RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Stones from the Sky," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1941, Dust Jacket

"Stones from the Sky," F. Warne & Co., London & New York, 1941, Book Cover

"Stones from the Sky," Title Page

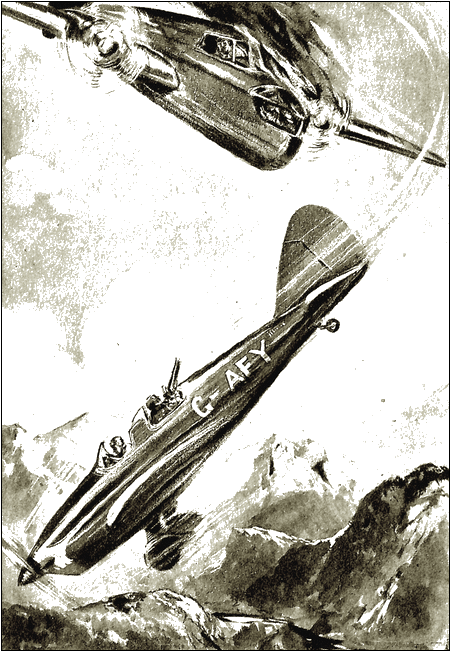

The Scene of the Story

Frontispiece

"He's done!" Jock shouted hoarsely. "Rister's done! We're safe!"

THE roar of the pampero thundering over the chimneys of the solidly built estancia muffled the crash, yet the sound was loud enough to make Jock and Ned Burney spring from their chairs by the fire and rush out of the room. At the foot of the stairs a great-framed old man lay flat on the floor of beaten clay. Jock reached him first and bent over him.

"He's stunned," he said. "Help me lift him, Ned."

The old man opened his eyes. "You boys can't lift me," he said curtly. "Call Julio."

"He's not in yet, Uncle John," Jock said. "He and Vincent are both out. Are you much hurt?"

John Garnett moved his big body cautiously. "I don't think there's anything broken," he answered, "but my left ankle is damaged. Marvel is I wasn't killed. I was only half-way down when I slipped."

"We can get you on to the couch," Jock said confidently.

Jock was sixteen but tall for his age. A bit slim still but already his muscles were hardening from the six months he had spent at the Tres Tortillas sheep farm in the heart of Patagonia. Ned, his brother, now just fifteen, was a different type, broad and stocky. He was nearly as strong as Jock and promised to develop into a very powerful man.

Between them they got their uncle on to the big leather couch in the sitting-room, then Jock peeled off the left shoe and sock and saw that the ankle was already swelling. He fetched hot water and began to foment it. John Garnett was usually a good-tempered man but now he grew irritable.

"I shall be laid up for a fortnight," he grumbled. "And where are Vincent and Vaz? They ought to have been in long ago, especially in this weather."

As he spoke there came the sound of the front door opening. A gust of wind shrieked into the house; then the door closed again with a bang and two people came into the room. One was a man of thirty, tall, swarthy, with blue-black hair and dark sullen eyes; the other a youth about eighteen years old with fair skin and hair, and pale blue eyes. His good looks were spoiled by a sharp nose, thin lips and a peevish expression. He was Vincent Slade, John Garnett's stepson. Vincent stopped and stared at his stepfather.

"What's up?" he demanded.

"Uncle John has had a fall," Jock answered. "He tumbled downstairs and sprained his ankle."

"Something is sure to happen whenever I leave the house," Vincent snapped. "I suppose one of you slopped water on the stairs?"

Jock looked Vincent straight in the face. "That's a rotten thing to say," he remarked.

Vincent's pale eyes glittered nastily. "Don't you dare talk to me like that," he snarled.

"Shut up, you two," ordered Mr. Garnett. "You're always bickering and I'm sick of it. Go and change and get your supper, Vincent."

Vincent gave Jock another ugly look, but he did not dare disobey his stepfather. He went out and Mr. Garnett turned to the dark-faced man.

"What kept you out so late, Julio?"

"We look for the horses, Señor. Some are gone."

Mr. Garnett made a remark that was not a blessing.

"Horses gone again!" he exclaimed. "Which?"

"The tropilla from the west pasture," Julio answered. He spoke quite good English, though with a queer foreign accent.

Jock cut in. "Our ponies were there. Are they gone, too?"

"I sorrow to say they have gone with the rest," Julio answered. "The wire has been cut. I have the belief that it is the work of the Wild Man.

"Stuff and nonsense!" retorted Mr. Garnett. "Everything that goes wrong is put down to the Wild Man. It is true there was such a man once, but he must be dead years ago. Now see here, Julio, those horses have got to be found."

"But assuredly, Señor. We start again in the morning. With permission I will now retire." His employer nodded. "Yes, get your supper and turn in."

Julio left and Jock went on fomenting the injured ankle.

"That's much better," said his patient presently. "Now I think I can get to sleep. Bring me pillows and blankets and my pyjamas. I shall stay down here until I am better."

Between them the boys made him comfortable, then Jock built up the fire for a pampero, coming out of the south across the plains of Patagonia, is as cold as a north-east gale in England. Before going up to bed Ned made a request.

"May Jock and I go after the horses with Julio, Uncle? If the old madrina is with them I can always catch her; then the rest will follow. Maria will look after you."

The old man nodded. "Yes, you two can go with Julio. But Vincent will stay at home."

Ned thanked him and said good-night, then he and Jock went up to their room.

"Vincent will be sick," remarked Ned as he began to undress.

"We shall be quit of him for a day, that's one mercy," Jock answered. "Ned, one of these times I shall lose my wool and punch the blighter."

"I believe you could lick him," Ned said. "And a licking is what he wants, the very worst kind. Funny how he hates us!"

"Not funny at all. He's jealous. He's afraid that Uncle is going to leave us some of his money."

"I don't want his money," said Ned, "but I would like a bit of land and some horses. It's a rum thing, Jock, but I'm getting fond of this country."

"I don't think it's rum. I like it, myself. It's lonely but it's a good life, and I've never been so fit as since we came here. I wouldn't care to stay here always, for I want to go to a decent university later on, but I'm game to make a home here."

"Good business!" said Ned. "Then we'll go into partnership and make a show of it."

Jock laughed. "It's not so easy as that, Ned. We want quite a bit of money to get started."

"We'll make it somehow," Ned declared as he got into bed. "Now we'd best sleep, for we'll have a hard day to-morrow. Those horses may be twenty miles away by morning."

"Wish I knew who cut that wire," Jock growled.

"Vincent, of course," Ned told him.

"Vincent! You're crazy. What would he do that for?"

"To spite us. Don't you remember, he told Uncle we couldn't break those ponies. He was furious because we got them properly tamed. That's why he's turned 'em out. He probably hopes we shan't find them again. If he and Julio had gone after them they never would have been found."

Jock drew a long breath. "Then that's why you asked if we might go."

"That's why," Ned said quietly.

Jock thought a while, then spoke again. "But Julio's coming," he said. "Do you think he'll try and put us off?"

"I'm jolly sure he will. He and Vincent are thick as thieves. But don't worry. Between us we can handle Julio. Now I'm going to sleep. Bye-bye."

The brothers were up before dawn next morning and were relieved to find that the gale had blown itself out in the night. As they had expected, Vincent was furious because he was not to go after the lost horses. But he did not dare to make a fuss. John Garnett's word was law at Tres Tortillas. The boys, watching Vincent, saw him slip out of the room and exchanged glances. They were quite sure he had gone to have a quiet word with Julio.

The sun was only just up when they started. Since their own ponies were gone the boys had to ride what they could find. Jock was mounted on an ugly bay called Horqueta, which means Slit- eared, and Ned had Overo, a stocky piebald with a queer temper and a nasty habit of cow-bucking. They took two pack-ponies to carry their tent and food.

Most people have the idea that Patagonia is a vast plain covered with grass, where countless sheep graze. This is true of the east coast, but inland it is very different. Here are great stretches which resemble Highland deer forests only, instead of bracken, the ground is covered with thorn bush and poison bush. Here and there are lagoons not unlike Scottish lochs, and almost everywhere the ground is broken by ravines called "canadones," some of them deep and dangerous. But there are no mountains until you reach the Andes far to the west, so that you can see to a tremendous distance. Almost always there is wind and overhead immense clouds sail in a pale blue sky.

Julio was friendly that morning—suspiciously friendly the boys thought. Both were watching him all the time. They suspected that he would try to lead them on a false trail but, if he meant to do so, he had no chance. The ground was moist and the tracks of the horses were plain.

The tropilla which had escaped numbered fourteen horses. In Patagonia each tropilla has a madrina or bell-mare who wears a bell around her neck and is followed by the others. She is so trained that she can be caught easily but is never ridden. The madrina of this troop was a particular friend of Ned who fed her with sugar. She would come at his whistle and he had no doubt that, if he could only sight her, he would soon have the whole lot in tow.

All the morning they followed the tracks. At eleven they stopped and Julio lit a small fire and brewed a pot of maté, South American tea made of the leaf of a sort of holly. The boys had come to like this drink and were glad of the short rest. Both were finding the paces of their half-broken beasts very trying.

The tracks led almost straight across the pampa, and presently Julio spoke.

"The horses are being driven. They have not stopped to graze. It is as I told the Señor. The Wild Man is behind them."

"Who is this Wild Man?" Jock asked.

Julio shook his head. "None knows whence he comes, but it is said that he is a white man who quarrelled with his brother and killed him. He was arrested and condemned to death but escaped and, in revenge, steals horses. Sometimes he kills them, but more often leaves them in some lonely spot."

"I don't believe a word of it," Ned whispered to Jock a little later. "If a mounted man had been driving the horses I'd have spotted his tracks. They'd have been deeper than those of an unsaddled horse. And the horses have stopped to graze. My notion is that we are not very far behind them."

"I hope you're right," Jock answered in an equally low tone, and just then Julio looked round suspiciously so that the boys said no more.

The sun began to sink and still no sign of the missing horses. A rainstorm swept up and Julio suggested camping in the shelter of a canadone where a small spring gushed out. The boys agreed and the horses were unsaddled, hobbled and left to graze. Julio lighted the fire while the boys pitched the tent. Julio put on the pot and made a "puchero," a stew of mutton and vegetables. This, with bread and maté, made their supper. Tired with a long day in the saddle, the boys got out their sleeping-bags and were hardly inside them before they were sound asleep.

Jock was the first to rouse. To his amazement it was broad daylight. He sat up and yawned. He felt curiously drowsy. Ned was still asleep and it took some shaking to wake him. When he did open his eyes he seemed half stupid.

"It's my head," he grumbled. "It aches."

"So does mine," said Jock. "Let's go over to the spring and wash."

They crawled out of the tent and the first thing Jock noticed was that there was no sign of Julio.

"He's gone after the horses," Ned said.

"He's precious late," growled Jock. "The sun's an hour high."

They went to the pool and the ice-cold water cleared their sleepy heads. Jock was the first to get back to the tent.

"Where are the pack-saddles?" he asked sharply.

Ned looked round. There was no sign of the packs or of the cooking-pots. He made a quick circle, examining the soft ground.

"The swine has cleared out," he told Jock. "He has drugged us, taken the horses and everything and marooned us."

"THE man's crazy!" Jock exclaimed. "What's his idea? What do you think Uncle John will say when Julio tells him he's lost us?"

"He doesn't mean to do anything of the sort," Ned answered. "He has five horses and grub for a week. He's going to clear out, and join some pal of his in the west."

"Then the sooner we get back and tell Uncle, the better," Jock said grimly.

Ned shrugged. "Easier said than done. We're at least forty miles from home, and it will take two days to get back afoot. Meantime we haven't a mouthful of grub."

Jock paled a little as the truth of Ned's words came home to him. Forty miles of rough, road-less country to cover and both were wearing high-heeled riding-boots. No food, no firearms, and the sleeping-bags too heavy to carry. He pulled himself together.

"It's a bad fix, Ned. But there's no choice. We'd better start."

Ned did not move.

"What about trying for those horses, Jock? I don't believe they're far. If we can find them we can ride back."

"But Julio will have collared them," Jock answered.

"I don't think so. Five horses are about all he can manage and I don't believe he'll delay to catch the rest. Seems to me it's worth trying."

"If we don't get them we shall be in a worse hole than ever," Jock warned him.

"It's just as you like, Jock," Ned said. "If you think best, we'll go home."

"If you think it's good enough we'll try it, Ned," he agreed. "But I wish to goodness we had something to eat before we start."

"We might get an armadillo," Ned suggested. "Keep your eyes open as you go." He paused. "If we don't see the horses before night we turn back," he added.

The morning was fine but there were clouds about. This was October, spring in the Southern hemisphere, and it was still cold. For the next two hours the brothers followed the trail of the wandering horses. Of one thing they were sure. Julio Vaz was not after the tropilla. There were no signs of his tracks. Then they came to rough stony ground where the trail was hard to follow. The stones were equally hard on their feet, and both boys wished devoutly that they were wearing walking-shoes. But the worst of it was lack of food. With every hour they grew more and more hungry and, although they saw several guanacos (wild llamas), there was no means of killing these swift and wary creatures.

By midday they began to feel desperate and Jock's heart sank as he thought of all the weary miles between them and home.

Ned spoke. "We'll go to the top of the next rise and, if we don't see the horses, we'll turn back. That suit you, Jock?"

"Anything you say," replied Jock wearily. "But how we are going to get home afoot beats me."

They toiled up the next ridge and as they reached the top Ned gave a yell.

"There they are!"

"Yes," said Jock, "but how are we going to reach them?" He pointed to the deep river which ran at the bottom of the valley. The horses had swum across and were feeding on good grass on the far side.

Ned refused to be discouraged. "We can swim, can't we? Come on, Jock."

Jock didn't like the look of that river a bit. True, it was not more than a hundred feet wide, but the current was strong and he well knew how bitterly cold the water was at this time of year. Yet there was no choice and he followed Ned's example and stripped. With their belts they strapped their clothes and boots on their backs, hoping against hope to keep them dry. Ned waded in. As he followed Jock heard his brother gasp. No wonder! The river was liquid ice. In a couple of steps they were out of their depth. Jock swam well but Ned was not so good, and when they neared the middle the strong current began to carry them both down-stream.

"Don't fight it," Jock called out. "Let it take you down. We'll find slacker water presently."

They struggled on. Suddenly both were caught in an eddy, and Jock saw Ned's head disappear. He made a grab and caught hold of something. It was the bundle of clothes strapped on Ned's back. Up came Ned's head, but at the same time the belt gave way. It was impossible for Jock to save it: it took all his strength to hold Ned, for the eddy was dragging them both down.

Jock was breathless, almost exhausted when he at last got out of the whirlpool. A minute later a swirl of the current flung them in towards the bank and he clambered up and dragged Ned to safety. He turned quickly to look for Ned's bundle. There was no sign of it.

"This is my fault, Ned," he said bitterly. Ned, stark naked, blue with cold, managed a laugh.

"You dear old ass. You save my life and then grouse about my togs."

"But you'll die with cold." As he spoke Jock got his own soaked coat from his bundle, wrung it out and flung it over Ned's shoulders. Ned refused to be discouraged. "Let's get the horses first, then we'll light a fire and warm ourselves. After that we'll ride home." He went towards the horses, whistling. Madrina raised her head, then turned and began to walk towards him. Ned held out his hand and the mare came up. She was within a few yards of him when two guanacos came tearing down out of a gorge in the cliff. Madrina snorted, whirled, galloped off and the whole tropilla went thundering away behind her. They went straight up-stream and within three minutes were out of sight.

"That's torn it," Ned said. Jock did not speak. At the moment he simply couldn't. Ned was far the more self-possessed of the two. "They won't go far," he added. "If you'll lend me your boots I'll go after them."

Jock looked at his brother. His skin was blue, his teeth were chattering. "You'll do nothing of the sort. Get under the cliff out of the wind. I'm going to light a fire."

Luckily Jock's matches were safe in a water-tight bottle; luckily, too, there was plenty of driftwood left by past floods. In a few minutes they had a fire going over which they dried Jock's clothes and warmed their frozen bodies. When the clothes were dry Jock shared them out. He made Ned put on his vest and pants, which were of wool, and he kept his shirt and trousers and waistcoat. His coat he forced on Ned.

By this time it was almost dark, so both set to gathering dry grass, of which they made a bed under shelter of a projecting spur. Then they piled up the fire and buried themselves in the pile of hay. They soon grew warm, but then they felt hungrier than ever. It was now twenty-four hours since their last meal and the hard walk followed by the swim had taken it out of them badly. They were too hungry to sleep.

"Those confounded guanacos!" growled Ned. "What made them stampede like that?"

"A lion most likely," Jock answered. He meant of course the puma, which they call the lion in the Argentine, though it is really only a sort of panther. "Try to sleep, Ned. We must save up our strength for chasing those horses in the morning."

"I'll try," said Ned, "but I'm so infernally empty it hurts."

Somehow the night wore through. The boys dozed uneasily, Jock getting up now and then to put fresh wood on the fire. Dawn came at last with a clear sky and a bitter cold air. Jock was scared to find how weak he was, and his heart sank at the thought of another day without food. Even if they found and caught the horses it would take all of ten hours to get back to the estancia.

Ned got up. "I'll have to have your boots, Jock," he said. "Will you wait here while I round up the horses?"

"There doesn't seem to be much choice," Jock replied.

"Buck up, old son," Ned said. "I'll get the horses and we'll be home before dark."

Ned was pulling on the boots when a droning sound made them both look up. A small dark object showed high in the southern sky and the boys stared, unable to believe their eyes.

"An aeroplane!" Jock gasped.

Ned wasted no time in talking. He grabbed up their hay bedding and flung it all on the fire, causing a great cloud of smoke to rise. Then he went scrambling up the bluff like a squirrel.

NED reached the top of the bluff and, standing there, frantically waved both arms.

The drone grew louder. The plane was approaching rapidly, but it was at least two thousand feet up and Jock's heart sank at the thought that its occupants would be unlikely to see him or Ned and that, even if they did, they would not realise their plight.

Now the plane was almost overhead. It was passing on. Of course the pilot would not come down. Why should he? Frantically Jock piled more and more grass on the fire. He heard a yell from Ned and looked up again. The plane was turning, circling. It was coming down. Jock shouted as loudly as Ned, then stood waiting.

As the plane came lower, he sprang away from the fire and waved his arms, beckoning and pointing to the flat pasture by the river. He saw a head over the edge of the fuselage, a head crowned with bright red hair. The man waved, then the plane came gliding down to make a perfect landing not more than a hundred yards from where Jock stood.

Forgetting his bare feet, Jock ran. As he reached the plane the red-haired man jumped out. He was short, broad, with a turned-up nose and little twinkling, bright blue eyes. He stared at Jock.

"Doggone if he ain't white!" he exclaimed.

"What did you think he was, Dan?" came a voice from the plane—"blue?" The speaker was a slim young man of about twenty-seven and, though he wore heavy flying kit, he had a spruce appearance.

"Red, Frank," retorted the man with the flaming head. "Didn't ye say as Injuns lived in these parts?" Just then Ned came up, panting. "And this one's white, too," added Dan, "though he ain't got much more clothes than an Injun."

"He lost his in the river last night," Jock explained. "We have only one suit between us."

Dan's eyes widened. "Gee, ain't you cold enough without going in swimming?"

"We had to swim," Jock explained, "after our horses."

"And you spent the night out in those togs."

"It wasn't the togs that mattered," Ned said. "It was want of grub. My brother and I haven't eaten since the day before yesterday."

Dan gave a horrified exclamation and plunged into the plane. He came out with a bag of biscuits and about a pound of chocolate and thrust them into the boys' hands.

"Ye must be clemmed," he said. "Eat now. After a bit we'll scare up a proper meal."

The pilot, too, turned back into the plane and brought out a fleece-lined coat. "Wrap that round you," he told Ned. "And presently I'd like to hear how you came to be in this fix."

Seated round the fire, the boys munched biscuits and chocolate and between bites told their story. The men from the plane were intensely interested.

"This fellow, Vaz, must be all kinds of a swine," said the pilot. "If I could spare petrol I'd go after him and machine-gun him. Now I'll tell you about ourselves. I'm Frank Falcon and this red-head is Dan Doran. We are employed by the Great Southern Oil Company to look for country where oil may be found. We flew for a place called Santa Inez, where we were told we should find petrol but, when we reached it yesterday, all we could get was twenty gallons. So we started north for Coronel. We shan't make it. We haven't juice for more than another hundred miles. Is there any at this place of yours?"

Jock shook his head. "We don't run to cars, sir. But if you will come to Tres Tortillas my uncle will be glad to have you stay until petrol can be brought."

"That would be fine," Falcon declared. "We'd best get on at once. We can pack you two in at the back."

Ned shook his head. "We have to get those horses, sir."

"For goodness' sake don't call me 'sir.' You make me feel about a hundred. Where are your blessed horses?"

"Not far," Ned assured him. "I can probably get them in an hour."

Falcon considered. "Dan, you ride. Suppose you go with Ned to fetch these beasts. Meantime Jock and I will scare up a hot meal."

Dan got up readily. "Sure, I'll go. Have ye had enough grub to keep your strength up, Ned?"

"I'm fine," said Ned, swallowing the last biscuit.

"Wait a minute," said Falcon. He went across to the plane and fetched a gun. "If you don't see the horses you may see those guanacos. And a steak would be just right for breakfast."

"It won't do to fire if the horses are about," Ned said.

"We will take the gun and chance it," grinned Dan, and with the double-barrel over his shoulder, set out. The river curved to the south about a mile from the camp, and beyond the curve was a plain with a small lagoon surrounded by thick brush.

"Wait a jiff, Dan," Ned said. "I'll climb the bluff and see if the horses are within sight. They might be in that brush." Without waiting for an answer he scrambled up. For a moment he stood at the top gazing at the brush, then came quickly down.

"The horses are more than a mile away, but I spotted something in the brush, two huemul."

"And what will they be when they're at home? Me, I don't savvy the Patagonian language."

"Deer, Dan," Ned answered with a laugh.

"Deer. Why couldn't ye say so instead o' libelling the poor beasts with fancy names? Let's be after them. The notion of a good, juicy steak of venison makes my mouth water." He started, then stopped. "Is it a good shot ye are, Ned?"

"Pretty fair," Ned agreed.

"Then take the gun, for I'm rotten."

Ned took the gun and the two started for the lagoon. Ned knew just where the deer were and the thought of venison appealed to him as much as it did to Dan. As he got near the place where he had seen the animals he bent double and walked with the greatest caution. Dan did the same.

Ned saw an opening in the brush. He stopped.

"Dan," he whispered, "go in and drive them out. Go as quietly as you can. They ought to come out this way and I'll have to be pretty close in order to get them with a charge of shot."

Dan nodded and began to steal forward on tiptoe. He was keen as mustard. Ned moved into cover behind a thick bush and opened the breech of the gun to be sure it was properly loaded.

From the depths of the scrub came a sound, a sound which made Ned's skin pringle. It was a snarl like that of an angry cat only multiplied many times. Quick as a flash Ned sprang into the opening. There stood Dan petrified and beyond him, with its head just emerging from a screen of leaves, a puma. Its wide mouth was open, showing yellow fangs, and its savage eyes glowed green as emeralds.

The puma as a rule is a rather cowardly creature and avoids man, but it is a curious fact that those of Southern Patagonia are much bolder than the pumas found farther north. And this beast had evidently been stalking the huemuls and was furious at being disturbed.

Ned saw that it was on the point of springing upon Dan, but Dan was between him and the puma and it was impossible to fire without the certainty of hitting Dan.

DAN stood stock still. Surprise rather than terror had petrified him. He had certainly never seen a wild puma; he hardly knew of their existence.

Ned did two things at once. He sprang forward and yelled at the top of his voice. The shout startled the puma and for an instant checked its spring. Ned's jump had brought Dan out of the line of fire. He let go both barrels and the two charges of shot struck the puma full in the face, blinding it.

Snarling hideously, it sprang. Its body struck Dan, knocking him down, but the beast passed over him, landing almost at Ned's feet. Ned had no time to reload. Hastily reversing the gun he raised it and smote the puma with the butt across the head.

The force of the blow was so great that the stock broke clean off, leaving only the barrels in Ned's hands, but the puma, stunned, lay sprawled on the grass. In a flash Ned dropped the remains of the gun, whipped out his belt-knife and drove it with all his strength into the beast just behind the shoulder. That did the trick. The long, tawny body quivered, then was still.

"Dan, are you hurt?" Ned asked anxiously, but to his great relief Dan was already scrambling to his feet.

"It's my feelings are hurt," Dan answered. "Gee, but that was a fool trick, standing right between you and the beast! If I'd had any sense I'd have laid down."

"Most people would have run away, but if you'd turned nothing could have saved you," Ned told him.

"Yes, I don't reckon I'd have had much of a show if that gent had got his teeth into me," he said slowly. "Ned, looks like you saved my worthless life."

Ned smiled. "Your turn next time, Dan. Now we'd best think of those horses."

"And we lost our supper," Dan mourned.

"Not a bit of it. Puma isn't bad eating."

Dan looked horrified. "I'd as soon eat a tom-cat."

"All prejudice," Ned said. "A chap told me that python flesh was one of the nicest things he'd ever eaten. But never mind the puma now. We must get those horses."

Luckily the horses had not been near enough to be alarmed by the gunfire and this time old Madrina came up quite quietly, to take the lump of sugar Ned had ready. He roped her, and the rest of the tropilla followed. Reaching the camp, Madrina was hobbled and she and the others began to graze quietly.

The first thing Dan did was to tell how Ned had killed the puma and the story did not lose in the telling.

Ned announced that he was going back to skin the puma and Jock, borrowing Dan's shoes, went with him. They brought back not only the skin but some of the flesh and, although Frank Falcon was as horrified as Dan at the idea of eating puma, set to cooking a joint over the fire. The smell of the roasting meat was so good that Frank was tempted to try it and freely admitted that it was very like veal, but Dan refused to touch it and contented himself with bully beef.

When dusk came they rigged up a comfortable shelter with brushwood cut with an axe from the plane and all enjoyed a thoroughly good night's rest.

It was arranged that the boys should start back early with the horses and that Frank Falcon and Dan should wait until late afternoon before leaving for Tres Tortillas.

"Uncle's laid up," Jock explained, "and it would give him a shock if your plane suddenly swooped down out of the sky."

"There's another reason," remarked Ned grimly as soon as he and Jock were out of earshot of the camp. "I needn't tell you what that is, Jock."

"Vincent," said Jock. "Yes, we don't want him warned of our turning up. It'll be worth something to see his face when we come riding in. But he will have some lie ready," he added curtly.

The day was exceptionally fine and warm and the horses gave little trouble.

They took an hour's rest at midday and ate some food with which Dan had provided them, and reached the ranch just before five. They turned the horses into their pasture, went to the house afoot, and slipped in the back way. Stout Maria, busy in the kitchen, stared at them in amazed delight.

"So you are safe! Ah, but I am glad! It is answer to my prayers."

"We're all right, Maria," Jock told her. "How is Uncle John?"

"I think his head more sore than his foot. He not like to lie up."

"And Vincent—where is he?" Ned asked quickly.

"He stay with your uncle. He very kind to him." Maria was no fool. She knew all about Vincent and liked him as little as did the boys.

"Julio's gone," Ned told Maria. "Stole our horses and everything else and left us marooned."

Maria raised her fat hands. "El maledito!" she exclaimed. "Then how you get home?"

Ned explained quickly and told her that the aeroplane would arrive soon.

The plump cook was all excitement. "Then I make feast," she declared and began bustling about.

At this moment the door of the kitchen opened and in stalked Vincent.

"Hot water, Maria," he ordered loudly; then he saw the boys, his mouth fell open and he goggled at them.

Jock stepped forward. "Surprised to see us, Vincent, aren't you?" he asked.

Vincent pulled himself together. "Why should I be surprised? Did you get the horses?"

"Yes, Vincent, we got the horses," Jock replied with a slight smile on his lips but none in his eyes.

Vincent opened his mouth to speak but checked himself.

"You were going to ask about Julio," said Jock politely.

Vincent grew angry. "Why should I ask about Julio? And what do you mean by looking at me like that?"

"Julio is your friend," said Jock. "I thought you might be anxious about him."

Vincent was certainly anxious, but more about himself than Julio. He tried to bluff it out. "I'm not taking any cheek from a kid like you," he said threateningly and came forward a step or two.

Jock did not budge an inch. "What are you going to do about it?" he asked sweetly.

Vincent looked anything but happy. This was the first time that Jock had openly defied him. He realised that he had to carry it through or take a back seat.

"Give you a good hiding," he said threateningly.

"Come on then," replied Jock.

Vincent came on. He was two years older than Jock, far heavier and stronger, but he had none of Jock's spirit and at this moment he was in a thoroughly worried state of mind.

Jock did not wait. He jumped forward and hit Vincent a crack on the jaw. Taken by surprise, Vincent staggered back and Jock, wading in, got in a second smack full on Vincent's beaky nose.

Nothing hurts worse than a heavy blow on the nose. The pain maddened Vincent. He flung his long arms round Jock, tripped him and the two went to the hard clay floor together. Jock was half stunned by the force of the fall and Vincent caught him by the throat and started to throttle him.

Maria screamed and Ned took a hand. He grasped Vincent by the collar of his coat and dragged him off Jock. And just then the back door opened and in walked Dan, followed by Frank Falcon.

"Looks like Saturday night in the Bowery," remarked Dan. "What seems to be the trouble?"

Vincent struggled to his feet. His nose was streaming, his coat was split, his hair on end. He looked not only a wreck but a fool.

"Who are you?" he demanded hoarsely.

Ned answered. "This is Mr. Falcon, and this is Mr. Doran. They helped us out when your friend, Julio Vaz, marooned us. They know all about you, Vincent, so it's no use telling them lies."

For once Vincent could find nothing to say. He turned and flung out of the kitchen.

"COME and be introduced to Uncle John," Ned said, and led the way to the front room. John Garnett was sitting in a big armchair with his damaged leg on a stool.

"What's all this infernal noise?" he began angrily as Ned came in, then he saw the strangers and pulled up short.

"These are Mr. Falcon and Mr. Doran," Ned said. "They helped us get back the horses after Julio cleared out. Jock and I asked them to stay the night. We thought you would like to see them, Uncle."

John Garnett was the most hospitable of men.

"I am glad to see you, gentlemen," he said. "As the Spaniards say, my house is yours. But I mean it and they don't—always."

"That's a fact, mister." Dan grinned. "Guess I've paid a heap of dollars for houses I was told were mine."

John Garnett chuckled. "Sit down," he said. "And I'm mighty obliged to you for helping the boys. But what was Julio doing?"

"Making tracks due west with the five horses, Uncle," Ned told him.

John Garnett stared. "Are you crazy, Ned, or didn't I hear you right?"

"You heard all right, Uncle," Ned said, and proceeded to explain exactly what had happened.

John Garnett was terribly upset. Julio had been with him for years and he had trusted the man.

"I can't believe it," he muttered.

Frank Falcon took up the story.

"It's true enough, sir," he said. Then he went on to tell how Jock had saved Dan from the puma and this pleased Jock's uncle as much as Julio's treachery had disgusted him.

"If we had had petrol we'd have gone after this horse thief, Mr. Garnett," Frank went on. "The trouble is that we are almost out of spirit and we are wondering where and when we can fill up again."

"I have none," said John Garnett. "Since we have no roads a car is no use to us. I could send a waggon to Santa Cruz, but it would be three weeks or more before it could do the double journey. But we'll talk of this later. Supper will be ready pretty soon and you'll want a wash. Jock, show our friends to their rooms."

Half an hour later the party sat down to a most delicious "puchero," which is a kind of Irish stew, piles of freshly cooked tortillas (a sort of pancake), an apple-tart served with plenty of cream, cheese, home-made biscuits and excellent coffee. Maria helped to serve the meal and smiled all over her fat face at the compliments paid her by Frank and Dan.

"Gee!" said Dan at last. "I ain't ate a meal like this since I left God's country."

Maria looked puzzled. "Does the Señor speak of Heaven?" she asked.

Frank chuckled. "His heaven is the United States, Maria. That's what Americans always call it."

Jock and Ned had been amused to see how nicely Vincent had been behaving at supper. In spite of the fact that his face was a bit lop-sided, the effect of the fight, he had been quite polite to the boys as well as to the visitors. But they noticed also that Frank and Dan, though equally polite, were not specially cordial to their host's stepson.

After supper the boys helped Maria to clear the table. To their surprise Vincent took a hand. In the kitchen he spoke to Jock.

"Sorry I got shirty," he said, "and thanks for not saying anything to Dad about it."

"That's all right, Vincent," he answered, and for the time no more was said.

When they went back into the living-room John Garnett and Frank Falcon were deep in discussion. John Garnett beckoned the boys across.

"Mr. Falcon wants to make a trip to the west, over towards Lake Argentino," he said. "He talks of renting horses from me and making the journey on horseback, while he waits for petrol for his plane. He has asked me to let you boys go with him."

Jock felt like yelling with sheer delight.

"That's jolly good of him," he said, "but can you spare us, Uncle?"

Uncle John chuckled. "Polite, aren't you? You know you and Ned are aching to go."

"Of course we are," said Ned frankly, "and I don't believe you'd have told us anything about it, Uncle, unless you'd made up your mind to let us go."

Again the big man laughed. "You're right, Ned. You and Jock did a good job, getting back those horses, and this is your reward. Now you'd better go to bed right away for you'll have a busy day to-morrow, getting things fixed up for this trip."

The brothers were only too glad to turn in after their gruelling day. They were too tired even to talk and, once in bed, neither moved until Maria roused them at seven next morning. Ned was up first and went to the window to look out.

"Another fine day. What luck!" he exclaimed. Then suddenly he thrust his head out, and looked up at the sky. "They've got the plane out!" he exclaimed. "That's funny. I thought they hadn't any petrol left." Jock joined him and Ned pointed upwards. High above a plane winged across the blue. For a moment or two both boys watched it, then a door opened below and, to their amazement, they saw Frank Falcon standing in the yard. Ned shouted at him.

"Someone's got away with your plane."

Frank looked up sharply. "Our plane. Where? What do you mean?"

"Up there," Ned answered, pointing.

Frank looked up and both boys saw his startled expression.

"But it can't be ours," he replied. "There was hardly an inch of petrol left in the tank." He paused a moment, staring at the plane which was winging rapidly south. His face cleared. "It's not ours at all. It's Max Rister."

"Who's he?" Ned demanded.

"I'll tell you at breakfast. Hurry up."

Hurry they did. In less than ten minutes the two were down. Breakfast was on the table and the rest of the party already seated. Uncle John was with them. His ankle was so much better that he could get about with two sticks.

"It was luck your spotting that plane, Ned," Frank said. "I knew that Rister was on my track but I hadn't the faintest idea where he was."

"Who is he?" Ned asked.

"My hated rival," Frank answered with a laugh. "He's trying to beat me to the oil, if there is any."

"A German?" Ned asked.

"Calls himself American but that, I think, is camouflage."

"Will he have seen your plane?" Jock asked.

"Sure to," said Frank.

"But now he will know where you are."

Frank laughed. "That's just what he won't. Before we leave we are going to hide the plane. Her wings fold and your uncle says we can get her into your big barn. The last thing that Rister will be expecting is that we should go off prospecting on horseback."

"Then Rister will be beat!" exclaimed Ned.

"I hope so. It looks to me as if he would be flying all round Patagonia, looking for a plane instead of searching for an oil- field."

"He won't get any news out of us if he comes here," said John Garnett forcibly. "But tell me, Falcon, do you expect to find a new oil-field?"

"I don't expect, Mr. Garnett, but I have hopes. Oil has already been found in Eastern Patagonia but in no great quantities. There is still plenty of unexplored land in the west. That's where we are going."

"I can't imagine how you find oil," Mr. Garnett said. "You can't carry boring tools in a plane."

Frank Falcon smiled. "You certainly can't. But oil-seekers can learn a lot from the lie of the land and the geological formation. There is coal to the west. There may be oil, too."

"I wish you luck," said the other, "but even if you do find it the land doesn't belong to you."

"That's the rub. We have to get a concession. But the Chilean Government is better to deal with than some other of these South American republics."

Breakfast was soon over and all got to work. They wanted at least a dozen saddle-horses and as many pack-animals. Then stores for the journey had to be made into packs. Luckily there was plenty of food at the ranch for, being so far from a town, John Garnett kept large quantities of such things as flour, sugar, salt and coffee in his storeroom. The plane was put away in the barn and by night everything was ready.

Next morning dawned windy and cloudy. Breakfast was at six and by seven all were ready for the start. Frank Falcon took the boys aside.

"I've got a bit of news you won't like," he told them. "Your uncle has asked me to take Vincent. I couldn't refuse, so he is coming."

"Didn't I know it?" remarked Ned grimly.

"There's no need to worry," Frank said. "I shall keep an eye on him. You may take it from me there won't be any trouble."

"All the same I'll bet there will be," Ned said to his brother as Frank hurried off. "Vincent isn't coming with us because he loves us. He'll upset our apple-cart if he gets half a chance." He stopped short as a yell came from the yard.

"Stop it, you brute. Hold your head up. I didn't ask you to dance."

"It's Dan," said Jock, as he ran, followed by Ned.

As they reached the yard they saw Dan on the back of a big black horse with a white blaze on its face. The brute was bucking savagely and Dan, no rider, but plucky as they make them, was grabbing the saddle-peak with one hand while with the other he tugged at the reins.

"It's Picaso," panted Ned as he ran. "Who let him get up on that brute?"

Ned ran straight for the pitching horse, but it whirled away from him. For an ugly moment it looked as if it would crash straight into the heavy wooden fence, in which case Dan would be badly hurt if not killed. Then Bartolo, one of the gauchos, appeared on the far side with a rope. He spun the loop which fell neatly over Picaso's head. The horse, well aware that this meant a throttling if he resisted, pulled up short and stood quietly while Dan slipped out of the saddle.

"Who told you to get on that beast?" demanded Ned.

Vincent came up.

"I'm so sorry. It was my fault. I told Doran that his horse was ready saddled, and so it is. But Picaso was nearest and he thought it was his."

Ned bit his lip. He knew very well that Vincent was lying, but what could he say?

Dan grinned. "Guess I got kind of mixed," was all he said.

THE horse chosen for Dan was Rosado, a quiet old roan. Jock had Alazan, a chestnut, and Ned his own sturdy pony, Tostado. Picaso was to be ridden by the gaucho, Bartolo, who had been told off by John Garnett to accompany the party. Picaso was what is called a "manero," a spoiled horse, but he was immensely powerful, could go all day and Bartolo could ride anything.

Presently they were all in their saddles and the boys waved good-bye to their uncle as they rode away across the wide pampas. They headed south-west, for Frank wanted to explore the wild country around Lake Argentino. So far as he knew, it had never been prospected.

It was the first time for years that Dan had been in the saddle and Falcon had not ridden much since leaving England, so they made a short day of it and camped early. After making camp the boys went out to look for game, but all they got was an armadillo. It was the first Dan had seen and he was much interested in the queer scaly beast. He was still more interested in helping to eat it, for its flesh was like chicken.

Next day they did thirty miles. The weather was good. Of course it blew, but there was no rain and it was not too cold. Dan, having got over his saddle soreness, began to enjoy it and vowed that this sort of travelling beat flying.

The boys, too, enjoyed the trip, but they would have enjoyed it a great deal more if Vincent had not been with them. Vincent was on his best behaviour. But neither Jock nor Ned had the least idea of the plan that was hatching in the mind of their uncle's stepson.

Bartolo was a very different type from Vaz, a stolid, rather stupid fellow, but a wizard with horses. The boys were not afraid of Vincent getting hold of him, for he was not the sort to take bribes.

During their journey they lived on the country. Frank Falcon, a first-class shot, killed several guanacos and deer, so they had plenty of fresh meat. Twice the boys found nests of the rhea, the South American ostrich, and the eggs made excellent omelettes. Then there were cavies, animals about the size of a hare, not bad eating, and in the vegas (swamps) they found wild duck which made a pleasant change of food.

It took three weeks to reach Lake Argentino, which is one of the wildest places in the world. It covers an area nearly as large as Buckinghamshire, and on all its hundred miles of shore there is not a house or a human being. Dan Doran pulled up on the top of the bare bluff above the lake and gazed at the grey-green water which rolled in long waves under the drive of the ever- lasting wind.

"It must be the last place God made," he said solemnly.

Ned shivered slightly. "It's certainly the loneliest." He pointed to the west where a vast bare slope ran up to a black forest of pines and above rose range upon range of hills, each higher than the last till the tops were crowned with everlasting snow.

"The Andes, Dan," he added.

Frank spoke. "We'd better camp here, Dan, and spend a few days prospecting. But if you ask me, the ground's more likely to hold gold than oil."

A river ran into the lake about a mile away and there was good grass along the banks. They camped under shelter of a high bluff close to this stream and were cooking supper when there came a distant rumbling.

"Il tremblor," muttered Bartolo looking scared.

"Earthquake, he means," Jock explained to Dan. They waited, but the sound passed and the ground did not quiver.

"It wasn't thunder," said Frank. "I wonder what caused it?"

The days were long now and they ate supper by daylight. They had just finished and were clearing up when Dan gave a startled exclamation.

"What's up with the river?" he asked, pointing at the stream. They all stared, amazed, for the river was running down as if the water had been shut off at the source. Rocks which had been hidden were showing their blunted heads above the water and in the shallows the bed was almost bare. Leaving the dishes, they all hurried down to the edge of the stream. It was still falling, and in a few minutes was reduced to a trickle.

"This is a plumb crazy country," Dan growled. He walked on to a bed of wet sand and began stirring it with his fingers.

"Good chance to see if there's any gold," he added. "Fetch me a pan, Ned. I'll wash a bit of this stuff."

Ned brought a pan and Dan filled it with sand and gravel and started spinning it. They were all standing round him when Ned heard a dull roar and looked up.

"Run!" he yelled. "Run for your lives."

A wall of water six feet high was thundering down the gorge, coming at the speed of a galloping horse, and but for Ned's timely warning some of them would have been drowned. They reached camp breathless, and as they watched the flood roll past Frank spoke.

"Glacier," he said. "I ought to have known. That rumble we heard was ice breaking off the end of a glacier high in the hills. It blocked the river until the water pounded up high enough to break the barrier."

"I guess you've got it," said Dan. "But I tell you right now I ain't hunting gold any more in that crazy stream."

They finished tidying up, and when dusk came all turned in.

Usually they all slept right through till dawn, but on this night Ned was roused by a brilliant light flashing in his eyes. He sat up and stared. The light was in the sky. A great ball of fire was rushing silently across the heavens exactly overhead.

His yell roused the others, and all jumped up in a hurry. The light was almost as brilliant as the sun. It completely extinguished the stars and its glare showed up the whole valley of the river. The river itself was a fiery flood.

Suddenly the ball burst into three pieces, which disappeared over the top of the western forest, but for a few seconds the glare still lit the sky with a lurid reflection. While the watchers still stood in silence there came a big shock like an earthquake. The solid rock beneath the camp trembled and small pieces of stone fell from the bluff. Then, some moments later, came a sound like the bursting of a great bomb at a distance. Dan was the first to speak.

"I told you this country was crazy," he muttered.

"Nothing to do with the country," said Frank briskly. "That was an aerolite, a meteor, and by far the biggest I ever saw. What's more, it fell only a few miles away. It dropped in the hills to the west."

"Can we go and look for it?" put in Ned.

"We certainly will," said Frank. "Museums pay well for meteors."

"But won't it be buried ever so deep?" Jock asked.

"That's what I'm afraid of," Frank answered. "All the same it will be worth visiting the scene of the fall. You'll see some funny effects, if I'm not mistaken."

But neither Frank Falcon nor any of the others had the least idea of what that meteor would mean to them.

THE glow in the hills to the west increased and flung a ruddy reflection against the night sky. The snow-peaks in the distance reflected the glare.

"The forest's afire," Ned said.

"Not much wonder," Frank answered. "When that big meteorite fell in Siberia thirty years ago it smashed or burnt out more than a hundred square miles of forest. Lumps of stone hitting our atmosphere at twenty miles a second are liable to get a bit heated by friction before they reach the earth."

"Where do meteors come from?" Ned asked.

Frank shrugged. "The big ones are supposed to be pieces of a planet which went bust. They say Jupiter was the culprit. Ceres and the other asteroids are bits of the broken planet and some of them are 500 miles in diameter."

Ned whistled. "If one of them hit us it would make trouble."

"But they won't. They circle the sun like planets." Frank glanced at the sky again. "There's a proper fire up there. Look at the smoke."

"It's cloud," put in Jock, and just then a vivid flash of lightning blazed across the mountains and was followed by a crashing peal of thunder.

"You're right, Jock," Frank said. "That smash-up has let loose so much heat that it's caused a thunderstorm. We'll get a dowsing pretty soon. Better get everything under cover."

They did so and had hardly finished before the rain came down in a solid sheet. It beat off the ground in foam and made a sound like a great waterfall.

"This'll put the fire out," Ned said to Falcon.

"And a good job for us," agreed the airman. "We might have had to wait a week but for this rain."

The storm lasted for nearly two hours and, when it was over, the river was coming down in thundering flood. But when the sky cleared there was no glow in the hills and no smoke either. The party got about three hours' sleep but all were up at daylight, desperately keen to visit the scene of the great fall.

Bartolo was left to look after the horses and his face showed his relief. The Indians of the pampas will not go near the mountains. They think they are "encantado" (enchanted), and Bartolo had enough Indian blood to share this superstition.

The meteor fall had frightened him badly.

They took food, rope and digging tools and, as the sun rose, all five were tramping up the valley. It was not easy going, for small torrents were still pouring down the cliffs on either side and had cut deep gullies in the wet earth.

Two miles up, the valley narrowed so that there was no space to walk between cliff and river. They had to climb the steep bluff, then found themselves on a great slope covered with coarse grass, leading up to the forest above. It was not until they came to the trees that they saw the first sign of damage. The forest looked as if a cyclone had struck it. Quite half the trees were uprooted and all lay with their tops pointing to the west.

"That was the blast of air from the fall," Frank explained. "I expect we shall have a job when we get nearer."

Ned pulled up. "What's that?" he asked, pointing. Some large animal lay dead in a hollow and as they hurried towards it they saw it was a horse. It had been killed by a large branch falling on its head.

"Rum place to find a horse!" said Jock.

Ned, who was examining the dead animal, looked up sharply. "It's the horse Julio Vaz was riding. I'd know it anywhere. And see, there's our brand on it."

Frank Falcon's eyes widened. "What would Vaz be doing up here?" he asked in surprise.

"That's what I'd like to know," Ned said.

"The horse may have got away from him and strayed up here," Jock suggested.

Ned shook his head "Not likely. Julio's the last man to lose a horse."

"Let's see if there are any signs of the other horses," Jock said. But they found nothing else. The rain had washed away all tracks and, after a thorough search, they gave it up and went on.

It was lucky they had come afoot, for no horses could possibly have got through the fallen forest. Even afoot it was hard and exhausting work; the next mile took them nearly an hour to cover. The farther they got the more trees were down. Then all of a sudden they found themselves on the rim of a deep, bowl-shaped valley and one look was enough to tell that they had reached the scene of the fall.

At the bottom were two enormous pits and on the opposite slope a third. The pits were like bomb-craters, only no bomb that man ever made could have torn such chasms in rocky soil. All around the devastation was complete. Every tree that had grown on the sides of the valley was down. They were piled like matches from an upset box. Where the slopes were steepest great landslides had fallen, leaving acres of bare rock beneath which broken trees lay in fantastic heaps.

For a while no one spoke. The scene fairly scared them. Even Vincent had gone rather pale and was evidently impressed. Dan was the first to speak.

"Looks like one of them craters on the moon must look like," he remarked. "And I guess it's going to be about as hard to get down into."

"We shall have to go very carefully," Frank told them. "There may be gas at the bottom."

"That's a fact," Dan agreed. "Say, Frank, I don't gas very easy. I'll go first at the end of a rope and you can pull me out if I get a lungful."

Without the rope they would never have got down at all and, as it was, the job was about as ugly and dangerous as it could be. The tree-trunks slid and rolled as the party tried to cross them and it was hard to find even a stump firm enough to hold the rope. When they got near the bottom Dan tied the rope round his body and went slowly forward. The rest watched anxiously but he seemed none the worse. When he got to the end he turned.

"No poison here," he told them. "You can come along quite safe."

The nearest crater was about two hundred yards away. It was just like an enormous shell-hole and was surrounded by a regular wall of broken rock flung up from the depths. Much of this was fine powder which the rain had changed to sticky mud. When they looked over the edge they saw a sheet of dark muddy water lying about twenty feet below the rim. Frank shook his head.

"We'd need a motor pump to clear that, Dan," he said.

"And where's the water to go after we've pumped it out?" asked Dan. "I guess it'll be some job to recover those sky stones."

"May as well have a look at the second hole," Frank suggested.

This second hole was nearly a quarter of a mile from the first. As they came near it Ned said to his brother:

"Do you notice anything, Jock?"

"Yes, a queer smell."

Frank and Dan had evidently noticed it, too. They were both hurrying forward. They reached the edge and peered over.

"They've spotted something," Ned said.

Frank overheard and turned. "You're right, Ned. Look down and tell me what you see."

"A worse looking lot of stuff than there was in the first hole," Ned answered. "The water's all covered with black scum."

"And what do you think that scum is?" Frank asked.

Ned looked at him and saw that his eyes were very bright. Light dawned on him.

"Oil?" he gasped.

"Yes; oil," Frank answered. "You can smell it as well as see it."

"You mean that the meteor has struck an oil well?"

"Just that, Ned, but don't get excited. It may be only a small deposit; it may be poor quality. Even if it's good it's in such a place it may not be workable."

"Ah, don't be crabbing it all," Dan said. "Let me down and I'll take a sample."

Frank had brought corked bottles and Dan took several of these and was let down into the pit at the end of the rope. He spent some time collecting samples of the oil which he skimmed from the top of the water.

"What's it like?" Ned asked eagerly after they had hauled him up.

Dan grinned. "That's more than anyone can say till we've tested it."

Ned's face fell. "Do you mean you'll have to take it back to a laboratory before you know what it's like?"

"No farther than the camp," Dan told him. "We have the stuff with us."

"Then let's go back at once," said Ned.

"Don't you want to look at the third hole?" Frank asked.

Ned glanced at the slope opposite where the third fragment of the meteorite had struck.

"It will mean the very dickens of a climb," he said. "Can't we leave it for another day? The meteorite won't run away."

Frank nodded. "No, it won't run away," he said drily. "It would probably take a gang of men a week to reach it and a steam crane to lift it. All right. Let's get back to camp."

Before starting he and Dan packed the bottles and test tubes in cotton wool. The care they used impressed the others, especially Vincent. Jock, watching Vincent, wondered what thoughts were working in his crooked mind.

All were pretty weary when at last they reached camp.

Tired as they were, Frank and Dan set to work at once on their bottles, but they worked in the tent and would not allow any of the others to watch. The boys saw that this annoyed Vincent, but he did not say anything.

Supper was just ready when Frank and Dan came out of the tent. Ned was waiting for them.

"What's the oil like?" he demanded.

"Fair," allowed Frank and that was all he would say. But Ned and Jock both had an idea that he would have said more if Vincent had not been there.

IT was still broad daylight when supper had been eaten. After they had washed up and made all tidy for the night, Frank got up and strolled down to the river. He did not ask the boys to come with him, but both were sure that he meant them to follow. They did so, but Frank did not speak until they had rounded a bend in the valley below the camp and were well out of sight of it. Then he pulled up and looked round carefully.

"It's all right," Ned told him. "Vincent didn't come. All the same I jolly well know he wanted to. He smells a rat."

"And so do you chaps," said Frank with a smile.

"We sort of thought you were pleased about something," Ned told him. "But it was really Dan's face that gave the show away."

"Dan never could keep a straight face," Frank replied. "And what do you think we did find?"

Ned shook his head. "I haven't any real notion, but I believe the oil was better than 'fair.'"

"No," said Frank. "The oil is only fair in quality, and I can't say whether it's worth drilling to see if there's a big supply. All the same we did find something and it's worth a lot more than oil. Can't you guess?"

"Not in a month," Ned answered.

"Nor I," said Jock.

"Did you ever hear of helium?" Frank asked them.

"It's a gas next lightest to hydrogen," Jock replied. "It's used for filling airships."

"Is it very valuable?" Ned asked.

"At the moment," said Frank, "it's one of the most valuable commodities in the world. You see it is what is called an inert gas. It doesn't mix with air and explode like hydrogen. And the Germans are mad for it, to fill their new Zeppelins. The only source of supply at present is from oil-wells in the south- eastern part of the United States. And the States won't sell to Germany because they believe the airships might be used for purposes of war."

"Then we mustn't let a whisper get out."

"It will be just too bad if there is any leak," Frank said. "I'm more than half sorry that you boys know anything about it, for it's putting you both in a dangerous position."

"I think it was jolly nice of you to tell us," Ned said stoutly. "You know we are with you from the word 'Go.'"

"You couldn't well have kept us out," said Jock with a smile. "Ned and I both spotted something was up."

"Yes, and I'm very much afraid that Vincent suspects something," Frank said seriously.

"But he doesn't know anything," returned Ned. "And he probably never heard of helium."

"I hope he hasn't," Frank said. "For good or ill you boys are now partners with Dan and myself, and Dan agrees that you are to have a share in the reward. Money's always useful and a bit of capital might give you chaps a good start in life. Didn't you say you wanted to go to college, Jock? You can't do that without money. And you talk of a sheep farm, Ned. That, too, means capital."

"We have to market that helium first," Ned said slily. "What are you going to do first, Frank?"

"Get back to Tres Tortillas as fast as the horses can take us. The petrol should be there by the time we arrive, and we shall fly straight to Valdivia and get our concession. Once we have that signed and sealed we can snap our fingers at Rister."

"Right!" replied Ned. "Then let's get back to camp."

They found that Vincent had already turned in and was asleep, while Dan was getting ready for bed.

It was a fine night and there was no need to crowd into the stuffy tent. Vincent was sleeping in it, but the rest arranged their sleeping-bags in the open and were soon deeply asleep.

An hour passed. By this time it was quite dark except for the stars. There was a movement in the tent. Vincent peered out. He was fully dressed. For a minute or two he stood quite still, listening to the steady breathing of the others. When he felt sure that they were all sound asleep he crept out and, moving silently as a cat, walked east along the base of the bluff.

He came to a ravine and made his way up it to the slope above. The sky was clear and the stars gave light enough to find his way. He walked some distance up the slope until he came to a clump of brush. Here he groped about until he had collected a couple of armfuls of dead wood. He made the wood into three small piles and lighted them.

There was little wind and three separate flames shot up. Vincent fed them with dry sticks. Time passed and nothing happened. Vincent grew annoyed.

"The fool! I suppose he is asleep," he muttered angrily, and as he spoke a tall shadow loomed above him and Julio Vaz said harshly:

"He is not a fool, Señor, and he is not asleep."

Vincent had the sense to apologise.

"I am sorry, Julio. I have been waiting a long time and I was getting nervous."

"And I had a long way to come," retorted the gaucho.

"You are here. That is the main thing," Vincent answered. "It was luck spotting that dead horse of yours. I knew you would be travelling in this direction, but I hardly hoped to find you. What made you clear out?"

"I had done that for which you paid me. Do you think that I was coming back to the estancia to face the Señor Garnett? I have friends in the mountains," he added significantly.

"So you told me before. Well, you know now that those brats found their way back. They are now in higher favour than ever with my stepfather."

"They are not fools," said Julio briefly. He paused, but Vincent did not speak. "Why have you signalled me?" Julio asked. "What now do you require of me? I do not work without money, Señor Vincent."

"Money," Vincent repeated. "There's more money to be made than you ever saw in your life. Those men found oil yesterday."

Julio frowned. "Oil—petroleum. But where?"

"In the hole made by that stone from the sky. It's a big find. They're very excited about it."

"But it is theirs, not ours," Julio answered. "And it would be difficult to kill them all."

Vincent shivered slightly. He was well aware that this big dark brute would cut any number of throats if he were well enough paid. He spoke quickly.

"There's no question of killing them," he said forcibly. "Listen; They do not own this oil find until they have a concession, a licence from the Government of Chile. At the same time there is another party looking for oil. They are Germans. Their chief is a man named Max Rister. He will give much money for news of this oil-field. Your job is to find him and bargain with him."

Julio frowned again. "But where is he?" he asked.

"At Santa Cruz."

"It is a great distance," Julio said, frowning.

"Barely two hundred miles. You can do it in a week."

"I should require a hundred dollars for such a journey."

"A hundred! He will give you five hundred, if you ask it." A covetous gleam showed in the eyes of Vaz.

"But this Señor Rister, he may not believe what I say."

Vincent took an envelope from his pocket and handed it to the other.

"Give him this letter and there will be no doubt. Now are you satisfied?"

"I will go," Julio answered.

"Good. And when Rister has paid you, you can go by ship up the coast to Buenos Aires. You will enjoy that, Julio. It is a fine city with all kinds of amusements."

Julio's eyes gleamed again. "I will go," he repeated and, turning, strode away into the night.

Vincent hurried back. He had taken the first step to spoke Frank Falcon's wheel, but he was not altogether satisfied. He would much prefer to have gone himself to see Rister, but that, of course, was impossible. He would have to lose any share of the oil, yet after all what did that matter, so long as he got Tres Tortillas? It was a very valuable property, and his stepfather was an old man who would not be likely to live much longer.

He crept back into camp as quietly as he had left and felt certain that none of the others had any idea that he had been away.

Next morning the horses were gathered, the packs made up, and soon after sunrise they were all on the road.

FOR two days they travelled as fast as they could press the horses without overtiring them. Vincent, aching and saddle-sore, never saw the ghost of a chance to hang up the party. He knew he had to be very careful to avoid suspicion in whatever he did, but, as the days went by, he began to feel desperate.

At this rate they would do the whole journey within the week, while he doubted if Julio could reach Santa Cruz in less than eight or nine days; and even if Julio was lucky enough to find Rister in the town, the German could not make straight for Valdivia. He would have to fly first to Lake Argentino to make sure that Julio's information was correct. Meantime Frank and Dan would get a very long start and, once they reached Valdivia and got their concession, it was all up with their rivals.

The first two days they had unusually fine weather, but on the third afternoon it began to blow and rain. Also it was bitterly cold. They were crossing swampy ground and at every step the horses sank over their fetlocks in mud. By night the poor beasts were exhausted, and next morning Bartolo told Frank that it would be better not to start before midday.

The weather cleared at breakfast-time. At least the gale was not so strong and the rain stopped. Vincent, racking his brains for some way of extending the delay, left the tent and walked alone up the bluff under which it had been pitched.

They had left the swampland behind and reached low rolling hills with large patches of thick scrub. As Vincent reached the top a gleam of watery sunshine broke through the clouds and suddenly he saw something move among the bushes on a slope about half a mile away. He dropped flat and watched, and saw a magnificent dun-coloured bull step out into an open space and start grazing.

A hissing breath escaped Vincent's lips. This was luck. It might be just what he had been looking for. Vincent had been years in Patagonia, but only once before had he set eyes on wild cattle. These creatures, descendants of Spanish stock, have been running loose for hundreds of years and are actually as wild and pretty nearly as dangerous as the forest buffalo of South Africa. Vincent knew that Falcon would be mad to get one. In any case the party badly needed fresh meat. Yes, this was a chance and he meant to make the most of it. He slipped away down the slope and hurried to the camp.

Vincent was too cunning to go straight to Frank. Instead he told Bartolo what he had seen and a gleam of excitement showed in the gaucho's dark eyes. Like all his fellows, he loved the excitement of a hunt, but even more the prospect of a joint of roast beef appealed to him. The meat of these wild cattle is better than that of domestic beef and has a flavour of venison.

"I tell the Señor Falcon," Bartolo said. "He is good shot. We have beef for dinner."

Frank looked rather surprised when Bartolo suggested cattle- shooting, but when Jock explained that these creatures were as wild as anything in the world and as difficult to approach he became keen.

"I'd better take Vincent with me," he suggested. "It's only fair since he spotted them."

Vincent politely refused the offer.

"I'm no shot," he said. "Better take Ned. He's good with a gun."

"Won't you come too, Jock?" Frank asked, but Bartolo spoke.

"Two enough, Señor," he said. "These cattle, they are frightened very easy."

"They're scary," Jock said. "Bartolo's right. Take Ned. Two's plenty."

Frank took his rifle and Ned had the double-barrel loaded with buck-shot. By Bartolo's advice they made a round so as to get downwind from the herd.

The two worked up a swampy valley until they were exactly down-wind from the slope where Vincent had spotted the bull, then set to stalk uphill, taking cover behind clumps of prickly bush. They had to crawl on hands and knees, and it took a long time to reach the brow of the little hill. Then Ned, who was leading, dropped flat on his stomach and beckoned to Frank to come alongside.

In front was a small hollow with a bad patch of bog at the bottom and beyond that a fairly steep slope covered with clumps of brushwood. Ned pointed and above one of these clumps Frank saw the head and spreading horns of the big bull. Movements among the bushes behind showed where the rest of the herd were feeding.

Frank thrilled at sight of that wonderful pair of horns, but next moment they had vanished again as the beast lowered its head to graze. There was nothing for it but to wait and hope that the bull would move forward into an open patch a few yards ahead.

Minutes dragged by with maddening slowness. The bull did not show up, and Ned was horribly afraid that he had turned and was grazing away in another direction. At intervals some of the cows became visible, but it was the bull that Frank wanted. Then quite suddenly the huge creature stepped out into the open and stood still. His head was raised and he seemed slightly suspicious.

Frank did not hurry at all. He took the most careful aim, and to Ned ages seemed to pass before at last Frank's finger tightened on the trigger.

With the flat crack of the rifle two things happened. The bull went down as if struck by lightning; the cows went off at the most amazing pace. Even the long-legged guanaco could not have travelled faster.

"Topping shot!" exclaimed Ned in delight. "That head will be worth having." He scrambled to his feet and began to run. Side by side the two crossed the valley, having to go round the bog patch, then they went quickly up the hill to the spot where the bull lay.

The steep slope hid the body from them, then as they reached the crest the first thing they saw was that the bull was no longer there.

"Look out, Frank!" Ned screamed as the bushes parted and the monster came charging at them. His head was down, his eyes gleamed red with fury, he looked as big as an elephant.

Frank sprang aside, and as he did so his left foot caught in a twisted root and down he went flat on the wet ground.

His left foot caught in a twisted root, and down he went.

NED flung up his gun. There was no time to aim, for in a second those terrible sharp-pointed horns would be buried in Frank's body. He blazed away both barrels and at so close a range that the heavy buck-shot had a terrible effect. They stopped the mad brute's charge and brought it to its knees.

But the bull was not finished. To his horror Ned saw it scrambling up. There was no time to reload. He did the only thing possible, dropped the gun and ran down the hill.

The bull came after. Ned dared not look round. The ground was very rough and steep and he knew that, if he stumbled, that would be his finish. As he raced down the slope he could hear the monster thundering behind him.

Ned had never been in a tighter place, yet he kept his head. He realised quite clearly that his one hope was the bog patch at the bottom. It might bear his weight, at least for a few steps, but it most certainly would not bear the ponderous bull.

Running as he had never run before, he gained the bottom of the slope and saw the bog only a few yards away. A horrible pond of ink-black slime with a few tussocks of half-withered reeds showing above its quaking surface. With a mad bound he reached the first of these, felt it going and jumped to a second. He had barely reached this before he heard a thick splash behind him, and instantly he was covered with a shower of spattering mud.

He could not look round, for the tussock on which he stood was sinking. With a series of crazy bounds he managed to cross the pool of slime and fall on his face on the far side. He got up in a hurry and turned to see the bull up to his chest in the mire. Then he heard a shout and here came Bartolo running hard. He carried a rope and Jock was with him. Ned waved to them and ran back to where Frank had fallen. He met him limping down the hill.

"Are you hurt, Frank?" he asked anxiously.

"Seems to me it's I should ask that question of you, Ned. How you got away from that mad brute beats me."

Ned grinned. "Didn't you see me in the bog? It bore me but it wouldn't bear the bull."

"So that's what you did. But of course you would, Ned. You didn't lose your head as many twice your age would have done."

Ned got rather red. "Rats, Frank! It was the only thing I could do. And the bull's dead. Bartolo and Jock are hauling it out." He paused. "But you're lame as a tree. Lean on me."

"I've wrenched my knee," Frank said. "Cartilage slipped, I'm afraid."

"I can fix that for you," Ned declared, "but you'd better not walk on it. I'll go fetch the stuff."

"Jolly good of you," said Frank, but Ned was already gone. He came back from the tent with a roll of sticking-plaster and some cotton-wool. He cut two crescent-shaped pads of cotton-wool and put one under Frank's knee and the other on top just below the knee-cap. Then he wound four wide bands of sticking-plaster tightly round the injured joint and fixed them firmly with strips of binding plaster.

"Our hospital nurse at school in England showed me that tip," he said. "Now you can walk if you go carefully." And to Frank's great relief he found he could.

Meantime the others had got the bull out of the bog, skinned it, and cut out the tongue and the best of the meat. That night they feasted. The following morning was fine and they were on the road early.

Whatever Vincent thought about the failure of his plan, he was much too clever to let the rest suspect him.

There was no more rain and the rest of the journey went well, but, when they arrived at Tres Tortillas, it was a shock to find that the petrol had not yet arrived. Arnal, one of the men who had been sent to fetch it, had just turned up to say that the waggon had stuck in a bog and that he needed more horses to help to get it out. Since Frank was still lame, it was arranged that the boys and Dan should go with Arnal to bring in the waggon.

They started the following morning, leaving John Garnett, Frank Falcon and Vincent Slade at the ranch. John Garnett and Frank had much to talk about and Vincent, left to himself, wandered about restlessly. By this time Julio Vaz should have reached Santa Cruz and Vincent would have given a lot to know if he had found Rister and given him the letter.