RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Crime in St. James's.

"WHAT is it, Pedro?"

The slim lad who was walking quietly through the quiet side-street halted suddenly and glanced down at the great bloodhound.

The animal had been ambling peacefully along at the end of its chain, seemingly content enough to be out in the fresh night air with its young companion. They had passed right down through the Mall past the great palace where the King was still in residence, and had gone on through the Palace Yard and so into the quiet St. James's Square.

Pedro stopped, and lifting his heavy head, sniffed suspiciously at the soft night air.

"What is it, old man?" Tinker asked, bending to pat the intelligent hound.

Speech was the only gift the hound lacked, yet in its curious way it managed to make itself understood.

It turned, and, tugging gently at the chain, led Tinker down to the right of the square. The young detective followed the animal with a good-humoured smile on his clean, healthy face. Pedro was a privileged animal and could do just about what it pleased with its master.

"It's almost one o'clock, old chap," Tinker observed; "still, if you fancy another ramble before we head for Baker Street—by all means have it."

They were heading now for the north side of the park, but presently Pedro, taking his companion by surprise, darted forward. The heavy chain slipped from Tinker's fingers, and a second later the great dog was loping down a dark alley, the chain rattling and clanking behind him.

Tinker dropped into a run at the heels of the hound.

"Steady, Pedro." he warned; "this is not the open country, you know. You must not go for a hunting expedition in London."

At the end of the alley he halted and looked into the narrow court into which Pedro had bolted.

The court was surrounded by high buildings, all of them in utter darkness. There was a bright moon shining, but the height of the buildings prevented its silver beams from piercing the darkness there.

Suddenly Tinker heard a soft rumbling note come to him—it was Pedro's way of signalling a find of some sort.

"What on earth has the old beggar found?" the lad thought, as he began to pace warily into the dark courtyard.

He counted thirty paces before he reached the dog. Pedro was standing up on his hind legs, with his fore paws resting on the wall, and his head thrust back. He was looking up at something, but although Tinker strained his eyes he could not discern the object that had riveted the attention of his keener-sighted companion.

Suddenly, as Tinker moved a little closer towards the wall, there fell on his upturned face a drop of something.

With a muffled cry the lad started back, wiping the drop from his cheek. In the gloom he peered at the back of his hand—the dull stain was unmistakable—blood!

For a moment the lad stood stock-still, gazing at the smear on his hand, then, with a shiver of disgust, he dropped his hand and stepped towards the wall. Pressing himself against it he turned his eyes upwards again. This time, thanks to the different angle of sight he obtained, Tinker was able to make out a curious shape hanging above his head.

"It is something hanging from a window," the lad thought, staring up into the little strip of sky which hung between the high buildings.

Slowly he made out the lines of a man's head and shoulders. Then he saw that an arm was hanging loosely from its socket down over the sill. The motionless figure hinted that the lad had come unexpectedly on the beginning of a crime.

"He is either dead or very badly wounded," Tinker thought, his quick brain alive now and moving rapidly.

"I'll have to find a policeman and get him to help me."

He stepped away from the wall and lifted Pedro's chain again.

"Come on, old man," he said aloud; "you've done your share of this—and you'll have to let the humans take their turn now. Good boy, you haven't forgotten your scent yet, I see."

He stopped for a moment to pat the great intelligent head, then, tightening the chain, Tinker hurriedly walked out of the court and up the narrow passage. He was fortunate enough in finding a policeman at the corner of the street, and when he reported his find the constable seemed inclined to doubt him at first.

But another glance at Tinker's face and then at the great bloodhound, brought the policeman on the alert.

"It's Tinker; isn't it?" he said.

The young assistant smiled.

"That's right, old chap," he returned, "and now, if you'll just back up we'll try and find out what sort of affair has happened back there."

"It must be Dresdell Court," the police-constable said, as he began to stride off along the street with Tinker by his side. "The houses have all been turned into offices—I was down there about an hour ago, and it was all quiet then."

"There's a lot of things can happen in an hour," said Tinker grimly.

Just as they turned into the passage the peak-capped form of an inspector appeared from the opposite end of the street. Tinker gave vent to an expression of relief as he recognised the officer as Inspector McFadden.

A few words served to place the officer in command of the facts, and the trio, with Pedro at their heels, turned into the courtyard. Tinker went ahead and presently turned towards the wall. When he glanced up towards the sky he could not see any shadow bulking above him!

Thinking that perhaps he had mistaken the exact position, the lad moved slowly along the wall, keeping his head back and watching the outlines of the buildings.

But a few moments of this served to convince him that he was wasting time. The body had disappeared.

The inspector and the constable had been waiting in the darkness, and Tinker felt a trifle annoyed as he walked back to make his report.

But before he could reach the inspector's side there came out suddenly into the night a wild shrill scream.

"Police! Police! Murder! Murder!"

The cries rioted down into the little courtyard, rendered doubly significant by the silence which brooded over the dark buildings: They heard the scraping of a window and again the voice rang out.

"Help! Murder!"

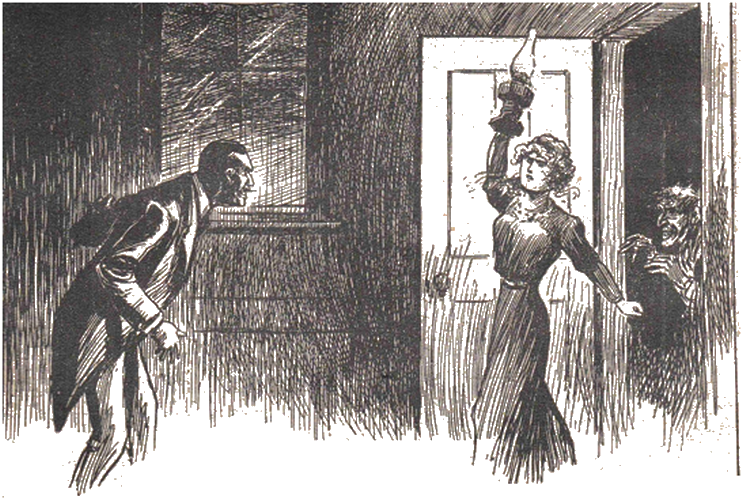

The inspector stepped towards the wall, and in answer to a curt word from him, the night-constable removed his lantern and turned the white bulb upwards. The light from the bullseye slid like a white disc up the wall, and presently in the halo appeared the white, terror-stricken face of a woman.

"All right, madam!" the inspector cried. "We will be with you in a moment. Is there an entry to the building from here?"

The woman clasped her hands with relief at the sound of the strong voice.

"Oh, please come quickly!" she cried. "Come round to the front—to number 347a—I will meet you and let you in. Please hurry—murder has been committed."

Like a flash the inspector turned, and with Tinker close to him, darted down the court and out through the passage.

They sprinted down the side street and turned into the main street with Pedro galloping along by their side. They were now in front of the range of buildings whose backs locked out over the courtyard, and presently they heard the boom of a big door being suddenly thrown open and a woman, with a loose dressing-gown thrown over her head and shoulders, darted across the pavement.

"This way, inspector!" she cried, beckoning as she ran.

"Oh, thank Heaven, I have found you. It was dreadful—dreadful. I—I went down to the office and—and I fell over the poor old gentleman. Oh!"

She was almost beside herself with fear, and the kindly inspector placed his hand on her shoulder.

"All right, madam," he said. "It must have been a terrible shock to you, but we will see to the matter now. Just show me where the room is situated and you can go back to your rooms. I suppose you are the housekeeper?"

"Yes, sir," the woman returned, with a catch of her breath. "Mallow is my name, sir. Oh, to think of such a thing happening in our place! And such a quiet respectable old gentleman, too—it is a shame."

While she talked the inspector had led her towards the building, and now, with Tinker and Pedro at their heels, the housekeeper and her uniformed supporter climbed the stairs. On the second floor the woman stopped and pointed to a door that was half open. There was a light inside the room, and as the inspector stepped towards it, Mrs. Mallow came to a halt.

"I won't go in, sir, if—if you don't mind," she began.

"That's quite right," said the officer. "Go up to your rooms and we'll send for you if you are wanted."

He waited until the frightened old creature had darted off up the dark staircase towards her own chambers, then turned to Tinker.

"You are used to this sort of business, Tinker," he said, as he placed his hand on the door; "so it won't upset you."

As the door opened Tinker saw that tragedy had indeed stepped into that apartment. In line with the window, lying on its face, was the body of a well-dressed man.

Swiftly the inspector stepped across the chamber and knelt beside the prone body. He turned it over gently and the sinister stain in the breast told its own tale.

"Stabbed," said McFadden, laconically.

Tinker looked down at the bearded face.

"Dead?" he breathed.

The inspector made a swift examination.

"Yes," he replied. "He is dead."

He crossed to the window and glanced down into the courtyard. The constable was still standing where he had been placed.

"Go and get an ambulance at once!" the inspector cried. "Call up the Yard and notify them—look alive."

Tinker was looking round the room, and his quick eyes gradually picked up many details.

There were two windows in the chamber, and opposite the second one stood an ordinary office desk. The roll-top was open and there were scattered all about the floor heaps of letters. The drawers were open and one of them had even been wrenched out of its place.

"Someone was mighty anxious to find something," said Tinker to the inspector, pointing to the desk. "And—look! the safe is open as well."

A small safe, standing on a raised platform in the far corner of the room, had also been ransacked.

"We can't do much in the matter until we find out who he is," said the inspector, slowly. "We'll have to see the housekeeper—but I think we can wait before we do that. This poor chap is beyond our aid; and although I'll search the building, I have very little hopes of finding the brutes who did the foul deed."

Tinker walked across the room and picked up a silver object that was lying beneath the window. It was a card-case and he opened it.

"Ivan Torkoff," he read, aloud.

McFadden gave vent to an exclamation, and dropping on his knee, glanced again at the bearded face of the dead man.

"It is Ivan Torkoff who lies here," he said. "A curious coincidence, this."

"How?" asked Tinker.

McFadden nodded his head at the limp body.

"Four days ago this poor chap came into our office and asked for police protection, I believe," he said. "The policeman on day duty here received orders to keep an eye on him—but I see that the fate he feared followed him and found him after all."

"Who is he?" Tinker asked.

"A Russian who has taken out naturalisation papers—and is now an Englishman," the inspector returned as he arose. "That is all I know about him—all that we knew at the office."

He looked at Tinker keenly.

"I wonder if your master, Sexton Blake, knows any more," he said slowly. "There are very few people that he is not acquainted with."

Tinker turned towards the door.

"I just thought of the guv'nor," he said. "There is nothing for me to do here—I think I'll get along to Baker Street and report."

"I hope that Mr. Blake will come into this if he can," said McFadden.

He was of the better type of police official, and had nothing but admiration for the extraordinary qualities of the master detective.

"I'll tell him what you said, inspector," the youngster returned, as he walked out of the room with the faithful bloodhound padding along behind him.

As Tinker reached the outside door there came wheeling up to it the noiseless ambulance with two stalwart constables in charge.

The young detective directed the men where to go, then, with a nod, he and the hound walked rapidly off up the street and vanished.

"You know who that youngster was, I suppose?" said the constable, who had been met by Tinker after the discovery.

"Can't say that I do," his companion returned, as he crossed the pavement.

"He's Blake's assistant; and whenever there's a trouble about he always seems to be in it," said the first speaker.

"Goodness knows how he got on to this affair; but he was the first to find out about it."

"Strikes me the dog had something to do with that."

Which was a very close guess at the truth. For Pedro had certainly been the first to find the scent of as strange a crime as ever the famous detective had been called upon to discover.

On the following morning McFadden appeared at Blake's rooms in Baker Street, and gave the great detective a complete report of the case and the history of the dead man.

It appeared that he was a Russian exile—a man of good position, evidently. He had taken an office in the buildings, and was interested in oil companies, as the papers in his desk denoted. He lived in a small hotel on the Embankment, and spent most of his time at his office. Apparently he had no friends.

"Have you inquired at the Embassy?" Blake asked.

McFadden shrugged his broad shoulders.

"You know what they do when we try that," he said. "Torkoff was an exile—a political one, I should think. We will get little or no information from that quarter."

He glanced at Blake.

"But if you were to have a try, Mr. Blake?"

The great detective thought for a moment.

"I won't promise," he said at last. "It appears to me as though this was a case for the police alone. Still, I might just take a hand for a little while. I'll let you know about it later on."

McFadden knew that Sexton Blake was beyond all hints at monetary considerations. The great detective no longer hunted for criminals of the world, simply because of their crimes. The cases he took up had to be ones that involved some suffering human being in them; it was then that the master-mind busied itself, for to save some poor soul from misery was the highest of all rewards to Sexton Blake.

"I only hope we find out that someone suffers through this," the inspector thought, as he left the rooms. "I'll come up here like a shot then; and he won't turn me away, I'll bet!"

He little dreamed how the near future was to settle his difficulties for him.

Blake was soon to busy himself on the Torkoff case—with results that were to surprise the world.

Jack Brearley's Story.

"AND what can I do for you, Mr. Brearley?" Sexton Blake asked.

The tall, broad-shouldered man, in the neat suit of blue serge, glanced into the keen face of the detective.

"In the first place, Mr. Blake," Jack Brearley said. "I'm a sailor—first mate of the Ikon, a tramp steamer. She's at Tilbury now, and this is the first time I've been in Old England for five years."

Blake nodded at the healthy, tanned face.

"Knocking about the world never harmed a good man," he returned.

"Not if he takes the rough with the smooth," Jack Brearley agreed. "Well, to get on with my story, I want you to help me to find a—a lady—a young lady."

The tan on his face deepened, and as the deep-blue eyes met those of the detective the sailor smiled.

"Yes." he said; "I'm head over heels in love with Neta. Haven't slept a wink since she left the old Ikon; and won't rest until I find her again. You don't think any the worse of me for that, I hope?"

Blake's fine face softened.

"The love of a good man for a pure woman is the best thing in the world," he said, in his rich, grave voice. "I will certainly not laugh at you because of that."

The sailor held out a great brown fist impulsively, and they shook hands.

"That clears the decks nicely," said Jack, with a sigh of relief. "I feel that I can talk to you now."

"Go ahead," said Blake.

"My story really begins at Vladivostok," the mate of the Ikon began. "As you are no doubt aware, that is one of the termini of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Well, my old tramp was being loaded up there—hides, and other evil-smelling things, for London. I went ashore on the last evening to have a look round, and I run plum into an adventure."

He paused for a moment, and rubbed his strong hands together.

"A woman was running down one of the narrow streets towards the docks," he said, "and behind her came padding a couple of great brutes of Russians. They were in ordinary attire, but I could see with half an eye that they were police all right."

"Did you interfere?" Blake asked.

"I didn't mean to," said Jack Brearley slowly; "it isn't safe to do that in a Russian port. But just as I turned the corner the girl caught sight of me, and ran towards me. She caught my arm, and spoke to me in English."

"She was only a slip of a lass," the mate went on, his fine eyes kindling; "not more than twenty, and—and the loveliest girl I've ever clapped eyes on. 'Save me,' was all she could say; and, by jiminy, sir, the words went straight to my heart!"

The great detective watched the grim jaw of his visitor, and a low chuckle escaped from his lips. Jack Brearley looked as though he was a man whom any woman would not have to ask aid twice from.

"Go on," said Blake.

"I hadn't much time to study out things," the mate of the Ikon went on, with a quick smile. "But I did my best. I caught the little lady, and swung her round the corner. She told me afterwards that for the moment she was pretty scared. I must have handled her rather roughly, you see. When I was round the corner I pointed to the passage that led down to the quay, and told her to bolt in that direction just as hard as her limbs could carry her."

His rich laugh broke out.

"And, by James, she did it, too!" he said. "She's only a slip of a girl, as I said before, but she's got the pluck of a regiment of Guards, sir. She just gave me one look, then went off like a bird. I heard the heavy feet of the two Russians drumming on the street, and knew that it was time to get busy."

"What did you do?" Blake asked.

Jack Brearley grinned.

"I used to play back in the old Rugger days," he said; "and I just tackled these fellows in the old style. They were running side by side, and I managed to get between them. It was a real low tackle, and they were down on their backs before they quite knew what happened."

"And then?"

"Well, we had a bit of a dust-heap in the centre of the roadway. But, bless you, Mr. Blake, these fellows are no good at that sort of pastime! I managed to give number one a welt on the side of the jaw that knocked him silly, and the second man bumped his head against the cobbles— of course, I helped him to do that little trick—until his wits went wool-gathering. It was all over in a couple of minutes; and I didn't wait to see what happened to them afterwards."

"You followed the fugitive, I suppose?"

"Rather! I found her hiding behind the Customs shed, and I promptly offered to take her on board the Ikon—a chance she jumped at. In less than twenty minutes she was stowed away safely in my own cabin, and, after a bit of a jaw with the skipper, he agreed to start out of the harbour as soon as it was light."

"And you got her clear away," Blake said.

Jack Brearley nodded.

"Brought her safely to Tilbury," he said; "and saw her into a taxi. She was going to try and find her father; and she promised to let me hear from her as soon as she was settled."

"And you have heard nothing since?"

The bronzed face of the sailor clouded.

"Not a word," he said slowly. "Sometimes I think that—that she may not want to see me any more. I'm only a rough sailor, you see, and she—well, she's good enough for a belted earl." His honest face fell. "But, I—I don't think that Neta was that sort," he added. "You see, she—we—we spent a deal of time together, and she—she said that she loved me. But it's her father that I'm doubtful about. He's a big pot; I believe, and he may have prevented her from writing to me."

"What was her name?" asked Blake.

"Neta Torkoff!" came the astounding response.

Blake started forward, a sudden light in his keen eyes.

"Neta Torkoff!" he repeated.

The mate of the Ikon stared at the detective.

"You—you have heard something about her?" he broke out, a strained, anxious look in his blue eyes. "For Heaven's sake tell me what it is? What have you heard?"

Blake raised his hand for a moment.

"It may be only a coincidence," he said; "but I will let you know about it in good time. Meanwhile, I have a few questions to ask. First of all, did Miss Torkoff tell you why these men were hunting her?"

The sailor shook his head.

"She wasn't quite sure," he returned. "She had travelled from St. Petersburg by the train that starts at 2 p.m. on Saturdays. She had received a cable from her father, who has lived in London for years, I understand, telling her to make for Vladivostok, and wait for him there. At Chelyabinsk—that's a three and a half days' journey from St. Petersburg—Neta noted a couple of men searching the train. They looked very hard at her, and finally entered the adjacent compartment. You know that these Trans-Siberian trains are practically little towns on wheels, with their doctors and barbers and two-berthed compartments."

"I've been across to Mukden," said Blake; "and I remember that dreary eight days travelling across the bleak deserts."

"Well," Jack Brearley went on, "Neta felt sure that the men were spies, and when she arrived at Vladivostok there was another message awaiting for her from her father. It ordered her to come to London at once. She went out of the hotel to prepare for her journey, and when she returned she found that someone had been in her room, and had been rifling her trunks. Nothing was missing except the two cablegrams. But that was quite sufficient to frighten the little lady. She left the hotel, taking all her money with her, and had made up her mind to embark on the packet for Tauruga. She would be safer in Japan, and could ship direct to London from there. Unfortunately she was seen to go into the shipping-office, and it was then that these two men approached her. They meant to arrest her, but she eluded them, and made a dash for liberty. That was when I turned up—and the rest you know."

He halted, and looked at Blake.

"Now," he said, "does that clear up matters for you?"

Blake was silent for a moment.

"It helps me considerably," he said; "and I am sure now that you have given me a clue to a mystery which has just presented itself. By the way, did Miss Torkoff communicate with her father at all from the Ikon?"

Brearley nodded his head.

"Yes," he said; "she sent him a wire from Gibraltar, where we stayed to take in some fresh vegetables."

"Did you know what address she sent it to?"

"To his club," said the mate. "I don't know the name of the club, but I remember its telegraphic address. It was 'Reldvara, London?'"

Blake wrote the word down on the edge of his notebook.

"When was the cable despatched?" he asked.

"On the 22nd," said the mate.

The detective's face was very grave.

"The twenty-second was a Thursday," said Blake. "And on the following day, the twenty-third, a man named Ivan Torkoff was found murdered in his offices at St. James's. I'm afraid that there can be little doubt but that the victim was your sweetheart's father!"

The face of the sailor revealed the horror that the news brought to him.

"Dead!" he said. "Murdered! Good heavens! Then what has become of my little girl?"

The detective shook his head.

"That is what we will have to find out," he said sternly. "It is evident that there has been some trick played upon her. And the persons responsible for the death of her father have succeeded in getting her into their power."

Brearley leaped to his feet, and thrust his great arms above his head.

"I knew it," he declared, in his deep, vibrating voice. "I felt that my darling was in some danger. Every night I have dreamed of her, Mr. Blake. Oh, heavens, it will drive me mad!"

Blake came round the desk, and placed his hand on the strong shoulders.

"It is a terrible experience for you, Brearley," he said. "But you must have courage, old chap. This is the time when a man has to pull himself together. You have interested me now, and I promise you that I will do my utmost to trace Neta Torkoff, your missing sweetheart."

Their eyes met, and Jack Brearley was comforted by the steady light in the calm eyes of the great detective. His hand closed around Blake's fingers in a vice-like grip.

"I can trust you, Mr. Blake," he said hoarsely. "I know that you will do all that a man can do. But I want to help, you know. I feel that I'd go mad on board the Ikon. Won't you let me do something—anything. I don't care what it is so long as it keeps me busy."

Blake realised that the stout sailor might prove an able assistant, and was only too glad to take advantage of the offer.

"Where are you living just now, Brearley?" he asked.

The sailor mentioned an address close to the docks, and the detective took a note of it.

"Go back there and pack your traps," he said. "Be ready to come to me at a moment's notice. I'm going now to begin my investigations, and I may need your help at any time."

"That's all I ask," said the mate of the Ikon, as he turned towards the door. "I'm not one of the brainy kind, but I'll stick to any job you put me on until it's done with."

His tall figure went out through the door, and Blake went across to the window, and watched until the big sailor emerged from the house into the street. Jack Brearley was head and shoulders above the average height of man, and Blake followed the tall form until it had vanished in the throng of Baker Street.

"McFadden will be pleased now," he thought, with a grave smile. "The human element has come into this case at last, and I'll make a move on it without delay."

He crossed to the phone, and rang up the Yard. A few words with the superintendent there served to notify the authorities that Blake was prepared to assist them with the Torkoff mystery. The reply came back with official brevity.

"Glad of your aid. Will forward complete report by special messenger."

Blake crossed his room, and called for Tinker. The young assistant hurriedly appeared from an inner room.

"That Torkoff case," his master said quietly. "A development has taken place, and I'm going to take it up. They are sending a report from the Yard, and I want you to run through it when it comes."

"Right you are, guv'nor!" said Tinker.

Blake walked down the passage, and lifted his hat from the peg.

"I'm going to hunt up a telegraphic address. My directory has disappeared," he said. "Wait for me until I return."

"And the development, guv'nor?" the young assistant put in, with not unnatural curiosity.

Blake smiled.

"I'll tell you all about it when I return, old chap," he said. "You can bottle up your curiosity until then."

Tinker went back into the consulting-room, and stretched himself out on one of the easy-chairs.

"I expect that big fellow who saw the guv'nor just now had something to do with this case," he decided. "Looked like a sailor, and talked like one, too. I hope the guv'nor bucks up and gets back here again. I've been worrying to start on the affair ever since old Pedro made his discovery."

Blake went straight to the post-office, and had a word with the official there. That individual promptly gave him the information he sought.

"Clubs do not like their registered addresses revealed as a rule, Blake," he said. "But—well, you are a privileged person so far as I am concerned. Reldvara is the telegraphic address of the Warsaw Club, and its headquarters are at 462, Onslow Square, Mayfair."

"Many thanks!" said Blake, as he scribbled the address down.

The high official regarded him for a moment.

"I don't know much about the club," he went on, "but I believe that it is a favourite rendezvous for the Russian in London. I rather fancy that the members of the Embassy regard it with a certain amount of suspicion."

"I shouldn't be surprised at that," said Blake, as he rose to his feet. "There are many institutions in England that the average Russian Government official hates. There is too much liberty here for them."

"The Slav is a dangerous sort of brute," his friend returned, as he held out his hand. "I need not tell you that, however."

Blake smiled.

"It will not be the first time that I have crossed swords with them," he said slowly, as he shook hands.

He little dreamed how deeply he was to probe into the grim ways of the men he was about to face.

"And now for the Warsaw Club," he thought, as he sauntered out of the building. "That is my next step. But I don't think that it is advisable that I should go there as Sexton Blake."

A remark which suggested that he appreciated the difficulties of the task that he had undertaken, and was already preparing for them.

Prince Krotol.

"AND Mr. Blake, the great detective, ees not at home?"

Tinker shook his head.

"Not yet, sir," he returned. "I'm expecting him every minute, though—if you'd like to wait."

The black-bearded man drew a gold watch from his pocket, and glanced at it.

"I think I will wait," he announced, sinking into a chair beside the desk.

Tinker eyed him with considerable interest. Scotland Yard had rang up the chambers in Baker Street, announcing that a gentleman who was interested in the Torkoff case had called on them, and they had told him of Blake's decision.

The gentleman had at once announced his anxiety to see the famous detective.

"Prince Krotol," Tinker thought, remembering the name on the card. "There are so many princes in Russia that his title doesn't matter much. But he looks as though he was somebody big."

The Russian was exceedingly well-dressed. His clothes were scrupulously cut, and the solitaire diamond he wore in his tie was a gem of dazzling radiance. His face was of the broad Slav type, and his beard, trimmed and well-kept, was jet black.

The eyes had that curious Mongolian slant which so often reveals itself in the Russian.

Altogether, he was a man who was worth a second look at.

And whether he was to be trusted very far was a question which Tinker felt inclined to answer in the negative.

"Your master ees a very great man," the Prince began, crossing his legs, and looking at the keen, alert face of the lad. "We have heard of him even in Russia."

Now, Tinker and Blake both hated being praised—the usual English way, this. And there was something patronising in the man's voice which Tinker promptly resented.

"Mr. Blake is pretty well known," was the young assistant's laconic response.

The Russian smiled.

"It has pleased me ver' much to think that he has taken up the case of my poor friend," he went on slowly. "The mystery has troubled me terribly. I knew Torkoff when—when he was in Russia many, many years ago now. And I was one of the few friends he ever made."

"You might be of some use to my guv'nor, then," said Tinker. "The Yard does not seem to have found out very much about the murdered man. All they can tell us is that he was an exile from his country; and yet most of his business was done there."

Prince Krotol's slant eyes raised a trifle, the quick lift of the upper eyelid which suggests that every nerve is on the alert.

"I know nothing about Torkoff's business," he returned. "I only came to London a few weeks ago. It is my first visit to your splendid country."

Now, Scotland Yard had sent the gentleman to Blake, so Tinker could not be blamed for chatting as he did. The Yard officials are usually very careful, and they are not likely to send a doubtful person to anyone without due warning.

"I believe that Mr. Torkoff was trying to float a big oil company," said Tinker easily. "Papers were found alluding to that, and one or two gentlemen in the City have given evidence that he had approached them on the matter."

"Oil. Oh, yes; there is a lot of money to be made out of that!"

The reply was non-committal, but again the slant eyes blazed with a curiously intent light.

"The evidence at the inquest proved that he had a big concession—I think you call it a 'ukase.'"

"Yes; that is our name for a concession from the Government or the Czar. It simply means a contract—in your language."

"Well, I don't know a great deal about these things," Tinker admitted; "but one of the City financiers stated in his evidence that he thought the concession a very valuable one—if it could be found."

"It was not found?"

"No. His office was searched without result."

There was a moment's silence then.

"And I hear that the police have been unable to find any friends—I mean any relations of the dead man?' said Prince Krotol slowly.

"He had no relatives in England, and they can't find anything to prove that he had relatives in Russia," said the assistant.

He chanced to glance at the bearded face at that moment, and fancied that he saw a quick shade of relief pass across the visitor's face.

"He was a lonely man," the Russian said. "He had no near relatives, so far as I know."

Something seemed to have pleased him. He was leaning back in his chair, and there was a smile that was almost friendly on his hard face.

He changed the subject, and began to chat with Tinker on his life in Russia, proving himself a very mine of information on the subject. The young assistant soon discovered what a fascinating personality was his visitor's. He was surprised to note that it was eight o'clock when the prince arose.

"I am afraid that I cannot wait any longer," he said.

"You will tell Mr. Blake that I called, and will be very pleased to see him at any time. If he writes to me, care of the Embassy, I will be pleased to keep any appointment he may make. I am anxious to clear up zis mystery that ees attached to my friend's death."

He held out a slim hand, and Tinker exchanged grips. The fingers of the Russian were of a curious flabby coldness, something of the touch of dead flesh in them. Despite himself, the young assistant could not repress a shudder which, however, his companion failed to observe.

"Curious beggar that," the lad thought, as he halted in the centre of the room, and stared at the closed door, which had shut behind his well-dressed visitor. "Something fishy about him, and his hand—ugh!"

Tinker went back to the easy-chair, and curled himself up in it again.

"I'm rather inclined to believe that the beggar was pumping me," he said, after a few minutes' quiet thinking. "Not that it matters very much. He could have found out all I told him by reading the papers with the report of the inquest. I wonder how he managed to pick up such good English, considering that he has never been in this country before."

He might have been even more astonished had he been able to follow the movements of the prince after that sinister individual left Baker Street.

Prince Krotol first hired a taxi, which drove him down to a garage in Long Acre. From that establishment he reappeared presently seated at the wheel of a powerful-looking, torpedo-shaped four-seater. He had changed his attire, and was now dressed in the regulation heavy coat and soft cap.

The car hummed down through Whitehall, swung across Westminster Bridge, and went booming along towards Clapham. It thrashed its way past the great wide common, snorted through Balham and Tooting, and presently emerged on the wind-swept spaces of Mitcham Common.

Halfway across that gorse-clad expanse it wheeled abruptly to the right, and drummed down a narrow lane, halting at last in front of a pair of gates which gave access to some well-timbered grounds. The prince sounded a low note on the horn by his side, and a man appeared unlocking the gates.

The car was driven through the gates, and went on up a grass-grown avenue until, turning out of the line of trees, it halted in front of a weather-beaten mansion.

Here another attendant came out and took charge of the car while his master went up the broad steps and through the wide doorway.

An oil-lamp burning in the hall shed a subdued light over the dusty walls. It was evident that the house was only half furnished, and that no attempt at redecorating it had been made.

Prince Krotol turned to a door on the left and strode into the chamber. The oak floor echoed to his tread, and the oil-lamp, placed on a small table close to the wide, empty fireplace, revealed the fact that, save for the table and a couple of chairs, the room was unfurnished.

Seating himself in front of the table, Krotol struck his palms together twice.

"Kalaz!" he called.

A shuffling footfall came to his ears, and presently in the doorway appeared a squat, misshapen form.

A huge bearded head set on shoulders that might have belonged to a prizefighter. Long arms which hung down beyond the knees, a short, stunted body, and warped, twisted legs.

"Well, master?" a guttural voice croaked, as the hideous being came shuffling forward.

"Everything is quite satisfactory," Krotol said, in Russian.

"We have nothing to fear from this Blake. I pumped his assistant, and find that they do not suspect the truth."

The dwarf's hanging lips slipped back, revealing a row of jagged fangs—a wolf's jowl it seemed in the half light thrown by the lamp.

"Master is clever enough to save himself," he said; "master was always clever enough for that."

The prince leaned back in his chair.

"But I have a lot to do yet, Kalaz, before you and I can return to St. Petersburg," he resumed. "That young fool still defies me—still persists in lying to me."

"Hunger will bring her to her senses, master; she begged for a crust from me to-day."

The hideous face glimmered like some baleful beast's, and the long arms were crossed-over the wide, deep chest.

"I told her that she could eat—when my master said the word," Kalaz ended.

Krotol nodded his head.

"You did well, Kalaz," he returned. "I have staked everything on this—I must have that ukase which that fool Torkoff refused to give to me—and I am sure that his daughter Neta knows where it is."

He knitted his dark brows together and drew a savage breath.

"You were impetuous, Kalaz," he went on. "I did not want Torkoff to be killed that night. I could have handled him better. He loved his daughter, and I could have struck at him through her."

The powerful dwarf thrust his heavy head forward.

"I could not help it, master," he said, in a grim whisper. "I was at the safe when that fool came into the room. He recognised me at once, and if I had not used this"—and his fingers touched a sheath at the broad belt he wore above his loose, dark robe—"he would have cried out."

The prince shook his head.

"Better for us if you had simply stunned him for the moment," he went on; "but there is no use of us talking about that. Torkoff is dead, but his daughter remains to us."

Kalaz came up to the side of the table.

"She asked me to tell her about her father," he said, with a meaning smile; "she does not know that he is dead—surely you can make use of that, master?"

"I have decided to do so," said Krotol. "Bring me something to eat, Kalaz, then I will go and see our fair prisoner."

He laughed grimly.

"It was lucky for us that you found the telegram from Gibraltar," he went on; "and we made use of it just in the nick of time."

The hideous dwarf chuckled aloud.

"In the nick of time, master," he agreed.

He went out of the room, and Krotol leaned back in his chair and thought over the events that had occurred.

Prince Alexis Krotol, Governor of Voslagni, had embarked on a mission that would either bring him fortune or disgrace. He had heard that the exile, Ivan Torkoff, had been skilful enough to persuade the government into granting him a concession over a great tract of land in Voslagni, which had proved itself to be oil-bearing, and of untold worth.

The scoundrelly governor had made up his mind that Torkoff would have to give up the ukase, and, to carry out that decision, the prince had come to London to see the exile.

Torkoff had defied him, and after a stormy interview in the little office in St. James's the Governor of Voslagni had retired, vowing vengeance.

Krotol soon found out that Torkoff had a daughter living in St. Petersburg, and it was his agents that had tried to prevent the girl from leaving Vladivostok. When the prince heard that his men had failed, he realised that no time was to be lost if he were to be successful. That was how it came about that Kalaz was sent down to the office in the quiet buildings to try and steal the concession papers. The old Russian had caught the dwarf, and Kalaz had speedily ended the matter in his own fierce way.

But the dwarf's search had been unsuccessful, and the precious ukase was still to be found.

The dwarf, however, had found the cablegram which Neta had sent to her father from the great fortress of the Mediterranean, and instantly Krotol made up his mind to act on it.

He sent a car down to the docks, and for two days waited for the arrival of the tramp vessel. When the broad-shouldered mate of the Ikon saw his sweetheart into the taxi he little dreamed that the hooded car which moved off on the wake of the vehicle belonged to Neta's enemies.

Kalaz was driving the car, and when the taxi was clear of the docks the cunning dwarf drew close to it, and, leaning forward, called to Neta, in the Russian language.

Instantly the girl stopped her own vehicle, and the dwarf hurriedly delivered the message which his scoundrelly master had prepared for him.

It was to the effect that Torkoff was in hiding over something, and he had sent the car down to meet her at the docks.

Knowing the position her father was in, the girl suspected nothing. Her baggage was transferred to the hooded car, and she was driven to the lonely house on the great common. It was only when she found herself confronted by the sinister face of the Governor of Voslagni that the unfortunate girl realised that she had been trapped.

"She does not know that her father is dead," the scoundrel thought, with a grim smile. "I ought to have remembered that. I must make use of it now."

His fists clenched until the veins stood out like whipcords.

"She must know where the papers are," he muttered aloud. "Torkoff told me that he was really working so that his daughter might be left with a fortune. She acted as his agent in St. Petersburg—and she must know what he has done with the papers."

He leaped to his feet and brought his fist down with a crash on the table.

"And, by heavens, I will make her reveal the secret to me," he went on, an ugly light in his slanting eyes, "if I have to torture the truth out of her!"

He looked at that moment the embodiment of all that was fiendish and vile, capable of any atrocity—the real Russian.

Presently Kalaz appeared with a tray full of viands, and his master made a hearty meal. As the dwarf cleared away the empty plates, Krotol arose.

"Give me the key, Kalaz," he said, holding out his hand; "I will go and see our prisoner now."

The dwarf handed him a key, which he removed from his breast, and Krotol, lifting the lamp from the table, stalked out of the chamber.

He went up the broad, uncarpeted stairs, and at the second floor turned down a wide corridor. At the end of the corridor he halted, and, inserting the key in the lock, turned it and entered.

At his coming there was a faint creak from the far corner of the room. The governor held the light above his head and came forward slowly:

Shading her eyes from the light, the slender form of Neta Torkoff stood, swaying slightly, beside the miserable bed she had flung herself upon.

"Have mercy on me!" she cried, her white lips trembling. "I—I am so hungry, and—and the darkness terrifies me! Oh, if you have any pity in your heart, let me go—let me go!"

Neta in Prison.

THE hard, mocking laugh of her captor rang out as he placed the lamp on the dusty mantelpiece.

"I am quite ready to let you go," he said, with cruel emphasis. "I have no desire to keep you here, but I must have an answer to my question."

The pallid face of the girl twitched for a moment.

"And I cannot give you an answer," she returned. "I promised that I would not betray my—my father. Surely you would not ask me to do that?"

"I ask you to do more than that," the steely voice went on. "You say that you will not betray your father. I tell you that it is only by your giving me the secret that your father will be saved!"

Neta drew a short, quavering breath, and sank on to the miserable bed.

She was weak with hunger, and the terrors of the darkness had chilled her young heart. Only a soulless brute could have stood as that man stood-watching her misery.

"My—my father in danger?" she said, in her weak voice. "That is not true. My father is an Englishman now, and he is safe in his own country, thank Heaven!"

Krotol took a pace forward.

"Your father may be an Englishman in England," he said slowly, "but in Russia we still claim him as a servant of the Tsar. You, too, Neta, although you claim to be English, are under the law of the Tsar."

"No, no!" the girl protested indignantly. "My mother was English, and my dear father had taken out his papers years before I was born, I am English—and proud of it!"

The prince's face darkened, and he came slowly forward until he was close to the cot. Then he folded his arms and stared down at the white, thin face of his victim.

"Well," he said, "and if you are English, has that fact saved you? You are here in my power—and I tell you that were you in the wilds of Siberia, your prison could not be safer."

He laughed, a low, mocking chuckle.

"English or Russian, you are my prisoner," he grated, "and I will deal with you as we do our slaves of the mines. And your father—"

"Yes, yes!" Neta broke out, clasping her hands. "What of him?"

The glimmerings of a plan came to the prince, and he voiced it at once.

"Is very anxious about your non-arrival," he said, lying easily; "he cannot understand it. And I am going to make use of that."

He leaned forward, his cruel eyes fixed on her pale face.

"A messenger will call on him at his office, with a proof that he comes from you—that locket which you wore around your neck, and which contains your father's photograph, will do very well," he said. "The message will state that you are waiting for him at Vladivostok. Your father will risk the entry into the country he has so many enemies in—and Siberia will have another inhabitant!"

"You brute—you cruel, heartless wretch!" the girl cried, leaping to her feet. "You would not dare to do such a thing. England can protect its subjects in any part of the world."

Her tormentor smiled again.

"England will never know," he said. "There are hundreds of foolish British wearing their hearts out in the mines; but England will never hear of them."

A quick doubt came to the tortured girl, and she voiced it suddenly.

"My father will not be deceived," she said, little dreaming that her unfortunate father was beyond all human deceits and tricks. "He received a cablegram from me from Gibraltar. He will know that your messenger is lying!"

There were proofs of a shrewd brain behind the quick doubt, but the Russian was ready for that.

"Your father never received that cablegram!" he said, with a sneer. "My spies saw to that. Look!"

He thrust his hand into his pocket, and withdrew a bulky book. The cablegram was withdrawn from a neatly-folded bundle.

"There is your message!" he said grimly.

Neta's eyes swam with sudden tears as she read the words.

She had been so happy when she had written them. The memory of the tanned face of the gallant young sailor arose into her brain, and a great sob broke from her lips.

"Does that satisfy you?" the prince asked.

Perhaps his cunning was too obvious—there might have been a shade too much of anxiety in his tones, but from whatever cause, Neta suddenly felt a thrill of suspicion run through her.

"I am satisfied that you are a scoundrel," she blazed, with sudden fury, "and I will not tell you anything! I defy you, beast that you are. You may kill me if you like, but I will not speak!"

Her voice had suddenly grown strong and clear, and the last words rang out in the chamber like the high, sweet notes of a silver bell.

A devilish hate leaped suddenly into the eyes of the Russian, and he leaped at her and caught her by the throat.

"Curse you!" he hissed, all his ungovernable rage seething through him. "You defy me?"

Sick and dazed at the numbing pressure of the cold fingers, Neta felt her weakened frame give way suddenly. She dropped in a heap on the narrow cot, and with an oath the prince released his grip.

"For a moment he stood above her, staring down at her limp frame, his breath coming and going in thick, angry gasps. Then, afraid to trust himself further—afraid that his rage might urge him to kill this defenceless woman, even though her death meant the concealing of the hiding-place of the papers for ever—Krotol leaped away from the cot and crossed to the mantelpiece.

"Listen to me!" he harshed. "I will give you until tomorrow night to think over matters. If you do not reply to my question by then, the messenger will go to your father, and Siberia will close on him just as surely as the door of this chamber closes on you. I swear that you will be allowed to go free if you will only reveal the secret, and if you are wise you will do as I ask."

Among those who knew him, Krotol went by the name of "The Wolf," and as he crossed the chamber at that moment there was much of that treacherous animal's manner about his tread and poise of body.

At the door he halted for a moment, and flung a glance back at the dark corner. The girl was lying on her side, her face buried in her hands. The coils of her rich hair trailed over the dirty blankets, and lay in gleaming ripples on the unswept boards.

No stir of pity came to the wretch's heart as he looked. Misery of that human type could not touch the soul of the Governor of Voslagni, who had sent so many poor wretches to their doom in his hunger for wealth.

"Until tomorrow!" he said, in a low, threatening voice.

The door boomed behind him, and Neta heard the key rasp in the lock. A torrent of tears came to her then, and she sobbed her heart out in the dark loneliness.

She was weak and faint from hunger, the darkness of the room seemed to thrust cold, numbing fingers into her brain.

"Heaven help me! Heaven help me!" she breathed over and over again.

Half an hour later there came faintly to her ears the drumming of a motor-car. She staggered to her feet, and crossed the room towards the small window. It was guarded by heavy iron bars, but she could see the dark outlines of the grounds far below. The white headlight of a car shone out, and she followed it as it crawled like a wraith down the long avenue between the trees.

"He has gone!" she thought, clasping her hands over her breast. "Thank Heaven for that! The hideous dwarf is vile enough, but he is not so vile as his master!"

She turned away from the window, and rested against it for a moment.

"Jack, Jack!" she cried aloud, stretching her hands out in sudden longing. "Oh, if you only knew what I am suffering, you would come to me! Oh, Heaven, if you only knew!"

The rasp of the key brought her suddenly back from her dreams.

The ugly face of Kalaz appeared in the doorway. In his long arms was a tray, covered with a white napkin.

A strangled cry broke from the girl's lips, and she swayed forward.

"Master said that you could eat," the guttural voice proclaimed, "and Kalaz always obeys the word of his master."

He came into the room, and placed the tray on the cot.

Neta touched him on his shoulder.

"And—and may I have a light?" she said, with a little pathetic note of pleading in her young voice. "It is so dark here, I—I always feared the dark."

Kalaz moved abruptly to one side so that Neta's hand fell away from his shoulder.

"Master said nothing about a light," came the grating tones. "You must be content."

He shuffled across the room, and went through the doorway, locking the heavy barrier behind him. Neta seated herself on the cot, and felt for the tray with hands that trembled.

A jug of water came beneath her groping fingers, and she took a long, delicious draught of the cold fluid.

Then, in the darkness, she began to eat ravenously, as a caged creature might have done.

When she had removed every fragment of food from the tray, Neta Torkoff felt a different woman. She leaned back against the hard pillow of the cot, and in her pale face a grim, determined light glowed.

"My father told me to guard the secret as the most sacred thing," she thought, "and I will do it. That man is a rogue and a bully, and I feel that he is lying to me. I will not speak!"

Her English mother had given the young girl her unconquerable spirit. Alone, and at the mercy of her enemies, Neta Torkoff was still able to face them with fearless spirit.

"I wish Jack knew," she thought, her small hands clasping together. "He is so big and strong and brave. He would make these cowards realise that I am not quite friendless."

She little dreamed that at that very moment another man—a more capable, cleverer man than her lover, was stirring himself on her behalf.

For as Prince Krotol was hurried westward in his car, Sexton Blake was also moving for the same rendezvous—the rooms of the Warsaw Club.

A Grim Struggle.

"I DON'T say that you will be in any danger, Mr. Blake," the Foreign Office official said; "but it is always best to go prepared for—er—any contingencies."

The great detective smiled.

"I will attend to that, Sir Rupert," he returned, as he arose to his feet; "and I must thank you for the trouble you have taken."

"Don't mention it," his host returned. "Glad to be of any assistance to you. And now, when would you like my man to meet you?"

Blake glanced at his watch.

"I am going back to Baker Street," he said, "and I will be ready within an hour."

"Very well. De Valoux will meet you on the steps of the club at, say, nine o'clock."

"That will do excellently," Blake said.

He walked out of the big office in Whitehall, and turned towards Baker Street. He had gone straight to the Foreign Office from the General Post Office, and had quickly arranged about his visit to the Warsaw. Sir Rupert Hetherington, one of the under-secretaries, had been only too pleased to arrange that the famous detective should be taken into the club by a member.

De Valoux, the member in question, was one of the secret service agents attached to the Foreign Office, and a word on the 'phone with him had speedily arranged about the visit.

As the detective entered his chamber he found Tinker waiting for him. The young assistant hurriedly recounted the interview he had had with Prince Krotol, and Blake took a mental note of the name.

"What sort of man was he, Tinker?" he asked.

The shrewd, young assistant gave a graphic description of the Governor of Voslagni.

"Good!" said his master. "I don't think I could mistake him now.'

"What do you think about it, guv'nor?" the lad asked.

They were chatting together in Blake's bed-room, where the detective was engaged in dressing himself for the part he was about to play.

"I can't say that I like it altogether, Tinker," Blake admitted. "If this prince was such a friend of Torkoff's, why didn't he appear at the inquest and give evidence that would serve to identify the man?"

"I never thought of that," said Tinker. "Besides, he said that Torkoff had not got a relative in the world."

Blake smiled.

"Lie number two," he said. "I have had proofs given to me that Torkoff has a daughter alive, and, as far as I know, she is in England at this very moment."

Tinker's eyes widened.

"You didn't tell me that, guv'nor," he said, in a rather injured tone.

"I hadn't got time to tell you, old chap," his master returned; "and I don't think I have time to do so now. But I can do something else for you."

"What is that?"

Blake took out his pocket-book and produced a scrap of paper.

"There is the address of a person who can give you all the details," he said, handing Tinker Brearley's address. "If you like to run down there to-night, you could have a chat with the man. And, at the same time, you might find out if he had ever heard of this Prince Krotol."

"Right you are, guv'nor," said the young assistant, pocketing the slip. "I'll do that."

Blake was poised above his make-up box; and when he turned his head, Tinker smiled at the extraordinary difference that was revealed in the features. Blake had fixed a straggly beard to his chin, and had stained his cheeks until they were a deep tan. The loose-fitting suit, with the padded shoulders, and the peg-top trousers, completed his disguise.

He looked like a wanderer from the States—a typical example of the Yankee visitor who flocks to our shores.

"Where are you going, guv'nor?" the lad asked.

"Warsaw Club," said Blake. "I find that Torkoff must have been a member there. I may be able to find out something more about him."

Tinker's shrewd face was a trifle grave.

"These foreign clubs are usually unholy sort of places to get into," he said; "and a thundering sight worse to get out of. Sure you won't need me, guv'nor?"

"Not this time, old chap," Blake returned quietly. "I'm going to lie very low. It is only a watching game that I am on this time. Later, perhaps, we may have to step out into the open."

He left his chambers, and a taxi carried him to the quiet street in which the Warsaw Club was situated. As he alighted from the cab, a dapper little gentleman, in correct evening attire, came down the steps of the club, and held out his hand.

"How do you do?" he said, in a high voice. "I thought that you would never come."

It was De Valoux, the Foreign Office spy, and Blake quickly fell into the man's manner. He made some drawling reply, and they both sauntered through the open doorway and into the club.

Blake found himself presently in a big smoke-room in which a few men were seated in little groups. De Valoux found a small table in one of the windows, and, having called for drinks, he and the detective began to chat together.

"I shall have to be careful," De Valoux began. "One or two of the members rather suspect me, and I can't afford to take any risks, Mr. Blake. If you have any arresting to do—well, I'd rather be out of the way when it happens, if you don't mind."

Blake smiled. He quite appreciated the little spy's attitude.

If it ever leaked out that De Valoux was a spy the doors of the club would undoubtedly be closed to him at once.

"I don't think I'll play a very active part," he returned; "but, still, you can leave me just whenever you like. I only want to find out about Torkoff. You read about that case, of course?"

The spy nodded.

"So it's the Torkoff affair you are on," he said slowly. "Sir Rupert did not mention that to me. What has the Warsaw Club to do with that?"

"I believe that Torkoff was a member," said Blake.

De Valoux shook his head.

"I've the list of names at my finger-tips," he said, "and Torkoff is not among them. That I will swear."

"He might have joined under another name, though," Blake hinted.

"Very likely," said the spy. "In fact, it is more than likely that he did. Very few of the members care to register under the names that their fathers gave them." And his little, bright eyes lighted up with grim mirth.

"And there's another man I'm rather interested in," Blake went on; "Prince Krotol. He's a member, I suppose?"

It was only a chance shot, but it hit the mark. De Valoux removed his cigarette from between his lips and stared hard at Blake.

"What do you want with the 'Wolf?'" he asked, in a very different tone.

"Is Krotol the 'Wolf'?" Blake asked.

De Valoux nodded.

"That is the name we give him," he said, in a low voice; "and he has earned it, too."

"Who is he?"

The little spy leaned forward.

"One of the most unscrupulous blackguards that ever lived," he said. "He is the governor of a big province in Russia, and if half the tales that are told about him are true he deserves to be hung, drawn, and quartered."

"Humph! That's pretty interesting," the great detective returned. "'You would not believe that Krotol was capable of taking a friendly interest in a fellow-countryman, then?"

"He never took an interest in anyone, except his very precious self," the spy assured Blake. "He has hosts of enemies, but no friends."

Blake was silent. He felt that he had heard as much from De Valoux as was necessary, and he did not want to bring the little spy into his business. De Valoux's time was at the disposal of the Foreign Office, and Blake was already in the little man's debt for what he had done.

"Does Krotol come here often?" he asked.

The spy jerked his thumb at a closed door covered with green baize.

"They are inveterate gamblers, these Russians," he said. "You'll probably see the prince come in here about midnight, and he'll go straight into that room."

Blake rose to his feet.

"Then if you'll just take me in there," he said grimly, "I won't trouble you any longer. Just fix me up, and leave me."

"You are sure that you won't mind?" the spy asked.

"I would prefer it," said Blake.

De Valoux led the way across the smoke-room into the deep room beyond, Although it was early in the evening, there was already a fair gathering of gamblers in the smoke-laden room. Blake marked the presence of a roulette table, and sauntered across to it, followed by the little spy.

They watched the game for a moment; then Blake, as if suddenly tempted by the little ball, staked a coin. He lost, and staked another. The group made way for him, then, and De Valoux, with an expression of relief on his face, sauntered away from the fascinating board. He knew that Blake had deliberately taken part in the game so that his presence there might be taken as a proof that he was of the same gambling habits as the others.

"If it was any other man I might be afraid to leave him," the Foreign Office man thought; "'but I can safely leave Sexton Blake to look after himself."

An hour passed, and then another, and still Blake hung around the roulette. He had chosen that spot as it was exactly opposite the green-baized door, and his eyes went towards the doorway every time it opened.

At last the man he was waiting for appeared. The saturnine features of the tall Russian prince came through the doorway, and, thanks to Tinker's keen description, Blake recognised Krotol at once. The detective studied the face quietly, and the slant eyes and cruel, hawk-like nose told him that here was a man who would stop at little so long as he gained his own ends.

Krotol came slowly into the room with an undisguised swagger. He was a big man in the Warsaw Club, and made no attempt at concealing that fact.

His slant eyes shot round in a circle, examining the various groups, and presently they turned on the roulette table.

Blake deliberately drew from his pocket a large bundle of banknotes and placed one of them on the red.

He did not glance at Krotol, but he knew that the Russian was watching him—watching him with the hungry eye of the gambler. The ball clinked slowly, and fell with a little thud in its place. Red won, and Blake raked in the little heap of coins which the croupier counted out.

Suddenly Blake felt a touch on his elbow, and found one of the servants of the club by his side.

"Prince Krotol's compliments, sir," the man said, "and would you care to join him in a game? He is just making up a party."

It was exactly the invitation that Blake had been waiting for, and he followed the servant at once.

The Governor of Voslagni was seated at a small table in one corner of the room, and there were two other pallid-faced men seated with him.

There was little of the introduction ceremony attempted.

The men knew that they were there simply to pass the night in the evil habit that swayed them. Blake evidently had money, and that was quite enough for them.

For two hours the men played, and at the end of that time Krotol found that the calm stranger was not to be easily disturbed. Sexton Blake had won something like a hundred pounds, and the Russian governor was almost beside himself with annoyance.

"Let us go to my flat," he said, rising to his feet, and talking in a thick voice. "This cursed place annoys me! There are too many people about."

One of the men at the table refused his invitation, but Blake and the fourth man accepted.

They left the club, and Krotol chartered a taxi, which speedily carried them to his flat. A grim smile flickered on the great detective's face when he noted that the flat was situated in St. James's Square—within a stone's throw from the building in which Torkoff had met his fate.

The Governor of Voslagni entered his rooms and switched on the electric light. It was a handsome apartment that Blake found himself in, lavishly furnished and decorated. A manservant came forward, and at a word from his master prepared the table for cards.

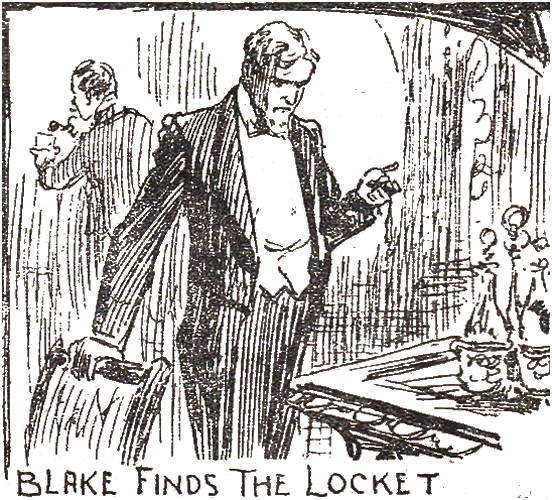

On one side of the room stood an immense sideboard laden with decanters and glasses. Blake sauntered across to it, and suddenly, on a small silver tray, he noted a little object.

A gold locket attached to a thin gold chain. On the locket, in tiny diamonds, were the initials "N.T."

A mirror in the sideboard gave the detective a chance of watching the movements of Krotol.

The prince was busily engaged in removing the wrappings from a pack of cards.

Quickly Blake lifted the locket and touched the spring.

The halves flew open, and he saw two miniatures—one of a fair, beautiful girl, the other of a man. And the face of the man was that which he had seen at the Yard as being the features of Ivan Torkoff.

Instantly into the detective's brain the truth leaped.

Prince Krotol knew where Neta Torkoff was!

For a moment the discovery took him by surprise, and he forgot his usual caution. He was staring at the locket when he suddenly heard a footfall by his side. Glancing up, he encountered the slant eyes of the Governor of Voslagni fixed menacingly on his face.

"Pretty woman, that," said Blake, with his assumed drawl, as he dropped the locket again, and turned away. "Guess she's not English, though."

The Governor of Voslagni hurriedly lifted the locket, and thrust it into his pocket.

"She is a—a niece of mine," he said, in a gruff voice, as he turned away.

The third man of the party had already taken his place at the card-table, and was idly shuffling the cards. Blake drew a chair forward, and was about to take his seat, when suddenly on the outer door of the flat a loud knocking began.

Krotol started, and an oath broke from his lips.

Crossing to the door of the room he opened it, and called to his servant, speaking in the harsh, guttural tongue of his race.

Blake heard the man walk down the corridor, and the bolts on the outer door of the flat were shot back.

Crash!

The door was flung heavily aside, and the sound of a quick scuffle came to the ears of the listeners.

Blake leaped to his feet, an action which the other man at the table followed.

"Out of the way, you skunk!" came a deep, booming voice—a voice which the great detective recognised at once. "I want a word with your master, and, by thunder, I mean to have it!"

A second later the door of the room was flung aside, and the giant form of Jack Brearley appeared.

The sailor's strong face was as grim as a vice, and the blue eyes were flaming with some fierce passion.

Krotol had backed away from the door as the sailor entered, but, recovering his nerve, he came forward slowly.

"What is the meaning of this?" he asked, in his cold, flexible voice. "How dare you thrust yourself into my rooms in this manner? Who are you?"

The sailor placed his brawny hands on his hips and eyed the evil face of the prince.

"I'll tell you who I am when I know who you are," he said slowly. "I am looking for Prince Krotol."

"That is my name," said the Russian.

"Ah!" Brearley took a pace forward, and his clenched fists slid in front of his body. "Well, my name is Brearley, and I want to know what you have done with Miss Torkoff."

Blake came forward slowly, his eyes fixed on the tense figure of the giant Russian. The sailor, in his impetuous way, had thrust himself into a situation which might have disastrous results.

Krotol, however, was a master of cunning. He did not allow a sign to escape him.

"I do not understand you, my man," he said, with a slight shrug of his shoulders. "You must be mad—or drunk. If you do not leave my flat at once I will have to send for the police. Your English law does not allow madmen like you to thrust themselves into gentlemen's private apartments and create disturbances."

Jack Brearley drew a deep breath.

"You can't fool me, you skunk!" he broke out, his blue eyes flashing dangerously. "I've just left a man you know well enough—Darovitch is his name. The last time I saw him was in Vladivostok, and he was flat on his back from a punch with this"—and he held up a huge fist.

The slant eyes of Krotol gleamed with a sudden fury. He knew that Darovitch—one of the two spies who had tried to prevent Neta from leaving Russia—was now in London.

It was evident that Darovitch had betrayed him to this fierce sailor.

"You speak in riddles, my man," the Russian returned. "If you have any grievance against me call and see me tomorrow. It is now past midnight—not the usual hour for calling in this country."

"I don't leave here until I get the truth out of you!" Brearley roared. "That spy of yours told me that you were at the bottom of this business, and, by heavens, I mean to make you speak!"

He seemed oblivious of the fact that there were other men in the room. The white fury he was in made the prince take a pace backwards.

"You are mad—" he began.

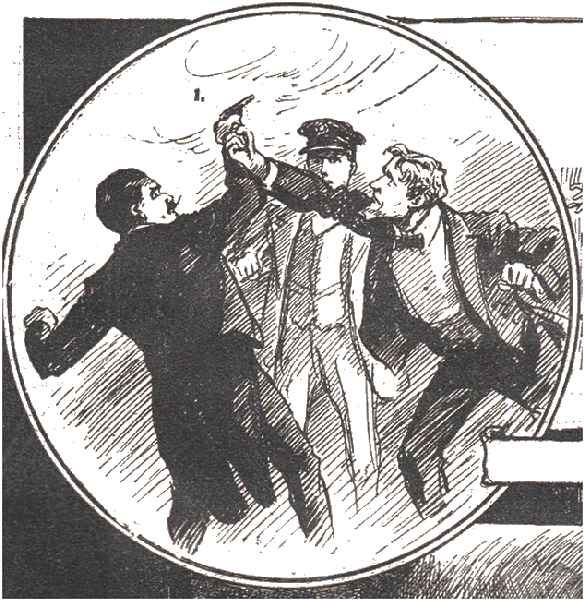

With a muffled shout of rage Brearley threw himself forward. Blake saw Krotol's brown hand slip like a snake into his pocket. Quick as a flash the detective leaped across the room, and as the revolver flashed in the man's hand, he struck hard at the tough wrist.

Crack!

The report of the weapon rang out, followed by a sharp tinkle of glass, and the room was plunged into darkness.

A guttural oath sounded, and Blake felt Krotol lunge forward, madly striking at the face of the sailor. A shout came from the corridor and the doorway was blocked suddenly by a couple of forms.

The servants of the prince were coming to the aid of their evil master.

Instantly Blake knew that they were in a tight corner, and although Brearley had practically brought his fate on himself, Blake could not let him face the odds single-handed.

A couple of powerful figures came reeling against him, and he knew that the prince and the sailor were at each other's throats. Blake stooped, and thrusting his shoulder forward, wedged it against the back of one of the antagonists. A mighty lunge saw the two wrestlers forced across the room and into the doorway, where they thudded against the forms of the servants.

A torrent of guttural words broke out, and Blake saw the men in the doorway leap back. There was a light in the passage, and as Krotol and Brearley reeled out into the narrow corridor, Blake followed them.

The Russian was clinging to his great antagonist like a panther, and try though he did, the sailor could not loosen the grip on his arms.

To and fro they reeled and at last Jack's feet were jerked away from beneath him and he went crashing on the thick carpet beneath. That seemed to be a signal to the servants, for one of them, with a shout of satisfaction, flung himself forward. Blake saw a thick club appear in the man's hand as he swung it above his head.

Krotol was kneeling on the writhing form of his opponent and he turned his slant eyes towards his servant.

"Quick!" he cried.

The cudgel poised for a moment, and the powerful hands tightened their grip. But before it could descend on Brearley's head—

Crack!

From the doorway of the inner chamber a little spiteful blue flame leaped, and with a yell of pain the brawny servant dropped his weapon and reeled back with his shattered hand dangling uselessly from his wrist.

Crack!

Another shot sent the electric bulb into a thousand splinters, then Blake, with the smoking revolver still in his hand, darted down the corridor. The second servant aimed a blow at him as he came, but the detective's wiry fist shot out and the man went down like a felled ox. Krotol, startled at this sudden attack, found a steel-like arm slipped suddenly around his bull-throat, and with a jerk he was flung bodily clear from the body of his opponent.

He went thudding against the wall of the passage, and collapsed with a gasping moan.

"Now, old man," Blake's cool voice whispered into the ear of the sailor. "Up and follow me—as sharp as you like."

He caught at Brearley's arm and lifted him to his feet, then sped on towards the outer door, with the dazed sailor lumbering at his heels.

When they emerged into the quiet square they caught sight of a uniformed figure hurrying towards them from the other end of the pavement. Linking his arm into that of Brearley's, Blake set off at a swinging trot. The policeman called to them, but the detective only quickened his pace, and a few minutes later the two men found themselves in the Mall.

"I—I recognised your voice, Mr. Blake," Brearley gasped. "What—what does it mean?"

The great detective smiled grimly.

"It means that we were both on the same errand—but your way was the least artistic," he said. "I have spent the last two hours with Krotol—and I think he is the man I have been looking for."

The sailor's grim jaw set with a snap.

"I'm sure of that," he said. "I had proofs of it this evening. By jiminy, I feel half inclined to go back now and tear the truth out of him."

"A very foolish inclination," said Blake slowly. "He is a sly, dangerous rogue. And I am sorry that you told him as much as you did. He will be doubly on his guard now."

"He knows where my beloved Neta is," said Jack, passionately. "I know that much. It was only a piece of blind luck that sent me down to the docks this afternoon; when I saw the face of that spy, I could have killed him."

"What happened?" asked Blake.

The mate of the Ikon hurriedly gave a brief account of the strange circumstances that had led to his seeking out Krotol at his flat. It appeared that the spy, Darovitch—whom Brearley recognised at once as being one of the two rascals who had pursued Neta—had been loafing about the quay where the Ikon was being unloaded. The mate had waited his chance and had tackled the ruffian.

"I had him on his back, hanging over the dock," said Brearley, with a fierce breath; "and, by George, I'd have drowned the beggar like a rat if he hadn't told me the truth."

"What did he say?"

"He said that it was Prince Krotol who had sent him down to spy on the Ikon," said Brearley. "I tried to set out of him the whereabouts of Neta, but I'm convinced now that the beggar did not know. All he could tell me was that Krotol was at the bottom of it all—and he gave me his address. I was standing in the square when you drove up in the taxi—but I didn't recognize you, Mr. Blake, or I might have waited."

Blake was silent for a moment.

Brearley's action had probably set Krotol on his guard, and it would be a difficult matter to catch the wily Russian napping again.

"Did Miss Torkoff have a small gold locket?" he asked, presently; "a locket on a thin gold chain, with initials in diamonds on it?"

Brearley caught him by the arm.

"Where did you see it?" he asked eagerly. "She always wore that locket. She treasured it above everything else in the world."

"Krotol has it in his possession at this very moment," said Blake slowly; "and that means that he knows where Miss Torkoff is."

The sailor came to a halt.

"Then, by Heavens, I'm going back," he proclaimed fiercely. "I'll drag the truth from him, or die!"

Blake caught at his muscular arm.

"If you want to see your sweetheart in the flesh again," he said slowly; "you will do no such thing. You must remember that Krotol has played his cards very well. Not a breath of suspicion has been heard against him. He will have taken care to cover his tracks well—you can trust to a Russian for that."

"But you will not leave my sweetheart in his hands," the mate went on; "the man is an utter fiend! There is nothing too vile for him to attempt. My Heaven, Blake, I—I cannot bear the thought of it—it drives me mad!"

Blake's face was stern and grim.