RGL e-Book Cover©

King James II flees after the Battle of Boyne

From a painting by Andrew Carrick Gow (1848-1920)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

King James II flees after the Battle of Boyne

From a painting by Andrew Carrick Gow (1848-1920)

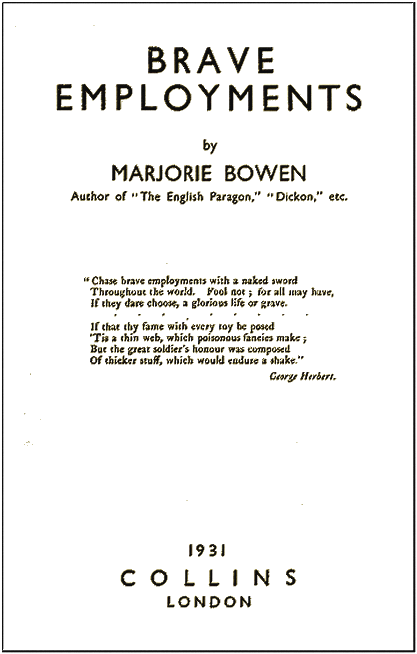

"Brave Employments," Collins, London, 1931

ONCE again Miss Bowen has maintained our trust in her as a writer of sound historical romance, a painstaking chronicler and a wizard who can clothe dead bones anew. This time she takes for her theme the upheavals in Ireland during the years 1689-1691, beginning with the arrival of King James II at Kinsale Harbour. It is, so far as dressed-up history ever can be, an honest record. Miss Bowen permits herself various surmises for the story's sake. For instance, she produces a motive for the murder of the notorious Henry Luttrell, whose death has always mystified historians.

It is difficult to say which is the best of this long but never tedious book, its fact or its fiction. There are some excellent character studies of King James, of Patrick Sarsfield, Earl of Lucan, in whose valour the Irish maintained faith until his "flight of wild geese" carried their hope away. Luttrell, Lord Galmoy and D'Avaux are also well portrayed. But, to the common reader, the chief interest of the book, apart from the picture it contains of distressed, seething and turbulent Ireland, lies in its love story. The Sarsfield, re-created by Miss Bowen, is a great and fastidious lover. There were three women in his life. The first of these was an almost symbolical figure, the spirit of Ireland herself, who was introduced to him by a Shanahus, or story teller. The second woman was Olivia Joyce, who married the Marquis de Bonnac and followed him to Ireland because she hankered after Sarsfield whom she had rejected. The third was Sarsfield's cold little wife. Miss Bowen allows these three to play their parts in and out of the story, to add relief to the records of history, and to supply a plot within the great plot of warfare. Her method is most successful, and her book deserves to be read both as a novel and a minor study of Irish character. — B.E.T.

Portrait traditionally identified as Patrick Sarsfield,

c. 1655-1693), Franciscan Library, Killiney. (Wikipedia)

Honor de Burgh (Honora Burke) 1675-1698,

who married Patrick Sarsfield. (Wikipedia)

Chase brave employments with a naked sword

Throughout the world. Fool not; for all may have,

If they dare choose, a glorious life or grave.

* * * * *

If that thy fame with every toy be posed

'Tis a thin web, which poisonous fancies make;

But the great soldier's honour was composed

Of thicker stuff, which would endure a shake"

—George Herbert.

The following apologia for the historical novel was made nearly a hundred years ago by the French critic, Mons. P. Douhaire:

"The alliance of history and fiction has nothing of the hybrid; it is universal and as old as the world. It is the essence of an epoch, the reality of the past made poetical. The active fecundity of our imaginations has need of a base and it is in the past it loves to take it...we all like to remake the world and the society of other times. This is the charm that we find in history; it is a feast where we satisfy our imagination. We each of us make in some degree an historical novel when we open the pages of the historians; for we fill in, according to our own fashion, the outline they trace."

THE author of the following narrative can think of nothing better as an excuse or explanation of the feelings about a type of fiction that is frequently misunderstood and undervalued, and of the spirit in which this novel has been attempted.

While errors of fact have been carefully avoided and the genuine circumstances of history as carefully followed, this is a novel in design and detail and makes no pretensions to be more.

No more need be said here than that all historical personages mentioned (including Lord Galmoy, Colonel Henry Luttrell and Galloping O'Hogan) are drawn according to what is known of their characters.

The spelling of the Irish proper names makes no pretension to be accurate; the usual English forms have been used throughout; nor, as the story concerns people of various nationalities, has there been any attempt to reproduce dialects or the manner of speech actually employed by the many foreigners who passed through Ireland in 1689-91.

For those readers who like to know something of the material

used by the historical novelist a brief appendix is affixed; the

author, in venturing on a subject that still provokes such bitter

controversy, feels it prudent, if not necessary, to give some

authorities for the view point taken and the incidents used.

M. B.

London, November, 1930.

IRRELAGH, 1680

"Where is the glory of thy sires?

The glory of Art with the swift arrow;

Of Meilitan, with the swift darting spears;

Of the lordly race of the O'Neil?

To thee belonged red victory,

When the Fenian wrath was kindled,

And the heroes in thousands rode to war,

And the bridles clanked on he steeds..."

—"Old Bardic Lament", from the Irish.

"I have heard some Great Warriors say,

that in all the services which they had seen in foreign

countries they never saw a more comely man than an Irishman,

nor one that cometh more bravely to his charge."

—Edmund Spenser.

HE suddenly saw her as an enemy.

"You are Irish yourself, mademoiselle, it is strange that you do not understand."

"But I do—a faery tale." Olivia Joyce did not care to be under the imputation of belonging to the defeated, the subject race. "I've no claim to be Irish, though; 'tis centuries since the Joyces left Connemara, Captain Sarsfield."

"More is the pity, and that Ireland should be alien to one bearing your name."

"Why, so it is, and barbarous, too, and I'll be glad to return to London."

She smiled, to humour him; she was not fine enough to sense that he felt her as hostile; he had been bred in Paris, trained in the French wars, polished at Whitehall; she did not believe that his wretched country could mean much to him.

"So you'll not marry me?"

"No. And you can understand why."

"I cannot."

"My father would tell you. He looks higher than a younger son, a gentleman of the King's Guard, a landless man!"

She affected to sigh romantically; she did regret the loss of this ardent lover, but she was cold and prudent; she preferred the fine, safe marriage her family were negotiating for her; she intended to go no further with this delightful coquetry he had taken too seriously.

"Tell me some more tales of your kingdom of Kerry." She smiled, enticing as a spread flower.

"I will not, since you believe none of them." He looked at her unsmilingly. "Do you refuse me because I am Irish, Olivia?"

"You are too downright. There is every obstacle between us. And I do not care for you enough to do anything foolish for your sake, Captain Sarsfield."

"You will never do anything foolish for the sake of any man."

He had been acquainted with her since they were children. He knew her indifference to human passions and human dreams. Yet had never ceased to desire to possess her with a perversity that was at once his torment and his delight.

He thought: "Why does she not like me enough?"

This was the first time they had been together in Ireland; chance had brought the young officer to his brother's demesne at Lucan where he had heard that Olivia Joyce was reluctantly visiting some of her mother's kin near Kenmare. When he had crossed Ireland to see her, she had welcomed him; she found the wet summer dull.

Now this interlude was over; she had refused him, he would go, she would return to London, then to Paris where her marriage with the Marquis de Bonnac would be concluded. Convention was heavy over both of them.

"It is raining again." She gazed out of the window, past trees, the wide, distant lake, mountains silvered with vapour, at a sky crossed with rainbows that leapt from peak to peak. "It is a mournful country, I do not know how people can live here."

"There are some who wonder how those who have Irish blood can live away. God knows, I count myself an exile!"

He considered her sadly, his usual gaiety overclouded, it was easy to see that she really was an enemy; descendant of renegades who had long since forsaken the ancient land to fawn on the conqueror. She was of mixed blood too, cold English, hard French, daughter of the merchants and the traders, yet to him lovely as a rose carved in snow, with her features of infantile purity, her fine locks of silver-gold, the exquisite delicacy of her shape. Perhaps her small mouth, so richly coloured, had already too firm a line, perhaps the gold-brown eyes had too calculating a gleam; perhaps, to the cynic and the experienced, her early youth gave promise of a future cold voluptuousness, wanton and heartless, but she was beautiful enough to Patrick Sarsfield who was a man who must have a goddess.

"Will you come with me to the Abbey of Irrelagh this evening?" he asked.

"To see a ruin and an old woman and, maybe, a ghost?"

"To say a charm with me under the ancient yew, Olivia, my darling, one that will bind us all our lives, whether you will or no."

His presence and his persistence shook her; her blood strove against her training; she was convent-bred, cautious and dutiful, ignorant, unawakened beneath her city manners, only twenty years old; she was determined on the grand marriage that meant a rich court life, but she quivered at the caress in the voice of this rejected suitor. The rain was pale at the window; the silent house was desolate.

"I go back to London to-morrow," she sighed; "the long journey is hateful, but I shall be glad to be away from Ireland."

"Come to Irrelagh this evening. I'll show you the wonders you laugh at, and you'll not laugh. The yew there is a thousand years old, the quiet woman knows much magic, or maybe I could row you out to Innisfallen, and there's the world well forgot."

"I could not come."

"You could. They leave you quite free. It is not far away."

She considered him, feature by feature. There was an uneasy stir in her liking for him that had been so serene; almost she was troubled. She regretted his magnificence, she felt jealous as she realised the other women who would gladly take this love she could not accept, she felt baulked by destiny and cheated by convention. The rainbows were brilliant beyond the rain. He opened the window and she saw him outlined against the radiance and moisture. He was of great height and strength, yet slim and flexible and not many years older than herself. She liked his clear brow with the thick fair hair, red as scorched flax, his noble outline—liked his well-shaped, full mouth, and the alertly-open gray eyes, his broad shoulders and slender hips. She liked the bravery of the King's Gentlemen which he wore so easily; she liked his strong hands and full throat, and the Irish turn in his speech, persistent through long exile. She inclined towards him, but she did not forget her admired father's judgment of this Patrick Sarsfield—"Reckless, thriftless, without influence or the gifts that make success, penniless...a younger son."

Fear and fascination opposed each other in her mind; his eyes grew heavy with meaning as, full of lightness and grace, he came back from the window; she had more beauty in his regard then than she would ever really possess. She saw the rainbows behind his head as he bent directly to her face.

"You'll come to Irrelagh this evening?"

A strong tremor ran through her yielding limbs; she knew that this was the end of playing with him, and she mourned the loss of a flattering amusement. She winced before the brilliant eyes so near, she sank beneath the warm lips pressed on hers, he held her close and she felt useless, helpless in the circle of his strength.

But her carefully-trained virtue asserted itself; she rejected the natural warmth that moved her, she refused to lose herself in this unworldly love, she chilled his tide of passion by her resistance. As he was very proud, he put her by...

To be rid of him and her own blind emotion, she said:—"I will come to Irrelagh this evening."

When he had gone she was ashamed of the heat in her blood, she almost hated him for disturbing her coolly ordered life.

The young man frequently looked back at the flat damp-stained façade of the mansion of the MacCarthys; through the swaying gray boughs of the dripping ash-tree and the lush lawn, he could long see the brightness of her spruce town dress at the wide window.

To him she was innocent and sweet as she was lovely; he could not see her as hard, ambitious, mercenary, petty-minded, though he disdained these faults in the stock from which she came; her nobility, like her beauty, lay largely in his generous fancy; she was no more than a pretty young woman, finely shaped.

Even her contempt of Ireland and her laughter at what she called his superstition, he forgave her; but in London he had been in two brawls with Englishmen who had sneered at his country, and his shoulder sometimes ached from a thrust got in a duel provoked by some insult to his despised island.

He lodged in a peasant's hut near the lake edge; he had only a few days before he must return to London; he put that out of his mind. He envied his elder brother who might live at Lucan on the estates; never before the visit had he known how dear Ireland was, how desolate and how hopeless. He realised that he was capable of two passions, each full of stimulation and inspiration—one for Olivia Joyce, one for Ireland.

The country opened about him generous with an unbelievable beauty; the deep solitude was flooded with a golden light that glanced sparkling in the misty rain; the distant peaks showed azure and violet against heavy veils of pure, tender vapour which glittered with raindrop hues. Changing shadows passed over the surface of the lake, ruffling the waters from silver to purple. All was warm, exotic, drowsy, the ferns and grasses clustered in rich tangles gemmed with drops of moisture, starred with prodigal flowers expanding in the damp heat. The smooth stems and dark glossy leaves of the arbutus waved in groves of extravagant loveliness. Patrick Sarsfield had not seen this tree before. He felt moved at this hidden exotic exceeding beauty that was the beauty of Ireland, which no one praised. So opulent and warm was the scene that he did not notice the loneliness.

At sunset he was in Irrelagh Abbey expecting Olivia Joyce; his very soul surged towards her in expectation. His romantic mind endowed her with all the beauty of the Ireland that she disliked. This moment made all his life that had gone before—the soldiering, the city days, the repetition of commonplace—seem utterly trivial, a wastage of time.

The woman he had met before at Irrelagh was seated in the ruins; she had told him she was a Shanahus, a story-teller, descendant of the bards or historians attached to the great sept of O'Donaghoe, Princes of Kerry. But it was the MacCarthys, Princes of Desmond, who had built the abbey; the Franciscans it had housed had long vanished; pious hands had repaired it two generations ago, but it now stood in desolate decay, surrounded by gravestones and dense groves of ash, oak and sycamore.

Patrick Sarsfield passed through the roofless nave; thick fragrant weeds grew between the stones that covered the vaults where lay the dust of kings. Mural tablets showed the stately arms and coronets of MacCarthy Mór, Glencare and the last of the O'Donaghoes. Above the gray altar waved ash saplings, long trails of dark, glossy ivy garlanded the porch. There was a perpetual sound of the wind sighing in the trees and long grasses, and through the empty belfry.

The young man joined the Shanahus in the gray marble cloisters. She sat under one of the moss-covered arches with her beads in her hands. Her dress and shawl were gray-green as the abbey stones, and her face was as expressionless as one of the saint-like masks mouldering above the pillars. She wore a hare's skin cap over a red kerchief tied under her chin.

"Good-evening to your honour."

"Good-evening to you, Shanahus. I have come to meet a fair woman, and you must give me the charm that will bind us for this world and the next. For, humanly speaking, she is denied to me."

"And what fair woman should be denied to your honour and you fine as King Finvarra? And like one of the Sidhe yourself with your red sash and the gold band on your hat."

"I've neither land nor money, Shanahus, nor careful arts. I've nothing at all but the blood of Conn of the race of Rory and of Rory O'More. And they are dead and the splendour of them, and this is a good place to remember it." He smiled across the gray arches to the overgrown graves which marked where the proud, the disinherited, the forgotten rested.

In the centre of the garth grew a yew tree, so mighty and spreading that the trunk was like a pillar, and the boughs touched the four walls of the cloisters. There was no tree more famous in Ireland; to profane it was damnation, to pluck a leaf carelessly was death. In the twilight the shade was black beneath the yew tree. The Shanahus peered there with searching eyes.

"Does your honour think Ireland is dead, and the last Prince of O'Donaghoe, murdered by the English, resting beneath us? You can see Castle Ross hollow to the moonlight, but the O'Donaghoe will rise every year and ride across the lake on his white horse. What can your honour see beneath the yew tree? The Phouca waiting, or the horned women making their spells?"

"I can see nothing but dark shadows, Shanahus. Teach me the charm that I may learn how to bind my beloved."

The gray woman looked at him wistfully; yearning, vague and unsatisfied were her eyes. She was a peasant, a beggar, but she roused in the young man an emotion enthusiastic, passionate, infinitely mournful; the shadow of great unattainable glories and losses fell over his spirit; the foreboding of useless sorrow darkened his heart. Without speaking he leant against the damp gray pillar of the cloister, the tips of the flat, black yew boughs touched his braided shoulder-knot. In his strength and fairness, with his red and gold, his air of noble candour, he looked indeed like one of the Princes of the Sidhe, who will never know death nor immortality, but who flourish in their beauty and splendour, till on the Last Day they vanish utterly.

"The finest charm I could give your honour and the kindest," said the Shanahus, "would be the power to hear the harp of the unseen people."

"And what benefit would I get from that?"

"Forgetfulness you would get. All the old memories of the race of Conn that torment you would be still. And you would not be able to guess the future that is coming to you."

"Is it evil, then, the future?"

"Evil it is not." The Shanahus stooped and plucked a long trail of ground ivy. "Hold this as a safeguard against the Evil One. It is bold to recite charms by the yew of Saint Bridget."

He smiled as he took the small, firm, shining sprig; he feared that Olivia Joyce would not come, and all the magic and beauty of this evening be lost like rare, cherished wine spilled on the common ground.

She was fearful and town-bred and foreign; he was sorry that he loved her, he felt hostile towards her and drawn with sudden passion to this sad spot of earth. Through the blackness of the yew he could see the misty sapphire brilliancy of twilight. The Shanahus recited, as she turned her beads, the glories of the royal house of O'Donaghoe. Great they had been and beautiful, slain in their pride, the earth lay on their white breast-bones and the foxglove grew on their mouldering hearths. Ross Castle was open to the dews and winds of heaven, and the empty lakes lay desolate beneath the bare hills of the Kingdom of Kerry.

Patrick Sarsfield felt the company of the dead gathered close about him in the shade of the great yew. Very ancient the tree was and unutterable the legends that enfolded it. Some said that is was from the very heart of Saint Bridget herself that it grew.

"The fair woman is coming," said the Shanahus. "The Merciful word, the Singing word, and the Good word—may the power of these be on all the men of Ireland!"

The young man startled; his heart beat hot and magnificent. A stately gold flashed behind the yew, the final sunburst coloured the darkened land. The graves were outlined in shadow and the raindrops glittered like fire on the rank leaves of wild flowers and the lush grasses heavy with moisture. In this transient light the Shanahus appeared withered and small like a bat, like the mocking Phouca itself. She pointed down the cloisters where the gold air could not penetrate. There in the shadows, dense and heavy, stood the woman.

She had disguised herself with care. A gown of gray drugget concealed her form, the linen kerchief tied round her chin was pulled forward to muffle her face. Without speaking she passed under the black boughs of the yew into the heart of the shadow.

The last light of the sun faded, the blue darkness, swift as the stroke of a wing, fell over the ruins of Irrelagh.

Patrick Sarsfield followed into the dense shade of the yew. In the dark hollow under the boughs he and the woman stood side by side. She put out her hand to him and he was profoundly touched that she had come. He drew her cold hand to his heart and felt a deep wave of excited joy suffuse his being. At that moment his whole life was vowed to her service.

In his warm eager voice, that no sensitive ear could listen to with indifference, he repeated the charm the Shanahus had taught him.

"By the power that Christ brought from Heaven mayest thou love me, woman! As the sun follows its course, mayest thou follow me. As light to the eye, as bread to the hungry, as joy to the heart, may thy presence be with me, O woman that I love, till death comes to put us asunder!"

Quick and soft she answered him:

"This is a charm I set for love; a woman's charm of love and desire, a charm of God none can break. You for me and I for you, and none else. Your face to mine and your head turned from all others!"

These whispering husky tones were strange to him; he caught hold of her and drew her swiftly through the black boughs. The sharp foliage brushed against them. When he had her unresisting in the gray cloisters he plucked the kerchief from her head. The twilight showed him a stranger in his arms.

Dark eyes looked up at him, dusky hair fell on his sleeve, a creature who was in all different from Olivia Joyce smiled at him with beseeching tenderness.

Patrick Sarsfield felt the keen humiliation of one fooled by his own romantical dreaming; he set the girl from him and turned bitterly to the Shanahus.

"Belike I deserve this for meddling with old wives' trumpery, but what is at the bottom of your trick?"

"It is your honour who is tricked," replied the Shanahus coolly, "not to know the woman of your heart when you hold her. How long have you lived in exile, Patrick Sarsfield, that you have let yourself be deceived by the daughter of the enemy?"

He looked at the young girl who still leant against the gray marble cloisters; even through his disappointment, his disillusion, something in his blood responded to the fantastic moment, he thought of dark childhood tales of the unseen people, of the Sidhe who sometimes visit the earth to draw mortals into their invisible world of delight and damnation.

"Who are you?" he asked.

"Look on me," she replied. "Can you love me? Every time you have come to the lake edge or walked in the ruins I have followed you. Could you not join your fate to mine?"

He strove to put aside the sense of strangeness that overpowered him almost to faintness.

"You are unknown to me, and it must be that you speak in mockery or folly."

The Shanahus rose; she seemed angry, her eyes sparkled under the shade of her hare-skin cap.

"Would you pledge yourself to the cold foreign woman of the mean soul and the narrow heart? Do not the Sidhe hate the niggard hand and the bargaining tongue? Would you turn your back on your own people for the foreigner? This is Ishma O'Donaghoe who has waited for you since she was cradled in the ruins of Ross Castle. Is she not fitted for you, royal and fair, lover of music and song, and noble pleasures?"

The girl moved forward from the deeper shadows, but it was now so dusk that she seemed but a cloud wraith.

"Did the Shanahus mistake," she sighed, "when she told me you wished to say the love charm with me?"

He knew she was beautiful and graceful. Her voice was full of a soft, enticing melancholy; all the passionate qualities of his race responded to her; all the extravagance of dreams ever creating incredible passion and glory, all the fantastic belief in wonder, all the deep yearning towards the mystic, the unseen, that had always been hidden in him, overlaid by the limitations of his commonplace life, rose in his baffled heart, and almost he could have accused these two of bewitching him, almost he could have believed they belonged to the lost race of the Sidhe. He crossed his breast and fixed his mind on Olivia Joyce.

"We meet and part as strangers," he sighed painfully.

Instantly the girl turned and walked away down the cloisters, huddling her dark shawl over her head. In a moment she had disappeared among the graves. A louder sigh came from the ash trees and the tall grasses as the wind rose across the shivering lake.

The Shanahus slipped her hands into her bosom.

"It is a pity that a grand gentleman like your honour should try to mock the power of God. But the charm is said and will not be broken not even when one of you lies beneath the hawthorn by the Holy Porch, and the other far away under sods the strangers have turned."

The warm, soft dark was about him like a charm indeed. He made a movement to follow the girl, but missed his way; when he turned about, the Shanahus had gone or was hiding from him in the interlacing shadows.

He was alone in the ruins of Irrelagh. He had thought to sit here with Olivia Joyce waiting for the moon that was to guide them home. Safe in her bed, contemptuous of him and his love, she would be watching the crescent rise through the ash trees on the lawn. He sat on a gravestone and took his head in his hands. He thought of the woman who had come in place of Olivia Joyce. He had rejected her; but these were his people and this was his place; he yearned towards them in a mute longing. He found nothing fantastical in the episode and the charm he had uttered, and her reply seemed to be repeated in the sighing of the ash trees over the altar stone, in the murmur of the grasses on the graves.

When the moon had mounted through wraiths of blown, hurrying clouds, and cast an uncertain light over the ruins of Irrelagh, the young man rose and returned through the groves of arbutus to the cottage by the lake's edge. Wet ferns brushed against his knees, the scent of night flowers was in his nostrils. The quivering lake was pallid beneath the moon clouds and purple dark of the woods of Innisfallen.

The owner of the hut where he lodged had returned from fishing; he was cooking salmon over a fire of arbutus wood, the glowing light of the flames fell over Patrick Sarsfeld as he paused, and the Kerryman looked at him in a great admiration. In this race, only he may be King who is strong and beautiful, splendid and gentle.

The peasant would have been happy to give his life for this noble gentleman.

"Is there a woman lives here or near who is named Ishma O'Donaghoe?"

"There is not. Has not your honour seen the graves of them in Irrelagh, and they slain by the English?"

The smoke was blown across the lake and mingled with the moonshine. Swift veils of fine cloud confused the glittering radiance of light on sky and water. The smoke from the arbutus wood vanished, as did the sense of the meeting and parting in Irrelagh. A trick put on him by a cunning peasant who had thought him credulous. But she had not asked nor waited for money.

The young man gazed across the lake to the moon-misted hills. All his life the truth of his heart and soul had been repressed. In dry routine, in serving foreigners, in learning their manners and their catchwords, in loving one of their daughters, his powers had been laid waste.

And he would return to the dulling round of commonplace; Irrelagh, the whispered charm beneath the black yew, the Shanahus and the girl who had asked, "Could you love me?" would be but fragments of a thwarted vision.

His nature, ardent, sensitive, enthusiastic, did not resent the play of the Shanahus. There had been something lovely in the mockery. In the warm breath of the secret young woman had been, maybe, the spell to connect him with all from which he had been exiled so long—Ireland herself, desolate, forsaken, captive.

He wished to put up a little prayer for many things, but his heart was heavy. All night he watched by the shores of the lake. The wind grew more lusty in the arbutus, the ash and the oak, yet remained but a gentle sound. The warm rain fell on the soft mosses and lush grasses. In his gold-corded, scarlet coat Patrick Sarsfield rested among the tall, strong ferns, in the shelter of the waving sycamore. Sometimes the moonbeams struggled through the mournful vapours, the thick boughs, and fell on his face, pale and finely shaped with the upcurling locks of flaxen red and the wide gray eyes heavy with defeated slumber.

In her warm bed in the old mansion of the MacCarthys Olivia Joyce woke to listen to the drifts of rain through the ash trees on the lawn.

She was pleased that she had been able to resist a childish impulse to go to Irrelagh. She wished she could forget his kiss. His mouth was soft and finely shaped, and his breath had had a perfume of health and the pure air. She moved her limbs uneasily beneath the coverlets, she hoped she would never see him again. She tried to think of the lean, dark face of the man she was pledged to marry. As the moonlight cast vague beams on to her bed she hid from them beneath the sheet. Comfortable and dreamless, she slept.

When Patrick Sarsfield came to the quiet shadowed house in the

morning he found she had gone. He did not follow her; his

loneliness was inexpressible.

O BOYNE, once famed for battles, sports and

conflicts,

And great Heroes of the Race of Conn,

Art thou gray after all thy blooms?

O aged old woman of gray-green pools,

O wretched Boyne of many tears.

O River of Kings and the sons of Kings

Of the swift bark and the silver fish,

I lay my blessing on thee with my tears

For thou art the watcher by a grave—

O Boyne of many tears.

My sons lie there in their strength

My little daughter in her beauty...

—Bardic Lament, circa 1690.

"Ce qu'il y a d'effrayant pour la sagesse de l'homme c'est que le

jour où les rêves les plus fantasques de l'imagination seront pésés

dans une sure balance avec les solutions les plus averées de la

raison, il n'y aura, si elle ne reste égale, qu'un pouvoir

incompréhensible et inconnu qui puisse la faire pencher."

—Charles Nodier,

Le Pays de Rêves.

PATRICK SARSFIELD leant on the gilt rail of the French ship and watched, through glowing gleams of rain, the coast of Ireland; the distant hills of Cork, dimmed by the soft, swiftly-moving clouds which passed across their summits, showed, even behind the straight March rain, with that tender azure he had seen in no other country. The long, gray, racing waves of the sea parted round the noble ship as she turned into the bay past the grim promontory of the harbour with the bleak outline of Fort Charles in the east; spray and rain wetted the Irishman's clear pale face and his thick, strong, fair hair blown stiffly behind him as he stood bareheaded on the poop.

He thought:

"That is my country and I am a man in the best of his years with some power and authority, maybe some gifts of strength and wit. What can I do for Ireland?"

He considered his youth and early manhood spent in foreign service, carrying the Lilies of France behind Turenne, or wearing the gold and scarlet of a gentleman of His Majesty's Guard. He yet wore that uniform, for he believed his chance had come to serve Ireland, and emotion, almost impossible to suppress, possessed him as the sombre, rocky coast showed nearer through the mist; above the ship loomed the old Head of Kinsale, with the desolate ruins of Duncearma Castle; hawks and sea eagles flew through the rain to their high rocky eyries; pallid beams of sunlight fell aslant the misty, moving vapours that blurred the grand outline of the purple cliffs of Cork and Waterford.

Nearly ten years had passed since Patrick Sarsfield had last looked on these hills; they seemed then ten empty years of waiting. He recalled the ruins of Irrelagh and the night he had spent beside the ashes of the arbutus fire on the banks of the lake, the black yew and a strange girl whom he had never seen before or since, and with whom he had exchanged a love-charm. He smiled at the persistency of his own folly in remembering such futility, yet he knew that this smile was but an assumed sophistication resulting from the routine of his ordinary life, and not touching his wild and secret heart, his deep and fantastic beliefs.

The decks of the magnificent French man-of-war were crowded with men straining for a first glance of Ireland. Some few were exiles returning, but most were foreigners and, of them all, only Patrick Sarsfield was lost in single-hearted love for the land at which he looked. These weeping skies, these dark secret bays, jutting crags, and lonely stretches of lofty hills, even the chill, blue pearly light which penetrated all the drifting rain and was, to Patrick Sarsfield, so lovely, seemed alien and desolate to these strangers, forbidding to the exiles used to foreign comfort.

Count d'Avaux, who represented the French king, shivered into his mantle. He was an elderly man, a civilian, of refined habits, his thin blood soon ran cold. He smiled at his companion, the Marshal Konrad de Rosen.

"It looks forbidding, I had hardly supposed so grim a coast."

De Rosen replied, in his gruff, off-hand manner:

"No matter for the land, my dear Count, it's the people who concern me."

He spoke with feeling, for he was in charge of nearly five hundred captains, lieutenants, cadets and gunners who were to train the Irish kerns and squireens into an efficient army not only able to hold their own island, but if need should be, to undertake an invasion of Scotland.

De Rosen, rude, violent tempered, but able and experienced, wished he had a convoy of ships behind him with ten thousand Frenchmen. He gloomed at the prospect of raising his army from this country which he believed was half-barbarous. He glanced doubtfully and shrewdly at Lieutenant-General Maumont and Brigadier Pusignan who, wrapped in their greatcoats, were silently leaning against the rail. They were regarding the coast of Ireland with inscrutable eyes, and De Rosen knew that their thoughts were the same as his—suspicious, discontented, disdainful.

"I wish," he grumbled half to himself, "I knew more of the Irish."

"The Irish gentlemen," remarked D'Avaux, "are of the finest material in the world. Consider Colonel Sarsfield—"

"He has been bred in France, he has served France, and for years. I take him to be almost a Frenchman."

D'Avaux replied quietly with his dry, precise air:

"Indeed you make a vast mistake, Marshal. Colonel Sarsfield is nothing but an Irishman, and I dare swear that, of all those in this ship, he alone has no thought of self-interest. I shall do my utmost," he added abruptly, "to have him made Brigadier."

De Rosen shrugged, pulling his cockaded hat across his broad brow, for the driving rain was strong.

"I have not noticed," he replied, "that he has more than ordinary ability, and it is against my principles to give high commands to foreigners."

D'Avaux insisted, with some emphasis:

"Use all the material you have, my dear De Rosen, all the material you have! If you can find honesty, and patriotism, and enthusiasm, and sincerity—well, make the most of them. You will find them as useful qualities for your purpose as paid jobbery or hired knavery. Colonel Sars 'd," added the old minister, "was the only one of His Majesty's Guards who remained faithful to him—the only one, mark you, my dear Marshal."

"That," replied De Rosen, "might set him down merely as a simpleton, and, indeed, I take him to be a visionary, one with fantastic notions about loyalty and patriotism; I do not know, my dear Count, that I have great use for such a man."

"But, I take it, Marshal," the diplomat reminded the soldier dryly, "that you yourself are actuated by principles of honour and loyalty."

"But you and I serve France—" De Rosen checked himself with a shrug. "How can you make such a comparison—France and this miserable island?"

"Yet perhaps, my dear De Rosen, to Patrick Sarsfield this miserable island means the same as France to us." But he recalled that his companion was a Livonian. He lightly touched the Marshal's arm to point his words. "And since we are forced, my dear De Rosen, to use this barbarous, boggy rock and its inhabitants, let us make the most of men like Patrick Sarsfield. Trust me, I have observed him well. Look at him now and tell me if there is not an asset there?"

The two glanced covertly at the Irishman who was oblivious of them and every one else on the ship. He stood apart from all, and even to the dry, professional insensibility of De Rosen, there was something touching in his isolation, his self-absorption, and in the magnificence of his appearance; the force of his splendid presence would have impressed in any company.

"Certainly," admitted De Rosen, "he would look well at the head of an army."

"The Irish people may think so," commented D'Avaux. "He is descended, I believe, through his mother, from some of their mythical champions, and it is very likely he will arouse in them an enthusiasm which we shall find useful."

De Rosen did not reply. He intended to have no rivals, least of all an Irish rival, in this mission with which his king had entrusted him. To him it was quite intolerable that an Irishman should be put on a level with a French officer in any post. He wondered at D'Avaux's championship of Patrick Sarsfield.

"Keep him a colonel," he said at length abruptly, "see what use he is in recruiting men; I hear he has come into his estates now—"

"By his brother's death," replied D'Avaux, "I believe he has some rich lands and a fine fortune. You may be sure it will all be dedicated to His Majesty's cause. But it is the man himself, not his money, who will be most useful to us."

Again they keenly and cautiously considered the Irishman with the eyes of traders ruminating over a piece of merchandise.

Patrick Sarsfield, then about thirty-four years of age, was far above the common height and had that aspect of noble candour and heroic enthusiasm which is one of the most valuable qualities in a leader of men. This was given by the ease and grace of his carriage, an air of radiance that came from his thick, upspringing, richly-curling flaxen-red hair, the healthy pallor of his finely-shaped face, and the wide, clear alertly-open eyes which were something of the azure gray hue of his native skies; he had great charm, vitality and a look of incomparable distinction.

De Rosen, bred in a court where personal appearance was a ready passport to fortune, conceded:

"It is a pity he is not a Frenchman—or a Russian."

The high, violet hills, with low clouds blowing about them like tattered banners, darkened the bay with purple shadows as the French vessel, burnished gold through the pure mist, steered for Kinsale. Above the crow's-nest fluttered the blue and silver elegance of the Bourbon flag and the hot, tawny, yellow and vermilion of the Royal Arms of England.

Count d'Avaux made his way cautiously across the wet deck to where Patrick Sarsfield leant, his face towards the encroaching darkness of the Irish hills.

"This must be an agreeable home-coming for you, Colonel Sarsfield?"

The Irishman started, and almost painfully, for he was sunk in a reverie and had forgotten time and place, but on seeing the little Frenchman, he instantly smiled with his ready good humour which was entirely without artifice or calculation.

"Agreeable? Indeed I do not know, monseigneur." He spoke French with cultured ease, but to D'Avaux he was all Irish as he stood there outlined in the moist and shifting light against the purple azure Irish horizon. "I have great hopes surely, for I see that there is much to be done."

"And you should be the man to help us do it," smiled D'Avaux. "We, too, have great hopes and in you, Colonel Sarsfield."

"I'll do what I can for the King and for Ireland."

D'Avaux's smile deepened as he noted how the last three words had been spoken unconsciously.

"I intend," he said, "to use all my influence to have you made Brigadier."

Sarsfield faintly flushed. He was not personally ambitious but avid for some scope in which to prove his powers.

"Indeed, monseigneur, I had hardly looked for that."

"You undervalue yourself." The Frenchman spoke with gracious kindness. "You allow yourself to be jostled by more presumptuous men. Your service has been very distinguished and, believe me," he added, "I at least know how to prize a probity and honour without stain."

Sarsfield, by breeding and nature exquisitely sensitive, did not know how to answer this. He almost winced before what seemed flattery, but D'Avaux added in a tone which took all offence from his commendations:

"Believe me, my dear Colonel, we are surrounded by men bat-blind to those words: 'probity and honour.' I represent His Majesty King Louis. I stand for his interests and nothing else, as you, I believe, stand for Ireland and nothing else."

"I should not have put it so boldly," murmured Sarsfield. He put his hand to his cheek which was wet with rain.

"No, you have grown accustomed to other loyalties. Your allegiance is to King James, that for the moment jumps with your own secret desires. Pray do not think me prying, Colonel Sarsfield, but too well I know the rarity of men like you. Look to me for friendship and support."

"Can I make use of them?" asked Sarsfield wistfully. "I know not yet what I can do for any man, even for myself. It is true I have my brother's estates, the Manor of Lucan, some two thousand a year, but I am not of the position of my Lords Mountcashel or Galmoy."

"But you will be more important. Pray realise that in this ship we have a few trained officers, three generals, a certain amount of ammunition and money—equipment for an army; all else is to be found in Ireland, a country of which we none of us know much."

"Ireland will give of her all, monseigneur, no doubt."

D'Avaux smiled. "But I have spent my life at court, in diplomacy, I know the difficulties of bringing even an ordinary task to a conclusion, and this is no ordinary task, my dear Colonel, but the setting on his throne again of a king who is, between you and me, detested in his own country and has all Europe, except France, against him. We have also," added D'Avaux in a confidential tone, "to deal with men of varying nationalities, ambitions and honesties. His Britannic Majesty himself will never be either energetic or popular."

"Why," asked Sarsfield candidly, "do you put these obstacles before me?"

D'Avaux replied instantly:

"Because I see, perhaps, what no one else in this expedition will see, that we shall have to rely on men like you who understand the Irish."

He turned away abruptly and joined a group of French officers pacing the upper deck. The wind shouted in the flapping wet sails, the sailors strained at the creaking cordage; Patrick Sarsfield glanced up at the two flags which straggled out with difficulty against the rain in a wan gleam of sun—the flag of France, the flag of England, but where, he thought, the flag of Ireland? He was conscious, as never before, of being surrounded by self-interested foreigners and aliens meaning to use him and his country for their own ends. Had not the old man warned him of as much just now? Wishing to use him, to gain his friendship, his confidence, for his own ends? He had been clever enough to see that he, an Irishman, cared for Ireland. He had pounced on that proud, hidden patriotism as another factor in the game for France.

Patrick Sarsfield, watching Kinsale come into view, knew that he cared nothing at all for France and nothing at all for England, and nothing at all for King James praying in the cabin below. But that he cared everything for this chance to redeem Ireland from the yoke that pressed so heavily on her galled shoulders.

"He said that I understand them, that I might have influence...Suppose I had such influence?"

The mist lifted in long shreds, showing the dark trees, the pale cleft valleys, the little poor dwellings, the distant lonely grandeur of the hills. An unreasoning love of this hushed ancient land shook him; he felt stupid before his own emotion. The years had passed and he had done nothing save sometimes weep a little in his heart for Ireland, sometimes pray for Ireland in an alien church. The years had passed.

"One must die or grow old and what will have been done? Is this a chance? Can I do anything?"

There had been something, Sarsfield thought, easily contemptuous behind the Frenchman's graceful courtesy; he wished to use every possible material for the aggrandisement of France; he was playing a fine, difficult game for his master; he looked upon the Irish as an ignorant, credulous rabble who must be made to serve their turn.

Sarsfield's superb glance rested on the widely extended outline of the noble bay. He held out his hand through the chill purity of the vaporous rain. A sea hawk, stern and beautiful, swooped near his open fingers and his drenched laces.

The shouts of the French sailors, bringing the ship to anchor cut across the lawless cries of the ocean birds.

FITFUL gusts of soft wind drove apart the rain clouds and showed the translucent, azure heavens above the pale, vivid mountains. Foaming on the rocky shores in opal traceries the strong swell of the Atlantic Seas made a restless surge in the wide bay. Above, the Old Head of Kinsale, dark and mighty, broke pale and melancholy sunshine, the pearl-gray gulls circled round the mighty foreign ship, with the proud alien standard floating above, with stout sails furled as she rode at anchor.

Patrick Sarsfield, leaning on the taffrail, watched the small boats putting out, through the breaking waves, to Kinsale. To him the land was all glamour, crossed and recrossed by silvery-golden light and trailing mists of azure moisture; as the balmy wind shifted, the loose clouds revealed prospect after prospect of tender distance, the mountains so radiant and of so exquisite a glow that one might not tell whether they were of earth or heaven.

To sail across the great rolling gray waves of the seas, through lowering tumults of gales and lashing storms of mid-ocean into this warm harbour, circled by these hills of gold and pearl, was to find credible the ancient fable that said Ireland had been created by a race of magicians and wizards, the Firbolgs, who, before they had perished utterly through the onslaught of brute force, had left much of their magic behind them.

Looking at this land enveloped in shifting light and shade, Patrick Sarsfield forgot the company he was in, where he stood and what tasks lay before him; his spirit was rapt away to mossy fairy glades, through forests filled with immemorial silence, to the infinitely pure light on the infinitely far hills...

He was about to take a place in one of the boats; his mood fell. He glanced at the other men disembarking; they were alert, absorbed in their own affairs, silent, save for those who had to give commands. Their faces were turned with a secret curiosity and a secret hostility towards Ireland. Sarsfield could discern that they disliked this warm mist, this slanting rain, these lonely hills. If, to contemplate the fair land had been exaltation, to contemplate this company was depression. The words of Count d'Avaux, spoken in what appeared such candid friendship, had dissipated something of Patrick Sarsfield's romantic and enthusiastic illusion, for he was, in spite of his native readiness to visionary self-deception, keen and intelligent. He saw all those disembarking at Kinsale as cards in a great pack being dealt out by that foreign king in Versailles. None of them—neither the old monarch (who had been hurled from his English throne) nor his two stripling bastard sons, nor Melfort, his Scottish minister, nor the loyal exiles who accompanied him, nor the three able French generals, nor all these experienced trained officers, recruiting sergeants and gunners, were anything to King Louis but so many cards that, for the moment, he happened to hold in his hand, and Ireland was merely the table on which he laid them. Among all these there was only one who was of any real importance in Versailles, and that was the diplomat who represented King Louis, D'Avaux, the man who had the money, the authority, and the secret instructions from Louvois and his master.

As Sarsfield watched the trim, well-equipped, well-groomed Frenchmen disembark from boat after boat, he recalled very vividly the royal personality which was behind them—that urbane, courtly gentleman, with his smiling courtesy, his Gaelic face with the high cheek-bones and the narrow lips, who had so overwhelmed the fallen monarch and his faithful followers with flattery, with compliments, with gifts, and who had cared nothing at all for any of them, but merely used them as so many assets in the struggle he waged against the only man who had ever challenged his supremacy in Europe.

"And I, too, I and my like are to be used," thought Patrick Sarsfield. "And what do any of these care what becomes of Ireland as long as their king gets best from the Dutchman?"

But, as he set foot on Irish soil his spirit lifted again.

"It is for us to make our count in this; surely while they use us we can use them."

The rain clouds wholly lifted and the wintry sun, mild and melancholy, shone on the shouting people who were on the quay-side to welcome the Frenchmen. It was noisy as a fair. Kerns, priests, monks, peasants, beggars, gentlemen on fine horses, esquires on foot or on steady small garrons, barefoot, handsome girls with shawls and drugget gowns, gentlewomen on palfreys, all contended in a struggling, shouting press to welcome the Frenchmen, and the king whom the Frenchmen had sworn to set upon his throne again. None of these people knew anything of European politics; few knew much of English politics. They were not cognisant of any of the events which had led to the second son of Charles I. losing his throne as his father had lost his before him, nor did they know why that great fleet had sailed from the Netherlands in the November of '88, nor why the old king's nephew had taken his throne amid the wild acclaim of the English and at the snap of a finger; nor did they know why, having lost two of his kingdoms, James Stewart had decided to make his stand in this his third; nor had they any knowledge of the complicated statecraft which had decided Louis of France and his ministers to choose their island (which had seemed, during the last two hundred years, to have been forgotten in Europe) for the scene of his renewed conflict with William of Orange.

All that these Irish, shouting and struggling in their enthusiasm on the quay of Kinsale, knew was that this king was the king of their old faith, a faith hitherto persecuted and despised; that he had come to lead them against the Saxon oppressor, the loathed and feared Protestant settler; that Tyrconnel, his viceroy and friend, had armed and set them against these same Protestants, refusing to recognise the revolutionary government of England, and promising them deliverance from that tyranny which had been their lot since the days of Strongbow, of Elizabeth Tudor, of Oliver Cromwell.

Patrick Sarsfield considered this impulsive, thoughtless crowd and smiled wistfully. He, who had long been close to the courts of Versailles and Whitehall, knew something of the affairs of Europe and could plumb the depths of the Irish ignorance. He stood aside and watched the French officers disembark. Quick and sensitive to every impression, he glanced at their faces; for the most part these had set and inscrutable expressions, but here and there the aliens showed an active disdain, as they made their way through, what no doubt seemed to them, a crowd of barbarians. They had the aloofness and the concentration of men who have a duty to perform, who may neither question nor complain.

Two other Irishmen, Colonel Henry Luttrell and Claude Hamilton, Earl of Abercorn, who both had served with Patrick Sarsfield on the Rhine under Turenne, stepped on to the wet quay. Sarsfield thought that not only their uniform but their air set them apart from their countrymen.

"They are like foreigners here," he thought sadly. He remembered, what he had not troubled to recall before, that Abercorn was not of the native Irish, but descended from the conquerors—Normans of the Pale.

The earl shrugged as he looked at his friend on the quay and seemed to show that he too remembered he had a right to disdain the native Irish, but Luttrell smiled easily, and paused.

"Hold your hand and bide your time, my dear Sarsfield, these are troubled waters and I dare swear stinking too, but maybe we can fish in them to our own advantage."

Patrick Sarsfield liked Henry Luttrell; there was something bold yet reserved, enthusiastic yet haughty in his demeanour; his character Sarsfield did not know very well, but he had found Luttrell in everything attractive, and among the friends he so readily made, he had singled him out for his special confidence. It was with him that he walked along the cobbled, narrow and dirty streets of Kinsale.

When the Irish gathered on the shore saw the good supply of ammunitions, the imposing arms and massive equipments landed by the French, the files of trim cornets, mechanics and gunners who disembarked, they became distracted with a lively stirring of joy and excitement. Every church bell in Kinsale was ringing. The music of pipe and harp sounded from every alley corner. The kerns and the squireens were pulling off their long frieze coats and throwing them down on the mud and stones for the king and the French to walk over.

Luttrell and Sarsfield were quartered in the same house, one of the best in Kinsale, and next to that which Tyrconnel had prepared for the King. When they had found their way there through the confusion, Luttrell touched Sarsfield's arm:

"I did not know that Madame the Marquise de Bonnac had come with the expedition."

"I knew, but I had forgotten. Have you seen her?"

Luttrell smiled towards the house opposite. There, in the low-arched doorway, full of shade, stood Madame de Bonnac, hesitant and reluctant, with some other officers' wives, staring down the wet, dirty street. Sarsfield turned into his lodgings with no comment, but Colonel Luttrell laughed gently; he knew something and could guess more of how matters were between Patrick Sarsfield and this lady.

Olivia Joyce had married another man nearly ten years ago, and she and Sarsfield had been separated by time and space, chance and circumstance, but Luttrell knew that Sarsfield could not be in her presence without uneasiness, that he had kept inviolate that love idyll of their common youth. Colonel Luttrell never showed how much he knew or guessed, even his laugh just then might have meant something else; but Sarsfield, whose spirits were already sunk, felt them further flag and wither at the sight of Madame de Bonnac. He wished that she had not accompanied this expedition, and recalled with a pang how near they were to the ruins of Irrelagh and the mansion of the MacCarthys, where so many years before, he had asked her to marry him and she had dismissed him without regret; and he had turned from what had wounded him, to earthly vanities, for consolation.

Henry Luttrell peered from the window and watched the French officers searching for their quarters.

"What will they make of Ireland?" he mocked. Then, "Did you see the Livonian's scowl?"

"He was wondering, no doubt," said Patrick Sarsfield dryly, "where he was going to discover the ten thousand to wear his fine equipments. Did you mark how he glowered at the rabble, lowering and scornful, how he put them aside with the back of his gloved hand, as if he would not have them press on him too close? He may be hated if he does not have a care."

Luttrell, leaning easily in the window-place, answered relevantly:

"You could find the ten thousand Irish, Sarsfield."

"If I was allowed to recruit them as Irishmen to fight for Ireland, maybe, but will they be drilled and officered by Frenchmen to fight for a French quarrel? And, as for the king—" He checked himself.

Luttrell finished the sentence:

"The king is an old, a burdensome, a miserable man, with neither grace nor prudence. Besides, he counts for very little—he is reproached, nicknamed, scorned as weak and low; it is D'Avaux who is everything, even De Rosen is under his orders." He added casually, "Madame de Bonnac is at the window opposite. She really is very beautiful, in a loose and carnal fashion, even after the usage of the voyage. What folly for a woman like a glass-house lily to come to this miserable country!"

"She may not wish to leave her husband for perhaps many a long campaign," said Sarsfield, without irony.

Colonel Luttrell of Luttrelstown laughed again. He was lithe, of medium height, dark and elegant, with an easy, well-bred, good-humoured air, and a touch of lightness in all he did. He had a certain influence over any one on whom he chose to exercise it, and it was difficult to discern that the essential man was wild, reckless and unstable; though he was clever at flattery, as a rule he disdained such beguilements, but fascinated merely by good nature, his air of casual candour, the attractiveness of his personality; his face was well shaped, his eyes curious; one disfigured by a cast, which, however, seldom showed under his heavy lids; he was foppish in his habits.

One of D'Avaux's secretaries, greenish and sour from the sea voyage, came to beg Colonel Sarsfield's presence at His Majesty's lodgings. Henry Luttrell lightly wished his companion ample luck.

"Nobody singles me out for favours," he mocked, "but D'Avaux seems to have taken a sharp liking to you. I saw him talking to you on the ship, hat in hand—smiling like a ferret."

"He had no good matters to say," replied Sarsfield, buckling on his sword. "He merely reminded me very civilly that we are all pawns in the game played by His Most Christian Majesty."

Lord Tyrconnel, who had come posting from Dublin to receive his master, had done what he could to prepare a regal lodging, but the best house in Kinsale was not magnificent, and in the eyes of the French officers used to Versailles, Marli, the Louvre and Fontainebleau, the apartments prepared for His Majesty were wretched; this was even worse accommodation, they whispered to each other with a sneer, than they expected to find when on an active campaign in Flanders or Italy.

King James himself peered round with a muttering disgust, then dropped into the worn leather chair drawn up by the wide wood fire. He had refused any food, but warmed his stomach, queasy from the sea voyage, with brandy; when Patrick Sarsfield was shown into his presence his grim humour had not abated, and he listened with listless annoyance to the bitter remarks of the men who were arguing about his chair.

Sarsfield knew all these. D'Avaux himself, Tyrconnel (James's loyal viceroy who had held Ireland for him when his other two kingdoms had slipped away) John Drummond Earl of Melfort, His Majesty's Scottish Councillor; Marshal de Rosen, and the king's eldest bastard son James Fitzjames, Duke of Berwick.

Patrick Sarsfield waited inside the door, apart from this group of men. For a while the king took no notice of him at all. He leant forward and began to complain to Tyrconnel, sometimes muttering under his breath, sometimes raising his voice in sullen protest, thus silencing the harsh arguments of the others.

Everything, he declared, was wrong. He told D'Avaux that his comfort had not been properly considered on the voyage, told Tyrconnel that his reception had been contemptible, told De Rosen that it was ridiculous to bring officers and no soldiers; he complained and lamented:—

"What is the use of attempting anything in this accursed country?"

D'Avaux and De Rosen, clear-headed and unimaginative, concentrated on their responsibilities and their work, made but superficial response. In Melfort's remarks only was there some sympathy; he also detested the Irish, and the circumstances that had sent him to Ireland.

The young Duke of Berwick held himself dignified and inscrutable; his eyes flashed to Sarsfield a look of understanding. To both of these young men the old king seemed a symbol of disillusion and defeat. Here was royalty in eclipse, one of an unfortunate house most unfortunate, one who had, foolhardy in the extreme, tempted his destiny and brought all his honours tumbling into the dust beneath his feet; one who still blamed all but himself.

Sarsfield was sorry to see the king's heavy, full-veined hands shake as he held them over the spluttering fire, and when he said he was thirsty Tyrconnel offered him, casually, a wooden noggin of goat's milk.

The king seemed to perceive something of his own humiliation; he muttered to Melfort, who paid him more deference than did the others:

"The Lord hath broken the man in me—I grow old."

AT the first pause in His Majesty's renewed complaints D'Avaux put in quietly:

"Here is Colonel Sarsfield, sire, whom I have sent for to wait on you."

The king's heavy, swollen eyes glanced up ungraciously at the Irishman.

"Monsieur D'Avaux wishes me to make you a brigadier, Colonel Sarsfield," he said. "What can you do for me?"

"Sire," replied Sarsfield gravely, "as much as any man of my power and position may."

He was sad with compassion for the old king whose whole life had been exile and misery, who had always been greatly detested in England both for his religion and his character, who had never made many friends, nor evoked much loyalty, and who had, at the climax of his fortunes, been forsaken even by his own children. It was not possible that many could have loved this James Stewart, who was a passionate bigot and a cold voluptuary, characteristics which do not gain the affections of mankind. He was also of a narrow understanding, obstinate and arrogant, and one who could never bend himself to the gracious word, or engage with the generous gesture and (defects which would have mattered less had he been able to disguise them) withal cruel and tyrannical.

He stared sourly at Sarsfield, though he knew well enough that this man was the only one of all his guards who had remained faithful to him, that he had been in the skirmish at Wincanton, one of the few who had drawn their sword in his cause against the Prince of Orange, and that he had refused the offer of the usurping prince to confirm him in his estates and employ him as an envoy to Tyrconnel.

"It is necessary that we raise men immediately and I think you are among those well qualified to do this, Colonel Sarsfield. Must I be plagued with business? It seems I am to have no moment to myself."

The king pulled his broad-leaved hat over his brows.

D'Avaux very respectfully, yet as one who is master of the situation, said:

"Much must be arranged before we get to Dublin."

Tyrconnel took the word, he had been silent hitherto, considering with intense dislike the rough, passionate De Rosen, whom he already saw as a rival. The Livonian appeared to regard the viceroy with disdain and fumed in gross impatience, anxious to be about his own business.

Tyrconnel stepped in front of the king and began to expound, with many fine words and wide gestures, on his own high services. He was, he flattered himself, the only man in the room who had any influence with King James. He had been the rakish friend of his early licentious manhood and always in his confidence; though he bore the magnificent name of Talbot he was only of the middle-classes, yet he stood there an earl, Commander-in-Chief of the Irish forces and Viceroy of Ireland. He related with much enthusiasm how he, when every one else had forsaken His Majesty, had held Ireland firm to his cause, and done his best to reduce Derry. With his deep voice, with his majestic gestures—for he was a man of a noble and commanding port—Tyrconnel painted an encouraging picture of the state of the last kingdom belonging to His Majesty.

Sarsfield listened with a rising hope that after all there might be in all this something for Ireland. The viceroy was Irish, though not native of the soil, but descended of the English of the Pale. He glanced about him and, seeing that every one was listening to him intently, became more glowing in his account of the condition of the kingdom.

"The diligence of the Roman Catholic nobility and gentry," he grandiloquently declared, "have raised about fifty regiments of foot and several troop of horse and dragoons...I have all defined as accurately as possible in my army list; I have distributed among them above twenty thousand arms, but they are mostly so old and unserviceable that not above a thousand of the matchlocks may be of use. There are," he added, "about one battalion of Guards, together with MacCarthy's, Clancarty's and Newcomen's troops, all pretty well armed, also there are Mountjoy's several companies...I have besides three regiments of horse, my own, Russell's and one of dragoons."

As he came to a pause waiting for the silent king's praise, De Rosen asked sharply, "If all the Catholics in the country were armed?" And Tyrconnel was forced to admit that they were not, whereas the Protestants had great plenty of war material, and the best horses in the kingdom.

"And your artillery?" asked De Rosen with a scowl.

Tyrconnel replied that he had about eight small pieces in a condition to march, the rest not mounted...

"From what you told me," put in D'Avaux suavely, "I fear, my lord, that you have few stores in the magazine, little powder and ball, that all the best officers have gone to Ulster and there is no money in cash."

Tyrconnel lifted his lip at the Frenchman.

"All that is true. You must remember, sir, that this country is the only one that has held firm to His Majesty, that all the north is in rebellion, even in other parts of the country we have many Protestants and settlers who are better equipped with arms and money than the native Irish; though I have done what I can it has been impossible to completely efface these difficulties."

"And you have not," jeered De Rosen coolly, "been able to reduce Derry, that is a pity."

At mention of this defiant town which he regarded with a peculiar dislike, the sullen king flared up:

"That nest of rebels must be reduced at once—I have been much abused in this business. You shall have all I can give you—cannon and mortars. I consider it is of the first consequence to master Derry."

"We shall do that soon enough," boasted Tyrconnel, "with the fine help that we now have from France. As soon as Your Majesty is in Dublin and has summoned your parliament, I doubt not these sturdy rebels will lose some of their stoutness."

"They will receive help from England, without doubt," said D'Avaux. He did not add, what he perfectly well knew, that King Louis intended to create a diversion in Ireland which should bring over the flower of the English army and possibly the usurping prince in person. Louvois, the French minister of war, had even said that it might be possible to detain the Prince of Orange ten years in Ireland with his best generals and troops, while the King of France swept the board in Europe.

Melfort put in:

"I hope we shall not be long for Dublin. The news from Scotland is of the best. Claverhouse has roused the entire Highlands. If we could but get His Majesty to Edinburgh the struggle were half won—"

"We must think first," put in D'Avaux, "of getting His Majesty to Dublin."

The king agreed with Melfort. After a few hours in Ireland he felt more exiled than in France, where he had had every comfort, splendour, luxury and deference. The winter had been bright and shining in France, crisp snow in the parks and clear blue skies above the bare allées, but here, this greenish, pale gold sunshine streaming athwart the endless wreaths of mist, this incessant rain, these hordes of dirty, shouting, barbarous people, this rough accommodation—all irritated King James into a melancholy of distaste. He had for a long while resisted King Louis's advice to "make his stand in Ireland;" now he regretted that he had in the end taken it; like all of his race and caste he utterly despised the neglected island and its inhabitants and could hardly keep his speech from disdain of them, even in face of Tyrconnel and Sarsfield. Painfully he kept to the business in which Tyrconnel, D'Avaux and De Rosen had instructed him.

"Do you think you could raise a troop of horse, Colonel Sarsfield? I intend to ask as much of Berwick, Abercorn, Luttrell, Dangan, Sutherland, Parker and a few others. I suppose you have enough influence to get some men from your own estates?"

D'Avaux put in shrewdly:

"My Lord Berwick is to make an attempt on Derry immediately. Colonel Henry Luttrell is to be Governor of Sligo. We will find some post of honour for you, Colonel Sarsfield."

The king sat moody, sunk-in his chair, as if he had forgotten all of them. There was a certain stately grace in his gaunt figure and his haggard face, but that was all he had of kingliness. He was very richly dressed in the French fashion—cinnamon brown velvet, gallooned, looped and scrolled with gold bullion, much costly lace and an imposing blond peruke. But all this luxury seemed but a fantastic comment on his dispirited old age.

Tyrconnel crossed to D'Avaux, eagerly flattering the Frenchman; though he resented De Rosen (who might challenge his military ascendency), yet he was keen to keep in favour with the King of France: as D'Avaux had written to his master, "if a Frenchman had been made Viceroy of Ireland he could not be more zealous for the interests of Your Majesty."

The viceroy knew that through D'Avaux's interest he had been promised the patent for a dukedom; if his manners had not been very polished and engaging there would have been something fulsome and fawning in the deference he paid to the French plenipotentiary. The viceroy was a big, strutting, magnificent man with something of the haughty port of King Louis himself and when he spoke loudly, with many gestures and flourishes, he seemed to dwarf all who were about him.

The king sat silent as Tyrconnel spoke to D'Avaux; Sarsfield crossed to the window place where Berwick and Melfort whispered with De Rosen and told the French commander that he believed he could by his own influence and at his own expense raise a troop of two hundred and fifty men.

"If every gentleman of your standing does as much," conceded the Livonian, "we shall not do so badly for cavalry."

Berwick remarked:

"Tyrconnel has been very energetic and done remarkably well, but from all I can hear the north is strong and the Protestant opposition considerable, even without they send nothing from England."

"But the moment," said De Rosen, "they know that I am raising an army they will send troops from England."

Berwick shrugged. "Well, we must do what we can. If we have trained men to oppose them—" He shrugged again and added slightly: "It seems to me that we have gotten into a barbarous country, and that it will be very difficult to make good soldiers out of these people."

He spoke without the least intention of offence to Sarsfield, for he had really forgotten that that officer was native Irish, and considered him more as an Englishman or a Frenchman, which last indeed he was by training. But the very fact that the slighting words were spoken so thoughtlessly, added to their sting.

All his life Sarsfield had known how the Irish were regarded by the rest of Europe. The bitterness of that knowledge was accentuated, he felt, when he was on his native soil.

He looked at Berwick shrewdly and wondered whether he disliked him or not. This young prince had a remarkable personality. He was the son of Arabella, the sister of that John Churchill who, long the favourite of King James, had been the first to desert him with cynical coolness. If this youth, half Stewart, half Churchill, with many of the gifts of both brilliant families, had been legitimate, it is possible his father had not lost his throne. He was then twenty years old, Jesuit-trained, reserved, stately, cautious beyond his years, fastidious in his manners, alert and sensitive under a smooth and austere exterior. He had entered the service of the Emperor at fourteen and at the age of sixteen had distinguished himself in commanding troops at the siege of Buda; he was essentially a leader of men. Recalled from the battlefields of Esseth and Mockhals to help support his father's falling government he had distinguished himself with ardour in the Stewart cause, striving to maintain Portsmouth against the Prince of Orange. He had been one of that small company who had gone with King James when he had escaped the guards at Rochester and crossed to France in a small boat which had landed at Ambleteuse at six o'clock on a Christmas morning.

Sarsfield envied him; he was so young, he had every opportunity for glory, "for it is almost better to be the base-begotten son of a king than to belong to a country wholly despised."

The king rose, peevishly cut short all their mingled talk, Tyrconnel's boasting, D'Avaux's advice, Melfort's cautious suggestions. He was weary, his priests awaited him, he had an intense longing to cast himself into the comfort of what would have been (in another man) a spiritual ecstasy, but which was with him, some thought, merely the support of a heavy superstition. He dismissed all save Melfort at whom Tyrconnel cast a look of growing dislike; the viceroy feared the quiet and elegant Scotsman who undermined his influence with the king.

They went down the mean stairs into the mean streets of Kinsale; the last rays of watery sunshine fell on the huddled houses and the rain clouds were gathering again.

Two French officers, acting on the king's express instructions, kept back with scant gentleness the crowd of Irish enthusiasts who loyally besieged His Majesty's door, clamouring to kiss his hand, his foot, even for a glimpse of him. The remarks the Frenchmen made to each other as they kept the street clear caused Sarsfield to wince. He said impetuously to D'Avaux, who walked at his side:

"No one will be able to manage these people who treats them like dogs."

D'Avaux replied:

"That is why I wish to employ Irish officers and gentlemen like yourself as much as possible, Colonel Sarsfield. I rely on you, your loyalty and discretion, that is why I have got you brigadier in command of the second Troop of Horse." He glanced up at the tall Irishman striding beside him over the cobbles, and added: "You do not seem as pleased as I thought you would have been with this mark of confidence from His Majesty."

"His Majesty," repeated Sarsfield, "you mean the King of France?"

D'Avaux smiled. He knew, and Sarsfield knew that there was only one king for him.

They parted at the door of D'Avaux's lodgings. The diplomat's heart was heavy; there seemed before him a task of almost impossible difficulty. He secretly despised and disliked the feeble, sour bigot whose every act was, to a man like D'Avaux, one of almost incredible folly, and he saw this King Log who had neither the wit, the courage nor the presence to play the leader, was surrounded by profiteers, turncoats, traitors and dishonest jobbers. Tyrconnel was violent, blustering, indiscreet and, D'Avaux suspected, corrupt. Melfort was sly, cautious, dishonest and probably cowardly. Berwick and his younger brother, Henry Fitzjames, were mere youths, probably serving their secret ambitions. De Rosen was a good man, but utterly ignorant of Ireland, hard and autocratic, and not likely to get on well with Tyrconnel. Then there were the native Irishmen like Galmoy, Galway, Abercorn, Luttrell—impulsive, impetuous, hasty, who, long-exiled from their own country, could have but little influence, quarrelling among themselves, poverty stricken...

"There is only," said D'Avaux to himself, "one single-hearted, single-minded man, and that's Patrick Sarsfield, and exactly because," added the diplomat with a bitterness born of a long experience, "he is single-minded and single-hearted, honest and a patriot, every one else will be against him, and I shall make myself exceedingly unpopular if I venture to support him."

He lingered at the door of his house and watched the figure of the tall Irishman going up the narrow street, the last rays of precious gold gleaming through the moving mists on to the fine appointments of his uniform.

"If I had my way, I would make that man Viceroy of Ireland, put him in full authority over all the others."