RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

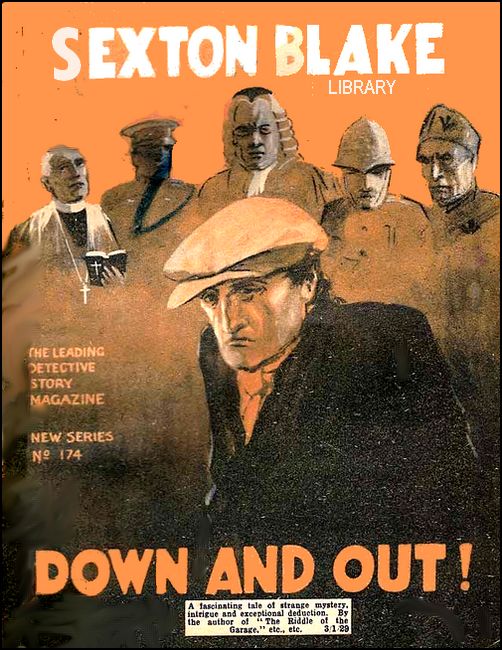

The Sexton Blake Library, Jan 1929, with "Down and Out!"

Sexton Blake

ALL through the evening and far into the night, a great gale had been sweeping through Yorkshire. The wind had howled over mountain and moor and dale, while the rain had lashed and splashed and drenched every inch of the county of broad acres.

Dentwhistle Moor in the West Riding had caught the full fury of the tempest. The village of Dentwhistle itself had partly escaped by reason of the sheltering shoulder of the mountainous Caukle Fell, but, half a mile away, one little stone cottage had rocked and rocked in the rushing mighty wind, almost like a boat in a raging sea.

This cottage stood on the high moor, exposed to every wind that blew, at the head of the great mountain-limestone quarries, which formed the district's staple industry, and kept most of the able-bodied villagers employed.

In this lonely cottage—there was no other human habitation nearer than the village, save one—lived old Luke Samways and his wife. Samways had been a quarryman himself for most of his working life, but some years before our story opens, a fall of limestone rock had made a hash of his right leg, and left him permanently lame. From that time, therefore, he had filled the responsible, but somewhat less strenuous, office of timekeeper and night-watchman, a position which carried with it the tenancy of the little stone cottage referred to.

Although called night watchman, his duties rarely necessitated his being up later than ten o'clock, and at that hour, after a final "look round," he had retired as usual on this night of storm.

Accustomed to the moors in all their varying moods from the time he was a child, old Luke scarcely heeded the raging gale, but like the healthy man with an easy conscience that he was, fell to sleep almost as soon as his grey and grizzled head touched the pillow.

With his wife it was otherwise. A town dweller in earlier life, she had never become quite inured to wild moorland weather, spite of her thirty-odd years of happily married life with her husband. Ordinary storms she could stand—and sufficiently forget—but the terrific tempest of to-night had been something that she could not ignore. It had kept her awake till past midnight with its fierce howling. Then, as at last there came a lull, she too fell asleep.

But for barely five minutes! Then something made her start awake instantly, and sit bolt upright in bed!

The violence and suddenness of her movement awoke her husband, too.

"Why, lass, what is't?" he asked. "Why 'ow thou'rt tremblin'? Shakin' like a leaf? What ails tha, Bessie, dear?" She did not answer a second. Only gasped and trembled.

Luke hopped out of bed and switched on the electric lantern standing on the floor near by—the lantern he used on his quarry rounds. Its bright rays fell on his wife's face.

"Why lass, thou'rt as white as paaper! Thou'st been skeered. Whaat's skeered thee?"

"A gunshot, Luke! I heard a gunshot!"

"Nay, nay, tha couldn't a done! Thou must a dreamt it, or belike 'twere the wind! Hark to it now. It's clappin' and yappin' like muskets now. 'Twas the wind tha 'eard!"

"No, Luke, no!" She was out of bed now with a wrap around her. "'Twas a gunshot I heard for sure! And hark to that—merciful Heaven! Hark to that! 'Tis another gunshot!"

There had come a sudden lull in the wind again, and in the lull had come the unmistakable report of a firearm.

"By gum, lass, thou'rt right!" cried the man. "That was a gun—or a revolver more like!"

"As 'twas before!" gasped the woman all trembling and pale. "And hark to that! 'Tis somebody shoutin'! Somebody screamin' for help! Heaven save us! 'Tis as if murder were bein' done!"

"Nay, nay, 'tis nowt as bad as that, Bess," answered Luke as he hurried his clothes on. "'Tis nobbut more than poachers! Bide tha 'ere while I go and have a look round. I'll be back soon, so don't tha tak on, my lass!"

He spoke as comfortingly as he could for his wife's sake. Since the time of the great war, her nervous system had been peculiarly affected by the sound of firearms, owing to the shock of an air raid during a temporary stay in London. But although he spoke thus consolingly, he inwardly had little belief in the words he had used. Poachers? What was there to poach in that district? Or was it the least bit likely poachers would be out on so wild a night as this?

Mercifully the rain had stopped some time before, but the wind, though intermittent, was still blowing great guns at times. It made his electric lantern swing violently as he hobbled towards the great quarry near by, and to cast big, weird, distorted shadows upon what once had been green turf, but was now a wide, white stretch all covered with the dust of limestone, and heaped up with chips and quarried boulders.

It took him but a few seconds to reach the hut at the top of the quarry which served as the timekeeper's office. The door was looked as he had left it, and a flash of his lantern through the window showed it to be empty.

Nothing wrong there, nor anywhere about the quarry entrances so far as he could see. No sign of recent foot-prints in the whitened wet spaces, no sounds from anywhere.

From whence had those shots come, then? Certainly not from the village. That was too far off, and was to leeward of him, so that even if the shots had been fired there, they would never have been heard.

"Help! Help! Help!"

The cries came suddenly to interrupt his speculations. Frantic cries, borne on the wind, which had lulled as to sound but was still blowing with some power.

They pulled him up suddenly, making him swing round and face the other way. At the same moment, footsteps came hurrying from the direction of the cottage he had just left. It was his wife, more scared-looking than ever, but brave all the same.

"Luke—Luke—the green bungalow!" she gasped. "'Tis from there the shoutin's come!"

"T' green bungalow—Mr. Dolby's place? But thou'rt right, lass, thou'rt right. Theer be the shouts agen! But get tha back to the cottage, Bess. 'Tis no fit night for thee to be out. I'll see what's amiss!"

Lame though he was, he hobbled past his wife at a great pace, leaving her to return indoors while he himself went on towards the place mentioned, namely, the "Green Bungalow."

This was barely two hundred yards away, but was hidden from view by a shoulder of the big hill. It was a building of concrete and wood, and was the only other human habitation nearer than the village.

It had been built a few months before by the gentleman who lived there—Mr. Nicholas Dolby. Lived there, that is, at night time and week-ends only. For Mr. Nicholas Dolby was junior partner in the firm of Messrs. Sharron and Dolby, Solicitors, and spent his working days in their offices at Lummingstall, the manufacturing town ten miles away where he practised.

Hating town life and loving the quiet of the country, he had built a comfortable bungalow among the hills, motoring to and from Lummingstall every day. Being a bachelor and unable to get servants to stay in such a lonely spot, he lived quite alone, being cooked for and attended to by old Mrs. Samways who lived close by. Luke also lent an occasional hand in cleaning the car and doing a turn at the little garden, so that he knew the place and Mr. Dolby quite well.

Rounding the shoulder of the hill, and approaching quite close to the green bungalow, an astonishing, not to say alarming, sight met his eyes.

Outside the wooden garage, which was a short distance from the bungalow, stood a tall, spare man. He was attired in a dressing-gown and slippers. His head was bare, his hair unkempt, his face deadly pale, his eyes distraught!

He was standing quite close to the garage door, facing it, while in his right hand was a heavy walking stick. This he was clutching by the wrong end, with the heavy knob raised in air, ready as it seemed to bring it down on the head of somebody evidently shut up in the shed, and who apparently, he feared, might try to break out at any moment.

The moon had come out from behind dense clouds a moment before, revealing the strange scene in all its details. A single glance, therefore, enabled Luke Samways to recognise the figure at once.

"Mr. Dolby!" he panted. "What be all the din? I heerd shots and shoutin's. What's bin happenin'?"

At sound of his voice the solicitor turned a white scared face quickly round.

"You, Samways? Thank Heaven you've come! There's a burglar inside!"

"A burglar, sir?"

"A most desperate ruffian! I caught him breaking into the bungalow! He shot at me but missed, and I managed to stun him with my stick!"

"Heaven save us, sir! T' missus was right, then. 'Twas murder that might a bin done. And t'ruffian's in theer now?"

"Yes. But may come to the break out at any moment. Hurry to the village for the police. My telephone's out of order. Hurry to the village for help at once!"

LUKE SAMWAYS hobbled off at a pace astonishing in a cripple. His brain was all in a jumble. Nothing like this had ever come his way before. Burglary—attempted murder. These terrible things were quite alien to the placid though busy life he had led for years in that remote Yorkshire village.

Truly remote was Dentwhistle, a little world of its own, so to say, tucked away amid the rocky hills, far from the busy haunts of men.

Yet not so far away as to distance after all. On a clear night or day great manufacturing towns could be discerned all around it, or rather, the distant haze and smoke of them. Less than twenty miles eastward lay Bradford, with Leeds beyond, while over the Lancashire border lay Burnley to the north-east, and Rochdale to the south-west at almost equal distances. But while those towns teemed with life and noise and bustle, much of the great triangular tract in which Dentwhistle lay remote and quiet as if they had been a hundred miles from any such hive of industry.

Even to-night, with the atmosphere cleared by the dying tempest, the lights of some of these far-distant places could be made out. But Luke Samways had no eyes for them. No thoughts either for aught save the important errand he was on—to get help.

Burglary—attempted murder! These were things right outside his ordinary ken. Now that they had come, it was little wonder that the terror of them should engross all his mind.

Fancy such things coming to such a quiet, retiring, peace-loving man as Mr. Dolby. Such a placid, mild, almost meek gentleman as he was. And none too robust, either. Not the sort you'd willingly pit against a desperate ruffian. Yet he'd tackled this midnight thief, and in spite of being shot at, had boldly faced him, and had managed to stun him with his stick.

"A good plucked 'un, spite o' lookin' so skeered arter it all!" was the watchman's inward comment as he hastened along. "Nobbut a good plucked 'un 'ud atackled a chap wi' a revolver like that. Ha, yon's the village, and yon's the pleece-station. Oim 'opin' Constable Stack'll be at 'ome!"

Constable Stack was at home, just preparing to start out on his night beat. He was startled and excited enough at Samway's news, for serious crime had rarely come his way. But he faced the job eagerly enough, and just waiting to enlist a couple of quarrymen as helpers, at once set off with Luke Samways on the return journey.

Mr. Dolby was relieved enough to see them come. He was still on guard with his knobby stick outside the garage. Still very pale, too, but resolute and full of pluck all the same.

He wheeled round at their footsteps and advanced a pace or two as he caught sight of the policeman's helmet in the moonlight. Constable Stack saluted him respectfully. He not only knew him as a resident of Dentwhistle, but as one of the leading solicitors of the neighbouring town of Lummingstall.

"Startlin' news Samways has told me, sir. Hope you ain't come to any harm?"

"Nothing to speak of, thank you, constable," replied Mr. Dolby, with a somewhat sickly attempt at a smile. "But it wasn't the scoundrel's fault that he didn't kill me stone dead. He fired at me point-blank, but by a stroke of luck I managed to knock his revolver-hand up and the bullet went harmlessly in the air!"

"Where is the weapon, sir? He hasn't got it still, I hope?"

"Oh, no! I managed to stun him with my stick before he could fire a second time, and the revolver fell from his hand. I haven't had a chance to look for it yet, but no doubt we shall find it somewhere about. In those bushes perhaps."

"We must search later, sir. What about the villain himself? Come to yet?"

"I think not. I've heard nothing of him. After knocking him out with my stick I carried him inside and locked him in. I fancy I've heard him groan once or twice, but can't be sure."

"Long time for him to remain insensible, sir. We'd better have a look at him."

"Here's the key, constable," the solicitor said, taking it from his pocket.

"Sticky, sir. There's blood on it!"

Mr. Dolby shuddered.

"Is there? I didn't notice. I was too excited. Must have come from that scoundrel when I cracked him on the head."

Constable Stack turned to Samways and the others as he fitted the big key into the door. "Be ready in case he's waiting his chance to make a dash. Spread yourself across the doorway!" But there was no need for anything of that sort. As the constable threw the door open and flashed his bull's-eye inside the figure of a man was to be seen all huddled up on the ground. Stack was kneeling beside him in a moment, his hand to the man's heart.

"He's not dead! I haven't killed him, surely?" asked the solicitor, painting for breath and with face twitching distressfully.

"Oh, no, sir! His heart's beating, but he's unconscious still. My word, sir, but you fetched him some knock, not but what I'd have done the same thing myself under the circumstances. Look at this bump. Makes his head about twice the size it ought to be. We'd best get a doctor to him. Will one of you chaps go back to the village and fetch Doctor Alford?"

"Ay, I'll go!" replied one of the quarrymen, and hurried away.

"Strong petrol smell about this place," said the constable with a sniff. "Best carry this chap into the bungalow if you don't mind, sir. He'll come to quicker there!"

Two helpers lifted the unconscious man and carried him across to the bungalow, placing him on an old couch in the kitchen.

"Can't do much till the doctor comes, so if you don't mind, sir, perhaps you'll please give me an account of what happened!" and Constable Stack took out his notebook.

"Certainly, constable, not that there's a great deal to tell," answered Mr. Dolby, and in the manner of a trained lawyer told his story briefly and to the point.

He had retired to bed somewhere between ten and eleven, and had been asleep for an hour or more, when he found himself suddenly sitting up wide awake. What had happened to him he didn't know. For a moment he had thought it must have been the noise of the gale, but a second after he had heard other sounds that made him leap out of bed and rush to his window, which, like the rest, was, of course, on the ground floor.

Looking out, he was amazed, not to say startled, at seeing a man gliding away from another window towards the garage, whose lock he started to pick, evidently with the intention of stealing the car inside.

Hastily donning his dressing-gown and seizing a heavy stick, Dolby had rushed out and challenged the fellow. At once the burglar had turned on him menacingly with a revolver. There had been a brief struggle, during which the weapon had gone off in the air. Then having managed to stun the ruffian with his stick, the young solicitor had locked him inside the garage and shouted for help, which had come a few minutes later in the shape of Luke Samways.

"You saw him coming away from one of the bungalow windows, sir? Which window was it?" asked the constable, looking up from his notes.

"The window belonging to the best bed-room," answered the lawyer; and then his face suddenly contorted and he gasped out: "Good heavens! I'd forgotten!"

"Forgotten what, sir?"

Mr. Dolby didn't answer for a second. He stood where he was with a sudden great agitation upon him. With a catch of his breath he blurted out:

"I'd forgotten amid all the excitement that somebody was sleeping in that room. I'm usually alone, but to-night my partner, Mr. Sharron, is staying with me. He's sleeping in that room!"

"The very room the thief was coming away from. And you haven't been to see if old Mr. Sharron's all right. We'd best see now!" cried Stack.

"Yes, at once. Come this way."

They were out of the kitchen and along the passage in a moment. Mr. Dolby led the way right to the other end, hurrying and visibly anxious.

"Here's the room!" he said, controlling himself. "Mr. Sharron's old, as you know, and he's been ill for a long time, so we mustn't excite him too much. I'll just see if he's all right, so wait here a moment."

He opened the door softly and tiptoed into the room so as not to alarm the sleeper. But two seconds later, as he advanced towards the bed, there broke from him such an agonised cry as immediately brought the constable and the others hurrying into the room.

"What is it, sir?"

"Look—look!" almost screamed Nicholas Dolby. "Poor old Mr. Sharron! Look at him! He's—dead!"

ALL stared at the figure on the tumbled bed, aghast. All saw in a flash that Mr. Dolby's word were true, and the sight appalled them!

First to recover himself, the constable stepped right up to the bed to take a closer view of the already set features of the old man who lay there.

"Dead—dead for sure!" he murmured with a slow shake of his head. "How did he die? Can't see any—Merciful heaven! Look here!"

His charged speech came as he turned the bedclothes farther back. They were all wet with blood as was the old gentleman's blue-striped sleeping suit.

"He's been shot!" exclaimed the constable. "Here's the bullet wound, see!"

"Shot!" echoed Dolby emotionally. "Then that scoundrel of a burglar shot him, just as he afterwards tried to shoot me! Must have been the shot that woke me. Constable, it's murder—wilful murder!"

"Looks like it, sir. But the bullet seems to be in the groin. Queer for a wound like that to have killed him so soon, don't you think, sir?"

"Ordinarily, perhaps, yes. But not in his case. His heart was so weak! He's been ill for a long time. The shock would be enough to cause death! Oh, my poor, dear old friend and benefactor!"

And kneeling down beside the death-bed, Nicholas Dolby covered his face with his hands and broke down in uncontrollable grief.

The constable and the others looked pityingly on at the younger solicitor's sorrow, for all knew something of the true relationship which had existed between them—a relationship to be explained presently, and indicated in the younger man's use of the words "friend and benefactor."

But there came a quick interruption to this poignant scene. Steps were heard in the passage, and a moment later Dr. Alford entered the room.

His trained eye told him at a glance the truth about the body on the bed. It shocked him greatly. First, because he had been fetched to attend merely to an unconscious man, not to a dead man at all. Second, because Mr. Sharron was a man he had known in years past.

Shock, however, did not prevent him from doing his duty. In a moment he was beside the dead man, examining the bullet wound in his thigh, and searching for other possible injuries.

He, like the constable, was a little surprised that the old lawyer should have died so soon from a leg wound, but on hearing Mr. Dolby's account of the heart disease of long standing, agreed that he might have died from shock.

"Or he may have been choked to death!" he added. "There are marks on the throat, but the bruise hasn't properly come out yet. But about his heart—he was medically attended for that, of course?"

"Oh, yes, first by Dr. Pettry, of Lummingstall, but that was two years ago. It was on Dr. Pettry's advice that he practically retired from business, and went to live at Southport."

"Ah, yes. I must see Dr. Pettry. There'll have to be a post mortem, of course. But I expect he's been medically attended at Southport too?"

"Oh, yes. I forget the name of his doctor there, but that can be easily ascertained from his nurse. Mr. Sharron has, as perhaps you know, been a widower for many years, and had no near relatives."

"Quite—quite! There'll be quite a lot of things to do later, but just now I must see this other man—this burglar. It was on his account you sent for me, I believe. Where is he?"

"In the kitchen, sir!" It was Constable Stack who answered. Mr. Dolby seemed incapable of doing so. He was looking at his old friend and benefactor again, and the sight of him lying there dead, seemed altogether too much for him.

"What's happened? Where am I?"

It was the burglar who gasped out those words. He had been brought to after a few minutes, under the ministrations of Dr. Alford.

During these few minutes as he lay unconscious on the couch, they had been able to take careful stock of him. He was quite a young man, not more than thirty-two. He was moderately tall and quite well built, but thin and ill-nourished, while his face just now was, of course, very pale as a result of the blow on his head which had rendered him unconscious. His clothes were shabby and threadbare, and soaked through with the rain, as if he had been long out in the wild storm. His boots were very down at heel, with holes in the soles. They had let in the water.

Already Constable Stack had removed those boots, had examined them closely with certain significant nods of the head and had then carefully placed them on one side. In addition, he had made many notes in his pocket-book, as to the man's condition and other things.

Now as the man at last spoke, he turned to him, still with his notebook in his hand.

"Why as to that," he said drily in reply to the fellow's gasped questions, "seems to me you ought to be able to tell us about that. What's your name?"

"Wilson—John Wilson!"

Constable Stack wrote the name quickly in his book, then whispered to the doctor: "What about charging him, sir? It's a case of murder—I shall have to charge him with that!"

"Not at once!" the medical man said hastily. "He's very weak at present. Give him a few minutes anyway to recover. Perhaps he'll tell us something about himself first. You can charge him when he's a bit stronger."

The policeman nodded, and turned again to the man who was now half sitting up on the couch rubbing his injured head.

"Now, John Wilson, how come you to be trespassing on private property at this hour of night?"

"I'm sorry, but I came to get shelter," answered the man nervously. "I've been on tramp. I've come from London. Been on tramp for three weeks. I was making for Burnley. But I got caught by the storm out on the moors yonder. I was wet and tired and hungry. Pretty well fit to drop, I was. That's why, when I spotted this house, I made for it, hoping to find some sort of shelter where I might get a bit of sleep."

"You've tramped from London and were making for Burnley," echoed the constable, who had rapidly pencilled the words down. "Why were you going there in particular?"

"Because I'd hopes of getting a job!"

"Why there more than anywhere else?"

"Because I know a gentleman there. Or did know him a few years ago. In the war, that was. I served under him in Flanders—at Ypres, and other places."

"Who was he?"

"Lieutenant Straker! Leastways, he was then. Now I suppose he's plain Mr. Straker. Mr. Adrian Straker. Manager of some big ironworks at Burnley, he is. I see that by chance in a paper. That's what put it in my mind to go and see him in the hopes of a job. Heaven knows I want one bad enough, with a wife and poor little kiddy nigh on starvin'."

"So you're married then? Where do your wife and child live?"

"London. Islington. They lives in a garret at No. 34, Tubb Street."

More rapid note taking by the constable, then further whisperings with the doctor, till he turned again to the suspect with—

"Well, John Wilson, I've heard your explanation, and—well it don't quite fit in with what's happened!"

"How do you mean?"

"You must consider yourself in custody!"

"In custody?" the man panted. "What, just for innocent trespassin'!"

"No—I charge you, John Wilson, with murder!"

"Murder! Great and merciful—"

"Stop! Let me finish! The charge is the wilful murder of Mr. Richard Sharron, by shooting him with a revolver!"

"Great heaven! It's false—it's—"

Again the constable pulled him up.

"Let me finish! My duty is to warn you that you needn't say anything, and that anything you may say will be used in evidence against you!"

"I don't care!" Wilson's face was contorted, and his voice rose to a shriek. "I must speak! This charge—it's horrible—it's monstrous—it's—"

He said no more. Overtaxed by emotion and strain, his strength gave way, and he fell back on the couch and his senses fled from his a second time!

"Gone off again—fainted!" pronounced the doctor, bending over him.

"Ah, couldn't stand the pressure, sir, eh? He didn't expect to be charged so soon with what he's done. Almost like being caught red-handed!"

"I suppose there can be no doubt he did it, constable!"

"How can there be, sir? That yarn of his about coming to the place for shelter is about the lamest I've ever heard."

"Certainly sounded very thin!"

"He'll swing, sir; he'll swing, you can bet. I've absolute proof already that he went into the dead man's bed-room!"

"Proof!"

"Ay, sir, here!" The constable took up the accused man's boots and turned them over to display the sodden, broken soles. "He left plain prints of these behind him!"

"Heavens! Did he though?"

"Yes, one on the window-sill and another actually on the stained boards close to the bedside! 'Twas one of the first things I noticed, and there's absolutely no mistakin' this broken left sole!" The doctor took another look at the unconscious man.

"He'll be coming to in a minute," he said. "You'll be taking him off then, I suppose?"

"Not till the inspector comes, sir. I've already sent a chap to telephone to Lummingstall for him. Till he arrives I must wait here to look after the dead body as well as the prisoner!"

"Quite! That reminds me. Mr. Dolby's in the other room still. He's terribly cut up at this tragedy, poor fellow."

"Not surprising, sir. They do say as old Mr. Sharron had always been more than a kind friend to him. Reg'lar made him, accordin' to all accounts."

"So I've heard. Well, I must see him and try to get him away from these morbid surroundings."

"You mean he'd better not stay on here at the bungalow, sir."

"Quite! I must persuade him to come and stay with me till after the inquest, at any rate."

"Mr. Dolby, my dear fellow, I know how very distressing this must be to you, but you mustn't let it get you down. I get you not to brood on it, or you'll get ill yourself. You mustn't brood on it, you really mustn't?"

It was Dr. Alford speaking to the young solicitor. The scene was the doctor's house in Dentwhistle village, whither he had persuaded Nicholas Dolby to return with him overnight. The time was the next morning, and the two men were seated at breakfast together. They had risen quite early in spite of the fact that they had retired late.

The solicitor certainly seemed in need of the advice given him. His distress was most obvious. His face seemed positively torn with anguish, while his eyes were the eyes of a man who had hardly slept at all, but whose mind had been kept on the rack by fierce grief.

"Thanks, doctor," he answered, in a none too firm voice, "I'll do my best to smother my feelings, but it's a job. This is a blow—the most terrible blow of my life. I can't tell you what Mr. Sharron has been to me. The kindest friend man ever had. Whatever little success I have achieved in life has been solely due to him."

"Oh. come, your own efforts and ability and—"

"Yes, I know all that. But it was Mr. Sharron who gave me the chance to show them. Without him I might have been in the workhouse. He befriended me when I was a poor orphan. He had me educated, he articled me at his office without a ha'penny of fee. He pushed me on and on, and two years ago, when he could no longer attend to business himself, he made me his partner so that I might have a free hand with everything. Yes, he was the kindest friend a man ever had, and now—now to think he should have come to such an end! And last night of all nights! If anything could make it more bitter it was that!"

He was on the verge of breaking down—at a point, in fact, when the doctor thought it better to humour his mood, sad though it was.

"What exactly do you mean, Mr. Dolby? Such an occurrence would be terrible at any time. Why should last night be worse than—"

"Because he was my guest—the only time he has ever been my guest!"

"Really!"

"Yes. As you know, I'm a bachelor, a lonely man. Till Mr. Sharron retired from business more than two years ago, and made me his partner, I never had a home to which I could invite him. I was always in lodgings up to then. But when, through his kindness, my means allowed, I built the green bungalow out on the moors yonder, and bought a car to carry me to and fro. I grew to love my lonely little home, and I always looked forward to the time when I could invite Mr. Sharron to it. For a long time I feared his health would never allow of such a thing. But yesterday, when he came to the office, I found he was well enough. So I asked him, out, and—and—"

"How did it come about?" the doctor inquired gently, to keep the young lawyer from breaking down.

"Mr. Sharron came to the office quite unexpectedly yesterday afternoon. A friend had motored him over from Southport, sixty miles away. I was delighted to see him, especially as he was so much better. He was indeed greatly better after his long rest, and actually announced his intention of getting into touch with the business again. To that end we went through a lot of old deeds and documents together. But the work tired him after a few hours. I saw that a long motor journey back to Southport would be too much for him, so I invited him to pass the night at my bungalow out here."

"Which he accepted?"

"Eagerly—almost joyfully, I might say. And when we got out—I drove him in my little car—he was as enthusiastic about my little home as I was myself." At that moment there came a knock at the door, and a maidservant entered. "It's a police officer, sir; wants to see you. Inspector Yarrow from Lummingstall!" Dr. Alford bent forward and touched his guest on the arm.

"The police, my dear friend! They've probably news." He turned to the maid: "Show the inspector in, please!"

Inspector Yarrow entered. He was a big man with a heavy moustache and clear, shrewd eyes. "'Morning, inspector! Any fresh developments?"

"Oh, so, so, sir!" Yarrow's eyes twinkled triumphantly. "Not very much perhaps, but enough. Enough to tell us we've got the right man. John Wilson killed Mr. Sharron without a shadow of a doubt!"

"You seem very certain. What's happened?"

"Why, in addition to foot-prints in the dead man's bed-room, which we've proved were made by Wilson's broken boots, we found Mr. Sharron's wallet in his pocket!"

"In Wilson's pocket, do you mean?"

"Yes. It contained fifteen pounds in Treasury notes, besides one or two documents. John Wilson's the man without any doubt at all. He'll swing for it!"

NEWS travels fast nowadays, faster than it ever did. Within an hour or two of the events related in the previous chapter, all London was echoing with the "Green Bungalow Tragedy."

Evening paper posters made those three ominous words familiar everywhere, while special editions told London's millions all there was to know about it.

Practically all, that is. There was no mystery out it. The murderer had been caught, not quite red-handed it is true, but nearly so, thanks to the prompt action and courage of the dead lawyer's partner, Mr. Nicholas Dolby. All the newspapers were full of that—the courage of the junior partner, and his deep grief at the loss of his old friend and benefactor.

The one consolatory feature of the whole grim and ghastly business was that the murderer had been arrested. For that John Wilson, out-of-work ex-service man and tramp-burglar, had done Richard Sharron to death, nobody had any sort of doubt. It was a plain case. A tragic drama, but with no mystery about it. Old Richard Sharron, a highly respected Yorkshire solicitor, had been murdered. John Wilson had been arrested for that murder. Later he would be tried, condemned to death, and hanged! That was all there was to it. Having read the grim story, most people were ready to dismiss it from their minds, so complete did it seem.

So thought even Sexton Blake, the famous detective; so certainly thought Tinker, his assistant, as he, like his master, went through the afternoon papers at their Baker Street chambers.

It was part of his job to cut from the newspapers the stories of current crimes as they came to be reported, and to index them up for possible future reference. In this way Sexton Blake's shelves had accumulated thousands of cases, of which only a small percentage were ever afterwards referred to. It was to this "limbo" that Tinker, in his mind, already relegated the "Green Bungalow Tragedy," even as he read it.

"Hardly worth indexing up, is it, guv?" he remarked, after some exchange of views on the detailed accounts both had just read. "Never likely to want it, are we?"

"Perhaps not," agreed Blake, who was so full of Tinker's mind that he had already turned his attention to other matters in the newspaper he was reading. "We're not in the least likely ever to want it. Still, just keep it as a record. Now about that passport forgery business. Look up all the papers connected with it, and—"

But Tinker wasn't to do anything of the sort. Before Sexton Blake could even finish his sentence there came the sound of a taxicab suddenly pulling up at their door in Baker Street, followed by a long and peremptory ringing of their bell.

"Somebody in a hurry, guv."

"Yes, an impatient and excited client, I should say."

"Some duchess lost her favourite Pekinese, and wants you to find it, or—"

Tinker was interrupted this time by steps on the stairs. Following a "Come in!" to her tap, Mrs. Bardell, the housekeeper entered.

"Gentleman to see you, sir. Seems very hagitated, and begs you to see him at once!"

Blake took a proffered card from the tray, and gave a jump!

"How queer!"

"What is? Who it is, guv?"

"Mr. Adrian Straker, Manager, Paragon Iron Foundry, Burnley," read out Blake. Tinker snatched at the evening paper.

"Why, that's the man referred to in the Green Bungalow case, surely?"

"Quite! That's the odd thing about it. He's the gentleman mentioned by John Wilson, the accused man." Blake thought hard for the fraction of a second, then said quietly to Mrs. Bardell: "Show the gentleman up at once!"

Half a minute later and Adrian Straker was in the room. A young man—about thirty-five. Tall, well-built, good-looking, brainy and energetic and terribly excited. So excited that, as was plain, he had all his work cut out to hold himself in.

"How do you do, Mr. Straker?" Blake, who liked the look of him, gave him his hand. "What can I do for you?"

"Let me thank you, sir, for seeing me. I've come about—about that!" His quick eyes had fallen on the afternoon papers spread out on the table with the big headings uppermost: "Green Bungalow Tragedy!"

"Have you read it, sir?"

"Why yes, only a few minutes ago. You are the Mr. Straker mentioned there? Why have you called on me?"

"To ask you to take up the case—to beg you to take up the case on Jack—that is, on John Wilson's behalf. To get you to clear him of this horrible charge!"

"Eh, what—a big order, isn't it?"

"It may seem so, sir, but I'm sure you could—"

"But the case is black against him. Everything points to him. Why are you interesting yourself on his behalf?"

"Because I believe he's innocent!"

Blake stared at his visitor, wondering if in his intense excitement he had taken leave of his senses. "On what grounds do you base your belief, Mr. Straker?"

"Because he says he's innocent!"

"Bit flimsy that, isn't it? I've read the details, and though it's early days, the police case seems complete—absolutely complete already. Everything points to Wilson's guilt!"

"I don't care! I'd believe Jack Wilson's word against everything!" Again came Blake's doubt as to his visitor's sanity, and again he decided in his favour. "What do you know of him?"

"Nothing but good. I knew him all through the War. I was a lieutenant, he was a private. Part of the time he was my batman, and once"—Straker voice quavered with emotion as memory stirred within him—"once at Ypres he saved my life at the greatest risk to his own. Jack's the bravest chap who ever lived. As to doing this—this terrible murder, why, he couldn't—he couldn't!"

Such passion had come into Adrian Straker's voice as touched Blake. In a world which, generally speaking, is so forgetful and ungrateful, the detective revered gratitude as one of the greatest virtues. And he saw that the foundry manager's whole being was steeped in gratitude. Nevertheless, he felt he must not let this sway him too much. He must keep a level head.

"Aren't you letting your war memories run away with you, Mr. Straker," he said in gentlest reproof. "You mustn't, you know. I can quite understand your feelings towards a man who saved your life, but when that man has committed a ghastly crime—"

"He hasn't—he hasn't!" protested Straker hotly. "I tell you he couldn't do such a thing. Without his word, I should have known that, but I've seen him—this morning. I was allowed to have a few minutes' interview with him, and he told me—he swore to me that he was innocent!"

"But in face of all the circumstances? Why, the fact that the papers deal with the matter so fully—they tell us practically the whole of the police case—shows how little doubt there is about his guilt!"

"Oh, I know it looks black—terribly black! But Jack denies it all! He denies that he entered the bungalow at all, let alone the bed-room where the dead man was found!"

"But his foot-prints were found actually in the room. More significant still, the dead man's wallet was found in his pocket. How does he explain these things?"

"He—he can't explain them!" cried Straker, pacing the room all pale and agitated. "They baffle him completely. There is some mystery about it all. That's what I want you to elucidate, sir. That's why I've come to you. I promised poor Jack long ago that I'd stand his friend if ever he needed one. And now he does need one. I want to keep my word. Take up the case in his interest, I beg you to!"

"I can't—I'm deeply sorry, but I can't. I've other things to do, and to do this would be—a waste of time!"

"Oh, no, no; don't say that, sir! I'm not a rich man, but I'm comfortably off. I've got a first-class job. I can find a few hundreds for Jack's sake. A thousand or two for that matter. If money will help to clear him—"

"It's won't, I fear! It's good of you to offer to stand by him like this, Mr. Straker. I admire you for it. But it would be wasting your money. The case is hopeless. It's so strong against him that nothing I nor anybody else could do could break it down. Once again, I am sorry, but I cannot take up the case!"

"You will not save an innocent man's life?" cried Straker despairingly.

"You mustn't put it that way—you really mustn't. If I could believe he was innocent—"

"He is—he is!"

"In face of the evidence already published, I cannot believe it. To my mind it is black—dead black against him! How then could I hope to save him?"

Something like despair was in Adrian Straker's eyes as he suddenly jerked up his head, and said in hollow tones:

"Then save me!"

"Save you—what do you mean?"

"Just that! Save me, Mr. Blake! Save me from a life of misery and self-reproachings! Oh, don't you understand how I feel? I believe Jack innocent, against all the world. Yet because the police and all the world believe him guilty, he may go to a shameful death! Don't you see if I do nothing and such a terrible thing as that should come about, that I could never forgive myself? I, who owe my life to him, who swore to be his friend! How could I ever forgive myself if I should fail in that? How could I ever sleep? How could I ever have one moment's peace day or night. That—that is what I mean, sir, by saving me! Take up the case! Do your best, even though you should fail. I did not think you would fail. But even if you did, I should at least have the consolation of—"

Sexton Blake gripped his hand and pressed it fervently.

"I admire your firm friendship for Wilson," he said. "If just to satisfy you I will make inquiries. I'll make a start at once!"

SEXTON BLAKE caught the four o'clock express from King's Cross. It was due at Bradford at 8.26 that night. At Bradford he intended to hire a car and drive out to Lummingstall, lying among the mountains some twenty miles or so away. It was a nuisance having to change, but it seemed the best way, and he had chosen it from several alternative routes.

In the reserved first-class compartment with him were Tinker and Pedro, his famous bloodhound. Adrian Straker was not with them. He intended to return to Burnley by a later train, and had arranged to meet Blake the next day. Full of profound gratitude to Blake for consenting to take up the case, and eager to help all he could himself, he would willingly have accompanied him, but for a task—a duty, rather, as he regarded it—which would detain him in London a few hours longer.

That duty was to go up to Islington, seek out the wife and child of his old friend and soldier-servant, Jack Wilson, and render the monetary help of which they stood in such dire need.

So it came to pass that Blake travelled without him. He wasn't a bit eager or happy. In fact, he was very reluctant and miserable. He had consented to take up the case purely out of pity for Adrian Straker. As to the case itself, Blake had no hope of doing any good with it; not a shadow of hope of saving John Wilson. Even from the evidence published—and the police might well have something else up their sleeve—his doom was as good as sealed. Beyond all reasonable doubt Wilson had committed the murder. He would be tried. He would be found guilty and condemned to death. That seemed sure. Nothing could save him.

No wonder Sexton Blake was glum on the journey. He felt he was engaged on a fool's errand, and nobody likes to feel that. So, apart from some desultory conversation as they sat at dinner in the restaurant car, he spoke but little on the more than four-hours' journey. Tinker, who fully shared the hopelessness regarding their mission, quite understood the reason for his silence, and therefore made but few attempts to rouse him out of it.

Arrived at last at Bradford, Blake sought outside the station for a taxi to take him out to Lummingstall, but found a difficulty. Several drivers were engaged for jobs later in the evening which would prevent their going so far; others hadn't enough petrol for so long a journey; still others were disinclined for a night jaunt among the mountains with so much rough weather about.

"I know where you can get a good car, sir!"

It was a station "cab-runner," who had been following them about, waiting to pick up a tip.

"Where?"

"Garridge just round t'corner, sir."

"Right-ho! Lead on!"

Rinker's Garage, to which the man led them, wasn't a very classy place, but it served. They got an old, big, closed saloon car which promised to suit their purpose, and a driver who knew the way. In a very few minutes they were off.

Through Buttershaw and as far as Halifax the road was quite "towny," but from there a secondary road quickly led them to Bodgery Moor. Here all was wildness and loneliness. Hills—almost mountains—led to great high stretches of bleak moor, interspersed here and there with woods, over which the wind tore, if not with the fury of last night's gale, at any rate, with sufficient power to imbue the journey with the spirit of adventure.

An adventurous journey it was to be! Rocking in the wind, the somewhat ancient car was making quite good speed along a section of road heavily shadowed by woods on either side, when it came suddenly to a stop by the abrupt jamming on of the brakes!

"Hallo! What's up?" cried Blake, leaning over the saloon partition towards the driver's seat.

Round came the driver's face with a scared look on it. But the direct answer to Blake's question came from somewhere else, and somebody else.

"Hands up!"

The startling words came from a masked man standing in the road just ahead of the car and beside the bonnet. In his hand was a revolver, which was covering the driver.

Near him were three other men, also masked, and also with raised revolvers covering Blake and Tinker in the rear part of the car.

"Duck, and hold Pedro down!" whispered Blake hoarsely, and then did an astounding thing.

Vaulting instantly over the low partition, he bundled the unnerved driver out of the seat, jumped into it himself, seized the steering-wheel, and in a second had the car in motion again.

Plop—plop—plop! came three bullets aimed wildly, as the astonished highwaymen scattered to save themselves from the plunging car. There came a jangling of glass.

Plop—plop—plop—plop—plop! came again as the car cleared them and shot forward. For a quarter of a mile the old bus in Blake's hands did marvels in the way of speed. Then he, too, pulled up, and swung his head round.

"All right, laddie?"

"Yes, thanks, guv'nor. Some of the bullets plugged into the car, but we weren't hit."

"You're all right, driver?" asked Blake.

"Yes, sir," answered the shivering man beside him, and lifted a scared white face. "But what a close shave, sir! Whatever would have happened if you hadn't hopped into my seat. I couldn't have driven on to save my life."

"Driving on was the only way to save it," said Blake dryly. "Those ruffians meant mischief." He alighted and stared back along the road.

"No sign of them!" said Tinker, joining him and looking back.

"No, they've scooted before now. Hiding in the woods, no doubt. We must give information to the police at the next village." He turned to the still trembling driver as once again he took the driving-wheel. "Any hold-up like this taken place about here before?"

"Not here, sir, so far as I know. But there have bin one or two cases the last few weeks. One out by Beedleham, and another by Snaggar Snout, in the north Ridin'. Supposed to be done by the same gang, them two jobs was. They robbed the motorin' party and trussed 'em, all up. This may have bin the same crew."

"Shouldn't be surprised. Anyway, we're well out of it." And, without further talk, Blake got going again.

The only other halt was at the next village, where Blake pulled up at the wayside police-station to lay information. Then he drove on to Lummingstall.

Driving straight to the police-station there, he dismissed the car, the driver of which, however, announced his intention of delaying his return till the following morning. He seemed thoroughly shaken and in no mood to risk a recurrence of another hold-up.

SEXTON BLAKE struck lucky. Inspector Yarrow was in. He was immensely pleased and flattered to meet the famous criminologist. But even his joy at that was eclipsed by his amazement on hearing why he had come.

He was almost incredulous that a man of Blake's outstanding perspicacity should have started on such a "wild goose chase."

"Clear John Wilson!" he exclaimed, raising his bushy eyebrows as he repeated Blake's own words. "Why, you can't have realised the strength of the evidence against him!"

"I do realise that it's pretty strong," said Blake rather lamely. "But I was hoping there might be a chance."

"There isn't an earthly, Mr. Blake! Neither your nor anybody else can save John Wilson. That chap's for it, if ever a criminal was!"

Blake smothered a sigh. The local officer's opinion was practically his own. His loathness to admit it and chuck up the sponge at the outset was only born of pity for Adrian Straker, and the fact that he had given his solemn word that he would tackle the case without prejudice, and do his very best on the prisoner's behalf. For this reason he found himself forced into a false position, and compelled to endure Inspector Yarrow's banter and very real—though good-natured—scorn.

"Astonishing to find you believing in his innocence, Mr. Blake!" he exclaimed.

"In accordance with our country's laws, I am entitled to assume it till his guilt is proved, inspector."

"Oh, quite so, quite so!" Yarrow's shrewd eyes were twinkling with triumph. "I don't know how much you know of the case, but if you knew what the magistrates will be told to-morrow morning, you'd agree that his guilt was proved already!"

"That so? Well, I won't ask you what the magistrates will be told in the morning, inspector, because I shall be in court to hear it. But you won't mind giving me the leading points, eh?"

"Not at all, not at all! I'll give you two facts, anyway. You may or may not have seen them already. Mentioned in the papers, I mean. Fact one: The prisoner's boot-prints were found in the bed-room of the murdered man. Fact two: The wallet containing money, which belonged to the murdered man, was found in the prisoner's pocket when we searched him!"

"Yes, I did read as much in the newspapers," assented Blake dismally, feeling more and more the falsity and stupidity of his position.

"Yet you've undertaken to try and clear him! To my mind, those two facts alone are enough to hang the fellow."

Blake was inwardly inclined to agree. More and more he regretted his promise to Adrian Straker, and right willingly would he have taken it back if his sense of honour had allowed.

As it wouldn't, he must put as bold a face as possible on it and go through with the business.

"Quite sure they are his boot-prints, I suppose?" he asked, in the manner of a drowning man clutching at a straw.

"Oh, lor, yes!" Yarrow proceeded. "No good challenging that, my dear sir. I'll save you time on that score right away. The boot-prints were left on a strip of Indian matting that lay beside the bed. I've had them photographed. Here are the prints, developed exact size. And here are the boots which made them. Test them for yourself."

He had stepped to a corner, where there was a big bag containing the "exhibits" for the police court next morning. From it he took the objects named, the big photographic prints, and the pair of dilapidated boots, and placed them before Blake.

The latter took up the prints first. Was that a startled look which immediately sprang in his eyes as he looked at them? If it was, he said not a single word as to what it was that startled him. But he looked long at the prints before setting them down.

Then he took up the boots, and turned them soles upwards. They had originally been stout, but had now worn to a pitiful thinness. The heels were right down, while the soles were actually in holes. Strips of brown paper had been placed inside them by the wearer, in a hopeless attempt to make them wearable. Quite a hopeless attempt. The heavy rain of the previous night had soaked the paper to a pulp.

Blake examined them with the utmost minuteness, then placed them down and looked across at Yarrow.

"Any doubt?" the inspector queried, with quizzing eyes.

"About what?"

"About the prints being made by those boots?"

"None at all. So much is certain."

Again Blake was looking at the photographic prints.

"No doubt about these being John Wilson's boots, I suppose?"

"Guess not!" said Yarrow drily. "They were taken straight off his feet by Constable Stack. Those prints seem to interest you a lot, Mr. Blake!"

"Interest—they positively fascinate me!"

"Good prints, eh? As good as I've ever seen. Remarkable prints, to my mind."

"Quite! Made by remarkable feet!"

Sexton Blake spokes solemnly, yet in his manner as well as the words there was such a suspicion of quaint banter as made the inspector look up.

"Don't get you quite, Mr. Blake. In what way are the feet remarkable?"

"Don't know that I can quite tell you. Only they seem so to me."

It was an enigmatic answer. It conveyed no clear meaning to Inspector Yarrow. Only irritated him.

He asked again, pressingly.

"How do you mean the feet are remarkable?"

"Oh, well, they seem very flat."

The mollified inspector burst out laughing.

"Do they? I didn't notice that. Very likely they are. Lots o' men are flat-footed."

"Quite!" Blake paused half-absentmindedly. Then he asked suddenly: "Where is Wilson?"

"Here, at the station. In the cells at the back."

"Can I see him?"

"Not till the morning, I'm afraid. He's asleep now. Rare job the doctor had to get him off."

"Gave him a draught, you mean?"

"Had to. Doctor Filsome was afraid if he didn't sleep he'd go crazy."

"Bad as that?"

"Storming nearly all day. Raving that he was innocent, and asking us to tell his wife he was innocent. That's why the doctor gave him a draught, but even that didn't look like acting at first."

"How was that?" Inspector Yarrow rasped his chin.

"Well, the doctor can't be sure about it, but he's got a strong suspicion that Wilson's a drug-taker!"

"Gee, that's the first I've heard of that! A penniless tramp! How could he get drugs?"

"What's the matter with burgling a chemist's shop?" said Yarrow, with a shrug of his heavy shoulders. "Anyway, Dr. Filsome said he showed symptoms of a man who doped. Don't know how he knew, but that's what he said. Seemingly that's what stopped the sleeping-draught from acting at first."

"But it has acted since. Well, that means I can't see him till to-morrow. That being so, I'll quit."

"Where are you staying, Mr. Blake?"

"At the Unicorn. I'll cut along now. My assistant, Tinker, went on ahead to see about the luggage, and he'll be waiting for me."

TINKER was waiting for him, most impatiently. Not at the Unicorn Inn (which was only a stone's throw away) but in the street.

Blake met him half-way and instantly saw by his face that he was excited.

"What's up, laddie?"

"Don't quite know, guv, but suspicious things have been happening. That fellow who drove us in the car—"

"What about him?"

"He's a wrong 'un."

"What makes you think so?"

"The pals I saw him meet. Three of 'em. The very three, if I'm not mistaken, who held us up!"

"Heavens, boy, what do you mean? Tell me exactly what's happened."

Tinker did. When Blake had settled with the driver, it was on the understanding that he should drive Tinker and Pedro along to the Unicorn Inn and help with the luggage. But the moment the detective had departed, the fellow's manner had changed. Instead of being respectful to the point of servility, he had become suddenly brusque and defiant. He had certainly driven across to the Unicorn Inn, but that was all. Instead of helping to get the baggage inside, he had dumped it down on the pavement and then driven off, with no more than a morose explanation that he was in a hurry.

"Hurry for what?" interposed Blake. "He wasn't going back to Bradford to-night. He said he was going to stay at Lummingstall till the morning."

"Just so, but I don't thing he meant it. Got something up his sleeve all the time, I fancy. Anyway, his sudden change of manner made me suspicious. So, leaving the porter to look after Pedro and the luggage, I rushed after him."

"Were you able to follow him?"

"Yes. By a bit o' luck he didn't drive far. Pulled up in a back street not far away. Outside a pub called the Blue Boar. He didn't get down, but just yonked away with his horn. It was a signal, as I saw. In a minute a fellow came out, waved to him, then went back into the pub. A minute after he came out again. Two others were with him, and all three got into the car, which at once drove off."

"And you think they were the three who held us up?"

"Well, I couldn't be sure, of course! Couldn't get a look at their faces on the road on account of the masks."

"But you did here in the street?"

"Just a glimpse. Villainous faces they were. Hard-bitten, with steely eyes. Reg'lar racecourse-tough type. I couldn't follow the car, or I would have. Wasn't another car about, for one thing, and for another I couldn't leave Pedro for long."

"Quite! Don't know where the car was going, I suppose?"

"Don't know at all. Nothing was said above a whisper, and they were off in a second or two. But it all struck me as a very funny business."

"No doubt of that. All the queerer if those three men were the actual three who held us up. That would point to a deliberate plot, of course."

Blake thought hard for ten seconds, then said:

"Laddie, we must get back to Bradford to-night!"

"Think they'll have gone back?"

"Don't know, but they may have. Anyway, we've got to see. If it was a plot to hold us up, it looks as if they might have. It's just an off-chance, but it's too important to miss. We'll get back to Bradford to-night. Don't suppose we can overtake them, but if they go back to that garage we might catch them there. Come along, laddie, I must get Inspector Yarrow to help in this."

Inspector Yarrow jumped to the job at once. Blake had previously mentioned the "hold-up," so that he already knew the bare facts. Without knowing in the least what was really in Sexton Blake's mind, he could at any rate see that the driver might have been in league with a highwaymen gang, and have conspired with them to work the hold-up for purposes of robbery. It never occurred to him (as it most certainly did to Blake) that this affair might have any bearing on the murder of Richard Sharron. Nor did it occur to him that it was a personal attack on Sexton Blake. To him, it seemed hardly likely the attackers would know the identity of the detective at all. They would simply regard him as a man who was worth robbing, and make their plans accordingly.

Even so, the affair was sufficiently serious on its own account, and therefore he was quite ready and eager to render the aid now asked.

He gave orders for a big car to be obtained and half a dozen officers to get ready to accompany him and Blake.

While this was being done, he rang up the Bradford police and asked them to set a watch on Rinker's Garage, pending their arrival from Lummingstall.

That being arranged, and the car and police officers ready, the whole party, every man armed with a revolver, set off in a few minutes on their adventurous night ride.

Although they did the twenty miles to Bradford in very fast time, they failed to overtake the fugitives.

Nor could they get any news on arriving at Bradford. The two plain-clothes men set by the Bradford police to watch Rinker's Garage reported "nothing doing." The car for which they had been instructed to look out, had not returned.

It then had to be considered whether inquiries should be made inside the garage as to the character of the missing driver. This was decided against by Blake on his hearing from the local police that the place was already under suspicion.

Rinker—as the proprietor called himself—had only been established in the place a few months. In that brief time he had earned for himself a somewhat shady reputation. There had as yet been no definite charge against him, but he was strongly suspected of having had dealings in stolen cars. The police, therefore, had had him under observation for some time, on and off.

In view of this, Sexton Blake now decided to wait a bit—till next day, at all events. Meantime, the local police would keep a close all-night watch on the place. If the absent driver returned by the next morning, they would detain him for inquiries as to his overnight doings. If he didn't return, they would similarly inform Blake, who would then be guided by events in his future action.

Blake himself, together with the rest of the party from Lummingstall, waited at Bradford an hour or more on the chance of Reuben Gunn (that being the absent driver's name) turning up. But he didn't turn up, and Blake and the others returned to Lummingstall, leaving the Bradford police to the task of watching.

"Think Reuben Gunn will go back in the morning?"

It was Tinker asking the question of Blake that night, when at last they found themselves alone at the Unicorn Inn.

"It's a toss-up, laddie. The fact that he does or does not return, ought to throw light on things, though."

"How?"

"Well, if he doesn't go back, it'll look as if the three men he met were actually the three who held us up."

"That's so. I think they were the same, but of course I can't be sure. But I say, guv! Supposing, for the sake of argument, they were the same, what do you think it all means?"

"It would prove that the hold-up was a planned affair!"

"Yes, of course; but what was the extent of the plan? What was their object in holding us up? Was it just robbery, do you think?"

"Can't make up my mind yet. It might have been just that. That chap loafing about the station yard may have been in co. with an ordinary hold-up gang on the look-out for anybody who seemed worth robbing."

"That would make it very chancy work, wouldn't it? What I mean is most ordinary travellers would have got a taxi in the station yard."

"Quite! That's an argument in favour of its not being an ordinary hold-up for robbery, but something more!"

"You mean—"

"Well, ordinary passengers would only want to go short distances. We failed to get an ordinary taxi because we wanted to go a much longer distance."

"And you think that loafer knew that?"

"He could easily get on to it. Didn't you notice how he followed us round? Directly he saw his chance, he came forward with his offer and took us round to Rinker's. That suggests he'd been specially told off to look out for us."

"Guv'nor, you are making a plot of it! How'd a gang here get to know you were coming to Bradford at all?"

"By their other pals shadowing us in London! They could have seen me booking at King's Cross!"

"But how—"

"The thing's simple. At this end, a gang could easily have known about Adrian Straker's departure for London, while their pals there could easily have shadowed him to Baker Street. The rest would be easy to fix up."

"But Adrian Straker came from Burnley."

"Yes, but he'd been over to Lummingstall to see John Wilson.

"A special visit to a man under arrest, would be quite enough to attract attention from men on the look out for things of that sort."

"Gee whiz! But you're racing ahead, guv'nor! You're linking up to-night's affair with the very murder itself! You're talking of a gang and plots, as if they might have killed Richard Sharron!"

"Why not?"

"Do you think a gang did?"

"It's too early to make up one's mind. One can't decide till one get's more evidence!"

"But you're beginning to think John Wilson may be innocent?"

"I am!"

"Yet you were dead against any such idea when you started?"

"I was."

"What's made you alter your opinion—this hold-up?"

"That's only secondary. It may or may not corroborate my primary idea."

"What is your primary idea?"

"One I got when Inspector Yarrow showed me those photographs of the boot-prints!"

"But they're his trump cars! The very things he most relies on to prove Wilson guilt!"

"And yet the very things which, after all, may prove his innocence!"

AFTER breakfast the next morning, Sexton Blake and Tinker were on their way to the police station to see the prisoner.

All was in readiness for them. Inspector Yarrow was not there, but he had left the necessary instructions. The visitors were conducted to the prisoner's cell at once. The policeman who conducted them at once went away, leaving them alone with the suspected man.

John Wilson was amazed to see Sexton Blake, whose great name and fame was known to him, as it was to all the world. For a moment he was inclined to resent the visit, believing, as was not unnatural, that the great detective was acting in conjunction with the police.

But on Blake's informing him that he had come at the request of Adrian Straker, his eyes lit up and the heavy expression of his grief-stricken face lightened for a moment.

"God bless him!" he murmured brokenly. "Mr. Straker promised to stand my friend years ago, out in Flanders, and he's doin' it now. I knew he would—I knew he would! He's nigh the only friend I've got in this world; the only one who believes me innocent o' this terrible crime!"

Sexton Blake watched him narrowly. Wilson didn't strike him as being of the criminal type at all—certainly not the type that would commit a brutal murder for the sake of a few pounds. Moreover, he was terribly thin and emaciated. Looked as if he were half-starved, and that he and a good square meal were not regular acquaintances these days. Evidence this—negative evidence, of course, but still of some value—that he was not an habitual criminal, for your habitual criminal doesn't allow himself to go hungry.

For so young a man—he was only thirty-two—he looked strangely old. But this was due to his hollow cheeks, his slightly greying hair, and his wild, lustreless eyes. In their turn all of these things might have been caused by anxiety and suffering arising out of his poverty, and especially out of the terrible position in which he now found himself.

Or they might, of course, have been caused by something else!

Drug-taking, for example! Was he a doper? According to Inspector Yarrow, the police-surgeon had suggested it, but was it probable?

Blake thought it highly improbable, and his experience in such matters was certainly equal to the average provincial police-surgeon's.

Still, something had suggested to Dr. Filsome that the man had been under the influence of drugs. He must have had some good reason for thinking that, and, therefore, it was a matter to bear in mind.

Other things, however, must be gone into first.

"Well, well, Wilson," said Blake soothingly, in response to the prisoner's speech. "It's something to have one good friend who believes in you. Let that help you to keep up your heart. Who knows but what others may come to believe in your innocence, too. I have promised Mr. Straker to do all I can to arrive at the truth, so if arriving at the truth will help you—"

"It will, sir, it will!" cried the young man passionately. "It's all I ask for. If only the truth can be discovered! Heaven grant it may, if only for the sake o' my dear missis and little kiddie!"

"As to that, Wilson, you may be able to help as much as anybody!"

"How can I help, sir?" Wilson cried hopelessly. "I've already told the police all I know about it, but they don't believe me. Nobody believes me except Mr. Straker. Everybody else thinks I killed this old gentleman. And I didn't. I swear I didn't! I swear I didn't even know he was in the house—or who was in the house."

Blake listened and watched him intently. If this man was lying, he was one of the most accomplished actors in the world, was his thought. He encouraged him gently with:

"Please tell me what you've already told the police. I want to get at the truth first hand. Tell me everything you know. Every little detail, just as it happened!"

Wilson began. Up to a point, his story—told with many a suppressed sob and break in his voice—was a repetition of what Sexton Blake already knew from the newspaper accounts, and from the added details told him by Adrian Straker and Inspector Yarrow.

In brief, that part of his recital amounted to what has already been set forth in this story.

Ever since the war he had, like too many others, been unable to secure a permanent job. He had had several that promised for a time to be permanent, but for various reasons—bad trade and other things—they had failed him after a time. He had been various things at various times. A warehouse clerk, a porter, an insurance agent, a canvasser on commission, a clerk again and a porter again.

But all the jobs—most of which had been most precarious even while he held them—had failed him in the end. At times he had drawn the dole, but there came a time when even this failed, owing to some technical default beyond his own control.

Several weeks of semi-starvation had followed. During that time he had tramped all over London in a vain search for work. Only the most strenuous efforts by his young and delicate wife had kept the wolf from the door. Quick and clever at needlework, she had managed to earn just enough per week to pay their rent and buy them dry bread.

In that way they had lived—say, rather existed—until John Wilson could stand it no longer. The work denied him in London—Heaven knew he was eager and willing to take anything—he would seek in the provinces. Anyway, if he could no longer support his wife and child, he would no longer be a burden on her meagre earnings.

Like many another down-and-out, he had gone on tramp in search of work. Striking northward, he had reached the busy Midlands, hoping to find a job there. Failing, he had been in doubt as to his next move, when the chance sight of an old newspaper gave him an idea.

The newspaper contained the prospectus of a new iron-foundry company, and contained the name of Adrian Straker as manager. This filled him with a new hope. Because in this Mr. Adrian Straker, he recognised one whom he had known in the Army. Moreover, on account of some signal service he had rendered him, Adrian Straker had promised always to be his friend, and had told him to be sure to apply to him if ever he were in need of a friend.

Of a naturally independent spirit, Jack Wilson had never so far troubled him. Now, in his great need, he decided to apply to him for work.

During his tramping he had communicated with his wife as often as he could afford the stamp to do so, and at this juncture he wrote to tell her of his intention to make for Burnley, in which Lancashire town the iron foundry was situated.

After days of weary tramping, during which he had suffered many privations, he had reached that part of Yorkshire, beyond Lummingstall, in which our story opened.

Near to the village of Dentwhistle he had been overtaken by the great storm. Drenched through and hungry, and well-nigh exhausted by the violent gale, he had looked about for some sort of place where he might get shelter from the storm and rest for his weary limbs.

It was then that he found himself a little beyond the great quarry and within a little distance of the green bungalow. The sight of the shed—the garage—a little way off, suggested that here was the very place, where he might sleep for a few hours. With that idea he made straight for the place.

Then happened—according to Wilson's statement—a most dramatic thing! He had scarcely reached the garage and started to try to open the locked door, when a sudden rush of footsteps behind him made him jerk round his head!

But before he could properly turn, a man had thrown himself right at him! The man was carrying a stout bludgeon. This he swung aloft, and, before Wilson could do anything to defend himself, he brought it across the side of his head with such terrific force as to knock him clean out!

"And that," concluded John Wilson chokingly, "is all I know about it. That's all I remember until I found myself brought to in the kitchen of the bungalow, with the policeman and the doctor and other people bending over me!"

"Then you know nothing of the murder of Richard Sharron?" asked Sexton Blake.

"Nothing—nothing, I swear it, sir!"

"You never went into his bed-room?"

"I never went into any room! I never entered the bungalow at all!"

"Yet, as you know, your boot-prints were found on the window-ledge, and actually beside the dead man's bed?"

"The police told me so yesterday, but it's all a lie—a cruel, horrible lie! I never entered the room at all!"

"How then do you account for the boot-prints being there!"

"I don't account for 'em, sir—I can't! How can I? I swear I never entered the room—never even went near the window. I swear it—I swear it! Merciful Heaven, sir! Don't you believe me?"

Sexton Blake didn't answer for a moment. He remained silent—in deepest thought. The passionate vehemence of the man's denial impressed him. So, indeed, had the whole of his story, so different in its later part from that recounted by the police.

"Don't you believe me, sir?" demanded the distracted prisoner again.

And then Blake suddenly came out of his silence and spoke.

"Wilson, I want to look at your feet! Your bare feet. Will you let me?"

"I don't see what good that would do. But, of course, sir, of course!"

John Wilson removed the old socks and slippers which had been provided him by the police. "Raise you feet!"

The man obeyed, and Blake examined them closely, noting their exact shape. "Tinker, that bag!"

Tinker passed a small handbag they had brought with them. From it Blake took two pieces of cardboard, carefully prepared with some chemical substance, which he placed on the floor of the cell.

"Stand up, Wilson! Right! Now place your feet on these cards—one on each. Press hard as you can—with all your weight!"

The prisoner obeyed, his eyes full of wonder as to the meaning of these things.

"Step off!"

The man stepped off. Blake took up the cards and examined them with a face like a mask. He placed them carefully in the bag, and took something else out—a pair of worn boots. Not so old or broken as Wilson's own had been, but sufficiently worn for his purpose.

"Put these boots on!"

While Wilson dumbly obeyed, Blake took out two more pieces of cardboard, prepared similarly to the others.

"Now stand on these! Press hard again, with all your weight. That's right! Yes, that's enough! You can take the boots off again!"

While Wilson was doing this, Blake was intently examining the second pair of cards. These he also placed in his bag. His face was still like a mask.

But suddenly it relaxed a little as Wilson handed him the boots back.

"Wilson, you told me just now that you had never entered that room?"

"And I tell you so again, sir. I'd say the same thing with my dying breath! I never did. Don't you believe me?"

Sexton Blake's hand shot out. His already relaxed face wreathed into a smile—a smile of real kindness. "My lad, I do believe you! There's my hand on it!"

"You do, sir—and do—" sobbed the poor fellow. "How can I thank you for saying—"

"Don't thank me, but keep up your heart, lad! Don't despair. I believe what you say—that you never entered that room!"

"But the police believe that I did!"

"The police are mistaken. They'll have proof—from me—that you didn't go into that room!"

"How can you prove it, sir—how can you?"

"It may take time to prove it, but I'll do it. Till I do, you must have patience. You must remain under suspicion and a prisoner. You must place yourself in my hands. Be guided by me entirely! Will you agree to that?"

"Gladly and gratefully, sir!"

"Very well, then. Not a word to anybody as to what I've said or done now. Keep absolutely mum about that. In fact, say nothing till I give you the word!"

"I'll be guided by you in everything, sir. I don't see the meaning of what you've done, sir. Those foot-prints, I mean. May I ask what they—"

"Don't ask anything yet, my friend. I'll tell you in good time. Till then trust me. You're to be brought before the magistrates this morning?"

"Yes, sir."

"The proceedings will be merely formal. Not much more than evidence of arrest, I expect. The police will then apply for an adjournment and will get it. Seven or more days adjournment. That will be all to the good. It will give time to instruct a solicitor, and to get you properly defended at the next hearing. Now before I go, just one or two more questions."

"As many as you like, sir."

"The prosecution says you killed Richard Sharron by shooting him. It says too that you fired a revolver at Mr. Dolby just as he knocked you down with a stick. That, of course, isn't true?"

"Of course not, sir. How could it be?"

"You hadn't a revolver in your hand?"

"I had not, sir. I've never possessed such a thing. If I had, it would have gone long enough ago."

"What do you mean by that?"

"Why, I mean I should have sold it—as I have had to sell many others things—to buy food for my wife and child," Wilson answered bitterly.

"Ah, I see what you mean. Now about the shots. You didn't fire them, yet it's certain they were fired! Two of them. We have that on the evidence of Samways, the night-watchman, and his wife. The question is, who fired them?"

"That's beyond me, sir."

"Oh, quite so, but did you hear them—either of them?"

"No, sir. I heard no shot at all."

"Yet you couldn't have been far off the bungalow when they were fired—the second one at all events."

"I heard nothing of the sort, sir. Perhaps that's not so astonishing after all, considering how the wind was roaring."

"Perhaps not," said Blake thoughtfully. "From which direction did you approach the garage? From the quarry side?"