeper.

Now and then Midian consulted a large silver watch which he took from his waistcoat pocket, and at last got up and crossing to Butch shook him awake.

'Four o'clock,' he growled.

Butch got up quietly, and glanced across at Jim. 'You might just as well have your sleep,' he remarked.

'How do you know I haven't been asleep?' retorted Jim sharply.

'I weren't born yesterday,' was Butch's calm answer, and Jim had to realise that a rabbit in a steel gin would stand as good a chance of escape as he. Yet he vowed to himself that, if these fellows did get the picture, he would somehow get it back again.

With this thought firmly fixed in his mind, he fell asleep and did not wake until the clatter of the frying pan told him that Midian was preparing breakfast, Butch allowed Jim to go out and wash in the leat, but watched him the whole time.

'It wouldn't do you any good to fun,' he advised quietly. 'And I'd hate to spoil your fishing with a bullet in your leg.'

Jim had nothing to say, for he was perfectly aware that his gaoler was not bluffing. He was equally aware that the man read his intentions like an open book.

Butch ushered him back into the mine house and helped him to food. He was kind, even courteous, yet Jim was certain that if anything went amiss and the picture was not delivered, he would keep his word remorselessly as to starving his prisoner.

'Who is bringing you the picture?' he asked, when breakfast was over and Midian outside, cleaning up.

'A fellow as I can trust,' was the dry reply.

'When do you expect him?'

'Some time before night.' He paused. 'You want your liberty today?'

'No,' said Jim sharply, and the other shrugged. 'Then you'll have to stay inside,' he said.

'You watch I don't get out,' retorted Jim, but Butch only smiled.

Jim had a deliberate purpose in what he had said, for a plan had been brewing in his mind for some hours past, a perfectly crazy idea, yet the only one that offered the slightest hope of preventing the Sharland gang from getting the picture. The plan depended for its success on his being left alone inside the mine house, and this was the chance he was waiting for. A pretty thin chance, for during the whole of the previous day there had not been a minute during which one or other of the men had not been hanging around.

Jim chucked himself down on his bed of fern and pretended to doze. Butch stayed outside and smoked in the sun, but Midian sat at the door with a pipe between his teeth and his unpleasant eyes fixed upon Jim.

And so the morning dragged by, the longest morning Jim had ever known. At the mid-day meal of bread and cheese, Butch chatted Jim in his dry way.

'Reckon you're sorry you didn't give me your parole or whatever you calls it,' he remarked.

'Be a sportsman,' said Jim. 'Give me a hundred yards' start, and you won't see me for dust.'

'I guess you wouldn't find much sport about it,' said Butch.

'I don't believe you could hit me at that distance,' Jim insisted, but Butch's thin lips tightened.

'I wouldn't advise you to try,' he said coldly.

Midian went to the leat, but came back quickly and said something to Butch in a voice too low for Jim to hear, and Butch got up at once and followed him outside. At the door he turned.

'I'm a-going to lock you in, Mr. Coryton,' he said curtly, 'and if you got any regard for your skin, don't try getting out.'

'How can I, without a pickaxe?' Jim retorted, but the moment the door was closed he was on his feet and hurrying into the inner room.

Jim Coryton was a Cornishman born and bred, and every Cornishman is a miner. Without being an expert Jim knew enough of tin mines to be fairly sure that an adit (or gallery) ran from the back of the mine building into the hill. He knew, too, that a tin mine has, as a rule, more than one adit. This one had certainly a second, for he had already spotted another opening higher up the hill and about a quarter of a mile from the mine house. His idea was to get into the near one and out by the far one.

This may sound a simple matter; but in point of fact it was nothing of tho sort. The mine had been closed down for years— certainly for half a century, and the odds were strong that the timbers supporting the roof of the interior galleries had long ago rotted away, allowing the roof to fall. It was even chances that Jim would find his way blocked before he had gone far. Even if it was not blocked, there would be rotten places where the slightest jar might cause a fall. In a working mine the miners wear a special hat to protect their heads from falling stones.

But the worst of it all was that Jim had no candle, and how was he going to find his way through a maze of dark, underground tunnels without light he did not care to think. The odds were all upon his getting lost and wandering into some blind alley in the heart of the hill, or falling down one of the winzes, the deep shafts which connect one level with another. He shivered a little as he thought of such a fate, lying crushed at the bottom of such a pit, with no possible hope of rescue or escape, yet even this fear did not alter or check his resolution.

Inside the inner room he paused. Sure enough, there was a black tunnel mouth at its inner end. A thin stream of water leaked out from the darksome depths and poured away through a drain in the floor. They—Midian and Butch—would know where he had gone, but even they would hardly dare to follow. Then he saw something else. A box of matches and a candle end lying on an upturned packing case. He snatched them up and plunged into the tunnel. The floor was deep, sticky mud, but he pushed on quickly. In a few steps the light had faded and he was squelching onwards through a darkness that might be felt.

THE roof of the gallery was so low that it was impossible for six-foot Jim Coryton to stand upright. He had to keep his head bent and to watch the roof where jutting rooks threatened his head. Many of these rocks had fallen and lay In the mud which covered the floor. This shone with a red iridescence from the tin ore with which It was charged; it was deep, sticky, and bitterly cold. The water trickling through it was very little above freezing point.

A hundred yards up, and Jim stopped and listened, but there was no sound of pursuit. He pushed on again. The air was heavy and charged with a harsh odour of decay, but it was breathable and his candle burned clearly. He came to a cross-cut and paused, undecided as to whether to turn up it, but decided to go further first. He did not go far, for presently he found his way barred by a roof fall, a block so complete there was no possibility of passing it. There was nothing for It but to turn back and take the passage to the left along the cross-cut. At any rate, It was the right direction, but Jim doubted whether it reached the other adit which he knew to be a good deal higher than the level which he had reached.

This cross-cut was drier than the main gallery, but the sides and roof were in very bad condition, and the floor littered with huge lumps of rock, among which it was difficult to pick his way. He had to go slowly. The cut curved slightly to the right, and the light of the candle fell upon another block. Jim's heart sank, for now there seemed nothing for it but to go back. He began to realise why there was no pursuit. Probably Midian knew that there was no way out, and he and Butch were waiting below, grinning in their sleeves at the knowledge that their prisoner would be forced to return.

The thought drove him frantic, and he went up to the barrier and examined it, and found that the fall did not quite reach the roof. There was a space a foot or a so wide between it and the gap from which the rock, had fallen. He saw that it would be just possible to crawl through this opening, yet the risk of doing so appalled him, for the whole roof above was so unstable it looked as if a touch would bring it down. He climbed carefully up the side, and looking over, saw the cut stretching away as far as his candle light carried. He saw, too, that it sloped upwards, and quite suddenly made up his mind that, come what might, he was going over. That fellow Midian would not have the chance to crow over him if he could help it.