RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

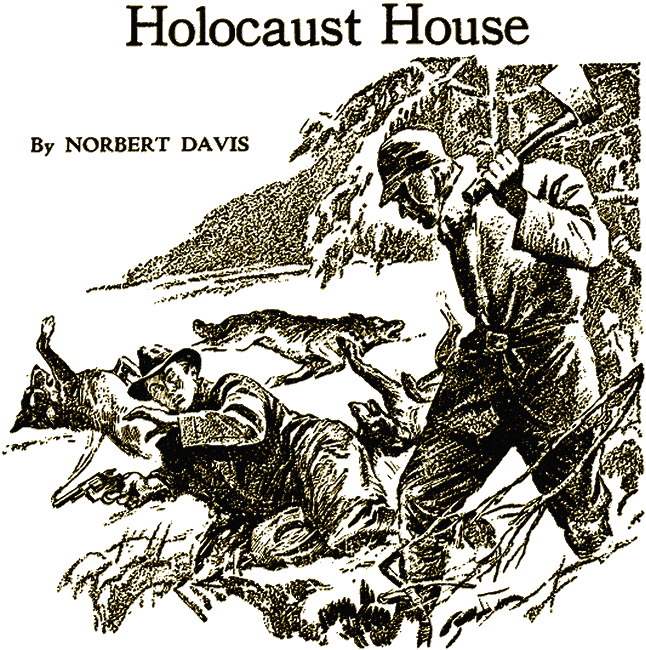

Argosy, 16 November 1940, with first part of "Holocaust House"

"Stop!" Doan shouted, but the madman was swinging back his ax.

WHEN Doan woke up he was lying flat on his back on top of a bed with his hat pulled down over his eyes. He lay quite still for some time, listening cautiously, and then he tipped the hat up and looked around. He found to his relief that he was in his own apartment and that it was his bed he was lying on.

He sat up. He was fully dressed except for the fact that he only wore one shoe. The other one was placed carefully and precisely in the center of his bureau top.

"It would seem," said Doan to himself, "that I was inebriated last evening when I came home."

He felt no ill effects at all. He never did. It was an amazing thing and contrary to the laws of science and nature, but he had never had a hangover in his life.

He was a short, round man with a round pinkly innocent face and impossibly bland blue eyes. He had corn-yellow hair and dimples in his cheeks. At first glance—and at the second and third for that matter—he looked like the epitome of all the suckers that had ever come down the pike. He looked so harmless it was pitiful. It wasn't until you considered him for some time that you began to see that there was something wrong with the picture. He looked just a little too innocent.

"Carstairs!" he called now. "Oh, Carstairs!"

Carstairs came in through the bedroom door and stared at him with a sort of wearily resigned disgust. Carstairs was a dog—a fawn-colored Great Dane as big as a yearling calf.

"Carstairs," said Doan. "I apologize for my regrettable condition last evening."

Carstairs' expression didn't change in the slightest. Carstairs was a champion, and he had a long and imposing list of very high-class ancestors. He was fond of Doan in a well-bred way, but he had never been able to reconcile himself to having such a low person for a master. Whenever they went out for a stroll together, Carstairs always walked either far behind or ahead, so no one would suspect his relationship with Doan.

He grunted now and turned and lumbered out of the bedroom in silent dignity. His disapproval didn't bother Doan any. He was used to it. He got up off the bed and began to go through the pockets of his suit.

He found, as he knew he would, that he had no change at all and that his wallet was empty. He found also in his coat pocket one thing that he had never seen before to his knowledge. It was a metal case—about the length and width of a large cigarette case, but much thicker. It looked like a cigar case, but Doan didn't smoke. It was apparently made out of stainless steel.

Doan turned it over thoughtfully in his hands, squinting at it in puzzled wonder. He had no slightest idea where it could have come from. It had a little button catch at one side, and he put his thumb over that, meaning to open the case, but he didn't.

He stood there looking down at the case while a cold little chill traveled up his spine and raised pin-point prickles at the back of his neck. The metal case seemed to grow colder and heavier in his hand. It caught the light and reflected it in bright and dangerous glitters.

"Well," said Doan in a whisper.

Doan trusted his instinct just as thoroughly and completely as most people trust their eyesight. His instinct was telling him that the metal case was about the most deadly thing he had ever had in his hands.

He put the case carefully and gently down in the middle of his bed and stepped back to look at it again. It was more than instinct that was warning him now. It was jumbled, hazy memory somewhere. He knew the case was dangerous without knowing how he knew.

The telephone rang in the front room, and Doan went in to answer it. Carstairs was sitting in front of the outside door waiting patiently.

"In a minute," Doan told him, picking up the telephone. He got no chance to say anything more. As soon as he unhooked the receiver a voice started bellowing at him.

"Doan! Listen to me now, you drunken bum! Don't hang up until I get through talking, do you hear? This is J.S. Toggery, and in case you're too dizzy to remember, I'm your employer! Doan, you tramp! Are you listening to me?"

Doan instantly assumed a high, squeaky Oriental voice. "Mr. Doan not here, please. Mr. Doan go far, far away—maybe Timbuktu, maybe Siam."

"Doan, you rat! I know it's you talking! You haven't got any servants! Now you listen to me! I've got to see you right away. Doan!"

"Mr. Doan not here," said Doan. "So sorry, please."

He hung up the receiver and put the telephone back on its stand. It began to ring again instantly, but he paid no further attention to it. Whistling cheerfully, he went back into the bedroom.

He washed up, found a clean shirt and another tie and put them on. The telephone kept on ringing with a sort of apoplectic indignation. Doan tried unsuccessfully to shake the wrinkles out of his coat, gave up and put it on the way it was. He rummaged around under the socks in the top drawer of his bureau until he located his .38 Police Positive revolver. He shoved it into his waistband and buttoned his coat and vest to hide it.

Going over to the bed, he picked up the metal case and put it gently in his coat pocket and then went into the front room again.

"Okay," he said to Carstairs. "I'm ready to go now."

It was a sodden, uncomfortable morning with the clouds massed in darkly somber and menacing rolls in a sky that was a threatening gray from horizon to horizon. The wind came in strong and steady, carrying the fresh tang of winter from the mountains to the west, where the snow caps were beginning to push inquiring white fingers down toward the valleys.

Doan stood on the wide steps of his apartment house breathing deeply, staring down the long sweep of the hill ahead of him. Carstairs rooted through the bushes at the side of the building.

A taxi made a sudden spot of color coming over the crest of the hill and skimming fleetly down the slope past Doan. He put his thumb and forefinger in his mouth and whistled. The taxi's brakes groaned, and then it made a half-circle in the middle of the block and came chugging laboriously back up toward him and stopped at the curb.

Doan grabbed Carstairs by his studded collar and hauled him out of the bushes.

"Hey!" the driver said, startled. "What's that?"

"A dog," said Doan.

"You ain't thinkin' of riding that in this cab, are you?"

"Certainly I am." Doan opened the rear door and shoved Carstairs expertly into the back compartment and climbed in after him. Carstairs sat down on the floor, and his pricked ears just brushed the cab's roof.

The driver turned around to stare with a sort of helpless indignation. "Now listen here. I ain't got no license to haul livestock through the streets. What you want is a freight car. Get that thing out of my cab."

"You do it," Doan advised.

Carstairs leered complacently at the driver, revealing glistening fangs about two inches long.

The driver shuddered. "All right. All right. I sure have plenty of luck—all bad. Where do you want to go?"

"Out to the end of Third Avenue."

The driver turned around again. "Listen, there ain't anything at the end of Third Avenue but three abandoned warehouses and a lot of gullies and weeds."

"Third Avenue," said Doan. "The very end."

THE three warehouses—like three blocked points of a triangle—looked as desolate as the buildings in a war-deserted city. They stared with blank, empty eyes that were broken windows out over the green, waist-high weeds that surrounded them. The city had been designed to grow in this direction, but it hadn't. It had withdrawn instead, leaving only these three battered and deserted reminders of things that might have been.

"Well," said the taxi driver, "are you satisfied now?"

Doan got out and slammed the door before Carstairs could follow him. "Just wait here," he instructed.

"Hey!" the driver said, alarmed. "You mean you're gonna leave this—this giraffe..."

"I'll only be gone a minute."

"Oh no, you don't! You come back and take this—"

Doan walked away. He went around in back of the nearest warehouse and slid down a steep gravel-scarred bank into a gully that snaked its way down toward the flat from the higher ground to the north. He followed along the bottom of the gully, around one sharply angling turn and then another.

The gully ended here in a deep gash against the side of a weed-matted hill. Doan stopped, looking around and listening. There was no one in sight, and he could hear nothing.

He cupped his hands over his mouth and shouted: "Hey! Hey! Is there anyone around here?"

His voice made a flat flutter of echoes, and there was no answer. After waiting a moment he nodded to himself in a satisfied way and took the metal case out of his pocket. Going to the very end of the gully, he placed the case carefully in the center of a deep gash.

Turning around then, he stepped off about fifty paces back down the gully. He drew the Police Positive from his waistband, cocked it and dropped down on one knee. He aimed carefully, using his left forearm for a rest.

The metal case made a bright, glistening spot over the sights, and Doan's forefinger took up the slack in the trigger carefully and expertly. The gun jumped a little against the palm of his hand, but he never heard the report.

It was lost completely in the round, hollow whoom of sound that seemed to travel like a solid ball down the gully and hit his eardrums with a ringing impact. Bits of dirt spattered around his feet, and where the case had been there was a deep round hole gouged in the hillside, with the earth showing yellow and raw around it.

"Well," said Doan. His voice sounded whispery thin in his own ears. He took out his handkerchief and dabbed at the perspiration that was coldly moist on his forehead. He still stared, fascinated, at the raw hole in the hillside where the case had rested.

After a moment he drew a deep, relieved breath. He put the Police Positive back in his waistband, turned around and walked back along the gully to the back of the warehouse. He climbed up the steep bank and plowed through the waist-high weeds to the street and the waiting taxi.

The driver stared with round, scared eyes. "Say, did—did you hear a—a noise a minute ago?"

"Noise?" said Doan, getting in the back of the cab and shoving Carstairs over to give himself room to sit down. "Noise? Oh, yes. A small one. It might have been an exploding cigar."

"Cigar," the driver echoed incredulously. "Cigar. Well, maybe I'm crazy. Where do you want to go now?"

"To a dining car on Turk Street called the Glasgow Limited. Know where it is?"

"I can find it," the driver said gloomily. "That'll be as far as you're ridin' with me, ain't it—I hope?"

The Glasgow Limited was battered and dilapidated, and it sagged forlornly in the middle. Even the tin stack-vent from its cooking range was tilted drunkenly forward. It was fitted in tightly slantwise on the very corner of a lot, and as if to emphasize its down-at-the-heels appearance an enormous, shining office building towered austere and dignified beside it, putting the Glasgow Limited always in the shadow of its imposing presence.

The taxi stopped at the curb in front of it. This was the city's financial district, and on Sunday it was deserted. A lone street car, clanging its way emptily along looked like a visitor from some other age. The meter on the taxi showed a dollar and fifty cents, and Doan asked the driver:

"Can you trip that meter up to show two dollars?"

"No," said the driver. "You think the company's crazy?"

"You've got some change-over slips, haven't you?"

"Say!" said the driver indignantly. "Are you accusing me of gypping—"

"No," said Doan. "But you aren't going to get a tip, so you might as well pull it off a charge slip. Have you got one that shows two dollars?"

The driver scowled at him for a moment. He tripped the meter and pocketed the slip. Then he took a pad of the same kind of slips from his vest pocket and thumbed through them. He handed Doan one that showed a charge of a dollar and ninety cents.

"Now blow your horn," Doan instructed. "Lots of times."

The driver tooted his horn repeatedly. After he had done it about ten times, the door of the Glasgow Limited opened and a man came out and glared at them.

"Come, come, MacTavish," said Doan. "Bail me out."

MacTavish came down the steps and across the sidewalk. He was a tall gaunt man with bony stooped shoulders. He was bald, and he had a long draggling red mustache and eyes that were a tired, blood-shot blue. He wore a white jacket that had sleeves too short for him and a stained white apron.

Doan handed him the meter charge slip. "There's my ransom, MacTavish. Pay the man and put it on my account."

MacTavish looked sourly at the slip. "I have no doubt that there's collusion and fraud hidden somewhere hereabouts. No doubt at all."

"Why, no," said Doan. "You can see the charge printed right on the slip. This driver is an honest and upright citizen, and he's been very considerate. I think you ought to give him a big tip."

"That I will not!" said MacTavish emphatically. "He'll get his fee and no more—not a penny!" He put a ragged dollar bill in the driver's hand and carefully counted out nine dimes on top of it. "There! And it's bare-faced robbery!"

He glared at the driver, but the driver looked blandly innocent. Doan got out and dragged Carstairs after him.

"And that ugly beastie!" said MacTavish. "I'll feed him no more, you hear? Account or no account, I'll not have him gobbling my good meat down his ugly gullet!"

Doan dragged Carstairs across the sidewalk and pushed him up the stairs and into the dining car. MacTavish came in after them, went behind the counter and slammed the flap down emphatically.

Doan sat down on a stool and said cheerfully: "Good morning, MacTavish, my friend. It's a fine bonny morning full of the smell of heather and mountain dew, isn't it? Fix up a pound of round for Carstairs, and be sure it's none of that watery gruel you feed your unsuspecting customers. Carstairs is particular, and he has a delicate stomach. I'll take ham and eggs and toast and coffee—a double order."

MacTavish leaned on the counter. "And what'll you pay for it with, may I ask?"

"Well, it's true that I find myself temporarily short on ready cash, but I have a fine Swiss watch—"

"No, you haven't," said MacTavish, "because I've got it in the cash register right now."

"Good," said Doan. "That watch is worth at least fifty—"

"You lie in your teeth," said MacTavish. "You paid five dollars for it in a pawn shop. I'll have no more to do with such a loafer and a no-good. I've no doubt that if you had your just deserts you'd be in prison this moment. I'll feed you this morning, but this is the last time. The very last time, you hear?"

"I'm desolated," said Doan. "Hurry up with the ham and eggs, will you, MacTavish? And don't forget Carstairs' ground round."

MacTavish went to the gas range, grumbling under his breath balefully, and meat made a pleasantly sizzling spatter. Carstairs put his head over the counter and drooled in eager anticipation.

"MacTavish," said Doan, raising his voice to speak over the sizzle of the meat, "am I correct in assuming I visited your establishment last night?"

"You are."

"Was I—ah—slightly intoxicated?"

"You were blind, stinking, pig-drunk."

"You have such a pleasant way of putting things," Doan observed. "I was alone, no doubt, bearing up bravely in solitary sadness?"

"You were not. You had one of your drunken, bawdy, criminal companions with you."

MacTavish set a platter of meat on the counter, and Doan put it on top of one of the stools so that Carstairs could get at it more handily. Carstairs gobbled politely, making little grunting sounds of appreciation.

Doan said casually: "This—ah—friend I had with me. Did you know him?"

"I never saw him before, and if my luck lasts I'll never see him again. I liked his looks even less than I do yours."

"You're in rare form this morning, MacTavish. Did you hear me mention my friend's name?"

"It was Smith," said MacTavish, coming up with a platter of ham and eggs and a cup of coffee.

"Smith," said Doan, chewing reflectively. "Well, it's a nice name. Don't happen to know where I picked him up, do you?"

"I know where you said you picked him up. You said he was a stray soul lost in the wilderness of this great metropolis and that you had rescued him. You said you'd found him in front of your apartment building wasting away in the last stages of starvation, so I knew you were blind drunk, because the man had a belly like a balloon."

"In front of my apartment," Doan repeated thoughtfully. "This is all news to me. Could you give me a short and colorful description of this gentleman by the name of Smith?"

"He was tall and pot-bellied, and he had black eyebrows that looked like caterpillars and a mustache the rats had been nesting in, and he wore dark glasses and kept his hat on and his overcoat collar turned up. I mind particularly the mustache, because you kept asking him if you could tweak it."

"Ah," said Doan quietly. He knew now where he had gotten the instinctive warning about the metal case. Drunk as Doan had been, he had retained enough powers of observation to realize that the mysterious Smith's mustache had been false—that the man was disguised.

Doan nodded to himself. That disposed of some of the mystery of the metal case, but there still remained the puzzle of Smith's identity and what his grudge against Doan was.

AT that moment the front door slammed violently open, and J.S. Toggery came in with his head down and his arms swinging belligerently. He was short and stocky and bandy-legged. He had an apoplectically red face and fiercely glistening false teeth.

"A fine thing," he said savagely. "A fine thing, I say! Doan, you bum! Where have you been for the last three days?"

Doan pushed his empty coffee cup toward MacTavish. "Another cup, my friend. I wish you'd tell the more ill-bred of your customers to keep their voices down. It disturbs my digestion. How are you, Mr. Toggery? I have a serious question to ask you."

"What?" Toggery asked suspiciously.

"Do you know a man whose name isn't Smith and who doesn't wear dark glasses and doesn't have black eyebrows or a black mustache or a pot-belly and who isn't a friend of mine?"

Toggery sat down weakly on one of the stools. "Doan, now be reasonable. Haven't you any regard for my health and well-being? Do you want to turn me into a nervous wreck? I have a very important job for you, and I've been hunting you high and low for three days, and when I find you I'm greeted with insolence, evasion and double-talk. Do you know how to ski?"

"Pardon me," said Doan. "I thought you asked me if I knew how to ski."

"I did. Can you use skis or snow-shoes or ice skates?"

"No," said Doan.

"Then you have a half-hour to learn. Here's your railroad ticket. Your train leaves from the Union Station at two-thirty. Get your heavy underwear and your woolen socks and be on it."

"Why?" Doan asked.

"Because I told you to, you fool!" Toggery roared. "And I'm the man who's crazy enough to be paying you a salary! Now, will you listen to me without interposing those crack-pot comments of yours?"

"I'll try," Doan promised.

Toggery drew a deep breath. "All right. A girl by the name of Sheila Alden is spending the first of the mountain winter season at a place in the Desolation Lake country. You're going up there to see that nothing happens to her for the next three or four weeks."

"Why?" Doan said.

"Because she hired the agency to do it! Or rather, the bank that is her guardian did. Now listen carefully. Sheila Alden's mother died when she was born. Her father died five years ago, and he left a trust fund for her that amounts to almost fifty million dollars. She turns twenty-one in two days, and she gets the whole works when she does.

"There's been a lot of comment in the papers about a young girl getting handed all that money, and she's gotten a lot of threats from crack-pots of all varieties. That Desolation Lake country is as deserted as a tomb this time of year. The season don't start up there for another month. The bank wants her to have some protection until the publicity incident to her receiving that enormous amount of money dies down."

Doan nodded. "Fair enough. Where did her old man get all this dough to leave her?"

"He invented things."

"What kind of things?"

"Powder and explosives."

"Oh," said Doan, thinking of the deep yellow gouge the metal case had left in the hillside. "What kind of explosives?"

"All kinds. He specialized in the highly concentrated variety like they use in hand grenades and bombs. That's why the trust he left increased so rapidly. It's all in munitions stock of one kind and another."

"Ummm," said Doan. "Did you tell anyone you were planning on sending me up to look after her?"

"Of course. Everybody I could find who would listen to me. Have you forgotten that I've been looking high and low for you for three days, you numb-wit?"

"I see," said Doan vaguely. "What's the girl doing up there in the mountains?"

"She's a shy kid, and she's been bedeviled persistently by cranks and fortune hunters and every other kind of chiseler." J. S. Toggery sighed and looked dreamily sentimental. "It's a shame when you think of it. That poor lonely kid—she hasn't a relative in the world—all alone up there in that damned barren mountain country. Hurt and bewildered because of the unthinking attitude of the public. No one to love her and protect her and sympathize with her. If I weren't so busy I'd go up there with you. She needs someone older—some steadying influence."

"And fifty million dollars ain't hay," said Doan.

J.S. Toggery nodded, still dreamy. "No, and if I could just get hold of—" He snapped out of it. "Damn you, Doan, must you reduce every higher human emotion to a basis of crass commercialism?"

"Yes, as long as I work for you."

"Huh! Well, anyway she's hiding up there to get away from it all. Her companion-secretary is with her. They're staying at a lodge her old man owned. Brill, the attorney who handles the income from the trust, is staying with them until you get there. There's a caretaker at the lodge too."

"I see," said Doan, nodding. "It sounds interesting. It's too bad I can't go."

Toggery said numbly: "Too bad you... What! What! Are you crazy? Why can't you go?"

Doan pointed to the floor. "Carstairs. He disapproves of mountains."

Toggery choked. "You mean that damned dog—"

Doan snapped his fingers. "I've got it. I'll leave him in your care."

"That splay-footed monstrosity! I—I'll—"

Doan reached down and tapped Carstairs on the top of his head. "Carstairs, my friend. Pay attention. You are going to visit Mr. Toggery for a few days. Treat him with consideration because he means well."

Carstairs blinked balefully at Toggery, and Toggery shivered.

"And now," said Doan cheerfully. "The money."

"Money!" Toggery shouted. "What did you do with the hundred I advanced you on your next month's salary?"

"I don't remember exactly, but another hundred will do nicely."

Toggery moaned. He counted out bills on the counter with trembling hands. Doan wadded them up and thrust them carelessly into his coat pocket.

"Aren't you forgetting something, Mr. Doan?" MacTavish asked.

"Oh, yes," said Doan. "Toggery, pay MacTavish what I owe him on account. Cheerio, all. Goodbye, Carstairs. I'll give you a ring soon." He went out the door whistling.

Toggery collapsed limply against the counter, shaking his head. "I think I'm going mad now," he said. "My brain is simmering like a teakettle."

"He gets me that way too," said MacTavish. "Why do you put up with him?"

"Hah!" said Toggery. "Listen! If he wasn't the best—the very best—private detective west of the Mississippi, and if this branch of the agency didn't depend entirely on him for its good record, I would personally murder him!"

"I doubt if you could," said MacTavish.

"I know it," Toggery admitted glumly. "He could take on you and me together with Carstairs thrown in and massacre all three of us without mussing his hair. He's the most dangerous little devil I've ever seen, and he's all the worse because of that half-witted manner of his. You never suspect what he's up to until it's too late."

DOAN rolled his head back and forth on the hard plush cushion, opened his eyes and blinked politely. "You were saying something?"

The conductor's face was red with exertion. "Yes, I was sayin' something! I been sayin' something for the last ten minutes steady! I thought you was in a trance! This here is where you get off!"

Doan yawned and straightened up. He had a crick in his neck, and he winced, poking his finger at the spot.

The roadbed was rough here, and the old-fashioned tubular brass lamps that hung from the arched car top jittered in short nervous arcs. The whaff-whaff-whaff of the engine exhaust sounded laboriously from ahead. The car was thick and murky with the smell of cinders. Aside from the conductor, Doan was the only occupant.

Doan asked: "Do you stop while I get off, or am I supposed to hop off like a hobo?"

"We'll stop," said the conductor.

He might have been in telepathic communication with the engineer, because that's just what they did right then. The engine brakes screeched, and the car hopped up against the bumpers and dropped back again with a breath-taking jar, groaning in every joint.

"Is he mad at somebody?" Doan asked, referring to the engineer.

"Listen, you," said the conductor indignantly. "This here grade is so steep that a fly couldn't walk up it without his feet were dipped in molasses first."

Doan took a look at the empty seats. "You didn't make this trip especially on my account, did you?"

"No!" The conductor was even more indignant at the injustice of it. "We got to run a train from Palos Junction through here and back every twenty-four hours in the off season to keep our franchise. Otherwise you'd have walked up. Come on! We ain't got all night to sit around here."

Doan hauled his grip from the rack, pausing to peer out the steamed window. "Is it still raining?"

The conductor snorted. "Raining! It's rainin' down on the coast maybe, but not here. You're eight thousand feet up in the Rocky Mountains, son, and it's snowin' like somebody dumped it out of a chute."

Doan was no outdoorsman, and he hadn't taken what J.S. Toggery had said about skis and snow-shoes at all seriously.

"Snowing?" he said incredulously. "Why, it's still summer!"

"Not up here," said the conductor. "She'll make three feet on the level, and it's driftin'. Get goin'."

Still incredulous, Doan hauled his bag down the aisle and through the end door of the car. This was the last car, the only passenger coach, and when he stepped out on the darkness of the platform the snow and the wind slapped across his face like a giant icy hand. Doan sputtered indignantly and went staggering off balance down the iron steps and plumped into powdery wet coldness that congealed above the level of his thighs.

The engine whistle gave a triumphant, echoing scream.

The conductor was a dim, huddled form with one gaunt arm stretched out like a semaphore. His voice drifted thinly with the wind.

"That way! Through snow-sheds... along spur..."

The engine screamed again, impatiently, and bucked the train ahead.

Doan had dropped his bag, and he scrambled around in the snow trying to find it. "Wait! Wait! I've changed my mind."

The red and green lights on the back of the car blinked mockingly at him, and the conductor's howl came blurred and faint through the white swirling darkness.

"Station... quarter-mile... snow-sheds..."

The engine wailed like a banshee, and the snow and the darkness swallowed the sound of it up in one gulp.

"Well, hell," said Doan.

He spat snow out of his mouth and wiped the cold wetness of it off his face. He located his bag and hauled it out into the middle of the tracks. He had a topcoat strapped on the side of the grip, and he unfastened it now and struggled into it. He was thinking darkly bitter thoughts about J.S. Toggery.

With the collar pulled up tight around his throat and his hat pulled down as far it would go over his ears, he stood huddled in the middle of the tracks and looked slowly and unbelievingly around him. He had a range of vision of about ten feet in any given direction; beyond that there was nothing but snow and blackness. There was no sign of any other human, and, aside from the railroad tracks, no sign that there ever had been one here.

"Hey!" Doan shouted.

His voice traveled away and came back after a while in a low, thoughtful echo.

"This is very nice, Doan," said Doan. "You're a detective. Make a brilliant deduction."

He couldn't think of an appropriate one, so he shrugged his shoulders casually, picked up his bag and started walking along the track in the direction the conductor had pointed. The wind slapped and tugged at him angrily, hauling him first one way and then the other, and the frozen gravel of the roadbed ground under his shoes.

He kept his head down and continued walking until he tripped over a switch rail. He looked up and stared into what seemed to be the mouth of an immense square cave. He headed for it, kicking through the drifts in front, and then suddenly he was inside and out of the reach of the wind and the persistent, swirling snow.

It began to make sense now. This high square cave was a wooden snow-shed built to keep the drifts off the spur track on which he was standing. If the rest of the conductor's shouted information could be relied on, the station was a quarter mile further along the spur track.

Doan nodded once to himself, satisfied, took a new grip on the handles of his bag and started trudging along the track. It had been dark outside, but the darkness inside the shed was black swimming ink with no slightest glimmer to relieve it. It was a darkness that enclosed Doan like an envelope and seemed to travel along ahead of him, piling up thicker and thicker with each step he took.

He lost his sense of direction, tripped over the rails and banged against the side of the shed, starting up echoes that clattered deafeningly.

Swearing to himself in a whisper, Doan put his bag down on the ground and fumbled around in his pockets until he found a match. He snapped it alight on his thumbnail and held it up in front of him, cupping his hands protectively around the wavering yellow of the flame.

There was a man standing not a yard away from him—standing stiff and rigid against the rough boards of the shed wall, one arm out-thrust awkwardly as though he were mutely offering to shake hands. His eyes reflected the match flame glassily.

"Uh!" said Doan, startled.

The man didn't say anything, didn't move. He was a short, thick man, and his face looked roughened and bluish in the dim light.

"Well... hello," Doan said uncertainly. He felt a queer chill horror.

The man stayed there, unmoving, his right hand outthrust. Very slowly Doan reached out and touched the hand. It was ice-cold, and the fingers were as rigid as steel hooks.

Doan went backward one stumbling step and then another while the shadows jiggled weirdly around him. Then the match burned his fingers and he dropped it, and the darkness slapped down like a giant soft hand. It was then that he heard a noise behind him—a stealthy skitter in the gravel, faint through the swish of the snow against the shed walls.

Doan turned his head a little at a time until he could see over his shoulder. He stood there rigid while the darkness seemed to pulsate with the beat of his heart.

There were eyes watching him. Luminous and yellow and close to the ground, slanted obliquely at their corners. There were three pairs of them.

Doan stood there until the breath ached in his throat. The paired eyes didn't move. Doan exhaled very slowly and softly. He slid his hand inside the bulk of his topcoat, under his suit coat, and closed his fingers on the butt of the Police Positive.

Just as slowly he drew the revolver from under his coat. The hammer made a small cold click. Doan fired straight up in the air.

The report raised a deafening thunder of echoes. The eyes blinked and were gone, and a voice bellowed hollowly at Doan out of the blackness:

"Don't you shoot them dogs! Damn you, don't you shoot them dogs!"

The voice came from somewhere in back of where the yellow eyes had been. Doan dropped on one knee, leveling the revolver in that direction.

"Show a light," he ordered. "Right now."

Light splayed out from an electric lantern and revealed long legs in baggy blue denim pants and high snow-smeared boots with bulging rawhide laces. The yellow eyes were back of the legs, just out of the throw of light from the lantern, staring in savage watchfulness.

"Higher," said Doan. "Higher with the lantern."

The light went up by jerks like a sticky curtain on a stage, showing in turn a clumsy-looking sheepskin coat, a red hatchet- like face with fiercely glaring eyes, and a stained duck-hunter's cap with the ear flaps pulled down. The man stood as tall and stiff as some weird statue with his shadow stretched jagged and menacing beside him.

The dogs yelped. The dead man pointed a stiff finger in the lantern glow.

"I'm the station master. This here's company property. What you doin' on it?"

"Trying to get off it," said Doan.

"Where'd you come from?"

"The train, stupid. You think I'm a parachute trooper?"

"Oh," said the tall man. "Oh. Was you a passenger?"

"Well, certainly."

"Oh. I thought you were a bum or something. Nobody ever comes up here this time of year."

"I'll remember that. Come closer with the light. Keep the dogs back."

The tall man came slowly closer. Doan saw now that he had only one arm—the left—the one that was holding the lantern. His right sleeve was empty.

"Who's our friend here?" Doan asked, indicating the stiff frozen figure against the wall.

The tall man said casually: "Him? Oh, that's Boley, the regular station master. I'm his relief."

"He looks a little on the dead side to me."

The tall man had a lean gash of a mouth, and the thin lips moved now to show jagged yellow teeth. "Dead as a smoked herring."

"What happened to him?"

"Got drunk and lay out in the snow all night and froze stiff as a board."

"Planning on just leaving him here permanently?"

"I can't move him alone, mister." The tall man indicated his empty right sleeve with a jerk of his head. "I told 'em to stop and pick him up tonight, but they musta forgot to do it. I'll call 'em again. It ain't gonna hurt him to stay here. He won't spoil in this weather."

"That's a comforting thought."

"Dead ones don't hurt nobody, mister. I've piled 'em on trench parapets and shot over 'em. They're as good as sandbags for stoppin' bullets."

"That's a nice thought too. Where's this station you're master of?"

"Right ahead a piece."

"Start heading for it. Keep the dogs away. I don't like the way they look at me."

The light lowered. The tall man sidled past Doan, and his thin legs moved shadowy and stick-like in the lantern gleam, going away.

Doan followed cautiously, carrying the grip in one hand and the cocked revolver in the other. He looked back every third step, but the yellow eyes were gone now.

The shed ended abruptly, and the station was around the curve from it, a yellow box-like structure squashed in against the bare rock of the canyon face with light coming very dimly through small, snow-smeared windows.

The tall man opened the door, and Doan followed him into a small square room lighted with one unshaded bulb hanging behind the shining grillwork of the oval ticket window. Yellow varnished benches ran along two walls, and a stove gleamed dully red in the corner between them.

Doan kicked the door shut behind him and dropped his grip on the floor. He still held his revolver casually in his right hand.

"What's your name?" he asked.

"Jannen," said the tall man. He had taken off his duck- hunter's cap. He was bald, and his head was long and queerly narrow. He stood still, watching Doan, his eyes gleaming with slyly malevolent humor. "You come up here for somethin' special? There ain't no place to stay. There's a couple of hotels down- canyon, but they ain't open except for the snow sports."

Doan jerked his head to indicate the storm outside. "Isn't that snow?"

"This here is just an early storm. It'll melt off mostly on the flats. In the winter season she gets eight-ten feet deep here on the level, and they bring excursion trains up—sometimes four-five hundred people to once—and park 'em on the sidings over weekends."

There was a whine and then a scratching sound on the door behind Doan.

The tall man jerked his head. "Can I let my dogs inside, mister?"

Doan moved over and sat down on the bench. "Go ahead."

Jannen opened the door, and three shadowy gray forms slunk through it. They were enormous beasts, thick-furred, with blunt wedge-shaped heads. They circled the room and sat down in a silent motionless row against the far wall, watching Doan unblinkingly with eyes that were like yellow, cruel jewels.

"Nice friendly pets," Doan observed.

"Them's sled dogs, mister."

"What dogs?" Doan asked.

"Sled dogs—huskies. See, sometimes them tourists that come up here, they get tired of skiin' and snow-shoein' and then I pick me up a little side money haulin' 'em around on a dog sled with the dogs. Lot of 'em ain't never rid behind dogs before, and they get a big kick out of it. Them are good dogs, mister."

"You can have them. Do you know where the Alden lodge is from here?"

Jannen's lips moved back from the jagged teeth. "You a friend of that girl's?" His voice was low and tight.

"Not yet. Are you?"

Jannen's eyes were gleaming, reddish slits. "Oh, yeah. Oh, sure I am. I got a good reason to be." With his left hand he reached over and tapped his empty right sleeve. "That's a present from her old man."

Doan was watching him speculatively. "So? How did it happen?"

"Grenade. I was fightin' over in China. It blew up in my hand. Tore my arm off. Old man Alden's factory sold the Chinks that grenade. It had a defective fuse."

"That's not the girl's fault."

Jannen's lips curled. "Oh, sure not. Nobody's fault. An accident. Didn't amount to nothin'—just a man's right arm tore off, that's all. Just made me a cripple and stuck me up in this hell-hole at this lousy job. Yeah. I love that Alden girl. Every time I hear that name I laugh fit to bust with joy."

His voice cracked, and his face twisted into a fiendish grimace. The dogs stirred against the wall uneasily, and one of them whimpered a little.

"Yeah," Jannen said hoarsely. "Sure. I like her. Her old man skimped on that grenade job, and skimped on it so he could leave that girl another million. You'd like her too, mister, if an Alden grenade blew your right arm off, wouldn't you? You'd like her every time you fumbled around one-handed like a crippled bug, wouldn't you?

"You'd like her every time the pain started to bite in that arm stump so you couldn't sleep at night, wouldn't you? You'd feel real kind toward her while you was sleepin' in flop-houses and she was spendin' the blood money her old man left her, wouldn't you, mister?"

The man was not sane. He stood there swaying, and then he laughed a little in a choking rasp that shook his thin body.

"You want me to show you the way to the lodge? Sure, mister. Glad to. Glad to do a favor for an Alden any old time."

Doan stood up. "Let's start," he said soberly.

DOAN smelled the smoke first, coming thin and pungent down-wind, and then Jannen stopped short in front of him and said:

"There it is."

The wind whipped the snow away for a second, and Doan saw the house at the mouth of a ravine that widened out into a flat below them. The walls were black against the white drifts, and the windows stared with dull yellow eyes.

"Thanks," said Doan. "I can make it from here. If I could offer some slight compensation for your time and trouble..."

Jannen was hunched up against the wind like some gaunt beast of prey, staring down at the house, wrapped up in darkly bitter thoughts of his own. His voice came thickly.

"I don't want none of your money."

"So long," said Doan.

"Eh?" said Jannen, looking around.

Doan pointed back the way they had come. "Goodbye, now."

Jannen turned clumsily. "Oh, I'm goin'. But I ain't forgettin' nothin', mister." His mittened left hand touched his empty right sleeve. "Nothin' at all. You tell her that for me."

"I'll try to remember," said Doan.

He stood with his head tilted against the wind, watching Jannen until he disappeared back along the trail, his three huskies slinking along like stunted shadows at his heels. Then he shrugged uneasily and went down the steep slant of the ridge to the flat below. The wind had blown the snow clear of the ground in places, and he followed the faint marks of a path across the stretch of frozen rocky ground.

Close to it, the house looked larger—dark and ugly with the smoke from the chimney drifting in a jaunty plume across the white-plastered roof. The path ended at a small half-enclosed porch, and Doan climbed the log steps up to it and banged hard with his fist against the heavy door.

He waited, shivering. The cold had gotten through his light clothes. His feet tingled numbly, and the skin on his face felt drawn and stiff.

The door swung open, and a man stared out at him unbelievingly. "What—who're you? Where'd you come from?"

"Doan—Severn Agency."

"The detective! But man alive! Come in, come in!"

Doan stepped into a narrow shadowed hall, and the warmth swept over him like a soft grateful wave.

"Good Lord!" said the other man. "I didn't expect you'd come tonight—in this storm!"

"That's Severn service," Doan told him. "When duty calls, we answer. And besides, I'm overdrawn on my salary."

"But you're not dressed for—Why, you must be frozen stiff!"

He was a tall man, very thin, with a sharp dramatically haggard face. His hair was jet-black with a peculiarly distinctive swathe of pure white running back slantwise from his high forehead. He talked in nervous spurts, and he had a way of making quick little half-gestures that had no meaning, as though he were impatiently jittery.

"A trifle rigid in spots," Doan admitted. "Have you got some concentrated heat around the premises?"

"Yes! Yes, surely! Come in here! My name is Brill, by the way. I'm in charge of Miss Alden's account with the National Trust. Taking care of the legal end. But of course you know all about that. In here."

It was a long living room with a high ceiling that matched the peak of the roof. At the far end there was an immense natural stone fireplace with the flame hooking eager little blue fingers around the log that almost filled it.

"But you should have telephoned from the station," Brill was saying. "No need to come out tonight in this."

"Have you a telephone here?" Doan asked.

"Certainly, certainly. Telephone, electricity, central heating, all that... . Miss Alden, this is Mr. Doan, the detective from the Severn Agency. You know, I told you—"

"Yes, of course," said Sheila Alden. She was sitting on the long, low divan in front of the fire. She was a small, thin girl with prim features, and she looked disapprovingly at Doan and then down at the snow he had tracked across the floor. She had lusterless stringy brown hair and teeth that protruded a little bit, and she wore thick horn-rimmed glasses.

"Hello," said Doan. He didn't think he was going to like her very well.

"This seems all very melodramatic and very unnecessary," said Sheila Alden. "A detective to guard me! It's so absurd."

"Now, not at all, not at all," said Brill in a harassed tone. "It's the thing to do—the only thing. I'm responsible, you know. The National people hold me directly responsible for your well-being. We must take every reasonable precaution. We really must. I'm doing the best I know how."

"I know," said Sheila Alden, faintly contemptuous. "Pull up that chair, Mr. Doan, and get close to the fire. By the way, this is Mr. Crowley."

"Hello, there," said Crowley cheerfully. "You're hardly dressed for the weather, old chap. If you plan to stay around here I'll have to lend you some of my togs."

"Mr. Crowley," said Brill, "has a place over at the other side of Flint Flat."

"A little hide-out, you know," said Crowley. "Just a little shack where a man can hole in and soak up some solitude now and then."

He had a very British-British accent and a hairline black mustache and a smile full of white teeth. He was every bit as handsome as those incredible young men who are always driving the latest sport motor cars in magazine advertisements. He knew it. He had brown eyes with a personality twinkle in them and wavy black hair and an expensive tan.

"Mr. Crowley," said Brill, "got lost in the storm this afternoon and just happened—just happened to stumble in here this afternoon."

"Right-o," said Crowley. "Lucky for me, eh?"

"Very," said Brill sourly.

Crowley was sitting on the divan beside Sheila Alden, and he turned around and gave her the full benefit of his smile. "Yes, indeed! My lucky day!"

Sheila Alden simpered. There was no other word for it. She wiggled on the cushions and poked at her stringy hair and blinked shyly at Crowley through the thick glasses.

"You must stay the night here, Mr. Crowley."

"Must he?" Brill inquired, still more sourly.

Sheila Alden looked up, instantly antagonistic. "Of course! He can't possibly get home tonight, and we have plenty of room, and I've invited him!"

"A little blow like this," said Crowley. "Nothing. Nothing at all. You should see it scream up in the Himalayas. That's something!" He leaned closer to Sheila. "But of course there's no chance to stumble on to such delightful company when you're in the Himalayas, is there? I'll be delighted to stay overnight, Miss Alden, if it won't inconvenience you too much. It's so kind of you to ask me."

"Not at all," said Sheila Alden.

Doan was standing in front of the fire with his arms out- spread, gradually thawing out, and now someone tugged uncertainly at his sleeve.

"You're—the detective?"

Doan turned to look at another girl. She was small too, smaller even than Sheila Alden, and she had a soft round face and full lips that pouted a little. She had blond hair, and her eyes were very wide and very blue and they didn't quite focus.

"This is Miss Alden's secretary," Brill said stiffly. "Miss Joan Greg."

"You're cute," Joan Greg said, swaying just slightly. "You're a cute little detective."

"Cute as a bug's ear," Doan agreed.

"Joan!" Sheila Alden said sharply. "Please behave yourself!"

Joan Greg turned slowly, still keeping her hold on Doan's arm. "Talking—to me?"

"You're drunk!" Sheila Alden said.

Joan Greg made the words carefully with her soft lips. "Shall I tell you just what you are—you and that thing sitting beside you?"

The tension in the room was like a wire stretched to a breaking point, with them all standing and staring at Joan incredulously. She was swaying, and her lips were twisting to form new words, while her eyes stared at Sheila Alden with glassy, unblinking hate.

"I'll—kill—her," said Joan Greg distinctly.

"MISS GREG!" Brill gasped, horrified. But he did not make a move. He just stood, gaping.

"Wait until I get warm first, will you?" Doan asked casually.

Joan Greg forgot all about Sheila Alden for the moment. She swayed against Doan and said: "You're just the cutest little fella I've ever seen. Lemme help you out of your coat."

Brill stepped forward. "I'll do—"

"No! No! Lemme!"

Fumblingly, she helped Doan take off his topcoat and staggered back several steps holding it in front of her.

"Gonna—hang it up. Gonna hang the nice cute little detective's coat up for him."

She went at a diagonal across the room, missed the door by ten feet, carefully walked backward until she got a new line on it, and made it through. They could hear her in the hall, stumbling a little.

"I could use some of that," Doan said.

Brill stared at him. "Eh?"

Doan made a motion as though he were lifting a glass.

"Oh!" Brill said. "A drink! Yes, yes. Of course. Kokomo! Kokomo!"

A swinging door squeaked, and light showed through the archway opposite the entrance to the hall. Feet scraped lumberingly on the floor, and a man came in through the archway and said in a surly voice:

"Well, what?"

He had shoulders as wide as a door and long thick arms that were corded with muscle. He was wearing a white apron over blue denim trousers and a checked shirt, and he had a tall chefs hat perched jauntily over the bulging shapeless lump that had once been his left ear. He carried a toothpick in one corner of his pulpy lips, and his eyes were dully expressionless under thick, scarred eyebrows.

"Ah, yes," Brill said nervously. "Bring the whisky, Kokomo, and—and a siphon of soda."

"You want ice?"

"I've had mine tonight already," Doan said.

"No," Brill said. "No ice."

Kokomo lumbered back through the archway and appeared immediately again carrying a decanter and a siphon on a tray with a stacked pile of glasses.

Brill took the tray. "Mr. Doan, this is Kokomo—the cook and caretaker. This is the detective, Kokomo."

"This little squirt?" said Kokomo. "A detective? Hah!"

Brill said: "Kokomo! That's all!"

"Hah!" said Kokomo, staring down at Doan. He moved his big shoulders in a casual shrug and padded back through the archway. The swinging door squeaked shut behind him.

"Really, Mr. Brill," Sheila Alden said severely. "It seems to me that I have grounds for complaint about your choice of employees."

Brill threw his hands wide helplessly. "Miss Alden, I've told you again and again that our Mr. Dibben had been handling all your affairs and that he was injured when an auto ran over him and that his duties were suddenly delegated to me without the slightest warning and that he hadn't made any note of the fact that you intended to come up here.

"When you called me I had to find a man at once who would act as caretaker and cook and open this place up for you. This man Kokomo had excellent references—a great deal of experience—all that. You must admit, Miss Alden, that in spite of his uncouth appearance, he is a very good cook, and it's very difficult to get servants to come clear up here..."

Sheila Alden wasn't through. "And I don't think much of your choice of a secretary, either."

Brill lifted his hands. "Miss Greg had the very finest references. There was nothing in them whatsoever that indicated she was—ah—inclined to drink too much."

"Lonely country," Crowley said. "Brings it on. Seen it happen to a lot of chaps in Upper Burma. Probably be all right as soon as she gets back to civilization, eh? By the way, Mr. Doan, how on earth did you find this place? I mean, I got jolly well lost myself, and I can't see how a stranger could find his way here."

Doan had filled a glass half with whisky and half with soda and was sipping at it appreciatively. "The station master brought me around—not because he wanted to. He seemed a bit sour on the Alden name."

"And that's another thing!" Brill said worriedly. "The man's a crank—dangerous. He shouldn't be allowed at large. He holds some insane grudge against Miss Alden, and he might—might... I mean, I'm responsible. I tried to talk to him, but all he did was threaten me. And those damned dogs. Mr. Doan, you had better investigate him thoroughly."

"Oh, sure," said Doan.

Brill ran thin nervous fingers through his hair, mussing up the blazed streak of white that centered it. "I don't like you coming up here in this wilderness, Miss Alden. It's a great responsibility to put on my shoulders." He fumbled in his coat pocket and brought out a shiny metal case.

Doan stiffened, his glass half-raised to his lips. "What's that you've got there?"

"This?" said Brill. "A cigar case."

The case was an exact duplicate of the one Doan had found in his pocket—his deadly present from the mysterious Mr. Smith.

Brill snapped the catch with his thumb, and the case opened on his palm, revealing the six cigars fitted into it snugly.

Doan released his breath in a long sigh. "Where," he said, clearing his throat. "Where did you get it?"

Brill was admiring the case. "Nice, isn't it? Just the right size. Eh? Oh, it was a present from a client."

"What was his name?"

"Smith," said Brill. "As a matter of fact, that's a strange thing. We have several clients whose name is Smith, and I don't know which one of them gave me this. Whoever it was just left it on my secretary's desk with a little note saying in appreciation of services rendered and all that and signed, 'Smith'—"

"What was in it?" Doan asked.

Brill looked surprise. "Why, cigars."

"Did you smoke them?"

"Well, no. You see, I smoke a specially mild brand on account of my throat. I gave the ones in the case to the janitor, poor chap."

"Poor chap?" Doan repeated.

"Yes. He was killed that very night. He had a shack on the outskirts of the city, and he was running a still of some sort there—at least that's what the police think—and the thing blew up and blasted him to bits. Terrific explosion."

"Oh," said Doan. He watched thoughtfully while Brill selected a cigar and put the case back in his coat pocket.

"Well," said Brill, making an effort to be more sociable. "Let's think of something pleasant..." His voice trailed off into a startled gulp.

Joan Greg had come quietly in from the hall. She was holding Doan's revolver carefully in her right hand. She was walking straighter now, and she came directly across the floor to the front of the divan. She stopped there and pointed the revolver at Sheila Alden.

"Here!" Crowley shouted in alarm.

Doan flipped the contents of his glass into Joan Greg's face. Her head jerked back when the stinging liquid hit her. She took one uncertain step backward, and then Doan vaulted over the couch and expertly kicked her feet from under her.

She fell on her back, coming down so hard that her blond head bounced forward loosely with the impact. Doan stepped on her right wrist and twisted the revolver from her lax fingers.

Joan Greg turned over on her stomach and hid her face in her arms. She began to cry in racked, gasping sobs. The others stared at her, and at Doan with a sort of frozen, dazed horror.

"More fun," said Doan, slipping the revolver into his waistband. "Does she do things like this very often?"

"Gah!" Brill gasped. "She—she would have... Why—why, she's crazy! Crazy drunk! Where—where'd she get that gun?"

"It was in my topcoat pocket," Doan said. "Careless of me, but I didn't think there were any homicidal maniacs wandering around the house."

Sheila Alden's face was paper white. "Get her out of here! She's fired! Take her away!"

"Yes, yes," said Brill. "At once. Terrible. Terrible thing, really. And I'll be blamed—"

"Take her away!" Shield Alden screamed at him.

Doan leaned over and picked Joan Greg up. She had stopped crying and she was utterly relaxed. Her arms flopped laxly. Her eyes were closed, and the tears had made wet jagged streaks down her soft cheeks.

"She's passed out, I think," Doan said. "I'll take her up and lock her in her bedroom."

"Yes, yes," Brill said. "Only thing. This way."

Crowley was bending anxiously over Sheila Alden. "Now, now. It's all over. Gives a person a nasty feeling, I know. Saw a chap run amok in Malay once. Ghastly thing. But you're a brave girl. Just a little sip of this."

Brill led the way across the living room and down the hall to a steep stairway with a rustic natural-wood railing. Brill went on up it and stopped at the first door in the upper hallway. He was still shaky, and he edged away from the limp form of Joan Greg as a man would avoid contact with something poisonous.

"Here," he said, pushing the door open and reaching around to snap on the light. "This—this is awful. Miss Alden is sure to complain to the office. What do you suppose ailed her?"

Doan put Joan Greg down on the narrow bed under the windows. The room was stiflingly hot. He looked at the windows and then down at Joan Greg's flushed face and decided against opening one. While he was looking down at her, she opened her eyes and stared up at him. All the life had drained out of her round face and left it empty and bitter and disillusioned.

"What's the trouble?" Doan asked. "Want to tell me about it?"

She turned her head slowly away from him and closed her eyes again. Doan waited a moment and then said:

"Better get undressed and into bed and sleep it off."

He turned off the light and went out of the room, transferring the key from the inside of the lock to the outside and turning it carefully. He tried the door to make sure and then put the key in his pocket.

Brill was wringing his hands in a distracted way. "I—I can hardly bear to face Miss Alden. She will blame me. Everybody blames me! I didn't want this responsibility... . I've got to go down and out-wait that scoundrel Crowley."

"Why?" Doan asked.

Brill came closer. "He's a fortune hunter! He didn't get lost today! He came over here on purpose because he's heard that Miss Alden was here! She's an impressionable girl, and I can't let him stay alone with her down there. The office would hold me accountable if he—if she..."

"I get it," Doan said.

"I don't know what to do," said Brill. "I mean, I know Miss Alden will be sure to resent—But I can't let him—"

"That's your problem," said Doan. "But I'm not supposed to protect her from people who want to make love to her—only the ones that don't. So I'm not out-waiting our friend Crowley. I'm tired. Which is my bedroom?"

"Right there. You'll leave your door open, Mr. Doan, in case—in case..."

"In case," Doan agreed. "Just whistle, and I'll pop up like any jack-in-the-box."

"I'm so worried," said Brill. "But I must go down and see that the scoundrel doesn't..."

He went trotting down the steep stairs. Doan went along the hall back to the bedroom Brill had indicated. It was small and as neatly arranged as a model room in a display window, furnished with imitation rustic bed, chairs and bureau.

It, too, was stiflingly hot. Doan spotted the radiator bulking in the corner. He went over and touched it experimentally and jerked his fingers away with a whispered curse. It was so hot the water in it was burbling. Doan looked for the valve to turn it off, but there was none.

He stood looking at the radiator for some time, frowning in a puzzled way. There was something wrong about the whole setup at the lodge. It was like a picture slightly out of focus, and yet he couldn't put his finger on any one thing that was wrong. It bothered Doan, and he didn't like to be bothered. But it was still there. An air of intangible menace.

He discovered now that he had left his grip downstairs. He didn't feel like going and getting it at the moment. He wanted to think about the people in the house, and he had always been able to think better lying down. He shrugged and headed for the bed. Fully dressed, he lay down on top of it and went to sleep.

WHEN Doan awoke, he awoke all at once. He was instantly alert, but he didn't make any other motion than opening his eyes. The heat in the bedroom was like a thick oppressive blanket—fantastic and unreal against the shuffling whine of the storm outside.

Doan stayed still and wondered what had awakened him. His bedroom door was still open, and there was a dim light in the hall. A timber creaked eerily somewhere in the house. The seconds ticked off slowly and leadenly, and then a shadow moved and made a rounded silhouette in the hall in front of the bedroom door.

Doan moved his hand and closed his fingers on the slick coolness of his revolver. The shadow thickened, swaying a little, and then Joan Greg came into sight. She was moving along the hall with mincing, elaborately cautious steps. She had evidently taken Doan's advice about going to bed. She was dressed in a green silk nightgown that contrasted with her blond hair. She stopped opposite Doan's doorway and looked that way.

Her soft lips were open, twisted awry, and there was a dribble of saliva on her chin. Her eyes were widened in mesmerized horror. She was holding a short broad-bladed hunting knife in her right hand.

"That's fine," said Doan quietly. "Just stand right where you are."

The knife made a ringing thud falling on the floor. Joan Greg drew a long shuddering breath that pulled the thin green silk taut across her breasts. The cords in her soft throat stood out rigidly.

Then she crumpled like a puppet that has been dropped. She was an awkwardly twisted heap of green silk and white flesh, with the gold of her hair glinting metallically in the light.

Doan swung cat-like off the bed and reached the doorway in two long steps. He didn't look down at Joan Greg, but both ways along the hall. One of the doors on the opposite side moved just a trifle.

"Come out of there," said Doan. "Quick!"

The door opened in hesitant jerks, and Crowley peered out at him. He was wearing nothing but a pair of blue shorts, and his wedge-shaped torso was oily with perspiration. His face was a queer yellowish green under its tan.

"So beastly hot. Couldn't get the windows open. I thought—I heard—"

"Come here."

Crowley moistened his lips with a nervous flick of his tongue. He came forward one step at a time. "What—what's the matter with her?"

"Stand right there and stand still."

Crowley's breath whistled between his teeth. "Blood! Look! All over her hands—"

Doan knelt down beside Joan Greg. Her hands were spread out awkwardly beside her, as though she had tried to hold them away from herself even while she fell. There was blood smeared on her fingers and streaked gruesomely across both her soft palms. Doan poked at the knife she had dropped with the barrel of his revolver.

There was blood clotted on them, too. On the handle and on the broad blade. Doan raised his head.

"Brill!" he called sharply.

Bed springs creaked somewhere, and Brill's nervous voice said: "Eh? What? What?"

The springs creaked again protestingly. Brill, looking tall and lath-like in white pajamas, appeared in the open door of the bedroom next to Doan's. His slick hair was rumpled now, and he held one hand up to shield his eyes from the light.

"What? What is it?" His thin face began to lengthen, then, as though it had been drawn in some enormous vise. "Oh, my God," he said in a whisper.

He came forward with the stiff, jerky steps of a sleep-walker. "Did she commit suicide?"

"I'm afraid not," said Doan. "She's fainted. Which is Miss Alden's room?"

Brill stared at him in pure frozen horror. "You don't think she—" He made a strangled noise in his throat. He turned and ran down the hall, his white pajamas flapping grotesquely. "Miss Alden! Miss Alden!"

The door at the end of the hall was hers, and Brill pounded on the panels with both fists. "Miss Alden!" His voice was raw with panic now, and he tried the knob. The door opened immediately.

"Miss—Miss Alden," Brill said uncertainly.

"The light," said Doan, behind him.

Brill reached inside the door and snapped the switch. There was no sound for a long time, and then Brill moaned a little.

Doan said: "Come here, Crowley. I want you where I can watch you."

Crowley spoke in a jerky voice. "Well, Joan—I mean, Miss Greg. You can't leave her lying—"

"Come here."

Crowley edged inside Sheila Alden's bedroom and backed against the wall in response to a guiding flick of Doan's revolver barrel. Brill was standing in the center of the room with his hands up over his face.

"This will ruin me," he said in a sick mumble. "I was going to get a partnership in the firm. They gave me full responsibility for watching out for her. Account was worth tens of thousands a year. They'll hound me out of the state—can never practice again." His voice trailed off into indistinguishable syllables.

This bedroom was as stiflingly hot as Doan's had been. Sheila Alden had only a sheet over her. She was stiffly rigid on her back in the bed. Her throat had been cut from ear to ear, and the pillows under her head were soaked and sticky with blood. Her bony face looked pinched and small and empty, with her nearsighted eyes staring glassily up at the light.

Doan pointed the gun at Crowley. "You talk."

Crowley made an effort to get back his air of British light- heartedness. "But, old chap, you can't imagine I—"

"Yes, I can," said Doan.

Crowley's mouth opened and shut soundlessly.

"It comes a little clearer," said Doan. "You were so scared you got a little rattled for a moment. Just how well do you know Joan Greg?"

Crowley's smile was an agonized grimace. "Well, my dear chap, hardly at all. I just met the young lady today."

"We can't use that one," Doan said. "You know her very well. That was what was the trouble with her. She was jealous. You've been living off her, haven't you?"

"That's not a nice thing to accuse a chap—"

"Murder's not nice, either. You've been living off Joan Greg. You haven't any more got a place on Flint Flat than I have. Have you?"

"Well..."

"No, you haven't. Joan Greg told you that she had gotten a job as secretary to Sheila Alden and was coming up here. You knew who Sheila Alden was, and you thought that was a swell chance for you to chisel in and charm the young lady with your entrancing personality.

"You must have let Joan Greg in on it—told her you'd make a killing and split with her probably. But when it came right down to seeing you make passes at Sheila Alden, Joan Greg couldn't take it."

"Fantastic," Crowley said in a stiff unnatural voice. "Utter—rot."

"You!" said Brill, and the blood made a thick red flush in his shallow cheeks. "You rat! I'll see you hung! I'll—I'll—Doan! Hold him until I get my gun!" He blundered wildly out of the room, and his feet made a wild pattering rush down the hall.

Crowley had recovered his poise now. His eyes were cold and alert and hard, watching Doan. Brill's bedroom door slammed, and then his voice shrilled out fiercely.

"Get up! Get up, damn you! I know you're faking! I saw your eyes open!"

There was a scuffling sound from the hall, and Joan Greg cried out breathlessly. Crowley moved against the wall.

"No," said Doan.

Confused footsteps came closer, and Brill pushed Joan Greg roughly into the bedroom.

"There!" Brill raged. "Look at her! Look at your handiwork, damn you, you shameless little tramp!"

Joan Greg gave a stifled cry of terror. She held her shaking, blood-smeared hands out in front of her helplessly, and then she turned and ran to Crowley and hid her face against his chest.

"There they are!" Brill shouted. He was holding a .45 Colt automatic in his hand and he waved it wildly in the air. "Look at them! A fine pair of crooks and murderers! But they'll pay! You hear me, do you? You'll pay!"

Doan was looking at the radiator in the corner. He was frowning a little bit and whistling softly and soundlessly to himself.

"Why is it so hot?" he asked.

"Eh?" Brill said. "What?"

"Why is it so hot in the bedrooms?"

"The windows have storm shutters on them," Brill said impatiently. "They can't be opened in a wind like this."

"But why are the radiators so hot? The water in that one is boiling. You can hear it."

"What damned nonsense!" Brill yelled. "Are you going to stand there and ask silly questions about radiators when Sheila Alden has been murdered and these two stand here caught in the very act—"

"No," said Doan. "I'm going to find out about the matter of the temperature around here. You watch these two."

"Doan, you fool!" Brill shouted. "Come back here! You're in my employ and I demand—"

"Watch them," said Doan. "I'll be back in a minute or so."

HE went down the hall, down the steep stairs, and across the living room. The log fireplace was dull, glowing red embers now. The wind had blown some of the smoke back down the chimney, and it made a thick murky blue haze. Doan went on across the room through the archway on the other side.

Ahead of him light showed dimly around the edge of the swinging door that led into the kitchen. The hinges squeaked as Doan pushed it back.

Kokomo was sitting in the corner beside the gleaming white and chromium of an electric range. He was still wearing his big apron, and the tall chefs hat was tilted down rakishly over his left eye. He had what looked like the same toothpick in one corner of his mouth, and it moved up and down jerkily as he said:

"What can I do for you, sonny?"

"Don't you ever go to bed at night?" Doan asked.

"Naw. I'm an owl."

"It's awfully hot upstairs," said Doan.

"Too bad."

"I notice you have a central hot water heating system here. What does the furnace burn—coal or oil?"

"Coal."

"Who takes care of it?"

"Me."

"Where is it?"

Kokomo jerked a thick thumb at a door in the back wall of the kitchen. "Down cellar."

"I think I'll take a look at it."

Kokomo took the toothpick out of his mouth and snapped it into the far corner of the room. "Run along and roll your hoop, sonny, before I lose my patience and lay you out like a rug. This here end of the premises is my bailiwick and I don't go for any mush- faced snoopers prowlin' around in it. I told the rest that. Now I'm tellin' it to you."

"On the other hand," said Doan cheerfully, "I think I'll have a look at the furnace."

Kokomo got up out of his chair. "Sonny, you're gettin' me irritated. Put that popgun away before I shove it down you throat."

Doan dropped the gun in his coat pocket, smiling. "Aw, you wouldn't do a mean thing like that, would you?"

Kokomo came for him with quick little shuffling steps, his head lowered and tucked between the hunched bulk of his thick shoulders.

Doan was still smiling. He made a fork out of the first two fingers of his left hand and poked them at Kokomo's eyes. Kokomo knew that trick and, instead of ducking, he merely tilted his head back and let Doan's stiffened fingers slide off his low forehead. But when he put his head back, he exposed his thickly muscular throat.

Doan hit him squarely on the adam's apple with a short right jab. It was a wickedly effective blow, and Kokomo made a queer strangling noise and grasped his throat with both hands, rolling his head back and forth in agony. His mouth was wide open, and his eyes bulged horribly.

Doan hit him again, a full roundhouse swing with all his compact weight behind it. His fist smacked on the hinge of Kokomo's jaw. Kokomo went back one step and then another, shaking his head helplessly, still trying to draw a breath.

"I should break my hands on you, cement-head," Doan said casually. He took the revolver out of his coat pocket and slammed Kokomo on the top of the head with the butt of it.

The blow smashed the tall chefs hat into a weirdly lopsided pancake. Kokomo dropped to his knees, sagging loosely. With cold- blooded efficiency Doan hit him again in the same place. Kokomo flopped forward on his face and lay there on the shiny linoleum without moving.

It had happened very fast, and Doan was standing there now, looking down at Kokomo, still smiling in his casually amused way. He wasn't even breathing hard.

"These tough guys," he said, shrugging.

He dropped the revolver in his coat pocket again and stepped over Kokomo. The cellar door was fastened with a patent bolt. Doan unlatched it and peered down a flight of steep wooden stairs that were lighted dimly from the kitchen behind him. He felt around the door and found a light switch and clicked it. Nothing happened. The light down in the cellar, if there was one, didn't work.

Doan went down the steps, feeling his way cautiously as he got beyond the path of the light from the kitchen door. The cellar was a warm, dark cavern thick with the smell of coal dust. Feeling overhead, Doan located the warmth of a fat asbestos- wrapped pipe and judged from the direction it ran that the furnace was over in the far corner.

He started that way, sliding his feet cautiously along the cement floor. He was somewhere in the middle of it, out of reach of either wall, when something made a quick silent breath going past in front of his face.

He stopped with a jerk, reaching for his revolver. The thing that had gone past his face hit the wall behind him with a dull ominous thud and dropped to the floor. Doan stayed rigidly still, his revolver poised. He was afraid to move for fear of stumbling over something. He listened tensely, his head tilted.

A voice whispered out of the darkness ahead of him. "Don't—don't you dare come any closer. I've got a shovel here. I'll—hit you with it."

Doan was a hard man to surprise, but he was as startled now as he ever had been in his life. He stared in the direction of the voice, his mouth open.

The voice said shakily: "You get out."

"Whoa," Doan said. "Wait a minute. I'm not coming any closer. Just listen to me before you heave any more of that coal."

"Who—who are you?"

"Name's Doan."

"The detective! Oh!"

"That's what I say. And who're you?"

"Sheila Alden."

"Ah," said Doan blankly. He drew a deep breath. "Well, I know I'm not drunk, so this must be happening. If you're Sheila Alden down here in the cellar, who's the Sheila Alden up in the bedroom?"

"That's my secretary, Leila Adams. She's been impersonating me."

"Oh. Sort of a game, huh?"

"No!"

"Well, I was just asking. What's the matter with the light down here?"

"I screwed the bulb out of the socket."

"Well, where is it? I'll screw it back in again. I need some light on the subject."

"Oh, no! No! Don't!"

"Why not?"

"I—I haven't any clothes on."

"You haven't any clothes on," Doan repeated. He shook his head violently. "Maybe I'm a little sleepy or something. I don't seem to be getting this. Suppose you just start and tell me all about it."

"Well, Leila and I came up here alone. Kokomo had come ahead to open up the place. Kokomo and Leila are in this together. When we got here they held me up and locked me in the cellar—in the back room beyond this one. Leila told me she was going to pretend she was me."

"Is Brill crazy? Didn't he know Leila Adams wasn't you?"

"No. Mr. Dibben in the law firm always handled all my business. I don't know Mr. Brill. He's never seen me."

"Well, well," said Doan. "Then what?"

"They just locked me in that cellar room. There's one window, and they didn't want to put bars over it, so they took all my clothes away from me. They knew I wouldn't get out the window then. If I did I'd freeze.

"It's two miles to the station and I didn't know which way. And Kokomo said if I screamed he'd..." Her voice trailed off into a little gasping sob. "He told me what he'd do."

"Yeah," said Doan. "I can imagine."

"Where is he now?"

"Kokomo? He's slightly indisposed at the moment. Go on. Tell me the rest."

"I broke a little piece of metal off the window, and I picked the lock on the door and got out here. I know how the heating system works. The valves are down here. I turned off the ones that controlled the downstairs radiators and opened the ones that control the upstairs radiators wide.

"Then I kept putting coal in the furnace with the drafts wide open. I thought if I made it hot enough in the upstairs bedrooms someone besides Kokomo would come down and look."

"Sure," said Doan. "Smart stuff. If I'd had any brains I'd have been down here hours ago. You stay right here and I'll bring you something to wear. Don't be afraid any more."

"I haven't been afraid—not very much. Only—only of Kokomo coming down here and—"

"He won't be coming down. Stay right here. I'll be right back." Doan ran back up the steps. All his cheerful casual air was gone now. His lips were thinned across his teeth, and he moved with a cat-like, lithe efficiency.

Kokomo was still lying flat on his face in the center of the kitchen floor. Doan, moving with the same quiet quickness, opened the cupboard door and located an aluminum kettle.

He filled it with water at the sink. Carrying it carefully, he walked over to Kokomo and, using the toe of one shoe, expertly flipped the big man over on his back.

He dumped the kettle of water in Kokomo's blankly upturned face. For a second there was no reaction, then Kokomo's pulpy lips moved, and he sputtered wetly. His eyes opened and he saw Doan looking thoughtfully down at him.

"Hi, Kokomo," Doan said softly. "Hi, baby."

Kokomo made noises in his throat and heaved himself up on his elbows. Doan took one short step forward and kicked him under the jaw so hard that Kokomo's whole lolling body lifted clear of the floor and rolled half under the stove. He didn't move any more.

"I'll have another present for you later," Doan said.