RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Belgravia Annual, Christmas 1895, with "Orazio Calvo"

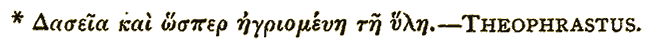

AT a considerable height above the sea level, in the middle of a chaos of mountains, and not very far from Monte Cinto, the culminating point of the chain which traverses Corsica, stands the Villa Calvo. It is a great pile, half castle, half palace—half northern Italian Gothic, half southern Italian Byzantine—rising sheer from the brink of one of those stupendous ravines which are the commonplaces of the island. The ever-growing tale of tourists who sip absinthe and black coffee in the Hôtel Continental or al fresco in the piazza at Ajaccio during the early spring, have not seen it. Its solitude, in fact, could not be more complete. In some of its aspects it conveys the impression of a natural outgrowth of the landscape. Around it stretch those primal forests of ilex and laricio pines, which from of old caused the island to be described as "thick," and, as it were, savage with wood;* and towering above it—nearly always clad in snow—great crags of gneiss, of granite, of porphyry, and of mica-slate. Four miles away, seated lower down on a ridge, and swept in season by the frigid Tramontana wind, dozes the squalid village of Spello, with its white-washed box-houses, gutter tiles, scavenger-army of wild dogs, and windows paned with paper smeared in oil of olives.

The Villa Calvo itself is now the most forbidding of desolate

places. The flags of the courtyard are seamed with wild lavender,

and cistus, and the rich grasses of the heights; the two gardens

are jungles of lentisk and walnut, the scarlet berries of

sarsaparilla, and every kind of sub-tropical bindweed; shutters

left open by the retainers as they fled from the house still

groan to the highland Levante, or rot in the sun; buzzards and

ravens, the deadly spider malmignata, and the black bat

know it well; roofs buried in mosses show a tendency to fall in.

The place is the very sanctuary of gloom. It is situated, too, on

the more deserted side of the island, called by the Corsicans the

"near," i.e., the east or Italian side.

The noble house of the Calvi, Venetian in origin, had established themselves as great territorial signori (technical for our "nobleman," and so quite different to the Italian word) in Corsica by means of some one or other of their sons at a very early date. The original stock indeed, after playing a turbulent part in the history of the Republic, extirpated itself by the very exuberance of its own passions, the last of their number perishing by the poisoned dagger of his jealous wife in 1605. The off-shoot, however, found in the still greater insanity of Corsican political warfare a congenial life-element, and grew fat. The fortress-town of Calvi still bears their name in the north-west. Corsica passed under the suzerainty of Pope, Marquis of Tuscany, Pisa, Genoa, France; and with each change the house of Calvi knew how; by its adroitness, to find a stepping-stone to still greater power. From their sinister activities sprang the factions of Red and Black (Banda Rossa and Banda Nera), and taking the Black side, they became the mysterious centre of those intrigues and massacres which for centuries turned the province into a little hell. Considering the proverbial poverty of Corsica, the revenues of this violent race became enormous; their influence boundless; till at last they grew to be regarded by the peasants with a profoundly superstitious awe. Their power indeed received a check when, joining the popular party in the insurrection of Pàoli in '55, they suffered some loss of territories, but most of these were regained under the more favourable régime of the earlier period of the Convention. They were till lately regarded in Corsica as the last surviving of the great feudal signori, who migrated from the mainland between the tenth and sixteenth centuries.

It is, however, of the very latest scion of all of this volcanic family that I wish to speak. I first met Count Orazio Calvo in the midst of a bewildering maelstrom of light and music and colour at a masque in his own Hôtel in the Rue de Rome. All the world was there, and I could not for the life of me imagine why he singled me out for the patronage of his talk; I remember, however, that it was his whim to profess a deep admiration for the English, whose language, indeed, he spoke perfectly. I at once set myself to the study of a man Whom I saw to be not only remarkable, but unique. To find such a person—a rude Corsican grandee—profoundly learned, of course astonished me, though years of Paris failed to add an atom of real polish to his manners; and though his hardly-concealed contempt for all men and things included a contempt for his own acquirements also. Of the license of the Paris of his day he was the high priest, acknowledged and consecrated. He was known to be an atheist, yet he had his religion—the religion of excess; only, the possible excess of a Mephistopheles, not the excess of a Heliogabalus. It was easy to see that he despised what he did, and did it only because he despised it somewhat less than anything else. Yet he was the opposite of blasé; for an altogether abnormal energy was written on every feature of his body. His prodigality was in all cases distinguished by a certain furore of daring and originality; but the feeling he inspired was not so much admiration as fear. His rage was the very rage of the tiger; and though I feel sure he cherished a secret bitterness at the interval which divided him from the rest of men, yet a wise instinct warned the gayest of his satellites in the midst of the wildest Bacchanal never to address him with familiarity. He had a leonine habit of roaming far and wide through the slums of Paris in the small morning hours; and stories of mad munificences performed by him at such times were circulated; but his charities, I thought, if they existed, could only be the stony, if prodigal, charity of the gargoyle which vomits for the thirsty. Of lovers' love he knew, of course, nothing; and the possibility of little Cupid coming to shoot baby arrows at such a heart, would have been a notion so exquisitely comic, that, had it occurred to anyone it must have set the entire Calvo Olympus in a flare of quenchless laughter. Round such a man, the décadents, the artist-class, the flâneurs and étoiles, and all the unfathomable demi-monde of Paris flocked—he was too volcanic a rough Naturkind to tolerate the monde—calling him king. He received in addition the sobriquet of la petite comète. None of his friends, I was given to understand, had ever seen on the lips of la petite comète—a smile.

In personal appearance he strongly resembled several other Italo-Corsicans whom I have met, and was not unlike that specimen of his singular countrymen who happened to become world-famous. He was below the middle height, and not too stout; yet he gave an impression of extraordinary weightiness, as though molten of lead. His face was of perfect classical beauty; black hair streaked with grey; skin hairless, and of the dirty olive of waxen effigies not yet painted pink. His brow was puckered into a perpetual frown; eyes cold as moonlight, glancing a downward and sideward contempt; forehead bastionné, columnar; jaws ribbed, a hue of graven brass; lips definite and welded; the whole face, the whole man, one, knit, integral—an indivisible sculpture.

Four or five times I met Orazio Calvo in Paris, and always he evinced the same disposition to take me, as it were, by the hand; while I, imagining a distinct element of doubt and even danger in his friendship, rather avoided la 'tite comète. I shortly afterwards returned to England, and though rumours of the excessive splendour of his revels sometimes reached me, the count, in the course of some three years had pretty well passed out of my active memories.

Suddenly, one morning, he stood before me in my chambers in London.

He seemed unconscious of my amazement, and informed me with the old air of sultan majesty that he had travelled in his yacht incognito and alone to England, and a friend being, for certain reasons, indispensable to him, he had sought me out. Health was the jewel which he sought; and, in truth, he looked haggard enough. "The bracing country air of Britain "—could I assure him that under conditions of perfect quiet and seclusion?

Noting in him a tendency to puff and corpulence, I suggested vigorous exercise. Something that I took to be a laugh rattled in his throat. But why not?—I insisted. If he would not walk, had he never heard of such a thing as the bicycle? I myself took an annual tour through parts of England by that means, and should be delighted to accompany him now.

With this suggestion he finally fell in, and we started. It was the beginning of the red-ripe Autumn time. The count, it is true, took somewhat unkindly to his machine, once flying into a hurricane of passion and making it the object of a rain of kicks from his rather short legs. But he quickly began to show signs of the connection between this method of locomotion and bodily well-being. The journey became more and more pleasant, till we reached a delightful retreat in Dorsetshire—a little farm belonging to a widow lady, whom I had long numbered among my friends.

This lady, of comparatively humble social position, was also of that entirely lovable type of English woman characterised by a profound natural piety—sedately gay, puritan, perennially fresh '—whose qualities unite to remind one of the wholesomeness and sweetness of home-made bread. The two extremely lovely young ladies, her daughters—Miss Ethel and Miss Grace—added to her odorous home something of the colour and the charm of Paradise.

I may mention incidentally that the two girls were twins, though they possessed none of the resemblances so often accompanying this condition. Grace, with a complexion of dawn-tinted snow, was dark, rather tall, with a superb neck; Ethel was the sweetest flower in the world, fair and winsome.

Into this shadeful and quiet home I, with my friend Orazio Calvo, intruded. I had previously put up for considerable periods at the farm; but our present stay was only timed to last three days. When these had passed, however, others followed, a week, two. My companion showed no disposition to depart. It was the golden season of harvest, and with remarkable gallantry for him, the count daily escorted the ladies on their walks in the lanes and fields, entering with them into the life of the country, and watching by their side in the evening the Pan-ic levities of the reapers. His tongue was loosed, and he spoke to them of the world, and its glory. I know not what of misgiving, foreboding, gradually took possession of my mind. As he sat under the porch by moonlight listening to the pure and simple songs of the ladies, I could see how the cynical man of the world—whose notions of Woman had been derived from the peasant-girls of Corsican villages, and the étoiles of the Ambigu and Varietiés—how he, now first in his life's course, realized that an earthly creature may yet be of heaven. I could see him revelling in the transport of an entirely new, a divine impression.

I proposed departure. He refused. I strongly insisted. "I shall go," I said.

"In which case," he replied, "nothing is so certain as that you go alone."

Then, after a while, a new discovery filled me with new alarm. I believed I could detect in the virgin eyes of both the girls the very abandonment of love for Orazio Calvo.

And one night, after I had retired to sleep, he walked into my room and stood at the foot of the bed, leaning over the rail. The glimmer of a lamp showed me his extreme pallor, the fire that swelled and inflamed his stern eyes. I dreaded to break the long silence between us.

"I love them!" he suddenly exclaimed, paroxysmal in passion.

Love them! Every nerve in my body rose shuddering in revolt against him. Love them! Yet the trill of his voice, the trembling bed-rail, left no doubt of the genuineness, the intensity of his meaning.

"But which of them, in God's name?" I asked.

"Which? Miss—Grace—I think."

I think!

The enigma utterly confounded me.

But my vague presentiments were laid to rest when, two months later, the dark-haired Grace was led by him to the altar of the village-church hard by. The young wife was immediately carried off to the Continent. From widely divergent points of the earth's surface—from Delhi—from Memphis—her mother heard from her. Finally she took up her residence in the mountain home of her husband's race. Her constant promise to revisit England she never fulfilled.

During the space of two years I received several illegible letters from Count Calvo (the vehemence of his temperament hardly permitted his writing to be read; for a steel nib immediately broke to splinters under his hand; and his attempt to write many a word with the quill resulted in nothing but a thick dash)—and two from his wife, in both of which latter I fancied though I do not say it was more than fancy—that I could detect a note of deep, and even weird, melancholy.

And once again, at the end of these two years, Count Orazio Calvo stood unexpectedly before me in my house. A glance told me that he was a changed man. Some disease surely—I thought The hungry eyes, no longer cold, shifted incessantly, His fingers clutched continually at some phantom thing in the palm of his hand. My lips formed the word, "Orestes."

"But the countess?" I enquired.

"Is dead."

"Dead!"

"I say it. Dead!"

I shuddered as he uttered the word.

The same hour he proceeded to the farm, I with him. The news of Grace's death had shortly preceded him by letter. He had sent, too, a lock of her hair, several little mementoes. The little home, when we reached it a second time, was a house of Woe.

I SOON returned to London, leaving the Count behind me. Five

months later, I received a letter begging me to go back to the

farm on a matter of some delicacy.

Now, I may as well say at once that I am by no means what would be called a squeamish person; that in general I regard the notions of Clapham with so much, and only so much, attention as the superstitions of ancient Egypt. Yet, for some reason or other, I now felt impelled to protest with the most heart-felt ardour against the projected marriage of Count Calvo with the fair-haired Ethel. An instinct—illogical, perhaps, but deep—told me of something uncanny, awesome, in the union. Earnestly did I implore the dear mother, now heart-broken and bereft, to interpose her will. She, too, felt all I felt; but dared not, she said, coerce the overmastering inclinations of the girl.

I accordingly accompanied Miss Ethel to Paris, and on a dark December day, in the gloomy church of St. Sulpice, saw her united to the object of her ecstatic love.

From her, as from a nature more affectionate and sunny than that of her sister, the letters I received came more regularly. They were dated from the various capitals of Europe, and then for some time from Venice; and in them, too, I found—or thought I found—a tone of heart-sickness, of disappointment. But this feeling, if it existed at all, must have been short-lived; for on taking up her residence at the Villa Calvo, her letters became suddenly voluminous and frequent. Ethel, it was now clear, was happy. In one epistle, I received a long and very comical history of the only visit which ever disturbed her solitude, paid by the podestà and staff-general of Bastia; in another, a gay account of the eccentricities of a haughty old Corsican peasant who did duty as butler. Every trifle seemed to make her joyful; and every sentence began or ended with "her dear lord;" his condescending love for her; her worship of him. Quite suddenly the letters ceased altogether.

IT may have been a year and a half after the second marriage

that I found myself at Marseilles en route for Southern

Italy. That I felt a certain relief when I entered the station to

see my train steaming away is certain; but so secret are

sometimes the workings of the Will, that I was only

half-conscious of the feeling, nor could I explain it. Half an

hour later, however, as I sauntered in la Canabière, I was able

to read myself. From this point the harbour is fully visible, and

looking westward, I caught sight of a little steamer making her

way out from Port la Joliette. I was too salted a

Marseillais not to know her—it was La

Mite, a boat of the old Valéry line not yet grown into the

Compagnie Transatlantique: in eighteen hours she would be lying

at anchor in the harbour of Ajaccio. I hastened to the

quai region; the vessel Was then puffing under the guns of

St. Nicolas. I accosted a group of propped watermen:

"Tell me—is it at all possible to catch her now?"

They looked lazily at her.

"She's off," said one, "le bon diable même ne saurait—"

My desire must have been very great, if it was at all equal to my disappointment.

I continued my way eastward; again and again finding it necessary to prove to myself that it was absurd to go out of one's way to visit forgetful friends. Fréjus, Genoa, Pisa—keeping always to the coast—I reached at last the central point between Pisa and Rome. Here, at Follonica, I stopped short:—over-mastered—and travelling by horse, reached the coast village of Piombino, opposite the singular island, tombstone-shaped, called by the Romans Oethalia, and now Ile d'Elbe; there made terms with the padrone of a small speronare, and in twelve hours landed at Bastia. I was bent upon visiting Count Orazio Calvo in his fortress home.

Mounted on a small Corsican pony, and accompanied by a guide on a mule, I turned southward, and began the ascent. The fever-mists of the low-lying east coast hung heavy, and under this pall, interminable stretches of makis (thick copse) flamed with arbutus leaves, and the purple of maple fruit, and were aromatic with the myrrh of cisti. Here and there on the dizzy edge of a ravine, a solitary hut; or in the depths of the wood, the dole of a shepherd's bagpipe; now the tinkle of goat-bells from afar, now the flap of a raven's wing, or the momentary phantom of a brown wild sheep (mufri). My guttural companion spoke continually on the subject of the brigands. Twice only we passed through mountain villages, and in the afternoon of the second day reached Spello. The short remainder of my upward way I continued in accordance with verbal directions. Before long the Villa Calvo rose sternly before me.

I crossed a dry flat moat, and made fast my animal to a staple in one of the granite pillars of the gateway. Silence pervaded the place. I noticed a decided rankness in the garden on each side of the forecourt. Ascending a flight of marble steps, I rang an iron bell hanging beneath one of the two front porticoes. Its clanging made a sharp break in the stillness. But to my repeated summonses there came no answer. At last I boldly pushed back the unfastened portal, and entered the house.

So long I wandered about, that at last, in a complexity of long velveted corridors and dim chambers, I lost my bearings. The impression wrought on me by the deserted bigness of the mansion was intense. Even my own footfall was inaudible. The evening was now darkening toward night. From where I stood I heard the chirping of a cicada. By an effort I raised my voice and called, but only echoes answered me. In an elliptical apartment, I found a table spread—the white cloth, wines, all the restes of a meal, gold and silver plate, faded grapes; a clock on a pedestal of ebony, it had ceased to tick; in another chamber I came on a lady's garden-hat on a divan. And over all the dreariness of Gethsemane. Trembling hesitancy to proceed further possessed me.

In a remote wing I came at length to a passage, in the wall of which was a nail-studded Gothic door. It occasioned my surprise, for though it now stood ajar, it was provided on the outside with shot-bolts, and from this side a large key still projected. I entered the suite to which it admitted. The rooms were furnished with exceptional splendour, and here a piece of music, there an article of jewellery, seemed to betoken the habitual presence of a lady. Then in the middle of a carpet something chanced to meet my careful outlook which fully confirmed me in this supposition—two very long hairs. At this sight I found it necessary to call up all my courage. With the daring of despair I picked up one of the filaments, and held it to the just dying violet light filtered through the stained glass of the casement. I expected—I must, I think, have expected—to find it of the blonde nuance of the Countess Ethel's hair. A sob of horror burst from me when I saw it lie on my palm dark as the brown of Vandyke.

Yet another long, heart-torturing search, and in a loftier part of the building I faced a draperied door. On attempting to push it back, I discovered it to be locked. Yet this door I determined to open, if I could; and again I bent all my strength to the effort. It remained closed, hiding its mystery. It was only when on the point of moving away that I noticed, just projecting from under the bottom, a white substance. I stooped and drew it out. It was now dark, but I could see that it was a large envelope, and, peering close, detected my name in the writing of the count. With this in my hand I hurried from the spot—through the vast house of desolation—beyond the bounds of the whole gloomy and terror-haunted domain.

"My friend," thus ran, in the somewhat explosive, Aeschylian style so characteristic of him, the all but indecipherable MS. of Count Orazio Calvo—"this document which I address to you will in all probability never reach you. I write it, however, rather by way of monument to my own integrity, than with the hope that it will be read by other eyes.

"My friend, that foul and hellish monster, Pope Clement VII., pronounced in 1525 a curse against the sons of my race. It has been a secret tradition with my uncultured fathers to believe all-unwillingly in its ultimate fulfilment. Perhaps even I myself, in spite of a life of search into the make and meaning of the universe, have been unable wholly to expel some lingering half-credence in this ancient superstition.

"That the malediction has at last overtaken us is now a certainty. With me my race expires. I write this as a protest —and a defiance—against a fate wholly unmerited.

"You cannot doubt that I loved—you could not be so lunatic. And you know, too, that I never withheld my hand from any joy. To desire, with me and the stock of which I come, has always been to possess.

"But soon after realizing my passion, I was confronted by a stupendous problem. In order to solve it I made a leap into the dark, and married—the Countess Grace. I expected happiness. Happiness was far from me. The poor lady, seeing my bitter disappointment, pined. The splendour of her beauty dimmed. After a time I refused to look upon her; to see her face increased my fever. A fire scorched my chest. I traversed the continents, seeking rest; I consulted the greatest physicians; I puzzled them; they pronounced me mad—rabid with the bite of the tarantula. My mysterious malady took only deeper root. I was devoured by the longings of Tantalus—a passion more fervid, and more pure, than the holy rage of the seraphim consumed me.

"When my agonies had reached the intolerable degree, I extorted from my wife, who greatly loved and also feared me, a vow to hold no communication with any of her former friends during the space of ten years. On her knees she implored me to pity her mother, her sister, who would suppose her dead. But in her eyes my bare will had by this time acquired the dignity and force of law, and I moreover soothed her with invented reasons which partially satisfied her intellect. Leaving her among the mountains, with desperate resolve I announced her death, and returned to England. I wedded—the Countess Ethel.

"The gross word 'bigamy' perhaps rises to your mind. My friend, it is immaterial. I, too, at the time, was slightly troubled by some such thought. This second marriage I now know to have been the most sacred, just, and essential that was ever consummated.

"And now at least, my friend, I looked for peace; and again —again—the mawkish after-taste of the new-awakened glutton filled my mouth. I felt, it is true, some sensible alleviation of my disorder. But my Ethel, observing me still cold, unrestful, grew sad. I found her often in tears. We passed together from city to city, till for a time, we settled in my palazzo on the Canal Grande in Venice.

"The great problem, you perceive, was still unsolved. I loved—with a love of which ordinary men can never dream. But whom?—what? Not Grace, that had been proved. Not Ethel, that was being proved. Then whom? The discovery that waited for me was doubtless accelerated by the wild, brief joy that filled me whenever I left Venice to visit Corsica, or Corsica to visit Venice. Faint glimpses of the truth must have lighted me then; but many months passed before, on a starry night, as a gondola floated me slowly over the Canalazzo, I started up with a shout, my soul flooded with the whole supernal secret of the mystery.

"The very next day I returned to Corsica. My friend, attached to the Villa Calvo is a wing wholly cut off from communication with the rest of the house, save by a single door. It was used in former centuries by some of the women of my race—for periods sometimes of several years—as a place of penitential retreat. These erring souls were careful, however, that their hermitage should be wide and luxurious; the high-walled little garden at the end afforded them a place of exercise; a separate kitchen and staff of attendants compensated for a too rigorous devotion to their rosaries, their prie-dieu, and their breviaries; a door bolted on the wrong side guarded them from contact with a world they had too much loved. Into this wing I now introduced the Countess Grace. Her love was thereby tested to the utmost; not, I tell you, without a struggle did my will subdue her high soul. 'Am I then—a free Englishwoman—a prisoner in a Corsican castle?' she asked. 'Aye—a prisoner,' I replied, 'but a prisoner to her prisoner.' Seeing me foam and grovel at her feet, she had pity and yielded. An aged servant of my father, sworn to secrecy, a captive with her, supplied her wants. The other menials, save two, I dismissed. Then I set out for the mainland, and returned to Corsica—with Ethel.

"It was a step bold, but necessary to my sanity. For of the full nature of my passion I was now aware. I did not, as I have said, love the two countesses severally, but and here was the tremendous secret of my destiny—I loved them conjointly. I write, you think, the drivel of a maniac? If you think so, be sure that the reason is your own shallowness, your own folly. Can it be that you have investigated the nature of things to so little purpose as to imagine that you know? Strange births, multiple births; the mystery of chemical combination; of. all welding processes, from the welding of metals, to the adhesion of flesh to bone, to the welding of spirits; what is a unity, what a duality; the mystery of the thing named soul—have you then probed these matters? There is none, my friend, wholly dark but him who dreams that he knows! Tell me only this: which of the halves would you love were your wife bisected by a thunderbolt? Neither much, I think? Yet the two together? So I, too, loved an entity, not either of the parts which composed it. The woman I adored was the woman who would have been born, had the birth of which Grace and Ethel were the product been single and not double. It happened indeed to be double; but do not imagine that that in any way affects the original aggregation either of spirit or of matter. It became clear to me that when the two countesses stood shoulder to shoulder the woman I loved was there. They, in respect of me, completed each other. Upon such secrets does the daily sun shine. One—a mystic one, a dual one, if you will—but not two—was my bride. To my soul, now made clairvoyant by its passion, they formed, though divided in the flesh, a single being.

"And as the copper and the zinc, kept asunder, remain ineffectual, but put into approximation, evolve the most potent motive in the universe—so they. The effect of rapture which nature had rendered them capable of producing upon me depended, it was clear, upon their physical juxtaposition. So it was in the first instance at the farm, where the impression wrought upon me was an impression not effected by either, but by both; and it was this impression which had caused me to love. It was therefore essential to my happiness that they should dwell within the same walls—house beneath the same roof—that I should pass straight from the goddess grandeur of the one to the laughter and the love of the other.

"This I accordingly accomplished. And now began a life— for me, for them—of such exceeding bliss as earth contained not beside. No longer could either doubt the genuineness of my passion. My fever vanished. Each revelled in my new-born tenderness. Ah! they loved. Some of the letters written by the Countess Ethel to you at this time I saw; did they not speak of an existence crowned with joy? Grace, too, forgot her repinings, the gloom of her seclusion, in the wealth of the affection I lavished upon her. A shade of anger might cross me if Ethel would revert to the forbidden subject of the decease of Grace, urging me to describe her death-bed. Otherwise all was halcyon. I spent by the side of my Grace those hours of the day during which Ethel supposed me engaged in study; and though my beauteous captive still gently chid me for concealing the secret reasons which moved me to debar her from the rest of the house, she seemed little by little to grow reconciled to my whim, and in her dark eye shone only the light of love and peace.

"My friend, one day in this azure sky the blackness of hell arose.

"I beheld my Ethel stand by night—in the part, too, of the house most remote from her apartments—before the bolted door, and listen. Observing my eye upon her, she moved stealthily, guiltily away. I stood rooted—struck by a thunderbolt!—to the spot. So then, she knew—she knew—that there was something—something hidden, forbidden—behind those bolts and bars!

"This incident unloosed once more in me the demon of gloom. I grew acutely suspicious. Suppose, I whispered to my heart, suppose.... The thought dimmed my eyes. I turned myself into a lynx's eye to watch.

"My moodiness fell straightway upon them both. Grace grew silent, once again resentful, carping; Ethel dreamy, pensive. She ceased to write to you. The laughter was quenched. Weeks passed. I tracked shadows in the dark; I probed to the bottom the creak of a plank at midnight. That vague suspicions, presentiments filled the mind of Grace, I could no longer doubt. One day, throwing off her fear of my anger, weeping on my shoulder, the gentle Ethel boldly questioned me as to what dreadful secret I hid from her 'in the western wing.' Great God! I silenced her with a reproof.

"But that the catastrophe to happen was inevitable, I should have known. The situation was all too tempting for the forbearance of the Parcae. Here were all the elements of a disaster, needing but the touch of Fate, the match to the mine, to blow our lives into annihilation. And when the tragedy came, it came with an all-destroying suddenness!

"For as I sat and read in the dead of the night, I knew that a gentle tread went swiftly past my door. I arose and, crouching cat-like, followed. I could discern a bent form in the gloom of the unlighted corridor. God! and now the moonlight streamed in from a window, and beamed athwart a female figure draped in loose attire. I was convulsed with earthquake shocks of rage. Ethel, I hissed to the floor on which I crawled—Ethel again—spying by night! She took the way to her own bedchamber, of old occupied by her sister. And now she reached it—drew open the door—the light from within gushed out upon her: I saw—by the powers of blackest hell!—the arrogant throat, the ponderous cataracts of dark-brown hair—Grace! And in that room was Ethel! I rushed forward. For one insensate moment only they stared crazily, crazily into each other's eyes—then from their two throats a shriek so shrill that it must have pierced even to distant Spello—and they flew like maniacs to each other's straining arms.

"It is curious that at this supreme instant, my first unconquerable instinct—the instinct of the Gorsican vendetta blood-hound—was to plunge a sword into the bosom of the ancient servant through whose betrayal this woe had befallen us. I crept away in the darkness, and ran towards the western wing, pausing only to take a loaded blunderbuss from the armoury. The bolted door I found secured as usual, and indeed, I alone kept the key; the countess had escaped then through the gate in the wall of the garden, and of this the old man was the guardian. He had thus been either false or careless. As I passed inward, there was light. I noticed lying on an escritoire a scrap of paper. I took it, and read: 'I have chanced to hear a soft sound of singing at nightfall. Whoever you are, try, if you are sorrowful, to escape—to see me. Help, if my help can save, shall not be wanting.' It was unsigned, and the writer, dreading the chance of my eyes, had carefully disguised her hand—yet I knew. With redoubled fury I ran from room to room to find my faithless servant; he presently sighted me, and darted with the alacrity of youth down the steps into the garden, screaming his innocence. He hid among the trees, till, marking him well, I fired. Loudly bellowing, he fell. I found later that the others too, hearing the screams and turmoil, and fearing my frenzy, had fled the house.

"I returned to the chamber of the fatal meeting. The two ladies, hand in hand, rose and confronted me. In the gentle eye and the bold eye alike I read my doom—resistance active, resistance passive to my will, even to the death. I know their mother—her quiet but adamantine resolution in matters where the religious motif intervenes. And as she, so they. I did not at all doubt that I could sooner turn the sun to ice than move them from their purpose of rebellion.

"'We have no avenger,' said the stately countess Grace, 'but with our own hands we shall protect ourselves from outrage,' and she raised a jewelled dagger as if to strike my breast.

"'Oh, no, no, Grace,' cried Ethel interposing,'not him, my love—strike me!' Then turning to me with tears—' Oh, why, why did you wrong us, who love you, thus?'

"'To your own apartments, madam,' I said to Grace.

"Not yet had my voice lost its intonation of command. Struggling to disobey, with face of ashen hue, she slowly relinquished the hand of her sister—and obeyed.

"And so ended for ever our dream of joy. What further life was now possible for any of us? An hour later, in pity, I waited upon my first-wedded with a goblet of wine. Knowing my meaning, she refused—not angrily, lovingly rather—to drink from my hand; but sweetly yielded up her glorious form when with forceful tenderness I seized it. Alas! the crack, and her sigh, ring like a lunacy in my brain. Ethel, on the other hand, drank without a murmur of the cup I offered, from beneath her lids gazing steadily upon my face with her most blue reproachful eye. She drooped dead upon my breast, smiling, lisping the words: 'Orazio—husband!' No Voceradori of my land shall wail strange alalas over their silence. They lie together on the couch to which I bore them. The first cold grey of the dawning day steals in upon me as I write. The half-emptied goblet is by my side. My friend, their bed is wide! I go—to pass with them—with Her—into the Kingdom of Forgetfulness. Farewell!"

So ended the count's narrative.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.