RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

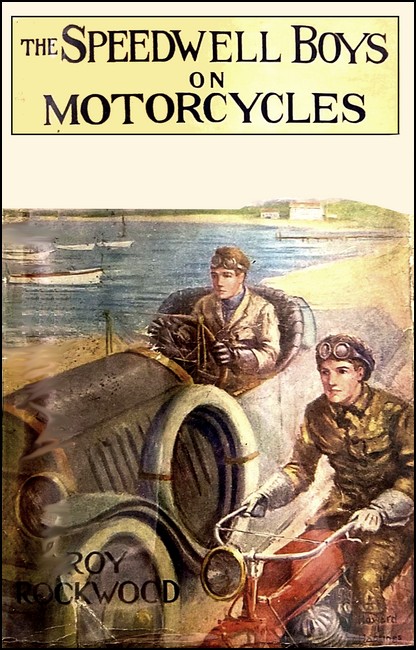

Dust Jacket of "The Speedwell Boys on

Motorcycles,"

Cupples and Leon, New York, 1913

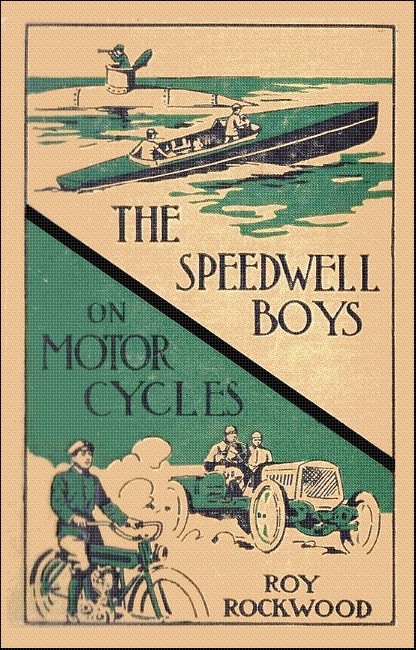

Cover of "The Speedwell Boys on

Motorcycles,"

Cupples and Leon, New York, 1913

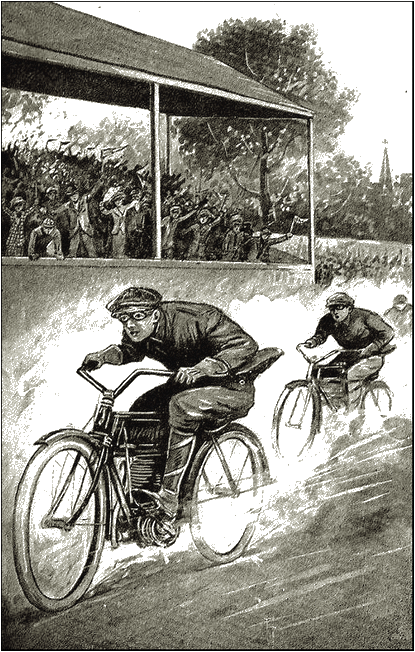

Frontispiece.

Chance Avery had to content himself to tag in, a bad second.

"WHICH road did they take, Dan?"

"Why, the pike, I suppose."

"We'll never catch up to them," complained the younger lad, impatiently, pedaling furiously over the country road between Riverdale and Upton Falls.

"'Never' is a long lane, Billy," laughed his brother.

"If we had motorcycles like Chanceford Avery, we'd get to the Falls all right," puffed Billy.

"That is what put them all so far ahead of us," responded his brother. "Chance is pacing them on his motor. Some of the girls and the youngsters will be dead tired by the time they arrive."

"We'll catch up to them, then," said Billy Speedwell, grimly, "on the home trip. I believe Chance Avery insisted on starting from the Court House so early just so we'd be behind."

"I reckon half-past six suited most of the town members, and those who live out this way," replied Dan. "But it certainly has made us hustle to get through the chores, and then to change our clothes and come from our house on the other side of the town."

"He knew he'd bother us," repeated Billy.

"Pshaw! Perhaps he never thought of us at all," rejoined Dan.

"I'll wager he did. Come on, Dan! there's the forks of the road just ahead."

The Riverdale Outing Club had settled on this beautiful evening for a moonlight run to Upton Falls. The club members all owned bicycles, some of them motorcycles, and these evening outings were popular. It was something like two hours' hard pedaling to Upton Falls, where there was a hotel, and the moon would rise before it was time to return to Riverdale.

But the moon did not help these two belated members of the club to see the tracks of the party ahead, when they arrived at the forks. One road—the pike—went across the hills to Upton Falls; the other followed the windings of the river. The latter was by far the pleasanter way; but Dan and Billy Speedwell wished to overtake their friends, if possible, before the end of the run.

"Now we're up a tree!" declared the younger boy, bringing his vehicle to an abrupt stop, and leaping off. "Didn't you hear which road they were to take, Dan?"

His brother swung himself off his own wheel without replying, and lifted off the lamp. He flashed the spotlight ray over the much-traveled road and in a moment said:

"Why, their tracks are plain enough, Billy. They took the pike—see the marks of the tires?"

Suddenly the younger boy clutched his brother by the sleeve, reaching for Dan's lamp with his other hand.

"Sh!" Billy whispered. "Who's that?"

Dan, in surprise, turned in the direction his brother swung the lamp's ray. A man's shadow passed swiftly across the road just beyond the forks, disappearing instantly into the brush which bordered the pike on the left.

On the right was the high stockade-fence of the Darringford Machine Shops. The plant occupied a piece of ground with an eighth of a mile frontage on the pike, while on the left of the highway was a waste of hillock and valley, covered for the most part with scrubby trees and brush, the hedgerow at the very roadside masking a deep gully. The figure which disappeared so quickly had crossed from the machine shop fence and plunged down this steep embankment.

"What do you know about that??" demanded Billy, eagerly. "Did you see him?"

"Why, I saw somebody; or, I thought I did," admitted Dan, slowly.

"Pshaw! Don't say you did not see that man with the rat- trap."

"With the what?" cried his brother, in amazement.

"Just as plain as though 'twas daylight! A rat-trap under his arm—one of those cage traps, you know," said Billy. "He was snooping along there by the fence when I first saw him. But he must have heard us speaking, or seen the light, so he started to cross the road."

"Funny place to set a rat-trap," observed Dan, preparing to mount his bicycle again, having returned the lamp to the fixture on which it hung.

"That wasn't the funniest thing about the man," said Billy, slowly following his brother's example. When they were both pedaling along the road again Billy repeated it: "That wasn't the funniest thing about him."

"What was so wrong with him?" inquired Dan, curiously.

"When I shot the lamp at him there was something hanging before his face. I saw it before he could turn his back to us," said Billy, cautiously. "I suppose you'll laugh, but it looked like a mask to me—a mask with a skirt to it that hid his entire face and fell down to his vest."

"You're seeing things, boy!" cried Dan, laughing. "A man in a mask, and with a rat-trap under his arm! Can you beat it?"

"I said you'd laugh," grumbled Billy. "But you know there's been trouble at the machine shops. Some of those discharged foreigners recently stoned Mr. Frank Avery in the street."

"Oh, but that was some time ago," returned Dan, easily. "They've all left town, and the trouble has quieted down. There isn't going to be any strike. The old hands are too well satisfied with the Darringfords, even if they are a bit sore on Avery."

"Those Averys are trouble-breeders," observed Billy. "Frank got the shops in trouble just as soon as he was made superintendent; and Chance Avery is doing his best to spoil our club. If they can't boss everything and everybody, they're not satisfied. As long as all the members couldn't afford motorcycles, none of them should be allowed on these runs, Dan."

His brother laughed again.

"So that's where the shoe pinches, eh?" chuckled Dan. "But how about if Billy Speedwell owned a motorcycle?"

"A—well—now—" began the younger lad, and just then, having already traveled at a swift pace for several miles, they heard voices and saw the flash of a lamp or two ahead. "Here's the rear guard, Dannie!"

They buckled down to it and swiftly overtook the laggards. Of course, there were only bicycles in the rear of the procession, and the club was strung out along the pike for more than a mile, instead of wheeling in a compact and more social body. The motor machines and the tandems were up ahead, and the fun of the outing was a good deal spoiled by the hard work which the members had to put in. The Speedwell boys were not the only ones of the Riverdale Outing Club who grumbled at the pace set by the president of the association.

"Chance never would have owned a motorcycle if his brother wasn't boss of the shops," said "Biff" Hardy, who worked in the Darringford plant himself and rode a rattletrap of a machine that he had bought for a trifle, and rebuilt in his spare hours. "He had the pick of those made in the shops last year. But we've got improvements on pattern now; this year's output are dandies!"

Billy Speedwell sighed. "I do wish I owned one," he said.

Dan had already run ahead and joined a group of the feminine members of the club. There was a certain black haired girl, whose blue eyes expressed her pleasure at Dan Speedwell's appearance, more than did her simple greeting.

"We were afraid you and Billy would not get here, Dan," Mildred Kent said. "You have to get up so early in the morning."

"We came pretty near missing it, as it was," replied Dan, cheerfully. "You see, we have to go after the milk, and ice the cans before we can leave in the evening."

"It was just horrid early for the run, anyway!" cried the girl who rode beside Mildred—a vivacious, eager, younger girl with bronze hair—the boys called it "red" when they wanted to tease Lettie Parker. "I came away without any supper and I'm as hungry as a bear!" she added.

"You frighten me," declared Mildred, smiling. "If you are as savage as all that, you may eat somebody before you get half way to the Falls."

"I could just bite Chance Avery," said Lettie, promptly. "If it hadn't been for him I wouldn't have gone without my supper. There was no need of starting so early—especially for those who own motors."

"If you're going to bite anybody, would you mind biting me?" asked Billy half seriously. "It'll take my mind off our troubles," and he proffered his cheek invitingly.

"Oh, I guess I'll wait until I'm hungrier," spoke Lettie, with a laugh in which the others joined.

"I wish we all owned motorcycles," declared Mildred. "I have tried Cousin Ed's. It's splendid to be able to go so fast—and with so little exertion. I hear the club is going clear to Barnegat on Saturday afternoon.—I know mother will not let me 'bike' so far. She says we all overexert ourselves on these long runs."

"I'm going!" said Lettie, with confidence. "I'm going to hire a machine. I've tried a motorcycle, and they're just splendid, I think."

Some of the other girls who were near enough to overhear this conversation, joined in it. They were all determined to buy, borrow, or hire motorcycles for the Barnegat run. And, of course, Dan Speedwell knew that several of the boys would do the same. Many of the club members were well able to afford the luxury; but Dan and Billy were poor.

The Speedwells had a small farm on the outskirts of Riverdale, and ran a dairy. Dan and Billy delivered the milk to customers in the town every morning, and they had to rise by two o'clock, milk the cows, cool the milk, and so were on the road with two small wagons by half-past four. Mr. Speedwell was a hard-working man, but not strong; the boys' mother was a cheerful, sensible woman. There were two children beside Dan and Billy—Carrie, ten years old, and Baby 'Dolph, who was just toddling around and beginning to talk.

At the Falls, while they were partaking of the simple refreshments that had been prepared, and afterward, the principal topic of conversation was the run planned for the following Saturday afternoon. Barnegat was thirty miles or more from Riverdale, and there were hills to climb. Many of the younger members, and the girls, would be unable to go unless they had power machines. One or two parties would go in automobiles; but most of the members objected to that. The Riverdale Outing Club was primarily a cycling association.

It was the consensus of opinion, however, that only those members who could obtain the use of motorcycles would be able to make the run to Barnegat, and a "consolation run" was talked of for the others, to some nearer point.

"But that isn't of any use," said Billy Speedwell to Dan, as the club prepared for the homeward run. "We are bound to split up. There will soon be two clubs in Riverdale, and the town isn't big enough to properly support two. How will we ever get a club house if we keep on this way? I tell you, Chance Avery is doing us a lot of harm. He should never have been made captain."

The moon flooded the road with ample light when they started for Riverdale, and the return run promised to be very enjoyable, despite the friction in the club. The road was good, not too dusty, and the Speedwells trundled along very pleasantly in the moonlight. When they reached the long stretch of fence belonging to the Darringford shops they slowed down.

"Where do you suppose your masked man with the rat-trap is?" asked Dan.

As he spoke both boys caught sight of a moving figure in the shadow of the fence. It darted across the road and plunged into the fringe of bushes. By mutual consent the boys stopped and sprang off their wheels.

"There's something doing here, Dan, as sure as you live!" exclaimed Billy. "Let's look into it."

Before his brother could object, the younger boy ran across the road and followed the mysterious stranger through the hedge. Dan only waited to snatch his lamp from its fixture, and then ran after the impetuous Billy.

There was a narrow path at this point winding down the steep side of the gully. Billy was already running down this when Dan came with his lamp to the brink of the descent.

He was out of sight in an instant, but Dan heard him shout:

"Come on! Here he is, Dan!"

The older Speedwell lad followed, fearing that Billy would run into some peril. And before he reached the bottom of the hill he heard the younger boy scream. Then followed a crashing noise, and Dan reached the end of the gully with a rush. He found the bottom mostly clear of bushes, but neither the moon nor the ray of his lantern revealed his brother or the mysterious stranger.

FOR half a minute Dan Speedwell stood motionless, straining his ears to catch a sound from his brother. Lack of caution was always Billy's fault; and he had heedlessly followed the man who had been lurking about the Darringford premises.

"What's happened to the boy?" whispered the older brother. "Has that fellow harmed him?"

He flashed the ray of the bicycle lamp about the cleared space. For the moment he was confused and amazed. Then he heard, and it seemed rising from under the earth at his very feet, a hollow voice which uttered this warning:

"Look out how you step, Dan! Look out!"

"Billy!" gasped the older brother. "For pity's sake, what's happened?"

"I fell in—look out! You'll have the whole place caved in on me, Dan."

The latter saw the break in the clump of low bushes, then almost within reach of his hand. Another incautious step and he might have followed the caving brink of the pit to the bottom.

He forgot all about the stranger they had been following; the mystery of that individual was quite unimportant now.

Dan Speedwell was level-headed. He had been frightened; but he had his wits about him again in a moment. The lamp in his hand gave illumination sufficient for him to see what he was about. He dropped on his knees and crept to the broken place in the clump of bushes.

These had masked the mouth of the pit, well, or whatever it was Billy had tumbled into. The older boy saw the jagged ends of rotting timbers and boards. There had been a wooden top over the hole, and Billy's weight, when he plunged through after the strange man, had burst this cover. A sudden thought came to Dan, and he cried:

"Are you alone down there, Billy?"

"Great Peter! I should think I was," exclaimed the younger boy. "I wish that chap I was chasing had fallen in first—then I'd have had something to land on beside rocks and dirt The sides of this old well are cemented, and some of the stones have fallen down. It's lucky I didn't break my neck."

Dan left the bicycle lamp on the ground by the open well, and hurried back to the street There were houses not far away, but he shrank from waking sleeping citizens at this hour. Besides, if he could get a rope he would need no help at all.

There lay his wheel beside the road; he could easily run into town and obtain a rope at a livery stable, or some such place, where he knew somebody would be awake. He leaped upon the machine and started toward Riverdale at racing speed. But all the time his mind kept pace with his legs in action. What explanation should he make of the cause which led to Billy's accident?

For Dan had arrived at the conclusion that there was a serious mystery connected with the man who carried the rat-trap, and whom Billy had declared was masked. The young fellow's caution forbade his taking anybody and everybody into his confidence.

The strange man had been lingering about the plant of the Darringford Machine Shops all the evening, it was likely. It was a natural conclusion that he had been there for no good purpose—especially as he seemed so desirous of escaping observation. Dan felt that the matter should be reported to the Darringfords, or their representatives, instead of being made a matter of public gossip.

It was this thought that caused the young fellow to slow down when he saw a red light beside the road. He remembered that he and Billy had passed here an excavation which had been made\in the street for the laying of water pipes. There was a tool shed here and a watchman was smoking his pipe beside the shack. From this man Dan procured a stout rope.

Without his bicycle he was some minutes returning to the gully where Billy was held prisoner. Indeed, when he did arrive he was greeted by a hollow voice from the bottom of the well, with:

"I say! I thought you would never come, Dannie. What kept you?"

Dan told him, while he made arrangements to let down a noose and so pull his brother to the surface. He found a log which he dragged across the mouth of the hole. Standing on this he let down the rope, Billy slipped one leg into the noose and Dan (who was very strong for his age and size) began to draw him up. The younger lad caught at the sides of the basin and aided in his own rescue to a degree; but an injured ankle made this the more difficult.

Finally he sat on the ground, holding his ankle, and thankful indeed to have escaped. Dan was serious over it!

"This is a bad scrape, Billy," he said. "Can you ride?"

"Get me on the wheel and I'll make her go with one pedal," declared Billy, between groans. "I reckon I haven't broken anything; put I gave the joint an awful wrench."

"It's going to knock you out of delivering the milk this morning, boy," added his brother, with increased anxiety. "Yes! it is already past midnight. We must get home as fast as we can. The folks will be worried."

"But what will we do about that fellow we were chasing?"

"We never should have followed him," grumbled Dan. "If we had minded our own business you wouldn't have got into the hole."

"Oh, I know all about that," returned the younger boy. "But the Darringfords ought to know about that fellow. There's trouble brewing."

It was after one o'clock when the Speedwells reached home. There was a light in the kitchen, and they found their mother there. She was, naturally, worried by their late return. There was no time for Dan to go to bed, for he would be obliged to do Billy's share of the chores as well as his own. Mrs. Speedwell pronounced Billy's ankle merely sprained, when she had examined it; but he could not go on his route that morning.

"I'll get off as soon as I can and carry my milk," said Dan. "Ask father to drive in Billy's wagon, and I'll meet him when I have been around my route, and will deliver to Billy's customers. That's the best we can do."

Dan hurried around his own route as fast as possible. When he met his father with Billy's wagon it was only half past six; but that was pretty late for some of the younger boy's customers. At Dr. Kent's house Mildred was waiting at the side gate, looking up and down the street for the milk wagon.

"You boys must have overslept yourselves after that run to the Falls," was her greeting. "And where's| Billy?"

"He met with a small accident. Hurt his foot," returned the young Speedwell lad, lingering a moment at the gate, for he was fond of Mildred.

As they spoke together Chance Avery came quickly along the sidewalk and, without noticing Dan, spoke to the girl:

"I hope you are going to be with us on Saturday, Miss Mildred?"

"I sha'n't miss that run to Barnegat if I can help it; but I'm not sure that I can get a motorcycle."

"Oh, I hope you will!" declared Chance. "We want all the lady members of the club along."

"And how about the members who can't get motors?" put in Dan.

"It's not too long a run for a bicycle," said Chance, shortly.

"It's too long at the pace you set," was Dan's quick response.

"Oh, you duffers make me tired!" exclaimed the captain of the club. "You'd better go off by yourselves and start a club of your own."

The sneering tone Avery used stung Dan Speedwell to anger, although he usually was master of his temper. He turned back to the gate, saying quickly:

"I do not speak for the minority of the club, Avery, but for the majority. And for the majority of the original members, too. We could have opposed the membership of anybody who used a motorcycle if we liked; but that would be a dog-in-the-manger business. We're not all able to own power machines; but I believe those who only ride bikes should have consideration shown them in the planning of the club runs and in the pacing of the same."

"You think a whole lot, don't you?" sneered Avery. "Run along and deliver your milk, sonny. If you don't like the way I run the club, get up at a proper time and in a proper place, and kick about it."

"I certainly shall do that," declared Dan, more coolly, but with increased anger.

"Then that's all right," said Chance, and, turning his back upon Dan again, he tried to monopolize Mildred's attention.

But the doctor's daughter showed her disapproval of Avery most emphatically by hurrying into the house with the bottle of milk, while Dan drove away. As soon as he had delivered the last bottle he went to the offices of the Darringford Shops. His intention was to see young Robert Darringford, if possible; but, by ill luck, he met Mr. Francis Avery, the superintendent.

"What do you want, young man?" asked the superintendent, halting for a moment on his way out. He habitually was brusk and domineering; and as he prided himself upon settling small matters off-hand, he probably thought Dan was looking for work.

"I chanced to make a discovery last evening—or, my brother made it—that I believe you and Mr. Darringford should know about, sir," said Dan.

"What discovery? Who's your brother—an inventor?" asked the superintendent.

"No, sir. We were riding past the rear of the shops on our bicycles, when we saw a man lurking about there—we saw him twice—at the time we were running over to Upton Falls, and then again as we returned."

"Humph! what was the matter with the man? What was he doing?"

"I could not tell you that. But he seemed desirous of hiding from observation on both occasions when we saw him, and Billy was sure he wore some kind of a mask over his face."

"A mask! Tut, tut! you've been dreaming," cried the superintendent.

"No. We were wide enough awake," said Dan, smiling. "We followed him into the gully across the road, in fact, and my brother fell into a hole there and hurt his foot. That's how the man got away without our learning his business."

"Come, come!" exclaimed Mr. Avery. "This sounds a good deal like nonsense."

At the moment the office door opened and Chance Avery came in.

"Hullo, Frank!" exclaimed the younger Avery, greeting his brother.

"Here, Chance," said the superintendent, quickly. "Maybe you know something about this."

Chance came forward and saw Dan. He scowled.

"You were on that run of the bicycle club last night," said the older brother. "Did you see anything of a man in a mask lurking about the back premises of these shops?"

"A man in a mask! I should say not!" exclaimed the captain of the wheel club.

"I don't see how you and your brother could have seen anything of that kind and the other members of your organization be ignorant of it," said the superintendent to Dan, doubtfully.

"What! is that fellow giving you this cock-and-bull story?" exclaimed Chance Avery. "I wouldn't place too much credit in what he says."

Dan Speedwell uttered an angry exclamation and stepped toward the younger Avery; but Frank opposed him.

"Hold on! we won't have any quarreling here," he said, sharply. "You'd better get out, and don't bring into the offices any more foolish stories about masked men, and the like. We don't pay for such information."

The sneer, and the slur cast upon his honesty, enraged Dan Speedwell. He turned on his heel, however, and, without a word, left the offices of the Darringford Machine Shops.

DAN SPEEDWELL had been up the road with the double wagon picking up the milk from the dairies, while Billy did the chores. Mr. Speedwell did not own enough cows to supply all their customers. The older boy backed the team into the pocket by the milk-house, and set the big cans in the cooler for the night. It was Friday evening—the day before the big run to Barnegat.

As Dan was about to unfasten the tugs of the off horse, Billy, who was half way up the granary stairs, gave a sudden whoop.

"Look there, Dan! Fire!"

The older boy ran up the little incline to the front of the barn. The evening was already closing in, and it was dark enough so that the single tongue of red flame streaked the dark background of the sky like a flaming torch.

"It's in town!" gasped Dan. "Do you suppose it is the Court House?"

But Billy could locate the fire better, being so much higher from the ground.

"It's the shops—it's Darringfords'!" he shouted. "There go the bells, Dan! It's a big fire!"

The fire alarm now rang out clamorously. Every bell in town had taken up the tocsin. Riverdale had no paid fire department, but the gongs would arouse the volunteer company, and every active citizen as well.

Dan dashed back to the impatient Bob and refastened the harness.

"Come on!" he shouted to his brother. "We'll drive down and see if we can help."

Billy was in the wagon as quickly as Dan himself. As they drove out of the yard their mother and Carrie came to the door.

"Fire!" shouted Billy. "The machine shops are burning."

"Be careful of the team, boys!" cried their mother, warningly.

But Dan was not likely to endanger the horses. When they drove into town everybody was running toward the far side where the machine shops were situated, and the flames were then wrapping the tower of the biggest building of the plant in a fiery mantle.

The older Speedwell lad fastened the horses securely behind Mr. Appleyard's store. Then he raced with Billy toward the scene of the conflagration, joining an ever increasing crowd of excited men, women and children. Several hundred persons had already assembled. The fire in the central structure of the great shops had gained already terrific headway.

Hose was already attached to the fireplugs in front of the machine shop when the Speedwell boys arrived. The volunteers had entered the main building from two points; but these streams of water seemed to have little effect on the fire.

"It started with an explosion—I heard it!" exclaimed Biff Hardy to the Speedwells. "We were just sitting down to supper. I tell you, if it had happened when all the hands were at work, a fire spreading as quick as that would have caught some of us."

"And is everybody out of the main building?" asked Dan, anxiously.

"Sure! I saw Johnny Pepper, the watchman. And who else would be around the place after hours?"

"Nobody in the offices?"

"Mr. Avery stays sometimes; but there he is over yonder," said young Hardy.

Just then a furiously driven pair of horses, drawing a light carriage, dashed up to the edge of the crowd. Many of the spectators turned to look at the old gentleman who sat beside the negro driver, and who leaned from his seat shouting for Frank Avery.

"It's old Mr. Darringford!" the word went around.

"Where do you suppose Robert is?" asked Billy Speedwell of the group of his chums with whom he stood.

This question was being repeated all about them. Of late the younger Darringford had controlled the business, and his father seldom appeared at the shops. Billy Speedwell drew nearer to the carriage, his curiosity aroused. He saw Mr. Avery, his face flushed, and his manner excited, shoulder his way to the front, and Billy was near enough to overhear what passed between Mr. Darringford and the superintendent.

"Oh, Mr. Darringford! isn't this dreadful? Isn't it a shame?" stammered the superintendent. He was a woefully excited man, not at all his brusk and assured self.

The old gentleman paid no attention to his superintendent's words. He fired one question at him—sharp as a whip- crack:

"Where's Robert? Where is my son, Mr. Avery?"

The superintendent's countenance blanched, the color receding and leaving his cheeks perfectly white. He glared at the old gentleman for some seconds quite speechless.

"Where's Robert?" cried Mr. Darringford again, rising in his seat. "He was to stay to-night to look over those specifications for the Woodford order. He telephoned home at ten minutes past six. He said he was alone then in his office. Have you seen him?"

Avery at last found his voice; but it was weak indeed. "No, sir. I haven't seen him," he whispered. "I—I forgot he was to remain after the shops closed."

Somebody grabbed Billy by the arm then. He turned to see his brother, and Dan's eyes were sparkling with excitement.

"Come here!" the older Speedwell said. "What did you tell me about the hole in the wall of that old catch-basin? You remember!"

"I should say I did," replied Billy. "When we were chasing that man with the rat trap?"

"Sh! Come away from the crowd. There is a culvert from that old well into the yard of the machine shop. It used to open directly into the court between those buildings."

"The culvert was open all right when I tumbled into the hole," murmured Billy, still puzzled by his brother's vehemence.

"Come on, then!" cried Dan, vigorously, and having reached the edge of the crowd of spectators, he set off on a sharp run toward the back of the machine shop premises. Billy kept up with him, despite certain twinges in his lame ankle. Breathlessly he demanded:

"What's got you, Dan?"

"I had another talk with that old man who loaned me the rope to get you out of the basin. He says the culvert has a loose grating over it in that court. And Mr. Robert's private office windows look into that court. Do you see, Billy?"

"Oh, Dan tell somebody—let's get them to help us!" cried the younger boy.

"We'd have to stop and explain it all. Maybe they wouldn't believe us," answered Dan. "Come on, Billy! You can let me down into that hole, and if the culvert is open I'll find my way through it."

The log Dan had dragged across the hole when he rescued Billy from the place, had not been moved. The older Speedwell lad threw off his coat, saw that his brother was safely placed astride the log, and then let himself down by the tails of his jacket, Billy clinging meanwhile to the arms. The garment was strong, and it enabled Dan to lower himself until the soles of his shoes were four or five feet from the bottom of the basin. When he let go and dropped he fortunately landed without hurting himself.

"All right, Billy!" he called up. "The culvert is open, I see. And I've got plenty of matches. You stay right where you are till I come back."

Billy promised, and Dan entered the old drain, which was made of cement, and was nearly three feet in diameter. He was, as he had said, amply supplied with matches, and he scratched one after another as he hurried through the culvert; sometimes scrambling on his hands and knees, but, for the most part, running in a stooping posture. The slightly ascending passage was easily climbed; there was no rubbish to retard him. In less than a hundred seconds after last calling to his brother, Dan Speedwell had entered under the fence, crossed the space of the machine shop yards, and passed beneath the foundation walls of the inner half of the main building.

The boy hesitated. Impulse had urged him on; but it seemed as though he could venture no farther. And for what purpose? The court in the middle of the office building must be a mass of flames. Nobody could be alive there now.

And even as Dan Speedwell shrank before the breath of the fire, a scream rose above the roaring of the flames; and then an agonized voice cried:

"Help! help! Save me!"

With an answering shout Dan sprang forward. He reached the grating that covered the end of the drain. In the glare of the flames he saw a blackened countenance pressed close to the iron bars, while two hands shook the grating madly. Disfigured as the victim was, young Speedwell recognized the face of Robert Darringford!

THE grating over the throat of the old drain was an iron frame with the bars welded to it. The whole lifted out in one piece; but it was evident to Dan Speedwell at first glance that the grating was rusted in, and that Mr. Darringford had already put forth all his strength to dislodge the drain-cover, and had failed!

Blazing brands were dropping all about the imprisoned man. At the bottom of that airshaft, or court, in the middle of the building, Darringford had no chance of escape, save through the drain. Meanwhile he lay exposed to the rain of burning debris, scorched by the flames and almost smothered by the smoke.

But Dan Speedwell's acute mind had already planned his rescue, and now he was not to be daunted.

He dashed at the grating from the under side. A sudden current of air sucked the smoke down into the drain and Dan was all stifled; but he fought his way to the opening and seized the bars. For an instant he touched one of Mr. Darringford's burned hands, and he heard the young man cry in agony.

That exclamation of pain inspired Dan to do his utmost. He gave no heed to his own danger. The drain had come almost to the surface of the court, and Dan was able to creep up under the grating and get his back against it.

Then, on all fours, stung by innumerable falling cinders, the boy braced against the grating and heaved with all his might. He felt the grating give, and wondered why he could not raise it altogether. For half a minute he struggled to rise and push up the ironwork.

And then he realized that Mr. Robert Darringford had fainted and lay—a dead weight—upon the cover of the drain!

The man was big, and an athlete, weighing more than one hundred and eighty pounds; Dan Speedwell, though a sturdy young fellow, was not able to bear that weight, with the heavy grating likewise, on his shoulders. He had to give over the attempt and for a moment feared that Darringford's unfortunate collapse had cost him his life.

Then suddenly the man above moved. He rolled sideways, and cried again. Part of a burning latticework had fallen from the roof and the sting of it across Darringford's shoulders made him writhe, and, in the fact, brought him to his senses. Dan's face was scorched by the flaming debris as well; but he fought back the cry of pain that rose to his own lips, and again heaved up against the grating.

It gave way. Mr. Darringford rolled farther off and the boy was able to force aside the barrier.

In a moment he climbed through. He could not see the man for the smoke that had settled to the bottom of the shaft again. And through this vapor fell the blazing brands, as impossible to dodge as raindrops.

"Mr. Darringford! Mr. Darringford!" cried Dan, and in his own ears his voice sounded hoarse and distant.

He staggered about the place, his hands outstretched, groping in the murk for the man he had come to save. Finally he fell upon his prostrate body, and this aroused Darringford once more.

"Get me out! get me out!" Dan heard him mutter.

The boy shouted in his ear: "Get down into the drain! Hurry up! We'll both be buried under this falling wreckage if you don't! This way—this way!"

He pushed the bewildered man to the opening. Darringford sprawled through like a huge frog. His boots waved for a moment before Dan Speedwell's face, and then he slid down the rather sharply inclined drain, out of sight.

"Keep on! Keep on going!" shouted Dan, and was about to follow him when a sound from above made him turn and look up. It was a tearing, rasping crash—the breaking asunder of brickwork and iron. A mass of brick and mortar fell directly in front of him.

Dan leaped backward and leaned against the wall of the building. Where he had stood beside the entrance to the old drain, the rubbish fell. His escape had been by a narrow margin. But his feeling of thankfulness for this was but momentary. The great pile of rubbish had completely buried the mouth of the drain. The man he had come to aid would—perhaps—escape; but Dan Speedwell was left at the mercy of the flames and smoke!

"I'll be buried alive if I stay here!" groaned the boy, and impulsively he turned to the building wall behind him, found an open window, and climbed over the sill.

He had scarcely fallen upon the floor of this room when, with a roar, one sidewall of the shaft fell in completely. A lot of the rubbish burst in the upper part of the window behind Dan. It rained all about him and he staggered blindly through the smoke away from the opening. He found a wall, then a door; opened it, and dashed out of the room.

He had come into a corridor he knew, and the smoke was less dense. Wisely he dropped to the floor and there, on all fours, found that he could breathe more easily. But he could not see, and scrambled blindly along the corridor, finally bumping his head sharply against the newel-post of a stair.

It was a flight leading upward. Behind him, at the far end of the corridor, the flames were crackling. The rolling smoke began to be tinged by a deep yellow glow, Dan knew that the fire was following him.

The smoke and heat were dreadful. Dan thought at that instant that he would be overtaken on the landing. But he staggered around the turn of the stairs and found himself at the foot of another flight. His shoulder crashed against a window, and the glass splintered. Instantly the smoke was sucked through that opening, and realizing that this vent might aid him, Dan flung up the lower sash as far as it would go. The smoke poured out of this aperture and the boy saw that the flight of stairs above him was clearer.

Thankful indeed for this small respite, he stumbled up to the third floor. At the bottom of the next flight was another window and he opened it. He realized then that he was facing the street on which the building fronted. There was a wide lawn before the factory, and this open space was occupied by the fire apparatus and the crowd that had gathered. He heard the murmur of the people's voices, and the swish of the water through the hosepipes.

But the boy remained here only for a moment or two. The fire was driving up the stair-well behind him. He was forced to seek a refuge above and he turned to mount the next flight. Then he uttered a cry of exultation.

"A door!"

At the foot of these stairs swung a heavy door. Dan darted up two steps and pulled the portal shut behind him. The spring lock clicked sharply, and he was in perfect darkness. It was a tightly fitted door and little smoke could penetrate the cracks. After a minute or so, he could breathe quite easily.

But the heat in the shut-in place was intense and Dan soon began to climb upward again. He knew this respite was not for long. The flames were following him up, and up.

On the fourth floor he stopped again. It was little lighter in the narrow hall than on the staircase, but in fumbling about he discovered a door. He fell against this, threw it open, and knew at once that he was in one of the long draughting rooms. The windows of this room at the rear looked out into the airshaft from which he had so providentially escaped when the wall fell. At the other end they overlooked the open space before the main door of the building. Almost as Dan entered and closed the door behind him, one of the rear windows, overheated by the fire, cracked and the flames poured in!

The fire swept in at the window, licking up the woodwork until, in a few seconds, it was advancing in a wall of flames that spread from one side to the other of the great room, and reached from floor to ceiling.

The scorched and breathless boy turned again to flee. He missed the door by which he had entered and stumbled on to the front windows. The smoke was filling the draughting room now, and the heat grew in intensity, second by second. He threw up one of the great windows for the sake of air.

It was an almost fatal act. The draught thus created sucked the fire along at twice its former speed. Dan fell across the sill and hung there, the curtain of flames behind, the smoke belching out about him in a stifling cloud.

MEANWHILE Billy Speedwell, astride the log over the old catch-basin, was becoming very much worried indeed. And for good reason.

Down there in the gulley behind the machine shops he could see nothing of the fire but the growing illumination against the overcast sky, and could only hear a murmur of the throng gathered on the other street—the street on which the big office building fronted.

And Dan had been gone a long time.

"Something has happened to him," thought the anxious Billy.

And forgetting the promise he had given his brother, to remain where he was, Billy began to look about for some means of getting to the bottom of the basin. This he found in a stout cedar pole lying near by, down which he climbed.

Billy was well supplied with matches, too. He went boldly into the drain, and finding it comparatively clear of rubbish, he only struck a light now and then, sheltering the tiny flames in his cupped hands as he pressed forward.

The smoke stung his eyes and throat and the atmosphere grew painfully warm as he advanced; but Billy pressed forward until he reached the first grating in the roof of the drain. The smoke, driven to the ground in the yard of the machine shops in a sort of whirlwind, was finding an outlet through this grating, and Billy could scarcely breathe until he was past it.

A few yards farther, while groping ahead in the darkness, he stumbled over an object lying on the bottom of the drain. In fact, he sprawled upon it completely, and at the first touch Billy Speedwell screamed aloud.

"Dan! It's Dan!" he cried. "He's dead!"

Creeping off the prone body, he found a match in desperate haste and scratched it on the dry cement wall. When it flared up he could see the motionless body, and still believed it to be his brother until he managed to roll it face upward.

"Mr. Robert! And he's alive!" cried Billy, as the match burned down to his fingers, and he had to drop it.

The younger Darringford was badly burned, and was blackened by smoke. But he moved and groaned at that very instant, proving to Billy that he was by no means dead. Young Speedwell was still thrilled with anxiety, regarding Dan.

Without trying to arouse Darringford he pushed on through the drain, facing the smoke and heat. Dan was somewhere beyond and Billy feared much for his brother's safety. Suppose he, too, had fallen in the narrow passage, overcome by the heat and smoke?

And perhaps, when Billy reached the end of the drain and discovered it to be choked with the mass of debris that had fallen into the inner court, he would have been relieved to find Dan in the same plight as Robert Darringford!

Was poor Dan under that pile of rubbish? Billy, illuminating the choked end of the drain with another match, could not keep the tears from flowing. The keen edge of his sorrow was sharpened by the fact—and he appreciated that fact almost instantly—that he could not dig into the pile to find his brother's body.

How was it that Robert Darringford had been saved when the wreck fell, and not Dan? Billy could easily believe that his brother had sacrificed himself to save the young master of the machine shops!

And with Mr. Robert was the key to Dan's disappearance. Billy, realizing this, hurried back to where the man lay. The latter had partially aroused, and was crawling painfully down the drain, away from the heat and smoke.

"I'm hurrying! I am hurrying!" he muttered.

"I—I thought you were shut out of the sewer. How did you escape?"

Billy knew that Mr. Robert took him for Dan. And the words explained completely what Dan had done. His brother had crawled out of the drain to help Mr. Darringford, had pushed the latter down to safety, and then had either lost his life under the falling rubbish, or had been cut off by it.

If his brother had escaped immediate death, Billy knew he was shut away from retreat through this drain. And if he would help him, it must be from some other direction.

Alone, Billy could have very quickly found his way to the end of the drain again; but he had a duty to perform in helping the half-conscious Darringford. Finally the boy was obliged to seize the man under his arms and, staggering backward, drag him to the end of the drain.

Here the air was clearer. Billy could not possibly get Darringford out of the well; but it was an easy matter for him to swarm up to the surface himself. Leaving the man there, Billy sped away from the gully, and around to the front of the machine shops.

As the boy came upon the main scene of the conflagration a great roar of sound went up from the throng. A puff of wind, driving the smoke aside, had cleared a space around a certain window on the fourth floor of the building. And at that window a figure, outlined against the curtain of fire behind, appeared to startle the crowd.

"Mr. Robert! Young Darringford!" voices called.

Even the old gentleman in the carriage believed it was his son at the window and, standing upon the seat, he turned his quivering face upwards, unable to speak, but wringing his hands in agony. A wave of smoke then wiped out the picture at the window, and Mr. Darringford sank back with a cry that went straight to Billy Speedwell's heart.

Billy knew it was Dan up there—and Dan must be saved! But first he could comfort the heart-broken father.

"Mr. Darringford! Mr. Darringford!" shouted the boy, springing upon the carriage step so as to be heard above the general confusion. "Robert is all right—he's saved from the fire."

The old gentleman turned to gaze upon him in amazement, and others in the crowd drew near to listen.

"That's my brother Dan up there—Dan Speedwell," Billy hastened to explain. "Mr. Robert is all right. He's down yonder in the old catch-basin. Dan got him into the drain, you know—"

"What are you saying, boy?" demanded Mr. Darringford, suddenly recovering command of himself.

"I know what he means, sir," declared the driver of the carriage. "There is an old drain, and it empties into a well back there in the hollow on the other side of the pike."

"Right!" exclaimed Mr. Darringford. "You say my son is there, boy? Henry! drive out of this crowd at once. We must see if this is true—"

And Billy was fairly hurled from the carriage step, the driver wheeled the restive horses so quickly. The carriage whirled away, while Billy picked himself out of the dust.

"What do you think of that?" gasped the boy. "And they never gave a thought to poor Dan!"

"Do you mean to say it's Dan up there in the window of the draughting room?" shouted somebody in Billy's ear.

"Yep! He went through the old drain and got Mr. Robert out somehow; then the drain got choked with fallen rubbish. He's cut off."

"We've got to get him out!" exclaimed the boy's questioner, and Billy recognized Biff Hardy.

"How can we do it? There's no ladder long enough to reach the fourth floor."

"There he is again! It is Dan!" cried Hardy.

By this time many of the spectators were aware that a boy, and not a man, stood at the window of the draughting room. The smoke billowed through the open casement all about poor Dan, and now and then it was sucked away and revealed him clearly in the firelight.

"Billy!" cried Biff, in the younger boy's ear, "Dan can save himself easy, if he only knew what I know."

"What do you mean, Biff?" cried Billy.

"There's a rope up there. A big coil of it. There's a coil in every room, and the one in the draughting room is hung under the very next window to the one Dan's at. It's there for a fire escape—"

"Oh! we must tell him!" gasped the younger Speedwell.

But even as he spoke, Billy realized that the sound of the rushing water and the voices of the crowd and the excited firemen would drown his own or Biff's voice—drown the sound completely! And, even were that not so, the roar and crackle of the flames would make it impossible for Dan to hear what was shouted to him from below.

"If we had a megaphone," cried Biff.

The captain of the hose company, however, had smashed his megaphone a few minutes before. And that instrument would not have carried the sound of their voices to Dan. Billy's brain seemed paralyzed for the moment. How could he get to his imperiled brother information of the fire rope hanging almost within reach of his hand?

BILLY SPEEDWELL, for a very few seconds only, remained inactive and nonplussed. He was thinking rapidly.

What would Dan do if he were in Billy's place, and it was Billy who was up there in that window, far above the heads of the crowd, threatened each moment by the advancing fire? That was the question that pounded in Billy Speedwell's ears.

"Quick, Biff!" shouted Billy. "Come over here and clear the folks away a bit. Make a circle with me in the middle. We'll attract Dan's notice, and then I can signal him. Hurry!"

There was an automobile standing near; but the men who had ridden to the fire in it were helping fight the blaze. Billy shouted to Biff Hardy to lift off a headlight of the machine. Then, standing upon the step, Hardy turned the lamp upon Billy, who stood out in the cleared place, facing the burning building.

The crowd, curious as to what the boys were doing, threatened to draw in and fill the empty space.

"Keep back! Keep back!" cried Billy. "Give us a chance to save my brother! Don't you see that he'll die if we can't get him out of that window in another minute?"

"What can you do for him down here, boy?" demanded one man.

"Watch me!" returned the confident Billy. "Keep back, please!"

"Keep away!" yelled Biff Hardy, shooting the ray of the headlight into the faces of the throng for an instant. "Give him air! Keep back!"

The people on the outskirts of the crowd thought somebody was hurt, and stopped pushing. Just then the smoke cleared from Dan's window again and the imperiled boy was seen by all. A murmur of apprehension rose from the throng; but nobody seemed to be able to suggest means for his release.

Billy, standing squarely in the glare of the light, struck an attitude—with arms outspread and legs apart—and then, with one hand and arm, stiffly signalled his brother's attention. He worked his arm like a semaphore; any person familiar with the code of signals used by the army and the naval battalion would easily understand Billy's motions.

And Dan understood!

The younger boy was sure he would. He and Dan had often practiced signalling in just that way, from the hill back of their house to the roof of the shed—one standing upon each pinnacle.

Having gained Dan's notice, Billy rapidly spelled out the information he wished to convey. There was a coil of rope, long enough to reach from the fourth floor to the ground, hanging under the very next window in that draughting room, and Billy signaled this fact to his brother in a very few seconds.

Dan waved both hands to show that he understood, and darted back from the open window. Almost as he disappeared a tongue of flame, followed by a great balloon of smoke, belched out of the open casement.

A cry of horror arose from the crowd. Many thought that Dan Speedwell had been sucked down into the vortex of the fire!

But Billy had great faith in his brother. Now that Dan knew how to help himself, the younger boy was sure he would do so. With Biff Hardy he ran in close to the burning building—so close, in fact, that some of the firemen and town constables tried to keep them back.

"My brother's up there!" shrieked Billy. "We've got to catch him when he comes down the rope."

As he spoke the other window of the draughting room was opened. Dan appeared and, with the flames seemingly framing him as he stood on the sill, he coolly set about the work of saving himself.

The rope was fastened by one end to a ring in the wall. It was all ready to be uncoiled and dropped to the ground. To an athletic person it offered an almost sure means of escape.

But even as Dan poised the coil of rope, and was about to drop it, there was a muffled explosion within the burning building, two or three windows on the second floor blew outwards, and the very wall itself bulged!

Flames and smoke leaped forth. The long, yellow, wicked tongues of fire licked up the side of the structure until they reached Dan Speedwell's feet! This sea of darting flames intervened between his perch and the ground—it shut him off in his attempt to escape.

If he dropped the coil of rope now it would be into the very heart of the fire—that blast would wither the strong hemp as it would pack-thread!

Dan Speedwell was in terrible danger—none knew it better than he did himself. Nevertheless, throughout all this frightful adventure he had not for a moment lost his head. He must do something now, and that within a very few seconds, to save himself from actual annihilation; yet he did not hesitate.

He threw up his arm to attract the attention of those below. The smoke parted sufficiently for all to observe him. Then he whirled the coil of rope about his head, and flung it from him, as far as he could send the hurtling line.

Billy and Biff Hardy were two who sprang forward to seize the end of the rope. It was several yards longer than the distance from the window to the ground, and that was indeed a fortunate fact.

Billy understood Dan's frantic gestures; others saw the single remaining chance for the boy's escape, too. A dozen pair of sturdy hands seized the end of the rope; they dragged it out to its full length, and as far from the leaping flames as possible. The cable stretched on a slant from the window sill on that fourth floor to the ground; but between the crowd holding the end of the rope and the window there rolled a cloud of black smoke, through which darted angry tongues of fire.

Dan Speedwell, however, was not balked. Indeed, he had no margin of time left him for hesitancy. The fire was below him, behind him, above him; he was surrounded by the flames. Half a minute more and they would lick him off that window ledge, and he would fall to the ground.

Therefore the brave boy launched himself from his perch upon the rope. He wound his legs about the taut line and slid backwards. He shot through the wave of flame and smoke below him at a speed that burned the palms of his hands. He landed in the arms of Billy and young Hardy, and a cheer went up from the crowd that drowned for a moment the crackle of the fire.

Then, with a thunderous crash, the front of the building for some yards fell outwards! Many of the firemen and helpers barely escaped the flying bricks. Billy and Biff dragged Dan back out of danger, and as far as the farther side of the street.

A gentleman pushed his way through the crowd that was congratulating the boys, and shook hands with Billy. Dan's hands were so raw that he could not bear to have them touched; and as soon as Biff caught sight of the gentleman, he slipped away.

"Fine team work that, boys!" declared this person, warmly. "You're a plucky pair of youngsters, and the town ought to be proud of you. Let's see; your name is Speedwell, isn't it?"

"Yes, sir," said Billy. "Come on, Dan. Let's go over to the drug store and get something done for your hands. And you're all scorched, too."

"He's been in a hot corner," said the gentleman, keeping pace with the Speedwells as they moved away. "I am told that it was by your aid that young Mr. Darringford was saved out of the fire. His father has just driven off with him."

"I'm glad he got out," said Dan, fervently. "I thought he might have been lost, after all."

"It seems you went through the old drain and found him, didn't you?" asked the man.

Dan briefly related the adventure, and the other listened attentively, until the boys went into the drug store.

"Say, Dannie," said the younger Speedwell, "you sure spread yourself that time. And mother will be scared to death when she hears it."

"What do you mean?" demanded Dan. "Don't you tell her the particulars."

"She'll read it all in the Riverdale Star. Didn't you know you were talking for publication?"

"What! Me?" gasped Dan.

"Yep. That was Jim Blizzard, editor of the Star. When it comes out to-morrow you'll be a sure-enough hero."

BILLY was right on that point. The Star ran a special edition, more than a page of which was filled with an account of the disastrous fire at the Darringford Machine Shops. The main building of the plant was utterly ruined, and would have to be torn down; but fortunately the other buildings were not consumed, and the laboring people were not thrown out of work. A building in town was already secured for the clerks and draughtsmen, and work would be resumed in all departments within a few days.

This much was mere information; so, too, was much of the story of the fire, for Mr. Blizzard was a good writer. But when he came to describe "the heroic rescue of Mr. Robert Darringford," and "Young Speedwell's Slide for Life," he made Dan's ear-tips burn. The young fellow was glad that his burns and scarified palms kept him at home for a day or two.

And Billy was praised by the paper, too. But Billy only laughed when the boys in town chaffed him. As, for a couple of days, he delivered the milk to all their customers, he had plenty of opportunity to discuss with curious people the topic which seemed to appeal most to them: "What will the Darringfords give you and Dan?"

Now, this question annoyed Billy; and it actually made Dan angry.

"I didn't help Mr. Darringford out of the fire for pay, nor did Billy," Dan said, sharply to one curious neighbor. "And I am very sure the Darringfords will not offer us money."

And, for the time at least, the Darringfords had something else to think about. Mr. Robert was ill in bed and his father took immediate charge of the machine shop affairs. Frank Avery had recovered his usual brusk and confident manner, and was threatening condign punishment for the one who had set the plant afire.

For that the conflagration was the work of an incendiary, there could be no doubt. The suddenness of the breaking-out of the flames, their rapid increase until, within a very few minutes they were beyond all control, showed plainly that the fire had been planned for. And the setting of the fire had been an act of such ingenuity that the local police, as well as city detectives, who were brought to the scene, were unable to point out the method followed by the criminal.

The one thing upon which the police and detectives agreed was the fact that the fire must have been caused by some mechanical device which acted after the workmen and clerks were out of the plant for the night. The object of the incendiary was to destroy property, not the lives of innocent persons. It could not be considered, even, as a direct plot against Robert Darringford, for it was not known until closing time, and then only to a few, that the young man intended to remain in his office after hours.

Billy was in town one afternoon, and with some of the other boys went to watch the workmen removing the walls and fallen debris of the burned building, as the Darringfords desired to rebuild as soon as the site could be cleared. In a city the space would have been roped off about the wreckage; but in a small town like Riverdale the police took no hand in such matters.

One of the boys with Billy Speedwell was the son of the contractor who was removing the rubbish, and therefore nobody challenged him or his friends when they climbed into the hollow where the bell-tower had stood.

This place had been first cleared by the detectives, searching for indications of incendiarism. The boys were able to jump down into the old basement and overhaul the half-burned beams and broken furniture. In a corner Billy came upon something, which at first glance interested him.

It was a common wooden box, with a sliding cover, some two feet long and eighteen inches high and wide. One end had been burned away; but inside were shreds of waste and half burned shavings; and back, in the unburned end, some kind of a wire cage.

Billy pushed back the slide and looked closer. In the box was a rat-trap, and beside it, and wired to the trigger of the trap, a contrivance of wheels and springs which Billy recognized as the works of a cheap clock.

"What you got there, Billy?" asked Jim Stetson, looking over the lad's shoulder.

"I don't just know. You don't suppose it's of value, do you, Jim?" added Billy, quickly.

"What! That thing?"

"Then your father won't mind if I take it away with me?"

"Of course not. Why, say! it's only a rat-trap. Johnny Pepper must have set it down here before the fire."

Billy made no reply. He wrapped the half burned box in a sheet of paper which he found, and carried it away under his arm. The contrivance had no real value; but Billy wanted to show it to Dan.

He carried it home and at the first opportunity showed it to Dan. He did not tell his brother where he had found the cage- trap, but just asked him what he thought it was.

"Looks like you got it out of the fire, Billy," said the older boy. "Did you?"

"Never mind where I got it. Just say what you think it was built for."

Dan, seeing that he was in earnest, gave the contrivance his full attention. Although one end of the box had been burned (and seemingly some of the contents) the wire trap and the clock works were intact. The latter was fastened to the trigger of the trap very ingeniously. Dan soon found that, by winding the clock and setting the trap, he had a mechanical contrivance that worked perfectly without, as far as Dan could see, being of the least use.

"What under the sun did anybody ever want to rig a thing like this for?" he demanded of Billy. "Surely not to catch rats. You see, when the clock runs a certain length of time, it pulls the trigger of the rat-trap and snaps it shut. But what was there to catch? And it has been in a fire, Billy. I believe you must have got it down to the machine shops."

"Where did you see a rat-trap like that last?" demanded his brother.

"Me? I don't know. Not for a good spell, Billy. We haven't had one like it around the barn for an age."

"No. But we saw one not long ago."

"Not me!" declared Dan, earnestly.

"Well, I did, then; and I told you of it!"

Dan interrupted him with a sudden exclamation.

"You don't mean the man we saw that night we went to Upton Falls? The man with the mask? I had forgotten all about him."

"And I tell you he had a trap like this under his arm when he ran away from the machine shop fence," said Billy, with confidence.

Dan nodded. He gave his attention to the article before him for some minutes in silence. Then he sighed and shook his head.

"I don't understand it," he said. "You did find this in the ruins?"

Billy told him just where.

"That's where the fire broke out," declared Dan, emphatically. "And this thing was half burned—"

"Wait! here is something." He picked up several bits of wood, nothing more than splinters. He examined them carefully and then held them out on his palm to Billy.

"See? They are half burned matches. They were in this box. Why, Billy! can it be that the fire started in this box? There is a smell of oil about these rags and shavings. It's a mystery that the box did not completely burn; but of course, the fire found an outlet upward. I don't know what to say," he concluded, slowly.

"It is something rigged to start the fire, Dan," said Billy, confidently.

"I wouldn't want to say so. Not without understanding it better," returned Dan. "Let's think it over."

"And take it to the Darringfords? Show it to Frank Avery?"

Dan had a very vivid remembrance of his reception by the superintendent of the machine shops when he had told that self- confident individual about the man he and Billy had seen hanging about the shops after dark. He shrugged his shoulders, and said:

"I reckon we'll let that fly stick on the wall, brother. They don't seem very anxious to hunt us up; I don't see why we should trouble them at this time. It would seem as though we were looking for something."

SATURDAY came, and the mystery of the fire at the Darringford shops was almost neglected as a topic of conversation among the young folks of Riverdale. The Barnegat run of the Outing Club was the important subject under consideration, and, as the hour of two drew near, the public square before the Court House became a lively spot indeed.

There were a number of the members who owned bicycles only, and who had been unable to obtain motorcycles; these were soon in a group by themselves and their excited talk betrayed the fact that the rules under which the run was to be held were not to their taste.

"It's just what I told you," said Biff Hardy. "Chance is bound to break the club all to flinders! You see, aside from the crowd going in Greene's and Henderson's automobiles, there are only twenty-two members with motorcycles. Altogether the club numbers more than a hundred active members. Where are they?"

"That's easily answered," chuckled Jim Stetson, who was just trundling his own motor machine past the group. "They haven't got here yet, Biff."

"And they won't get here!" declared young Hardy. "Altogether there will not be fifty per cent. of the membership show up for this run. It's a hard road. I have been over every foot of it, and I know."

"I hear that Chance says three hours is long enough to spend on the outrun," Fisher Greene said. His brother and sister had invited friends to accompany them in the family automobile, and Fisher had been crowded out.

"Three hours!" exclaimed Billy, excitedly. "Why, there is scarcely a fellow here who can make it in that time."

"I don't care. We leave at two, and the assembly will be sounded at Tryon's Casino in Barnegat at five," said Fisher.

"Why, that's actually brutal," said Dan Speedwell. "Ten miles an hour over such a road is a regular grilling pace. Chance Avery doesn't know what he's about!"

"And who told you so much, and your hair not curly?" demanded a voice behind him, and Dan, as well as the others, looked up to see Chanceford Avery, in his natty uniform, and carrying the bugle slung by a silk cord over his shoulder. He used a "jollying" tone in speaking, but he scowled at Dan.

"Say, Captain," sputtered Fisher Greene, "do you expect the club to be ready to answer to roll-call at Tryon's at five o'clock?"

"That's the idea, youngster," said Chance. "And those that are not on hand will be demoted one class, of course. That's the rule. There won't be any time for you fellows to stop off and rob an orchard, or cut up any other didoes," and the captain laughed unpleasantly, and would have passed on, had not Dan Speedwell spoken again:

"Wait a moment, Avery. We wish to understand this clearly. Are you earnest in timing the run to Barnegat for three hours?"

"I certainly am. Cripples and children had better stay out of it."

"It is ridiculous! If you, yourself, were not riding a motorcycle you could not make it within that time," declared Dan.

Chance flushed and replied angrily:

"You have no authority for saying that, Speedwell. If you mean that you can't do it, that's another thing. Don't limit my powers, please, to ten miles an hour."

"But I do—if you attempted to go to Barnegat on a bike."

"Nonsense!"

"And it means that a large number of the members of the club will not even start, so as not to lose class."

"Well," said Chance, scornfully, "I do not know that anybody will weep if you don't start, Speedwell; or your brother. I'm Captain, and I'm going to do what I think is best in this thing. You can believe that."

"I see you are determined to ruin the club," said Dan, gravely. "But there may be enough of us to beat you at that game."

"Pshaw! if you are such a mollycoddle that you can't keep up the pace, drop out, that's all!" snarled Chance. "But I'm sorry for you fellows if you can't do ten miles an hour."

"We can do it—and we will!" exclaimed Billy Speedwell, suddenly. "You can look for Dan and me at Tryon's, Avery, when you blow the assembly at five."

Dan had strolled over to where a group of the girl members were standing by their wheels. There were not half a dozen who had not obtained, in some way, the use of motorcycles. Mildred Kent and Lettie Parker were among these fortunate ones.

"We'll pace the rest of you girls," declared Lettie, cheerfully. "If you can't come along as fast, why we'll reduce speed and stay with you. Of course you'll be more tired than we are; but we'll all stick together."

"And where will we be at five o'clock when Chance says we must report in Barnegat?" demanded one of her friends.

"We'll report by telephone, if we can't any other way," laughed Lettie. "But I think Chance Avery is just mean!"

"Are you and Billy determined to go, Dan?" asked Mildred, privately.

"Yes. And Billy says we are going to get to Barnegat in the running," replied Dan, smiling. "But I believe we shall do some hard work to accomplish that. And my hands are pretty sore yet."

"You poor fellow!" Mildred said. "And didn't the Darringfords even thank you and Billy for what you did?"

Dan flushed. "We didn't do anything more than other persons would have done, had they known of the old drain. And I'm glad they haven't made any splurge about it. What was in the paper was bad enough."

"I think it was a fine thing for you to do, and Billy was just as brave," said Mildred, quietly.

At that moment the assembly sounded on Avery's bugle. There was a crowd of spectators in the square and they cheered the Outing Club as the members that intended to start the run wheeled into a solid phalanx before the Court House steps.

Avery stood beside his motor until all had assembled. Then he blew a single blast on the bugle, and immediately hopped into his saddle. In a moment the staccato exhaust of his motorcycle began to deafen the crowd along the sidewalk.

One after another the other motorcyclists got under way—amid a good deal of noise, and smell, and dust. Behind them fell in the bicycles, and after they had all moved out of the square, the several automobiles likewise started.

"Don't you want a tow up the hill, Fisher?" cried his sister from the back seat of the Greene car.

"We'll save you some supper, Fish!" cried another of the party. "You'll be dead beat when you get to Tryon's."

"And that's what we'll all be," said Biff Hardy, to Dan and Billy. "See 'em trying to plug up this heart-breaking hill as though it was the last lap. Why, we've only begun! We'll be broken down before we get to Schuter's if we don't reduce speed."

But Billy and Dan kept grimly at it. They thought they knew about how much grilling they could stand, and both had in mind Billy's promise to Chance Avery. They were determined to be at the Barnegat terminus of the run when the captain called the roll.

THE Speedwells were ahead of the other bicyclists when the rear guard got over the first hard hill. Fisher Greene and Biff Hardy were not far behind the brothers; but the remainder of the bicycle riders were strung out for half a mile along the dusty road.

By that time the motorcycles and the automobiles were out of sight. Even Dan and Billy could not see them, for small patches of timber here and there, as well as the general unevenness of the country between Colasha River and Barnegat, soon hid from each other the various parties into which the club was split.

As the stragglers began to drop out, some of them stopping beside the road to rest and others actually turning back towards Riverdale, Dan said to his brother:

"This is bound to bring things to a head. At the meeting next week the Riverdale Outing Club will either vote for an entirely new management, or it will smash entirely."

"We've got the votes, Dan," said Billy, with determination. "We can beat Chance Avery and his friends. They're in the minority."

The Speedwells didn't talk much, however. They saved their breath for the work before them. And the way grew heavier and the pedaling harder the farther they got from Riverdale.

Had the whole club taken an easy pace, and traveled the pleasant highway in company, it would have been a delightful run. The afternoon was warm, but not unpleasantly so. With the motors and autos ahead, the bicyclists were not so much troubled by the dust.

But the grilling work of trying to cover the distance of thirty miles over such a hard road in three hours, took all the fun out of it. It was more like an endurance race than a pleasure run!

They came to Schuter's Hill an hour after leaving town. It was a straight stretch of road to the summit, all of five miles long. Although by no means as steep as the bank of the river, it promised such hard work to the bicyclists, that the Speedwells knew many of those remaining in the scattered rearguard would give up, here the attempt to reach Barnegat.

It was on this very hill, the brothers knew, that the motorcycles and autos would make their greatest gain over the laggards. When they reached the beginning of the rise Dan and Billy sprang out of their saddles by common consent, and flung themselves down to rest a bit. There was a spring beside the road and a fine, wide-armed old oak shading a grassy bank.

The Speedwells were off in a minute, however, and Hardy and Fisher followed them immediately upon getting a drink. They had not rested, and were not prepared as Dan and Billy were for the long and arduous climb. Therefore, when Biff and Fisher were less than a third of the way up Schuter's Hill, the Speedwells disappeared over the top.

It was a quarter to four when they came to the first stretch of descending road. For the most part it was now all an incline to their destination. The worst of the run was over—their hardest work was behind them.

"My goodness! isn't this a relief?" cried Billy to Dan, putting his feet on the rests and beginning to coast down the small hill before them.

"I believe we will make it on time, boy," returned his brother. "Hello!" he added. "Who's that ahead?"

There was a figure at the bottom of this small hill; it was one of their fellow-members, and in a moment Billy cried:

"He's got a motor machine. One of 'em's broken down, Dan."

"You say that with considerable satisfaction, Billy," remarked Dan.

"Humph! well it does make me mad to think how easy they are getting over the road while we are pedaling away for dear life."

"And you'd be delighted to travel just as fast as they travel, Billy," Dan reminded him again. But Billy's eyes were fixed upon the chap at the foot of the hill. In a moment he gave voice to another excited exclamation.

"Don't you see who it is, Dan?" he asked, turning to his brother, who was coasting down the slope by his side.

"Why—it's—"

"Avery! Chance Avery!" sputtered Billy.

"Something's happened. Why is he away back here?"

"I don't care what has put him back," declared Billy, with vigor; "but I'm more than glad that something has gone wrong with him."

"Hush!" commanded Dan, for they were drawing near.

Very likely Billy's words had reached the captain's ear. He glanced over his shoulder, saw the Speedwells, and scowled. Dan put on the brake as he wheeled down to Avery.

"What's happened, Avery?" he asked pleasantly enough. "Can we help?"

Chance was pumping up his rear tire. The contents of his tool- kit were scattered about and it was evident that he had suffered more than a puncture. At least, when he spoke, it was very evident that he had fractured his temper—a compound fracture at that!

"I don't need any of your help," Chance said, sourly. "You'd better plug along if you expect to get to Barnegat to-night."

Billy flamed up at this and before Dan could reply to this ungracious rejoinder, the younger Speedwell cried:

"Let him alone, Dan! I wouldn't help him if he had to take shank's mare clear back to Riverdale. And I hope he does!"

"You needn't bother. I'll pass you before you get far beyond the railroad crossing, youngsters," snarled the captain.

The brothers, although they had reduced speed, had not stopped. Now both put on weight and pushed up the short rise beyond the hollow.

"Did you ever see such a bear?" demanded Billy.

"He's sore that we should be the ones to overtake him. It's a great joke on him after the pace he set," admitted Dan.

"I'm tickled half to death," said the younger boy. "Hello! there's the grade crossing."

The Barnegat & Montrose Branch of the R. V. & D. Railroad crossed the highway at the foot of this second steep slope which they now descended. The hill was not high, but it was precipitous and there were bad curves in the railroad line on either side of the highway. After several accidents had happened the railroad company had placed a flagman at this crossing.

His little shanty was only revealed to Dan and Billy when they were more than half way down the slope; but the man himself was not in sight. It was naturally to be inferred that no train was due at the crossing at this hour.

And not seeing the flagman, the boys would have shot past the shanty after crossing the rails had it not been for Dan's quick eye. Chance Avery was not in sight. There was a sharp turn in the highway as well as in the railroad, and if he had started down the slope he could not see the crossing until he was a few yards from it.

Dan looked around to see if Chance were coming. His view of the interior of the flagman's hut was better than Billy's. He saw the man sprawled flat upon his face upon the floor, one arm bent under him in so uncomfortable a position that it was impossible to suppose him sleeping!

"Billy! Wait!" called Dan, and stopped his own wheel and leaped off at once.

His brother heard and looked back. He saw Dan run into the little shanty. The next instant Billy heard his brother utter a shout, and then he ran out with a flag in his hand, which he waved wildly.