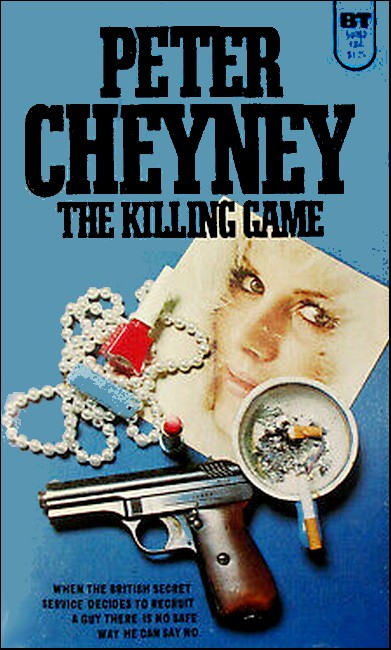

RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

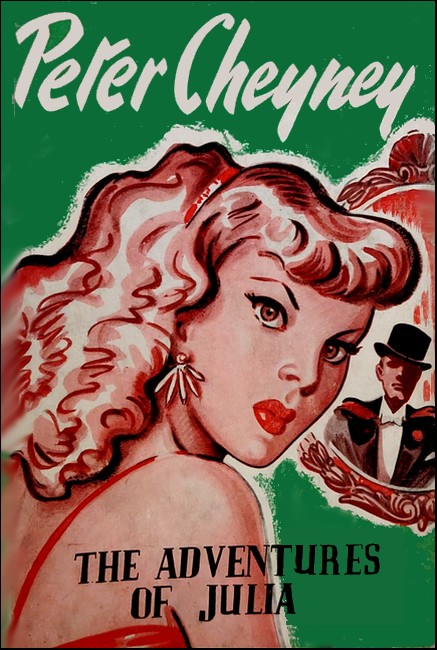

"The Adventures of Julia," Todd Publishing Co., London, 1954

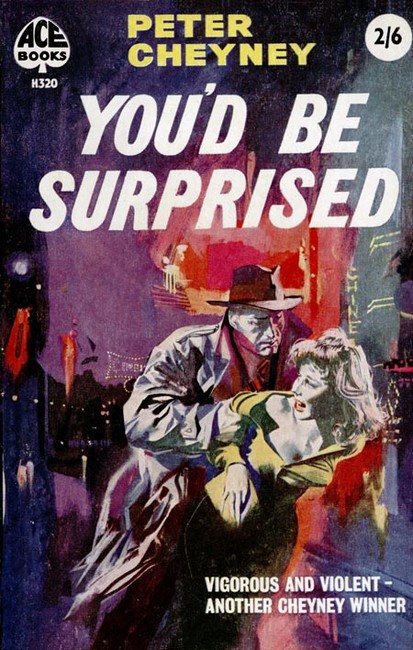

"You'd Be Surprised," Ace Books H320, 1959

THE little clock on the mantelpiece struck seven. I switched on the electric light and looked at myself in the pier glass. I thought: Well, Julia, even if it is war time, and even if the Splendide is full of war correspondents, I don't see why you shouldn't make the best of yourself. After all, even a war correspondent has to take his mind off his work sometimes.

When I went down into the lounge, I thought I looked rather nice. I had on a sleek tailored coat and skirt of watered moiré silk, sheer beige silk stockings, and rather neat black glacé court shoes with tiny diamond buckles. My coat was caught at the waist with a small diamond link, and underneath was a duck-egg blue chiffon blouse. I wore one very good bracelet that looked like diamonds—even if it wasn't—two or three effective rings, and a charming expression with just a slight touch of hauteur.

Perhaps at this stage of the game you ought to know that I am thirty-five years of age. I have Titian red hair, my figure is considered to be good, and I have medals for knowing my way about. And if you want any further information you won't get it. All this is leading up to the fact that I was feeling rather unhappy.

About this business of being unhappy; you know, mes enfants, just as well as I do, that there are only three sorts of trouble that ever come to any man or woman—health, money, and love. Well, my health is very good and I have—up to now—always taken a very dim view of falling in love. That leaves you one guess and you'd be right—it was money!

Five minutes' intense calculation in the sanctity of my bedroom earlier in the afternoon had shown me that my existing capital would see me through at the Hotel Splendide for about two weeks, providing I double-crossed every waiter and page-boy in the place, did my own hair, and closed my eyes every time I passed the flower shop.

SO now you know exactly what the position was. I found a

comfortable armchair in the lounge and proceeded to do a little

quiet thinking. I had to formulate some plan of campaign,

but you can take it from me that formulating a plan of campaign

in these days is no easy proposition.

Then somebody said 'Hello!'

It was a man. I took a quick look at him. I didn't like him very much. He was well-dressed and had assurance and that was about all there was to him.

He sat down in the chair opposite me. He said: 'Well, and how is Miss Heron?'

I said: 'Thank you for the enquiry, sir, but I don't think I know you.'

He smiled—a rather cruel smile it was. He said: 'You don't know me, but I expect you remember me. Cast your mind back to a little trouble with a bad-tempered waiter in a night club in the Rua Garret in Lisbon last year. I was the one who dealt with him. Remember now?'

I said: 'I see. So that was you, was it?'

'That was me,' he said. 'Would you mind if I cut out all the frills and get down to hard tacks?'

'I don't know what you're talking about,' I told him. 'I don't know what you mean by cutting out the frills. What frills, and what hard tacks?'

'I'll tell you,' he said. 'You see, I happen to know all about you. You arrived in this country five days ago. You're staying at this hotel, and I think your finances are in a not very good condition. Right?'

'I don't see why I should answer questions,' I said. 'But even if your guesses are right, I don't see what any of this has to do with you.'

'You will,' he said, airily, and I disliked him more than ever. He went on: 'I don't know if you've read the evening papers, but if you have you may have seen something about some airplane plans having been left in a Service car by a rather careless official. Well, that's not quite true. Those plans were stolen. The gentleman who has them at the moment is somebody whom I think you once knew. His name's Valtazzi. He used to be a croupier in one of the gaming houses in Lisbon.'

'I remember the name,' I said, 'but I fail to see what airplane plans and Mr. Valtazzi have to do with me.'

'Be patient,' he said. He continued: 'Valtazzi's got those plans. He's been snooping around this country for about four months. He's working with another man—Wolfgang—a German, posing as a Swede, a very clever fellow, who's living somewhere in the country. Having got the plans, Valtazzi, who is getting a little frightened of the situation, wants to get rid of them and get out. But he can't very well sell them to his own chief without using somebody else. I happen to know that he's looking for an intermediary—someone who is not, shall we say, too scrupulous.'

'Meaning me?' I said.

'Meaning you,' he repeated.

I didn't say anything.

He went on: 'We have a man working in close touch with Valtazzi. Of course, Valtazzi doesn't know this individual is in our employ, so it's going to be very easy for us to suggest, through this contact, that you are here in England and are rather up against it. If I'm not very much mistaken, Valtazzi will get in touch with you and suggest that you do a deal with his boss over the plans.'

I said: 'All this is no doubt very interesting and very exciting, but I don't see what it has to do with me and I don't know that I want anything to do with it. Incidentally, who are you and what are you?'

He smiled. It was a rather self-satisfied sort of smile. He said: 'Possibly you've heard of the Secret Service. Well, you know, it does exist. And I think that you'll be quite prepared to help over this little business.'

'Do you?' I asked. 'Why?'

'For several reasons,' he said. 'You know, there are one or two little incidents in your past which you might not like to have raked up—that little affair, for instance, at Juan les Pins.'

I sighed. 'I see,' I murmured. 'So this is a sort of blackmail?'

'If you like,' he said. 'My advice to you is to render me the assistance I require, in which case you will also be doing your country a service, and in which case I shall be quite happy to keep my mouth closed about the Juan les Pins business.'

I sighed again. I said: 'It doesn't look as if I have very much choice, does it?'

He said: 'No, you haven't really. You'd much better play ball.'

'Very well,' I said. 'If it's like that, I'll play ball, although I must say I don't like your methods. But I should like to know that you do work for the Secret Service. I should like to know something about you.'

He produced a card from his waistcoat pocket. He gave it to me. He said:

'If you like to enquire at the Department in Whitehall on that card, they'll tell you all about me. They'll probably tell you that it will be much healthier for you to do what I want you lo do.'

I said: 'All right. You win. What is it you want me to do?'

'It's very simple,' he said. 'We'll get our man to let Valtazzi know that you're here and to suggest you're the person for this job. We've rather an idea that Valtazzi will want to get this business finished some time next week. He'll do it then because he's about to leave the country. He's got an exit permit. My guess is he'll get in touch with you. He'll ask you to deliver those plans to his associate and take the money. He'll probably pay you a small rake-off.'

I nodded. 'And what do I do?' I asked.

'If he does that,' he said, 'you'll take the plans. He'll probably have an appointment made for you to hand them over. You hand them over, but you'll let me know when and where in advance, so that we'll get the plans and Valtazzi's associate. After which, when you return to Valtazzi to hand over the money, we'll get him too. It's all very simple, isn't it?'

I said: 'Yes. The way you say it, it sounds quite simple.'

He got up. He said: 'Well, I'll be seeing you. I should think Valtazzi would get in touch with you here within a few days.'

The smile disappeared from his face. He looked a trifle grim. He said: 'And don't try any funny business. You've got a reputation for being an extremely clever woman. You'll find it won't pay to be clever with me.'

I looked at him. 'You're quite delightful,' I said, 'aren't you? But you make me feel terribly tired.'

He said: 'That's as maybe, but I always get results.'

'It must be awfully nice to be you,' I said.

He turned on that funny little cynical smile of his and went away. I sat down and ordered another cocktail. I needed it.

WHEN I went in, the man who was sitting behind the big desk in

the Whitehall Office gave me a very long, curious look; then he

smiled. I thought he looked rather nice. He was thin, very

experienced-looking, and had well-developed 'humour' lines at the

sides of his eyes.

He said: 'Well, Miss Heron, it's nice to see you. Won't you sit down? My name is Forrester.'

I said: 'Thank you,' and sat down. I said: 'I'm glad to know it's nice to see me, Mr. Forrester. I came here because last night, at the Splendide, a Mr. Vazey, who says he's a Secret Service agent, put a proposition up to me. I wanted to know that it was bona fide.'

He smiled. He said: 'You don't sound as if you liked Vazey very much.'

'I didn't,' I said, 'not one little bit.'

'A lot of people feel like that about him,' he went on. 'He's inclined to be tough, but he's quite good. He gets results.' He smiled again delightfully.

'Well, he's got results with me all right,' I said. 'He's practically blackmailed me into working for the Secret Service whether I want to or not.'

He grinned. 'Too bad,' he said.

'There's just one other little point,' I went on. 'If I remember rightly, when I read that paragraph in the Evening News last night about those plans being missing, it said something about the Government having offered two hundred and fifty pounds reward. If I help in retrieving them, don't I get the two hundred and fifty pounds?'

'I'm afraid not,' he said.

'That's not so good,' I went on. 'So I have to work for nothing. In other words, that piece about the two hundred and fifty pounds reward is all nonsense.'

'Oh no,' he said. 'We should have paid that reward if someone had found the plans and brought them in. Naturally, we only pay a reward when we must. You see, we know where those plans are. We know Valtazzi has them.'

I got up. 'It looks as if I'm wasting my time,' I said. 'Anyhow. This will be a lesson to me. I never believed all those funny things I've read in books and seen on the films about the Secret Service. I'll know better next time.'

He got up. He said: 'Tell me something, just how did Vazey get you to do this? He's told me all about it, except for one thing. What had he got on you?'

I shrugged my shoulders. 'Some little incident a long time ago at Juan les Pins,' I said. 'Really, I had nothing to do with it, but I'd find it very difficult to make that plain. You understand?'

He said: 'I understand.'

I said: 'You're quite certain about my not being able to get this two hundred and fifty pounds for helping to get those plans back, Mr. Forrester?'

He said: 'I'm fearfully sorry, but I'm afraid it's not possible. As I told you, we only pay rewards like that when we're forced to.'

'I see,' I said. 'Well, it looks as if I've been taken for a ride this time, doesn't it?'

I picked up my fur. I said good-bye.

I went out of the office. When I was being shown along the corridor, I thought to myself that these Secret Service men were really tough. And very clever. What chance has a simple girl got anyway?

VALTAZZI phoned me at the Splendide the next evening and

turned up half an hour afterwards. I remembered him directly I

saw him. He used to be a croupier in Lisbon. He was a

slim, too-well-dressed man, with quite charming manners.

We had a cocktail and he got down to hard tacks. He said:

'A little bird has told me that you're in rather a spot—that you need money. Well, perhaps I can be of help to you. Possibly you can be of help to me. Let us see.'

I said: 'You're quite right, Mr. Valtazzi. I do need money. I'm willing to do practically anything to get some—anything that's quite nice, I mean.'

He smiled. He said: 'What I want done is awfully nice. All I desire you to do is deliver a packet of confidential documents to a colleague of mine in the country which, for reasons which do not matter, it would be inconvenient for me to deliver personally. In return for the documents, you will be given two thousand pounds. You will bring the two thousand pounds back to me at my flat and I will give you five hundred pounds. How do you like that?'

He sat back in his chair smiling at me amiably. I noticed that the fingers that held his cigarette were trembling a little. It struck me that Valtazzi was scared.

I said: 'What's the funny business, Valtazzi?'

'Nothing very much,' he said. 'Just one of those things.'

I said: 'Now you listen to me. I need some money badly. I want that five hundred pounds and I'll deliver the documents. That's all right. I won't even ask any questions about what they are. By the way, what nationality are you supposed to be in this country?'

He said softly: 'I'm a Swiss.'

'Like hell you are,' I told him. 'Anyhow, never mind. I'll do it. But I think you'd be awfully well advised to let me have two hundred and fifty pounds now—if you have it.'

He showed his teeth in a very pleasant smile. He said: 'My very charming and delightful Miss Heron, why should you think that I walk about with two hundred and fifty pounds in my pocket?'

'For a very excellent reason, Valtazzi,' I told him. 'You're scared. You want to get out of this country as quickly as you can, and if I know anything you're carrying your bank roll with you.'

His smiled disappeared. He said: 'Why should I be scared?'

I smiled. I said: 'I'll tell you. They're wise to you, Valtazzi! The Secret Service are waiting for you. Never mind how I know. I know that you're Italian. I know that you've got the airplane plans that were stolen recently from a Service car. Well, that's all right with me. Quite candidly, the Secret Service in this country have been very tough with me. They've taken me for a ride.'

His eyes brightened. He said: 'Ha! ha! So you're going to sell them out?'

'I'm going to sell them out. And if you like to hand me two hundred and fifty pounds, I'll tell you just how I propose to do it.'

He said: 'You know, Miss Heron, always I have heard how clever and brilliant and courageous you are. You know everything.' He took out his wallet and took out five fifty-pound notes. I could see there was only one fifty-pound note left in the wallet, and I realized that Valtazzi needed money too. He handed me the notes.

'Now, my charming and beautiful lady, perhaps you'll do a little talking,' he said.

'I'll do this much talking, Valtazzi,' I told him. 'This is the idea. They have an idea that you're going to get those plans delivered and sold to your friend in the country. They're waiting for you. But they think you're going to do it in a few days' time. You see the idea?'

He said: 'I don't quite see.'

I said: 'Let's get the job done tonight. Let's take them for a ride.'

He said: 'You'll do it?' His eyes were very bright.

'You bet I'll do it,' I said. 'If I do it tonight I can meet you first thing in the morning, hand over the money, take my additional two hundred and fifty, and you'll have a chance to make a getaway.' I gave him another sweet smile.

'You'd better make up your mind quickly,' I said. 'There's no time to be lost.'

He said: 'My mind's made up. I'm going straight back to my flat. I'll bring those plans in a sealed envelope and hand them over to you in twenty minutes' time. Can you get a hired car?'

'Quite easily,' I told him.

'Very well,' he said. 'You drive down to Woking. You must arrange to get there at nine-thirty. My colleague will be advised that you are arriving at exactly that time. The house is on the main road three-quarters of a mile past the station. It's called Mallowby Lodge. Don't go in by the front door. Go round to the back, across the lawn and through the french windows. My friend will be waiting for you at exactly nine-thirty. Will you time yourself to arrive there at that time exactly?'

'Absolutely,' I said.

He went away. He looked very pleased with himself. Why shouldn't he?

AT half past eight I called through to the Whitehall Office

and spoke to my unpleasant Secret Service friend, Mr. Vazey. Even

his voice sounded tough. I thought it wasn't nearly as pleasant

as that of his chief.

I said: 'Listen carefully, Valtazzi's fallen for it hook, line and sinker. I've got the plans and I'm just leaving to deliver them. I'm going to Mallowby Lodge, three quarters of a mile from Woking Station. I have to be there exactly at nine-thirty, at which time I shall be let in through the french windows facing the lawn at the back of the house.'

He said: 'Fine!' He sounded very satisfied. 'We'll be there,' he went on.

'Just a moment,' I said. 'You don't want to be there too soon. You'll have to give me time to hand the documents over, won't you? The best thing for you to do is to conceal yourself somewhere at the back of the house and give me at least ten minutes to get the talking done. I suggest you come through the french windows at twenty minutes to ten. Then you'll have him with the goods.'

'You're quite right,' he said. 'We should have done that anyway. You be there at nine-thirty sharp and we'll be with you ten minutes after that.' His voice became very sinister. 'And see you go through with this on time. Remember, I can he very unpleasant.'

'About what?' I asked.

'About that business at Juan les Pins,' he said.

I sighed. I said: 'I wish I knew whether you were bluffing or not.'

'I'm not bluffing,' he said. 'You do your stuff and you'll be all right.'

I heard the receiver click back. I liked him less than ever.

IT was nine-thirty when I tapped very softly on the french

windows at the back of the house at Woking. Almost immediately

the windows opened and I slipped through the curtain into the

room. Mr. Wolfgang seemed very pleased to see me.

Then, exactly at twenty minutes to ten, the french windows were burst open and my Secret Service friend, Mr. Vazey, accompanied by two very large gentlemen, interrupted my conversation with my host.

Vazey said: 'Nice work!' He looked at me approvingly. 'You notice we kept to our schedule, Miss Heron, and I'm glad you kept to yours.'

'It's very nice to have your approval, I'm sure,' I said.

I need not say that Mr. Wolfgang was extremely annoyed, but his splutterings were cut short by Vazey, who, after telling him what sounded like a few straight truths in German, had him taken away by the two satellites. Then he stood in front of the fireplace, the large envelope which I had handed over in his hand, looking particularly self-satisfied. He said:

'Well, that's that. We've got the plans and we've got Wolfgang. Now the only thing that remains is for you to take us back to Valtazzi's address and we'll collect him. A very nice little bag.'

I nodded. 'You're doing fearfully well, aren't you?' I said.

He smiled. It was a self-satisfied smile. 'Not too badly,' he said.

He slit the envelope with his thumb; drew out the documents inside. He looked at them for a moment; then he muttered a very rude word under his breath. He said:

'So you've double-crossed us?' He stood glaring at me, the envelope in one hand and some carefully folded copies of the Evening News wrapped up in cartridge-paper in the other.

I said: 'Really, Mr. Vazey, I don't know what you're talking about.'

'Don't you?' he said. He held out the packet towards me. 'Look at this,' he said. 'That's the envelope you brought down here—copies of the Evening News! There's only one explanation to that. You sold us out to Valtazzi. Well, didn't you?'

I said nonchalantly: 'Well, I must admit that I told Valtazzi that the Secret Service was very interested in him, but I wasn't to know that he was going to switch those papers, was I? It looks as if he's been a little too smart for you.'

'It won't do him any good,' he said nastily, 'and it won't do you any good. This makes you an accomplice of Valtazzi's. Where's he living? I expect you've got an appointment to see him tonight.'

I said airily: 'I don't know that I want to discuss this with you. You bore me. Your footling little plans came unstuck, after which, without a moment's hesitation you blame me for everything.'

He said: 'This is going to be very tough for you before it's finished. So I bore you, do I? All right. You're coming back to town with me and you can do some explaining to someone else. Perhaps you won't feel so bored then.'

'That suits me very well,' I said. 'I'm rather particular to whom I do my explaining.'

WHEN we arrived at Whitehall, he took me straight to the

office of his chief.

He said: 'We've been done in the eye, sir, and Miss Heron is behind it. The envelope she took down to Wolfgang contained a few old copies of the Evening News wrapped in some cartridge-paper. Here they are. She's admitted that she discussed this matter with Valtazzi; that she told him that we were after him.'

Mr. Forrester raised his eyebrows. He said: 'You don't really mean to say you told Valtazzi. I can hardly believe you'd do a thing like that.'

I said to him: 'Listen, Mr. Forrester. Someone has to have some sense, and your Mr. Vazey here seems a little deficient. When Valtazzi came to see me he was scared stiff. Directly I saw him I thought it would be very dangerous to wait any length of time before getting him to go through with this deal. He was so frightened he might have done anything. So I conceived it my duty to tell him something that would make him get a move on, and the only thing I could tell him was that he was under observation and that he'd better move quickly. I told him that.'

Forrester said: 'And do you think he believed you? You had no right to do that. You've seen the result. He's still got those plans. He's thrown us off the track and has probably moved his address. It's not going to be easy to find him now.'

'That's as maybe,' I said. 'But I think you ought to know that he hasn't got the plans.'

Forrester raised his rather nice eyebrows. He said: 'What exactly do you mean?'

'I've got them,' I told him. 'I switched the plans over. Valtazzi gave me the real plans all right. I took them out and put those copies of the Evening News in their place. I thought it would be a good idea.'

I heard Vazey say under his breath: 'Well, I'll be damned!'

Forrester said: 'Why did you think it would be a good idea?'

I smiled at him sweetly. 'I was thinking of that two hundred and fifty pounds reward,' I said. 'You remember you told me that you wouldn't pay it unless you must. Well, now you've got to.'

Vazey said: 'Are you going to stand for this?'

Forrester waved him aside. He said: 'Just a minute Vazey. There's no need to be tough.' He turned to me. 'Supposing I give you the reward of two hundred and fifty pounds,' he said. 'That doesn't alter the fact that you've laid yourself open to arrest. This might be a very serious business for you.'

'Not at all,' I said. 'It's not going to be serious for me in the slightest degree, Mr. Forrester. But it's going to be very serious for you if you don't give me that reward, because if you don't I shan't tell you where those plans are, and then you can do what you like.'

He sighed. 'You're a very hard case, aren't you, Miss Heron?' he said. 'Well, if you want it that way I'll make this bargain with you. I give you my word that you shall be paid the two hundred and fifty pounds reward tomorrow morning providing you tell me where those plans are. After we have them in our possession, you will realise that Mr. Vazey here will probably insist that some action be taken against you.'

I smiled sweetly at him. 'What Mr. Vazey insists on doesn't matter one hoot to me,' I said. 'It won't get him anywhere. Do I take it I have your word that I get the two hundred and fifty pounds?'

He nodded. 'I shall arrange that it is paid to you first thing in the morning,' he said. He smiled. 'Incidentally,' he said a little cynically, 'I suppose Valtazzi also gave you something for services rendered?'

'Quite right,' I said brightly. 'He gave me two hundred and fifty pounds.'

Vazey made an angry noise. He said: 'Some girl, isn't she?'

Forrester said: 'It's no good arguing, Vazey. All right, Miss Heron, you're going to get your two hundred and fifty and take what's coming to you afterwards. Now then, where are those plans?'

'They're awfully safe,' I said. 'They're in the custody of His Majesty King George Sixth—or, rather, of His Royal Mail. You see, I forgot to tell you that when I took those plans out of their original envelope and substituted the Evening News for them, I put them into another envelope, sealed it, stamped it, and addressed it to you here at this office, which I consider to be the duty of a patriotic citizen. I wasn't taking any chances of losing those plans.'

Forrester began to grin, I took a sideways look at Vazey. He was looking like death.

'Just what charge you're bringing against me,' I demanded, 'for doing what I consider to be my duty, is a question which I should very much like answered.'

Forrester said: 'You know, Miss Heron, you really are rather bright, aren't you? I take it that those plans will arrive here by first post in the morning.'

'That's right,' I said. 'And I shall be calling round about eleven o'clock for the two hundred and fifty pounds reward.'

He said: 'Do you know, I shall be very glad to pay it to you,' He looked at Vazey. He said: 'It's all right, Vazey. I don't think I need you any more.'

Vazey went out. As he got to the door I gave him a charming smile.

I said: 'Good night, Mr. Vazey.'

He threw me a dirty look and went away.

Forrester said: 'You know, Miss Heron, I think you might be very useful to us.'

'I thought that, too, Mr. Forrester,' I told him. 'I thought possibly you might be able to find me a job.'

'I think we shall be able to do that,' he said. 'Candidly, I rather admire the way you've handled this business. You've done pretty well financially out of it, too. You've got two hundred and fifty from Valtazzi and two hundred and fifty which you will get from me. That's not too bad.'

'I don't think it was either,' I said. 'By the way, you might like to know that Valtazzi is expecting me at his flat and that if you send the bad-tempered Mr. Vazey round he'd probably get him.'

He grinned. 'Good girl,' he said.

He picked up the telephone and gave some instructions. Then he said: 'I think you and I ought to lunch tomorrow and talk things over. I'll pick you up at one o'clock.'

'Could you make it the day after? I've got quite a few clothes coupons, and I'd like to buy some clothes. I think a little shopping tomorrow would put me in the right frame of mind for lunch with you the day after.'

He said: 'All right. But I'll see you in the morning, when you come for that two hundred and fifty pounds. I suppose you're going to make a hole in that five hundred.'

'Something like that,' I said. At the doorway I stopped and smiled sweetly.

'It isn't five hundred,' I said. 'Its two thousand five hundred. You see, I got the two thousand from Wolfgang before I consented to hand over the package. That's why I asked Mr. Vazey to arrive ten minutes after I did.'

He said: 'Well, I'll be damned!'

'You will be if you aren't more careful in the future,' I told him. 'What you want is a really sensible woman round here to advise you. Au revoir, Mr. Forrester.'

I DON'T know whether you believe in feminine intuition, my pets, but whether you do or you don't does not alter the fact that there comes a time in a girl's life when she definitely feels certain about one thing and that is she is looking really rather nice, very well-dressed and altogether on top of the world. I expect most of you have felt like that at some time of other, and if you haven't you ought to see someone about it because life isn't giving you the right sort of tumble. Do you get me?

What I'm trying to tell you is that my intuition at the moment under consideration, told me that I'd never look any better than I did then. Figure to yourselves, mes enfants; I was wearing a brown cord velvet coat and skirt, under a beaver coat, beige stockings, rather well-cut brown court shoes, a smart little beaver hat to match the coat and a duck-egg blue georgette blouse that was definitely pre-war and so precious to me that I felt I ought to keep it in a safe deposit.

Sitting back in the corner of a very comfortable back seat of the Daimler limousine that had met me at Sellington Station, I came to the conclusion that this was really the most interesting job I'd had since I'd been bluffed into working for the Secret Service by the not-so-nice Mr. Vazey.

I opened my handbag and took out the letter of instructions that I'd been handed that morning, it read:

You will please take the eleven o'clock train today from Euston for Sellington. You will be met at that station by a Daimler car and driven to Tulse Hall which is about six miles from the station. You are supposed to be Miss Janet Fleur, a friend of the sister of the owner of Tulse Hall (a Major Fells) whom you have not previously met but who knows all about this business. The idea is that you are going there to spend a few days at his invitation. You will find half a dozen other guests there.

The situation with which you have to deal is as follows: Last Saturday a military officer of high rank left some important documents in a brown leather attaché case in his car outside Sellington Station. Before entering the station he locked the car. There was no one but this officer, and the two porters on duty, on the station platform. A few minutes afterwards the three-thirty train from London arrived and disgorged six people—all of whom were guests on their way to Tulse Hall—who went through the barrier.

There was a slight fog at the time and so when one of the porters on duty outside the station saw someone open the car door and take out the brown leather bag he naturally thought it was the officer who had been driving the car. It was not. The officer was still on the platform.

My operatives have checked very carefully on the situation and it is quite obvious to us that the documents in the brown leather case—documents of the greatest value to the war effort—were stolen by one of the people who were en route for Tulse Hall. As none of these people has left the Hall since, he or she and the documents are still there, believing, I imagine, that the coup has been successful.

It is essential that the loss of the documents should not be made public, and your business is to find out (perhaps your womanly intuition will help!) which of these people has the documents, to get them back, and secure the arrest of the thief, who is quite obviously in the pay of the enemy.

Chief-Inspector Vayle at Nunning Police Station has instructions to give you any police assistance you may require (telephone number Nunning 42) and—although you may not be too happy about this—Mr. Vazey will be staying at the Rockley Arms in Tulse village. He will keep an eye on things generally and advise you if you want advice.

My best wishes. I hope you feel as well as you looked when I saw you last. And take care of yourself!

Yours ever,

Hubert Forrester.

P.S.—Destroy this, please, when read. H.F.

I read the letter through once again, lit the corner of it

with my lighter and dropped the ashes out of the window. This, I

thought, is going to be really exciting, in spite of the fact

that my bête noire—Vazey—was going to be

hanging about the place sticking his long nose into everything!

Still ... I suppose that Mr. Forrester thought that there ought

to be some sort of a man around. I've told you before, of

course, that Mr. Forrester is really rather a sweet and

definitely my cup of tea—that is, if I ever thought about

'cups of tea' seriously ... if you know what I mean ...

It suddenly occurred to me that I seemed to be spending quite a little of my time thinking about Mr. Forrester, but in any event my ruminations on this subject were brought to an end by our arrival at Tulse Hall. The Hall—an old-fashioned manor house set back in its own grounds at the end of a carriage drive presented a romantic picture. This, I thought, is going to be in the setting of your latest adventure, little Julia, and I hope it's going to be as successful, or as lucky, as the others have been.

My host, Major Fells, met me at the top of the stone steps. He whispered: 'I'm very glad to see you, Miss Heron. Although from now on you're going to be Miss Fleur. And I wish you the best of luck.'

I said: 'Thank you very much, Major. I suppose you haven't the faintest idea...?'

He shrugged his shoulders. 'I haven't the remotest idea,' he said. 'I don't know these people very well, but I know something about each of them. I've been puzzling my brains to try and come to a conclusion, but I can't do it. You'll have to use that feminine intuition of yours.' He led the way into the Hall.

Upstairs in my room I began to think about this intuition business. Everybody seemed to be talking to me about my intuition. I hoped I had some. And I hoped it was going to work.

AT eight o'clock, when the first gong went, wearing my most

attractive black dinner frock, I went down to the lounge. The

guests were all gathered there and over a cocktail I had the

chance of inspecting them. Besides my host and myself there were

four women and two men. They looked very nice—very

innocent. Looking from one to the other I wondered which of these

people had had the nerve and brain to get away with this

business, but I could find no answer. In any event, I thought,

whichever one of them it was, must have known something about the

neighbourhood; must have known that the officer was in the habit

of arriving to meet that Saturday train and having the document

case in his care. It occurred to me that it might be a good idea

to try and find out which of these people had been to the village

before or knew the country. That might narrow it down.

I smiled to myself. As my intuition was not doing so well I would endeavour to solve the problem by logic—the male method. So, after dinner, in the privacy of my room, I made a list of the six suspects:

(1) Mrs. Vandeler—about forty-five years of age, plump and charming; a characteristic type of English matron. I wondered if she could be a spy. I didn't think so.

(2) Mr. Charleston—about thirty-five years of age, well set up, with a rather fierce moustache. I thought he was rather nice. I couldn't find it in my heart to suspect him.

(3) Miss Glynn—a rather ascetic-looking spinster of an unknown age. During dinner she had regarded me with vague disapproval. She didn't look as if she could steal anything, but one never knows.

(4) Mr. Farrell. Everybody called him Jack. About forty—with a merry twinkle in his eye. I caught him looking sideways at me on two or three occasions during dinner. He looked very clever and apparently knows this part of the world.

(5) Miss Vavasour—a very good-looking young woman of about twenty-eight, so good-looking that I found myself becoming a little jealous of her. Has wonderful clothes and knows how to wear them. I thought Miss Vavasour might easily be a spy. She might easily be a thief. Or was I merely being jealous? Even intuition can slip up sometimes!

(6) Mrs. Phelps—a lady of rather uncertain age—anything between forty-five and fifty-five; obviously very fond of her food, and I think rather lazy. Somehow I didn't feel that she could summon up enough energy to do any serious stealing.

I read through my list, but it didn't do me any good. It

wasn't getting anywhere. Perhaps I wasn't as clever as Mr.

Forrester thought. The intuition wasn't even trying to work.

I began to think of Mr. Vazey. I could imagine the sarcastic smile that would appear on his face when he was told that I'd slipped on the job, that is if I was going to slip up.

I came to the conclusion that thinking was going to get nowhere at all. So I went to bed and slept the sleep of the innocent.

THE next morning was quite lovely. Looking round the breakfast

table, I felt a little happier. I felt that sooner or later one

of the six would have to give himself or herself away. I was

continuing with this line of thought when the butler came in and

told me that a Mr. Blake wanted me on the telephone. I didn't

know a Mr. Blake, but I had a pretty good idea who it was going

to be.

I looked round the hall before answering the 'phone. I was alone. The place was quite deserted. I said: 'Hello!'

A voice which I immediately recognised as Mr. Vazey's said: 'Is that Miss Fleur?'

I said: 'Yes, it is. How do you do? I thought I should be hearing from you.'

He said: 'I rang up to find out if you've discovered anything. Perhaps it's not so easy as you thought it was going to be. Perhaps the intuition isn't working as well as Mr. Forrester thought.'

'Its nice of you to be so sarcastic,' I said, 'but you know, intuition doesn't work to order.'

He said: 'I see. So you think it's going to work?'

I said casually: 'I haven't the slightest doubt.'

He said: 'Very well. As you know, I'm staying in the village. Possibly the intuition may have worked by this afternoon. In any event perhaps you might meet me under the second oak tree on the small dirt road that leads towards Marshley. I'll be waiting there for you at seven o'clock.'

'Very well,' I said. 'I'll be there.'

He said: 'And I hope you have something to report.'

I said brightly: 'I hope so too. If not, it's going to be too bad, isn't it?' I hung up before he had a chance to say anything else.

Definitely, as I have told you before, my pets, I do not like Mr. Vazey.

AFTER lunch I went for a walk in the flower garden. I thought

I'd really give the intuition a chance. I just meandered about

and smoked a cigarette and wondered about the six guests at Tulse

Hall, one of whom was an enemy agent. But which one? At my

present rate of progress no one would ever know! Definitely,

something had to be done.

I began to think about the four women—Mrs. Vandeler, Miss Glynn, Miss Vavasour and Mrs. Phelps. Of those four people, if one was the thief, I thought it would probably be Miss Vavasour. But, mes enfants, I must confess that I suspected that it was probably a little jealousy and not intuition that guided my ideas in this direction.

I wondered which of these four ladies—supposing one of them had stolen the document case—had sufficient brains, nerve and courage to get away with it. She would have to be a clever woman—a woman who could make up her mind quickly and act quickly. A woman who could keep her mouth shut....

Suddenly I had an idea. Which of these people, if any, couldn't keep their mouths shut? That wasn't too difficult. I thought I knew the answer to that one. Mrs. Vandeler was definitely a chatterbox and so was Miss Glynn. It hadn't taken me very long to realise that. Very well then, supposing...!

I threw my cigarette-end away and walked quickly back towards the house. I'd made up my mind. I was going to take a chance. If it came off all well and good, but if it didn't! Phew.... I wonder what Mr. Vazey would have to say about it.

AT three o'clock I ran Mrs. Vandeler to earth in the drawing

room. She was sitting in front of the fire knitting a sock that

looked as if it was intended for an elephant.

I looked over my shoulder in a conspiratorial manner and then sat down beside her.

I said: 'Listen, Mrs. Vandeler. Directly I met you I realised that you were a most patriotic type of Englishwoman. I feel I can confide in you. I must begin by telling you that I am a Secret Service agent!'

Mrs. Vandeler dropped the sock in the grate and very nearly fainted with surprise. When she had recovered from the shock she registered intense interest and almost trembled with joy at being let into the great secret.

I told her the whole story. I entreated her to assist me. I said I couldn't get on without her. Thrilled to the marrow, she promised to do anything short of murder to bring the enemy to book.

'The thief is one of the six guests here, Mrs. Vandeler,' I said. 'Obviously it isn't you, so that leaves five. I'm quite certain that it isn't Mr. Charleston or Mr. Farrell, so I want you to tell those two about it in the strictest confidence. I will deal with the other three. Will you do that?'

Mrs. Vandeler promised. I knew that immediately I left her she would dash off and tell the story—probably with some dramatic additions—to the Charleston and Farrell birds.

She said: 'Miss Fleur, I've always wanted to help catch a spy. I think this is marvellous!'

I told her I thought so too. Then I went off and searched around the place until I found Miss Glynn. I caught her in the act of replacing a bottle of Kummel on the sideboard in the dining-room. I'd noticed she was very fond of Kummel.

I said: 'Hist... Miss Glynn!' and took her into a corner. Then I told her exactly the same tale as I'd told the Vandeler, except that I said I didn't suspect Miss Vavasour or Mrs. Phelps, and that she could tell them. She promised she would—after she'd recovered from the shock.

I went to my room and smoked a cigarette. If I knew anything of Mrs. Vandeler and Miss Glynn the atmosphere of Tulse Hall would be positively reeking of suspicion within a few hours.

Which was precisely what I wanted.

AT six-forty-five I went off to meet Mr. Vazey. It was quite a

nice evening and I tripped along, carrying the brown document

case that I had borrowed from Major Fells, as if I hadn't a care

in the world.

Mr. Vazey was standing under his oak tree looking glum. I said: 'Good evening, Mr. Vazey. It seems that you and I are always meeting under trees. One day, perhaps, we'll meet somewhere where it's really interesting.'

He said: 'I don't think this is a time for joking, Miss Heron. Have you anything to report?'

'Oh yes,' I said brightly. 'I know the culprit—at least I shall know at eight-thirty tonight. That's why I want you to be there.'

He brightened a little bit. 'Well... I hope you're right,' he said. 'I hope you haven't made a mess of this and got the wrong person.'

'That's nice of you,' I said. 'Incidentally, I haven't been too unsuccessful on previous occasions, have I?'

He relapsed into gloom again. 'That was possibly luck,' he said. 'And exactly what is going to happen at eight-thirty at Tulse Hall?'

'I shall have the thief all ready for you,' I said. 'And you can carry on from there. Now... if you haven't anything else to say I'll be on my way. I've a lot to do. And I shall see you at eight-thirty?'

'I'll be there,' he said. Then he thought of something. 'By the way, Miss Heron,' he went on, 'I hope you haven't relied entirely on your intuition in this business?' He grinned at me sarcastically.

'Don't worry about my intuition, Mr. Vazey,' I said. 'It's not too bad. And will you do something for me? I've been carrying this case with my library books in it all the afternoon. I'm so tired. Will you take it and bring it along tonight? I'd be so grateful.'

He said yes and took the case. I said goodbye in my most cheerful voice and went as quickly as I could. I didn't want him to ask any questions!

I dashed madly back to the Hall and telephoned Chief-Inspector Vayle at Nunning Police Station. I said my little piece to him—I'd rehearsed it all carefully on my way back —and he promised to come along at eight-fifteen.

Then I breathed a sigh of relief and went to my room to dress for dinner. I put on my nicest frock, my most sophisticated air; but as I went downstairs, I wondered rather breathlessly just what would happen if my plot didn't come off.

I gave up wondering. I just daren't think of it!

I'D been at some odd dinner parties in my life, my pets, but I

don't think I've ever known one quite like the gathering at Tulse

Hall that evening at eight o'clock. Quite obviously, Mrs.

Vandeler and Miss Glynn had done their stuff good and plenty and

you could have cut the atmosphere with a knife. It was definitely

thick. Everybody was looking at everyone with eyes that

positively bulged with suspicion.

At a quarter past eight, Chief-Inspector Vayle was shown in. I took a deep breath, stood up and said my piece.

'Ladies and gentlemen,' I said cheerfully, 'I believe you all know that some important documents were stolen from a car on the day you arrived here. It was believed that the document case was stolen by a member of this house party. But I am terribly glad to tell you that that idea was entirely incorrect. The document case was stolen by a complete stranger. Someone who had evidently come down here especially for the purpose—an enemy agent.

'This man—you will be glad to know—will be coming here shortly. He is entirely unaware that he is suspected. He will be bringing the document case with him because he intends to leave the neighbourhood tonight. Needless to say, he will be arrested, and Chief-Inspector Vayle is here for that purpose.'

A sigh of relief went up from the assembled company. I caught Major Fells' eye and he gave an almost imperceptible wink.

Then the door opened and the butler came in. 'There is a gentleman named Mr. Vazey in the hall,' he told our host, 'He wishes particularly to see Miss Fleur.'

'There's your man,' I told the Chief-Inspector. 'I expect he'll try and wriggle out of it. But don't stand any nonsense. He'll probably say he's working for the Secret Service.'

He grinned. 'Don't worry, Miss,' he said. 'I've two men outside and a car. We've got a nice cool cell all ready for him at Nunning Police Station. We'll keep him there until we get further orders from your people in London.'

'That's marvellous, Chief-Inspector,' I said. 'There's just one other thing. You might take the document case he has, that is, the one that was stolen. Perhaps you'll get it at once and give it to me now—before you take him away.'

He said he would. A few minutes later I could hear the noise of an altercation in the hall. I felt almost sorry for poor Mr. Vazey. Then, the Chief-Inspector came back with the document-case.

'He's tried all sorts of nonsense,' he said. 'He tried to tell us he was a Secret Service man working with you. He's got his nerve all right! Anyhow he's safe enough now. We've put the handcuffs on him and in half an hour he'll be in a cell.'

I said: 'Thank you very much.' I looked very cheerful but I was wondering exactly what Mr. Vazey would have to say to me the next time he saw me!

When the police had gone I handed the document case to the butler. 'Please hang that up in the hall cloakroom, Soames,' I said. 'It's locked and it will be quite safe there.'

Major Fells took his cue. 'Don't you think I ought to put it in the safe?' he asked.

'Why?' I demanded. 'It'll be just as safe in the cloakroom and I shall be able to get it early in the morning without disturbing you. Just hang it up on a hook, Soames. It won't run away.'

The butler went off and everyone began to chatter at the top of their voices. They'd certainly had an interesting evening!

OUTSIDE in the hall the grandfather clock struck three. Major

Fells and I sat on the floor in the corner of the hall cloakroom

in the darkness. I felt rather cold and slightly dubious. I was

beginning to realise how very foolish I should look if my plot

didn't come off.

Just as I'd come to the conclusion that it wasn't going to come off I heard a very quiet footstep in the hall. We sat there tensely in the darkness. The footsteps came near. The cloakroom door opened—and Major Fells switched on the electric light.

Standing in the doorway—a brown document case in her hand—was the beautiful Miss Vavasour. I gave her my most charming smile.

'So, Miss Vavasour, it was you,' I said. 'Thank you for walking into the little trap I set for you.'

She called me a very rude name.

'You just had to fall for it, didn't you?' I went on. 'You thought we'd suspected the wrong person. You thought I was a fool not even to open the document case when the Chief-Inspector brought it in tonight. You probably thought I was an even greater fool to have hung it up here in the cloakroom. But all that made it very easy for you, didn't it? All you had to do was to bring the document case—with the real documents inside—and change it over with the one hanging up on the wall. Then you'd have been able to make your getaway with the copies of the documents which I have no doubt we shall find in your bedroom. You'd have been cleared of all suspicion.'

Her hand moved towards the pocket of her dressing-gown, but Major Fells caught it before it got there.

'No you don't,' he said. He took the small automatic pistol out of her pocket. He said: 'I think I'll put this young woman somewhere where she'll be safe. We'll keep her under lock and key until the police get here.'

He took Miss Vavasour away.

I sat in the cloakroom with the precious document case in my hand. I felt rather pleased with myself. At least I felt very pleased with myself until I remembered that my next job would be to ring Nunning Police Station and tell them to let the unfortunate Mr. Vazey out. I wondered what he would say. I imagined it would be rather lurid.

I went to the telephone in the hall but on my way I changed my mind. I thought I wouldn't ring the police. I'd ring Mr. Forrester, tell him the whole story; tell him that I had the documents safely, and the thief, and let him ring the police station and get Mr. Vazey released.

That, I thought, would be a good idea.

And anyway, the intuition seemed to have worked after all!

I SAT in the Palm Court at the Hotel Splendide and waited—I must say rather impatiently—for Mr. Forrester to turn up.

Mr. Forrester is the head of the Secret Service Department for which I have been working for the last six months, and is a rather attractive man—tall and slim, with an interesting face and hair that's just beginning to go a little grey at the temples—you know the type—one with very good manners and who looks at you rather as if you were something made of china and could break very easily.

Except I happen to know that Mr. Forrester can be very tough if necessary!

I was beginning to wonder what it was all about when he appeared. He came straight into the lounge, looked round, saw me and came over to my table, which was situated artistically under a large palm. Needless to say I had selected the table because the palm was there—it provided a very attractive background for the frock I was wearing!

I said: 'Good afternoon, Mr. Forrester. Sit down and have some tea. You must be very cold after your journey.'

When he had drunk his tea he gave me a cigarette; lit one for himself. Then he said:

'Miss Heron, I need not tell you that the Department is very pleased with the way you're doing your job. In point of fact we are beginning to regard you as rather a brilliant person. That is why we are putting you on to the assignment I'm now giving you—one which, whilst it will not be as dangerous as previous ones, will still require brains.'

I said: 'Thank you kindly, Mr. Forrester. I'm glad the Department thinks I have brains.'

He looked over his shoulder to make certain that no one was within ear-shot; then he went on: 'Miss Heron, some twenty-five miles away is a small village on the coast called Merling—a rather attractive place. The point is, however, that there is a cottage on the cliffs—Mayfly Cottage—and signalling has been observed to be taking place at this cottage. No one can find out who is responsible and the matter is made all the more difficult because, as far as we can discover, the cottage is empty. That, in effect, is the situation.'

I said: 'I see, Mr. Forrester. And the idea is that I go to this place and try to find out who is doing the signalling?'

He said: 'Yes. I thought you might go there as a London girl who's had a very tough time doing war work of some sort, and who has been sent down there for a rest. That would be a good background for you. Take some attractive clothes. Take life easily, amuse yourself and keep your eyes open. I'm perfectly certain that if anybody can succeed in this job it will be you.'

I said: 'That's very kind of you, Mr. Forrester. Am I to have any assistance from Mr. Vazey?'

He said: 'You're not very fond of Mr. Vazey, are you?'

'Well... I'm not exactly in love with him,' I replied. 'When he looks at me he always gives me the impression that I'm redundant and wearing the wrong shade of lipstick. I feel he doesn't approve of lipstick either.'

'Perhaps he's a little jealous of it,' he said. 'I feel like that myself sometimes! However, Vazey is really a first-class operative. And I expect you'll find him down there. You may need his assistance.'

I said: 'I probably shan't need it. But I expect I'll have to have it anyhow. I can't visualise Mr. Vazey keeping his long nose out of anything. When do I start, Mr. Forrester?'

'There's no time like the present, Miss Heron,' he said. He looked at his watch. 'There's a train that goes in an hour and a half. That just gives us time to have a cocktail together and drink to your success.'

I MUST say that I went for Merling in a big way. It was a

small and charming south-coast place—well sheltered from

the wind by the hills around it and not very much larger than a

village. There were not a great many signs of war about the

place, mainly because there were no airfields or naval or

military stations in the neighbourhood.

But the hotel was comfortable and the people quite nice. After I'd been there for a day I felt rather pleased with myself. I was in the mood for adventures and as my clothes—especially my dinner-frocks—had created a mild sensation, I felt rather happy about things—you know the feeling. Also there was a young naval officer staying at the hotel....

And on the third day, in the evening, after dinner, it happened. I was sitting in the lounge pensively smoking a cigarette and drinking my after-dinner coffee when it happened. He—the young naval officer that is—came straight over to me and said:

'Miss Heron, I think you and I ought to know each other. My name is Staynes—Lieutenant Hugo Staynes, R.N.—and very much at your service.'

'That's very nice of you, Mr. Staynes, 'I said. 'And I'm very fond of the Royal Navy. At the same time I'd like to know just why we ought to know each other!'

He looked at me with the most delightful grin.

'Because you're the prettiest girl I've seen for a long time,' he said. 'That's the first reason. The second reason is that I think you're frightfully attractive, and the third reason is that I want to have a little quiet talk with you. D'you think we might slip out casually—rather as if we'd known each other for some time—and go for a small walk round the garden?'

I hesitated for a moment, and then my instinct said: 'Yes, Julia, definitely yes! There's something behind this camouflage.' So I said: 'Yes, thank you very much, I'd like to,' and got a wrap and we went out.

It was quite a nice evening. Not too cold; there was a moon and the gravel paths and shrubs in the big hotel garden looked delightful in the moonlight.

We walked for a few minutes and then the Lieutenant gave me a long sideways look. He was smiling—he had the most attractive smile—and he said: 'Tell me something, Miss Heron.'

'What do you want to know?' I asked.

'Exactly what are you doing down here?' he said. 'I've been watching you. I don't fall—not for one little minute—for this overworked London society girl stuff that they say about you in the Hotel. Or is it true?'

'Why not?' I asked. But I thought: Julia, you'd better play for time. This all sounds a little odd. But, mes enfants, I was very intrigued.

He said: 'You don't look to me like an overworked society girl. You look like a very well-poised young woman with a great deal of common-sense.' He paused for a moment and then said, almost casually: 'You wouldn't be down here about a little matter of signalling to the enemy at night... would you?'

I raised my eyebrows in astonishment. 'Really, Mr. Staynes,' I said. 'I never heard of such a thing!'

'Forget it,' he said. 'But I thought I'd mention it. You see, there has been a certain amount of signalling out to sea at night from Mayfly Cottage—the place at the cliff end. That's why I'm here on leave. You see, Mayfly Cottage belongs to me and naturally the Naval authorities are rather interested. So am I. Do you see?'

'I see,' I said. 'But I really don't see what it has to do with me. Why should it?'

'You never know,' he said. He smiled at me again. I did tell you it was a delightful smile, didn't I?—and went on: 'You know, you don't sort of fit in with this place. There's something about you... an air... something I cannot quite describe....'

I said: 'Really, sir. I hope it's something nice!'

'And how!' he said. 'But definitely very nice. Rather mysterious though. I thought perhaps you might be down here snooping about the place for one of the Service Departments. I know they often employ very beautiful, very clever, women—women like you.'

'I never heard of such a thing in my life,' I said. 'And if there's signalling going on from your cottage you ought to be on the look-out for it instead of flattering me and suggesting I'm all sorts of mysterious things.'

He said: 'Perhaps you're right. But it's funny, whenever I do keep watch, nothing happens. However—if you can find your way back alone—I'll go along there now.'

'Please do,' I said. 'The mysterious signaller may be doing his worst at this very moment. That is, if you haven't made up the whole story merely as a means of introduction.'

'Honestly,' he said, 'I haven't. Although'—and he grinned—'I would have if necessary. You see, I just had to get to know you. Please be in the lounge when I get back to the hotel.'

'I'll promise nothing,' I said. 'But I'll consider it.'

HE went off, and I turned and began to walk back along the

main garden path towards the hotel. Half way there, just as I was

passing a clump of trees, a mysterious voice hissed:

'Miss Heron... just a moment, please.'

My heart almost stopped beating. I spun round and there standing underneath one of the trees, in the shadow, was my most unfavourite person, Mr. Vazey.

I said: 'Really, Mr. Vazey, you frightened me. Every nerve in my body absolutely jumped when you hissed at me.'

He said solemnly: 'That's probably due to too many cocktails, Miss Heron. Incidentally, may I ask just what is going on between you and Lieutenant Staynes?'

'Nothing at all,' I said. 'Merely a little after-dinner conversation. Is there any law against that, Mr. Vazey?'

'So far as you're concerned, yes, Miss Heron, there is, although perhaps in one way it isn't a bad thing that you've made the acquaintance of Lieutenant Staynes.' His voice was rather sarcastic.

I said: 'Please! Mr. Vazey, exactly what is on your mind?'

He said: 'If you'll come into the shadow of the bushes, Miss Heron, I'll tell you. I don't want to be seen talking to you.'

We stood behind a large rhododendron bush. He said: 'Perhaps you'd like to tell me what Lieutenant. Staynes was talking to you about. Was it something very interesting?'

'As a matter of fact, Mr. Vazey,' I said, 'it was rather odd. He began to talk to me about this signalling that's going on, and I wondered how he knew anything about it. And then he asked me if by any chance I was employed by one of the Service Departments down here to try and find out. Naturally I became a little suspicious.'

'I see,' he said grimly, 'And what happened then?'

'I denied having anything to do with any Service organisation,' I went on. 'And he told me he was very interested because the cottage from which the signalling had taken place belonged to him; that he was down here on leave trying to find out what was going on. I had an idea that he was worried about it.'

Mr. Vazey said: 'I bet he is. Listen to me, Miss Heron. It might interest you to know that I suspect Lieutenant Staynes. In point of fact I don't think he's Lieutenant Staynes at all. I think he's a German agent.'

'Good heavens!' I said.

He went on: 'This Staynes person is a mystery, but I've succeeded in making the acquaintance of a very charming girl to whom he is engaged—a delightful girl. She lives in a cottage on the cliff walk—Thistle Cottage. She's not feeling too good about him.'

'This is all very mysterious,' I said. 'What does she think?'

He shrugged his shoulders. 'She's very unhappy. She doesn't know what to think; but she's noticed one thing. Very often he makes appointments to meet her in the garden at Mayfly Cottage in the evening. When she arrives he's invariably there and it is on these nights that signalling has taken place. Naturally, she's very worried about it. So would you be if you suspected the man to whom you were engaged of being in the employ of the enemy. But the fact remains that this signalling does take place on the nights that he meets her there, and she thinks—'

'Exactly what does she think, Mr. Vazey?' I asked.

'She thinks he is merely using her as a blind to cover up this signalling business. In other words she doesn't believe that Staynes is in love with her at all. She's come to the conclusion that he's merely using her as a stooge—as an excuse to be down here; that he makes these appointments to meet her, gets to the cottage first, does his signalling and gets it over by the time she arrives or after she has gone. That's what she thinks.'

I said: 'It doesn't sound very good, does it?'

He said: 'No, it doesn't, but I've an idea, Miss Heron. We must act quickly. I would like you to go to Thistle Cottage now, and take care that Staynes doesn't see you there. You'll find Miss Lanning there. I told her I was sending you along to see her. Listen to what she's got to say. Possibly an idea may come to you.'

I said: 'An idea has come to me already. If you suspect Mr. Staynes surely it would be a very good thing for her to inform us in advance of the next appointment she has to meet him at the cottage. Possibly you might have somebody concealed—somebody who could check up on this signalling. If he were caught in the act all you'd have to do would he to arrest him. Isn't that right?'

He said: 'It's quite a good idea. Anyway, you go along and see Miss Lanning. Talk it over with her; make some sort of arrangement on the lines you've just mentioned. Let me know. If you want me urgently I shall be at the hotel.'

'All right, Mr. Vazey,' I said. 'I'll do exactly as you say. By the way, you know that Staynes is staying at the hotel. What is my attitude to him to be?'

He looked at me a little cynically. He said: 'I should maintain the attitude you've already adopted, Miss Heron. I think it would be the safest thing to do. You two seem to be getting on very well together, and we certainly don't want him to suspect anything at this moment.'

I said primly: 'Very well, Mr. Vazey, I'll do as you say. I'll be as charming as I can.'

He said: 'Yes, that's all right. But remember there's no need to be too charming.' He disappeared into the darkness.

IT took me fifteen minutes to walk to Thistle Cottage. On the

way I pondered on what Mr. Vazey had told me. And I must say I

began to feel rather suspicious of Lieutenant Hugo Staynes, R.N.

After all, his story did creak a little bit. And why

should he think that I was down at Merling for the purpose

of investigating the mysterious signalling?

Thistle Cottage was a delightful little place, standing by itself at the end of the cliff walk. I rang the bell and waited patiently—wondering what Sylvia Lanning was going to look like.

My curiosity was soon satisfied. As she opened the cottage door she said: 'Oh... Miss Heron... I'm so glad you've come. Mr. Vazey said you might. I do want to talk to you. Please come in.'

I felt very sorry for her. She looked tired and her eyes were red. She looked as if she'd been doing quite a lot of crying. I began to dislike Mr. Hugo Staynes more than ever.

She was petite and blonde and very pretty. The sort of girl that most men would want to protect and, I thought, the sort that isn't particularly overburdened with brains. It flashed through my mind that if the Staynes person was a wrong 'un—and Mr. Vazey seemed fairly certain on that point—this was exactly the type of girl he would choose for a 'stooge.'

She said: 'I've been lying down. I've had the most appalling headache. I've some tea in my bedroom... will you have some?'

I said thank you and followed her into a most delightful bedroom done in pale blue and white—the blue matching the charming kimono she was wearing. She poured tea for us and gave me a cigarette. Watching her I began to feel even more sorry about her.

I said: 'This is a most unfortunate business, Miss Lanning, but perhaps it will all come out right in the end.'

She shook her head. She said: 'I wish I could believe that. But I can't. Since I've talked with Mr. Vazey I just can't believe it...'

'Then you really believe that your fiancé—Mr. Staynes is responsible for this signalling?' I asked. 'That means that he must be an enemy agent—doesn't it?'

She shrugged her shoulders. 'It's all too odd,' she said. 'I only met him here a fortnight ago—he seemed terribly attracted to me and I thought he was wonderful. Of course, I never suspected anything at first. Then I heard about the signalling from Mayfly Cottage, and he told me that he was very keen to solve the mystery. Whenever we met it was always at the cottage. Now I discover from Mr. Vazey that the signalling has always taken place on the nights that I've met him there. Either before our appointment or afterwards. I can only think that he's been using me as a sort of blind—a cover—for what's he's been doing, I believe now that everything he said to me about being in love was all fake. He was just making use of me....'

Two large tears ran down her cheeks.

I said: 'Never mind... there are just as good fish in the sea... aren't there? And if you really believe all that then perhaps you can help us to find out—'

A telephone began to ring outside in the hall. She said: 'Oh dear... I feel that is he! What shall I do? What am I to say?'

'Just behave normally, my dear,' I said. 'Don't let him suspect anything. Be cheerful, talk to him. See what he has to say. Come along now, pull yourself together.'

She said: 'Yes... I will. You're terribly kind, Miss Heron.' She went out of the room and I heard her talking on the telephone, controlling her voice carefully; being bright and amusing.

I GOT up and began to walk about the room. I felt very unhappy

about the unfortunate Sylvia. I hoped that Mr. Staynes—or

whatever his name really was—would get what was coming to

him.

I stood in front of the dressing-table looking at her bottles of perfume and lotions and things. Lying there were two rings—one of them obviously an engagement ring; I suppose he had given her that. That would be part of the plan to gain her confidence. I picked the ring up and looked at it carefully. It was a really beautiful diamond and ruby ring and quite valuable.

Then I put it back and stood there thinking—all sorts of things; but mainly about Lieutenant Hugo Staynes, R.N.

She came back into the room. She said: 'He's asked me to meet him tonight—in fifteen minutes' time—at Mayfly Cottage, what shall I do? I didn't know what to say. I told him a kettle was boiling over and asked him to hold on.'

I said quickly: 'Go back and tell him that you will meet him there in twenty minutes' time. Don't worry. Just do that. We'll look after you.'

She said: 'Very well' She went back to the telephone.

When she returned, I said: 'Now don't worry. Get into your frock; hurry off and meet him. Don't let him suspect anything. When you've gone I'll get in touch with Mr. Vazey and we'll keep everything under control. Now off you go and play your part well.' I smiled at her. 'Remember the old proverb,'—I said '"Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned." This is where you get your own back!'

She said: 'I'll do just what you say. And I hope they shoot him. I don't think I've ever hated anyone so much in my life!'

I thought to myself... Well... well... it looks as if this is a tough spot for Cupid! I helped her on with her frock.

DIRECTLY she'd gone I went into the hall and telephoned

through to the hotel. I asked for Mr. Vazey. When he came on the

line I said: 'Listen, Mr. Vazey, this is important!'

'Ah,' said Mr. Vazey. 'So you've discovered something? Miss Lanning was able to tell you—'

'Miss Lanning hasn't told me a thing,' I said. 'Except that she is very suspicious of Lieutenant Staynes and that she doesn't like him very much because she thinks he's taken her for a ride. And I must say I agree with her.'

He said: 'I see... so you think Staynes....'

'Please listen, Mr. Vazey,' I said. 'While I was talking to Miss Lanning the telephone bell rang, about fifteen minutes ago. It was Staynes. He was asking her to meet him at Mayfly Cottage. I told her to agree. She's gone to meet him. And you must go there quickly.'

'But what's all the hurry about?' he asked.

'Only this,' I said. 'Staynes asked me earlier this evening if I was down here snooping for one of the Service Departments over this signalling business. Obviously he suspects that someone is wise to what's going on. Quite obviously he'll think that somebody has been questioning Miss Lanning. He'll probably ask her. And he might even try something drastic. I think you ought to go there at once. And you ought to take someone with you—somebody tough.'

'You might be right,' said Mr. Vazey. 'Incidentally, I've got one man watching the side door to the cottage from the cliff top. I'll take my armed driver with me and leave him and the car down the road. He can keep watch there. Then I'll go along to the cottage. In any event it can't do any harm. You'd better come back here to the hotel and wait for me.'

'Very well, Mr. Vazey,' I said. 'I'll see you sometime later. And I wish you luck.' I hung up, lit a cigarette and did a little very quick thinking. Then I went out of the cottage and hurried across the fields in the direction of the road that led to Mayfly Cottage. When I reached it I waited, behind the hedge.

It was getting cold and I stood there shivering a little. I am a great believer in instinct, my pets, that old-fashioned and much-derided woman's instinct! Anyhow, I thought, there's nothing like taking a chance sometimes, and if I was wrong... well, I was wrong and that was that!

Within a minute or two Mr. Vazey's car came along the road. It slowed down, stopped, and the driver parked it on the other side of the road, twenty yards from where I was standing, in the shadow of an oak tree. Mr. Vazey got out, said something to the driver, and hurried off towards the cottage.

I sneaked down the road, behind the hedge, keeping well out of sight, crossed over when I was out of sight of the car, made a wide detour that brought me in front of the car between it and the cottage, and then hurried down the centre of the road. When I arrived at the car I was breathless and excited. At least that's how I hoped I looked.

I said to the driver: 'I'm Miss Heron... Mr. Vazey's assistant. He says that you are to leave the car here and return to the hotel at once. You are to wait for him there. And you are to give me your automatic pistol.'

'Very well, Miss Heron,' he said. 'I know who you are. Mr. Vazey has told me about you. I'll go back at once.'

He gave me the pistol, got out of the car and began to walk down the road. I waited a few minutes—just long enough for him to get out of sight, got into the car, switched on, drove along the road until I found a gate, turned in and bumped and rattled across the fields back to Miss Lanning's cottage. I parked the car out of sight, went into the cottage, sat down in the hall. My heart was really beating hard now and I felt just the tiniest bit scared.

Five minutes passed and I heard steps outside. The door opened and Miss Lanning came in. She had obviously been hurrying.

Her eyes opened wide with surprise. She said: 'Miss Heron! But Mr. Vazey told me you had gone to the hotel. He said...'

'Quite,' I said. 'I know all about that. Mr. Vazey, I take it, has arrested Lieutenant Staynes on suspicion and you were so upset that you just had to return here, hadn't you, so that you could pull yourself together and relax?'

I produced the automatic pistol.

'You're the spy, my dear Fräulein Karla,' I said. 'And you've hurried back here to wait for your accomplice so that the pair of you can make your getaway while poor Mr. Vazey wastes his time cross-examining the unfortunate Lieutenant Staynes at the hotel. It was quite a good idea of yours to suggest to Mr. Staynes that you met at the cottage. Whilst you and he were talking on the ground floor your boy friend used to slip in at the side door—to which you had the key—go upstairs and, after Mr. Staynes had gone, get on with the signalling. You knew the Lieutenant would be suspected and you carefully fostered suspicion against him. Of course, he denied tonight that he was engaged to you. He probably told Mr. Vazey that he suspected you, but who would believe him? Nobody. Not until he had time to prove who he was and what he was doing down here, and by that time you and your boy friend would be far away.'

She said nothing. She just stood there, looking at me like a bad-tempered boa-constrictor. I went to the telephone.

'Now...' I said. 'I'll get through to the hotel and get Mr. Vazey to come along. Just sit down and relax. Don't move and don't make a sound. By the time Mr. Vazey arrives we ought to have your accomplice corralled here too—and very nice too!'

I don't know what it was she said because she said it in German, but believe me, mes enfants, it sounded very rude!

IT was very late, but the moon was still beautiful, and the

hotel gardens looked even more lovely.

Hugo Staynes slipped his arm through mine—which I think was very forward of him. He said:

'Of course, it was terribly clever of you to suspect the Lanning. I'd had my ideas about her for some time but I couldn't prove anything. I was trying all I knew to get something that would pin it on her. But I've got to hand it to her. She was clever, but not clever enough for you. Still... even now I don't see how you were certain it was she. I mean woman's instinct is all very well but....'

I smiled at him. 'It wasn't all woman's instinct,' I said, in what I intended to be a demure tone of voice. 'You see, I had the opportunity of looking at her rings which were lying on the dressing-table, at her cottage.'

He looked at me in surprise. 'Her rings!' he said. 'But I don't see....'

'One of them was engraved on the inside,' I said. 'I saw the words With love to Karla, and unfortunately for her, they were in German. She'd forgotten that!'

He looked at me closely. He said: 'Miss Heron, you've got something in your eye.'

'That,' I said, 'is a very old racket—that "something in your eye" thing. It's just a very old-fashioned excuse for trying to kiss a girl.'

He sighed heavily. He said: 'It looks as if my luck's out, doesn't it? Well... I suppose we ought to go back.'

I nodded. And just at that moment—believe it or not—there was a sudden gust of wind and I did get something in my eye!

Which shows, my pets, that the 'Luck of the Navy' isn't merely a proverb!

NEED I tell you, mes enfants, that life is full of surprises? Unfortunately there are never quite enough of them, and when they do happen there's no sort of guarantee that they're going to be the right sort of surprise. Agreed?

I think it was Confucius—one of those fearfully thoughtful Chinese philosophers—who said that 'you never know what's waiting round the corner.' So far as I am concerned Confucius was one hundred per cent right—and then some!

When, through my chance meeting with the not-so-very-nice Mr. Vazey, I found myself attached, willy-nilly, to the Secret Service, I imagined that life would present a vista of glamorous adventure. Instead of which nothing happened—just nothing at all. Life seemed to consist of trying out new hair styles in front of my mirror and wondering where—without being dragged off to durance vile—I could raise some more clothes coupons!

THEN, one afternoon, the telephone bell rang. It was Mr.

Vazey. Mr. Vazey, as I have already tried to tell you, is one of

those individuals who makes everything—even 'good

morning—sound unutterably grim. The fact that I answered

the telephone in my brightest and most seductive voice had very

little effect on him.

He said: 'Miss Heron, you've had a very long holiday. Now there's a job of work for you to do. Will you please be at the office in Whitehall at three-thirty?

I said: 'Certainly, Mr. Vazey. Am I going to see anybody very interesting?'