RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

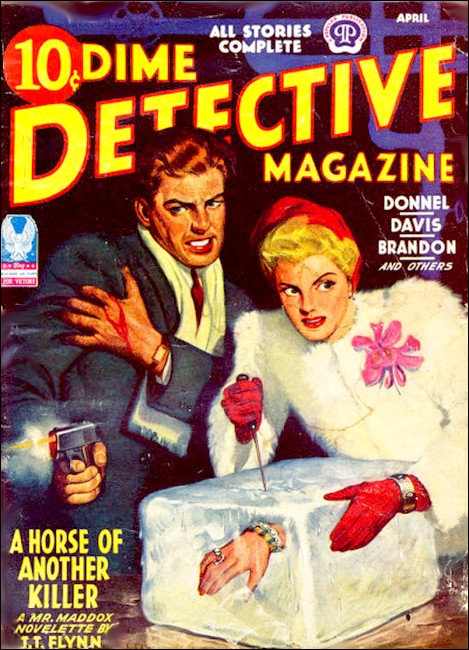

Dime Detective Magazine, April 1943, with "Too Many Have Died"

Tracy threshed on the ground, trying to get hold of the gun.

The grisliest mass-murderer whoever killed 500 men at one fell slug-swoop was among the guests, incognito, at the party the millionaire threw for Peter Tracy, brilliant engineer, who was condemned to join the death-list too unless he could identify the killer before he struck again...

PETER TRACY stepped out through the arched doorway of the Administration Building and took a big breath of fresh air, because he needed it. He was having hallucinations. He was beginning to see faces, faces and more faces going around in a sort of a nightmare whirlpool. All of them were young faces—awed and eager and anxious to imbibe of the knowledge the said Peter Tracy was supposed to ladle out to them in graduated and digestible doses.

He had been seeing the faces—actually and in person, one at a time—all morning and afternoon. The faces, when properly attached, belonged to students of Boles University, and Peter Tracy was a member of the faculty of same, much to his surprise.

He was chubby and slightly below medium height, and he had a round, ageless face of his own and eyes that peered through rimless octagonal glasses with bland innocence. He wasn't wearing a hat, and his hair was mouse-colored and had a stubborn little clump that jutted out behind like a plume in spite of brushes, barbers, and goose grease.

Now he took a limp and wrinkled pamphlet out of his coat pocket and ran one forefinger down the columns on a page until he came to the following:

Eng. Adv. San. Prac. (Tracy)... MWF 10... 3

This was not Esperanto or even double-talk. It was the University's way of informing students that they could take Practical Advanced Sanitary Engineering from a man named Tracy on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 10 o'clock in the morning and get three credits for doing it, if they passed. Tracy turned the page and found another item.

Prefab. Const. Tran. (Tracy)... TTh 10... 2

This one was easy and meant that the same Tracy would tell you all about the construction and transportation of prefabricated units on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 10. Tracy sighed and looked on another page.

Dia. Mon. Sys. Mod. As. (Tracy)... MTWThF 11 ... 5

This said that the man Tracy was ready to instruct you in Modern Asiatic dialects and monetary systems every day in the week, except Saturdays and Sundays, at eleven o'clock and that you could have five credits if you could stand it.

Sanitary Engineering, pre-fabricated construction, and Asiatic languages and money do not seem, at first glance, to be very closely related to each other. However, if you were building some barracks in an impenetrable swamp surrounded by impassable jungle in the middle of an ocean full of Japanese submarines, you might find they would all come in pretty handy. At least the United States Army thought so, and hence Peter Tracy was a professor.

He sighed again and put away the pamphlet and then went down the broad steps and strolled jauntily across the twilight quiet of the campus square. The air was fresh and cool against his face, laden with the drowsy tang of burning leaves. Tracy began to whistle loudly and badly. He was one of those people who can't carry a tune, but he didn't know it. He believed he had an excellent tonal and rhythmic sense and had often regretted he hadn't taken up music as a career, particularly when bombs dropped on his construction projects.

HE crossed the boundary of the campus and turned into

Melrose Avenue, alive with the pallid early-evening glow of neon

signs and traffic that squawked and squeaked and moved jerkily.

Students of all kinds walked fast alone and talked fast in groups

that eddied and swirled along the sidewalks.

Tracy went three blocks and turned again into the shadowy peace of Chaucer Street. The houses were old here, withdrawn in their dignity behind long lawns and thick shrubbery, and Tracy had the impulse to nod at them approvingly. He liked them. They had been here a long time and endured a lot, and they were still going strong.

There was a man standing in front of the fifth house from the corner. He was holding a broom as though he were making up his mind what and where to sweep with it when he got ready to sweep but not right away. He was thin and stooped, and he wore a tweed jacket and khaki pants and a gray hat with a hole in the side of the crown. He had a dour, furrowed face and a ragged brown mustache.

"Hello," he said. "You're from China and way-points, and your name is Tracy, ain't it? I'm Bagby. I'm the fireman and janitor and what-the-hell around the joint here."

"Glad to know you," said Tracy.

Bagby nodded. "Sure. Tracy, have you ever been in jail?"

"Oh, from time to time," Tracy said.

"I mean, seriously. I mean, did you ever serve time in a penitentiary for a felony or like that?"

Tracy shook his head slowly. "Not that I recall."

Bagby scratched his mustache. "Well, do you know a little slim fella about five feet four with a round face sort of on the greasy side and a black sheik's mustache and a dimple on his chin? He's got nice brown eyes and a kind of bashful smile, and he walks real dainty—like a cat with its feet wet."

"Don't know him," said Tracy.

"You could get to know a fella like that very easy in a penitentiary. That's where them kind of fellas spends lots of their time. That's why I asked you was you ever in one. He knows you."

"Could be," Tracy admitted.

"He don't know you well enough to suit him, though. He was askin' me questions about you."

"Was he?" Tracy asked idly.

"Sure. He didn't hear nothing that'll keep him awake nights. You honest don't know him?"

"No."

"Then you better find out what he wants before you run across him by accident. He's a shooter."

"Shooter?" Tracy repeated.

"Yeah. That don't necessarily mean he has to have a gun to operate. He'll use a knife or a lead pipe or anything else that comes handy. He's on the dope, too. Oh, he don't go around sniffin' and twitchin', but he uses a little bit to steady him when he thinks he needs it."

"Sounds like a very charming person," Tracy observed.

Bagby leaned on the broom and eyed him speculatively. "You got me bothered, Tracy. You don't look to me like you're speedy enough to play pitty-pat with this bird. He's a nasty customer, and you walk around with an awful slap-happy expression on your puss. You ain't by any chance as dumb as you act, are you?"

Tracy nodded soberly. "I'm afraid so."

"Oh," said Bagby, with a sort of surprised interest. "I see. Well, so I ain't gonna worry about you no more. You just go ahead and skin your own skunks. Good-bye, Tracy."

"Good-bye, Bagby."

Tracy went on up the walk toward the house that lolled squat and gloomily comfortable behind a guard of four oak trees. Leaves tapped and rustled dryly over him as he climbed the steep steps to the porch. The colored glass panel in the door gleamed cheerily orange and blue, and he stepped into the warmth of a narrow, dark-paneled hall. The fluted strips of glass that hung from the old-fashioned chandelier moved and tinkled a soft welcome to him.

STRONGER light came out of the square doorway that led to

the study, and as Tracy walked quietly past it, a rounded and

sonorously majestic voice said: "Good evening, Mr. Tracy."

"Good evening, Mr. Montgomery," Tracy said.

He went up the narrow stairs and along a hall carpeted with a faded red runner. Unlocking the last door on the south side, he went into his room and closed the door again before he turned on the light. He looked slowly around. Everything seemed normal, and there was no-one else in the room now, but someone had been and just recently. The odor of perfume was quite noticeable. It smelled like expensive perfume.

Tracy's eyes focused suddenly on the heavy walnut dresser. There was a gun lying on top of it in the center of the stiff linen doily that served to cover some of the scars and cigarette burns in the dark wood. The gun belonged to Tracy, but it didn't belong on the dresser, and he hadn't put it there.

He walked over and picked it up thoughtfully. It was an automatic pistol, and it looked like a German Luger, but it wasn't quite. It was a Japanese Nambu 7 millimeter officer's model. It wasn't loaded. Holding it in his hand, Tracy opened his flat steamer trunk and looked inside. His clothes were all there and in order, but not in the same order as he had left them.

Tracy dropped the pistol on top of them and closed the trunk. Turning out the light, he left the room. The hall was still empty, but he could hear a radio playing in one of the other rooms. He walked softly down the stairs.

"Do come in and join me," said the rounded, sonorous voice.

Tracy entered the comforting brightness of the study. It was a square room, vast and high-ceilinged, lined with shelf after shelf of books that looked as though they had been read and liked and read again. There were two deep leather divans with lamps arched over them and matching leather chairs and a thick-legged table piled with neat stacks of magazines.

The man with the voice was lying flat on one of the divans with a newspaper spread over his face. He made a neatly graduated mound there, coming to a gently rounded prominence in the middle and sloping off at either end. He wore black, pointed shoes and gray spats. He blew on the newspaper, and it puffed up with a sudden crackle, floated away like a parachute, and then subsided reluctantly on the floor.

"Dinner will be served shortly," he said. He had a globular head as hairless and smooth as an egg and blue eyes that looked like lacquered, polished buttons.

Tracy sat down and stared at him in silence.

"Mr. Tracy," said the fat man, after a long moment, "I sense a certain latent hostility in your manner. Has something displeased you?"

"Yes, Mr. Montgomery," said Tracy. "Someone searched my room while I was gone."

Montgomery pursed his lips. "I see. That sort of thing can be very annoying when carried to extremes. Do you think I'm the guilty party?"

"I don't know. Are you?"

"No," said Montgomery. "I don't claim, you understand, that I would be above such a thing if I thought there'd be any profit in it, but in this case I'm entirely innocent. I give you my word. Are you convinced?"

"No."

Montgomery sighed. "I see I shall have to resort to logic and deduction. Mr. Tracy, I am the proprietor of this rooming and boarding establishment, and as such I have an interest in maintaining its pure and spotless reputation. That would suffer sadly if I did any unauthorized tampering with the possessions of my paying-guests. Besides, if I had searched your room, you wouldn't have found it out."

Tracy merely stared at him.

Montgomery sighed again. "You seem a reasonable person, noticeably lacking in frustrations and complexes, but I fear your residence in the mysterious East has made you unduly suspicious unless you are an international spy or saboteur or some such. Are you?"

"No."

"Then why should anyone want to search your room?"

"Why should janitors want to tell me fairy tales?"

"Bagby?" Montgomery inquired. "That was no fairy tale he told you. There was a man here inquiring about you in a suspiciously casual manner. Also, Bagby is a very good judge of a certain type of character. He used to be a professional criminal himself. He used to blow safes until as a result of a slight miscalculation he blew himself through a brick wall and retired from business. Bagby says the man inquiring for you was a killer—a man who hires himself out to do murder for a price. Do you know him?"

"No."

"Do you have any enemies?"

"Yes. A couple of hundred million of them."

Montgomery smiled. "You mean dear Adolf and his various assistant villains? I was referring to personal enemies who would be likely to lay out a couple of hundred dollars to have the pleasure of reading your obituary."

Tracy shook his head. "No. I'm such a nice fellow that everyone who knows me loves me dearly."

"You'd better count up again," Montgomery advised. "Criminals never work for fun."

"How do you know?"

"I was a criminal lawyer—I use the adjective advisedly—until the evil machinations of my jealous rivals in business resulted in my disbarment. It was a lamentable miscarriage of justice. I had not, as was alleged, bribed the jury in this particular case. I had no need to. I had bribed the witnesses for the prosecution, but you can understand why I couldn't enter that fact as a defense.... Won't you come in and join us, Miss LaTru? It's rather drafty out there in the hall."

A GIRL lounged into sight and leaned in a lazily graceful

way against the doorway. Her mouth was very red and

moist-looking, and she held a cigarette with an inch-long ash

expertly in one corner of it, squinting one heavily mascaraed eye

against the smoke. She was slim and quite tall for a girl, and

she wasn't more than twenty-one or twenty-two. She had brassily

golden hair that hung to her shoulders in a long sleek bob. In

spite of all the camouflage, she was really very pretty.

"Hi, Counsellor," she said. Her voice was low and hoarse.

"Good evening," Montgomery said. "This gentleman is Mr. Peter Tracy. This is Miss Gloria LaTru, Mr. Tracy."

"Hello," said Tracy thoughtfully. Gloria LaTru was wearing perfume—a lot of it. It was the same kind of perfume the person who had searched Tracy's room used.

Gloria LaTru took the cigarette out of her mouth and snapped the ash on the rug. "This ain't so good, Counsellor. This bird looks pretty young and spry, and he ain't exactly repulsive, either."

"Thanks," said Tracy. "Shall I take a bow?"

"Never mind," said Montgomery. "Miss LaTru, I don't like to appear unduly dense, but just what has Mr. Tracy's appearance or lack of it got to do with either you or me?"

"Pappy picked this joint because it was a faculty boarding house and supposed to be full of old fuddie-duddies," Gloria LaTru explained. "He ain't gonna like it when he finds out Pete flops here."

"I suppose by Pete you mean Mr. Tracy," Montgomery said. "But who is Pappy?"

"My li'l ole sugar-daddy."

"Oh," said Montgomery.

Gloria LaTru nodded at Tracy. "It ain't that I got anything against you, Pete. In fact, I think you're kinda cute in a negative way, but li'l ole Pappy is awful jealous. He gets himself all in a dither if I just smile at anybody that ain't at least a hundred years old."

Montgomery said: "This Pappy has some—ah—control over your actions?"

"Well, sure. I told you he's my li'l ole sugar-daddy. He's putting up the dough for me to go to college with."

"Why?" Tracy asked, interested.

"To learn me to be an actress. Ain't that a sketch, kids? Can you picture me as an actress? Man, I'd sure panic the populace. But ever since Pappy dug me out of the pickle factory, he's been at me to get refined, and I guess maybe this is about the least painful way to do it. I think maybe I'm even going to like it around here."

"I'm sure you will," Montgomery told her, "if Pappy allows you to stay. If he does, I'm afraid he'll have to put up with Mr. Tracy's presence on the premises. You may inform him that appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, Mr. Tracy is a bona fide member of the University's faculty."

"Yeah?" said Gloria LaTru. "What brand of bilge do you give out with, Pete?"

"Just junk and stuff," said Tracy.

"Hardly that," Montgomery denied. "Have you ever heard of the American Volunteer Group, Miss LaTru?"'

"Nope."

Montgomery sighed. "Have you ever heard of the Flying Tigers?"

"Oh, you mean those babies that used to fly against the Japs before Pearl Harbor? Sure! You mean, Pete is a flier with that outfit?"

"It no longer exists," said Montgomery. "It is now part of the United States Army Air Force. But there were other people besides fliers in the Group Mr. Tracy was one of them. He is an engineer—a specialist in construction and transportation and sanitation and such matters. He is now instructing would-be officers in the University under the sponsorship of the War Department."

"Gee," said Gloria LaTru. "He don't look smart enough for all that, does he? Did you ever kill any Japs, Pete?"

"I never saw any," Tracy answered, "closer than two miles away—straight up."

"You got bombed, huh?"

Tracy nodded. "Every afternoon at two sharp."

"Were you scared?"

"You're damned right," said Tracy.

A thin, small, discouraged-looking youth looked in the doorway and stated sadly: "Dinner's ready about now."

"Mr. Penfield has not come down yet, Samson," Montgomery told him. "Will you call him, please?"

"Is Penfield the bald little guy who tip-toes through the halls?" Gloria LaTru asked. "Looks something like a mouse?"

"He is small," Montgomery said.

"Also screwy," said Gloria LaTru. "He squeaked at me."

"Mr. Penfield is very shy," Montgomery told her.

"He sure shied at me. Let's feed. Give me your flipper like in society, Pete."

She took Tracy's arm in a warmly possessive grasp and pulled him toward the door.

THE table was long and narrow under a huge chandelier that dripped a cascade of dusty crystal pendants. Gloria LaTru and Tracy sat opposite each other in the middle, and Montgomery and Penfield sat at either end.

"It seems a little lonesome now," Montgomery said. "Things will liven up when Treat and Totten and the rest return from their vacation and the semester starts."

"Who are Treat and Totten?" Tracy asked.

"They are research assistants in anatomy."

"In what?" Gloria LaTru demanded.

"Anatomy."

"I'll keep an eye on them," she promised. "They won't get away with any home work around me. Say, Benny, what do you do for a living?"

Penfield was caught with a mouthful of potatoes and pork chop, and he made pitiful little choking noises and blushed fiery red. He was a small, squeamish man, bald except for a kewpie-like spiral of colorless hair on top of his head.

Montgomery came to his rescue. "Mr. Penfield is an assistant professor in the history department. He's a noted authority on early Grecian folk-lore. He has written several texts that are used extensively."

"Gee, an author!" said Gloria LaTru. "Will you autograph me a book, Penny?"

"Gl-gladly," said Penfield, regarding her with a sort of dread fascination.

Samson, the discouraged-looking youth, came in to remove the dishes. He wore thick glasses, and his trips back and forth from the kitchen had fogged the lenses until they looked like twin blacked-out portholes.

"Hey, Goliath," Gloria LaTru said. "Can you see through those cheaters when they're gummed up that way?"

"No," Samson answered.

"Then why don't you clean 'em off?"

"There's nothing around here I care to look at," said Samson, returning to the kitchen.

"Wheel," said Gloria LaTru. "I got snubbed, I bet."

"Samson is a student at the University," Montgomery explained. "He earns his meals by waiting on table here. He is studying political trends and world economics now, and it depresses him."

"Do you expect any other roomers besides Treat and Totten?" Tracy inquired.

Montgomery nodded. "Two more, that I know of. Miss Andrew—she's an associate professor in bio-chemistry—and a Mr. Brazil."

"What does he do?" Tracy asked.

"I really don't know. He sent me a telegram the other day and asked me to reserve a room for him. He gave some very excellent references—financial ones. I suspect he's interested in some sort of graduate work."

The swing-door into the kitchen squeaked open, but instead of Samson a plump, gray-haired woman appeared and smiled at them in a welcoming way. She wore a crisp white apron over a black dress that rustled slightly when she moved.

"This is Mrs. Harkness," Montgomery said. "She is our chef. The chops were delightful, Mrs. Harkness, and the custard was really superb."

Gloria LaTru said: "Swell. I'm full as a goat."

Mrs. Harkness bobbed her head, beaming. "Thank you. I do so want you all to enjoy your food. If there's anything special any of you like, I wish you'd tell me. I'll try my best to please you."

She disappeared back into the kitchen.

"She's nice," said Gloria LaTru.

"Yes," Montgomery agreed casually. "She's really the most charming murderess I've ever met, I think."

"The most charming what?" Tracy asked.

"Murderess. She split her husband's head with an axe. He really deserved it, though. He had a wart on his nose, and besides he beat her."

"Why didn't she just leave him?"

Montgomery shook his head. "Oh, no. If she had done that, he would certainly have divorced her, and divorce is against Mrs. Harkness' principles."

"Oh," said Tracy. "Did you defend her?"

"Yes," said Montgomery. "And a very nice job I did, too."

"Did you bribe the jury?" Tracy inquired.

"No."

"The witnesses?"

Montgomery winked at him. "Guess again."

"The judge?"

"Right," said Montgomery.

"You must have been a handy man to know in your time," Tracy observed, standing up. "Now if you'll all excuse me, I'll run along. I have an appointment downtown at eight."

"Aw, Pete!" said Gloria LaTru. "Stick around, kid. I'm lonesome, and there's a swell little beer joint down on Melrose where they have a juke box and a place to dance."

Tracy shook his head. "Sorry. Not tonight."

"Tomorrow night, then. Huh, Pete?"

"O.K.," said Tracy.

"Mr. Tracy," said Montgomery, "you may leave in confidence that certain—ah—occurrences will not—ah—recur. And, if I might be so bold as to advise you, I would suggest that you proceed at reduced speed and with all due caution and on lighted streets."

"I'll make out," said Tracy. "Goodbye, all."

TRACY pushed through the heavy bronze doors of the

Exchange Club and entered the hushed quiet of its small lobby. An

attendant in a white coat trimmed with gold braid came forward

and bowed deftly.

"Yes, sir?"

"I had an appointment with Mr. Stillson," Tracy told him. "Mr. Bartholomew Stillson. Is he here?"

"Yes, sir. He's in the lounge. Down the hall—the second door on your right. May I take your coat and hat?"

Tracy gave them to him and walked down the hall on a carpet so thick and springy it had a luxurious life of its own. The lounge was a long, dim cavern with flames sputtering greedily around the huge log in the fireplace at the far end of the room.

Bartholomew Stillson was hunched forward in a chair, staring gloomily into the fire. He bulked heavily in the shadows—thick and broad-shouldered and tall—and his hair glistened silvery-white. His face had a grim, determined strength in it, even now in repose. His jaw was massively wide, and his blue eyes were hard and wary and determined.

"Hello," said Tracy.

Stillson jerked around to look at him. "Who are you?"

"The name is Tracy."

Stillson stared at him blankly for a second and then reared upright in his chair and bellowed: "Elmer! El-mer!"

Elmer was an older and more suave replica of the attendant in the lobby. He materialized noiselessly in-the service door at the side of the room.

"Yes, Mr. Stillson."

Stillson pointed a thick forefinger at Tracy. "Look! Why didn't you remind me he was coming tonight? What's the matter with you, anyway? Why don't I get some service around this mausoleum?"

"You didn't tell me to remind you."

"I did so!" Stillson bellowed fiercely.

"You did not," Elmer contradicted in a calm but positive way.

"When shall I come back?" Tracy asked.

"Come back nothing!" Stillson shouted. "Come in here! I'm getting old and senile. I can't keep my appointments straight any more. I promised to go over to some damned director's meeting at the Seaforth National tonight, but that can wait for awhile. Elmer, go bring some of my brandy. Tracy, my boy, come over here and sit down and get warm. How are you? I'm glad to meet you. You look enough like your old man to be his twin brother."

"That's a compliment," Tracy said.

"It is, son, and don't you forget it. When your old man died, this country lost one of the finest scholars and teachers it will ever have. I loved the old rascal even if he did flunk me and get me bounced out of college. I owe everything to him. Why, if I'd stayed in college I might have got a degree and become a professor or some damned thing! As it is, do you know what I am, Tracy?"

"What?" Tracy asked.

"I'm a millionaire. It's a fact. I'm a real, honest-to-God millionaire. Would you believe it?"

"Yes," said Tracy.

Stillson shook his head groggily. "Well, it sure baffles me at times. I never thought I'd be worth a damn. But anyway, what's all this I hear about you taking a job teaching in Boles University?"

"Just for a semester, I think."

"Well, that's not as bad as it could be. But what did you want to take a job like that for? I wrote you seventeen times to every place I could imagine you might be stationed when I heard you were with the A.V.G., and when I heard the Group was going to be taken into the Army and you might be coming back here, I cabled you a dozen times. I've got a job for you, son. I've got a hell of a fine job for you. What're you doing at Boles University?"

Tracy said: "I'm a civilian employee of the Army at the moment. I was assigned to teach there."

"What're you going to do after you get through?"

"Go into the Army as an officer."

"What kind of an officer?"

"A First Lieutenant in the Engineers."

"Well, why?" Stillson demanded.

"I want to go back to China."

"He wants to go back...." Stillson repeated, stunned. "After dodging bombs for three solid years, you want to go back and do it some more? Are you crazy? You need a rest! You've got to take a job with me! I'm building air fields and Army barracks and hospitals and training camps from Halifax to Hell, and I got to have some expert help!"

"I'd rather be in the Army, thanks."

Elmer came back with a decanter of brandy and served it in shimmering crystal goblets and disappeared again.

STILLSON held his goblet out toward the fire and swirled

the brandy in it. "I can see that this is going to take some

thought. I can see that you are as screwy as your old man, if not

more so. This is very valuable work I'm doing, son. I'm right in

there punching with the old war effort, and a lot of it is all

new to me. I know something about construction, but not about

this kind. You do. How long is a semester?"

"About four and a half months."

"And this one starts next week? O.K., then. I've got that long to make you sensible. I'll get you to work for me if I have to slam you over the head with your own slide-rule. You aren't married, are you?"

"No," said Tracy.

"That's it!" said Stillson triumphantly. "You need a wife, Tracy. I can see that. A wife would soon talk you out of any nutty notions about going to China. I'll start looking for one for you right away. I've got some fine prospects in mind. I know! I'll have a party, by God! I'll invite them all and let you take your pick!"

"Maybe the one I picked wouldn't like me."

"Don't be dumb," Stillson ordered. "Any girl would jump at you like a shot. Now, when are you going to move in?"

"Move in where?" Tracy asked.

"Into my joint, of course. I've got a whole damned castle up on a hill north of town. It's so big I rattle around in it like a peanut in a hogshead. I have to come down here to the Club all the time to keep from going loony. You move in and keep me company."

"I appreciate it," Tracy told him. "And thanks a lot. But I'd rather stay down near the University. I've taken a room in a boarding-house at 1212 Chaucer Street. It's under the name of Montgomery in the directory."

"You're a hard guy to do business with," Stillson said gloomily. "You don't co-operate worth a damn. But I'll persuade you. I'll put my mind on it. And wait until you see the girls I'm going to dig up and the party I'm going to throw for you! You'll fall like a busted elevator. Now look, Tracy, I'm sorry as all get out, but I've got to go over and listen to those bankers mumble in their beards. It was an awful thing—forgetting our appointment—and I apologize a thousand times."

"It's all right," said Tracy. "I didn't have anything to do, anyway."

"Elmer!" Stillson shouted. "El-mer!"

"Yes, Mr. Stillson," said Elmer quietly-

"Fix Tracy up with a club guest-card. Peter Tracy, Boles University. You stick around here now, Tracy. There's everything you want to amuse yourself—billiards, bowling, gym, swimming pool—I'll give you a ring tomorrow or the next day. 1212 Chaucer—Montgomery. Yeah, I'll remember it. See that he's amused, Elmer. Good-bye, Tracy. It was a hell of a pleasure to meet you. I've got to run. Good-bye."

His feet thumped hurriedly down the hall for about twenty paces and then thumped back again.

"Tracy," he said from the doorway, "I want to ask you a personal question."

"Go ahead," Tracy invited.

"Is that your best suit?"

"Why, yes," Tracy admitted, looking down at his sober blue serge.

"I thought so. I didn't imagine you'd find many places to buy good clothes in China. So far you've refused everything I wanted to do for you, and you can't turn me down on this. I insist. Here." Stillson snapped a card across the room. "That's my tailor. He's a wizard. You go to him and get fixed up. I want you to look your prettiest when your future wife sees you for the first time. And don't forget my party, either. I'll call you. Good-bye."

His feet thumped away.

"Mr. Stillson is a very busy man," Elmer said. "He's the director of more than a dozen companies, and the war has added tremendously to his responsibilities."

"I know," Tracy said, picking up the tailor's card and putting it in his pocket. "I'm going to take him up on the clothes offer. This suit is five years old if I remember rightly. I had to leave most of my stuff in China."

"You won't be disappointed," said Elmer. "The tailor is very good. Mr. Stillson even sent me there to get a suit. My wife says it is the best-looking one I ever had. Is there anything I can get you now, Mr. Tracy?"

"No, thanks. I've got to go along home in a minute."

"Please wait until I make out your guest-card. It will take just a short time. Have another glass of Mr. Stillson's brandy. It's really excellent. I find that it is especially soothing when consumed in front of an open fire."

Tracy smiled. "All right. I'll have another."

TRACY dismissed his taxi at the corner of Melrose and Chaucer and strolled along through the moving shadows toward the Montgomery house. He felt warm and relaxed and comfortable, and he was humming slightly off-key when he turned in the front walk. He stopped humming abruptly when a man stepped out of the darkness under the four oak trees.

"Peter Tracy," said the man, as though he were checking a name off a list.

Tracy had felt this same frozen horror once before, when he had opened the front door of his bungalow and found a king cobra coiled in the middle of the living-room floor. He could not see this man's face, but he had a quick and daintily precise way of moving that was chillingly reminiscent of the snake, and now an automatic made a darting, dark gleam in his right hand.

Bagby's voice said suddenly: "Drop that gun, fancy-pants, and stick up your hands!"

The man with the gun whirled to face the sound, and Tracy jumped for him. He got a double-grip on the wrist of the hand with the gun in it. He whirled himself, then, and bent forward, trying to throw the other man over his shoulder.

The other man had cat-like agility. He didn't throw. He tripped Tracy instead, and the two of them slammed down hard on the ground and rolled over and over again with Tracy still holding onto the wrist, and then the other man kneed him in the stomach with his full weight behind it.

Tracy doubled up with a soundless cry of agony. The wrist and hand slid out of his grasp, but they left the automatic behind. Tracy threshed and groaned on the ground, trying to get hold of the gun, trying to get up.

There was a flat, spatting sound and a thud on the ground, and then feet ran away in a hurrying, quick whisper that faded instantly. Somebody put an arm under Tracy and heaved him up to his feet.

"Did he knife you?" Bagby asked.

"No," Tracy gasped. "Knee... stomach."

"You're lucky," Bagby told him. "He popped me one right in the mouth." He made a sucking sound and then spat something white. "That was one of my best teeth. Hey! Where you going?"

"Chase...."

"Come back here, you dope. You couldn't run ten feet in the shape you're in, and anyway you might as well try to catch moonbeams as that guy. He had it all laid out. He blew around the house and through the gate in the back fence and down the alley. He's two blocks from here by now."

Tracy straightened up slowly and painfully. "Why didn't you shoot him?"

"Me?" said Bagby. "Say, I didn't have no gun. I don't dare carry one. I'm on parole. They catch me with a gun, and I'd be slapped away in the sneezer for the rest of my natural life as a habitual criminal."

"Why didn't you warn me?"

"How do you like that?" said Bagby. "I save the guy's life, and he wants to give me an argument about how I did it! I didn't know whether to believe what you told me this afternoon or not. I thought maybe you might actually know the guy and not want to admit it. I spotted him hanging around here waiting for you, so I waited, too. When I saw he really meant to blast you, I yelled."

Tracy kneaded his stomach gingerly. "Thanks."

"Well, it's about time."

"Was this the same man who was asking about me?"

"Yeah," Bagby answered. "Say, what's this all about, Tracy? Who's out to put the twitch on you?"

Tracy drew a deep, exploratory breath. "It's just crazy. It doesn't make sense. I haven't got any personal enemies that I know of. I haven't even been in the United States for three years. I'm just exactly what I claim to be—a civilian employee of the Army assigned to teach here at Boles University."

"You ain't got any military secrets tattooed on your toe nails, have you?"

"No!" said Tracy. "I wouldn't know a military secret if it bit me!"

"Something almost did," Bagby observed. "Is that his gun? Let me see."

Tracy handed him the automatic.

"Yeah," said Bagby. "Like I thought. It's one of those Spanish mail order babies. Lots of shooters use them. After they knock you off, they just drop the gun beside you and scram. There's no way to trace the gun, and if they catch the guy even ten feet from your body they can't prove he shot you unless somebody saw him doin' it."

"I didn't believe there were actually any people like that."

"Where you been all your life?" Bagby demanded. "There's plenty of 'em. It don't take no brains to be a killer. You just have to be cold-blooded and fast on your feet. These here professionals, they don't go in for fancy-work. They don't put poison on pins or ground glass in your soup or any dream stuff like that. They just shoot you and run. You'd be surprised how few of 'em get caught at it, too. Here, take this gun back. I don't want it."

TRACY put the automatic in his pocket.

"The whole business is still insane. Maybe the man who is after me is a maniac."

"Not him," Bagby said flatly. "He was a little hopped up on marijuana tonight—did you smell his breath? But he ain't by no means nuts. He was after you in person. He knows who you are. He knows you come from China. He told me that when he was tryin' to pump me this afternoon."

"What did he want to know about me?"

"He was just scouting. He wanted to be sure you lived here, and if you ate here, and did I know if you went out at night much, and did you have a dame, and all such like that. I answered him with a lot of double-talk."

"But why should anyone want to kill me?"

Bagby regarded him thoughtfully in the darkness. "Do you wanta find out?"

"Well, certainly!"

"I can locate this guy for you, but I ain't gonna do it if you're gonna turn him over to the cops. I'm no squeaker."

"How can you locate him?"

"I got ways. I can find anybody in this burg that's on the wire."

"On the wire?" Tracy repeated.

"Crooked," Bagby explained. "I mean, any professional. Amateurs I don't fool with. But this guy ain't. He's an old hand."

"Well...." Tracy said doubtfully. "What good would it do to locate him? I'm not one of these brave and bold boys who like to set themselves up as targets for people."

"Oh, we'll fix that. You got any dough?"

"A little."

"Two or three hundred bucks you can spare?"

"Yes."

"O.K.," said Bagby. "We'll just offer the guy more for talking than the guy that's hirin' him is offerin' him for shooting you. He'll talk. That's the trouble with them killers. They're dishonest. I'll see what I can do tomorrow. I got to go now and put a hot water bottle on this tooth of mine."

"Well—thanks again."

"You can buy me a beer for Christmas," Bagby said. He went around the comer of the house, heading for the back door.

Tracy went up the steps to the porch and groped in the gloom for the front door knob. The light inside was not burning now, and he opened the door and stepped into the warm, thick blackness of the hall. He felt along the wall beside the door, seeking the switch, and then he stiffened warily, turning his head a little.

Very quietly he took the automatic out of his pocket and then took two long steps forward in the darkness and thrust the gun out straight ahead of him. The muzzle prodded into something soft and yielding, and there was a sudden painful gasp.

"Stand still," said Tracy.

"Puh-Pete," said Gloria LaTru. "It's just—just me."

"You're just about enough, too," said Tracy. "What are you doing sneaking around here?"

"I wasn't! I heard something... Pete, what happened outside?"

"Bagby and I were just playing fun."

"You—you poked me right in the stomach. It hurt. What did you poke me with?"

"A gun."

"Oh! The same... I mean, is it loaded?"

"It is," Tracy answered. "And it's not the same one you found in my trunk. What were you looking for in the trunk?"

"I didn't! I never—"

"Do you want me to poke you again?"

"No! Pete, I—I lied to you kind of."

"Am I surprised," said Tracy.

"Well, I did work in a pickle factory once, but that isn't where Pappy found me. He found me in court. I was—was charged with shop-lifting. Pappy got me released on probation and—and—"

"And," Tracy finished. "This is all very interesting, but what about my trunk?"

"Well, Pappy doesn't give me any money at all. He lets me buy anything I want, when he's with me, but he never gives me any money of my own. I thought you were an old dopey professor, and that there might be something in your trunk that you'd be so absent-minded you would not miss, and that I could—could—"

"Steal it and pawn it," said Tracy.

"Yes, Pete. I'm awful sorry. I'm scared of guns. I lifted that one out of your trunk all right, but I was afraid to put it back in again for fear it might shoot or something. I didn't steal anything, Pete. Honest. And I won't bother any of your stuff again. Aw, don't get mad and go tell on me, please."

"O.K.," said Tracy wearily. "But I don't want to hear of anyone else around here missing things."

"They won't. Honest, Pete. I promise. You ain't mad at me now, are you?"

"No," said Tracy.

"Do you—you like me, Pete?"

"Oh, sure."

"Pete."

"What?" said Tracy.

"You're still gonna take me to the beer hall tomorrow night, ain't you?"

"I suppose so."

"Pete."

"What?"

"Would you like—to kiss me?"

"Not right now," said Tracy. "Run along."

Gloria LaTru said: "You're sure a surprising character, Petesey. You look dumb, but you ain't. I think you're pretty sharp, myself."

"Go away," said Tracy.

HIGH heels made suddenly sharp taps on the front porch,

and someone came in the hall and said in a disgusted voice:

"Saving electricity again!"

The light switch snapped, and the chandelier jumped into sudden brilliance.

"Well!" said the woman in the doorway. "In fact—well, well, well! Can this be true? Things and stuff going on in dear old Montgomery's respectable boarding house?"

She was tall and bony and gray-haired, and the skin on her face was tanned to the shade of new saddle-leather. She wore a tailored blue suit, and she was carrying a black traveling case in her right hand.

"We live here," said Gloria LaTru.

"So do I," said the woman. "My dear, if I had as nice an anatomy as you have, I'd wear a lace nightgown like that, too, but not in public under a bright light."

"Oh!" said Gloria LaTru, suddenly remembering. "Oh!" She whirled around and ran headlong up the stairs.

"My, my," said the bony woman, watching her. "How did she ever get into this home for the aged and decrepit?"

There was a shrill, startled squeak from the hallway upstairs. Feet pattered along it, and then Penfield appeared at the top of the stairs. He was bundled up in a moth-eaten blue bathrobe, and his face was white and stiff with shock.

"A woman!" he said. "In the hall! In—in a nightgown! At least, I think it was a nightgown! I never saw anything like—" He saw the bony woman and ducked back out of sight.

"Penfield!" she called.

Penfield's head protruded cautiously around the newel post.

"Introduce us," the woman ordered.

"Miss Andrew, may I present Mr. Tracy?" Penfield said hastily. "Mr. Tracy—Miss Andrew." He ducked back out of sight again.

Miss Andrew nodded to Tracy. "I'm bio-chemistry. What are you?"

"I'm sort of spraddled around between engineering and modern languages."

"You're one of the new War Department boys, eh?"

"Yes."

"Good," said Miss Andrew. "You're what we need around here. The University was accumulating too much old ivy on the walls and too much old ivory in the professors' heads. I'm sorry I interrupted your little jam session. You should hang out a warning sign."

"I was trying to get rid of her," Tracy said.

"Then you must be even dumber than you look," said Miss Andrew.

"You don't know her."

"I've got eyes, though," said Miss Andrew. "I didn't notice you hiding your head when she ran upstairs, either. I'll bet she's going to liven things up around this imitation of a tomb."

"If she only stops there," Tracy observed, "everything will be dandy. Good-night."

IT WAS dusk the next day when Tracy came dragging his heels up Chaucer Street, too tired even to whistle. During the day he had interviewed another couple of hundred students anxious to enroll in his proposed classes. It seemed that there was no end of them. As a matter of fact this was worrying the University authorities, too. They hadn't anticipated that so many people would be so anxious to pick up the pearls of wisdom that fell from Tracy's ruby lips. Tracy had experience and practical knowledge. The students wanted to hear about that. They were tired of theory, no matter how high-flown and brass-bound it might be.

Tracy was turning into the walk of the Montgomery house when a voice from across the street called: "Hey! Hey, son!"

Tracy turned around warily. A mailman humped under a bulging leather bag, limped across the pavement toward him.

"Are you goin' into Montgomery's, son?"

"Yes," said Tracy.

"Take these two letters, will you? They are for Treat and Totten."

"I don't think they're here yet," Tracy said.

"Just leave 'em inside the door on the table, then. It'll save me a few steps, son, and my feet are awful sore. Will you?"

"Sure," said Tracy, accepting the two long manila envelopes.

"Thanks, son. What's your name?"

"Peter Tracy."

"Tracy," said the mailman. "Tracy at Montgomery's. Nothing for you today, but I'll remember who and where you are. So long."

He went limping on down the street, and Tracy went up the front walk toward the house. He looked around, but he couldn't see Bagby anywhere, and he went up on the porch and through into the front hall. There was a loud burst of laughter, dominated by Gloria LaTru's contralto giggle, from the study. Tracy looked in.

"Pete!" Gloria LaTru greeted enthusiastically. "Look what I found! These are Teeter and Totter!"

She was sitting on one of the leather divans, like a queen holding an audience, and two men had pulled up chairs close in front of her.

One of the men jumped up now and stood at exaggeratedly rigid attention. He was very tall and thin, and he wore horn-rimmed spectacles balanced precariously on the end millimeter of his nose. He thrust a skinny right arm out straight, palm-down.

"The name is Treat," he barked. "Heil Hitler!"

"Heil Hitler," Tracy answered. "Here is a letter for you."

The second man got up and bowed six times rapidly. He was short and round and he had a pudgily pink face.

"The name is Totten," he said. "Oh, so-o-o. Banzai Hirohito, prease!"

"The accent is on the second syllable," Tracy informed him. "Here's a letter for you, too."

"Of course their names are really Treat and Totten," Gloria LaTru said. "But I think Teeter and Totter are more fun, don't you, Pete?"

"Sure," said Tracy. "Do I get introduced to your other admirer?"

The man was sitting back in the corner in the shadow, and he was smiling in a politely amused way. He had a round, smoothly olive face and black, lacquered hair. His teeth were very white and even.

"Oh, yes," said Gloria LaTru. "This is Mr. Brazil. This is Pete Tracy, Mr. Brazil."

Tracy nodded. "Mr. Brazil—of Brazil, I presume?"

"Peru," said Mr. Brazil.

"Mr. Brazil of Peru," Tracy corrected. "I'm very glad to know you."

"I assure you that it is mutual," said Mr. Brazil.

"AH-HAH!" Treat exclaimed, waving the envelope in the

air. "Ah-hah! I made it! I enter our armed forces as a sergeant

as of next month! Totten, you worm, just wait until I get you in

my awkward squad! Squads right! Shoulder arms!"

"In the future," said Totten loftily, "when you find it necessary to address me, Sergeant, kindly say 'sir'."

"What!" Treat shouted, outraged. He snatched the envelope out of Totten's hand. "A commission as a Second Lieutenant! Conspiracy! Fraud! Tracy! What is our Army coming to? Can you imagine making a drooling moron like this an officer?"

"You forget," said Totten, "that I have had four years of advanced military training."

"Advanced military horse-radish," Treat said rudely. "Let me see... Ho! Infantry! No wonder! Anybody can be an officer in the Infantry! All they do is run around and sleep in ditches! I'm in the Air Force!"

"Gnats," said Totten. "Flies. Buzzards. The Infantry is the Queen of Battle."

"Pooey! Tracy, give this idiot a lecture on the rudiments of modern military strategy!"

"You two fight it out," Tracy advised. "Personally I prefer the Engineers."

"The man is mad, Totten," said Treat.

"Obviously," Totten agreed. "An advanced mental case. He should be confined."

Montgomery appeared in the doorway. "Mr. Tracy, you are wanted on the telephone. You'll find it right under the stairs, there."

Tracy wormed himself into a tiny, slant-roofed closet lined with plasterboard that was decorated with pencil-written telephone numbers and appropriate comments on same and picked up the receiver.

"Yes?" he said.

"Bartholomew Stillson speaking. Tomorrow night."

"What's tomorrow night?" Tracy asked.

"The party I'm giving for you! Up at my place on the hill. Come any time after eight. I'm sorry for such short notice, but I couldn't have it over the weekend because there's a big USO blow-out coming off, and everybody is going to that. You can make it tomorrow night, can't you?"

"I think so."

"Well, you've got to come, Tracy! You should see the girls I've collected for you! I told them all you were a war hero, and they're waiting with bated breath and starry eyes! You'll have a dozen to pick from!"

"I'll be there," said Tracy.

"O.K. Good-bye, Tracy."

Tracy hung up and squirmed out of the closet. Gloria LaTru was waiting just outside the door.

"Who was that, Pete?" she asked.

"A guy," said Tracy.

"Where you going tomorrow night?"

"Out."

"With another dame, huh?"

"Why don't you mind your own business?" Tracy inquired.

"Aw, Pete. Don't be mean. You're going to take me to the beer parlor tonight, remember?"

"Yes," said Tracy wearily.

Montgomery came out of the dining room. "Dinner is served now, if you're ready."

"Where's Bagby?" Tracy asked him.

Montgomery shook his smooth head. "I don't know, really. Probably lying in the gutter somewhere dead drunk. I haven't seen him all day. Shall we eat?"

"Come on, Pete," said Gloria LaTru. "You sit by me."

THE Bull and Boar was a beer hall with collegiate

variations. It was a narrow, noisy room devoid of all pretense at

decoration with a short service bar at one end, a juke box in the

middle, and rows of heavy-topped tables along each wall. The

waitresses wore white starched uniforms, and they were all co-eds

working their way through the University. If you tried to tip one

of them you were liable to get your face slapped, and if you

attempted to make what are known as advances you were lucky if

you escaped with some minor injury like a fractured skull. The

management had no objections if you wanted to get drunk in the

place, but the customers did. At the first wobble, you got the

heave-ho from such assorted football players and shot putters as

happened to be present.

The place was crowded and the juke box was tearing away at a tune when Tracy followed Gloria LaTru in through the front door. The noise was deafening. "Cute, huh?" said Gloria LaTru.

"Wait until I see which tables Etta is serving. I met her when we were registering. Etta!"

A small, dark girl in a waitress' uniform slid through the squirming press of dancers around the juke box.

"Hello, Gloria. Sit over at this table."

They sat down at a table near the door, and Etta said: "Is this he, Gloria?"

"Yeah," said Gloria LaTru. "This is

"What'll you have?" Etta asked. "A couple of beers?"

"Whatever is right," Tracy answered, a little dazed by all the sound and fury.

Etta went away and came back again with two quart bottles of beer and two tall glasses. "Sixty cents," she said. She took the change from Tracy and hesitated.

"Go ahead," Gloria LaTru urged.

"Mr. Tracy," said Etta, "I want to get in that class of yours in Modern Asiatic dialects."

"Oh," said Tracy vaguely. "Do you?"

"Yes. I'm a language major, and I'm sure I can handle it, and I want to take the course. But they won't let me."

"Why not?" Tracy asked, surprised.

"They say it's just for men who are going into the Army. They won't admit any girls."

"Oh," said Tracy. "I didn't know that."

"Well, won't you make an exception for me, Mr. Tracy? It won't make any difference, really. You've got too big a class already for recitations."

"Have I?" Tracy inquired.

"Why, yes. You've got a hundred and fifty-three registrants for the course now. If you called on students to recite, you wouldn't get through the class roll twice in a semester. You'll have to lecture."

"Lecture?" Tracy echoed, horrified. "Me?"

"Yes. I'll sit in the back of the room, and I won't bother anyone. It certainly can't do any harm if I just listen, can it?"

"No," Tracy admitted. "I really don't know much about this business, Etta, but I tell you what you do. You fill out a class card and leave it on my desk—I'm in 203 in the Administration Building. I'll just slip it into my files and register you in the class. Nobody's told me anything about not admitting girls. If they do, I'll say I've already promised to let you in. If anyone asks you about it, you say the same thing. We'll edge you in some way."

"Oh, thanks!" said Etta.

"I told you Pete was a good guy," Gloria said.

"Call me if you want me," Etta said. "I'll be in your class on Monday, Mr. Tracy."

GLORIA LATRU poured beer expertly into her glass. "Have a

beer, Petesey, and stop looking so sad."

"Lecture," Tracy said numbly. "That means I have to stand up there and talk for an hour every day."

"You'll do O.K.," said Gloria LaTru. "You're sharp like a razor, Pete. You'll slay 'em. Drink some beer now, and then we'll have us a dance. I want to see—"

An automobile horn blasted lengthily once and then again from the street outside. It was a heavy, expensive, commanding sound that penetrated clearly through the din of the juke box.

"Oh!" said Gloria LaTru, staring wide-eyed at Tracy. "That's Pappy!"

The horn blew twice more.

Gloria LaTru stood up. "I—I've got to go, Pete! He's gonna be mad.... Don't come out with me!"

She ran quickly to the door and went out. Tracy sat frowning for a second and then got up and followed her. He didn't go out into the street. He stopped in the shadow of the doorway and stared with one hand up to shield his eyes.

The car looked like its horn sounded. It was a big club coupe—long and sleek and black, gleaming with chrome. Gloria LaTru was getting into it, and Tracy caught just a glimpse of the driver's face. It was thin and lined, tightly aristocratic, with a precise gray mustache. Then the door thumped behind Gloria LaTru, and the car rolled smoothly away down the street.

Tracy watched it until it turned a corner and disappeared. He was still frowning, and after a moment he went back into the beer hall and to his table. Mr. Brazil was now sitting where Gloria LaTru had been. He showed his white teeth in a smile and said: "Good evening, Mr. Tracy. Please sit down."

Tracy lowered himself slowly into his chair. He picked up his glass of beer and sipped at it in a thoughtful way, watching Mr. Brazil.

"I wanted to talk to you," said Mr. Brazil, "and I think this is a very nice place to do it. There is so much noise it would be impossible for anyone to eavesdrop on us. I don't think you believed me when I said I was from Peru, did you?"

"No," said Tracy.

"I'm not, really, although I am a South American by adoption. I'm a member of the Japanese colony on the coast just below the bulge of Brazil."

"I can't buy that, either," said Tracy.

"No? Where do you think I'm from?"

"Wu-Chei Province in China."

"You are very observant," Mr. Brazil complimented. "And quite correct, too. So it won't be necessary for me to waste time establishing my identity. I will proceed at once with the business at hand. You remember a town called Lao-Tsu?"

"No," said Tracy.

"You are also discreet, I see. You know the town. You designed and supervised the construction of a secondary base hospital and rest camp for walking-wounded there."

"Did I?" said Tracy.

"Yes. You finished it in June of 1940. I had occasion to purchase some medical supplies for that hospital. I bought some anti-tetanus vaccine for use there. That is, it was sold to me as anti-tetanus vaccine. Actually it was a concentrated solution of tetanus bacilli."

"What?" said Tracy, startled.

Mr. Brazil smiled thinly. "Yes. Anyone who was given that supposed vaccine was virtually certain to die horribly with lock-jaw. Over five hundred slightly wounded soldiers died just that way before we found the source of the infection. Lock-jaw, you know, has quite a long period of incubation, and the wounded were coming in very fast."

Tracy's lips twisted. "Who would...."

"Who would do such a thing?" Mr. Brazil said. "The Japanese, of course. It was one of their horror tricks—to make Chinese soldiers distrustful of their doctors and their hospitals and also to eliminate numbers of veterans who were only slightly wounded and would be back fighting soon. I want to repeat: I was the one who purchased that supposed vaccine."

"I see," Tracy said slowly.

"If I were Japanese," said Mr. Brazil, "I would commit suicide. But I am Chinese and hence a little more intelligent. I am looking for the man who sold me that vaccine. The Japanese, of course, paid him to substitute the tetanus virus for the genuine vaccine."

"Yes," said Tracy.

"I bought it from a man named Kars. Do you remember him?"

"Why, yes," Tracy said. "He's dead. He was killed in an accident on the Burma Road just before I came back to this country. I was there when it happened. We were going into Lashio. He was riding in the truck just ahead of the one I was riding in. His truck went off the road and rolled down into a canyon. He was killed instantly."

"I know. That was before the Road was closed. You took Kars' body into Lashio and saw that he was buried there. You took his papers and personal effects and sent them back here to the United States. You sent them to a post office box in this city which had been rented under the name of William Carter."

Tracy nodded. "That's right. Kars had an identification card that said to notify this Carter in case of any accident, so I wrote him a letter and sent Kars' stuff to the address given. Have you located Carter?"

"No. There is no such person. It's a false name. But someone collected Kars' effects from the post office before I could get here."

Tracy said slowly: "Well, if Kars is dead...."

"He was only an agent. Ostensibly he was hired by the Chu Sing Importing Company. That is a firm of two Chinese partners which operated in Singapore before the invasion. The partners are dead now."

"Did the Japs kill them?" Tracy asked.

"No," said Mr. Brazil. "I did. They were traitors. Before they died they told me that this vaccine deal had been made through a man named Ras Deu in Calcutta. He is supposed to be some sort of a broker. I went to see him. He did not wish to talk to me, but he changed his mind after I cut off two of his fingers."

Tracy swallowed. "I can understand that."

"However, what he told me was worth nothing. It led me back to where I started. Kars was furnishing Ras Deu with capital to act as purchasing agent. You see that three-cornered set-up— Kars and the Chu Sing Company and Ras Deu—was designed to confuse any legal investigation and to conceal the identity of Kars' principal. Neither Ras Deu nor the Chu Sing partners knew the principal's identity. He is the man who took Kars' effects from the post office box, and I am very sure that he must be in this city somewhere. Now I wish to ask you some questions."

"I'll tell you anything I can," said Tracy.

"Thank you. What did you find when you searched Kars' body?"

"Nothing but a few personal effects—and very few, at that. I remember thinking about it at the time. He had a watch and a pen-knife and a good ruby ring, and he was carrying quite a lot of money. But he had no papers or letters at all—not any. I thought that was strange. He had an American passport with British and Chinese visas. He had a couple of check books—one from a bank in Singapore and the other from a bank in Delhi, I think. He had no business cards or anything else but money in his wallet—except that identity card saying to notify Carter."

"I was afraid that would be the case," Mr. Brazil said slowly. "Men like he was are very careful not to carry anything that would get them into trouble if they are arrested and searched. But I was hoping there might be something you saw that would give me a hint."

Tracy shook his head. "No."

"I wish you would try to remember everything—anything. You need not hurry about it. I will be here for some time, I think. You see, until I find another, you are my best clue."

"I am?" said Tracy.

"Yes. You wrote to this man who sometimes calls himself Carter. He knows you were there when Kars died. I happen to know that Kars was horribly mangled in the truck wreck and died instantly, but this fake Carter can't be sure of that. He can't be positive that Kars didn't talk to you before he died—confess something, rave something in delirium. Knowing the kind of a man this fake Carter must be, I think he will take steps to see that you don't reveal anything you might have heard."

"Yes," said Tracy. "He might do that."

Mr. Brazil stood up. "I would be careful if I were you, Mr. Tracy. If you recall anything that might be of help in my search, please tell me. I bid you good-night."

"Good-night," said Tracy.

He sat still for a long time after Mr. Brazil had gone, frowning down at his glass of beer, ignoring the tumult that went on around him. He understood now a great many things that he hadn't before, but understanding them didn't make him feel any better. In fact, he felt worse. He fumbled around in his pocket and found a grimy briar pipe. He had found long since that smoking this pipe indoors made him unpopular, but he needed its comfort now. He inhaled lungs full of acrid smoke and studied the situation.

"Hi," said Bagby. He slid into Gloria LaTru's chair, picked up her bottle of beer, and took a long, thirsty drink out of it. "I found him. Name is Joel Winters. He's home now. You wanta go see him?"

"Very much so," said Tracy.

"Got any dough on you?"

"No, but I've got about three hundred dollars in traveler's checks."

"They're O.K. I can get 'em cashed if we need to. Come on."

Bagby up-ended the beer bottle again and then led the way out of the beer hall and up the street to the corner of Third. There was a taxi stand there, and Bagby and Tracy got into one of the waiting cabs.

"Kester and Call," Bagby directed.

The driver looked back over his shoulder. "They roll pretty rough down there this time of night."

"We're rough people," said Bagby.

The driver shrugged. "O.K. It's your funeral."

THE district around Kester and Call was one place that was completely enthusiastic about dim-out regulations. People in those parts liked it dark. There were no outside neon signs, and the cafe windows had been painted over until they looked like bleary, blank eyes. The street was a narrow, steep-walled trench full of shadows that moved and muttered or were suggestively silent. The police patrolled in radio cars here—four to each car—and there was a reinforced riot squad on duty at the East Station two blocks off Kester twenty-four hours a day. There were no soldiers or sailors on leave anywhere around. The neighborhood was out-of-bounds.

"Don't think I'm gonna wait here for you," said the taxi driver. "I got some sense."

"Run home to momma," Bagby advised, paying him. "That's a buck eighty-four you owe me, Tracy. Come on."

They walked on into the dimness of Call Street. The door of a beer parlor opened and erupted riotous music and two drunks who fought in a squalling, furious tangle in the middle of the sidewalk. Bagby stepped over and around them without a second glance.

"Reminds me a little of Port Said," he remarked.

"Have you been there?" Tracy asked, surprised.

"Oh, sure. You got your gun, ain't you?"

"The one I took from this bird we're going to see."

Bagby stopped. "What did you bring that one for? You couldn't hit a barrage balloon at ten paces with it. Why didn't you bring yours?"

"I haven't got any cartridges for it—and what do you know about it, anyway?"

Bagby shrugged and walked on. "After you beefed to Montgomery, I thought maybe I better look around myself. I wouldn't want you to be nailed with a trunkful of hashish in the joint—not while I'm livin' there. That gun of yours is a Jap pistol, ain't it?"

"Yes. One of the A. V. G. pilots gave it to me. It belonged to a Jap bomber pilot he shot down."

"You know now who first searched your room, don't you?"

"Yes."

Bagby walked on in silence, and Tracy finally said: "Well?"

"I ain't got a thing to say," Bagby affirmed.

Tracy hesitated. "Do you think she and this Winters..."

"Nope. He's a cheapie. He never bought anybody—including himself—the kind of clothes she's got. What I mean, they cost dough. Hold still a minute, now. I'm going to light a match."

The match head snapped on his thumbnail, and he cupped his hands around the spurting yellow flame and held it up in front of his face for a second and then blew it out.

"Yeah," a voice whispered out of the shadows.

"You sure?" Bagby asked.

The man's face was a pallidly furtive smear. "Yeah. He's havin' a bit of tea. I smelled them reefers."

"Is he alone?"

"I ain't seen nobody."

"O.K. Here." Bagby reached out in the darkness. "Now blow."

The pallid face drifted away and was gone.

Bagby said: "This Winters is touching himself up a bit with marijuana, so you better sort of get that gun ready. He might be jumpy. In this way. Watch your step. That's six eighty-three you owe me, now."

"Who was that you talked to?"

"Name of Weepy Walters. Used to be a touch-off—a fire-bug—before he got the jumps. I told him to watch. Don't talk any more."

They went back through a narrow passageway in swimming blackness.

"Door here," Bagby whispered. "Stairs beyond it. Our guy is sittin' behind the second door on the right in the hall upstairs. Be quiet."

Door hinges made a small sliding sound. Tracy brushed against Bagby's back and then found the first step with his foot. They went up silently, stepping together, and light began to make a faint glow ahead. They came up to the level of the hall floor, and the light turned into a small, dusty bulb over a curtain-masked window at the end of the short hall.

"Back way out," Bagby murmured. "About a twelve foot jump into another alley. Here." He touched the pistol in Tracy's hand meaningly and then pointed to a closed door.

Tracy stepped sideways, raising the gun. Bagby nodded approvingly and then scratched gently on the door panel with his finger-nail.

THERE was no sound from within.

"Maybe he's passed out," Bagby whispered. "I hope."

He knocked once, sharply, on the door. There was still no answer. Bagby touched the door knob gently. He looked at Tracy and formed the word "unlocked" with his lips. He was frowning. He made a little motion with his hand, and Tracy stepped further to one side.

Bagby nodded, looking worried. He stepped sideways himself, against the wall, and then reached over and turned the knob and kicked the door with his heel. The door swung clear open and thumped lightly against the wall inside the room. There was no light.

"Winters," Bagby said quietly.

No one answered. Bagby wiped some perspiration from his forehead and then took a match from his pocket and held it up for Tracy to see. He snapped the match on his thumb and flipped it around the door jamb into the room. It painted a quick streak in the darkness and then snuffed out.

"Uh!" said Bagby breathlessly.

"What?" Tracy asked.

"He's dog meat," Bagby said. "Inside—quick."

He slid inside the room himself and closed the door as soon as Tracy had cleared it. He fumbled in the blackness, and then the electric light switch snapped under his hand.

The man called Winters was lying on his back on top of the narrow, rumpled bed. He had taken his coat and tie off, but he was fully dressed except for them. He was staring in mild, sightless surprise at the ceiling, and his mouth was open just a little. There was a triangular rip in his shirt-front over his heart, and blood had made a rust-colored stain around it.

"Right through the ticker," said Bagby. "It was a friend of his. Somebody that come in and talked to him all nice and cozy until he was relaxed and then let him have it with a knife."

"Somebody who thought the same thing you did," Tracy said. "That he'd talk to me—if he was paid."

"Maybe," said Bagby. "Guys like him—they got lots of people who don't like 'em. You take it all nice and calm, I must say."

"I've seen dead people in car-load lots."

"Oh. Well look, Tracy. I can't report this. The cops will slam me into the sneezer even if they know I didn't do it on account of they don't like me."

"How about the man outside—Weepy?"

"He won't talk. I know some things about him that would surprise you—and the cops, too."

"Let's go, then."

"Where?" Bagby asked cautiously.

"Back home. I've got an idea—"

"Don't tell me!" Bagby urged. "I don't want to know what it is. From now on, I'm an innocent bystander. Falling over corpses sort of spoils my sleep. Just wait until I wipe my prints off the door and the light switch."

IT WAS five minutes of eight the next morning when Gloria LaTru ran down the stairs into the front hall of Montgomery house and stooped with a little gasp when she saw Tracy waiting for her in the doorway of the study.

"Pete!" she said breathlessly. "You made me jump! You ain't mad, are you? About last night?"

"No," Tracy answered. "I want to talk to you."

"Well, I can't now, Pete. I've got an eight o'clock class, and I overslept, and if I'm late the first morning it meets it'll make a bad impression—"

"Just a second. Who is Pappy?"

"What, Pete?"

"Who is Pappy?"

"Aw, Pete. You wouldn't go and say anything to him or—or anything—"

"Tell me his name."

"Well, it's Oliver Johnson. Pete, he's awful jealous. Please don't—don't—"

"You'll be late to class," Tracy said.

Gloria LaTru stared at him for a moment, chewing on her soft under-lip, and then ran on out the front door.

Tracy looked over his shoulder. "Mr. Montgomery, have you a city directory?"

"Right here," said Montgomery. "I just located it for you. Would you like me to give you a bit of advice?"

"No," said Tracy.

Montgomery sighed. "I was afraid you wouldn't. Perhaps it wasn't very good advice anyway."

There was only one Oliver Johnson in the directory. He was listed as the owner of a wholesale plumbing supply business on the west side. Tracy wrote down the address in his notebook, tore out the page, and took it upstairs. He knocked on the second door along the hall.

Mr. Brazil opened the door. "Yes, Mr. Tracy?"

"Will you do a favor for me?" Tracy asked. He extended the page from the notebook. "I'd like to know a little something about this man—his description, his finances, the kind of a car he drives. Can you find out?"

"Surely," said Mr. Brazil.

Tracy went back downstairs, and Samson served him his breakfast. Fifteen minutes later, when he came out into the hall, he found Mr. Brazil waiting for him.

"Oliver Johnson," said Mr. Brazil, "is in precarious financial circumstances at the moment because of priority difficulties in his business. He has been seeking a position in a defense factory. He is about five feet four inches tall, bald and fat, and he wears thick glasses. He drives a '36 Ford sedan."

Tracy stared at him blankly.

Mr. Brazil smiled. "There is no magic involved. I merely made inquiries of certain people over the telephone while you were eating."

"Thank you," Tracy said thoughtfully.

"Not at all. Mr. Tracy, would you like to have me find out who Pappy is?"

Tracy looked at him. "Yes, I would."

"All right," said Mr. Brazil. "It may take a little time. Please don't let these other matters distract your mind too much from the man, Kars, and his tetanus vaccine."

"No," said Tracy.

He went out on the front porch. Bagby was sitting on the steps, hunched dejectedly forward with his coat collar turned up around his ears.

"Seen the paper?" he asked.

"No," Tracy answered.

"If you should look at it—in the right place—you would see that the police found a party named Winters in a joint off Call Street last night and that he was kind of dead. You would also see that this Winters was wanted in six states, and by the F.B.I., for various stunts he had pulled here and there. I just mention this in passing. I never seen the guy, myself. I never even heard of him. Nice day, ain't it?"

"Very nice," Tracy admitted.

THERE was a long curving drive up to the house that

sprawled awkward and massive over the top of the hill. The

curtains were drawn across the windows, but occasional little

twinkles of light gleamed through like the distant sparkle of

jewels, and there was a medley of voices and laughter and the

smooth rhythm of a dance orchestra.

"The joint is jumping," said Tracy's taxi driver, pulling in front of a line of parked cars and stopping beside the front entrance. "What they celebratin'?"

"I wouldn't know," Tracy said, getting out and paying him.

Tracy went up the steps, and the massive front door opened before he could touch the chime bell. A terrifically tall butler peered down at him over the bulge of an enormous starched shirt front. "Your name, sir?"

"Peter Tracy. I'm the cause of all the fuss here."

The butler permitted himself to smile. "Mr. Tracy! We're so happy you've arrived. We've been waiting for you. If you will just step into the bar—that door—I'll locate Mr. Stillson."

Tracy hesitated in the doorway he had pointed out. Bartholomew Stillson really believed in doing things up in first-class style. This was no temporary party bar. It looked like a high-powered cocktail salon, and it was nearly as large. It had a full size bar with stacks of glasses and bottles, and it also had a lot of customers at the moment. Men and women shoved and shouted cheerfully at each other and the three busy bartenders. Noise and billows of cigarette smoke thrust against the ceiling.

Tracy didn't know anyone and didn't know just what to do, so he stood there, watching. And then he did see someone he knew. On the far side of the room, standing alone against the wall. A tall, very thin man with a lined, aristocratic face and a precise gray mustache. It was Pappy. And not any Oliver Johnson of the defunct plumbing business, either. This was the genuine article. This was the man who had picked up Gloria LaTru at the Bull and Boar.

He was looking bored in a well-bred way, and then he noticed Tracy. He stared full at him, unwinking, for ten seconds, and then the skin seemed to whiten slightly across his high cheekbones. He began to move unobtrusively along the wall toward the door opposite Tracy.

Tracy began to move, too, edging through the crowd to head him off. The orchestra in the other room suddenly hit a couple of clashing chords and then galloped full-tilt into a conga. The crowd shoved and swirled away from the bar eagerly, and Tracy was caught in it and pushed along willy-nilly. He lost sight of Pappy, and then in the doorway of what was evidently the ballroom he shook free of the crowd and started back into the bar.

"Tracy! Here! Wait!"

It was Bartholomew Stillson. He was cornered over behind the orchestra in a group of women, and he waved his thick arms in wildly beckoning gestures.

Tracy flipped a hand in reply and went on into the bar. A few thirsty guests were gulping the last of their drinks, but Pappy wasn't among them. Tracy saw another door and went through it and along a hall into a lounge.

The lounge was empty, but one of the drapes against the end wall moved and swished slightly.

Tracy went over to it and pulled it aside. The tall french window in back of it was ajar, and he stepped through it into a formal, sunken garden. White gravel walks radiated in geometrical precision, and Tracy stared down the nearest one, squinting his eyes to see in the dim, diffused shadows.

A shot made a sudden dull thump in the night. Tracy stopped short, turning his head first one way and then the other, trying to locate the sound. Running feet skittered along one of the graveled paths near him.

Tracy started to run himself. He turned one right-angled curve, pounded down another stretch of empty path, turned sharply again. He stopped, then, skidding his heels with a little grating sound in the gravel.

Pappy was sprawled out on his face, across the path, all limply awkward now. Blood made a darkly spreading pool under his head, and the faint light reflected dimly from the revolver beside the relaxed fingers of his right hand.

TRACY knelt down slowly beside him. "Is he dead?" a voice

asked softly. Tracy jerked his head up, startled.

Mr. Brazil smiled at him and nodded. "I see you found him without my help. Was it necessary to shoot him?"

Tracy said: "I didn't...." He stood up. "What are you doing here?"

"I came seeking you," said Mr. Brazil. "Is he dead?"

"Yes."

Mr. Brazil sighed. "I was afraid so when I saw him. His name, aside from Pappy, is Patrick Moore—in case you didn't know. It is also sometimes Carter."

"What?" said Tracy blankly.

"Yes," said Mr. Brazil. "He is the owner and founder of the Borneo-Blasu Export Company. He is the man who hired Kars. He is the man who arranged the deal with the Japanese to sell me that fake vaccine."

Tracy stared at him, unbelieving. "Yes," repeated Mr. Brazil. "He is the one. I verified his connections once I started on his trail at your request. He was well-hidden, but I have quite extraordinary powers when I wish to use them. Did you know he was Carter?"

"No!" Tracy exclaimed.

"I really didn't think you did. That's why I came here seeking you. I was afraid that if he recognized you and you started questioning him or following him he would take some—ah—steps."