RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Headpiece from Chums, 5 August 1916

KIT GODWIN turned away disconsolately from the back door of Cleave Hall. Squire Corynton was not at home, and the maid had said he would probably not be back until late. So the interview to which the boy had screwed himself up could not take place until next day.

It was a dull, lowering afternoon in spring, and the heavy clouds and dripping foliage matched Kit's spirits. He walked slowly down the drive, and had turned into the lane leading to his mother's cottage, when a youngish man leaped down through a gap in the hedge at the top of the bank and barred his way.

He was not a pleasant-looking customer. Tall and round-shouldered, he had a long, narrow face, and a thatch of thick black hair hanging over his small, greenish eyes.

"What you been doing up at the Hall, Godwin?" he demanded, scowling at the boy.

"I've been attending to my own business, Sim Lagden," replied Kit quietly. "And if you'll take my tip, you'll mind yours."

"I don't want none o' your cheek, young Godwin," retorted Lagden. "What you been getting out o' the squire?"

"You'd better go and ask him," returned Kit with unruffled calm.

"I'm asking you," snarled Lagden. "And you're a-going to tell me," he added truculently.

Kit laughed. "You talk big, Lagden. How do you think you're going to get it out of me?"

Sim Lagden's sallow face was black with rage.

"I'll show you mighty soon," he answered with a snarl.

Kit saw the man's fists clench, and suddenly realised that he was up against it. He knew that Lagden was fiercely jealous of him, just as he had been of his father before him, and he knew the reason. The hour was late, the place was lonely, and the odds against him heavy. But he did not quail; he stood eyeing his opponent warily.

"For the last time, be you going to tell me, or be you not?" demanded Lagden.

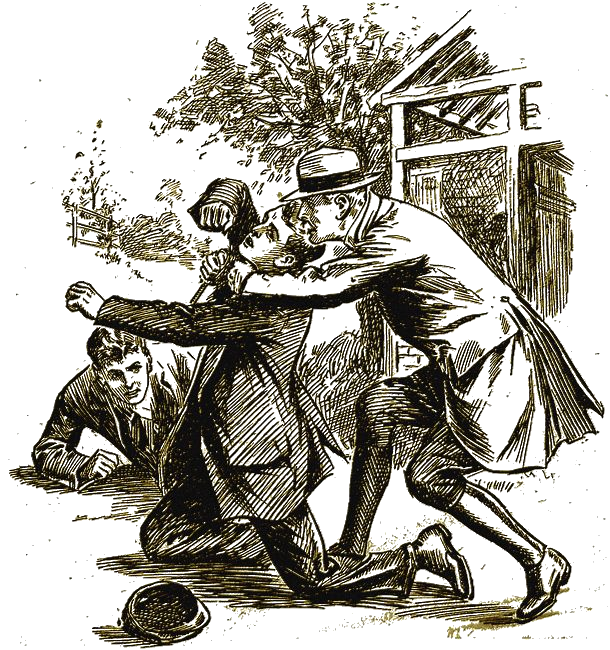

"I'm not," replied Kit curtly, and the words were hardly out of his mouth before Lagden rushed.

Lagden was six years older than Kit, a head taller, and all of a stone heavier. On the face of it it looked an entirely one-sided conflict. But Kit had two points in his favour. The first was that he had learnt to use his fists. His father, an old reservist, had taught him at any rate the elements of boxing. In the second place, the boy had good hold on his temper, while Sim was in a blind rage. Every boxer knows how much that counts for.

All the same, Kit had his work cut out to stop that first rush. Sim's long arms swung like windmill sails, and though Kit dodged and guarded to the best of his knowledge, he could not save himself from a crack on the temple which made his head sing.

He sprang aside to get breathing space, but the lane was narrow, and Sim was on him again. In sheer desperation Kit ducked in right under the long arms of his adversary, and got in two punches on the ribs which made Sim grunt.

Before he could win clear, Sim's right fist got home on his chest with a force that drove him backwards and very nearly floored him. Two inches lower, and the blow would have caught him on the "mark," and finished the fight at once.

Sim rushed in to finish him, but Kit, his muscles trained by long tramps, good food and hard work of all kinds, managed to spring aside. Sim blundered past, and Kit hit him on the jaw with all his strength.

Sim roared with the pain and spun round, striking out with both fists.

Again Kit gave ground, and, watching his chance, got in a smack meant for Sim's chin. Unfortunately it landed a little high, splitting Sim's lip and loosening several teeth, but also cutting Kit's knuckles badly.

If Sim had been angry before, now he was like a madman. With the blood dripping from his mouth, and muttering threats as he came, he hurled himself once more at Kit. And Kit knew that, once he went down, the fellow would not be content until he had beaten the life out of him. Sim was no longer a reasoning human being, but a murderous maniac.

Once more he leaped away, but in his hurry did not notice that he was right up against the bank. His heels caught, and he stumbled backwards.

Next instant Sim had him by the throat. The man's long dirty fingers sank into his flesh. He felt himself shaken to and fro like a rat in the jaws of a terrier.

"I'll learn ye," growled Sim.

Kit gasped for breath; his lungs felt bursting, and so did his head. Black specks danced, before his eyes, and still Sim's savage grip did not relax.

His senses were going, when all of a sudden he was conscious of heavy steps pounding on the road, and Sim Lagden was seized from behind and jerked off him.

"You infernal blackguard!" came a bellow of a voice. "You bullying brute!" And then a stick was raised, and came hissing through the air to descend with stinging force on Sim's back.

"You infernal blackguard!" came a bellow of a voice. "You bullying brute!"

He screamed like a whipped puppy, but the rain of blows did not check until he burst into sobs and wild prayers for mercy.

Then the big, grizzle-haired man who had come to Kit's rescue dropped him, and he sank moaning into the muddy road.

"Lucky for you, Lagden, that I came when I did. Otherwise it's the rope you'd have got, not a licking. Now then, young Godwin, what was it all about?" And Squire Corynton, for it was he himself, turned to Kit, who was sitting up and rapidly recovering.

"Out with it!" he ordered, as Kit hesitated. "Lagden's had his gruel. Whatever you say, it won't make any difference to him."

"Well, sir, I had been up to the Hall, and did not find you, and on my way back I met Lagden, and he wanted to know why I had been. I would not tell him, and then we fought."

The squire glanced at Sim, who was standing sullenly by.

"Fought, did you?" Then, as he saw the state of Sim's face: "Seems to me you did most of the fighting, Godwin," he added, with a chuckle. "And what did you want to see me about?"

"I was going to ask you, sir, if you would take me on as keeper in place of my father," answered Kit, looking the squire fearlessly in the eyes.

"My word, you were? You've got cheek, my young friend. Ha, I see now. Lagden suspected as much and was jealous. Well, he's out of the running. He never was in it. Come you up to the house, Godwin. We'll talk this thing over. As for you, Lagden," turning to the other, "make yourself scarce; and the less I see of you on my ground in future, the better I shall be pleased. You understand?"

Sim slunk away, and Kit accompanied the squire to the Hall.

"And how old are you?" asked the latter when they had reached the big study.

"Sixteen last March, sir," was the quiet answer.

"Sixteen last March!" repeated the other. "But this is absurd! Do you mean to tell me that you consider yourself capable of looking after twelve hundred acres of shooting? No, no; sorry as I am about your father, and glad as I should be to help you and your mother, the thing is out of the question."

Kit Godwin's face fell, but he still stood his ground.

"My father has taught me everything he knew, sir," he answered with a quiet doggedness. "I have been with him on his rounds ever since I could walk. I think I could tell you, sir, the whereabouts of every partridge and pheasant nest on the place. As for poachers—well, one man isn't much use against a gang any more than one boy; but I could keep an eye on them and fetch help as quickly as anyone else. Won't you try me, sir?" he ended rather breathlessly.

The squire was silent for some seconds. His eyes were still on the eager boy opposite. He noted the youngster's square jaw and the resolute expression of his face. He saw that, though rather short, Kit's frame was strong and well-knit.

"Everyone will laugh at me," he said at last, rather as if thinking aloud. "Engaging a boy of sixteen as keeper is really too absurd. Still—still—

"All right, Godwin," he said in a louder tone. "All right. I'll give you a trial."

"Thank you—thank you, sir!" burst out Kit.

The squire held up his hand.

"Steady on! I'm not engaging you. I am only giving you a trial. I shall watch you carefully, and I reserve to myself the right to dismiss you at a day's notice if you fail to make good. You quite understand that?"

"I do, sir. I quite understand it," replied Kit firmly.

"Very good, then. Meantime you will lake a pound a week, the cottage and the usual privileges which your father enjoyed. You will bring your accounts to me weekly, and you will, of course, be always able to see me if any difficulty arises."

"Very well, sir, thank you," said Kit once more, but did not turn to go.

"Is there anything else?" asked Mr. Corynton.

"Yes, sir. I was going to ask if you would order some artificial eggs for the partridges."

The squire stared.

"Your father never asked for any."

"No, sir; but he often talked of the Euston system, and if you don't mind I should like to try it. You see, it saves a deal of risk from late frosts and that sort of thing, and it would increase the head of birds by quite a third."

"But it means no end of extra work," objected Mr. Corynton.

"That will be my affair, sir," Kit answered.

"Very well. You can try it if you like. I will order the eggs at once. Is their anything else?"

"No, sir. Thank you, sir!"

"Good morning, then," said the squire with a nod, and Kit turned and left the room.

KIT GODWIN'S face was beaming as he hurried home. His application had been entirely his own idea. He had not even told his mother, and he knew how intensely relieved she would be when she heard of his success.

The death of his father at the front had been a terrible blow to her, but the knowledge that she would have to leave the old home at Cleave made things very much worse.

In her delight at his news, Kit forgot all about Lagden. He might not have felt so happy could he have seen the man who at the moment was lying on his bed aching in every limb, and planning in his dark soul how he could get even with the boy who had ousted him.

Next morning Kit plunged into his work. Spring is by far the busiest time for the keeper. Pheasants and partridges are nesting everywhere. It is the keeper's duty to find each nest and keep an eye upon it, and to save eggs and old birds alike from their many enemies, both four-legged and two-legged.

Cleave, Squire Corynton's estate, had little covert, and consequently few pheasants; but it was a famous breeding ground for partridges. For the past two seasons, however, the stock had been falling off, and this was one reason why Kit was so anxious to try the Euston system.

Briefly, this consists in taking the eggs from the nests of the wild birds as soon as laid, and substituting for them artificial eggs. The wild eggs are then put under hens—preferably bantams.

Hens can keep partridges' eggs warm and safe, but it is not possible to leave them to hatch under the hens. So when on the point of hatching they are carried back to their original nests, the artificial eggs are taken away, and the real eggs restored to the mother birds.

It means a lot of work, but it pays. A couple of years of this system will double the stock of partridges, for the eggs are saved, during hatching, from risk of late frost and from stoats, hawks, crows—to say nothing of two-legged poachers. A week after his first interview with the squire, Kit was back in the big study at the hall.

"Did you order the eggs, sir?" he asked.

"I did, Godwin. I wrote at once. The firm promised to send them as soon as possible, but the war is hanging everything up. They have not yet arrived."

"We ought to have them, sir," said Kit seriously. "A lot of the birds are laying. I counted over sixty eggs yesterday."

The squire, too, looked grave.

"I will write again, Godwin. If we do not get them, you will just have to carry on as usual this year."

Three more days passed. The eggs did not come, and the partridges were laying everywhere. Kit knew that the squire was expecting a party of officers on leave to shoot in September. He was most anxious to show a good stock of birds, and badly disappointed about the non-arrival of the eggs.

On Friday afternoon Kit went into Taviton, the market town, to see about some wire netting which was wanted, and while in the iron-monger's shop was hailed by young Arthur Stapleton, an old friend of his, whose father was keeper on the Lychworth place up oh the edge of the Moor.

The two went off together to get a cup of tea, and presently Kit found himself telling Arthur all about his troubles.

"Don't you kick," replied Arthur. "You're a sight better off than we are. Up at our place we had five degrees of frost on Wednesday night, and dad says the bigger half of our eggs are spoiled altogether."

"That's poor luck," said Kit with sympathy. Then, after a moment's thought, he leaned forward eagerly. "I say, what have you done with the spoilt eggs, Arthur?"

"Nothing yet. They're still under the birds."

"May I have them?"

Arthur stared.

"What in sense do you want with a lot of addled eggs?"

"Why, don't you see? I can use them instead of these china eggs which haven't turned up."

Arthur chuckled.

"That's not a bad notion. Yes, of course, you can have them. I'll mention it to father. When will you come for them?"

"To-morrow. I'll bring the cart and fetch the lot."

Four the next afternoon found Kit at Lychworth, and at the cottage young Stapleton was waiting for him with two great baskets of spoilt eggs.

"More than I thought, Kit," he said sadly. "I've found nearly twenty dozen in all. Our stock of birds will be short this year unless we buy eggs from away."

Kit's eyes gleamed when he saw the spoil, and he packed the baskets quickly into his cart.

"Now come in and have some tea," said Arthur. "Mother's made some pasties, and there's potato cakes and cream."

His appetite sharpened by his long drive, Kit did full justice to the excellent tea, then drove quietly home. Next morning he was out at dawn, and, seizing the hour when the hen partridges are off their nests, getting their morning meal, he rapidly changed the eggs, carefully collecting the sound eggs and putting the spoilt ones in their place.

The sound ones were kept warm, as he carried them back, between layers of cotton-wool; and as soon as he got home he placed them at once under the broody hens which he had collected beforehand.

The eggs once safe under the hens, Kit's chief anxieties were over for the present. But he still had to watch the birds themselves. Foxes and other marauders very often carry off sitting partridges and pheasants. Besides, some of the birds were still laying, and these eggs he had to collect and substitute others for them.

On the following Tuesday morning he was out early as usual. He went through the coppice into a field of winter wheat, where he knew of four nests close under the hedge at the top end. The very first nest he came to the bird was off, and all the eggs gone.

Kit hurried to the next. That was safe, but the third and fourth had both been raided.

He went back to the first, and examined the ground carefully. There were marks of footsteps which were not his own, but the ground was hard as a brick. The marks were not easily identified. In fact, he could make very little of them, except that they were certainly quite fresh. This he could tell because the grass was wet with dew, and the dewdrops had been newly shaken from the blades.

"Whoever it is, he can't have gone far," said Kit to himself, and at once set about tracking the marauder.

The sun was not an hour up, and its slanting rays shining across the dewy grass showed plainly enough which way the egg thief had gone. Kit soon found where he had crossed the hedge. But the next field was plough, and here the track was more difficult. Still, the footprints showed here and there, and led to a gap in the next fence. Peering through this, Kit suddenly caught sight of a woman walking at a fairly rapid pace towards a gate on the opposite side of the field.

He paused, frowning. This was the thief. Of that he had little doubt, but all the same it was a nasty job to have to tackle a woman and accuse her of theft. Still, it was all in the day's work, and he set off after her at a sharp pace.

But before he got near her, she was through the gate and into the next field, which was a leasowe, a great rough swampy pasture full of gorse and dotted with clumps of hazel and alder. By the time he reached the gate she had vanished completely.

Kit's heart sank. There was cover to hide a regiment in this big leasowe. She might dodge him a dozen times over. But Kit was a boy of infinite resource. There was a good-sized pollard oak growing near by. He shinned up quickly and, getting well among the branches, found that he had a bird's-eye view of the whole field. Almost at once he spotted the woman. She had turned sharp to the left, and, taking advantage of the thick cover, was making the best of her way towards a lane which ran along the bottom of the field.

She was trying to dodge him. That was plain as a pikestaff. Kit came sliding down, and, cutting along the hedge, got into the lane. He looked about, but there was no sign of her. Just as he was thinking that she must have spotted him and turned again, there was a slight rustle and she came sliding slowly down the bank.

"Stop!" shouted Kit; "I want to speak to you."

She started, turned, saw him, and at once spun round and was off at a rare pace.

"My word, she can run!" exclaimed Kit as he took up the chase. She could run. There was no doubt about that. But for her skirts Kit doubted if he would have caught her. But he gradually pulled closer, and at last, just where the lane ended in the main road running into the village, came up to her.

She turned on him.

"What do you mean by running after me like this?" she demanded shrilly.

"What made you run away, then?" retorted Kit, rather breathlessly.

It was at this moment that steps were heard, and two men came up from the direction opposite to the village.

They were the squire and his bailiff, Mr. Norton, out for an early tramp.

"What's the matter?" asked Mr. Corynton in evident surprise.

"This chaps been running after me and frightening me out of my life," answered the woman in a tremulous tone.

The squire faced Kit.

"What does this mean, Godwin?" he said severely.

"I—I suspect her of stealing eggs, sir," faltered Kit, much taken aback.

"Me steal eggs!" cried the woman in a voice of scorn. "Do I look like it? I ask you, do I look like it?"

The squire looked her up and down. She was quite well dressed, and had the appearance of a well-to-do farmer's daughter.

"What makes you think that she has been taking eggs?" asked the squire of Kit. He spoke so coldly that Kit felt horribly uncomfortable. He knew that he had no real evidence, and his conviction that she was the real thief began to falter.

"I found partridges' eggs had been taken, sir, and I followed the tracks. She was the only person in sight."

"A pretty way to talk!" burst out the woman indignantly. "Just because I go out early to look for mushrooms, I'm to be chased and frightened out of my life by a fool of a boy. And if I'd taken the eggs, where are they now? I ask you that."

She spoke in a high-pitched, angry voice, and with an air which evidently impressed the squire.

"Comes of letting boys try to do men's work!" she continued bitterly.

The squire shook his head.

"I knew that I was foolish," he muttered. "I knew the boy would get into some sort of trouble."

Kit was in a horrid stew. But, luckily for him, he still kept his head. One thing struck him forcibly.

The woman evidently knew that he was acting as keeper. Yet he himself, to the best of his belief, had never set eyes on her before. She must be a stranger to the neighbourhood. How, then, did she come to know who he was?

He made up his mind to a bold stroke.

"She protests a lot, sir," he said to the squire. "If she's so innocent as all that, where does she keep her mushrooms? She hasn't got a basket."

"I was that frightened I dropped it," broke in the woman sharply.

But Kit, watching her face, distinctly noticed a look of sudden alarm in her eyes.

"That may be true," he said quietly, "but I know she had no basket when I first saw her. Now, I ask you, sir, in fairness to both of us, if she'll come down to the village and allow herself to be searched by Mrs. Ladd at the inn."

Before the squire could speak the woman broke in:

"I won't be insulted like that by anyone," she said, with her nose in the air, "I'm going home."

She was turning when Norton broke in, speaking for the first time.

"Godwin's right, sir," he said dryly. "I've heard before now of women hiding eggs in pockets under their skirts."

The effect of his words on the woman was decidedly startling. She gave a frightened cry, and was off down the road like a hare.

"Catch her, Kit!" cried Mr. Norton, and began to run himself.

The early rising villagers saw an extraordinary sight. A woman running at amazing speed down the centre of the village street; hard after her, Kit Godwin; next, Mr. Norton thundering along in hobnail boots; and last of all the squire, very red in the face and blowing like a grampus, but still doing wonderfully well for a man of nearly sixty.

Ladd, of the New Inn, a huge, stout man, with a shiny bald head and a great black beard, heard the uproar and came out in his shirt-sleeves.

Norton saw him.

"Stop her, Ladd!" he roared; "stop her!"

Ladd strode forward and opened his huge arms. They seemed to almost bar the narrow street. The woman, running all out, could not stop herself, and charged straight into the gigantic innkeeper with the same sort of effect as a ship running hard on a rock.

The shock made even Ladd reel; but as for the woman, she went down with a whack on the ground and the words she said as she landed were not such as women are usually acquainted with.

Ladd stared at her a moment.

"She swears like a drunken bargeman," he remarked. Then suddenly he put his fingers to his nose. "And smells a darned sight worse," he added, with a look of extreme disgust.

Kit reached the spot, and pulled up short as a most hideous reek met him. It was the sort of smell that nearly knocks you down.

"Take her away," growled Ladd, retreating. "She's worse'n a polecat. She'll poison the whole village."

Norton arrived, then the squire, then about a dozen villagers.

"Good heavens, what a fearful odour!" exclaimed the squire, pulling out his handkerchief.

"It's the eggs, sir," said Kit triumphantly.

The woman had risen to her, feet. Her skirt was streaming with a horrible compound of broken eggs in a high state of decomposition. Her face was a study in rage and despair. In her fall her hat had been knocked sideways.

Kit stared at her a moment, then suddenly stretched out his arm and seized her hat. She gave a yell and put up her hands.

Too late. Off came the hat, and with it a whole crop of thick golden red locks, leaving a head covered with closely cropped black hair.

"Why—why, it's Simon Lagden!" gasped the squire. Then, the fearful reek overcoming him, he stepped back again quickly.

"Yes, sir. It's Lagden, and these are our eggs," replied Kit. "As I couldn't have the artificials in time, I got some addled ones instead. Not much doubt about them, is there, sir?" he added, with a grin.

"Phew! It's enough to poison a dog!" snorted the squire. He was all the more angry because he had been so thoroughly taken in. "I'll teach him to steal eggs, fresh or addled either, before I've done with him. Here, some of you, wash him and bring him up to the Hall."

Sim glared round, but he was surrounded; nor was there pity in any eyes. Ladd stalked back into the inn yard.

"Now then, spread out!" came his big voice a moment later, as he emerged dragging the coils of a garden hose behind him. The tap was turned, and a jet of ice-cold water hit Sim with a force that made him reel and gasp.

He screamed, he yelled, he swore. It was no use.

Pinned against the opposite wall, he was doused and drenched till his soaked skirt and blouse hung round him like wet dish-cloths and the last trace of the yellow, egg-yolk had been washed into the gutter.

"There, I'll lay he's cleaner than ever he was in his life before," said Ladd calmly, as he turned off the tap at the nozzle. "Now you can take him up along to the Hall, young Godwin."

Kit had been talking to the squire in a low voice, and now the squire himself spoke up.

"I think he's had his dose this time," he said grimly. "I don't propose to punish him further for the present. But, look you here, Lagden," he continued impressively; "you let me catch you at any of these games again! Let me catch you, I say, and it won't be cold water you'll get, but something a sight warmer. Now go!"

Followed by the jeers of the crowd, Sim slunk away up the street and vanished.

The squire turned to Kit.

"You've done well, Godwin, and I apologise for doubting you," he said handsomely. "If you like to walk up to the Hall with me the housekeeper shall give you some breakfast, and then, you can take those artificials back with you. They came last night. One thing," he added, with a smile, "they won't smell quite so bad as your patent substitutes."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.