RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

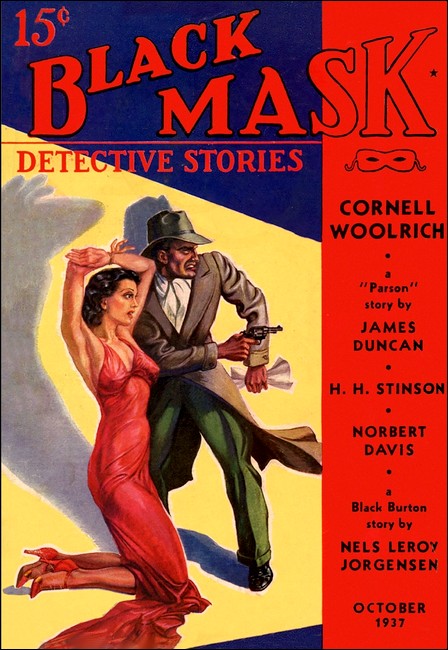

Black Mask, October 1937, with "Medicine for Murder"

REGORY saw it floating up toward him slowly—limp and dead and wavering a little in the deep blue-greenness of the water. He leaned farther over the edge of the boat to see it, and its eyes were staring up at him through the water, brown and wide with mute animal agony.

It was a dog; a small wire-haired terrier with the blunt, square muzzle of a thoroughbred. Its throat had been cut, and the wound was a deep purple slash against the fur, not bleeding now, with the severed muscles showing in gristly white strings.

Then the creamy white spray thrown back and over by the boat's knife-like prow covered the body with a rush, and it was gone to its grave deep under the water.

Gregory looked back over his shoulder. "Stop!" he ordered. The boatman was neat and natty in a white yacht-crew uniform. He was a young man, thick through the shoulders. His blond hair was bleached by sun and water. His face was deeply tanned. He moved a stubby-fingered hand on the throttle of the engine, and the boat slowed.

"What?" he asked, over the rumble of the motor sound. Gregory was looking back at the spot where he had seen the dog. He thought he saw it for a second in a vague white splotch near the surface, and then it was gone again.

"What're you looking for?" the boatman asked.

"I saw a dog," Gregory told him.

The boatman stared. "A dog? Here?"

"Yes," Gregory said. "Turn the boat around."

"Listen, mister. You mean you're tellin' me you think you saw a dog out here on the water? You ain't got the d.t.'s, have you? That'd be a hell of a thing for a doctor to have."

"Turn the boat," Gregory said. "I saw a dog. It was dead. I want another look at it."

"Why?" the boatman asked. "What do you want to go lookin' at dead dogs for? You ain't a dog doctor, are you?"

"Turn the boat," said Gregory.

Bruce Gregory was a slender man, neat and dark and unobtrusive in a tailored blue business suit. He had a high forehead with black hair receding sharply above his temples. He had thinly regular features, and his normal expression was that of a research scientist, detached and impersonal, yet observant. He kept his emotions carefully under control, and his facial expression never indicated what he was thinking. Only his eyes gave him away. They were a deep blue, wide set, warm and alive with human understanding, sympathy.

The boatman shrugged. "Why not? I get paid by the hour. I ain't a doctor. I've got no patients dyin' on me while I look for dead dogs."

The motorboat circled back toward the spot where Gregory had seen the dog, and he leaned again over the side, staring down into the shifting blueness of the water. He could see nothing but the moving flecks of light and shadow. After a moment, he straightened up.

"Well," said the boatman. "You got anything else you wanta look for? If you have, we can go back and get a diving helmet. Maybe we could find a dead cat."

"Take me to Van Tellens," Gregory said.

"Well, sure," said the boatman. "And about time, too, I think."

The sound of the motor changed to deep thunder, and the prow tilted up a little from the water. Small stinging drops of spray felt cold and salty on Gregory's lips. He was frowning a little. The incident of the dead dog bothered him. He liked dogs, and this one had been killed brutally and thrown into the water, and there was a reason for that, Gregory knew. He wanted to find out the reason. The bright, clear beauty of the late afternoon seemed to dull slightly, and he was remembering the silent agony in the dog's eyes.

The prow of the boat swung a little, as the boatman changed his course. The Van Tellen estate was dead ahead now, looming enormous and dark with its spired towers and narrow, close-set windows, brooding over the blueness of the bay. Even the sun turned the brightness of its rays away from the cold granite walls, and the house was darkly sullen and sinister.

There was a man standing on the edge of the small dock as the motor boat nosed gently in against the pilings. He was tall and bent a little bit, and he had an air of flabby looseness about him that was emphasized by the petulant droop of his wide mouth. He looked worn and tired, nervously irritable. His voice had a deep, measured resonance that Gregory knew was acquired, not natural.

"Dr. Gregory?" he asked anxiously, and when Gregory nodded, climbing out of the boat, he offered a pallid, white hand. "I'm Richard Danborn—Mrs. Van Tellen's attorney. I called you."

Gregory shook his hand. There were firm, strong muscles under the flabby skin.

"I've been waiting very anxiously," Danborn said.

"Don't blame me," said the boatman. "It ain't my fault we're late. I—"

"That will be all, Floyd," Danborn said flatly.

"Well, don't blame me, though, if we're late. I just follow orders around here."

Danborn's grayish face flushed. "Then try following this one. I said that would be all."

The boatman muttered sullenly to himself, tying up the boat.

Danborn swallowed hard. "This way, Doctor." He led the way off the dock.

The slope of the lawn down to the water's edge was graduated in neatly even terraces. Danborn and Gregory went up a brick walk with flat steps at intervals.

"These servants around here," Danborn said. "That's an example. Mrs. Van Tellen doesn't know how to handle them at all. This damned estate has given me more trouble...." He was silent for a second, then looked up side-wise at Gregory. "You'll pardon me, Doctor. I'm a little overwrought this afternoon. I suppose there are problems in all professions."

"There are," Gregory agreed.

"I called you to see Mrs. Van Tellen," Danborn said. "I'm very worried about her."

"Her regular physician?" Gregory questioned. "Why didn't you call him? I'm not familiar with her case."

Danborn shook his head irritably. "She has no regular physician. She's afraid of doctors. Never has one. You wouldn't be here now, if I hadn't insisted on calling you against her will."

Gregory stopped. "If Mrs. Van Tellen doesn't wish medical attention, there's nothing I can do about it."

"Wait," Danborn said anxiously. "Don't go. She really needs attention. Her fear of doctors is just an eccentricity. I can assure you, she has plenty of others.... Are you familiar at all with the history of the family?"

"No," said Gregory.

Danborn patted at his forehead nervously with a wadded handkerchief. "Let me tell you something about it. Mrs. Van Tellen had a brother by the name of Herman Borg. They came from a poor immigrant family, and they were left orphaned at an early age."

"I don't see what this—"

"Wait," said Danborn. "Herman Borg had a vicious and ungovernable temper. During his youth he quarreled with his sister, Mrs. Van Tellen. He never saw or communicated with her again during his life time. He made a great deal of money, and despite their quarrel, he left her all of his property. All this." Danborn waved an arm jerkily to indicate the house that towered darkly above them.

"He had no children?" Gregory asked, interested.

Danborn moved his shoulders. "One son. His wife died when the boy was born. Herman Borg quarreled with his son, too, and the boy ran away. I don't know as I blame Borg, at that. The boy was bad clear through. I wasn't acting as Borg's attorney at the time, but I know that Borg had a lot of trouble keeping him out of jail on several occasions. The boy died in a train accident in the West. He was bumming his way on freights."

"And Mrs. Van Tellen?" Gregory inquired. "Is she like her brother?"

Danborn shook his head. "Just exactly the opposite. She has no understanding of business at all. She's flighty and weak-willed. She gets one silly notion right after the other." His voice was suddenly emphatic, helplessly angry. "Now it's that damned dog!"

"Dog?" Gregory repeated.

"Yes. She's one of these sentimental women who get enormously attached to pets. She had a terrier. It was a cute little beast, I must admit, and I liked it. But she valued it more than she does her right hand. It disappeared today."

"You mean a wire-haired terrier?"

"Yes," Danborn answered. "Why?"

Gregory moved his shoulders. "Nothing. Just idle curiosity. It disappeared, you say?"

"Yes. Ran away, I suppose. I've arranged to put ads in all the papers and broadcast its loss over the radio. She'd give any reward to get it back. But, in the meantime, we've got to do something for her. She's been having one fit of hysterics after the other. I'm afraid shell do herself some permanent injury."

"She could very easily," Gregory admitted. "Does she often get attacks of hysteria?"

"Yes," Danborn said frankly. "You see, she was not at all successful either financially or in her marriage. When I found her to inform her of her legacy, she was scrubbing floors at night in an office building. Her husband wasn't working at all. I think she's healthy enough, as far as that goes, but it seems to me that at her age, such fits of hysteria are something to be considered seriously. I'd be greatly relieved if you would look at her and try to calm her."

"I can try," Gregory said. "Now that you've told me about it, I am interested—and not altogether from a medical standpoint. I make a hobby of solving little problems in human conduct."

Danborn whirled on him suddenly. "I remember now. Someone told me you often worked with the county medical examiner on criminal cases! You can't—do you mean—"

Gregory smiled at him reassuringly. "That's just another branch of my hobby. I'm interested in people and why they do what they do."

"But, here now! There's no crime. Mrs. Van Tellen—"

"I know," said Gregory. "I wasn't thinking of that. From what you said about her, she interested me as a person, that's all. I think you can trust me to keep professional confidences to myself."

"Certainly!" Danborn said quickly. "I know I can. No question about it. I apologize, Doctor. I didn't mean to doubt you for a moment. But, you see, Mrs. Van Tellen has had so much unfavorable publicity through this sudden wealth, that the thought was a little startling. I've tried to keep her out of the papers as much as I could, but I haven't been entirely successful. You can understand the possibilities. She has great news value. And some of her actions seem so foolish. You can't blame her for that. To be poor all her life, and then, when she was so old, to have several million dollars thrust on her without the slightest warning—it's enough to upset anyone's balance."

"I know," Gregory said.

Danborn mopped at his brow with the handkerchief. "You really must excuse me. I'm overwrought. Well, there's nothing to be gained, standing here. If you'll come with me, I'll take you to her."

DR. GREGORY and the lawyer, Danborn, went on up the brick walk. The sun was low on the horizon now, a flattened red disc surrounded by hazy pinwheels of mist that distorted its dying rays. The shadows were like long black bars laid across the front of the house. They went up broad granite steps to the dimness of the porch.

The big front door opened before they reached it, and a man sidled out very carefully. He was a small man, narrow-shouldered and stooping. His scanty brown hair was sweat-rumpled, straggling down loosely over his forehead. He wore big horn-rimmed glasses, and he stared through them at Danborn and Gregory with drunken owlishness.

"How do you do?" he said in thick, careful tones. "How do you do, all of you? I didn't expect such a large crowd, but come in. Come right in. I assure you that you are most welcome."

He took a step forward and then went teetering sidewise, jiggling his skinny arms to keep his balance. He bumped into the wall, slid slowly and gently down against it until he was sitting on the floor of the porch.

"Very comfortable chairs we have here," he said fuzzily. "Do come in." He closed his eyes and began to hum softly, beating time with an extended forefinger.

"That's Mr. Van Tellen," said Danborn contemptuously, making no effort to lower his voice. "The drunken old fool. He ends up in this state about the same time every day. He never before was in a position where he could afford all he wanted to drink. He's making up for lost time."

Gregory smiled a little, looking down at Van Tellen. "He's not the first to try it."

"Hell be trying it in a sanatorium pretty soon, if he doesn't let up," Danborn said in a disgusted tone. "He never was any good. He's been in jail for petty theft and drunkenness a dozen times in his career."

Van Tellen opened his eyes. "That, sir," he said, "comes dangerously close to being a slander. Eleven times is the correct number." He shut his eyes and began to hum again.

"Come on," Danborn said shortly.

The entrance hall was an immense, dim room with dark-paneled walls and an arched ceiling two stories high. Danborn's footsteps made thudding, hollow echoes as he led the way back into its shadows to the long, winding staircase. Gregory followed him up the stairs, into another long, dark hall. Danborn stopped in front of a closed door.

"Please," he said. "Remember what I've told you about her. Remember her history. Make allowances for anything she might say to you."

Gregory nodded. "Of course."

Danborn tapped on the door. The echoes traveled along the hall like ghostly footfalls. There was no answer, and Danborn knocked again, and then reached down and turned the knob. The door opened noiselessly.

"Mrs. Van Tellen," he said.

The bedroom was enormous, square and high-ceilinged. Wan, reddish light came through the narrow windows in the opposite wall, and the shadows were thick and heavy.

"Mrs. Van Tellen," said Danborn.

The bed was slantwise across one corner of the room. The carved oak head and foot gleamed dimly and richly lustrous. The thick covers humped a little in the center, and there was a head buried deep in the soft pillows with the white lace of a boudoir cap showing a little.

"Mrs. Van Tellen," said Danborn again.

There was no stir from the bed. The figure lying there didn't move. Gregory could see a hand now, reddened and wrinkled from years of toil, grasping the bed covers, rumpling them slightly. He stared at the hand, and his eyes were narrowed suddenly.

Danborn took a step or two closer. "Mrs. Van Tellen. Wake up. I've brought the doctor to see you."

The figure on the bed didn't move, didn't answer.

Danborn turned back to Gregory. "She's asleep," he murmured. "Perhaps that's best. A little rest.... Come downstairs and wait for a while. You can see her later."

"I'm afraid she isn't asleep," said Gregory.

Danborn stared at him. "What?"

Gregory leaned over the bed and touched the wrinkled hand gently. It was cold and heavy in his grasp. He knew before he tried that he would find no pulse beat in the wrist.

"She's dead," he said, and the words seemed to fall dully in the silence of the room.

"Dead," Danborn mumbled. "Dead." He swallowed hard. "Good God! No! She can't be!"

Gregory had pulled the covers back and was looking down into the thin, old face. There were lines in it, deep graven lines that told their own story of sorrow and poverty and ugly disappointment. But it was a kindly face, smiling now in death, and the blue-veined lids were closed over the tired eyes that had seen too little happiness.

"Dead!" Danborn exclaimed. "But—but how? What—"

She was turned on her side and Gregory saw the clotted stain on her nightgown. It was a dark brown in color, and it had spread slowly and touched the sheets under her. There was a narrow slit in the cloth of the gown just over her heart.

"You'd better call the police," Gregory said slowly. "She was murdered."

Danborn made a choking noise in his throat. His grayish face was suddenly waxen, and his eyes stared wildly at Gregory.

"You—No! It can't be! You're mad!"

"I'm sorry," said Gregory, "but you'd better call the police. Mrs. Van Tellen has been stabbed?'

"Oh, good God!" Danborn said, and wavered a little. "Stabbed! Somebody—" He turned and walked toward the door, his feet dragging leadenly.

Gregory listened to the clump of his feet going down the stairs, and then he heard a slight rustling noise close to him and the indrawn gasp of a breath. He whirled around. In two long steps he reached the painted screen that stood in the opposite corner of the room.

He struck it with his clenched fist, and the screen fell with a slashing rattle of sound. Then he was staring at a girl who was crouched back in the angle of the wall. Gregory could feel the blood pumping hard in his throat, and he released his breath in a little sigh.

"Well?" he said evenly.

She was small, only a little over five feet tall, and slender. She wore a white, sleeveless house dress. Her features were clean-cut, delicately even. They were distorted with terror now, and her white lips moved soundlessly.

"What are you doing here?" Gregory asked.

Her lips moved again, and the words came, half incoherent: "You said—she was dead?"

"Yes," said Gregory.

Her eyes were a wide, smooth brown, and now they glazed suddenly with tears. She put her hands up over them. She sobbed, quiet little choking sounds of agony.

"She was the only person who was ever kind to me."

"Who are you?" Gregory asked, more gently.

"Anne Bentley. I am—was Mrs. Van Tellen's companion."

"Why were you hiding here?"

She looked up at him slowly. "I was watching. I was afraid for her."

"Afraid?" Gregory repeated. "Why?"

She swallowed and then shook her head mutely.

"Who were you afraid of?" Gregory asked.

"You," said Anne Bentley.

The answer so astounded Gregory that for a second he was speechless. "Of me?" he said, recovering himself. "Me? Why?"

"I heard they were going to get a doctor for her. I was afraid—they've been torturing her.... I thought perhaps you were part of it, too. I wasn't going to let you hurt her! I won't stand for it any more! I won't! She'll not suffer—"

"No," said Gregory. "Never any more."

She stared at him. "No," she said numbly. "She's dead, isn't she? She can't suffer any more now. She's dead."

"Who was making her suffer?" Gregory inquired.

She clenched her fists. "They did everything they could to make her feel badly. Nasty, mean little things. They even stole her dog from her. And then, this!"

"Who?" Gregory said softly.

There was a shout downstairs and the rumbling pound of feet running along the hall. The sound seemed to bring the girl back to herself with a violent jerk.

"You said—stabbed?"

"Yes," Gregory said. "She was stabbed."

"I've got to get out! They can't find me here! They'll say that I—"

"Did you?" said Gregory.

She stared at him with dazed unbelief.

"Did you murder her?" said Gregory.

"No. No, no, no! You can't believe that!"

"How long were you here?"

"A half hour. I thought she was asleep. I came in very quietly, tiptoed behind this screen."

Gregory sighed. "She's been dead more than an hour. But I'm afraid you're going to have trouble making the police believe your story."

"Police," she said, and her voice thickened on the word. "They mustn't know. You can't tell them! You can't!"

"Why not?" said Gregory. "You haven't anything to fear if you are innocent."

"I can't face them! Don't you understand that? If they know I was here—they won't stop for questions."

Feet sounded on the stairs, climbing at a run.

Anne Bentley's face was a white twisted mask. "Let me go! Please! I'll explain. I'll tell you, but not now! I can't!"

Gregory stared at her for a dragging second. "All right," he said suddenly, stepping back. "I won't say anything if you meet me in a moment in that sunken rose garden at the side of the house and explain everything you've said. If you don't—"

"I'll be there! I can explain. But not now, not to the police."

She was gone, running lightly across the room. She went through a door at the side, and it closed softly after her.

Gregory picked up the screen and set it back in its place just as Danborn came back into the bedroom, followed by Mr. Van Tellen, weaving loosely.

"I called the police," Danborn said to Gregory. "You're sure there's nothing to do? Nothing to help her?"

"Nothing," Gregory said. "She's thoroughly dead."

Van Tellen sat down on the floor and leaned his back against the wall. "Aggie dead," he said thickly. "My, my. Hard to believe. Thought the old girl would outlive my seventy years. My, my." He closed his eyes and sighed. "I was very fond of her, too. Very sad. My, my." He began to hum slowly and softly to himself.

"There's the heir," Danborn said bitterly. "She didn't have any blood relations. He'll get all her money. Nice to think about, isn't it?"

Van Tellen opened his eyes. "Yes," he said. "Yes, it is. Now that you mention it." He began to hum again in a low, minor key.

RAY of dusk was changing into black of night as Gregory came down the steep stone steps into the sunken garden. It was a maze of narrow walks, winding and criss-crossing around clumps of shrubbery and flowers that had lost all their color and beauty in the darkness and were only weird-shaped masses of shadow.

Gregory wondered absently if he had made a mistake about the girl, Anne Bentley. He had told no one of her presence in the bedroom. Still, there was time for that, when the police arrived. If she didn't explain....

But he thought she would. Gregory had seen a great deal of human emotion, a great many people twisted and tortured by feelings that went down deeper than scalpel could probe. He was very rarely deceived. Anne Bentley's fear was not the fear of a criminal.

He strolled down one of the narrow paths, circled around its crooked length, back to the steps again. He stood there for a moment with the breeze blowing the rich, soft scent of the flowers across his face.

A foot made a quick, furtive scuffling noise on the walk behind him. Gregory had started to turn, and a man's voice said:

"Don't. Stand still."

Gregory's thin body stiffened. The round, cold ring of a gun muzzle touched the back of his neck. He could hear the light, shallow sound of the man's breathing just behind him. He could feel the light tremor in the steel of the gun muzzle, and he knew the man's hand was trembling.

"Walk ahead of me," the man said. The words were forced out in little spurts between the quick breaths. "Around that path to your right."

"Why?" said Gregory.

The man's voice went up a tone in jittery tenseness. "Walk! You hear me? Walk!" His nerves were screwed up tight, quivering. Gregory could hear the thin sound of hysteria creeping into the words, and he knew, the man would shoot in another split second.

"All right," he said evenly.

He walked steadily ahead in the darkness. The gun muzzle went away from his neck and punched him hard in the small of his back, urging him forward. He reached the end of the garden and slowed, and the man stepped on his heel from behind and swore in a breathless mutter.

"Up the steps. Walk right along close to that hedge."

Gregory's shoes grated on the stone of the steps, and then he was walking along the gravel path, hidden in the deep shadow of the high hedge.

"Straight ahead."

They went across the slope of a lawn that was lined with trees that were like dark, tall sentinels. The grass was a smooth carpet under foot, soft and damp and springy. The trees stretched down to the white gravel of a roadway, and there was a car parked in the shadows—a big sedan, gleaming sleekly black. Gregory stopped when he saw it

The gun muzzle prodded him. "Go on."

Gregory walked up beside the car. There was no one in it, and he stopped again.

"Well?" he said.

"Inside. In the front seat. You're gonna drive."

Gregory opened the door, slid carefully under the steering wheel. He heard the door latch click behind him, and he knew the other man was in the back seat The man's tenseness had suddenly relaxed, and he was talking and laughing in a thin giggle that had a shaky little catch in it

"Easy. Easy, huh, Doc? When you know how. Sure. Sure, it is. I knew it would be all the time. Sure. Start the motor."

Gregory touched the starter button, and the engine muttered lightly, smooth with multi-cylindered power.

"Drive right ahead." The man's voice was still shaky and he was trying to control the quickness of his breathing. He was afraid, and he had been afraid the whole time, and that had made him all the more dangerous. He wanted to talk now, smoothly and glibly, laughing, to prove he hadn't been afraid at all. "The lights. Doc You forgot them. You wanta see where you're goin', don't you? You don't want to hide from people, do you?"

Gregory snapped the switch, and the brilliant white cones bit through the darkness. The road curved evenly and slowly around ahead of them.

"You see," said the man. "We got the whole road all to ourselves. It ain't used much, on account it's much shorter and easier to come by the bay. But we got a lot of time. There's a gate comin' up ahead of us, but it's open and there ain't nobody takin' care of it, so don't let it worry you."

Gregory looked up at the rear-sight mirror, trying to see the face of the man behind him, but he was crouched close against the back of the front seat, out of line with the mirror. Gregory twisted a little in the seat, trying to bring him into its focus, and then he saw another figure. It was plastered flat against the rear window.

For a second Gregory thought his eyes were tricking him. The figure was no more than six inches high. It had a fuzzy mop of hair that made its head disproportionately large and springy, jiggling arms and legs that moved and wiggled in a weird dance, as though the figure were trying to climb up the smooth glass of the window.

The gun muzzle tapped him gently. "Straighten it out, Doc Don't get to day-dreaming."

Gregory turned the steering wheel a little, brought the big sedan back into the center of the road. He glanced again at the mirror. The figure was still there, dancing and jiggling and waving its springy arms. He realized suddenly what it was. It was a doll—a little black gargoyle doll that was fastened on a string so that it hung down over the back window.

They were at the end of the Van Tellen estate now, and the grounds began to narrow. Gregory caught a glimpse of the iron fence on both sides of them, dully slick in the headlights, that was closing in on both sides of them. The big gate loomed ahead. It was open, and there was no light in the small gate house beside it.

"Right on through," said the man with the gun.

The car slid through onto the white road. The headlights showed nothing on either side of it now but blackness, and the sound of the water was a slapping gurgle audible over the sound of the sedan's engine.

"This is the causeway, Doc," the man with the gun told him. "See, the estate's on a little bit of a spit of land stickin' right out into the bay. Water'd be clear around it except for this little neck right here. The old boy—Herman Borg—he built this road when he built the place. Cost him plenty, too."

The road stretched straight and white and empty ahead of them toward the black loom of the mainland.

"Stop the car, Doc!"

Gregory took the sedan out of gear and let it coast slowly to a stop at one side of the road. There was no room to turn out.

"Get out. This is the end of the line."

Gregory opened the door beside him, slid out into the center of the roadway.

"All right, Doc," said the man with the gun. "Take a look."

Gregory turned around slowly. The man was small and wiry and stunted with a white, cruelly grinning face and eyes that were beady specks, glittering. He held a big automatic, and his fingers seemed white and childish and thin twisted around its butt. There was a tell-tale nerve that kept twitching spasmodically in his thin cheek, jerking the side of his mouth.

"Well?" he said mockingly. "Know me?"

"No," said Gregory. He had never seen the man before. "Who are you?"

"Well, the name is Carter right now, I think. I change it so often it's hard to keep track."

"What did you bring me here for?" Gregory asked.

The man called Carter giggled softly; "Well, what do you think, Doc? It's nice and quiet here and nobody around but you and me. And there's lots of water right off the edge, and pretty deep. If you was to fall off, Doc, you'd probably come up a long ways away from here."

"You mean to kill me," said Gregory. His voice was even and low.

"That's it. Doc." He was very sure of himself, now, very confident.

"Why?" said Gregory. His eyes were narrowed on the black automatic. The thick barrel was lined up directly with his chest If it moved a fraction of an inch.... The muscles tensed along his back.

"Why?" said Carter. "Well, I don't see it's going to do you much good to know, Doc. In fact, that's your big trouble, Doc. You wanta know too much. You wanta go pokin' your nose in where it don't belong. So—good-by."

Gregory crouched a little. Carter's eyes were lidless and unblinking and bright watching him, and the barrel of the automatic was motionless, steady. The water made cold, chuckling sounds slapping itself in soft little waves against the side of the causeway.

"Good-by, Doc," said Carter in a whisper.

It came at them out of the darkness like a sudden, blasting juggernaut without the slightest warning. It was a heavy gray coupé, running without lights. The driver had been coasting it silently down the road, and now suddenly the engine roared in a wild snarl of sound, and it hurtled at them,

Gregory jumped back instinctively. Carter ducked and whirled. He would have got out of the way, but the car followed him. It followed him uncannily, horribly, like a roaring animal. He dodged again, his face a pasty white smear, and tripped, and then it hit him.

The fender took him in the middle of the back with a sickening sound like the thud of a heavy stone falling to the ground. It knocked him up in the air, his thin body sailed in a jerking, kicking arc. The water of the bay made a sullen, cold splash receiving it.

The gray coupé slid half around, crosswise of the causeway, and the tires ground on the very edge, caught with a sudden jar. The car teetered a little sidewise and then stood there silent.

Gregory could feel the cold wetness of perspiration on his forehead, and he drew in his breath in a long, choking gasp. His legs were numb and stiff under him. He took an uncertain step forward and then another, watching the gray coupé. There was no movement inside it, and he reached out with groping fingers, found the door handle and turned it

The driver was a small, limp bundle huddled down in the corner of the seat.

"Anne Bentley," Gregory said in a voice that sounded hoarsely strange to himself.

She looked up at him. Her brown eyes were widened abnormally, slick with a glassy, haunted horror.

"I killed him. I heard—when it hit. That sound. I saw him falling, kicking...."

"You saved my life," said Gregory gently. "You were following us?"

She nodded stiffly. "Yes. I was coming into the garden, when I saw him hold you up. I followed, and when I saw the car, I ran back and got this one. I use it to shop for the estate. I drove—watching your lights...."

"Thank you for that, Anne Bentley," Gregory said. "I won't forget it."

"I saw you and him standing here. I saw the gun. I couldn't do anything to stop him. I had to—"

"You had to do what you did," said Gregory. "It's something you'll never regret, I promise you that."

"Who was he?"

Gregory stared at her. "Don't you know?"

She shook her head. "No. I had never—seen him. I just saw his face when I hit—" She sobbed once in a sudden racking gasp.

"But listen to me," said Gregory, "You said something in Mrs. Van Tellen's room, something about someone who was torturing her. I thought this man Carter must be the one. Must be some way concerned with it. I never saw him before in my life either.

"Carter?" she repeated. "I never heard that name. There's been no one by that name around the house."

"Well, who was torturing Mrs. Van Tellen?" Gregory asked. "You did say something about that."

"I don't know. I tried to find out. I wanted to protect her, help her. It was mental torture. Little nasty things that kept happening to make her feel bad. The last was her dog. They stole that, I know. They knew how she loved it, how badly it would make her feel."

"But why?" Gregory said.

"I don't know. I tried to find out. But there was nothing, nothing definite. But everyone in the house was always watching her, making fun of her, remarking about the queer things she did and said. They were always hinting about insanity."

"Was Mrs. Van Tellen insane?" Gregory asked.

"No! No! She was not! They twisted the things she said and did and misinterpreted them to make them sound queer!"

"I know," said Gregory. "I know how easily that can be done."

"She was kind. She tried so hard to do what was right for everyone. She tried so hard to understand the way they acted." Anne Bentley's voice choked suddenly. "So hard. She was just an old woman, alone and bewildered. I wanted to help her, but—but now...."

"Now?" Gregory said softly.

"They'll send me back." Her voice was dull and low and hopeless.

"Send you back?" Gregory repeated. "Send you back where?"

She watched him for a long moment. "I'll have to tell you. You'll know soon enough anyway. I'm out on parole."

Gregory stared incredulously. "You mean—"

She nodded mechanically. "Yes. I was paroled from the State Prison for Women just seven months ago. I was paroled to the custody of Mrs. Van Tellen. You see, her husband was arrested for hitting a man with a beer bottle in a drunken brawl. My trial came up just before his. I was accused of shoplifting. Mrs. Van Tellen saw me in the court-room and she heard the trial."

"Yes?" Gregory said. "And then?"

"That was before Mrs. Van Tellen had any money. But she remembered. And when she did get her brother's fortune, she arranged for me to be paroled to her custody. She—she thought that I wasn't guilty."

"Then I think so, too," said Gregory. "I'm sure you—"

Her hands twisted together tensely. "Thank you for saying that. But I was guilty. I told Mrs. Van Tellen. You see, I was raised in an orphanage. I was adopted by a couple who lived on a farm. They wanted a servant, not a child. I couldn't stand it with them. I ran away. I was all alone in the city. I had no money—only one shabby house-dress. I stole a dress from a store, I thought if I could look well, I could get work. I meant to pay for it. I really did."

"I know that," said Gregory. "And it's all past now, and gone."

"No!" she said tensely. "No, it isn't! Don't you see? That's why I was afraid of the police. They'll find out I'm a—a convict. They'll never look further for the murderer as soon as they know that."

"They will," said Gregory. "Because I'll see that they do."

"But even then I'll have to go back. Because I was paroled to Mrs. Van Tellen. And she's—she's gone."

"They'll never send you back," said Gregory. "Do you hear that? They'll never take you back again. I swear that."

Site looked up. "You'll help—me?" Gregory smiled, and the steely lights were gone from his eyes, and they were warm and understanding and sympathetic.

"You've lost one friend today," said Gregory. "But you've found another. Now listen to me. I think it best that you don't make an appearance at the house until I can go back and see just what has been happening. Here's my card. The address is on it. My office adjoins my house, and the waiting-room is never closed at any time. It will be open now. You go there and wait for me. Will you do that?"

Anne Bentley took the card unhesitatingly. "Yes," She stared at him for a long moment. "Thank you," she said in a whisper.

OCTOR GREGORY drove the big black sedan around the smooth curve of the white graveled drive and stopped it near the side entrance of the Van Tellen house. He was fumbling for the door catch when there was a sudden incoherent shout and a thick figure came running headlong across the dark sweep of the lawn.

"Hey, you! What in the hell do you think—"

It was the boatman who had brought Gregory across the bay. Floyd, Danborn had called him. He dug his heels into the gravel and stopped short, staring at Gregory.

"Well?" said Gregory.

Floyd drew in a long, deep breath. "Doc," he said, swallowing. "You kinda stop me. Are you really as screwy as you act?"

"Just what are you talking about?" Gregory asked.

"Well, look. I hear some screechin' up here, and I come up and find the old lady is dead. Murdered, they tell me. And everybody's goin' nuts lookin' for you. And now here I find you takin' a nice leisurely tour of the estate. Don't you ever tend to your business?"

"I'm better able to judge what my business is than you are," Gregory said evenly, getting out of the car.

"I dunno," said Floyd. "I really dunno about that, Doc. Did you ever think of havin' your mind examined?"

Gregory ignored him. He walked up the steps to the flat porch. He turned around to look back as he opened the door. Floyd was still standing beside the car, staring after Gregory and shaking his head slowly and incredulously.

The upper hall was bright with light when Gregory came up the stairs. There was no one in sight but a uniformed policeman lounging against the wall beside the door of Mrs. Van Tellen's bedroom. He straightened up when Gregory appeared.

"Oh, hello, Doc!" he greeted. "Where you been? Everybody's been lookin' all over hell for you."

"I was busy," Gregory said.

"Well, go on in, now that you're here. Old Goat Face and Keegan are still snoopin' around inside."

Gregory pushed the door open and went into the bedroom. Doctor Chicory was standing beside the big bed, carefully repacking his instrument case. He was a thin, dry little man with white hair and a white beard. He chewed gum constantly, and the waggle of his bearded jaw did make him look startlingly like a goat. He wore rimless nose-glasses that glinted brightly when he moved his head. He had a soft, drawling voice that could be viciously sarcastic when he chose to make it so.

"Ah, Doctor," he said cordially. "Good evening."

"Good evening," Gregory said. "Sorry I'm late."

Chicory smiled at him. They were old friends.

"Quite all right. No hurry."

Detective Keegan was standing with his back to the room, looking out the window, and he turned around now. He was a soft, fat man with a pinkly dimpled face. His wide mouth dropped in a petulant pout. He drew his breath in deeply and expelled it with a little hiccough.

"Now, Doctor Gregory," he said importantly. He talked in a pompous whine. He hated Gregory. He hated his quiet efficiency, his air of grave courtesy. He hated him all the more because he knew Gregory was well aware of how Keegan felt and didn't care in the slightest. "I don't want to quarrel with you, not at all. But you know your duties as a doctor."

"Thanks," said Gregory.

The soft bulge of Keegan's neck above his collar reddened. "When you report a death like this, or when you are in attendance when it is reported, then you're supposed to stay here until the authorities arrive! You don't have any right to tamper in things like this! You have no official position!"

Gregory smiled at him in an amused way. Before he could answer, Chicory spoke in his dry, precise voice as calmly as if he were discussing the weather.

"Keegan, I've often told you that both your face and your voice grated on any person with decent sensibilities. You can't do much about your face, unfortunately, but you can keep your mouth shut, and I suggest you do it."

Keegan choked incoherently, staring at him with furious, bulging eyes.

Chicory smiled benignly. "My dear Keegan, I am the County Medical Examiner, and you are only a detective—and not a very good one at that. Just keep it carefully in mind. Doctor Gregory and I wish to discuss this case. Either keep still or get out."

Keegan found his voice. "I won't! I've got a right—"

"Not while I'm in charge, you haven't," Chicory said.

"I want to ask him about that girl!"

"Girl?" Gregory repeated. "What girl?"

"That damned ex-convict companion of Mrs. Van Tellen's! Did you see her around here?"

"Is she involved?" Gregory inquired.

Keegan's eyes were brightly malicious. "A little! Yeah, I'd say she was! Her fingerprints were on the knife!"

"What knife?" Gregory asked, puzzled. "Do you mean you've found the murder weapon?"

Keegan stared at him incredulously. "Found it! Hell, yes! It was stickin' right in the old lady! How could we help but find it?"

Gregory turned his head to look at Chicory.

The little medical examiner nodded once, precisely. "Yes, Doctor. Keegan very seldom gets things correctly, but this time he happens to be right. The knife was in the wound that killed Mrs. Van Tellen, and the girl's fingerprints were on the hilt."

"There was no knife in the wound when I saw it," Gregory said.

"What!" Keegan exclaimed. "Why, you're crazy—" He stopped and let out his breath slowly. He began to smile in a sly, knowing way. "Oh. So that's the way it is. I understand she's very pretty and—"

"Keegan!" said Chicory.

"Well, he's trying to protect her! You can see that! He's just lying."

"Keegan," said Chicory. "Get out of here."

"I won't! You and he will get together and cook up a bunch—"

"Ah," said Chicory in a quietly satisfied away. He began to take off his coat.

Keegan backed up two steps. His plump cheeks lost their color. His eyes were worried, and they shifted uneasily from Gregory, who was still smiling a little, to Chicory.

"Well, I didn't really mean...."

Chicory removed his glasses and laid them carefully on his coat. Keegan walked very quickly to the door. He stopped there and turned around.

"Well, you're in charge here now, but you just wait."

Chicory took a step toward him, and Keegan went through the door and slammed it defiantly after him. Chicory picked up his coat and put it on again. He put on his glasses and winked at Gregory.

"Yellow," he said. "As yellow as a pound of butter, our friend Keegan. I like to watch him squirm. That's the trouble with holding a public office like this one of mine. You are forced to associate with scum."

"Could I see the knife you found in the wound?" Gregory asked.

Chicory shook his head. "I'm sorry. It isn't here. The fingerprint expert took it back to his office with him to check it more carefully. I'm afraid there's no doubt about it, though. Doctor. The fingerprints were the girl's. The expert located a number of her prints in her room and they checked."

Gregory frowned. "I can't understand the knife being in the wound. It actually was not there when I first saw the body. I examined the wound, not very extensively, but I would certainly have seen the knife if it had been there."

"Surely," said Chicory. "It means that someone put it in the wound after you saw the body. But the fingerprints?"

Gregory shrugged. "I don't know. What kind of a knife was it?"

"A long, slim dagger. A poignard. It was one of those medieval things. Keegan found where it had come from. It had been hanging up in the front hall on the wall, sort of an ornament."

"Speaking of ornaments," Gregory said, "have you ever seen anything like this before?"

He reached in his pocket and brought out the black gargoyle doll that had been hanging against the window of the black sedan. He held it up by the string attached to its neck, and the springy arms and legs jiggled in a fantastic shimmy. The thing had a painted face that was sketched in a set, cannibalistic leer with thick red lips and goggling eyes. The body was stuffed cloth. The legs and arms were tensed wires.

Chicory stared, wide-eyed. "Where on earth did you get that?"

"I found it," Gregory said. "Ever see anything like it before?"

"Yes. Wait, now." Chicory scratched his head. "Where did I see the thing? Oh, yes! My grandniece!"

"What?" Gregory asked.

"My little grandniece has one just exactly like it. She was playing with it the last time I was over at their house. I remember I remarked about it. I didn't think it was a very cheery looking object for a child to be playing with. But then, as is usually the case in my family, I was overruled."

"Do you know where your grandniece got it?" Gregory asked.

Chicory nodded. "Surely. My nephew and his wife went to the opening of the Harlem Club. These little beggars were given away as favors on the opening night."

"The Harlem Club?" Gregory repeated.

"Yes. I gave them a good talking to for going there. That place is a fire-trap if I ever saw one. People think because a building sets near the water it won't burn, but that doesn't always follow."

"The place is closed now, isn't it?" Gregory asked.

"Yes!" said Chicory, "and a good thing, too! I don't approve of places like that. Brings in a bad element. Makes more trouble for the authorities."

"Who ran the place?"

"Fellow by the name of Steve Karl. Very unsavory character. I was against granting him a license when he applied for it, but that's all the good it did me."

"Is he still in town?"

"Yes. Lives out at the place there. He's looking for some new capital to reopen, I understand. I hope he doesn't find it. I'd like to see that rat's nest burn down with him in it. Why do you ask?"

"I think I'd like to have a talk with Steve Karl," Gregory said slowly.

IS house was a tall colonial, white and graceful and distinguished-looking on the wide, tree-lined curve of Elm Street. Gregory dismissed his taxi at the corner and walked up the hill toward his home. Through the mask of the tall shrubbery in front he could see the cheerfully glowing white light that marked the side-door into his office.

As he told Anne Bentley, that light was always on and the office door was always open. It was not usual for a doctor of Gregory's standing to be on service twenty-four hours a day. But he liked it that way. He enjoyed his work. Each person that paused under the white light and opened that door was a problem for him to solve.

His footsteps sounded crisp and firm on the walk as he went around to the side of his house. He hesitated a second in front of the office door with his hand on the knob. And then, remembering that she would probably be afraid waiting there alone for this long time, he spoke her name cheerfully:

"Hello, Anne Bentley."

There was no answer from inside. Gregory's voice died in cold little echoes. He frowned in a worried way, pushed the door open. He stopped short, standing in the doorway, staring incredulously.

The neat white office was a shambles. The center table had been tossed over on its side, and the magazines that had been on top of it were scattered from one end of the room to the other. The glass case containing his extra instruments in steel-shining rows had been smashed open. A chair lay in one corner, its metal arms and legs twisted grotesquely.

"Anne Bentley!" Gregory called. His voice sounded hollow and empty in the wrecked room.

He stepped forward, and he saw something that had been hidden behind the tipped table. There was a man lying on the floor, face down, in a crumpled heap. The bright, shining steel handle of a surgeon's scalpel protruded from his back.

Gregory didn't need to look twice to know that the man was dead. He didn't need to look twice to know that the surgeon's scalpel was one of his own, taken from the smashed glass case.

Slowly he knelt down beside the stiffened figure. He lifted it a little, turned it on its back. Its arm flopped on the floor with an ugly thump.

Gregory was looking down into the grayish, lined face of the attorney, Richard Danborn. Danborn's tired eyes stared back at him, glassy and lifeless. There was a blue welt-like bruise on his forehead, running slant-wise above his left eye. Gregory touched it gently with his fingers.

After a moment Gregory stood up. His face looked older now, bleak and harsh and determined. Taking his keys from his pocket, he went over to the door that led into his private office, unlocked it. He snapped on a light, crossed to the flat, polished desk. He took a stubby-barreled police revolver from one of its drawers, slipped it into his coat pocket. He went out of the office, around to the garage where he kept his small black coupé. He climbed in and headed into the night. He drove for a long time, out of town and toward the bay, and when he stopped, he let the coupé nose into the shallow ditch beside the road. He had switched off his headlights several hundred yards before he had reached this point, and he got out of the car now. Its door made a muffled thump closing.

There was fog on the bay, and it was creeping slowly inland, pushing up on the land in rolling, puffing billows that changed shapes fantastically as they moved. Gregory stood beside the car, his coat buttoned close around his throat, watching around him. The darkness was a soft, oily black, and except for the creep of the fog, nothing else moved. There were no lights anywhere.

Gregory walked slowly down the road. It turned around the edge of a hill that sloped down sharply. The fog seemed to be waiting for him like a placid white lake, and he walked down into it, feeling for his footing. He moved ahead very slowly and quietly in the dim grayness.

A creaking sound to his right brought him up short. He stood tensely, watching the white object that stood beside the road, until he saw that it was inanimate. It was a white, square pillar with a metal sign attached to it by wires that creaked rustily when the night wind touched them.

Stepping closer, Gregory could make out the bright, slanted lettering on the sign:

WELCOME! HARLEM CLUB DINE—DANCE—DRINK

There was a wavering side road that turned off here, the thin gravel on its surface scoured into the mud underneath it in twin grooves from the pressure of auto tires. Gregory followed it through the fog until he saw the black loom of a building ahead of him.

It was long and low and rambling, shed-like, with a disproportionately high cupola over what had once been the entrance. There had been a neon sign on top of the cupola, bright enough to be seen far out on the bay. It was gone now, probably seized by one of the Harlem Club's many creditors, and only the support remained, looking like a steel gallows, gauntly sinister in the fog.

There were no lights in the building. Gregory felt his way along a wall, still following the dim car tracks. They turned around a long L-shaped garage extension of the building and then stopped before warped, wooden doors.

Gregory hesitated there for a while, listening and watching, and then he slid his fingers in behind the bulge of a door and pulled gently. The door moved a little, sliding noiselessly on oiled runners. Gregory peered through the opening, but there was nothing to be seen inside except the oily heave of the blackness.

He pulled the door open farther, slipped cautiously in. The mud on his shoe-soles slid on the cement flooring. He could smell gasoline and oil and the indefinable pungency of wet leather.

After a moment of blind, pointless groping, he breathed a soft curse to himself and reached inside his tightly buttoned coat. He took a small clip flashlight from his vest pocket. Holding his revolver ready in his right hand, he pressed the clip. The small circle of light cut brilliantly through the darkness, showed the mud-spattered side of a parked roadster.

"Hold it," said a voice flatly. "Hold the light right where it is, Doc. I'm covering you."

The flashlight beam wavered for a second and then was steady. Gregory stood rigid.

Shoes scuffed on the cement. Gregory listened to the sound of them, listened to them come cautiously closer, approaching from behind.

"The gun," the flat voice said. "Drop it, now."

Gregory dropped the light instead. Instantly, as soon as his thumb released the clip, the white beam shut itself off, and the flashlight tinkled on the floor in the darkness. Gregory stepped sidewise and swung the revolver back-handed in a flat, swishing arc.

There was a sodden thud as the barrel struck flesh. The voice gasped in a choking bubble of sound. Gregory struck again, heard the grate of the gun-butt as it struck on bone, felt the jar in his wrist.

Feet scraped on the cement. Someone fell with a lunging clatter, sprawling full length.

Gregory waited, breathing hard. He knew from the feel of that last blow that whoever it was he had struck was unconscious now, if not dead. He moved a little, feeling cautiously with his feet for the prone form. He touched its warm, inert limpness.

Then, suddenly, without the slightest warning sound, something hit the side of his head with tremendous, crushing force. He fell sidewise in the darkness, and it seemed that he was falling for long moments before he felt himself strike the coldness of the cement floor. He remembered feeling that, and then he felt nothing more.

IGHT shone hot against the closed lids of Gregory's eyes. He didn't move. He made no attempt to open his eyes until he had conquered the first chaotic thoughts of returning consciousness. In a few seconds he knew that his brain would take control again, and he would remember just what had happened.

There was an ache spreading slowly from a spot over his right temple. He considered the ache, diagnosing it, and that brought memory back.

He remembered going into the garage of the Harlem Club, remembered the voice that had spoken out of the darkness. He remembered striking at that voice, and he remembered the crushing blow that had smashed him down.

It must not have been as hard a blow as it seemed. Or perhaps the brim of his hat had lessened its force. Gregory knew that he had only suffered a slight concussion. Now, recalling all that, and with his mind steady and clear, he moved a little and opened his eyes.

The light was an unshaded bulb, dangling down from a streaked, dirty ceiling on a length of tangled wire. Gregory was lying on his back on something soft and lumpy under him. He moved one hand slightly, felt a crumpled blanket. He was lying on a cot.

"Good evening," said a soft, slyly amused voice.

Gregory turned his head further and saw a man. He was sitting on a stool tilted back against the wall. He was a tall, ungainly man with stick-like arms and legs. The skin on his face was a pallid, pasty white, stretched paper-thin over the protruding jut of his nose. His hair was a dead black, glittering with oil, plastered flat against his bony head. His eyes were blue, a smooth, glossy blue that had no life behind them. He had a smooth and suavely sinister smile.

"Steve Karl," Gregory said.

"Why, yes," the man said. "I'm very pleased and flattered to be recognized so promptly."

Gregory moved again on the bed, starting to sit up.

"No," said Karl. "No, my dear doctor. Just lie there for a few moments, and you will feel much better. Of course, I wouldn't venture to give an expert like you medical advice—mine is just practical counsel." He raised his right hand casually. Gregory's police revolver rested lightly in his knobby, yellowish fingers. "A nice gun, Doctor. And I needed a spare."

Gregory relaxed and looked slowly around the room. The floor was littered with crumpled papers and snuffed-out cigarette butts. There was no furniture except the cot on which Gregory lay and the stool Karl was sitting on.

"This," said Karl, "is what serves me for an office at the moment. I apologize for it. You see, my creditors moved in on me recently and moved right out again, taking everything along with them that wasn't nailed down. In case you are interested, we are upstairs over the club."

"Thank you," said Gregory evenly.

"Yes," said Karl. "I'd heard that you were a pretty hard proposition, Doctor, but watching you come out from under the way you did just now makes me believe I underestimated you, at that. You're certainly hard to get excited, aren't you?"

"Yes," said Gregory.

"Does your head feel better now?"

"Yes," said Gregory. "May I sit up?"

Karl nodded. "But don't do anything else. I'm not quite such easy game as the men I hire. You've done pretty well with them, haven't you, Doctor? What happened to Carter, by the way?"

"He fell into the bay."

"Ah," said Karl. "I like the way you put it. Fell into the bay, eh? Well, that's one gone. And you just fixed another up very nicely down in the garage. I had to send him into town to get repaired—in the custody of the one that put you down. That leaves us all alone to have our little talk. Just how did you get on to me, Doctor?"

"Through Carter."

Karl's thin lips tightened. "That yellow little rat! Did he talk before he—fell into the bay?"

"No," said Gregory. "But he took me for a ride in a car. There was a little doll in the car, the kind you gave out on your opening night. I traced that. There was no registration or ownership certificate in the car and the license plates were forgeries. I thought the doll must have some relation to Carter, or else he would have removed it when he stole the car."

"That fool," said Karl. "That damned fool. He was drunk the night we got that doll, and he got the notion that the thing was good luck for him. Damn him and it, too. But it was clever, Doctor. Very clever of you."

Gregory watched him silently.

"You've been damned clever all the way through," Karl said. "Yes. Ill admit it. You had a better plan than I did, and you went about it in a slicker way."

"Plan?" said Gregory.

"Oh, yes. I figured it out very quickly; give me credit for that. You had a hold on that girl. You could make her do what you said. And she could manage old man Van Tellen. He was crazy about her. So you had the girl murder Mrs. Van Tellen. And there you had the whole business right in the palm of your hand. The old man controlled the money, the girl controlled him, and you controlled the girl. And how about Danborn? Isn't he in it somewhere?"

"Not now," said Gregory.

"What do you mean by that?" Karl asked.

"He's dead."

Karl moved tensely on his stool. "When did that happen?"

"Tonight," said Gregory evenly. "I found him lying on the floor of my office, where your men had left him."

"Yes," said Karl. "But Jerry only sapped him. Jerry's the guy that smeared you down in the garage. Jerry didn't crack him hard enough to kill him. Jerry don't make mistakes like that."

"I noticed the bump on his head," Gregory said. "But now he's got a scalpel in his heart."

Karl swallowed, and his smile grew a little strained as he watched Gregory. "You mean you stuck him in the back when you found him lying there?" He swallowed. "You know. Doc, I'm beginning to think I'm damn lucky to come out at the top of this pile. I don't like the way you do business."

"What was your plan?" Gregory asked.

Karl moved his thin shoulders. "Easy. I'm paying a few guys around the Van Tellen place. I spoiled her for a softy, and I needed some capital. I knew she had the reputation for being a little on the screwy side, and I was just taking advantage of that. Pretty soon I was going to move in and protect her in a big way under the threat that the servants and the other boys around there would testify that she was insane. I would have put it over, all right. She's a soft touch for something like that. But I was playing for small change compared with you."

"Yes," said Gregory. "Very small change."

"Not any more," said Karl in an ugly tone. "Oh, no. You fixed up the setup for me now. I'll take it over."

"Will you?" said Gregory.

"Yes, but not the way you were going to work it. I don't want any part of that girl. I don't want her mixing in it. I'll work on the old man direct."

"Mr. Van Tellen?" Gregory questioned.

"Sure. Who else? He's getting all the old girl's money, but he won't have it very long. I'm having him brought over here for a little session as soon as I get rid of you. He'll listen to reason after the boys work him over for a while. Then, after this, he'll be my silent partner—or else."

"And the girl?" Gregory asked calmly. "Anne Bentley?"

"She goes with you," said Karl. "Deep down under. You and she and Carter are all going to be drinking a lot of water together."

"She's here?" said Gregory.

"Sure. In the other room—tied up. The boys had to rough her a little when they grabbed her in your office, but they didn't hurt her much."

"Ah," said Gregory quietly. "That's all I wanted to know."

"Is it now?" said Karl, getting up very slowly. "I'm glad of that, because you aren't going to get a chance to know very much more, Doc. We're going visiting. The girl's in the room through that door. Go on in. I want you to carry her. That'll just keep your hands busy."

Gregory stood up. The movement redoubled the throbbing ache in his head, but his eyes were steady and cool and watchful.

"Take it easy," said Karl "Easy and slow, Doc. You won't catch me like you did those other guys."

He followed Gregory step by step with the cocked revolver level in his hand. Gregory walked to the door he had pointed out, opened it.

It was a dim, dark cubby-hole of a room, and Anne Bentley was lying in a crumpled heap under the boarded-up window. She was conscious. Gregory caught the shadowed movement of her head, turning toward them, heard the bubbling moan of her breath from under the gag that cut across her face whitely.

Gregory knelt down beside her. "This gag," he said. "It's too tight. It's choking her."

"Never mind that," Karl said thinly. "She won't feel it for very long. Pick her up."

Gregory raised the girl's slim body in his arms, stood up.

"Back through this way," Karl ordered, stepping aside and gesturing with the revolver. "Out that door."

Gregory carried Anne Bentley across the office. He fumbled clumsily for the knob on the door, opened it, went down a long, dim hall. A stairway made a dark well ahead of him.

"Down," said Karl.

He had a flashlight, and its beam made a moving pool in the darkness, showed the worn steps leading down steeply. There was another door at the bottom. Gregory pushed it open, and wet fog billowed into the hall bringing the salt smell of the hay in along with it.

"Outside," Karl said.

Loose boards clumped, moving a little under Gregory's feet. This was the bay side of the club building, built up on pilings above the flat, slick swell of the water.

"Straight ahead," Karl said. "There's a pier."

Gregory walked slowly into the smoky dimness. The boards of the little pier were wet and slippery under his feet, and he could feel the structure sway a little with their combined weight. The fog pressed in softly close around them.

"It's about time," said a voice ahead of them. "You think I wanta wait here all night?"

The slim, graceful lines of a speed boat took shape ahead of them, rising and falling a little with the movement of the water. Gregory recognized it as the same boat that had carried him out to the Van Tellen estate earlier. And Floyd, the boatman, was standing up in it now, holding it against the end of the dock. He was wearing a slicker with the collar strapped tight around his neck.

"I didn't know you were here already," Karl said.

"Why didn't you look?" Floyd demanded. "This is a hell of a place to leave a guy sittin' all night."

"Shut up," Karl said flatly. "I haven't got time to argue with you. Did you bring old Van Tellen?"

"Sure. Right here." Floyd moved his foot casually and touched a limp, bedraggled bundle that rolled loosely on the bottom of the boat.

"Carry him inside," Karl ordered.

"The hell with that," said Floyd. "I'm sick of carryin' the old coot around. Don't make any difference, anyway. He's out cold. He drank enough to sink a battleship today, and I tapped him on the head before I brought him along. Leave him in here. He ain't gonna bother anybody."

"All right," Karl agreed. "Get down in the boat. Doc. We're all goin' for a little ride. Take it easy."

LIMBING stiffly down into the boat, Gregory held Anne Bentley close against him. He sat down on one of the seats, still holding her. His hands were freed now of the weight of carrying her, and instantly he began to work at the knots in the thin cord that bound her wrists. His hands were concealed under her body. He could feel the muscles in her arms strain as she tried to help him.

Karl jumped down into the boat. "All right, Floyd. You start up. Take it slow. I don't want anybody getting curious."

"Hell," Floyd said, "they couldn't see nothin' in this fog if they was."

The stubby revolver glistened in Karl's hand. "I said take it slow."

"All right," Floyd said sullenly. He bent over the engine. It coughed once, then again, and began to purr softly. The boat rocked a little, began to move away from the dock.

Gregory's strong fingers loosened the last knot in the thin cord. Then, under cover of the darkness and working with one long-fingered hand, he loosened the too-tight gag. He heard Anne Bentley give a long sigh of relief.

The pier disappeared behind them, and then there was nothing but the soft whiteness of the fog all around them. The only sound was the swish of the prow cutting through the water, the muffled mutter of the engine. Anne Bentley twisted slightly in Gregory's lap. He knew she was reaching for the cord that bound her ankles, and he touched her shoulder approvingly.

"This is your last ride, Doc," said Karl. "Enjoy it."

"I am," said Gregory evenly. "I'm enjoying it very much. This is just about the place you dropped the dog overboard, isn't it, Floyd?"

Floyd was a dark, thick figure sitting at the stern of the boat. The oilskin coat rustled softly as he moved a little, turning to look toward Gregory. He didn't say anything.

"Dog?" said Karl blankly. "What dog?"

"Mrs. Van Tellen's dog," Gregory said. "He killed it before he killed Mrs. Van Tellen."

There was a long silence with the thump of the boat's motor sounding faint and far away.

"Killed Mrs. Van Tellen!" Karl repeated. "Are you nuts. Doc?"

Floyd's voice was thick and slow. "Sure. He's screwy. I told you he was."

"That babe you're holdin' killed Mrs. Van Tellen," Karl said. "Everybody knows that. I heard it over the news broadcast this afternoon. They found her fingerprints on the knife that was stuck in the old lady."

"The knife was put in the wound after Mrs. Van Tellen was dead," Gregory said. His voice was gentle and low, indifferent. "Floyd was saving it for that. You thought he was working for you all the time, didn't you, Karl? He wasn't. You were working for him."

"What—" said Karl. "What the hell, here?"

Floyd sat in the stern, unmoving. His face was a dark, smeared blur under the brim of his cap. He didn't speak.

"Floyd killed the dog," said Gregory. "He hated Mrs. Van Tellen. He wanted to do anything that would hurt her. She suspected him for some reason. He knew it. He couldn't waste any more time, then. He killed her. And he killed Danborn. And one other."

Karl's voice was faint with shock. "One other?"

"Mr. Van Tellen," said Gregory. "He's not drunk or unconscious. He's dead. If you don't believe it, touch him."

Automatically Karl leaned over the limp, soggy bundle on the bottom of the boat. He touched the glistening paleness that was its face. His breath rattled in his throat.

"Floyd!" he snarled. "Damn you! He's cold! He's dead! You—" He swung half around.

Anne Bentley slid off Gregory's lap, and Gregory leaned over her and reached under the next seat, groping for the object that glinted metallically there. His fingers closed over the smooth wet handle of a short wrench.

"That's all," said Floyd. "That's about all. Drop the gun, Karl, and you let that wrench stay where it is, Doc!" He had picked up a shotgun from under his seat, and the short sawed-off barrels glinted coldly. "It's loaded with buckshot—both barrels. Ever see what a shotgun would do at this range? It would tear all three of you up like shredded wheat."

Gregory let go of the wrench and straightened up slowly in his seat. Karl's limp fingers loosened on the revolver, and it clattered on the bottom of the boat.

"Floyd," Karl said unbelievingly. "Floyd, what—"

"You're smart, Doc," said Floyd. "Oh, you're pretty smart, all right. You probably figured out why I killed 'em, didn't you?"

"I think so," said Gregory. "I think it was because you are Herman Borg's son."

"Yeah," said Floyd. "I am. The cops was after me out West, so I faked that train accident. That was some stumble-bum hobo that got bumped. Not me. But the cops grabbed me anyway on another job and stuck me away for five years. But they never savvied who I really was. And then when I got out, I found my lousy old man had kicked the bucket and left all his dough to this Van Tellen outfit."

"And you set out to get it back," said Gregory.

"Sure. And I'm gonna. They're all dead. Floyd, the boatman, is gonna disappear. And then pretty soon Herman Borg's son is gonna turn up and claim the dough his old man left. Old lady Van Tellen didn't leave no will. I saw to that. And neither did this stew-bum husband of hers. I'm all that's left. I get it."

"And Danborn?" Gregory said. "Why did you kill him?"

"That dirty rat! He's the one who thought up the idea for my old man to give his money to the Van Tellens. I fixed him for that. I was trailin' him, lookin' for a chance. I seen Karl's boys jump him in your office. I finished the job after they scrammed with the girl. The knife in the old lady—that surprised you, didn't it, Doc? I seen the girl pick it up once. I was always watchin'. I glommed on to it and saved it. I didn't get a chance to stick it in the old lady before you showed. But I did afterwards. How'd you know, Doc?"

"You were in such a hurry to get back to the estate when you were taking me across," Gregory said. "And then the way you acted about the dog. You knew Mrs. Van Tellen's terrier was missing. All her servants had been hunting for it. But you didn't say anything about it when I saw the dead dog, and you tried to keep me from examining it closely, Then, later, when I drove up in the car Carter had tried to take me for a ride in, you recognized the car. You thought it was Carter driving, and you were all set to bawl him out for showing himself so openly. You covered up your surprise very well when you saw I was driving, but I knew you were covering up."

"I knew you did, damn you," said Floyd. "But it set me back on my heels so hard when I saw it was you that I couldn't think of anything sensible to say."

"Floyd," Karl said quickly. "Now listen, Floyd. This is fine, boy. You've certainly arranged things nicely. We've got everything fixed now. I'll help you—"

"The hell you will," said Floyd coldly. "I don't need any help from you. I'll help you—right over the side with these other two nosey punks!

"No!" Karl said frantically. "Floyd! You wouldn't!"

Floyd chuckled thinly, and then there was a thick, low muttering sound close to them in the fog. A round spot of light bloomed out suddenly like an incredibly bright mechanical eye and outlined them all in its ghastly white glow.

"All right!" a voice shouted from behind the light. "All right, you! Pull up! This is a police boat!"

"Police!" Karl screamed.

Floyd swung around, a jerkily moving black silhouette cut out of the gray blanket of fog. The light glittered coldly on the double barrel of the shotgun. Its report was a flat, blasting roar of sound. Glass tinkled, and the light was suddenly gone.

The speed boat jumped forward with a surge of power, heeling over as Floyd turned it in a sharp circle. His voice came hoarsely:

"Sit still! All of you! I've still got one barrel left!"

The engine of the invisible police boat drowned out his voice in a thundering crash of sound as it suddenly accelerated. The noise drummed in the fog, closing in invisibly, and then the gray knife-like prow loomed just over them.

Gregory threw himself down and side-wise, covering Anne Bentley with his body. The gray prow hit the speed boat in the side, knocked it up clear out of the water, rolled it over with a sharp, ripping crunch. Karl shrieked in sudden unbearable agony.

Gregory clutched Anne Bentley close against him, felt himself falling dizzily through the air. The coldness of the water closed over them like a great smooth hand. Gregory struggled and fought frantically, kicking up toward the surface. Anne Bentley was limp in his arms, unresisting.

Their heads broke surface suddenly, and a voice yelled just above them:

"Here! Here! Here they are! This side!"

Gregory stroked toward the gray wall that was the police boat's side. There was a man leaning far out toward him over the water. Gregory looked up and saw dimly the jutting white goatee and sparkling spectacle lenses of Doctor Chicory. Then, over to his left, he saw a swirl of yellow slicker sinking under the surface.

Rope came rushing down toward Gregory. He gripped it with his free hand, pulled himself against the side of the boat and hoisted Anne Bentley up high enough for Doctor Chicory to grasp her. As soon as he felt her weight released from his arm, he let go of the rope, swam away from the boat toward the left.

"Gregory!" Chicory's voice shouted incoherently. "This way! Wait! Are you crazy?"

Gregory drew in a deep gulp of air, dove. He went plummeting down beneath the slick swell of the surface in a long, driving slant. The inky blackness of the water shut off all sensation except the laboring pound of blood in his temples. The pressure squeezed at his lungs, and little red streaks danced madly in front of his eyes.

Then one clawing hand touched smooth rubbery wetness below him. He grasped at it frantically, caught it. He had the collar of Floyd's slicker, but the weight of Floyd's body dragged it down with a leaden weight. He fought against it, kicking and threshing, while his lungs burned for the want of oxygen. He lost all sense of direction, all sense of progress. He didn't know whether he was going upward toward the surface or sinking. But he locked his fingers on the slicker collar and fought grimly.

Blackness began to wash out the red streaks that danced before his eyes. He knew he was losing consciousness. He concentrated all his will power on one last desperate struggle, and his head broke the surface of the water. He breathed through his open mouth in great, broken sobs, and the freshly moist air seemed to flow all through his body, restoring strength and feeling.

"There! There!" Chicory's voice shouted thinly, and a rope slapped the water beside him.

Gregory grasped the rope, felt himself hauled forward and then upward. Hands caught him and his limp burden. He sank down on wet boards, still breathing in sobbing gasps.

"You fool!" said Chicory, staring anxiously down at him. "Were you trying to commit suicide?"

"Girl?" Gregory whispered.

"Oh, she's all right," Chicory said shortly. "Just fainted. Scared, then the shock of the water. She's coming around."

"Floyd," Gregory said. "Take—care—him."

"Sure," said Chicory. He straightened up and shouted. "Here. Take care of this man. All he needs is a little artificial respiration."

Slicker-clad policemen knelt down beside Floyd's limp body, began to work on him expertly.

"Where'd you come from?" Gregory asked.

Chicory's glasses glittered as he turned around. "Well, you told me you were going to see Karl, and when one of his men was dumped on the lawn of the County Hospital with a cracked skull, and the policeman on the beat reported a dead man in your office, why I thought somebody ought to come around and see what was happening. So I commandeered this police boat so I could sneak up on Karl's place from the bay side. We were lost in the fog, here, and drifting along when we heard your voices and your motor. But what in the devil did you want to risk your life rescuing that fellow for? I saw him shoot at our searchlight."

"Evidence," said Gregory, breathing more strongly now. "Floyd, himself, is all the evidence I've got that he killed Mrs. Van Tellen and Mr. Van Tellen and Danborn. I hope he feels like confessing when he comes around."

"He will," said Chicory meaningly. "Oh, yes. He will, all right. I'll see to that."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.