RGL e-Book Cover 2016Š

RGL e-Book Cover 2016Š

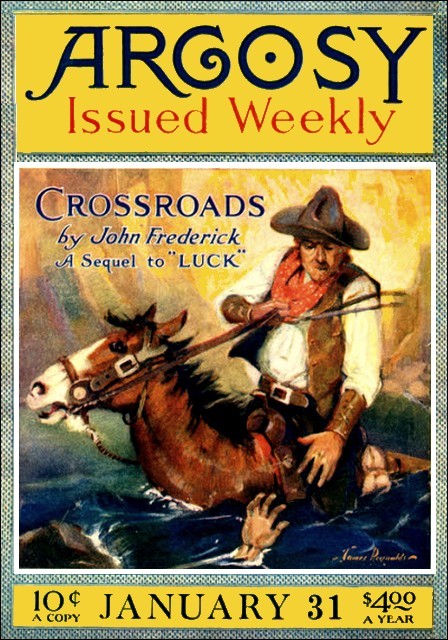

Argosy, January 31, 1920, with "Crossreads"

"HOW much hell can this fellow raise?" inquired a stranger in Guadalupe, after being regaled at some length by a tale of the manifold exploits of Dix Van Dyck.

And the answer was: "Partner, how much hell is there?"

Yet many held that there was nothing malicious about Dix Van Dyck. It was simply the spirit of what had been mischief in his boyhood. Now that he had passed the period of fisticuffs and entered that of six-guns, his pranks had serious consequences quite frequently, but his heart had not changed a whit.

Formerly, a fist fight satisfied all the yearnings of his hungry soul, but now that he stood something over six feet and weighed in the neighborhood of two hundred pounds of hard, fighting, lean-drawn muscle, an encounter with the brown fists of Dix Van Dyck was hardly preferable to a gun fight.

In another environment Dix unquestionably might have led a harmless and, in time, useful existence, but unfortunately he was born in the land of little rain and lived in a state where some eighty percent of the population is Mexican, where the laws of the legislature were printed in Spanish first and afterward in English, and where a Mexican considered himself of a strata a few degrees above that of any Anglo-American. It goes without argument that in such an environment Dix Van Dyck found a plenteous field for mischief, and he harvested his crop of deviltry with the most painful husbandry. Yet he escaped unpunished for many years. The reason was that there was in Dix Van Dyck an appealing element suggestive of the big boy run wild, and men found it hard to judge him sternly. Also it was known to all men that Dix was not the sort to hunt his six-gun by preference. He was perfectly contented to rely upon those bone-hard fists of his until the other fellow—probably from a strategic position behind a chair or from a corner of the floor—drew his gun. Then it was all over except the coroner's verdict. That verdict was usually "suicide."

Afterward there followed a period of anguish for Dix Van Dyck. For he did not like killings, and he swore off on gun play as religiously as a confirmed drunkard. But always the excitement of a prospective fight was too much for him, and the undertaker received another order. This would make it appear that Dix was a public nuisance. Yet men liked him. A man who fights squarely is judged most leniently in the Southwest. Moreover, the boyishly eager, almost wistful smile of Dix would have disarmed a heart of steel.

If he had confined his attentions to men of ill repute, all would have been well, but in an evil moment Dix crossed the path of a certain politician, one Seņor Don Porfirio Maria Oņate. In the newspapers he was known as Mr. Oņate, but in private life everyone used the title he preferred. The worthy Seņor Oņate was running for the office of sheriff of Chaparna County and approached Dix Van Dyck in a public place with a request for his vote. This was a rash step and would never have been undertaken by the noble don if he had not been too warmly inspired by tequila, that is apt to make the courage greater than the judgment.

The reply of Dix Van Dyck was of Homeric temper and volume. He stated his opinion of Seņor Don Porfirio Maria Oņate in full and completed his survey of the don's public career with some terse remarks about his ancestors. Any other man in the Southwest might have been tempted to fight, but even tequila was not as potent in the soul of Mr. Oņate as the fear of Dix Van Dyck. He stroked his mustache and smiled and hated Dix Van Dyck with his little, bright eyes, but he said nothing.

Afterward he sent his brother, accompanied by two accomplished cut-throats, to settle the long account with Dix Van Dyck. They came upon him from the rear when he was unarmed, and there followed a battle that still lives in the memory of the inhabitants of Chaparna County. Dix Van Dyck tore a shelf from the wall and with it brained two of his assailants. Then he strangled the third with his bare hands. Afterward he called upon Seņor Oņate, but that gentleman was not at home, another proof of wisdom.

Three days later Seņor Oņate was elected sheriff of Chaparna County, and Dix Van Dyck kissed his mother good bye, hugged his little brother, and departed for regions unknown to the north.

This might seem strange to some, for the last crime of Dix had been most manifest self-defense, but the dwellers in Chaparna County understood. It would have been impossible to get a jury that was not under the thumb of the new sheriff. It would have been a mockery, not a trial. So Dix Van Dyck mounted on a great horse, strong enough to bear even his weight on a day's ride, and disappeared into the hills.

He was not ill pleased by the thought of leaving Chaparna County, even under compulsion. Like the young Alexander, he was anxious for new worlds to conquer, and, once started along the outward path, he wondered why he had not made the move before. His mind was at peace; self-content warmed his blood. In the long holster his Winchester jostled softly. At either hip was the comfortable weight of a six-gun. The sweat of the tall horse was like incense in his nostrils, and the creaking of the saddle leather was sweeter than music to his ears. Behind his saddle a blanket was rolled in the slicker, and in the saddlebags he carried enough provisions for many a day.

The Arab seizes a handful of dates and another of barley and is ready for the desert. The Southwesterner travels almost as light. For guide Dix Van Dyck carried an instinct sure as that of a hunting coyote or a migratory bird. His destination was—the world.

HE did not leave Guadalupe an hour too soon, for the new sheriff was hardly in office before a warrant for Dix Van Dyck appeared. A posse strove to serve it and rode hard to the north, only to find that their bird had flown into distant regions. They returned with the ill news, and Sheriff Oņate sat down to bide his time, for he had in fact what the elephant is endowed with in fancy—a memory that never dies.

As for Dix Van Dyck, he cared not a whit what was happening behind him. He had no sooner turned his shoulder upon yesterday than it was lost and abandoned with the shades of distant years. His heart went galloping into the future. So it was in the early evening that he swung into sight of Double Bend, a group of adobe huts and frame shacks huddling away into the purples that swung down from the shadowy mountains beyond.

Double Bend took its name from the windings of Coyote Creek, which flowed through its center. The main street followed the windings of that treacherous little stream, and men held that the inhabitants of Double Bend were as snake-like as the street they walked. All of this was unknown to Dix Van Dyck, for he had long since left far behind him the regions that he knew and where he was known. All that he saw in Double Bend as he passed down its sinuous main street looked very good to him. It gave the impression of a town that has been much lived in.

The window panes, for instance, were usually shattered. The wooden Indian that the proprietor of a general merchandise store had erected before his place of business was minus one arm and his legs had almost been shot away. From a saloon of capacious proportions strains of music and the roll of voices proclaimed that "a good time was being had by all."

So Dix Van Dyck hurriedly put up his horse in the stables, ate in the restaurant a great platter of ham and eggs with an enormous side dish of French-fried potatoes, and then bore toward the saloon and dance hall. The gasoline lamp flaring over its entrance was like the vortex of a whirl pool toward which all living things from many miles around gravitated with irresistible force. Buckboards littered one side of the street and horses the other, and under the glare of the lamp a continual stream of men passed toward the dance hall. None came out. It was like the yawning maw of some great monster drawing in an endless current of human food. At the door Dix Van Dyck paused and surveyed the interior.

His eyes kindled. He was a devotee of neither whiskey nor dancing, but here was life—life in plenty, action, confusion, clamor. In such places and in such moments the tang of the world came most sharply home to him. Moreover, there was a natural caution impelling the pause at the doorway. Inside might be a dozen foes, and a foe to Dix Van Dyck would not wait to give a warning. He would either flee or else start shooting from the hip.

Big Dix slipped into the shadow on one side and turned his leonine, ugly head from side to side in a slow survey. His trained eyes photographed a hundred faces—not one was known to him. The smile that had gone out while he made this preliminary survey now returned. He canted his head to one side and drank in the confusion of sounds that swept from dancing floor, bar, and gaming tables—all in one room.

"Rolls five for his point... Come, Phoebe, talk to me, little black eyes! Rolls five... Raise that ten... Line up, gents, line up and name your poison... Hey, Bill... I seen a gent over to Tuskogee... My dance, Blondie... Red seven! Show that card! By God, I say you will... Say, boys, I'm some dry, where's the water hole, lead me to it, I can't see!"

Dix Van Dyck sauntered to the bar. On his lips the mischievous, boyish smile that all Guadalupe knew and feared was growing. In his quiet moments that eagle nose, straight, thin mouth, and forbidding eyes made him seem a man to be avoided and given ground, but his smile gave an expression of deluding gentleness to his features. Strangers, seeing him smile, were apt to invite him to a drink or ask him for a five-spot with equal readiness. But those who knew understood that smile meant a deep desire for action. It was like the grin of the pugilist who stands in his corner, rubbing his shoes in the rosin and waiting confidently for the bell.

First he examined the dancing floor, chiefly because the men were in movement there. But the monotonous whine of the violin and the regular movements of the dancers through the mist of smoke disgusted him. One of the dance-hall girls saw his smile and stopped before him expectantly. His face sobered long enough to return her glance, and she went on hastily, her query answered. Then he looked down the bar.

Whiskey itself had no charms for him, but he sometimes drank merely for excitement—a token, in Guadalupe, for men to vacate the barroom in which this grizzly happened to be quenching his thirst. The bar tonight, however, had no attraction for him. A drunken man staggered past him. He followed the uncertain progress with contempt. Next he looked to the gaming tables. They were operating under full blast, the gamesters stimulated by the dance music on one hand and the high-power whiskey on the other. Crap tables, roulette, chuck-a-luck, faro-poker—every table had a full house, and Dix Van Dyck waited for an opening.

It was during this delay that he saw her enter and turned full toward her to look again. Obviously she was not one of the hired dancing girls. Neither had she come to buy whiskey—a common occurrence. She loitered in the door carelessly, as he had done the moment before, apparently looking for a place in which she could amuse herself.

Booted, spurred, and with a regulation Forty-Five belted around her waist, her appearance was not much out of keeping with that of the average ranch girl. What distinguished her was, in the first place, an exquisitely slender, olive-skinned, dark-eyed beauty and, in the second place, an air of truly masculine detachment.

On account of her beauty Dix Van Dyck expected to see a dozen men jump up and accost her. But instead they merely turned their heads, stared at her, and then resumed their occupations. He was thoroughly puzzled. Apparently she was known. Apparently she was good. But if so, what was she doing in this hellhole?

Now it must be understood that in the Southwest there are only two classes of women. There are the bad and the good. The bad are what bad women are everywhere—very, very bad. On the other hand, the good are exceedingly good. They can travel alone anywhere, day or night, and they are perfectly safe. In a country where the need for men is great and where the place for women is small, their value is proportionately high. In that country men do not gossip about a woman, for slander meets the reply of bullets. In that country a woman can take liberties with a man that would damn her forever in the eyes of Eastern society, but in the Southwest nothing is taken for granted about the weaker sex.

Chivalry wears no plumes, and knighthood bears no title, but there gallantry is a reality and not a name. To the Southwesterner a good woman is daughter or sister or mother. She can eat his food, ride his horse, draw his revolver, and even share his bunk. Yet she will not draw a whisper of suspicion until by her own act she confesses that she is not of the elect. Such an act is the entry of a place like this one of Jerry Conklin's in the Double Bend.

All this must be understood in order to read the confusion of mind with which Dix Van Dyck stared at the feminine intruder. He read in the glances of the men that deference that is accorded to only one type of woman in the Southwest. She was known, and she was respected. Then what was she doing here? He leaned back against the bar and scowled steadily at her. Something told him that he was on the trail of excitement.

As for the girl, she swept the great room with a calm eye, almost like the glance of an ennuied man looking for excitement. At last she approached a crap table. It was surrounded by a dense circle, two deep, every man intent on his game. But at her coming one of the men glanced up, recognized her, raised his hat, and stepped back to surrender his place.

The wonder of Dix Van Dyck made his face redden furiously. As for the other men at the gaming table, they turned toward the girl with broad grins, such as those who proclaim that the luck is running against the house. Dix Van Dyck caught the man on the stick—he who handles the dice for the house—in a keen scrutiny. The fellow was scowling blackly. The girl took the dice.

Her hand dipped in a pocket of her short riding skirt and came out with the glint of yellow. She made a few casts and lost. A low groan came from the gamesters. Evidently they had wagered heavily on her luck. The girl stamped in vexation, which made Dix Van Dyck smile. At least, he thought, she was like other women in being a bad loser. She drew out another gold coin and tossed it on the table.

AFTER that, her luck apparently held consistently good. The others at the table were still wagering on her and with her, and the payer at that table did little besides constantly shovel out the coin of the house. However, the other men in the house paid little attention to the scene. In his part of the country Dix knew that such sensational winning would have drawn everyone about in a great circle to watch the big coin roll in. He gained a sudden and deep respect for a community where such prodigious luck passed with hardly a notice. It was like a crowd in a new mining town, where gold almost loses significance except when it comes raw from the earth.

At length, the girl left the table, and the payer wiped his sweaty forehead and turned a venomous glance after her retreating figure. She went straight to the roulette wheel, a small group following. Dix Van Dyck drew a little closer and saw that she had taken the most extreme chance that the game affords—she had placed a whole handful of gold on a single number.

The wheel whirled, the man behind it watching with anxious eyes. It slowed, purred, and clicked softly to a stop—and on her number. Stack after stack of coin was counted out and shoved to her—thirty-six for one. The payer watched her with a wistful eye. She placed her entire winnings again—and still on that most dubious of all gambling chances—a single number. Again the wheel whirled, purred to a stop, and again the girl won. The payer shook his head in gloomy doubt, and counted out the money slowly, stack by stack. Plainly it would not take much more to break the bank.

But, before he had half finished the count, the girl, as if impatient, picked up a handful of gold—less than her original wager—dropped it into her pocket, and said carelessly: "Keep the rest of it, Bill. I ride light. Keep the rest of it, and the next time a gent drops in here broke... and thirsty... buy him a drink and stake him."

The payer ceased in his count and stared after her with blinking, uncomprehending eyes while she strolled away to another table. Here, she lingered only a moment and then passed on to the dancing floor.

Dix Van Dyck waited for someone to follow her, someone to take the chair next to hers, but no one moved. She sat at a table alone. Men passed with smiles but without any close approach. If she had been a leper, she could not have been more sedulously avoided. Dix thought of many things: of some terrible, contagious disease, of insanity, or perhaps she was the sweetheart of some noted gunman.

Yes, that would explain it. Dix Van Dyck hitched his belt a little higher and laughed softly, unpleasantly, to himself. Most of his jests were of a nature that he alone could appreciate. He turned to a bearded, unshaven man next to him.

"Stranger," he said, "will you drink?"

"Don't mind," said the other.

"Red-eye?"

"Yep."

"Partner," continued Dix Van Dyck amiably, while the bartender was spinning the tall bottle toward them, "I been watching a little play that looks sort of queer to me. I'm a stranger in these parts, and maybe you could put me wise."

"Maybe."

"I been watching that girl over there to the table by the dancing floor."

"Jack?"

"Is that her name?"

"Yep."

"None of the boys don't seem much friendly with her. Can't she dance? Can't she talk? Or is she owned private by a gunman?"

The other grinned. "She can dance, she can talk, and there ain't any man in these parts fool enough to want to own her."

With this enigmatic reply he rested content, as if there were nothing more to be said. Dix Van Dyck blinked and drew in his breath. His very heart was eaten up with curiosity.

"Bad actor?" he asked.

"Ain't you really heard nothing about Jack?" asked the other with naīve wonder.

"Never."

"Follow me."

He led the way to the door of the saloon and squinted to right and left down the long line of tethered horses. One shape stood out through the half-broken gloom of the early night, a tall white horse, glimmering through the darkness. Even by that faint light the practiced eye of Dix Van Dyck made out an unusually beautiful piece of horse flesh.

"If you don't know the girl," said the stranger, "maybe you recognize the hoss? That white one down the line."

"Ain't nothing I can recognize him by," asserted Dix.

"Hmm," said the other, and scratched his head in the effort to find some clue that the other might be able to follow. "Ever hear of McGurk?"

"Sure," said Dix Van Dyck. "I've lived some way off from these parts, but I know McGurk is about the fastest gunman that ever fanned a hammer."

"McGurk was," answered the stranger.

"Dead?"

"Worse'n dead. Done for."

"Well?"

The other persisted in his irritating, roundabout way of telling what he knew, as if he wished to draw out the relish of a rare morsel. "Ever hear of Boone's gang?"

"Seems like I have," murmured Dix Van Dyck, "seems like I heard they was all cleaned up by McGurk."

"You heard wrong... a pile wrong," said the other. "That girl is Boone's daughter."

"The devil she is!"

"The devil she ain't. And mostly devil she is, at that. That white hoss there in the dark is McGurk's hoss."

"Is he here?"

"Nope, the girl rides the hoss."

The iron hand of Dix Van Dyck gripped the shoulder of his companion and his voice rolled, low and muttering, like approaching thunder. "Partner, I been asking you straight questions, one man to the other. Maybe I been asking too much, but in my part of the country nobody don't josh me when I feel serious. I'm a pile serious right now. Out with it. D'ye mean to tell me that girl in here finished McGurk... McGurk, who killed...?"

"I know... McGurk who killed a hundred gunfighters. But all we know is that McGurk started on the trail of Boone's gang and that he finished 'em all except one young feller who beat it East and got married and this girl. We know McGurk started on that trail with a white horse. We know the girl come down from the mountains, riding that same white horse. Partner, them are the cards, and you can put 'em together any way you want."

Dix Van Dyck swallowed hard and then set his teeth. It was almost more than he could understand. He had a faint suspicion that the other was amusing himself with generous lies. If so, there would be an unhappy ending to the tale. He decided to draw out the man further. "Is that what scares 'em away from that girl in there?"

The other looked up with a scowl that changed almost at once into friendliness.

"Look here, pal," he explained, "you're all due for a cold trail. I'll tell you straight. When Jack Boone come down from the hills, there was another with her. He was one of the last of Boone's old gang... the best of the bad lot. All we know is what he told us. He said the girl had got a hold of a little cross... this sounds funny, I know... and that the cross give her good luck, but give bad luck to everyone near her... her friends, particular. He says that cross was what made her able to beat McGurk, and, as long as she had it on, there wasn't any man could handle her."

"That sounds all pretty damned fishy to me," grumbled Dix Van Dyck.

"Don't it?" agreed the other. "It sounded fishy to the lot of us. But the first thing we noticed was that this feller wanted nothing more than to get free of Jack Boone. He blew north and ain't been heard of since. Then Bud Ganton, a dirty half-breed with a record it took half an hour to read, made up his mind that he was going to get the loot that the girl was said to have. He started out from town for her cabin where she was living up in the hills. The next day the girl come riding in to tell the deputy marshal that there was a dead man out to her house. The marshal went out and found Ganton pumped full of lead and both his own guns out with a bullet fired out of each. Now there was only one thing Ganton was any good for, and that was a gun play. With his sixes he was a world-beater. I've seen him make a play, and he could make his gun talk French, I'm here to state. Nobody knows what happened exactly out there to the girl's cabin. But it was sure plain that Ganton had time to get out his guns and make a play before he dropped. The girl was too fast for him and drilled him clean. Now, if the girl didn't have something like that cross to help her out, how'd she ever have got away with Ganton?"

"If she was Boone's daughter, he sure taught her how to fan a six," answered Dix Van Dyck.

"Sure, but that ain't all the reason we got for thinking that little cross of hers makes her safe and raises hell for her friends. There was Luther Carey. He was knocked off'n his feet by Jack's pretty face... which she's some looker... and he said bad luck could go to the devil. He started on the trail for Jack. She warned him fair and square that it was a plumb cold trail and that he'd get bad luck if he stuck around. But Luther stayed. About a week later he was bucked off a little tame cayuse that a boy could've rid. He was bucked off and busted his neck when he hit the sand. I'm asking you, was that nacheral? No, I'll tell a man it wasn't.

"Then Hopkins, that Eastern dude that was a mining engineer. He come along and seen Jack and went crazy about her. We warned him fair and square, and she warned him, too, they say. But he kept going out to see her. One day he dropped down a shaft in the Buckhorn mine, and they had to go down with a broom and a shovel and sweep up what was left of him.

"There's two things we blame to the cross Jack wears. There's plenty of others. I could sit here all night and tell 'em to you. Take her luck with cards, for instance. You never see her lose more'n one out of every three passes. If she wanted to, she could break every game in the state. But money don't seem to mean nothing to her. Hang around her? Dance with her? Partner, I'd a pile rather jump off'n Eagle Bluff. It'd be an easier way of dying, but no surer."

SO saying, the stranger turned and walked back into the bar. Even the telling of the narrative seemed to make him need a drink.

Now, it was well known in Guadalupe that, if you wanted Dix Van Dyck to do a thing, the best way was to urge him toward the opposite. If there were two roads, one safe and one dangerous, it was thoroughly understood that one could always make Dix take the safe road by urging him to choose the dangerous. If the stranger at Double Bend had been inspired by an angel from heaven, he could not have spoken more effectively to make Dix Van Dyck seek out the girl, Jack. In fact, as he stepped back into the dance hall, his mind was already made up. He only waited for a convenient moment before approaching her. But, although his nature was strangely perverse, there was little that was wholly rash about Dix Van Dyck. In the first place, he believed with his entire soul every word that the stranger had told him about Jack and her mysterious cross. He had seen the effect of that cross in her gambling. Moreover, there is a deep element of superstition in those who live among Mexicans and prospectors. Luck becomes an almost personal god.

Because Dix Van Dyck believed thoroughly that this girl held good luck for herself and bad luck for all who came near her, he was afraid—deeply afraid. He felt a prickling chill run up his back as he looked at her. But it was the sort of fear that a man feels when he looks at a grim antagonist with whom he knows that he is about to fight. It was the sort of fear that mingles with one's desire to leap from a high place to destruction. It was the imp of perverse that lives in the soul of every man, but above all was present in Dix Van Dyck.

He was afraid. He would rather have faced a dozen guns in the hands of desperadoes than sit for a single second at the side of this girl. For this very reason he would not have missed the opportunity for all the gold in the world placed at his feet. He was shaken to his very soul with fear in advancing toward a danger against which there was no known method of fighting. And because of that nothing could stop him. He hesitated only long enough to survey the girl sharply, thoroughly, weigh her strength, estimate her character.

He could see only her profile, for she leaned forward with one elbow resting on the table, and her chin in the palm of her hand; the other arm lay across the back of the chair. An attitude of awkward repose in most people, but in this girl Dix Van Dyck felt a capacity for instant action. In the fraction of a second a sleeping dog can uncurl from the most clumsy position and leap a dozen feet away from danger. He felt the same possibility in this girl—a cat-like activity—a unconscious guard that remained alert even when mind and body slept. It even occurred to him that she might be perfectly aware of his scrutiny.

Once more his flesh prickled and grew cold. So he strode boldly up and took a chair near her. Her eyes swung around to him slowly, slowly as if a careful force regulated the movement. He found himself staring into pitchy black depths, wide, unconcerned, meaningless. He felt as if the eyes were looking through him and past him at some object in the infinite distance. For a man squints to see an object near at hand but stares with open eye at something far away. Judging by her eyes, he might have been a speck of white on the far horizon, an indefinite particle, whether cloud or sail. It whipped all the fighting instinct into his brain.

"My name," he said doggedly, "is Dix Van Dyck."

Her voice, in answer, was neither frivolous nor impertinent, but rather that of one who is wearied by the necessity of speech. "My name don't concern you, stranger. If you want to know it, ask one of the men. He'll tell you, along with a lot of reasons why you shouldn't be sitting here."

"Lady," answered Dix Van Dyck, "I've heard all those reasons. To put it straight, that's why I'm here."

The first spark of interest burned up in the dark eyes, and something like the ghost of a smile softened her mouth at the corners, as if in faint recognition of a kindred spirit.

"I've heard about good luck that follows you and bad luck that follows everyone around you."

"You don't believe it?" she asked, growing somewhat cold again.

"I believe it," said Dix Van Dyck calmly, "as if I read it in the Bible, but it ain't any real reason why you should sit here alone."

"Listen," said the girl, and she leaned gravely toward him, "I got an idea that I know what you are, and I like your kind. But you're on the wrong trail... a cold trail, partner. No matter what they told you, they didn't tell you enough, or you'd have been stopped. There's bad luck around me. That ain't all. There's hell!"

Her eyes widened, and she cast a glance over her shoulder—as if fate listened there, an impalpable presence, grinning invisibly at the warning she spoke to Dix Van Dyck. She had been beautiful even when she sat there impassively, but, now that a color was flushing the olive-tinted skin and life had come into her eyes, she was the most lovely woman Dix Van Dyck had ever seen. She thrilled him like a strain of music. She uplifted him like a passage of noble poetry. She lured him like the purple distances of the desert.

"Lady," he said, "speakin' in general, the only thing I want is action, and being near you promises a pile of it. If I bother you, I'll be on my way. If I don't, I'd sure like to hang around a while."

She considered this cavalier utterance with a frown and a thoughtful, sidewise glance that suddenly lifted to his face. "If I told you to go, would you?" she asked.

Dix Van Dyck flushed. "If you say the word, there ain't nothing I'd do quicker."

"Honest?"

The blood died away from his face and left it splotched with gray, tans, and purples. "Talkin' man to man," he said evenly, "it'd be some hard job to break away just now, but I'll go, if I have to."

"Then go," said the girl sharply.

The friendliness died from her eyes, and they became in an instant as black as they had been at the first. He pushed back his chair, setting his teeth in anger. But, even as he caught the edge of the table and put weight on it to rise, he knew that he could not go. It was like a desertion before the battle was fought. It was like cowardice under fire. He settled back in the chair, breathing hard, and glared at her.

"You're saying that to try me out?" he said.

"I never meant anything more in my life," said the girl.

"Yet," he persisted, "you was pretty friendly only a minute ago."

"Was I?" she queried with calm-eyed insolence. "Well, I'm tired of you now."

He felt a great desire to take that round, slender throat between thumbs and forefingers; he could almost tell how it would crunch under the pressure. Then he remembered with a cold rush of shame that she was a woman. A woman, and therefore a creature of infinite wiles. The thought held him. He studied her.

"Well?" she asked coldly. "Are you going?"

"D'you know," pondered Dix Van Dyck, his grim eyes boring into hers, "I got an idea that, if I get up and leave this table, you'll despise me. Am I right?"

The question had the effect of a sharp jerk on the reins. The girl straightened almost with a snap and her serious frown centered steadily on him.

Before she could answer he swept on: "Look at the way I'm fixed. All my life I've been hunting action. Most I could find was hounding a few yaller-hearted men. Now I get to you. Action just nacherally follers you around. I wouldn't have to hunt for it. I find you, and you start to give me the run. I ask you, man to man... is it fair? Is it square?"

There was a movement of her lips.

He raised his right hand suddenly and pointed. "Right now, you got a smile all ready to pop out, and you're fighting to keep it back. Am I right, lady?"

She could not help it. The smile came, and then a bubbling laugh. It ran on and on through musical variations like the sound of water trickling over rocks and plunging into tinkling shallows and chiming in deep pools. In all his life Dix Van Dyck had never heard a sound that so fascinated him. He could not tell whether she was laughing with him or at him. The laughter stopped. Sitting straight in her chair, she looked at him with marvelously bright eyes, the smile coming and going at the corners of her mouth.

"DO I get you right, Dix Van Dyck?" she asked. "Am I sort of a bait that pulls trouble your way? Is that why you want to hang around with me?"

"Jack... can I call you that?"

"Sure."

"Jack, you guessed right the first time. That's why I want to hang around. Here I am, six feet two, hard as nails, handy with two guns, and nothing to do. Can you beat that?"

"Nope," said the girl, and broke into her musical chuckle again. "Nope, you beat the world, partner."

"Thanks," grinned Dix Van Dyck. "I'll just oil up my guns and get in fighting shape, and we'll make a team of it."

She grew serious again, shaking her head. "It won't do. I can't let you do it. Look here, Dix Van Dyck, I like you more 'n any man I've run into in a long time. That's telling you straight. I'm not going to let you go to hell because of a fool idea. If you want action, just shoot out these lights, and I'll guarantee you all the action you want."

"But you see," explained Dix Van Dyck sadly, "the trouble a man makes ain't half so pleasin' as the kind he just runs into sort of accidental. Understand?"

"Yep."

"How long," said Dix Van Dyck wistfully, "before things most generally starts."

"Mostly different a lot," said Jacqueline.

"In the meantime," he said, "there's considerable room on the floor. Do we dance?"

She hesitated, as if she still wished to argue the question with him, as if she fought the temptation to let him stay, but then her head nodded with the rhythm of the music—she started up, and in an instant they were gliding across the floor.

There is a strange and dangerous potency in the dance. There is no need of polished, gleaming floor, of bright lights, of a numerous and accomplished orchestra, or of a brilliant assembly of women and men. There is no need of all this. Granted an age a little under thirty, a rhythm supplied by a rusty, stringed piano, the floor of a barn or the stones of a street, and the result is the same—an intoxication, a forgetfulness of the world, two bodies moving in harmony with a thought, and that thought one of beauty. Faces tilt up—a light comes upon them—in their blood is the fragrance of spring and the richness of autumn—the pulse of life runs quicker, quicker, races—and the two strike closer to the heart of things.

So it was with Dix Van Dyck and Jacqueline. She danced rather clumsily at first, as though she had almost forgotten the steps, but, before he became conscious of disappointment, she changed and grew more warmly alive in his arms. There was a cat-like lightness in her step so that the sway of her body followed him almost as if she were poised in air and drawn hither and thither mysteriously—at his will.

As for Jack, she glimpsed the glances of envy and admiration that followed her and knew that she was dancing divinely—knew it and was grateful to the man who held her. The incense of flattery had long been absent, and now it swept up gloriously until her nostrils trembled to inhale it deeply. She had been a creature of action, of masculine and terrible action, and, as such, accepted by the men and the women among whom she moved. Now she became, in an instant, femininely appealing, beautiful. A new and mighty strength filled her.

With all her heart she hated the bearded man who tapped Dix Van Dyck on his shoulder in the middle of the dance. They had paused at the edge of the dance floor and the man said: "Stranger, be on your way. You've started your own little hell by dancing with Jack, but someone else is liable to put on the finishing touch. There was a Mexican in here a minute ago... a bad one by the look... asking after a man like you. The deputy marshal... Glasgow... was with him. I sent 'em down the street, but they'll be back. Take my advice, and don't wait."

With that, he turned on his heel, and Dix Van Dyck, a towering figure in the crowd, stiffened and stared after him. Truly the arm of Sheriff Oņate was long.

"The bad luck," he nodded and stared down at the face of the girl.

"The bad luck," she agreed. "It didn't wait." She said it half ruefully, half carelessly, like one familiar with danger. "Take the back door," she advised. "It's the easiest way out."

"The easiest way," said the big man calmly, "is to get back to our table and wait for what comes. This ain't the finish. It's only the beginning of a long trail."

She followed him back to the table. It was only because she wanted a chance to argue the point.

"But you see," she explained, as they slipped again into their chairs, Van Dyck facing the door, "that everything is against you. The deputy marshal can call on everyone in the house, if he wants 'em. Besides, do you know the country in case you make a getaway?"

"Not a mile of it. I come from the south."

"What've you done that started the law after you?"

"Nothing. We've got a badman for sheriff down in Chaparna County. He's after my scalp."

"And you're going to sit here and see this through?"

"Sure. What would you do?"

She avoided the question. "It's a crazy idea. Take my word, the best thing is to cut and run. It's bad to have a sheriff after you. It's a lot worse to have a marshal, and Glasgow sticks to a trail like glue to a dog's tail."

Apparently he barely heard her words but sat stiff and straight in his chair, his keen eyes plunging into the future. By deep and sympathetic intuition she knew all that was passing in his mind.

His reason told him in no uncertain terms to take the advice of the girl and leave the saloon. But the same perverse instinct that had first made the man hunt her out, now held him in his chair, waiting for the surely approaching danger.

She knew at once that it was useless to argue longer with him. But the suspense began to make her uncomfortable and sick inside—the qualm that comes to the soldier before the battle. What made it doubly deadly was the noise that continued unabated throughout the rest of the great room. From the gaming tables, from the bar, from the orchestra, from the dance floor and the tables around it, the same unbroken stream of chatter, cries, curses, laughter poured out at them. It was like a grim parody of the whole of life. Into this gay throng death was about to come with silent steps, stretch out his arm, and beckon his victim. Then would fall an instant of silence, a few cries of horror, but almost at once the noise would be recommenced. Conscience would be drowned in the clamor of self-conscious gaiety.

"There's going to be a gun play," said Dix Van Dyck, "and I don't want you in the danger zone. Go to another table."

She shrugged her shoulders and smiled. He got the impression, somehow, that she valued her life less than anything in the world. He knew in fact that, when a woman turns daredevil, she passes beyond the limit of any man, but he was unprepared for this contemptuous indifference. He made no further effort to persuade her. His mind was too filled with conjecture. Was it indeed true that the girl was fatal to her friends? Or was the story half lie and half rumor? Against a common danger he was willing to take his chance, but to have his hands tied and the muzzle of his gun jolted by fate in the crisis of action was too much. It was superhuman—it was ghostly and paralyzing.

All of this Jack read in his face. She saw the keen eyes sink deeper under the bush of brow, saw his cheeks contract and the lower jaw thrust out, saw his forehead turn a sickly white, glimmering with perspiration. It was not cowardice. She had seen other men in her company face danger with the same aspect. But this man was different. Fear turned him cold, but it did not make him shake. It occurred to her, vaguely, that this might be the man who could break the power of the strange charm she carried. She could not stand the suspense of his silence any longer.

"How can you tell," she said, "when the man who's after you comes in?"

"I'll wait," answered the big, white-faced man, "until he makes a dive for his gun."

"Wait for that before you draw?"

"Yes."

"Then why not order your coffin now?"

"Because I take my chance on beating him to his gun."

"Beat two of them?" she repeated incredulously.

"Don't talk," he answered sharply. "I got to sit here and do a pile of thinking."

So she lapsed into silence. The face of Van Dyck, naturally homely, now grew horrible as the nervous strain of the wait told upon him. She began to have an odd feeling that she could hear the ticking of a clock somewhere through the din. It began very softly, click-click-clicking through the room and gradually rising to a crescendo, louder and louder and louder, till she wondered that everyone in the room did not hear it. It rose louder and more rapidly until she wanted to jump up from the table with an outcry of horror. Then she discovered that the mysterious beating was the drum of her own excited heart. She dared not rise.

It was a singular duel of courage between her and the man opposite. On him the danger rested. But upon her, she felt more and more strongly, would lie the blame for his death. For she did not dream of any other outcome to the encounter. She forced herself back to calmness and considered the figure of Van Dyck carefully, critically. It was that of the natural fighter, beyond a doubt, hard, lean, marvelously suggestive of activity in spite of its size. Her eyes centered on the hands. They had never worn gloves, it seemed, for they were as brown as his cheeks. They had never performed the labors of the range, for the fingers were long, sinewy, fleshless, and, when the fist closed, the row of knuckles stood out sharply. Nervous fingers. They hovered here and there. Sometimes, falling into a detached mood, it seemed to her that the hands on the opposite edge of the table were two spiders, deadly, long-leaping, and crouching, about to lunge at some prey. Perhaps at her throat.

Fear of the man grew slowly up in her. He was in an agony of apprehension. She knew he did not really expect to outlive the coming fight. She knew he believed in the potent power of the cross she wore and its damning bad luck. There remained his will-power and his pride. It made a terrible and silent fight—a man within a man.

Then that slender, long-fingered right hand grew tense on the edge of the table. He leaned back a little in his chair so that he would have free play to get at this revolvers.

"YOU see him?" she whispered.

"Don't turn!" he warned her softly, fiercely. "I think I see the man. I think I see a Mexican I knew in Chaparna County."

"And the marshal?"

"There's no one with him... no one I can see."

"Thank God."

"Not yet. This Mex is a bad one... if he's the man I think. Pedro Alvarez... long record... snap shot."

"What's he doing?"

She yearned for a single glance back. But such a glance might have betrayed her companion to the hunter. Small things, she knew, frequently turned the odds in such battles.

"He's walkin' about... slow. He's looking hard."

"Dix Van Dyck, it ain't too late. Start for that back door before he sees you."

"You're right, Jack, I'm scared. Not of the Mex, but of that cross you wear. But I'm not too scared to fight. My hand don't shake none."

It was, in fact, as steady as a rock.

"Get your hand on your gun."

"Nope, I'll keep it here till he makes his move. I'm givin' your cross every chance to get in its work, see?"

"Maybe he won't sight you."

"Maybe."

"Then...?"

But the words froze on her lips. The eyes of Dix Van Dyck had widened and narrowed suddenly, and into them came the gleam of recognition. She knew that somewhere behind her a man stood, staring at her companion. Death was there—its wings outspread—hesitating over which to strike.

Then the hand of Dix Van Dyck shot down, and a gun flashed with a crazy wobble over the edge of the table. The wobble came from the force of the explosion that kicked the muzzle of the gun high. No answering shot. She rose, whirling from her chair, and saw a tall, thin Mexican in an enormous sombrero, toppling backward. From his outstretched hand a revolver dropped. He struck a post, staggered, and then pitched forward on his face. With both his guns now in his hands Dix Van Dyck stood like one transfixed, staring at his work.

She caught at his arm. "Follow me. Glasgow will be here in a jiffy."

She fled before him toward the door, through it, and into the blessed dimness of the night. A form raced toward her.

"What was it?" shouted the voice of Glasgow in her ear.

"A Mex shot," she answered. "Your man's inside."

He leaped into the door of the saloon with his gun poised, and at the same time she saw the big form of Van Dyck lunge across the street, making for the stables. In a moment she sprang into her own saddle and waited.

In hardly more than half a minute there came a thunder of galloping hoofs over the wooden floor of the stable, and she spurred into place beside him. Behind them babel was issuing from the door of the dance hall and pouring out onto the street, but a winding of the way shut them from her view almost immediately.

He was well mounted, she saw at once, not on a horse like the matchless stallion that carried her, but on a tall charger that covered the distance with mighty, swinging strides. He towered above her on this steed by a whole foot, and she felt suddenly reduced to impotence again, as she had felt when she sat opposite him in the dance hall, waiting. However, he reined in his horse when she reined in hers, keeping always half a length behind her. At length she reduced the pace to a gentle trot.

"No chase?" he called.

"Nope."

"What's wrong?"

"They know you're with me."

"Well?"

"They know I'm hard to catch."

He chuckled through the dark, and she added rather spitefully: "Besides, they'll wait for your bad luck."

"Bad luck be damned!" cried the ringing voice of Dix Van Dyck. "I've broken the bad luck to night."

"Is it better," she queried almost angrily, resenting his confidence, "to be a free man in Double Bend or on the run in the desert with Marshal Glasgow behind you? I ask you that man to man? Is that good luck or bad?"

"Any way you want to put it," he replied carelessly. "It's the sort of luck I want. Besides, there's one more burr under the saddle of Seņor Oņate, damn his eyes! Where'll we camp?"

"Up this caņon to the left a few miles. There's a good spring there and a circle of cottonwoods. We'll camp in the center of 'em."

"Risk a fire?"

"I tell you, they ain't going to hunt you to night. They know you're with me. They know my hoss can carry double farther and faster than any of their ponies. Maybe they won't hunt at all but trust to your bad luck."

Over this he brooded in silence while they worked their way up the rough bed of the ravine until they reached the circle of trees. They were ancient, mighty cottonwoods, nourished by the water from the spring.

In the center of the little grove they kindled a fire, for they found an abundance of dry wood and the whole, half-rotten trunk of a fallen giant. Then, propping themselves against their saddles, they sat on opposite sides of the fire. He rolled and lighted a cigarette, and she sat with her hands locked in front of her knees and her face turned up to the stars. Even the sailor has less love for the stars than the dweller of the desert. To the sailor they are guides and steering points, but to the desert dweller they are friends—the eyes of friends who look down through the long, breathless silence of the nights.

The two held their positions for minute after minute, unchanging. They were happy, for the quiet, the sense of space that was their proper environment. Now and then the flicker of the fire flashed clearly across their faces, but for the most part they were withdrawn and lost in the deep gloom of the night, and the glow of the fire with its thousand shadows actually helped to conceal them.

Tall, broad, black as the heart of the night, the cottonwoods fenced them in. There was but one way for them to look, and that was straight up, past the dizzy tops of the trees and on to the yellow lights of the stars. Up to these the girl stared, but the man, his head lowered to the palms of his hands and his face made ominous and ugly by the fire-shadows, stared steadily across at Jack. An age-old instinct, perhaps, directed them, for woman looks up—in acceptance—and man looks down—in doubt. By the flare and the leap of the fire he was studying her features, and every penetrating glimpse was like the reading of a new page in an endless story, each one strangely revealing.

Finally he got some fresh wood and piled it discreetly, so that it made a thin little arm of flame, stabbing into the night, and by that light he could look steadily at the girl. She paid no attention. Her face was still raised, and her expression was one of deep, vague content. Looking at her in that manner he could well understand that no human thing in all the world was necessary to her. It gave her a singular charm—this independence of attitude. Also it was deeply challenging. It made him long to break through her reserve. Without knowing it, he adopted toward her little house hold gods the attitude of an iconoclast.

"DID y'ever hear about souls that get tangled up after death and come back to earth in the wrong shapes?" he said suddenly.

"I dunno," answered the girl. "Seems to me like I heard something about it. Why?"

"Well, I been thinking, wouldn't it be funny if the soul of some old sourdough come back and hopped into the body of a beautiful girl."

"Well?"

"It'd be kind of funny, that's all," he murmured contentedly.

"Hmm," said the girl. "Maybe you don't no ways mean me by that?"

He was much surprised. "You? Did I say you?"

"Which I'm sort of silent," she explained suspiciously.

"Well, it'd be a funny thing, eh?"

"That idea don't interest me none," she said coldly.

The silence fell heavily over them. Each knew each was thinking of the other. As for the girl, she did not understand very clearly the imputations behind the unusual question of Dix Van Dyck, but what she did feel most acutely was the challenge of his personality. It was, in a way, like a hand that had reached out and touched her on the shoulder, compelling her attention. She resented it keenly and strove to fasten her attention once more on the cold twinkle of the stars.

"D'you know," she said, thinking out loud, "that, when the stars are as bright as they are to night, sometimes I feel just as if the old earth was pushing up closer to them... feel as if I was sailing right up through the air!"

"Hmm," grunted Dix Van Dyck. "That idea don't interest me none."

She admitted the counter thrust by nodding her head sharply and scowling across to him. His vast, boyish grin of delight met her eye, and she jerked her head back to stare once more at the stars. However, she was grateful that the night would obscure the burning heat of her face.

The stars, alas, had grown into a confused swirl of faint light. She found that she was making no effort to see them clearly. She was concentrating on the effort to find an answer to this insolent fellow. All the time there was that old sensation of surrounding strength—surrounding personality. The man was reaching out to her. For what?

"I feel," she said, "as if I was inside a house, and you was knockin' at the door. What d'ye want?"

"If you was inside a house and I was knocking at the door," responded the irrepressible Dix Van Dyck indirectly, "I got an idea that the door would stay locked."

"I got an idea," said the girl coldly, "that you're right."

This reply somewhat damped his spirits, but he rallied himself sternly to the trail. After all, she was only a girl. Yet, he began to guess more and more clearly at the soul of the sourdough.

"There ain't no use bein' strange," he assured her. "You might as well get to know me today as tomorrow."

"Tomorrow," she said calmly, "I ain't going to be with you."

"If you leave," he announced, "I'll follow."

"I'll go straight back to Double Bend," she said maliciously.

"I'll ride after you to Double Bend."

"To Marshal Glasgow?" she asked in real alarm.

"Why not? I'd take a chance with him."

"Some men was born fools, some educated fools, and some fools by choice, and I'm thinkin' you're all three rolled into one."

Nevertheless, she was much moved. Her voice told the tale.

"Now that this here partnership is begun...," he started.

She cut in: "Who said partnership?"

"Why," he cried with a voice of much pain, "I thought all the time that was understood. Which was why I tried out the bad luck back there in the dance hall."

"Now," she answered scornfully, "you're lyin'. You done that for pure deviltry. I seen it in your eye."

"Anyway," he went on contentedly, "that was the way I understood it, so we'll leave it there."

"Will we?" she said with rising anger. "Am I going to have you trailin' me around the desert whether I want you or not? Say, Dix Van Dyck, ain't this a free country?"

"Are you pretty mad?" he asked cautiously.

"I am!"

"Well, that's good."

Her anger apparently choked back further words.

"Yes," he explained, "it shows we're on the way to being friends. That's what I've learned from women. Get 'em mad and they're two-thirds yours."

"I s'pose," she answered with dangerous calm, "that you know a pile about women. Kind of a heart-breaker, eh?"

"I know quite a bit about 'em," admitted the man easily. "You see, I ain't been doing much all my life outside of fighting men and making love to women. Takin' it all in all, I don't know which is the most exciting, but I'd kind of put a woman above a gun fight."

She thought at first that it might be pure banter, but he spoke so steadily and evenly that she was deceived. Then, remembering his manliness and courage earlier in the evening, she took pity on him.

"If you're playing me for the common run of girls," she said, "you're on another cold trail, Van Dyck. Men ain't a thing to me. Less'n nothing, in fact."

"That just goes to show," said Dix Van Dyck, "that you're built along my own lines inside. You see, girls have been less'n nothing to me, too."

"What you been doing then, lying to 'em?"

"Sort of. Mostly sort of angling around and waiting for the right one to come along."

"I s'pose," she said scornfully, "that I'm the right one."

"Nope. Not yet. You look all right, but I got to glance you over a bit more before I take you."

An inarticulate murmur of rage answered him.

"You are mad, ain't you?" he said with an open delight. "Let's see?"

Reaching over to the fire he raised a glowing brand, twirled it dexterously till it broke into a small flame, and raised it so that he could look fully into her face. She winced away a little and obviously wished with all her might that she could cover her face from his sight. She was scarlet with shame and pride and rage. That pride kept her from turning away. That rage made her drop a trembling hand on her gun.

"Van Dyck," she said furiously, and her voice shook like the voice of a fighting mad man, "I've pulled my gun for less things than this."

"But you can't make your draw on me?" he queried. "That sounds pretty good for me, doesn't it?"

She was silent.

"I s'pose," he went on, "that in the whole world there ain't nothing you hate half so much as you hate me."

"Stranger," she said, "you must be reading my mind."

"Sure," he said, "I have been for some time." His voice changed and grew deeply serious. "Tell me why it ain't possible for us to make a team, Jack? I been talkin' foolish, but I just wanted to get you worked up enough to begin really thinking about me. Look at the two of us. Here you are with every man, woman, and child in Double Bend afraid to sit down by you. Why can't we hit the trail together and run north? No, I don't mean double harness or anything like that. I mean travel like man with man. We'll hit new country where we're new. You'll get a chance to forget that fool cross, and I'll get a chance to live without fighting for a week or two. Shake on it?"

He stretched a broad palm beside the fire toward her, and he saw the instinctive jerk of her arm to meet his gesture. He held his hand patiently. At last he withdrew it with a sigh.

"Think it over," he said quietly, "I don't want you to make up your mind too quick."

Still no answer.

Then, suddenly, so that he stared where he sat and narrowed his eyes to peer at her, she said: "Van Dyck, are you talking as man to man or as man to woman?"

The solemnity of it took his breath. The light answer tumbled to his lips and fell heavily back again. She was sitting very straight, and he could make out the glow of her eyes as they reflected the firelight.

"If it's man to man, you'll go with me, Jack?"

"Right! Tell me straight, Van Dyck," she said.

The truth came up to his lips. It came and formed itself in words, surprising the speaker more than she who listened.

"IT'S man to woman, Jack."

A pause came. Now that he had spoken, his mind swirled as he examined the appalling truth.

"I kind of thought so," said the girl. "I'm sorry."

He answered: "So'm I. Damned sorry, Jack."

"I was hoping," she said wearily, "that we could be pals."

"So was I," he said faintly.

She stood up. "I'm going to turn in."

"I'll sit here by the fire a while."

"Better not. You'll have a pile of riding to do tomorrow."

"But I got a pile of thinking to do right now."

"All right. Good night, Van Dyck."

Her hand went out to him. He shook it gravely with a reverent touch, and afterward with a vacant eye watched her preparations for the night. They were quickly made, and almost at once she lay wrapped in her blanket with her boots under her head. He bowed his forehead against his hands and pondered the situation gloomily. He was trying to retrace the course of the rough banter that had led him, at last, to this strange exposé of his own emotion. Then vague conjecture filled his mind of what she would do, and of how she would act toward him in the morning. He was in the position, in a way, of one who has striven to take the fort by storm, and, being repulsed, he must content himself with laboriously laying siege to the place and waiting for days and weeks and even months to tell. These thoughts in turn grew dim in his mind.

A pain in his back suddenly recalled him. He found that he had fallen asleep and must have sat in that cramped position for hours. Already the gray of the dawn was outlining the eastern hills. Every movement was a pain as he rose and stretched his limbs; the blood came tingling back, and he laughed at his own folly.

Then he turned to see if Jack was smiling silently at him. But she was gone. Perhaps she was foraging for wood with which to rekindle the fire. She was not there. He turned with a frown and swept the ravine up and down in search of her, but nowhere was there the glimmer of the white horse. Still scowling, he gathered an armful of dry wood and started the fire freshly. Perhaps she had gone for an early morning canter. Then, as the light flared, he glimpsed something white that stirred and fluttered under a rock.

It was a jagged corner of paper and, on it, scrawled almost illegibly as if it had been written by firelight, he read:

Keep straight up the valley; follow the river north on the other side of the mountains. I ain't leaving because I don't like you but because I like you too well.

Jack

He read it over once. He read it twice. He read it again before the full meaning trickled like light into his brain—light through a keyhole. Then he swore softly, steadily as running water. Once more his gaze swung around the horizon, but he could not even guess. She might have gone toward any point of the compass.

Dix Van Dyck felt the most tremendous loneliness of his life. It welled up in him like water—it brimmed him to the throat. Over such rocky ground it would be very hard to trail her. He stared up at the mountains as if they could speak to him.

One by one and range by range, they were swinging up out of the purples of night and on their highest summit already there was a stain of rose and a stain of yellow—indiscriminate splotches of color startlingly vivid, as if a giant with an invisible paint brush were smearing them at random. But they were all unknown, all strange faces that looked down at him. He knew at once that he could never trace her in this rock wilderness. The very fact filled him with a limitless desire to find her—a strange mixture of emotions. Not love, exactly, but something like it. It was rather the sense of loss that comes to the prospector when he makes a rich strike, goes away for provisions, and returns to find that he has lost the location of his treasure—a lost mine in the desert. Men have been known to waste their lives following some such intangible clue, and Dix Van Dyck had this possibility of waste in him. The blood of the prospector who will follow the hope of a brave tomorrow across the desert year after year, rejoicing in the search rather than in the finding, was in his blood.

What Jack meant to him was merely a definite goal toward which he might strive. The energy that he had dissipated in a thousand careless and reckless ways now centered toward one purpose. She was his vanished mine, his lost treasure. She was priceless because she was unknown, guessed at. Her beauty, her strangeness, the singular superstition that surrounded and accompanied her, all had a part in making him turn toward her.

He set himself methodically to discover a way in which he might capture her again. It was, in the first place, obvious that he could never outstrip that glorious white stallion she rode. Even if he could, it was equally certain that he could never trace her through an unfamiliar country where the hand of the law might be lying in wait for him at any turn. One hold, it seemed, he possessed over her, however intangible it might be. She liked him. Perhaps she liked him for somewhat the same reasons that he liked her—because he was different, unknown to her either by type or example.

He had often stalked young antelope, lying prone in the grass within their sight and raising now and then a foot and leg to show over the top of the verdure. The antelope would stand, watching the strange appearance with bright, fascinated eyes, and then come a little closer to examine it. Always they kept on, with a curiosity greater than their caution, until at last they were within easy shooting distance.

He felt now, in the same way, that he had only to remain there quiet and at length the girl would circle back to the place. Yet this might mean a delay of days and days, and in the meantime the hounds of the law would be on his track. Moreover, the one thing in the world that he could least endure was inaction.

It was on this account that he chose the least promising way of reaching her. He skirted about among the rocks until he found the trail of her horse as she had ridden from the camp. Small, short steps they were at first, and the traces of the girl's boots went alongside. Apparently she had led the horse for a short distance from the place where Dix slept by the fire, and she had held back the stallion so that his steps would fall lightly on the rock. In a little way the double track ceased. The four prints of a standing horse were plain where she had mounted. Then the steps of the horse grew wider apart and more distinct. She had gone on from there at a trot.

The direction was straight across the ravine, at right angles to the course she had told him to pursue up the valley, across the mountains and then following the river to the north. Dix Van Dyck growled to himself. Certainly she had intended to leave him in the lurch. He fastened his eyes on the rocky side of the ravine and trotted his horse up the steep slope. The signs were not hard to follow. The iron shoes of the stallion, striking the rock, chopped off little fragments that blazed away as plain to the practiced eye of Dix Van Dyck as if the course had been marked in ink across white paper.

He came now, however, upon a harder strata of rock where a glass would be necessary to follow the imprints even of iron shoes. But at this point the trail wound sharply to the right, as if the rider had swerved from the hard rocks by preference and chosen a course along the gravel at the side. This swerving trail puzzled Dix Van Dyck deeply. It was most unusual for a rider of the desert to change a course because of so slight an obstacle, particularly when riding a shod horse.

However, he did not waste time in wonder. He was too interested in the fresh trail. By the way the sand had drifted in upon the tracks, blurring them under the drive of the brisk wind, she could not have passed that way more than three hours before. His heart looked up with hope.

In this manner he came to the crest of the ridge along the left side of the caņon—a sharp crest, dipping down on the farther side almost as abruptly as it rose from the first valley. Just past the summit the trail veered sharply to the left and stopped in a maze of signs. It was a great slab of reddish stone, of copper coloring, but even that hard surface had taken numerous imprints. In a hundred places the stone was marked, and, as he read the sign, the horse had several times turned around and around here, as if chafing under a restraint that held him for an appreciable interval. Examining the ground at the edges of the rock, he caught the imprint of the girl's boot. She had dismounted here, then. The track was very fresh—not more than an hour old, as far as he could judge, though even the most experienced, he knew, often go astray in such matters.

Why she should stop here when she was barely started on her way he could not by any means imagine. A brief halt might be explained in a hundred ways, but here she must have kept the nervous, restive stallion for a full hour, or even more. Such marks could not have been made in a much shorter period. Finally he saw on a gravelly ledge a place where she had sat down.

Most certainly her actions were strange. He was so perturbed in the effort to unravel the meaning that he swung from his horse and sat down on the identical ledge where she must have been only a short time before. Then light broke upon him.

From that position, looking between two low ridges of rock at his left, he found himself staring down past the tops of the cottonwoods and onto the exact site of his late camp. There was still a faint column of smoke wavering up from the fire that he had hastily extinguished with sand—a slender mark against the atmosphere no more distinct than the tracery of a chalk pencil over a slate. She had stopped her horse in the shelter of the ridge and sat there to look back on the camp. She had seen him waken and stir about. She had waited there until she saw him take the trail after her. Did it mean that she actually expected him to follow her? Was that the meaning of the plain trail she had left?

He started up with an exclamation and swung into the saddle. Plain as writing down the slope her trail continued. He galloped along it with a reckless speed.

IN the capital city of the state Sheriff Oņate was a personage to be sought out and flattered with ceremonious greeting. The vast majority of the electorate in that state admired him for a pomp of presence and a grace of manner that no one west of the Mississippi could rival. Represented by a man of such dignity, they felt confident he would get for them all they might wish. It is true that Sheriff Oņate did not achieve much in the way of arrests, but his own small office was an insignificant matter. What really counted was his position in the state.

It was known that, if he dropped a word in the ear of the governor, action was apt to result. What number of votes Oņate controlled even he himself could not estimate. At least it ran up into the thousands. Accordingly, in the capital, men listened when he spoke. He was more revered in a lobby of the legislature than he was in his office in Guadalupe.

The time of his coming was particularly well chosen. For the state election was within striking distance, and Governor Boardman, though he had lined his pockets comfortably during his term, was not yet in such a position that he could build a house with white verandahs that he had in mind. Accordingly, there was probably no one in the entire city so glad to see the great sheriff as the governor himself.

All of this the sheriff knew perfectly well. He knew also that in his heart the governor hated the ground upon which he walked, and this merely increased the satisfaction of the benign Oņate. Straight to the offices of the governor he walked—walked, for he wished that many men might see him coming. That night many invitations to dine would wait for him at his hotel.

The man in the outer office had red hair and a pug-nose. He was a newcomer also. For both reasons his reception of Oņate was far from cordial, for he saw in the smoky whites of Oņate's eyes that the man was of Indian blood, and the Irish remain the Irish the world around. He told the sheriff to sit down and wait his turn. Whereat the cheeks of the sheriff swelled with poisonous anger.

Luckily, the private secretary passed through the outer office at that moment. The effusiveness of his greeting made amends in some degree. With one eye Oņate enjoyed it; with the other he relished the red-faced discomfiture of the pug-nosed Irishman. He followed the secretary into the inner sanctum.

The governor had just signed an important letter and was screwing back the gold-chased cover of his pen while he pondered deeply whether or not he had made his terms a little too cheaply with a certain corporation. At sight of the sheriff he rolled to his feet—literally rolled, for he was a very plump little man and slid into and out of a chair with a singular undulatory motion. His pudgy hand met the soft palm of Oņate, and they smiled upon one another. If the color of their skins was different, the color of their hearts was the same.

"I have called...," began Sheriff Oņate, tucking his hat under his arm and half bowing.

"Cut out the formality, Don Porfirio," said the governor breezily, "and try that chair... no, that one by the window. Here's a box of cigars... and here's a milder brand."

In slang the governor kept abreast of the times. If in other things he backslid a little, he did not lose votes thereby. So the account left a comfortable balance in his favor.

"Shoot!" repeated the governor and, so saying, he balanced his stubby feet on the edge of his desk and smiled again beneficiently upon his visitor.

"I have called," went on Seņor Oņate, "to find out how the election promises and to learn what I may do."

He was never quite sure of his English, and the result was that he always spoke it with a painful grammatical correctness.

"Everything!" exploded the governor. "You can do everything, Oņate. I came into office by the flicker of an eyelash, and I'm liable to go out again by a lot bigger margin. Some of the boys don't like my policies. They claim that I'm too partial to the Mexicans." Here he winked broadly, the whole side of his face wrinkling with his mirth. "Of course, that's nonsense, Oņate!"

"Ah," murmured Seņor Oņate, "naturally it is nonsense. You will smile, sir, to know that in my district the Mexicans think you hold a prejudice against them."

The governor still smiled but in a sickly fashion. "But you, Oņate, will round them out of such foolishness?"

"I?" said Oņate, and he waved his pudgy arms. "I do what I can, but, when ten thousand tongues start wagging, I cannot stop them all... not without great trouble."

The governor knew the symptoms. He waited for the request that he knew was coming and guessed at its size by the length of the prelude—an infallible token. The picture of the big house with the white verandah grew dim in his mind's eye.

"However," went on Oņate smoothly, "I do what I can. I talk here, I talk there. But at my heart, ah, seņor, my heart is troubled with doubts."

"The hell it is!" exploded the governor, rolling half out of his chair. He gripped the arms of it and controlled himself with a mighty effort. "I'm sorry to hear it, Oņate. Let's have the reason."

As for Seņor Oņate, he was rolling every second of the situation under his tongue like a seasoned gourmand. "I wrote not many days ago asking the governor for a thing... for so little a thing... it was merely to scratch with a pen on paper... so! But there came back a note of few words that said: "I will not do it." I was much grieved. I am still troubled."

"I refused you?" queried the governor in real astonishment. "What was it about? The matter's out of my mind."

"It was the matter of a man's life," said Oņate. His next words snapped out with a little harsh purr after each one. It was like the warning of the rattler before it strikes. "That of Seņor Van Dyck... the swine... the pig... the dog who murdered my brother... my brother, Vincente!"

The violence of his emotions set him wheezing, and he fell back in his chair with heaving chest and closed eyes. In the moment during which he could see without being seen the face of the governor hardened into sardonic contempt. He smoothed it to a look of serious concern when one of Oņate's small eyes squinted open again.

"About that matter," he said, "I remember now. But your enemies advised you to send the letter to me. It would have been to your harm if I had done what you asked."

"To my harm? To mine?" cried Oņate, so surprised that he forgot both anger and grief.

"Exactly," explained the governor. "When I got your letter asking that Van Dyck be outlawed by proclamation, I looked into the thing. This is what I found. Van Dyck is a big, husky fellow who has run about getting into mischief all his life. But there's nothing venomous about him, and, though he's killed several men, he's always acted in self-defense. I can't have a man like that outlawed, Oņate."

"And my brother," said Oņate with ominous quiet, "is he not to be avenged?"

The heat that had been accumulating for some time in the governor broke out in a noisy surge. "Your brother," he said fiercely, "got two hired murderers and attacked Dix Van Dyck from behind. Van Dyck tore a shelf down from the wall of the saloon, brained two of the men, and strangled your brother, Vincente. It was a fine thing for a man with bare hands to do. And by God, he's not going to be touched for it! That's final!"

The sheriff, for a time, sat speechless. It was, perhaps, better for him that he could not utter a syllable, for during the interim the governor had a chance to quiet down, and very brightly there rose again in his mind the picture of the broad house, the white verandah, the stretch of green lawn, the pleasant vista down the hall and from room to room. For four years in his dreams he had wandered through the apartments of that mansion. And now he was destroying the thing he loved. He was throwing away perhaps ten thousand votes; he was signing his abdication. For whom? For a wild daredevil somewhere in the south country, a ne'er-do-well, a good-for-nothing mischief-maker. The sweat stood out upon the forehead of the governor.

"So!" breathed Seņor Oņate at last, and heaved himself slowly from his chair. His basilisk eyes glittered against the face of the other. Between fat thumb and fat forefinger he reduced his cigar to a shapeless pulp; he dropped it on the floor; he ground it under his heel and into the fine, soft carpet. All the time his silent eyes were saying that such were the things he would relish doing to the chief executive. "So!" he said for the second time, tucked his hat under his arm (as he had seen a fine gentleman do once in a picture of olden days), and turned toward the door.

"Wait!" said the governor weakly.

But Seņor Oņate proceeded toward the door, though with a shortened step.

"Wait!" called the governor, and enlivened by his alarm he sprang after the Mexican and seized him by the arm. "What the devil, Oņate, you're not leaving me like this?"

"I have stayed long enough," said Oņate, his voice still broken by panting, "to learn that what I have heard is true. You care for nothing... nothing but the gringos. Mexican gentlemen may be shot down in cold blood by white dogs who drink their blood. You do not lift your hand. You do not care. Pah! I have stayed long enough... too long!"

He turned once more toward the door, but this time the governor seized him by both shoulders and whirled him around.

"Come back here, Oņate! Listen to reason, man!"

Oņate waved both his short arms and, in so doing, brushed off the grip of the governor. "This," he moaned, "is my reward. I who have slaved for you. I who have brought you votes by the thousand and the ten thousand. I who have held you in my heart for a friend."

Grief, self-pity, raised real tears to his eyes. The governor was much moved. He pushed his visitor into a chair—so hard that he landed with a thump that cut short what promised to be a sob.

"Oņate," he said, "rather than break off our friendship, I will do what you wish. I will have the proclamation prepared."