RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

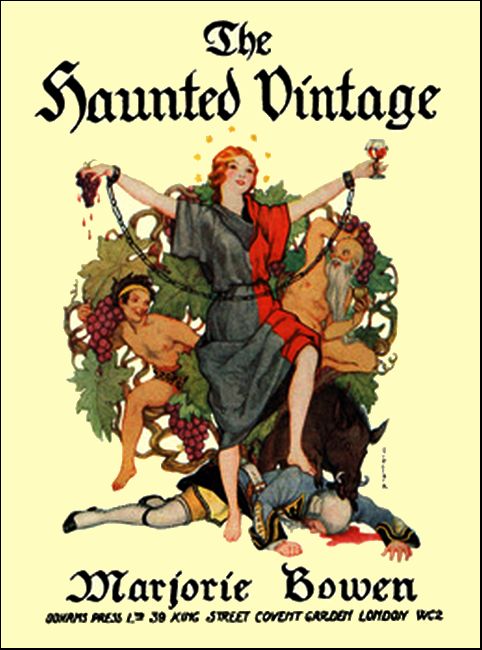

"The Haunted Vinstage," Odhams Press Limited, London, 1921

"The Haunted Vinstage," Odhams Press Limited, London, 1921

I SUDDENLY saw close before me, at the bottom of a most sequestered valley, the object of my journey, namely, the very ancient monastery of Eberbach.

The sylvan loveliness and the peaceful retirement of this spot I strongly feel that it is quite impossible to describe. Almost surrounded by hills, or, rather, mountains, clothed with forest trees, one does not expect to find at the bottom of such a valley an immense solitary building, which in size and magnificence not only corresponds with the bold features of the country, but seems worthy of a place in any of the largest capitals of Europe...Three or four of the monks of this once wealthy establishment are all that now remain in existence, and their abode has ever since been used partly as a government prison and partly as a public asylum for lunatics, the whole of which was admirably kept in complete subjection by a garrison of eight soldiers.

—"Bubbles from the Brunnen of Nassau."

THE new commandant of the prison and lunatic asylum of Eberbach took up the lamp and went to his door and listened.

It was his first night in the old monastery, and he could not rid himself of an intolerable sensation of strangeness. He had arrived when it was dark, after a ride of hours through the solitary forest, and he had no clear impression of his new place of abode; his mind retained but a confused picture of a huge building and vineyard and cathedral in the moonlit valley and an interior of great corridors, rambling rooms, dark stairs, Gothic windows, and great statues in unexpected places. He had not yet inspected the building, and he had given but a glance at the eight soldiers who formed his garrison. On his table lay the keys and a list of the prisoners and lunatics now under his charge.

He stood at the door, listening. He was certain that the utter silence had been broken by a distant wailing. He knew that he would have many strange sounds to hear while in his present employment, but to-night his senses were so alert and his nerves so taut, that he must listen to this cry and trace it to its origin.

It was not repeated.

The beams of the old-fashioned horn lamp cast long rays down the rough stone corridor, showed dimly one or two doors, then faded into utter darkness. Though it was full summer the air was damp, and yet not fresh.

The commandant felt a slight chill touch his flesh. He returned to his room and set the lamp on the high stone mantelpiece.

It was an extraordinary room—perhaps that which had belonged to the prior when Eberbach had been one of the most flourishing and magnificent monasteries in Germany. Two large, splendid mullioned windows had been curtained across by a length of coarse green cloth; the tessellated pavement, in worn shades of blue and red, was partly covered by a square of rough dark carpet; the walls, which had the hooks for tapestry, were rough and newly whitewashed; in one corner the shadows filled a hole which the commandant guessed had been once occupied by a holy statue. The chimney-piece was very finely carved in stone, with deep cut figures of beasts and fruit, and above was a picture set into the wall, and so smoke blackened that it was impossible to discern the subject. A soldier's bed with coarse blankets, a camp chair and table, a shelf with a common ewer and basin, and a few pegs, were the sole furnishings of the room.

"The Duke is economical," sneered the commandant.

His own handsome and numerous luggage, still strapped, was piled about the room and looked out of place in the grim chamber, as did the young officer himself, with his elegance and powder and spotless Nassau uniform. He seemed a strange choice for such a post, and as if he was conscious of this, and scornful both with those who had sent him to such a spot and himself for coming.

He sat on the one chair, absorbed in the pool of shadow that the high-placed lamp left untouched, with one hand to his chin and the other hanging down.

The silence was absolute. He was surprised not to hear the rustling of leaves; he had thought that the forest sloped down to the very doors of the old monastery; that had been the impression of the darkling ride. He was anxious for daylight, that he might explore this curious place; the novelty of it exhilarated him, despite his contempt of the whole affair, for he was used to a city and a court.

With a gentle movement his half-open door was pushed wide. Luy, the soldier who was to act as his body-servant, looked into the shadowed chamber.

"You are very soft footed," said the commandant, without moving, "and I thought that you were in bed."

"It is not as late as it seems, Herr Captain," replied the man respectfully. "And I thought your excellency wanted the valises unstrapped."

"If you like."

The commandant was eyeing the soldier with a kind of deep curiosity.

"Were you servant to my predecessor?" he asked.

"Yes, Herr Captain."

"What kind of a man was he? Like me?"

"Oh, no!" the fellow grinned, looking up from the straps he was undoing. "Like the Herr Sergeant."

"The right type for such a place," observed the commandant. "What do you think of me?" he added abruptly.

The soldier shut his lips. He was a small, lean type, with a shrewd, ugly, and remarkable face.

"Well?" urged the commandant, who still never moved from his careless, tired attitude.

"I have lived in Wiesbaden, Herr Captain," replied the man quietly. "I have been here only a few months."

"Yes?"

The fellow looked up, half impertinently. "I heard of your Excellency when I was in Wiesbaden."

"I suppose so. What do you know of me, eh?"

"I know—that you are Lally Duchene, Herr Graf."

The tone in which the man spoke—that of a strange cringing insolence—was new to the commandant; it interested him.

He looked through the shadows at the kneeling figure of the man who had also lived in Wiesbaden when that town had been his residence.

It was curious that they should come together with this intimacy. How often might not this man have watched his coach roll through the streets of Wiesbaden; how often had he not turned over his tongue fabulous, scandalous, wild stories of Lally Duchene, the foreigner, the Duke's friend?

"You never thought to see me here," remarked the commandant.

"Nor myself, Herr Graf," returned the soldier; then, with an underlining of his former touch of impertinence, "We are both of us unfortunate, Herr Graf."

The young captain laughed. "The fellow thinks of me as a fallen favourite," he thought. "He and his companions mouth over strange versions of my story; the dark heart of it they never guess."

Still in his lounging attitude, and with no change in voice or look, he yet put the other very decidedly in his place of inferior and servant.

"I think that your name is Luy. I shall call you that as you are to be my body-servant and it is the custom of this simple place. Perhaps you are used to the larger licence of a town; here, among the few of you, with such a responsibility, there must be a strict discipline and obedience."

"It has always been strict, Herr Graf," answered the soldier, now without that insolent inflexion.

"I was told that your sergeant had you well in hand."

The man opened the valises; curiosity showed in his handling of the clothes, few but fine—mantles of rich cloth, belts and boots of expensive leather, cravats and falls, ruffles and handkerchiefs of elaborate needlework, exquisite linen.

"You need not take all those things out," said Lally. "There is nowhere to put them."

"There are plenty of cupboards I could bring in to-morrow, Herr Graf."

"To-morrow we will see. Eberbach must be curious by daylight."

"Curious, indeed!" Luy was animated, eager, "It was a queer place to put criminals and lunatics, Herr Graf."

"Why, very proper," answered Lally Duchene, "since isolated in this great forest, they can have no hope of escape. To break away from Eberbach would be but to perish in the wood."

"Maybe, Herr Graf, but Eberbach is no fit dwelling, even for a madman."

"Too lonely, eh?"

"Haunted, Herr Graf, haunted!"

The commandant smiled; he had expected this. He knew the easy credulity of the vulgar, their gaping appetite for the marvellous, their fear of nature and their instant attribution to the supernatural of her unknown aspects.

"The wood frightens you," he said.

"It was a wild beast chose the spot, Herr Graf," replied Luy. "A little boar, who appeared to Saint Bernard and bid him build his monastery in this valley. You may see the grinning pig's face carved all over the building."

"That is a stupid, unromantical tale," remarked the commandant. "Are any of the monks yet in existence?"

"A few at Kiedrich, they say, Herr Graf, but I have never been so far. They must be old men, as it is twenty-two years since the bishop inherited the monastery—ten since it came to the Duke."

"Give me that paper I put aside with the keys," said Lally, "that I may be a little prepared for this inspection to-morrow."

When this was put into his hand lie bade Luy bring the lamp nearer, and, as the man held it, scanned the list of those unfortunates over whose existence he was now absolute master.

He found that he was in charge of two hundred and fifty prisoners and a hundred lunatics.

The paper, which had been prepared by the former commandant, very neatly showed the classes into which these were divided and sub-divided.

On the ground floor the men and women undergoing first sentences were separated in groups of various trades, such as weaving, tailoring, and carpentering, and worked under the direction of an overseer. These numbered about two hundred, the majority being men.

Above were the old offenders, or those convicted twice, in solitary confinement—forty-five men and five women.

In another and older part of the monastery were the lunatics, about sixty of whom were paupers and supported by the Nassau Government, the others being persons of means, whose superior maintenance was paid for by their families. These lived together in groups of eight or nine, an iron cage being provided in the corner of the room for any who might prove refractory, the more desperate cases being confined upstairs in solitary cells, and the most dangerous of all being isolated in a kind of summerhouse in the orchard.

There followed many details of the plan and management of the prison that was almost entirely self-supporting, and but rarely visited save by some curiosity-impelled traveller.

There was also a list of the names of all the prisoners, with their crimes and trades attached, and one of the lunatics, with an account of the violence and duration of their terrible disorder.

There was no doctor in the asylum save among the madmen, but the list stated that one might be procured at Kiedrich, distant half a day's ride through the forest.

Lally Duchene read no more. His mind wearied of all this dry detail, and shrank from the thought of the conscientious labours of his predecessor, who had toiled in Eberbach for seventeen years without recognition or change.

"Shall I be here seventeen years?" he wondered as he bade Luy set back the lamp.

The speculation was whimsical. He rose and looked with distaste at the camp bed. He noticed that Luy was eyeing him covertly, and curtly dismissed the fellow.

It did not please him to find this man from Wiesbaden in this solitude, where he had thought to be unknown and unnoticed.

Now, of course, everyone, even the prisoners, would talk over Lally Duchene.

What strange tales would they not mouth round between them; what wild reports and crazy surmises; what desperate imaginings would twine about his rise and his downfall! They would look upon him as no better than themselves, condemned to exile, imprisonment, shorn of his splendour in a disgrace only gilded by the clemency of the Duke.

Lally Duchene thought of all the curious eyes he would have to face on the morrow. He was used to curiosity, to envy, to dislike, to being marked out and pointed at, the butt of veiled malice and cowardly scorn; here he had looked for peace—forgetfulness, perhaps. He wondered if he could get this Luy changed. But the mischief was done; the man had certainly already spread the gossip of Wiesbaden through Eberbach.

He stood irresolute, tired, wishful of the oblivion of sleep, yet reluctant to stretch himself on the hard, strange bed and face perhaps frightful dreams, longings, and remorses.

After all, what did it matter if all of them knew all that Wiesbaden knew of him? No one was aware of the reality save the Duke and one other.

And they were his underlings, bound to obey and use a respectful demeanour; he had complete power over all—soldiers, prisoners, and lunatics.

The early summer night was chilly in this thick walled room. He walked up and down with an instinct to keep himself warm, then stopped abruptly, for the pacing gave him an impression that he, too, was a prisoner.

He went to the window and looked out into the fresh pure darkness. As he leant against the wide stone ledge he felt his heart beating strongly against the hand that gripped the sill.

WHEN Lally Duchene drew the rough curtains aside from his deep-set windows next morning it was with a large sense of change and freedom.

He did not feel like a man suddenly thrust into hopeless exile, but more as one swiftly liberated from a tiresome bondage, as if all that old splendid life in Wiesbaden had been a gorgeous captivity.

He wondered if all men violently and unceremoniously hurled from their high positions felt this sense of relief.

Yet how he had enjoyed that other life; striven for it, exulted in it, exploited to the full every minute of it!

No one could have ever relished success with more appetite than he, made a more magnificent use of power and opportunities. Looking back over the years in Wiesbaden, he could not blame himself for a single chance lost or misused.

And yet he felt, for the moment at least, neither regret nor repining. Perhaps it was the reaction after long strain, keen anxiety, deep agitation, and the shock of the final crash of all his fortunes.

He possessed, too, a whimsical humour which caused him to smile even at his own disasters; he had the cast of mind that sees the world as very small after all, and mankind as very insignificant.

He could visualise himself at Wiesbaden, a gay, eager, triumphant figure, climbing, climbing, then suddenly cast down; he could visualise the Duke, his friend, the keystone of his fortunes and then his bitter enemy, unchanging, omnipotent, worshipped in this small territory that was his, seemingly placed, in his steady radiance and his cool power, above any stroke of fate, yet, after all, in the final issue more smitten than Lally Duchene; he could visualise the woman, desirable and fatal, yet somehow featureless in the recollection—and smile at all three.

With his elbows on the window-ledge and his face in his hands, he looked out on the early morning.

His room was higher than he had thought it to be; he was amazed at the height of the building, at its size and magnificence.

The valley lay green beneath him, almost filled with orchards and a huge vineyard, and opposite began the outlying trees of the great forest that spread from the Mainz to the Rhine.

The isolation was complete; the nearest human dwellings were at Kiedrich, the other side of the forest, and impossible to find without a guide. Beyond this was the former residence of the bishops of Mainz, the Tower of Sharfenstein, now the property of the Baron von Ritter, a nobleman who was nearly always at Wiesbaden. Beyond this, several hours journeying brought one to the valley of Schlangenbad, one of the watering-places, tiny and remote, that served to swell the revenues of the Duke. On the other side the Rhinegau stretched to the river's edge, and was only inhabited by peasants absorbed in their daily toil.

Lally Duchene knew this; the position of Eberbach had been drily pointed out to him on the map of Nassau when the Duke had given those curt orders for him to take up this strange post; but the solitude that he now felt was not the solitude that he had imagined when in Wiesbaden.

There was a softness in the air, a radiance in the sky, a majesty and wonder in the fringes of the great wood, a strangeness and freshness in everything that forbade depression, at least to one of Lally Duchene's temperament.

He came from an Irish-French family. His great-grandfather had followed Patrick Sarsfield to France nearly a hundred years before; a Parisian heiress had given a foreign name to the exile; and the family—adventurers by disposition, need and necessity scattered all over Europe. Lally's father had settled in Nassau, buying property there with the proceeds of his early adventures in Canada, but he brought a French wife with him, and there was no drop of German blood in Lally, though he was a subject of the Duke and an officer in his army.

The father and mother had wandered away from Nassau and died in Paris, but Lally had founded his fortunes in Wiesbaden and on the deep friendship of the Duke, who was of the same age, though of so different a disposition. As Lally Duchene—count by a French, and marquis by a papal, patent, known as "Graf" in the Duchy where both titles were considered doubtful—surveyed the valley of Eberbach and the forest slopes opposite, he wondered if he had been wise to stay at the court of Wiesbaden; he was of a race and a tradition to have succeeded in larger fields. Well, there was time yet; he was only twenty-five.

He turned from the window and took up the list and keys from where Luy had put them last night beside the lamp.

Strange that he, in his downfall, should have complete power over these hundreds of human beings—outcast wretches no doubt, but still human beings. Standing in the generous sunshine that poured into the old chamber like a rush of sparkling wine cast into a stone cup, he glanced down the list of the prisoners' offences. Nearly all offences against the Duke—killing his game, cutting down his trees, carting away grass and leaves, breaking in some way his minute forest laws. There were no murderers, and but a few thieves. Those women who had not robbed the ducal preserves were marked with the one word, "dissolute."

"They are none of them criminals," thought Lally Duchene.

He had but little sense of discipline or law; had he been the Duke, Eberbach would have been empty.

But he had his ideas of soldierly honour, conventional enough—as long as he was in the Duke's service he would obey him; he might be trusted to rule Eberbach even though his heart would never be in the work.

It was possible, he thought, that the Duke had chosen Eberbach as his place of punishment that he might realise the power of the ruler of Nassau and how rigorously their petty offences against him were punished.

The Duke was but a German princeling, yet as absolute within the narrow limits of his territory as any sultan or shah. Lally thought him capable of wishing to remind the man he now hated of his despotic power. Lally, at least, reflected on this aspect of the matter.

As he studied the list he remembered that the Duke, if he wished, could put "Lally Duchene, self-styled count and marquis, and sometime captain in our armies," thereon for any offence he chose to invent.

The foreigner, whose family had never taken root in the Duchy, whose sole hold on any position had been the personal favour of the Duke, who had been envied and hated for his good luck, might safely be degraded, despoiled, and imprisoned without fear of a protest from anyone.

Lally thought over his relations and connections, numerous and loyal, but scattered and poor—soldiers of fortune, free lances or frank adventurers. None of them could help him. He saw his own position as entirely perilous; he was as much at the Duke's mercy as an insect held between a finger and thumb, unharmed as yet but unable to escape.

Since he held himself as the Duke's equal in everything, save the accident of position, this was a sore thought for his pride, but one that would not be lightly dismissed.

It accompanied him as, with his list and keys, the sergeant, and Luy, he went round his new domain. In Eberbach, at least, he was as absolute as the Duke of Nassau.

His first impression was of the cleanliness and freshness of the building. All the windows were open, the walls whitewashed, the woodwork scrubbed, and the air as fragrant as that of the valley without. He remarked on this to the sergeant, who replied that it was the greater part of the prisoners' punishment to be forced to this cleanliness, foreign enough to their nature and habits.

"Are they all, then, such low wretches?" asked Lally.

"They are criminals, Herr Graf, or they would not be here in Eberbach," replied the sergeant.

"One can take a handful of grass or a pile of leaves from a forest without being a criminal," remarked Lally. "Do you think it is so easy to remember when alone in a wilderness of trees that it belongs to the Duke?"

"It is not difficult to remember, Herr Graf," said the man stubbornly, "for everything in Nassau belongs to the Duke."

Lally saw a smile on the impudent face of Luy, and wondered if the words had been spoken with any meaning. The sergeant was a solid fellow, but there was no doubt that he had heard Luy's flamboyant tales.

Lally disliked the little red-eyed soldier more than ever. He was sorry that choice had fallen on so disagreeable a person to be his body-servant.

They descended the white stairs to the ground floor and proceeded down a long whitewashed passage, Luy, who carried the keys, unlocking every door as they came to it and stepping aside for the commandant to see his prisoners.

The partitions between the monks' cells had been taken down, so that four or five cubicles made one large room. In these chambers the prisoners, in groups of eight, worked under the direction of an overseer elected from among their number.

The first room accommodated the weavers, who were making rough cloth for the use of the establishment; the second carpenters, who were turning rude chairs; the third shoemakers, sitting crouched over their work; the fourth tailors, who were cutting and sewing the materials that their companions had made. They were all clean, sober, dull, and silent; very few of them even looked up as the door was opened. Besides these there were, the sergeant explained to Lally, a number employed in forestry and agriculture, besides the cleaning and repairing of the building, so that Eberbach was entirely self-supporting. It did not seem such an ill life to Lally. He had to admit to himself that, if the crimes were slight, so was the punishment.

"These people have no need to greatly dread a visit to Eberbach," he said.

"They dislike to leave their homes, Herr Graf," replied the sergeant.

Lally Duchene was silent; he had never had a home.

On the other side of the building he visited the women, passing first through some splendid cloisters which framed a fine herb garden and a beautiful stone well.

On the walls here hung four and twenty dark and stiff oil-paintings of monks, all exactly alike.

"Why do they keep them here?" asked the commandant.

The sergeant believed that it was because no one had troubled to give orders for their removal.

The women were found to be as soberly employed as the men in washing, sewing, basket-making, and knitting woollen garments. They sat close together, talking in whispers, and fell into an abashed silence when their new master looked in on them.

Women were also employed, said the sergeant, in the kitchens, and sometimes in the orchards or gardens.

Lally next visited the old refectory, which was now used as a school for the youngest offenders. He there found among the new benches a person whose humble existence had been hardly mentioned to him—the pastor.

A dull, colourless-looking individual, he was employed in imparting religious instruction and an elementary knowledge of arithmetic, reading, writing, singing, and weaving.

Lally exchanged a few words with this pastor, who said that he held a service here three times every Sunday.

"Why not in the cathedral?" asked Lally.

The Lutheran replied that that was too large, and used as a store-house for grain and hay.

Lally went his way with the artless singing of the imprisoned children in his ears. He inspected the kitchens, the stores, the stables; everywhere blanched floors, whitewashed boards, spotlessly clean people moving quietly about their appointed tasks.

"The Duke's arrangements are admirable," said Lally, with a hint of a sneer.

He entered the great cathedral attached to the monastery, and saw bundles of sticks and grass and chaff lying on the rich tombs of bishops and priors, some windows bright with painted glass, some plastered up with mud, parts filled with a rude wooden structure that served for a granary, parts open and bare to the now strong sunshine.

He would have visited the summer-house where the fiercest lunatics were confined, but the sergeant warned him that it was best not to disturb these; so he passed on to the other madmen, who seemed cheerful enough in their little groups, and only different from the other inhabitants of Eberbach by reason of their idleness. The review of those in solitary confinement was not so pleasant to Lally.

The melancholy, the ferocity, the gloomy laughter, and hideous aspect of these unfortunates were such as to make the young commandant glad when the last cell was locked again.

Nor was the visit to those criminals placed in solitary confinement much more relishable by a man like Lally Duchene. Deprived of the great solace of work, entirely cut off from all knowledge of the world, these wretches often spent three or even five years in these tiny cells.

The one privilege ever accorded them, as the result of persistent good behaviour, was the allotment of some task with which to occupy their gloomy leisure.

Thus the first cell that the sergeant opened showed a man at work on a coffin for a maniac who had just died, and in the second cell the occupant, with a kind of ferocious zest, was mending a pair of boots.

The others sat idle and listless in a corner in attitudes of absolute dejection, altered by an upward glance of peculiar anxiety when the door was opened.

The cells were clean, and each of the small windows was open on the fine air of the forest, while the prisoners all seemed in good health, but their expression was such as to make Lally Duchene wish that he did not have to look at them nor to catch the glance of bitter despondency with which they beheld the doors of their dungeon close.

The sergeant told him that the two last cells contained women, and Lally inwardly winced.

When the first of these was opened the prisoner sprang up with hysterical violence and hurried towards the door with such impetuosity that the sergeant slammed it forcibly in her face.

"She is the mother of little children," he said, as if in apology for her lack of fortitude, and proceeded to unlock the last cell. There stood before Lally in the full light of the little window a young girl whose countenance seemed to him lovely with gentleness and innocence.

She was the first of those in solitary confinement who did not raise desperate eyes; she stood looking down, her features convulsed with an expression of grief, as if she with difficulty refrained from bursting into tears. Her slight figure was leaning against the wall for support, her dark head pressed against the white-washed surface.

Her misery was so evident that Lally stepped back, and they locked the door.

"What is her crime?" asked the commandant.

The sergeant pointed to the board outside the entrance to the cell, on which was written the name and offence of the occupant.

Lally Duchene looked up and read: Gertrude Gerhardt, and underneath, in larger letters, the one word, Dissolute.

THAT afternoon Lally Duchene left the monastery and went out alone into the woods. His new post did not seem as yet very onerous. The establishment ran smoothly in its familiar grooves without any interference from him; both soldiers and prisoners were perfectly disciplined, and the daily life went on with uninterrupted monotony.

The new commandant could find nothing to alter, nothing to suggest; he looked on the strange little world about him more as a spectator than as a master. Presently, perhaps, he would find his place; now his office seemed a sinecure.

He was acutely conscious that his little garrison was aware of his story—the public version of it—and all faintly hostile, perhaps faintly contemptuous.

He was sure that both these feelings were more than faint in the mind of the Lutheran pastor, whose manner had been frigid and unfriendly.

A wonder whether, after all, he would find the life bearable, a reaction from last night's sense of relief and freedom, was checked by the exceeding loneliness of the scene through which he moved.

The sergeant had directed him to a spot from which a fine view of the river could be obtained, and to this he made his way, already filled with a dim desire to see a glimpse of the world from which he had been so rudely severed. It was a cloudless afternoon of bright sunshine which, filtering through innumerable leaves, made a pattern of radiant light and transparent shade in the grove of oaks through which Lally ascended the mountain-side.

The foliage, the grass, the flowers, had yet all the freshness of spring while expanding in the luxuriance of summer; the late violet, primrose, and cyclamen yet lingered in the thick damp mosses, and in the undergrowth that separated the far-apart trees were the white petals of the first wild roses and the tiny stars of the strawberry plant.

It was an enchanting period of the year, and Lally Duchene, who knew little of nature save in the autumn hunting season, was startled by the sheer loveliness of his surroundings.

The minute objects along his path attracted him by brilliant and persistent beauty—a cobweb in the shadow, which had saved it from destruction, the pearls of dew hanging on the almost invisible threads; the small, vivid cups of the mosses; the strong, moist blooms of the little curled away flowers, the purity, colour, and sheen of these, so different to any court bouquet; the young golden-red shoots round the boles of the giant oaks—all these things fascinated him with a deep delight as he slowly made his way up the hill-side, guided by notches cut by the woodmen on every third tree.

Without this help he would certainly never have found the track, so twisting and tortuous was the unpathed ascent to the top of the mountain that on this side shut in the valley of Eberbach. Presently the oaks, the undergrowth, the grass, moss, and flowers, gave way to a plantation of firs; between the straight red trunks was nothing save a thick carpet of needles and a few bright hardy plants vivid in the auburn shadows.

Lally found himself at the top of the hill.

His eyes, which had become accustomed to a close range and intimate objects, were startled by a sudden large and distant view of seemingly boundless extent, which instantly impressed him as the most marvellous prospect which he had ever beheld.

The view which thus flashed on him in the full dazzle of summer light was that of the Rhinegau blooming with vineyards, rice and cornfields, hop gardens, and orchards of plum, almond, and apples which had in some instances not wholly lost their blossoms. Beyond the river curved from Johannesburg to Mainz, the water one golden glitter, and again, beyond the farther bank, an immense fertile and lovely country faded into the soft blue of the distance.

There was no boat on the river, no dwelling-house in sight, but here and there might be discerned the figure of a peasant—the brown garb of a man or the white kerchief of a woman—bent low amid the crops or vines, the brilliant, fresh green of which showed already a few feet above the rich earth.

To Lally's quick mind this wide and gorgeous scene depicted the abundance and splendour of the world. The vineyards, the fruit-trees, the corn, the river, the women, the unbounded horizon and the dimly sensed cities just visible through the sun mists of the distance—was it not a vision of life, of all life could hope to contain? At least it symbolised all that Lally Duchene had ever endeavoured to achieve.

He sat down by one of the fir-trunks and took off his hat, and gazed deeply at the opulent prospect as one might drink strongly of heady wine.

In his youth and grace and ease of pose, in his air of eager vitality, he was no unfitting figure for the foreground of the picture at which he looked.

The Nassau uniform and buff belt set off a figure tall and strong; the dark hair, that showed reddish in a powerful light, was turned back, too thick, too stiffly curling, from a face characteristic of Latin blood in the dark complexion, short, high, arched nose, full lips, wide golden eyes, heavy sweeping brows, and the vivid expression of animation and keenness indicating senses alert and perfect and a disposition passionately amorous of life.

Combed and powdered, subdued and correct in Wiesbaden, he had not looked more notable than many another gentleman; here in the fir-grove, bathed in sunlight, he seemed both unusual and splendid.

It was not natural for him to remain long in a contemplative mood, and he soon rose and gave a last half-defiant glance at the entrancing prospect.

"Had I not been a fool," he said to himself, "I should not be outside all that."

After he had taken a few return steps through the belt of firs he saw beneath him what he might have seen during his ascent had he thought to give a backward glance—the valley of Eberbach, with the cathedral and monastery in the midst.

The view from which he had just turned away might be taken as symbolical of life's fullest fruition; this scene as surely represented seclusion from the world, negation of human instincts, and a complete loneliness; yet the view was, though in so wholly a different manner, of equal loveliness. Magnificent, large, and stately as a king's palace, the monastery, with colonnades, towers, and spires, orchards, gardens, fir plantations, and vineyard, showed as strangely in the empty valley as if it had been created by the stroke of an enchanter's wand.

So completely enclosed was the monastery, on one side by the hills, on the other by the forest; so lonely was the valley, untraced by any path or road, that no picture of more utter retirement from the world could well be imagined. The monks of St. Bernard who had wished to say farewell to life could not have better chosen the spot in which to pass their monotonous lives; here indeed, forgotten by all, they themselves might forget. Lally wondered if any of them had ever climbed to the brow of the hill and looked at the vineyards, with the women working among them; at the river and the distant towers of Mainz; or if they had for ever remained in the valley, without regret or longing.

So splendid, regal, and stately did this church and palace, which was fit to adorn a large city, look, that it seemed a sour irony that it should be used for confining criminals and lunatics.

Lally, descending through the oak-groves, could imagine himself one of the knight heroes of the wild old Rhine legends coming suddenly upon an enchanted castle where some beautiful woman was imprisoned.

He thought, not for the first time that day, of the girl: in solitary confinement. No fairy princess this, but a poor, degraded creature, shamed and punished; and he was the jailer.

Certainly he had misjudged her character from her face; she had seemed to him of a childlike innocence. Dissolute What did they mean by dissolute?

Lally paused, leaning against one of the oak-trees, and stared down at the noble building in the valley.

Dissolute—a word associated with cities, with a different type of woman, with women such as—

He checked his thoughts with a certain violence. If they meant what he thought they might mean by this ugly word, there was a certain lady might be, in other circumstances, placed beside this wretched girl—an amazing, a horrible, an unendurable reflection.

This Gertruda (he recalled that the name meant a witch) looked as if she was a peasant. He associated her with the great forest or with a little hidden village like Kiedrich, but it might be that she came from some town, and was indeed rooted and grown in ugly vices. He would like to have asked her history, but to show any interest in the one prisoner with charm and youth would, with his history, have been to too surely provoke a blaze of comment, a grin of meaning, in his watchful little garrison, in the dull pastor, in the sharp-eyed prisoners themselves. News of it would surely even reach the Duke—and that other woman in Wiesbaden.

He was not at all sure of Luy—by no means certain that he was not a spy—some creature of the Duke's sent to pry and note, report and sneak information of his doings into Wiesbaden. The Duke affected loftiness, a cold generosity, but Lally did not believe in this; he had no great credulity as to the virtues of mankind.

Slowly he descended towards Eberbach. The valley was in warm shadow, but the spires of the cathedral caught the golden light of heaven, which was refulgent with the deepening hue of the late afternoon.

The loneliness of the place suddenly smote Lally as with a physical pain. Was he to endure months, years, of this? Never seeing more of the world than might be glimpsed from the pine-grove at the top of the hill? Never to have any company but that of lunatics and prisoners?

He hastened through the fir plantations that surrounded the monastery, and turned into the great gate surmounted by colossal figures of St. John, the Virgin, and St. Bernard, mutilated but still bearing traces of their original brilliant colouring. As he paused to glance up at their majestic figures he was accosted by a man who rode rapidly up on a small donkey.

"Eh, Herr Captain, I have been waiting to make your acquaintance."

Lally looked at him with a leap of hope, followed by instant disappointment, for the fellow was commonplace, not young, shabby—no kindred spirit here.

"I am the doctor," he explained, rather disconcerted by Lally's patrician air—a little grandiloquent, a little sneering—which was neither understood nor liked in Nassau, and also stamped him at once as a foreigner.

"You live here?" asked the new commandant drily.

The little man explained that he came from Diedrich, and unless specially sent for rode over once a week. Monday was his day. This was a particular visit to make the acquaintance of the new governor of Eberbach.

"The place is very much understaffed," replied Lally indifferently. "There should be resident doctors, a secretary, a larger garrison."

The doctor protested.

"Eberbach is extraordinarily healthy, Herr Captain; it is surprising how little illness there is."

"Do any of your maniacs ever recover, Herr doctor?"

"Not often. On the other hand, they seldom die."

"A great blessing, doubtless," observed Lally drily.

He looked up at the great figure of the Madonna in her faded blue robe, standing, with her attendant saints, in clear light and shade against the background of the sun-flushed woods.

He knew that the doctor lingered in the expectation of an invitation to supper, yet could not bring himself to give it. He was not used to troubling about those who were indifferent to him, nor did he find it easy to assume the manners of perfunctory civility. He was also perfectly aware that this man disliked him, and he thought it foolish that they should inflict each other with their company.

But the doctor did not go; his small, fair eyes were full of curiosity; all the details of the young man's person would soon be spread through the village of Kiedrich, where everyone had already heard the story of Lally Duchene.

"You will find the method of governing Eberbach admirable, Herr Graf. The last commandant devoted his life to the work."

"It is admirable, within limits," replied Lally. "Once it is permitted to herd and confine together people for picking leaves and grass not their own—why, it could not be done better."

"Why, you would not complain of the game laws?" cried the startled doctor. "That would be to exclaim against His Serene Highness!"

"And that would never do," smiled Lally. He saw that the doctor, like most of the Duke's subjects, regarded their sovereign with almost superstitious awe and reverence, and this both irritated and amused his cynical mood.

"I daresay," pursued the doctor, "that the most forlorn wretch under your charge, Herr Captain, is happier than the miserable Popish monks who once enclosed themselves here."

"I believe these monks were happy enough," replied Lally. "Miserable men could not have built this magnificence."

The doctor glanced at the monastery buildings. It was obvious that it had never occurred to him that they were splendid; to him Eberbach was just a Government building with which he was proud to be connected.

"There are some bad cases here," he said, bringing the conversation to his own level.

"Of lunacy? I have observed them."

"Among the criminals also, Herr Captain."

"I observed no serious offences on my list."

"Theft, Herr Captain, drunkenness, dissoluteness."

"Ah," said Lally. "I saw that word above the cell of a young girl."

"Gertruda Gerhardt?

"Yes."

"She is in solitary confinement for five years."

"Is her crime so serious?" frowned Lally.

"You are interested, Herr Graf," said the doctor, with an instant leer. He disliked Lally the more the longer he studied him; his vivid face, his rich hair, his arrogant figure, his cold manners, his flamboyant history, all were so many causes of offence to the quiet provincial.

"She is very young," said Lally steadily, hating him.

"And very wicked. They say she is, as her name denotes, a witch."

"These rustic superstitions," smiled Lally, and turned away with his hand on his hip.

LALLY DUCHENE soon became acquainted with his duties, which were indeed monotonously simple.

In the morning the sergeant came to him with a list of the occurrences of the previous day—a mere formality; afterwards he drilled the soldiers, first in the ancient, then in the modern manner, and gave them their orders for the day—another formality, for one day went by exactly like another, with such slight differences as might be occasioned by the arrival or departure of a convict, a death, a funeral, or some change in the daily routine caused by the different seasons.

But these matters and other details, such as the management of the stores, the orders in the kitchen, and to the outside labourers, were managed by the sergeant.

The commandant had to every day inspect the workrooms and the quantity and quality of the work turned out by the prisoners. He was supposed to satisfy himself that the building was clean, the regulations all kept, strict discipline maintained, and that was all.

No reports were sent on to Wiesbaden. No inspector ever came to Eberbach. The commandant was complete master. Lally found that every day he had many hours on his hands; plenty of time to realise his loneliness, his extraordinary situation.

The whole institution was so foreign to him, and seemed within its limits so admirably ordered, that it did not occur to him to either interfere in the administration nor to throw himself with any enthusiasm into his duties; he did what was required of him, smiled, and was content to remain a figure-head.

He was sufficiently a great gentleman to keep his soldiers in awe of him, despite their knowledge of his history and the reason why he had been sent to Eberbach.

Yet he could not but be aware that they discussed him, mocked him, analysed him behind his back in no very friendly spirit, and this doubled his sense of isolation.

He stood twice alone—once in the natural solitude of the place, and once in this attitude of the human beings with whom he was forced to associate. The cathedral became a favourite haunt of his; even in decay and desecration Lutheran whitewash had not been able to destroy all the beauty of the rich carvings; some of the gorgeous windows still remained, and amid the stacks of wood and grass and last year's hay Lally found the splendid monuments of former bishops of Mainz and one to a Duke and Duchess of Nassau.

In the youthful features of the mailed warrior Lally thought he could trace a likeness to his present enemy, but it was likely enough mere fancy. The reigning Duke traced his descent by many winding and diverse ways to the ancient line.

The failure of the senior branches of the family, deaths of young heirs, decrees of European policies, had put this young man on the throne of Nassau, but lately made an independent principality. His blood was mingled with English, Russian, French; in many ways he was no proud reigning sovereign, as these earlier German princes had been, but a mere puppet of the larger powers whose kingdom might be swept away as swiftly as it had been created.

Yet Lally never looked at the presentment of the dead Duke without thinking of the living one. So, he thought, might Aurelio have looked in chaplet and mail, serene, straight-featured, cold.

It was a beautiful statue in marble nearly as fine as alabaster, probably the work of some Italian master. The detail was most delicate, yet so exquisite the proportion, the pose, and the expression that the whole effect was of manly strength and power.

The Duchess slept in veil and robe. A window above the tomb cast a faint rosy colour on to her smooth face and close-pressed hair—a golden pink, like the flush of life.

Looking at her, Lally must think of the lady at Wiesbaden who should have been of this same placid greatness, and was not because of him, and now might never come to such peace as this either in earth or heaven.

Lally felt impatient with all womenkind; they interfered unwarrantably with the easy flow of life which they were obviously designed to help. Their appeal was too obtrusive, their lure too flamboyant, their position too prominent, for an existence with which, after all, they played the smaller part.

Lally thought that there were so many things more important than women—ambition, conflict, friendship, adventure, power—aye, more powerful, too. Love lasted but a little while—it was but one among many lusts—why could it not come and go without leaving disaster in its path? He was a man who would have liked a hundred loves, but he did not want to attach much importance to any of them. They were to be the background of his life, not the main incidents, and yet he had allowed one of them to utterly pull him down.

His own fault, of course. He had chosen the wrong woman. He raged against the fate that did not permit you, without bitter consequence, to choose any woman, or to allow, Lally added cynically, any woman to choose you, for he had never found much resistance to overcome nor had to offer much temptation; so far his person had proved a passport for all his desires.

He looked at the marble Duchess with annoyance. She reminded him of the Madonna above the gate, so calm, so expressionless, and both, foolishly, reminded him of the girl Gertruda in solitary confinement.

He was vexed with himself that he even remembered this girl, for to take an interest in her was so obviously what any man in his position would do.

And he, of all men, should be, for the time at least, absorbed in one woman only. It was matter for further vexation that this memory did not absorb him, as by all traditions of chivalry it should have done, and as he must, to satisfy his own self-respect, pretend it did. He intended to behave up to any standard of honour that was demanded of him, but his inner thoughts darted continually away from the woman in Wiesbaden. He disliked to look backwards in his emotions.

According to his own instinctive convictions the incident was done with, and he alert for the next adventure, but he knew that neither the world nor the woman would have it so.

He wondered that she did not write to him. Certainly he had not written to her, but how was he to send a letter when the post went once a week by road to Wiesbaden, and any letter of his with that superscription was likely, no, certain, to be intercepted?

And he could think of nothing to write that he would not have winced to know that the Duke's cold eyes were glancing over.

But she, surely she could have written without portentous difficulty. He was glad that she had not chosen to do so. As he stood by the tomb a group of prisoners in their orange-grey uniforms came in under the charge of one soldier.

They were bringing in bundles of faggots, which they piled about a bishop's monument, It seemed strange to Lally that they did not endeavour to escape, for none were chained or bound; yet he knew that life could not be supported in the forest, and that the little Duchy, easily searched, could offer no hiding-place for any wanted man.

Still, it was strange to see these subdued creatures, most of them strong and young, meekly submitting to their bondage.

Lally would have liked to have spoken to them, but the discipline of the prison was that the commandant should never directly address a convict, and he did not want to make himself conspicuous. The sunlight that streamed in through the open door behind the men, the bundle of hay and dried clover and wood on the stained marble floor, the patches of mellow colour from the unbroken windows, even the quiet figures at their labour, made a picture of secluded peace. Lally, standing unseen in the golden dusk of the shadow behind the Nassau tomb, thought of those prisoners who never tasted this liberty, nor the sweet air of open day; those who saw nothing but the strip of sky visible through the high-set tiny window of the cell, who had to sit with idle hands, never exchanging a word with any human being, and who saw no one but the silent soldier who brought their food. Such was the punishment that girl Gertruda must endure for five years. Surely she would either die or go mad before this sentence was complete. He had been told that many of the maniacs had first been prisoners undergoing long sentences of solitary confinement.

Lally smiled as he recalled the doctor's solemn assurance that she was a witch. Poor wretch, if she had any superhuman powers would she be in such a plight? It fretted him that there was no one of whom he could ask her history; he chafed against the brutality which left all the female prisoners in the charge of men; he thought that these miserable creatures should be in charge of someone of their own sex.

He had only seen her once; it was no part of his routine to visit those in solitary confinement. There was no excuse by which he might see her again, though the key of her cell was always in his possession.

His fine hand went out and touched the marble duchess—the smooth contour of the cheek, the line of throat and bust, the piously joined and pointed hands. How would this great and gracious lady have dealt with such a one as Gertruda? Surely in ways of gentleness.

Then another thought caused his unpleasant smile—perhaps the duchess had been herself a Gertruda; perhaps, had she been a poor girl living in these times, she might have sat behind a door with "Dissolute" marked on it. There was a certain lady in Wiesbaden now—if misfortune had not overtaken her, she might have gone through life with as fair an aspect as any duchess of them all.

The prisoners left the cathedral, and Lally soon followed them into the orchard without. At the end of this was a field, now used as a graveyard. Lally could see the wooden crosses clear in the light of the setting sun; if she died in Eberbach she would have no different grave. It was foolish that his thoughts would run on her. He must see her again to satisfy himself that she was a mere ordinary peasant wanton.

Beautiful was the evening air, beautiful the placid sweetness of early summer, the vast spaces of the sky, the distant hills, the distant forest.

"To-morrow," said Lally to himself, "I will go into the wood—right into the wood." He had a longing to be away from everything, to think out, in great loneliness, certain confused problems that were pressing on his soul.

Slowly he walked round the cathedral. The buttresses sprang straight from the flowered orchard grass, and the trails of the wild rose tangled against the stern masonry.

The fruit trees were losing their last blossom with every soft breath of wind. Lally could see the tiny plums and cherries, a bitter green among the downy leaves.

He passed into the noble cloisters of the monastery which enclosed the scented square of the herb garden, and there leant against one of the columns and looked about him with the keenness of a man always sensitive to the outward appearance of things.

The lines of the cloister cut a pale sky from which the light was faintly receding, though it was still brilliant, and every detail of the stonework showed vividly distinct. In the spandrils of each arch were angels' heads, with clustered wings gleaming in smooth glazed pottery. The capitals of each column were close packed wreaths of flowers, the slender shafts of different polished stones.

The garden was divided into four by little box-edged paths; in one division green lavender, bay, rosemary, tarragon, camomile, poppy, fennel, sage, foxglove and vervain, basil and thyme, mint and parsley, and other small, plain, fragrant herbs grew bitter and fresh to the nostrils.

In the second division was newly raked ground broken by the bright green of young salads and the feathery spikes of vegetables; in the third were rose bushes clipped close to their stems above carefully dressed beds; and in the fourth a medley of lovely flowers most purposed to have medicinal properties, a few useful for essences, such as violet, marigold, wallflower, carnation, lily of the valley, verbena, stock, and geranium. These as yet bore but leaves, with here and there a closed curled bud.

In the centre of the space three round marble steps led to the well, a low white edge, a canopy of arching ironwork crowned with a gilt statue, from which depended the ropes and the bucket, which now stood on the top step, brimming over with water.

A man was working among the roses; he was the last object to attract Lally's attention. When he did give him a careless scrutiny, he saw that it was Luy. With a subtle sense of irritation he turned away, meaning to leave the cloister, when, as he turned, he stopped short.

Snarling at him from the shadows was a colossal and terrible face, a wild animal tusked and fierce. In an instant he saw it was a huge carving in relief above a door into the building, life-like and masked in shadow.

Lally remembered the legend of the foundation of Eberbach and smiled at himself; he changed his mind, too, about avoiding Luy, and turned back into the garden and called the man.

The fellow came instantly and saluted.

"A pleasant spot, eh?" said the commandant carelessly. "And you work here?"

"I understand plants, Herr Captain. This has been my work since I came here."

"The place is neatly kept."

"I found it so, Herr Graf. The monks took a great interest in this garden, as they had a distillery."

"I did not know. And a wine press, I think?"

"Yes, Herr Graf. You should see the cellars and the old barrels."

"And the distillery, what did they make, Luy?"

"Essences, soap, and liqueurs—perhaps other things."

"How other things?"

"Who knows? Those were queer days, Herr Graf."

"The monks sold their produce?"

"I do not think they needed to, Herr Captain. The bishops of Mainz often came here, and there were great entertainments, and many princely people were guests of Eberbach."

Lally thought that he spoke with a slight accent of pride.

"You know, then, the history of Eberbach?"

"Living here, with nothing else to think of, yes, Herr Graf."

"You told me that it was haunted," smiled Lally.

"Everyone says so, Herr Graf."

"Everyone is a fool, of course."

With these words Lally sent the man back to his roses. It was nearly dark in the cloisters; Lally looked up at the boar's head, grotesque in the dimness. "A strange thing to carve in a Christian church," he thought.

A soldier came up out of the gloom; he seemed unsubstantial save for his firm footfalls. He brought the commandant a letter from Wiesbaden. Lally glanced at the superscription, hastening to the open colonnade that he might see. As he saw the well-known writing he knew that the signature would be "Pauline."

"Herr Captain," the soldier was saying, "the sergeant thought that you should know to-night that one of the prisoners, Gertruda Gerhardt, is very ill."

Lally, staring at his letter, hardly heard these words.

LALLY forced himself to pay attention to the soldier, because he was afraid to betray his passionate interest in the letter. To gain time he asked how it had been delivered.

"It was left at the nearest post-house, Herr Captain, and a peasant brought it over to-night."

Lally slipped the precious epistle in his pocket.

"You said a prisoner was ill?" he asked distractedly.

"Yes, Herr Captain."

"Tell the sergeant to come to me later; I cannot attend now. What should it be to do with me?"

"It was thought, Herr Captain, that as the girl was so ill—"

"The girl?"

"—the doctor should be sent for, even to-night, Herr Captain."

Lally recalled then that the man had spoken of Gertruda Gerhardt.

"That young girl—so ill? Is there no woman to go to her?"

"No one, Herr Captain."

"Ask the Herr Pastor to go," said Lally quickly, "then beg him to come to me." He had really lost all interest in Gertruda, so completely was his being absorbed by the other woman. He had believed that her influence over him was ended, yet at the sight of that letter—

He found the curtains drawn and the lamp lit in his chamber and he walked straight to the light and tore open the thick envelope.

She wrote from Wiesbaden. Of course, she began with a reproach.

I have been left, as women usually are, lonely, defenceless. Could you not at least have written?

I have had to gather from strangers the news of your whereabouts. They say Eberbach is an unholy place, fittingly inhabited by criminals and lunatics. What company for you, so luxurious and fastidious! The Duke has been more than generous; his magnanimity astonishes, overwhelms, and shames! I lie in the light of it, touched, passive, helpless. One sees that there are many ways of love.

The postponement of the marriage has not yet been announced—again his delicacy, that it might not follow too quickly on your departure. I admire him in everything.

I am too wounded to write of our affairs or feelings. I only send you this to let you know that I live and rest in the Duke's kindness.

Forget as I forgive.

Pauline.

"I believe she is in love with the Duke," grinned Lally. "The jade!" he added softly. "'To let you know that I live,'" he quoted. "By heaven, I never thought that she would die of it. So she mopes and cries, and the Duke pities her, and perhaps, after all, she achieves her coronet—or might, did he not know too much."

Lally folded away the letter.

His vanity winced because she had written no word of love; because she so persistently praised his rival and his enemy, who had the upper hand now, and was the only one of the two worth courting.

"Women hate you when you fail," said Lally.

And what failure could be worse than this—to fail at love?

Well, he had failed, and this was the way she took it—already she set her lures for the other man.

Lally began to lose interest in her again; she was merely an incident once more, not a part of his present life.

He disliked her letter; vain, and calculated, and heartless he thought it seemed.

What did she mean by her reproaches? Surely she knew that he had gone into his exile, silently, secretly, as the Duke had ordered, because to resist would have meant a scandal.

The Duke's generosity! The Duke was playing with them all!

And she remained at Wiesbaden. Lally did not like that; he thought that her obvious course would have been to leave the capital—some pretext could easily have been found.

He walked about the strange, dim-lit room, this prison which love for this woman had closed round his hot ambitions. "She was not worth it," he told himself definitely.

Yet some tenderness flushed his anger when he recalled what had been between them. Surely, after all, it was not possible that she was turning to the Duke.

Well, he had lost her, and he was here, exiled, helplessly dependent on this generosity of the Duke! He laughed at himself; he could not subdue his buoyant spirits to any melancholy; life seemed very good to him, even life in Eberbach.

There was a zest in everything, a deep, curious, intense joy in the mere acts of moving and breathing, in the mere feel of the sun and wind on the face. It was as if there was some intoxicant in his blood that made every experience of mind and body a delight.

It was good to have loved Pauline; it was good to know that there were other women in the world, and that he was free to win them.

He would not write to her; it was so useless, and he felt so sure that the Duke would see his letter.

He was still in a state of subdued excitement, pondering Pauline, when the pastor entered.

Lally stared. Almost he had forgotten this creature's existence; certainly forgotten that he had sent for him. He disliked the sight of this dull, ordinary person with tired eyes behind horn-rimmed glasses and an undecided mouth.

"I have seen the young prisoner, Herr Captain."

Then Lally remembered. A flicker of interest showed in the eyes, now deep crimson brown from the rush of excited blood.

"She certainly seems ill," pursued the pastor evenly, "but it might be feigning."

Lally offered him a chair; for himself, he remained standing, one hand on his hip.

"And I was told of a very curious incident, Herr Captain."

"Yes?"

The pastor was now seated by the table; he took something from his pocket and held it out an instant.

"This was found this morning in the corridor outside the cells of the females in solitary confinement."

He laid an object both heavy and bright on the table.

Lally could not see what it was; the light was very dim. He caught up the lamp and approached the table. A broken chaplet of rich gold lay between him and the pastor. It was in the form of vine leaves, grapes, and roses, intertwined in careless profusion, all cut from the beaten gold.

Here and there the wreath was in part snapped across or worn into holes. It was dirty, stained with soft mould, and smelt of the dregs of wine long in cask.

Lally had seen such work before and heard it called Etruscan; he knew that necklaces and bracelets wrought in this manner had been found in Wiesbaden, that old Roman town.

"Someone found this and dropped it," he said, taking the thing in his hand.

"Who? Only one of the soldiers could have done so."

"Why?"

"It is obvious that it comes from the cellars; it is rank with stale wine lees."

"The prisoners never go there?"

"No—the soldiers but seldom."

"They all deny the finding of this?"

"Yes."

Lally shrugged his shoulders.

"But of course it is the only explanation, one of the men found it, concealed it, became frightened—after all, how could he dispose of it?—and flung it down where it was sure to be found."

As he spoke he put the chaplet down. The lamp was left on the table, and the yellow rays struck full on the gold that showed between the spots of dirt and tarnish.

"It was a strange thing to find in Eberbach," said the pastor.

He seemed both dull and suspicious, full of secret dislikes and enmities.

"It is not a Christian ornament," he added, "but heathen."

"I know," said Lally, "but it might have been found here. Who knows what hoards these old monks may not have had? It might be worth while to investigate these cellars," he added with a smile.

"All the treasures were taken out of Eberbach when the Duke dispersed the establishment. This, of course, must be sent to him."

"Of course," said the commandant, with his too ready sneer. "Now about this girl; it is impossible to send for the doctor to-night."

"I think it is her soul that troubles her," replied the pastor, with a sudden kindling of professional interest; "her wickedness."

"Will she speak to you?"

"No."

"What do you know of her?"

"Very little. I take no great interest in the prisoners—they are all so much the same. I am supposed only to teach the young ones—the children."

"You see them on Sundays?"

"Those in solitary confinement do not attend the services, and many of the others are Romanists. You know how liberal the Duke is."

Lally smiled; he was a Romanist himself, by tradition if not by practice.

"This girl was brought here in the usual way?" he asked.

"Yes, sentenced at the Courts in Mainz. But she comes from this neighbourhood—Kiedrich, I believe."

Lally was interested at this; had he not thought her a creature of the forest. Dissolute? He wished he knew her story.

"Will you not come and see her, Herr Captain," added the pastor, "and judge for yourself of her state?"

Lally gave him a sharp glance, but there was neither sneer nor smirk in the fellow's dull face.

He had suggested what Lally had himself much desired, though recently a more intimate interest had obscured this emotion.

"I will come at once, Herr Sandemann." He took up his keys; the pastor had left a little hand-lantern inside the door, which he used to guide himself through the long, intricate stairs, passage, and rooms.

"Do you know your way about Eberbach yet, Herr Captain?" he asked as he led the way through the dark building.

"No. There are parts of it where I have not yet been—the palace or royal suite of rooms where the princely guests stayed, the cellars, the distillery—"

"All these are shut up."

"Surely it would be worth opening the wine press and the distillery. The prisoners could work there."

"The Duke has no need to make money out of Eberbach."

"No," said Lally swiftly. "He makes enough out of his mineral waters and his spas."

The four beautiful beams of the lantern travelled over walls and floor, all whitewashed; here and again it touched a grotesque carving. More than once Lally noticed the boar's head. It made him think of a line in Pauline's letter—"They say it is an unholy place."

"What is the history of this place?" he asked abruptly. "There seems to be talk as if it had an ill reputation."

"A very scandalous one," replied Herr Sandemann. "The monks are accused of many wickednesses, orgies, and untold luxuries, even secret crimes and heathen rites. The peasantry say that St. Bernard was deceived by the boar who urged him to build here."

"How?" asked Lally, amused.

"Ah, they are just legends and fables, of course; you know how many we have on the Rhine. It is supposed that the valley was haunted by evil spirits, of which the boar was one, and that when the monastery was built they rushed in and took possession and debauched all the monks, and no blessing or consecration would get rid of them, so that while the other four Bernardine establishments in the Rhinegau were truly Christian this always secretly belonged to the devil."

"It is the wood," said Lally. "The influence of the wood is very powerful—anyone must feel that—Nature beating at the very doors of man's church. The peasants were trying to explain that when they invented their tales."

Herr Sandemann stared at him; he did not know how to continue the discussion on these lines.

"We are in the women's quarters," he said. "It is the last door."

Lally remembered it; it gave him a strange sensation to think that it would be so soon opened again.

Herr Sandemann did not seem to be much occupied with the girl; the conversation had introduced what he had made, in his dull way, the hobby of his monotonous leisure. This was the legendary history of the Rhine. He had collected, he said, many fables and tales, and had many books on the subject, if the Herr Captain would one day care to hear them.

Lally thought it a curious taste for one so prosaic, but promised to visit the pastor's study.

He unlocked himself the door above which was inscribed, "Gertruda Gerhardt, dissolute," and stepped into the cell.

At once he was touched with shame at the ease with which he had her privacy at his mercy, so small and bare was the tiny prison.

There was no light save that of the pastor's lantern and that of the moonbeams pouring full through the high, narrow slip of a window.

Their cross lights, gold and silver, revealed the girl on her straw pallet. A stool stood beside this, on which was an earthenware jug; in the far corner was a basin on a wooden shelf; nothing else in the whitewashed cell, which was pure and clean.

The prisoner lay as if she had flung herself down in an attitude of despair and then never moved. Her arms were across her face; her bare feet touched the stone floor.

Her worn and tight cotton garments—these provided by the prison—seemed to strain away from the full curves of her limbs. Across her bosom the buttons were undone, showing the white calico beneath; round her knees and ankles the poor material clung scantily. The heavy folds of her hair had escaped the common horn pins and lay across the mattress and the floor. Lally saw that it was not, as he had thought at first, brown, but a dark blonde, full of colour.

The young commandant stared, advanced, and held the lantern above her. She was beautiful in some almost unearthly fashion; her feet looked like pale gold, her arms and neck silver, in the mingled lights.

She did not move.

The pastor advanced, bent over her, and touched her; Lally winced.

"She is asleep," said Herr Sandemann, "and the fever has gone down. We had better leave her till the morning."

He spoke quietly, but Lally thought that he was moved.

"The moonlight plays tricks," he added. "She looks more like a nixie than what she is."

"Let us go," said the commandant abruptly.

As he shut and locked the door he thought he heard someone laugh.

"DID she laugh?" asked the commandant, hesitating by the door.

"Look and see if she has moved," said Herr Sandemann.

But Lally did not want to open the door again.

"It may have been from some other cell," he replied.

"It is also quite likely that the wretch was feigning," remarked the pastor severely. "She is supposed to be a person of great resource and trickery, and has the reputation of being a witch."

"So Luy told me. It is strange how these superstitions linger."

As Lally spoke he moved away down the corridor, which looked vast in the lantern light. No moonlight fell this side of the building; the Gothic window looked on blackness. The doors of the cells, one exactly like the other, showed in a regular succession, with the neat placards above each. Lally thought of the different individualities enclosed behind each of them, and again of that other woman whose letter lay in his pocket.

"Now we are here," said Herr Sandemann, who was more friendly in his manner, "there is something that I would like to show you if you have the time, Herr Graf."

"I am not eager to return to my solitude," answered Lally negligently; his thoughts were very far from the pastor, who again took the lead through a maze of passages and stairs and stopped at a low door, which was reached by descending three steps.

Herr Sandemann, entering, held up his lantern and showed a small disused chapel, bare and whitewashed.

Lally could see nothing peculiar in the place, but the pastor pointed out the wall to the east where there had been the altar space.

"You know," he said, "that the prisoners have to whitewash out the building three times a year. This was done shortly before your arrival, and this chapel found to have been shut up and neglected. There, on this wall, was a crude painting of St. Bernard, much damaged, but I bid the men clean the wash off. In so doing they discovered this."

He lifted his lantern higher and showed a faint but lovely fresco painting, still half hidden by coloured, dirty wash, and partly scraped away.

"Look at the subject," added Herr Sandemann. Lally peered close.

The design, blotched and damaged as it was, showed vaguely. Lally saw dim chalky colours of blue and yellow, green and a dim rose tint; then, aided by the patiently pointing finger of the pastor, he made out portions of a strange picture—the bare limbs of women, uncouth forms of animals, wreaths of fruits and flowers, and inhuman looking creatures, horned, bearded, not pleasant to look upon.

"Now what do you make of that in the wall of a Christian chapel?" asked Herr Sandemann.

"It may have come from some heathen temple."

"It is painted on the wall."

"But the building here is very old."

"Not older than the monastery—twelfth century, built by St. Bernard of Clairvaux," replied the pastor.

"Well, what do you infer?" smiled Lally.

The defaced painting pleased him; it suggested warmth and sunshine; here and there the delicate lines of a woman's face showed smiling and kind.

"Probably this was the scene of some of the monks' private orgies that an after generation endeavoured to turn into a chapel."

"Do you believe those tales?" asked Lally, as the two left the chapel.

Herr Sandemann was quite dull and fair about that.

"I cannot say so. The Rhine land is full of wild myths, most still credited by the peasantry. You know the stories of St. Goar and St. Ritza; of the Lorelai and the Gallows Mamikin; of the dance of the maidens who die betrothed but unwed; of the nixie and doomed dancers of Ranersdorf and a hundred others? Well, these things are all credited still."

"Where do you learn them?" asked Lally.

"From my pupils—from the peasants of my village. I come from Kiedrich," replied the pastor, with satisfaction. "I am collecting these tales into a book, which I hope to dedicate to His Serene Highness."

"The Duke has little interest in such things," remarked Lally. "He is straight from a serene and practical university."

"No, I suppose he has not," said Herr Sandemann unexpectedly, "or he would not allow all these noble castles, churches, and monasteries in Nassau to fall into decay."

"Ah, you do not think him perfect then?"

To this the pastor did not reply. He stopped before a small door that he said was of his apartment; he invited the commandant to enter, and Lally indifferently followed into the room.

This consisted merely of three cells opened into one, and was almost entirely lined with books. The air was close with the odour of leather and dust and lamp-oil; the furniture was plain to poverty.

Lally did not like the place, which was a fitting background for the little drab, dry figure of Herr Sandemann, and soon took his leave, not escaping, however, without the loan of an old volume which he promised to read.

Once in his own chamber, Lally lit all the candles he could find—four in an iron scone and two on the mantelpiece—besides the lamp. Luy was not waiting for him, and the building was entirely quiet. The golden chaplet showed in dimmed radiance on the poor table where he had left it.

Lally thought that it was such an ornament as might have been worn by one of the women dancing in the faded fresco. He put it carefully away in the topmost of the valises that still lay piled in a corner of the room.

He felt sleepless and excited—the cause, he thought, was Pauline's letter; the other incidents of the evening were but phantasies compared to this.

He took it from his pocket and read it again. It was clear that she was lost; he did not know whether to pursue her or let her go. Pride urged the first, inner indifference the second.

His feeling for the Duke—near hatred—remained unchanged; he hoped that time would give him an opportunity of crying "Quits!" with the Duke.

To distract himself he opened the volume lent him by Herr Sandemann.

It was ancient, and printed in Nassau, perhaps by some early successor of Gutenburg himself, the cover was parchment, the clasps brass. Lally, turning the pages, found himself in a maze of legend pertaining to another age.