RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

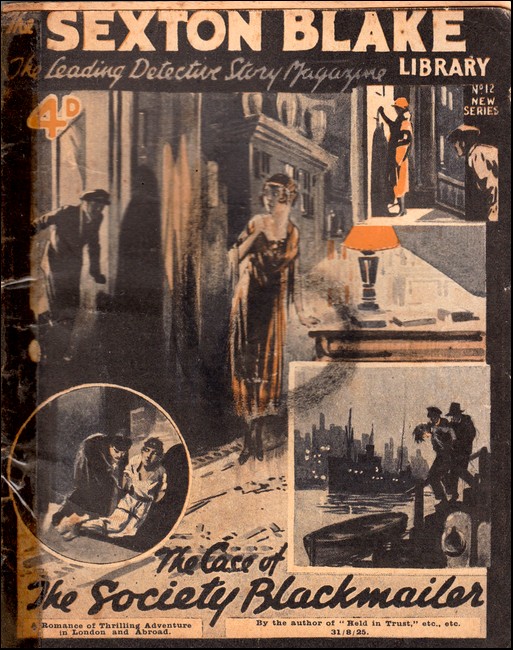

The Sexton Blake Library, 31 Aug 1925, with

"The Case of the Society Blackmailer"

THE sun was sinking to the west, and the cool of the evening had set in. The day's toil was over at the estancia of San Pablo, belonging to the Señor Hernando Lopez, and the gauchos, as cowboys are called in Uruguay, had finished their supper, and were sprawled lazily on the grass outside of their quarters, smoking and chatting, while a couple of them strummed on guitars.

Not far from them was the house of their employer, built of stone, and surrounded by a wide veranda, and shaded by a clump of willows and acacias which grew by a stream of water.

In all directions stretched the grassy uplands, where thousands of sheep and cattle were grazing; and beyond the ranges was the bare, wind-swept pampas, rolling away to distant mountains, and to wooded valleys.

They were much of the same type, these gauchos, of mixed Spanish and Indian blood, with reddish-bronze skin, and straight, black hair, and beady eyes.

They wore sombreros and cotton pantaloons, and the upper part of their bodies were draped in ponchos, squares of woollen cloth with slits cut in the middle to admit the head.

Their spurs were of silver, and at each man's waist hung a lasso or a bola the latter a rope with a round ball at the end of it.

They were not all Uruguayans, however. Amongst them were two Arizona cowboys, and a Mexican vaquero. And there was also an English youth, Oliver Douglas by name, a handsome young fellow of twenty-five, tall and broad-shouldered, clean-shaven, with a florid complexion and fair hair, and dark blue eyes.

A visitor had arrived at the estancia that day, an English sportsman who had come up-country from Montevideo to shoot deer and ostrich, and he was spending the night with Hernando Lopez.

The gauchos had seen him, and they were talking of him with laughter and jest, and Oliver Douglas was listening to the conversation with vague unrest, when one of the household servants approached the group.

"I have a message for you, Douglas," he said in Spanish. "The señor would have you come to him at once."

"He wants to see me?" asked the English youth, with a slight start.

"Yes, that is what he told me," the servant replied.

"What for, Morale?"

"That I do not know. But you had better be quick, for the señor is not in a good temper."

The servant departed, and Oliver Douglas rose from the ground, shrugging his shoulders. The news of the arrival of the visitor—he had not laid eyes on the Englishman himself, or learned his name—had caused him a little uneasiness.

It was very silly of him, he had felt. There wasn't a chance in a million of that which he feared happening.

But his suspicions had been roused now, and there was a worried look on his face, and a sinking at his heart as he crossed over to the house.

He mounted to the veranda, and passed straight from it into the large living-room, which was furnished comfortably and luxuriously as befitted a wealthy stockraiser.

Two persons were seated here at a table littered with dishes. They had dined, and now they were drinking red wine and smoking black cigars.

One was Hernando Lopez, big and burly, swarthy of skin, with a bushy black beard and moustache; and the other was the English guest—a slim, fair gentleman of perhaps thirty, with aristocratic features, and a blonde moustache that drooped over his lip.

One quick glance at him, and Oliver Douglas knew what to expect. But he did not show any emotion.

"You sent for me, señor?" he said quietly to his employer.

Hernando Lopez nodded, and looked inquiringly at his guest, who lifted a monocle that was suspended from his neck by a silk cord, and screwed it into his eye. For a moment he closely scrutinised the youth.

"Yes, Señor Lopez, I was right," he declared in a slow, drawling voice. "I thought I recognised the fellow when I had a glimpse of him this afternoon, and now I am quite sure."

"He is the same rascal you told me of, then?" said Hernando Lopez.

"He is the same," Hugh Anstruther replied. "Not a doubt of it. We were members of the same club in London before he was kicked out. His real name is Denis Sherbroke, and he is the son of Julian Sherbroke, the millionaire. He led such a reckless and dissolute life that his father cut off his allowance, and turned him adrift. Shortly afterwards the fellow got into very serious trouble. He and the other two rogues tried to obtain a large sum of money by fraud from Sir Harry Royce, a friend of mine. While under the influence of drink Royce was induced to sign his name to a paper which he believed to be an IOU for a small gambling debt, and he subsequently discovered he had backed a bill for three thousand pounds. At the same time the discounted bill had not fallen due. Sherbroke's accomplices escaped abroad, and he was arrested.

"But the affair was hushed up. With great difficulty, through the influence which Mr. Julian Sherbroke exerted in high quarters, he had his son released. There was a strict condition imposed by the police, however. It was understood that the boy was to leave the country at once, and that if he ever ventured back he would be rearrested and charged."

Hugh Anstruther paused.

"That was three years ago," he continued, a sneering smile on his lips, "and now I find young Sherbroke here, at your estancia, in an assumed name." Hernando Lopez's face was as dark as a thundercloud.

"What have you got to say for yourself?" he demanded of the youth. "Do you admit you are Denis Sherbroke, or do you deny it?"

"I don't deny anything," Oliver calmly, replied. "All you have been told is true."

"So you deceived me, eh? You brazenly lied to me! You led me to believe you were an honest young fellow who had fallen on bad times through no fault of your own!"

"Can you blame me, señor? I had to have employment, and you wouldn't have given it to me if I had told you the truth. Haven't I been worthy of your trust? You gave me a chance, and I was grateful. I have led a straight and honest life since I have been with you, and if you will keep me on—"

"Keep you on? Is it likely I would, knowing what you are? I'll have no rogue and swindler working for me! It wouldn't be safe! I dare say you have been waiting and watching for an opportunity of—"

Hernando Lopez chocked with rage.

"You're discharged!" He cried, striking the table with his fist. "I've finished with you! I paid you your wages this morning, and you won't get another peso from me! And now begone, you impudent, lying rascal! I'll give you a quarter of an hour, and if you haven't cleared off by then I'll have you thrashed with whips! You'll get no employment elsewhere in Uruguay! I'll see to that! This is an honest country! Take my advice, and cross the border into Brazil or the Argentine, where you'll find plenty of rogues as bad as yourself!"

Appeal would have been useless, and Oliver Douglas knew it. He stepped to the door, hesitated, and looked at the man who had betrayed him.

"You have done a cruel and heartless thing, Anstruther," he said, in a sullen tone. "If I go clean to the devil it will be your fault. Remember that!"

"Clear out, you crooked dog of a swindler!" roared Hernando Lopez. "Don't stand there! Begone!"

The youth left the house, and more in sorrow than in anger. He could not justly blame his employer. He went to the men's quarters, and came out a few moments later with his blanket strapped to his back, and his automatic-pistol in his belt.

The gauchos had meanwhile heard of his discharge, and they mocked him and jeered at him, calling him vile names as he passed by them.

Oliver did not reply to their taunts. He walked rapidly on, scarcely hearing the abuse that rang to his ears, and did not stop until he was beyond the limits of the San Pablo estancia.

Then he sat down on a stone to consider his plans. He was far up-country, two hundred miles to the north of Montevideo, in a remote province of Uruguay.

He had a month's wages in his pocket, and the meagre savings of three years as well; and to the south-west of him, within a couple of days' journey was a railway-station.

"I'm not going over to Brazil or the Argentine," he doggedly reflected. "It will be Montevideo for me. I'll have a good time there while my money lasts. When it is gone I'll try to get work at the docks, and if there should be nothing doing, I'll have to beg or starve."

He set off again as the sun was touching the horizon, and while he held to his course, bitter thoughts of the past crowded into his mind.

What a heavy price he was paying for his sin—for the crime which had made him an outcast from his native land! Yet he had no right to complain, even if he had been spoilt by an indulgent parent.

No, his punishment was deserved. All Hugh Anstruther had said of him was true. He was a criminal.

Heedless of remonstrances and warnings, he had led a life of unbridled extravagance and dissipation until he had exhausted his fathers patience and been turned adrift from home.

His allowance cut off, craving for money to gratify his desires, he had fallen in with evil companions, and been easily persuaded to join in their plot to swindle the wealthy young baronet. Sir Harry Royce, out of a large sum of money.

The trick prematurely discovered, his accomplices had fled the country, leaving him to bear the brunt. He had been arrested—had suffered the indignity of having his finger-prints taken at Scotland Yard—had been set free through his fathers influence, and had been banished to South America on conditions which forbade him ever to return to England.

He had nearly starved in Montevideo before he met Herman Lopez there and induced the stock-raiser to give him employment at the estancia of San Pablo.

Three years ago that was; and since then he had been working hard, almost cheerfully, and clinging to a very slender ray of hope—the hope that he might some day redeem his character and go home, win his father's forgiveness, and marry the girl be loved.

Muriel had loved him, too, with a steadfast and loyal love, yet her influence had not saved him.

She had often pleaded with him, and the last time he had seen her, on the eve of his departure, she had pleaded with him again, told him she still had faith in him, and made him promise to turn over a new leaf for her sake.

For three years he had kept his promise, and had clung to the slim hope. But now....

"There's no use in hoping any longer!" Oliver said to himself aloud, an angry glitter in his eyes. "Curse that fellow Anstruther! He has ruined the one chance I had of making good! I don't suppose I'll ever get another. I may as well go straight to the devil, and be done with it! That's all that's left to me!"

He had been tramping for more than an hour, and now, in the dusk of the evening, he had reached the crest of a wooded hill. He would not go any farther to-night, he decided.

He climbed down into a deep glade, where tall pine-trees grew, and a stream trickled from beneath a mossy rock, and pink, and purple, and golden flowers spangled the grass.

And as he was gazing about him, looking for a suitable place to make his bed, he was startled by a stealthy, rustling noise behind him.

Swinging quickly round, he saw the shadowy figure of a man, and at the same instant he was struck on the head with a blunt weapon.

He staggered and fell, half-stunned by the blow. He was not unconscious. He was dimly aware of rough hands fumbling at him, tearing at his clothes, but he was utterly helpless.

At length, by a sudden and strenuous effort, he scrambled to his feet, and grappled with his assailant.

"Let go, curse you!" a voice snarled in Spanish. "Do you want me to kill you? Let go, I say!"

A violent jerk broke Oliver's hold, and another blow from the weapon sent him reeling to the ground again. He was completely stunned this time.

For a little while his mind was a blank, and when he came to his senses, with an aching head, he was alone, and all was quiet. He could not hear a sound.

He got up, weak and dizzy, and leaned against a tree. He was still somewhat dazed, and as he was wondering why he had been attacked, and by whom, a sickening fear flashed upon him.

He thrust his hands into his pockets, and withdrew them empty. He had been robbed. The envelope containing his month's wages, and a wallet in which he had hoarded his savings, had been stolen.

His pistol was gone also. He had been left with only his blanket, and his pipe and tobacco-pouch. It was a heavy, disastrous loss—between sixty and seventy pounds, reckoning pesos in English money.

Oliver had no doubt the thief was one of the gauchos, who had warily followed him from the estancia.

"It must have been Garcia, the Mexican greaser?" he cried in a fury. "The rest are decent enough fellows! Yes, I am sure it was Garcia. He has hated me since I knocked him down for kicking a young calf. And he knew I had been saving! He saw me put a wad of peso-notes into my wallet one day!"

There was nothing to be done. If the Mexican was the thief he would waste no time in hiding his plunder. Moreover, Oliver had not recognised his assailant, and could not swear to his identity.

It would be useless for him to go back. He must make the best of his loss. Remembering he had had some loose silver, he searched his pockets again, and found half a dozen small coins which had been overlooked by the thief. They were of trifling value, but they would be a help to him—a great help.

He had to reconsider his plans now. He could not travel by rail, and he was afraid to follow the line to Montevideo lest he should be arrested as a vagabond, and clapped into prison.

"I had better strike due south, over the lonely country," he said. "There is a sort of bridle path to guide me. It will be a tremendously long journey on foot, but I shan't starve. There are a few villages on the way, I believe, and what little silver I have will buy enough food to keep me alive until I reach the city."

And what then? Would he be able to find work? He was too ill to worry about that now. Having slaked his thirst at the stream, he stretched himself on the grass, spread his blanket on top of him, and presently dropped off to sleep.

A WEEK later, after night had fallen, Oliver Douglas came over the brow of a hill, and saw below him, bathed in the glow of the moon, a village of small adobe houses.

They were scattered about, and in the midst of them was a fairly large building, white-walled, and with a square tower. It was a church, commonly called a mission chapel in Uruguay.

Day by day Oliver had been on tramp, and he had covered more than half the distance to Montevideo, in good weather and bad.

He was footsore, tired and hungry, and disreputable of appearance, for his clothing had been torn by thorny bushes, and soiled with mud; his boots were in a wretched state, hard rains had battered and bleached his sombrero, and there was a growth of stubbly beard on his cheeks.

He wanted a meal badly, but the prospect of getting one was not encouraging.

As not a glimmer of light showed anywhere, he was sure the people of the village were all in bed and asleep, and he dared not waken any of them.

He had tried that before, and had been put to flight with a vicious dog snapping at his heels.

"I'll have to stay hungry until morning," he said to himself. "I must find a place of shelter, though. I can't walk any farther to-night."

He wearily descended the hill, went by a number of the dark and silent dwellings, and stopped at the mission chapel.

The door was not fastened. He entered quietly, with a feeling of reverence, and passed between rows of rude benches, guided by the moonlight which streamed in at the windows, to the rear of the sacred building. There was an altar here, and beyond it, at the base of the tower, was a small door.

Oliver meant to sleep on one of the benches, but as he was about to unstrap his blanket from his back he heard footsteps; and at once, on a prudent impulse, he glided behind a massive, upright beam which supported the roof.

At the same moment the front door was pushed open, and two dusky figures appeared. They came straightforward, and paused within a few paces of Oliver, who could see them clearly.

They were two well-dressed men, and to the youth's surprise they looked like Englishmen. One was tall and lean, with shrewd features, and a black moustache, and the other, a plump little man of less than average height, was clean-shaven, and had a jovial, good-humoured countenance.

"Well, Hewitt, here we are at last," said the latter in English, in a squeaky voice. "Up in the wilds of Uruguay. It's the longest trip the chief has ever sent us on—eh?"

"And the most risky," the other replied, in a surly tone. "I wish I was back in London, Carey. This is a devil of a country!"

"Mustn't grumble, my boy!" chuckled the little man. "Mustn't grumble! It's worth the risk. Think of the pay we get!"

"And think what the chief gets," muttered the tall man. "He takes the larger share."

"Oh, no, he doesn't. You don't believe that, and neither do I. As I've often told you, Hewitt, there is some big pot behind the chief—some person in a high position in Society who drags family skeletons from their closets, and rattles their bones, and chooses the pigeons to be plucked, and pulls the strings, and pockets most of the spoils."

"You are right about that, no doubt."

"I am sure I am. The chief couldn't nose out the dark secrets of Mayfair and Belgravia, though he is a bit of a swell himself. As for the game we are working on now, I would like to know how much Mr. Julian Sherbroke will have to fork over."

"It won't be less than a hundred thousand pounds, I'll bet. Perhaps more, Carey."

"A hundred thousand! My giddy aunt! And we'll be lucky if we get five hundred each, over and above our expenses! Still, that's not to be sneezed at, Hewitt. We can't complain."

Mr. Julian Sherbroke! Oliver was breathing hard, and his brain was reeling. It was all he could do to keep quiet. Had his ears deceived him? No, it was impossible.

These two Englishmen, thousands of miles from home, had mentioned his father's name in connection with the business which had brought them to this lonely Uruguayan village. Julian Sherbroke would have to pay one hundred thousand pounds, one of them had said. And they had talked of their chief, of Mayfair and Belgravia, of somebody in Society, of family skeletons.

"Good heavens! what can it mean?" the bewildered youth reflected. "What on earth can it mean? My father has never been in South America in all his life. Not as far as I know. Yet there can't be two Mr. Julian Sherbrokes in London."

The first shock over, he pulled himself together, and remembered that he was in an awkward, if not dangerous, position.

His curiosity had been roused to the keenest pitch. He wanted to learn more—he must—but he would have to be very careful, else he would be discovered; and in that event he would have to beat a rapid retreat, or put up a fight.

There had been no further conversation between the men. The little man was filling a pipe, and when he had lit it the two of them stepped to the small door at the base of the tower.

Then tall man tried the knob, and, finding the door locked, he promptly and deftly wrenched it open with an implement like a jemmy.

"On with the glim, Carey!" he bade.

A shaft of golden flame stabbed the darkness. It was a flashlight in the hand of the little man, and as it played to and fro it revealed to Oliver, from his hiding-place by the beam, a tiny room with damp-stained walls, a slanting shelf at the rear of it, and chained to the shelf a musty volume bound in leather.

He had no doubt what the volume was. It must be the chapel register—the chronicle of births and deaths, and marriages.

The tall man moved to the shelf, and while his companion held the light steady for him, he opened the book, and turned the pages over one by one, slowly scanning each. "Ah, here we are!" he murmured at length. "Have you found one of them?" the little man asked eagerly. "I've found the two, Carey. They are both on the same page."

"How can that be, Hewitt?

"Because there is only an interval of a year between the two entries. One is at the top, and the other is near the bottom."

"Well, hurry up. This is a spooky sort of a place, and it is getting on my nerves. That shadow on the wall looks like a skeleton."

Oliver's bewilderment had increased. He knew with what object the intruders had entered the church.

Taking a knife from his pocket, the tall man Hewitt carefully cut the page from the volume, folded it, slipped in into his breast-pocket, and shut the book. Then he came out of the room with his companion, and closed the door.

"The next thing is to search the padre's house, Carey," he said.

"I don't like the idea," the little man replied uneasily. "Isn't the leaf from the register enough?"

"It's not enough for the chief. You know what his orders were. He believes the padre has some letters and papers in his possession, and we've got to get them. I don't like the idea myself, though, Carey. The village people are half-breeds, descendants of the savage and bloodthirsty Charrua Indians, and they would hack us to bits if we were to be caught."

"Oh, heavens!" groaned the little man, rolling his eyes. "Cheerful, isn't it? What a Job's comforter you are, Hewitt, to be sure! But if we've got to go through with it—"

"What's that?" the other interrupted.

A loose board had just creaked under Oliver's foot. The flashlight played around him, showing his protruding elbows; and at once, knowing he had been discovered, he stepped from behind the beam, and raised his arms.

"It's all right," he said. "You needn't be afraid of me."

The tall man pointed an automatic-pistol at the youth's chest, and the little man Carey kept the light on him.

For a few seconds they stared at him in silence, scrutinising him from head to foot; and in that brief interval Oliver thought quickly, and decided what part he would play.

For his own safety, for his very life—and for another reason as well—he must contrive to deceive these men. Moreover, he must not let them know or suspect he was an Englishman.

"I guess you needn't be afraid of me," he repeated. "You might as well put that gun down."

"Who are you?" demanded the tall man.

"I'm a tramp," Oliver replied, with a silly grin. "That's all. Just an ornery tramp."

"English or American?"

"I'm an American. Been starving out here three years."

"Where did you come from? What are you doing here?"

"I've come from up-country, and I crept in here to sleep, and to hide. I've been chased."

"Chased?" said the tall man. "Who's been after you?"

"A band of Redskins on horseback," Oliver answered. "Hundreds of them. They had tomahawks, and bows and arrows. They wanted my scalp, but I scared them away. I whistled like an army bugle, and you should have seen them run! It was funny!"

The youth laughed—a cackling, idiotic laugh. His captors glanced at each other and nodded.

"He's a looney?" said the little man, in a low tone.

"A bit cracked, Carey," the other assented.

Oliver laughed again.

"That's what they all say," he muttered. "And they're all liars. I'm no more cracked than they are, I reckon, if I do see ghosts and things. Give me some grub, will you?" he continued. "Or give me some money."

"We'll give you nothing," said the tall man. "You'll have to shift for yourself."

"Then tell me where I am? What's the name of the place?"

"You are at the village of San Jacinto. Where are you going from here?"

"I don't know. Anywhere. I'm only a tramp."

"Have you been watching us? Did you see what we did?"

"I saw you go into that little room, and read a book. But its no business of mine."

"No, it jolly well isn't! if I thought—"

The tall man broke off. He drew his companion aside, and for several minutes they carried on a whispered conversation that was inaudible to the youth. Then the little man turned to him. "Do you want a job, Mr. Vagabond?" he asked. Oliver shook his head.

"No, I don't," he sullenly answered. "Work ain't in my line. It never was."

"There won't be any work about it."

"You're trying to fool me, ain't you?"

"No, I'm not. I'll talk straight to you. Gavin Carey is my name, and my pal is Mack Hewitt. The old padre of this village, Father Jose Amaral, has some papers which don't belong to him, and we have instructions to get them. We are going to his house now to search, and we want you to come with us."

"What for? What am I to do?"

"Watch and listen. That's all. If you'll do that we'll take you down to Montevideo with us, and give you enough money to put you on your feet. We have a couple of horses tethered yonder, out on the pampas, and you can ride behind me. How does it strike you—eh?"

Oliver was elated. It was with difficulty he kept a stolid, stupid countenance. The true motive of the proposition was quite obvious to him.

Though he had deceived these men, led them to believe he was a looney, they weren't taking any chances. They did not dare kill him, for one thing; and on the other hand, they were afraid to leave him at San Jacinto because of what he had seen and heard. That was why they had suggested he should help them, and go with them to Montevideo.

All this swiftly occurred to the youth, and as quickly he formed a desperate resolve. For the sake of his father, whom he judged to be threatened with blackmail, he must get from the men the leaf torn from the church register, and what papers they might steal from Father Amaral.

And he would have an opportunity of doing so if he accepted their proposal.

"Well, how does it strike you?" the little man repeated, after a short pause. "Are you standing in with us?"

"Sure thing," Oliver replied, in an indifferent tone.

"And you'll go with us to Montevideo?"

"Sure thing. I don't care where I go."

"Come along, then. We're in a hurry to finish the business."

HAVING left the mission chapel, and gone with stealthy tread along the village street for a couple of hundred yards, Oliver and the two men stopped by an adobe dwelling which was larger than the rest; and was like the others, in darkness.

The door was not secured, for Father Amaral had no need to be afraid of thieves. Mack Hewitt pushed it softly open, and his companions followed him into a room that was dimly lit by the glow of the moon.

Gavin Carey played his flashlight, and the little group saw that they were in the living-room of the house.

It was furnished with Spartan simplicity. No carpet or rug was spread on the stone floor, and the walls were bare, except for two or three religious pictures.

There was an armchair, a stool, a rude table on which were several books, a pipe, and a tobacco-jar. And in a corner, resting on a bench, was a small, rusty chest of iron.

Gavin Carey pointed to it.

"The papers will be there, I'll bet," he chuckled.

"Shut up, you fool!" bade Mack Hewitt in a whisper. "Do you want to waken the padre?"

All was quiet. Not a sound could be heard. Oliver and the little man stood by the table, the latter holding the flashlight, and Mack Hewitt glided warily over to the iron chest.

It was unlocked. He raised the lid, and when he had rested it against the wall he rummaged amongst the contents of the chest, on which the flare of light shone.

"A lot of trash!" he murmured. "Old clothes, a photograph of a Spanish girl, a rosary, a bronze statue of the Virgin, and—"

He paused.

"Ah! What's this?" he added as he held up a packet of letters, loosely tied together with a cord. He took one of the faded envelopes out, and glanced at the letter it contained, then replaced it, and thrust the packet into his breast-pocket, with the leaf from the church register. "Are they what the chief told you to look for?" asked Gavin Carey, in a low tone. Mack Hewitt nodded.

"Yes, I've got them," he replied. "The letter I looked at is signed by Mr. Julian Sherbroke, and the others are in the same handwriting."

"Good business! That's all, isn't it?"

"That's all, Carey. We've finished here."

"Let's get a move on, then. I shan't feel easy until we are in the saddle, Mack."

"Wait a bit! We mustn't leave any traces."

Mack Hewitt rearranged the disordered contents of the chest and lowered the lid.

As he straightened up, a noise was heard, and the next instant a door at the rear of the room was opened, and there appeared the figure of a venerable old man, with white hair and clean-shaven, wrinkled features, carrying a lighted candle.

It was Father Jose Amaral, robed in black, and with a cowl on his head.

"The padre!" gasped Gavin Carey.

Father Amaral lifted one hand in stern rebuke. "Wicked and sacrilegious men!" he exclaimed, utterly unafraid. "Is this a place for you to come to with evil intent? The abode of a priest of God? Would you rob me, who have devoted my life to—"

"Hold your tongue, padre!" Mack Hewitt bade fiercely as he pulled his automatic from his belt. "We don't want to do you any harm, but if you say another word—"

"Don't shoot him, Mack!" Gavin Carey broke in. "I won't have it!"

Oliver's fists were clenched, and he was in a boiling rage. He would knock the two men down if he could, he resolved, and capture them, with the help of the priest.

But before he could make a move Father Amaral, overcome by the shock, tottered against the wall, and let the candle slip from his limp grasp.

He gave a husky shout, and now, realising that he would be unable to clear himself should he be caught, Oliver hastened from the dwelling with his companions. "A nice mess we're in!" muttered the little man.

"Shut up, and save your breath!" said Mack Hewitt. "We must run for our lives!"

Father Amaral was still shouting, louder and louder. An alarm had risen, and it was spreading.

Excited voices were heard from all directions, and as the fugitives raced along the village street two of the inhabitants rushed from a house in front of them—two big, swarthy men, wearing ponchos.

Carey felled one with his fist, and Hewitt rapped the other on the skull with his automatic.

"Come this way, Carey!" he bade as he swerved to the right. "And keep an eye on the looney! Don't let him give us the slip!"

The three darted amongst the scattered dwellings, running as fast as they could, and they were soon clear of the village and out on the open, grassy pampas.

They were not so frightened now. They believed they could escape. Looking back, they saw behind them in the moonlight, in hot pursuit, at least a score of shouting, yelling people.

But beyond them and to the west, at a lesser distance, they could see the two tethered horses.

"Ha! The steeds await us!" panted Gavin Carey, who was jovial sort of a villain. "Once in the saddle and—"

As he spoke an old-fashioned gun roared like a blunderbuss. A slug whistled by Oliver's ear, and at once, to the consternation of the fugitives, the horses jerked up their picket-stakes, and went galloping off in terror.

"Oh, heavens, that's done it!" deplored the little man. "We've lost them, Hewitt! They'll gallop for miles before they stop!"

"Curse the luck!" Mack Hewitt cried. "What the blazes are we to do now? We can't put up a fight against that mob of greasy natives! They are too many for us, even with our pistols!"

"We have just one chance," said Oliver, pointing to the south. "There are woods yonder. We must try to reach them."

"Yes, it's the only chance!" Hewitt assented. "Here goes!"

Altering their course, they ran fleetly, with a hue and cry ringing in their ears. They had drawn their pursuers after them, but by hard efforts they gained a little, and they were a couple of hundred yards in the lead when they plunged into the belt of timber.

It was not very wide. They got through it in half a mile, and broke from the cover on to open and rugged ground.

And now, to their relief, they could scarcely hear the clamour. It was growing fainter, they were sure.

"Our luck's in!" Gavin Carey cheerfully declared. "The natives are going back to the village to find out what the alarm was about."

"Yes, it sounds as if they were," replied Mack Hewitt. "And when they learn that we broke into the padre's house, they will be after as again."

"Do you think so, Mack?"

"It's pretty much of a certainty. We had better push on until we are a long way from San Jacinto." Oliver agreed with his companions. They stopped for a few moments to recover breath, and then continued their fight.

For an hour they trudged across a rolling plain, which brought them to a stretch of scrub, and when they had traversed that they climbed a steep hill, clothed with grass, and came at the top of it to a sandy hollow that was rimmed around with boulders, and shaded by a clump of pine-trees.

"We'll stop here for a time," said Mack Hewitt. "I'm dead tired, and I'm going to snatch forty winks of sleep. You and the looney can keep watch, Carey, though I don't believe we have anything more to fear from the village people.

"It may be days," he added, "before Father Amaral discovers that the letters have been stolen from his chest, and that a page is missing from the chapel register. And it will be so much the better for us!"

Gavin Carey nodded.

"I'll wake you in an hour," he said, "and get a few winks myself. I'm as tired as you are, Mack."

MACK HEWITT stretched himself at the bottom of the hollow, with the sand for a pillow, and fell asleep at once. And Oliver and the little man lay down on the brow of the hill, with their backs against the trunk of a big pine-tree.

Gavin Carey was in a cheery mood, and it was difficult for the youth to believe he was such a scoundrel as he undoubtedly was.

He cracked jokes, and talked of one thing and another. He seemed to have taken a liking to Oliver.

"It will be no use trying to find our horses," he said. "We'll have to walk to the nearest railway station, and travel by train to Montevideo. And we'll leave you there, with a few shillings in your pocket, for we've got to get back to England. Take my advice, my boy, and find work. You don't want to be a tramp all your life, do you?"

He did most of the talking. Oliver played the part of a looney, saying little or nothing, and now and again mumbling incoherently.

But he was thinking—and thinking hard. He knew what he meant to do, after Mack Hewitt had been roused, and Carey had gone to sleep.

He would snatch Hewitt's pistol from his belt, and cover him with it; threaten to shoot him if he uttered a word, and make him promptly hand over the packet of letters—the letters the man had said had been written by Mr. Julian Sherbroke—and the page from the register.

Then he would take to rapid flight, go back to the village of San Jacinto, and give the letters and the leaf to Father Amaral.

"The padre will surely believe my story," he reflected, "and he will be able to explain the mystery about my father, I dare say. I can't imagine what it is. It is the strangest thing I have ever known."

Oliver's opportunity was to come sooner than he had expected, as it happened. Presently, as he was speaking of something, Gavin Carey's voice trailed into a whisper.

His chin sank on his breast, and he began to snore. He was sound asleep.

And now, with a different plan in mind, Oliver crept cautiously into the sandy hollow, and knelt by the prostrate figure of Mack Hewitt.

He could see the letters and the page sticking from the breast-pocket of the man's coat, which was partly open; but as he was reaching them, when his fingers were almost touching them, Hewitt suddenly awoke.

With a startled exclamation he sprang to his feet and struck at the youth, who dodged the blow and scrambled from the hollow. His attempt had failed, and his life was in peril now. "Stop him, Carey!" Mack Hewitt shouted. "Stop him!"

Gavin Carey jumped up at once, but by then Oliver had darted past him, and leapt over the crest of the hill. He went tearing down at reckless speed at the risk of his neck; and as he ran the two men yelled at him, and Hewitt opened fire with his automatic.

Two shots missed, and with the third report Oliver felt a burning pain. The bullet had grazed one side of his head. He floundered on for several yards, staggered blindly, pitched on to a mossy shelf or rock, and lay there limp and motionless.

He was only slightly stunned, though he was unable to rise. He had his senses, and could hear the voices of the two men who were standing above him.

"You've killed the poor fellow!" cried Gavin Carey.

"It serves him right!" Mack Hewitt declared, with an oath. "He's no looney. He's as shrewd as they make them. He's been playing a game with us from the first, else he wouldn't have tried to steal the letters and the leaf. But perhaps he isn't dead. He may be only shamming."

"He isn't, Mack! I'm sure you killed him!"

"I'd better go down and see to make certain."

"No, no, don't! We had better clear out of this as quickly as we can! Come along!"

"Very well, Carey. If any of the village people are searching for us they would have heard the shots I fired."

The talk ceased, and retreating foot steps were heard. Mack Hewitt and Gavin Carey were gone, crossing the top of the hill, and both strongly believed that the young tramp who had tricked them was dead.

The steps faded to silence, and with a thankful heart Oliver sat up. He put his hand to the spot the blood was trickling from, and found the bullet had merely broken the skin. "I'll be getting on now," he thought.

He felt better now, and was able to rise. But his limbs were shaky, and at the first step a fit of giddiness seized him, and he swayed on the edge of the rocky shelf and toppled headlong over.

He could not check himself. Down the hill he went, now rolling and now sliding, clutching at tufts of grass, and at the bottom of the slope he landed lightly in a soft copse of bushes.

He was not hurt. He lay there for a little while, gasping for breath; and when at length he scrambled out from the thicket and got to his feet, he heard rustling, crackling sounds in the scrub beyond him, and saw a number of dusky figures rapidly approaching.

They were already close to him, and before he could take to his heels he was surrounded by a score of the village people.

He was in fear of these swarthy, fierce-visaged natives who were descended from Uruguay. They meant to kill him, he was sure; but they did him no harm, though they handled him roughly, and reviled him in the Spanish tongue.

"You come with us," said one of them, a big man whose poncho was richly embroidered. "You will be punished for trying to rob the holy padre whom we love."

In the wilds of Uruguay the punishment for thieves was summary death, as Oliver knew, and he realised that he was in a desperate plight.

As he had failed to recover the stolen letters he could not prove his innocence. Father Amaral would disbelieve his story, and presume him to be as guilty as were the men he had been with.

He offered no resistance, and said nothing. He would wait, he reflected, and appeal to the padre, who might be inclined to mercy.

In the grasp of the big man, and with the rest of the party trailing behind, Oliver was marched back through the scrub and the woods, and across the pampas to the middle of the village of San Jacinto.

All of the people flocked from their dwellings, and there was a hostile demonstration against the prisoner. A yelling mob pressed about him on all sides. He was cursed and threatened, menaced with knives, and he had no chance of speaking to the padre.

Father Amaral was visible in the background waving his arms and calling loudly, but his voice was drowned by the shrill and angry clamour, and the crush was so great he could not get near the youth, hard though he tried.

Oliver shouted to him, appealed to him, until the big man whom the others called Chica, dealt him a blow and bade him hold his tongue.

"You are a dog of a thief," he cried striking him again, "and you must die! Such is our law! At sunrise to-morrow you will be shot!"

It was a staggering sentence. To be shot at sunrise without the formality of a trial! Would the padre allow that? Could he, would he, prevent it?

No, it wasn't likely. The man Chica, it seemed, was the ruler of San Jacinto. In vain Oliver protested his innocence, demanded to see Father Amaral.

His wrists and ankles were bound with thongs of rawhide, and he was picked up and carried to a sort of a shed and thrust into it. Chica pulled the door shut, remarking that the English dog was securely tied and needed no guard.

The clamour ceased, and the crowd gradually dispersed. Soon all was quiet. The people had returned to their beds.

"There's no hope," Oliver told himself. "The padre can't save me. I'll be shot in the morning."

He thought of home, of his father, of Muriel. Bitter anguish swept over him, and was succeeded by hot wrath. What right had these half-civilised brutes to shoot him? He would escape! He must!

He struggled madly at intervals, making frenzied and futile attempts to loosen the thongs which bound him, until he was completely exhausted.

And he was about to drop off to sleep in sickening despair when the door opened and a black-robbed figure appeared. It was Father Amaral.

"Hush!" he bade in a whisper. "Not a word! Do not speak now! I have come to set you free. You are only a boy, and too young to die in your sins. Moreover, I think you have been led astray by evil companions older than yourself."

The padre was kneeling on the floor. He had no knife, but with his slim, white fingers he tugged and twisted at the youth's fetters, untying the knots.

"It will be better so," he murmured. "Though my people are devoted to me, they will not allow me to interfere with their laws, and they would be very angry if they were to know I had released you. I would have them think it was by your own efforts."

It was done at last. The thongs were all untied. Oliver rose on his cramped limbs, and Father Amaral pressed a parcel in his hand.

"Food for you," he said. "And here also is a little money—as much as I can spare. Get as far on your journey as you can before you stop to rest. And for my sake try to lead a better life in future."

"May Heaven bless you, holy father!" Oliver replied, his voice tremulous with emotion. "I will never forget what you have done for me. I will remember you with deepest gratitude as long as I live. But—"

"The night is drawing to an end," the padre interrupted. "Time is precious to you, and you must not waste it in talk."

"But I must speak! I beg you to listen! You wrong me! I am not as evil as you believe! Not willingly was I with those wicked men!"

"It may be so. I trust it is."

"It is the truth, I swear! I had crept into the church to sleep when the men entered. I saw them go into the small room under the tower, and saw one of them cut a leaf out of the register. Afterwards they discovered me, and had I not pretended that—"

"A leaf cut from the register!" repeated Father Amaral, in a tone of bewilderment. "Can it be possible?"

"You will find it missing," Oliver continued. "That the men took, and more than that. They have stolen a packet of letters from the iron chest in your house."

"What? The letters written by the English señor? This is indeed a most strange thing! I can hardly believe they have been stolen! I will look when I get home!"

"You will not find them in the chest. They are gone, And now, before we part, tell me what it all means. It is a matter which concerns me. What could be the motive for stealing the letters, and the page from the register?"

"Truly, my son, I know not any more than you do."

"You must know, holy father. The men are English, as I am also, and they mentioned a name which—"

"Say no more," bade the padre. "Your life is in peril, and you must be on your way. At any moment we may be discovered. As for the strange things you have told me of, I will consider them. Did I know what they meant I should tell you. Go now, my son! And my blessing go with you, whether you be good or evil!"

Father Amaral spoke the truth. Oliver could not doubt his word. Not from him, it appeared, could he learn the explanation of the mystery.

He was very anxious to question him further, but he dared not delay. He clasped the noble-hearted padre's hand, fervently thanked him again, and slipped from the shed, the gift of silver in his pocket, and the parcel of food under his arm.

When he had walked a few yards, he glanced over his shoulder and saw Father Amaral gliding in the opposite direction.

"I hope I'll be able to repay that good man some day," he said to himself.

There was nobody about, and the moon had gone down. Treading noiselessly, and skulking in the shadow of the dwellings Oliver stole through the slumbering village and when he was clear of it, and out on the open pampas, he put his mind seriously to the position he was in.

In the space of a few hours his whole outlook on life had changed. He had a definite object in view. He must—no, he was going to—checkmate Mack Hewitt and Gavin Carey, and wrest from them the spoils which were to be used as an implement of blackmail.

But how? And when and where? He must think it out carefully. And he did.

There was a railway some miles to the west, and the men would doubtless hasten to the nearest station and go by train to Montevideo, from which port it was their intention to sail for England.

"Those crooked scoundrels believe I am dead," Oliver reflected, "and it will be best to let them think so for a while. I haven't the money to travel as a passenger, but I'll bet I can get down to the city on a goods train, hidden in a truck. It would be no use trying to get the better of the men in Uruguay, though, by legal means or otherwise. So there is only one thing for it. I'll have to sail on the same boat with them as a stowaway. I'll contrive that somehow. I've got to."

It was all planned in Oliver's shrewd head, the daring and reckless scheme. He had a dogged nature. Should there be difficulties, he would conquer them.

Cost him what it might, at the risk of arrest and imprisonment, he was going to return to England with Hewitt and Carey, keep track of them after they landed, learn what the secret was, foil the villains and their chief, and save his father from being blackmailed.

And perhaps he would win back all he had lost by his folly, and marry the girl he loved.

Thus thinking, cheer and hope in his heart again, he trudged across the lonely pampas, weary and footsore, yet resolved to put many miles between himself and San Jacinto by sunrise.

He would be safe then, if his escape had not meanwhile been discovered. And there was little or no likelihood of that, he was confident.

His life had been saved by Father Amaral, and it occurred to him, as he went on, that the loss of his employment at the San Pablo estancia, and the theft of his money, had been blessings in disguise.

But for those misfortunes he would be new at Montevideo, with no knowledge of the sinister secret, and with no prospects for the future.

WHEN a goods train from the far north pulled up in the railway-yard on the outskirts of Montevideo at early dawn one morning, a tarpaulin which covered a truck filled with grain sacks was cautiously lifted, and from beneath it crawled Oliver Douglas.

Having descended from the truck and stretched his stiff and aching limbs, he threw a glance around him, peering into the murky gloom in all directions.

He had his chance. Sure that he would not be observed by any of the train-hands, he darted across half a dozen lines of metals, climbed a grassy embankment, scaled a fence, and bore to the left by a deserted road.

"Well, here I am at last, thank goodness!" he said to himself. "If only those rascals haven't sailed yet! It isn't likely they have."

Oliver was covered with dust and grime, and his stomach craved for food. For three days he had been travelling south, hidden in the truck, and for twenty-four hours he had not eaten a bite.

He still had the few silver coins the kindly padre had given him, however, so he wouldn't starve. But he had no chance of getting food now, at this early hour.

He tightened his belt to stifle the pangs of hunger, and struck into a brisk pace along the road, which presently brought him to the suburbs of the big Spanish capital of Uruguay.

He had a weary tramp before him. He went by miles of small and modest dwellings inhabited by the working classes, by miles of broad avenues lined with stately residences in which immensely rich people lived in Parisian luxury and refinement, and so, finally, to the business quarter of the city, where were restaurants, theatres and cafes, splendid shops, and buildings worthy of any European capital.

At a small place in a side street Oliver brushed the dust from his shabby clothes, washed his face and hands, and ate a hearty meal.

Then he set off again, refreshed and strengthened, and tramped more weary miles; until, about the middle of the afternoon, he came to the vast docks of Montevideo, which stretched along the River Plate as far as the eye could reach, and were crowded with shipping from every part of the world.

With an object in mind, Oliver followed the docks for some, distance, scanning the various vessels, watching them being loaded and unloaded; and at length, with a slight start, he paused behind a tier of casks and looked over the top of them.

"My word, if it isn't the Trinidad!" he muttered. "The boat I came out to Uruguay on! I wonder if Neil Rankin is still the Purser?"'

Yes, there she was, the large ocean liner Trinidad, belonging to the Bannerman Line of Liverpool. For a little while Oliver stood there, gazing wistfully at the vessel; and then he gave another quick start, and ducked his head.

A taxi had just stopped beyond him, and two well-dressed men were getting out of it. They were Mack Hewitt and Gavin Carey, and each carried a kitbag.

The chauffeur having been paid, the men walked straight to the Bannerman Line boat, showed their papers to an officer at the foot of the gangway, and mounted to the deck.

Oliver stared after them.

"They must have booked their passages," he reflected. "They could have got to Montevideo a couple of days, ago by a passenger train. They are going home on the Trinidad, and so am I. I've simply got to. That's all there is about it. But how the deuce can I?"

It was a hard problem, and Oliver sat down on an upturned cask to consider it. Though it would be no difficult matter for him to slip on board the vessel and find a hiding-place, he would almost certainly be discovered during the voyage, and that would spoil his plans.

What was he to do? He gazed into vacancy, his chin resting on his hands; and as he was cudgelling his brains, trying to solve the problem, footsteps approached, and a man stopped in front of him—a lean, rakish little man in a blue uniform and a peaked cap, with a small, scrubby moustache, and a pointed tuft of beard.

"By jingo, it's Dougles, isn't it?" he said with a dry chuckle.

"It isn't anybody else," Oliver replied. "How are you, Rankin?"

"As fit as a fiddle. How's yourself?"

"Is it any use asking that?"

"No, it isn't. So you haven't made good, laddie, eh?"

Oliver shook his head gloomily, and the two were silent for a few seconds. They had been intimate friends on the voyage from England on the Trinidad three years ago.

Neil Rankin, the Scotch purser of the boat, had taken a liking to the youth. He had known him only in the name of Douglas, and had been led to belive that he was going to Uruguay to make a fresh start in life after a quarrel with his father because of his wild and extravagant habits.

"What have you been doing all the time?" he resumed, taking close stock of the shabby young fellow. "Not loafing?"

"No, I've been at an estancia up-country, punching cattle with a lot of greasy gauchos," said Oliver. "I didn't mind the work. I made good right enough. But I got sick of it and cleared out. I hit the trail for the nearest railway-station, and I hadn't gone far when I was attacked and robbed by some scoundrel. He stole my month's wages and all my savings."

"Hard luck that was, laddie."

"It was rough, Rankin. I hadn't any money, so there was nothing for it but to steal a ride in a truck on a goods train. That's how I got down to Montevideo. It was only this morning I—"

Oliver broke off abruptly. Something had occurred to him—a hopeful, cheering inspiration. He hesitated for a moment, thinking quickly.

"When do you sail, Rankin?" he inquired.

"At ten o'clock to-night, with the tide," said the purser.

"Well, I want you to do me a favour—a great favour," Oliver continued. "I'll talk straight to you. I've been a fool, and I'm sorry for it. It was my fault I quarrelled with my governor. I'm going home to tell him what an ass I was, and ask him to forgive me. But I'm dead broke except for some small silver. I can't stay in Montevideo without money, and I can't cable to have some sent to me. So will you—will you hide me on board the Trinidad?"

Neil Rankin shrugged his shoulders.

"You're not asking much, are you?" he said, in a sarcastic tone. "A fine lot of trouble you'd get me in!"

"There wouldn't be any risk," Oliver pleaded. "You could see to that. Don't refuse, there's a good fellow! I can't stay out here another day. You wouldn't leave me in Montevideo to starve, would you? It's a cruel city. I've got to get home as quickly as I can, and the Trinidad is my only chance."

"I'm sorry, laddie, but it can't be done. You know how strict the law is. If you were discovered you would be shipped back to Uruguay, not having any papers, and I would be in a devil of a mess."

"It has often been done before. Listen, Rankin! My name isn't Douglas. I'll tell you who my father is. You may have heard of him. He is Mr. Julian Sherbroke."

The purser whistled through his teeth.

"Mr. Julian Sherbroke!" he repeated, looking at the youth incredulously. "The millionaire! And you say you're his son!"

"So I am," Oliver declared, "It's the truth, Rankin. I swear it is, on my honour."

Neil Rankin was wavering now. He was a good-tempered generous fellow, and he was sorry for the unfortunate youth.

"I'll do it!" he said gruffy.

"You will?" Oliver exclaimed eagerly. "It's awfully decent of you. I don't know how to thank you. How are you going to arrange it?"

"I'll have to hide you somewhere in the hold," the purser answered. "I'll see that you get enough to eat and drink during the voyage, and when we're in the Mersey I'll contrive to smuggle you ashore."

"And will you lend me enough money to travel third-class from Liverpool to London? I'll pay it back. I promise."

"Yes, I don't mind."

"But how am I to get on board here Rankin, without being seen or questioned?"

"I'm not sure. You may have to slip into the water, and climb a rope to the ship's bow. We'll talk of that later. You meet me at this spot, laddie, at exactly nine o'clock. I'll have found a hiding-place for you by then. And now I must be off. So long!"

Neil Rankin nodded and was gone, bending his steps towards the boat. And Oliver, who was hungry again, crossed the docks to look for a cheap restaurant.

He thanked his lucky stars he had fallen in with his old friend the purser. In something like three weeks he would be in England.

******

Between ten and eleven o'clock that night Mack Hewitt and Gavin Carey, attired in evening-dress, sat in the saloon of the big vessel, eating and drinking and talking of their adventurous trip up-country.

And far beneath them in the hold, in a cramped nook amongst the passengers' luggage, Oliver Douglas was reclining cosily, with a blanket for a pillow, listening to the faint sound of rippling water.

The voyage had begun. The liner Trinidad was gliding down the River Plate, homeward bound.

THERE was a look of deep concern on Sexton Blake's face when he stepped from a taxi at eleven o'clock one morning in front of a pretentious dwelling in Chesham Place, Belgravia.

His arrival was expected. The butler, an elderly man with a sad countenance, let the famous detective into the house, spoke a few words to him, took him upstairs, and showed him into a bed-room on the first floor.

Inspector Widgeon, of Scotland Yard, was standing by the window.

"Good-morning, Blake," he said, in a low tone. "Mrs. Milvern told me on the 'phone she was going to ring you up as she wished us both to be here."

"And she told me," Blake replied, "that she had telephoned to the Yard, and you were coming on. Rather an unusual proceeding under the circumstances, don't you think?"

"Yes, I did think so," the inspector assented. "I had no explanation from her. She merely informed me of what had happened."

"As she did me, Widgeon. Have you seen the lady yet?"

"Not yet. I am waiting for her."

"A doctor has been sent for, I suppose?" Blake continued.

"He has been and gone," said Inspector Widgeon. "He could not do anything. He is returning later, I believe."

They stood in silence, gazing at a lounge-chair that was close to the fireplace. Huddled limply in the chair, fully dressed, was the body of a clean-shaven man who was about forty years of age. One of his hands rested by his side, and in the other, which hung from the arm of the chair, and automatic pistol was tightly clenched.

There was a bullet hole in the front of his jacket, over the left breast, and the edges of it were scorched and stained with blood.

The body was that of Mr. Eric Milvern, a younger son of Lord Branksome.

"He was an intimate friend of yours, I think," said the inspector.

"Fairly intimate," Blake answered. "I liked him very much."

"Have you any idea why he should have shot himself?"

"None in the least, Widgeon. He was in prosperous circumstances—he inherited a considerable sum of money from an aunt—and he was happily married. No, I can't imagine why—"

"She is coming!" the inspector interrupted.

The rustle of skirts was heard. The door was opened, and Mrs. Milvern entered the room and quietly shut the door behind her.

She was a fair woman of thirty, tall and graceful, and a recognised society beauty. Her white, tear-stained checks told how terribly she had suffered from the shock. Apparently she had recovered from it.

She was calm now, strangely, amazingly calm; but there was a curious glitter in her dark blue eyes—a look which was more than grief. She came slowly forward, her gaze averted from the motionless object in the lounge-chair.

"I will tell you at once why I sent for you, Mr. Blake," she said, in a dull tone. "You were my husband's friend, and I want you and Inspector Widgeon to avenge his murder."

"Murder?" Blake repeated, in surprise. "Surely not!"

"Not legal murder," said Mrs. Milvern, very softly and coldly. "No, it can't be called that. But none the less Eric was cruelly, wickedly murdered, and I will never rest until justice has been done."

"What do you mean? Am I to understand that some trouble, some worry, preyed on his mind and drove him to—"

"Yes, Mr. Blake, he was hounded to death—hounded and harried and persecuted, until in despair he took his own life. I know now that was the reason. I did not know before. I did not guess. Until a month ago my husband was his normal self, always happy and cheerful, and in bright spirits. Then I noticed a change in him—a sudden change. He was depressed. He never laughed or smiled. He took no pleasure in anything. He lost his appetite, and moped about the house. I thought he was ill, but he assured me he was not.

"Day by day, week by week, he grew more depressed. I knew he must be greatly worried over something, but I could not persuade him to tell me what it was. He would not even admit he was worried. He said I was talking nonsense."

"I was at the theatre last night with some friends," she resumed, in the same dull, firm tone, "and when I came back my husband had left word that he had gone to bed. This morning he did not come down to breakfast at nine o'clock, our usual hour. I waited half an hour, and then, feeling alarmed, I went up to Eric's room. And here I found him dead, just as he is now, shot through the heart. No one heard the report of the pistol in the night. The shot must have been fired while heavy traffic was passing the house.

"I was distracted with grief. I swooned, and was unconscious for a little while. The servants hurried in, and a doctor was sent for. When I recovered I saw an envelope on the table addressed to me. It was a letter written by my husband. Here it is, Mr. Blake. It will clearly explain to you the reason for—"

Pausing again, Mrs. Milvern took the letter from her bosom, and gave it to the detective. It was a very short one, and it ran as follows:

My Darling Angela,

I am nearly mad. I have deceived you. I wanted to tell you the truth, but I could not. I have been worried and persecuted until I can endure it no longer. My life is an intolerable burden to me. It is blackmail—that old affair which I believed to be dead and buried for ever.

I can't pay the money demanded of me, and for your sake I can't face exposure. There is only one thing to be done, and I am doing it. Forgive me, darling, I beg of you, and try to forget me. Good-bye.

From your broken-hearted husband.

Eric.

Blake's face was very stern and harsh when he had read the pitiful letter. It had stirred him deeply. He handed it to the inspector, and spoke to Mrs. Milvern.

"I am reluctant to put any personal questions to you—questions which will hurt," he said, "but it is important that I should. What is the old affair your husband refers to? I think you know."

"Yes, I know," Mrs. Milvern replied. "And I am quite willing to tell you. It happened long ago, years before I was married. My husband was wild in those days and fond of pleasure. He was in Paris, and he went to a night gambling club, and there was a fight there. Several persons were badly hurt, and the police came in. Eric had nothing to do with it. He was perfectly innocent. But he was arrested, and for a little while he was in prison, in false name which he gave to the police. He confessed to me when we became engaged, and I laughed at him, and told him it didn't make any difference to me."

"How many years ago was it?" asked Blake.

"At least fifteen years. It may have been more."

"Well, somebody must have recently learned of the matter, and started blackmailing your husband. As a rising young politician the publication of the fact that he had been in prison would be fatal to his prospects. Have you no suspicious? Can you imagine who the person might be?"

"No, Mr. Blake, I can't. I haven't any idea. I never told anybody of what happened in Paris, and I am sure Eric never did. He was too much ashamed."

"Can't you give me any help at all?" said Blake. "I would like to know how the negotiations were conducted. Had your husband any visitors who were strangers to you?"

"No, only intimate friends of ours," Mrs. Milvern answered. "Eric has frequently been out, though."

"Perhaps there are letters in his desk which would throw some light on the mystery.

"There are none, Mr. Blake. I searched his desk thoroughly before the inspector came."

"Did you search his pockets also?"

"I had the butler do that. He found no letters or papers. If Eric had any he must have burnt them. I wish I could help you. If only I could! I have lost the best husband any woman ever had. There was never an angry word between us. Oh, how I shall miss him! How can I live without him? I say again he was murdered—cruelly murdered by somebody who ought to be hanged! You know that as well as I do, Mr. Blake. You were one of his best friends, and—"

Mrs. Milvern's voice rose to a higher pitch.

"You must avenge Eric's death!" she cried, her eyes flashing with passion. "You can, and you must! If you don't, I will! Oh, my poor husband!"

She made a move towards the lounge-chair, but Blake quickly intercepted her, and seized her by the arm.

She struggled with him, and tore herself from his grasp; and then, bursting into a flood of tears, she turned to the door and went out of the room, sobbing bitterly. Inspector Widgeon shook his head.

"Poor lady!" he remarked. "I don't wonder she is so distressed, and in such a vengeful mood. It is a very ugly business."

"Very ugly indeed," said Blake, whose brows were knit. "And not the first one of the kind. I have just been thinking of several things, and I will recall them to you very briefly. It is less than two years since Sir Bruce Maitland secretly and hurriedly sold his residence in Portman Square, and what other property he had, and utterly disappeared. Why? Nobody knew. He has not been heard of to this day."

"I remember the affair," the inspector observed.

"Some months afterwards," Blake went on, "the Marquis of Barleven, a wealthy young man in rugged health, engaged to a princess, went over the Brussels, and was there found dead in his bed at an obscure hotel—dead of poison administered by his own hand. Why? No one knew. There was no explanation."

"None at all," Inspector Widgeon assented. "It was a mysterious case."

"And last spring," Blake resumed, "the Hon. Gertrude Haysboro, a beautiful girl of twenty, daughter of Lord Danesmere, and the fiancee of a duke's son, was found drowned in a pond on her father's estate in Norfolk, on the morning after a big dance at the house. The pond was very shallow. The girl's footprints were traced straight to the edge of it, and into the water. It was so obviously a case of suicide that the coroner would not entertain any other theory."

"I remember that also," said the inspector. "Miss Haysboro had not quarrelled with her fiancee, and she was in perfect health. None of her family or friends could suggest any motive for her rush act. It was another mystery."

Blake nodded.

"Three unsolved mysteries," he said. "Sir Bruce Maitland, the Marquis of Barleven, and Gertrude Haysboro were all prominent in London society, and moved in the same exclusive circle; as, indeed, did Eric Milvern. And of those three people not one left any letter, any written statement, to throw light on their different motives.

"As for poor Milvern's letter, it shows why he shot himself. And it strengthens a suspicion I have had in mind for some time—that the three other persons we have been speaking of were victims of blackmail, and of the same blackmailer."

"I quite agree," replied Inspector Widgeon. "And now I will tell you something which will interest you. Months ago, shortly after the suicide of Lord Danesmere's daughter, our chief at Scotland Yard was informed by one of the cleverest of our C.I.D. men that there was strong reason to believe a secret blackmailer was at work in Society."

"At about the same time," he said, "I made an entry in my notebook which was precisely to the same effect. And I am sure we were both right—the Scotland Yard man and myself. Yes, for the last couple of years some ruthless and crafty scoundrel, some person of high position in the most exclusive circles of Society, a person with an amazing and cunning ability for gleaning dark secrets of the past, has been rattling the dry bones of family skeletons in Mayfair and Belgravia, and blackmailing members of his own class."

"I haven't any doubt of it," said the inspector. "The letter we have just read is plain proof. The blackmailer may be a woman, though."

"That is possible, even likely. Yet a woman would hardly have worked the game on her own."

"You haven't made any investigations, I suppose?"

"No, Widgeon, I have not. I have been too busy. But I shall take the matter up now that my friend Milvern, like the Marquis of Barleven and Gertrude Haysboro, has been driven to suicide. We know of four persons who have baffled the blackmailer, three at the cost of their lives, and one by disappearing; but we do not know how many have yielded to the demands, and paid for silence. Eric Milvern refused to pay—the price was probably too heavy for his means—and I am determined to bring to justice the human fiend who hounded him to his death."

"You will have the stiffest kind of a task, Blake."

"I know that. Of all criminals the blackmailer is the most secure—and the most merciless, remorseless, and diabolical. He is well safeguarded, hedged about by a ring of steel which almost invariably defies the law. But I will get my man sooner or later. It is only a question of time. It will be slow work, as I have not the slightest clue to help me. What a pity poor Milvern did not—"

Blake broke off, a glitter in his eyes.

"Come, Widgeon, let us go," he added. "There is nothing more to be learned from Mrs. Milvern."

With a glance at the huddled figure in the lounge-chair, they left the room and went downstairs; and a low, anguished cry—the cry of a woman whose heart was breaking with grief—came to their ears as they passed out from the house of tragedy into the bright, autumn sunshine.

"I believe the world is getting worse instead of better," Blake gloomily remarked, as he hailed a taxi.

Inspector Widgeon shrugged his shoulders.

"You are in a pessimistic mood to-day," he said.

A CHURCH clock in the neighbourhood was striking the hour of six in the morning when a burly, broad-shouldered man, with a face like a boiled lobster, and a ragged moustache that was chewed at the ends, pounded noisily up the stair of a cheap lodging-house at the top of the West India Docks Road, and flung open the door of a big, dingy room that was as cheerless as a barn.

At first sight one might have taken the room for a large mortuary, for ranged along the walls were numerous low, wooden boxes shaped like coffin-cases, and in each box was a motionless, recumbent figure covered with a blanket.

The man put his hand to his mouth.

"Now, then, it's time to be shifting!" he bellowed like the bull of Bashan. "Wake up! Hustle yourself! Get a move on! D'you hear me, you lazy dogs! What d'you expect for a tanner a night? Come now, hurry along!"

The slumbering figures came to life. They stirred, awoke, and sat up—a motley crew of ragged, dirty vagrants of all ages, from boys to venerable greybeards.

They coughed and yawned; stretched their limbs and rubbed their drowsy eyes. Some grumbled loudly, and some protested in whining tones.

"Hustle yourselves!" the burly man yelled at them. "Clear out of this! D'you hear?"

In fear of Black Mike, as he was called, the lodgers got up stiffly to their feet, and adjusted their tattered garments. By twos and threes they shuffled to the door and slunk sullenly from the room, until only one was left behind.

A youth in soiled and shabby clothes and a grimy shirt, with unshaven cheeks and unkempt hair, was still sitting in his box. He was gazing into vacancy, his thoughts confused, his mind wandering.

The burly man approached him, an oath on his lips.

"Where do you think you are?" he cried in a mocking voice. "At the Hotel Ritz? What are you waiting for, my lord? For the valet with your shaving-water, eh? Or your morning cup of tea? Or a half-pint of champagne and a biscuit?"

He clenched his fist.

"Why the blazes don't you get up?" he bawled. "Do you want me to chuck you out of the window?"

Oliver Douglas collected his scattered thoughts, and suddenly remembered where he was. He scowled resentfully at the man, but did not answer him.

Throwing off his filthy blanket, he snatched his greasy cap and rose. And then, dodging a kick from Black Mike, he slipped by him, ran down the stairs and passed out of the dwelling into a grey, chill gloom of the early morning.

"The insolent ruffian!" he muttered. "It's the last he'll see of me! I'll have to find another place to sleep, and I dare say it will be the Embankment, unless I go without food."

It was hardly daylight as yet, and the air was cold and biting. Oliver felt it the more because he was so recently from the warm climate of Uruguay.

When he had inhaled deep breaths through his nose and slapped his chest with his arms, he went by the group of shivering, homeless vagabonds ejected from the lodging-house, who were loitering on the pavement, and turned from the West India Docks Road into the Commercial Road East.

Presently he stopped at a coffee-stall, and while he sipped a cup of steaming coffee, and munched a stale bun, he considered things.

He had a lot to consider, too. All had gone well with him since he had sailed from Montevideo on the liner Trinidad.

On the arrival of the boat at Liverpool, early the previous morning, he had been smuggled ashore by Neil Rankin; and the purser had lent him enough money for a third-class ticket to London.

Having waited and watched on the Princess Landing Stage, Oliver had seen Mack Hewitt and Gavin Carey come down the gangway—had warily shadowed them to Lime Street Station—and had travelled up to Euston with them.

There he had been very apprehensive, fearing he would lose all trace of the men; for they had got into a taxi, and he could not afford one.

He had ventured close to them, however, and by good luck he had distinctly heard the address they had given to the chauffeur—the name of a street and the number of a house.

And Oliver, knowing as he did that the street was in a fashionable part of the West End, in expensive Belgravia, knew also that the house must be a private residence.

Did Hewitt and Carey live there? No, that was not to be credited.

It was almost certainly the residence of the mysterious chief, the person who had sent the men to the Uruguayan village of San Jacinto; and the packet of letters stolen from Father Amaral, and the leaf cut from the chapel register, would remain in that person's possession.

Thus Oliver had logically reasoned. His primary object had been accomplished, and he did not take the trouble to go to the address he had learned.

For economy's sake, and because he had a nervous dread of the West End police, he had tramped from Euston to the East End—he had gone slumming there when a boy—and had drifted to Black Mike's lodging-house, attracted by a sign which offered beds for sixpence.

And now, after an uncomfortable night, he was up against a stubborn proposition.

He was a disreputable-looking figure, and the price of the coffee and the bun left him with exactly a shilling.

To keep the house in the West End under surveillance, watch the movements of the chief, ultimately get the packet of letters and the register page, and give them to his father—such were Oliver's nebulous plans.

But if he was to carry them out he must have money—and plenty of it—to buy respectable clothes, and to live in decent comfort while he was engaged on his task.

How was he to get it, though? He had pondered over the question during the voyage, and had foreseen that there was only one way. He thought of that way now, and hesitated.

There was no alternative. He must appeal for assistance to the Society girl, the daughter of wealthy parents, who had vainly tried to be his guardian angel. He was not too proud to do so, under the circumstances, as it would not be an appeal for charity.

"I will write to Muriel, and have her meet me somewhere," he reflected. "I can trust her, and if I tell her part of my story she will believe me."

Oliver was sure she would. He had always been truthful with her, and she had been like a sister to him, though she had loved him as well.

He meant to write at once, at the nearest post-office, but when he had finished his frugal breakfast he changed his mind..

He would wait until evening, and, meanwhile, he would go to West End, where he might possibly meet the girl.

Moreover, he was keenly desirous of seeing the parts of London which had been so familiar to him in the past.

His dread of the police had faded to a mere shadow of uneasiness. Shabby and unshaven as he was, he felt there would be little or no danger of his being recognised by anybody as the son of Julian Sherbroke.

He went on foot. He could not afford to ride, with only a shilling in his pocket.

At a slow pace, his hands thrust into his pockets he slouched along the Commercial Road, reminded of the country by the loads of hay, and carts filled with vegetables, which passed him.

At Aldgate he entered the City at the hour when thousands of people—the advance army of the day's toilers—were hastening to their employment; porters and office-boys, strutting junior clerks, and pretty girl-typists, who mostly wore biscuit-coloured stockings and brown and yellow plaid-coats.

It seemed to Oliver that the crowds were greater than they had been before. Everything interested him.

He gazed in wonder at the new buildings, at the larger and improved types of motorbuses, at the orange-painted cabs which flamed conspicuously amidst the traffic.

He thought of the vast wealth stored around him, in the safes and strong-rooms of banks and business houses, as he tramped through Cornhill and Cheapside.