RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

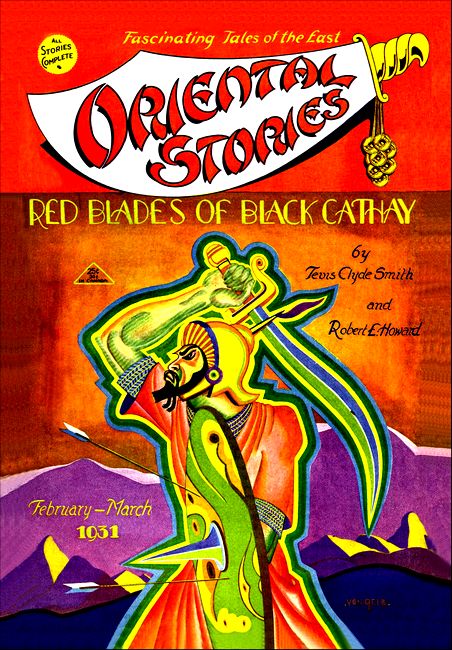

Oriental Stories, Feb-Mar 1933, with "The Dragoman's Revenge"

Otis Adelbert Kline wrote some half-dozen of these modern Arabian Nights tales, as told by white-haired Hamed the Dragoman, reminiscing of his youthful adventures when he was Hamed the Attar. One, "The Dragoman's Jest", was co-written with E. Hoffman Price, who died in 1988, and it is therefore still copyright.

The silken furnishings were disarrayed and splattered with blood.

Hamed the Attar was accused of a foul murder

he did not commit—a strange tale of Arab justice.

YOU would hear a tale, effendi? So be it. Here in the coffee shop of Silat we can find rest and refreshment.

Ho, Silat! Let there be coffee, bitter as death, black as Eblis, and hot as Johannam. And bring two shishas well filled with Jabali Latakia.

You know me, effendi, as Hamed bin Ayyub, the wrinkled and white-bearded dragoman, whose sands are nearly run. You should have seen me when, like you, I was young and vigorous. In those days I was tall, straight and strong, with handsome features, flashing eyes, and a beard black as a moonless night, Aihee! Those were the days!

Silat brews excellent coffee, effendi.

But you asked for a tale. Well then, I'll tell you of a strange adventure that befell me in my youth, when first I became a dragoman.

One day as I was walking down the Via Dolorosa, the street along which Sayyidna Isa once carried the cross, a stranger saluted me with the salam and inquired if I could speak Turkish. I replied that I could, quite fluently, whereupon he invited me into a richly furnished house near by. The majlis, or living-room, was of itself a jewel of precious beauty. The berdelik, that is, the wall hangings, were of the finest silk from the looms of Kashan, Yarkand and Kashgar, and there hung above the chief diwan a magnificent rug of Samarcand in which gold and silver threads were cunningly woven with the silk. On the floor, which was an excellent example of mosaic, were scattered the finest weaves of Kashan, Feraghan and Ispahan. And in the center of the room there played an exquisite fountain of ivory and carnelian.

After serving sherbet, pipes and coffee, my host offered me a substantial sum if I would do some interpreting for him. He and I were about of a size, and he somewhat resembled me, although I was dressed rather plainly while his apparel was so magnificent as to proclaim him a man of great wealth and high station.

"I will go and fetch the people you are to meet," he said, "but as my guests are to be men of importance, it will be well if you are more suitably attired. Permit me to find clothing for you."

So saying, he parted a pair of hangings and entered another room, from which he presently returned, bearing a gaudily colored head-cloth and a complete outfit of bright and costly raiment which, despite my protests, he politely assisted me to don.

When I was fully attired and once more seated before pipe and coffee, he said:

"I go, now, to bring my guests. But before I go let me warn you that there are certain conditions which you must fulfil. First of all, you must not leave this room under any circumstances. Second, you must pay no attention whatever to Jenene, my slave girl, who will return from the souk in a short time, even though she may act strangely and perhaps run out of the house upon seeing you. She is weak-minded and very fearful of strangers, but perfectly harmless. Do you agree to these terms?"

"I see no reason to do otherwise," I responded. "I am comfortable enough here, and weak-minded girls do not frighten me."

"Good! I will go now."

He rolled my clothing into a bundle and carried it through the curtained doorway.

"I'll leave your garments in here," he said, "where you may get them later."

In a moment I heard him pass out a door in the rear of the building.

I sat for some time in solitude, smoking and sipping my coffee while I puzzled over the two requests of the stranger—that I should not leave the room under any circumstances, and that I should speak no word to his slave girl, Jenene.

Presently I heard the rear door open once more, and the tinkle of anklets which accompanied the patter of small feet told me that the girl had arrived.

The more I pondered and listened to her moving about in the rear of the house, the more curious I became about the whole affair. At length I concluded that the fellow was merely jealous of the girl, and decided to attempt to have speech with her. Accordingly, I clapped my hands to summon her.

In a moment I heard her coming toward me through the curtained room. But before she reached the entrance she stopped and uttered a loud shriek. The curtains parted, a veiled face looked out at me, and there was wafted to me a hint of intoxicating perfume. But the curtains were quickly closed, shutting off the vision, and there was a second later a louder shriek. Then, in accordance with the predictions of her master, I heard the girl dash wildly out of the house.

I smiled as I remembered the warning of the man who had employed me, but shortly thereafter grew grave again as I reviewed in my mind the incidents that had just taken place. The girl, I recalled, had stopped and shrieked somewhere in the curtained room before she had seen me. It followed that there was something in that room which had caused her to cry out. She had shown new surprise and horror on seeing me, but I was evidently not the primary cause of her terror.

Under the circumstances, I resolved to go at once and have a look at that room. I accordingly got up, and advancing to the doorway as quietly as possible, parted the curtains.

I gasped in astonishment and horror as I saw, lying half on and half off a magnificent diwan, the body of a handsome, richly dressed young man, with the jeweled hilt of a jambiyah protruding from his chest. The silken furnishings and cushions were disarranged and spattered with blood as if there had been a considerable struggle.

I WAS staring down at this horrible sight in stupefied astonishment, when the rear door suddenly opened, and the slave girl came running in, accompanied by three armed men.

"There he is!" she cried hysterically. "There is the traitorous assassin who murdered my master!"

Alarmed, I turned to flee, but my way was blocked at this moment by two men who entered the front door with drawn scimitars.

"Surrender your weapons, dog," cried one, "if you would not be cut down in your tracks."

My own scimitar, dagger and pistols had been taken into the other room by the man who had employed me, along with my clothing. I had not noticed, as he buckled the new scimitar about me and arranged my sash, that I was wearing the curved, empty sheath of a jambiyah. The fellow had brought me no pistols.

Dropping the scimitar, which I had instinctively drawn, for I saw that it was useless to attempt to defend myself against five men, armed to the teeth, I said:

"To the argument of your many blades, I yield, but I am an innocent man. The real murderer brought me here on a pretext, in order that I might be trapped and shoulder the blame for this crime."

"O father of deceit and brother of a thousand filthy pigs, is that not your jambiyah in the breast of Zayd, who has been received into the mercy of Allah?" said one of the men. "If it fits not your sheath, then will I triply divorce the daughter of my uncle."

"And if that be not evidence enough, O lying spawn of a pestilence," said a second, "are not those blood spots on your raiment sufficient proof of your guilt?"

Several small red spots on the clothing which had been given me, and which I had not previously noticed, were now pointed out to me.

"But these are not my garments," I protested. "I was asked to wear them by the man who—"

"Enough," gruffly interrupted he who had first spoken. "Seize and bind him, men. We'll take him before the kazi."

And so, despite my struggles and protestations of innocence, I had my hands bound behind my back, and with a rope looped around my neck, was led away.

THEY led me through the souk first, to what had been the shop of the murdered Zayd, who had been a prosperous goldsmith. We quickly drew a large following of curious people, for my captors had taken every possible precaution to humiliate me. One of them walked ahead, dragging me by the rope around my neck as if I had been a haltered beast. Beside me, on each side, walked two others with naked blades in their hands. And behind us walked Jenene, the slave girl, whose lissom grace, tinkling anklets and lustrous eyes above her flowing yashmak were sufficient, of themselves, to turn the head of any man.

As we arrived at the stall of Zayd we found that it had been closed. Standing before it were three men. The first I instantly recognized as the consummate villain who had led me into the trap. The other two were the merchants who occupied the two adjoining booths, one of whom sold rugs and the other fruit and cakes.

For a moment I was blinded with rage as I saw the author of my humiliation and almost certain death standing before me, and violently endeavored to free my hands that I might throttle him. But he who held my lead-rope nearly choked me by jerking me backward.

"Who is this wild-looking person?" asked my betrayer of the man who had haltered me.

"He is a traitor to the salt—the unspeakably vile murderer of Zayd, the Goldsmith," replied the fellow. "He claims to be a dragoman named Hamed, but we doubt this, so we have brought him here to see if any of the merchants can identify him before we take him to the kazi."

"I know him!" cried he who sold the cakes. "He is Kasim ben Musa, who arrived this morning with the caravan from Damascus. I distinctly remember his black beard and the clothing he wears. He talked with Zayd for a short time this morning, whereupon the goldsmith closed his shop and went away with him."

"I also remember him, and can bear witness that it was he who went away with Zayd," said the rug merchant.

Upon hearing these words, the fellow who had employed me simulated great anger, and whipping out his scimitar, made as if he would strike off my head.

"'So, O violator of the salt, and seed of a loathsome disease!" he exclaimed, his voice quivering with feigned anger, "you have slain my pious and noble cousin! Then by my beard and the life of my head will I see that justice is done upon you here and now."

But ere he could use his scimitar the others restrained him, one of them saying:

"Peace! It were better to take him before the kazi. Full justice will be done, never fear, for there are eight of us who can bear witness to his perfidy."

"Oh, Zayd, Zayd!" said the deceitful one, now pretending great sorrow. "My cousin whom I loved as a brother! To think that you should have come to an untimely end, and by the hand of so vile and unspeakable a wretch! My grief is more than I can bear!" Whereupon he plucked at his beard, heaped dust upon his head, and rent his garments, while great crocodile tears coursed down his cheeks.

The two merchants then closed their stalls, and they, together with the trickster who had brought me to this pass, accompanied us to the audience with the kazi.

ABU TAYI, the kazi, was a venerable and learned man with an enormous turban. Among our people, the greater a man's learning, the larger the turban. Thoughtfully stroking his white beard, he looked down at the fellow who was dragging my rope, and said:

"Of what is this man accused, and who is there to bear witness against him?"

"He is accused of the murder of Zayd, the Goldsmith, O kazi," replied the fellow, "and there are eight of us here to bear witness."

"Then let us hear your testimony in order," said the kazi. "You may testify first."

Whereupon the fellow told how he had been standing in the street conversing with four friends when the slave girl of Zayd had run out of the house screaming that her master had been murdered and that the murderer was in the house. He further told how he had stationed two men at the front door, and taking two more with him had accompanied the girl through the back door, where they had caught me red-handed, my garments spattered with blood and my jambiyah still sheathed in the heart of Zayd. He then pointed out the blood spots on my clothing and displayed the bloody jambiyah which one of his companions had brought along.

The kazi then questioned his four companions, one by one, who verified his story.

After the five had testified, the slave girl came forward and told that I had come in with her master that morning and broken bread with him, and that he had sent her to the souk for supplies with which to prepare the evening meal. But on her return she had found her master murdered and me still in the house, whereupon she had summoned the five men who captured me.

The kazi then asked me if I had ought to say.

"Insofar as what the men have seen with their eyes and heard with their ears is concerned, they speak the truth, O kazi," I replied. "As for the girl, she was deceived by my resemblance to another if she thought it was I she left with her master when she went to the souk. I swear to you by Almighty Allah, Lord of the well, Zemzem, and of the Hatim Wall, that I am innocent of the crime attributed to me. If you will grant me leave to tell my story, I'm sure I can prove—"

"Enough!" interrupted the kazi. "Your own story will be heard later. At present all I want is your corroboration or denial of the stories of these witnesses. Now let us hear what the two merchants know of the matter."

Whereupon one of the merchants, he who sold cakes and fruit, stepped forward and testified that he recognized me as Kasim ben Musa, who had arrived that morning with a caravan from Damascus, and that he had seen me go away with Zayd when the latter closed his shop. The other witness then corroborated his evidence.

"What have you to say for yourself, prisoner?" asked the kazi.

"Falsehood is as smoke and fact is built on a base which shall not be broken, O kazi," I said, "and the light of truth dispels the night of untruth. This is a case of mistaken identity, planned by that lecherous consort of a mangy camel who slightly resembles me, and who came here with the two merchants to testify falsely against me. He is the real Kasim ben Musa, murderer of Zayd, and these are his clothes I am wearing."

The kazi turned to my betrayer.

"What is your name?" he asked.

"Akrashah ibn Mahmud of Bagdad," was the reply, "and cousin of Zayd the Goldsmith, may Allah be merciful unto him."

"What do you know of this matter?"

"I arrived with the same Damascus caravan as that in which this vile murderer traveled," he said, "in order to pay a visit to my cousin, on whom be Allah's clemency. But it was some time before I was able to find his shop, as I was unfamiliar with this city. When I found it, it was closed, and these two merchants told me that Zayd had departed with this malevolent malefactor. As I stood before the shop conversing with them, the girl and the five men arrived with the murderer and informed me that he had violated the salt and taken the life of my cousin, whom may Allah receive into paradise. Whereupon my bosom was constricted with sorrow and wrath, and I would have slain him then and there in the excess of my grief and anger, had not these friends persuaded me to the reasonable course of bringing him into your honorable presence. And if you judge rightly between this unspeakable villain and your servant who has suffered this great wrong, may your life span a mighty span, and may peace and happiness be multiplied unto you with each year."

"Now, prisoner," said the kazi, "tell me your story, that you may be heard before sentence is passed on you."

While the venerable Abu Tayi sat there, stroking his white beard and glaring at me with an expression which told me as plainly as words that I was already guilty in his mind, I related all that had happened since he who called himself Akrashah ibn Mahmud had accosted me on the Via Dolorosa. When I had completed my tale of the cunning and perfidy of Akrashah, the kazi turned once more to him.

"What have you to say to this, O Akrashah?" he asked.

"That not one single word of it is true," replied my betrayer. "This man is the most preposterous prevaricator I have ever met."

"O father of lies!" I said. "O sink of corruption! For this added falsehood may your tongue turn to a serpent and bite you."

"And for your brazen deceptions, O stench of an abomination," he replied, "may your beard turn to a nest of scorpions and sting you for a thousand years."

"Enough of this abuse," said the kazi. "I will now pronounce sentence."

"I swear to you by the Most Great Name that I am innocent," I said. "Spare me until I can find witnesses to vouch for me."

"Throw the prisoner into the dungeon," said the kazi, "and tomorrow at sun-up, bring me his head, that I may display it before my door as a warning to whosoever will be warned."

"Harkening and obedience," replied two burly guards, who seized my arms.

As I realized the full import of the kazi's words—that I had been sentenced to die before dawn—a cold perspiration suffused my body and my knees sagged beneath my weight, so my guards were forced to half drag, half carry me.

I WAS thrown into a dark and filthy cell with my hands still bound behind me. A jailer came, presently, bearing food and water. I implored him to release my hands that I might eat, whereupon he held his lantern before my face and exclaimed:

"Hamed! I thought your voice was familiar! What crime have you committed that you have come to this pass?"

I recognized him instantly as Ibn Khalud, a friend of my boyhood whose life I had once saved, and who was sworn to me as a blood brother.

"Release my hands, O my brother," I said, "and I will tell you my story."

He instantly opened my bonds, and then sat and listened to my story while the bread and water he had brought me stood untouched.

"It is a horrible injustice!" he exclaimed. "I will go before the Sharif himself and lay the matter before him."

"Alas!" I replied. "The Sharif went hunting yesterday, and will not return for a week."

"Then I will go to the kazi."

"That is useless, also, and would only cast suspicion on you if I were to make my escape. He already had me condemned in his own mind before half the evidence was presented. I saw it in his eyes."

"Then, by Allah, and by my head and beard, I will take the matter into my own hands, O blood brother," he said. "Ex-pea me after the last call to prayer."

So saying, he departed, leaving me once more in darkness.

IT seemed to me, waiting there in the stinking blackness, that at least a full day passed before I saw the yellow flicker of Ibn Khalud's lantern, followed by his quiet entry into my cell. He had brought with him a dark-colored head-cloth and burnoose, both of which I donned over the garments I was wearing. Then, commanding silence, he led me through many devious passageways, to a place where a rusty iron ring dangled from the ceiling. Leaping into the air, he grasped the ring, whereupon it slowly descended on the end of a thick chain, and a slab in the floor ahead of us rose, revealing stone steps leading downward.

We descended die steps, whereupon Ibn Khalud moved a lever at the base, and the slab came down, closing the opening above us. It seemed to me that we penetrated deeper and deeper into the bowels of the earth. Water seeped through a thousand crevices in the walls, and dripping and trickling to the floor, combined with the moss, mold and slime, to make our footing exceedingly slippery. We presently came to the foot of another stair, where my blood brother, after locating the lever, hooded his lantern. Then, by working the lever, he moved a great slab of rock at the top. We climbed the stairs and emerged into the clear night air. "Leave the city at once," he counseled.

"I go, now, to drug the guards with bhang, so it may appear that you escaped through the courtyard while they slept. Salam aleykum."

"May Allah reward you for this good deed," I replied. "Was salam."

With that I left him, and soon recognized the district. I had been let out through a secret passageway in the city wall not far from my own home. Making my way to it as quickly as possible, I entered my dark and lonely house, struck a light, and sat down to think. I had no intention of leaving the city if this might be avoided, but on the other hand, there would be a hunt organized for me as soon as my escape had been discovered, and sooner or later some one would be sure to recognize me.

I have ever been a man of action, and it was not long before a plan occurred to me.

In my house, carefully put away in a great chest, were the clothing and jewelry of my mother, who had been received into the mercy of Allah. As she had been a rather large woman, I knew that I should be able to wear her garments without trouble. Quickly attiring myself in black, and covering my countenance with a white face-veil, I stood before the mirror in the bent attitude of a very aged person, and saw that, to all appearances, I was a very old woman. As I have ever been an adept at changing the tones of my voice, I knew that it would be a discerning person indeed who would penetrate my disguise.

To conform to the plans I had formed, I selected from among my mother's jewelry a necklace of most exquisite pattern and craftsmanship, and of considerable value. Taking this with me, and also a goodly quantity of bhang, I closed my house once more, and arriving at the Via Dolorosa, turned my steps to the house of Zayd.

Upon my arrival I glanced up and down the street, and on seeing that it was deserted, swung myself up onto the balcony which jutted out beneath the front windows, and looked within.

Zayd, having died in the morning, had been buried that afternoon, as was the custom in those days when embalming or refrigeration was unknown. This I had foreseen, and also, that Akrashah would most probably be alone with the slave girl at this hour. But I wanted to make sure.

My hopes were instantly realized when I saw them both seated on the main diwan in the majlis, sipping wine in violation of the sacred teachings, and eating cakes and fruits while the villain made love to her, imploring her to remove her veil. She coyly refused, yet did not seem at all displeased.

Descending noiselessly from the balcony, I rapped on the door. Presently there was the sound of soft footsteps and the tinkle of anklets, and the slave girl opened the door.

"Peace be upon you, mother," she said, politely. "What can I do for you?"

"And upon you, my daughter, may the peace of Allah descend. I must have instant speech with your master, Zayd," I replied, in the quavering tones of an old hag. "Will you take me to him?"

"My master Zayd has, alas, been taken to the bosom of Allah Almighty," she replied. "But come in, mother. His cousin and heir, Akrashah, who is now my master, will no doubt see you."

AS I stepped through the doorway I pretended to a great weakness and tottered so unsteadily that Jenene permitted me to lean on her shoulder for support. When I approached him, Akrashah looked up at me from his seat on the diwan as if in considerable annoyance, whereupon I tottered the more, and made as if I would fall. The wine and glasses, I noticed, had been concealed.

"What is wrong, Jenene?" he asked. "Is the old woman ill?"

"She is very weak, and craved speech with your cousin, O my master," replied the girl, "so I brought her to you, as she says it is a matter of great importance."

Akrashah reluctantly placed a cushion for me, and Jenene solicitously helped me to be seated.

"Brew coffee at once, Jenene," ordered Akrashah. Then he said to me: "We shall have food and drink for you in a hurry."

"I stand not in need of coffee or food," I replied, quaveringly, "having just dined with a friend. However, I have a giddiness which might be allayed by a little wine. Although I am a true moslemah and would not drink wine for the purpose of becoming intoxicated, I find it a ready cure for this dizziness which often assails me."

"Did my cousin, Allah rest his soul, have any wine in the house, Jenene?" asked Akrashah, with pretended innocence.

"He kept a little for medicinal purposes," replied the girl.

"Then bring wine," he said, "and three cups, for our breasts are straitened by the calamity that has befallen this house and our hearts hang heavy with sadness, so we may drink a little wine to broaden them and to hearten ourselves."

After each of us had drunk a glass of wine, and our goblets had been replenished, I brought out the necklace.

"It was about this piece of jewelry that I came to consult Zayd," I said. "Although it is a family heirloom, and unless there were great need I would not part with it for any sum, I find myself destitute and forced to sell it. Knowing Zayd for an honest tradesman I came here, hoping to receive its value, for I have no idea of its worth."

Akrashah took the necklace in his right hand and slowly drew it across the back of the left. I saw his eyes light up with cupidity and avarice as he noted its great beauty and value.

"Oh, master!" exclaimed Jenene. "Is it not beautiful?"

"It is well made," was his reply, "but the materials are not very costly. The jewels are imitations, and the settings plated. I'm afraid I can't offer much for it."

"Nevertheless I would give much for the trinket," said Jenene. "Perhaps if the master does not want it you will sell it to me, mother."

"It may be, my little Jenene," said Akrashah, "that I will buy it for you, seeing you are so set on having it. But I warrant you I shall not pay any outrageous price for it."

"You know the worth, good sir," I said. "Name the price, then, and I will sell it to you and depart."

"Nay, mother, you name it," he replied, refilling my glass and winking slyly at Jenene. "After all, it is your property."

"Very well, then," I replied, and named a price which I knew to be about half the value of the necklace.

But Akrashah was as grasping as he was villainous, and laughing at the price I asked, offered me about a tenth of the amount. Thereafter we haggled spiritedly until the bottle of wine was entirely consumed and a second had been brought out. I noticed, in the meantime, that Akrashah and Jenene, who had evidently been drinking much wine before I arrived, were becoming quite intoxicated. Concluding that it was therefore time to do what I had planned to do, I palmed a bit of bhang and slyly dropped it into the glass of my betrayer. A few moments later I succeeded in dropping a piece into the glass of the slave girl.

It was not long before the drug got in its work, and both were lying insensible before me. I had taken care to give each of them a good heavy portion, so their slumber would be long.

But I still had much work to do, and that quickly, before the morning should dawn, so I swiftly divested myself of not only the garments of my mother, but the raiment which my betrayer had put on me that morning. I then undressed him, and after donning his clothing, dressed him in the blood-spattered garments he had worn when he committed the murder.

Upon going through his pockets I found that he was not Akrashah, cousin of Zayd, but was really Kasim ben Musa of Jerusalem, late of Damascus, who had prepared forged papers and committed the crime in order to thus gain the possessions of the wealthy young goldsmith.

As soon as I had determined these things, I wrapped the insensible Kasim in the cloth covering of the diwan and shouldering him, carried him out into die street. By singular good fortune I did not meet any one on the way to my destination, which was the wall of the courtyard of the prison in which I had been confined.

There, in the shadow of the wall, I unwrapped the limp Kasim. I then hoisted him to the top of the wall, and pushed him so that he rolled over into the courtyard. At the sound of his falling body I heard a guard running, and knew that he would soon be discovered.

Rolling the cover of the diwan into a bundle I departed noiselessly.

Upon coming to the house of Zayd, I found Jenene still lying in a stupor. Replacing the diwan cover, I took the clothing of my mother and returned it to my house. I then went back to the house of Zayd, and after brewing some coffee and lighting a shisha, waited for Jenene to regain consciousness.

She did not awaken until long after the dawn prayer. Seeing me attired in the clothing of Kasim, and still half dazed by the wine and bhang, she took me for her master without question. I gave her some coffee, which seemed to refresh her greatly. Then she remembered the old woman, and asked what had become of her.

"The old mother of a calamity became very drunk," I replied, "and continued to ask more and more money for the necklace which I wished to secure for you. In the meantime, it seems, the wine went to your head, and I saw that you had fallen asleep. But I was determined to get this necklace for you at any price, and finally paid the old hag twice what she had originally asked. She then took her departure, and I waited for you to awaken, that I might acquaint you with the news."

So saying, I handed her the necklace which had so intrigued her fancy.

"Oh, master!" she cried. "So splendid a present is far more than I deserve!"

"I have no doubt," I replied, "that your own beauty will so outshine that of the precious stones as to make them appear like pebbles."

"Last night," she said, "you asked me to unveil and I refused you. But I may not refuse so generous and kind a master longer. Permit me but a few moments in my apartment and I will comply with your request."

So saying, she rose and went into her apartment, while I burned with impatience to see what beauty her robes and veil concealed.

LIKE any woman who wants to look her best, Jenene was absent for a long time. Presently, however, she came through the curtained doorway unveiled, and wearing a filmy, diaphanous garment that revealed every line of her beautiful young body.

"Do I please you, master?" she asked, archly.

The sight of her beauty then and there interposed between me and my wits, for never on earth had I imagined there could be a damsel to compare with her. She had a mouth magical as Solomon's seal, hair blacker than the night of estrangement to a lover, a brow white as the crescent moon at the Feast of Ramazan, cheeks like the blood-red anemones of Nu'uman, breasts that were twin pomegranates of enchantment, and a graceful form and carriage that would put to shame a branch of ban, stirred by the soft breezes from the Valley of the Zarab Shan.

"You are magnificent," I said. "I glorify Allah, the one and true God, who has given you to me."

Rising, I took her in my arms and kissed her until she grew faint and could not stand, whereupon I carried her to the diwan.

And so it came about that I inherited the wealth and lived in the house of Zayd, but greater and more precious by far than both of these, had their value been increased a thousandfold, I inherited Jenene, who loved me with a love that was past all understanding, until the destroyer of delights and the sunderer of societies took her from me forever.

But to return to that first day with Jenene. In the afternoon she went to the souk to buy food for our evening meal. When she returned, she said:

"I have just seen a horrible sight, O beloved master. Impaled on the point of a lance stuck in the ground before the house of the kazi, I saw the severed and bloody head of that foul murderer, Kasim. It is said that he drugged two guards and attempted to escape over the wall, but fell, and was caught and executed."

"Allah is just," I replied. "Alhamdolillah! Praise be to Allah, Lord of the Three Worlds!"

Ho, Silat, bring the sweet and take the full.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.