RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

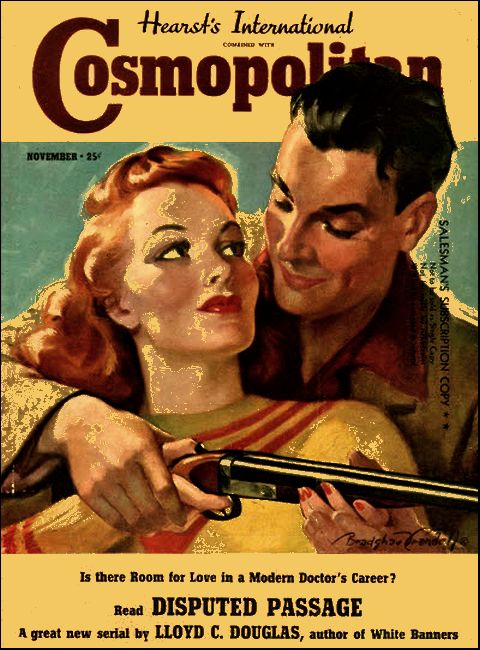

Cosmopolitan, November 1938, with "Death and Jimmy Warner"

WHEN Jimmy Warner was eighteen his father killed himself and left him with a purpose in life.

That night of the death the door of Jimmy's room was bumped open and a footstep sounded with a drag and a stagger in it. Jimmy was frightened stiff. His fingers stuttered around the button of his bedside light before he managed to turn it.

Then he saw his father coming toward him, gripping his breast and his throat. He had a desperate look in his face as though he were carrying a fragile treasure that would crash to pieces if he dropped it. When he dropped, he did not put out his hands to break the fall. By the time Jimmy had jumped out of bed, his father was dead. In the air was the unspoken name of Endicott.

It was Endicott who had really killed Jimmy's father. After fifteen years of service, the elder Warner had been put into the street by the broker, who had not paused to give a reason.

Jimmy sat on the floor cross-legged, thinking. He began to tremble with the cold but his heart was as steady as a rock. It was not passion that filled him but a calm, deliberate, full-bodied hatred. He felt also a certain grim exultation, for he knew, as he sat there, that it was his mission to kill Stephen Mann Endicott.

It was not that Jimmy loved his father; neither he nor the elder Warner was intended for love. The Warner build was lean and light, made for dodging rather than burden-bearing; the Warner face was long in the chin, thin in the mouth, bright in the eye.

Jimmy grieved not for the dead man but for the worthless, easy life in which his father had supported him; out of that regret rose the determination to kill Endicott. It would not be a mere incident in a criminal life. Out of his revenge Jimmy determined to make an entire career.

The first thing for him to do was to establish a position close to Endicott. He had an opportunity at once, for a junior member of the brokerage firm called after the funeral to see how well the elder Warner had provided for his offspring. Jimmy admitted that there was no money in the bank; he did not add that it had gone through his father's fingers to play the ponies. He merely said: "My father worked for Mr. Endicott so long that I'd like to work for him, too."

The partner asked what Jimmy could do.

"Anything. I could polish shoes, I suppose," said Jimmy. And three days later he found himself on the estate of Stephen Mann Endicott. It did not even require an interview with the great man. The estate superintendent did the talking and then put Jimmy in the stable as a groom.

The pay was small. There were three older grooms to curse him. He lived in a corner of an attic room. But nothing could break Jimmy's heart, because every day he could see the solemn face of the country mansion that housed his dead man. All the dirty jobs that were heaped on him he performed almost with enthusiasm.

In a year he was a changed fellow. Exercise straightened his shoulders and deepened his lungs. He went about with an air of authority which comes from poise and self-content. He had a purpose in life so elevated that he cared little for amusements; he worked early and late.

Such a man could not be kept in the stables. In a year Jimmy was in the house as an underbutler; and a year later he was guests' valet, learning how to press and clean, how to carry trays without jinglings of glass and silver.

The day when he entered the house was among the great events of his life. He knew that when he joined the household staff of Stephen Mann Endicott, at that very moment his master had begun to die. Enriched by that assurance, he performed his work with the patience of a horse.

As for his chief interest, he never allowed a word about Endicott to pass his lips but he listened hungrily when the others talked. In the servants' hall Gordon Thomas, the valet, was the chief critic.

"You all have cramps in your neck from looking up to him, but he's a hard man," Thomas used to say. "He's a hard man!"

But old Lindley, the head groom, once answered: "The war was hard on him, so why should he be easy on the rest of us? And what kickback do you get from the tailors every time he buys a suit of clothes? If you join the army, you have to inarch!"

In fact, though the master was harsh, it was usually in an impersonal, military way; for he had been a major in the Great War, and war methods stuck to him. When he gave commands, a battalion could have heard him.

Jimmy's days were now more filled than ever. In his effort to make himself the perfect servant, he determined to master stenography.

It was very hard. But his labor had a reward. At the close of Jimmy's third year of service, the secretary of Stephen Mann Endicott showed up with a head too much thickened by the night before. That was when Jimmy Warner stepped into the breach with his sharpened pencils and his ready pad.

"You fool! You're a valet, not a secretary!" shouted Stephen Mann Endicott.

He waved Jimmy away with such energy that the empty sleeve of his dressing gown--he had lost his left arm in the war--gestured in sympathy. But Jimmy, in the very shadow of the Wishing Gate, was not to be put off.

"I am accurate up to a hundred and fifteen words a minute," he said, "and you never go faster than a hundred."

"How the devil do you know that?" asked Endicott.

"I timed you on several occasions," said Jimmy, "when you were dictating and I brought your whisky and soda."

"The hell you did!" said Endicott. "Then take this letter to Nate Green..."

It was a critical moment. The breath of Jimmy Warner stopped in his throat but he found his pencil sweeping with flawless precision across the page.

"Now read it back to me!" roared Endicott.

Jimmy read it back. At the end, Endicott bellowed: "I didn't say: 'our misunderstanding about Central and Pacific'; I said: 'the damned double cross you put over on me in Central and Pacific.'"

"I beg your pardon, sir," said Jimmy. "I thought you had forgotten that you were writing to Mr. Nathaniel Green."

Endicott scowled upon him. Then he pressed the bell. It was plain to Jimmy that the crisis of his career had come when old Gordon Thomas eased into the room.

Endicott roared: "Find that drunken fool of a McIntyre and tell him he's fired. I've found a better secretary right here. And fire yourself at the same time. This lad can take over both jobs. And what in hell do you mean by turning pale? You've got your pension, haven't you?"

Gordon Thomas bowed. Straightening, he turned a deadly eye upon Jimmy Warner, but Jimmy endured the glance. The roughness of the master was plain enough but it was equally plain that justice had been done. Gordon Thomas carried himself out of the room and Jimmy Warner became domestic secretary and valet of the great man.

From that time forward he had chances every week to accomplish his purpose but he refused to take them. It was by no means enough that he should remove Stephen Mann Endicott from the world; it was equally necessary that he should never have suspicion touch him. He had built up a perfect record of devotion to the house of Endicott: now he needed a record of perfect devotion to Endicott in person, that in the end he might perform the perfect crime.

For two more years he labored incessantly. It was mental rather than physical labor most of the time, for he had become a great man in the household and underlings executed his pleasure in the pressing of clothes and the cleaning. Only when he accompanied Endicott on trips were all duties performed by his hands, and on these occasions he strained himself to the highest pitch, until he once heard Endicott say to Colonel Morrison:

"My brain's dying. That fellow Warner does all my thinking for me. One of those devoted damned fools."

If ever the police looked up the character of the private secretary and valet, how many bits of testimony would come from Colonel Morrison and others!

So, at the end of the fifth year of his service, in the twenty-third year of his age, Jimmy Warner reached the day when he was to kill Stephen Mann Endicott. There was no further reason to put the matter off. As a matter of fact, he had selected the little lodge in the mountains the year before as the best site for the killing. Endicott went up there to get away from the world and whatever happened would be unwitnessed.

It was a blue, bright day in late autumn, with the rocks iced in the shadows. Happy chance made Stephen Mann Endicott choose the dangerous winding path along the cliffside above Calder Creek. There was half a mile of it, with sheer rock dropping two hundred feet.

It seemed to Jimmy that this was perfect. A man cannot fall two hundred feet in an instant. There would be time for Endicott, as he hurtled down through the air, to realize that his valet's hand had cast him down. When he looked up, he would see Warner's smiling face watching from the path.

Calmly, Jimmy Warner selected the spot for the killing. It lay between two jutting points where only the hawks in the sky would see what happened.

And now Endicott was actually at the first corner. He was turning it toward his death. But just as he turned the corner Endicott's feet went out from under him on a bit of ice. He shouted as he fell.

It seemed to Jimmy Warner that a wing-stroke of darkness beat down before his face. Was it the will of God that his hand should not do murder but that nature should claim her own? Then he saw Endicott, his face already swollen and desperate with effort, hanging by his single hand from a jutting bit of rock.

"Warner!" shouted Endicott. "Come alive, you jackass! Lie down flat--grab that rock--catch me by the collar--pull!"

Jimmy lay flat; it would bring him closer to Endicott as he told him quietly the last home truths he would ever hear in this world. He secured himself by twisting his legs around a projecting rock.

"Your hand, you damned half-wit!" bellowed Endicott.

The right hand of Jimmy Warner suddenly obeyed that command. It caught Endicott's collar with a strong grip. His whole will, the entire purpose of his life, revolted against this obedience, but he found himself in the grasp of a far greater control. To disobey was as impossible as though an officer's uniform were on the back of Endicott, and Jimmy Warner were a soldier in the ranks.

Words came up in his throat and twisted his lips to a snarl, but they remained unuttered. The strain drew him far out over the lip of the rock, and now his legs were almost torn from their anchorage as Endicott, swinging his body with that one strong arm, lifted himself and cast up his leg.

The foot came down hard on the small of Jimmy's back. With that purchase, Endicott rolled himself onto the trail and lay flat on his face for a moment, gasping for breath.

Jimmy Warner came slowly to his feet. He leaned against the rock and covered his face with his hand. He could not understand. For five years he had worked with a doglike devotion; and now the opportunity was cast away!

Endicott, now on his feet, panted: "Cheer up, Warner. Well done, boy! I saw you thought I was gone. But machine guns couldn't get me; air bombs couldn't dent me; and the best a six-inch shell could do was whittle away a chunk of me. So how the devil could pitiful little Calder Creek take Steve Endicott? Come on, now give me a shoulder."

He had lamed one leg in the fall. Now he leaned on his valet and they went slowly forward, side by side. To Warner, every step they took was through a whirling mist of mental confusion. His plan had been exact; his labor had been patient; in the end chance itself had offered to complete for him the perfect crime. Yet here he found himself helping his dead man on the way home.

Most miraculous of all, he did not even feel regret.

He heard Endicott say: "The army is the only training that teaches one to know a man--as I knew you, Jimmy, the first time I laid eyes on that lean greyhound face of yours. A clean-bred one, I said to myself; a man, by heaven, if I can have the making of him... But there were times when I felt the ice in my spinal marrow and knew you were standing behind my chair...

"And back there just now, you would have done it if you could, eh? Don't answer. But see for yourself that the army way is a good way. I couldn't trust my money to your father, but I can trust my life to you!"

And the confused brain of Jimmy Warner knew that it was true. He had done his work too well. Instead of making the perfect crime, he had made the perfect servant and found his master forever. Yet it seemed to him, in a way, that they were two soldiers marching together, though he could not tell for what cause they were fighting.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.