RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

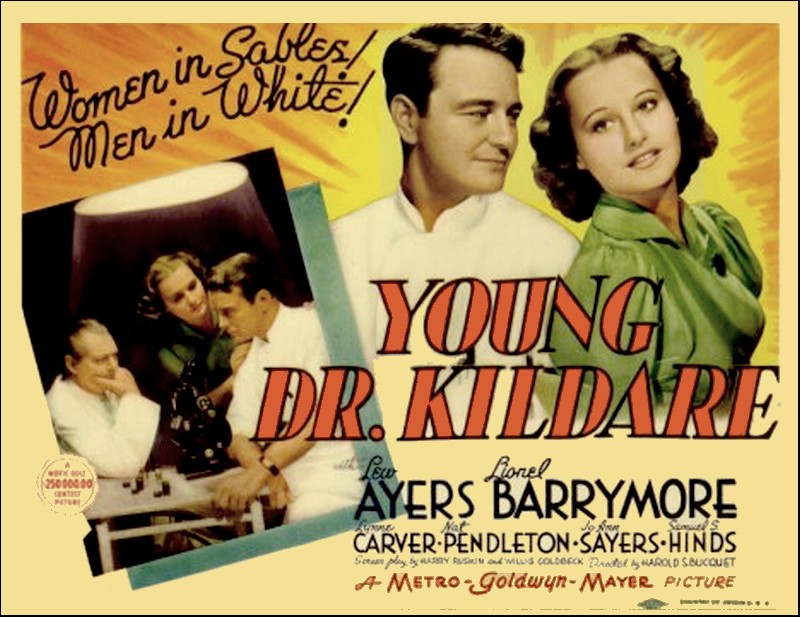

Argosy, 17 December 1938, with first part of "Young Doctor Kildare"

"Young Doctor Kildare," Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, 1941

THE three who loved him had prepared the house for the homecoming of young Kildare. From front door to kitchen they had polished and rearranged, and the only room left free of summer flowers was the parlour. This sanctum of the New England home had been turned into an office so that Dr. Lawrence Kildare could have his medical headquarters on one side of the hall, as usual, and on the other side would appear the brass door-plate of Dr. James Kildare, his son.

To be without a parlour was something like being without a face but Lawrence Kildare was determined upon the sacrifice because, as he said, they were welcoming Jimmy home not only as a son but as a doctor. The twenty years of schooling had ended; he had received his degree; and now he must be made to feel that he entered this house upon an equal footing with the oldest man in it. That was the way the elder Dr. Kildare put it, modestly proud of his own humility.

So they had stripped away the flowered carpet for the sake of a tan rug, replaced the family photographs with Jimmy's framed diplomas from grammar school, high school and college. For the bric-à-brac in the corner cabinet they substituted from the attic reserves a solid mass of battered medical journals and antiquated texts; above all the round table with its bronze bowl gave way to a big mahogany desk. Martha Kildare found it at Jefford's secondhand store and her hands polished it brighter than new. Now she leaned to blow a speck of dust from the shining surface; with her handkerchief she scoured away the spot of mist which her breath had left; and then she gave her attention to Beatrice Raymond who was reading aloud, softly, the words which old Dr. Lawrence Kildare had written on the white scratch pad that lay in the centre of the desk-blotter. The gravity of the words had caused him to write them with care, like a schoolboy copying a text, but the tremor of his seventy years appeared in the capitals with which each word began:

Welcome Home To My Dear Son, For Ever!

As she finished reading, Beatrice Raymond lifted her head

and murmured: "After all this, how terrible it would be—"

but then she was stopped by the anxious, searching eyes of Martha

Kildare. Beatrice wore a summer dress of organdy with a flowery

pattern climbing dimly over it to her brown throat. Now she held

out her skirt daintily and turned like a mannequin. "Do you think

I'll do, Aunt Martha?" she asked. For they were such close

neighbours that they had to use family names.

"Darling!" breathed Mrs. Kildare. "But don't you think you ought to wear the little jacket to the train? It has such a sweet ruffed collar."

"It would cover my arms, though," answered the girl, "and I think he ought to see how I've improved. I was all elbows, two years ago."

"As though your points were to be counted, and you were a prize calf," said Martha Kildare.

"Calves twenty years old generally are called cows," remarked Beatrice.

"Beatrice!—But what do you mean?" asked Martha Kildare.

"I don't know, exactly," answered the girl, "only I hope it's more than a calf affair—"

Old Dr. Kildare began to be nervous about train-time. They still had half an hour for the eight-minute drive, but then there is always the danger of a tyre blowing. He bundled his wife and Beatrice into the car which had done five years of slow service and would do five years more.

On the way to the station, the wind fluffed the organdy dress and whispered in her hair with a small voice of unhappy prophecy. When they reached the station the doctor looked gloomily around, saying: "You'd think some of the folks might have turned out to welcome Jimmy."

"He never made many friends—but always fast ones," said the mother.

"Well," chuckled the doctor, "it's true that he always hewed to the line and let his fists fall where they might. But maybe they've knocked some of the fight out of him back there in Hillsdale—What's the matter, mother?"

"I forgot to baste the turkey before I left," she exclaimed.

"You have the fire turned down low, haven't you?" suggested the doctor.

"Yes, it's down low."

They got out and stood on the platform. It faced north, and even in August the shadow was iced with a remembrance of winter. An express-man wheeled out a hand-truck. Eccentric old Jim Carrington walked back and forth with a long stride, getting a good constitutional out of the ten-minute wait. Then Phil Watson and Jigger Loring and Steve Barney joined the doctor's group, smiling, talking cheerfully about how fine it would be to have Jimmy back, and all the while their self-conscious eyes avoided the prettiest girl in town. If only Jimmy had not grown too big for the town!

Then the train was there on them, swaying its tall forehead around the bend, looking as important as a trans-continental limited. The engine shut off. It rolled on momentum; the brakes took hold, passing an electric shudder of vibration into the steel rails; the train stopped. A dozen people were dismounting.

"Beatrice, he couldn't have missed it!" whispered Martha Kildare.

But there he was getting down last of all with a time-bitten suitcase in his left hand and a book in the right, the forefinger keeping a place. That suitcase had been quite fresh and leather- looking when she helped to pack it two years before. Jimmy had changed, too.

He himself was aware of the alteration as he stepped down the platform, but he felt that the cool of the wind which fingered through his clothes was seeing him more clearly than human eyes. He had a new body. Physical labour had built him up and stressed the important muscles like underlined words on a page of print. He was not proud of that body which his clothes masked but it gave him a more secure and comfortable sense of equipment for the world he was entering.

He put the suitcase down, which gave him a left hand to shake with the three high-school friends. They said: "Hi, Jimmy?" and "Whacha say, old boy?" and "You look great!" Then his mother got to him. She was sixty years old, for Jimmy was a late-born child. She had a high-blood-pressure look, reddish purple high up the cheeks. She was too fat. Between elbow and shoulder the flesh bagged down against the sleeve. Age puckered her eyelids and the weariness of woman was in the eyes. He held her close a moment then turned to grip his father's hand. The old man was standing too straight. A blow would break him now, for he could not bend. His old-fashioned, professional mask of sharp-trimmed moustaches and pointed beard seemed detached from the face like a wig that barely adhered.

After that he kissed Beatrice. She stood up on tiptoe and turned her cheek like a child being kissed by an older relative. They went on to the car. In the rear seat, he stood up his suitcase between their knees and made sure that his finger had the right place in the book. He made doubly sure by glancing at the page.

... after the fever has persisted with severity or even with an increasing intensity for five or six days the crisis occurs. In the course of a few hours, accompanied by profuse sweating, sometimes by diarrhoea, the temperature falls to normal or sub-normal.

The crisis may occur as early as the third day or may be delayed to the tenth; it usually comes, however, about the end of the first week. In delicate or elderly persons there may be collapse...

"What do you think of your Beatrice now?" asked his

mother, who was turned about to gloat over him.

"Beatrice? She's great," said Kildare.

"'It usually comes about the end of the first week,'" he was rehearsing in his mind, and there had been a thought knocking right behind his teeth, except that his mother's interruption checked it. He would have to pray that it might return; perhaps it was the diagnosis that he searched for. The question made him look again at Beatrice. She held up her chin and turned her head for him, fixing her smile.

"Don't be silly," said Kildare.

"It's only a prop smile," admitted Beatrice, "but it's brand new and I thought it was quite good."

"See the new wing on the hospital?" asked Lawrence Kildare.

"No," said Kildare.

"He's thinking about something," decided Beatrice. "What are you thinking about, Jimmy?"

"Look back and you'll see it," insisted the father. "More than fifty thousand dollars went into that. It's going to bring surgery right up to date in our town."

Kildare looked through the back window. The hospital had a block to itself, surrounded by trees which were set adrift by the motion of the automobile; the top branches obscured the highest roof of the building. His eye glanced on up into the empty blue of space.

"They're all set for you over there," remarked the father. "You're going to have a happy interne year in our hospital, my boy."

"Ah?" murmured Kildare.

"What are you thinking about, Jimmy?" asked the girl.

"Children hate questions," said he.

"That's right. Be nice and mean. Be yourself," she answered.

He watched her relax, suddenly, with her hands folded in her lap and her eyes considering him impersonally. She had a special way of slipping into herself and looking out at the world.

Then he was walking up the path towards the house, carrying his suitcase, the marked book still in his right hand. The others fell away so that he had to step first into the front hall. All the hours of preparing were wasted on him. His eye found the brass door-plate which announced 'Dr. James Kildare' and remained on it.

"It was all your father's idea—oh, Jimmy," said his mother, "if you ever grow up to be half as good and wise as—There! See what we've done!"

"Well, look at that," commented Kildare. He took an idle step or two into the room. "How did you get rid of the old-fashioned funeral that used to be in here?"

"Jimmy Kildare!" whispered Beatrice, fiercely.

"Why, it's great," said Kildare. He wandered about the room with the book still in his hand. "Look at all these!" He flicked his fingers over the old journals in the curio case. He leaned at the desk. There it seemed to take him minutes to read the words which the meticulous pen of his father had written on the scratch pad. After that he looked up at the surprise and pain in his mother's face. He straightened himself with a jerk. "Who could want a better office than this?" he demanded of the world at large.

"Well, you've got sun, and air, and room for your thoughts," remarked the old doctor. "More than I had when I hung out my shingle. A good deal more. You remember, mother?"

But Mrs. Kildare was hurrying out towards her kitchen, and the doctor took his son into the vegetable garden to look over the shining rows of young onions. It was his belief that in the onion were locked up vital secrets of health and strength and long life. "Sulphur and iron turn the trick," declared Lawrence Kildare. "And so I've got an iron sulphide worked into the soil. You'll have some of those onions with your turkey dressing. Come to think about it, Jimmy, was there ever a great nation that got along without onions? Greece? Rome? When they grow rich, the onion disappears from the table; weakness of the soul and the body follow, decadence. Look at Egypt. Egypt, too. Wherever you find civilised man, you find onions—"

Afterwards, when Martha called that dinner was ready, he was saying: "I'm at the age which begins to get a bit weak in the knees, Jimmy, but with plenty of open air and with you to spell me, I'm going on for another decade, my lad."

"Of course," muttered Kildare.

He came into the dining-room with his father as a horse whinnied behind the house, beyond the vegetable garden. Kildare looked out the window at a big shining bay in the pasture.

"That's that Maggie mare of yours, of two years ago," he said to Beatrice.

"She's just six now, and full of beans," answered Beatrice. "I've taught her to jump because I know you like short-cuts across country. Try her later on and see if you'd like to keep her."

"Keep her?" exclaimed Kildare. He looked sharply at the girl, sticking his head out as though he were searching for offence and ready to find it. He said nothing more.

"But, Jimmy," his mother reproved, "don't you think it's the most lovely gift?"

"It's too lovely. I won't take her horse," declared Kildare.

"Why, James—" said the old doctor, amazed.

But Kildare had fallen into a brown study over the soup. He had hardly tasted it twice before he jumped up, exclaiming: "I have to send a wire. Maybe I've got it! Maybe I've nailed it down!"

"What, my lad?" asked the doctor.

"Oh, an old fellow in the hospital back there in Hillsdale. He's sick a month with recurring fever and nobody's been able to spot it."

Then they could hear his voice at the telephone in the hall, giving an address and adding for a message: "Suggest Bed Eight has relapsing fever please advise what results."

"Isn't Jimmy a little strange, Larry?" suggested the mother.

"Boys have to grow up," answered the old man, "and a grown brain needs occupation."

Jimmy came back into the room with the distant consideration of thought gone from his eyes. He smiled on them all one by one, as though he were seeing them for the first time. At his mother's chair he leaned a moment to say: "It's great to be back."

The mother and father shone with happiness. Only Beatrice kept examining him with a studious intentness.

Old Dr. Kildare said: "What have you fixed on? You've never said what it's to be—medicine, surgery, research, obstetrics—"

"I don't know," answered Kildare.

"Ah, but you have a preference by this time!"

"No, I haven't. I'm not so keen on any of them," said Kildare.

"Not so keen—" breathed the old man. "Ah, well," he went on, relaxing, "it simply means that you're ideally suited to the life of the country practitioner—a well-rounded business that keeps your hand in everything. Lots of good minds are looking favourably on general practice instead of this eternal, infernal specialising..."

AN owl started going ka-pooo-pooo, a fool of an owl who might have known that her sounding horn would frighten every young rabbit into hiding and turn the field mice into motionless little brown stones. No wind stirred to set the stars trembling, for the moon had turned the world to ice and covered the fields with silver; under every blade of grass its shadow was frozen fast in place. That was how it seemed to Kildare as he stood at his window, sleepless, but the night was as hot on his face as it was cold to his eye.

He turned, his monstrous shadow twisting before him on the floor. A fragrance of mignonette made the heat of the night more palpable. Once in his boyhood he had spoken of liking that perfume; a dozen years later his mother still remembered and that was why the jar of it bloomed on the corner table. He was stifled suddenly by more than the still heat of the night. He threw off his pyjamas, stepped into swimming trunks and tennis shoes, and walked out under the moon, his feet finding their own way along the path that moved crookedly through the adjoining empty lot.

He went on down McKinley Street and into the open country with trees walking slowly overhead between him and the moonlit sky. There in the clear the moon had the world to itself again until he reached the tangle of shrubbery and great willows by the river. It was a mere trickle at this time of the year but it was no spendthrift; it husbanded all its resources and spread them out like a purse of silver to make the big swimming pool. It was a famous pool. The boys drove twenty miles to come to its green banks; and he saw, at the bend where the pool turned out of sight, the sleek dark mark of the slide which had been used in the old days. In the centre of the water, the same old derelict of a tree showed the tip of its shoulder and one desperate, upflung arm.

He climbed to the top of the dead tree which made the highest platform for the bravest of the divers. It slanted out from the bank over a deep part of the pool—unless time and the soft current had drifted the sand-bank closer to the shore. He kicked off the tennis shoes and stood up straight. When he was ten he had stood there like that, showing his teeth with terror and hoping the other lads would think it a smile. They had thought so, as a matter of fact; that high dive plus the hardness of his fists had simplified his earlier years in the village school, but now he forgot the distance beneath him as he looked out over the trees at the little village. The street lamps were dim yellow jewels against the white dazzle of the moonlight. There was hardly enough of the town to fill the palm of the hand.

He gripped his body harder with his arms, then dived with a strong outward bound that left the stump shaking behind him. He thought he saw, as he shot down, a dimness of shadow under the face of the pool. Perhaps that was the loom of the sand-bank. But he made no effort at a shallow dive, cleaving deep until the tips of his fingers touched the ooze of the bottom; then he shunted himself up to the surface. The water yielded as life does not yield. He cut into it savagely, swimming a fast crawl, and then let himself drift face up. There was a bright star up near the zenith. He forgot the movement of the water and watched that single point of brightness until it began to shiver into rays; that was when he turned his head and saw the white figure sitting at the turn of the lagoon.

He stood up, treading water, and called: "Hi—Beatrice?"

"Hi," said the girl.

He swam to the shore and sat down on his heels, the water from his body pattering down.

"What's the idea?" he asked.

"I thought I'd cool off," said Beatrice. She was in perfect repose, leaning against a rock with her hands clasped around one knee. Her bare legs meant that she had a swimming suit under her dress, no doubt.

"Girls never come here," he pointed out.

"This girl does," she answered, and let it go at that, making one of those familiar pauses in which she was always so at home, and he so ill at ease.

He drew a little closer.

"Don't drip on me, Jimmy," she cautioned in that calm voice of hers.

"The shadow covers up your eyes," he said to explain his crowding. "I never know what you're all about unless I can see your eyes."

She made a slow gesture, drawing her hair back from her forehead so that the moonshine poured freely over her face. While he studied her, another long moment of pause came between them and the frogs began to sing their chorus of soprano, alto, and bass, point and elaborate counterpoint that dizzied the ear.

"It's no good," commented Kildare. "You're being sour."

"No, I'm not being sour."

"You're being sour. You always could subtract yourself from any scene from the first time I can remember."

"What's the first time you can remember?" she wanted to know.

"Ten years ago. I was sixteen. How old would that make you?"

"Ten."

"You had straight knees; and your socks never fell down in wrinkles. Your hair was brighter then."

"I'm sorry the hair went wrong."

"It isn't bad, when the sun hits it... You didn't have that mole on your cheek, then; you had two dimples instead of one; there wasn't any cleft in your chin; when the wind hit your hair it simply exploded all over the place and that always started you laughing. You had a sweet way of laughing, for a little kid... Are you only twenty, Beatrice?"

For some mysterious reason she required another pause before answering this simple question. "I'm twenty," she agreed at last, and seemed to have a little difficulty in getting out the words. "Why 'only' twenty? Am I producing too many moles and cleft chins and things? Do I seem a lot older?"

"No, but you're sort of filled out. I mean—well, I don't know. Let's have a swim and I can tell better."

He stood up and faced the water, stretching his arms up over his head and yawning some of the day's weariness out of his body, some of the trouble out of his brain. Behind him her clothes rustled. The dress fell to the ground like a patch of moonlight. She walked past him and tried the water with one foot.

"You look fine," said Kildare.

She stepped to the top of a five-foot rock, and the water slapped softly together behind her feet as she dived. She came up in the middle of the lagoon.

"You got a kink in your back and your head was crooked," commented Kildare. "You were diving better two years ago."

Without waiting for her reply, he cut from the rock into the water, rising beside her.

"Let's see you crawl," he commanded.

She turned on her face and crawled; Kildare followed beside her, his head raised so that he could watch. At the farther bank she made a racing turn that plunged head and shoulders under, but as she came up he said: "That's enough. You're wallowing, you're not lying out straight."

"Sorry," panted the girl.

"I had all that wallow out of you, two years ago—and now you've lost your wind, too."

"I'm sorry," she repeated.

"Sorrow won't get your wind back. A bit of roadwork would, though. If women would do some cross-country jogging it would be fine for their hips, too."

Instead of answering, she walked out of the pool, sleeked some of the water from her body with the edge of her hand, and sat down in the grass.

"Come back in and let me see if I can't straighten out that wallow," ordered Kildare.

"Damn the wallow," answered Beatrice.

This got him quickly out of the pool. He stood over her.

"What did you say?" he demanded.

"I said: 'Damn the wallow!'" she replied, and tilting back her head a little, she looked up at him with a perfectly unmoved face and that blankness which always made him a little uncertain.

"Sit down, Jimmy," she said.

He astonished himself by obeying, a reflex action so swift that he did not have time to think out this moment.

"Stretch out and wiggle your toes and forget everything," she directed, and as he lay back she wadded the dress together and slipped it under his head. It gave him comfort, pressing up against the nape of his neck.

"Beatrice—" he said.

"Well?" she asked, absently.

"Four years ago we used to sit and talk like this."

"What of it?"

"But I was a grown man and you were only a baby. Great Scott, that would have made you only sixteen, or something. I never knew you were that young."

"I never was," she told him.

"What do you mean you never were?"

"I was born old," she said.

"How old were you born?"

"About your age, I suppose," said Beatrice.

He studied this question and her face at the same time. There still was moisture from the pool shining on her sun-darkened skin. Where the chin rounded and the throat filled he considered the shadows that moved with her movements. Along the cheeks, the shadows became intricate delicacies.

A sense of comfort increased in him. It grew out of the coolness of the grass and the warmth of the air. Down in the pool, ripples still splashed along the shore but the quiet was returning. The troubles which had been wearing his brain threadbare were gone; he did not want them back.

"Four years ago," he said, "I was out of college and all that—and you seemed eighteen or twenty even then."

"I put on long skirts when I was fourteen," she explained, "and made father get me a horse."

"Why?"

"You were back from your sophomore year and you liked riding. I put a mean bit on that poor horse. I used to make him dance and then talk big to him. You noticed me quite a lot that summer."

"Are you trying to tell me that six years ago you'd made up your mind—" he began.

"Ten years ago," she corrected. "Some people are clever and do things fast. Some of us just find out what we want and keep pegging."

He turned his head and stared at her until she laid a hand over his eyes. With her fingertips, she read his face as surely as the blind read Braille.

"You mean that when you were only ten—"

"Hush!" she said.

She touched the lines beside his mouth.

"These came from working in the grain fields," she pointed out, "and from the first of the month when there were plenty of bills and not much money... Here's the jaw muscle turning into tougher rubber all the time. This is what says: 'I will last out the day; I will live through the year; I will win that scholarship.'"

He drew a long, long breath.

"If you weren't making me quite so happy, you'd be putting me to sleep," he told her.

"These are all new—these long lines across the forehead," she went on. "They say: 'What is it I want and when will the answer come?' But down here between the eyes, getting darker and darker—these are the hours as deep as wells where nobody can go but Jimmy by himself."

He caught a quick breath which would not go out of him for a moment in speech. Then he was able to say:

"I love you for that, Beatrice."

"How much do you love me?"

"As high as the sky," said Kildare.

"I see," murmured the girl.

"What do you see?" he asked.

"It's only boy and girl stuff to you, still. And Dartford isn't big enough to give you room for growing."

He said nothing. With the ball of her thumb she tried to rub away the frown that had settled between his eyes. Then she said: "If you have all of New York and ten thousand cocktail parties, and your name in the big papers, what does it matter when you get to your father's age? And isn't his life good enough? If you've gone to your patients in a Rolls-Royce with a chauffeur or driven yourself in a Ford, in the wind-up, it's just the sick people you've helped that matters."

"It's not that—" he began to answer. "What makes you think that I'm not going to stay here?"

"Listen, Jimmy. I know you so well that I could even pick out your neckties. I know how to shut up and never say a word when you're sour. You want clean shoes, but not shiny ones. You like to dance, but not with a big crowd. I know all your favourite desserts. I know every dish of your mother. I've learned camp- cooking; I've practised these two whole years with a rifle; I can even pack a mule and throw a diamond hitch and I've hiked Collum Hill twenty times so I could be used to rock climbing and all the things you like."

"But wait a minute. But, Beatrice, you're a thousand times too good—"

"Be quiet a moment. Jimmy, Jimmy, I've got some money of my own, and we could buy the Andrews house with a small down payment and I've spotted every good stick of secondhand furniture within twenty miles. I've haunted every shop and dickered for low prices till they hate me."

He put one arm across his eyes; she watched the tension of his mouth.

"There wouldn't be any babies until—well, until the right time came." She laughed a little but Kildare was silent. Then she drew away the arm which covered his eyes.

"Is nothing any good?" she asked.

"Old dear, I want to explain—"

"You want to explain that women are great stuff and all that, but you have something else in your mind. One of these days you're going to wake up, Jimmy, and the girl who fills your eyes when you step out of your trance is going to get the sort of love that only comes once in a century. When that day arrives, I want to be there."

He put out his hand. She placed hers in it, palm up, watching him closely.

"No," she said. "It's no good. Not even with the moon helping. You simply don't want this girl."

"I do, Beatrice," exclaimed Kildare. "I think you're—"

"Hush!" murmured Beatrice. "There's only one last thing to say. That's about your father. He's worked hard for you. If you go away—remember that he's an old man. He's brittle with age. He can't stand up to shocks. And he counts on leaning on you from now on."

He sprang up to his knees, arguing with violent gestures of both hands. "I'd rather lose a leg than hurt him or disappoint him; but—I don't know how to put it—there's something in me that has to try to come out and there's no place for it in Dartford."

She became silent, her arms wrapped around her knees, her head back as though she were looking at the stars; but her face was blind with suffering.

"It makes me sick to think that I'm hurting them or you," said Kildare. "And, Beatrice, how did you know that I wasn't going to stay home and put in my year as interne in that little one-horse hospital? How did you know?"

"Kiss me, Jimmy, will you?" she asked.

He leaned over hastily and kissed her.

"I do love you," said Jimmy. "You're more to me than anything in the world, practically."

"Now you go along home, please," she said.

"And leave you out here alone? Don't be crazy!"

"I've got to be alone," she told him. She had her head back still and that blind face of pain frightened him a little. "If I were going to cry about it, then I'd want you to stay here and comfort me; but it's not that way."

"But sitting here—all alone—what are you going to do, Beatrice?"

"I'm going to unravel a lot of knitting and start all over again on a different piece," she answered.

Of this he could make nothing. "You really want me to leave you?" he insisted.

"Yes," she said.

He turned from her and went off with his head down, something like a guilty small boy. The chorus of the frogs cried: Boo! after him. He was glad when he was over the next rise of land and the derisive choral was gone from his ears.

THE rest of that night Kildare turned in his bed restlessly. Sometimes he lay still, thinking out a new set of speeches with which he could break the news of his departure gently, but when he got up in the morning and dressed, he heard a thin-bladed hoe chiming in the vegetable garden and went out to find the old doctor already at work along the onion rows. His overalls, supported by sweat-stained braces, had fitted him snugly in days which Kildare could remember but now they flared out loosely around the hips. The flesh had dwindled from his neck. Only two lean fingers of muscle, under the brown of the skin, tried to support that big head.

He stood up and rested on the hoe-handle.

"You're up early, Jimmy," he said. "But you add a lot to this landscape of mine. Even that mare over yonder seems to be waiting for you. Maybe she's heard Beatrice talking so much that she knows you by reputation."

Kildare put up his hand to a pain in his throat. He wanted to find the subtle, the frictionless way of getting at this business, but he had been unable to think of anything. He was not rich in the artifices of tact. He had quiet ways, but in the ultimate pinch he usually wound up by jumping at the throat of his affairs and then hanging on.

He said: "Father, I came out to say something that I hardly can get past my teeth. I know you've counted on me here but I can't stay."

"You can't stay—here?" repeated his father, wondering.

"I've got to get to a big hospital. There's a chance to place in the Dupont General in New York and I'm going there for my interneship."

"You don't tell me!" said the old man. He looked quickly past Kildare into the distance.

"It's like this," explained Kildare, sweating. "The Dartford hospital is fine. Everything would be great over there. All the people would be kind to me for your sake. But—I simply have to get into a bigger place."

"Do you, Jimmy?" asked the old doctor. "Well, well—I thought you hadn't fastened on anything in particular—medicine or surgery or research—I thought just a general kind of a training—"

"I have to see them in thousands—I have to watch them pass through in thousands—a hundred faces of every disease you can shake a stick at—I've got to—"

When emotion choked him off, his father said: "Sounds kinds of wholesale, doesn't it? Maybe we are just a little retail out here in Dartford... You know, Jimmy, if living at home would cramp your style a bit, I could arrange—"

"Oh, God, no!" cried Kildare. "It isn't that. There's no place in the world I want to live except right here!"

"So—so—so," said the doctor, speaking as though to quiet a nervous horse. The hoe on which he leaned wobbled a little and the hands which gripped it were hard-clenched. "It won't be very good news for your mother, I'm afraid."

"I'm sorry," said Kildare, and hated himself for finding no more eloquent words. "I'll go tell her now," he added.

He had turned away, anxious to have that face of controlled grief behind him, when his father said: "Just a minute, Jimmy. Perhaps, after all, it would be a little better if I told her."

Kildare stood still and watched his father go by him. His heart was beating so that the whole landscape trembled. He walked over the pasture fence where Maggie, the bright bay mare, was watching him with a mischievous interest. When he came closer she grew alert for flight but stretched out her head to make a final, sniffing inquiry. Kildare gave her the back of his hand and with prehensile upper lip she began to try to grapple it. She was as mischievous as a kitten; for how could she be aware of human misery? But she pricked her ears and tossed her head when a woman's voice cried out from the house, sharp and small with pain.

Kildare grabbed the top rail of the fence and held hard to it for a long moment. He had expected a difficult time but this was beyond expectation, like the difference between war in newspaper headlines and war in the bleeding field.

After a while he went over to the Raymond house and rang the front doorbell. Mrs. Raymond opened for him. She had given her height and her dignity of carriage to her daughter but she was as cold as Beatrice was warm. Her husband died ten years before and now at forty she was accustomed to the premature winter of her widowhood. She said: "Good morning, James. Come in."

He stood in the front parlour, where footsteps and voices were muffled by red carpet and plush curtains. The great brass andirons watched him with sparkling eyes. In the dead room they alone were fully alive. It was the most imposing room in Dartford and here middle-class respectability was permanently on view like a body in a state coffin. Awe inherited from the years of his boyhood descended upon Kildare again.

"May I see Beatrice?" he asked.

"Beatrice was out late," said Mrs. Raymond. She paused. In the pause her glance coldly accused him of knowing only too well why Beatrice had been out so criminally late. "She is sound asleep now."

"I wish I could see her," said Kildare.

Mrs. Raymond started to make one of her more frigid replies, because she prided herself on being able to keep the proper distances in her little world, but a closer look at the set face of Kildare changed her mind.

She murmured something and went hurrying up the stairs. Kildare heard the knock at the door. After a while the voice of Mrs. Raymond exclaimed with muffled horror: "You can't go down like that. Beatrice, what are you thinking of?"

"Of Jimmy," the girl answered, and her footfalls came down the stairs in a soft hurry with a windy whispering of clothes. She appeared to Kildare in a dressing-gown of green silk with figurings of yellow and dull red. Her hair was tousled. She had to stop in the doorway to pull on a slipper which was half off her foot. Then she came on to him, walking more slowly, examining him from a nearer and a nearer distance.

"You did it," she said quietly, "and now you can't take it. I know—Was it simply dreadful?—Sit down over here. Don't say anything. Talking won't help—"

He took her in his arms. He put his face down against her hair and closed his eyes. Yet even with his eyes closed he could feel Mrs. Raymond stepping into the open doorway—and out of view again.

"I don't know what there is about you, but you take the ache out of things."

He sat down on the couch and dropped his face into his hands. Beatrice sat close beside him. A touch or a word would have been unendurable but she did not speak, and he could see her slim hands resting in her lap, tied into a painful knot.

"You know everything. You're never wrong. You're always perfect," said Kildare.

She said nothing. She was simply there, filling all space so that grief and evil could not come near him.

"I've had a beating and I've come here to whine. Do you mind?" he asked.

"It's lovely to be usable, and to be used," she answered.

"I told him and he just took it," said Kildare. "After a while he said that if it was the thought of living at home that cramped my style—"

"Poor Jimmy! Poor Jimmy!" she said.

"He went in and told mother; and I heard her cry out—the way a woman does when—the way a woman cries when she can't stand it. Just one breath, and then nothing. Ah, my God! Don't comfort me. Maybe I'm a rat."

"You're either the worst rat in the world or else you're just our old Jimmy grown up," said the girl.

The words shocked him out of his sorrow a little. He lifted his head and looked wildly at the future.

"Suppose I go down there and don't do anything big?" he whispered. "I've broken their hearts and I've hurt you. Suppose after all I don't do anything big!"

"Don't worry about me. I think I like it."

"Like it?" he repeated, amazed.

"Yes, like it. The kind of pain that your sort of man gives me."

"What do you mean?" he asked again.

"I don't know," said Beatrice. "But if you stopped to think and ask yourself where you were going, you'd never get anywhere."

"I suppose that means something," he answered. "If only God would let me know exactly what I want to do—medicine, surgery, or what. It's like knowing that you have to spend your life working on pictures. Like knowing that you can't live without 'em, but not having the foggiest idea whether you want to etch or draw or use a camera or do pastels or try to whack out the big stuff in oils. But I've got to be there in crowds—crowds of the sick—I don't know what I'll do to them, but I've got to have them around, under my eyes, thousands of them. Does it sound crazy to you?"

She made one of those thoughtful pauses. He waited, growing more breathless because her final judgment seemed so important.

"No, it's not crazy. It's just like you, that's all," she said. "I don't know why it's like you but it is."

The voice of Dr. Lawrence Kildare sounded in the front hall, speaking with Mrs. Raymond. Now he came into the room saying: "What's the matter with that boy of mine? Won't he let you have your sleep out, Beatrice?... Here's a telegram that just came for you, Jimmy."

Kildare looked into the steady old eyes for a long moment, making fierce inward resolutions. Then he tore the telegram open. When he had read it, he let it fall. He had the look of one before whom doors are opening rapidly, showing the way through great new halls of light. It was plain that for the moment he had forgotten everyone in the room.

Beatrice, without asking permission, picked up the paper and read aloud, softly:

FOLLOWING YOUR SUGGESTIONS FOUND SPIROCHETE MADE INJECTION IMMEDIATELY TEMPERATURE NOW BROKEN TO NORMAL CONGRATULATIONS AND MANY THANKS — JOHN CUTLER

"Who was the sick person, Jimmy?" asked the girl.

"Somebody you were terribly fond of?"

"Fond of?" echoed Kildare, impatiently. "I don't even know his name!"

DR. CAREW, medical director of the Dupont General Hospital, did not wear false teeth because without them he looked like Cicero. He had the same bald dome and the same downward-sagging lines; he had the same general air of the wise bull about to bite. He added to the effect by earmarking himself as a man of culture; that is to say, he damned modern books, architecture, painting, music and in general the direction of our intellectual course. In the hospital he was considered a 'character', a reputation which is sure to give a man more leeway than is good for his soul. Now he was talking to the entering group of internes in his large office, leaning forward on his desk.

He said: "We still are waiting for Dr. Gillespie, who takes an interest in the entering groups of internes. He prefers to be present when they are inducted into the service of the hospital. Gillespie is our internist. But you all know about him. He is a legend though he is still alive. Before he dies, he hopes to discover some young brain sufficiently intelligent to receive the heaped-up stores of wisdom which a great diagnostician has gathered in the course of a long life. During twenty-five years he has searched for such a man."

Carew, paused, joined the tips of his fingers together, and contemplated this gesture, which might have been one of prayer.

"Perhaps," he said, gently, "Gillespie will achieve his quest today; perhaps he will find his man among you."

The hope which Carew expressed in this manner was denied by the faint smile which pulled his mouth to one side.

"Ah," he added, looking up, "and here is Gillespie in person. Hurrying, as usual."

Here a door was cast open and Gillespie entered. A thousand tales of the famous diagnostician, a thousand whispering murmurs that travelled through the medical world, had prepared Kildare for his first sight of the eccentric, but still there was a shock. He worked twenty-four hours a day so that it often was said that he never was quite in bed and never was entirely out of it; that is to say, he always was preparing for the good, long sleep which he needed so much and which never came to him. On this occasion he must have been actually in bed and he had dressed in three gestures to keep this important appointment.

He was wearing a grey flannel coat with the collar turned up to conceal the nightgown beneath. The skirt of the gown, too casually poked inside his trousers, escaped to the rear and hung down under the tail of the coat almost to his knees. In place of shoes, he had stepped into carpet-slippers with elastic sides and rubber-padded soles. He had a huge dome of a skull with a windy mist of white hair on top of it and scraggy, scrawny features descending from the immensity of the brow. He was not a very clean antiquity. The grey stubble of two days' beard covered his face. A bit of yellow egg-yolk was streaked in one of the wrinkles near his mouth.

He said: "Good morning, everyone. That damned Conover didn't wake me up in time, and then he wouldn't let me come till I'd had some breakfast... What have you got here, Walter?"

"A number of learned young men," said the dry voice of Carew, "and the man you want is surely among them."

"I doubt it," answered Gillespie. "But go on, go on! Carry on, Carew, and speak your piece."

Carew said: "Young gentlemen, to tell you all that is in my mind would require time and time is the one commodity which this century cannot produce. Besides, I would rather be brief and remembered than discursive and forgotten. I take it that most of you come from institutions of culture, that Horace remains on the back of your tongues like the taste of his own Falernian, that Phidias fills your eyes and Bach your ears. Since all these things are true, or should be true, it hardly is necessary to remind you that discipline is needed chiefly by barbarians and therefore that you will be accorded from the first the liberty proper for free-born citizens of the world of the mind. However, in a hospital of this size there must be rules. To gentlemen of your capacity, worthy of being masters of your own days, these rules will be only the slightest encumbrance but if there should be one or two among you—which I doubt—who expect like children to saunter through the year in this hospital, if there by any chance should be one among you who does not love duty for its own sake, to him and to him alone I say that the Dupont Hospital treats every man as well as it can but as harshly as it must.

"In the meantime, in the highest hope and expectation that the hospital will be worthy of you and that you will be worthy of the hospital, I extend to you my personal greetings. Dr. Gillespie, have you anything to say?"

During this rhythmical incantation, Gillespie had shown the greatest impatience. He walked up and down the room, looking out the window at one moment, then scanning the internes, staring at the ceiling, or putting his hands behind his back to flop up and down the double tails of coat and nightgown like the wing- sheaths, black and white, of a beetle. Attracted by one of the internes, he went over to him, felt his shoulder-muscle, and then craned his neck around to peer into his face. Whatever he looked for he did not find and shook his head in manifest disappointment. Carew greeted three silent interruptions with some black looks but stuck to his lines like a good actor. When he was asked to speak, Gillespie was sitting at the side of the desk, using his thumbnails to clean the other nails of his hands.

"After you've put 'em to sleep with your prologue, how the devil can I wake 'em up, Walter?" asked Gillespie. "However, come here, my boys!"

The internes made a diffident movement towards him. He slapped his hands palm down on the desk, saying: "What do you see in my hands? Come, now—look! Take hold of 'em. Turn 'em over. Look with your eyes and look with your brains and tell me what's in 'em."

The internes hardly dared to touch the hands of greatness, but they crowded their heads together, staring at the withered old paws. Big, blue veins wandered loosely under the skin.

"There's a touch of eczema here, sir," said one.

"Bah!" exclaimed Gillespie.

"Slightly clubbed tips—that's a sign of pulmonary trouble at some time or other, isn't it, sir?" asked another.

"Rot!" said Gillespie.

Kildare picked up the left hand and looked earnestly at a slight discoloration partly under the nail of the little finger and partly at the edge of the nail, like a small mole.

"May I feel the epitrochlear gland, sir?" asked Kildare, reaching for Gillespie's left elbow.

The diagnostician jumped up and banged a fist on the desk. "What the devil do you mean, young man?" he demanded. "What are you? What's your name?"

"Kildare," he answered, with his eyes still on the left hand of the internist.

"Kildare—Kildare—an Irish name," said Gillespie. "The Irish are a useful lot on horseback. Maybe that's your talent, Kildare. Horses, horses!"

And he strode suddenly out of the office. Broad grins, malicious eyes, turned upon Kildare.

"Perhaps the rest of you feel a little grateful," commented the dry voice of Carew. "The lightning rod has saved the house, I think—and perhaps Mr. Kildare will be less curious about elbows from now on. Your rooms have been assigned. You may go to them." He added: "Dr. Kildare will kindly remain a moment behind the others."

The internes filed from the room. Their laughter began when they were hardly outside the door. When they were gone, Carew stood up and made a half gesture towards Kildare with a pale hand. Kildare took the hand gingerly in his own and dropped it at once. Carew said: "My old schoolmate, your father, has written to me about you. I remember Lawrence Kildare as a happy nature but a casual mind. I trust that time has remedied the defect. As for you, I shall give you more than your share of my personal attention and trust that it may benefit you. I trust that Gillespie's reaction may not be that of the hospital staff at large. Good day."

Kildare went down to the office to find out his room assignment. Since he knew none of the other internes, he had not even attempted to write down a preference as to a roommate. He discovered that his bags already had been sent up to Room 114, so he followed them through the clean shimmer of the halls. The hospital was so big that it never was silent. From passing subway trains or huge trucks in the street or perhaps cellar machinery, a slight tremor lived continually through the building. Footsteps never were done hurrying. Voices opened and were shut away behind doors. Life was so housed in enormous space in that great institution that these sounds gathered into the consciousness of Kildare no more loudly than the humming of a bee, a sleeping noise on a warm summer's day. It was not a place in the world; it was a world in itself.

When he came to 114 he found a naked room with white walls and two iron single beds, two small desks, two narrow bookcases, a double washstand. His bags stood beside one of the beds. An adjoining door stood open, with voices pouring cheerfully through it.

He could not help hearing a fellow with a loud bass exclaiming: "If you catch a cluck, we're going to lock that door, Tommy, and close you in with him. You've got to get somebody human for a roommate or be damned if you can share our terrain."

Kildare went to the open door and looked in on three young men in the midst of unpacking.

"It seems that I'm what Tom has caught," he said, in his grave way, "and I hope I'm human enough. My name is James Kildare."

They stood up and shook hands with him. Stanley Vickery, Dick Joiner, and Tom Collins.

"If you like that long drink, you'll like Tom," declared Vickery. "And maybe you need a drink since Gillespie dropped on you like a hawk, but think of God joining two names like that together and expecting a man to live up to them all by himself? Where's that questionnaire, Tommy?"

This Vickery was a blond giant with a downright, battering, football look about him. His roommate, Dick Joiner, smiling and pudgy, did not look up to much unless that bulging flesh were muscle instead of fat. Tom Collins, to make the three as unlike as possible, was a dark-faced, long, light cat of a man. When the questionnaire was mentioned, he at once pulled out a long sheet of paper.

"This is a short cut to knowing one another," he explained. "School and college and medical school first, please. Joiner and Vickery are from Groton and Harvard; I'm only from Andover and Yale, so they won't let me stay in the same room with them; but we can keep the door ajar and get some of the air from the high life, now and then."

"I went to grammar school and high school in Dartford; then to Hillsdale for college and the medical course."

"Hillsdale?" murmured Collins. "Well—next question—what musical instrument? Vickery fiddles, Dick bangs the piano, and I, brother, can handle the drums—if you could do things with a saxophone, for instance, or an accordion, or anything at all—?"

"Sorry," said Kildare.

"Nothing?" pleaded Collins.

"Nothing," answered Kildare.

"Games are next. Where do you stand on that? Golf, tennis, ping pong, or what? Vickery used to smash himself to pieces trying to get through that Big Blue football line; now he makes a fool of himself at squash rackets. Joiner was a roving centre and a stumble-burn all over the lot. When he stumbled against Yale he got that vacant look that never leaves him. Now he does golf and tennis. As for me, I swing it, Kildare. What's in the blood has to come out—"

"I box a little," said Kildare, "and tennis makes a good quick workout."

"Tennis—workout," said Collins, frowning at the paper as he wrote the answers down. "What do you drink? Wine, whisky, gin, or beer? Dick sops up the beer and see what it's doing to him; Stan loves the Black Label; and it's the giggle-water for me, old son."

"I have beer—now and then," said Kildare.

An odd little silence had settled over the room. "Now and then," murmured Collins, as he wrote down the words. "Now we get down to indoor talents. Can you make that seven come eleven, or does contract suit you, or poker, or do you ride the time away with stud, now and then."

"I haven't enough money to gamble," answered Kildare.

"You couldn't make a fourth at anything?" sighed Collins.

"I used to play cribbage with my mother," said Kildare. "That's all I know about cards. I don't go in for them much."

"Doesn't go in for them—much," wrote Collins.

Kildare could feel in the air a crossing of glances and the silence crept out from the corners of the room like a cold shadow.

"I'll be getting at the unpacking," he said. He looked at them one by one, with a deliberation which was peculiarly his own. He knew in his very bones that they were the best; they were what he wanted. He hadn't known people like this at Hillsdale because Hillsdale did not have them; and there was an upward bounding of his heart as it came over him that perhaps here was a mighty, quadrangular friendship which might endure through all their lives. But all he could say was: "I'm glad I've met you." Then he went back into his room.

The packing occupied him. The books he had with him more than filled his bookcase, but he made room on the top shelf for the double picture frame which held the photographs of his mother and father. He could hear low murmurs of voices from the three in the adjoining room; after a time Tom Collins came into the room, stepping quietly, his face dark, and just after he entered the door between the two rooms closed. It was done with care but Kildare distinctly heard the key turn and the bolt sliding in the lock. It was a shock to him. That hope of the great friendship vanished. It was as though that were a prison gate locking, and he on the prison side.

Collins, still silent, adjusted the dials of a radio in a corner of the room and presently the voice of a crooner was wailing rhythmically in the air. Kildare would not have protested for thousands of dollars but out of his impatience a faint sweat began to gather on his forehead and his upper lip. He had found in Hillsdale only one blessing: silence.

DURING the first week they were distributed to fit into the various needs of the hospital. Kildare was assigned to an ambulance in the emergency service. A resident physician took him out into the ambulance court one evening and introduced him to the driver and attendant who would ride with him on calls. The resident was a brisk young man who was growing a professional moustache. He said: "Here's your army. These fellows will do what you tell them. If this is your first shot at this business, let me tell you right now is the time to begin giving orders and never ask for advice. We have three pairs of hands with every ambulance but never more than one set of brains."

The driver and attendant regarded the resident with an eloquent blankness of eye. Both of them were men in the upper thirties but Kildare knew what the resident meant: Superior knowledge gives and demands the authority to command. Kildare lingered after the resident went inside again. The streamlined length of the ambulance, before the week ended, would enclose a part of his destiny the way a steel shell encloses a blasting charge. The attendant stood by, grinning. He was a pink-faced man with the neck and shoulders of an athlete and the loose good nature of a child in his face.

"You look as though you'd been in the army—you stand that way," said Kildare.

"Marines," said a woman's voice beside them. "The infantry pulls the chin in; the marines, they stick it out."

"Lay off that, Sally," protested the attendant.

"Sergeant Jeff Weyman. Sergeant Beans. That's what they used to call him. That's how tough he was," continued Sally.

"Go on and scram on out of this, will you?" asked Weyman.

"I'm going to scram," agreed Sally. "He's a good boy now," she told Kildare, keeping her ironical eye fixed on Weyman as she spoke. "We've agreed that I'm to scram and keep on scramming if he can't hang on to this job. But he still thinks that he's in the marines and that everybody else is gobs for him to beat up when he wants action. So long, Beans."

She went away, leaving the rainy dimness of the court still darker; for she took away something with her, as a pretty girl always does.

"Long time?" asked Kildare.

"Two—three years," said Weyman. "She's kind of sour."

He tried to smile but his anxious eye still was following her through the rain.

"She's pretty," commented Kildare.

"Yeah, but she's got me in the doghouse," said Weyman. "She's sour. So I gotta hang on to this job..."

They got their first call within an hour. Weyman went inside the ambulance. Kildare got up on the driver's seat. They were doing fifty by the time they pulled out of the long curve of the entrance drive and the siren cut loose as they swung into the city traffic. The rain came down in gusts and blind, thick volleys, like the spray blown by a storm off the face of a heavy sea. The traffic huddled in tangles and jams, bewildered under this downpour, but the scream of the siren kept reaching out an invisible hand which opened their way. The streets, brightly polished, were as treacherous as greased metal but the driver took an Irish delight in this danger.

A saloon was their point of call. A dozen men stood down the line of the bar listening to a radio crooner while they drank. The bartender came around the corner of the bar to show the stretcher-bearers the way. Stretched in a corner with a towel under his head lay a middle-aged man with a white bloat of a face. A policeman sat beside him.

"One of these brittle guys," said the bartender. "He takes a couple of shots and goes out like a light."

"He oughta go to the can with the other drunks," observed the policeman, "but he's got this little cut bleeding here behind the ear so I couldn't book him." Kildare kneeled and peered at the cut. The blood leaked out slowly. The drops distilled one by one. He felt for the pulse.

"Booze, isn't it?" asked the cop.

"Or heart," said Kildare. "Heart or whisky."

"But why ain't there much of a breath to him?" demanded the cop.

"Because he's hardly breathing," answered Kildare, and they got the senseless body into the ambulance.

The bartender came out to them with word that the hospital had called ordering the ambulance to stop for an injured man on the way back. Kildare, inside the ambulance with his stethoscope over the heart of the patient, listening to the wavering uncertainty of the pulsation, shook his head. Weyman said: "He's only one more that's out with booze. Sometimes we gotta cord 'em up like wood, they come in so fast."

"Can you give oxygen?" asked Kildare. "Do you know how to adjust the face-mask?"

"Yeah, sure I know," said Weyman.

"Let this fellow have oxygen, then. I don't like that heart," said Kildare as the ambulance stopped.

It was only three blocks from the saloon, a high, narrow old rooming house. Kildare and the driver carried up the stretcher. A coloured maid opened the door to them. She led them into a front parlour where a scented punk burned in a little vase. On the floor lay a youth with a deep, raw-edged cut across his head. A red-stained towel was folded under his head, and beside him sat a high-chested woman in an evening gown. She had a neck thick enough to bear a yoke, and from her lobeless ears dangled a pair of large ornaments. She sat in a rocking chair and wielded a big fan. With each sway of the chair she gave the air a stroke of the fan, keeping a perfect rhythm.

"It's one of those places, eh," murmured the driver. "One of what places?" asked Kildare.

"Ah, you know what I mean," said the driver, smiling. "Minnie, get the gentlemen a drink," called the lady of the house. "What the devil are you thinking about?" The coloured maid disappeared.

"Can you get this lug out of here before he dies on me?" asked madame. "He's calling on a niece of mine and he takes a nose-dive downstairs because he can't handle his booze—"

"Did anybody give him a head start?" asked Kildare, examining a bump behind the ear of the injured man.

"What kind of a head start?" asked madame, leaning from her chair, with an effort that made her wheeze.

"He was hit from behind," answered Kildare.

"Should a guy start a fight he can't finish?" demanded madame.

"Get the stretcher ready," directed Kildare to the attendant.

The telephone rang and madame picked it out of its cradle on the table beside her. "Hello—hello—yes—yes, it's here—it's for you, doctor."

Kildare took the telephone. A sharp, barking voice over the wire said: "Dr. Kildare? Pick up 111 Lester Street, right around the corner from you. Woman. Suicide. Gas."

Kildare swabbed the skull-wound with iodine and made a swift bandage. The victim began to groan, making a feeble gesture of protest with one hand. Kildare looked up the nostrils and into the ears with his pocket light. There was a slight coagulation of blood in the right nostril. He lifted the eyelids. The right pupil was enlarged. The pulse ticked away rapidly, between 120 and 130.

"This may be serious," said Kildare. "I think it's a fracture."

"Wouldn't you know it?" groaned madame. "A blackjack never was any good. Sandbags are the stuff. But listen, doc—you know what they would have done with that thug in most houses."

"They would have rolled him out in the street," answered Kildare.

"I wouldn't do that, I never do it," remarked madame. "So give me a break, will you?"

"Everything I can," said Kildare. He picked up the head of the stretcher.

They rushed the senseless man down the stairs and into the ambulance. The rain came crash as they reached the sidewalk. It turned the street dim and brightened the pavement with the trampling of a million tiny feet. Water-dust flew up to the second stories.

Weyman, whistling blithely, was in the act of adjusting the face-mask for the oxygen as they pushed the second stretcher into the ambulance. Kildare looked into the grey face of the first patient and caught Weyman by the wrist, hard.

"I told you to get that oxygen to him fast. What have you been doing?" he demanded.

"Take it easy, doc," answered Weyman. "These mugs, they get a load but they can carry it."

Kildare, feeling for the disappearing pulse, said: "How far away is Lester Street?"

"Around the corner," answered the driver.

"Drop me off there and then get this man to the hospital, fast. It's coronary, I think. Tell them that. And this is a fractured skull. The next time I tell you to do something, you're going to do it, Weyman!"

"Don't get tough with me, brother," snapped Weyman. "I don't take loose chewing from any of you—"

"Hand me the oxygen flask."

A moment later the ambulance had stopped. He lingered for a single breath as the oxygen reached the sick man; there was only a feeble rallying of the pulse. "Get him back to the hospital and then work fast and soft with him. Don't throw him around," directed Kildare. "You were too slow with him, Weyman."

"The hell you say," answered Weyman, glaring with fighting eyes.

Kildare met the glance for a brief instant; but dignity was never a thing that he was willing to fight for. "Get these two to the hospital and hurry back for me," he said.

He climbed down to the sidewalk and through the vague smother of the rain faced 111 Lester Street. It was built of rough bricks which gave it an unfinished look, like a face from which the skin has been flayed. Kildare looked at it through the downrushing of the storm and remembered some of the dingy railway stations which he had left behind on trains. In just such a place as this reputations are left behind, particularly very intangible stuff like the good repute of a young doctor.

He was ringing the front doorbell. The echo of it ran far back and walked up lonely stairs. The door opened. In the hall stood a man with a half-finished glass of beer in his hand. "Third floor up," he said. "She's cooked."

"Is she dead?" asked Kildare.

"As a herring," said the man.

Kildare trotted up the stairs. Two or three doors opened and people looked at him. Somebody said: "They oughta get the stink of the gas out of the house. It ain't healthy."

Then he came to the third floor. Three or four lodgers were loitering around a doorway. A woman with a man's squared face was in command inside the room, a greasy-grey face, with grey hair clotted across the forehead.

"Get her out of here, will you, doc?" she asked. "It gives a house a bad name to have a thing like this happen. The scuts—they come in off the street and dirty up a decent place."

Kildare stumbled over the strip of matting that lay by the bed with a rectangle of dust revealed beneath it. The window was open but the smell of gas still hung sweet and foul in the air. The rain, splattering from the window-sill, polished the floor with wet. From the iron bed one blanket, rat-eaten at the end, draggled down on to the floor; a sheet was pulled up over the figure of the suicide; only a fraying of blonde hair appeared beyond the upper edge.

"Don't be taking the sheet away with her," said the landlady.

Kildare drew the covering away. She was young; he saw the hands knotted into half-formed fists. Perhaps those fingers still clutched a bit of life. His intentness on the trail of that life half-blinded him. He got the muzzle of the stethoscope over the heart at once. Sounds from the outer world besieged him, the storm, the traffic noises, and worst of all the stirrings of the people in the room, confusing the trail like leaves which cover the sign of the beast from the hunter. Yet in spite of these noises through the tube of the stethoscope he detected a ghost of a fluttering sound, a vague pulsation.

He flung the stethoscope aside and lifted the girl from the bed—weight about a hundred and twenty, bones well covered, no sign of malnutrition, age perhaps twenty-two. He called out orders for warm blankets, hot water.

"Get what he wants," said the landlady to the excited roomers, "but he'll never bring her around. There ain't a flicker in her—"

Kildare had her stretched on the floor on her face, the left arm straight ahead, the right arm bent, her head lying over her right hand. He pushed a finger inside her mouth and pulled her tongue forward. The touch of her teeth made him think of the naked skull, all that flesh stripped away to the bare, blank essential. Her lips were soft and cold and dry, like cloth. He kneeled, putting his thumbs in the small of her back, his fingers spread out over the floating ribs. He began to swing his weight forward and back. He pulled out his watch and laid it on the floor beside him because of the frantic impulse to go faster and faster. Fifteen pressures a minute were enough. More than that might hurry and stifle the returning natural respiration.

"A lot of hoorah for what?" asked the landlady. "Suppose he brings her around, she'll blot herself out some other way. When they go nutty you can't do anything about it."

"Get down and wait for the ambulance," panted Kildare. "When it comes, tell Weyman to bring up the oxygen on the run—and give me a bit of cotton, somebody."

FOOTFALLS went banging down the stairs. Somebody put a can of cotton near by. He pulled out a wisp of it and laid it on the girl's arm near her lips. Then he resumed that rhythmical pressing, relaxing, pressing, swinging his body to give it force. Five minutes of the Schaefer Method and you know you've been doing something; fifteen minutes and you may be done in. However, he was not thinking about fatigue just now. He said: "Somebody help me?"

A girl with a colourless pigtail of blonde hair flopped down on her knees beside him. She was not more than ten. Her dirty hands were doubled into fists and her eyes glittered with eagerness.

"I'll help—leave me help," she begged.

"Watch that bit of cotton near her lips. Tell me when it stirs. Tell me when her breath stirs it."

"Maggie, get away from that thing!" called an angry woman.

Maggie stiffened straight up from her knees. "Shut up and leave me be!" she shouted.

Weyman was there with the oxygen a moment later and adjusted the face-mask.

Maggie was swaying back and forth, maintaining an unconscious imitation of Kildare. She breathed deeply, to inspire breathing in the suicide; her white face turned red. Once Kildare smiled at her and she twisted her lips in an effort to smile back. His arms were numb with effort. Hands kept fumbling about him as more blankets were swathed around the body on which he worked.

"Take my place here," Kildare directed Weyman. "It's the Schaefer Method. Understand?"

"Yeah, but she's out like a light," said Weyman, scowling as he took Kildare's position. "What's the use getting dirty hands for nothing?"

"Slower!" commanded Kildare. "Fifteen to the minute, and no faster. Put your back into it—"

He tried his stethoscope on her side but he could get nothing. He felt her body and found it still deathly cold. Her colour was very cyanotic. He opened his case, filled a syringe, and gave an injection of the respiratory stimulant, coramine. Her skin was gooseflesh, slightly rough to the touch. After that he looked up at the animal, curious faces which thronged the doorway. He could not endure the sight of them. Out in Dartford all the faces are kindly; it never rains in Dartford except softly, to nourish the earth; in Dartford the sun shines every day. He took off the mask. He pulled up her eyelids and one glance at the lifeless eyes was enough to take the heart out of him. He pinched the blue out of a fingernail, then studied the return of the colour. He pulled out her lower lip, pinched it white. Into the white ran a faint cherry red, a stain of life dimmer than the first pale breath of dawn in the sky.

"Get away from her," he said to Weyman. "I'll take her now."

"Leave me try, doc. I'm getting the swing of it. Leave me carry on," urged Weyman, staring with an odd hunger at the half- hidden face of the girl.

But Kildare brushed him aside and took his place. Perhaps one worker was as good as another, but he had a queer feeling that the necessary electric impulse could flow out of his hands alone. In the meantime, until natural respiration began, in spite of the blankets the outer cold was soaking gradually deeper and deeper into the body. Like water it might touch the ultimate spark and then all would be darkness for ever.

"Look! Look!" screamed Maggie. "It's moved! It's moved! She's breathing—"

She began to sob. She had her upper lip caught in her teeth so that no breath of hers might touch the tell-tale cotton and give a false sign of returning life.

"She's stopped again!" whispered Maggie.

"Is she your sister?" Kildare whispered to Maggie. "She's nobody's sister in this house; she's just a thing off the streets," said the landlady.

The blue pallor began to alter in the face of the suicide. Kildare, sitting back on his haunches, kept his hands lightly in place and felt the answering respiration begin, swell, fade away, and begin again. His eyes burned with the sweat that ran down into them. Maggie took a soiled handkerchief and mopped his face. "You won't let her die, will you?" she asked. "Look at how careful she's made. Look at how beautiful."

Kildare looked, but his concern was not with pretty details. Now that she was alive he knew that he had wanted to save her in order to learn what had caused this attempt on her life. Causes matter more than cures, whether of body or soul. Maggie caught his arm with both hands and, looking up at him, exploded: "You're good!" He could not find an answer. This adoring gratitude left him a trifle bewildered and ashamed.

He had the ambulance drive slowly so that he could maintain the artificial respiration all the way back to the hospital; he kept it up even as he walked beside the stretcher which took the girl into the emergency ward. By this time, the cyanotic colour had diminished and the natural tint was returning.

That was when her lips stirred. With head bowed close, he listened to a breath of words.

"—mon mestier et mon art—" she said.

A quick-step of excitement began in the ward. Four or five nurses appeared about the stretcher in a cluster. They held their heads on one side to peer more closely at this patient, and glanced at one another with a sort of furtive pleasure. They seemed both alarmed and delighted. Kildare had not the least idea why.

Their swift hands had her in a bed. They were bringing fresh, soft blankets to swathe her. The blanket which was nearest to her throat was deeply fringed with red, the danger flag which told everyone that this was a critical case. They were packing hot- water bags around her to prevent the deadly chill. Kildare, with one hand on her pulse, watched and counted the respirations. They were very shallow. Between each one he despaired of seeing the next begin; but gradually the pulse was touching his fingertips with a more assured pressure, though still uncertain and wavering, like the steps of a child that is learning to walk.

A man's voice, vaguely familiar, said: "Where's the beauty you're telling me about?"

"Shut up!" commanded Kildare, for at that moment the lips of the girl had moved, and he was leaning forward to catch the words. All he could hear was: "—et mon art—"

The same man's voice repeated: "This is the beauty, is it?"

"What beauty?" snapped Kildare. "Be still, will you?"

"Doctor!" gasped the nurse. "This is Dr. Gillespie!"

The name froze up Kildare's brain like an exquisitely subtle anaesthetic. He looked up and saw the great diagnostician wearing a face newly clean from the razor. A white coat shone on him.

The great Gillespie taking her pulse said: "She will live—she will live. But you're right, nurse. I never saw anything more lovely; nor anything stranger than a young doctor who had no eye to see what he was working on."

Kildare, rallying himself from his work like a man stepping out of darkness, looked at his patient again with eyes that saw her for the first time, and understood at last the excitement of the nurses over this patient. That straggle of blonde hair turned into red-gold out of a medieval ballad. It was not bobbed but flowed down after the fashion of older and wiser centuries around a perfect face. He remembered what Maggie had said. In fact she was 'made careful'. He forgot her again as he stared at the great Gillespie.

"I'm sorry, sir," he said.

"Sorry for what? Damn your sorrow," said Gillespie's organ bass of a voice. "Sorry you didn't have eyes to see her, or a heart to tell you by instinct what to look for? Don't tell me about it. Tell God that you're sorry he made you that way—I'll take care of this case, doctor—"

A nurse, looking at Kildare with curiously contemptuous eyes, remarked: "The reporters are waiting for you, Dr. Kildare."

"Kildare? Kildare? I remember the name," echoed Gillespie as Kildare went out of the ward. In this manner he was blacklisted by the finest brain in the hospital. For that matter, was there in the whole country, or even in the world, a greater diagnostician than this same Gillespie who had given up his life to medicine like a monk, rendering up his days to the service of heaven? This Gillespie, this text of illimitable knowledge, would be a closed book to him from now on. He had begun his interneship with a disaster.

As he came down the corridor he heard the voice of his ambulance driver saying: "This is the one. Kildare is his name."

He faced them, waiting.

The ambulance driver stood back and three brisk young men came up to Kildare, pulling notebooks out of their pockets. They were from The Messenger, The Globe, and the Associated Press.

"We want a few words with you about Kegelman," said one of them.

"Kegelman?" asked Kildare, bewildered.

"He doesn't know the name," said The Globe man.

Somebody laughed briefly, and the corridor pushed the sound from wall to wall, bandying it tirelessly about.

The ambulance driver, who stood back with a queer look of superior virtue, remarked: "That was the first guy we picked up."

As if that first laughter had been a signal for the inquisition, they gathered around him now, ready to pick the bones of his ignorance. Their voices were mockingly low- pitched.

"Yeah. The one that died," said the reporter from The Messenger.

"Dead?" repeated Kildare.

"You didn't know that either, eh?" they asked of him as they wrote in their books.

"Now, doctor," queried one, "is it true that after picking up this John Kegelman instead of returning to the hospital with him you made another call?"

"Yes," said Kildare.

"Where you picked up another accident case?"

"Yes," admitted Kildare.

"And from there you went on to make still a third call?"

"There was a telephone message from the hospital—" began Kildare.

"Was it at your discretion to answer or not answer that third call?" asked a reporter. "In other words, are you in command of that ambulance or not?"

The questioner's face was pallid as paper; very old, very cunning.

"In command of it—yes," agreed Kildare.

"So that it was at your own discretion that you made the third call?"

"That's true," said Kildare, "but—"

"I guess that's all we want, isn't it?" asked a reporter. "All right, Harry!"

A photo-flash spurted white along the corridor. "Thanks very much," one of the reporters was saying. They turned their backs on him.

He stood, a statue carved of exhaustion and agony, straight and perilously quiet. His eyes burned with a sickening question, and dreadful premonitions came surging to his heart. God, what next? What blunder had he done now?

"I don't know about you fellows," declared The Messenger, "but I'm going to spread this."

"Sure," agreed The Globe: "Human interest."

AN ambulance call sent Kildare away to resume his night's work but he saw Gillespie later on, during the dark hours of the next morning when he came off duty. He went to the emergency ward, first, to look at the attempted suicide. Her bloodless skin had a greenish-grey tint like certain kinds of jade; the cyanotic colouring remained only around the eyes and in one pale shadow beneath the lower lip. Now that he was instructed to look for beauty, he could see a wealth of it. Her head was of the Mediterranean type, the brow low and broad and the features worked with exquisite precision. Her pulse remained rapid and irregular but she seemed surely on the way to recovery. He had been certain enough of that, before; it was not this question which brought him back to stare at her.

A nurse came to stand by the bed, watching Kildare with a cold curiosity. "What do you think, doctor?" she asked.