RGL e-Book Cover©

(Based on a vintage poster)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

(Based on a vintage poster)

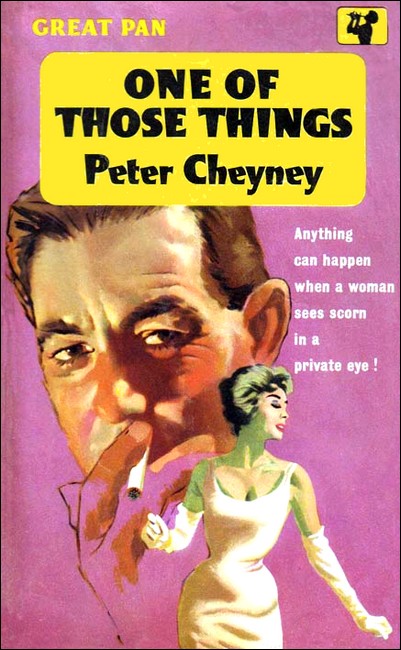

"One of Those Things,"

William Collins, London, England, 1949

WHEN the starting bell sounded O'Day came through the narrow passage-way that leads from the Tote and the back of the paddock into the enclosure. He stood looking across the race course watching the horses as they went over the first jump. He thought a jumping meeting was one of those things. You either liked it or you didn't. He thought he had an open mind on the subject which meant, really, that he was bored.

The people in the enclosure moved forward to the rails. Now the horses were rounding the bend and coming into the straight. As they went past the post O'Day saw that his own was last but one. Now he was certain he was bored. He shrugged his shoulders. So that was that!

He began to think about Vanner. One of these days, thought O'Day; one of these fine days, he would have to do something about Vanner. But he wasn't quite certain what. One thing was definite and that was that things couldn't go on as they were. It wasn't good for anybody.

O'Day was tall and slim. He had good shoulders. His lackadaisical style and lazy walk concealed a hard, sinewy physique.

His face, from the check-bones, which were high, was almost triangular. The jaw looked as if it had originally decided to come to a point; then changed its mind and suddenly squared itself off. His eyes were very blue, very steady. He seldom blinked. His hair was dark, cut close at the sides. It had a not unattractive wave. He was well-dressed. His brown shoes were well-cut and polished with care, his tweed over-check suit well-pressed. He wore no overcoat in spite of the fact that it was cold and that most of the women in the enclosure huddled in their fur coats.

He threw the cigarette away; moved towards the refreshment room at the back of the enclosure, where he ordered coffee. In finding the sixpence to pay for it his fingers encountered the four one pound notes in his pocket. He thought that wasn't so good; that it was time he went back to London.

He moved over to the coal fire; stood looking into it, sipping coffee. His mind was still concerned with Vanner. He thought that maybe he was between the devil and the deep sea—the deep sea being Vanner and the devil being something else that was more formidable because it was uncertain.

Somebody said:

"Hello, O'Day. How's it going?"

O'Day put his coffee cup on the mantelpiece over the fire. He turned slowly.

"Hello, Jennings. It could be worse." O'Day smiled. When he smiled his face became almost illuminated. The mouth moved very little but the eyes shone. He went on: "I've backed five horses in five races and each one of them has been in the last two. That must mean I'm lucky in love."

"You're telling me!" said Jennings cynically. "Maybe you'll get around to doing something about that one of these fine days."

"Meaning what?" asked O'Day.

Jennings shrugged his shoulders. "You know I haven't been working as an Insurance Company's assessor for ten years without finding out something about people. There are two sorts of people—two sorts of men I mean. Men that women go for and men that women don't go for."

O'Day moved a little. He took out a thin, silver case; lighted a cigarette.

"Meaning what?" he said again.

The other shrugged his shoulders. "The ones that women go for get affected by it or they don't. I've never known which class to put you in."

O'Day said easily: "Why worry about it? I hope it doesn't keep you awake at night."

Jennings grinned. He was a small man, with an over-developed paunch; grey, twinkling eyes. Just now he looked almost benevolent.

"Nothing keeps me awake at night," he said, "except maybe once or twice in the small hours of the morning, when I've been getting over a hangover, or thinking about going out and acquiring one. All the same I've been wondering about you."

O'Day said: "Look, you're killing me with curiosity. What's all this in aid of?"

"I'll tell you," said the other man. "You're getting most of your work from my firm, the International & General Insurance Company. Right?"

O'Day nodded.

Jennings said: "Insurance Companies are getting to be very particular about their investigators, O'Day!"

"I can hardly wait." There was a touch of a South Irish accent in O'Day's voice. Its timbre was almost caressing.

"I'm glad you're curious," said Jennings. He looked vaguely uncomfortable. He half-turned and looked round the big room as if he hoped to see someone. Someone who might possibly interrupt the conversation and save him some trouble. He turned back towards O'Day; stood, his hands in his overcoat pockets, hesitating.

O'Day smiled. He said casually: "Why don't you get it off your chest, Jennings?"

Jennings shrugged his shoulders. He said: "You did me a good turn once, O'Day. Remember? Now I'm trying to do you one. Perhaps you'll tell me to mind my own damned business or you might even take some sort of notice of what I say—that is if you ever take any notice of what anyone says, you Irish so-and-so. I've never thought you to be a darned fool. I don't believe that you're one now."

"All right," said O'Day. His tone was cheerful. "Let's take it that at the moment I'm not a darned fool. What's it all about?"

"There's been a helluva lot of talk about you and Vanner in the office," said Jennings. "I don't know if you know where your partner's heading, but if you don't I'm telling you that he's doing both of you a bit of no good. He's cockeyed five days in the week. He doesn't do any work. My own boss at the office told me the other day that your firm is weeks behind on the last four cases we handed to you for investigation. Yesterday one of our Directors was talking about finding another agency. And we're a damned good company, O'Day. If International & General throw you over, what are the other people going to say? All this is going on, and you're down here at Plumpton, backing losers and, apparently, liking it."

O'Day said: "I like the air. They tell me it's very good for the lungs."

"What the hell's the matter with your lungs?"

Jennings' tone was petulant.

"Nothing," said O'Day cheerfully. "Nothing at all. I was thinking of other people. People whose lungs aren't so good.

"For the love of Mike," said Jennings almost angrily. "Don't you ever take anything seriously? I suppose you know what they're saying?"

O'Day shrugged his shoulders. "Whatever they're saying I don't have to go into a song and dance about it. Anyway what is it that they are saying?"

Jennings dropped his voice. "Don't be a bloody fool all your life, O'Day," he said seriously. "Everybody in the office has the idea that you've worked that Irish charm of yours on Vanner's wife and upset his family apple-cart. The idea is that that's the reason for his being on a continuous jag. He's stuck on that baby, you know. He thinks she's marvellous; the best thing that ever came into his life. And even if she isn't, he's entitled to his little pipe dream. It's not so clever of you, is it? Why the hell do you have to do that and bust up a damned good business like you and Vanner used to have? I don't believe you give a damn about the girl. I don't believe you give a damn about any girl. Maybe you're just amusing yourself, but if you've got any sense you're not going to bust up the O'Day & Vanner Agency over it."

O'Day drew on his cigarette. "I suppose it hasn't occurred to you—or them—that these rumours could be wrong?"

"Don't be a damned fool," said Jennings. "I know they're not wrong. I know how this thing started and it's time you knew. Vanner's walked out on his wife Merys and told Stark of the Inter-Ocean that it was through you. He was talking to Stark about getting a divorce. He told Stark that four weeks ago, when you were supposed to be in Scotland on the Yardley case, you spent a long week-end with Merys Vanner at The Sable Inn—some dump near Totnes in Devonshire."

O'Day grinned. "Just fancy that! Who told him?"

"She did," said Jennings. "She told him. He's going to believe her, isn't he? So's everyone else." He began to put on his gloves. "Well... I've told you. Now you know."

"Thanks, pal," said O'Day. He grinned at Jennings. "Tell me something. Where's Vanner, and where's Merys Vanner?"

Jennings shrugged his shoulders. "You can search me as to where Vanner is. I wish I knew. I've been told to try and find him—or you. Merys told that girl in your office that she was going to Eastbourne—or somewhere round that part of the world."

O'Day said: "You're a nice guy, Jennings. You're full of good intentions. Have you had any luck down here to-day?"

"Nope," said the other. "Not a bit. But why should I? I've come to the conclusion I must be lucky in love. I hope so anyway. So I don't mind losing sometimes provided it doesn't hurt too much. It's a funny thing," he went on, "if I get into a poker game I lose; if I pick a horse it goes down. I came down here to back one in the last race. I came down here just to back that one horse. It's an outsider. I've had a bet in the other five races this afternoon and gone down each time." He laughed. "And now the last race is here and I'm not even going to have a bet on the tip I got."

O'Day said: "That's how it goes, Jimmy. But you've still got the love angle." He laughed. "You should worry if the horses don't go for you."

"I got this tip—Gelert—from Travis, one of our Directors," said Jennings gloomily. "It belongs to him. Red with a white cross bar. He said it'll doddle it at twenty to one." He sighed. "I never did like owners' tips."

O'Day said: "So you're not going to back it?"

Jimmy shook his head. "No. I've had it. So long, O'Day. And for the love of Mike watch your step."

He grinned uncomfortably; went away.

After a while O'Day came out of the refreshment room and stood on the green mound where people congregated to watch the progress of the races.

He looked over at the number board on the other side of the race course. Then he walked slowly through the narrow passage-way by the Tote. He went to the pound booking office and bought four one-pound tickets on Gelert. Then he went back to the refreshment room; bought another cup of coffee; carried it over to the fireplace; stood there, looking straight in front of him with vague eyes.

He thought he would have to do something about Vanner. Jennings was right. Insurance Companies, and especially big Companies like the International & General, did not like to hear peculiar rumours about the investigators who handled their business. He wondered how this stuff about Merys Vanner and himself had got about. Vanner, he thought, was a damned fool anyway. Why didn't he come and talk to him, O'Day, instead of drinking himself silly? Unless... O'Day considered the alternative. He considered the 'unless.' He wondered if that guess might be right.

Vaguely he heard the starting bell. He did not bother to go outside. He stood there thinking about the implications of what Jennings had said. A minute later people began to walk out of the refreshment room towards the enclosure. Soon he was alone. He put the untasted cup of coffee on the mantelpiece; went out of the refreshment room. As he walked towards the rails he saw the red racing jacket with the white cross bars go past the judge's stand. So that was that!

He remembered what Jennings had said about unlucky in cards, lucky in love. He wondered what the hell that meant to him anyway.

A voice behind him—Jennings' voice—said: "So I had to back five losers and let this one go. The bookies are paying twenty-five to one. Goodness knows what the Tote will pay. I should think a hundred. So I get the tip from the owner and I don't make it."

"That's too bad, pal," O'Day said. "Well, so long. I've got to go and get some money."

"You heel...!" Jennings' voice was acid. "So you backed my tip?"

O'Day nodded. "That's right. But don't worry. You said you were lucky in love."

Jennings asked: "What did you have on it?"

"Four pounds," said O'Day. "And maybe I'm going to win a hundred for it. I'd like that. It pays better than being a detective or an amateur Casanova."

Jennings said: "If you came down by car you can drive me back to town."

"No," said O'Day. "I'm not going back to London."

Jennings raised his eyebrows. "Where the hell are you going?"

O'Day grinned. "I wouldn't know. Maybe I'll think up some place. So long."

O'DAY lay on the bed in his first floor bedroom at the

Splendide at Eastbourne. When the waiter came in with the

Martini, he was looking at the ceiling, blowing smoke rings,

watching them. The waiter thought they were very nice smoke

rings. He wished he too could blow smoke rings like that.

O'Day sat up on the bed; took the Martini; tipped the waiter; began to sip the drink. He thought life was damned funny. He thought that women were damned funny, which was one of the odd things about life. He thought that when you imagined you were thinking about life most of the time you found yourself thinking about women. He grinned to himself.

He got up; began to walk about the bedroom, the Martini in his hand. He walked about for quite a time, smoking and thinking. He wondered exactly what Merys Vanner was doing. She had something on her mind. He smiled at the thought. And when a woman like Merys got something on her mind she made something happen. Something had to happen because she had a restless, impatient mind that could bear neither inactivity nor frustration. She had to do something about everything that perturbed her. She had lost the ability to relax. That, combined with her lovely figure, sense of dress, immense allure and not a great deal of breeding, spelt danger for anybody who got in her way.

O'Day began to unpack his suitcase. He thought it was an odd idea that he should have put a suitcase in the back of the car when he went to Plumpton races. Just another habit—the sort of habit he'd developed through life of always being prepared for the odd things to turn up. He remembered the number of times he'd gone to some place intending to return to London that day, and a few hours later had found himself somewhere entirely different, where he had been glad of the suitcase.

He undressed; took a hot and cold shower; shaved. He put on a double-breasted dinner jacket with a soft silk shirt and a watered silk tie. On his way down the stairs he looked at his watch. It was seven-thirty. He stood at the bottom of the stairs looking at the people who were sitting about the lounge. Nice, quiet people, O'Day thought. Business men and their wives—people who wanted to spend a quiet week-end to escape from the cares and worries of work, queues, rations, general depression and frustration.

Leaning against the door of his office, his burly figure relaxed and easy, a smile on his face, was Parker, the hall-porter, looking with a benevolent eye on the guests around him. O'Day went across to the reception on the right of the lounge. He smiled at the girl behind the counter; began idly to turn over the pages of the register. Then he came back to the current page. Eight or nine spaces before the one in which his own name was written he saw it—"Mrs. Merys Vanner, London." And the number of the room '134.' That would be on the second floor, he thought.

He walked slowly across the lounge towards the hall porter. He asked: "Parker, when did Mrs. Vanner arrive?"

"This afternoon, Mr. O'Day," said Parker. "About four o'clock."

O'Day nodded. He turned; walked across the lounge, through the swing doors, into the American bar. There were only half a dozen people in it, sitting up against the bar, drinking cocktails.

She was in the far corner. She was reading The Evening News, and apparently she was interested in nobody. O'Day grinned. That was her line—that she was never interested in anybody. What she wanted was for them to be interested in her—especially if they were good looking or presentable men. And after she'd concluded that they were interested in her, she either developed interest or she didn't, according to the way she felt. Merys, he thought, was definitely something.

She looked superb. She was wearing a black dinner frock of tulle over a slim-fitting, heavy satin foundation.

The satin caressed her figure; showed it off to the best advantage. And the tulle softened the lines. There were black sequin stars scattered over the tulle. She wore gun-metal nylons and American sandals with four-inch heels sprinkled with little jewels.

Her ash-blonde hair was cut in the latest chrysanthemum fashion. Her flame-red mouth threw into prominence her pale, almost transparent, camelia-coloured skin. O'Day sighed a little. He thought that when they christened Merys they might have given her a middle name—dynamite!

He looked sideways across the bar at her mascaraed eyes. They were fixed on the paper but, he thought, she had a wide vision to her amber-coloured eyes. He thought she had seen him, but she didn't propose to do anything about it—anyway not yet.

He sat on a high stool; ordered a Martini. He watched her in the mirror behind the bar. She seemed interested in nothing but the newspaper. O'Day put his elbows on the bar and relaxed. He began to think about all sorts of things—about the business—if you could call it a business the way things were going; about Vanner; about the International & General, who were becoming a little perturbed because their investigators weren't doing so well and did not seem to be behaving themselves. But underneath all this, the background idea was a question—the question being exactly what Merys was playing at.

O'Day finished the Martini. He heard the rustle of the newspaper as she put it down. In the mirror he could see her slip her mink coat about her shoulders; begin to walk across the bar towards the passage-way that led to the dining-room.

As she passed behind him, he said: "Hello, Merys... I suppose you haven't seen me?" He smiled at her.

She stopped. Her eyes opened wide in a mild surprise. "Well, Terry... fancy seeing you here! Isn't the world a small place?"

"Sometimes it's a little too small for me," said O'Day. "I want to talk to you."

"Of course...." She slipped gracefully on to the empty stool by his side.

He thought that everything she did, every gesture, every movement, was worked out very carefully.

She asked: "Did you know I was here or did you come, like I did, by accident—on impulse?"

He smiled cheerfully. "You came here on impulse? Like hell you did! You came here about as much on impulse as I did."

She said: "Dear-dear-dear! Doesn't this sound dramatic, Terry? So you didn't come here on impulse." She smiled, showing her white, even and pretty teeth. He noticed the real pearl necklace that Vanner had given her when they were married, and the beautifully-made, imitation diamond bracelet showing beneath the long sleeve of her gown.

He shook his head. "No... I came here because, in spite of the fact that you came here on impulse, Jennings of the International & General seemed to have an idea that you'd be down here. I met him at Plumpton race course. So I thought I'd come over and see what the form was."

She nodded. "I see. How nice for me, Terry. Are you going to buy me a little drink?"

He said: "I'll buy you a big one. Let's have two large and very dry Martinis and go and sit in the corner and talk."

She smiled again—a slow, almost affectionate smile. He knew it very well.

"I'd like that, Terry. I don't think there could be anything nicer in the world than sitting in the corner of an attractive bar like this talking to you."

"That's fine," he said. "You're going to have a good time."

When the Martinis were served, he carried them to the table in the far corner of the bar. Most of the people had disappeared.

They sat down. There was silence for a little while, then:

"What's it all about?" she asked. "There's something in the air, isn't there?" Her voice was caressing. "Almost something dramatic, don't you think? I like that."

"The trouble with you, Merys, is that you like dramatics too much. Or perhaps I should say that your sense of the theatre is over-developed."

She said quietly: "You mean that I ought to have been an actress?"

He grinned at her. "You'd have made a damned good one. But you'd have been an awful headache to the firm you were working for."

There was another silence. O'Day was turning over his opening gambits. He thought, if you tried to play Merys you had to play her carefully; otherwise there'd be a come-back—a worse come-back than the one he was dealing with.

He said: "Look, I've known Jennings for a long time. He and I have always talked pretty straightly to each other. When I met him at Plumpton to-day he talked plenty. He was almost disturbing."

She grimaced. "You don't mean to say that anything that Mr. Jennings of the International & General could have to say would disturb you, Terry? And I love hearing you talk. I love that very mild suggestion of a soft, south-west Irish accent you have. It thrills me."

O'Day said: "Fine. Now my day's made." He went on: "Jennings was a little worried about the International & General's Investigators—Messrs. O'Day & Vanner."

"No? Do tell me why. Don't tell me that my bread and butter's going to disappear." She looked at him archly. "Or have you and Ralph fallen out again, Terry?" Her eyes were laughing.

He said: "You should know. Jennings said that Ralph, whom I haven't seen for a week, has been on a five day jag; he said they've had no reports on the last four cases Ralph has been handling for them."

"This is serious, isn't it, Terry?" Her eyes were still amused. "I wonder what made Ralph go on a jag."

He said: "You wouldn't know, of course. I suppose you haven't seen him?°

She shook her head. "Not for the last—" she thought for a moment—"six days."

"That means," said O'Day, "that when you did see him you started something. You sent him on a jag. Why?

She shrugged her shoulders. She said demurely:

"You wouldn't be tough with me, Terry, would you?"

He smiled at her. "Wouldn't I? If I had to be I would, Merys. You know that."

She clasped her hands. "That's what's so delightful about you, Terry. Underneath you can be as tough as hell, can't you? You have been as tough as hell. And you don't like it when other people get tough."

O'Day drew on his cigarette. "Meaning you?" he queried.

She nodded. "Meaning me. What do I have to do? Do I sit with my fingers crossed, with my hands folded, and take everything that comes to me? Is that the idea?"

O'Day drank some of the Martini. He said: "I want to know what you told Ralph six days ago. I want to know what it was you said to him that sent him out on this rip-snorter. You know what he's like when he gets drunk. He's impossible. He's not so good-tempered when he's sober, but when he's drunk he's nobody's business. Look, O'Day Investigations were pretty good before Ralph ever joined them. They are still going to be good in spite of the bad luck we've been having for the last six or eight months due to something I'm beginning to put my finger on."

She asked again: "Meaning me?"

"Meaning you," said O'Day. "Why don't we cut out the frills and talk sense, Merys?"

She sipped a little Martini; smoothed out a fold in her tulle over-skirt.

She said: "So I'm to be good and tell you everything that happened. I'm responsible for all the trouble that's been happening in the O'Day-Vanner organisation for the last six months, and I'm supposed to be responsible for Ralph going off on this rip-snorter. You're perfectly right, Terry. And how do you like that?"

"I don't like it. And it's got to stop."

She looked at him sideways. Her eyes were narrowed. There was a proud gleam in them. "Has it? Oh, has it really? Clever Mr. O'Day. I wonder how you're going to stop it."

O'Day laughed at her. When she was angry she always got much more angry if you laughed at her, and when she got angry enough she occasionally told the truth.

He said: "You know, Merys, you're a very good-looking, attractive woman. You think you're clever. Sometimes I think you're a nit-wit. Sometimes I think you haven't enough brains to back a car into the garage on a wet day. Sometimes you make me so bored I could sleep."

"I see...." Her voice was very low and vibrant. He could see her little white teeth were on edge. "All right," she went on. "Well, you want it, Mr. O'Day, so I'll give it to you. I don't like being treated with contempt—the way you've always treated me. When I fall in love with a man it means something. So I was stupid enough to fall in love with you."

O'Day said: "Married women have no right to fall in love with their husband's partner. It's silly. That's the sort of thing you do. Besides, there were the other two or three individuals you spent your time falling in and out of love with. Why couldn't you make use of one of them?"

"Because I damned well didn't want to. When I tell a man I'm for him it's a compliment. That's what I think. But you didn't. You told me where I could get off and you thought I was going to take it, didn't you?"

O'Day sighed. "If ever I thought such a thing, quite obviously I was very wrong."

"You don't know how wrong you were, you Irish heel. What did you think I was going to do—go and sit in the corner and twiddle my thumbs? You know how it's been between Ralph and myself for a long time. I don't like him. He's not my sort of husband. God knows why I married him."

O'Day yawned. "My guess is you married him for the pearl necklace, the diamond solitaire ring you're wearing next to the fake one on your second finger, and a block of War Defence Bonds that he had then. That's my guess."

Her voice was trembling with anger. "I see... So that's what you think of me."

"Yes... don't you like it?" O'Day watched her clench the fingers of her right hand. He could see the scarlet nails pressing into her palm.

She said: "There are moments when I could kill you, Terry."

"I hope this isn't one of them. I hate dying on Saturday evenings. But go on with the story. So you decided to have your own back on Mr. O'Day?"

She nodded. "If you knew as much about women as you're supposed to know—you ought to realise that no woman like me is going to be turned down by a man like you without doing something about it."

"All right," said O'Day. "I'm bored with this preamble. Would you like another drink?"

"No, thank you." Her voice was incisive.

O'Day got up. He picked up his glass. "I would, so you'll have to keep the big dramatic story till I get back." He smiled at her over his shoulder.

He went to the bar; ordered a small Martini. He didn't want the drink; he wanted a few minutes in which to think. He wondered if by some means Merys could have planned this encounter; then decided that this wasn't possible even if she'd known Jennings was going to the Plumpton race meeting; that he might talk to him—O'Day. But she didn't know he was going there. He'd only decided that morning. So it wasn't prepared. He carried the drink back to the table, sat down.

He said:

"All right. What did you tell Ralph?"

She smiled. The smile was almost shimmering in its sweetness.

She said: "Last Sunday I told him that I thought you weren't very pleased with the way things were going in the business. I told him that since you'd been away on this case you've been handling in France he hadn't been near the office, and that Miss Trundle—" she smiled at him—"your very efficient secretary—had been ringing up all day because nobody had answered the post for four or five days, and she didn't know what to do about anything.

"I told him that there was going to be a lot of trouble when you came back. I told him that you were fed up with him; that you thought it was time he was out of the firm. I said I believed that you'd take any excuse to get him out. So he asked me what I thought he'd ask me."

O'Day nodded. "He asked you why?"

"Yes." She smiled at him; put her fingers on his arm. "I told him that you were stuck on me and that I knew you were a fearful man for chasing women; that you couldn't even lay off your partner's wife. I said I'd had a very tough time fighting you off during the three weeks he was away in Northumberland. Remember?"

O'Day said: "Nice work. What a sweet bitch you are, Merys."

"You're telling me! Who was it said hell hath no fury like a woman scorned?"

"I don't remember," said O'Day. "And I don't care. But obviously the boy was right."

She went on: "You can imagine that Ralph didn't like this. He's always been jealous of you. What he didn't say he'd do to you was nobody's business." She put up her hand as he started to speak. "Oh, I know he couldn't do anything to you. I know Ralph's a rather cheap sort of wind-bag. I've known that for years. But underneath that he's some sort of man, I suppose. And, as you know, he's very fond of me."

O'Day said: "I know. I've often wondered why. Any man who's fond of you ought to have his brain examined."

"Maybe," she said. "But the situation's been created, Terry. It's not a bit of good you going to Ralph and telling him that I made a pass at you. Do you think he'd believe it? He's been off on a jag. He's done all sorts of things that aren't going to do, the business any good."

O'Day nodded. "And you've got me more or less where you want me, is that it?" he asked.

"Why not? Quite obviously, there's going to be a lot of trouble in the firm of O'Day and Vanner."

There was another silence; then O'Day asked:

"What do you think you're going to get out of this, Merys?"

She shrugged her shoulders. "Ralph's going to do something about you. He's a bluffer, but he's got a nasty cunning streak in him. He'll find some way of getting back at you and of making you squirm. And that's what I want."

O'Day stopped himself asking her the question that was on the tip of his tongue. He asked himself instead: Supposing her scheme came off? Supposing the war between Ralph and himself came to a head? The partnership dissolved and the business ruined or half-ruined in the process? What was she going to get out of this? Vanner had no money except what he took out of the firm. He was a spend-thrift and Merys needed money. She had to have it. Had she got someone else lined up?

He finished his Martini; took out his cigarette case; lighted a cigarette. He did it very slowly. Then he got up.

"Let's go and eat dinner, Merys. It's a lovely evening and we can have a lot of fun watching the sea through the dining-room windows." He grinned at her. "I'd like watching the sea with you."

"You mean you'd like to throw me into it?"

O'Day shrugged. "If I threw you into the sea it'd probably be offended and give up its dead. Let's go and eat."

As she moved past him he noticed that her lips were trembling with rage.

WHEN the waiter brought the coffee the dance orchestra began

to play. Through the curtains O'Day could see the moon shining on

the sea. He thought the scene was very peaceful.

She smiled at him across the table. "It looks nice, doesn't it, Terry? It's a pity life isn't like that—all shiny and smooth."

He said: "It might not be so interesting."

She asked: "So you prefer it as it is?"

"What's the good of wanting something you can't get," said O'Day. "Trouble is a natural part of life. You can't duck it. It's what you do about it that matters."

"Well, Terry... what are you going to do about it? You're in a spot, aren't you?"

He raised his eyebrows. One eyebrow was slightly higher than the other. She thought this fascinated her; that most things about O'Day fascinated her.

He asked: "Would you like a liqueur?"

She said she would like some brandy. O'Day ordered the liqueurs and more coffee.

He said: "So I'm in a spot, am I? You tell me why,"

"Well, you must be in a spot. Such a spot that I'm wondering if even you can dig your way out of it, Terry—even you. Ralph believes that you and I have been very very wicked together. Do you know—" she smiled at him demurely—"he even thinks that we spent a week-end at a hotel in the country—I think he'll probably do something about that."

O'Day said: "You can't do anything about anything just because you believe something. If you mean that he might think of divorcing you, it's no good believing that we spent a week-end together at some hotel in the country. You've got to prove it."

She nodded. "You're perfectly right, Terry. But what is proof? It's a funny thing. You know, whenever I've read reports of divorce cases it seems to me that the Courts believe all sorts of things. But they are always inclined to believe the worst."

"Maybe," said O'Day. "But you've got to prove misconduct."

"Yes... I suppose so. But if a woman arrived at an hotel late; if the woman had made the reservation; if the solitary night porter, very sleepy, showed her up to her double room and the man arrived afterwards so that he wasn't seen; if she said the man was you, it's quite a chance that somebody would believe it. Unless you could prove an alibi, Terry."

He said: "Well, that would be pretty easy, wouldn't it, Merys? Three weeks ago I was busily engaged—and certainly not with you."

"That is so, my dear," she said. "You were in the country on the Yardley case. And I know that you couldn't talk about it. It was very very confidential, wasn't it, Terry? Ralph told me. So it seems that I am prepared to state that you were with me, and you on the other hand aren't able to state where you were. It doesn't look so good for you, does it? In any event Ralph's got quite enough to issue a petition. That wouldn't do you or the firm any good."

O'Day said: "I wonder what you're playing at. Are you just trying to get back on me or what?"

"Maybe I'm just trying to get back on you. You know what I think, Terry? I think the easiest thing would be for you to play it my way. After all, Ralph has always been something of a sick headache in the firm, hasn't he? Besides that, he bores me. I don't think there's anything worse than being bored by a man. Why don't you let him get his divorce? I think you'd be very much better on your own. You could start all over again. You and I could have quite an amusing time, Terry. I'm very fond of you, I think you're an attractive man."

O'Day grinned. "Me—and who else?" he asked. "I hate being in a queue, Merys. I don't like it and I'm not going to do it."

"Well, what are you going to do? If Ralph issues his petition you're either going to let the case go into the undefended list, which makes a lot of trouble for you, or you're going to defend it, which means a lot more trouble."

O'Day said: "It looks to me as if in any event there's going to be a lot of trouble."

She nodded her head prettily.

O'Day sighed. "I think it's all very interesting but slightly boring. Just as Ralph seems to bore you, I think you bore me, Merys. I don't like women who try to make love to me by force."

She shrugged her shoulders. "All right. Then you're still in the spot I mentioned, and you don't t know what you're going to do. You're going to have a bad time working it out, Terry."

He said: "You're quite wrong, my dear, I know exactly what I'm going to do." He got up. "I'm certainly not going to stay in this hotel with you, not even if we're living on separate floors. I think I'll go back and look at London."

She smiled. "I'm sorry I've spoiled your week—"

O'Day said: "You haven't. I only came down here because I wanted to talk to you. Now I've talked, I'll go. Good-night, Merys. I hope it keeps very, very fine for you."

She put her hands on the table. She looked at him from under half-closed lids.

"Damn you, Terry...! Before I'm through with you you're going to pay—plenty."

"And like it, I suppose?" said O'Day. "Good-night, sweetheart. I hope I won't be seeing you... well, not much."

When he had gone she sat there looking straight in front of her, drumming with long, slender fingers on the table.

IT was eleven-thirty when O'Day drove the car into the garage

near Sloane Square. He handed it over to the man in charge; told

him to have the suitcase sent round. Then he walked in the

direction of his rooms on the other side of the square.

It was a fine night. Inside the breast pocket of his dinner jacket O'Day could feel the bulge made by the wad of one hundred and thirty one pound-notes that he'd taken from the Tote on Gelert. He thought that was something. In any event it was better to be in a tough spot with a hundred and thirty pounds than without it. He didn't like the situation. He began to think about Merys and Ralph Vanner. Merys was quite something, he thought. She knew what she wanted and she went straight out for it. It looked as if she wanted him. O'Day remembered all the incidents in the office—times when she'd come in to see Ralph, who by some chance was never there when she came.

From the beginning she'd tried a mild flirtation with O'Day, and afterwards, when the atmosphere had turned into something more serious, he'd decided it would be a good thing to tell Merys where she got off. He thought he might have known that women like Merys Vanner didn't get off; they stayed on the bus and made things not too amusing for everyone concerned.

And Ralph Vanner? O'Day thought he might easily be an unknown quantity. It was one thing to say he was weak, a bluffer, inefficient and a drunkard. But there was something more to Ralph than that. When he wasn't drinking he was quite a person and he had a vindictive streak in him. Also he was very much in love with his wife. Ralph was quite capable of causing all sorts of trouble without any assistance from Merys and, with the pair of them at work causing trouble, O'Day thought that things might be quite exciting in the near future.

He shrugged his shoulders. He thought: This is just one of those things. One of those things which happen to people and which you play off the cuff or deal with as best you can. He remembered the song: Just One of Those Things.

He let himself into his apartment block; went up in the lift to the first floor. There was an envelope lying on the carpet in the hallway of his apartment an envelope that had obviously been pushed under the door. It was addressed to him but he did not recognise the handwriting.

He lighted a cigarette; mixed himself a whisky and soda. Then he tore open the envelope and read the letter.

There was no address at the top. It was dated that day and said:

Dear O'Day,

I wonder if you remember me—Nicholas Needham? I met you when you were on a job in America four years ago—one of those war-time things. Do you remember?

I've had two days in London. I've been here, in England, for a month trying to make up my mind about this thing and whether I'd come and see you about it. Now I've got to do something and fate, in the shape of a friend I met a few weeks ago and who talked to me about you and your work, gave me your address and generally acted as a boost for Mr. Terence O'Day, decreed that when I did arrive at your office, this morning, you should be away.

Your secretary told me she didn't know where you were. She expected you back soon. Also she didn't know where your partner was. That didn't interest me because I wasn't interested in your partner, and didn't want to talk to him.

The thing is this: I want you to do a job for me. Something that our mutual friend told me would be right up your street; something requiring your own particular sort of mentality. It's a rather peculiar commission to ask an investigator to undertake. It concerns a very charming woman with whom I was very much in love during the War years; to whom I proposed and who turned me down. A rather lovely person who lives in Sussex.

She is very nice—rather lonely—and I think that unless she is helped very quickly there is a great deal of trouble before her one way or another. Unfortunately, because I have to leave for Africa to-day, I can't do anything about it. But you might be able to.

I asked your secretary, Miss Trundle, what was the best way of getting into touch with you. She said she didn't think you'd be at your apartment but if I liked to leave a note for you in the office I could do so. So she gave me a pad and put me into the small waiting room next to your office, and I sat down and wrote the whole of the story—everything I thought, everything I knew and what I wanted you to do.

When I'd done it I felt better. When you were working in America I found out enough about you to make me believe that you were the sort of person who wouldn't leave a job without doing his best to fix it one way or the other, and I hoped that you'd remember that I once did something for you.

Anyway the whole story's there. I wrote it out at length; borrowed a stout manilla envelope from Miss Trundle. I put the story in the envelope with seven hundred and fifty pounds in five-pound bank notes. I should think your expenses might be half that sum. The rest is for you. She said she'd put it in the right-hand drawer of your desk. She said you'd probably get it within the next day or two.

After that I felt better. But I also thought that in case you returned to your apartment fast and went off somewhere without going to the office I'd leave this note for you. She gave me your address. Well, there it is, O'Day. I hope you'll do what I ask. I hope you'll be successful. Maybe we'll meet again one of these fine days if I get through with the job I'm on. If we do, we'll have a drink together. If not, that is too bad. So long and good hunting.

Nicholas Needham.

O'Day put the letter in his pocket; drank some whisky and soda; sat down in an armchair. It seemed that the financial aspect of life was improving. A hundred and thirty pounds and seven hundred and fifty was nearly nine hundred and, he thought, you could do a hell of a lot with nine hundred pounds.

He stubbed out his cigarette; went into the bedroom; took off his dinner jacket. He was untying his tie when an idea occurred to him. He re-tied his black bow; put on his jacket; switched off the lights; went out of the flat. He walked back to the garage.

Five minutes later he drove towards his office in Long Acre. The street was dark and deserted. When he arrived he opened the outer door; locked it behind him; climbed up the long, old-fashioned flight of stairs to the first floor. At the end of the corridor through the half-glass door he could see the light in the office was on. O'Day wondered about that.

He walked down the passage, his footsteps echoing through the empty building. In front of the door he stopped, looking at it. On the frosted glass he could read O'DAY & VANNER INVESTIGATIONS. He thought maybe he'd be altering the name soon. He thought O'Day would look better by itself.

He got out his key; put his hand on the door knob. The door was open. He wondered about that too. It wasn't like Trundle not to have locked the door when she left. Maybe, he thought, she'd come back for something and forgotten to lock the door.

He went into the office. Trundle's typing desk and, on the left of the room, her other desk, were orderly. She was a tidy person. Everything looked normal.

He went into his own room; switched on the light. He stood in the doorway, looking at it.

From where he stood he could see that the right-hand drawer of his desk had been smashed open. The drawer was three-quarters open, the lock burst. O'Day sighed. He walked slowly across the room; stood looking at the drawer. There had been nothing in it except half a bottle of whisky. He'd always kept it locked, but Trundle had a key in case she wanted to leave a confidential message on one of the occasions when he came back to the office late. There was no manilla envelope with the letter which Needham had written him, and there was no money. But there were a few pieces of charred paper in the ash-tray on the desk and, lying in the bottom of the open drawer, was a torn half sheet of quarto paper. Typed across it were the words:

I hope you like this, sucker. I can do with the money and I burned the letter that was with it. I was too bored to read it, and it might annoy you. This is just a little on account. R.V.

O'Day sighed again. He closed the drawer; turned off the light; went through the outer office. He closed and locked the outer office door. He thought he'd certainly have to get someone to paint out the name of "Vanner" on the door.

He walked slowly down the stairs. On the way down his mind switched back to Merys Vanner. He thought she was a very interesting person—so interesting that most of the time you didn't know which way her mind worked. He thought that somehow for his own sake he'd have to find that out.

He drove through the deserted West End, through Kensington on to the Staines road. He sat relaxed behind the driving wheel, a cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth. He thought it was too bad about the seven hundred and fifty pounds, especially at a time like this. He wondered what Vanner was going to do with it. Maybe, he thought, he'd use it to begin divorce proceedings. O'Day's mouth twisted into a cynical smile.

Thirty-two miles outside London he swung the car into a side road. He drove down a long carriage-way; pulled up eventually at an attractive house shielded from the road by a line of trees. It stood in a court-yard, and the moon illuminated its antique front and portico.

O'Day parked the car in the courtyard; rang the bell. He waited patiently until the door was opened. Then he said: "Good evening."

The man inside looked like a family retainer. He wore striped trousers and a black, alpaca jacket. His hair was grey with long side-whiskers. He looked almost benevolent.

He said: "Good evening, Mr. O'Day. We haven't seen you for a long time."

O'Day asked: "Where's Mr. Favrola?"

"In his office," said the man. "He's alone."

O'Day handed over his hat.

"I'll have a word with him. Don't bother to announce me." He walked across the wide hall, furnished with old oak furniture, down a passage-way. There was a heavy curtain at the end. O'Day pulled aside the curtain, knocked on the door; went in.

The room was well-appointed. A fire was burning in the grate. On the other side of the room was a large oak desk, and behind it sat Favrola—fat, placid, immaculately dressed, his dinner jacket looking as if it had just come from under the tailor's iron.

He got up. "I am glad to see you, Mr. O'Day. It ees a long time since we 'ave seen you."

O'Day said: "It's a long time since I have had any money to play with."

"A leetle drink?" asked Favrola. He opened a cupboard beside his desk; produced a bottle of Bourbon and two glasses, a carafe of water. He poured out two neat drinks; handed one to O'Day; poured out a chaser of water in another glass; put it on the edge of the desk.

He said: "You are in the luck again, Mr. O'Day? But then you're always lucky, aren't you?"

"Sometimes.... It depends on what you call lucky." O'Day drank a little of the Bourbon. "What goes on upstairs?"

Favrola shrugged. "A poker game, that ees all. Less and less people come 'ere these days, and if they do come they are the sort of people we don' want. Too much money and no manners!"

O'Day asked: "Any good gamblers?"

Favrola shrugged again. "Mr. Darrell ees 'ere. It ees extraordinary. 'E 'as been winning a lot of money lately. For nights he come 'ere and play anything—faro, chemin-de-fer, straight poker—anything you like. 'E won all the time. To-night 'e cannot do anything that ees right. So 'e got out of the poker game upstairs. 'E ees jus' standing watching them." He smiled amiably. "But per'aps he would gamble with you..."

O'Day finished his drink. "Maybe I'll just look. I'll be seeing you."

He went out of the room, back into the hallway, up the wide, curving flight of stairs. At the top he crossed the broad, thickly carpeted landing; opened the double doors facing him. The room was so large that it looked empty. There were about ten tables, but they were all deserted except the one nearest the door where six people were playing poker. Sitting in a chair against the wall, sipping a brandy and soda, was Darrell.

O'Day went over to him. "Good evening, Darrell. They tell me it hasn't been so good."

Darrell shrugged his shoulders. He was a portly, bald-headed man with small eyes that sometimes looked good-humoured, sometimes cunning.

He said: "Well, it comes and goes, you know. How's it been with you?"

"Not so good," said O'Day. "I don't even know why I came here. I'm having a run of bad luck. I don't think I could win anything. You know—you get that feeling sometimes." He was watching Darrell. He saw a bright gleam come into the gambler's eyes.

Darreil said: "Well, it can go like that. Do you want to roll them?"

O'Day said: "You mean poker dice?"

Darrell nodded.

"Well, I don't want to," said O'Day, "but since I'm here I suppose I must. Ten throws and finish?"

Darrell said: "Why not?"

They went to the far end of the room. On a small table was set up an American dice cage.

O'Day said: "You go first. What's the stake?"

"Ten pounds for me," said Darrell. "If I lose I double up." He spun the cage. It threw four queens. "Your luck's still not holding. Beat that, O'Day."

O'Day said: "It's not possible." He spun the cage. The dice rolled down the table. Four kings came up. "That must have been an odd stroke of luck. It seldom happens to me."

Darrell said: "Now it's for twenty and your money. I'll throw you for forty or nothing."

O'Day nodded.

A quarter of an hour later he went down the stairs. The hundred and thirty pounds had increased to six hundred and fifty.

At the bottom he turned down the passage-way; went into Favrola's room. He said: "I'll have a drink with you. His luck's still not so good."

Favrola said: "What you mean ees that your luck ees always good. You tell me sometimes you are 'aving a run of bad luck. Mos' men would like to have one of your runs of bad luck. God help anybody who was against you when it was what you call good luck."

O'Day said: "Well, I'll be seeing you. I suppose you haven't seen anything of Ralph Vanner—my partner—lately?"

Favrola spread his hands. "I 'ave not and I don' want to. 'E comes here and if 'e wins a leetle money 'e gets very excited. If 'e loses money it ees not so good. You understand? You know," Favrola continued, "I theenk there ees something wrong with that man. I theenk there ees something worrying heem. And 'e's drinking like a fish."

O'Day nodded. "He likes drinking. I suppose his wife hasn't been in here?"

Favrola said: "Yes... once or twice. But not with heem. Sometimes with this man—sometimes with that."

O'Day asked: "Has she had any luck? I should theenk she always had luck," said Favrola. "She comes with some man and if 'e loses, well... what does she care? If 'e wins, the next time she comes with heem she 'as a new brooch sometimes diamonds—sometimes a bracelet." He smiled.

O'Day said: "You mean she's clever."

Favrola nodded. "I theenk she ees ver' clever. I often wonder how she came to marry a man like Ralph Vanner. No one could accuse heem of being clever."

O'Day said: "I suppose not. Well, I'll be seeing you!"

He went out; closed the door quietly behind him.

It was two-thirty when O'Day arrived back at his apartment. He went into the sitting-room; switched on the electric fire. He mixed a whisky and soda; sat in the big armchair looking in to the red of the fire that was just turning into gold. He thought that life was a strange proposition whichever way you played it. It did what it liked with you. All sorts of things happened whether you wanted them to or not. You couldn't steer life. You could only go with it; play it as it came; play it off the cuff.

He began to think again about Merys Vanner; to wonder what was in her mind. On the face of it, it all seemed very plain. She was in love with him and he'd turned her down. So she had faked some sort of story and gone to her husband to put him—O'Day in bad. She talked Ralph Vanner into playing what she wanted him to play, and now Ralph was on the warpath.

O'Day lighted a cigarette. It all seemed very nice and clear, especially after his conversation with her. Or was it? Vanner had gone haywire; was hitting the high spots; drinking himself silly, probably considering a divorce. And in the meantime had got back on him—O'Day—as well as he could by burning Needham's letter; by taking the seven hundred and fifty pounds. All this seemed obvious, but was it?

What did she expect to get out of this. Did she expect that O'Day would marry her? He grinned. He thought that Merys Vanner knew him too well for that, especially after what he'd told her in the past. So there might be something else to this obvious story. Merys, he thought, had a tortuous, peculiar mind. You never knew what she was playing at. A scheming woman, he thought. She would use anything for her own advantage.

He stubbed out his cigarette. He thought that, actually, the way to play life was always obvious. You just followed your nose and hoped for the best.

He got up; turned off the fire. He finished the whisky and soda; went to bed.

O'DAY woke up on Monday morning at ten o'clock. He rang for breakfast and when it was brought sat up in bed, drinking coffee, thinking about Needham. He remembered Needham—not too clearly, because lots of things had been happening at the time when he'd met him during the war years in America, but there was still a fairly clear picture in his mind.

Needham was a tall, thin New Englander. His mentality, O'Day had thought, was peculiar. He was almost Victorian in his outlook, especially about women, to whom he would not be very attractive. Needham had done him a good turn when O'Day, in the course of an investigation, had taken a short cut that was a little too short for the American authorities who were then employing him.

O'Day ate toast and marmalade, and thought he couldn't see Needham mixed up in any business about a woman that wasn't entirely proper. Or could he? When it came to women you never knew a great deal about any man and even an ascetic type like Needham might go haywire if he met the right type of girl. The tougher they were the harder they fell. But he could easily imagine him worrying about a woman of whom he had been fond, to whom he had proposed and who had turned him down. O'Day thought that the fact that the American had been sufficiently in love with a woman to propose marriage to her would cause him to take quite an interest in her future. Apparently he had; was not satisfied with it; was worrying about v it; wanted to do something about it.

But why hadn't Needham come to see him about this business before? He had been in England for some time and he left something which was to him important till the last two days of his stay. Then he'd gone off on some very private business. O'Day thought that he could guess about that one. Needham had been working on a line of American intelligence. He was a Colonel in the Intelligence Corps, and he was probably still doing some under-cover work for Uncle Sam.

O'Day sighed. He thought it was a pretty tough proposition to be handed a case about which you knew nothing except that some woman somewhere might be heading for some sort of trouble. He shrugged his shoulders.

He got out of bed; bathed; began to shave. Now his mind switched to Vanner. Something definite had to be done about Vanner. Or had it? O'Day played with the idea of finding Vanner and talking sense to him in a very hard way. Then he thought that perhaps the idea wasn't so good. Vanner had been sold a sensational story by Merys and believed it. Because, whatever his faults might be, Vanner was not fundamentally dishonest. He wouldn't have stolen the Needham money out of the drawer unless he was blind and in a hell of a rage. O'Day visualised him coming into the office; smashing the drawer open; opening the envelope; stuffing the notes into his pocket; then burning Needham's letter in the ash-tray on the desk. That was all right. That was the sort of thing that Vanner would do if he was in one of his insensate rages brought on by too much liquor and a vindictive jealousy about Merys. And it was like him to have typed the note. He could never write—at least not legibly—when he was cock-eyed.

So he'd sat down at Trundle's desk, typed out the note, put it in the drawer and cleared out without bothering to lock the door behind him. That was all in the picture. And these guesses did not presuppose that Vanner was going to listen to reason. Therefore, why bother about it? O'Day wondered what he was going to do about anything. He thought "when in doubt don't" was a very good motto for people who liked doing nothing. But his mental make-up was much too active for that process. And he was annoyed. Underneath his suave exterior—although he seldom got excited about anything—O'Day was extremely annoyed with the situation.

The business which he'd carefully built up by himself before Vanner had ever come into the partnership was getting a pretty bad reputation. Something had to be done about that. He came to the conclusion that thinking about things wasn't a great deal of help.

He telephoned the garage for the car. When the porter rang through to say that it had arrived he packed a suit-case; had it taken down to the car.

He said to the porter: "I may be back. I may not. If any messages come through for me write them out and leave them in my room."

He got into the car; drove in the direction of Long Acre. He thought that his instructions to the porter might be amusing. It presupposed that he might be going somewhere. If he were, he wasn't quite certain where. But the idea was there and who knows—it might be a good one!

When he went into his office Miss Trundle was sitting at her desk examining her finger-nails. Miss Trundle was not at all like her name. She was of middle height, of good figure and had a definite clothes sense. She was a medium blonde and wore light shell glasses which added a whimsical touch of almost grand-motherliness to a very attractive face. She had been with O'Day since he had started the business. She did not like Vanner. She did not like Merys Vanner. Her attitude towards O'Day was a little odd—at least she thought so. She wasn't quite certain whether she disapproved of him or whether she was rather fond of him. Actually, although she didn't realise it, the two things went together.

She said: "Good morning, Mr. O'Day. I'm afraid there's been a spot of bother." She said this with a bright smile as if it were something pleasant and not too important.

"I know," said O'Day. "I was here on Saturday night. Somebody burst my whisky drawer open and took an envelope out. You're perturbed about it, aren't you?"

She said: "Not if you aren't."

O'Day turned round the chair at her typing table so that it faced her. He sat down.

"Look, Nellie," he said, "what went on here on Saturday morning?"

She said: "Well, it was perhaps unfortunate that I didn't know where you were. I didn't know where Mr. Vanner was—not that that mattered. A gentleman called Colonel Needham came in. It would be about half-past ten. He wanted to see you particularly. I thought he was pleasant. He was tall and stern in a rather nice sort of way. With iron grey hair. In fact he seemed a very nice type of man—a responsible type, if you know what I mean."

"I know what you mean—the sort of man that any woman would be safe with." O'Day grinned at Miss Trundle.

She said: "Well, if you want to put it that way—yes. He definitely wasn't your type of man."

"Nuts," said O'Day. "Well, what happened?"

"I told him that I didn't know where you were; that I'd already been through to your apartment and you'd left; nobody knew where you'd gone to, but you'd taken a suit-case. I knew that didn't mean a lot, but I told him that it was improbable that you would be back at your apartment over the week-end; that I didn't know where to reach you, but that I thought you'd be in touch with the office on Monday—that is to-day.

"He said that wasn't any good; that he was leaving England on Saturday afternoon. Then I asked him if Mr. Vanner would do. I said I might possibly be able to find Mr. Vanner. He said he didn't want to see Mr. Vanner. He sat down and smoked a cigarette; then he asked if he could write a letter to you and if I would make certain that you got it directly you arrived. So I put him in the waiting room; gave him a pad. He was there for quite some time. Then he asked me for a large envelope. I gave him one.

"When he came out of the waiting room he gave me the envelope. He said he wanted you to have it as soon as possible. I told him that you might possibly look in at the office on Sunday if you came back to London, and that I would put it in a drawer where I left messages for you. I went out for coffee and when I came back I put it in the whisky drawer and locked it."

"Is that all he said?" asked O'Day.

"No. He said good morning and was going out of the office. When he got to the door he said could he have your address because he'd like to leave another note for you there in case you went there before you came to the office. I gave it to him. I thought he looked the sort of person who ought to have it."

O'Day nodded. "Fine. Did anything else happen?"

"Yes...." Her tone changed slightly. There was an acid note in it. "Mrs. Vanner came through. I don't know what the time was, but I should think it would be about ten o'clock. She asked if you were in. I said no. She asked if I knew where you were. I said no ... had she tried your apartment? She said yes, you weren't there. So I told her," said Miss Trundle almost archly, "that I was afraid I couldn't help her."

O'Day got up. "You liked telling her that, didn't you?"

Miss Trundle said nothing.

O'Day went into his office. He walked about for a few minutes. Then he came out; stood in the doorway between his office and the outer one.

He asked: "What's the post like?"

"Indifferent," said Miss Trundle. "Nothing very much. The International & General came through this morning and asked when they were going to have the reports on the four cases we are investigating for them. I told them I thought they could have them this afternoon."

O'Day asked: "Why?"

"They came in this morning. Mr. Vanner sent them."

"Where did he send them from?" asked O'Day.

"I don't know. There was just an envelope with the typewritten reports. A boy brought them with Mr. Vanner's compliments. There was no note with them—just nothing at all."

"What do the reports look like?" asked O'Day.

She said: "Very good. I was surprised, having regard to the state that Mr. Vanner's been in during the last three or four days. I didn't think he'd be working."

O'Day said: "Maybe he got somebody else to do the check-up for him. He's done it before when he's been on a binge. All right. Write a letter to the Assessors Department of the International & General and send the reports round with my compliments by hand." He yawned. "Then you'd better get someone to paint the name 'Vanner' out on the door. This is going to be 'O'Day Investigations' in future."

She said: "I like that, Mr. O'Day."

"Who cares about your opinion?" O'Day grinned at her. He was trying to co-relate in his mind Vanner's hitting the high spots for five days, stealing the money, burning the Needham letter, and at the same time bothering to get somebody to cover the International & General investigations. He thought it didn't add up.

He said: "I'm going to get my hair cut. You find out for me just where the Sable Inn is, will you? I believe it's in Devonshire. Let me know the mileage and the best road."

"Very well, Mr. O'Day."

O'Day stopped at the door. He said: "If Vanner got somebody to check on these Assessor's reports for him I wonder who he'd use. Have you any idea, Nellie?"

She considered for a moment, then: "I know he's used Martin of the Trans-Ocean Company before, and another man from Digby's, but from the look of those reports "—she smiled—"the English wasn't too good—I'd say he got Windemere Nikolls of Callaghan Investigations to do them for him."

"That could be. Get on to Nikolls and find out if he did the job for Vanner. If he says yes, say I'll 'phone him tomorrow and make an appointment. I'd like to talk to him."

"Very well, Mr. O'Day. I'll get through at once."

O'Day walked round to the barbers. Whilst they were cutting his hair he made up his mind what he was going to do.

When he got back to the office at twelve o'clock, Miss Trundle said: "The Sable Inn is a two star A.A. inn. It's just off the main road between Totnes and Dartford—quite easy to find because the A.A. say if you keep to the main road there's a notice-board when you come to the turning that leads to the inn. If you drive at your usual rate it ought to take you about five and a half hours."

O'Day said: "O.K. Did you get in touch with Nikolls?"

She nodded. "It was Nikolls did the job for Mr. Vanner. I told him you'd give him a ring tomorrow; that you wanted to talk to him. He said he'd be glad to see you."

O'Day sat down on the typing table. He said: "Nellie, listen to me. I expect you've noticed a certain atmosphere in this office for the last three or four months."

"I'm not dumb, blind or silly," said Miss Trundle. "You mean Mrs. Vanner?"

"I mean Mrs. Vanner. I'm going away. I may be back some time tomorrow. I might be longer. Play things along while I'm gone. If you can, find out where Vanner is. If Mrs. Vanner should come to the office by any chance, tell her I'm away; you don't know where I am or when I'll be back. Have you got that?"

She nodded.

He went on: "There's something else. You remember Macguire—the officer in the special branch who was doing liaison work with American Intelligence details over here during the war? Get in touch with him. Make it a personal thing. Say that I'd be very glad if he'd ring my flat tomorrow night and, if I'm not there, try each day till he gets me. I want to talk to him particularly."

"Very well, Mr. O'Day."

"And get me some of those old business cards," said O'Day.

Miss Trundle opened a drawer; took out a small box. She opened it; dropped the cards out on to the palm of her hand; gave them to O'Day. He went through the little pile of cards, selected one which read:

MR. JOHN SHERIDAN,

14 Marlows Road, London, S.W.5.

Legal enquiries.

Divorce Investigations.

He said: "This one will do." He put it in his pocket.

He picked up his hat; walked to the door. "I'll be seeing you. Don't do anything that I wouldn't like to see reported in the public prints!" He grinned at her; closed the door; went down the stairs.

Miss Trundle thought she didn't know whether she liked him very much or whether he was just a rather attractive man who'd bitten off more than he could chew. For a moment she thought she didn't care very much, after which she qualified the idea. She thought that biting off more than you could chew wasn't a bad idea if you eventually managed to chew it! She thought O'Day would eventually chew it. He always did. Quite a man O'Day, Miss Trundle thought—even if he could be very annoying at times.

She shrugged her shoulders. She said: "What the hell!" Then she went back to work.

IT was just after six when O'Day stopped the Jaguar in the

attractive parking space before the Sable Inn. He got out of the

car; stood looking at the hotel. A half-timbered building, it lay

well back from the side road. At the sides and in the rear were

well-kept gravel paths and shrubberies. There were no other cars

parked in the courtyard.

O'Day went in. On the other side of the large and comfortably-furnished hallway was the reception office. He went over.

He said: "My name's Sheridan—John Sheridan. I'd like to see the manager."

The girl at the reception desk looked him over carefully. She said: "Could I tell him what you want to see him about?"

O'Day grinned at her. He shook his head. "It's confidential."

She said: "I'll let the manager know you're here, Mr. Sheridan." She went to the telephone at the rear of the office; came back; said: "Would you like to go along and see Mr. James? His office is on the right of the passage-way on the other side of the hall."

O'Day nodded. "I'd like to stay the night," he said. "Could you arrange that?"

"Of course." She smiled pleasantly at him.

O'Day crossed the hall; found the door on the right of the passage-way. He went in.

James, the manager, was sitting at his desk doing accounts. He said: "What can I do for you, Mr. Sheridan?"

O'Day gave him the card. James raised his eyebrows.

He said: "We don't get a lot of this sort of thing here." He smiled at O'Day.

O'Day said: "Maybe not, but this place looks attractive enough for any co-respondent to pick." He went on: "About three or four weeks ago a lady—I'm not quite certain about the name—stayed here. I think she probably wrote for a reservation for herself and her husband. You made the reservation and she arrived fairly late. I think it's quite possible that the night porter may have been the only person on duty. She told him that her husband would be arriving later; then she went up to her room. I've an idea that the husband arrived and managed—by picking his time carefully—to get up to the bedroom without being seen by the night porter. And when he got up the next morning the night porter was off duty. I think it's quite possible that nobody remembers what he looked like. I wonder if you could help me?"

The manager said: "I'd like to do anything I could, of course." He hesitated. "But this thing isn't awfully good publicity for us, Mr. Sheridan. This is an old-fashioned hotel and—-"

O'Day put his hand up. "I'll make you a promise, Mr. James. You give me the information I want and I'll see that this place is kept out of it. You understand that if nobody can give definite evidence about having seen the gentleman—and I think it's very likely that nobody will be able to, because this thing was played very cleverly—then it wouldn't be any use asking anybody here to give evidence. In other words, I'd have to look elsewhere. But what I want to do here is to ascertain, purely for my own use, that the parties did stay here."

The manager said: "All right, Mr. Sheridan. If you keep us out of it I'll do what I can for you. What would you like to do?"

"I'd like to talk to the night porter."

James said: "Well, you can't do that yet He comes on at about ten o'clock at night. But"—he smiled—"if you like to go down to the public house at the cross roads—the Green Apple—I'll bet you a shilling you'll find him in the private bar. He spends most of his off time there. His name's Mellins. You can't mistake him. He's tall and thin and grey. He looks very depressed even if he isn't."

O'Day said: "Thanks a lot. Maybe we can have a drink together later. I'm staying here tonight."

James said: "I'll be glad to see you."

O'Day went out. He asked the girl in the reception office to have his bag sent up to his room. He walked down the road towards the cross roads.

As he went into the Green Apple he thought that a great deal depended on Mellins, the night porter much more than Mellins would ever guess.

He found that worthy on a settle, a pint pot in his hand. There was only one other person in the private bar. O'Day sat down beside Mellins. He opened his note case; produced a five-pound note. He folded it carefully between his fingers.

He said: "Mellins, I've just left Mr. James. I'm making some enquiries about some people who stayed at the inn three weeks ago. He said you'd give me all the help you could."

He handed over the five-pound note. Mellins took it as a matter of course. He looked more depressed than ever as he stuffed the note into the pocket of his waistcoat.

He said: "Would you be meaning that pretty lady?"

"That's the one," said O'Day. "She's striking, isn't she? Did she look like this?" He described Merys Vanner.

"That's the one," said Mellins. "A rare piece, Mister... I'm telling you!"

O'Day said: "So you remember all about it?"

The night porter nodded. "I remember her... I remember her because it's usually the man who gives me a tip, but she looked after me. Two pounds she gave me when she came here and two pounds when she went."

O'Day said: "You didn't see her husband, did you?"

Mellins shook his head. "I go off at eight o'clock in the morning. And I didn't go back after I went out to take the note for her down to the garage on the main road."

"What note?" asked O'Day.

Mellins said: "Well, she came to the hotel between eleven and twelve, I'd say, and she signed the register and said her husband would be coming along later. She said he had some business in Totnes. Well, the reservation was made for them, so I took her upstairs; carried up her bag."

O'Day asked: "How did she arrive?"

"She came in a hired car from Totnes. Then about midnight she called down to me and asked if I could make her some tea. So I went down to the kitchen. We never lock the doors here at night. There's nobody around these parts and nobody ever comes in. So I reckon he arrived while I was making the tea, because when I came up I saw the car parked outside. When I took the tea up he was in the bathroom, so I never thought anything about it at the time."

O'Day said: "What about the note?"

"I'll tell you," said Mellins. "The next morning the chambermaid comes down about a quarter to eight. She's got a note from the gentleman. He wants me to go to the nearest garage and get 'em to pick up his car—clean the plugs, do the tyres, put water in, do some other repairs and put ten gallons of petrol in. The coupons was pinned to the note. He told the garage just what he wanted 'em to do. There was two pounds with it. So I went down to the garage when I went off; gave them the note."

"Then you never saw the husband?" queried O'Day. "Did anybody see him?"

Mellins shook his head. "Not as far as I know. That'd be easy because the day porter's always busy doing something or other. Maybe when they brought his car back he just went out and got into it. She could pay the bill and join him. So nobody'd see him. It's easy in a place like this."

O'Day nodded. "One mother question. What was the garage you took the note to?"

"Chaloner's," said Mellins. "You go down to the main road and you turn left towards Dartmouth. It's fifty or sixty yards down the road—just a couple of shacks, but since the war young Chaloner's been doing repairs. He's pretty good. He was in one of them motor units in the army."

"What time does Chaloner's garage close?" asked O'Day.

"Oh, any time... they're usually hanging around there until half-past seven or eight o'clock. But if they're shut and you want to talk to them they live next door in the cottage."

"That's fine," said O'Day. "Let us have a drink...."

After a second whisky and soda, O'Day left the Green Apple; walked down towards the main road. He found Chaloner's garage and young Chaloner at work in the workshop.

Young Chaloner remembered the incident very well.

"We don't often get a call to go and pick a car up," he said. "Usually they come here. We had a note about what was to be done to her. She was a nice car. I had quite a bit of trouble finding things out about her."

"What make of car?" asked O'Day.

"An American left-hand-drive Buick," said Chaloner. "A new one. She hadn't done more than six or seven thousand miles. I fixed her up; took her back and left her outside the Sable. I left the keys in the office."

O'Day said: "You wouldn't have that note, would you—the instructions that were sent down as to what you were to do to the car? If you could find that note," he added with a smile, "it'd be worth five pounds to me."

Chaloner rubbed his hands on some cotton waste. "We always spike 'em. Anything like that. We got a spike in the shop. Maybe it's there. There aren't too many of 'em. We don't do enough business." He grinned ruefully at O'Day.

O'Day said: "Let's look, shall we?"

They went to the corner of the work-shop where a long nail was driven into the wall. A couple of dozen pieces of paper were stuck on it—-accounts, old bills—most of them oil-stained. The young man began to take them off. It was the last piece of paper.

He said: "There you are, sir, That's the easiest job I've done for a fiver for a long time." He handed the piece of paper to O'Day who put it in his pocket.

O'Day said: "Nice Work. There's the fiver. Maybe tomorrow you'd like to pick my car up and service it. It's outside the inn. Here are the keys."

Young Chaloner said: "This has been a good day for me." He grinned. "I'll go to Newton Abbot races next time and play it up a bit."

O'Day said: "Why not? Always follow your luck when it's in. So long."

He walked slowly back to the Sable Inn. He went to the reception desk. "Could I look at the register?" he asked.

The girl said: "Yes, Mr. Sheridan. Mr. James said you'd probably want to."

O'Day began to turn over the pages of the register. It didn't take him long to find it. It was twenty-two days before. It was a registration for a double room for "Mr. and Mrs. Terence O'Day."

O'Day sighed; closed the register. He said "Thanks a lot."